Supported by tanks and lethal artillery barrages, British infantry units proved capable of utilizing infiltration tactics to redefine the nature of combat on the Western Front as the balance of power shifted once more towards the Allied side in 1918.

Under the supreme command of Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Allies unleashed waves of attacks that even pushed the Germans from the mighty defences of the Hindenburg Line. As the Allies proved their tactical mastery of the battlefield, and Americans entered the lines in ever-greater numbers, even Ludendorff came to the realization that the war had been lost.

Even before the Second Battle of the Marne had fatally shifted the balance of the war against the Germans, several leading Allied commanders had sensed that the tipping point was near and had begun planning to retake the initiative in the war. Within the BEF, on 5 July, General Rawlinson, in command of Fourth Army, proposed to Haig an attack near Amiens, after a successful assault by Australian forces near Hamel had proved both the resurgent nature of the BEF and the relative weakness of German defences. Intrigued by the idea, Haig gave Rawlinson the go ahead to continue his planning.

While Haig and Rawlinson laid the groundwork for their offensive, Foch thought in even more grandiose terms and by mid-July was hatching a plan to launch a series of blows against German defences all along the Western Front, aimed initially at retaking Dunkirk and Calais in the north, and reducing both the Amiens and St Mihiel salients farther south. In a 24 July meeting, Foch laid his proposals before Haig, who agreed that the time had come to pass to the offensive. The two commanders, though, still had to convince their reluctant governments, which had been made skittish by past military predictions of impending victory that had ended only in futile battles of attrition.

In London, Lloyd George was particularly ambivalent concerning the chances of any offensives on the Western Front and hoped to hold Haig in check while awaiting the arrival of more American forces before launching any counterattack. Ironically, though, Foch's position as supreme commander, which the Prime Minister had thought would limit Haig's strategic independence, actually served to shield the commander-in-chief of the BEF from Lloyd George's wrath. Foch, however, also had to face questions from Clemenceau, for even the Tiger felt that French forces were too exhausted to undertake a meaningful offensive. To convince reluctant politicians, Foch utilized his considerable powers of persuasion and his ebullient optimism, proclaiming that the momentum had changed and said, ‘We’re holding them. We’re hitting them in the flank. We’re kicking and punching them. We’re killing off the enemy. Our dead ... my son ... my son-in-law ... are avenged.’ When he faced Clemenceau's rebuttal that Allied forces were dropping with fatigue, Foch replied, ‘The Germans are dropping with still more fatigue.’ Although Foch later wrote that his statements caused many political and military leaders alike to take him ‘for a madman’, his arguments won the day. Regardless of their exhaustion the Allies were going to attack.

Even as the war came to a close, battlefield conditions were quite trying for the fighting men of all of the belligerent nations. Living in the open, as battle raged, men had only fleeting access to food and water, and had precious little time to bury the dead or care for their own hygiene needs. Wearing the same uniforms for weeks on end, amid the open sewers that made up their defensive positions, soldiers often became covered in lice. Private W.A. Quinton of the BEF recalled:

‘We did not notice the lice so much when standing, perished with cold, on lookout. But when we got in our tiny dugouts, and our bodies began to get warm, then out would come the lice from their hiding places in our clothing, forming up in columns of fours, would start route marching over our flesh. Yes! They were our bosom companions, and although we have joked about them, there have been times when, utterly worn out, both physically and mentally, yet unable to sleep because of the lice, I have known men to actually cry and curse the lice, and He who made them’

Life in the wilderness of the trenches during World War I was fraught with danger, even in times of relative calm.

The opening assault within Foch's broader offensive scheme was that of Rawlinson's Fourth Army, in conjunction with the French First Army under the command of General Eugène Debeney, in the area of Amiens. Judging that the Germans around Amiens had done but little to construct defensive works and were under strength, Rawlinson and Haig realized that speed was of the essence and took only three weeks to plan and prepare the coming offensive. The smoothness of the planning process in and of itself demonstrated both the progress that the BEF had made in the years since the Somme and the maturation of Haig as a commander. Rawlinson's draft scheme called for an attack by 11 divisions on a 17,375m (19,000-yard) front from Morlancourt to Demuin, which aimed at penetrating the German lines to a depth of 5490m (6000 yards), a mammoth goal considering the relative lack of forward movement in earlier British offensives.

Both technological and tactical innovations within the BEF in the years since the Somme made seeking such gains realistic in 1918. Infantry units now packed a considerable punch, with each British battalion including 30 Lewis guns (portable machine guns), eight light trench mortars and 16 rifle-grenadiers, enabling it effectively to deal with enemy strongpoints without having to wait for cumbersome artillery support. Aided by a force of over 500 tanks, the infantry units of the Fourth Army, instead of moving forward in waves, planned to utilize speed and infiltration tactics to advance to depth in an attack reminiscent of Cambrai. Rawlinson and Haig had also gathered a force of 1236 field guns and 677 heavy guns to support the offensive, against only 530 German guns in the area. As at Cambrai, the British artillery utilized silent registration and chose to forgo a preliminary bombardment in order to maintain surprise. Of the greatest importance, intelligence, including flash spotting and aerial reconnaissance, had pinpointed the exact locations of no fewer than 504 of the German guns, which would enable counterbattery fire effectively to silence the German artillery on the day of the attack. Finally, in the Amiens sector the Allies had gathered a force of 1900 aircraft, against only 365 German machines, and planned to utilize their resultant command of the air in a ground-attack role to augment the advance. Through years of learning, the BEF by 1918 had become an integrated weapons system, one that used the most modern tactics within a rubric of all-arms coordination that in some ways more foreshadowed the tactics of World War II rather than hearkened back to the Somme. LieutenantGeneral John Monash, the commander of the Australian Corps, put the new British military system into words: ‘A modern battle plan is like nothing so much as a score for a musical composition, where the various arms and units are the instruments, and the tasks they perform are their respective musical phrases. Each individual unit must make its entry precisely at the proper moment, and play its phrase in harmony.’

General Sir Herbert Plumer and French Premier Georges Clemenceau discuss the course of the Allied counterattack. Although the civilian leaders on the Allied side were nervous about the prospects of attacks in the summer of 1918, the Allied military commanders were keen to forge ahead.

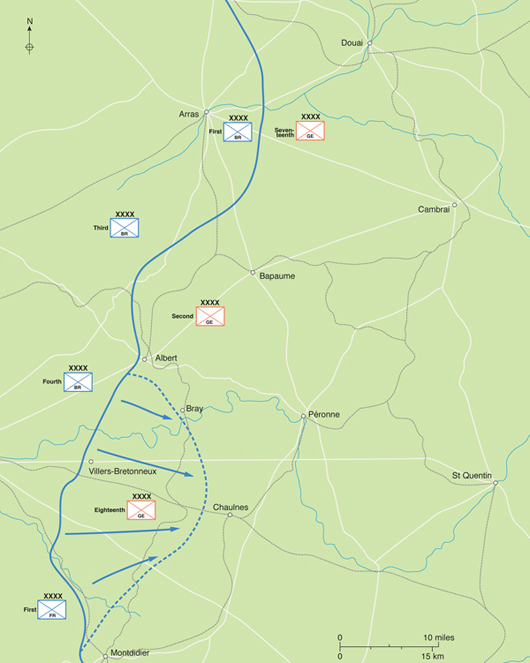

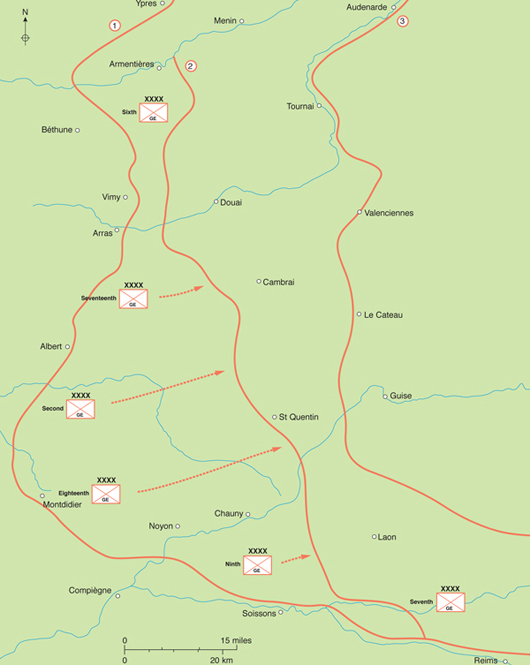

The Battle of Amiens, launched on 8 August 1918, saw the British Fourth Army under Sir Henry Rawlinson reduce the Amiens Salient, it was the offensive action that touched off the ‘Hundred Days’. In common with many late war British offensives, it was spearheaded by Dominion troops.

Haig and Rawlinson went to great lengths to ensure the secrecy of the coming offensive, including gathering forces at night and massing tanks in wooded areas as aircraft buzzed the German front lines to cover the telltale noise of the tanks’ engines. Much effort also went into deception, especially as regards the movements of the Canadian Corps. Under the command of First Army, the Canadians represented the most powerful and cohesive corps within the BEF, were well rested since they had not seen much action during the German Spring Offensives, and were regarded by the Germans as the shock troops of the BEF. Understandably, Rawlinson and Haig wanted the Canadians to play a major role in the fighting at Amiens, but realized that quickly shifting the corps from the front of First Army to Rawlinson's Fourth Army would be a red flag to German intelligence. In order to confuse the Germans, the British ordered two Canadian battalions to move to the front of Second Army, in the vicinity of Mount Kemmel, and to simulate the presence of the entire corps through the use of false radio traffic. The security measures undertaken by Haig and Rawlinson were a complete success, enabling Fourth Army to amass a strength of more than 400,000 men against only 37,000 German defenders, who, having become complacent during their string of successful attacks, had not taken the time to construct effective defensive networks.

The Sopwith Camel, the most famous British fighter of the war, produced in response to the German Albatros D-types. The Camel's manoeuvrability and agility made it a match for nearly every German aircraft.

The first that the Germans knew about the attack was when, at 4.20am on 8 August, from left to right the British III Corps, the Australian Corps and the Canadian Corps advanced under cover of a thunderous barrage and emerged from a heavy mist, an assault augmented shortly thereafter by an advance of French First Army on the right flank. Shocked by the ferocity of the attack, without supporting artillery fire and constantly harassed by strafing aircraft, the German defenders quickly gave way. The strongpoints and machine-gun nests that did hold out against the initial attack soon found themselves surrounded by the quick-moving infantry or facing destruction by the accompanying tanks. The resulting victory was spectacular, with Fourth Army, except on its extreme flanks, reaching all of its major goals, advancing up to 13km (eight miles), capturing 400 enemy guns, inflicting 15,000 casualties and capturing 12,000 prisoners, all at a cost of only 9000 casualties. On the right flank Debeney's French First Army fell somewhat short of its final objectives, failing to capture the village of Fresnoy, but it still advanced nearly eight kilometres (five miles), while capturing 3000 prisoners. Haig was understandably heartened by the victory, due in great part to the brave accomplishment of Dominion forces, and recorded in his diary that, ‘the situation had developed more favourably for us than I, optimist though I am, had dared even to hope!’

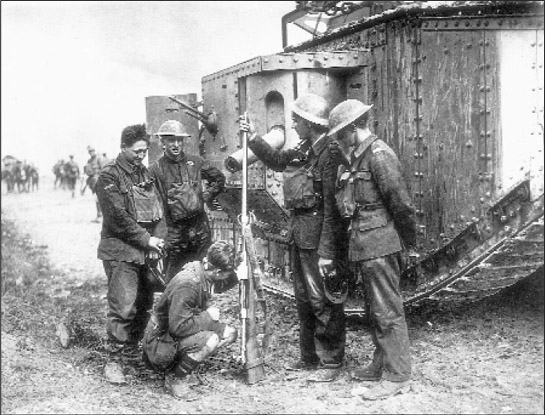

British tankers examine a captured German weapon meant to fire armour-piercing rounds. The large numbers of tanks available to the Allies ensured that they would play a major role in the campaigns of 1918. However, the Germans had also developed a number of countermeasures.

With Haig and Rawlinson expecting even greater results, possibly including cavalry action, the attack continued the next day. Although the renewed offensive achieved an advance of a further five kilometres (three miles), the entropy began to set in that so typified even successful attacks during World War I. Exhausted units began to lose cohesion in the advance and outran their vital artillery support, tanks broke down in droves and communications suffered terribly. The attack slowed further on 10 August, with only the French, with Debeney unleashing two fresh corps into the attack, making substantial gains, in some areas advancing nearly six kilometres (four miles). As the attackers weakened, in contrast the Germans rushed reinforcements, both men and guns, to the battle area. Without a weapon of exploitation, the gains of the first day of the offensive, made possible by detailed planning and overwhelming firepower, were no longer possible as the initiative in the battle shifted back to the defender. In similar situations during the German Spring Offensives, Ludendorff had sacrificed his strategic aim to pursue the chimera of tactical breakthrough, pursuing his offensives long after they had lost the prerequisites for forward momentum. Such, though, was not to be the case with Haig and Foch.

On the first day of the Battle of Amiens, BEF formations captured in excess of 12,000 German prisoners. This was one of the first occasions on which German troops gave themselves up in large numbers, something that worried Ludendorff more than the loss of territory.

After only four days of fighting Haig called an end to the Battle of Amiens, a halt initially designed only to allow Rawlinson's Fourth Army and Debeney's First Army a chance to regroup. However, the commander of the Canadian Corps, General Arthur Currie, whose soldiers had done so much to make the victory possible, informed Rawlinson and Haig that he believed the continuation of the offensive to be a ‘desperate enterprise’, given the shifting balance of forces. After listening to his subordinate, Haig called off a further attack in the area in favour of shifting the weight of a continued BEF offensive onto the fronts of the First and Third armies. At a meeting on 14 August, though, Foch pressed Haig to continue advancing at Amiens, a demand to which Haig responded angrily, recording in his diary, ‘I spoke to Foch quite straightly and let him understand that I was responsible to my Government and fellow citizens for the handling of the British forces. Foch found Haig's reasoning, supported by Rawlinson, Currie and Debeney, to be sound and agreed that the Battle of Amiens had run its course. The supreme commander, like Haig, had already come to the independent conclusion that what was required on the Western Front was not a single offensive prosecuted beyond the tactical point of reason. Instead, both Foch and Haig advocated a series of interrelated offensives, aimed at applying constant pressure on the Germans while keeping them off balance: short, sharp offensives that benefited from thorough preparation and forced the Germans constantly to shift their dwindling reserves from place to place, all the while never knowing from where the next attack would come. Unlike Ludendorff, the Allied command team of Foch and Haig, who commanded military formations that were as tactically adept as the Germans, had discovered how to prosecute battles at the operational level of war.

The Battle of Amiens, coming fast on the heels of the reverse suffered in the Second Battle of the Marne, came as a severe psychological blow to Ludendorff, who, in his memoirs, wrote: ‘August 8 was the black day of the German Army in the history of the war. This was the worst experience I had to go through. . August 8 made things clear for both army Commands, both for the German Army and for that of the enemy.’

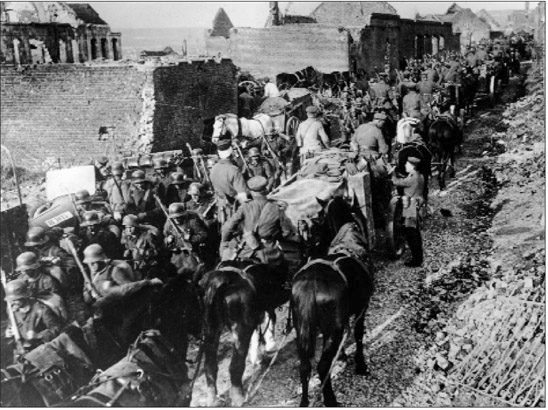

German troops retreating during the Battle ofAmiens. Ludendorffreferred to the opening dayofthe attack, 8 August 1918, as ‘the black day of the German Arm/. The Germans suffered the loss of 48,000 men in the battle, 29,873 of whom became prisoners of war.

World War I saw the widespread use of poison gas, ranging from phosgene, which attacked the lungs, to mustard gas, which caused severe burning both to the skin and to the respiratory system. Although both sides developed countermeasures against such attacks, the gruesome deaths suffered by gas victims made the weapon among the most feared of the entire war. Private W.A. Quinton of the BEF recalled reaching a front-line trench in which he discovered the remnants of a company that had suffered a gas attack:

Soldiers left unprotected during a gas attack faced the grim prospect of a lingering death, as their lungs slowly rotted away.

‘Black in the face, their tunics and shirt fronts torn open at the necks in their last desperate fight for breath, many of them lay quite still while others were still wriggling and kicking in the agonies of the most awful death I have ever seen. Some were wounded in the bargain, and their gaping wounds lay open, blood still oozing from them. One poor devil was tearing at his throat with his hands. I doubt if he knew, or felt, that he had only one hand, and that the other was just a stump where the hand should have been. This stump he worked around his throat as if the hand were still there, and the blood from it was streaming over his bluish blackface and neck.’

Unnerved by the reverses, Ludendorff was certain that Germany had lost the war. Blaming the impending defeat on ‘agitators’ and a breakdown of civilian morale rather than on his own misguided military efforts, Ludendorff offered his resignation, which the Kaiser refused. After the Battle of Amiens had ended, Ludendorff regained a measure of composure, but still, along with Hindenburg at a conference on 14 August, informed the Kaiser that the German Army had, ‘reached the limits of our endurance’. Regardless of the perilous circumstances, though, the German command team chose to have the German Army make a stand in France in the faint hope that a bloody attritional battle centred on the Hindenburg Line would force the Allies into a negotiated peace. Having weathered a crisis of confidence, Ludendorff had chosen to fight on until the end.

Determined to press their advantage, Foch and Haig orchestrated a series of offensives over the next weeks that denied the reeling Germans any respite. To the south the French armies assailed German lines, and on 20 August General Mangin's Tenth Army drove the Germans back nearly 13km (eight miles) in the area between the Oise River and Soissons. At the same time, Haig's forces spread the attack to the north, with the British Third Army, under General Julian Byng, attacking near the old Somme battlefield. Without the element of surprise or the numerical superiority that had characterized British success at Amiens, Byng moved into the Battle of Albert rather cautiously, earning Haig's ire, and scheduled a pause in the offensive after only one day to consolidate very limited gains. Mistaking the pause in operations as a defensive victory, General von Below ordered his German Seventeenth Army to counterattack on 22 August. With their forces weakened and facing stiff British resistance, the Germans suffered heavy casualties, which only served to ease the resumption of Byng's offensive. Supported by 98 tanks, Byng's forces renewed their advance on 23 August, and reached their final objectives across most of the front, unhinging the German defensive position. Although less spectacular than the gains made in the Battle of Amiens, in the Battle of Albert Byng's forces captured 10,000 Germans, and helped to convince Haig that the German Army was crumbling. Heartened by the prospect, Haig's natural sense of optimism returned, and he instructed his army commanders:

‘Methods which we have followed, hitherto, in our battles with limited objectives when the enemy was strong, are no longer suited to his present condition.

‘The enemy has not the means to deliver counterattacks on an extended scale, nor has he the numbers to hold a position against the very extended advance which is now being directed upon him.

‘To turn the present situation to account the most resolute offensive is everywhere desirable. Risks which a month ago would have been criminal to incur, ought to be incurred as a duty.’

On 26 August, the BEF extended its attack frontage north by opening an offensive on the front of General Henry Horne's First Army, which, spearheaded by Currie's Canadian Corps, advanced nearly five kilometres (three miles). A few days later, further to the south, Third and Fourth armies attacked, which resulted in Australian forces seizing the critical German defensive positions of Mont St Quentin and Peronne. At the same time, the French First and Third armies pushed forward nearly 13km (eight miles) and seized Noyon. Although they had been forced to give up a great deal of territory, the retreating Germans finally took shelter in the powerful belt of defences known as the Drocourt-Queant Switch Line, a subsidiary of the vaunted Hindenburg Line, where they hoped to hold through the winter and impose a morale-sapping war of attrition on their foes.

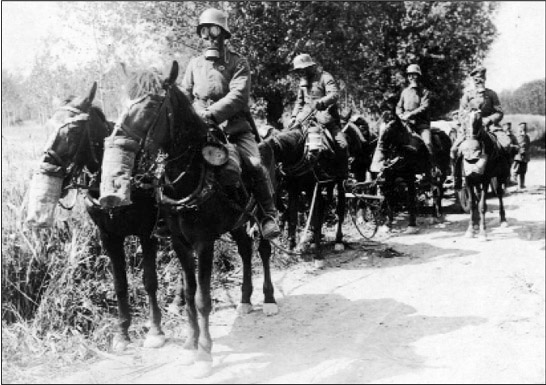

German troops rest during the retreat, but remain in readiness to face a gas attack. Although there were increasing numbers of motor vehicles being used to supply the armies on the Western Front, all sides relied on horse transport, with as many as 3000 horses per infantry division.

Now engaged in a series of semi-mobile battles rather than the all-too-familiar trench warfare, Horne's First Army paused before the imposing German defences of the Drocourt-Queant Switch Line to prepare for a difficult battle. Utilizing an innovative tactical plan developed by General Currie, and aided by deception as well as attacks on other fronts, the First Army, again spearheaded by the Canadians, assaulted the position on 2 September. Canadian and British soldiers advanced on a narrow front, covered by the withering fire of 762 guns, which fired 18,597 tonnes (20,500 tons) of ammunition – more than had been fired in the entire Battle of Amiens. The attack was an unqualified success, rupturing the Drocourt-Queant Switch Line on a frontage of 6400m (7000 yards), and taking 8000 prisoners. Allied forces had proven that they could break even the most powerful German defensive positions, while near constant attacks kept the enemy wrong footed.

‘This advance gives a sense of the enormous movement behind the British lines, and there is not a man who is not stirred by the motion of it. ... It is like a vast tide of life moving very slowly but steadily.’

Philip Gibbs, official British wartime reporter

The capture of Peronne and the breaking of the Drocourt-Queant Switch Line shattered the German plans for the remainder of the year and led Ludendorff to sanction a withdrawal to the main Hindenburg Line. As the Germans pulled back to what many considered a nearly impregnable defensive network, it became clear that the first phase of the Allied offensives had come to an end. Allied forces, on a front of nearly 113km (70 miles), had achieved a remarkable string of victories and had pushed the Germans back nearly 40km (25 miles), eradicating the gains of Ludendorff's Spring Offensives. The sense of accomplishment, however, was tempered by the fact that the Allies now faced the most formidable defensive network ever constructed on the Western Front.

As Haig and Foch paused to consider how best to assail the Hindenburg Line, the British Government very nearly lost its heart. While enthused by the recent string of victories, Lloyd George believed that the BEF did not have the strength to break the Hindenburg Line, and despaired that an attack on the mighty German defensive position would devolve into another Somme or Third Ypres. Hoping that Haig and Foch would call a halt to operations along the Western Front, pending the arrival of more American troops, Lloyd George had Wilson send Haig a telegram warning the commander-in-chief that the War Cabinet ‘would become anxious if we received heavy punishment in attacking the Hindenburg Line without success’. The telegram angered Haig who recorded in his diary:

‘The object of this telegram is, no doubt, to save the Prime Minister in case of any failure. So I read it to mean that I can attack the Hindenburg Line if I think it right to do so. The C.I.G.S. and the Cabinet already know that my arrangements are being made to that end. If my attack is successful, I will remain on as C. in C. Ifwe fail, or our losses are excessive, I can hope for no mercy!’

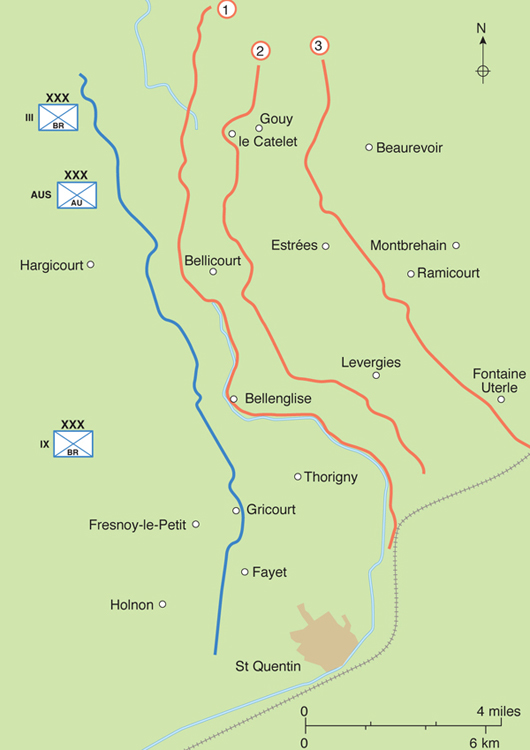

During August and September, Allied forces pushed the Germans back nearly 40km (25 miles) on an attack frontage of 113km (70 miles) - eradicating the gains of Ludendorff's Spring Offensives. Shown are the Siegfried (1), Wotan (2), and Hermann (3) Stellung of the Hindenburg Line.

With the mutinies a thing ofthe past, a column ofFrench soldiers, cheered by the recent string ofAllied victories, moves to the front lines near Amiens. This regiment is moving up to take its position in the line between Amiens and Montdidier.

Convinced of the need to press the offensive, in early September Haig took his case directly to the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Milner, who instead of supporting an offensive warned Haig that costly attacks would only compromise Britain's position if the war lingered. After their meeting, Milner reported to Lloyd George that he ‘had grave doubts whether he had got inside of D.H.'s head’, and that Haig was ‘ridiculously optimistic’. Wilson agreed and argued that the War Cabinet would have to, ‘watch this tendency & stupidity of D.H.’ Believing that Haig's optimism had once again gotten the better of him, and fearing a repetition of the Somme, Lloyd George tried for the last time to shift British forces away from the Western Front, which would have allowed the war there to become a rather American affair. However, events in France and Flanders soon proved the Prime Minister wrong and pre-empted his planning.

In his arguments with his own government, Haig had found an ally in Foch; both men believed that the opportunity to win the war was at hand and hoped to force the issue through continued attacks, while Clemenceau and Lloyd George, on the other hand, argued for conservation of strength in a war that they deemed would last into 1919 or even 1920. With the bit between their teeth, Haig and Foch both concluded, not without some rather acrimonious debate, that a converging attack by all Allied forces on the German salient in central France aimed at the critical communications hub of Mézières provided the best opportunity to dislocate German defences and provide a quick victory. In obtaining approval for their grand offensive, the formidable team of Foch and Haig steamrolled over opposition from sceptical politicians in France and London only to find that the greatest challenge to their scheme came from an unexpected source, General Pershing.

The spring and summer of 1918 had been an incredibly difficult time for the commander of the American Expeditionary Force. Pressured by Washington to form a coherent and independent American army, his increasingly desperate Allies also bombarded Pershing with pleas to send whatever forces he could to the front to stem the German tide during Ludendorff's Spring Offensives. American divisions answered the call, especially during the confused fighting in the Marne Salient, delaying Pershing's long-hoped-for separate American command. Of less notice, but perhaps of even greater importance, was the fact that, at the request of the British and French militaries, which were in desperate need of men, the US had shipped only infantry and machine-gunners to France, which left Pershing critically short on logistics, transportation and artillery. Regardless of the political and logistic difficulties, however, on 10 August, Pershing had achieved his goal with the activation of the American First Army.

Although dependent on the French and British for artillery and transport, Pershing wanted his force to play a major role in the ongoing offensives against the Germans, and after considerable deliberation opted for an assault on the German salient south of Verdun at St Mihiel. Pershing hoped that the French could lock German defending units in place at the base of the salient, while American attacks on its shoulders caused the entire German position to collapse, leading to a general advance on Metz. On 17 August, Foch had given Pershing permission to prepare for offensive operations around St Mihiel, and even promised six French divisions to aid in the undertaking. Two weeks later, though, Foch unveiled his new plan in a meeting with Pershing, and informed the American commander that the proposed US drive on St Mihiel was to be cancelled since it diverged from the planned general Allied offensive toward Mézières. Instead, Foch proposed that, as part of the general advance, the American First Army be split up to take part in assaults in the Meuse-Argonne region and in Champagne under command of French generals.

German soldiers pose with a captured French 155mm gun. The 155mm was a standard design used by the French, and later the US Army, during World War I. Later known as the ‘Long Tom’, it was upgraded and carried on in service throughout World War II.

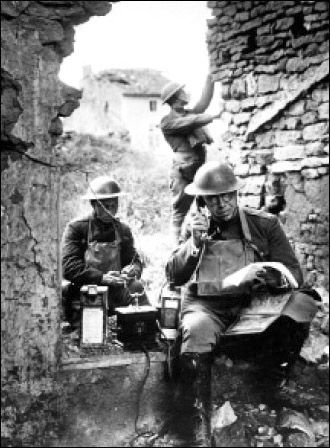

A US officer in his command post. Lacking experience, logistical and communication difficulties would continue to dog the US war effort through the remainder of the conflict.

Pershing angrily rejected the proposal, stating, ‘This virtually destroys the American army we have been trying so long to form.’ Fearing for the future of his planned grand offensive Foch pressed the issue further and Pershing responded, ‘Marshal Foch, you have no authority as Allied commander-in-chief to call upon me to yield up my command of the American army and have it scattered among the Allied forces where it will not be an American army at all.’ Adamant, Foch stood up from the table and said, ‘I must insist upon this arrangement.’ ‘Marshal Foch, you may insist all you please,’ Pershing retorted, ‘but I decline absolutely to agree to your plan. While our army will fight wherever you may decide, it will not fight except as an independent American army.’ Foch left the meeting exasperated and threatened to take the matter directly to President Wilson.

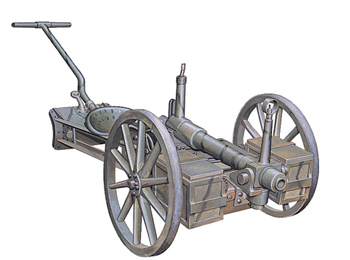

The American Browning machine gun. Capable of firing 450-600 rounds per minute, the water-cooled Browning only entered service on 26 September 1918.

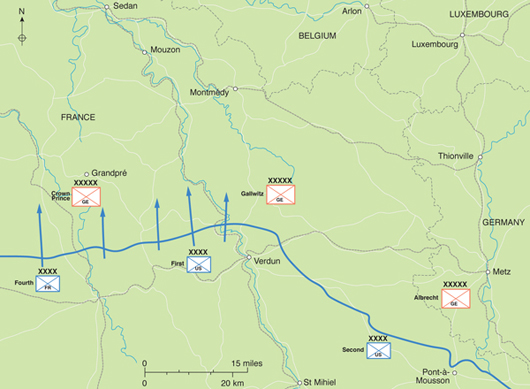

The reduction of the St Mihiel Salient, a successful operation that gave Pershing a false sense of the capabilities of the AEF. Many of the German formations were actually in the process of attempting to withdraw from the salient when the Americans attacked.

On 2 September, after Petain had attempted to mediate the dispute, Foch and Pershing met again and agreed upon a compromise. Foch allowed Pershing to choose whether US forces, acting independently, would play their role in the grand offensive by attacking in the rough terrain between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River, or in easier terrain west of the Argonne. Due in part to its proximity to existing American supply depots, Pershing chose the Meuse-Argonne. Foch then pressed Pershing to abandon his offensive at St Mihiel, but the American commander remained adamant. Although he realized full well that shifting American troops and supplies from the area of St Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne would be a difficult undertaking for the untested staff of the AEF, Pershing, without consulting his superiors, made matters immeasurably worse by insisting that American forces first fight a battle at St Mihiel and then shift northwards to prosecute an offensive at the Meuse-Argonne. The twin efforts would tax the abilities of American logisticians beyond their limits.

US troops advancing during their first major offensive operations in the Battle of St Mihiel. Although the US First Army fought admirably in the battle, it was against a disorganized enemy and harder tasks awaited the AEF in the Meuse-Argonne.

The final scheme, as agreed to by Foch, Haig and Pershing, was an example of true coalition warfare. The American effort to reduce the St Mihiel Salient, though subsidiary to the main attack, would come first, on 12 September. Only two weeks later, leaving the Americans precious little time to shift their forces more than 97km (60 miles) northwards, on 26 September American and French units would launch what Foch presumed to be the main attack between the Meuse River and Reims aimed at the seizure of Mézières, some 80km (50 miles) distant. The next day the British First and Third armies would assault simultaneously and cross the Schelde Canal towards Cambrai. On 28 September, a composite force of Belgian, British and French units, known as the Group of Armies in Flanders (GAF), would strike toward Roulers. Finally, on 29 September, the British Fourth Army, supported by the French First Army on its right, would attack into the teeth of the main Hindenburg Line system along the St Quentin Canal.

As the American First Army gathered its strength in preparation for the single largest American military undertaking since the Civil War, Ludendorff concluded that the St Mihiel Salient was too vulnerable to defend, and, on 8 September, ordered his troops there to withdraw to the defences of the Hindenburg Line. Due to delays, though, General Max von Gallwitz, in command of German forces in the area, had only just begun the complicated operation when, on 12 September, 16 American divisions struck on both flanks of the salient. Supported by the fire of 3010 artillery pieces, of which 1681 were manned by Americans and 1329 by the French, American forces crashed through the thinly held German front lines. Although some German formations resisted the advance, most simply tried to complete their withdrawal from the salient before the advancing Americans cut them off. By 16 September, the American First Army had scored a remarkable victory, reducing the St Mihiel Salient and capturing 15,000 German prisoners and 450 artillery pieces at the cost of only 7000 US casualties.

To Pershing, St Mihiel vindicated both his long fight to found an independent American military force and his tactical belief in more open methods of warfare. In his final report on the battle Pershing wrote:

‘The material results of the victory achieved were very important. An American army was an accomplished fact, and the enemy had felt its power. No form of propaganda could overcome the depressing effect on the morale of the enemy of this demonstration of our ability to organize a large American force and drive it successfully through his defenses. It gave our troops implicit confidence in their superiority and raised their morale to the highest pitch.

‘For the first time wire entanglements ceased to be regarded as impassable barriers. ... Our divisions concluded the attack with such small losses and in such high spirits that without the usual rest they were immediately available for employment in heavy fighting in a new theater of operations.’

Although the reduction of the St Mihiel Salient had been an important victory, observers within the French, British and even the American military noted that it had come against a German force bent on retreat, and that a skilled and more experienced army might have performed even better. General Robert Lee Bullard, eventually promoted to command the American Second Army, remarked: ‘St. Mihiel was given an importance which posterity will not concede it. Germany had begun to withdraw. She had her weaker divisions, young men and old and Austro-Hungarians. The operation fell short of expectations.’

In the afterglow of St Mihiel, though, Pershing must have thought that attacks in World War I were not as difficult as the French and British experience of past years had led him to believe. Confident in his abilities and in the readiness of his army, Pershing began to shift forces northwards to the Meuse-Argonne, where, in the next American offensive, the Germans would choose to stand and fight - altering Pershing's opinion of World War I.

Even without the aid of trenches, German defenders, as these pictured firing their minenwerfer at St Mihiel, could inflict heavy casualties on attacking forces through the skilful use of blocking positions and machine guns.

The shift of American forces from St Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne front was a massive undertaking, but in 10 days, under the direction of Colonel George C. Marshall, US and French forces succeeded in transferring some 428,000 men, 90,000 horses, 3980 artillery pieces and 816,466 tonnes (900,000 tons) of supplies, all under great secrecy. With the French Fourth Army on his left flank, Pershing, on a 32km (20-mile) front, gathered I, III and V corps and enjoyed an eight-to-one superiority in men and a ten-to-one superiority in artillery over the defending Germans. In light of his recent success at St Mihiel, the American commander planned to break through three successive belts of German defences and advance 16km (10 miles) all in one great push, after which the American First Army would halt for only a short period before pressing on toward Mézières.

The slow advance of French and American forces during the Meuse-Argonne campaign from September to November 1918. The Americans in particular struggled in the face of a well organized defensive system and determined opposition from German forces.

Pershing's planning, though, was hopelessly optimistic, especially considering the fact that the AEF basically remained an untried force, with four of the nine divisions slated to take part in the opening assault having had no previous combat experience. Also the Germans expected an attack in the area, having their suspicions confirmed by French deserters, and prepared a defence in depth based on a system of machine-gun nests and strongpoints that were now so familiar to British and French forces, but were new to the Americans. General Hugh Drum, Pershing's chief of staff, commented concerning the German defences, ‘This was the most ideal defensive position I have ever seen or read about. Nature had provided for flank and crossfire to the utmost in addition to concealment.’ As evidenced by Drum's remarks, the terrain also worked against the attackers, canalizing any advance into gaps between the Meuse River, the Montfaucon Hills and the Argonne Forest. General Hunter Liggett, in command of the American I Corps, termed the area a ‘natural fortress ... beside which the Wilderness in which Grant fought Lee was a park’.

The Colt New Service revolver, a .45-calibre handgun of which 150,000 were produced during World War I. This weapon was originally introduced in 1909 after the US Army's experiences in the Philippines. It was improved for wartime use as the M1917.

After a short artillery barrage, on 26 September, the American First Army and French Fourth Army launched the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Shocked by the sheer scale of the bombardment and badly outnumbered, the German defenders initially wavered, leading to an advance by Allied forces of nearly six kilometres (four miles). Spearheaded bythe American 79th Division, filled with soldiers mainly from the Washington DC area, the advance plunged into the Montfaucon Hills, only to stall amid a wilderness of German strongpoints. Without the benefit of battlefield experience, American units often advanced in waves, and played to the strengths of the German defensive system as their British and French allies had in years past. Suffering from severe communication problems, American units also often became intermingled, causing untold confusion. Although some units renewed their forward movement on 27 September, the attack had fallen apart so completely that the German commander, General von Gallwitz, later remarked that, ‘on the 27th and 28th we had no more worries’.

German troops digging fortifications in the Argonne region. After initial successes, the Franco-American advance became bogged down by the the difficult ground and the tenacity of its German defenders.

On 2 October 1918, as part of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, elements of six companies of the 308th Infantry Regiment, one company of the 307th and two companies of the 306th Machine Gun Battalion (about 600 men in all) outpaced the other advancing forces only to find themselves surrounded and cut off near Charlevaux Mill. Major Charles Whittlesey, as the senior officer present, took command of the composite group, which became known as the lost battalion.

Caught in a shrinking perimeter without water, and under constant attack by the Germans, the situation for Whittlesey and his men quickly became desperate. Making matters worse, on the second day of their ordeal, the lost battalion also came under fire from friendly artillery. With no means of direct communication, Whittlesey resorted to the use of his last remaining carrier pigeon, Cher Ami, releasing the bird with the message, ‘Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake stop it.’ Whittlesey was crestfallen when the bird merely flew into the branches of a nearby tree and perched. After a few minutes, a private clambered up the tree and scolded the bird until it flew off. Cher Ami lost a leg and an eye en route, but eventually reached divisional headquarters with its message, and received the Croix de Guerre from the French Government.

Even though the American barrage was stopped and the 50th Aero Squadron attempted the first air resupply in battle, the men of the lost battalion were in desperate straits, with supplies running low and the dead and wounded piling up all around Demonstrating the bravery of the men, one private, who was shot through the stomach, was informed that his groaning would only attract more enemy fire. The private replied, ‘It pains like hell, but I’ll keep as quiet as I can.’ He made no sound and died 30 minutes later.

A photograph depicting the members of the ill fated ‘lost battalion’.

It was the afternoon of 8 October before an attack by the American 82nd Division led to a link-up with the lost battalion. Having refused several German demands of surrender, Whittlesey and 193 other survivors, most of them wounded, made their way to safety after 104 hours without food or medical attention. One who witnessed their return recorded: ‘I couldn’t say anything to them. There was nothing to say, anyway. It made your heart jump up in your throat just to look at them. Their faces told the whole story of the fight.’

Attempting to take the measure of its new foe, the German Fifth Army quickly produced an assessment of American forces, and forwarded the document to an anxious Ludendorff. While praising the bravery and stamina of the individual American soldier, the document judged American staff and liaison work to be ‘inadequate’. Interrogations of American prisoners revealed most to be ‘naive in military and political matters’, who followed their officers in an effort to crush ‘German militarism’. The interrogations also revealed that the difficulties experienced in the fighting at the Meuse-Argonne had come as a surprise to the untested Americans, who had previously seen the war as a ‘happy picnic’. Although Ludendorff took heart at the relative inexperience and rather amateurish tactics of the American First Army, he also realized both that Pershing would learn from his mistakes and that the sheer weight of American numbers would quickly become a telling factor. Sensing that the advance in the Meuse-Argonne area was the centrepiece of the Allied attack plan, and fearing a steady improvement on the part of his American foe, Ludendorff ordered six additional German divisions to the area in an effort to blunt the offensive.

Meanwhile, the scene behind the lines of the American First Army was one of utter confusion. Traffic jams snarled the roadways, one lasting for 12 hours, which made supplying units in the field nearly impossible. Facing stiffening German resistance, with his own staff nearing a logistical breakdown, and with his grandiose plan in tatters, Pershing halted the offensive on 29 September to regroup and prepare for a renewed assault. Incensed that the lynchpin effort of his grand offensive had met with such little success, Foch placed much of the blame on the failures of the French Fourth Army, which had so much more experience than the Americans. Clemenceau, though, had no such charity toward Pershing and his men, having visited the American headquarters on 29 September, only to get caught up in the massive traffic jam behind the American lines. Convinced that the American staff was incompetent, and that its failings would not only cost French lives but also prolong the war, Clemenceau launched into a criticism of the American commander that nearly led to a breakdown of Allied command.

While the Franco-American assault at the Meuse-Argonne sputtered, to the north the BEF achieved a much greater level of success. On 27 September, Currie’s Canadian Corps and elements of Byng’s British Third Army assaulted the formidable German defensive system anchored on the Canal du Nord outside of Cambrai. Under cover of a punishing and accurate barrage, the Canadians clambered through and over the obstacle of the partly filled canal, and assaulted the German defensive system that lay just beyond. Unlike the Americans in the Montfaucon Hills, the Canadians and British had often faced the strongpoints that typified the German defensive system, and utilized specially trained and equipped engineer units both to destroy centres of resistance and maintain the advance. Although the units of Byng’s Third Army often lagged behind the hard-charging Canadians, together both forces surpassed their final goals, and in many places reached the Schelde River. After only two days of fighting the Canadian Corps and the British Third Army had driven a wedge 19km (12 miles) wide and 10km (six miles) deep into the German defences, captured 10,000 prisoners and made Cambrai useless as a railhead for the Germans.

American Doughboys pick their way through the heavily wooded terrain of the Argonne, which served to shatter the cohesion of Allied advances in the area. The American failure to press through was met by a barrage of criticism from Allied politicians.

The German 37mm anti-tank gun was introduced at the end of the Great War as a counter to the Allied use of armour. The weapon fired a 455g (one-pound) armour-piercing explosive shell, which could penetrate 15mm (3/5in) of armour at 200m (220 yards).

As Ludendorff struggled to rush reserves to the Meuse-Argonne and to Cambrai, on 28 September, the GAF, based around the strength of the British Second Army, launched its assault on the familiar battlefields of Flanders outside Ypres. Unable to achieve surprise due to German observation of the battlefield from the ridges surrounding Ypres, the ten divisions of Plumer’s Second Army, aided by Belgian forces under the command of King Albert, weathered a German counterbarrage before going over the top. After the assault, the five understrength German defending divisions quickly gave way, which allowed British and Belgian forces to advance 14km (nine miles) in two days, taking over 2000 prisoners. For Plumer the victory was cathartic, with his force taking more territory in one short battle than it had in the entire Third Battle of Ypres, seizing the entire Passchendaele Ridge and threatening Roulers.

Conscious that they were losing the war, the Germans turned to more desperate forms of propaganda, some aimed at what they hoped would be a weak point in the Allied structure - the place of African-Americans in the US Army. One German leaflet dropped to a segregated black unit read:

‘Hello boys, what are you dong over here? Fighting the Germans? Why? Have they ever done you any harm? Of course some white folks and the lying English-American papers told you that the Germans ought to be wiped out for the sake of humanity and Democracy. What is Democracy?... Do you enjoy the same rights as the white people do in America, the land of freedom and Democracy, or are you rather treated over there as second class citizens? Can you get into a restaurant where white people dine? Can you get a seat in a theatre where white people sit? Can you get a seat or a berth in a railroad car, or can you even ride in the South in the same streetcar as white people?... Now all this is entirely different in Germany, where they do like coloured people; where they treat them as gentlemen. ... Don’t allow ... [the Americans] to use you as cannon fodder. ... Throw ... [your weapon away] and come over to the German lines. You will find friends who will help you.’

Regardless of the German efforts, though, there were not any significant numbers of desertions from African-American units.

The British Fourth Army’s assault on the Hindenburg Line on 29 September 1918. Rawlinson’s aim was to break through the main line (1), the support system (2) and, finally, the reserve system (3).

The avalanche of Allied offensives unhinged Ludendorff, who suffered some form of mental breakdown. He had reason to be worried, for in August alone the Germans had lost 228,100 men, of whom 110,000 had deserted. The number of divisions in the German Army had fallen from a high of roughly 200 in March to only 125 by September, of which only 47 were deemed fit for combat. The Allies, by comparison, fielded 211 divisions and could count on the arrival of more and more American soldiers as the war continued. At a meeting of the German general staff, Ludendorff, recovering somewhat from his episode, informed all present that the German Army was, ‘finished; the war could no longer be won; rather the final defeat was probably inescapably at hand’. With the burgeoning strength of the AEF, Ludendorff opined that the Allies would soon gain ‘a great victory, a breakthrough in grand style’. In an effort to save his beloved military from inevitable and catastrophic defeat, Ludendorff advised the Kaiser to, ‘request an armistice without any hesitation’. Although Ludendorff could hardly have believed it at the time, the worst was yet to come.

The final, and most important, portion of the Allied offensive fell to Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, aided by the French First Army, and involved an assault against the might of the Hindenburg Line along the St Quentin Canal. The German defences in the area were the strongest faced yet by the Allies on the Western Front, and were believed by many to be impervious to both tank and infantry assault. The southern portion of the German lines was anchored on the obstacle of the St Quentin Canal, which was 11m (35ft) wide, contained mud of over two metres (six feet) in depth and was guarded by barbed-wire-studded sheer banks ofnearly 15m (50ft) in height. Rows of concrete pillboxes, in three distinct lines, stood guard on both the east and west banks of the canal, forming a total defensive network of over 5486m (6000 yards) in depth.

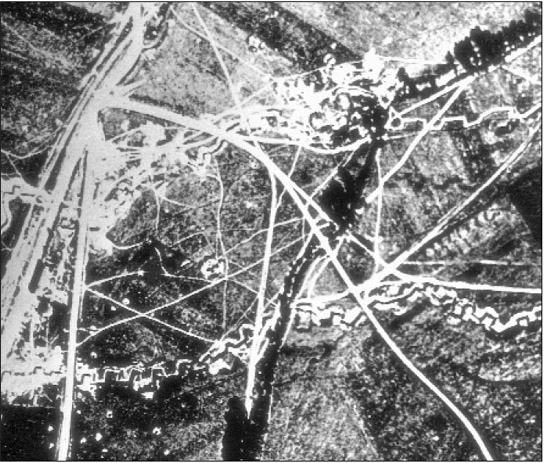

An aerial view of part of the formidable German Hindenburg Line defensive system, which Ludendorff had hoped would hold throughout the winter - a hope dashed by Rawlinson’s Fourth Army on 29 September successfully crossing the St Quentin Canal.

Although the defences seemed nearly impregnable, there were reasons for optimism within the Fourth Army. On the northern portion of the front, the St Quentin Canal ran through the 5486m (6000-yard) Bellicourt Tunnel, which essentially provided British planners with a broad, ready-made bridge. While the Germans had recognized the tunnel sector as the potential Achilles heel of the defensive network and had prepared accordingly, Rawlinson still hoped to make the sector his main avenue of advance. Additionally, while attacking and defending forces for the coming battle were roughly equal in number, the morale of the badly battered German forces was sagging. The BEF also had captured detailed plans for the defences of the St Quentin Canal area, prompting Rawlinson’s chief of staff to remark, ‘It has fallen to the lot of few commanders to be provided with such detailed information as to the nature of the enemy’s defences.’

Highlighting the increasing importance of Dominion forces to the BEF, General Monash and his staff at the Australian Corps undertook much of the tactical planning for the coming battle. One problem, though, was that much of the Australian Corps was not available for the operation, having been withdrawn from the front after days of exhausting battle. In need of two strong divisions to replace the Australian 1st and 4th divisions, Monash chose the American 27th and 30th divisions, the last two American divisions serving with the BEF. Impressed with the strength and eagerness of the US units, Monash remained concerned about American operational readiness, and accordingly placed the Americans under overall control of the Australian Corps.

Monash’s plan called for the American divisions to advance, under cover of a heavy artillery barrage and aided by tanks, over 3658m (4000 yards) into the German defensive system in the tunnel sector, and then for two Australian divisions to leapfrog through the breech created in the German defences by the Americans. Rawlinson, though, argued both that Monash’s plan would result in a vulnerable advance on too narrow an attack frontage, and that it was overly reliant on almost untested American units. Accordingly, Rawlinson extended the attack frontage, adding an assault by IX Corps across the St Quentin Canal. The commander of IX Corps, LieutenantGeneral Walter Braithwaite, had made the extension of the attack possible by suggesting that his men could cross the canal by using lifebelts, portable boats and ropes and ladders. Although Rawlinson judged the scheme to be risky, he concluded that a single division, the 46th, just might be able to force its way across the canal using such methods and believed that its attack might catch the Germans unaware.

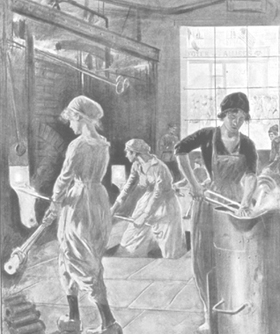

World War I proved to be a watershed in the lives of women in many western nations. The Victorian ideal for middle- and upper-class women involved home life, and caring for their husbands and families. However, the voracious demand of World War I for military manpower resulted in women replacing men in much of the workforce, taking jobs ranging from working in munitions factories to tilling the soil. In Britain alone, World War I saw two million women join the workforce for the first time. Although at the close of the conflict many women lost their jobs to returning soldiers, ideas about women and their place in society had already been changed. With material needed for military uniforms, women got by with less fabric, and those involved in factory work for the first time began to opt for trousers rather than dresses. Many young women earned a real wage for the first time during the war, and lived on their own or with other single women, experiencing previously unheard of levels of independence. Some of the more daring women took to smoking in public and even frequented pubs, something unheard of in the Victorian world.

From joining the workforce to wearing trousers, World War I greatly impacted the lives of women in the combatant nations.

The bombardment that accompanied the attack of British, Australian, American and French forces on 29 September, though only roughly equal in weight to that of the first day of the Somme, was both accurate and lethal, silencing German defences in many areas of the front. In the north, however, the attack almost immediately stalled. The American 27th Division, like most units taking part in the attack, had been involved in a variety of smaller operations designed to seize important tactical features in the run-up to the main offensive. However, the 27th had failed to reach its jumping-off point, and its divisional commander feared that pockets of American troops were holding out, marooned in German lines. Fearing for the lives of his stranded men, the 27th commander insisted that the artillery barrage begin 914m (1000 yards) to the east of the start line, meaning that, when the men of the 27th went over the top at 5.50am, they faced untouched German defences. Although the unit fought bravely, it quickly became entangled with the Australian 3rd Division, which was meant to leapfrog through American gains. With little artillery support, the confused and intertwined units failed to advance into the main system of the Hindenburg Line.

British troops assaulting a battered German strongpoint in the Hindenburg Line. The Fourth Army, spearheaded by the Australian and American divisions of the Australian Corps, had forced a way through the much-vaunted German defensive position in a single day.

‘Tomorrow we are to take part in the greatest and most important battle that we have yet been in, for we are to assault the Hindenburg Line, the famous trench system which the Germans have boasted is impregnable.’

Captain Francis Fairweather, Australian Corps, 28 September 1918

Further south, though, the American 30th Division achieved a much greater level of success. Without the same concerns that plagued the 27th Division’s commander, the artillery support for the 30th Division was devastating and seemingly shocked many of the German defenders in the area into relative inaction. By noon the Americans had taken Bellicourt and were even advancing into the supporting defences behind the main Hindenburg Line system. Although the 5th Australian Division successfully passed through the advance units of Americans, little else was gained that day, with the Australians facing concerted German counterattacks and enfilade fire from German lines on their left flank, where the American 27th and Australian 3rd divisions had failed to keep pace.

The main advance of the day fell to the British 46th Division, which had taken part in the attack only at Rawlinson’s insistence. The artillery support provided by IX Corps for the assault was overwhelming: on one 457m (500-yard) stretch of front, there were 54 18-pounder field guns firing two rounds per minute, and 18 4.5in field howitzers firing one round per minute. While the 46th Division moved forwards, then, every minute 126 shells were falling on the 457m (500- yard) attack frontage in advance of the infantry. The damage done by the bombardment also collapsed the banks of the St Quentin Canal, making it easier for the men of the 46th to scramble down and to rush across the water obstacle utilizing their flotation devices. Bursting out of a thick fog, the men of the 46th Division caught the German defenders, who thought that the canal provided them with an impregnable defensive line, by surprise.

Reeling with shock, the German defenders fell back behind the canal, where the offensive halted for three hours while the artillery pounded away at the next German lines and fresh British reserves joined the attack. At 11.20am, the attack began anew and units of the 46th punched through the main Hindenburg Line by 3pm, allowing the British 3rd Division to pass through and assault the supporting lines. By nightfall it had become apparent that the Fourth Army had achieved a stunning victory. In one day American, Australian and British troops had broken through the Hindenburg Line and the Hindenburg Support Line, overthrowing the most important German defensive system on the Western Front. Advancing to a depth of 5486m (6000 yards) on a frontage of 9144m (10,000 yards), the Allied forces not only had ruptured the German defences but also had captured 5100 prisoners and 90 artillery pieces. In a truly international battle, the Fourth Army had achieved one of the greatest successes of the war on the Western Front. With the Allies advancing everywhere, and with their greatest system of defences, upon which they had staked so much hope, breached, the German military realized that the end of the conflict was near.

As the German Army continued its fighting retreat, morale among the German troops reached a new low. Fresh units moving toward the front were even greeted by the fabled Prussian Guards with cries of ‘strike breakers’ and ‘war prolongers’. Although the German Army did not dissolve into a state of mutiny, the signs that it was nearing the end of its ability to resist were everywhere. The most compelling evidence of an impending collapse of military discipline could be found in the crowds of shirkers and slackers milling behind the German lines - loose groupings of soldiers estimated to number between 750,000 and one million for the last two months of the conflict. Facing continued battering by strengthening Allied forces, and considering the increasingly fragile nature of his own military, Major von Leeb of Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht, spoke for many when he stated, ‘The campaign has been lost, the military mistakes [made] have now come home to roost’.

On 1 October, Ludendorff chaired an operational review of the war that not only reached a conclusion similar to that of von Leeb but also had chilling differences. With his hopes for holding at the Hindenburg Line dashed in a single day by Rawlinson’s offensive, Ludendorff opened the meeting with a statement that stunned those present into silence: ‘The OHL and the German Army are finished’; the war could no longer be won; rather, the final defeat was probably inescapably at hand. Bulgaria had fallen, and both Austria-Hungary and Turkey were at the very end of their ability to resist, leaving Germany alone to face the might of nearly three million fresh American troops. Ludendorff then admitted the sagging morale of the German army, remarking that he could ‘no longer rely on the troops’. With defeat looming on every front, Ludendorff announced that he was going to advise the Kaiser to ‘request an armistice without any hesitation’.

German troops near Reims. Although the Germans fought fiercely in defence of the Hindenburg Line and the Meuse-Argonne, the continuous Allied advances led many to a sense of desperation.

Amid protests from the assembled staff officers, Ludendorff drove his point home with conviction, repeating his refrain that further ‘prosecution of the war was senseless’. Ludendorff then went on to demonstrate an amazing motivation for his conclusions - the war had to come to a ‘quick end’ to salvage the institution that he most loved, the German Army, from destruction. Instead of blaming his own failed tactics, or indeed the military itself for Germany’s impending defeat, Ludendorff blamed the German nation, which he believed had been found wanting under the pressures of war. Instead of fighting to the end and being destroyed in the process, the German Army, which Ludendorff believed to be the heart of the German state, had to survive and eventually redeem the shattered German body politic. Closing the briefing Ludendorff made his motivations clear, suggesting that the Kaiser be asked to bring to power ‘those circles which we mainly have to thank that things have come to this’. In other words Ludendorff hoped that the liberals and socialists would be brought into power to bear the burden and the blame for bringing the failed war to an end. Ludendorff concluded, ‘They can now clean up the mess for which they are responsible.’

General Erich Ludendorff. As First Quartermaster General, Ludendorff effectively controlled Germany’s military planning on the Western Front. Although his great Spring Offensives had been tactical masterpieces, their lack of strategic coordination possibly cost Germany the conflict.

Several of the staff officers present broke down into tears as the enormity of the moment became clear -Germany had been defeated in World War I and all of the sacrifice and loss had been in vain. Amid the tears, though, nobody could have realized the powerful connection between Ludendorff’s words and another, greater, war that would soon engulf the world. Ludendorff had laid the foundations for the ‘stab-in-the-back’ legend that was to dominate German politics in the inter-war period; a legend that was fundamental to the rise to power of Adolf Hitler. Central to the legend was the idea that the German Army had not been defeated in World War I. It was holding out steadfastly in France and in Russia, only to have the home front collapse amid a welter of communist- and socialist-inspired uprisings. The gallant German Army had been stabbed in the back by men and women not brave enough to join the fight for survival. The myth would prove a valuable tool in the hands of demagogues; however, it was just that - a myth. Under hammer blows from the Allies, the German Army was being comprehensively defeated. As Ludendorff knew, its only hope for survival was to quit the war before its destruction was complete. Instead of fighting on for its honour, the German Army chose to capitulate, putting its own survival before that of the nation.