Rodrigo de Souza Gonçalves, Otávio Ribeiro de Medeiros, Elionor Farah Jreige Weffort and Jorge Katsumi Niyama

CONSTRUCTION OF A SOCIAL DISCLOSURE INDEX

There are a number of studies attempting to grasp the effects of social disclosure, either with respect to the requirement that it should be compulsory or voluntary (Saudagaran & Biddle, 1995; Utting, 2002), as an strategic instrument to the organizations (Machado Filho & Zylbersztajn, 2003; Porter & Kraemer, 2002; Saiia et al., 2003), with respect to factors determining the disclosure (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Campbell, Moore, & Shrives, 2006; Clarkson, Li, Richardson, & Vasvari, 2008), or yet with respect to the repercussion of the disclosure according to its environmental, societary and organizational dimensions (Dhaliwal, Li, Tsang, & Yang, 2009; Orlitzky & Benjamin, 2001; Poddi & Vergalli, 2009) upon the corporation’s image or economic value.

One of the pioneering studies analysing the benefits of social disclosure was that of Anderson and Frankle (1980, p. 475), where the authors conclude that voluntary disclosure can produce a highly favorable return. Later on, other studies have concluded toward the need of regulations concerning that information (Bushee & Leuz, 2005; Saudagaran & Biddle, 1995), while others (Rodriguez & LeMaster, 2007; Utting, 2002) have argued that the disclosure should be maintained as it is, because it is the consequence of a voluntary action.

On the other hand, studies such as de Richardson, Welker, and Hutchinson (1999), Orlitzky and Benjamin (2001), and Brown, Helland, and Smith (2006) have shown that social disclosure must contribute to the organization’s image and corporate reputation and, consequently, to the organization’s profitability. Other empirical studies have been put forward aiming to assess whether this kind of information contributes to reduce the company’s cost of raising capital or to increase the return of the company’s stock (Dhaliwal et al., 2009; Orlitzky & Benjamin, 2001; Poddi & Vergalli, 2009; Richardson & Welker, 2001). In both approaches, the central idea is to identify how social actions, either internal or external, have been perceived by the stock market or by the general public.

When it comes to the environmental sphere, there are studies aiming to understand whether the disclosed information concerning the actions put forward to reduce the impact of the company’s operating activity on society are regarded in a positive way by its stakeholders (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, & Hughes, 2004; Deegan & Gordon, 1996).

With regard to external social programs, studies such as Epstein and Freedman (1994), Gray, Kouhy, and Lavers (1995), Hillman and Keim (2001), Smith, van der, Adhikari, and Tondkar (2005) among others, combine the use of research instruments that include from the application of questionnaires to the analysis of content of social reports, although not presenting methods validating their research techniques.

Therefore, taking into consideration the above-mentioned studies and especially the voluntary nature of the referred information, in order to perform the assessment of that information, the utilization of an instrument which permit the analysis and classification by categories becomes necessary, which can be achieved by means of an index, which is here denominated social disclosure index.

An index is composed of figures synthesizing and translating concepts capable of being measured, either individually or as a group. If an index is to represent the level of disclosure or transparency regarding a certain issue, it must be constructed so as to reflect different levels of information quality, as for instance via the use of an ordinal scale and not by means of a dichotomised scale (Coy & Dixon, 2004). The ordinal scale makes it possible to classify elements within a population, to establish an orderly relationship between certain characteristics and to indicate whether an element possesses more or less of a characteristic than another (Pereira, 2006, p. 221). The use of an ordinal scale in representing the level of disclosure is especially useful since it attempts to categorize the quality of the information being evaluated. In this study, an ordinal scale was utilized, which according to Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham (2005) is characterized by a scale of up to four points.

According to Coy and Dixon (2004, p. 85) some aspects must be taken into consideration when constructing an index, such as: (1) establishing the purposes of the index, (2) identifying which items are required for an appropriate disclosure and their qualitative characteristics, (3) analysis by referees, (4) validating the index’s components, and (5) testing and validating the final index. In this index construction model, after establishing the index’s aims and the items comprising it, these must be submitted for assessment by referees (specialists) as a means of verifying its legibility, which will permit the correct interpretation of the items so that later the index can be subjected to validation and testing.

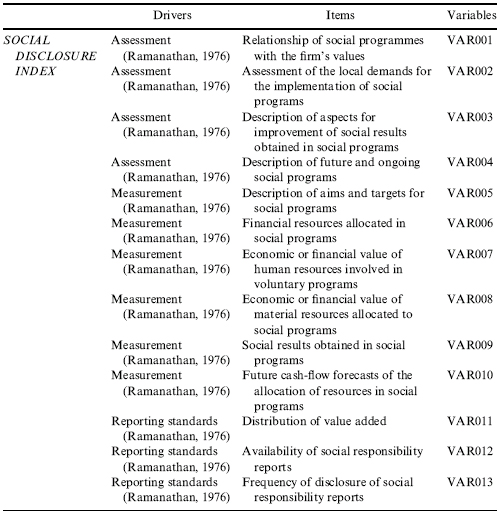

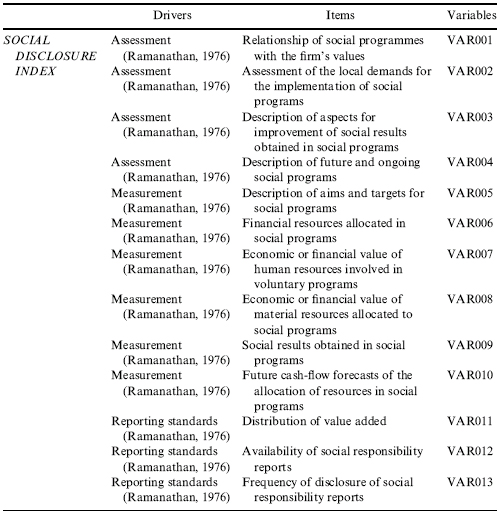

Items Assessed by the Social Disclosure Index

The information to be assessed by the social disclosure index stems from the discretionary actions of social responsibility carried out by companies by means of social programs. The focus on this type of information is especially important as it allows the identification of the corporate objectives by establishing parameters and rendering accounts associated to the allocation of resources in social programs (Riahi-Belkaoui, 2004). With this purpose in mind, we established items related to the disclosure and the rendering of accounts of these actions, based on Ramanathan (1976), Haydel (1989), and Hammond and Miles (2004).

According to Hammond and Miles (2004), one of the first items which must be understood when planning the allocation of resources in social programs is the company’s position with respect to these activities. Haydel (1989, p. 16) believes that as companies tend to relate their social responsibility projects to their corporate strategic planning aims, the importance of these projects becomes clear for the organization, and social responsibility will not be considered as an isolated interest. Accordingly, the item relationship of social programs with firm values was created. Disclosing the reasons why a firm sponsors certain programs is useful since it permits identification of the values that an organization preserves and is concerned with. In addition, the social programs sponsored are a reflection of a firm’s beliefs and values, besides justifying its actions and promoting its image. This kind of approach aids the external user in gaining a better understanding of what a firm is doing and what it is capable of doing to benefit the community.

Another aspect contributing to the understanding of a firm’s procedures and aims associated with social programs is the way in which they were assessed. Insofar as a firm uses such programs to reduce externalities affecting the community, such an assessment should take into account the environment where a firm operates and the impacts it causes on the community (Haydel, 1989; Heal, 2004). Taking this aspect into consideration, the item assessment of the local demands for implementation of social programs was introduced. Before preparing the proposal related to sponsoring social programs, the assessment of what can be done from the viewpoint of the community’s demands is a form of maximizing the resources deployed, as well as clarifying the reasons for focusing on a specific program (Haydel, 1989; Rizx, Dixon, & Woodhead, 2008). Based on the assessment of local demands, it becomes necessary to establish actions aimed at fulfilling such demands, which in turn will determine the aims and targets for organized work in the community. Related to this issue, Haydel (1989, p. 7) maintains that the aims are states or outcomes of a desired behavior, while targets are those types of objectives desired within a certain period of time, covered by a plan. From the social viewpoint, the aims established by a program endeavor to integrate the needs of the people attended by the programs with those of a firm, as they permit a firm to reduce its externalities.

Ramanathan (1976) emphasizes that one of the aims of corporate social responsibility is identifying and measuring the externalities produced by firms on different segments of society, in addition to helping to determine strategies for their actions. According to Haydel (1989), from the economics viewpoint the aims also contribute to the optimization and efficiency of resource allocation, when established in a clear manner. Bearing this in mind, the item description of aims and targets for social programs was created. According to Haydel (1989, p. 7), aims and targets are interchangeable and both represent concepts related to the future. Accordingly, as for any other investment, it becomes necessary to establish aims and targets to be achieved so as to fulfill the demands for which the program was created. This permits reflection on the effectiveness of the actions, and makes it possible for the external user to confront what has been planned with what has been implemented, as well as the identification of the eventual loss of resources by comparing the investment which has been assigned with the social outcomes accomplished (Hammond & Miles, 2004; Haydel, 1989).

After describing the aims, it is next necessary to establish the amount of financial resources required for implementation of the referred programs. This is one of the most delicate issues when dealing with the implementation of social responsibility programs (Hillman & Keim, 2001). For this purpose, three items are proposed: financial resources assigned to social programs; economic and/or financial value of human resources involved in voluntary social programs; and economic and/or financial value of material resources assigned to social programs.

The financial resources assigned to social programs has the function of identifying the amount of financial resources assigned to social responsibility programs (Naser & Nuseibech, 2003). The economic and/or financial value of human resources involved in voluntary social programs is important because the participation of a firm’s employees in social programs is materialised by means of voluntary programs, which represent the costs to an organization. Therefore, a separate identification and measurement of these costs becomes necessary so that they will not be mixed with costs and expenses associated with the operating activities (Gray et al., 1995; Smith et al., 2005). The economic and/or financial value of material resources assigned to social programs is a relevant item because the participation of a firm often occurs not only by means of the assignment of financial resources, but also via the donation of material resources, either in a definitive way (e.g., donation of a building) or in a temporary way (e.g., temporary cession of a building). Its proper identification and measurement avoids the information being biased toward being classified together with other accounts associated with operating activities (Naser & Nuseibech, 2003).

According to Haydel (1989, p. 10), one of the most fragile points with respect to the proposition and implementation of social programs relates to the allocation of resources and to the inadequate monitoring of the commitments and policies, programs, and recurrent instructions. To the author, determining and assessing the impact of social programs in the community, by confronting the aims established and the results obtained, contributes to assure both the social benefits coming from the actions performed and the economic benefits. The disclosure of social results obtained in social programs allows the external user to identify the success or failure of the corporate actions in the social area, in addition to allowing the assessment of the relationship between the value assigned and the results obtained. This item has the purpose of identifying the social results obtained and assessing whether the targets and goals established were attained, which provides the opportunity for improvements to be made in the process (Hammond & Miles, 2004).

As a consequence of the inadequate monitoring and assessment of social programs, Haydel (1989) points out that the analysis regarding future actions is often limited to a mere redistribution of resources. To overcome this problem, Haydel (1989) suggests that three items become necessary when the manager of the resources renders the accounts to an external user as a means of justifying the continuity of the corporate actions in the referred programs and these are: description of aspects for improvement of the results of social outcomes obtained in social programs; description of future and ongoing social programs; and cash-flow forecasts of the future assignment in social programs.

The description of aspects for improving the social outcomes obtained in social programs (Hammond & Miles, 2004; Haydel, 1989) reveals the management’s commitment with respect to the social programs, and also provides an opportunity for the revision of the aims, targets, or even scope of the program. At this stage, Hammond and Miles (2004) suggest a revision of the internal processes and an analysis of whether these are aligned with the purposes they were devised for. The description of future and ongoing social programs (Haydel, 1989; Naser & Nuseibech, 2003) has the purpose of assessing a firm’s capacity both to establish new programs considering emerging social demands based on the points identified as needing improvement, as well as giving continuity to ongoing projects, thereby demonstrating a firm’s commitment to ongoing projects and its attention to the new demands of the community.

Naturally, economic fluctuations will have an impact on decisions regarding resource allocation in new and ongoing social programs. Reducing this uncertainty is one of the roles performed by information by disclosing what a firm expects in the subsequent period under the viewpoint of risk and opportunities. Taking this aspect into account, the item future cash-flow forecasts of the assignment of resources in social programs was introduced. Considering the risks and opportunities for the subsequent period, an assessment of the management’s decisions with respect to future cash flow becomes necessary, either with respect to increasing or reducing the resources available for social programs (Naser & Nuseibech, 2003).

Social information is primarily characterized by voluntary motivations, and in principle is not subjected to questioning by third parties (auditing). In this respect, Epstein and Freedman (1994) believe that such information should be auditable so that they could be taken as reliable. Hammond and Miles (2004) also signal that besides being verifiable by third parties, it should also be made widely available, as well as possessing a predetermined disclosing frequency. Such characteristics are treated in this study as reporting standards (Ramanathan, 1976). Therefore, the dimension – reporting standards – is centered in the need of evaluating the kind of social information which has been audited by third parties, the way by which this information has been made available, as well as the frequency in which the information is made available. With regard to the latter, it is worthwhile to stress that one should not be concerned only with identifying whether the information is made available annually or not, but rather with identifying the moment/date where it can be assessed, under the idea that timeliness only occurs if there is a reduction of uncertainty when the information becomes available.

Under the viewpoint of social information which may be audited by third parties, there is the distribution of value added, which besides having a disclosure standard, makes it possible to the external user to understand how the wealth created by a firm is distributed. The distribution of value added is usually demonstrated by means of the value added report. This report is especially useful to inform the distribution of wealth created by a firm (personnel, taxation, stockholders, stakeholders, etc.), for possessing a specific disclosure standard and also for being liable to verification by independent auditors (Hammond & Miles, 2004; Haydel, 1989).

Accordingly, the items availability of social responsibility reports and frequency of disclosure of social responsibility reports were established. The availability of social responsibility reports (Hammond & Miles, 2004) relates to the extent to which there is widespread access to a firm’s social responsibility information, which usually occurs by means of the internet. The frequency of disclosure of social responsibility reports (Hammond & Miles, 2004) is associated to the disclosure policy, that is, to whether a firm explicitly discloses the frequency in which the reports are disclosed. Usually, social responsibility reports are disclosed annually. Hence, one should expect that firms, besides preparing reports covering one-year periods, will reveal the dates on which they became or will become available.

The items comprising the social disclosure index can be summarized as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Items Comprising the Social Disclosure Index.

Categorization and Scale of the Social Disclosure Index

For assessing the quality of information related to social disclosure, we utilize a content analysis, which according to Malhotra (2003, p. 201) is an appropriate method when the phenomenon to be studied is communication, which is usually carried out by means of reports. For the assessment of social disclosure, annual social responsibility, and sustainability reports were utilized. Unerman (2000) points out that this kind of research should base its analysis on such reports for two reasons: (1) because of their importance and representativeness as an instrument of communication between a firm and its stakeholders and (2) for believing to be virtually impossible to identify and analyse all the communications made by a firm during one period (year).

With respect to the operationalisation of the content analysis, categories were established, which according to Bardin (1977, p. 117), are items or classes connecting a group of elements under a generic title according to their common characteristics. This categorization performs an important role in this research, since it establishes the criteria for the assessment of social disclosure by means of categories, and also permits its classification based on the quality of the information disclosed. The categories aim at identifying the characteristics of the information assessed, from which phrases or sentences are extracted both from a quantitative and qualitative information viewpoint. Therefore, the theoretical categories perform the role of expressing this quality. They are divided into restricted (lowest information level), low, medium, and wide (highest information level), and can be characterized as follows:

(a) Restricted: classification in this category means that a firm simply does not disclose the information associated with the item in question.

(b) Low: classification in this category means that a firm discloses the information related to the item in question, but it does not do so with a breakdown by social program or area of activity, that is, the information is disclosed in an aggregate manner with the use of expressions like “the social programs,” “the social actions,” etc.

(c) Medium: classification in this category means that a firm discloses the information related to the item in question by area of activity or by some of the social programs.

(d) Wide: classification in this category means that a firm discloses the information assessed by the item in question in an analytical manner, that is, there is information for each social program. The characteristic of this information has more precision and amplitude, such as “project x, project y, ….”

Since the theoretical categories are intended to express the quality of information provided by firms under analysis, we used a Likert type scale with four points in order to quantify each theoretical category. The Likert scale in this study is particularly useful because it permits evaluate both the quality and the quantity of the information disclosed, that is, the level of disclosure.

The utilization of a Likert type scale permits the summing up of its individual scores to obtain a total score (index) which must then be submitted to reliability and validations tests (Malhotra, 2003). Considering that the categorization has four ranges for the determination of the quality of information, the social disclosure index is obtained by summing up the thirteen items, each one classified from restricted (1) to wide (4). Therefore, firms analysed with the index proposed here can achieve a minimum of 13 points for firms with all items classified as restricted and a maximum of 52 points for firms with all items classified as wide.

RELIABILITY AND VALIDATION TESTS OF THE SOCIAL DISCLOSURE INDEX

Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Social Disclosure Index

In this phase, an exploratory factor analysis is carried out with the purpose of identifying the relationships among variables, their internal consistency, as well as the identification of common factors among them in order to group the items with the same characteristics. One of the first aspects to be considered when performing an exploratory factor analysis is to verify the number of observations for each indicator. It has been suggested that there should be at least five observations for each variable. Since there were 81 observations for the period 2005–2007 and 83 observations for the period 2008–2009, we can conclude that this recommendation has been accomplished.

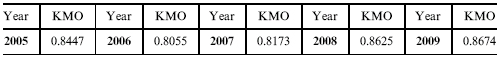

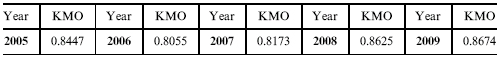

The following phase is the implementation of Bartlett’s sphericity test, which identifies significant cross-correlations among the variables, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, which measures the explanatory power of the data (Table 2).

Table 2. KMO Tests for the Period 2005–2009.

The results obtained for the Bartlett sphericity test indicate that the cross-correlations among the variables are significant for all years in the sample period. The explanatory power of the data for implementation of the factor analysis is also adequate, since the KMO statistic is above 0.80 for all years in the sample period. The KMO test for the whole sample period (2005–2009) obtains a KMO statistic of 0.897, while the test statistic of the Bartlett sphericity test is significant at the 5% level.

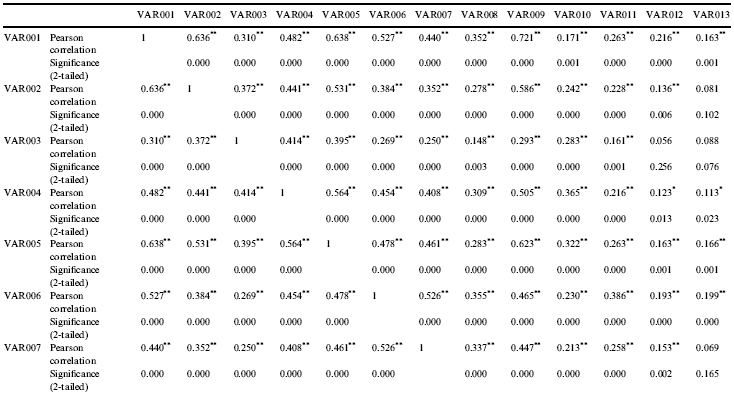

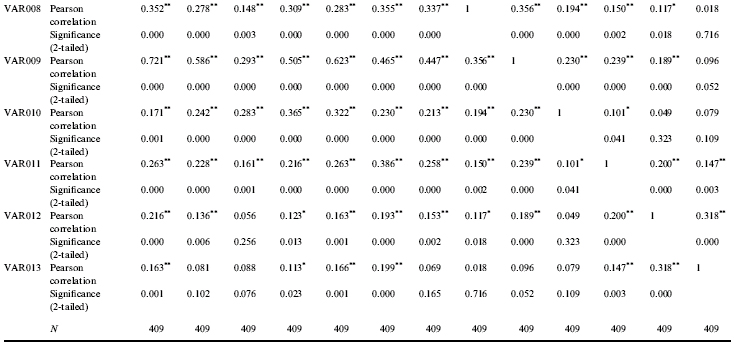

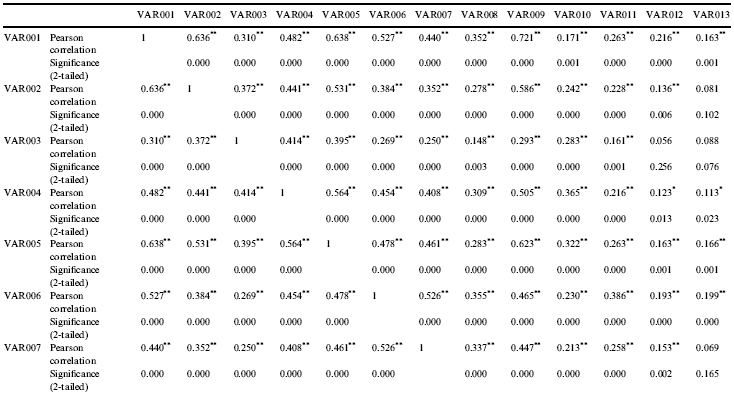

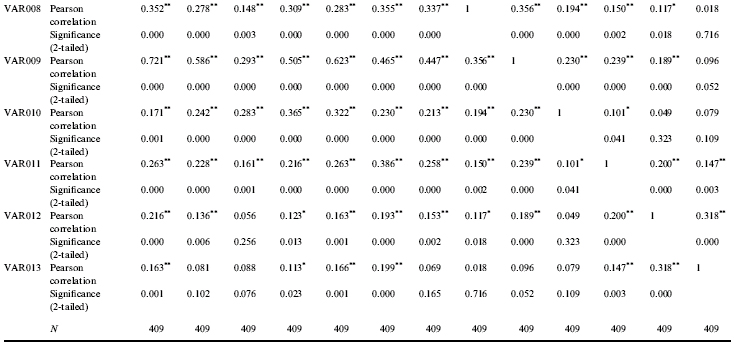

The sample suitability test, which identifies the degree of cross-correlations among the variables, was performed for each item of the social disclosure index for the period from 2005 to 2009. The results obtained are all higher then 0.60, which shows a good individual fit for the items. Corroborating the good fit among the items, Pearson partial correlations were computed among the variables for the whole sample period, resulting that 141 items among 156 achieved significant levels ranging from 1% to 5%.

The results of tests previously applied (Bartlett Sphericity, KMO, sample suitability and Pearson correlation) were considered adequate for performing the exploratory factor analysis. In this stage, the exploratory factor analysis permitted the identification of common factors based on the characteristics of each item of the social disclosure index, their explanatory power and their importance within the group forming the final index. Based on the latter, the joint reliability of the items, verified by means of their factor weight and allocation among factors, will be determined.

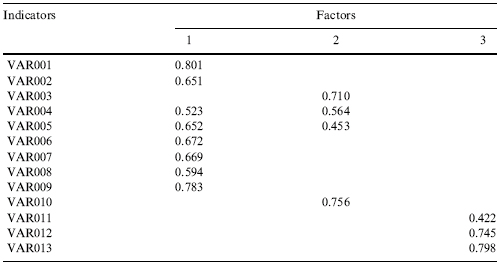

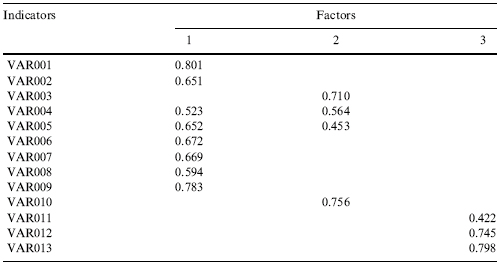

For extracting the factors, the latent root criterion (Kaiser) with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, varimax rotation, and the choice of factor weights greater than 0.40 were utilized (Table 3).

Table 3. Factor Composition in the Period 2005–2009.

Based on the factor composition and considering their factor weights (greater than 0.40) and their presence in the same factor in all years, we found stability and consistency for the eight following items:

- Factor 1: var001 – relationship of social programs with the firm’s values; var002 – assessment of local demands; var006 – financial resources assigned to social programs; var007 – economic and/or financial value of human resources involved in voluntary programs; var008 – economic and/or financial value of material resources assigned to social programs; and var009 – social outcomes obtained from social programs;

- Factor 2: var003 – description of aspects necessary for improving social outcomes obtained from social programs; var010 – future cash-flow forecasts of the assignment of resources in social programs;

- Factor 3: var011 – distribution of value added; var012 – availability of social responsibility reports; and var013 – frequency of disclosure of social responsibility reports.

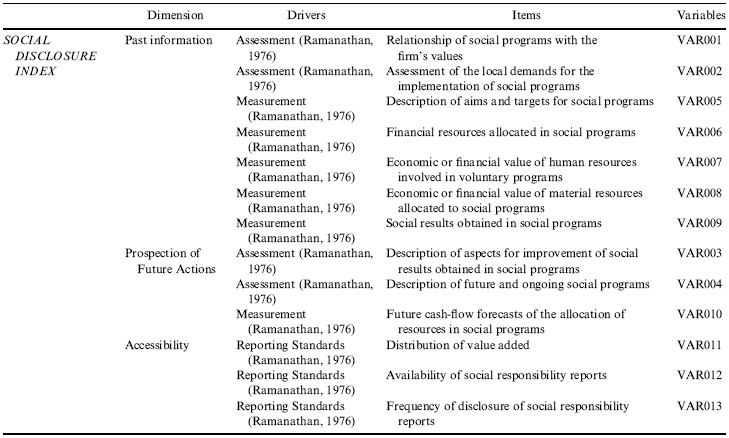

Considering the items comprising Factor 1, the predominant characteristic of the items classified within this factor is that the information is related to a past period (past information), while the predominant characteristic of the items in Factor 2 is characterized by information related to a future moment (prospecting future actions). Finally, Factor 3 is related to formal aspects of the disclosure of information (accessibility), that is, availability, frequency, and reporting standards. Accordingly, it was possible to identify Factor 1 as past information – an expression that best represents the pieces of social information being transmitted, since it holds aspects predominantly attached to past or already occurred facts.

With respect to the items which had their factor loads divided into two factors (Factors 1 and 2) during the sample period (var004 and var 005), we considered their factor load, the factor characteristic, as well as their behavior (outcome) within the sample period (2005–2009). The item description of future and ongoing social programs (var004) was classified in Factor 1 (factor load = 0.523) and in Factor 2 (factor load = 0.564). Under the qualitative viewpoint, this item has a predominant predictive aspect related to social actions that will be carried out the following year, although it also contains aspects of actions directed to existing social programs.

We were able to identify for the set of results referring to the period (2005–2009) a larger frequency falling within the restrict category (54%), followed by low (21.3%), wide (14.9%), and medium (9.8%) categories. Since the restrict category means absence of information, we set the higher disclosure parameter to the low category (the second highest), which in this item means that the firm is committed to carry on with the social programs, without, however, identifying which they are. Therefore, the predominant characteristic in this item expresses the organizations’ future actions with respect to the accomplishment of social programs, although they are predominantly related to existing programs. Besides this characteristic, we find a factor load slightly higher in Factor 2 (0.564) as compared to Factor 1 (0.523), by observing the factor loads.

Considering the factor loads, the qualitative analysis, as well as the item’s characteristic itself, we decided to assign it to Factor 2 – prospecting future actions. The item description of aims and targets for social programs (var005) was classified in Factor 1 (factor load = 0.652) and in Factor 2 (factor load = 0.453). Under the viewpoint of its characteristic, we find that since it refers to the aims of the social programs, in a first moment it carries information predominantly attached to a decision already taken since the aim of a social program must persist for a certain period.

When there is a description of the targets defined for the following year, besides conveying itself a past aspect related to the aim, this item also becomes a future driver. By analysing the outcomes obtained in the period, we verify that the firms disclose predominantly their aims only (low outcome = 53.8%), while only 17.1% of the outcomes are classified as medium/wide, which indicate targets either by area of activity or by social program. Hence, considering the observed outcomes with predominance in the disclosure of the aims of existing social programs, as well as with a higher factor load (0.652) in Factor 1, the item description of aims and targets for the social programs (var005) was assigned to Factor 1 – past information.

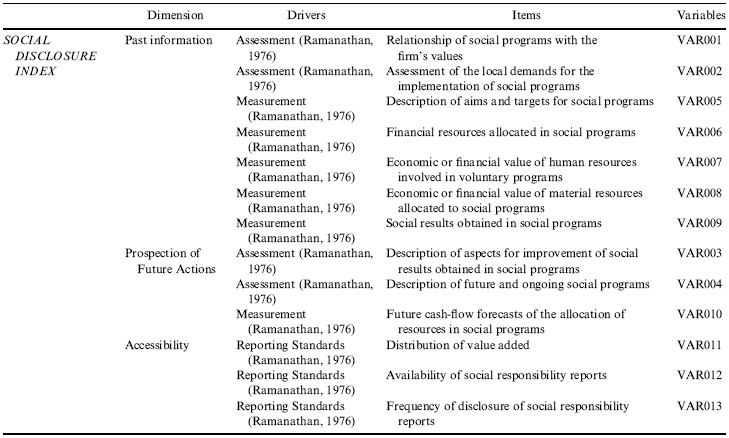

With the adjustments carried out based on the exploratory factor analysis, the social disclosure index can be structured as Table 4.

Table 4. Social Disclosure Index Adjusted after Exploratory Factor Analysis Existing.

The dimensions past information, prospecting future actions and accessibility represent the intrinsic characteristics of each item, while assessment, measurement and reporting standards characterise the item with respect to the way it shows itself, acting as drivers for the data collection.

Additionally, as a step in the validation by means of factor analysis, Hair et al. (2005) suggest an analysis based on the sample segmentation and analysis of factors excluded by means of this subsample. For such an analysis of years 2005, 2008, and 2009 the data of which presented a best fit as verified by the KMO test (2005 – 0.8447; 2008 – 0.8625, and 2009 – 0.8674) was performed. The sample suitability test which yielded results higher than 0.50, thus revealing good individual fits, was performed. The Pearson partial cross-correlation matrix was also computed for the years 2005, 2008, and 2009, which corroborated the good fit among the items, presenting significance levels between 1% and 5%.

Since the robustness tests presented adequate results, a factor analysis was carried out for each year (2005, 2008, and 2009), which yielded factor loads higher than the minimum level used in the test (>0.40). The distribution of the items within their respective factors was analysed, and the results were the same as when the whole period (2005–2009) was examined, with the exception of var011 – distribution of value added.

With respect to this item’s result, one can observe that there is a distribution between Factor 1, the characteristic of which is related to past information (factor loads: 2005 = 0.477; 2009 = 0.501) and Factor 3 (factor loads: 2005 = 0.418; 2008 = 0.682; 2009 = −0.409), which is related to accessibility and reporting standards. With respect to this point, it should be mentioned that this situation was expected, since such information is related to both characteristics. However, we call attention to the fact that in 2009 that factor load presented a negative value.

Despite the ambiguity found in these results, the analysis of the whole sample from 2005 to 2009 shows a relevant factor load (0.422) and an absence of results in other factors. Considering its characteristics and the result found for the whole sample period (2005–2009), we believe that the assignment in dimension 3 – accessibility, is adequate.

As a consequence of the procedures adopted and the results obtained, we consider that the validation by means of the sample segregation was accomplished, since the stability of the factors extracted in the periods analysed (2005, 2008, and 2009) was found, presenting no divergence with respect to the model presented in the previous chart. In addition to the exploratory factor analysis, but still within the phase of validating the social disclosure index, Cronbach’s alpha, which assesses the internal consistency of the whole scale, was calculated (Table 5).

Table 5. Reliability Tests (Cronbach’s Alpha) for the Period 2005–2009.

According to the Cronbach’s alpha estimates obtained for the whole sample period, we can attest that the social disclosure index presents a good internal consistency, since all alphas are higher than 0.80.

Confirmatory Test Validation

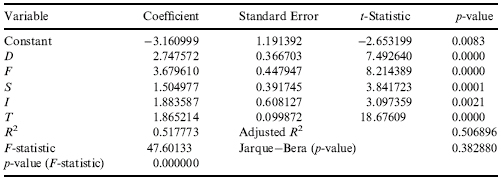

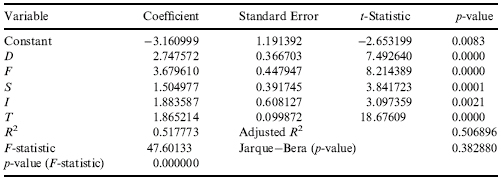

As a final phase of validation of the social disclosure index, a significance test was performed by means of a panel-data linear regression between the determinants of social disclosure and the level of disclosure for the period 2005–2009. The panel-data regression estimation was performed under fixed effects, since the Hausman test previously performed indicates the rejection of the null of random effects with a p-value of 0.0187. The results of the panel-data regression estimation are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Results of the Estimation of Panel-Data Fixed Effects of the Determinants of Social Disclosure on the Social Disclosure Index for the Period 2005–2009.a

where Dit = auditing in the ith firm in period t; Fit = social responsible funds of the ith firm in period t; Si = industrial sector of the ith firm in period t; Iit = internationalization of the ith firm in period t; Tit= size of the ith firm in period t; βi = coefficients of the explanatory variables, i = 1, …, 6.

aCorrected by White’s heteroscedasticity covariance matrix.

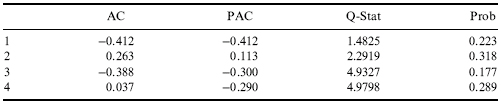

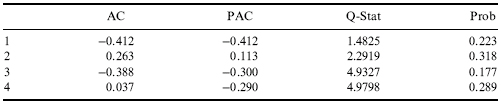

It should be mentioned that leverage was found to be non-significant at the 5% level and therefore excluded from the regression. This result is consistent with previous research showing that a higher leverage does not necessarily imply that a firm presents a higher level of social disclosure (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Reverte, 2009). The final results presented in Table 6 show that the regression is statistically significant as a whole (F-statistics’ p-value < 0.05). The results of the Q-test do not suggest rejection of the null of no autocorrelation and, since all p-values are higher than 0.05 (see Table 7).

Table 7. Q-test for the Autocorrelation of the Residuals.

In order to check for stationarity of the series, the unit-root test of Levin, Lin, and Chut was carried out, resulting in the rejection of the null of unit roots, which means the series are stationary. Besides, there is evidence that regression residuals are normally distributed, since Bera–Jarque test’s p-value is greater than 0.05, as required by OLS implicit assumptions. Because of the detected evidence of heteroscedasticity, the regression was estimated using White’s covariance matrix, which yields robust coefficients when heteroscedasticity holds. The results show that the coefficients of all the variables remaining in the regression are significant below the 1% level and can thus be considered relevant in explaining the level of social disclosure. This means that size, industrial sector, internationalization, auditing, and social responsible funds as a whole jointly explain 51% of the variations on the level of social disclosure, as shown by the regression’s R2.

In the regression analysis performed, the signs obtained for the coefficients of the explanatory variables are all positive, meaning that all of these variables contribute positively to raise the social disclosure index, which was as expected and consistent with the extant literature (Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Campbell et al., 2006; Chih et al., 2010; Clarkson et al., 2008; Gamerschlag et al., 2011; Reverte, 2009; Richardson & Welker, 2001; Simnett et al., 2009). This means that size, industrial sector, internationalization, auditing firm and listing of social responsible funds are determinant factors to explaining the level of social disclosure.

The variable demonstrated to be the strongest determinant of social disclosure is to be listed with social responsible funds, which had a coefficient greater than those of variables usually considered more relevant, such as size, industry, and internationalization. A possible explanation is that to be listed with this type of fund the firm has to revise all its internal policies, strive for a great improvement of its social responsibility actions, and consequently also of its disclosing policy. Additionally, it is also remarkable that the choice of the auditing firm has the second greatest impact on the social disclosure index. This result corroborates the idea that when firms submit themselves to assessment by one of the four largest auditing firms, they are also looking for better disclosure practices (Simnett et al., 2009).

REFERENCES

Al-Tuwaijri, S. A., Christensen, T. E., & Hughes, K. E. (2004). The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(5–6), 447–471.

Anderson, J. C., & Frankle, A. W. (1980). Voluntary social reporting: An iso-beta portfolio analysis. The Accounting Review, 55(3), 467–479.

Bardin, L. (1977). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa, Edições 70.

Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2008). Factors influencing social responsibility disclosure by Portuguese companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(4), 685–701.

Brown, W. O., Helland, E., & Smith, J. K. (2006). Corporate philanthropic practices. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(5), 855–877.

Bushee, G., & Leuz, C. (2005). Economics consequences of SEC disclosure regulation: Evidence from the OTC bulletin board. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2), 233–264.

Campbell, D., Moore, G., & Shrives, P. (2006). Cross-sectional effects in community disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(1), 96–114.

Carr, I., & Outhwaite, O. (2009). Investigating the impact of anti-corruption strategies on international business: An interim report. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1410642. Accessed on September 18, 2009.

Chih, H., Chih, H., & Chen, T. (2010). On the determinants of corporate social responsibility: International evidence on the financial industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(1), 115–135.

Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4), 303–327.

Coy, D., & Dixon, K. (2004). The public accountability index: Crafting a parametric disclosure index for annual reports. The British Accounting Review, 36(1), 79–106.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Dahlman, C. J. (1979). The problem of externality. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(1), 141–162.

Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations. Accounting and Business Research, 26(3), 187–199.

Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2009). Voluntary non-financial disclosure and the cos of equity capital: The case of corporate social responsibility reporting. Retrieved from SSRN: papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1343453. Accessed on April 7, 2010.

Epstein, M. J., & Freedman, M. (1994). Social disclosure and the individual investor. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 7(4), 94–109.

Gamerschlag, R., Moeller, K., & Verbeeten, F. (2011). Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Review of Managerial Science, 5(2–3), 234–262.

Gray, R., Javad, M., Power, D. M., & Sinclair, C. D. (2001). Social and environmental disclosure and corporate characteristics: A research note and extension. Journal of Business Finances & Accounting, 28(3), 327–356.

Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47–77.

Hair, J. F., Babin, B., Money, A. H., & Samouel, P. (2003). Essentials of business research methods. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hair, J. F., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2005). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hammond, K., & Miles, S. (2004). Assessing quality assessment of corporate social reporting: UK perspectives. Accounting Forum, 28(1), 61–79.

Haydel, B. F. (1989). A Administração Estratégica de Programas de Responsabilidade Social em Empresas Multinacionais: Percepções da Alta Diretoria. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 3(29), 5–29.

Heal, G. (2004). Corporate social responsibility – An economic and financial framework. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=642762. Accessed on May 28, 2009.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.

KPMG International. (2008). KPMG International survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2008. Retrieved from http://kpmg.com. Accessed on August 2, 2009.

Machado Filho, C. A. P., & Zylbersztajn, D. (2003). Responsabilidade Social Corporativa e a Criação de Valor para as Organizações. Working Paper No. 03/024, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo, Universidade de São Paulo, 31 March 2010.

Malhotra, N. K. (2003). Marketing research: An applied orientation (4th ed.). London: Prentice Hall.

Milani Filho, M. F. (2008). Responsabilidade Social e Investimento Social Privados: Entre o discurso e a evidenciação. Revista Contabilidade e Finanças, 19(47), 89–101.

Naser, K., & Nuseibech, R. (2003). Quality of financial reporting: Evidence from the listed Saudi nonfinancial companies. The International Journal of Accounting, 38(1), 41–69.

Orlitzky, M., & Benjamin, J. D. (2001). Corporate social performance and firm risk: A meta-analytic review. Business Society, 40(4), 369–396.

Peliano, A. M. T. M., Prata, A. C. A. C., Chaves, A. P. de M. G., Lesnau, G., Rose, E. C. P., … Matos, R. S. (2002). A iniciativa privada e o espírito público: Um retrato da ação social das empresas no Brasil. Brazil: Ipea.

Peliano, A. M. T. M., Prata, A. C. A. C., Chaves, A. P. de M. G., Lesnau, G., Rose, E. C. P., … Matos, R. S. (2006). A iniciativa privada e o espírito público: A evolução da ação social das empresas privadas no Brasil. Brazil: Ipea.

Pereira, A. (2006). Guia Prático de Utilização do SPSS – Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais e Psicologia (6th ed.). Lisboa: Edições Silabo.

Poddi, L., & Vergalli, S. (2009). Does corporate social responsibility affect the performance of firms? Nota Di Lavoro, 52, 1–45. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1444333. Accessed on April 5, 2010.

Porter, M. E., & Kraemer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68.

Ramanathan, K. V. (1976). Toward a theory of corporate social accounting. The Accounting Review, Sarasota, 51(3), 516–528.

Reverte, C. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 351–366.

Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (2004). Accounting theory (5th ed.). London: Thomson Learning.

Richardson, A. J., & Welker, M. (2001). Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost capital of equity capital. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26(7), 597–616.

Richardson, A. J., Welker, M., & Hutchinson, I. R. (1999). Managing capital market reactions to corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1(1), 17–43.

Rizx, R., Dixon, R., & Woodhead, A. (2008). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A survey of disclosure practices in Egypt. Social Responsibility Journal, 4(3), 306–323.

Rodriguez, L. C., & LeMaster, J. (2007). Voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosure – SEC “CSR seal of approval”. Business & Society, 45(3), 370–383.

Saiia, D. H., Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2003). Philanthropy as strategy: When corporate charity “begins at home”. Business & Society, 42(2), 169–201.

Saudagaran, S. M., & Biddle, G. C. (1995). Foreign listing location: A study of MNCs and stock exchanges in eight countries. Journal of Informational Business, 23(2), 319–341.

Simnett, R., Vanstraelen, A., & Chua, W. F. (2009). Assurance on sustainability reports: An international comparison. The Accounting Review, 84(3), 937–967.

Smith, J. van der, L., Adhikari, A., & Tondkar, R. H. (2005). Exploring differences in social disclosure internationally: A stakeholder perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(2), 123–151.

Udayasankar, K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and firm size. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 167–175.

Unerman, J. (2000). Methodological issues: Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(5), 667–680.

Utting, P. (2002). Regulating business via multistakeholder initiatives: A preliminary assessment. Voluntary Approaches to Corporate Responsibility: Readings and a Resource Guide (pp. 61–130). Geneva: UNRISD

APPENDIX A: PEARSON CORRELATION MATRIX BETWEEN VARIABLES OF SOCIAL DISCLOSURE INDEX

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

APPENDIX B: LIST OF COMPANIES COMPONENTS OF THE STUDY