THE FORBES SYNDICATE AND POSTUM-GENERAL FOODS

It was a great place to work.

—Donald Blair

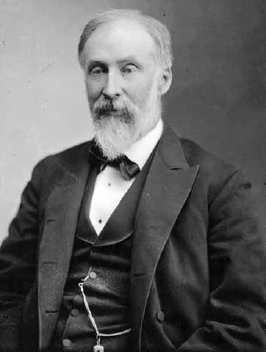

In 1895, Henry Lillie Pierce incorporated the company as Walter Baker & Company, Ltd. and was recorded as having said to his ever faithful secretary, Margaret S. MacGillivary, “The die is cast. Walter Baker & Company is now a corporate body. They say that corporations have no soul, but they outlive men, and I have done what I think is best for the business and for everyone.” However, the death of Henry Lillie Pierce the next year was to prove a great loss, as well as a harbinger of decisive change in the operation of the chocolate mills.

Pierce died at the Beacon Hill home of his friend Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836–1907), poet, novelist and editor of the Atlantic Monthly, where he was spending the evening prior to his departure on a trip to Europe. In forty-two years, Pierce had increased Baker & Company fortyfold and thereby amassed an immense fortune, much of which he left to charity. However, he did not forget that his four hundred employees were a large and very important part of his success. The eighteenth clause of his lengthy will read:

To each person, male or female, who shall be in my employment or service as an operative, laborer, or domestic (including all hands at the mill) at the time of my decease, except those who are herein specifically named as legatees, I give $100.00.

The business was purchased in 1897 by a syndicate composed largely of Boston capitalists, including J. Murray Forbes, and referred to as the Forbes Syndicate. The cost was $475 a share for the ten thousand shares of the concern, for a total of $4,750,000.

Within a short period of time, according to A Calendar of Walter Baker & Company, the new syndicate was “having the largest trade in history of the Walter Baker chocolate business, and will have to make an addition in our machinery during the coming year.”

Henry Lillie Pierce was not just president of Walter Baker & Company from 1854 to 1896, but he also served as mayor of Boston in 1872 and 1877 and as a United States congressman.

In the next two decades, the company instituted benefits that would directly help the workforce, which had increased steadily. In 1904, all employees with one year or more service received a week’s salary as extra compensation. The company also reduced the workweek from fifty-eight hours to fifty-six hours; the ten-hour day was from 7:00 a.m. to 11:45 a.m. and from 1:00 p.m. to 5:45 p.m. In recognition of the Adamson Act, in 1916, the company adopted an eight-hour day as the basis, with time and a half for extra hours up to a maximum of sixteen hours. Employees were also offered a cooperative group life insurance plan.

In this exciting period, Hugh Clifford Gallagher served as president of Walter Baker & Company, Ltd. He had initially been employed by Josiah Webb at Webb Chocolate Company and came with the acquisition of that chocolate competitor when Henry Pierce purchased the business in 1881. He was respected by Pierce and often traveled with him to expositions, as well as, in 1894, to Europe to purchase chocolate-making machines that were more efficient and more easily operated. During the period from 1895 to 1927, there was a dramatic increase in the importing of cacao beans, with 24 million pounds of cacao beans in 1893 and an incredible 275 million pounds by 1921. This increased demand for chocolate was partly due to the widespread enjoyment of cocoa and chocolate snack bars in the United States, as well as the fifty-five different types of chocolate produced. Baker’s Chocolate saw dramatic increases in production and profit.

It was the consistent quality of its product that ensured Baker & Company’s sustained success. Guarantee sheets stating the high quality and purity of the chocolate and cocoa reassured the public of the company’s commitment to quality. Gallagher continued to expand the business and to order new machinery, especially from Bothfeld & Weygant of New York. He traveled to expositions, as had Pierce, and his visit to the Paris Exposition in 1900 confirmed the well-respected and favorable light in which the general public held Baker’s Chocolate. He recorded in his diary during his stay in Paris that the “display of chocolate confectionery, in comparison with the Exposition of ’89, would lead me to think that there has been a great growth in that branch of the business during the past ten years.”

Gallagher continued Pierce’s vision and expanded the mill complex, building the Ware Mill in 1902 and the Preston Mill in 1903. Both mills were designed by the Boston architectural firm of Winslow & Bigelow, successor firm of Nathaniel Bradlee, who had begun the rebuilding in 1872 when he designed the Pierce Mill. The mills were named for two former chocolate competitors, the Ware Chocolate Company and the Preston Chocolate Company, and with the building of the Power House in 1906 and a refrigeration plant in 1907, the physical plant had been doubled in size. The Power House was a decisive improvement with a high impact on production, as it contained three boilers, two large generators, electric lights and motors in the mills, and most importantly, it allowed for an expansion of the time in which chocolate could be produced. Previously, horse-drawn sprinkler tanks had watered lawns and walkways surrounding the mills during the heat of the day in an effort to cool the surrounding air of the mills.

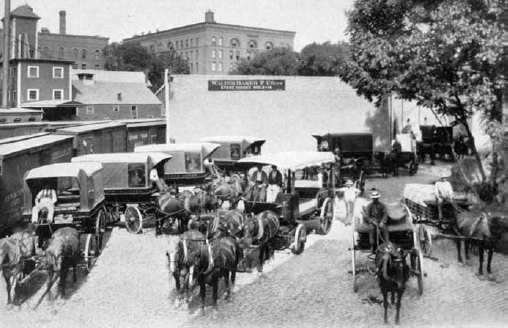

In the early twentieth century, the once important use of horses in the business began to decline. Horses had been stabled on the mill complex for decades, as they provided the horsepower necessary to move chocolate and cocoa. There were ten single-horse teams to carry supplies from storehouses to various mills; two four-horse teams that went to Boston daily with cocoa and chocolate for stores, ships and trains; and a four-horse show team that was impressive, as well as a well-used marketing tool. By 1913, several electric-powered trucks had been purchased, and the horses were gently phased out of the business.

John Gordon was employed to oversee the horses and stables from 1903 to 1924, and during this time the original twenty-nine horses were reduced to ten in 1920, as electric- and gasoline-powered trucks were doing the work. In 1909, the first electric-powered truck was purchased, two more trucks arrived in 1911 and another was bought in 1912. In 1913, another electric truck was purchased and was to be operated by James Fitzsimmons for the conveying of chocolate to and from the different mills. In 1914, a Walker Electric truck was purchased, and the company continued to implement more efficient timesaving services.

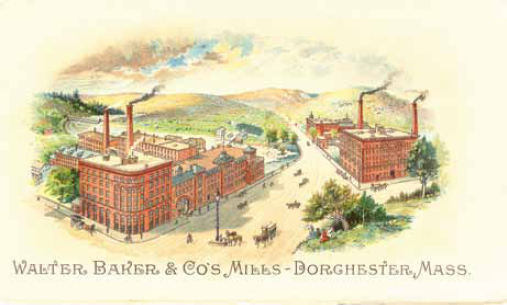

1. A bird’s-eye view of the mills of Walter Baker & Company in 1900 showed, from the left, the Adams Mill, the Pierce Mill, the Preston Mill, the Webb Mill and the Baker Mill.

2. A Baker’s breakfast cocoa tin tray was produced in 1907 to commemorate the Jamestown, Virginia Exposition, complete with the Edwin J. Lewis Jr.–designed New England Homestead in the lower center.

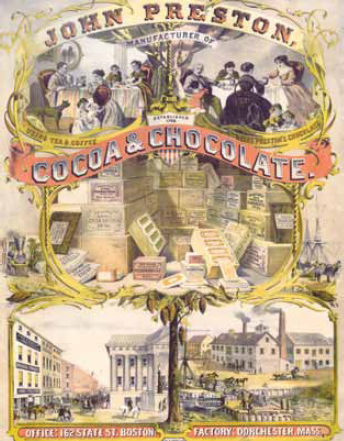

3. Preston Chocolate Company was founded in 1768 by John Preston, brother-in-law of Dr. James Baker. This advertisement has vignettes with the Boston office and Dorchester mill, families at table, boxes and bags of cacao beans and shells and transportation, all in an elaborate scroll design. Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum.

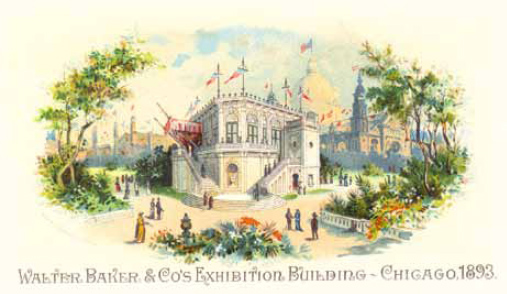

4. The Chicago Exposition of 1893 was a major marketing coup for Walter Baker & Company. The New York firm of Carrere and Hastings designed the two-story white marble exhibition building, replete with twin staircases, balconies and a large hall where demonstrators greeted visitors.

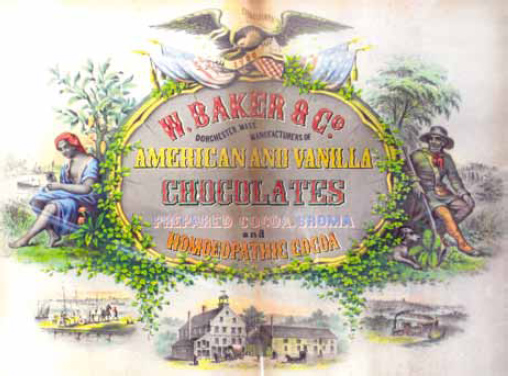

5. Various products of Walter Baker & Company were advertised in this elaborate broadside, including American and vanilla chocolates, prepared cocoa and broma, as well as homoeopathic cocoa. An eagle and American flags surmount a cartouche flanked by an Arabian and American frontiersman, with the mills, wharf and train distribution points below.

6. Artist Norman Price depicted Little Red Riding Hood approaching Grandmother’s House in this 1916 advertisement, with “a basket of Christmas dainties with Baker’s Cocoa and Chocolate” on her arm and a large spray of holly to surprise her grandmother, hopefully before the wolf arrives!

7. A circa 1855 lavishly illustrated broadside of Walter Baker & Company advertised its various products, including chocolate, cocoa, broma and cocoa paste, in addition to homeopathic and dietetic cocoa. The tropical scene with cacao plants and pods is enhanced by a woman holding a cacao pod on the lower right. Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum.

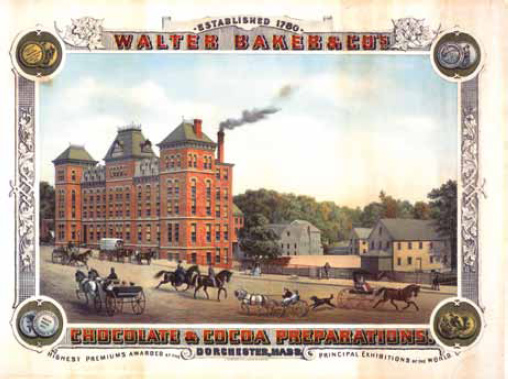

8. A circa 1873 advertisement of the Pierce Mill showed Walter Baker & Company’s medals in the four corner vignettes, the “highest premiums awarded a the principal exhibitions of the world.” Courtesy of Boston Athenaeum.

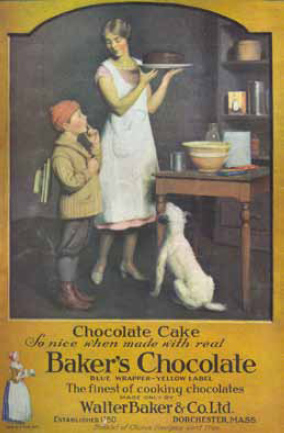

9. Chocolate cake, held aloft by Mother as her son returns home from school and the family dog stares in delight, was said to be “so nice when made with real Baker’s Chocolate.” Confidently called the “finest of cooking chocolates,” Baker’s was identifiable by its blue wrapper and yellow label.

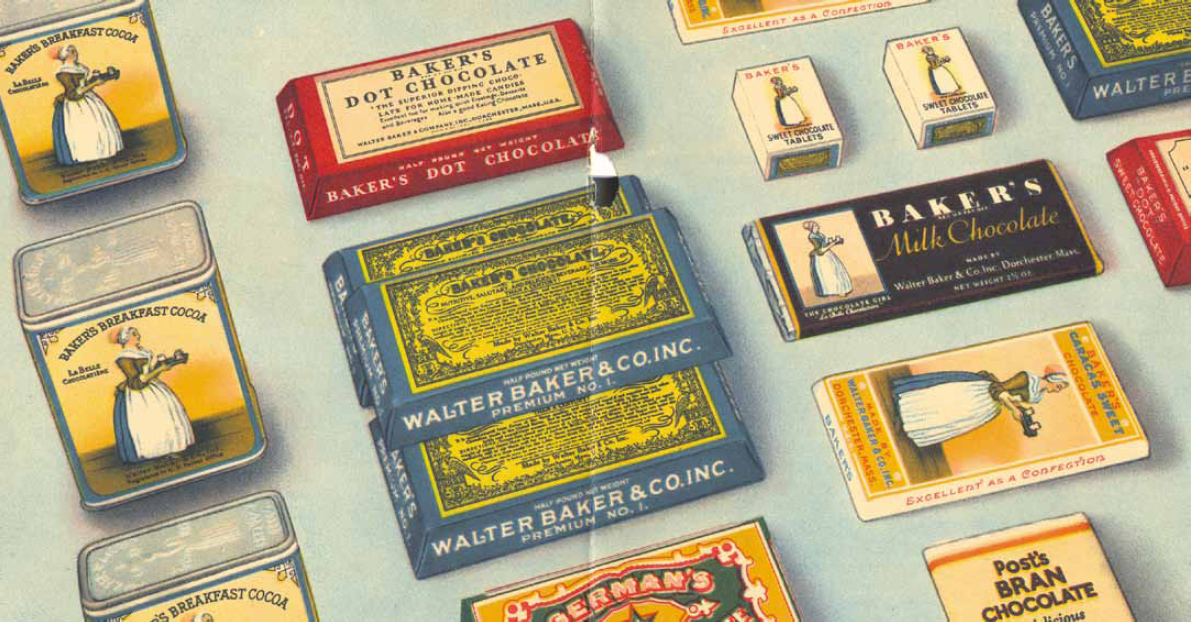

10. By the mid-1940s, Walter Baker & Company had expanded its manufacture of breakfast cocoa, Premium No. 1 chocolate, Dot sweet chocolate and German’s sweet chocolate to include Post’s Bran chocolate, Baker’s milk chocolate bars and Baker’s sweet chocolate tablets, which were circular disks of sweet chocolate covered in a candy.

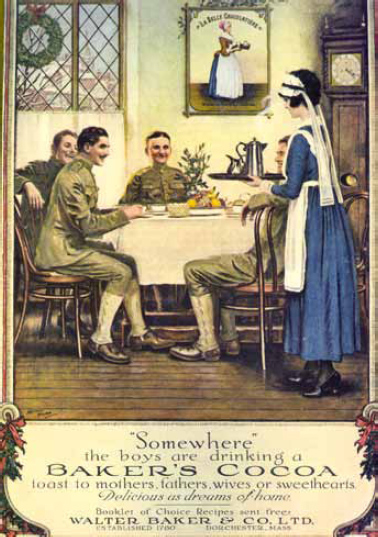

11. During World War I, it was said in this advertisement that “somewhere the boys are drinking a Baker’s cocoa toast to mothers, fathers, wives or sweethearts,” with the poignant statement that the chocolate is as “delicious as dreams of home.”

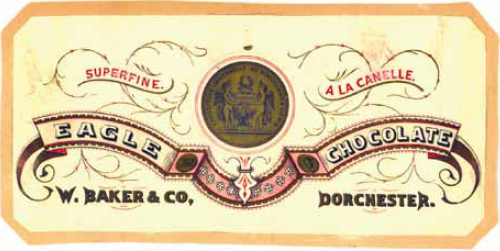

12. Eagle Chocolate was a superfine product “à la canelle” made by Walter Baker & Company in the Eagle Mill in Dorchester. Courtesy of Earl Taylor.

Horse-drawn wagons were loaded with boxes of wrapped chocolates and cocoa tins at the storehouses before delivering the products to shipping points in Boston. The wagons were covered with tarps to protect the easily damaged chocolate from the warmth of the sun.

WORLD WAR I

The United States declared war against Germany and entered World War I on April 16, 1917. Employees enlisted to serve in the war and were promptly replaced by a higher percentage of female employees and retirees. The operation saw the production of a chocolate bar that was stamped with the initials “WTW,” or “Win the War,” which was provided as part of the soldiers’ kits. Chocolate maker Joseph D. Beal remembered:

After the boys left to join the army forces at the front in France, we could not get much sugar to use. What chocolate we did make was eating chocolate for the soldiers, and only one kind of coating chocolate, in ten pound cakes.

In an attractive advertisement during this period, doughboys, or World War I Allied soldiers, are seated at a table in a French inn, being served cocoa by a woman who looks remarkably like La Belle Chocolatiere. It was an important part of the production during the war, but the chocolate marked “WTW” brought great renown and widespread awareness to the company as hundreds of thousands of veterans returned to the United States and sought the same chocolate they had enjoyed during the war.

The Walter Baker Administration Building, designed by George F. Shepard Jr. and built in 1919, commanded the streetscape in 1970. Flanked on the left by the Forbes Mill and on the right by the Pierce Mill, the bridge spanning the Neponset River had become a major connector from Boston to the South Shore communities. Courtesy of Ann and George Thompson.

The expansion in 1919 of the mill complex with the building of the Administration Building had a major impact on the streetscape, with the Classical Revival design by George F. Shepard Jr. differing from the earlier mills. The continued expansion for the first two decades of the twentieth century led to the need for a larger workforce, which in turn meant increased benefits to retain employees and, in 1924, a hospital for medical treatment with a full-time trained nurse on duty at all times of operation and a doctor who had regular office hours. This period of growth was a decisive one and was, in many ways, perceived by managers and employees as a combined effort of all.

In 1926, William B. Thurber became president of Walter Baker & Company, Ltd., following on the great strides and expansion of the business made by Hugh Clifford Gallagher. A year after his election, ownership of the chocolate company was transferred to Postum Company, Inc. On August 12, 1927, Walter Baker & Company, Ltd., officially became known as the Baker Division of General Foods, and the following employee benefits were continued, and in most cases expanded, under its administration:

Cooperative retirement plan

Vacation with pay for all regular employees

Sickness benefit plan

Termination allowance plan

Group life insurance plan

Federal Labor Union No. 21243 of Dorchester Lower Mills, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, was also established.

Following the acquisition of the chocolate company by General Foods, the line of confectionary chocolate was greatly expanded. The first milk chocolate was produced in 1928. Competitors in the United States, such as Hershey’s and Mars, had been making confectionary chocolate for years, and General Foods was well aware that it needed to compete for a foothold in this market. In the next decade, the expansion of this confectionary line was to see “readily edible” chocolate that could compete with other manufacturers of chocolate candy not just in the United States but also in Europe. Baker’s new confectionary line included semisweet chocolate bars, almond bars, milk chocolate bars, mint wafers, rum and butter wafers and milk chocolate bars in mocha, coconut and cashew varieties. This new confection line was so well received that a Cincinnati newspaper stated in April 1930, “General Foods Wins Record Sales with $1,000,000 More Advertising.” It went on to say that the

Walter Baker bars are enabling General Foods to enter the confectionary field and drug store outlets for the first time. Retailing at five and ten cents, they have been tested for several months in New England and New York State.

With the aid of the 1929 Hawley-Smoot tariff laws, which aimed at eliminating foreign competition in order to stabilize the competitors, General Foods expanded not only the Baker Chocolate Division but also its many other food-related companies. In 1941, General Foods had twenty-eight companies in its food production empire, which was to dramatically increase to over fifty companies by 1950. General Foods had ensured its place as a major food production and distribution company in the United States, and the Baker Chocolate Division had proven itself to be not just a delicious venue but also a valuable and major asset to General Foods. The company continued its long-standing practice of strict quality control, instituted under both Pierce and Gallagher, which ensured the consistent production of quality-made chocolate and cocoa. According to A Calendar of Walter Baker & Company, a scientific laboratory was maintained and staffed for “the sole purpose of marking each batch of Baker products to prepare for quick identification in the event of an injury” or any questions on production. By the early 1940s, the company had expanded its offerings to the public by adding “recipe-friendly” items that were delicious and also saved valuable time and expense for a more cost-conscious public. Among these new time-saving offerings was an instant cocoa mix that could be used to make either hot or cold cocoa in an instant, as well as chocolate fudge, cake frosting and chocolate sauce. This offering was taken up with alacrity by housewives across the country and was a great success from the start.

Demonstrators stand beneath a larger-than-life portrait of Anna Baltauf at the top of the stairs in the Administration Building. Each woman holds a tray of cocoa cups or plates of chocolate delicacies made from one of the Choice Recipe cookbooks distributed by the company annually.

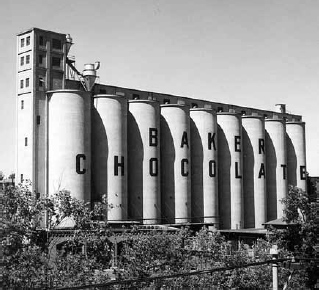

In 1941, General Foods decided to build eighteen storage silos and a grain elevator adjacent to the Park Mill Building, as it was said in the 1941 General Foods Annual Report that “our previous storage facilities were needed by the Government.” There were nine pairs of monumental concrete silos attached to a long concrete core that was used to store dried cacao beans. According to Donald Blair, an employee of General Foods at the Baker Chocolate Division for many years, the cacao beans

came in burlap bags from all over the world and were dumped into a conveyor belt and then someone had to direct which individual silo it went into by bean type. The floor was flat and covered the entire area, but each silo had a hatch on top so you could get into it; this was necessary from time to time as the beans would get stuck together and hang up. When that happened, and when they tried everything else to dislodge them, they would lower a guy down through the hatch in a bosun chair, and he would chop away at the stuck beans until they came loose. They gave everybody that worked in the production/shop area uniforms, and they also laundered them so you always had clean ones, as some jobs were quite messy and dirty.

The silos were eighteen circular connected units that could store a variety of dried cacao beans until needed in the production of chocolate. The silos were on the Dorchester side, between the Neponset River and River Street. The surface trolley on the right connected Ashmont Station and Mattapan and is listed in Ripley’s Believe It or Not as the only trolley in the world to run through a cemetery, Cedar Grove Cemetery in Dorchester. Courtesy of Andy Sawicky.

The silos boldly advertised Baker Chocolate to all who passed by. Built in 1941, the silos were never filled to capacity, and after 1965, they stood forlorn and unused until their demolition in 1979.

The silos were built to hold tons of cacao beans. It was thought that World War II would impede the availability of cacao beans, and it was said that “there must be no shortage of chocolate, which is the chief essential of emergency rations for an army in the field.” The silos, however, were never filled to capacity; still, they were an important and highly visible landmark of the complex, as they could be seen from all areas. In addition, they were adjacent to the railroad tracks and the surface trolley that connected Ashmont Station on the MBTA Red Line with Mattapan Station. The silos were abandoned by the early 1960s and demolished in 1987.

In the post–World War II era, the successful marketing by General Foods ensured that “Baker Chocolate” was a “trusted household name.” Baker’s was the oldest manufacturer of chocolate in the United States and was among the most respected and well-known producers in the food industry. General Foods was well aware that the Baker Division products had been used in American kitchens for generations, but it was only one of fourteen divisions with plants located in over fifty locations. During the 1950s, the Walter Baker Company, under the Jell-O Division, continued to produce cocoa, chocolate, an instant chocolate drink, Dream Whip and chocolate chips, as well as bulk chocolate and cocoas that were sold to the baking, ice cream and candy industries. Though profitable and well received locally, General Foods made the concerted decision in 1960 to consolidate the four plants operating under the Jell-O Division at a centralized facility, rather than continue at the scattered locations as they had for decades. These four divisions—the Walter Baker plant in Dorchester and Milton, Massachusetts; the Jell-O plant in New York; the Baker cocoanut plant in Hoboken, New Jersey; and the Minute Tapioca plant in Orange, Massachusetts—were by 1965 perceived by General Foods as “simply not efficient by current-day standards.” Their consolidation in a central facility would allow for a single administrative organization, which, it was hoped, would prove to be as efficient as it was cost effective. The new consolidated plant was built in Dover, Delaware, and was opened in 1965.

Employees have always been an important part of the operation, since Nathaniel Blake was apprenticed to John Hannon. As Donald Blair said in 2006, “It was a great place to work, and they had some wonderful people working there, and I learned a lot from [older employees] as time went by.”

WORLD WAR II

The Baker Chocolate Company saw many employees enlisting during World War II, and the company began to again produce chocolate rations for the soldiers and sailors serving in the war. The high caffeine content of the chocolate not only gave quick energy, but it was also a delicious and very welcome treat. In addition, the company, as a division of General Foods, contributed chocolate and cocoa to the war effort for food parcels distributed by the Red Cross to Allied war prisoners.

A trio of demonstrators offer bars of milk chocolate (some with almonds) at a “Sweet Shoppe” that was set up at the Second Church in Dorchester, the church where Walter Baker worshiped and to which he donated the tower clock.