French soldiers work to prepare barbed-wire defences on the Chemin des Dames. It was bitter fighting around the heavily fortified German defences on the dominating ridge that caused the failure of the Nivelle Offensive.

Having secured governmental approval for his scheme for a war-winning offensive, General Robert Nivelle raised the hopes of the French people and military to heights not seen since 1914. Instead of delivering a quick victory, though, his offensive produced only futility, driving the French Army into mutiny and changing the strategic balance on the Western Front.

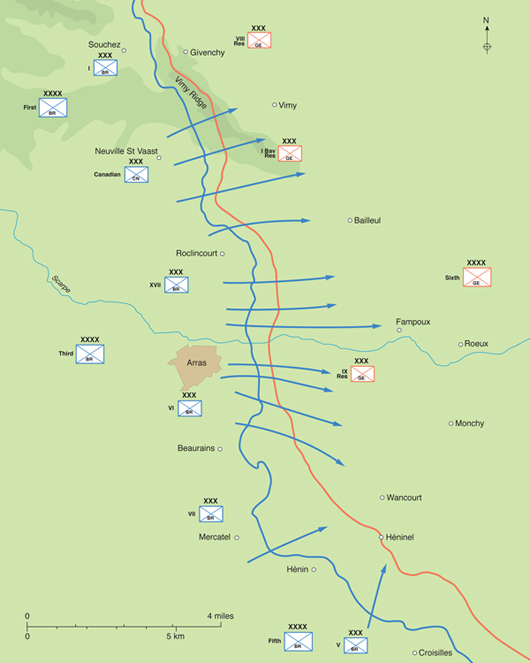

The main British effort as part of Nivelle’s overall offensive scheme for 1917 involved an attack on German lines near Arras, where six divisions of the German Sixth Army, commanded by General von Falkenhausen, faced 14 divisions of the British First Army, under the command of General Sir Henry Horne, Third Army, under the command of General Sir Edmund Allenby, and the Fifth Army, under the command of General Sir Hubert Gough. South of the river Scarpe, which bisected the battlefield, the Germans held the important high ground of the Monchy Spur, which formed part of the vaunted Hindenburg Line. North of the Scarpe were the imposing heights of the Vimy Ridge, which was six kilometres (four miles) long, running from northwest to southeast, and honeycombed with German defences.

General William Birdwood, commander of IANZAC Corps, which bore the brunt of the brutal fighting around Bullecourt in the Battle of Arras.

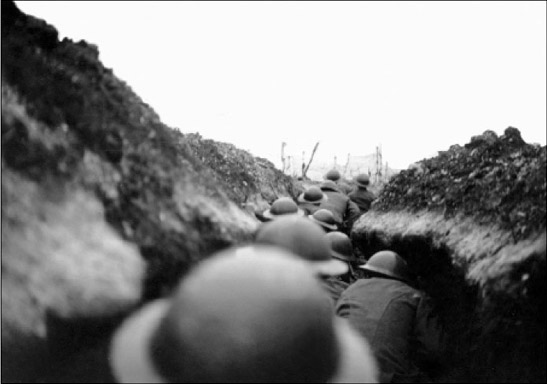

The most important feature of the battlefield, though, was the historic fortress town of Arras, the centre of which was only 1829m (2000 yards) from the front-line trenches. The proximity of the town offered Allenby and the Third Army a distinct advantage, for underneath Arras ran a network of tunnels, from which stone had once been quarried, and an extensive sewer system. Allenby’s men expanded and linked the tunnels and sewers, even adding electric lighting and an underground light railway. The extensive labyrinth was capable of enabling 30,000 men to move up to their jumping-off points for the attack in safety and secrecy. North of Arras, near the Vimy Ridge, the First Army and Canadian Corps achieved similar results by digging 12 massive tunnels, the longest stretching 1722m (1883 yards) into the chalky soil, which allowed assault forces to assemble free from German observation.

South of the Scarpe, the Hindenburg Line relied on new defence-in-depth techniques perfected in the later stages of the Battle of the Somme. Wherever possible the Germans situated their defences on the reverse slopes of hills, thus denying observation to the attacker. Bristling with machine-gun nests, the frontline defences were only thinly manned, and were made up of a system of mutually supporting strongpoints designed to cause maximum carnage to the attacker, while exposing the least number of defending troops to artillery fire. After exacting a heavy toll, the defending forces would then fall back and draw the attackers, bloodied and exhausted, forwards to their doom in the form of massive counterattacks from the second line of defences, known as the battle zone. The German defensive advancements, though, were only unevenly applied, and, as a result, to the north of the Scarpe and on Vimy Ridge, the German trenches were located on the forward slope, heavily manned and well within range of the coming British bombardment. Additionally, in this region German reserve formations were located too far to the rear to have an immediate effect on the battle.

The French artillery piece Canon de 105mm Schneider, also known by its designation L 13 S. Although little used at the outbreak of the war, the L 13 S proved to be much more effective than the lighter French 75mm in trench warfare.

The British offensive at Arras, with its dramatic seizure of the Vimy Ridge, demonstrated the effectiveness of limited, bite-and-hold tactics. The British Third Army, under General Sir Edmund Allenby, attacked in the centre, whilst the First Army, spearheaded by the Canadian Corps under General Sir Julian Byng, attacked to the north. Fifth Army, under General Sir Hubert Gough, held the southern end of the line.

A Canadian artillery team in action at Vimy Ridge during the Battle of Arras. The artillery barrage that accompanied the British attack at Arras was three times stronger than that utilized on the disastrous first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

The preparation for the Battle of Arras, which fell mainly to Horne and Allenby, demonstrated that the BEF had learned much in its trials during the Somme, especially in artillery planning. British artillerists were now technologically adept professionals instead of gentlemen amateurs who, though there remained a certain amount of trial and error, took great care in their planning, especially against the defences of Vimy Ridge. The exact length of trench to be assailed had been calculated, and the appropriate artillery assigned to the task at hand. Heavy guns concentrated on German rear positions, bombarding the German artillery and any attempts at reinforcement, while medium guns dealt with German wire and trenches. At the moment of attack, the artillery would provide a creeping barrage augmented by a secondary barrage of machine-gun bullets and light howitzer shells, which gave the advancing infantry such effective protection that one sergeant informed his men:

‘All you have got to do is to hang on to the back wheel of the barrage, just as if you were biking down the Strand behind a motor bus; carefully like, and not in too much of a hurry; and then when you come to Fritz, and he holds up his hands, you send him back to the rear.’

Scientific advances in gunnery also improved counterbattery work, while industrial advances on the home front meant that the quality of British munitions had risen markedly since the Somme, which provided the artillerists with much more sensitive and effective fuses and many fewer dud rounds. Finally, though, sheer numbers told the true story of artillery success at Arras. The attacking forces had 2827 guns, of which 963 were of heavy calibre, to cover an attack frontage of 21km (13 miles). At Vimy Ridge, the Canadian Corps had 377 heavy guns on a front of just over six kilometres (four miles), or one heavy gun for every 18m (20 yards) of front. Because of the military and industrial advances, the artillery barrage that accompanied the Arras attack was three times as strong as that employed on the first day of the Somme, in addition to being much more accurate and lethal.

The artillery of World War I was prodigiously strong, with the largest pieces, including the British 12in siege howitzer, firing shells that weighed nearly 456kg (1000lb) to a range of 14km (nine miles). However, at first artillerymen did not know how the conditions around them could affect the flight of their shell. Later studies, as artillerists learned their craft, indicated the price paid through such ignorance. If a gun utilizing indirect fire in 1916 fired 100 shells at a stationary target, 50 of those shells would miss the target entirely. The remaining ‘hits’ would fall into a zone 37m (40 yards) long and five metres (five yards) wide. The value of such ‘hits’, though, was quite limited, considering the fact that trenches were only a metre in width and machine-gun nests only a bit larger. Thus, even the vast majority of ‘hits’ had but little effect on entrenched defenders. Of the 100 shells fired, only two would be direct hits on such a small target, and only a very tiny percentage of those direct hits would be so accurate as to penetrate the trench and destroy a bunker under it. Add to this the fact that one of those direct hits was likely to be a dud round, and the ineffectiveness of artillery from 1915 to 1917 becomes easier to understand.

The British attack at Arras not only had to be powerful enough to draw German attention away from the French preparations further south, but also, as part of a wider Allied plan to achieve ultimate victory, had to aim at a breakthrough that would augment and complement Nivelle’s own planned rupture of the German defences along the Chemin des Dames. The resulting plan called for the First Army to guard the flank of the offensive by seizing Vimy Ridge, while the Third Army attacked towards Cambrai. Haig held an infantry corps and cavalry units in reserve to exploit any success.

Defensive works at Vimy Ridge. Unlike other areas of the Arras battlefield, where the main defences were positioned to the rear, the German defences at Vimy Ridge were located too far forwards and did not rely on defence-in-depth techniques, making them vulnerable to attack.

Although Horne and Allenby advocated a whirlwind bombardment, Haig intervened in favour of a longer artillery barrage, which, in five days, fired over two and a half million shells into the German lines. Although the steady bombardment indicated that a major British offensive was in the offing, due to the massing of attacking forces under cover of the tunnel networks at Arras and near Vimy Ridge, the Germans remained unaware of the timing of zero hour until the British and Canadian infantry were nearly across no man’s land.

Men of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) advance to the attack. Although losses remained high, the success of the BEF in the early stages of the Battle of Arras indicated that the infantry was returning to a prominent place on the World War I battlefield.

In the north, the Canadian Corps, under the capable command of General Sir Julian Byng, achieved one of the most notable successes to date of the entire war. Backed by devastating support from nine heavy artillery groups and covered by an effective machine-gun barrage, the Canadians burst forth from their concealment and assaulted Vimy Ridge, which had withstood multiple French attacks in 1915 and had been the site of some of the war’s most bitter fighting.

Royal Aircraft Factory SE 5a. One of Britain’s most successful fighter aircraft of the Great War, the SE 5a was powered by a 150hp engine, and carried aVickers machine gun that was timed to fire through the whirling blades of the propeller.

Having rehearsed their assault in painstaking detail, the Canadians surged forward, unperturbed by a late season snowstorm. The 3rd and 4th divisions on the Canadian left advanced so quickly that the attacking soldiers were into the German trenches before the German machine-gunners had even manned their weapons. Surprise was so complete that the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles captured 150 Germans who were only half dressed, and many still had their shaving cream on their faces. Many Canadian soldiers actually advanced beyond their final objective, because the German trench line that marked their halt point had been so thoroughly obliterated by the artillery barrage as to be unrecognizable.

On the Canadian right flank, surviving German strongpoints, including an especially troubling German machine-gun nest that cut down the Canadians even as they emerged from the exit of the Tottenham Tunnel, slowed the advance of the 1st and 2nd divisions. Demonstrating tactical flexibility, Byng’s men utilized combined infantry and artillery attacks to neutralize the troublesome defensive emplacements and captured the German defensive redoubt of Hill 135 in heavy and sometimes hand-to-hand fighting. Gathering momentum, the Canadians burst forward into the German artillery lines, and in one case men of the Canadian 1st Brigade captured German guns that had been abandoned so quickly that the luncheons in the officers’ dugout were still warm and untouched on the table. On another occasion the City of Winnipeg Battalion came across a German artillery battery that opened fire when the Canadians were only 46m (50 yards) from it. Raising a cheer, the Winnipeggers charged down the slope and either bayoneted or captured the German gunners.

On 31 May 1915, a new era of modern warfare had begun when the German Zeppelin LZ38 flew over London and dropped its cargo of high explosive. In total Germany mounted 53 Zeppelin raids on Great Britain, dropping over 5700 bombs and killing 556 civilians. However, the Zeppelins were slow moving, carried few bombs and proved extremely vulnerable to anti-aircraft defences. By 1917, though, the Germans had developed the Gotha bomber, which was capable of carrying a heavier bomb load to strike at the United Kingdom. The first Gotha raid took place on 13 June 1917, in which 20 bombers dropped 72 bombs near Liverpool Street Station in London. Casualties in the raid reached 162 dead (including 18 children when a bomb struck a school) and 432 wounded. The raids continued through August 1917, dropping a total of 33,112kg (73,000lb) of bombs and causing 1364 casualties before British anti-aircraft defences forced the Germans to bomb only at night. Although the raids were limited in character, the panic that they caused led many inter-war thinkers to believe that more effective and numerous bombers might well prove decisive in war.

A British 18-pounder field gun in action at Arras. The standard field gun of the BEF during the Great War, the 18-pounder had a range of 5966m (6525 yards). As denoted by the stockpile of ammunition to the left, by 1917 British industry had made possible the lavish use of firepower.

On the Canadian left, at 3.15pm, men of the Nova Scotia Highlanders moved to attack the last German holdout positions atop Hill 145, the highest point of Vimy Ridge, hoping to seize the dominating position before nightfall. Due to communications problems, the Highlanders never received word that their brigadier had called off their artillery cover as being too dangerous. The tide of Canadian victory was so complete, though, that even without the protective barrage, the Highlanders quickly overran the hill, taking a number of German prisoners, and completing the capture of Vimy Ridge.

The seizure of Vimy Ridge in a single day was, in many ways, a testament to the strength of Canadian arms and will, one so significant that it remains celebrated as a landmark event in the birth of the Canadian nation. At a cost of 11,000 casualties, the Canadians had seized a German position that had hitherto been impregnable; they had also taken 3600 prisoners and captured 36 artillery pieces in the process. However, the fighting at Vimy Ridge was but a part of the wider offensive at Arras, where further to the south advances by British and Australian forces demonstrated that the entire BEF both had become more professional and had undertaken a considerable military learning curve since the bitter fighting at the Somme.

To the south of Vimy Ridge, Allenby’s Third Army, in an operation that rivalled that of the Somme in both attack frontage and in the number of divisions involved, achieved a level of success that even exceeded that of the Canadian Corps; a success judged by Cyril Falls, the official historian of the battle, as, ‘from the British point of view one of the great days of the War. It witnessed the most successful British offensive hitherto launched ... [and was] among the heaviest blows struck by British arms in the Western theatre of war.’

In the British centre, benefiting from the proximity of the tunnels of Arras, where one battalion diarist remarked that it was possible to ‘get from the crypt of the [Arras] Cathedral to under the German wire without braving one shell in the open’, VI Corps enjoyed the support of nine heavy artillery groups, and faced the traditional German forward defences rather than the more sophisticated defence-in-depth fortifications. Having achieved tactical surprise in the wake of thorough artillery preparation, VI Corps advanced under cover of a creeping barrage and smokescreen and quickly achieved all of its goals. Moving forwards nearly three kilometres (two miles), men from the 12th and 15th (Scottish) divisions achieved the summit of Observation Ridge and found themselves looking upon Battery Valley below. In the words of the official historian:

‘As they swept down the eastern slope of the Observation Ridge, a dramatic scene of a type rare in this theatre of war unfolded. The whole of Battery Valley was dotted with German artillery: some batteries already abandoned; some, having got their teams up, making off as fast as they could; but several others firing point-blank at the British Infantry at ranges of only a few hundred yards. Their blood up ... [they] advanced by short rushes. ... Pushing on the Essex took nine guns and the R. Berkshire no less than 22, as well as a number of prisoners.’

With its heightened lethality and static nature, the Western Front was characterized by battlefields strewn with the dead and dying. Many veterans likened battle in World War I to fighting in an open graveyard.

In World War I, offensives often gained only little ground while lasting for months, leaving little time to gather the wounded or bury the dead. As the battles progressed, soldiers were left to fight among, live among and dig new trenches through the bodies of their one-time foes and their own deceased comrades. The stench of the battlefields was nauseating, and Private Thomas Mclndoe recalled:

‘There was a dead Frenchman once. I saw him. His body was decomposed. And it nearly made me sick. There was his arm ... he’d been on the receiving end of something fairly big. And as I saw him I thought, “Christ! We could bury him. We could cover him over”, which eventually we did. And this bloody great rat ran out of his arm here after supping up, he’d been feeding on his arm here, see? Bloody great thing ran out there, nearly made me sick. I thought to myself, “Oh, filthy things! Oh Dear!”‘

The greatest gains of the day, though, fell to XVII Corps to the north of the river Scarpe. Following in the wake of a punishing barrage, the 9th Division quickly pressed on to its final objective, and later allowed the 4th Division to pass through, which achieved an advance of six kilometres (three and a half miles), the largest gain made by any belligerent force on the Western Front since the onset of trench warfare. In several places British forces had broken through the German line of defences, demonstrating the BEF mastery of the set-piece battle. The advance, which had seized the high ground and allowed British forces to overlook open and undefended territory beyond, seemed to offer a fleeting opportunity for exploitation. If any opportunity did exist, though, the cavalry had been held too far behind the lines to play a substantial role in the fighting.

Although the seizure of Vimy Ridge and the advance of XVII Corps were cause for optimism, difficulties on other sectors of the front tempered the British victory. On the right flank of the Third Army, VII Corps attacked the northern extremities of the Hindenburg Line. Facing the brunt of the German defences, especially around Telegraph Hill, and with many of its supporting tanks bogged down in terrain ruined in the German withdrawal and further churned up by artillery fire, VII Corps made only sporadic gains, a sobering example of the capabilities of the new German form of defence amidst a day otherwise marked by unmarred Allied success.

Careful artillery and infantry preparation had enabled substantial, though imperfect, British and Canadian gains on the first day of the attack at Arras. However, the bitter tactical reality of battle on the Western Front was that the very tools that made an advance possible lost much of their value after the opening round of an offensive. After the initial advance, the artillery, on which so much of any successful attack depended, had to move forwards, along with prodigious supplies of artillery shells –slow and laborious tasks made all the more difficult by the fact that the artillery had destroyed much of the ground that it now had to traverse. Since the attackers lacked a weapon of exploitation to maintain the momentum of an advance, as the artillery struggled forwards, German reinforcements rushed to the scene, and created new defences that again required careful preparations to overthrow. It was indeed the central riddle of World War I. Defenders could react more quickly to developments than could attackers, causing offensives to stall.

Because of the inexorable tactical logic of World War I, the British and Canadian assaults on 10 April met with diminishing returns. The all-important artillery barrage and covering fire, which had done so much to make the gains of the previous day possible, were much more limited in both weight and accuracy as the artillery struggled forwards. With minimal covering fire and facing new German defensive positions, the exhausted British and Canadian infantry made few additional gains against gathering German reserves. Allenby, though, knew little of the failure of the renewed attack. Denied information from spotter aircraft due to worsening weather, Allenby mistakenly declared to his commanders that, ‘Third Army is now pursuing a defeated enemy and risks must be freely taken’. The orders sent British and Canadian forces forward again on 11 April, including cavalry efforts at exploitation that were two days too late. Although British forces did succeed in capturing the defended village of Monchy-le-Preux, the once-promising attack had stalled.

A French infantry sergeant carrying the 8mm Chauchat M1915 light machine gun. Promised quick victory by their new commander, General Robert Nivelle, French infantry instead suffered through another seemingly futile assault at the Chemin des Dames, and morale crumbled.

General Robert Nivelle’s ambitious plan in 1917 called for a British diversion at Arras to allow the main French assaults entirely to dislocate the German defences on the Western Front, which would result in the restoration of a war of movement and the eventual collapse of the German position.

While initial advances in the centre and north of the British line portended well for the future, in the far south of the area of operations, greater difficulties had emerged, where the Fifth Army, under Gough, faced the might of the Hindenburg Line proper and depended on a tenuous logistic network that stretched through the area of desolation left behind after the German withdrawal. Since Gough’s operation was subsidiary to that of Allenby, Fifth Army received the least weight of shell in its artillery preparation, which left much of the German’s barbed wire uncut and their defences intact. With the twin objectives of capturing the strongpoint of Bullecourt and aiding Third Army in its rupture of the German lines, Gough initially put off his assault due to the poor artillery preparation. However, the nearly uniform success enjoyed by Allenby’s forces at the outset of his attack left Gough anxious to play his role in what seemed to be a great victory, an enthusiasm that served to dampen his justifiable fears.

British troops coming out of the line after the Battle of Arras. Benefiting from elaborate planning, the initial British advances were stunning. However, the battle soon stagnated, indicating that breaking through enemy trench systems remained impossible.

Believing that the Germans on his front would withdraw due to the successes achieved by Third Army, and convinced that the relatively few tanks on hand could deal with the wire left uncut by the artillery, Gough gave the go ahead for the attack, over the objections of General William Birdwood, whose I ANZAC Corps would bear the brunt of the coming battle. The tanks, though, were late in arriving, necessitating a further postponement of the operation until 11 April. Even with the extra time, the tanks proved to be unreliable: several broke down or were put out of action by German fire and none made it to the German front lines, leaving the Australian infantry alone to breach the intact German wire. Amazingly, the Australians persevered, and on much of a three-kilometre (two-mile) front captured the German front line, with some units even achieving a foothold in the German second line of defences. However, the Germans mounted fierce counterattacks and, with sparse artillery cover and ammunition running low, the Australians withdrew from their meagre gains with heavy losses. The 4th Australian Brigade indeed had almost been destroyed, losing 2258 out of 3000 men involved in the attack.

A section of a German defensive network. In response to the heavy bloodlettings of the Somme and Verdun, the Germans developed an intricate defence-in-depth system, designed first to tire and then to shatter Allied attacks. This system worked as designed against the Nivelle Offensive.

The Battle of Arras had seemingly run its course, demonstrating not only the power of attackers to achieve a ‘break-in’ to defensive networks but also the difficulties of ever achieving a ‘breakthrough’ amid the tactical and logistical realities that formed the strategic centre of World War I. Haig would have been well served to stop the offensive after 12 April; however, he did not. The attack would continue into the month of May, not because Haig had any faith that continued assaults near Arras would achieve substantial gains, but because the BEF had to continue to play its ongoing role to take German pressure off Nivelle’s climactic offensive further to the south.

General Robert Nivelle had enjoyed a meteoric rise since August 1914, beginning the war as a colonel in the artillery and achieving the command of a division in February 1915. Instrumental in the development of the creeping barrage, by December Nivelle had received promotion to corps commander. After distinguishing himself at Verdun, in May 1916 Nivelle took command of the Second Army and, by the end of the year, assumed command of all armies in northern and northeastern France. The French Government had placed its future in the hands of a ‘can do’ optimist who arguably had already been promoted beyond his ability. As all others around him, including even the notoriously optimistic Haig, were coming to terms with the weakness of the attack and beginning to understand World War I in terms of limited advances and attrition, Nivelle remained the last true proponent of decisive battle - the last worshipper at the altar of the cult of the offensive. Nivelle’s bold hope was to rupture the German lines within 48 hours and then destroy the German reserves in open battle. He wrote to his subordinates: ‘The objective is the destruction of the principle mass of the enemy’s forces on the Western Front. This can be attained only by a decisive battle, delivered against the reserves of the adversary and followed by intensive exploitation.’

‘Again the Canadians have “acquired merit.” In the capture of Vimy Ridge on April 9th ... they have shown the same high qualities in victorious advance as they displayed in early days in desperate resistance on many stricken fields.’

Canadian War Records Office, April 1917

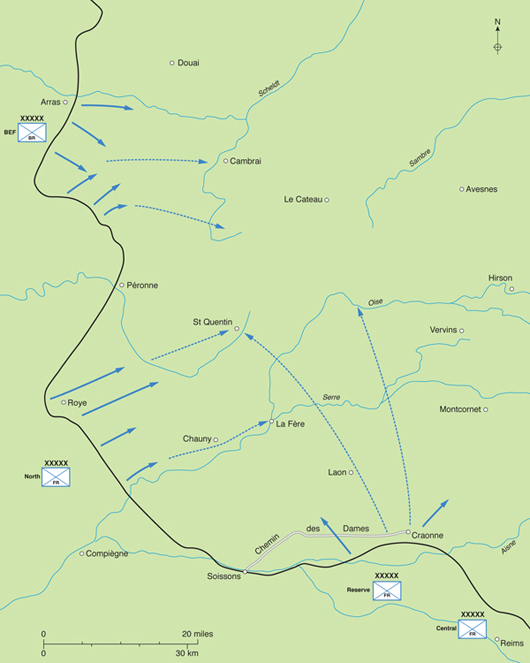

While the ground gained during the Nivelle Offensive actually compared favourablyto attacks ofprevious years, Nivelle’s scheme fell far short of its stated goals, leading to a crisis of confidence in the French military and the ability of the generals to win the war.

Nivelle’s final plan called for both the Central Army Group and the Northern Army Group to undertake supporting attacks, while the Reserve Army Group, under the command of General Alfred Micheler, carried out the main assault against the German defences on the Chemin des Dames. Micheler had the Sixth Army on his left and the Fifth Army on his right to make his assault, while the Tenth Army was held in close reserve to pass between the two attacking armies after they had broken through the German lines.

Although Nivelle remained convinced that the ‘violence, brutality and speed’ of the French attack would overcome any German defensive network, Micheler developed severe doubts about the wisdom of the planned offensive. In a letter to Nivelle, Micheler pointed out that the original plan had called for the Reserve Army Group to attack what had been comparatively weak German defences. However, the retreat to the Hindenburg Line meant that the Reserve Army Group would instead attack into the teeth of the most advanced defensive system on the Western Front, located atop the dominating high ground of the 183m-high (600ft) Chemin des Dames. Unknown to Micheler was the fact that the Germans were expecting the coming assault, and had moved 21 divisions into the front-line system, as well as holding a further 17 in reserve. Regardless of Micheler’s warning, Nivelle stood firm, confident that his artillery and the élan of the French military would prevail.

Along a front of nearly 40km (25 miles), the Reserve Army Group had massed a staggering total of 5350 artillery pieces, including 1650 heavy guns. Artillery preparation for the battle began in earnest on 9 April, and, by 5 May, the French artillery had fired 11 million rounds, two and a half million of which were heavy rounds. However, poor weather limited the effectiveness of the barrage, while German command of the air made it difficult to adjust fire, especially on the German positions located out of sight on the reverse slope of the Chemin des Dames. The situation was so bad that one artillery liaison officer with the front-line troops reported that the barrage had hardly damaged the German defences and warned that the infantry should expect to face ‘strong resistance’.

When the infantry advanced on 16 April, it faced largely intact German defences and murderous fire. The commander of II Colonial Corps, tasked with the seizure of the crest of the Chemin des Dames, described the assault of his unit against the German defence-in-depth system:

‘At H-hour, the troops approach in order the first enemy positions. The geographic crest [of the Chemin des Dames] is attained almost without losses. … Nevertheless, our infantry advances with a slower speed than is anticipated. The rolling barrage is unleashed and almost immediately and steadily moves ahead of the first waves, which it quickly ceases to protect. A few machine guns on the plateau do not halt the … infantrymen, who are able to descend the northern side of the plateau to the edge of the steep slope descending into the valley [on the reverse slope]. There, they were welcomed and fixed in place by the deadly fire of numerous machine guns that, located on the slope, outside the reach of our projectiles, have remained undamaged.

‘A few groups ... succeed in descending the slope. But in general, the troops suffered considerable losses in a few minutes, particularly in leaders, and not succeeding in crossing this deadly zone, halt, take cover, and at some points withdrew to the first trench to their rear.

‘The enemy’s reserves are in effect almost intact. Well protected in holes on the northern slope or in very strong dugouts, they have not suffered from the bombardment.’

The remaining forces of the Fifth and Sixth armies met with similar fates. On the right flank, Fifth Army achieved limited gains, and in some areas succeeded in entering the German second line of defences. Even where its attack had been most successful, though, Fifth Army ended the day short of the line that it was to have reached by 9.30am. On the left, the Sixth Army, including II Colonial Corps, initially made substantial gains, which, though they had heartened the attackers, were a function of the German defence-in-depth system designed to draw attackers forward only to subject them to counterattack by fresh German reserve formations.

An artist’s rendition of the French assault on the Chemin des Dames, a painting that juxtaposes the bravery of the French soldier with the seeming futility of the fighting in the Great War, a sense of futility that played a major role in the onset of the French Army mutiny.

Having failed to achieve a breakthrough, Nivelle hoped to salvage the deteriorating situation by ordering Fifth Army to attack more towards the northeast. However, as the offensive continued on 17 April, and French artillery cover became even less effective, the Fifth and Sixth armies made only extremely limited gains. During the night of 17 April, though, the Germans chose to withdraw from a vulnerable salient in their lines near Conde, which resulted in the left flank of Sixth Army moving forwards with great rapidity, covering nearly six kilometres (four miles) and capturing 5300 prisoners and vast stocks of munitions before regaining contact with the new German lines on 20 April. Meanwhile, though, the remainder of Sixth Army and the entirety of Fifth Army hardly moved forwards at all. In an attempt to restore forward momentum, and both to save his cherished offensive and his career, on 19 April Nivelle ordered the Tenth Army into the fray, to little avail.

By 20 April, it had become obvious to all that Nivelle’s effort to rupture the German lines and score a decisive victory had failed. Instructed by the French Government to avoid further losses, Nivelle lowered the sights of his offensive to a limited attack aimed only at the seizure of the remainder of the Chemin des Dames. Even with the change in strategic aim, the French Army as a whole had lost faith in Nivelle’s leadership. As subordinate commanders, including Micheler and Petain, raised objections to Nivelle’s plan to continue a limited assault on the defences of the Chemin des Dames, the French Government wrestled with how best to rid itself of Nivelle. After some confusion, on 29 April the politicians appointed General Henri Pétain as chief of staff of the French Army, and slowly eased Nivelle from power.

The Great War, with its bloody, static battles and grim landscape of corpses, resulted in an unprecedented number of psychiatric casualties among its combatants.

War, and its attendant killing, along with the constant risk of mutilation or violent death, often inflicts severe mental trauma upon the soldiers called upon to take part in the conflict. The scale of the industrialized slaughter of World War I, coupled with its static nature that often placed the living and dead in intimate proximity for months on end, ensured that mental casualties would be at an all-time high. Although cases of’ soldier’s heart’ were not unknown in the American Civil War, psychiatric battle casualties, known by the term ‘shell shock’, became much better known during the Great War, symptoms of which ranged from paralysis, through aimless wandering to loss of bladder and bowel control. Although many looked upon shell shock victims as deserters or cowards, the losses due to the phenomenon were so high, with the United States alone having 159,000 soldiers put out of action due to psychiatric problems, that every belligerent nation searched for both the cause of shell shock and its cure. Psychiatrists initially believed that the concussion of exploding shells compressed the brain, causing symptoms that closely mimicked those of genuine psychiatric cases. Only later in the war did most nations come to believe that the effects of battle in fact did have true psychiatric consequences. Even then, though, the prognosis for shell shock victims remained grim, with the Austrians even choosing to employ electric shock therapy as a possible cure.

The battlefields of WorldWar I were dominated by indirect artillery fire, and this ensured that observation and communication were key. The Germans wisely sited their defensive networks on the high ground, giving them a singular advantage over the Allies in many areas.

In late April and early May, French operations at the Chemin des Dames slowly drew to a close. In ground gained, the Nivelle Offensive compared favourably to those launched by Joffre, and actually had resulted in one of the greatest French forward movements to date in the conflict, in the wake of the German withdrawal from the Conde Salient. Additionally, French forces had captured 28,500 prisoners and 187 artillery pieces. However, the cost had been high, including 30,000 killed, 100,000 wounded and 4000 captured. Indeed the Nivelle Offensive might have been trumpeted as a great success earlier in the war; however, Nivelle had sealed his own doom by convincing the French soldiery of the imminence of climactic and cathartic victory. Morale in the military and the nation had soared on the expectation that the great trials and suffering of the war would soon be things of the past. What Nivelle had delivered instead of decisive victory, though, had been more of the same: more futility, more suffering, more losses, more Verduns. Although it had yet to become fully apparent, Nivelle’s failure to achieve victory caused French military and national morale to plummet to new lows, which very nearly cost France the war.

As Nivelle’s offensive floundered and the French Government struggled to decide whether to jettison its commander-in-chief, the diversionary British offensive at Arras continued. Although surprise was no longer possible, and operations at Arras had arguably passed the point at which any substantial gains beckoned, Haig had to continue the offensive as part of the overall Allied scheme to pin the German defenders in place and deny the enemy military resources for use against the French along the Chemin des Dames. On 14 April, Allenby issued orders for a renewal of the offensive by elements of the Third Army in two days’ time, but on the advice of many of his subordinates, Haig ordered a postponement to allow time to prepare for an attack on a larger scale. At the Somme, Haig had learned the price to be paid by mounting piecemeal, uncoordinated attacks and refused to make such a mistake at Arras.

The Lewis gun. Designed by Samuel Maclean, the weapon was of American origin and could fire 450-500 rounds per minute. Light and portable, the Lewis gun was adopted into widespread service in the BEF, and provided the infantry with renewed firepower.

Although the goals for the renewed assault at Arras were strictly limited, and both effective artillery fire and a number of tanks supported the assault, the attack that resulted on 23 April entailed some of the most difficult maneuvres of the war for the men of the BEF. Half of the British units involved in the attack had been engaged in earlier fighting at Arras and had not had adequate time to recover, while for their part the Germans had worked feverishly not only to rush fresh reserves and artillery to the scene but also to overhaul their defensive strategy. Sensing imminent danger, the German high command had sent defensive specialist Colonel Fritz von Lossberg to Arras, who altered the German defences there more closely to resemble the defence-in-depth scheme employed by the Hindenburg Line, which had brought the Nivelle Offensive to grief.

The results of the renewed offensive were mixed. Due in part to the nature of the German defensive scheme, units on the British right flank initially moved forwards well, only to face stern resistance in the battle zone, where several companies that had advanced more quickly than their brethren were cut off and surrounded. Although the fighting was bitter, VII Corps advanced over a kilometre and achieved most of its objectives, while VI Corps achieved similar gains.

On the British left flank, the experiences of XVII and XIII corps typified the ebb and flow of the difficult struggle. Backed by especially heavy artillery fire, the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division achieved one of the most notable successes of the day in its seizure of the heavily defended village of Gavrelle. However, the attackers had failed to seize some of the most important of their tactical goals, including the critical village of Roeux. After a pause in the fighting, British units moved forwards again on 28 April, but the failure of the attack, launched on a narrow frontage, was best illustrated by the experience of the 10th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. The barrage covering the advance of the Linconshires into Roeux was too weak, and resulted in what their official history termed, ‘the most disastrous action ever fought by the 10th Lincolnshires’. The claim was of considerable importance, considering that in 1916, the unit had been involved in some of the worst fighting on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, suffering 59 per cent casualties. In the attack on Roeux, though, the Lincolnshires lost a staggering 67 per cent casualties.

A British 9.2in howitzer. Much more powerful than field guns (the 9.2 could throw a 132kg (29lb) shell almost 10km (six miles)), howitzers were ideal for trench warfare. However, howitzers were very difficult to move forwards, which often resulted in attacks losing their momentum.

A German surrenders outside his defensive fortification during the latter stages of the Battle of Arras. Without surprise, and facing strong German defences, the British assault at Arras stagnated into bitter attritional fighting as the battle lingered.

As the fighting around Arras continued, the Allied strategic situation became increasingly and tragically muddled as it slowly became clear to Haig that Nivelle was falling from grace. In a private meeting with Nivelle on 24 April, Haig, who had always favoured an attack in Flanders, sought assurances that his attacks at Arras in adherence to the Allied strategic scheme were not misguided. Haig recorded in his diary:

Like soldiers in every war, the fighting men of World War I invented songs, some ribald and others touching, both to sing while on march and as a not so subtle form of protest.Many of the songs became quite well known, including a BEF standard, ‘Fred Karno’s Army’ (named after a popular comedian and sung to the tune of ‘The Church’s one Foundation’):

We are Fred Karno’s army,

The ragtime infantry,

We cannot fight, we cannot shoot,

What bloody use are we?

And when we get to Berlin,

The Kaiser he will say,

‘Hoch, hoch,Mein Gott,

What a bloody fine lot,

Are Fred Karno’s infantry.’

Other songs were more sombre, including ‘The Old BarbedWire’:

If you want to find the sergeant,

I know where he is, I know where he is,

If you want to find the sergeant,

I know where he is,

He’s lying on the canteen floor,

I’ve seen him, I’ve seen him,

Lying on the canteen floor.

If you want to find the sergeant-major,

I know where he is, I know where he is,

If you want to find the sergeant-major,

I know where he is,

He’s boozing up the privates’ rum,

I’ve seen him, I’ve seen him,

Boozing up the privates’ rum.

If you want to find the C.O.,

I know where he is, I know where he is,

If you want to find the C.O.,

I know where he is,

He’s down in the deep dug-outs,

I’ve seen him, I’ve seen him,

Down in the deep dug-outs.

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are, I know where they are,

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are,

They’re hanging on the old barbed wire,

I’ve seen ‘em, I’ve seen ‘em,

Hanging on the old barbed wire.

‘I requested him [Nivelle] to assure me that the French Armies would continue to operate energetically, because what I feared was that, after the British Army had exhausted itself in trying to make Nivelle’s plan a success, the French Government might stop the operations. I would then not be able to give effect to the other plan, viz. that of directly capturing the northern ports.’

With his mind already wandering to the potentialities of a British offensive in Flanders aimed at seizing the Belgian coast, and amid the uncertainty of the French command situation, Haig made his worst mistake of the battle. For several reasons, which included seizing tactically dominant ground near Arras, encouraging the French and maintaining a level of attrition on the Germans that could advantage future offensive operations, Haig decided to continue limited operations at Arras - even after the fighting in late April had demonstrated both that the Germans were ready and waiting and that hope for a meaningful victory in the area had long since passed.

On 3 May, the British advanced on a frontage of 22km (14 miles), in an attack that the British official historian of the battle referred to as, ‘a ghastly failure, some thought the blackest day of the war’. Although the attack was mercifully cancelled after only24 hours, it was followed by continuation of a subsidiary assault by the Fifth Army under General Gough aimed at the seizure of Bullecourt.

In their initial assault on Bullecourt on 3 May, V Corps and I ANZAC Corps achieved only limited gains into the German defensive network, which was part of the Hindenburg Line. Faced with the decision between abandoning the very vulnerable lodgements in the German lines, or pressing the attack to the seizure of the entirety of Bullecourt, Haig chose the latter, in part to keep German attention away from Flanders. The result was a bloody battle of two weeks’ duration, which succeeded in its dubious goals but greatly strained Anglo-Australian relations. The seesaw nature of the battle, involving brutal fighting concentrated on a very narrow frontage, resulted in a situation in which the dead of both sides covered the landscape, while the living clambered over and around the bodies to prosecute the battle. One witness remarked that in no other battle of the war were the living and the unburied dead in such close proximity for so long and that the nauseating stench made him wonder how ‘any human beings could hold and fight under these conditions’.

The fighting at Arras, which had cost both sides over 100,000 casualties, resulted in quite mixed results for Haig and the BEF. Careful planning, increasing professionalism in both the artillery and the infantry and tactical surprise had resulted in great gains on the first day of the offensive. Indeed, Haig’s army was much more tactically advanced than it had been 12 months previously at the Battle of the Somme. The BEF had proven that it could effect a break-in to even the most advanced German defensive systems; however, a breakthrough remained ever elusive. Although there were extenuating circumstances in the need to continue the fighting at Arras as part of the overall Nivelle scheme, Haig had once again demonstrated a propensity to continue offensives long after real hopes for substantial gains had passed, indicating that the BEF and its commander-in-chief still had much to learn. Even as the BEF began to codify and disseminate the tactical and strategic lessons of Arras, it soon became clear that the process was of the greatest urgency. In the wake of the failed Nivelle Offensive the French Army faced a crisis of morale, one that left the bulk of the fighting in 1917 to an improving but still flawed BEF.

British troops pass through a ruined French village on their way to the front lines during the Battle of Arras. While the first stage of the battle had been cause for optimism, a strategic gain had again eluded the BEF as the fighting degenerated into an attritional struggle.