German troops dash forwards during the Spring Offensives of 1918, a desperate gamble by the German high command to win World War I before the arrival of substantial American forces tipped the balance of the conflict.

Having won the war in the east, Hindenburg and Ludendorff gambled everything on a final chance for victory in the west. Utilizing novel tactics, the Germans won a series of victories, but a lack of strategic coordination and a staunch Allied defence doomed the plan to failure. Instead of winning the war, Ludendorff had exhausted the German Army.

The strategic situation for Germany in early 1918 looked more promising than it had since the outbreak of the war. Russia, riven by revolution and civil war, was out of the conflict, as was Romania. Italy had been soundly defeated at Caporetto, while both Britain and France were mired in manpower difficulties and plainly on the defensive. The United States, which in the words of one member of the German general staff could ‘yet be able to turn the page of history’, was slow in bringing its power to bear. With the initiative again on their side, German forces gathered from around Europe to launch a bid for victory on the Western Front.

While Germany demonstrated a high level oftactical planning and prowess during the Spring Offensives, the strategic goal of the offensives remained fatallymuddled, leading to ad hoc alterations of the plan to fit circumstances on the ground and no clear set of final goals.

The window of strategic opportunity for Germany was, though, quite narrow, for the strain of a lengthy multi-front war of attrition had already begun to show on the home front. In the summer of 1917, the authorities had quashed a budding mutiny among German sailors at Wilhelmshaven, while in the winter of the same year, politics in Germany neared a breakdown with the socialist parties, who advocated peace without annexation, squaring off against parties of the right, who demanded a punitive peace. Political and social unrest came to a head in January, when a wave of strikes swept across the nation in which hundreds of thousands of workers demanded peace and more food. Although the wave of strikes subsided, the turmoil remained just below the surface, and differences were only momentarily put aside in the expectation of final and cathartic victory in the west. German politician Kurt Riezler commented, ‘All depends on the offensive - should it succeed completely, then we will have the military dictatorship that the public will cheerily put up with - should it not succeed [then there will come] a severe moral crisis which probably none of the present government leaders has the talent to master peacefully.’

Both Hindenburg and Ludendorff not only understood the vulnerable condition of the German home front but also were aware of the more closely guarded secret of the frailty of the German military. In late 1917, war-related industries had been thoroughly combed to make up for manpower losses in the west and reserves were being called up at a rate of 58,000 trained and 21,000 untrained men per month. Even such complete measures, though, only covered the projected needs of the army in the west until January 1918. With the nation reaching the end of its manpower tether, many German commanders originally advocated standing on the defensive in 1918, a strategy that eventually would cede control of the war to the Americans. The final collapse of Russia had changed the situation, though, and allowed Ludendorff the option in his words ‘to deliver an annihilating blow to the British before American aid can become effective’.

Both militarily and socially, then, the German offensive of spring 1918 was a last roll of the dice. The great gamble, which first involved a logistical miracle of moving vast numbers of men and material from Russia to the Western Front, had to achieve victory before American forces arrived in such numbers as irrevocably to tip the balance of war against Germany. The German Army, though skilled and resilient, would never be able to match the Americans in numbers, and the German home front would not be able to stand further years of war. It was victory or defeat, all or nothing. In his planning, though, Ludendorff consigned the offensive to eventual defeat and sealed Germany’s doom in a fit of greed. The German general staff initially planned to shift 45 divisions from the Eastern Front to France and Flanders. Germany, though, had taken so much land from Russia in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, land that Russian revolutionary forces might try to retake, that Ludendorff only approved the removal of 33 divisions from the east. As German forces launched their climactic offensive in France, left behind in Russia were a total of 40 infantry and three cavalry divisions, a force that could have tipped the balance in the close-run and desperate battles of 1918.

Having made the decision to gamble on victory in the west, the only thing that remained was to decide on a place for the attack. Prince Rupprecht, supported by Hindenburg, suggested an attack near Ypres, while other commanders advocated their own pet projects, including a renewal of operations at Verdun. On 11 November 1917, Ludendorff called a staff conference to weigh the various options for the coming year, at which, after considerable discussion, he decided to attack the BEF, believing that they were more determined to fight than the French. If he could defeat the British - better yet drive them into the sea -Ludendorff believed that French morale would collapse. The question then became where to strike. Ludendorff preferred to attack in Flanders where German forces were within reach of the critical Channel ports. However, the tortured state of the ground and the continued bad weather in the region dissuaded him. Instead, Ludendorff chose to attack near the old Somme battlefield - at the vulnerable juncture between the British and French armies. The immensity of the decision was not lost on Colonel von Thayer of the general staff who commented, ‘Here in the west we stand before the future as a dark curtain. The coming events will bring tremendous and for many horrible things.’

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, on an inspection tour. Having lost a large measure of control over his nation to the military during the war, the Kaiser was optimistic that the Spring Offensives would set things to right.

The experiences of Verdun, the Somme and Passchendaele would seem to indicate that Ludendorff’s hope that a climactic battle could drive the British into defeat was foolhardy at best. However, German experiences in their own victorious offensives on the Eastern Front, as well as lessons learned by suffering through the Allied attacks in the west, indicated that technological advancements had redressed the balance of warfare and once again allowed hope for attacking forces to achieve a breakthrough.

Senior German officers watch machine-gun training. The German high command hoped that the combination of training with new weaponry and advanced infiltration tactics would tip the tactical balance of the war in its favour.

In the great battles of the first phase of the conflict, infantry had been nearly helpless in the face of intact barbed wire and entrenched enemy forces. However, by 1918 the foot soldier was once again a force with which to be reckoned. Carrying an array of portable firepower that included light machine guns, grenades and mortars, in 1918 infantrymen could deal with an enemy strongpoint or machine-gun nest on their own, rather than have their forward momentum stop while awaiting artillery assistance. By the close of the conflict, the infantry also carried more exotic weaponry, such as flame-throwers and Bangalore torpedoes, which aided in overthrowing enemy trench systems. Newly powerful, and once again capable of manoeuvre in battle, the infantry, after three years of relative impotence, finally was ready to reassume a major role on the battlefield.

During the great trench battles of 1915-17, attacking forces had come to rely almost exclusively on the flawed power of artillery in their efforts to achieve victory. Lacking either effective infantry or a weapon of exploitation, attackers had asked the artillery to carry the entire weight of battle. In such fatally tactically imbalanced battles, the artillery first had to flatten the enemy’s first line of defence, the deadly entanglements of barbed wire. Next the artillery had to destroy the entirety of the enemy’s intricate trench system and silence his deadly machine guns, all while providing cover for advancing infantry. Last but certainly not least, the artillery had to destroy the enemy artillery that stood ready to rain death upon attacking infantry in no man’s land. The reliance on artillery had been too heavy, and the tasks assigned it were too varied and difficult, contributing to the continuing dominance of the defensive during World War I.

In the battles of 1918, though, the artillery was called upon to do much less, thus restoring the balance of warfare. Given the renewed strength of the infantry, the artillery no longer had to destroy everything in the path of the foot soldiers and defeat the enemy single-handed; now it only had to keep the defenders’ heads down until the newly powerful infantry arrived at his trenches. Without the need for prolonged preparatory artillery barrages, surprise was also once again a factor in strategic and tactical thinking. Finally, improved technology and communications made the artillery much more lethal in its remaining tasks, including counterbattery fire. For the first time since the heady days of 1914, infantry and artillery could work seamlessly together, aided even by close cooperation with air forces, in a fluid battlefield situation instead of relying on brute force and overly choreographed fire plans. The war had changed and entered a new phase in which it seemed that technology had once again tipped the balance of warfare in favour of the attacker.

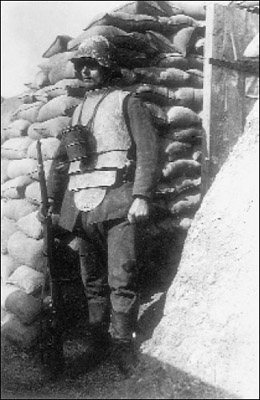

The Western Front, even during its rare moments of calm, remained a deadly place, as evidenced by this German soldier wearing rudimentary body armour as protection against shrapnel. Known as Sappenpanzer (trench armour), over half a million suits of this body armour were produced.

The Germans are often credited with being the first to experiment with updated tactics that made use of the strength of the war’s new technological developments. In reality, though, all sides were busy developing more modern methods of attack throughout the conflict, with the British effort at Cambrai utilizing predicted fire and massed formations of tanks, and Russian tactics in the Brusilov Offensive, standing out as examples of Allied innovation. It was, however, in the German Spring Offensives of 1918 that the new offensive tactics both gained fame and were used together in a truly systematic way.

German soldiers training for the Spring Offensives near Sedan. With so much riding on the outcome of the Spring Offensives, the German high command left little to chance, ensuring the training of German stormtroop units to a fever pitch of readiness.

Like the Allies, the Germans had been experimenting with tactics since their Pionier (combat engineer) units first had utilized grenades to destroy enemy fortifications. In early 1915 the first Sturmabteilung (storm detachment) had been formed, which utilized firepower and manoeuvre to deal with enemy strongpoints, rather than weight of artillery. While playing only a small role in the battles of 1916, stormtroop tactics gained wider relevancy in 1917. In the Battle of Riga on the Eastern Front, the German Eighth Army, under the command of General Oskar von Hutier, in combination with the advanced Feurwaltz (creeping barrage) tactics developed by artillery innovator Lieutenant-Colonel Georg Bruchmuller, won a stunning victory. Similar tactical innovations were on display at the successful attack at Caporetto in Italy and the counterattack at Cambrai. As is so often the case in warfare, the important tactical innovations had originated at lower levels of command as talented individuals came to grips with the realities of their war. By November 1917, as planning for the Spring Offensives got underway, Ludendorff assigned Captain Hermann Geyer to study the tactical ferment that had been taking place on all fronts in the German military. In January 1918 Geyer presented Ludendorff with a paper entitled Der Angriff im Stellungskrieg (The Attack in Position Warfare), which guided German planning for the remainder of the war.

The new tactics called for German infantry units not to attack across the front en masse, but instead to strike in small, mobile formations that first sought out weak points in the enemy line. Having located vulnerable positions, the infantry was directed to infiltrate Allied lines, avoiding centres of resistance, and to penetrate ‘quickly and deeply’ into the enemy’s rear. Infantry units were not to be concerned about whether other units on their flanks advanced in concert or to halt for any reason; the attackers had to press on to depth regardless of the situation. Fresh reserves, held near the front, would then leapfrog through the advanced units to maintain the tempo of the advance. The artillery would lay down quick and accurate barrages, designed only to keep the enemy pinned in place. The key to success was the tactical suppleness and uninterrupted forwards movement of the infantry, which was instructed that the, ‘surprised adversary should not be allowed to regain consciousness’. Such tactics, it was hoped, would shock and dislocate the enemy defensive system. It was a far cry from the waves of advancing infantry often utilized in the great battles of 1916. Using their newfound firepower, infantry would probe and advance quickly, avoiding the strongest points and leaving them for mopping up at a later, more convenient time. The Germans were, in effect, planning to use blitzkrieg without tanks.

Geyer realized, though, that the German Army had suffered greatly in recent years, and estimated that only roughly 30 per cent of all soldiers, those between 25 and 35 years of age, were suitable for the rigours of a mobile battle. As a result, Ludendorff divided the units for the coming offensive into three categories: 44 ‘mobile’ divisions received the most training and the best weapons and were to be used in the van, 30 ‘attack’ divisions received similar equipment and were slated for use as first-line replacement units, while more than a hundred ‘trench’ divisions were stripped of their best officers, men and equipment and were intended for only defensive purposes. Ludendorff, though, was certain that training and tactical proficiency would more than outweigh any potential weakness of numbers, and contended later in his memoirs:

‘It was necessary to create anew a thorough understanding of the extent of front to be allotted in attack and to emphasize the principle that men must do the work not with their bodies alone, but with their weapons. The fighting-line must be kept thin, but must constantly be fed from behind. As in the defence, it was necessary in the attack to adopt loose formations and work out infantry group tactics clearly. We must not copy the enemy’s mass tactics, which offer advantages only in the case of untrained troops.’

To gain the proposed level of tactical mastery required to undertake the Spring Offensives, the German Army trained at a fever pitch throughout the winter of 1917-18. Ludendorff ordered each of his armies to establish schools to teach the elements of Geyer’s new doctrine to the officers and men of the mobile and attack divisions. The courses, which lasted four weeks each, stressed rigid discipline and physical exercise, but were mainly concerned with combined-arms operations. Geyer’s planning and stormtroop theory stressed that the various arms of the German military - infantry, intelligence, communications, air assets and artillery - all had to work seamlessly both to seize and then maintain the initiative in battle.

A German stormtrooper, wearing armour protection, at the time ofOperation Michael. This soldier is armed with classic trench-fighting tools, a Mauser Model 14 pistol and two hand grenades, as well as a sharpened entrenching tool.

The German planning for the coming offensive seemingly left nothing to chance. Machine-gun crews learned that the fine dust in the area of the advance could cause their barrels to malfunction and received special cleaning instructions to keep their weapons in working order. A small army of 4000 cartographers laboured to map British defences down to the last machine-gun nest. Communications specialists trained both dogs and pigeons to transport messages from the advancing troops. Amid the care for detail, though, one pivotal factor was lacking. Ludendorff, by his own design, did not engage in any operational or strategic planning. He was concentrating his energy, and that of the German military, on the tactics of how to achieve a breakthrough. Inexplicably there was no planning for what the goals of the German Army should be after a breakthrough occurred, or regarding a fail-safe plan for a scenario in which a breakthrough failed to occur. Ludendorff cut short those commanders who questioned the lack of an operational or strategic goal, stating, ‘I object to the word “operation”. We will punch a hole into [their line]. For the rest we shall see. We also did it this way in Russia!’

German soldiers at Bapaume. After so many years of fighting on the defensive on the Western Front, the morale of the German infantrymen soared when Germany once more went on the offensive in 1918.

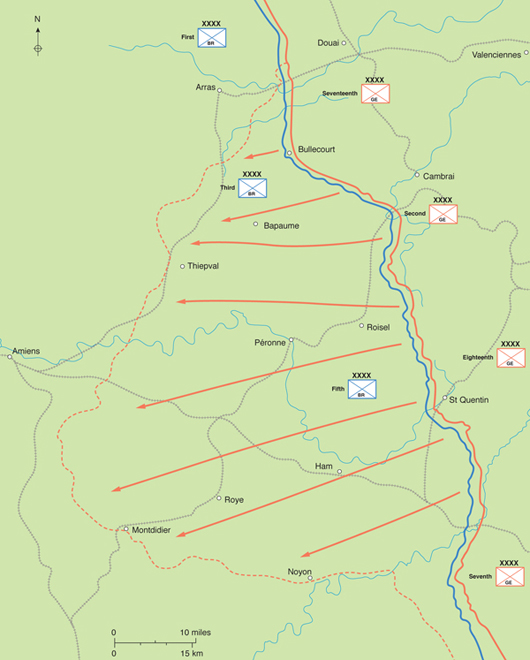

In substituting tactical mastery for strategic thought, Ludendorff had committed a fatal error. His overall plan, though it made use of revolutionary techniques, had no overall goal. To undertake the final offensive, dubbed Operation Michael in honour of the patron saint of Germany, Ludendorff gathered his most successful and innovative commanders. The plan called for the Seventeenth Army, under the architect of the victory at Caporetto, General Otto von Below, to attack towards Bapaume. The Second Army, under General Georg von der Marwitz who had led the German counterattack at Cambrai, was to strike southwest toward Albert, while the Eighteenth Army, under the victor of Riga, General von Hutier, attacked from St Quentin. On the right and left flanks of the advance respectively, the German Sixth and Seventh armies stood in readiness to launch subsidiary operations, dubbed Mars and Archangel, to build on the expected successes of Michael.

German troops carry their machine guns forwards into new positions during the Spring Offensives. Increased infantry firepower was critical to the successful implementation of Germany’s new infiltration tactics.

If all went well, the German Eighteenth, Second and Seventeenth armies would rupture the front of the British Fifth and Third armies, severing the vital connection between the British and French forces on the Western Front. In the process, Ludendorff hoped that his attacking armies would first pin and destroy substantial British forces in the Cambrai Salient and then follow the Somme River northwest and drive the British towards the sea. The brunt of the offensive would fall to Below’s Seventeenth Army, which as a result received the lion’s share of supplies and reserves. Depending on where success was the greatest, additional German attacks would then fall in the north and destroy the vulnerable British position in Flanders, or in the south against the French Army Group North. The follow-on attacks would thus rupture the entire Allied line, and lead to ultimate victory.

The overall balance of strength on the Western Front seemed to bode well for the Germans, who had gathered 192 divisions against only 178 Allied divisions. However, the number, which included many seriously understrength divisions, represented a peak for the Germans, while the Allies could count on a swelling of their ranks as more and more Americans reached France. As regards the machinery of war, the Germans were also at a growing disadvantage: the Germans had 3670 aircraft against 4500 Allied, 14,000 artillery pieces against 18,500 Allied and 10 tanks against 800 Allied. More disturbing, though, was the fact that so few of the German divisions, only 77 in total, were trained in the new style of warfare. These mobile and attack divisions, the shock forces of the German army, were irreplaceable and as such had to achieve victory quickly. Their superior tactics had to offset all of the other Allied advantages. Germany could not afford a battle that dragged on or became attritional in nature, lest the stormtroops themselves and the German hope for final victory be destroyed.

A captured British artillery piece in 1918. After suffering privations due in large measure to the blockade, advancing German troops were shocked to discover how lavishly supplied the BEF was in terms of both food and munitions.

Ludendorff’s three-stage plan for Operation Michael, which called for the Eighteenth, Second and Seventeenth armies to rupture the British lines through an assault on the British Fifth Army (1 and 3), before turning north through Third Army and then driving the BEF into the sea (2).

While the Germans prepared for their assault, the Allies had to ready themselves for a defensive battle, having lost the initiative in the west for the first time since the onset of trench warfare. Although the situation on the Allied home fronts was not as bad as that of Germany, political tension in both France and Britain during the winter of 1917-18 rose to a fever pitch. Their military efforts and nearly four years of war had seemingly availed nothing, for despite the investment of blood and treasure Germany seemed ascendant as all awaited the onset of the coming onslaught. Blame for the sorry situation was abundant: the military leadership had mishandled the great battles of the war, politicians had meddled in strategy too often, the Allies did not act together effectively as one and the Americans had not agreed to amalgamation. Recriminations abounded, testing the very fabric of the alliance at a crucial time.

Although their relationship was often strained and involved tumultuous debates over strategy, Pétain as commander-in-chief and Foch as chief of staff had together worked miracles in revitalizing the French military after the mutinies of 1917. Utilizing a mix of discipline and reform, Pétain had stabilized the situation to the extent that in June and July 1917, the Fourth, Sixth and Tenth armies, which were among the most affected by the mutinies, were able to launch limited offensives intended to draw German reserves away from the British operations at Messines and Ypres. Although further French offensives in support of Third Ypres both came later than promised and fell short of Haig’s expectations, for the remainder of 1917 Pétain’s armies fought well and regained their confidence. Adhering to the concept of the limited advance, and covered by overwhelming firepower, the French in August 1917 launched a successful attack at Verdun. Most importantly, though constant delays in its onset frustrated Haig, in October 1917, the Sixth Army achieved a cathartic victory by seizing the heights of the Chemin des Dames in a model limited offensive, suffering only one tenth of the casualties that Nivelle’s forces had lost in their failed attempts to conquer the same objective only five months previously.

A captain of the Royal Flying Corps in France. While reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance remained a primary role of air forces in 1918, utilizing aircraft in a ground-attack role gained prominence as the year progressed.

Although improvements within the French military were heartening for the Allies, nothing could offset the grim strategic reality that the balance of forces on the Western Front had shifted in favour of Germany. The prospect of facing a renewed German assault in the west was so dire that it finally drove the reluctant British and French toward a more unified command. As early as August 1917, Painlevé had suggested to Lloyd George that Foch be named chief of an Allied general staff, but the British Prime Minister had refused. However, in the wake of Passchendaele, Lloyd George once again decided to seize control over the strategic leadership of the conflict and moved to shift British power away from France and Flanders to other, hopefully more profitable, theatres of war. Realizing that the alliance formed by Haig and Robertson remained powerful, and that any overt move to oust them would endanger his government, Lloyd George chose indirect methods of achieving his goals.

In response to the devastating Italian defeat at Caporetto, in November 1917 the Allies met at the Rapallo Conference, where Lloyd George proposed the formation of a Supreme War Council to coordinate Allied efforts and guide a united strategy. Although the new advisory body, which met at Versailles, had little real power, it was the first, halting step toward a unified command. For his part, though, Lloyd George saw the Supreme War Council as a way to wrest control of the war from Haig and Robertson. By appointing his military ally, General Sir Henry Wilson, to Versailles, Lloyd George effectively had two sets of military opinion from which to choose. He, thus, hoped never again to pit his amateur strategy against a monolithic military bloc.

The shift in command, however, did little to calm the political turmoil in France, and only a week after Rapallo, the French Government fell. The situation was so dire that the British ambassador had even reported that a civil war in France was possible. As Pétain had done for the army, France needed a strong leader to heal its gaping political wounds. For the difficult position, President Poincaré chose Georges Clemenceau, known as ‘the Tiger’. Fiery and imbued with an indomitable will, Clemenceau proved an inspired choice who immediately clamped down on dissent, declaring, ‘Neither personal considerations, nor political passions will turn us from our duty. ... No more pacifist campaigns, no more German intrigues. Neither treason, nor half treason. War. Nothing but war.’ The new French leader soon discovered that he had a kindred spirit in General Ferdinand Foch, who was a hard-charging optimist, as opposed to Pétain, who was becoming increasingly pessimistic about the outcome of the war.

Scottish prisoners taken at Bapaume during Operation Michael. With its troops concentrated too far forwards, owing to a failure to construct an adequate defence in depth, Gough’s Fifth Army lost a disproportionate number of the 90,000 prisoners taken during the initial German attack.

In Britain, a growing manpower crisis added another level of intrigue to the ongoing civil-military struggle for control of the war. With his reserves depleted, and facing an unprecedented German build up, Haig requested 600,000 new men to keep the British armies overseas up to their recommended establishments. Lloyd George was livid, for compliance with the request would have crippled the very British industrial efforts that made the war possible. In December 1917, the Prime Minister had made his frustration with Haig clear in a letter to Lord Esher: ‘Now he [Haig] wrote of fresh offensives, and asked for men. He would get neither. He had eaten his cake, in spite of warnings. Pétain had economized his.’ Seizing upon control over manpower as another weapon to use in his conflict with Haig, Lloyd George approved only 100,000 new men for the military, placing the armed forces behind both shipping and agriculture in importance. The Prime Minister was playing a dangerous game, hoping to curb Haig’s ability to prosecute offensive warfare by denying the military needed manpower in a time of impending crisis.

‘We must strike at the earliest moment before the Americans can throw strong forces into the scale. We must beat the British.’

Erich Ludendorff on the Spring Offensives

Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, who was a close military confidant of David Lloyd George, rose to prominence as Chief of the Imperial General Staff in February 1918, replacing Sir William Robertson. Wilson was later shot and killed by the IRA in London in 1922.

Matters came to a head at the 30 January meeting of the Supreme War Council, which focused its attention both on easing the manpower situation and forming an Allied general reserve. Although both Haig and Pétain contended that they did not have any available forces to spare for the formation of a reserve, the idea was accepted in principle with the details to be decided at a later date. In the charged political atmosphere, though, what concerned Haig, Robertson and Pétain most was the decision to place control of the general reserve under the Supreme War Council, an arrangement that strengthened the hands of both Foch and Lloyd George. In frustration over his loss of power, Robertson resigned as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and was replaced in that position by Wilson. Lloyd George would never again have to face the united opinion of Haig and Robertson in strategic debates. One of the great personal alliances in British military history had come to an end.

General Sir Hubert Gough. One of the most controversial British military figures of World War I, Gough presided over the failed first attacks in the Third Battle of Ypres and the failed defence in depth against Operation Michael. Gough’s failure led to his replacement by Sir Henry Rawlinson.

Ironically, since Lloyd George and Wilson had achieved their main aim of removing Robertson from power, their support for the Supreme War Council and the issue of a general reserve waned. At the same time Haig continued to fret about manpower issues, writing in his diary on 10 March:

‘The manpower situation is most unsatisfactory ... with heavy fighting in prospect, and very few men coming in, the prospects are bad. We are told that we can only expect 18,000 drafts in April! We are all right under normal conditions for men for the next three months, but I fear for the autumn! And still more do I fear for the situation after the enemy has started the attack.’

Pétain, too, was worried that he did not have enough men to cover his own front, let alone contribute to the formation of a reserve. Instead of a formalized Allied reserve, both Pétain and Haig preferred to abide by an informal pledge to send their own reserves to the other’s aid in time of need. In the face of united Allied military opinion neither Lloyd George nor Clemenceau chose to press the issue, leaving Foch as its lone champion, and the idea of raising a general reserve was shelved until sufficient numbers of American troops had arrived in France to make a reserve practicable.

Although the Allies had taken a step toward true coalition warfare, the move had been more about political battles for control over the war than about Allied unity. The failure meant that the alliance remained not only fragmented but also at odds as it awaited the German attack. Wilson remarked regarding the situation that the failure to unify the Allied command meant that Haig, ‘would have to live on Pétain’s charity, [in case of an attack on the British lines] and he would find that very cold charity’.

While political dramas played out in London and Paris, Allied forces made ready to face the German attack. Haig correctly judged that the main weight of the German offensive would be directed against the BEF, but, misled by his own fears and German deception, he misjudged the axis of the German advance. Haig was most concerned by the prospect of a German attack in the neighbourhood of Ypres, where Allied forces had little strategic depth and any substantial retreat would place them in danger of catastrophic defeat. Haig realized that another vulnerable point was at the juncture of the British and French armies, but he reasoned that Gough’s Fifth Army, which defended the area, could, at need, give ground while awaiting the reserves that Pétain had promised before any German advance in the region threatened the nearest target of strategic value, the distant communications hub of Amiens. Weighing his tactical options, Haig distributed his available forces from north to south: Second Army with 14 divisions defended 37km (23 miles) of front, First Army with 16 divisions defended 53km (33 miles) of front, Third Army with 14 divisions defended 45km (28 miles) of front. The dispositions, though based on sound reasoning, left Gough’s Fifth Army with only 12 divisions to defend 68km (42 miles) of front. Haig’s decision had left the Fifth Army at a great disadvantage, and the official historian later remarked, ‘Never before had the British line been held with so few men and so few guns to the mile; and the reserves were wholly insufficient.’

Making matters worse, for years the BEF had practised offensive warfare, and was as a result a comparative novice at defensive battle. As it became clear in the winter of 1917-18 that the initiative had slipped to the Germans, the BEF slowly shifted its lines from an offensive posture to a defensive one. Based on the experiences of Third Ypres, Haig opted to install a system of defence in depth, which required massive amounts of labour in the creation of forward redoubt systems and battle zones within the British lines. The conversion of the trench systems into true defensive networks was painfully slow, in part due to a critical manpower shortage for labour battalions. Ominously, the situation was particularly bad on the front of Fifth Army, which had only recently taken over the area from French forces and found the defences there in a state of disrepair.

The BEF also had to alter its tactical defensive doctrine away from the practice of positioning large numbers of men in forward positions. The new defensive system called for using light forces, augmented by heavy firepower, in the forward positions and giving ground while drawing attacking forces into the battle zone where they would be destroyed. At a conference of his army commanders Haig explained:

As World War I dragged on, the armies of the Western Front consumed ever greater quantities of supplies, including these unfortunate local chickens on their way to a soldiers’ mess. Soldiers caught stealing could face stiff penalties, however.

‘Depth in defensive organization is of the first importance. . The economy of forces in the front line system is most important in order that as many men as possible may be available in reserve. The front line should generally be held as an outpost line covering the main line of resistance a few hundred yards in the rear.’

In many areas, especially that of the Fifth Army, neither the construction of defences nor the doctrinal shift was complete before the German attack. In addition to being severely outnumbered, Gough failed to understand the new defensive scheme, and played into the Germans’ hands by stationing too many of his men forwards. In a scene that was reminiscent of the command breakdown of Third Ypres, Haig warned Gough against lavish use of manpower and cautioned that Fifth Army would have to rely more on firepower and a sound defensive system. Haig even argued that it might be necessary to engage in a fighting withdrawal to the area of Peronne on the Somme while awaiting the promised French reserves to stall the German attack. The situation was bleak as Fifth Army, outmanned, occupying substandard defences, under a commander who did not fully understand his task and under a commander-in-chief who expected an attack elsewhere, made ready to face a new style of warfare. Even so, as the German offensive neared, Haig confided to his wife, ‘I must say I feel quite confident, and so do my troops. Personally, I feel in the words of 2nd Chronicles, XX Chap., that it is “God’s battle” and I am not dismayed by the numbers of the enemy.’

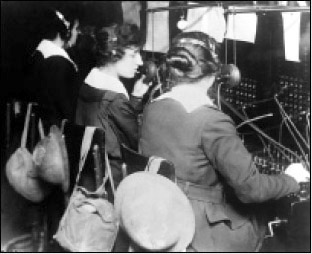

Instead of relying on Signal Corps’ members to man and operate the prodigious number of telephone switchboards needed to facilitate the communications needs of the AEF while in France, Pershing decided to import French-speaking American women as operators. Of the 7000 women who applied for the positions, 223 were chosen and received special training in their tasks at AT&T headquarters in Evanston, Illinois. Having to purchase their own uniforms, the operators earned a very respectable pay of 60 dollars per month. The women received first-class accommodation aboard troopships bound for France, but were forbidden to fraternize with the troops. Nellie Snow, formerly chief telephone operator for the New England Telephone Company, protested the ban, and the policy was abandoned. One of the operators wrote home:

‘There were some seven or eight thousand troops on board ...so you may imagine that the girls had a gay time ...we soon became acquainted with a number of officers who made the days pass pleasantly. All were obliged to wear life belts during the day, and it was an amusing sight to see couples trying to dance in them’

American women, known as ‘hello girls’, performed a vital communications role for the US military on the Western Front.

Once in France the operators served an invaluable function, and, because of their merry style of greeting, earned the name ‘hello girls’. After the war, though, the hello girls were surprised to learn that they had merely been employees of the military, and were not veterans and thus were unable to receive benefits. Not until 1979, after a lengthy campaign by former hello girl Louise Le Breton Maxwell, did the army belatedly admit its mistake, giving the few surviving hello girls honourable discharges and military benefits.

German soldiers steal some rest time while one oftheir number stands guard during the frenetic advance of the Spring Offensives. The unrelenting pace of the advance wore out the leading troops and ensured that momentum was lost, allowing the Allies valuable time to reinforce their lines.

The course of Operation Michael from 21 March to 4 April 1918. Changing his plan on the fly, Ludendorff, instead of pushing the BEF into the sea, opted for an ill fated attempt by Eighteenth Army to drive a wedge between the British and French armies.

The German MP 18, produced by Theodor Bergmann, was the first practical submachine gun of World War I, and was the prime weapon of the fast-moving German stormtroops. Designed for raiding and trench-clearing operations, its lightness and high rate of fire made it perfect for the task.

At 4.40am on 21 March, 43 German divisions moved to the attack, as 10,000 German guns and mortars opened fire on the fronts of the British Fifth and Third armies, announcing the beginning of Operation Michael. One German artillery officer remembered satisfaction at turning the tables on the Allies:

Within seconds of the bombardment opening, we could see sparks and columns of fire in the enemy trenches and their rear area. A terrific roar, an immense noise greeted the young morning. The unbearable tension eased. We were ourselves again and knew that it had come off all right. In the past the French and the tommies had bombarded us for seven days without pause; we would do it now in five hours. We laughed and looked happily at each other. Words were useless; the hell of the inferno outside saw to that. There was only lightning and noise.’

To the British soldiers on the receiving end of the fire, it seemed like the world was ending. Private E. Atkinson recalled:

‘Artillery was the great leveller. Nobody could stand more than three hours of sustained shelling before they start falling sleepy and numb. You’re hammered after three hours and you’re there for the picking when he comes over. It’s a bit like being under an anaesthetic; you can’t put a lot of resistance up. The first to be affected were the young ones who’d just come out. They would go to one of the older ones - older in service that is - and maybe even cuddle up to him and start crying. An old soldier could be a great comfort to a young one. On the other fronts that I had been on, there had been so much of our artillery that, whenever Jerry opened up like that, our artillery retaliated and gradually quietened him down but there was no retaliation this time. He had a free do at us. I think we were sacrificed.

German infantrymen on the assault between Arras and La Fere in March 1918. The men of the ‘mobile’ and ‘attack’ divisions of the German Army proved adept at exploiting the fluidity of the 1918 battlefield, but their numbers were extremely limited.

A mixed unit of French soldiers and a British Vickers machine-gun team preparing for defensive action near the Somme River. The shock of Operation Michael forced closer military relations between the often fractious French and British militaries.

‘Then a shell must have burst in our trench, but I don’t remember it. I woke up with just my head free, the rest of me was buried in sandbags and muck. I was completely stunned. I don’t know how long it was before this fellow from the Durhams pulled me out. My helmet and gas-mask had disappeared. I saw my corporal - his head was blown off- and the rest of the section must have been buried. I think it was being up on the fire-step as lookout that had saved me, but I found out later that I had been wounded by a bit of shell that had cut right through the muscle in my shoulder.’

The Feurwaltz, directed on the front of the Eighteenth Army by its originator Lieutenant-Colonel Georg Bruchmuller, kept the British in their defences until the German stormtroops, advancing through a thick mist, were upon them. Utilizing their new tactics, the Germans quickly penetrated the British forward zone almost everywhere, and made their way into the battle zone, leaving behind pockets of disoriented defenders for follow-on units to mop up. For most the men of Gough’s Fifth Army, German mobility and flanking tactics were a mystifying new experience. One British soldier of the 51st (Highland) Division recalled:

‘There were no dugouts in our front line; it was very thinly held to prevent casualties. We had to huddle up under the parapet during the shelling; there was no other shelter. When the bombardment lifted, we were not attacked frontally. We were considerably shaken by the shelling. It was a moment of fear. “What’s coming next out of the mist?” We fired our rifles blindly into the mist then heard firing from our left and from the rear. We realized that we were being out flanked. The men started to drift back until we were left with only two men, myself and a sergeant.

‘The next thing I knew was that two Germans were coming up the trench on our left; they were about ten yards away. The sergeant had been at the rum for some time. I cleared off; I wasn’t going to get caught. The last thing I saw of the sergeant he was shaking his fist at the Germans and using strong language. I saw him taken prisoner.’

In the north, facing the relatively strong defences of Byng’s Third Army, the German Seventeenth and Second armies, which were slated to play the major role in Operation Michael, fell well behind schedule and became entangled in bitter fighting in the British battle zone. To the south, though, Hutier’s Eighteenth Army broke through the battle zone of Fifth Army, causing Gough to order III Corps to retreat behind the Crozat Canal. By evening the situation for Fifth Army had become critical, with the defences in the south having been surrendered and having lost 500 guns and 38,000 casualties. However, the situation on the other side of the battlefront was also grim. The Germans had fallen well short of expectations, in most areas only advancing only halfway to their assigned goals. In the fighting more than 78,000 Germans had been wounded and killed, the highest single day total for the entire war - losses almost entirely suffered by irreplaceable stormtroop units.

German troops rush forward through destroyed Allied positions, searching for weak points in the Allied defensive lines. German troops sought to penetrate to depth and maintain the momentum of their advance, leaving bypassed strongpoint to be cleared by follow-on units.

On 22 March, Operation Michael continued, and in the north, Byng’s Third Army held in its defences, while to the south Fifth Army reeled under the German onslaught. XVIII and XIX corps fell back to match the earlier retreat of III Corps, which completely unhinged the Fifth Army’s defensive network and threatened Third Army’s flank. Against the crumbling defences, Hutier’s Eighteenth Army in places advanced over 19km (12 miles) in two days of fighting and tore a 80km (50-mile) gap through the Allied lines. In total the BEF had lost 200,000 casualties, 90,000 prisoners and 1300 artillery pieces. The victory, though, came at considerable cost for the Germans, with the Eighteenth Army alone losing 56,000 casualties.

Ecstatic, Kaiser Wilhem II ordered schools in Germany closed to mark the occasion and presented Hindenburg with the highest medal that Germany had to offer, the Iron Cross with golden rays, last awarded to Prince Blücher for actions against Napoleon. As Hutier and his staff toasted their good fortune with champagne provided by the royal family, the Kaiser dreamed of his glorious future as he celebrated with his closest confidants. He informed his entourage that, ‘if any English delegation came to sue for peace it must kneel before the German standard for it was a question here of a victory of the monarchy over democracy’.

German troops advance during Operation Michael. Long hours of training and careful coordination of efforts in the months preceeding Operation Michael, combined with the reorganization of the German divisional system, ensured that the initial asssaults of the campaign went smoothly.

Ludendorff, though, remained concerned that the Seventeenth Army, the lynchpin of his planning, had achieved relatively little against Byng’s forces. As a result, as Hutier’s men crossed the Crozat Canal on 23 March, Ludendorff made the decision to change his master plan on the fly. Instead of the Seventeenth and Second armies pushing the British into the sea, Ludendorff altered the axis of his advance to the front of the Eighteenth Army, which he now intended to drive a wedge between the British and French armies. In effect the Germans had taken a concentrated effort against the British and diluted it into a series of more limited offensives against both the British and increasingly the French. In dispersing the effort of the German military, rather than concentrating it, Ludendorff had made a fatal mistake.

While the German advance against Fifth Army continued and Ludendorff altered his planning, the French Government prepared to evacuate to Bordeaux, and dissension struck the Allied ranks. With his front in jeopardy, even after moving what British reinforcements that could be spared to the scene, Haig called on Pétain to concentrate 20 French divisions in the area of Amiens. Fearing that the German attack was but a ruse to lure French reserves away from the defence of Paris, Pétain declined. Shocked, Haig recorded in his diary, ‘I at once asked Pétain if he meant to abandon my right flank. He nodded assent and added “it is the only thing possible, if the enemy compelled the Allies to fall back still further”.’

‘We moved steadily, encouraged by the feeble opposition. Small parties of enemy soldiers - from three to seven men - surrendered. They gave us cigarettes for which we gave them a friendly pat on the shoulder and sent them off to the rear.

‘Then we came under heavy fire from a strongpoint in the ruins of the château in Selency. The fog had lifted by then. Our creeping barrage had missed this, and we had fallen behind the barrage. We attacked one post here without success, and then I found a way round to get at it from the rear. We tried six times in all, and at last we captured it and the English defenders. There was a captain and one other officer and 14 men. The captain was wounded and I took him to our dressing station, where our doctor, an affable gentleman with the rank of major, dressed his wound. They had quite a talk. The captain said, “We English always say that there’s not enough room in the world for both us and the Germans and, now, here I am sharing a hole only a metre wide with a wounded German grenadier!”’

The Allies were at a dangerous impasse. It seemed to many within the French military that the British, who in their view had fallen back too quickly, were going to disengage from the French Army to defend the Channel ports. The British, on the other hand, believed that the French were leaving the BEF to its fate and had chosen to defend Paris rather than fight a unified Allied campaign. The BEF and the French were in grave danger of fighting two separate wars.

Amid the deteriorating situation, the Supreme War Council met in emergency session on 26 March, at the city hall of Doullens. Clemenceau planned to use the meeting to push for a unified Allied command, and initially favoured Pétain for the position. However, when Pétain arrived at the meeting he was despondent and told Clemenceau, ‘The Germans will defeat the English in open country, after which they will defeat us.’ Foch, though, stood firm, and when Pétain suggested the evacuation of Paris Foch yelled, ‘Paris has nothing to do with it! Paris is a long way off! It is where we now stand that the enemy will be stopped!’ Clemenceau then asked Foch for his thoughts on the situation. Foch responded:

As German troops moved forward in Operation Michael, they came upon mountains of Allied supplies, commodities that they had not seen for years. Ernst Jünger recalled upon capturing a British military kitchen:

‘There was a whole boxful of fresh eggs. We sucked a large number on the spot, as we had long since forgotten their very name. Against the walls were stacks of tinned meat, cases of priceless thick jam, bottles of coffee-essence as well, and quantities of tomatoes and onions; in short, all that a gourmet could desire. This sight I often remembered later when we spent weeks together in the trenches on a rigid allowance of bread, washy soup, and thin jam. For four long years, in torn coats and worse fed than a Chinese coolie, the German soldier was hurried from one battlefield to the next to show his iron fist yet again to a foe many times his superior in numbers, well equipped, and well fed. There could be no surer sign of the might of the idea that drove us on. It is much to face death and to die in the moment of enthusiasm. To hunger and starve for one’s cause is more.’

Although Jünger took the obvious supply disparity between German and Allied soldiers almost as a badge of honour, many of his compatriots saw the bursting British kitchens as a sign that if the attacks of spring 1918 failed Germany could not hope to hold out much longer against such well supplied foes.

‘Oh, my plan is not complicated. I would fight without a break. I would fight in front of Amiens. I would fight in Amiens. I would fight behind Amiens. I would fight all the time, and, by force of hitting, I would finish by shaking up the Boche; he’s neither cleverer nor stronger than we are. In any case, for the moment it is as in 1914 on the Marne; we must dig in and die where we stand if need be; to withdraw a foot would be an act of treason.’

Foch’s optimism invigorated those present, and, surprisingly to many, Haig proved to be one of the greatest supporters of the idea of placing Foch into a position of supreme command. Having won the day, the Supreme War Council authorized Foch to ‘coordinate the action of the Allied armies’. After the agreement had been reached, Clemenceau remarked to Foch that he now had the command that he had wanted, to which Foch replied, ‘It is a fine present you’ve made me; you give me a lost battle and tell me to win it.’ Although the situation remained critical, Foch was pleased to find that one of his first visitors after his appointment was Pershing, who volunteered to put his fears of amalgamation to one side for the common cause, stating, ‘The American people would consider it a great honor for our troops to be engaged in the present battle. . Infantry, artillery, aviation, all that we have is yours; use them as you wish.’

‘One Lewis gunner was left behind in the long tangle of empty trenches. ... Every minute widened the distance between him and his comrades, and, if he were to be wounded, he had neither help nor pity to expect.’

The Munsters in the Retreat from St Quentin, 27 March 1918

A destroyed British tank being examined by German soldiers, although it appears to have been stripped of anything of worth already. Although of great value in attacks, Allied armour had very little use in defending against the fast-paced German Spring Offensives.

While the Allies sorted out their command situation, the German advance edged closer to the critical rail junction of Amiens. Although too much blame was attached to his command failings and too little claim given to new German methods, Haig replaced Gough with Rawlinson and the British defence stiffened, even as Foch worked to rush Allied reinforcements to the threatened area. However, it was, in many ways, the tactical reality of battle in World War I that forced Operation Michael to grind to a halt. As in previous Allied advances, the German forward movement had negated the tactical advantages that had made the advance possible. German forces had taken heavy losses, were tiring, had outrun their critical artillery support and most importantly had also outpaced their own supply system. Thus, as defenders gathered in ever-greater numbers, it became clear that the Germans had not actually ruptured the Allied lines, but only bent them.

After the British Third Army decisively defeated the second phase of the German offensive, Operation Mars, on 28 March, the forward movement of Operation Michael stalled outside Villers-Bretonneux, well short of Amiens. The Germans had succeeded in achieving a tactical wonder, and in places had advanced nearly 64km (40 miles) and captured 90,000 prisoners of war, while inflicting 178,000 casualties on the British and 70,000 on the French. However, the gains had come at the prohibitive cost of 239,000 German killed, wounded and missing. Victory had not been achieved, the British had not been pushed into the sea and the French had not collapsed. For all of their effort, Ludendorff’s men had only created a vulnerable bulge into the Allied lines, and had captured no goal of strategic significance. Making matters worse, losses were most heavy among the stormtroops that had occupied the van of the advance. Virtually all of the mobile and attack divisions, those trained in the tactics that had made Operation Michael such a notable tactical success, were now exhausted, with many down to a strength of only 2000 men.

German troops rush through the areaofagas attack. Although gas had become much more lethal by 1918, effective defensive measures meant that gas was more ofa nuisance weapon, designed mainly to sow confusion among defending forces.

After the close of the conflict, several of the younger members of the German general staff ascribed the failure of Operation Michael and the other German spring offensives of 1918 to the command limitations of Ludendorff himself. Operation Michael had begun as a planned effort to roll up the British flank toward the sea, but Ludendorff had altered his planning in an attempt to build on gains where they were the easiest, on the front of the British Fifth Army, rather than where those gains would net the greatest strategic result. In consequence, the German drive only made gains where the Allies could afford to give ground, and finally settled on Amiens as a goal almost by default. Major Wilhelm von Leeb, who later became a field marshal under the Third Reich, recorded his thoughts and commented, ‘OHL [the German general staff] has changed direction. It has made its decisions according to the size of territorial gain, rather than according to operational goals. ... We had absolutely no operational goal. That was the trouble.’

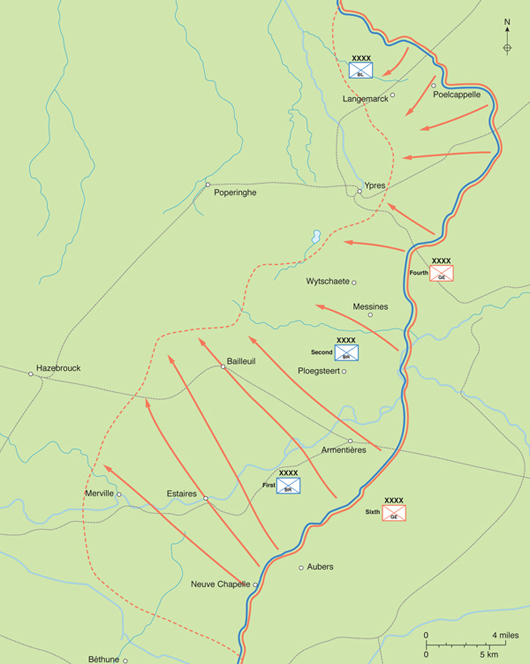

Certain that the Germans would soon resume their offensives, and fearing that their aim would shift to the vulnerable Channel ports, Haig asked Foch to transfer French reserves northwards. Ever optimistic, though, Foch demurred and began planning for a limited Franco-British offensive south of the Somme. Haig, however, had proved prescient, for on 9 April the German Fourth and Sixth armies struck British lines in Flanders, opening Operation Georgette, which had as its goal the severance of the critical Allied rail junction at Hazebrouck. Demonstrating the cost of the attrition suffered during Michael, the 55 German divisions that took part in the offensive included only attack and inferior trench divisions, instead of the elite mobile divisions that on 21 March had achieved such success. Although the offensive was weaker than that of Operation Michael, it struck a part of the lines of the British First Army occupied by two poorly trained and understrength Portuguese divisions. Shocked by the ferocity of the assault, the Portuguese divisions gave way and fell back nearly six kilometres (four miles) in a single day, threatening the Allied lines in the region with collapse.

Operation Georgette, the German offensive against the British Second Army in Flanders. Although they managed to drive the Second Army back from their frontline positions, the Germans failed to break through to the critical Allied rail junction at Hazebrouck.

Fearing the worst, Haig again appealed to Foch for reserves, but the commander-in-chief, believing the German attack to be a diversion, initially refused to intervene directly in the battle. Frustrated, Haig rushed what reserves he could to the scene, and placed the defensive battle in Flanders under the control of one of his most effective commanders, General Plumer. With German forces nearing Hazebrouck, the capture of which would dislocate all British defensive planning, Haig on 11 April issued the following order of the day:

German soldiers around and atop their massive A7V tank. Sporting as many as six machine guns, as well as a main gun, the A7V could carry up to 18 men. Although produced in too few numbers to have an effect on the war, the A7V first saw combat at St Quentin in March 1918.

German Crown Prince Wilhelm at St Quentin in May 1918. Confident of victory, the German royal family prematurely toasted the coming end of the war with champagne. Wilhelm commanded the Army Group Crown Prince, which controlled the Seventh, First and Third armies.

‘Many of us are now tired. To those I would say that victory will belong to the side which holds out the longest. ... There is no course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the freedom of mankind alike depend upon the conduct of each one of us at this critical moment.’

Haig fumed that the BEF faced the threat alone, while the French stood by awaiting a presumed German offensive further to the south and on 14 April reiterated his need for reinforcements to Foch stating, ‘If the necessary measures are not taken, the British army will be sacrificed and sacrificed in vain.’ Even without significant French aid, though, the British defence soon began to stiffen, but not until Plumer had made the difficult decision to abandon much of the ground gained during the previous year’s fighting at Passchendaele in favour of a withdrawal to more defensible lines closer to Ypres. After the Germans struck Belgian forces on 17 April north of Hazebrouck, Foch belatedly realized that Georgette was in fact the next German effort at victory on the Western Front, and he quickly formed the Detachment of the North and inserted it into the fray.

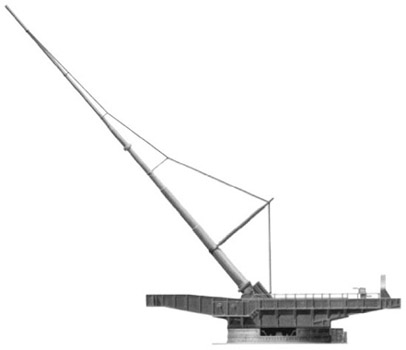

The mighty German Paris Gun, which began shelling Paris on 23 March 1918. Six of the powerful weapons eventually fired 367 shells on the French capital, resulting in 880 casualties. It was destroyed by the Germans before the war’s end.

With Allied reserves shifting the strategic balance in the north, on 29 April, after a minor tactical victory in seizing Mount Kemmel from French forces, Ludendorff brought Georgette to a halt. As usual, the offensive had begun with optimism and had achieved its greatest gains in the first few days of fighting. Soon, though, the resilience of the BEF, combined with the tactical realities of World War I, forced the German advance to stall. Although the German Fourth and Sixth armies had advanced in some places nearly 19km (12 miles), they had failed to achieve any of their strategic goals and had only created another salient into Allied lines that would prove difficult to defend, all at the cost of 100,000 additional casualties. Ludendorff had failed to grasp the fact that offensives in World War I, no matter their technical wizardry, had a limited life span. Tactical proficiency alone was not the answer to winning World War I.

After the conclusion of Georgette, there existed considerable tension in the Allied camp, with the British questioning the late French entry into the Flanders fighting. Many within the BEF felt that the British had borne the heaviest burden of fighting off the two massive German offensives, while the French had done but little. In fact, the French were still bearing the greatest burden of all, occupying 580km (360 miles) of the Allied front lines, against only 135km (84 miles) for the British and 35km (22 miles) for the Belgians. In part to soothe Haig’s ruffled feathers, and as a component of a general reshuffling of Allied lines to move more strength to the north of the Oise River, Foch arranged for the transfer of four exhausted British divisions to a quiet sector of the French front. The quiet sector, though, was along the Chemin des Dames, which placed the British divisions directly in the path of the next great German offensive.

Having failed in his first two attempts to win victory, Ludendorff concocted a new plan for a two-stage offensive beginning with a diversionary attack on the Chemin des Dames aimed towards both Reims and Paris, which he hoped would force the Allies to shift reserves away from Flanders. Then, with Allied forces in the north fatally weakened, the main German offensive would fall in Flanders, driving the British into the sea. Facing the German attack on the Chemin des Dames were six Allied divisions (three French and three British) of the French Sixth Army, under the command of General Denis Duchene, which held a 50km-long (31-mile) front. Earlier in the year, Pétain had given his commanders express advice that German advances had to be met with a defence in depth, advising them that, ‘We do not have enough infantry divisions to accept a defensive battle on the first position. It is necessary then to manoeuvre and make the terrain work for us.’ Duchene, though, chose to ignore Pétain’s guidance and placed most of his defenders forward atop the Chemin des Dames, well within the range of German artillery fire, in positions especially vulnerable to stormtroop tactics.

In 1916 the Germans began efforts to develop a ‘super artillery piece’ capable of shelling Paris. Choosing to modify a 15in naval gun for the task, the Germans developed a weapon with a barrel that was 40m (43 yards) in length and weighed 128 tonnes (142 tons). The massive gun, which could only be transported by train, fired a projectile to a distance of 129km (80 miles), which, during flight, reached into the upper stratosphere, some 39km (24 miles) high, and then fell silently to the ground. On 23 March 1918 the Germans unleashed their new weapon, six of which eventually entered service, on the unsuspecting inhabitants of Paris. Through 9 August 1918, the terror weapons fired 367 shells at Paris, resulting in 880 casualties, including 250 killed. However, the shelling was so sporadic that it failed to damage French morale, and thus did not aid materially in the German war effort. Late in World War II, though, Adolf Hitler would copy the purpose of the Paris Gun, when he too decided to place emphasis on revenge weapons aimed at crushing Allied morale.

The Paris Gun was a marvel of modern engineering, boasting a barrel 40m (43 yards) in length, which could fire a projectile to a distance of 129km (80 miles).

At 1.00am on 27 May, the heaviest single German artillery barrage of the war, involving 4000 guns firing more than two million shells in under five hours, struck Duchene’s Sixth Army. Of the 36 German divisions massed for the assault, of which 27 were veterans of Operation Michael, three struck the French 21st Division, five the French 22nd Division and four the British 50th Division. Outmanned and slaughtered in their forward positions, the Allied divisions gave way, and the Germans surged forwards. Although Duchene attempted to retrieve the situation by throwing reserves into the fray, he did so rather indiscriminately and by the end of the day the victorious Germans had seized bridges across the Aisne River and had halted just outside Fismes on the Vesle River. For the next four days the Germans moved forward an additional 35km (22 miles), reaching the Marne River only 90km (56 miles) from Paris. Operation Blücher had already achieved much more than Ludendorff had intended, and he now faced his last major strategic decision of the war. Should he adhere to his original plan and strike the British in Flanders, or continue the advance toward Paris? Even though the Allied defence was already stiffening, and the prerequisites for tactical success were fading as exhausted German forces moved more than 145km (90 miles) from their logistical railheads, Ludendorff again chose tactics over strategy, gambling all on an effort to take Paris.

French cavalry on patrol passing a British artillery unit. In the semi-fluid warfare of 1918, cavalry reconnaissance patrols once again had renewed value. In fact all sides continued to use cavalry throughout the battles of 1918.

Ludendorff seemingly had ample reason for optimism. Pétain informed Foch on 1 June, ‘Since May 27 the battle has absorbed thirty-seven divisions, including five British. Seventeen of these divisions are completely exhausted; of these two or three may not be able to be reconstituted. Sixteen have been engaged for two, three or four days.’ The situation was so bleak that the French general staff even began planning for withdrawing completely from northern France in an effort to consolidate defending units around the capital. Foch, though, remained firm in his belief in victory, and unleashed a flood of reserves, including the Fifth and Tenth armies, directing that the incoming reinforcements form a coherent line of defence near Château Thierry.

As Operation Blücher got underway on 27 May, American forces launched their first offensive action at Cantigny, near Montdidier in the Somme region, an operation undertaken in many ways to test the offensive abilities of the newly arrived American forces. The 28th Infantry Regiment of the American 1st Division led the assault on Cantigny, which served as a forward observation point for General von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army. On 28 May, supported by the fire of 368 French heavy guns and French flamethrower teams, American troops quickly seized their objective and captured 200 German prisoners. With continued French artillery support, the Americans withstood seven German counterattacks in the next few days, but held on to their gains at the cost of 1603 casualties, including 199 killed. Boleslaw Suchocki of the 28th Infantry Regiment recalled that after crossing the German barbed wire:

‘I noticed that the boys were falling down fast. A shell burst about ten yards in front of me and the dirt from the explosion knocked me flat on my back. I got up again but could not see further than one hundred feet. ... The German artillery was in action all the time. ...I stopped at a strongpoint and asked the boy in the trench if there was room for me to get in. [He responded] “Don’t ask for room, but get in before you get your [!#%&] shot off!”’

The arrival of American forces on the battlefront, including these soldiers rushing into the attack, helped to revive flagging Allied morale.

Although the offensive at Cantigny was only a minor operation, it, coupled with later American actions at Château Thierry and Belleau Wood, indicated that the AEF was ready to play an ever-greater role in World War I, which portended disaster for Germany.

As part of Pershing’s agreement to allow the use of American forces in battle, US troops saw their first meaningful combat of the war as part of the effort to defend against Operation Blücher, with the 1st Division launching a minor offensive near Cantigny, while the 3rd Division took part in defensive fighting at Château Thierry during the first week of June and the 2nd Division fought a confused engagement at Belleau Wood. In each case the American units acquitted themselves well, which, as the German drive stalled during the first week of June, signalled the ultimate failure of the German effort to achieve victory. Paris had not fallen, the British had not been driven into the sea and valuable German resources were being wasted in tactical masterpieces that only created salients into the Allied lines, while 250,000 fresh American troops arrived on the battlefronts of France every month. The appearance of the Americans was a tonic for the morale of the battered French Army and the BEF. A French officer commented on the meaning of the first American battles:

‘The spectacle of this magnificent youth from across the sea, these youngsters of twenty years with smooth faces, radiating strength and health in their new uniforms, had an immense effect. They offered a striking contrast with our regiments in soiled uniforms, worn by the years of war, with our emaciated soldiers and their sombre eyes who were nothing more than bundles of nerves held together by an heroic, sacrificial will. The general impression was that of a magical transfusion of blood taking place.’

German gains during Operation Blücher, the offensive across the Chemin des Dames Ridge and the Aisne River. French defensive mistakes allowed German troops to get as far as the Marne River, within 90km (56 miles) of Paris.

Still confident that superior German tactics would provide ultimate victory, on 9 June, Ludendorff launched his fourth attack of the spring, Operation Gneisenau, north of the Oise River between Noyon and Montdidier. The attack, which if successful would join the salients created by Operations Michael and Blucher and put the German Army in a better position to threaten Paris, pitted Hutier’s Eighteenth Army against the French Third Army. Warned of the coming attack by accurate intelligence, the French had pre-positioned in the area 12 infantry and three cavalry reserve divisions, and even began their counterbarrage before the German guns opened their own preparatory fire. The French barrage notwithstanding, at 4.00am the German infantry went over the top into the attack, and advanced nearly eight kilometres (five miles) on a 24km (15-mile) frontage. Having learned little from Duchene’s mistake at the Chemin des Dames, Third Army had located its defenders forwards, which helped to make the German advance possible.

Allied forces, though, had not been surprised and had learned how to counter German tactics, and within two days, reserve divisions entered the battle and stopped the German advance in its tracks. Marking a fulcrum point of the war, on 11 June a force of five divisions, two of which were American, launched the first major Allied counterattack of the spring. The Allied divisions, under the command of General Charles Mangin, made only sporadic gains, but shocked the Germans who, after having held the initiative for so long, were suddenly thrown onto the defensive. Having lost 40,000 casualties for minimal gains, on 13 June Ludendorff cancelled Operation Gneisenau.

Exhausted and bloodied, having lost 209,000 men in June alone, the German Army had once again reached the gates of Paris. However, the situation had become critical. Because of their tactical successes, the weakened and increasingly dispirited Germans had to occupy an additional 120 kilometres of undulating and vulnerable front lines. The Prussian War Ministry warned Ludendorff that the stormtroop formations had been destroyed, while General Hutier reported mounting indiscipline even within the ranks of his elite Eighteenth Army. On the German home front the Berlin police warned the government that increasing numbers of civilians were demanding ‘peace at any price’. In the Allied camp, even the notoriously pessimistic Pétain noted that increasing German weakness coupled with the arrival of the Americans had shifted the balance of the war stating, ‘If we can hold until the end of June, our situation will be excellent. In July we can resume the offensive. After that, victory is ours.’

Believing that attack remained the key to victory, and unable to admit the failure of his ambitious scheme to win the war, Ludendorff prepared to drive his weary troops into battle yet again, on both the eastern and western sides of Reims. By the second week of July, though, French intelligence had discerned the location of the coming offensive, which allowed Foch to gather reserves, while Pétain’s forces made ready their defences. Having become fully conversant with German methods, the French held their front lines very thinly, while main forces waited out of artillery range to blunt the German assault. Most important, though, Foch and Pétain, aided by the fiery Mangin who had been elevated to the command of the French Tenth Army, decided that Ludendorff’s offensive was a perfect opportunity to launch a massive counter-offensive designed to destroy the Aisne-Marne Salient.

After considerable discussion in early July, Foch and Pétain agreed that French forces would first blunt the German offensive. Then the French Tenth and Sixth armies would strike the western face of the Aisne-Marne Salient at Soissons, while subsidiary counterattacks took place on the eastern face of the salient near Reims and along the Marne River to the south. So sure were Foch and Pétain in their planning that they committed virtually the entire Allied reserve to the coming battle, even convincing a reluctant Haig to send his reserves south to take part in the fighting. By the time of the battle, the French had a reserve force of 38 infantry (including four British and five American) divisions and six cavalry divisions in the Marne area. Only one division remained in reserve in the entire region between the Argonne and Switzerland, while only one British division was held in reserve on the front covering Paris itself. At the crucial point of the war, Foch and Pétain had taken decisive action and had literally bet everything on the outcome of the coming battle. It was also a testament to Foch’s ability as supreme commander that in what became known as the Second Battle of the Marne, for the first time in the war French, British and American forces joined in the same battle, making it a truly Allied affair.

Attacking on the morning of 15 July, the German First and Third armies made only fitful progress against the well prepared French Fourth Army east of Reims, which led Ludendorff quickly to suspend offensive action in that sector. Southwest of Reims, though, the German Seventh Army made better progress against the French Fifth Army and crossed the Marne River near Dormans. Only the French 39th Division and the US 3rd Division held their place on the Marne near Château Thierry. Shaken by the German advance, on 15 July, Pétain ordered reserves to be taken from the units slated to take part in the counterattack to aid in the defence of the Marne. Foch, though, rescinded the order and promised Pétain reserves from other parts of the front.

A German stormtrooper in 1918. Although the Spring Offensives had achieved remarkable tactical goals, by June the stormtroop formations that made the gains possible had been destroyed for little of strategic value.

Foch proved correct, and after only minimal further gains along the Marne, on 17 July the German attack stalled. Although all seemed ready for the massive Allied counterstrike, Foch still had to contend with distractions. On the eve of the counterattack, Pétain called for units to be taken from the Tenth Army to solidify the defences of Paris. The very next day Haig, who feared a renewal of the German offensive in Flanders, demanded the return of the British units scheduled to take part in the Marne counterattack. Foch refused both requests. While both Pétain and Haig lost their nerve at the critical moment, Foch refused to allow the subversion of his strategic vision. The supreme commander had taken a great risk in overruling the advice of the commanders of the French and British armies, and, thus, to Foch falls the credit for the subsequent victory in the Second Battle of the Marne.

Allied forces gathered quickly to undertake their historic counterattack, with the American 2nd Division marching for 50 hours in a 72-hour period just to reach its jumping-off point near Buzancy. Mangin’s French Tenth Army, which was to play the most important role in the counterattack, stood as testament to the Allied nature of the battle. Of the 22 infantry and two cavalry divisions that made up Mangin’s force, two were American (the 1st and 2nd divisions), two were British (the 15th and 34th divisions), the French 58th Division was from Morocco (which in fact also contained numerous Senegalese soldiers), and many of the troops had been transported to the front by trucks driven by Vietnamese labourers.