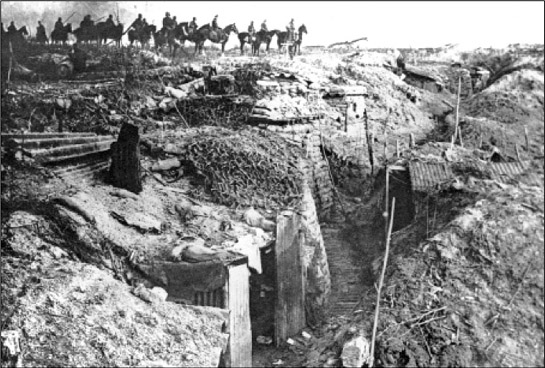

During the Third Battle of Ypres, better known as Passchendaele, incessant shelling shattered the delicate drainage systems of low-lying Flanders, converting the battlefield into a nearly impassable quagmire, as represented by these British gunners wrestling their piece forwards.

After the success of Messines, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig had to win support for his wider Flanders offensive from a reluctant British Government. After a furious debate, Lloyd George relented and the Third Battle of Ypres began. While the second stage of the battle achieved marked success, the fighting stagnated into grim futility in the mud around the village of Passchendaele.

As the BEF offensive at the Messines Ridge ran its successful course, Lloyd George began to get strategic cold feet regarding the continuation of Haig’s broader Flanders campaign. Even though the Prime Minister had strongly supported his commander-in-chief in his initial planning discussions with Pétain in May, Lloyd George judged that the strategic situation had changed so much since then as to warrant a thorough review of the entire Allied war effort. Russian societal collapse and French military disarray meant that any BEF effort to assail the might of German defences on the Western Front in 1917 would take place almost unaided, while, on the other hand, the United States’ entry into the conflict boded well for the strategic balance of 1918, when the Americans would be able finally to unleash their latent military might. Perhaps, reasoned Lloyd George, it would be best to stand on the defensive on the Western Front, and not risk a major battle, while awaiting the arrival of the Americans. Apart from strategic considerations, Lloyd George had other, more personal, reasons to question the wisdom of Haig’s Flanders planning. Political fallout from the Battle of the Somme had destroyed the career of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, a drama in which Lloyd George had played the major role. Leader of a tenuous alliance between elements of the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, Lloyd George was unsure of his grip on power. Another major attritional struggle on the Western Front, whether tactically warranted or not, might strain Lloyd George’s coalition to the breaking point and cause his own downfall, something that the Welsh politician could not countenance.

While he pondered his strategic and political options, in order both to streamline the British Government’s conduct of the war and to review war policy as a whole, Lloyd George created the War Policy Committee, which consisted of Lloyd George, General Jan Christian Smuts, Lord Milner, Lord Curzon, Arthur Balfour and Andrew Bonar Law. Holding its first formal meeting on 11 June, the War Policy Committee represented a bid by Lloyd George to wrest strategic control of the conflict from what he judged to be a military cabal formed by Haig as Commanderin-Chief and Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

At the meeting Lloyd George gave the members of the committee their mandate: they were to review all aspects of military and naval policy in all theatres of war. Based on their findings the committee would then dictate strategic policy. Lloyd George made his own feelings known that it would be a mistake to assail the German lines in France and argued that Allied policy should hinge on a defensive strategy in the west pending the arrival of American support, while attacking in Italy, which he considered a more profitable theatre of war. Impressed with the reasoning of the amateur strategist, the War Policy Committee agreed to place military planning for the remainder of 1917 on hold pending a meeting with Haig and Robertson.

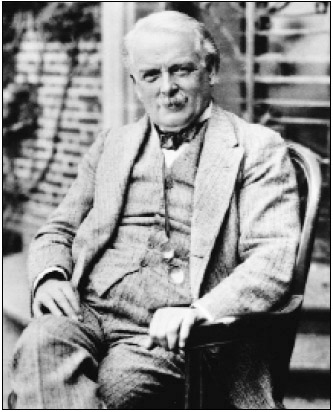

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The fiery Welsh politician sought to seize the strategic leadership of the Great War, and hoped to shift British emphasis away from the stalemated Western Front – a policy that led to an ongoing struggle with the leadership of the British military.

Although they were never on the best of social terms (Haig was from a gentlemanly background while the gruff Robertson had risen from the ranks), Haig and Robertson together formed one of the most potent alliances in British military history. While Haig was something of a natural optimist and Robertson was much more cautious in his military reasoning, the two men were staunch believers in the primacy of the Western Front and argued that allowing the initiative there to slip to the Germans would be a grave mistake. Based in London, Robertson immediately took note of the danger posed by the War Policy Committee and wrote to Haig expressing his desire to present a unified military front to the politicians in favour of continued operations in Flanders. Although Robertson had little hope that an offensive near Ypres would result in more than an important attritional victory, he put his own doubts aside and warned Haig:

‘What I do wish to impress on you is this: Don’t argue that you can finish the war this year, or that the German is already beaten. Argue that your plan is the best plan -as it is - that no other would be safe let alone decisive, and then leave them to reject your advice and mine. They dare not do that.’

On 19 June Haig journeyed to London to put his planning before the War Policy Committee, demonstrating troop movements on a raised map. As instructed by Robertson, Haig portrayed his planning as aimed at limited, methodical gains that would both keep the pressure on the Germans and seize important tactical positions in the area around Ypres. He also characterized the Belgian coastline as the only area on the Western Front where any greater results would be of immeasurable strategic value. Foreseeing another Somme and fearing for his political life, Lloyd George was livid and fixated on Haig’s broader strategic goals, recording in his memoirs:

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. As First Sea Lord, Jellicoe worried that the Royal Navy would not be able to defeat the German submarine threat, and gave critical support to the military plan to attack from Ypres and seize the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast.

It had long been a hallmark of British strategy to utilize the great strength and mobility of the Royal Navy to strike at Continental enemies through amphibious operations.

Soon after World War I had settled down into static fighting, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, advocated landing British troops on the Belgian coast, behind the German lines, stating to the military command, ‘Here at last you have their flank -if you care to use it. ... There is no limit to what could be done [using amphibious operations].’

For years, first Field Marshal Sir John French and then Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, as commanders of the BEF, made amphibious operations designed to turn the German flank in Belgium part of their overall planning for an offensive in Flanders. During the Third Battle of Ypres, in 1917, the amphibious operation, which planned to land up to three divisions on the Belgian coast utilizing innovative, flat-bottomed landing craft (the precursors to the landing craft of World War II) was held in constant readiness. However, Haig hoped to use the landing as a coup de grâce finally to crush the German lines in Belgium, a moment that never came, in part due to the onset of bad weather, which stalled the promising British victories of September and early October.

‘When Sir Douglas Haig explained his projects to the civilians, he spread on a table or desk a large map and made a dramatic use of both his hands to demonstrate how he proposed to sweep up the enemy - first the right hand brushing along the surface irresistibly, and then came the left, his outer finger ultimately touching the German frontier with the nail across.’

Lloyd George immediately questioned Haig’s planning and contended that the Allies had neither the preponderance in troops nor artillery to ensure a successful offensive. Citing a growing manpower shortage, the Prime Minister argued that Haig’s attack, if unsuccessful, could also leave Britain very weak and cede leadership within the Allied camp to the Americans. Although the assembled committee members agreed with Haig that an offensive in Flanders provided the best chance for achieving a meaningful victory, the majority concurred with the reasoning of Lloyd George and leaned toward a defensive stand on the Western Front pending an infusion of American military might. Haig’s Flanders plan seemed in serious jeopardy.

It is a time-honoured British military strategy not to allow a major land power to dominate the Continental coastline of the English Channel. However, in 1914 the Germans had captured the Belgian coastline of the Channel up to the area of Nieuport. From the beginning of the war the Admiralty and the Royal Navy had fretted over the German-dominated Channel ports and had demanded their recapture. Then First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill first sounded the alarm after the initial fall of the ports of Antwerp, Ostend and Zeebrugge in October 1914, and wrote to Field Marshal Sir John French:

A pilot of the Royal Flying Corps in France in 1917. Facing the danger of being shot down behind enemy lines, pilots were usually armed with a pistol for their protection.

‘But my dear friend, I do trust that you will realize how damnable it will be if the enemy settles down for the winter along lines that comprise Calais, Dunkirk or Ostend. There will be continual alarms and greatly added difficulties. We must have him off the Belgian coast!’

In support of military operations designed to retake the Belgian coastline, the Admiralty offered the firepower of the Royal Navy and the option of an amphibious landing to turn the German seaborne flank. While such considerations, along with concern about the security of cross-Channel communications vital to the survival of the BEF, were in the forefront of the military planning of both French and Haig, other battles and considerations had always intervened.

The advent of German unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917, though, had infused Admiralty demands concerning the strategic nature of the Belgian coast with greater urgency. Elevated from command of the Grand Fleet to the position of First Sea Lord in order to deal with the submarine threat, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe found the Royal Navy and Britain’s seaborne trade routes to be in grave peril. During April alone Allied and neutral shipping lost to submarine attacks reached 860,592 tonnes (847,000 tons), with an additional 325,135 tonnes (320,000 tons) of shipping damaged so badly that it needed to be taken out of service, totals that far exceeded German forecasts of losses required to starve Britain into submission. Although, due mainly to the belated introduction of the convoy system, Allied shipping losses fell to 609,628 tonnes (600,000 tons) in May, the wastage rate remained so high that Jellicoe despaired for the future.

German U-boats concentrated their efforts around British ports, hoping to sink ships as they slowed to enter the harbours. Initially the Germans met with great success, until the introduction of the convoy system. This diagram shows the principal area of British shipping losses in late 1917.

The day following Haig’s failed efforts to achieve approval for his Flanders planning, Jellicoe presented a strategic overview of the war at sea to the members of the War Policy Committee. The blunt and pessimistic testimony of the First Sea Lord proved to be a bombshell. Jellicoe stated:

‘That two points were in his mind, the first was that immense difficulties would be caused to the Navy if by the winter the Germans were not excluded from the Belgian coast. ... The position would become almost impossible ifthe Germans realized the use they could make of these ports. ... The second point he felt was that if we did not clear the Germans out of Zeebrugge before this winter we should have great difficulty in ever getting them out of it. The reason he gave was that he felt it to be improbable that we could go on with the war next year for lack of shipping. ... The Prime Minister said that ... [if Jellicoe’s statement] was accurate then we should have far more important decisions to consider than our plans of operations for this year, namely, the best method of making tracks for peace.’

Jellicoe’s opinion, though quite controversial, had the effect of tying Haig’s Flanders planning to the strategic well being of the British war effort as a whole. Unwilling to resist the unity of military opinion represented by the Commander-in-Chief, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff and the First Sea Lord, a majority of the members of the War Policy Committee shifted to a support of the continuation of Haig’s campaign. Incensed at being outmanoeuvred by military leaders whom he had hoped to control, at a War Policy Meeting on 21 June Lloyd George lashed out at his tormentors and lobbied again for attacks through Italy aimed at knocking Austria out of the conflict. Further, the Prime Minister contended that the rough parity of forces on the Western Front and a potential lack of French military support might result in Haig’s operation being a failure that would ‘lower the morale of the people, weaken the army, and above all, undermine the confidence in the military advisers on which the government acted’.

After a few more days of bickering, on 25 June at its 11th meeting, the War Policy Committee gave Robertson and Haig approval to proceed with preparations for offensive actions near Ypres. With only a month before the onset of operations, valuable time had been lost. Hedging its bets, though, the War Policy Committee only gave the offensive partial approval, and promised to reconsider its decision as the operation ran its course. After the war Lloyd George railed at the British military both for hoodwinking his Government into supporting the Third Battle of Ypres (or Passchendaele as it is commonly known) and then for badly botching the fighting itself. Much of the blame for the outcome of the battle, though, must fall to Lloyd George. Although he did not believe in Haig’s scheme, Lloyd George did not stop the battle, fearing for his own political life if he stood so brazenly against unified military opinion. The Prime Minister also could have called a halt to the fighting at any time during its course, but such a course of action would have called for Lloyd George to put his own career on the line, something that he was, in the end, unwilling to do.

General Sir William Robertson, who, as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, formed a powerful military alliance with Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig in favour of continued operations on the Western Front. He resigned in February 1918, being replaced by Sir Henry Wilson.

Eschewing the methodical Plumer, Haig made one of the most critical mistakes of his career and instead chose General Sir Hubert Gough to command his cherished and hard-won Flanders offensive. Gough had only limited familiarity with the terrain of Flanders, and had a reputation as a ‘thruster’. The situation was so bad that several leading figures in the BEF warned Haig that, although Vimy Ridge and Messines had conclusively proven the efficacy of limited attacks, he would diligently have to guard against Gough’s tendency to ‘rush through’ to decisive objectives. That Haig chose a man of Gough’s reputation indicates that, while the Commander-inChief understood the importance of limited goals, he hoped for much more in light of recent optimistic reports concerning the impending collapse of German military morale.

Gough’s military tendencies, when combined with Haig’s great hopes, led to a command breakdown. At the Somme, Haig had meddled too much in the planning of his subordinates, transforming a rather limited attack into one that pressed for a breakthrough and fatally dispersed the preparatory artillery barrage in the process. During the planning for Third Ypres, Haig, if anything, remained too aloof from the planning. Although he had become a convert to the idea of sustained, limited advances (hoping that a series of such small victories would cause a German collapse), Haig was unable clearly to impart his complicated reasoning to Gough, who ignored cogent military advice in an ill fated attempt to achieve a breakthrough.

In late May, Gough produced a first draft of his attack scheme, which called for a general advance across a broad front to great depth. Haig and his staff rejected the plan as too risky and warned Gough to concentrate the bulk of his offensive operations against Observatory Ridge and Gheluvelt Plateau on the right flank of the advance. German defences on the high ground there were considerable; the ground dominated the battlefield and if unconquered would enable the Germans to devastate the main assault further north with deadly enfilade fire. Haig also cautioned Gough that any attempts to have the infantry advance to depth would run afoul of the new German defensive system. Haig, through his head of operations General J.H. Davidson, advocated strictly limited offensives of only 1830m (2000 yards) in depth designed to destroy German reserves, and concluded; ‘An advance which is essentially deliberate and sustained may not achieve such important results on the first day of operations, but will in the long run be much more likely to obtain a decision.’

General Jan Christian Smuts (left). A South African and veteran of the Boer War, Smuts was sent to Britain to sit on the Imperial War Cabinet. It was a testament to Smuts’s abilities that he became a trusted member of the War Policy Committee under David Lloyd George.

Unhappy with the interference in his plans, produced by what he referred to as a ‘pedantic and if you like methodical mind’, Gough only claimed to take Haig’s advice into account. In the second incarnation of his Flanders plan, Gough allotted only one more corps and no additional artillery to the important right flank positions of Observatory Ridge and the Gheluvelt Plateau, far too small a force to ensure their capture. Gough asserted to his subordinate commanders that the coming offensive would take the form of a ‘series of organized attacks on a grand scale and on a broad frontage’, which in the end had the effect of diluting the all-important artillery preparation over too large an area as at the Somme. Worse still, Gough contended that the coming attack would be decisive in nature and that the men of Fifth Army would press on quickly to their final objectives, which would mean, ‘that after some 36 hours of fighting we had reached a state of open warfare with our main forces moving forward under cover of advanced guards’. In the face of the German defensive scheme, a weakened barrage, coupled with efforts at distant goals, portended disaster.

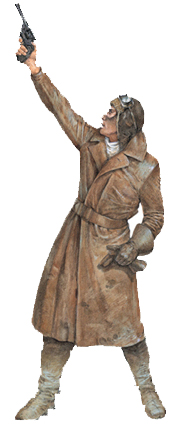

German soldiers inspecting a captured British trench. In an effort to instil an attacking mentality in its troops, the leadership of the BEF directed that front-line trenches not be overly elaborate, which often resulted in the British trenches being rather more rudimentary than German trenches.

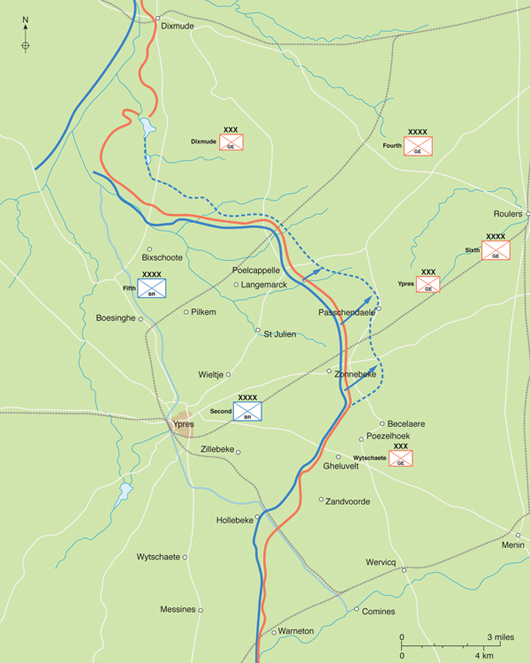

Haig’s original strategic hopes for the Third Battle of Ypres. The first line (1) represents the initial breakthrough, whilst the further lines (2) and (3) reflect Haig’s ambition of pushing through as far as Bruges and driving German forces away from the Belgian coast.

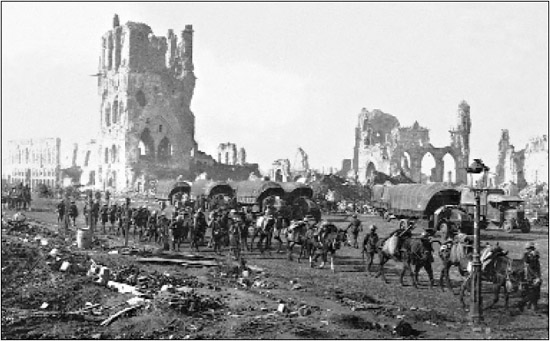

The ruins of the Belgian cathedral city ofYpres. Germans overlooking British positions from high ground around the stricken city could call down artillery fire on troop movements, making the Ypres Salient one of the most deadly areas of the Western Front.

Regardless of Haig’s directions, Gough pressed on in planning the attack that he thought best. Later, during the compilation of the British official history, Gough admitted his actions:

‘Put briefly, the main matter of difference was whether there should be a limited and defined objective or an undefined one. G.H.Q. favoured the former, I the latter. My principal reason was that I always had in mind the examples of many operations which had achieved much less than they might have done, owing to excessive caution. ...In all these operations victorious troops were halted at a pre-arranged line at the moment when the enemy was completely disorganized ... this was the argument which I used, I claim with complete justification, with Douglas Haig.’

For nearly two months, from their positions atop the surrounding high ground, the Germans had been watching British preparations in and around Ypres. Their observations left them in little doubt regarding British intentions. By 12 June, Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, commanding the Northern Group of German Armies, pronounced a British attack in Flanders as ‘certain’, and, forewarned of the coming attack, the Germans had put the lull between Messines and Third Ypres to good use. Colonel von Lossberg, the German ‘defensive battle expert’, arrived on the scene on 13 June and began to supervise the construction of one of the strongest German defensive systems of the war. The forward zone, dotted with concrete pillboxes, was thinly manned to avoid heavy losses, and was designed to break up and slow the British assault while giving ground. The battle zone consisted of more heavily manned strongpoints, designed to allow counterattack divisions to smash overextended attacking forces. In the third zone of defences lurked the heavy reserves, ready to move into the battle at a moment’s notice. If needed the Germans could withdraw at any point in the battle, giving ground in return for time to create new zones of defence farther to the rear. By the end of July, the German Fourth Army confidently awaited Gough’s assault.

On 16 July, the British preparatory bombardment opened, one of the heaviest of the entire war. The scale of the shelling impressed many, including D.H. Doe of the 51st Signal Company, who recorded in his diary:

‘At 3.45 the great bombardment commenced in full power along the whole front. ... I went out to watch it from the hill here + human eyes never saw a more terrible yet grand sight. The guns were flashing in thousands + one could see the big bursts of shrapnel etc.

... I could see the Germans frantic signals for artillery assistance - clusters of red rockets. They were going up in an absolutely frantic manner one after another. ... My word what a bombardment.’

Before the soldiers of the Fifth Army went ‘over the top’, nearly 3000 artillery pieces, including 754 heavy guns, had fired four million shells into the German lines. However, the weight of shell was spread too thinly in a vain attempt to bombard German positions to depth. Additionally, Gough had failed to concentrate adequate levels of artillery fire against the heavily defended and tactically critical ridge system on the British right flank. Finally, the nature of the terrain and improved camouflage techniques had made it harder both to locate and to neutralize German artillery. The barrage, though impressive, achieved only mixed results, leaving many attackers to face intact German barbed-wire entanglements and withering defensive fire.

As World War I progressed, trench warfare came to be dominated by heavier and heavier pieces of artillery, which could pound enemy trench lines and communications, but were difficult to move forward. Here British artillerists struggle to move a heavy howitzer.

The assault began at 3.50am on 31 July, under an overcast sky that prevented the Royal Flying Corps from undertaking effective spotting for the British artillery covering the assault, from right to left, of II, XIX, XVII and XIV corps of Fifth Army. Further to the British right, elements of Second Army aided in the offensive, while on the far left two divisions of the French First Army also moved forward. A creeping barrage assailed the German front-line defences for six minutes while the Allied infantry crossed no man’s land, and then crept forward at a rate of 91m (100 yards) every four minutes.

In the centre and on the left, XIX, XVII, XIV corps and the French First Army made good progress, keeping in close contact with the creeping barrage and finding many of the German defences in the area destroyed by artillery fire. Amid the advance, the Guards Division demonstrated great ingenuity and easily dealt with the tactical obstacle formed by the muddy Yser Canal by floating across using specially designed buoyant mats. Along much of the front most units reached their second objectives on schedule, and some of the leading brigades even pushed on to their third objectives as they neared the German battle zone. Within the plan advocated by Haig, the attack would have halted at this point, with some units having moved forward roughly three kilometres (two miles), to consolidate in preparation to face the inevitable counterattacks that were part and parcel of the German defensive system. Instead, though, Gough’s units, which were nearing exhaustion and losing cohesion, readied to move further forwards against fresh German units and into the teeth of the German defensive network. General Tim Harrington, with Plumer and Second Army on the far right of the British lines, put the tactical dilemma well, stating, ‘The further we penetrate his line, the stronger and more organised we find him ... [while] the weaker and more disorganised we become.’

‘The great brutal force of the initial blow has been parried. We survived the gruesome tension occasioned by the uncanny artillery fire, and we are able again to hold our heads high as the battle of living men is resumed.’

Max Osborn, official German observer at Ypres

While the attack had gone well in the centre and left of the British lines, II Corps attacking the Gheluvelt Plateau achieved no such success. Realizing the importance of dominating the high ground, the Germans had studded the ridge with concrete strongpoints and had concentrated their defensive artillery barrage in the area as well. In addition, German defensive lines on the ridge ran through a series of narrow defiles and three wooded areas – Shrewsbury Forest, Sanctuary Wood and Chateau Wood – which the British artillery barrage had converted into nearly impregnable masses of tangled and fallen trees. Mired amid the wilderness of tree stumps, trunks, branches and shell holes, the leading battalions of II Corps struggled forward, but could only watch helplessly as the creeping barrage advanced too quickly and moved out of sight. Facing intact German defences without the advantage of a covering barrage, the efforts of II Corps were in vain, and resulted in a gain of only 457m (500 yards).

The failure of II Corps to seize Gheluvelt Plateau forced the advancing British and French forces on the centre and left of the lines into a narrow salient, overlooked and covered by deadly enfilade fire from the unconquered right flank, even as German forces massed for a counterattack. By afternoon, the Germans struck the centre of the British salient, and though desperate fighting resulted, British forces, who were more prepared to attack than defend, were pressed back. German counterattacks also negated many of the meagre gains made by II Corps on Gheluvelt Plateau.

As the German counterattack programme ran its course, and rain began to fall that transformed much of the tortured landscape into a sea of mud, British units consolidated their gains. In terms of land captured, the first day of Third Ypres, though better than the first day of the Somme, was a disappointment. At the end of the day, at a cost of roughly 30,000 casualties, British forces in the centre and British and French forces on the left held gains roughly 2743m (3000 yards) into the German defensive system - roughly halfway to Gough’s overambitious goals. On the right flank, though, no gains had been made and the Gheluvelt Plateau remained in German hands. For such a meagre return, Fifth Army had lost 30 to 60 per cent of its fighting strength.

Gough had failed to heed the lessons of Vimy Ridge and Messines, and Haig, perhaps out of his own misguided optimism, had not held Gough to a strict adherence to the tactical idea of limited advance under cover of overwhelming firepower against the German defence-in-depth system. Instead of consolidating his forces after an advance of 1830 or even 2740m (2000 or 3000 yards) and then destroying German counterattacks, Gough had pressed on and placed the forces under his command at great risk. Essentially, Gough could have achieved the same advance at much less cost, while inflicting much greater damage on the Germans, had he adhered to the script of Messines.

Heavy German artillery in action. It was fire from such artillery pieces that destroyed the city of Ypres, and made British positions in the salient so vulnerable that Haig called for an attack in part to seize the high ground surrounding the city.

As part of their ongoing military evolution, the Germans began to develop stormtroop tactics, designed to infiltrate and exploit weaknesses in enemy trench systems – tactics depicted here in a stormtroop advance.

Although Haig publicly professed to be pleased with the first day of the offensive, privately he could not have been happy with Gough’s mishandling of his cherished Flanders campaign. Through a detailed tactical appreciation of the course of the day’s events, Haig admonished Gough to place greater effort on the overthrow of the Gheluvelt Plateau. Most importantly, though, Haig informed his reluctant subordinate yet again of the strengths of the German defensive system, and of the need to only advance to a depth of 1830m (2000 yards) as to not dilute the covering artillery bombardment. Such tactics would leave British troops fresh and with ample artillery support to crush German counterattacks. Haig closed his instructions by stating, ‘We must exhaust the enemy as much as possible, and ourselves as little as possible in the early stages of the fight.’

Although the orders were clear, and Haig was beginning to tire of Gough’s handling of the offensive, Gough again went his own way. Haig was learning, arguably slowly, the tactics that best suited World War I; but his command system remained ridden with faults – faults that allowed Gough another opportunity to bungle the Flanders offensive. Gough went on to plan his second major effort, made up of two distinct phases, including a preliminary assault by II Corps on the Gheluvelt Plateau, three days after which the main advance would continue. Although rain slowed preparations, on 10 August, after a two-day artillery bombardment, II Corps launched its assault. However, Gough had once again erred: II Corps had received scant reinforcements and no additional artillery support. In essence, II Corps attacked alone, into the same German defences with the same amount of covering fire that on 31 July had failed so miserably to achieve any positive results. The outcome of the attack was predictable: the advancing forces were held up by German defensive strongpoints and lost contact with the creeping barrage, and at the end of the day the Gheluvelt Plateau remained firmly in German hands.

The failure on the right flank should have precluded the continuance of the main attack, but instead, on 16 August, Gough launched his second major offensive, known as the Battle of Langemarck. On the right flank II Corps played a familiar refrain, driving a wedge into the German forward zone of defences on the Gheluvelt Plateau before losing contact with the creeping barrage and being driven back. In the centre and on the left, British and French forces achieved more substantial gains only to be thrown back from their furthest penetrations by German counterattacks.

Haig and his staff officers at GHQ were livid both at Gough’s continued wilful inability to follow the plan of limited advance and his inattention to the all-important right flank ridge system. Aware that he had incurred the wrath of his superiors, Gough attempted to share round the blame. At an army commander’s conference, when confronted with the failure to seize the Gheluvelt Plateau, Gough questioned the bravery of his men. Convinced that the divisions on the right flank had failed to advance out of weakness of character, Gough suggested that he would find and deal with those responsible. It was the last move of a desperate man.

Sergeant-Major J.S. Handley, who had already survived Second Ypres and the Somme, recorded his experiences in his diary:

‘On the 31st July, we returned to Railway Wood to do our bit in the opening phase of the great battle to finish the war - as we thought. As we entered the trenches about midnight, it began to drizzle, increased to a fine wetting rain, when, next morning at a quarter to four, which was zero hour, we went “over the top”. ... The tense ominous hours spent during the night waiting for zero hour, caused some men to pray, others to curse, and some to think and talk of home and loved ones. ... Awakened for the final “stand to”, one is oppressed by the deathly silence that always precedes a battle. The calm before the storm. Even the enemy seemed to be saving his ammunition for the imminent cataclysm. We wait, tense, resigned, each and every one of us, to meet his end or whatever pain and anguish fate holds in store for him. One gun breaks the heavy silence and in a split second comes ear-splitting thunder, as thousands of our massed guns fire simultaneously and continue firing, as we go forward to the attack. The whole battalion went forward in four waves or lines, with each company H.Q. in the centre of formation, but first we had to get through our own barbed wire. During the waiting period, parties, at intervals, went out, cut lanes through the wire and laid white tapes for the men to follow; then on getting out beyond our wire they would spread out into the waves. The first wave went forward on zero, immediately the guns fired the second wave went half a minute after, then over the parapet I climbed leading the company H. Q.; the other waves followed at half minute intervals. Following the white tape, I was horrified to find myself tangled up in our own wire. Knowing from experience, that the enemy would rain a deluge of blasting shells on our front line within three minutes, at the most, I frantically tore myself through the obstructing wire, hurrying forward out of the most dangerous area. When I felt clear I looked about me, but in the darkness could see no one. There was no sign of the acting-captain . his servant, signallers, first aid men, stretcher-bearers and so forth. As far as I could make out I was alone, but I went forward, till, suddenly I fell, tripped up by the German wire. As I plunged into the mud several rifle shots flashed and cracked past my head, and incidentally, for weeks afterwards I was partially deaf in the left ear.’

As the first day of Third Ypres proceeded Handley had his first contact with the deadly Flanders mud:

‘In my searchings I had come across a pack-mule sinking in the mud. His load had been removed and he had been left so far submerged when I saw him that only the top of his back, neck and head were above the mud. I’ll never forget the terror on his face with his eyes bulging out of their sockets. I just could not leave him in his agony, so, putting to his head a Smith and Wesson pistol I had found, I shot him.’

On 2 August, Handley’s brigade left the line. On their return to the rear Handley recorded what was, for him, one of the most moving experiences of World War I:

‘On marching back behind Ypres, Brigadier Duncan, that hard, stern soldier whom we feared, stood by the roadside taking the salute. “March to attention”, rang out the order; “Eyes right’“ and as we turned our heads we saw him standing erect, his right arm raised in the “salute” and – tears streaming down his face. It was indeed, a sorry brigade he saluted that day – the remnants of the battle-for barely a quarter of his men had returned.’

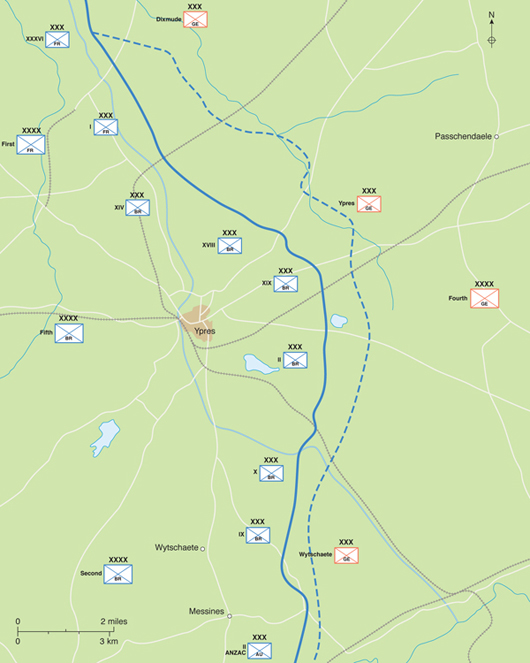

The gains made by the BEF on the opening day of the Third Battle of Ypres, gains that were much more limited than those called for in Haig’s initial planning. The early weeks of the battle saw Fifth Army lead the way, before Haig shifted the balance of the attack towards Second Army.

Perhaps worse, though, was the fact that Haig had realized what needed to be done in Flanders; he had come to understand the worth of step-by-step, methodical limited advances. However, instead of choosing Plumer, who thoroughly understood the nature of both limited advance and the German defensive system, Haig had chosen Gough in the hopes that he would better take advantage of any opportunities afforded by a great success. In what amounted to a meltdown of command, Gough had been unable to match his goals to the reality of the battlefield, and Haig proven unwilling to take the drastic action required to make good his command mistake until after the Battle of Langemarck. As the first stage of the campaign closed, though, Haig fullyrealized his error. In all, 22 divisions had been engaged in a series of battles that had cost 70,000 casualties, but had failed even to gain the objectives Gough had set out for the first day of the offensive. On 26 August, Haig belatedly shifted control of the Flanders campaign to Plumer, heralding the onset of a new and more productive phase of the Third Battle of Ypres.

Plumer, under close scrutiny from an increasingly vigilant Haig, devised a new plan, which involved a paramount effort to seize the Gheluvelt Plateau. In his planning, Plumer meant to avoid the problems that had beset the earlier efforts of Fifth Army by seizing the high ground through four limited attacks, each of which proposed to advance only 1370m (1500 yards), well within the range of British artillery fire. Using this method Plumer hoped to deal harshly with German counterattacks. For his attack on the plateau, Plumer also concentrated a level of artillery fire that was three times stronger than that utilized previously by Gough. Besides concentrating fire, Plumer and his staff worked to redress some of the shortcomings demonstrated by the artillery in the August offensives. Artillerists worked on communications and liaison problems with the infantry, and instituted advanced techniques such as sound ranging in their counterbatterywork. Finally, where the infantryunder Gough had advanced in waves, Plumer organized more flexible methods of attack, like those utilized at Messines, which included the use of skirmishing lines, specialist teams of bomb throwers and rifle grenadiers to deal with German strongpoints.

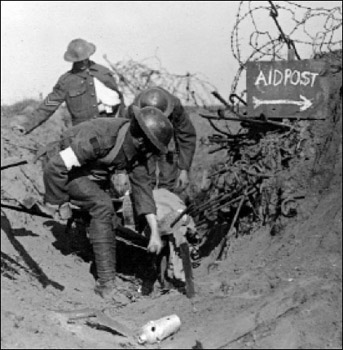

British stretcher-bearers navigating the maze of battlefield obstacles on their journey to the aid post. Such journeys were fraught with danger at the best of times, and became infinitely more difficult after the rains turned the battlefield into a sea of mud.

British artillerymen at rest during a lull in the shelling. By 1917 artillery techniques were much more advanced than earlier in the war, allowing for accurate and lethal shelling to guard infantry advances from interference and break up any enemy counterattacks.

After completion of the trademark meticulous preparation that came to typify Plumer’s battles, in clear weather on 20 September the infantry went ‘over the top’ at 5.40am, under the cover of a massive artillery barrage, into the Battle of the Menin Road. Advancing over the same ground of the Gheluvelt Plateau that had been twice captured and lost in August, British and Australian infantry quickly achieved their first objectives. After a short break to regroup, the infantry of the Second Army then moved out to seize their second and third objectives, only failing around an especially heavily defended area called Tower Hamlets. Further north, British and French forces did not have an artillery concentration equal to that of Second Army at Gheluvelt Plateau, but still enjoyed artillery fire twice as strong as that of the August offensives. Facing less formidable German defences, Allied forces in the centre and on the left flank achieved their ultimate goals with relative ease.

Plumer realized, though, that the true test of the battle was yet to come. Advance through the relatively thinly held German forward zone of defences had been swift, but now his forces had to hold against the inevitable counterattacks. Again, though, Plumer’s preparation paid dividends. The German official history commented that counterattack forces, meant to join battle at 8.00am, could not get into action ‘until late afternoon; for the tremendous British barrage fire caused serious loss of time and crippled the thrust power of the reserves’. In addition, every British assault division had held one brigade in reserve for use to defeat German counterattacks. Due to the tremendous difficulties imposed by Plumer’s scheme, the German counterattacks did not get underway until 5pm, and then were met by a ferocious British barrage and well entrenched, fresh British and Australian infantry. The Germans persisted in their efforts for five days, but the British, Australians and French did not lose their gains as they had in August.

In the Battle of the Menin Road, at a cost of 20,000 casualties, the Second Army, Fifth Army and French forces had achieved and held virtually all of their gains, seized much of the high ground around Ypres and now in some places overlooked the Germans. Troops that had taken part in the advance quickly rotated out of the battle, and fresh forces that had been held in reserve took their place even while the artillery began to move forwards. Although gains had admittedly been minimal, the BEF had once again proven itself capable of besting German defence-in-depth tactics. The short gain, also, was but part of a plan to bite off a critical chunk of the German defensive network, and then hold it against counterattacks, before further meticulous presentations enabled a repeating of the process. In short, Plumer was not involved in a battle, but rather a campaign in which battle victories led to further victories, which might result in a strategic gain. An enlisted man of the 55th Division commented favourably on Plumer’s technique:

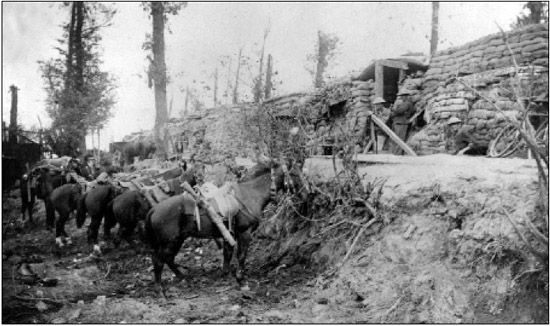

British cavalry at the ready near the front lines. Although it proved valuable on the Eastern Front and in the Middle East, cavalry was of little use on the crowded and lethal battlefields of the Western Front, dashing the hopes of the adherents of the breakthrough attack.

‘The advance up the slowly rising ridge to Passchendaele, once started, had to go on, but troops were not going over every day, as on the Somme. Periodical thrusts of greater compass had come to pass, and the creeping barrage. No longer could Jerry lie low in his dugouts, or in this case his pill-boxes, and know that the lifting of the barrage was an almost infallible signal of our attack. You followed the creeping shells now, and pounced on him still dazed and bewildered. The Somme had not been without its lessons.’

At dawn on 26 September, after careful artillery preparations, British, Empire and French forces around Ypres repeated their ‘bite-and-hold’ success in the Battle of Polygon Wood. Along a shorter frontage that enabled an even greater concentration of artillery firepower, attacking forces advanced to achieve their final goals, again with the exception of the stubbornly defended Tower Hamlets area. As before, German counterattack units had difficulty reaching the point of penetration in time, suffered heavy losses and failed to eject the attackers from their gains. With Allied forces having achieved virtually all of their objectives at a cost of only 15,000 casualties, Haig was understandably delighted, and was buoyed further by intelligence reports that indicated German strength in Flanders was crumbling.

Once Plumer’s Second Army became the main focus of the Allied attack the fighting became much more systematic, with a series of limited assaults aimed at securing specific objectives. This map shows the gains made between 16 August and 13 October 1917.

Although he had hoped to wait until 6 October, fearing the onset of poor weather, Plumer agreed to a 4 October launch date for a renewed attack. After moving his artillery into position, and making certain that his fresh units had practised their assaults and knew their roles in the attack well, Plumer altered his basic planning, and he decided to attempt to gain surprise by eschewing the customary preparatory artillery barrage. Instead, especially heavy artillery fire began only at zero hour as the troops went ‘over the top’.

As Plumer made ready to renew the battle, the Germans struggled to come to terms with Second Army’s methods. The continued fighting in Flanders had wounded the German military, while Plumer’s tactics had negated much of the benefit of the German defence-in-depth system. Ludendorff later recorded that the costly battles in Flanders:

Fokker DR I triplane. It entered service on the Western Front in mid-1917, and proved its worth when Werner Voss scored 10 victories flying a prototype of the aircraft in September 1917. The DRI also became the preferred aircraft of Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron.

‘…imposed a heavy strain on the Western troops. In spite of all the concrete protection they seemed more or less powerless under the enormous weight of the enemy’s artillery. At some points they no longer displayed that firmness which I, in common with the local commanders, had hoped for.’

‘The enemy contrived to adapt himself to our methods of employing counterattack divisions. There were no more attacks with unlimited objective, such as General Nivelle had made in the Aisne-Champagne battle. He [Plumer] was ready for our counterattacks, and prepared for them by exercising restraint in the exploitation of success.’

Increasingly concerned with the course of the Flanders fighting, and desperate to find a tactical solution to Plumer’s techniques, Ludendorffrushed to the battlefront to discuss defensive options. After debating a number of ideas, Ludendorff and the local commanders decided to lessen their reliance on counterattack and chose instead to concentrate more manpower in their forward defensive zone to stem the British tide.

As the Germans were in the process of altering their defensive scheme, Allied forces struck at dawn on 4 October, launching the Battle of Broodseinde. Everywhere, coordination between the artillery and the infantry, along with the continued use of infantry techniques that more reflected a semi-mobile state of warfare, allowed British and French forces to gain the German front lines before the defenders had adequate time to react. Unwittingly the Germans had played into Plumer’s hands, and Ludendorff later admitted that instead of halting the Allied advance, the concentration of German forces in the front lines merely resulted in a greater death toll and a higher number of prisoners in the face of the firepower and advanced infantry tactics of the BEF.

As in previous attacks, British, ANZAC and French forces achieved all of their admittedly limited goals, while artillery fire slaughtered the Germans who were packed into the front-line trenches. The heavy losses, including the capture of 5000 prisoners, prompted the German official history of the battle to refer to the fighting as ‘the black day of October 4th’, while a German regimental history described it as ‘the worst day yet experienced in the war’. Ludendorff, who despaired for the future and saw Broodseinde as ‘the culminating point of the crisis’, worked to rush further reinforcements to the scene, even diverting some from as far away as Italy, and revamped the German defensive system yet again. Faced with heavy losses, 159,000 men by this stage in the battle, one faction within the German high command favoured a limited withdrawal to delay further British advance. Crown Prince Rupprecht, in command of the armies in the area, pronounced the situation to be so desperate that he advocated ‘a comprehensive withdrawal’ that would even cede the German-held ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge to British control.

As the Germans considered their options, Haig, impressed both with the relative ease of the advance and the seemingly demoralized state of many of the German prisoners, pressed Plumer quickly to follow up the victory in hopes that the next step in the process might seize the Passchendaele Ridge and force the Germans to give way. Ludendorff and the Germans were becoming increasingly desperate, and perhaps Haig’s overoptimistic hopes were not that far from the mark. The Australian official historian of the war later commented:

In the Battle of Broodseinde, the Germans made the mistake of concentrating their forces too far forward, resulting in the loss of 5000 prisoners to the British, including these men being marched to the rear by British guards.

The famous evangelist Billy Sunday, who used his antiGerman sermons to whip American crowds into a fervour of support for the war effort.

Most soldiers on the Western Front were Christians, and to varying degrees turned to their religious faiths in time of war. On the home fronts, the Allies and Central Powers alike proclaimed that God was on their side and that their wars were righteous in nature. Religious figures in every nation did their best to place the war in terms of a religious crusade, perhaps best exemplified by the fiery sermons of evangelist Billy Sunday in the United States who compared German soldiers to a ‘great pack of wolfish Huns whose fangs drip with blood and gore’, and proclaimed the war to be a contest that pitted, ‘Germany against America, hell against heaven’. Military forces provided chaplains to minister to the religious needs of their soldiers, and while the French only had one chaplain per 12,000 men, most nations had considerably more. Many fighting men indeed turned to religion for solace during wartime, and even believed certain wartime religious myths, including that angels guided British efforts in the Battle of Mons. Some other soldiers, though, were more hard-bitten. On one occasion, a chaplain asked a group of British veterans if they were off to fight ‘God’s war’. The weary soldiers did not reply, prompting the chaplain to respond, ‘Don’t you believe in God’s war?’ One soldier looked at the chaplain and replied, ‘Sir, hadn’t you better keep your poor friend out of this bloody mess?’

‘For the first time in years, at noon on 4 October on the heights east of Ypres, British troops on the Western Front stood face to face with the possibility of decisive success ... Let the student ... ask himself “In view of the results of three step-by-step blows all successful, what will be the result of three more in the next fortnight?”‘

While the Germans reeled and Haig urged Plumer forwards yet again, the conditions that made Plumer’s successes possible in the first place began to evaporate. After the victory of 4 October, the rains returned to Flanders with a vengeance. Much of the area was very low lying and composed of reclaimed swampland, which relied on a complicated drainage system. The incessant shelling that had guarded the BEF’s advances, though, had battered the landscape beyond repair. Shell-holes filled with water, and the countryside transformed into a sea of nearly bottomless, oozing mud. It is a common myth that Haig should have foreseen such weather and horrific battlefield conditions. However, Haig could not have known that autumn, which often heralded the onset of fine weather in Flanders, in 1917, was going to be one of the wettest on record. He wanted to keep the pressure on the reeling Germans, and hoped that the rain would stop. It did not.

In addition to the rains, Plumer’s tactics had been complicated by their very success. Each battle required painstaking planning, and each leap forward required a difficult reshuffling of artillery. It was a complex dance of war. If Plumer waited too long to launch his next limited assault, the Germans would have more time to prepare. If he launched his next assault too quickly, the all-important artillery cover would not be adequate. Haig scheduled the next assault to take place on 9 October, which would have given Plumer enough time under normal circumstances. However, the rains and mud made moving artillery forward difficult in the extreme. Engineers had to create plank roads across the mud, which the Germans often shelled, while men and horses muscled the artillery forward one gun at a time. As it turns out, communications in the Ypres Salient had been showing strain even before 4 October; with the coming of the rains they had broken down.

The infantry also had a devilish time assembling in the waterlogged trenches to play their part in what would become known as the Battle of Poelcappelle. With agonizing slowness and great effort, soldiers made their way to their jumping-off points by traversing slick, narrow duckboard paths atop the mud. One soldier recalled:

Crowded into the confines of a sheltered area, Australian troops enjoy some of the last fine weather before the onset of rain in early October transformed the battlefields of Flanders into a sea of mud.

‘It was an absolute nightmare. Often we would have to stop and wait for up to half an hour, because all the time the duckboards were being blown up and men being blown off the track or simply slipping off. ... We were loaded like Christmas trees, so of course an explosion nearby or just the slightest thing would knock a man off balance and he would go off the track and right down into the muck.’

Many infantrymen did not reach their attack positions in time, while others found themselves exhausted by their exertions even before the attack began.

As the Allies moved forward on 9 October, it quickly became apparent that the artillery preparation had been spotty at best and had failed to silence either the German machine guns or artillery. With the failure of Plumer’s trademark careful preparations, the infantry paid the price. A private in the Lancashire Regiment recorded:

‘As dawn approached I could see the faint outline of a ridge about four or five hundred yards in front, and we then left the duckboards and moved to the white tape fastened to iron stakes. It was knee-deep in slush, and then I heard the sound of a heavy gun firing and immediately our barrage started; but we had not then arrived at the jumping-off point. Heavy German shells were already falling amongst us and shrapnel was flying all over the place. There were shouts and screams and men falling all around. The attack that should have started never got off the ground.’

The advancing infantry moved very slowly over swollen streams and waterlogged terrain, and quickly lost touch with the already ineffective covering barrage. German defenders, often behind intact barbed-wire entanglements and occupying concrete pillboxes, took a heavy toll on the advancing British and ANZAC forces. On most parts of the front, Second and Fifth Army failed to reach even their first objective, while on the right flank units that had lost touch with the barrage were forced back into their own trenches. Only in the north of the line, where the landscape had been less damaged by shellfire, did British and French forces make any significant advance from their startlines.

Unperturbed by the setback, both Haig and Plumer advocated a renewal of the offensive in three days’ time. Preparations, though, still proved quite difficult, which again negated the advantage that the British had enjoyed in Plumer’s previous successful assaults. Oddly enough, among the British senior command leadership, it was only a somewhat chastened Gough who counselled caution and a postponing of the attack to allow time for more thorough artillery work. After consultation with his subordinates, though, Plumer decided to go ahead with the First Battle of Passchendaele.

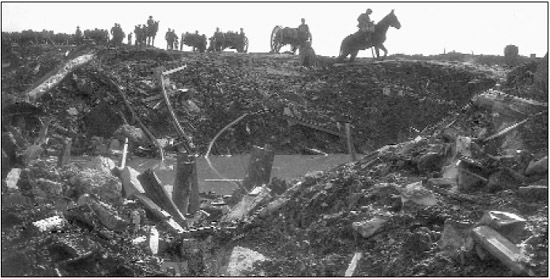

With its delicate drainage system shattered, the ground around Ypres became a wilderness of water-filled shell-holes, mud and duckboard tracks, across which men passed only with the greatest difficulty under constant enemy fire.

Under a leaden sky and continuous rainfall, at dawn on 12 October, Allied forces advanced once again into the sea of mud. The artillery had not been able to move further forwards, and the mud had rendered many existing firing platforms unstable. Additionally, many high-explosive shells sank into the mud upon impact, lessening their effect. Exhausted after having spent the night either in transit or mired in their own muddy trenches, the infantry again quickly lost touch with the creeping barrage, and their advance floundered with high casualties before undamaged German defensive works. Plumer had hoped that his forces would proceed through a series of three limited objectives and seize the village of Passchendaele. Instead, only on the left flank did XIV Corps even achieve its first objectives for the day. At other points of the line isolated infantry formations, fighting with great gallantry, moved into the German trench systems, only to be cut off and destroyed. Passchendaele had not fallen, the Germans had not broken, and the British offensive had once again bogged down. The air of futility that had surrounded Gough’s attacks in August had returned.

Haig had rescued his failed offensive by replacing Gough with Plumer. After the heady days of September and early October, Haig had just reason for optimism. For this reason, he and Plumer can perhaps be forgiven their mistakes at Poelcappelle and First Passchendaele. The Germans by their own admission were reeling, the rain had to end soon and there seemed to be a real chance that a continued series of victories in quick succession could have strategic results. Weather and the realities of attempting to sustain an advance in World War I, though, had conspired to wreck Haig’s planning. The offensive had reached its logical conclusion. Had the attacks ended at this point, Third Ypres might be remembered as a battle in which Haig had learned valuable lessons of command and in which the BEF had perfected the art of limited advance, only to have the elements deny what might have been an even greater victory. Instead, Haig chose to prolong the fighting, and Third Ypres would become known as Passchendaele for its final phase and will always be remembered only for mud and futility.

Two German soldiers converse at the bottom of a massive shell-hole, demonstrating the destructive force of firepower on theWestern Front.Aerial photography of the battlefield of Third Ypres revealed over a million shell-holes in only two and a half square kilometres (one square mile).

‘I stood up and looked over the front of my hole. There was just a dreary waste of mud and water, no relic of civilization, only shell holes. …And everywhere were bodies, English and German, in all stages of decomposition.’

Lieutenant Edwin Campion Vaughan

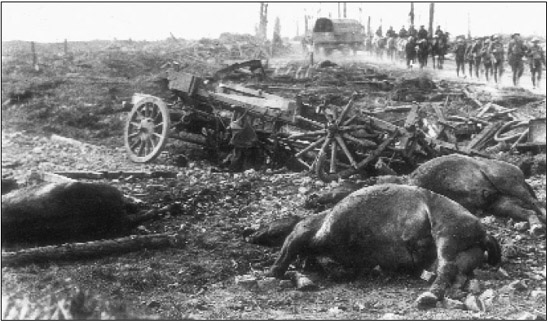

British troops pass the bloated bodies of dead horses and the wreckage of wagons at the apex of the Ypres Salient, known as ‘Hellfire Corner’, one of the most dangerous areas on the entire Western Front. The Germans targeted the crossroads to disrupt the flow of supplies and men to the front lines.

Haig, as it turned out, had come to the conclusion that the German lines in Flanders would hold, and instead chose to continue offensive operations there for other reasons. First he wanted to seize Passchendaele Ridge, both to give British forces a better defensive position and to allow them to move on to the high ground and exit the morass of mud in the valley below. Haig also had already begun to consider an offensive involving hundreds of tanks near Cambrai, and hoped that by keeping German attention squarely fixed on Flanders operations at Cambrai would achieve surprise. Most revealingly, perhaps, Haig wanted to seize Passchendaele to use it as a jumping-off point for further offensive operations in Flanders during 1918.

Planning a strictly limited advance, Plumer and Haig entrusted the assault on Passchendaele to the Canadian Corps, under the command of General Arthur Currie, which moved in as fresh reinforcements to replace II ANZAC Corps. Although he was not happy with the task, Currie agreed that the seizure of Passchendaele was possible, given time for better preparations than those at Poelcappelle and First Passchendaele. Plumer and Haig assented to Currie’s request for extra time to ready for the assault, and in turn the Canadian commander forecast that he would be able to take the ridge at a cost of 16,000 casualties. The Canadians, led by their chief engineer General W.B. Lindsay, worked feverishly to improve communications and logistic support in the area of attack and wrestled artillery pieces forward into firing position amid a break in the weather. The Canadians also built a plank road almost all of the way to the front line, enabling them to bring forward ammunition and supplies.

In the public imagination, the Third Battle of Ypres became known, in the main, for its final phase, in which British and Canadian soldiers struggled through a sea of endless mud toward their final goals. Experiencing the last days of the battle first-hand, Private A.V. Conn, recalled:

‘“Mud”: we slept in it, ate in it. It stretched for miles, a sea of stinking mud. The dead buried themselves in it. The wounded died in it. Men slithered around the lips of huge shell craters filled with mud & water. My first trip to this awful place was ... [at night]. For it was at night that men crept out of their holes at Passchendaele like rats. ... Each side of the [duckboard] track lie the debris of war. . Dead mules. Their intestines spewed out like long coils of piping. Here an arm & a leg. It was a nightmare journey. ... Finally dawn broke, a hopeless dawn. Shell-holes and mud. Round about rifles with fixed bayonets stuck in the mud marking the places where men had died & been sucked down’

Currie was thorough in his preparations, though even after two weeks of effort the Canadians were only able to utilize 60 per cent of their artillery, and planned to seize Passchendaele in four short, very limited assaults each of only 460m (500 yards) in depth. The steps, augmented by attacks by Fifth Army on the left flank, were to be separated by six days to prepare for the next forward move. Attacks were to be guarded by a creeping barrage of 640m (700 yards) in depth that advanced 90m (100 yards) every eight minutes.

The offensive, known as the Second Battle of Passchendaele, began at dawn on 26 October once again under the cover of an effective barrage. On the gently sloping ground of the Passchendaele Ridge, the Canadians achieved all of their goals, utilizing grenades to subdue the remaining German pillboxes in the area of advance. On the left flank, though, Gough’s Fifth Army was not so lucky. Advancing through the lowest territory in the region, some of the men of the 58th and the 63rd divisions sank in the mud up to their shoulders. Losing 2000 casualties, Gough’s men achieved virtually no gains amid some of the worst conditions of the entire war.

Private A.V. Conn took part in, and was wounded during, this stage of the offensive. He recorded his experiences in his memoir:

‘I just raised the bottle [of rum] to my lips when I felt a terrific blow on my right arm. I never heard the shell burst, but it was a 5.9 which had dropped very near our shell-hole. My mate who had taken my place [as lookout] fell back into the shell-hole; his head was shattered & cracked right open; he fell past us into the water in the bottom of the shell-hole. ...I stared stupidly at my arm; the jagged pieces of white bone were poking through a great gash in my forearm; my wrist was open & the blood was welling through & down my side; also there [was] a large wound on my right shoulder.... They always said that you never heard the shell that was going to hit you.’

Conn then had to make his way to the dressing station:

‘I am not very good at this kind of thing-real writers could do all this so much better. ... You know we lost a quarter of a million men in this sector; many thousands of them were unidentified. The dead buried themselves at Passchendaele, the mud sucked them down deeper & deeper. . It was daylight when we started back & the things that were mercifully hidden by the darkness of night were now revealed to us in the light of day. All had their story to tell, – men who had struggled back only to give up & die when their strength failed them. Manyhad been pushed off the track to the sides to sink partly in the mud. There were mules & horses whose very intestines were spewing out of their swollen bloated bellies. The dead, their yellow teeth bared in ghastly grins, friend & foe alike were all clothed in the same filthy mud.’

After four days, amid yet another downpour, Canadian and British forces advanced again on 30 October and achieved similar results, the Canadians reaching their final objective and inching farther up the slope towards Passchendaele while the affiliated units of the Fifth Army on the left remained mired in the morass and made no progress. As a result of the impassable conditions on the left flank, Haig and Plumer decided that the final push on the village of Passchendaele would fall to the Canadians alone.

On 6 November, the 1st Canadian Division, attacking from the southeast, and the 2nd Canadian Division, attacking from the south, converged on Passchendaele. Having thoroughly practised the varied elements of their short assault and operating under the cover of a withering artillery barrage, the Canadians struggled through the sucking mud and seized their final objectives and most of the village. On 10 November, the Canadians captured the remainder of Passchendaele and much of the rest of the ridge. At this point Haig called the offensive to a close.

The watery desolation that formed the battlefield at Passchendaele made forward movement almost impossible, while living conditions for the combatants became nearly unbearable. The battle has come to be seen as a byword for the suffering of the ordinary soldier on the Western Front.

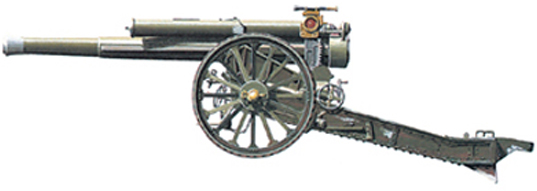

The British BL 60-pounder Mk 1. Classed as a heavy gun, the 60-pounder was often used for counterbattery work, and could fire a 27kg (60lb) shell over nine kilometres (six miles). Weighing 4 tonnes (4.4 tons), moving the weapon required a team of eight horses.

The results of the final stage of the Third Battle of Ypres were decidedly mixed. Often obscured by the conditions of the battlefield is the fact that Currie and the Canadians had achieved their admittedly limited goals, actually suffering fewer than the projected 16,000 casualties in the process. Even in the worst of conditions, thorough artillery and infantry preparations had led to effective limited gains. However, the question remains: were the gains, no matter how effectively and bravely won, worth the terrible cost? The conditions of the advance brought the question into even sharper focus and were described by a British gunner:

British forces traverse the tortured remains of the Menin Road, which, in Haig’s initial plan, was to have been the road to victory in Flanders. The Menin Gate, at the entrance to Ypres, is now a major memorial to the missing.

‘The conditions are awful, beyond description, nothing we’ve had yet has come up to it, the whole trouble is the weather which daily gets worse One’s admiration goes out to the infantry who attack and gain ground under these conditions Had I a descriptive pen I could picture to you the squalor and wretchedness of it all and through it the wonder of the men who carry on Figure to yourself desolate wilderness of water-filled shell craters, and crater after crater whose lips form narrow peninsulas along which one can at best pick but a slow and precarious way Here a shattered tree trunk, there a wrecked “pillbox”, sole remaining evidence that this was once a human and inhabited land. Dante would never have condemned lost souls to wander in so terrible a purgatory. Here a shattered wagon, there a gun mired to the muzzle in mud which grips like glue, even the birds and rats have forsaken so unnatural a spot. Mile after mile of the same unending dreariness, landmarks are gone, of whole villages hardly a pile of bricks amongst the mud marks the site. You see it best under a leaden sky with a chill drizzle falling, each hour an eternity, each dragging step a nightmare. How weirdly it recalls some half-formed horror of childish nightmare.’

The Third Battle of Ypres, along with the Somme, has gone down in history as the very symbol of the futility of the British effort on the Western Front and has been the primary fuel of the argument that the BEF was an army of lions led by donkeys. On the surface the outcome of Third Ypres indeed closely mirrors that of the Somme: at a cost of 250,000 casualties the BEF had failed even to gain the final objectives that Gough had set for the first day of the campaign. However, coming to terms with the place of Third Ypres in history, even after the passage of 90 years, remains difficult. After the close of the conflict military personnel on both sides viewed the Flanders campaign as a hard-fought victory that was of central importance to the eventual winning of the war by the Allies. General Hermann von Kuhl, Chief of Staff to Crown Prince Rupprecht during the battle, remarked in his memoirs that Third Ypres had greatly depleted German reserves:

‘On this point Field Marshal Haig has been quite right: if he did not actually break through the German front, the Flanders battle consumed the German strength to such a degree that the harm done could no longer be repaired. The sharp edge of the German sword had become jagged.’

Air Marshal Hugh Trenchard took his assessment of the battle even further during World War II:

‘Tactically it was a failure, but strategically it was a success, and a brilliant success – in fact, it saved the world

‘There is not the slightest doubt, in my opinion, that France would have gone out of the war if Haig had not fought Passchendaele, like they did in 1940 in this war, and had France gone out of the war I feel, as all our manpower was in France, we should have been bound to collapse, or, at any rate, it would have lengthened the war for years ‘

In truth, the verdict of Third Ypres lies somewhere between the two reactive extremes. It was not simply a battle of mud and futility. On the other hand it was also not the battle that saved the world. The campaign had done great service by not allowing the Germans to attack the beleaguered French. The Germans, who lost a total of 260,000 men in the battle, were much less better able to replace their losses than the Allies, which contributed to the ultimate German inability to achieve victory in their offensives of 1918 and to the final German collapse by the end of that year. It was a battle, though, that also demonstrated the complexities of a BEF that was undergoing dramatic change from an amateur force to a fully professional military. The first stage of the battle demonstrated deep flaws in the command structure of the BEF. Under Plumer, British and Empire forces proved that they had learned much and improved since the Somme and were able to defeat the most powerful German defensive systems in bite-and-hold offensives.

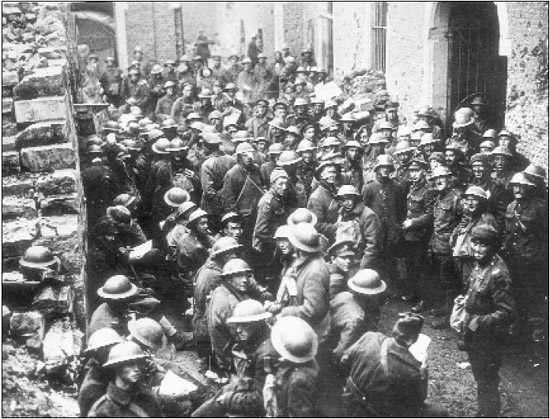

Canadian soldiers (and at least one sullen German prisoner) gather near an aid station after having survived the fighting at Passchendaele. The Canadians were highly rated for their fighting skills after their success at Vimy Ridge.

The final stage of the battle, though the Canadians once again demonstrated their bravery, proved disastrous. Hoping for great results, Haig had rushed the offensive, negating many of the methodical preparations that had made victory possible, and pressed on through horrific conditions toward questionable goals for dubious reasons. Haig had made mistakes at the Somme, but his errors there could be forgiven since it was his first major battle as commander of the BEF. After Passchendaele, though, Haig would receive no such historical absolution. His failure to halt the battle after it had run its course, allowing the fighting to grind down and stall in the mud, would forever overshadow the hopeful aspects of change indicated by Plumer’s limited gains during September and October. The BEF was evolving into a professional military capable of decisive victory in 1918. However, Haig’s reputation would remain mired in the mud of Flanders. In 1935 an article in the News Chronicle said in relation to Haig’s reputation, ‘Why has not Haig been recognized as one of England’s great generals? Why, as a national figure, did he count for less than Lord Roberts, whose wars were picnics by comparison? The answer may be given in one word - Passchendaele.’

A British Great War cemetery. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission determined to inter the dead near to where they had fallen, and that there should be no distinction made on account of rank, race or creed.

The final advances during the Third Battle of Ypres. This map shows the final assaults of the campaign, culminating in the seizure of the village and ridge of Passchendaele itself by the Canadian Corps from 6 to 10 November.Haig called off the offensive once Passchendaele was secured.