5

Natural Convection Heat Transfer

5.1. Introduction

All of the situations studied in the previous chapters concern flow in forced convection, that is to say, the fluid motion is generated by an external unit: pump, compressor, etc. Yet, whilst such situations represent the majority of flows encountered in industrial systems, it is important to highlight the existence, in practice, of cases where motion is generated in the absence of any external element.

Indeed, unlike forced convection, natural (or free) convection corresponds to a heat transfer mode where the fluid motion is quite simply induced by forces of Archimedes, generated by differences in fluid density, the latter being themselves caused by temperature differences within the fluid. Examples of this type of flow can be found in the operation of flat thermosiphon solar collectors or in heat exchanges between wall-mounted heating radiators and ambient air.

5.2. Characterizing the motion of natural convection

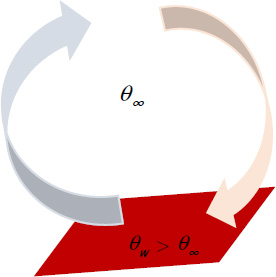

Consider a fluid at temperature θ∞, in contact with a surface of temperature θw, greater than θ∞ (see Figure 5.1). The fluid masses located in the vicinity of the surface heat up and their densities, thus, decrease.

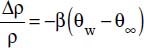

This decrease in density makes these masses lighter which enables them to rise upward, with a force proportional to the density difference thus created. Indeed, the force per unit volume exerted on these masses is equal to  . As a result, a motion is generated, where the hot fluid masses rise, leaving space for the cooler masses, which “plunge” towards the hot plate. The acceleration,

. As a result, a motion is generated, where the hot fluid masses rise, leaving space for the cooler masses, which “plunge” towards the hot plate. The acceleration,  , of this motion is obtained by dividing force by mass, or:

, of this motion is obtained by dividing force by mass, or:  .

.

Figure 5.1. Natural convection. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

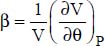

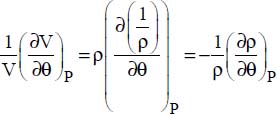

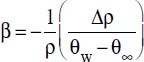

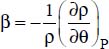

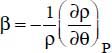

In order to derive an expression for the relative variation of density,  , let us introduce the constant-pressure thermal expansion coefficient:

, let us introduce the constant-pressure thermal expansion coefficient:

Yet:  .

.

Or, as a first approximation:  .

.

Hence:  .

.

The acceleration,  , of the upward motion due to the temperature difference then becomes:

, of the upward motion due to the temperature difference then becomes:

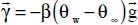

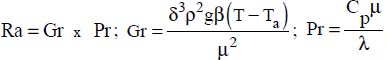

Thus, the motion will be conditioned by the parameter β(θw −θ∞)g, which constitutes the driving force for natural convection. From this parameter, we can then define a dimensionless number, called the Grashof number, which enables us to compare this driving force of natural convection (β(θw −θ∞)g) to the viscous forces determined by the kinematic viscosity  of the fluid considered.

of the fluid considered.

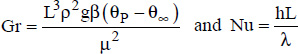

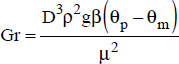

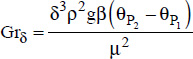

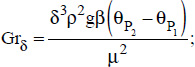

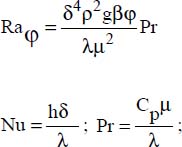

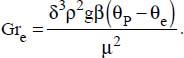

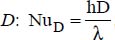

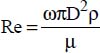

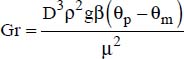

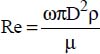

The Grashof number is thus defined by:  , where:

, where:

δ is a characteristic dimension of the surface considered: the height, length, width or diameter, as appropriate;

ρ is the density of the fluid;

G is the acceleration of gravity;

β is the constant-pressure thermal expansion coefficient of the fluid:

μ is the viscosity of the fluid within the range of temperatures considered;

(θw −θ∞) is the gradient between the wall temperature, θw, and the fluid approach temperature, θ∞.

5.3. Correlations in natural convection

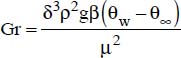

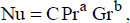

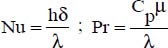

We have shown, through the application of dimensional analysis (see Chapter 1, section 1.4.2.2), that the natural convection heat transfer coefficient, h, i.e. the Nusselt number, can be expressed as a function of the Grashof and Prandtl numbers, as follows:

where:

Parameters C, a and b, are determined based on experimentation

Several experiments of this type have been conducted and have enabled appropriate parameters to be determined for the experimental situations considered. The following sections present the most significant correlations determined in this way.

The relations presented in the sub-sections below consider the different situations that can be of interest in engineering calculations:

- – vertical plane surfaces;

- – vertical cylindrical surfaces;

- – horizontal surfaces;

- – horizontal cylinders;

- – plane surfaces forming an angle, α, with the horizontal surface;

- – spheres;

- – vertical conical surfaces;

- – any vertical surface;

- – volumes limited by parallel surfaces;

- – cylinders, disks or spheres in rotation.

5.4. Vertical plates subject to natural convection

This type of problem corresponds to the scenario of wall-mounted ambient-heating radiators, where heat is transmitted from the radiator to the air in the room by natural convection. It is also encountered in the case of electronic-component heat sinks; see sections 5.17 to 5.19.

In industrial environments, several situations are encountered where vertical surfaces are cooled or heated by natural convection.

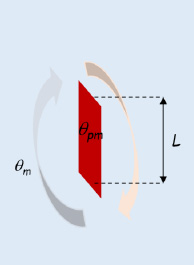

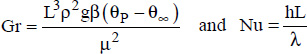

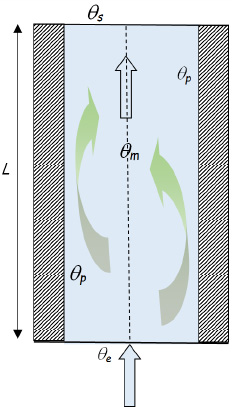

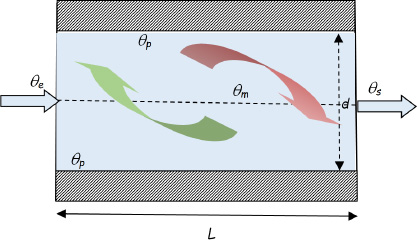

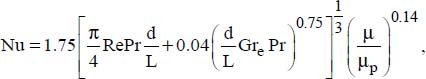

Both Gebhart (1961) and Kato, Nishiwaki and Hirata (1968) analyzed the problems relating to natural convection heat transfer between a significant mass of fluid at average temperature θm and hot vertical plane surfaces (temperature θpm > θm).

Figure 5.2. Vertical plate. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

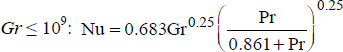

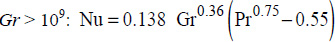

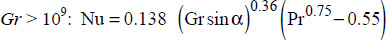

Under these conditions, the following correlations have been determined:

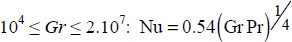

- – For

;

; - – For

.

.

In these relations:

- – The characteristic dimension taken into account in the Nusselt and Grashof numbers is the height, L, of the surface:

- –

;

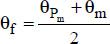

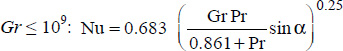

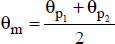

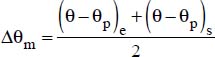

; - – The physical properties of the liquid are taken at the average temperature of the film, defined by:

- - θPm is the average temperature of the plate;

- - θm is the average temperature of the fluid.

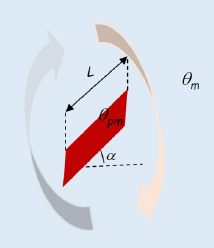

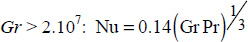

5.5. Inclined plates subject to natural convection

Figure 5.3. Inclined plate. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

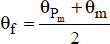

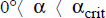

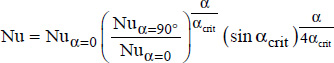

In order to estimate the natural convection heat transfer coefficient between a significant mass of fluid at average temperature θm and a flat plate forming an angle, α , with the horizontal surface, the following correlations can be used:

- – for

;

; - – for

.

.

In these relations:

- – the characteristic dimension taken into account in the Nusselt and Grashof numbers is the Length, L, of the surface:

- –

;

; - – the physical properties of the liquid are taken at the average temperature of the film, defined by:

:

:

- - θPm is the average temperature of the plate;

- - θm is the average temperature of the fluid.

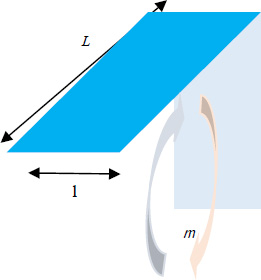

5.6. Horizontal plates subject to natural convection

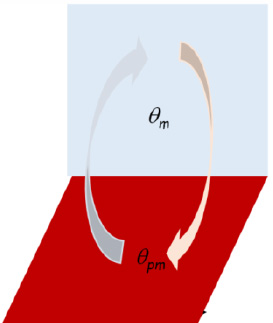

Several studies have been conducted on natural convection heat transfer between horizontal plates and the surrounding environment (Brown and Marco, 1958; Jakob, 1957). The correlations obtained are of great use in calculations relating to thermal design in buildings and particularly for the design of underfloor heating.

5.6.1. Case of underfloor heating

Figure 5.4. Underfloor heating. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

For a hot surface placed in the lower part of a chamber containing the fluid, one of the following correlations can be used:

- – for

;

; - – for

.

.

In these relations, the characteristic dimension, δ, taken into account in Nu and in Gr is:

- – the side, for a square;

- – δ = 0.9 D, for a disk (D = diameter);

- – δ = average length and width for a rectangle.

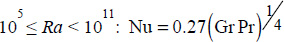

5.6.2. Ceiling cooling systems

Figure 5.5. Cooling from the top. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

For a cold surface placed in the upper part of a chamber containing the fluid, the following correlations can be used as a function of the flow regime:

- – for

;

; - – for

.

.

In these relations:

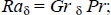

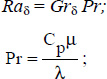

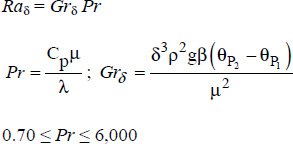

- – Ra is the Rayleigh number, defined by: Ra = Gr Pr;

- –

;

; - – the characteristic dimension, δ, taken into account in Nu and in Gr is:

- - δ = the side, for a square;

- - δ = average length and width for a rectangle;

- - δ = 0.9 D, for a disk (D = diameter).

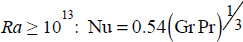

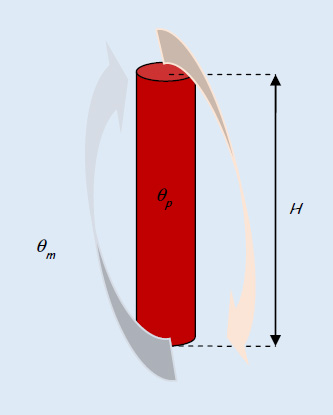

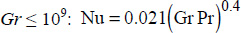

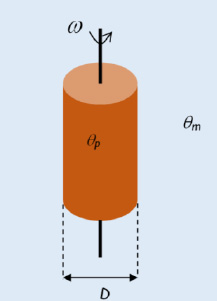

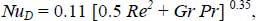

5.7. Vertical cylinders subject to natural convection

Figure 5.6. Vertical cylinder. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

The correlations obtained for vertical cylinders are (Gebhart, 1961):

- – for

;

; - – for

.

.

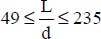

These relations are valid if:

- – the ratio of the cylinder diameter, D, to its height, H, satisfies the relation (Gebhart, 1961):

;

; - – the characteristic dimension taken into account in the Nusselt and Grashof numbers is the height, H:

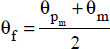

- – the physical properties of the liquid are taken at the average temperature of the film, defined by:

, where θpm is the average temperature of the wall and θm is the average temperature of the fluid.

, where θpm is the average temperature of the wall and θm is the average temperature of the fluid.

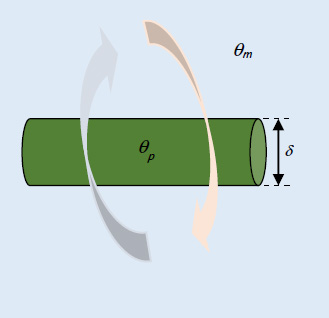

5.8. Horizontal cylinders subject to natural convection

Figure 5.7. Horizontal cylinder. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

In the case of horizontal cylinders subject to a natural convection, the average Nusselt number depends on the product, Gr Pr:

- – Gr Pr < 10-5: Nu = 0.49;

- – 10-5 < Gr Pr ≤ 10-3: Nu = 0.71 (Gr Pr)1/25;

- – 10-3 < Gr Pr ≤ 1: Nu = 1.09 (Gr Pr)0.1;

- – 1 < Gr Pr ≤ 104: Nu = 1.09 (Gr Pr)0.2;

- – 104 < Gr Pr ≤ 109: Nu = 0.53 (Gr Pr)1/4;

- – Gr Pr > 109: Nu = 0.13 (Gr Pr)0.33.

The characteristic dimension taken into account in Nu and Gr is the external diameter of the tube, δ.

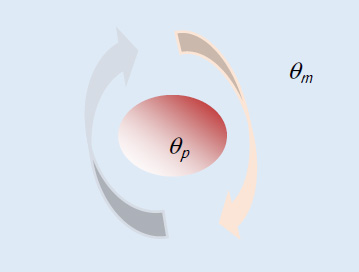

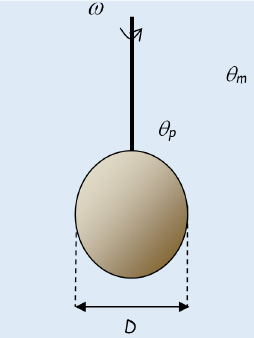

5.9. Spheres subject to natural convection

Figure 5.8. Immersed sphere. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

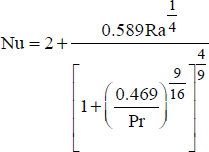

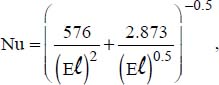

For a sphere of diameter D, we recommend using the following correlation to calculate the average Nusselt number:

This correlation is valid with:

- –

;

; - –

;

; - – Ra ≤ 1011 (Pr ≥ 0.7).

5.10. Vertical conical surfaces subject to natural convection

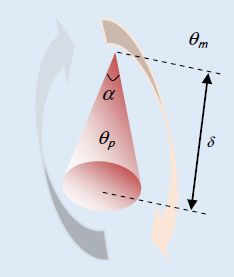

Figure 5.9. Immersed cone. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

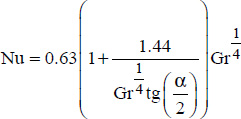

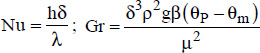

For conical surfaces subject to a natural convection, the following correlation can be used:

In this correlation:

- – the characteristic dimension to be taken into consideration when calculating the Grashof and Nusselt numbers is the height, H, of the cone;

- –

;

; - – α ≤ 12°.

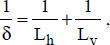

5.11. Any surface subject to natural convection

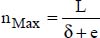

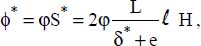

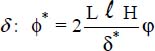

For any surface, and in the absence of the possibility of estimating the natural convection heat transfer coefficient, we can use the relations valid for vertical cylinders by choosing a characteristic dimension, δ, defined by:

where:

Lh is the length obtained by projecting the surface considered onto a horizontal axis;

Lv is the vertical projection of the surface.

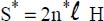

5.12. Chambers limited by parallel surfaces

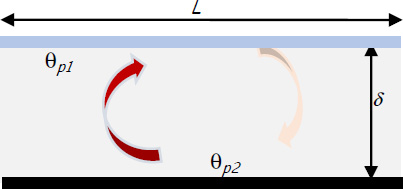

Figure 5.10. Fluid between two horizontal plates. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

Several practical situations implement a fluid (generally air) between two plates of temperatures θp1 and θp2, respectively (θp2 > θp1). This is the case for plane solar collectors, where the absorber constitutes the hot plate (at θp2) and the glazing constitutes the second plate.

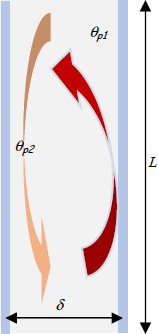

This type of configuration is also encountered in double glazing, used to minimize heat loss through windows. In the latter cases, the parallel plates are generally arranged vertically (see Figure 5.11). The hot plate can be either the plate that is in contact with the inside (as in a heated building), or that facing the outside (as in air-conditioning), according to the scenario.

Figure 5.11. Fluid between two vertical plates. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

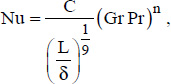

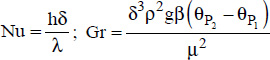

For such situations, the average Nusselt number is obtained from the following general correlation:

where:

δ is the distance between the plates;

The C and n constants depend on the position of the plates and the Grashof number. They are given in Table 5.1 below.

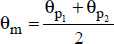

The physical properties of the fluid separating the two plates are taken at average temperature,  :

:

Table 5.1. Parameters C and n (*hot plate located at the bottom)

| Vertical plates | ||

| Condition on Gr | C | n |

| 2 105 < Gr ≤ 1.1 107 | 0.071 | 1/3 |

| 2 103 < Gr ≤ 2 105 | 0.20 | 1/4 |

| Gr ≤ 2 103 | Nu = 1 | |

| Horizontal plates* | ||

| Condition on Gr | C | n |

| 3.2 105 < Gr ≤ 107 | 0.075 | 1/3 |

| 103 < Gr ≤ 3.2 105 | 0.21 | 1/4 |

| Gr ≤ 103 | Nu = 1 | |

5.12.1. Correlation of Hollands et al. for horizontal chambers

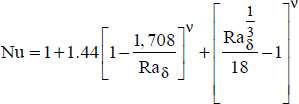

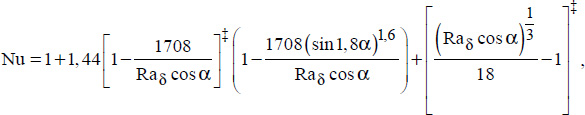

This is valid for gases at Ra δ< 108 and for water and liquids at Ra δ< 105. It gives the average Nu value as follows:

with:

where:

The exponent v indicates that the amount between the brackets is set to zero should it be negative.

5.12.2. Correlation of El-Sherbiny et al. for vertical chambers

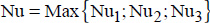

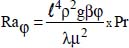

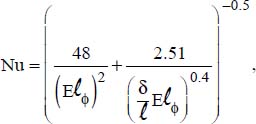

This correlation gives the average Nu value as being the maximum of three values, Nu1, Nu2 and Nu3:

where:

This correlation is valid for:

- – 10 ≤ Rad ≤ 2 107;

- –

.

.

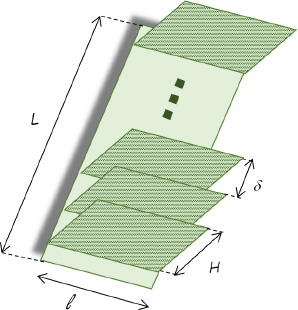

5.13. Inclined-plane chambers

Inclined chambers are encountered in solar applications, where in order to optimize the amount of energy collected, the absorber is required to be in an inclined position (see Figure 5.12).

Figure 5.12. Inclined chamber. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

For such chambers, the correlation to be used depends on the inclination, α, and on the ratio,  , known as the aspect ratio.

, known as the aspect ratio.

5.13.1. For large aspect ratios and low-to-moderate inclinations

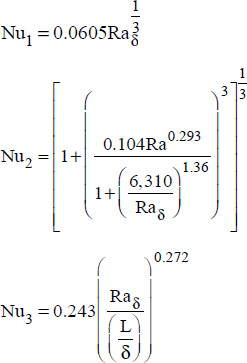

For  and 0 ≤ α ≤ 70° , we will use the following correlation (Hollands et al., 1976):

and 0 ≤ α ≤ 70° , we will use the following correlation (Hollands et al., 1976):

where:

The expressions of the type  need to be set to zero if Raδcosα < 1708

need to be set to zero if Raδcosα < 1708

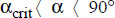

5.13.2. For lower aspect ratios and inclinations below the critical inclination

The critical inclination depends on the aspect ratio  . It is given in Table 5.2:

. It is given in Table 5.2:

Table 5.2. Critical inclinations

|

Critical inclination αcrit |

| 1 | 25° |

| 3 | 53° |

| 6 | 60° |

| 12 | 67° |

| > 12 | 70° |

For  and

and  , the following correlation is recommended (Catton, 1978):

, the following correlation is recommended (Catton, 1978):

5.13.3. For lower aspect ratios and inclinations greater than the critical inclination

Two situations are to be considered depending on the value of αcrit determined by the aspect ratio  (see Table 5.2):

(see Table 5.2):

Situation 1:

The following correlation is recommended (Catton, 1978):

Situation 2:

The following correlation is recommended (Arnold et al., 1975): Nu =1+(Nuα=90° −1)sinα.

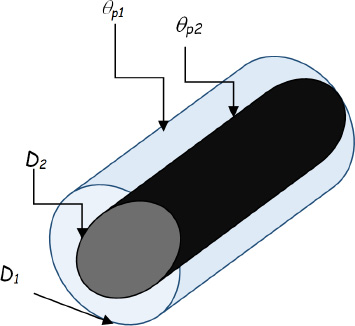

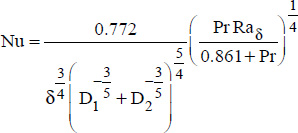

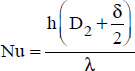

5.14. Chambers limited by two concentric cylinders

This type of chamber is generally used as a solar collector in parabolic-trough collectors of the type used in the Noor Ouarzazate power station in Morocco. They consist of two coaxial tubes, one made of metal (the inner tube), which conveys the heat-transfer fluid, and the other made of glass, which serves as a protective jacket. The fluid to be found in the annular space is generally air.

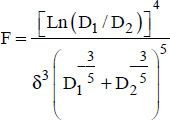

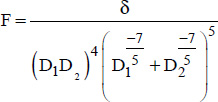

The linear flux (flux per unit length) between the absorber tube and the glass tube is given by Raithby as a function of an effective thermal conductivity λeff and a geometric influence factor, F (Raithby and Hollands, 1975). Yet the expressions proposed by Raithby introduce complexities that can be avoided.

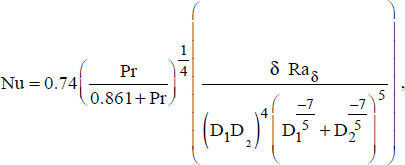

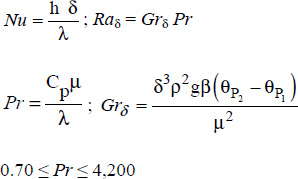

Indeed, the Raithby results can be placed in a simpler form, which directly gives the average Nusselt number, and therefore the average heat transfer coefficient, h, as follows:

where:

δ is the characteristic distance, defined by:

100 ≤ F Ra ≤ 1012 , where:

The physical properties of the fluid are taken at average temperature,  :

:

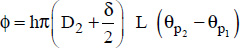

The flux, for a tube length, L, is then obtained by the convection equation:

or:

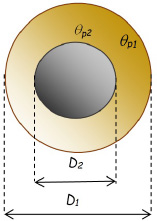

5.15. Chambers limited by two concentric spheres

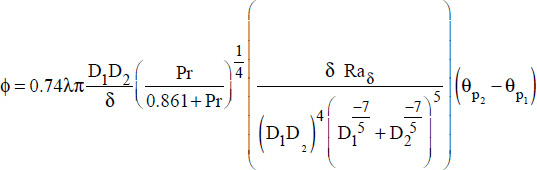

For concentric spheres of diameters D1 and D2 and of temperatures θp1 and θp2, respectively, Raithby developed an expression of the flux as a function of an effective thermal conductivity, λeff, and of the geometric influence factor, F (Raithby and Hollands, 1975).

Yet, as with concentric cylinders, the expressions proposed introduce complexities that can be avoided.

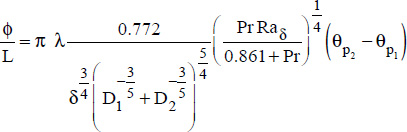

Indeed, the results obtained by Raithby for concentric spheres can be placed in a simpler form, which directly gives the average Nusselt number, and therefore the average heat transfer coefficient, h, as follows:

where:

δ is the characteristic distance, defined by:

100 ≤ F Ra δ ≤ 104 , where:

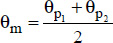

The physical properties of the fluid are determined at arithmetic average temperature:

The flux is then obtained by the convection equation: ϕ = hπD1D2 (θp2 −θp1) or:  .

.

I.e.:

5.16. Simplified correlations for natural convection in air

The correlations presented above for calculating natural convection heat transfer coefficients are for general use. They are also dimensionless, enabling them to be used without any concern for problems that may be posed by units.

Specific situations can be encountered in practice, particularly when air is used as the heat-transfer fluid, as is the case with the heating or cooling of electronic components by means of natural convection. For such situations, specific correlations may be considered easier to use.

The following sections present this type of correlations. The user should be aware that these relations need to be employed with great caution with respect to the units considered for each of the magnitudes applied.

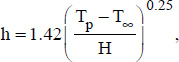

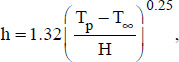

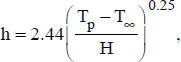

5.16.1. Vertical cylinder or plane under natural convection in air

where:

- – H is the height of the cylinder or plane considered, expressed in meters;

- – Tp and T∞ are, respectively, the wall temperature and the ambient temperature far from the cylinder or the plane surface, expressed in degrees.

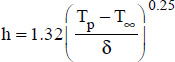

5.16.2. Horizontal cylinder or plane under natural convection in air

where:

- – H is the height of the cylinder or plane considered, expressed in meters;

- – Tp and T∞ are, respectively, the wall temperature and the ambient temperature far from the object in question, expressed in degrees.

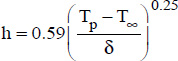

5.16.3. Horizontal plane under natural convection in air

The heat transfer coefficient depends on the way air flows over the hot surface:

- – when the air is above the hot surface:

;

; - – when the air is below the hot surface:

.

.

Where the various parameters are defined below:

- – δ is the characteristic length of the plane considered

, expressed in meters;

, expressed in meters;

- - where A and P are the plane surface area and perimeter, respectively.

- - Tp and T∞ are, respectively, the wall temperature and the ambient temperature far from the object in question, expressed in degrees.

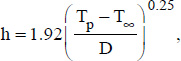

5.16.4. Sphere under natural convection in air

where:

- – D is the diameter of the sphere, expressed in meters;

- – Tp and T∞ are, respectively, the wall temperature and the ambient temperature far from the sphere, expressed in degrees.

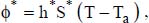

5.16.5. Circuit boards under natural convection in air

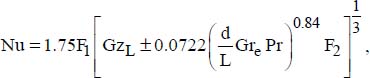

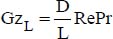

When circuit boards are cooled by natural convection in air, it is recommended to use the following correlation to determine the convective heat transfer coefficient between the boards and surrounding air:

where:

H is the height of the electronic board considered, expressed in meters;

Tp and T∞ are the board temperature and the ambient temperature far from the board, respectively, expressed in degrees.

5.16.6. Electronic components or cables under natural convection in air

For small electronic components or cables under natural convection in air, it is recommended to use the following correlation to determine the convective heat transfer coefficient between the components (or cables) and surrounding air:

where:

- – H is the height of the electronic component or that of the cable (in meters);

- – Tp and T∞ are, respectively, the component or cable wall temperature and the ambient temperature, expressed in degrees.

These relations are certainly helpful for rapid calculations to generate orders of magnitude of the convective heat transfer coefficients. Of course, for more accurate calculations, the dimensionless relations developed in the sections above are preferred. In addition, for calculations concerning electronic systems, the following section presents a methodology and calculations specific to heat sinks used for circuit-board systems.

5.17. Finned surfaces: heat sinks in electronic systems

During their operation, electronic components consume electric currents which, in addition to producing the desired effect, generate heat through the Joule effect. When the currents involved are significant (several amps or more), the amount of heat generated becomes so great that it can interfere with the normal operation of this component, and can even result in its disintegration, if the heat generated is not evacuated. This becomes critical when geometric constraints are imposed by design and/or ergonomic requirements, notably for embedded systems (US Department of Defense, 1992).

Thus, heat evacuation is an important parameter in the design of certain electronic systems to be used in, inter alia, telecommunications, audio equipment, avionics and computing. In a computer for example, the operation of several elements generates significant amounts of heat, particularly microprocessors (CPUs), graphics processors (GPUs), RAM, hard disks and power packs, etc. This is because these contain elementary electronic components whose operation is highly exothermic, namely, the integrated circuits that form part of most electronic assemblies. Indeed, microprocessors, such as Pentium™, Atom™ and Intelcore™, contain millions of transistors.

5.17.1. Dissipation systems

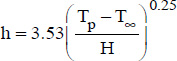

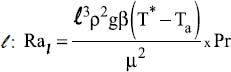

Natural convection is often sufficient in order to extract the heat produced by electronic equipment, but on the condition that it is boosted using accessories known as heat sinks (US Department of Defense, 1978). Figure 5.15 shows an example of a commercial heat sink designed to receive a transistor.

Figure 5.15. Transistor on heat sink assembly

When assembled on the electronic components concerned, heat sinks enable an increase in the transfer area between the electronic component considered and the neighboring air.

Heat sinks are generally composed of a metal that is a good heat conductor (copper, aluminum, etc.). In the trade, it is mainly aluminum heat sinks that are encountered.

Assembly involves screwing the electronic component onto the heat sink, making sure to insert a thermal-conductive gasket between the component and the heat sink. The latter is generally composed of a silicone or silver paste, a mica pad (the latter breaking easily, however), or a soft silicone pad (this being more practical and cleaner than paste). The role of each of these pads is to ensure thermal conduction while providing good electrical insulation (Kraus, Bar-Cohen and Wative, 2006). They can therefore be considered as insulators from an electrical perspective, but as conductors from a thermal point of view.

Yet natural convection can prove insufficient in some electronic systems. This is the case when we use performance enhancing techniques such as overclocking, which consists of exceeding the operating frequency prescribed by the manufacturer for a given component. Indeed, in such situations, operation of the electronic circuits generates such large amounts of heat that natural convection is no longer sufficient to provide the cooling needed in order to ensure stable circuit operation (US Navy, 1955).

We then use cooling systems based on forced convection, which can even draw on heat evacuation through latent heat, as is the case with spray cooling (Shicheng, Yu, Liping and Wengsuan, 2014). In such systems, in addition to the heat sinks assembled on the different components of the electronic boards, we use a fan to ensure satisfactory air circulation and, as a result, better heat transfer coefficients. This is the case for microcomputers, where a fan is often assembled inside the central processing unit box.

Although several heat sink systems exist that are based on forced convection (air, water or even liquid-nitrogen system, as in extreme cooling), above all their design falls within that of finned heat sink sizing, covered in Volume 6 of this series. In this section we will focus on systems using natural convection as the latter nevertheless remain the most frequently used for common electronic systems.

5.17.2. Thermal resistance of a heat sink

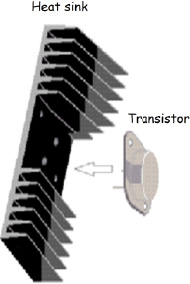

There is a very wide range of heat sinks available commercially, which differ in terms of their shape, and therefore their heat transfer areas (see Figure 5.16). Yet, in supplier catalogs, the values of the transfer areas are not presented, nor are the transfer coefficient values (see example in Table 5.3).

Figure 5.16. Different models of heat sinks for electronic assemblies

The heat sinks are presented with a thermal resistance. Of course, the latter depends on the geometry and the transfer area offered by a given model. Note that depending on the model chosen, the value of the resistance can vary from around 1°C/W to more than a dozen °C/W.

Table 5.3. Examples of thermal resistances in electronic heat sinks

| Model | RTh (°C/W) |

| 1 | 17.73 |

| 3 | 11.21 |

| 5 | 3.56 |

| 10 | 2.79 |

| 28 | 1.05 |

Let us nevertheless recall that this thermal resistance is above all determined based on the convection between the heat sink and the surrounding air, as the metal conduction resistance can be overlooked. It is of the form:

where:

- – h is the convection heat transfer coefficient between the heat sink and the surrounding air;

- – S is the transfer area offered by the heat sink to the surroundings.

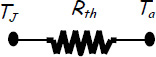

We generally represent transfers between the heat sink and the surrounding air with an equivalent electronic circuit (see Figures 5.17 and 5.18), where:

- – TJ is the junction temperature between the electronic component considered and the case representing the heat sink; it is the temperature of the component;

- – Ta is the ambient air temperature.

Figure 5.17. Simplified electrical representation of heat transfer between a heat sink and surrounding air

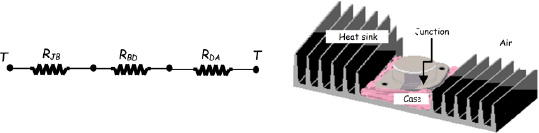

With all thoroughness, each of the thermal resistances interposed between the electronic component and the air should be taken into account.

Figure 5.18. Detailed electrical representation of heat transfer between an electronic component and the surroundings. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/benallou/energy3.zip

We then take into account the following thermal resistances:

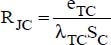

- – RJC: between the electronic component (the junction) and the case. It is a conductive resistance that depends on the thermal-conductive gasket used. Its value can be deduced from the thermal-conductor thickness, eTC, its contact surface area, SC, and its thermal conductivity, λTC:

- – RCS: between the case and the heat sink. Here too we are looking at a conductive resistance, the value of which depends not only on the thickness and thermal conductivity of the case, but also the thickness and thermal conductivity of the electrical insulator used;

- – RSA: between the heat sink and the air:

.

.

As the resistances RJC and RCS are generally the lowest (conductive resistances), optimization of the overall resistance will require minimizing RSA; the product hS needs therefore to be maximized.

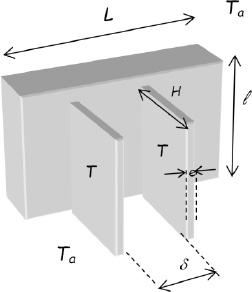

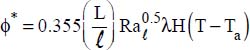

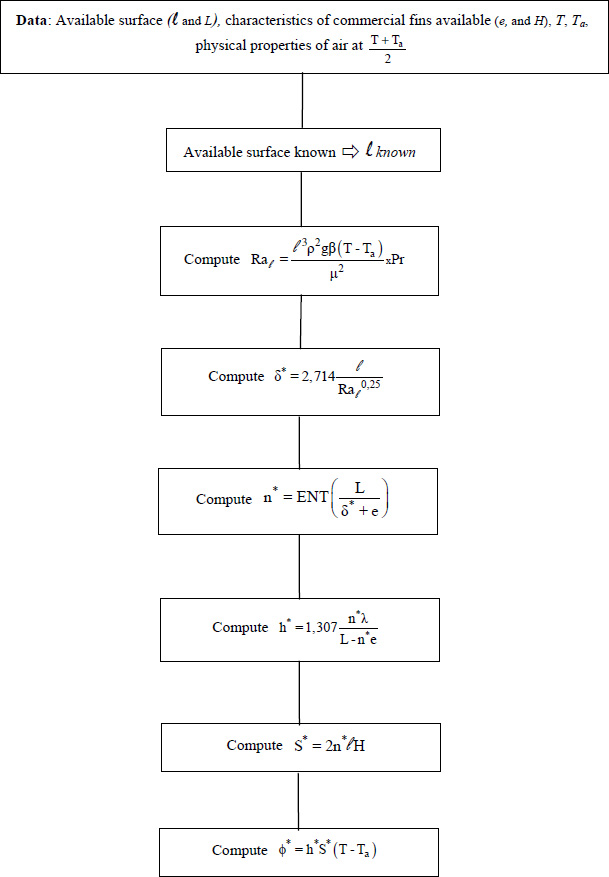

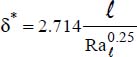

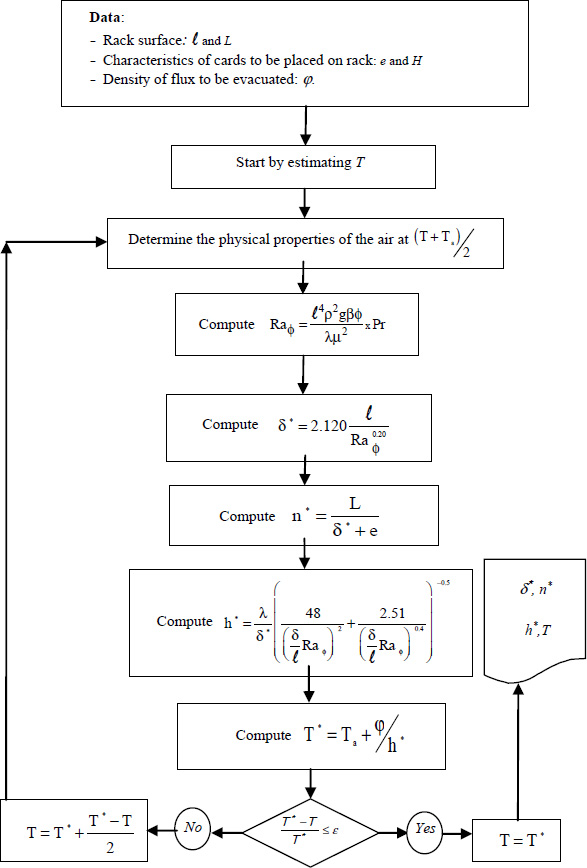

dimensions of the heat sink are determined by the space restrictions on the electronic board considered. When L is known, we can determine the maximum number of fins that can be put in place, namely:

dimensions of the heat sink are determined by the space restrictions on the electronic board considered. When L is known, we can determine the maximum number of fins that can be put in place, namely:

;

; ;

; ;

; ;

; ;

;

has been reserved for assembly of the microprocessor/heat-sink system. By choice, it is decided to ensure cooling of this microprocessor by natural convection. To this end, we select a commercially available vertical-fin heat sink with thickness e and dimensions

has been reserved for assembly of the microprocessor/heat-sink system. By choice, it is decided to ensure cooling of this microprocessor by natural convection. To this end, we select a commercially available vertical-fin heat sink with thickness e and dimensions  .

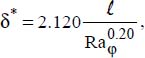

. is defined using

is defined using  .

.

.

.

as the characteristic length:

as the characteristic length:

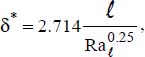

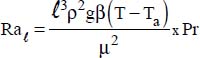

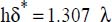

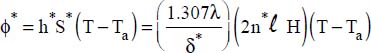

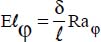

is the modified Elenbaas number, defined based on the flux density, φ

is the modified Elenbaas number, defined based on the flux density, φ

;

; and Ta are the temperatures of the board and the air, respectively.

and Ta are the temperatures of the board and the air, respectively.

.

.

.

. .

.

;

; , with

, with  ;

; and

and  for the Martinelli-Boelter correlation

for the Martinelli-Boelter correlation

.

.

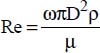

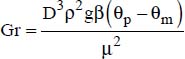

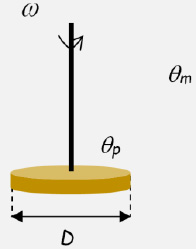

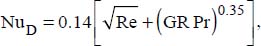

, where ω is the rotational velocity in revolutions per second;

, where ω is the rotational velocity in revolutions per second; ;

; .

.

, where ra is the rotational velocity (revolutions per second);

, where ra is the rotational velocity (revolutions per second); ;

; .

.

, where ω is the rotational velocity in revolutions per second;

, where ω is the rotational velocity in revolutions per second; ;

; .

.