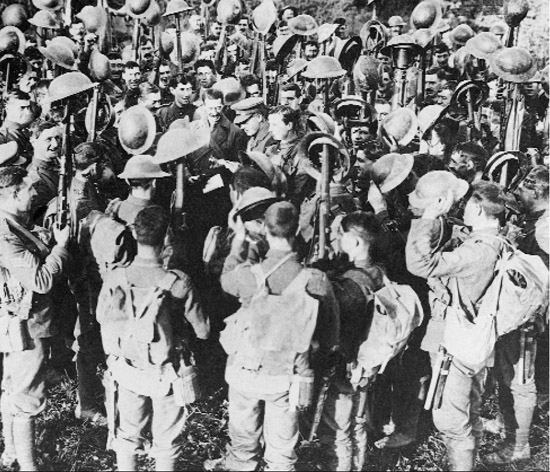

After years of bloody warfare, the signing of the armistice on 11 November 1918 was the cause for jubilation among Allied ranks, the culmination of four long years of struggle on the Western Front.

As Germany slowly imploded, the Allies pressed ever onwards on the Western Front, forcing the German Government to sign an armistice, which brought the Great War to a close on 11 November 1918. With their army still in the field in France, though, many Germans did not admit a true military defeat, dooming the world to fight a second world war 20 years later.

Max von Baden took over as Chancellor of Germany on the evening of 3 October, and, due in large measure to the pessimism of Ludendorff, within 48 hours he had sent a formal note to President Wilson through Swiss intermediaries which read: ‘The German government requests the President of the United States to take in hand the restoration of peace, acquaint all the belligerent states of this request, and invite them to send plenipotentiaries for the purpose of opening peace negotiations.’ The diplomatic note then went on to mark Wilson’s own Fourteen Points (see over) as a basis for negotiations and concluded, ‘With a view to avoiding further bloodshed, the German Government requests the immediate conclusion of an armistice on land and sea.’

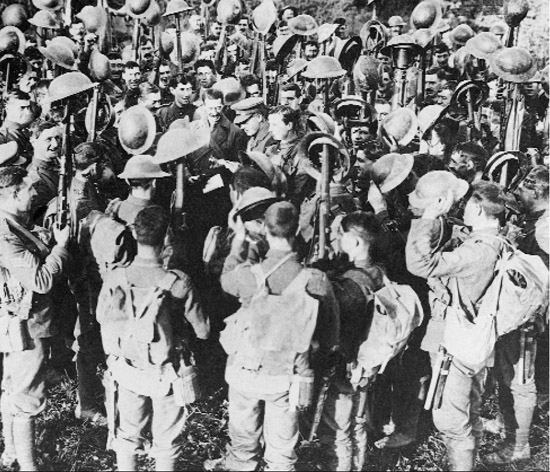

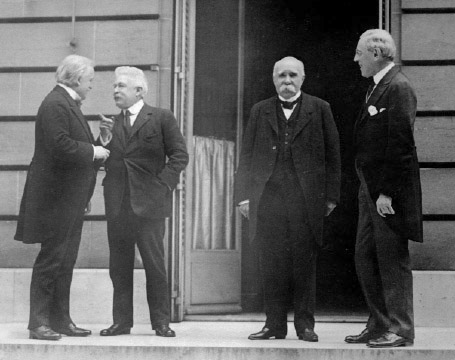

American President Woodrow Wilson, whose Fourteen Points placed him at odds with the leaders of France and Britain, who were more stern in their demands for peace with Germany.

Needing time to consider the implications of the German note, Wilson’s initial reply simply requested clarification of Imperial Germany’s acceptance of the Fourteen Points. The President’s measured response was a cause for celebration among the ruling class of Germany, many of whom dared to hope that they could play Wilson off against Lloyd George and Clemenceau to achieve a more lenient peace, one that might even allow Germany to retain German-speaking areas of the Ukraine and Alsace Lorraine. Among the French military, however, Wilson’s response touched off a furious reaction. Fearing that America would withdraw from the conflict before a true victory had been achieved, one French officer asked his American liaison, ‘Does your President realize with what swine he is dealing? They’ll fool him if he is not very, very canny.’ Another French officer opined that it was ‘unthinkable’ to deal with the Germans so long as they occupied French or Belgian soil. On 14 October, though, Wilson sent his first detailed response to the German call for negotiations, the tenor of which dashed German hopes and allayed French fears. The American response demanded ‘absolutely satisfactory safeguards and guarantees of the maintenance of the present military supremacy of the armies of the United States and the Allies in the field’, and vowed to leave conditions of any armistice to the ‘judgment and advice of the military advisors of the Government of the United States and the Allied Governments’.

Outlined by President Woodrow Wilson in a speech on 8 January 1918, the Fourteen Points were designed both to end World War I and to prevent future conflicts. Although France and Britain rejected aspects of the Fourteen Points, Wilson’s principles became a guiding force behind the Versailles negotiations. The Fourteen Points included:

• Open covenants of peace; no secret agreements.

• Freedom of the seas

• The removal of economic barriers

• Guarantees of the reduction of armaments

• Adjustment of all colonial claims, with the interests of the subject populations being equal with the claims of governments

• Evacuation of all Russian territory

• Restoration of Belgian sovereignty

• Restoration of all French territory including Alsace Lorraine

• Readjustment of Italian frontiers along national lines

• Opportunity for the autonomous development for the people of Austria-Hungary

• Evacuation of occupying forces from Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, with relations of the Balkan states to be decided along lines of nationality

• Opportunity for autonomous development for non-Turkish peoples within the Ottoman Empire. The Dardanelles to be free for all shipping

• Creation of an independent state of Poland with access to the sea

• Formation of a general assembly of nations with the aim of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states.

Although a measure of cold water had been thrown on the German hopes for a lenient negotiated peace, Ludendorff had once again regained a measure of composure after the shock of the British Fourth Army’s overthrow of the Hindenburg Line. To the south the Franco-American drive in the Meuse-Argonne remained stalled, while to the north the advance of the GAF had also ground to a halt. Although Rawlinson’s men continued to press forwards, the flanks of the great Allied offensive had ceased to advance, and Ludendorff no longer feared an immediate military catastrophe. In a meeting with Prince Max, Ludendorff stated that it had become apparent that the strength of the enemy offensive was ‘falling off’. Ludendorff then went on to add that under the new strategic circumstances Germanycould continue the war for another year by withdrawing to more defensible lines and wrest a more favourable peace from the Allies in 1919.

German defenders in the open fighting that came to typify the final, semi-mobile phase of World War Ion the Western Front. Increasingly, aircraft became used in a ground-attack role in the final months of the war, a process made easier for the Allies by the creation of the Royal Air Force in April 1918.

With both wings of his grand offensive stalled, a furious Foch both sought a solution to the tactical dilemma and attempted to prod those whom he felt were most responsible for the delay. Clearly surprised that the British Fourth Army, which enjoyed the least in the way of numerical superiority and had faced the strongest German defences, had become the de facto spearhead of the Allied offensive, Foch tried to get his own French forces moving faster and sent a scathing note to Pétain, which read: ‘Yesterday ... we witnessed a battle that was not commanded, a battle that was not pushed, a battle that was not brought together ... and in consequence a battle in which there was no exploitation of the results obtained.’

While Foch levelled criticism at his own forces, others were quick to single out the American First Army, which had been slated to play the major role in the attack but instead had succumbed to both logistic and tactical difficulties, as the cause of the delay. On 1 October Haig commented:

‘Reports from Americans (west of Meuse) ... state that their roads and communications are so blocked that the offensive has had to stop and cannot be recommenced for four or five days. What very valuable days are being lost! All this is the result of inexperience and ignorance on the part of... [the American staff] of the needs of a modern attacking force.’

For his part Sir Henry Wilson made his feelings clear regarding American failings in a diary entry: ‘The state of chaos the fool [Pershing] has got his troops into down in the Argonne is indescribable.’ In a later diary entry Wilson called Pershing a ‘vain ignorant weak ASS’.

Clemenceau and Pétain also saw Pershing’s handling of American forces as ‘risking disaster’ and placed great pressure on Foch to lessen the American’s control over the battle and even threatened to complain about the situation directly to President Wilson. Because of the increasing pressure, on 11 October Foch sent General Maxime Weygand to Pershing’s headquarters with a letter relieving him of command. Pershing refused to comply and instead drove to Foch’s headquarters for direct talks. In the meeting, which threatened to unhinge Allied unity, Foch got right to the point and said to Pershing, ‘On all other parts of the front the advances are very marked. The Americans are not progressing as rapidly’. Pershing replied that his army faced both stern German resistance and difficult terrain. Foch countered that he judged those under his command only by results and added, ‘I am aware of the terrain. You chose the Argonne and I allowed you to attack there.’ With Franco-American cooperation hanging by a thread, in the end Pershing and Foch put their differences aside and agreed to the formation of the Second American Army, under the command of General Robert Lee Bullard, a move that both elevated Pershing to the level of an army group commander and was designed to lessen the staff and logistic problems that plagued American forces.

A lieutenant in the Tank Corps in France, wearing protective face gear for use in the dangerous interior environment of the late model British tanks. Enemy small-arms fire could cause splinters to fly off the inside of the armour plating.

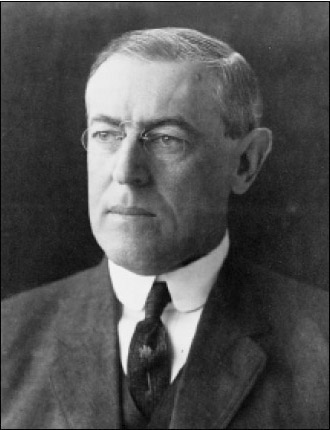

While he dealt with the diplomatic difficulties of conducting a coalition war, Foch also had to reinvigorate the Allied offensive and keep the Germans from pulling back and creating coherent lines of defence near to the Franco-German border. After considering various plans, Foch settled on a scheme of three converging offensives, in which the GAF would renew its drive towards Ghent, while Franco-American forces advanced on the right of the Allied line in the direction of Mézières. In a tacit acknowledgement of the success gained by British forces, and the corresponding lack of forwards movement by French and American units, Foch made a British attack in the centre of the Allied lines aimed at Maubeuge the centrepiece of his new grand offensive.

Plainly pleased that the BEF was now considered the most reliable Allied military force, Haig directed Byng’s Third Army and Rawlinson’s Fourth Army to attack in concert near Cambrai. Utilizing the heaviest artillery barrage since their successful attack of 27 September, British and Dominion forces went over the top on 8 October against only a smattering of defensive artillery fire from the outmatched Germans. Supported by tanks, the men of Third Army punctured the defences of the German Beaurevoir Line, advancing 4572m (5000 yards) and capturing over 2700 prisoners. On the British right flank, supported by the French First Army, Rawlinson’s force advanced 5486m (6000 yards) on most of its front, took the villages of Serain and Mericourt and captured 4000 prisoners and 40 guns. The fact that the German prisoners were identified as having come from 15 different divisions was taken by British intelligence officers as further indication of the administrative collapse of the German Army.

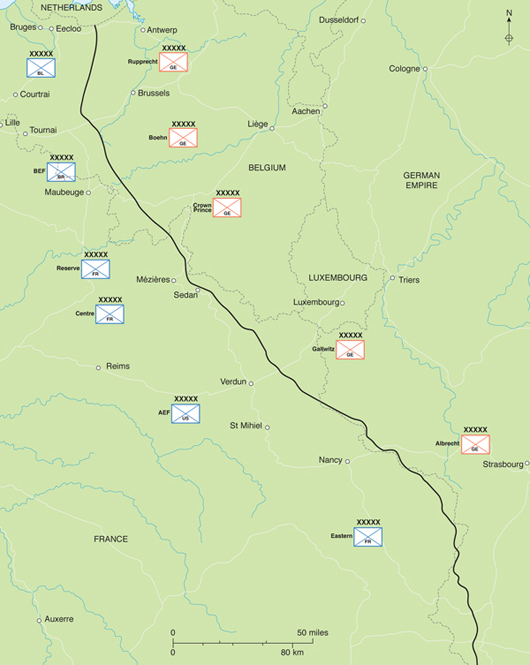

The final Allied advances on the Western Front from late September through to the armistice. As generalissimo of the Allied forces, Marshal Foch organized a series of interconnected offensives that kept the Germans under pressure the length of the Western Front.

The defeat at Cambrai was a heavy blow for Ludendorff, for the Allies had rekindled their forwards movement before he had been able to establish a coherent defensive line. Recognizing that the BEF advance had made Cambrai untenable, Ludendorff ordered a withdrawal in the region to hastily constructed new defences dubbed the Hermann Position. With the Canadian Corps leading the way, the British Third and Fourth armies harried the retreating Germans until 13 October when the lines solidified along the Selle River.

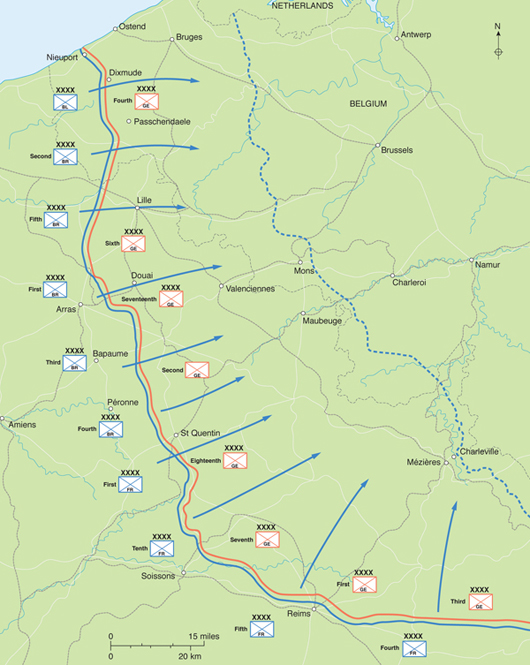

The Australians, here shown advancing, and the Canadians were renowned as among the best shock troops in the BEF during the battles of the Hundred Days. Both were organized into their own corps and used to spearhead many of the BEF’s set-piece attacks.

As the BEF’s advance in the centre slowed, Foch unleashed Allied forces on both the left and right wings of the line, in an attempt both to keep the Germans guessing and retain the all-important initiative. In the north the GAF, spearheaded by Plumer’s British Second Army, crashed through the German lines on 14 October with an ease that the historian of the British 36th Division remarked, ‘would have seemed impossible a year ago’. Although the British received concentrated fire from a few machine-gun nests, much of the German Fourth Army’s infantry offered only cursory resistance to the onrushing attackers. By evening, the British Second Army had advanced nearly six kilometres (four miles) on a broad front and had captured 6000 prisoners and 50 artillery pieces. With the continuing support of the Belgians, who a British staff member remarked had ‘fought magnificently’, Second Army resumed its advance with equal vigour the following day.

As the front lines crumbled around them, many Germans continued to fight bravely, while others for the first time began to surrender in record numbers. On the home front civil unrest was increasing, while the German Navy was edging towards mutiny in its home ports.

As the GAF surged forward, Ludendorff chose again to trade space for time in an effort to keep his doomed military from fighting at too great a disadvantage. Abandoning the Belgian coast, a strategic goal that the British had sought in vain for nearly five years, on 15 October, the Germans withdrew to the natural defensive barrier of the Schelde River, joining the Hermann Position near Valenciennes. Farther south, German forces withdrew in advance of a suspected French offensive to the Hunding and Brunhild positions between Guise and Rethel.

While the GAF made great gains in the north, on 14 October, the French and newly reorganized American forces launched an attack in the Meuse-Argonne area that finally captured Romagne, the goal that Pershing had set as the main objective for the first day of his 26 September offensive. Ludendorff still saw the Franco-American axis of advance to be critical and threw his best remaining units into the defence of what was known as the Kriemhilde Line. Making the importance of holding the line in the Meuse-Argonne clear, Ludendorff ordered General Max von Gallwitz, the army group commander in the area, to ‘put into the fighting front every unit that is at all fit for use in battle’. Thus, although Pershing saw the seizure of Romagne as an event the importance of which could ‘hardly be overestimated’, Foch was once again left to fume that the Americans, along with the French Fourth Army, struggled to make further headway.

Perhaps stung that it had done only little in a war its creation had done much to cause, the leadership of the German High Seas Fleet sought to reclaim its honour by facing the British Grand Fleet in battle as World War I neared its end. Admiral Rheinhard Scheer did his best to convince his sailors to fight stating, ‘An honourable battle by the fleet - even if it should be a fight to the death - will sow the seed of a new German fleet in the future.’ Unwilling to die to reclaim the honour of their superior officers, the sailors chanted, ‘We do not want to put to sea, for us the war is over.’ Five times the order went out for the High Seas Fleet to put to sea; five times it was ignored. Stokers on board ships that were already at sea even put the fires out in their boilers. A thousand mutineers were arrested, and, on 27 October, Admiral Franz von Hipper remarked simply, ‘Our men have rebelled.’ By 3 November, the mutinies had spread beyond the fleet, with 3000 mutinous sailors linking up with disgruntled workers to raise the red flag of revolution in Kiel. Although the governor of Kiel, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, had eight of the mutineers killed, the unrest only spread. On 4 November, thousands more sailors, factory workers and up to 20,000 garrison troops joined the uprising. Within days, the mutiny had spread to Lubeck, Hamburg, Bremen and Wilhelmshaven, heralding a wave of unrest that convinced even the most diehard militarists that Germany had lost World War I.

Incensed that Pershing had once again botched the offensive, Clemenceau fired off an angry letter to Foch demanding change. The letter railed:

‘You have watched at close range the development of General Pershing’s extractions. Unfortunately, thanks to his invincible obstinacy he has won against you as well as your immediate subordinates. The French Army and the British Army, without a moment’s respite, have been daily fighting for the past three months . but our worthy American allies, who thirst to get into action and who are unanimously acknowledged to be great soldiers, have been marking time ever since their forward jump on the first day, and in spite ofheavy losses, they have failed to conquer the ground assigned to them as their objective. No one can maintain that these troops are unusable; they are merely unused.’

Clemenceau urged Foch to inform President Wilson of Pershing’s failings and to make a ‘final decision’ regarding the American general. Wisely, though, Foch chose to ignore Clemenceau’s letter, as the Allied advance along the entire front gathered steam.

As the GAF pursued the retreating Germans in the north, and the French and American forces in the Meuse-Argonne fought an attritional bloodbath, Rawlinson made ready to breach the German defences in the centre of the Allied line along the Selle River. Although the river itself was not an imposing obstacle, Rawlinson thought that the German defensive positions behind it were solid enough to necessitate a pause in the battle to allow the British Fourth Army to bring forward its artillery and logistic support. Rawlinson’s caution ensured that, on the day of the attack, Fourth Army could call on covering fire from 33 field artillery brigades, plus 20 brigades and 13 independent batteries of heavier guns. Besides ample firepower support, Rawlinson had reason for optimism, for British intelligence reported that the German defenders only consisted of four exhausted and two comparatively fresh divisions. Unbeknownst to Rawlinson, though, Ludendorff had rushed reinforcements to the scene and Fourth Army in fact faced five fresh and four fairly fresh German divisions, meaning that the troop strength in the fight for the Selle River would be roughly equal.

‘It is on the unconquerable resistance of the Verdun front that depends the fate of a great part of the western front, perhaps even of our nation.’

General Georg von der Marwitz

At dawn on 17 October, Fourth Army went forward into the attack, against much stronger than expected German resistance. Leading the attack, the South African Brigade and the American II Corps, now a truly veteran unit that had seen continuous action as part of the Fourth Army, initially made only fitful gains against uncut barbed wire and ferocious German counterattacks. South of the headwaters of the Selle, though, IX Corps, supported by twice as many tanks, forced the German defences to an initial depth of 4114m (4500 yards) and flanked the German lines farther to the north. By the evening, the British Fourth Army, aided by the French First Army, had broken the German defences of the Hermann Position and had captured more than 5000 prisoners. In two more days of intense fighting the Allied forces pushed to a depth of 8229m (9000 yards) on a frontage of 11km (seven miles) and reached the Sambre River and the Oise Canal.

From left to right, David Lloyd George of Britain, Vittorio Orlando of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France and Woodrow Wilson of the United States, gather to discuss peace terms at the Paris Peace Conference.

As the Germans fell back ever further, the Allied leaders for the first time really dared to think that the end of the war was near. For his part Foch advocated stern armistice terms, which amounted to unconditional surrender on the part of the Germans. Clemenceau quickly intervened, though, and put Foch in his place, reminding the commander-in-chief that, ‘Your business is war, and everything that pertains to the peace ... belongs to us [the government] and only us.’ On 19 October, Lloyd George asked Haig for the first and only time regarding his opinion on armistice terms. Haig, who had rightly been accused of being overly optimistic in the past, sounded a note of caution at the 11th hour due to the unexpectedly ferocious German defence of the Selle River and replied:

As the clock ran down on the war, at 11am on 11 November 1918, several Allied units vied for the honour of firing the last shot of the conflict. The gun pictured is ‘Calamity Jane’ of the 11th Field Artillery, which fired the last US artillery round of the war.

‘The German Army is capable ofretiring to its own frontier, and holding that line if there should be any attempt to touch the honour of the German people and make them fight with the courage of despair. . The French and American Armies are not capable of making a serious offensive now. The British alone might bring the enemy to his knees. But why expend more British lives – and for what? ...I therefore advise that we only ask in the armistice for what we intend to hold, and that we set our faces against the French entering Germany to pay off old scores.’

The 240mm trench mortar, with its plunging fire, proved a devastating weapon, especially during the trench warfare phase of the Western Front. First introduced by the French in 1915, this example is operated by the US Army in 1918. Much of the US equipment came from the French.

While the Allies struggled with their first thoughts concerning how to end the war, events rushed towards a climax in Germany. Talks concerning an armistice had been ongoing in fits and starts since Hindenburg and Ludendorff had demanded an armistice at the end of September following the Allied breaking of the Hindenburg Line.. However, Germany’s last remaining hope, that the United States would advocate a lenient peace treaty, was dashed by the receipt of a note on 23 October from President Wilson demanding that Germany convert itself into a parliamentary democracy before an armistice could be granted. Wilson made it quite clear that if the United States had to deal with the ‘military masters and monarchical autocrats of Germany’, then, ‘it must demand not peace but surrender’.

Aghast at the American demand, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, without consultation, published an army order reading:

‘Wilson’s answer is a demand for unconditional surrender. It is thus unacceptable to us soldiers. It proves that our enemies’ desire for our destruction, which let loose the war in 1914, still exists undiminished ... Wilson’s answer can thus be nothing to us … but a challenge to continue our resistance…. when all our enemies know that no sacrifice will achieve the rupture of the German front, they will be ready for a peace which will make the future of our country safe for the great masses of our people.’

The Allied generals who fought World War I had only little say in the peace process. For his part, Haig willingly stepped away from matters that he believed were better left to politicians. Foch, on the other hand, became more and more agitated at concessions given by Clemenceau in the negotiations at Versailles, concessions that had been bought with French blood. Believing that Germany remained a threat, and suspicious of the League of Nations, Foch resorted to outright insubordination to make his point, stating in the press:

‘Having reached the Rhine, we must stay there. Impress that upon your fellow countrymen. ... We must have a barrier. ... Democracies like ours, which are never aggressive, must have strong natural frontiers. Remember that these seventy millions of Germans will always be a menace to us. ... They are a people both envious and warlike What was it that saved the Allies at the beginning of the war? Russia. Well, on whose side will Russia be in the future? ... And next time, remember, the Germans will make no mistake. They will break through into Northern France and will seize the Channel ports as a base of operations against England’

Foch, though he avoided being fired, was unable to alter the peace process, causing him finally to remark, ‘All of Europe is in a complete mess. Such is the work of Clemenceau.’

Prince Max, and the Kaiser himself, saw Ludendorff’s unilateral announcement as an act of gross insubordination. The next day the Kaiser reprimanded Ludendorff, both for the release of the army order and for his recent wild fluctuations of judgement concerning the military situation. Chastened, Ludendorff resigned. Hindenburg also offered his resignation, but the Kaiser urged him to stay. In Ludendorff’s place the Kaiser appointed General Wilhelm Groener, who had the unenviable task of rushing to headquarters from the Eastern Front to oversee the conclusion of a failed war.

As Groener struggled to come to grips with his new task, events on the Western Front rushed towards a conclusion. While the French worked to outflank the Hunding Position, and British forces pursued the Germans to new defensive positions in the north, on 31 October, Foch made ready to launch a climactic offensive involving attacks by all major Allied forces. In the centre of the Allied lines, two corps from the French First Army broke through German defences and occupied Guise. Further north the British First Army, spearheaded by the Canadian Corps, launched an assault on 1 November on the hastily constructed German defensive lines around Valenciennes. Facing only light resistance, and capturing several thousand demoralized German prisoners, the Canadians broke through the defences with ease, forcing a German withdrawal from the defensive line formed by the Schelde River.

The most important and cathartic victory, though, fell to the maligned American Expeditionary Force and its embattled commander. The AEF had entered the war as an untested military; however, it had survived its baptism of fire during the bitter struggle in the Meuse-Argonne. The AEF had finally become a veteran fighting force, numbering 1,867,623 men, with more arriving every day. At 3.30am on 1 November, a massive two-hour artillery barrage heralded the AEF’s final assault, in which Pershing’s men finally broke the stubborn Kriemhilde Line, and joyously began to pursue the defeated enemy. The Germans, though, fought with tenacity and skill in their withdrawal, which F. Scott Fitzgerald later described by saying that the Germans, ‘walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloodyrags’.

Between 1 and 7 November, American and French forces advanced 39km (24 miles) on both sides ofthe Meuse River, with the French finally capturing Mézières. The Battle of Meuse-Argonne was, at the time, the largest battle ever fought by the United States Army, involving 1,250,000 men in 22 divisions. In 47 days of continuous battle, US forces had suffered 26,277 dead and 95,786 wounded. However, the Americans had given as good as they got, in the final week of fighting alone inflicting 100,000 casualties on the Germans, while capturing 26,000 prisoners, 874 artillery pieces and 3000 machine guns. Pershing’s faith in his men, and his long struggle to found an independent American military force had been vindicated. Although the AEF had to suffer through a steep learning curve, and did not play the most important role in the final offensives on the Western Front, its presence in battle, its burgeoning size and tenacity were all critical factors in both giving strength to the battered Allies and in demonstrating to the beleaguered Germans that their war was lost. As a result, Pershing was correct in his judgement that the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was ‘one of the great achievements in the history of American arms’.

Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who, as Supreme Allied Commander, was the architect of the victorious Allied campaign of 1918. He signed the Armistice with Germany at 5am on the morning of 11 November in his railway carriage near Compiègne.

British troops enter Cologne, Germany, as part of the peace agreement ending World War I. The occupation force was known as the British Army of the Rhine and was under the command of General Sir Herbert Plumer, formerly commander of Second Army.

The final great Allied offensive on the Western Front in World War I fell to the British Third and Fourth armies along the Sambre River. It was somehow fitting that Rawlinson’s force, which had done so much to begin the Allied string of victories at Amiens, should have the honour of finally breaking the back of the German Army. With its soldiers and officers now quite adept at fighting the newly mobile form of battle that pervaded the final days of World War I, the men of the BEF went over the top at 5.30am on 4 November, under the cover of an especially strong artillery barrage. Facing German defenders who obviously knew that the war was already decided, the British Third and Fourth armies advanced over 16km (10 miles) in two days, taking 10,000 prisoners while suffering only light casualties. The Germans in the area were now in full flight, and the end of the war was at hand.

‘I was woken up with a wire that hostilities would cease at 11am. There were no great demonstrations by the troops, I think because it was hard to realize the war was really over.’

Captain Westmacott, 24th Division, BEF

When General Groener had arrived at Spa on 30 October to take over the German high command, he had immediately taken stock of both the military situation on the Western Front and the political situation on the German home front. By the time of his arrival a serious mutiny had broken out among the sailors of the German High Seas Fleet, who, after years of inaction, refused to take part in a final ‘death ride’ against the British Grand Fleet. The mutiny quickly spread to 11 northern cities, including Bremen and Hamburg, and troops sent to suppress the mutineers instead joined them. As unrest spread across the nation, Groener toured the front and discovered that the military situation was untenable. Groener informed the German Chancellor, Prince Max, that, to avoid total military catastrophe, an armistice was required by Saturday 9 November, and that even 11 November might be too late.

Prince Max, though, realized that Wilson and the Allies would never deal with the Kaiser, and sent a representative to Spa, where the Kaiser had taken refuge with the German high command, to suggest his abdication. In fury the Kaiser responded:

‘All the dynasties will fall along with me, the army is left leaderless, the front line troops disband and steam across the Rhine. The disaffected gang together, hang, murder, and plunder - assisted by the enemy. That is why I have no intention of abdicating . I have no intention of quitting the throne because of a few hundred Jews and a thousand workmen. Tell that to your masters in Berlin!’

The Kaiser, though, had greatly overestimated his worth and standing in his own empire, for he had long ago become secondary to the needs of the military at war. The military and the nation now required an armistice to survive, and chose no longer to stand behind the oaths that bound them to an ancient regime. After polling his officers regarding the situation, Groener informed the Kaiser, ‘The Army will march home in peace and order under its leaders and commanding generals, but not under the command of Your Majesty for it no longer stands behind Your Majesty.’ Crestfallen, on 10 November the Kaiser boarded his cream and gold train, which carried him into exile in the Netherlands, ending 504 years of Hohenzollern rule in Prussia and Germany.

Meanwhile, on 8 November a German armistice delegation, headed by Matthias Erzberger, had met with Foch where it received terms, tantamount to unconditional surrender, which allowed the German Army to go home with its rifles, and its officers with their swords, but demanded the handing over of all of its artillery and most of its machine guns. The proposed agreement also required the Germans to pull back to their frontier and to allow the Allies bridgeheads over the Rhine, while leaving the British naval blockade in place. Shocked by the harsh terms, the delegation returned to report the terms to the German Government. The abdication of the Kaiser, and the proclamation of the new German Republic, left the matter of armistice terms in the hands of the Social Democratic government of Friedrich Ebert, which, under severe pressure to end the war and to halt the collapse of the German body politic, saw no option but to accept what it saw as the draconian terms.

For millions of parents, children and siblings, the end of World War I meant not joy, but only profound grief over the loss of a loved one. After her youngest son was killed in battle, German artist Kaethe Kollwitz not only wrote of her grief to her surviving son but also carved the sculptures that would later be placed in the Flanders cemetery where her son was buried:

‘Why does work help me in these times? It is not enough to say that it relaxes me very much. It is simply that it is a task that I may not shirk. As you, the children of my body, have been my tasks, so too are my other works. Perhaps that sounds as though I meant that I would be depriving humanity of something if I stopped working. In a certain sense-yes. Because this is my post and I may not leave it until I have made my talent bear interest. Everyone who is vouchsafed life has the obligation of carrying out to the last item the plan laid down in him. Then he may go. ... If it had been possible for father or me to die for him so that he might live, how gladly we would have gone. For you as well as for him. But that was not to be. I am not seed for the planting. I have only the task of nurturing the seed placed in me. And you, my Hans? May you have been born for life after all! You must have been, and you must believe in it’

The final armistice line of the Great War on the Western Front. The fact that Allied forces had not yet entered Germany added credence to the myth that Germany was not defeated on the battlefield, but was instead stabbed in the back by homegrown enemies.

The German armistice team returned to meet with Foch aboard his railway carriage in the Forest of Compiegne, and, at 5.05am on 11 November, signed the armistice, which went into effect at 11.00am. At the designated time, the guns of the Western Front fell silent, and World War I had come to an end. Nearly 10 million men died in World War I - 3.6 million from the Central Powers and 5.7 million from the Allied and Associated Powers. During the war Russia lost 2.3 million men, France 1.9 million, Britain 900,000, Italy 450,000 and the United States 126,000. Regardless of the cost, many on the Allied side believed that the war had ended too soon, that an incomplete defeat of Germany would inevitably lead to trouble in the future. Perceptively, Pershing remarked:

Born in 1889, the son of a minor Austrian customs official, Hitler moved to Vienna in 1908 to pursue a career as an artist. Rejected for admission to the prestigious Viennese Academy of Fine Arts, Hitler eked out a meagre living through the sales of his artwork and soon became involved in radical fringe political movements, which mixed anti-Semitism and strident German nationalism. Seeking both to rekindle his artistic career and to immerse himself more fully in German right-wing politics, in 1913 Hitler moved to Munich, where he was caught up in the events leading to World War I. After rushing to join the army upon the outbreak of war, in November 1914, Hitler took part in the First Battle of Ypres, where he won the Iron Cross Second Class for bravery. Reflecting on the difficulties of trench warfare, in January 1915 Hitler wrote to an acquaintance:

‘I think so often of Munich and each of us has but one wish ... that those among us who have the luck to see our homeland again will find it purer and cleansed from foreign influence, so that by the sacrifice and agony which so many hundreds of thousands of us endure every day, that by the river of blood which flows here daily, against an international world of enemies, not only will Germany’s enemies from the outside be smashed, but also our domestic internationalism will be broken up.’

After recovering from wounds received in battle on 7 October 1916, Corporal Hitler returned to the front for the remainder of the war, during which time he often served in the dangerous position of a runner. Hitler took part in the German Spring Offensives of 1918, receiving an Iron Cross First Class for an incident in which he captured four French prisoners with only his pistol for protection. As the war turned against Germany, Hitler fought on with determination and was shocked to learn of strikes and riots on the German home front. He wrote that he wondered what the army was fighting for ‘if the homeland itself no longer wanted victory? For whom the immense sacrifices and privations? The soldier is expected to fight for victory and the homeland goes on strike against it!’

Adolf Hitler (back row, centre), like many German World War I veterans, could not come to terms with Germany’s defeat.

As the war neared its end, on 14 October 1918 Hitler was blinded in a gas attack near Ypres and evacuated to a military hospital in Pasewalk, Germany. When he learned of the armistice ending the Great War, Hitler turned his face to the hospital wall and wept bitterly. Galvanized by his experiences in World War I, Hitler would devote himself to undoing the Treaty of Versailles and punishing those whom he believed to be responsible for Germany’s defeat.

American troops, who had done so much to tip the balance of the war in favour of the Allies and help weather the storm of the Spring Offensives, celebrate the end of the conflict. The United States lost 126,000 dead in World War I, and over 200,000 wounded.

‘We shouldn’t have done it [the armistice]. If they had given us another ten days we would have rounded up the entire German army, captured it, humiliated it. . The German troops today are marching back to Germany announcing that they have never been defeated. . What I dread is that Germany doesn’t know that she was licked. Had they given us another week we’d have taught them.’

As it happened, Pershing was correct. Ludendorff and others utilized the stab-in-the-back legend quite effectively in the inter-war years, a legend that played well in a nation that had paid so much and had received so little in return. The myth that the German army had not been defeated, coupled with the imperfect Treaty of Versailles, consigned Europe to the grim fate of fighting World War II.