British troops ready for battle. As 1917 drew to a close, new technologies and tactics altered the balance of the battlefield in World War I, once again bringing aggressive infantry tactics to the fore.

The Battle of Cambrai saw the first massed use of armour in warfare, while both British and German tactical advances evidenced at Cambrai heralded a sea change in modern conflict. Even as the combatant nations of Europe fought to yet another costly draw, though, the United States began to marshal its military might and stood ready to change the world.

The fitful progress of the Third Battle of Ypres further strained the already damaged relations between Haig and Lloyd George. The War Policy Committee had only approved Haig’s offensive with great reluctance and against the wishes of the Prime Minister. Advances in tactics and attriting German military strength seemed only pyrrhic victories to the embattled Lloyd George, who in turn became less and less patient with Haig, Robertson and the command structure of the BEF. As the prospects for strategic victory in Flanders dwindled and casualties mounted, the War Policy Committee brought considerable criticism to bear on Robertson and Haig, focusing on the overly optimistic projections that had preceded the offensive, and Lloyd George again spoke in favour of shifting offensive action away from the Western Front. In a critical failure of political will, though, instead of ending the Flanders campaign, as was its right, the War Policy Committee contented itself with sniping at Haig’s operation from the sideline. In the words of historians Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson:

German Albatross DVa fighter plane. Produced in late 1917 as an answer to the Allied Sopwith Pup and SE 5, the Albatross DVa was widely used, but arguably still outclassed by the Allied fighters.

‘None of Lloyd George or Smuts or Curzon or Milner or Bonar Law seemed to be noticing that the Flanders campaign was his responsibility. It would continue not another day if they denied it authorization.... The most the nation’s civilian rulers might do regarding it [Third Ypres] was wring their hands and look about for additional military advisors to offer a “second opinion.” ... So as the rain fell in Flanders and thousands of Haig’s soldiers prepared to struggle through mud to their doom, the Prime Minister who was proclaiming the futility of this undertaking failed to raise a finger to stop it.’

There did, however, remain a military postscript to the Third Battle of Ypres. Proponents of the use of the tank had long advocated using armour en masse against German lines, instead of only in a piecemeal fashion as adjuncts to infantry. Although Haig was a chief proponent of the new weapons system, tanks had remained unreliable, few in number and of only marginal use in the great trench battles of 1917. As the year continued and improved models of the tank appeared, though, Brigadier-General Hugh Elles, the Tank Corps commandant, and his senior staff officer Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, began, with renewed vigour, to press for an opportunity to use tanks in large numbers over suitable terrain. At the same time, General Julian Byng, in command of Third Army, developed a proposal for an offensive in the area of Cambrai, where German defences were particularly weak. Although he was intrigued by both ideas, Haig initially rejected them because the ongoing fighting around Ypres meant that reserve forces were in short supply. By mid-October, as the offensive in Flanders was winding down, though, the planning of the Tank Corps and Third Army had coalesced into a single proposal for a mixed tank and infantry assault on Cambrai. Although reserves were scarce, Haig realized that the conclusion to Third Ypres was at hand, and understood the need for a victory to mollify the politicians in London, and thus gave Byng’s plan his blessing.

With little time to shift tanks from all over the British front to Cambrai, the Tank Corps worked feverishly to prepare for the start date of the attack. After practising tank-infantry cooperation, the tanks had to be entrained, transported to the new front and detrained, all in the greatest secrecy and only at night. From the railheads the tanks were driven, also at night, to assembly areas secreted away in the Havrincourt Wood on the front of IV Corps to await the attack.

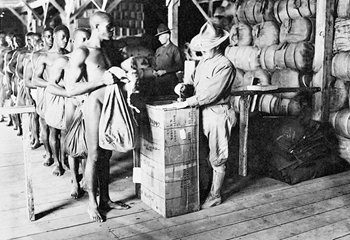

While logisticians went about gathering the tanks, ammunition and supporting arms, the tacticians at Tank Corps headquarters had to solve a number of technical difficulties before the opening of the offensive. The most critical problem was the fact that the line to be assaulted included the first three trenches of the main Hindenburg Line, which were too wide for the tanks to cross. After trial and error, the Tank Corps decided that each tank should carry a massive, compressed bundle of sticks known as a ‘fascine’. Triggering a mechanism inside the tank released the bundle of sticks, blocking the trench and creating a bridge for the tank to cross. Central Workshops assembled 21,000 of the bundles, utilizing a thousand Chinese labour troops for the purpose. The fascines were then bound by chains and compressed by 18 specially designed tanks, which, according to a history of the Tank Corps,’... acted in pairs pulling in opposite directions at steel chains which had previously been wound around the bundles. ... So great was the pressure thus exerted that months afterwards, an infantryman in search of firewood, who found one of these fascines and gaily filed through its binding chain, was killed by the sudden springing open of the bundle.’

Although tanks, like this one pictured in training, were few in number and mechanically unreliable in their debut in the Battle of the Somme, Haig had seen their potential and remained a proponent of the new weapons system.

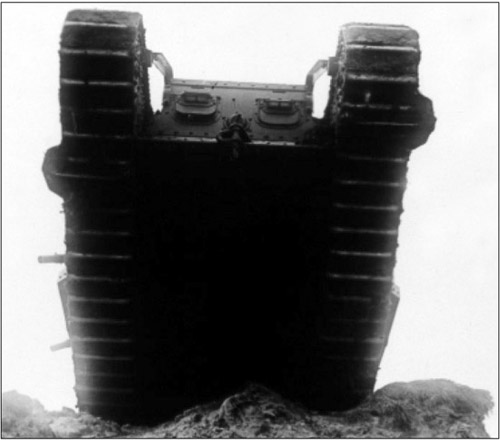

Their caterpillar tracks notwithstanding, World War I tanks, like the one in this photograph, often had difficulty in crossing enemy trenches, resulting in the plan to use bundled sticks, known as fascines, to cross enemy trenches in the Battle of Cambrai.

The Tank Corps also worked to overcome the endemic supply and mechanical difficulties that had plagued all previous use of tanks in battle. For the offensive, a total of 98 supply tanks, some towing sleds heaped with petrol, oil and ammunition, supported the 378 fighting tanks, while only 54 tanks were held in reserve.

Although Cambrai is best known as the first major tactical use of the tank in battle, the attention lavished on the role of armour in the campaign has served to mask a more significant innovation in artillery technique. In previous battles, to get the range of their targets gunners had to fire several rounds and then observe and adjust fire, resulting in the BEF sacrificing surprise in favour of punishing, cumbersome preparatory artillery barrages. However, on-the-job training, more accurate mapping, better use of meteorological data and efficient calibration of the guns themselves had resulted in an artillery technique known as ‘silent registration’. Additionally, gunners had also become more familiar with the effects of barrel wear on the flight of shells, while the shells themselves were of more uniform quality.

The tank was not a war-winning weapon in World War I. It would require inter-war technological advances to bring the tank into its own.

The tactical riddle posed by the trench deadlock led to a number of technological innovations designed to rekindle the power of the offensive, the most important of which was the British development of the tank. Early experiments with armoured tractors, propelled by caterpillar treads, though, were failures. With the support of Winston Churchill, however, in 1915 the Admiralty Landships Committee took over the task of designing a weapon capable of breaking through trenches, but got nowhere until Ernest Swinton joined the design team. Hoping to maintain secrecy, the builders of the new vehicle called it a water carrier, or tank. By 1916, tests of the first lozenge-shaped prototype went so well that the War Office ordered a hundred of what became known as the Mark I tank. The armoured vehicle contained a 105hp Daimler engine that produced a maximum speed of six kilometres per hour (3.7mph) and a range of 35km (22 miles), and carried a crew of four men. Half of the Mark Is, dubbed ‘males’, sported 6-pounder naval guns mounted in turrets on either side of the vehicle, while, the other Mark Is, dubbed ‘females’, carried four side-mounted Vickers machine guns. The success of the few Mark Is that saw action at the Somme prompted Douglas Haig to order a thousand more such vehicles, which were to prove the success of the concept at the Battle of Cambrai. As the war progressed, tank design modernized, culminating in the more reliable and powerful British Mark V tank, which saw service in great numbers in the Battle of Amiens and the Hundred Days. Improvements notwithstanding, even in 1918 tanks remained too slow and unreliable to be a truly war-winning weapon.

Refinements in aerial photography also helped accurately to locate enemy defences, while techniques known as flash spotting and sound ranging fixed enemy gun positions.

For the first time, then, British guns could ensure accurate fire on German positions without sacrificing surprise to pre-registration. Confident in the newfound abilities of the British artillery, Byng chose to forego a preliminary bombardment. However, he also surprisingly decided not to employ a creeping barrage, which had become standard practice in the BEF. Instead, Byng planned for the tanks to crush the barbed wire and to keep the Germans cowering in their trenches rather than manning their defensive positions. To carry out their vital role, replacing both a preparatory and a creeping barrage, the tanks would advance in the van of the offensive, something that they had not done since the Somme over a year before.

At dawn on 20 November, the five infantry divisions and the tanks of the Third Army’s III and IV corps moved forward, supported by 1003 artillery pieces and the Royal Flying Corps acting in a ground-attack role. Due to Byng’s careful preparations, the offensive caught the two defending German divisions and their supporting 150 artillery pieces totally by surprise, a far cry from the opening days at the Somme and Third Ypres. The tanks led the assault and quickly gained the German front lines; unheralded by a preliminary barrage and emerging from under the cover of a thick mist and a smoke screen, the tanks suddenly burst upon the German defenders, sowing fear and chaos. One British soldier recalled the stunning effects of the tanks, ‘The German outposts . were overrun in an instant. The triple belts of wire were crossed as if they had been beds of nettles. .The defenders of the front trench . saw the leading tanks almost upon them . [and] were running panic stricken, casting away arms and equipment.’

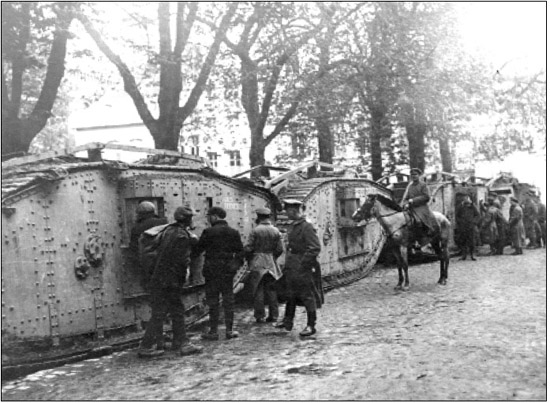

Although many Germans were initially terrified by the sight of tanks, the German high command soon developed antitank weaponry and tactics that took a heavy toll on the slow moving machines, including these tanks that have been captured by German forces.

The attack quickly rumbled through the first and second defensive networks of the vaunted Hindenburg Line, and, in most places along the 10km (six-mile) front, Third Army seized all of its intended objectives, advancing up to eight kilometres (five miles), something that had not been achieved in four months of fighting at Third Ypres. The results, though, were far from perfect. On the left flank, near Flesquieres village, the 51st (Highland) Division failed to achieve a meaningful advance against a stubborn German defence, which included the use of anti-tank guns. As a result of the check, Third Army was unable to seize the dominating high ground of Bourlon Wood. Making matters worse, the tanks suffered heavy losses on the first day of the offensive. Several were lost to German fire and mechanical malfunctions, but in many instances crews were simply incapacitated by the sheer physical effort of operating the tanks due to high interior temperatures and carbon monoxide poisoning. Lacking a method of communication, by the end of the day even the 297 operational tanks that remained had lost all semblance of tactical unit cohesion.

British gains during the first stage of the Battle ofCambrai, gains so great that church bells in England pealed for the first time since the beginning of the war. Subsequent German counterattacks retook much of the captured ground.

To this point the Battle of Cambrai was another example of British tactical proficiency, utilizing startlingly new techniques to achieve nearly unheard of gains, including the capture of more than 4000 prisoners at slight cost. While Haig and Byng had realized that a limited advance at Cambrai would reap an attritional advantage, they had also hoped for greater things, and, as a result, the cavalry was on hand in an attempt to exploit any wider success. Hampered by the approach of darkness, the cavalry did move forward, but, after achieving initial gains, failed to pierce the final lines of German resistance. Haig’s plan had arguably succeeded, for the Third Army had achieved an almost complete breakthrough of the vaunted Hindenburg Line. However, both tanks and the cavalry had failed as weapons of exploitation and, even though the BEF had attained tactical mastery, the defensive remained dominant, and it proved impossible to maintain the momentum of battle and rupture the German lines

Some of the 4000 German prisoners taken during the quick British advance at Cambrai. The combination of the new artillery tactics and the shock value of the armoured assault led to the German line collapsing in a number of places.

If there had ever been a chance to achieve a greater success, it had passed with the close of the first day of the Battle of Cambrai. With no other available reserves, weakened as the BEF was from Third Ypres, there remained little Haig could do to further his initial victory. The preconditions that had enabled Third Army to achieve its stunning success had evaporated: surprise was gone, the tanks, fewer and fewer in number, had lost their unit cohesion, artillery fire as usual dwindled in its effectiveness as the gunners laboriously wrestled their pieces forwards, and the units engaged in the battle were under strength and tired, while the Germans rushed both infantry and artillery reserves to the area. The check of the initial advance around Flesquieres, though, had resulted in the British gains being limited to a pronounced salient. In an effort to straighten the lines of Third Army and make the salient less vulnerable, Haig and Byng pressed the attack for a further seven days, in an attempt to capture Bourlon Ridge.

‘With the help of their tanks, the enemy broke through our series of obstacles and positions which had been entirely undamaged.… At the end of the year, therefore, a breach in our line appeared to be a certainty.’

Paul von Hindenburg, 19 November 1917

As demonstrated in this photograph, German prisoners were often enlisted to aid British medics and stretcher-bearers in the clearing of wounded from the battlefield. In this case a winch has been used to haul a stretcher out of a dugout.

By 27 November, IV Corps of Third Army succeeded in taking most of the ridge in a series of limited, attritional struggles, and the offensive ground to a halt while the surviving tanks exited the area to regroup. Although the fighting around Bourlon Ridge had been difficult, Third Army had achieved a major tactical success and began to settle into its new defensive lines for the winter. The Battle of Cambrai, such a quick advance when compared to Third Ypres, had seemingly salvaged Haig’s reputation. In Britain there had been great celebration of the victory, with the ringing of church bells for the first time since the onset of the war. However, the celebration was premature, for Ludendorff, though he had been caused great anxiety by the initial British gains, believed that the newly formed British salient at Cambrai was the perfect place to test new German operational techniques and gathered reinforcements for a massive counterattack.

It was now the turn of the British Third Army to be surprised, as the tired men of III and IV corps faced an attack by 25 fresh German divisions. Only IV Corps in the northern part of the salient noticed the German preparations and made ready, while forces in the remainder of the salient retained an offensive posture. In some ways the British had advanced too far too fast, and were now to pay the price. The failure first to notice and then to prepare for the onslaught must fall in part to Byng, but mainly resides with Haig, who later took full responsibility for the resulting setback. On 30 November, the Germans struck, utilizing methods of attack similar to those employed by the BEF, which would be perfected and become familiar in their Spring Offensives of 1918, including a short, precise artillery barrage, infiltration tactics (dubbed stormtroop tactics) and low-flying aircraft in a ground-attack role. In the north, where IV Corps had anticipated the attack, the Germans faced intense defensive artillery fire and made scant gains. In the south, though, the attackers caught III and VII corps off guard and pushed the British back beyond their start point of the Cambrai offensive. Tanks of the 2nd Tank Brigade, which had been withdrawn from the salient but were not too far distant from the battlefield, returned to the fighting and helped check the German advance.

Ludendorff and the Germans now faced the tactical reality that bedevilled all Allied efforts to advance on the Western Front, for the British rushed reinforcements to the scene even as the Germans outstripped their artillery support and the attack lost its forward momentum. By 7 December, the Battle of Cambrai drew to a close, with both sides having gained a roughly equal amount of territory each at a cost of 50,000 casualties. Although the inconclusive battle was small when compared to the Somme or Third Ypres, it was their equal in importance. The innovative tactics of both the BEF and the Germans -modern, all-arms tactics - presaged a revolution in modern warfare and the resurgence of the offensive.

Haig’s great victoryhad turned, at best, into a costly draw, which nearly brought his career crashing down in a situation that closely resembled that of Nivelle in the wake of the failed attack on the Chemin des Dames. Still smarting over the meagre tangible results of Third Ypres, Lloyd George had at first been silenced by Haig’s success at Cambrai. The German counterattack, though, convinced the Prime Minister of the futility of attempting to seek a military solution on the Western Front, and Lloyd George decided once again to find some wayto wrest strategic control of the war from Haig and Robertson.

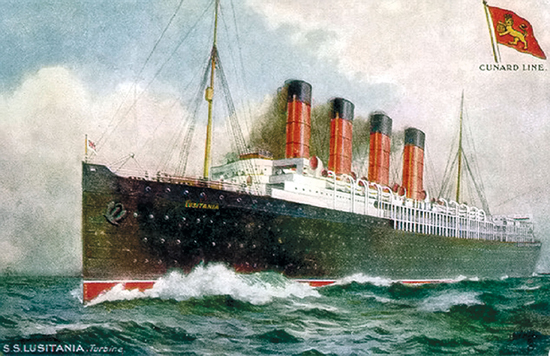

The Cunard liner Lusitania, which was torpedoed on 7 May 1915 by U20 off the coast of southern Ireland , with the loss of 1198 lives, including 128 Americans. The attack caused the suspension of the U-boat campaign against merchant shipping until spring 1916.

Complicating matters further, seismic events in the other theatres of World War I suddenly convinced Haig, perhaps the ultimate optimist, that the initiative in the conflict had shifted. Even while the British and French had to send forces to the Italian Front in the wake of the Italian setback at Caporetto, the collapse of Russia enabled the Germans to begin to shift the preponderance of their military strength to the Western Front. In a volte-face that stunned Lloyd George, Haig and Robertson, far from preaching imminent victory, urged the government to send all available troops to the Western Front to redress a forecast increasing imbalance in manpower. The shift in strategic fortunes galvanized Lloyd George to action, and a letter from Robertson served to warn Haig of the coming storm:

‘His [Lloyd George’s] great argument is that you have for long said that the Germans are well on the down-grade in morale and numbers and that you advised attacking them though some 30 Divisions should come from Russia; and yet only a few Divisions have come, and you are hard put to it to hold your own! He claims that five Divisions [that the government had directed sent] to Italy and absence of necessary drafts are not sufficient to account for the Cambrai events, but that the latter are due to Charteris’s error of judgment as to the numbers and efficiency of German troops.’

As 1917 drew to a close, the military situation for the Allies was grim. With his forces battered, Haig faced a challenge to his military authority and the French were engaged in rebuilding their military strength, all while German forces gathered for a climactic offensive on the Western Front. Only the arrival of the Americans could once again redress the strategic balance.

When war swept across the European continent in 1914, the United States remained neutral, dominated by isolationism and content to let the old world sort out its own problems. As the war progressed and worsened, though, American President Woodrow Wilson became more and more interested in mediating an end to the conflict, while powerful economic and military forces nudged the United States towards support of the Allies. While the British imposition of a naval blockade on Germany was met by the United States with strong protest and remained a source of consternation throughout the war, the effects of the blockade tied American business ever closer to the economic fates ofBritain and France. Cut off from trade with Germany, American exports to the Allied powers rose from 825 million dollars in 1917 to over three billion dollars in 1916, and by 1917, the Allied nations had borrowed over two billion dollars from American financial firms.

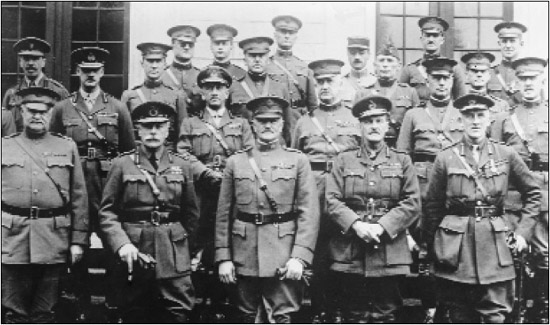

General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing (centre) with Douglas Haig to his right and their respective staffs. Pershing was insistent on keeping the AEF a separate entity, and relations with his French and British allies were often fraught.

Unhappy with America’s Allied-friendly form of neutrality, and smarting from British propaganda aimed at the United States that luridly portrayed German atrocities in occupied Belgium, the German Government decided to blockade Britain in turn through use of the submarine. Where the British blockade of Germany relied on surface ships that could intercept and seize suspect merchant vessels, German U-boats, which relied on stealth, enforced their blockade by sinking merchant vessels. On 7 May 1915, U20 torpedoed the Cunard liner Lusitania with the loss of 1198 lives, including 128 Americans. Fearing that continued sinkings could cause a rupture with the United States, the Germans eschewed further attacks on merchant shipping until spring 1916, when U29 torpedoed the French passenger steamer Sussex, injuring several Americans. Bowing to public pressure, Wilson threatened to cut off diplomatic relations with Germany, which resulted in another cessation in the submarine war.

Although he still hoped to avoid open conflict with Germany, and ran as the peace candidate in the closely fought presidential election of 1916, Wilson did begin to take steps to prepare the United States for war. He signed into law the National Defense Act, which forecast increasing the strength of the US Army from 90,000 men to a force of over 200,000 and established a Council of National Defense to coordinate industry and resource allocation in the event of war. Wilson’s desire to play the role of peacemaker and hopes of remaining neutral, though, were dealt a grievous blow with the German announcement in February 1917 of the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. The situation became critical with the interception of the Zimmerman Telegram, which proposed a German military alliance with Mexico in the event of war with the United States.

Amid a climate of public revulsion against Germany in the wake of the Zimmerman Telegram, on 12 March the Algonquin became the first American merchant ship lost to the German U-boat offensive, and three more torpedoings quickly followed. By 20 March, Wilson’s cabinet agreed unanimously that the country had to enter the war on the side of the Allies and, on 2 April, Wilson went before Congress to request a declaration of war on Germany. In his speech, Wilson expressed a moralistic tone that would both make him one of the most important leaders of the world and set him in opposition to his future Allies. Wilson proclaimed that American participation in the war would help make the world ‘safe for democracy’ and went on to promise that:

‘… we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest to our hearts – for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Government, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world it self at last free.’

Although Congress debated the proposal for three days and neutralists spoke against American entry, there remained no hope for peace. On 6 April 1917, Congress approved Wilson’s request and the United States was at war.

Although American black soldiers fought for liberty and their nation, they found their segregated social standing little changed upon their return.

As America prepared for war, US industry required an influx of manpower, and black Americans answered the call. In what the Chicago Defender called the Great Northern Drive, between 350,000 and 500,000 blacks moved to the industrial cities of the north not only to escape segregation but also to take jobs where they could earn four times more than they had working as sharecroppers in the south. Not all northern cities, though, were accepting of the new migrants. When more than 10,000 black workers arrived in East St Louis, Illinois, angry whites accused them of stealing their jobs and of making the crime rate rise. On 1 July 1917 the tension boiled over as a mob of angry whites roamed the streets, clubbing down the blacks that were unlucky enough to cross their path, including women and children. The mob even seized a crippled black man and burned him alive. They then shot a black child and threw his body into a burning building. National Guardsmen, called out to halt the unrest, did little to stop the riots, which lasted for four days during which time more than 100 blacks died and more than half of the black population fled the city. As racial unrest throughout the nation grew, an African-American university professor, Kelly Miler, wrote to President Wilson about the role of black Americans in the war: ‘The Negro, Mr. President, in this emergency will stand by you and the nation. Will you and the nation stand by the Negro?’ Wilson never replied.

The Springfield rifle was the standard front-line weapon used by the US Army throughout World War I. It was actually a modified Mauser, which was first adopted in 1903 and remained in service until the Korean War. Its box magazine held five .30in rounds.

Initially it seemed that the Germans had been right not to fear the United States. The National Defense Act had yet to achieve its goals and, on 1 April, the US regular army consisted of only 5791 officers and 121,797 enlisted men. There were also 66,594 National Guardsmen under federal service, and 101,174 under state control. Broken in the main into smaller formations, there were as yet no coherent divisions in the US Army, which suffered from a severe and chronic shortage of weaponry and had no units of any kind that were ready for service in Europe. The army remained, in the earlier words of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, ‘a profoundly peaceful army’. Facing the gargantuan task of creating an armed force of millions almost from scratch, in MayWilson turned to General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing to command the nascent American Expeditionary Force. Pershing had seen service in the campaign in Cuba in 1898, and, as America had lurched toward war, was one of the few officers in the US Army to command forces in battle, having led the chase for Mexican bandit Pancho Villa in 1916.

Seeking to provide Pershing with the necessary raw materials for war, Wilson signed the Selective Service Act into law on 18 May. Learning from problems that had occurred in America’s only previous experience with conscription during the Civil War, the federal government left the draft in the hands of local civilian boards tasked with raising quotas of men from among ‘their friends and neighbors’. On 5 June, all men between 21 and 31 filled out draft registration cards that included all relevant personal information, plus any reasons why they should not be drafted. Then each candidate received a small green card bearing a number. On 20 July, Secretary of War Newton Baker donned a blindfold and reached into a jar full of tiny capsules, each of which contained a registration number. Surrounded by members of the press, Newton withdrew the first capsule with the number 258. The drawing went on until late the following morning to determine the selection of draft order to be transmitted to the local boards.

The German Government and high command were acutely aware that the declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 would bring the United States into World War I, and the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmerman, was determined to be ready for such an eventuality. On 19 January 1917, Zimmerman sent a telegram to Count von Bernstorff, the German ambassador in Washington DC, outlining a possible German-Mexican military alliance in which Mexico would attack and reconquer Texas, New Mexico and Arizona in the event of war with America. British intelligence, however, intercepted the telegram and, with a certain amount of glee, turned it over to President Wilson, who sought confirmation of the authenticity of the telegram and its alliance offer. Unbelievably, Zimmerman himself confirmed that the contents of the telegram were genuine, which Wilson had reprinted in several newspapers. Already stunned by the German submarine campaign, the American public saw the Zimmerman Telegram as tantamount to a declaration of war – and demanded an American response. With strong isolationist tendencies and a large German minority, entering World War I on the side of the Allies was at best a difficult prospect in the United States, but one made into a near certainty by the Zimmerman Telegram.

Although the war was fought for the domination of a distant continent, Americans answered the call to conflict in unprecedented numbers, eventually raising a military force of over three million and tipping the balance of the war. Many suffered chronic seasickness on the journey to France.

Across the nation, stars and celebrities turned out to speak at rallies and urged all citizens to play their part in the war. In New York City, famed evangelist Billy Sunday made impassioned pleas for God to ‘strike down in his tracks’ any man who did not register for the draft. ‘If hell could be turned upside down,’ he screamed, ‘you would find stamped on its bottom, “Made in Germany!”‘ Sunday, though, need not have worried, for Americans, like their European brethren before them, rushed to the colours in a patriotic fervour. Even so, as a late comer to the war, the United States’ level of manpower commitment to the war never compared to that of its European allies. By the end of the war, 24,234,021 American men had registered for the draft, and a total of 3,099,000 served in the military, or roughly three per cent of the population. In contrast during the war France called up 7,800,000 men, or one-fifth of the total population, while in Britain 5,704,416, or 10 per cent of the population, served.

With millions willing to serve, though, the United States had to create an infrastructure capable of housing, training, arming and commanding its massive new military. Shortages of everything from clothing to weaponry were severe; in 1917 the US military only possessed 400 light field guns, 150 heavy artillery pieces and 1500 machine guns. The government quickly constructed 16 training camps, often staffed with instructors borrowed from the French or British military. Due to a critical shortage of trained officers, the military also created a variety of additional training programmes. Perhaps the most difficult challenge, though, was the conversion of American industry away from its chaotic and often cutthroat peacetime policies to controlled wartime production. In an effort to take control of the situation, the Council of National Defense created the War Industries Board, which eventually took control of all aspects of industrial production.

To the war-weary French, the arrival of American forces, no matter how ill trained, was a tonic, and resulted in spontaneous celebrations as American units marched through towns on the way to their training bases. British civilians also experienced a similar boost in morale.

Although America was the mightiest industrial nation on the planet, it had come to the war too late fully to realize its massive potential power. While the United States provided mountains of raw materials, including iron and copper, the millions of American soldiers who served in Europe in the main utilized weaponry produced in Britain and France. Most Americans reached Europe aboard British or French ships, and were transported to the front in French trains or on French or British trucks. As an example of America’s dependency in the area of military hardware, of the 3499 artillery pieces used in battle by the AEF, only 130 were American made. While US forces expended an estimated 8,116,000 artillery rounds in battle, only 8400 were American made.

As in the case of this US infantry unit, most American formations arrived in France with only rudimentary training and had to spend considerable time under the tutelage of a British or French training cadre.

In 1917, though, the gathering of America’s military might had only just begun, and projections of the numbers of troops that the United States would eventually send to France were cold comfort to the battered Allies. The crisis was fast approaching as German troops poured westwards from conquered Russia. Petain spoke for many when, upon meeting Pershing for the first time, he remarked concerning American entry into the conflict simply, ‘I hope it is not too late.’ Many British and French leaders agreed with Petain’s assessment, for even the most optimistic projections forecast that the AEF would not be able to play a meaningful role in the war until mid to late 1918, while more gloomy prognostications focused on 1919 or even 1920. The Germans, though, were going to attack at the earliest opportunity in 1918, potentially achieving victory while the AEF was in its training camps or in troopships at sea.

‘They looked larger than ordinary men; their tall, straight figures were in vivid contrast to the under-sized armies of pale recruits to which we had grown accustomed. … They seemed, as it were, Tommies in heaven.’

Vera Brittain on American soldiers, from Testament of Youth

Facing the prospect of their imminent destruction, the heavily taxed British and French understandably made it their top priority to ensure that American troops reached the Western Front as quickly as possible. Upon the American declaration of war, both Britain and France sent high-level political and military delegations to the United States. Fearing that it would take too long to raise, train and equip an independent AEF, both Allies proposed that the US send to Europe 500,000 to one million untrained men, who would then receive training and join already established British or French units. The European Allies hoped that through such an arrangement, dubbed amalgamation, American soldiers could have a more immediate impact on the outcome of the war. When the remainder of the AEF was finally ready for battle it could then reabsorb the amalgamated soldiers, who would in turn form the battle-hardened core of an otherwise untested military. The British even went one step further and requested permission to recruit soldiers in the United States for service in the British military.

After the American entry into World War I, the Committee on Public Information wasted little time in producing propaganda posters and literature designed to heighten public feeling against both German militarism and the ‘Hun’.

As part of the patriotic war effort, then, Americans tried to rid their nation of nearly everything German. Americans no longer ate frankfurters or kept dachshunds as pets, instead they ate Liberty Sausages and cared for Liberty Dogs. All over the nation, schools stopped teaching German, and by 1918, almost half of the states had laws restricting the use of the German language or banning it altogether. Americans also questioned the loyalty of the eight million German-Americans in their midst, often accusing those of German ancestry with defeatism or of espionage. Mobs often took the law into their own hands, forcing their German-American neighbours to kiss the American flag or curse the German Kaiser to prove their allegiance. In the most extreme reported case, Robert Prager, a German-American who had been rejected for military service due to bad eyesight, was abducted by a mob and accused of spying. The mob, driven by drunkenness, wrapped Prager in the American flag and forced him to sing patriotic songs. Tiring of their sport, the members of the mob finally tied a rope around Prager’s neck and hanged him from the nearest tree. Prager’s last wish was to be buried in the flag of his adopted nation.

The Browning automatic rifle. Designed in response to the need for an American assault rifle on the Western Front, the Browning could fire 550 rounds per minute. The Browning only entered service on the Western Front in late 1918, too late to have a meaningful impact on the fighting.

On the advice of his cabinet, Wilson flatly rejected the amalgamation schemes. Military men, including Pershing, believed that American troops should not be placed under foreign commanders, while Wilson hoped that an independent AEF would give the United States a much stronger bargaining position at a postwar peace conference. Major-General Tasker Bliss summarized American fears in a letter to Secretary of War Newton Baker:

‘When the war is over it may be a literal fact that the American flag will not have appeared anywhere on the line because our organizations will simply be part of battalions and regiments of the Entente Allies. We might have a million men there and no American army and no American commander. Speaking frankly, I have received the impression from the English and French officers that such is their deliberate desire. I do not believe our people will stand for it.’

Wilson, who favoured a less recriminatory ‘peace without victory’, looked on the war aims of Britain and France with distaste. Believing that both the Allies and Germany had been blinded by years of war, Wilson held the United States diplomatically aloof from the goals of the belligerents, even referring to Britain, France, Italy and Japan only as ‘associated powers’ in an attempt to solidify both America’s freedom of action and power in any peace settlement. In line with his thinking, Wilson gave Pershing his final instructions before sending him off to France:

With the Allies’ knowledge that the Germans were readying for an all-out attempt to achieve victory on the Western Front in 1918, training US personnel was a race against time in an effort to have American forces reach the front lines before it was too late.

‘In military operations against the Imperial German Government you are directed to co-operate with the forces of the other countries employed against the enemy; but in so doing the underlying idea must be kept in view that the forces of the United States are separate and distinct components of the combined forces, the identity of which must be preserved. This fundamental rule is subject to such minor exceptions as particular circumstances or your judgment may approve. The action is confided in you and you will exercise full discretion in determiningthe manner of co-operation.’

Denied their request for immediate aid, the French and British delegations asked that the Americans at least send a division, no matter how poorly trained, to France to show the flag and raise Allied morale. Assenting to the request, Pershing directed the dispatch of the American 1st Division. Supposedly a regular division, the 1st actually had been gutted of many of its most skilled soldiers to serve as instructors for other units, and had its ranks replenished by the addition of raw recruits. Henry Russell Miller, who served in the 1st Division, recalled, ‘Physically it was less impressive than any other outfit I have ever seen. In intelligence it was probably a little below the American average, in education certainly. ... Its manners were atrocious, its mode of speech appalling, its appetite enormous, its notions of why we were at war rudimentary.’

When the German hammer blows fell in 1918, US units were not yet in the line in any great numbers. However, before the tipping point was reached, fresh and fit American units reached the front, much to the chagrin of understrength and spent German formations.

Partly trained and wearing ill fitting new uniforms, the 1st Division landed in France at the port of St Nazaire on 26 June 1917 to a joyous greeting and disembarked singing:

Good-bye Maw! Good-bye Pa!

Good-bye mule with yer old hee-haw. ...

I’ll bring you a Turk an’ a Kaiser too,

And that’s about all one feller can do. ...

On 4 July, the 1st Division paraded through the streets of Paris. Besieged by a joyous crowd, Pershing wrote, ‘With wreaths around their necks and bouquets in their hats and rifles, the column looked like a moving flower garden.’ Amid the turmoil a few of the French observers noticed that their saviours seemed to be military amateurs, with one bystander remarking, ‘If this is what we may expect from America, the war is lost.’ As if in agreement with the judgement, on 10 July the 1st Division entered a training area near Condrecourt-le-Chateau, and would not see battle for nearly a year.

In the wake of the 1st Division’s arrival in France, millions of American soldiers completed their initial training in the United States and then made their own way across the Atlantic. For many of the Doughboys, few of whom had ever been aboard a ship, the journey was agonizing. Sergeant Ira Redlinger recalled that on board his troopship, during a particularly stormy crossing, that he and his compatriots got, ‘six meals a day – three down and three up’. Although conditions on the troopships were often appalling, it was much worse on ships carrying horses and mules. One sergeant recalled that his ship, carrying 1600 such animals, encountered bad weather:

‘The mountainous waves rolled us around like a ball. The horses in housings on the top deck were thrown all over the deck. . The screaming and yelling of the animals was pitiful. ... There were 250 dead animals lying around. We tossed them over the side. . When we arrived at Saint-Nazaire [and] started to unload our animals it was just a little more than some could take. They went down the gangplank onto the dock, let out a heehaw, and dropped dead.’

While American units entered France with agonizing slowness, the rush of military events prompted a renewed call for amalgamation from Britain and France. As Haig had predicted after Cambrai, the balance of forces on the Western Front started to shift as the Germans rushed troops westwards in ever growing numbers, while Britain and France both suffered from severe manpower shortages and their American saviours languished in training camps awaiting the formation of an independent AEF. In December 1917, both Lloyd George and Petain suggested placing intact American formations, a policy termed ‘brigading’, within British and French divisions so that American manpower could be rushed into the front lines. Given the desperate nature of the situation, Secretary of War Baker gave the idea his grudging support. Even prominent figures within the US military, including General Tasker Bliss, contended that American units should enter the line under British or French control to help stem the expected German assault.

Even while their units were training, American forces often sent their military bands to show the flag in an effort to raise sagging Allied morale. For the majority, it was their first experience of Europe.

Although the United States was only in World War I for a short time, its unfettered economic power, which included the use of female factory workers, presaged America’s position as the ‘arsenal of democracy” in World War II.

Pershing, though, remained adamant that American troops would only enter battle together in an independent command with its own section of the front lines. Although the renewed struggle over amalgamation became very confused, and involved bickering in the very highest level of Allied command in the newly formed Supreme War Council, by February 1918 Pershing agreed to the ‘six division plan’, which called for six American divisions to locate with and be trained by the British. Even though the furore over the issue of amalgamation had calmed, when the German attack fell on Allied lines in March, American units had not yet taken their places in the front lines.

As in most nations involved in World War I, the United States had to make use of new sources of labour to offset the loss of men to the armed forces. In America, the new sources of labour included both African-Americans and women. One African-American woman, who had previously been a domestic servant, said of her experience working in a railyard during the war:

‘All the colored women like this work and want to keep it. We are making more money at this than any work we can get, and we do not have to work as hard as housework, which requires us to be on duty from six o’clock in the morning until nine or ten at night, which is mighty little time off and at very poor wages. ... What the colored women need is an opportunity to make money. As it is, they have to take what employment they can get, live in old tumbled down houses or resort to street walking, and I think a woman ought to think more of her blood than to do that. What occupation is open to us where we can make really good wages? We are not employed as clerks, we cannot all be school teachers, and so we cannot see any use in working our parents to death to get educated. Of course we should like easier work if it were opened to us. With three dollars a day, we can buy bonds … we can dress decently, and not be tempted to find our living on the streets’

One reason that Pershing had resisted amalgamation until it was almost too late is that the American commander believed that the British and French had been fighting the war incorrectly and that American training and tactical dogma were superior. Although there were arguments within the US military, Pershing decided that the French and British relied too heavily on overwhelming artillery firepower and techniques of trench warfare. American drill regulations contended that regarding trench warfare, ‘any officer . could get in a hole in the ground and take care of the situation at hand’. Instead, Pershing insisted that the American training regimen concentrate on open warfare, arguing that, ‘victory could not be won by the costly process of attrition, but must be won by driving the enemy out into the open and engaging him in a war of movement’. The British and French, through a brutal process of trial and error, had learned the difficult lesson that attacks on the Western Front required painstaking preparation and even then had only a limited life span. Rejecting much of the strategic experience of their Allies as flawed, the Americans relied on a policy of attempting to achieve a clean breakthrough of the German lines, which doomed American soldiers to suffer through their own Battle of the Somme.