German troops pass through a French village as part of Germany’s strategic retreat on the Western Front in 1917. The withdrawal, meant to shorten German lines to allow for the accumulation of much-needed reserves, threw complicated Allied plans for attack in 1917 into disarray.

After three years of brutal warfare on the Western Front, and after the twin bloodlettings of Verdun and the Somme, the combatant nations paused to take stock of the strategic situation at the beginning of 1917. Fearing a repetition of the horrible attritional battles, each of the belligerent powers would gamble everything on victory in 1917 but would fall short.

The carnage of Verdun and the Somme had a pervasive effect on World War I as a whole and on the Western Front in particular. The twin battles shattered lives, ended some military careers and advanced others, toppled governments and altered strategic planning. At the most personal level, Verdun and the Somme had fundamentally altered the lives of their soldier participants. Far from the quick and glorious victories that many had expected in 1914, the titanic battles for many had instead epitomized slow, senseless slaughter and the sacrifice of a generation. German lieutenant Ernst Jünger spoke for many:

Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (centre), who had risen to fame first at the Battle of Tannenberg, and then as the overall commander of the Eastern Front, in 1916 took control of Germany’s overall military policy, working in tandem with General Erich Ludendorff.

‘For I cannot too often repeat, a battle was no longer an episode that spent itself in blood and fire; it was a condition of things that dug itself in remorselessly week after week and even month after month. What was a man’s life in this wilderness whose vapour was laden with the stench of thousands upon thousands of decaying bodies? Death lay in ambush for each one in every shell-hole, merciless, and making one merciless in return. ... There it was [at the Somme] that the dust first drank the blood of our trained and disciplined youth. Those fine qualities which had raised the German race to greatness leapt once more in dazzling flame and then slowly went out in a sea of mud and blood.’

At the strategic level, Junger’s commander, General Erich Ludendorff, who along with Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had effectively taken control of the German war effort, had to come to terms with the legacy of 1916. Admitting in his memoirs that the battles of Verdun and the Somme had left Germany ‘completely exhausted on the Western Front’, Ludendorff summarized the strategic implications of the resulting situation:

‘The Supreme Army Command had to bear in mind that the enemy’s great superiority in men and material would be even more painfully felt in 1917 than in 1916. It was plainly to be feared that early in the year “Somme fighting” would burst out at various points on our fronts, and that even our troops would not be able to withstand such attacks indefinitely, especially if the enemy gave us no time for rest and for the accumulation of material. Our position was unusually difficult, and no way of escape was visible. ... The future looked dark.’

Although Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, in command of the British Expeditionary Force, and General Joseph Joffre, who led the French forces on the Western Front, were fully conscious of the fearsome butcher’s bill that their nations had paid during the fighting of 1916, they interpreted Verdun and the Somme as costly victories. Working within that military analytical framework, on 16 November 1916, Haig and Joffre met at the Chantilly Conference to begin work on the strategic plan for the coming year and were primarily concerned with maintaining an unrelenting pressure on the Germans in both France and Flanders. Joffre explained his plan for 1917 rather bluntly: ‘I have decided to seek the rupture of the enemy’s forces by a general offensive executed between the Somme and the Oise at the same time as the British Armies carry out a similar operation between Bapaume and Vimy.’

It also became clear at Chantilly that, due to the price of Verdun, Britain would have to shoulder an ever-increasing military load on the Western Front. The changed Allied strategic balance, coupled with instructions from Prime Minister Herbert Asquith regarding the pivotal value of the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast, prompted Haig to press Joffre to agree that a British offensive in Flanders form the first part of Allied planning for the coming year, to which Joffre reluctantly agreed. Joffre and Haig’s desire doggedly to pursue strategic victory on the Western Front, as well as their interpretations of Verdun and the Somme as victories, however, resulted in immediate conflict with their own governments, who defined both the experience of 1916 and the most effective military route to victory quite differently.

British wartime Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, whose indecisive wartime leadership led to the fracture of the Liberal Party and the rise of a coalition government under the fiery and fractious David Lloyd George. Asquith’s eldest son, Raymond, was killed at the Battle of the Somme.

World War I was the first major conflict after the industrial revolution, which provided Western nations with the economic and technological strength first to arm millions of men and then to keep them in the field for years on end.

By 1914, due to advancements in both agriculture and industry, seven countries were able to field armies numbering in excess of one million men, which meant that World War I would not pit professional army against professional army; rather it would pit nations, their militaries, their populations and their economies, against nations in total war. Dwarfing all that came before, the twin battles of the Somme and Verdun best personified the new and terrible era of total war. Together the two battles lasted 16 months and cost two million casualties. During the two battles, both sides fired off 35 million artillery shells and in excess of 60 million machine-gun bullets, a feat of industrial production never before witnessed. In addition to this, the men involved in the Somme and Verdun also consumed vast amounts of additional industrial and agricultural goods, ranging from food to gas respirators, which in the end meant that the two great battles of 1916 cost more than the gross national products of the vast majority of countries in the world. For nations to survive in the world of modern, total war, their populations had to accept great sacrifice, a fact that would also serve to transform World War I into a massive engine of both social and cultural change.

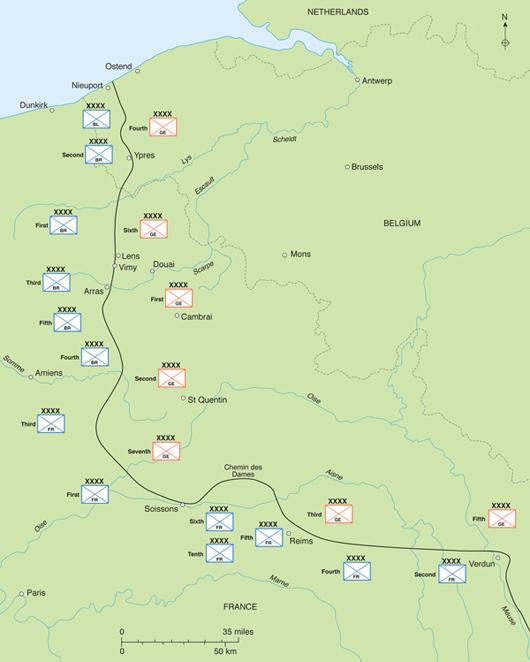

The Western Front at the beginning of 1917. Following grievous losses at Verdun and the Somme, the Germans felt unable to defend their holdings in France, which followed a circuitous route from the English Channel to the Swiss border, and chose instead to opt for a strategic withdrawal.

Even as Haig was presenting his revised plan to Joffre, a seismic shift took place in British politics. Unhappy both with the tactical direction of the war and the indecisive leadership of Asquith, a coalition of Liberals, Conservatives and Labour took control of the House of Commons and elevated David Lloyd George to the position of Prime Minister. Haig had little in common with his new political master. Indeed the two were often at odds, with Haig regarding the Prime Minister as ‘shifty and unreliable’, while Lloyd George judged Haig to be but an ‘arid strategist’. In matters of strategy, Lloyd George had long favoured shifting Britain’s military might away from the Western Front to other, possibly more profitable, theatres of war. As such, the new Prime Minister’s continuing devotion to the ‘easterner’ school of thought ran contrary to Haig’s unwavering belief that the Allies had to destroy the might of the German Army in France and Flanders. Differing strategic visions set the two men on a collision course, for Lloyd George believed that the planning of Haig and Joffre would only result in another Somme; he later recalled in his memoirs:

General Robert Nivelle, who had risen to fame at the Battle of Verdun, by 1917 had taken command of French forces on the Western Front. His overconfidence and continued devotion to the power of the offensive resulted in disaster and mutiny in the ranks of the French military for much of 1917.

A lieutenant, serving with the elite French Escadrille No. 3, Groupe de Chasse 12. This squadron, known as the ‘storks’, was home to Georges Guynemer, one of the top French air aces of World War I who achieved 53 victories before his death in September 1917.

‘The possibility never entered into the computation of these master minds that the survivors [of another Somme] might sooner or later object to this method of ‘forming fours’ by taking their turn in the slaughter house from which such multitude of their comrades never emerged. ... Was there any other chance left except once more to sprinkle the western portal of the temple of Moloch with blood from what remained of the most valiant hearts amongst the youth of France and Britain’? I decided to explore every possibility before surrendering to a renewal of the horrors of the West.’

The spectre of 1916 also haunted the halls of power in France. In December, the once unassailable General Joffre, who had always had a stormy relationship with the French parliament, fell from grace. Blaming him for failing adequately to prepare for the German attack on Verdun, Prime Minister René Viviani quietly removed Joffre from command by kicking him upstairs and promoting him to marshal of France. As a replacement, the French Government chose General Robert Nivelle, one of the heroes of Verdun.

Confident, articulate and effusive, Nivelle remained a devotee of the offensive, and believed that he had struck on a plan for certain victory in 1917. Rejecting the agreement that had been reached in Chantilly, Nivelle reopened the strategic debate by advocating a new plan designed finally to crush the German defensive lines. The scheme called for a diversionary British attack near Arras to distract German attention while the French gathered their strength for the climactic battle in the area of the Chemin des Dames Ridge.

In mounting the main attack Nivelle proposed to use the same tactics that had won him such stirring victories at Verdun, but on a greater scale. Thorough artillery preparation, followed by a precise creeping barrage, would, he claimed, preface an attack of ‘violence, brutality and rapidity’ that would rupture the German front lines in at most 48 hours, leading to a pursuit of a defeated enemy into Germany. Most important to politicians wary of a repeat of Verdun or the Somme, though, was Nivelle’s pledge to end his attack within two days if it had not achieved success. Desperate for a ray of hope in such dark times, the French Government approved Nivelle’s scheme, over the objection of several important French military figures including General Henri Philippe Pétain and General Ferdinand Foch, who predicted that the offensive would end in disaster.

Only the British remained to be convinced. Realizing that Haig still supported a British offensive in Flanders, in January 1917, Nivelle took his case directly to Lloyd George, who was in Paris on the way home from an Allied strategic conference in Rome at which he had vainly pressed the case for shifting the emphasis of the war away from the Western Front. Aboard Lloyd George’s train car while stopped at the Gare du Nord, Nivelle unfolded his plan. Unlike the notoriously tongue-tied Haig, Nivelle was a glib conversationalist and quite comfortable in the company of politicians. Apart from his social ease and fluent English, Nivelle offered Lloyd George a near-perfect military scenario. There would be no repeat of the slaughter and seemingly senseless sacrifice of the Somme. Making the offer even more irresistible, Nivelle’s plan promised a victorious campaign in which the French would run the greatest risk and pay the highest cost. Eager to shift the strategic reality of a war he judged to be going wrong, Lloyd George quickly fell under the spell of Nivelle’s charm. In writing to his mistress Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George made clear his preference for the plan of the dashing Nivelle over that of Haig stating: ‘Nivelle has proved himself to be a Man at Verdun; and when you get a Man against one who has not proved himself, why, you back the Man!’

Female nurses from each belligerent nation served heroically in and near the front lines. An American nurse, known as ‘Mademoiselle Miss’, collected and published her letters home in an effort to educate the public concerning the role of nurses in war. In one letter, she attempted to outline her daily routine:

‘Ever since I began my work I have been watching for a chance to sketch for you at least one day in detail, that you may have some vague idea of this unique and inexpressible life.

‘At quarter to six A.M., I am up and sponged and well flesh-brushed. My good old lady gives me a huge bowl of coffee and four lumps of sugar, bread and butter, and a boiled egg, for 12 cents, an extravagance which I indulge in to avoid the probable consequence of the long walk to the Hospital on an empty stomach through the mists of the Marne, which are thick and weird enough in the early morning. It is a devious way through mud and mist, and almost anything is likely to cross your path, a bent, white-capped old woman like a stray from some old Dutch painting; a black cat, lean and rusty (everything is hungry about here); an aeroplane wheeling about on the watch for Taubes [German aircraft] which are frequent and fiery these days; a convoy of automobiles driving at top speed to the trenches; the dim wraith of a funeral procession disappearing in the distance.

‘When I get to my pavilion, there is sure to be “Grandpa”, my treasured old orderly, busy at brushing out the entrance. He immediately drops his broom, and holds out his good brawny hand to hope that his “Mademoiselle Miss” (the name I am generally known by) has slept well, and will not work too hard during the coming day. Grandpa is my Eternal Vigilance, always on hand, always ready to do every bidding, and zealous to spare me every possible fatigue. Last week he and my other orderlies were ill, he and Karbiche, the merry faithful clown, with bronchitis, and Loupias with tonsilitis and a bad bone-felon and I had to carry my patients to the surgical dressings room myself. He nearly wept with chagrin.

‘The first thing I do, after a word of greeting to each of the 34 children, is to review the ward and see that it is well washed, in order, and no spoons or bottles out of place, and to start instruments boiling. After that begin the temperatures. Along with the temperatures go face-washing and mouth-rinsing, generally engineered by faithful Grandpa. About half-past eight, the doctor makes his appearance. When he has made the tour of the ward, I am left complete mistress of the scene for the rest of the day, with 34 lives in my hand more than half of which hang in the balance. If there is anything critical, I send for the big surgeon, and he always comes graciously, which is a great mark of confidence.

‘About 9 A.M. I begin the dressings, unless there are anti-tetanus injections to give for those who may have arrived in the night, or someone is dying, or there is an urgent operation. But we shall suppose an uninterrupted day. I begin with the important dressings, which are often long and dangerous, and I can do but three or four before the bell rings for soup at 10.45 A.M.

‘I think you would sicken with fright if you could see the operations that a poor nurse is called upon to perform, the putting in of drains, the washing of wounds so huge and ghastly as to make one marvel at the endurance that is man’s, the digging about for bits of shrapnel. I assure you that the word responsibility takes a special meaning here. After the soup for the wounded, comes that of the nurses, when all crowd into a tiny plank hut, and stuff meat and potatoes as fast as we can between disjointed bits of gossip. Immediately after lunch I spend an hour or so setting to rights the surgical dressings routine, doing little services, and distributing cakes or bonbons. It is amazing how a bit of peppermint will console a soldier when a smile goes with it!

‘Dressings all the afternoon until it is time for temperatures; then soup for the soldiers; and mine, which is soon finished; then the massage for those that need it, etc., after which I prepare my soothing drinks and give the injections. It is the sweetest time of the day, for then one puts off the nurse and becomes the mother; and we have such fun over the warm drinks. They are nice and sweet and hot, and the soldiers adore their “American drinks”.

‘When this is done, I go around and stuff cotton under weary backs and plastered limbs, bid all the children good-night, polish my instruments, clean out the surgical dressings room, and hurry home through the frosty night.

‘This is the rough outline of an ordinary day, and into that let your fancy weave all that is too holy or terrible, too touching or humorous to put into words: the last kiss a soldier gives you for his family he will never see; the watches with the priest when all is still and dark, but for the light of my little electric lamp and a bit of moonlight through the window; the agonies and heroisms; the wit and affection that play like varied lights and darks along the days.’

French soldiers in action on the Chemin des Dames, the dominating ridge line the capture of which formed the centrepiece of Nivelle’s offensive plan in 1917 – a controversial scheme that resulted in a nearly unbearable strain within the Allied command structure.

The acquiescence of Lloyd George ensured that Nivelle would have his chance at victory. However, even as planning for the offensive progressed, political manoeuvring continued that not only greatly damaged Allied unity but also shook the foundations of the British military command. Although he believed that he had succeeded in avoiding another Somme battle in 1917, Lloyd George did not trust his generals in the least. As Haig made preparations for an assault near Arras, as called for in Nivelle’s plan, Lloyd George decided to utilize the occasion of Nivelle’s offensive to assert his complete authority over the British military in matters of strategy and tactics.

At a February conference at Calais regarding logistic and transportation difficulties, Lloyd George unveiled secret plans to restructure the Allied system of command on the Western Front. Maurice Hankey, the War Cabinet Secretary, later recalled that the plan: ‘fairly took my breath away, as it practically demanded the placing of the British army under Nivelle; the appointment of a British “chief of staff” to Nivelle, who had powers practically eliminating Haig as his Chief of the General Staff, the scheme reducing Haig to a cypher’. Shocked, Haig recorded that he ‘would rather be tried by court-martial than betray the Army by agreeing to its being placed under the French’.

Born in 1886, Siegfried Sassoon enjoyed a privileged upbringing and had begun to build a budding career as a poet until World War I interrupted his life. Full of the patriotic fervour that so epitomized his generation, Sassoon volunteered for war, eventually joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers and seeing service in France. An exemplary officer, Sassoon won the Military Cross for bringing wounded back to the lines under enemy fire, and even earned the sobriquet ‘Mad Jack’ from his men, due to his fearless nature in battle. However, Sassoon’s experience in battle left both him and his poetry changed forever. While convalescing in Britain after being wounded, Sassoon decided that he could not return to such a wasteful war, and published ‘A Soldier’s Defiance’ in a newspaper stating: ‘I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be party to prolonging these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust’. Rather than prosecute Sassoon, whose poetry was already becoming well known, the military authorities had him declared unfit for service and sent to Craiglockhart Mental Hospital, where he received treatment for shell shock and befriended one of Britain’s other most influential war poets, Wilfred Owen. Sassoon eventually returned to battle, only to be wounded again, after which time he spent the remainder of the war in Britain. In the inter-war years, Sassoon became one of Britain’s best-known writers, and his anti-war poetry and prose became emblematic of Britain’s desire never to fight such a war again.

Nieuport 27, fighter scout biplane. Essentially an updated version of the popular Nieuport 17, which had achieved great success in 1916, the Nieuport 27, powered by a 130hp Le Rhone engine, saw considerable service in the skies over the Western Front in 1917.

‘Farewell, comrades of the Somme! The earth which drank your blood is upheaved and torn asunder ... it is turned into a desert, and your graves are made free from the dwellings of men. Those who tread it, your desert, will be greeted by our shells.’

German journalist Georg Querl on the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line

Tempers flared, threatening to lead to a breakdown of the conference and the resignation of much of the command structure of the BEF before cooler heads prevailed. The compromise agreement eventually reached at the Calais Conference placed Haig under Nivelle’s overall command for only the duration of the coming offensive. The underlying causes of the crisis in command, though, remained. Lloyd George had been frustrated in his attempt to seize strategic control of the conflict, while Haig became ever more wary of the meddling of civilian amateurs in tactical matters best left to the military. The Calais Conference had strained British civil-military relations to the breaking point and, as the war neared a point of great crisis, relations between the government and the military in Britain remained characterized by mistrust and animosity.

Even as the British command machine sputtered and coughed, the Germans intervened and greatly complicated the strategic picture on the Western Front, threatening to scuttle all Allied planning. Under great pressure from the British blockade, Germany was hard pressed both to feed its population and to provide adequately for its massive military efforts. A single army corps on a monthly basis consumed 453,592kg (one million pounds) of meat, 660,000 loaves of bread, 85,729kg (189,000lb) of fat and 33,112kg (73,000lb) of coffee. The XVIII Corps, for example, estimated that it needed 1000 wagons extending for 15km (nine miles) to haul its monthly stores of bread; it also slaughtered 1320 cows, 1100 pigs and 4158 sheep per month. Since no one in power had foreseen a long war, the massive supply needs of the military reduced the home front to ever-stricter forms of rationing. By the winter of 1916, the situation had become critical, with one observer remarking that the optimism of 1914 was long gone: ‘Now one sees faces like masks, blue with cold and drawn by hunger, with the harassed expression common to all those who are continually speculating as to the possibility of another meal.’

German troops pass through the ruins of a French village during their withdrawal on the Western Front. Hoping to delay French and British pursuit, the Germans laid waste to the villages, farms and transportation network in the area of the retreat.

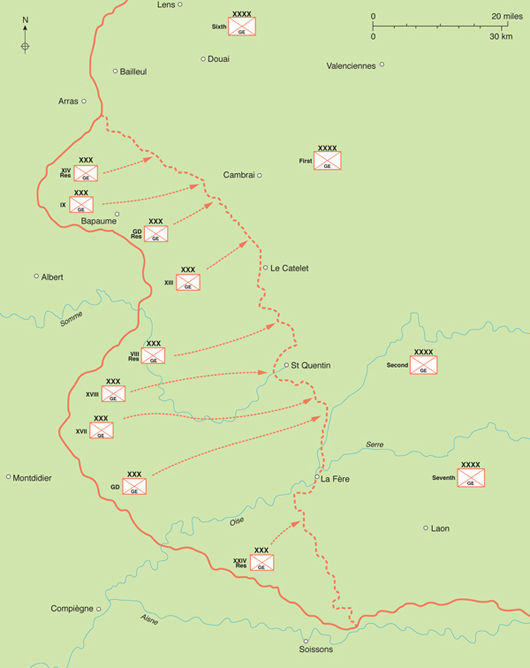

Concerned by the state of German morale, and echoing Haig’s appraisal of Verdun and the Somme as hard-fought victories, Ludendorff despaired of Germany’s ability to survive another year of attrition and want. In a desperate measure, the German command team ordered the evacuation of the German salient between Arras and Soissons and the withdrawal to a specially constructed defensive network, later dubbed by the Allies the Hindenburg Line. The withdrawal allowed for the accumulation of much-needed reserves and was also designed to buy Germany valuable time for the nation’s greatest ever military gamble.

The strategic situation had become so grave that the German Government had decided to launch unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic in an effort to starve the British into submission. Ludendorff and his command compatriots fully realized that unleashing the U-boats would result in an American entry into the conflict, but, with the German military so sorely pressed on the Western Front, the German command team judged the U-boat offensive to be worth the risk. Achieving victory through the submarine war in Ludendorff’s words was of the ‘highest importance’ and the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line was thus designed ‘to postpone the struggle in the West as long as possible to allow the submarine campaign to produce decisive results’.

In February 1917, even as the German U-boats made their first kills, the German Army on the Western Front began its withdrawal to powerful new defensive lines that had already been under construction for five months. Under Ludendorff’s orders, German troops carried out the evacuation with great ruthlessness, resulting in the destruction of most of the towns and villages in the salient. Ernst Jünger recalled the scene:

‘The villages we passed through as we marched ... had the appearance of lunatic asylums let loose. Whole companies were pushing walls down or sitting on the roofs of the houses throwing down the slats. Trees were felled, window-frames broken, and smoke and clouds of dust rose from heap after heap of rubbish. In short, an orgy of destruction was going on. The men were chasing round with incredible zeal, arrayed in the abandoned wardrobes of the population, in women’s dresses and with top hats on their heads. ... Every village up to the Siegfried Line [the German name for the Hindenburg Line] was a rubbish heap. Every tree felled, every road mined, every well fouled, every water course dammed, every cellar blown up or made into a death-trap with concealed bombs, all supplies or metal sent back, all rails ripped up, all telephone wire rolled up, everything burnable burned. In short the country over which the enemy were to advance had been turned into utter desolation.‘

A wounded French soldier is carried from the battlefield at Verdun. It was General Robert Nivelle’s promise that he would not allow his 1917 offensive to degenerate into another repetition of the Somme or Verdun that won approval for his planning.

German troops clearing dead from a shell-hole during the Battle of Verdun in 1916. The prodigious slaughter in the signature battles of 1916, Verdun and the Somme, caused each of the combatant powers on the Western Front to take strategic gambles in 1917.

The British Webley & Scott self-loading pistol, 1912. Standard weaponry for British officers, pistols were of only marginal use in the tactical situations that defined trench warfare.

The German withdrawal took place in the very area in which Nivelle had proposed to attack, which both greatly disrupted French forward movement and made logistical preparations exceedingly difficult. Making matters worse, Nivelle’s attack now faced a much more formidable German defensive network. In late March, a new French governmental team, Premier Alexandre Ribot and Minister of War Paul Painlevé, requested that Nivelle reconsider his planning in light of the changed tactical situation. Nivelle, though, stood his ground, considering the German withdrawal merely an inconvenience. Nivelle assured the sceptical politicians of impending victory and informed them that if he no longer held their confidence they should appoint a successor. With the British slated soon to begin their attack at Arras, Painlevé feared that a cancellation of the offensive would be injurious to Allied unity, and possibly precipitate a crisis that would bring down the government. Although grave doubts remained, Painlevé had been defeated and had no choice but to allow Nivelle his chance at victory.

Although Nivelle had, in the end, failed to win the lasting support of his own government for his offensive, he had been able to convince his men and his nation that victory was at hand. He promised the war-weary troops that there would be no more Verduns and no more wasting of men’s lives for minimal gain. No, his attack would be different, and French élan and firepower would win the day at last. To a nation tiring of sacrifice, Nivelle’s words were a tonic. Morale soared, and as a result the spring of 1917 resembled that of 1914. Nivelle had raised French hopes to a new height – only to bring them crashing down to a disastrous low.

With almost criminal carelessness, Nivelle had informed several politicians, many newspapers and countless battalion and company commanders of the outlines of his military plan. Across France all of the talk was about the great offensive that would win the war. Everyone seemed to know the dates of the attack and its general goals, and the Germans could scarcely avoid taking notice of the rumours and publicity surrounding Nivelle’s preparations.

Even worse, in both January and March German trench raids had succeeded in capturing detailed plans revealing the French dispositions and targets for the forthcoming attack. The German commanders, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, knew full well what the French were planning and arranged their defences and reserves accordingly, ensuring that the French offensive along the length of the Chemin des Dames Ridge would receive a very rude reception indeed.

The area affected by Operation Alberich, the code name for the German withdrawal on the Western Front. The move back to the strongly constructed fixed defences of the Hindenburg Line disrupted the planning for the Allied joint offensive of spring 1917.