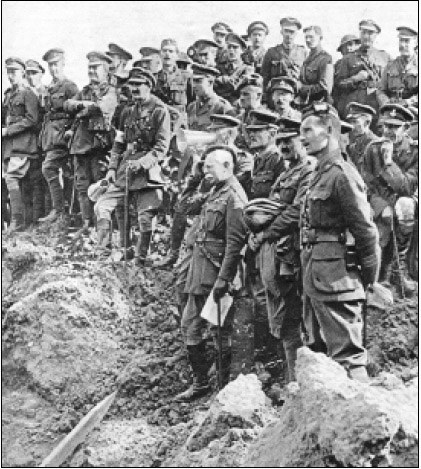

Troops from the 11th Leicester Regiment advance to the front. As mutiny stalked the exhausted French Army, more and more of the fighting on the Western Front would fall to the BEF.

In the wake of Nivelle’s failed offensive, the French Army dissolved into mutiny, threatening the Allied position on the Western Front. Against all odds, General Henri Philippe Petain rescued the French military from the brink. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig launched the first phase of his planned offensive in Flanders, a limited assault on the Messines Ridge.

The nearly three years of bitter struggle, much of which had taken place on its own soil and had devastated vast swathes of once productive countryside, had left France very nearly broken. Dashed hopes, futile offensives and the slaughter of Verdun, especially when combined with raucous governmental and Allied squabbles, had seriously compromised French civilian and military morale. Indeed, a growing sense of war weariness became noticeable within the French military even before the onset of offensive actions at the Chemin des Dames. While the erosion of morale had concerned Nivelle, he was certain that he knew its lamentable source. In a letter to the French Government before he unleashed his climactic offensive, Nivelle placed the blame for the decline in morale on civilian pacifist agitators:

‘I have the honour to inform you that I have reported the following pacifist intrigues to the Minister of the Interior. Faced with this grave threat to the morale of the troops, I am persuaded that serious measures must be taken. ... For more than a year, there have been pamphlets - pacifist brochures and papers - getting into the hands of the troops. Their distribution has now reached epidemic proportions. ... While on leave, a certain number of soldiers attend meetings where … the leading trade unionists and anarchists air their pacifist theories. When they return to the trenches, the soldiers repeat to their comrades the arguments they have heard.’

A French tank unit awaits orders. Serving what they believed to be an uncaring command structure, in the wake of the failure of the Nivelle Offensive, the morale of the French infantry began to crack and incidents of what became known as ‘collective indiscipline’ began to break out.

Nivelle went on to recommend that the ‘pacifist propaganda [should be] smashed’ and the laws more strictly enforced, which, he claimed, would put an end to the crisis.

Although the rather chaotic version of wartime democracy that characterized the French home front doubtless complicated the issue of military morale, Nivelle need not have looked beyond the policies of the French military to locate the problem’s true source. Having expected a quick victory in 1914, the military simply had not built up the kind of infrastructure required properly to look after many of the basic needs of its soldiery in a prolonged war. French soldiers received the lowest pay of any Allied force on the Western Front. Their food was often of poor quality and their rations meagre, but, more importantly to the average French poilu, their wine was often poor and in short supply.

Of greatest concern, though, was that home leave was almost unheard of; even British soldiers who had to cross the Channel to return home had more. Indeed, by the close of the Nivelle Offensive, many French soldiers had not received any home leave for 18 months, instead spending what little ‘rest’ time they had in squalid rear area camps. Even when a French soldier did receive precious leave time, he found that he had to fend for himself on his journey home, wasting valuable time waiting for trains and spending what little money he had on overpriced wayside accommodations and food.

While the upper echelon of the French command structure comfortably placed the blame for teetering morale on the actions of ‘trade unionists and anarchists’, evidence collected by the postal authorities, who censored letters home from the front, begged a different conclusion. In the weeks before the launching of the Nivelle Offensive the soldiers’ complaints in their letters home included: ‘bad food, lack of clothing, sustained fatigue, unskilled or indifferent leaders, [and] length of inaction’. After years of toil and bloodshed, many within the French military simply believed that their sacrifice was underappreciated and that they had been ill used by an uncaring military elite.

Although the French Army mutinies have become a part of the public historic consciousness of World War I, what is less known is the fragile state of French public morale during the trying months of 1917. Especially in Paris, many were worried that France was nearing a state of revolution. One Parisian wrote:

‘Everybody is complaining, in Paris and elsewhere. People are on strike over the price rises and over the lack of fuel, and this winter the poor will have nothing to use for heating. Can’t you just hear the rising strains of revolution! This winter, when the destitute are dying of cold or starving to death in their garrets because of the lack of foresight on the part of our ruling classes who do nothing to avert the danger, the mob will take to the streets, and will burn our furniture to keep warm, which will only be fair. But don’t think for a moment that the deputies in parliament are likely to sacrifice their salaries to come to the aid of the poor!’

The same postal authorities took note of the great surge in morale that accompanied Nivelle’s lavish claims of impending victory before the assault on the Chemin des Dames. As the failure of the offensive became clear, though, the censors catalogued a rapid decline in morale as the soldiers’ letters home described the attack in the following terms: ‘fiasco, lynching, botched, misfire, massacre, butchery, failure’. In the minds of many French soldiers, the bloody offensive transformed the nature of their military leadership from merely uncaring to criminal. Morale plummeted. Even what was arguably the best news of the month, the United States’ entry into the conflict, failed to give the soldiers hope. The postal authorities reported that, ‘Many think that the entry of America into the war, while giving us numerous advantages, will prolong the war at least a year and, by the relief of workers [who will be replaced by Americans], send thousands of Frenchmen to their deaths.’

The French Army slowly descended into a state of disarray in the wake of the Nivelle Offensive, and from late April through to May, there were 72 outbreaks of ‘collective indiscipline’. Although locally quite serious, at the outset the incidents were sporadic, lacked overall political goals and were devoid of organized leadership. Initially the indiscipline often took the form of small groups of soldiers simply shouting, ‘Down with the war!’ or, ‘We are through with the killing!’

The situation worsened with the 29 April report of the first true mutiny, the nature of which came to typify much of the coming national ordeal. The 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment had been in the forefront of Nivelle’s attack on 16 April and penetrated German lines to a depth of nearly 400m (437 yards) before being shattered on the German second line of defence. Scattered groups of the unit succeeded in making it back to French lines, where the next morning it became clear that only 200 survivors remained from the 600 men who had taken part in the assault. Only a few officers and non-commissioned officers remained to take the remnants of the unit to a rest area near Soissons. Although rumours abounded that the battalion would be disbanded, new drafts soon arrived to bring it back up to strength. The next step was to send the battalion off to a quiet area of the front for recuperation and training. Suddenly, though, the new officers of the unit ordered the men to pick up their gear and fall into formation. Only two weeks removed from its futile sacrifice, the rebuilt 2nd Battalion was going back into the front line to renew the attack on the Chemin des Dames. Shocked by the news the men refused the order, took over their encampment and quickly consumed the entire wine ration on hand. After midnight, a military police platoon confronted the now sober mutineers who belatedly and sullenly made their way toward the front. Five of the supposed ‘ringleaders’ of the incident were sentenced to death.

The Fusil Mitrailleur FM 1915 ‘Chauchat’ light machine gun. Weighing 9kg (20lb), and capable of firing 250 rounds perminute, the Chauchat was easy to manufacture, but was notoriously inaccurate and temperamental. Still, it remained in service throughout the GreatWar.

What began as an isolated incident soon spread like a disease through the demoralized French Army. The outbreaks of indiscipline were so spontaneous and disorganized that even the best among the French commanders were caught unaware. General Paul Maistre, in command of Sixth Army, reported to his superiors that XXI Corps was steadfast and could be entrusted with offensive operations. Barely two days later, though, he wrote, ‘The operation must be postponed ... We risk having the men refuse to leave the assault trenches. ... They are in a state of wretched morale.’

The mutinies, though, were especially virulent in rest camps where men had access to copious amounts of alcohol, and often flared when veteran units received orders to return to the front lines. On one such occasion in late May, ringleaders of the 370th Infantry Regiment of XXI Corps urged their brethren not to board their troop transports to the front. After a number of wine-sodden speeches, large numbers of soldiers made their way to the nearest railway station where they promptly stormed an available locomotive. Chanting slogans and firing rifles into the air, the 370th Infantry Regiment commandeered the train and departed for Paris, bent on overthrowing the government and ending the war. The mutineers, though, had to halt the train near Villers-Cotterets, because a loyal cavalry unit had blocked the tracks with fallen trees. Now sober, most of the mutineers surrendered peacefully, while those who resisted were shot on the spot. From late May, railways became a focus of mutinous activity as several units sought to make their way to Paris, while others simply took over trains to get home and see their families.

A French firing squad in action. Faced with military indiscipline on a grand scale, the French, under the leadership of General Henri Philippe Pétain, sentenced 554 mutineers to death, only 55 of whom actually were executed. Many others served long prison sentences.

Minister of War Paul Painlevé had occasion to visit troops at a rest camp near Prouilly and described the topics of the harangues of mutinous leaders:

‘Some spoke of the exhaustion of the troops; others, of the scandalous privileges of the embusqués [shirkers] in the rear echelons; still others, of the incapacity of the staffs, who accepted honours and privileges but failed to give the troops the victory which each day had been promised them; and, finally, other orators spoke of the news from Russia [where troops were nearing a state of rebellion] and pointed to the Russian soldiers as an example.’

Even though the futile Nivelle Offensive, assumed to be the immediate cause of the problem, had drawn to a close, the mutinies actually, for a number of reasons, worsened and reached their most dangerous stage during the first week of June. Although the attack on the Chemin des Dames had ceased, the underlying factors of poor pay, squalid conditions and inadequate leave remained. Most frightening, though, was the fact that the mutinies intellectually had begun to coalesce. As in Russia, mutineers began to form soldiers’ councils that identified closely with far left political parties that stood in opposition to the continuation of the war.

Perhaps the most disturbing incident among the new wave of mutinies involved the 298th Infantry Regiment, the men of which, in what had become almost standard fashion, had informed their commanding officers that they would not return to the front lines. When the officers rejected their demands the soldiers rose up and captured the town of Missy-aux-Bois. Electing their own new officers, the mutineers established a revolutionary government for the village and set up defensive lines to resist attacks from loyal troops. Soon a cavalry unit arrived and cut off the small town and successfully starved the mutineers into submission. Even then, though, the men of the 298th maintained ‘revolutionary discipline’ and paraded out of the town to offer a formal surrender.

An engraving by Leon Ruffe, entitled ‘The Rumbling Discontent’, portrays the results of the harsh life of trench warfare and the Nivelle Offensive on the long-suffering French infantryman. This lack of concern for the well-being of the French poilu was to have serious results.

The more organized qualities of the mutinies, along with their more ambitious revolutionary goals, greatly worried both the French military and political leadership. In a letter to a member of the French parliament, General Franchet d’Esperey gave voice to the fears of many:

‘There exists an organized plot to dissolve discipline. ... The ringleaders among the troops are in contact with suspicious elements in Paris. They scheme to seize a railway station so that they may transport themselves to Paris and raise the populace in insurrection against the war. The Russian Revolution has served as their model. … The troops are in a continual state of excitation kept up by the newspapers, which are filled with details of the events in Russia, by parliamentary criticism of the generals and by the exaggeration of pessimists. ... Why do you close your eyes to this? ... Unless it is stopped we will have no Army and the Germans can be in Paris in five days!’

It was one of the pivotal moments of the conflict on the Western Front, for the valiant French military appeared to be disintegrating. Mutinies of varying severity had affected up to 50 divisions, and as many as 30,000 soldiers had deserted. French commanders and politicians, understandably keeping the information of the growing indiscipline to themselves and away from enemy and ally alike, despaired that in its present condition the French Army could not even defend against a German attack, much less persevere to victory in a long war. Even more frightening was the seemingly very real possibility that France could succumb to the same type of revolution that had engulfed Russia. Desperate measures were required to avoid defeat and to avoid revolution; France needed a hero.

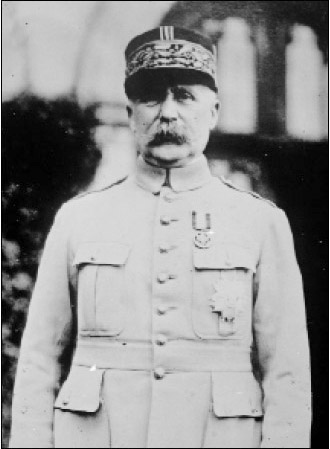

To some, including Sir Douglas Haig, the May 1917 shift to Petain as commander of the French armies, while General Ferdinand Foch became Chief of the General Staff, had seemed to be a dangerous gamble. White haired and aged 61, Petain had only three years earlier been but an obscure colonel. He had risen to fame at Verdun, but had since been branded as a pessimist. Having reached the pinnacle of his military career amid the aftermath of Nivelle’s failed offensive, Petain took stock of the situation only to find a French Army that was in ruins. ‘They call me only in catastrophes,’ he later remarked. One of his subordinates recorded the grim nature of Petain’s first few days in command:

Margaretha Zelle, dressed in one of the elaborate and seductive costumes that helped her to gain fame as Mata Hari.

Mata Hari was the stage name for the Dutch exotic dancer and courtesan Margaretha Zelle. Born in 1876 in the Netherlands, Zelle eventually gained fame as a flirtatious dancer, as well as for her scanty and extravagant costumes. Since the Netherlands remained neutral in World War I, Zelle was able to pass European borders freely and continue her career, wooing both Allied and German officers and businessmen alike. In her unique position, Zelle almost certainly worked as a double agent, uncovering and selling secrets for both the Allies and the Central Powers. In the charged wartime atmosphere, the actions of Mata Hari could not have gone unnoticed. In January 1917, French intelligence intercepted a German message, which lauded the efforts of a spy code-named H-21, and was able to deduce that the spy in question was in fact Mata Hari. Oddly, the code used to transmit the information about H-21 was one that the Germans knew to be compromised, which has led some historians to conjecture that the Germans wanted Mata Hari to be caught, because she was in fact working for the Allies. Regardless, on 13 February 1917, French authorities arrested Mata Hari, accusing her of treason. Although there was precious little evidence against her, with French morale at a critically low level, Mata Hari was convicted and sentenced to death, and on 15 October 1917 she was executed by firing squad.

‘I do not know a more horrible sensation for a commander than to suddenly learn that his army is breaking up. I saw the initial disaster at Verdun and the day following [the Italian defeat at] Caporetto, but on these occasions I always sensed that with some reserves and a little imagination it would be possible to caulk up the front. But there had never been anything like May 20! We seemed absolutely powerless. From every section of the front the news arrived of regiments refusing to man the trenches. ... The slightest German attack would have sufficed to tumble down our house of cards and bring the enemy to Paris.’

Pétain set about the urgent project of rebuilding French military morale with both boundless energy and great urgency. Unlike so many of his predecessors, Pétain did not simply blame the mutinies on outside agitators or on cowardice; instead he recognized that many of the soldiers’ basic complaints were valid. He worked feverishly to improve conditions at rest camps and to make certain that all soldiers enjoyed a uniform and high level of training. He also announced a pay raise and ordered the provision of fresh fruit and vegetables for field kitchens close to the front lines. Most importantly, though, he issued more liberal policies regarding leave, allowing every soldier to take 10 days of leave every four months, and made certain that soldiers were well cared for during their leave.

Having risen to fame during the Battle of Verdun, General Henri Pétain took over command of the French Army on the Western Front at its nadir in the wake of Nivelle’s offensive. Tasked both with rebuilding the army and winning the war, Pétain quipped, ‘They call me only in catastrophes.’

Pétain also sought to cement a closer bond between the officers of the French Army and their men, and he directed that the officers undertake weekly meetings with those under their command, contending that, ‘by explaining, one achieves understanding and arrives quickly at a community of ideas, the basis of cohesion’. Practising what he preached, Pétain visited and spoke to the men of 90 divisions. During his visits he spoke of the overall strategic situation and contended that American entry into the conflict had made victory inevitable. Besides utilizing his enormous credibility with the common soldier to rebuild morale by eating and speaking with them, Pétain published a series of articles entitled ‘Why We Are Fighting’, which attempted to reconnect the soldiers to the sacrifices of the past. One pamphlet read:

‘We fight because we have been attacked by Germany.

We fight to drive the enemy from our soil...

We fight with tenacity and discipline, because these are essential to obtain victory.’

French soldiers (here pictured disembarking for the front) received little home leave, and the lowest pay of any Allied force, contributing factors to the mutiny that Pétain worked to ameliorate. When many of these basic complaints began to be addressed, morale started to rise.

Pétain once again treated the French poilu with dignity and respect, and the results were nearly instantaneous. However, the new commander also leavened his kindness with firm discipline. Armies cannot stand for mutiny, and there had to be retribution. Pétain first warned his officers not to tolerate further disruptions of discipline and empowered them to take firm control of the matter by issuing the following order on 5 June:

‘At the time of some recent incidents, officers have not always seemed to do their duty. Certain officers have concealed from their superiors the signs of adverse spirit which existed in their regiments. Others have not, in their repression, displayed the desired initiative or energy. ... Inertia is equivalent to complicity. The Commander in Chief has decided to take all necessary action against these weaklings. The Commander in Chief will protect with his authority all those who display vigour and energy in suppression.’

In the end the French Army convicted 3427 soldiers of offences during the mutinies and sentenced 554 to death, only 55 of whom actually were executed, with the remainder serving long prison sentences. Considering the widespread nature of the mutinies, the retribution was slight. Pétain realized that, since many of the grievances of the French soldiers were genuine, if discipline were too harsh, morale might suffer further decline and the mutinies continue. Explaining his motives Pétain remarked in June, ‘I have pressed hard for the repression of these grave acts of indiscipline; I will maintain this pressure with firmness but without forgetting that it is applied to soldiers who, for three years, have been with us in the trenches and are “our soldiers”.’

Of the greatest importance to the rebuilding of French military morale, though, was Pétain’s eschewing of vain efforts at achieving decisive victory in favour of attacks aimed only at limited and achievable objectives. Pétain quicklymade it clear that under his leadership no longer would French soldiers throw their lives away for the vain hopes of floundering commanders. Indicative of his philosophy of war, one of Petain’s first strategic memorandums read in part:

German ‘walking wounded’ and stretcher cases. In World War I, as in most other conflicts, the number of military wounded (over 20 million) outnumbered the more infamous number of military deaths (estimated at nearly 10 million).

‘The equality of the opposing forces does not for a moment permit us to envisage the rupture of the front. ... [It does not make sense] to mount great attacks in depth on distant objectives, spreading our initial artillery preparations over [enemy] defences, resulting in bombardment so diluted that only insignificant results are obtained. ...[Future attacks will be mounted] economically with infantry and with a maximum of artillery.’

The prospect of limited offensives in which lives were not going to be wasted eventually proved a tonic to the morale of the French Army. However, in June 1917, even Pétain remained unsure of whether the French Army could hold against a concerted German offensive aimed at Paris, for he needed time to rebuild his shattered forces and for his reforms to take effect. The results of the mutiny, thus, in the short term altered the strategic balance of the war and required Petain to advocate continued British action on the Western Front to thwart any potential German efforts to assail the wounded French Army. In the long term, the results of the French Army mutinies foretold a scenario in which more and more of the fighting would fall both to the BEF and later to the Americans.

The industrialized slaughter of World War I produced not only record numbers of dead but also of wounded, often men with horrific wounds, who, due to advancements in medicine, were kept alive but often had only no real chance of ever again leading a normal life. With reconstructive surgery in its infancy, the worst such cases involved head wounds. An orderly at a London hospital recalled:

‘To talk to a lad who, six months ago, was probably a wholesome and pleasing specimen of English youth, and is now a gargoyle, and a broken gargoyle at that... is something of an ordeal. You know very well that he has examined himself in a mirror. That one eye of his has contemplated the mangled mess that is his face. ... He has seen himself without a nose. Skilled skin grafting has reconstructed something which owns two small orifices that are his nostrils; but the something is emphatically not a nose. He is aware of just what he looks like: therefore you feel intensely that he is aware that you are aware, and that some unguarded glance of yours might cause him hurt. ... Suppose he is married or engaged to be married... could any woman come near that gargoyle without repugnance? His children. ... Why a child would run screaming from such a sight. To be fled from by children. That must be a heavy cross for some souls to bear.’

While his own offensive around Arras wound down, and it became increasingly obvious that French failures at the Chemin des Dames spelled the doom of the Nivelle’s plan to achieve decisive victory, Haig’s thoughts turned to the possibility of major operations in Flanders. For a variety of reasons the British commander-in-chief had long favoured an attack from the salient around Ypres. The Germans held the high ground around the constricted Ypres Salient, making the area one of the most deadly on the Western Front for the BEF. Relatively modest gains would push the Germans off the ridges and make the British salient much safer and more defensible. Greater gains would threaten the vital German communications hub of Roulers, some 40km (25 miles) east of Ypres, the capture of which would threaten German logistics in the area and possibly force a German evacuation of the coast to Ostend. Such gains would be of the utmost strategic importance to Britain, for in the midst of a submarine war that was going increasingly badly, the Admiralty agonized over the naval threat that emanated from the German bases in occupied Belgium. Indeed, a forward movement in Flanders seemed of more strategic value than anywhere else on the Western Front. In a letter to Nivelle shortly before his fall, Haig made his desires clear:

“[T]he state of the French army is now very good, but at the end of May there were 30,000 “rebels” who had to be dealt with. .. .This shows how really bad the condition of the French army was after Nivelle’s failure.”

Diary of Field Marshal Haig

‘I feel sure you realize the great importance to all of the Allies of making a great effort to clear the Belgian coast this summer. The enemy’s submarine operations have become such a serious menace to the sea communications, on which all the Allies are so dependent for many of their requirements, that the need to deprive the enemy of the use of the Belgian ports is of the highest importance and demands a concentration of effort.’

That Haig wrote initially to Nivelle demonstrates that the British knew little regarding the seismic shift in the French command system. Although they received disturbing snippets of intelligence, the British knew even less regarding the perilous state of the French military. Once it had become clear that Petain, not Nivelle, controlled French strategy, though, the situation quickly sorted itself out, for Haig and Petain had similar goals, though both guarded their counsel and refused to be entirely honest with each other. For his part Haig strongly desired to launch an attack in Flanders, but realized that he would need French cooperation in the attack, lest Lloyd George veto the operation for fear that it could become another Somme. Petain, on the other hand, had to walk a strategic tightrope. Although he never fully believed in Haig’s plan, he desperately required a British offensive to ensure that the Germans would not attack the vulnerable French Army. Petain knew that the state of French morale was so perilous that he could offer but little aid to any British offensive in Flanders, but he had to promise enough aid to make certain that Haig received the approval of the British Government for his Flanders plan. Such is the nature of imperfect alliances.

The British sector of the Western Front in 1917 was dominated by German positions on the high ground near Messines and to the east of Ypres, overlooking the salient. It was this patch of high ground in Flanders that was to be the target of the British Second Army, under General Sir Herbert Plumer, during the Battle of Messines.

Having undertaken preliminary planning for operations in Flanders in 1916, Haig already had a general outline of offensive there in mind even before the Nivelle Offensive and the fighting at Arras had ended. In May Haig had informed his army commanders of his intention to shift the bulk of BEF offensive operations to Flanders, but to facilitate his goal, Haig’s plan called for several wearing-down attacks, including continued action at Arras. An assault on the Messines Ridge, which dominated the area around Ypres, would follow on 7 June 1917. After the completion of the Messines operation, the main assault would take place in the neighbourhood of Ypres.

Even at this early stage, Haig’s strategic scheme seemed at cross-purposes and contained inconsistencies that conspired to doom his cherished Flanders offensive to seeming futility. Haig had learned much from the first years of World War I. Fighting at Arras and the latter stages of the Somme had indicated both that the BEF was proficient at setpiece battles aimed at limited gains and that offensive operations achieved diminishing returns over time. However, Haig firmly believed that the German Army had a breaking point, and overly optimistic information provided by BEF intelligence chief, Brigadier-General John Charteris, indicated that the German breaking point was in fact drawing near. The lessons of past offensives, coupled with the hope of a collapse of German morale, left Haig in a quandary. Should the coming offensive in Flanders be limited in nature, or should it aim to achieve something more decisive? Fatally, perhaps, Haig chose both.

Australian troops grab what rest they can, while their machine guns remain at the ready. It was the machine gun, with its lethal rapid fire, that came to epitomize the Great War. It was, however, artillery fire that caused the majority of the casualties.

In a 16 May memorandum to Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir William Robertson, Haig made it clear that he planned for operations in Flanders to take the form of limited, set-piece battles similar in nature to the first phase of operations at Arras:

‘I have already decided to divide my operations for the clearance of the Belgian coast into two phases, the first of which will aim only at capturing certain dominating positions in my immediate front, possession of which will be of considerable value subsequently, whether for offensive or defensive purposes.

‘Preparations for the execution of this first phase [an attack on the Messines Ridge] are well advanced and the action intended is of a definite and limited nature, in which a decision will be obtained a few days after the commencement of the attack.

‘A second phase is intended to take place several weeks later, and will not be carried out unless the situation is sufficiently favourable when the time for it comes.

‘It will be seen, therefore, that my arrangements commit me to no undue risks, and can be modified to meet any developments in the situation.’

Haig also made it quite clear to his army commanders, though, that he hoped that the hammer blows by the BEF, while limited in nature, would result in a collapse of the German lines, and result in the ‘possession of the Belgian coast up to the Dutch frontier, or, failing this, to dominate the Belgian ports now in the hands of the enemy to an extent that will make them useless to him for naval purposes’. Haig’s scheme, then, had a fatal flaw: although the attacks themselves were to be limited in nature, they would take on a life of their own, continuing in the vain hope that the next limited victory would cause German resilience to falter.

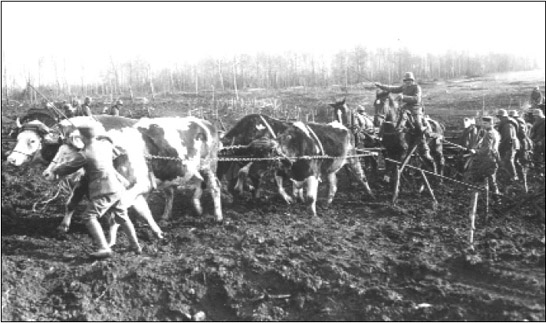

Although the nation fought on, by 1917, stricken by constant war and the effects of the British blockade, Germany was suffering from shortages of all types, including shortages of horses, as indicated by this photo of German artillery being led by cattle.

While planning progressed, Haig received word that Lloyd George would not approve the Flanders offensive unless the French agreed to launch major supporting operations. The news was distressing to Haig, who had just received word from his trusted confidant in Paris, Lord Esher, that the French under Petain ‘have agreed upon a so-called military policy, the basis of which is (however it may be wrapped up in jam), to wait for the Americans’. Both to divine the intentions of the French, and to ensure the support of his own government for his planning, on 18 May Haig met with Pétain at a conference in Amiens.

Although he feared that Haig’s plan was overly optimistic and reminiscent of the Somme, Pétain wanted Haig to undertake an offensive, partly to reduce pressure on the demoralized French Army. However, Pétain could not tell Haig about the mutiny, for the French commander-in-chief knew that approval of the British offensive depended on French aid and that any sign of French weakness could only delay Haig’s operation or result in its cancellation.

At the conference, then, Pétain assured Haig that he would ‘fight and support the British in every possible way’. Although the goals of his operations would be strictly limited, Pétain agreed to undertake four attacks in the areas around the Chemin des Dames and Verdun to take pressure off British operations in Flanders. Pétain also promised that French forces would operate on the left flank of the main British attack around Ypres. Petain’s statements of support impressed Haig, who now had the assurances he needed to calm Governmental fears over his Flanders campaign. For his part, Pétain knew full well that he had made promises to Haig that he would have difficulty keeping, but he did so in the best interests of France. Haig had needed assurances of French support before he could attack, and that is exactly what Pétain gave him.

General Sir Herbert Plumer (centre). One of Britain’s most able generals during World War I, Plumer was an advocate of bite-and-hold, limited offensives, leading the BEF to notable successes at Messines and during the second phase of the Third Battle of Ypres.

Soon after, however, reports of the French Army mutinies began to trickle in to Haig’s headquarters, which severely damaged the value of Pétain’s promises. On 25 May Charteris first noted the existence of indiscipline in the French ranks, and bemoaned the fact that the French had decided to grant each man 10 days’ leave every four months, which meant that a quarter of a million French troops would be out of the front lines at any one time. Charteris passed the distressing intelligence on to Haig with the note, ‘that we cannot expect any great help from the French this year’.

News concerning the French Army mutinies became so widespread that Pétain could no longer keep the truth of the situation from his British allies. On 2 June, only eight days before the first French attack scheduled in support of Haig’s Flanders offensive, Pétain admitted to Haig that a state of indiscipline existed in certain parts of the French Army, which precluded any French attacks until at least July. Pétain then went on to request that the BEF proceed with offensive actions, to keep German pressure off the reeling French military. Pétain’s entreaties had the desired effect on Haig, who later that day told Winston Churchill of his belief that Britain needed to launch a powerful blow against the German lines because he doubted ‘whether our French allies would quietly wait and suffer for another year’.

British troops moving forward carrying supplies in ‘Yukon packs’. Allowing the wearer to carry 23-27kg (50-60lb) of supplies comfortably over rough territory, Yukon packs were critical to Plumer’s plan to keep his forward lines well supplied during the Battle of Messines.

The news that the French would be unable to offer meaningful military support to the Flanders offensive threatened to derail Lloyd George’s reluctant approval of Haig’s planning. At the same time, though, General Sir Henry Wilson, who served as the British liaison officer with Pétain and was trusted by Lloyd George, began to piece together the severity of the situation in the French military, recording in his diary the belief that, ‘it will be impossible to keep the French in the war for another 12 or 18 months waiting for America without a victory of some sort’. On the advice of Wilson, and more to safeguard the beleaguered French military than out of faith in the judgment and planning of Haig, Lloyd George gave his grudging approval only to the first phase of the Flanders offensive, a strictly limited assault on the Messines Ridge.

A German observation post. Usually enjoying positions on the high ground, the Germans were often able to oversee Allied lines. The advantage enabled the Germans accurately to predict several Allied offensives.

Atop a spine of high ground, the German positions at Messines Ridge dominated the southern flank of the Ypres Salient. Haig realized that the capture of the ridge was an essential precursor to launching the main operation from Ypres, and entrusted the important operation to General Sir Herbert Plumer in command of Second Army. Plumer enjoyed a unique familiarity with the area, the Second Army having been stationed there for more than two years. With ample time to prepare his offensive, Plumer planned a very limited advance, along the lines of what the Canadians had achieved at Vimy Ridge, under the cover of a massive artillery barrage. Enjoying a close relationship with his men, based on ‘trust, training and thoroughness’, Plumer left little to doubt amid a meticulous build-up to battle. A hint at the level of preparedness of Second Army lies in the fact that water pipes had been laid that could deliver up to 2,271,247 litres (600,000 gallons) per day, while light railways enabled the stockpiling of 130,634 tonnes (144,000 tons) of ammunition for the army’s guns. In addition, each unit scheduled to take part in the offensive practised every movement that it was to undertake on the day of the attack on a large model of the ridge constructed behind British lines. Nothing had been left to chance.

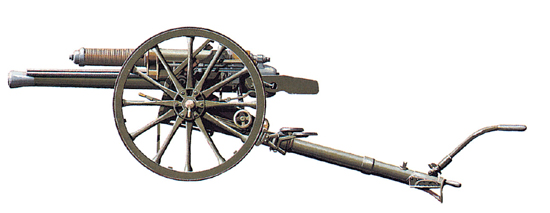

A British 18-pounder field gun. Serving as the main British field gun for the duration of the war, the 18-pounder was mobile, but packed a comparatively small punch. The guns were often used to cut enemy barbed wire and to move forward rapidly to cover any gains made in battle.

Plumer had also hatched an ingenious scheme designed to blow the German defences of the Messines Ridge sky high. For nearly two years Second Army had been involved in the digging of 24 long tunnels beneath the German lines, tunnels that ranged from 183 to 1830m (200 to 2000 yards) in length, and were packed with an average of 21,772kg (48,000lb, 24 tons) of ammonal, a particularly lethal high explosive. The largest single explosive charge was the 43,363kg (95,600lb) of ammonal put in place by the Canadian Tunneling Company at the end of a 503m (1650ft) tunnel, 38m (125ft) beneath St Eloi.

Not only did miners in the Great War endure back-breaking labour but also they were often faced with fighting a brutal underground war with enemy miners.

Both the Germans and the Allies recruited for work on the Western Front professional miners, who had the backbreaking and dangerous task of fashioning tunnels beneath enemy defensive emplacements. Labouring in 12-hour stretches, the miners utilized only picks and light shovels and excavated their tunnels by hand, passing the soil in bags or buckets to the man behind them in line. Although under constant threat from collapsing tunnels and poison gas, the greatest fear for the miners was discovery by enemy forces while underground. Constantly on the lookout, defenders dug countermines, and employed listening equipment, ranging from sensitive microphones to simply pressing an ear to an overturned bucket, to discern the location and direction of enemy miners. Once an attacking mine was located, the defenders tunnelled as close as possible to the attacking force and then set off a small charge, called a camouflet, designed to collapse the enemy tunnel and entomb the attacking miners deep underground. On some occasions, though, the defenders got too close and the mines converged, resulting in close-quarter underground fighting with picks and spades. The victors would take possession of the mine, while the losers had literally dug their own graves.

Even as the final touches were put on the mines, on 26 May the preliminary barrage began in earnest, as a total of 2266 guns, including 756 heavy guns organized into 40 bombardment and counterbattery groups, opened fire on German lines. The preparatory bombardment was methodical, involving a sophisticated fire plan like that used at Arras. Air reconnaissance had located many of the German gun emplacements, which allowed the counterbattery teams to harass the German gunners with both high explosive and gas, which kept German artillery fire during Second Army’s advance to a minimum. A German machine-gunner remembered the effectiveness of the British barrage:

This is far worse than the Battle of Arras. Our artillery is left sitting and is scarcely able to fire a round … the sole object of every arm that enters the battle is to play it self out, in order to be withdrawn as quickly as possible.

By 7 June, as Plumer’s men made ready to go ‘over the top’, the British artillery had fired over three and a half million shells into the German lines at Messines.

The Germans had long realized that their positions on Messines Ridge were vulnerable to mining, and that any British assault in Flanders would have the ridge as its main focus. General Hermann von Kuhl, chief of staff to Crown Prince Rupprecht, suggested that it would be better to evacuate the Messines Ridge and withdraw five kilometres (three miles) to more defensible positions. Local commanders, led by General von Laffert in command of XIX Corps, however, overruled Kuhl’s suggestion, contending that the positions on the Messines Ridge were fully up to date and comprised a defence-in-depth scheme that would withstand any British attack.

At 3.10am on 7 June the mines beneath the Messines Ridge detonated. Norman Gladden, a young infantryman with the 23rd Division, remembered:

‘With a sharp report a rocket began to mount into the daylit sky. A voice behind me cried, ‘Now’. It was the hour, and that enemy light never burst upon the day. The ground began to rock. My body was carried up and down as though by the waves of the sea. In front the earth opened and a large black mass mounted on pillars of fire to the sky, where it seemed to remain suspended for some seconds while the awful red glow lit up the surroundingdesolation. No sound came. Mynerves had been so keyed to sustain a noise from the mine so tremendous as to be unbearable. For a briefspell all was silent, as though we were so close that the sound itself had leapt over us like some immense wave. Almost simultaneously a line ofmen rose from the ground a short distance in front and advanced away towards the upheaval, their helmets silhouetted and bayonets glinting in the unearthly redness.’

British troops take what rest they can while holding a strong natural defensive position against the Germans. Amid the nearly continuous shellfire of battle, soldiers on both sides quickly mastered the ability to rest where and when they could.

A Belgian priest who witnessed the explosions from some miles away recorded, ‘I suddenly witnessed the most gigantic and at the same time chillingly wonderful firework that ever has been lit in Flanders, a true volcano, as if the whole southeast was spewing fire.’

At the Battle of Messines, Plumer’s forces seized nearly all of their objectives, helped by the explosion of a series of huge mines, with only few losses, demonstrating the practicality of limited offensives in the Great War.

On the day before the battle, Plumer’s chief of staff, General Tim Harrington, had remarked, ‘I do not know whether we shall change history tomorrow, but we shall certainly alter the geography.’ His words were prophetic. The series of explosions ripped the top off much of the Messines Ridge, destroying the German front-line trenches and killing as many as 10,000. The force of the explosions was so great that it was felt in London, 208km (130 miles) away. The craters left by the mines were on average 69m (76 yards) wide and 24m (26 yards) deep, large enough to hold a five-storey building. Although the mines had been a marvellous success, for tactical reasons three had not been detonated. Somehow forgotten for years, one of the massive mines exploded during a thunderstorm in 1955, while two remain armed and ready to fire beneath the Messines Ridge to this very day.

In the wake of the devastating blasts, 80,000 British and Australian infantrymen of nine divisions moved forward to undertake their carefully rehearsed tasks under the cover of a smokescreen, a covering artillery barrage and a creeping barrage of machine-gun bullets. Utilizing grenades, light machine guns and the support of 72 tanks, the advancing forces flanked and destroyed the ubiquitous concrete pillboxes that made up the German forward line of defence and seized their first objectives within 35 minutes. Next the attackers entered the battle zone, where German reserve formations and their counterattacks had brought so many previous offensives, including that of Nivelle at the Chemin des Dames, to grief. However, the effects of the mines and the accurate covering barrage kept German resistance to a minimum, and by 7am II ANZAC Corps had seized the village of Messines, and all along the front the attackers had gained the crest of the ridge and overthrown the German second line of defence. The advance then halted under the cover of an additional protective barrage, to bring up reserve formations and prepare for additional expected German counterattacks. None, though, were forthcoming. In the words of the British official history:

German reinforcements move toward the front lines. At Messines, as they had at Vimy Ridge, the Germans held their reserves too far to the rear to have a meaningful effect on the initial outcome of the battle.

‘The German garrison had been defeated in detail. The front battalions had been overrun in the first rush, and few had escaped. Their support battalions [in the battle zone] had then been overwhelmed before the reserve battalions could reach them in any strength. Elements of the reserve battalions had come through and shared the fate of the support battalions; but the majority had remained lying out in shell-holes on the eastern slope of the ridge awaiting events.’

As they had at Vimy Ridge, the German had held their reserve divisions too far back to make an immediate effect on the fighting and in the words of one Australian officer, the next few hours were ‘more like a picnic than a battle’. Behind the advance was only desolation, innumerable small shell holes created by the barrage and the gaping craters that were the only memory of the mines. To the front was only green grass and trees of the reverse slope of Messines Ridge. The few German reserves that were available were gathering out of sight, feverishly moving vulnerable artillery pieces and constructing new lines of defence to contain the imminent British breakthrough rather than attempting a futile counterattack.

In the early afternoon, reserve forces passed through the British front-line troops and pushed toward the Oosttaverne Line of rearward German defences. On this occasion, though, Plumer had been if anything too methodical. The pause atop the Messines Ridge not only enabled the Second Army both to gather its reserves and to prepare the critical next phase of the artillery barrage, but also allowed the Germans to reinforce and dig in behind the Oosttaverne Line. Even so, the renewed advance, beginning at 3.10pm made substantial gains, even seizing the first trench of the Oosttaverne Line, and capturing 48 German artillery pieces.

As German resistance predictably began to stiffen while reserves rushed to the scene from other portions of the Western Front, Plumer brought his offensive to a halt. It was a stirring victory. After months of intense planning, the Second Army had overthrown one of the most powerful German defensive positions on the Western Front and seized the entire Messines Ridge at a cost of only 24,562 casualties. Revealingly the German casualties during the battle numbered 25,000, including 10,000 missing. It was the first time on the Western Front since the advent of trench warfare that attacking forces had so evened the odds that battlefield losses were roughly equal.

As the weight of the Allied war effort shifted towards the British in the wake of the French Army mutinies, Plumer’s successful assault on the Messines Ridge boded well for the future. As it had at Arras, the BEF had again proven adept at utilizing overwhelming firepower to achieve limited objectives even against the strongest German defences. After the conclusion of the battle, Plumer informed Haig that he would need three days to reorganize his forces to face a more northerly direction before undertaking a second limited offensive aimed at the seizure of the Gheluvelt Plateau, which would herald the main British advance from Ypres. For good reasons, though, Haig demurred; he wanted a longer period of preparation for the coming assault, something that had been so important to Plumer’s own victory, and critical Governmental support for operations in Flanders unexpectedly began to waver. Although Haig’s decision was both required by political realities and was in many ways tactically sound, it was one of his most fateful of the entire war, an unheralded moment of change that would almost undo Haig’s career. Given time for rumination, instead of relying on the methodical and successful Plumer to continue the assault around Ypres, the ever-optimistic Haig turned to another commander who he hoped would be more aggressive if the limited attacks in Flanders indeed offered the chance of a greater success.

‘When the crash came the bravest trembled. The very ground seemed to be opening at their feet. Hills were thrown into the air; trees blown sky-high; guns and men and concrete all buried together.’

Max Pemberton, The War Illustrated, 23 June 1917

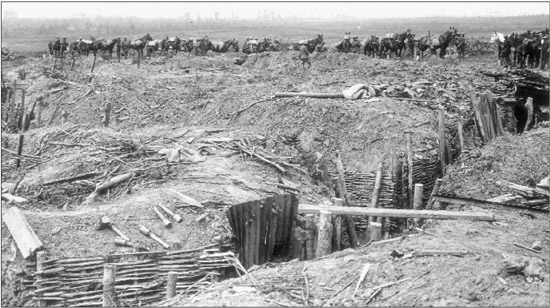

The desolation of war: a supply train passes an abandoned German trench, which, though pockmarked and battered, withstood the worst of the British artillery fire. Note the stick grenades left on the parapet, ready for use.