CHAPTER 12

FLY FISHING

‘Angling may be said to be so like the mathematics, that it can never be fully learnt; at least not so fully, but that there still be more new experiments left for the trial of other men that succeed us.’

Paul: I’ve always gone fly fishing, but I’ve been doing a lot more float and ledger fishing since we’ve been doing the show. The TV programme’s reminded me just how much I enjoy it.

Bob: I am also going float and ledger fishing a lot more, given that I never actually went fishing at all until now.

PAUL

Since 1872, the firm of Hardy Brothers have been supplying fishing equipment to the great and good, and in their catalogue of 1907, they summed up the basic principles of fly fishing better than anything ever written since:

The art of dry-fly fishing is to present a fly that floats – and floats perfectly – to the notice of a rising fish in such a manner that it is mistaken for the natural ephemera which is hatching out, and in the result is accepted as such by the fish. To lure Salmo Fario successfully after this manner it is necessary that the angler should have skill; be very observant; have the patience of Job, and, beyond all, be properly equipped for the task.

Yes, they slip in some unnecessary Latin because they’re posh, and the last line is a shameful attempt to flog you one of their rods, but we can forgive them that.

I started doing a bit of fly fishing in my late teens, maybe 20s, and without question, fly fishing is widely seen as the most elite form of angling. It isn’t, but historically, it was seen as being so pure and unspoiled that it made all other methods of fishing seem positively coarse (which is exactly why it’s termed ‘coarse fishing’. Clearly, when they had the meeting to decide what the various forms of fishing should be called, the roach and tench fishermen arrived after the final vote had been cast).

Before I go any further, I should probably tell you where I stand on this thorny issue: I don’t really pay it any attention and I certainly don’t want to make it worse. Look, coarse and fly fishing have a lot of similarities and some notable differences, but fishing is a broad church and it’s silly to argue that one method is inherently superior to any other. So long as the angler is enjoying him or herself and the fish are treated with respect, then that’s fishing at its best.

When I go out, I do prefer the fly, but in recent years, I’ve re-discovered the joy of trotting a float – something I did with my dad and my mates growing up. I’d wager that a lot of the people who do fly fishing started as coarse fishers. And if you asked me to go out for a day doing either, I’d bite your hand off, whether we were going for salmon or perch. It’s horses for courses.

And let me make it clear, the absolute last thing I want to do is in any way irritate or put down carp fishermen. After all, I’ve seen the terrifying hardware they employ to catch carp – a quarry they love and respect. And I don’t want to think about the hi-tech weaponry they’d use against me if I upset them and they turned on me. I wouldn’t stand a chance! If I upset the carp fishing community, you’ll know, because I’ll be found lying dead on a canal towpath or in the bushes at a commercial fishery within 24 hours of this book hitting the shelves.

The two main branches of freshwater fishing in the UK are defined by the spawning times of the species involved and also some colossal historical snobbery based on the class system we all enjoy in these islands.

Actually the British class system has been good for two things: humour – oh, how we laugh at the upper, middle and working classes – and some exquisite country houses and estates that the ‘poor’ aristocracy now have to open to Joe Public. We can snoop around their gaffs to our heart’s content before pondering how emotionally fragile the nobility have become; it’s obvious to them now that they’re no better than the rest of us. Rant over.

But this mob in their Victorian heyday were the ones responsible for defining freshwater fishing as either game (salmon, sea trout, trout) or coarse (barbel, carp, roach, perch, chub, pike … In fact, all the other species that swim, including grayling). However, grayling are a slight anomaly in that they’re often fished for with a fly or nymphs but live in the same rivers and conditions that trout and salmon like. They also share an adipose fin with trout and salmon but have their oats at the same time as the roach and tench. I’ve confused myself now! This makes grayling difficult to categorise.

As you might have gathered, I love all branches of angling and certainly don’t see one method as inherently superior to another. But I enjoy fly fishing the most, closely followed by trotting a float or watching that float against a backdrop of lilies and fizzing tench bubbles.

Fly fishing appeals to me because I don’t have to cart loads of gear or bait around with me. A day fly fishing on a river requires little more than a nine-foot fly rod, a reel and line, a box of flies and various small accessories, snips, leader material, floatant and so on, all of which can fit into a pocket or two in a fishing vest. You can be ultra mobile … that sounds a bit too dynamic. You can wander freely up and down the river, enjoying the timeless wonder of the English countryside, the wildlife, the roar of fighter jets as they scream overhead, shattering the tranquillity as you search for an interested, rising fish. Even salmon fly-fishing tackle can be simplified to suit the prevailing conditions and allow you to roam free in your mighty chest waders. If there’s not much happening on the angling front, take time to study nature, think about your loved ones, maybe compose some poetry or contemplate just how big a halfwit Bob Mortimer is.

Like the hunter, the fly fisherman stalks his prey, actively tracking it down, getting eyes on it, attempting to second-guess its next move, before taking that one single shot with a rod, which, if accurate, will bag him his prey. As such, fly fishermen often unfairly portray bait fishermen as mere trappers, lurking in a shrub in the drizzle, spending the empty, endless hours waiting for a bite. Unlike the debonair fly-fishing gentleman, who strides around the roaring river in full flow, picking his shots with dazzling accuracy and pulling out game fish the shape, colour and value of bars of silver.

This is, of course, arrant nonsense. Whatever your quarry and whatever your method as a fisher, you have to become immersed in the environment and be stealthy rather than invade it; unless you’re a carp fisher, because a lot of them do look like they’re going to Helmand Province.

It’s pointless to claim one form of angling is better than another. I mean, if you boil it down to its bare bones, fly fishing is just the act of conning a fish with a home-made insect, which barely resembles the actual insect we’re trying to imitate. Hardly the pinnacle of human artistic achievement, but fly fishing for our usual quarry – salmon, trout, sea trout and grayling – often takes place in some of the more rural, untamed and wild places. Some places of staggeringly raw beauty and some historically managed environments with extraordinary water quality and purity.

If I had to pick one form of fishing it would be for salmon with a fly, or more accurately, a lure, tied to represent a small fish or a shrimp on which salmon feed at sea. Salmon are truly wild creatures that are often hard to catch. That’s an understatement because the buggers don’t actually eat anything at all when they’re in our rivers, so catching one with a tasty-looking morsel seems to be the triumph of a fisherman against not just a fish, but logic itself.

And once hooked, these lads fight to escape with power and passion. These fish have effectively evolved with two distinct urges: (i) to get back to the rivers they were born in so they can spawn, and (ii) not to get killed before they do. Many of these fish will have spent months travelling thousands of miles through the vast Wild West of the open sea, avoiding predators on a constant basis, always paranoid, always wary, always suspicious.

Amongst the obstacles to their extraordinary journey a thousand or so miles back from their feeding grounds around Greenland are any number of predators, including dolphins, seals, industrial fishing vessels, more seals, otters, netsmen and Whitehouse (the latter being the least successful of the salmon’s natural predators).

The take of a salmon to a fly is something so magical that it’s impossible to describe so I’m not even going to try. But once you have them on the end of a line, that’s not the end of the matter – not by a long chalk. These fish EXPLODE and will do anything and everything imaginable in their power to escape. It’s amazing to witness their sheer iron will to live and their ceaseless determination to be free. Honestly, the moment you catch a wild salmon or a big sea trout on fly tackle, you have never seen so much life being lived so vigorously in such a small amount of space.

With this in mind, losing a fish is nothing to be ashamed of or to be irritated about – it’s all part of the rough and tumble of the sport. So the fish managed to win that round – ‘Well played, fish, you were a most worthy opponent who got the better of me this time!’ – and you dust yourself off, straighten your rod, and get straight back into the game for round two. Let me just say here though that doesn’t mean you should be in any way proud if a fish breaks your line. That is just not on. It means you haven’t prepared properly or are using inappropriate tackle. Unless there are extenuating circumstances, I will shun you!

The art of fly fishing cannot be mastered. Even the most experienced fly fisher, with a lifetime of practice and a casting arm that can castrate a passing bluebottle in the blink of an eye, will be outfoxed by many, if not most, of the fish he comes up against.

But if the fly fisherman is consistently successful, it’s nothing to do with luck – it’s the direct result of their command of the art. Success in fly fishing depends on the countless tiny decisions the fisherman makes before the line is even cast, and subsequently, the skill to execute those decisions exactly.

Or if there are no fish rising, the fly fisher has to cast the fly into likely-looking spots, or use a sub-surface nymph and try to induce a take from a fish by imparting movement to duplicate the action of the insect he’s copying.

And that’s just the mechanics of the fishing. Fly fishermen don’t only need to be able to cast to the precise spot they choose, but understand why that exact spot is the right one. Once they’ve spotted a rising fish, they have to try and decipher their meaning – has the fish risen and dropped back down, but remained in place? Or did it pop up just as it was swimming away? If it did swim away, how far might it have gone? In which direction? Two feet downstream? Or ten feet towards the bank? Has it taken off entirely? Even if he can see the fish through the water, where should he place the fly to have the best chance of it being taken – directly above the fish? Or a foot away so it drifts down on the current? Should he move it to mimic a real fly? Or will that spook the fish?

The answer to all these questions is – there is no answer. And frankly, it’s doing my nut in! But you need to decide swiftly, or the moment will have passed. Experience is the only thing that can guide you through these endless questions, and even then, there are no guarantees.

If there were, fishing would lose its mystery and appeal. There is an old adage about fishing hell being to see a fish rise, casting to it and catching it. Seeing a fish rise in the same spot, casting to it and catching it, seeing another fish rise, casting to it and … you get the picture … the same fish from the same place ad infinitum, ad nauseam. I think that’s the correct Latin but we didn’t do Latin at my school. Ask Bob, he trained to be a lawyer.

So it’s about making quick decisions that come with experience and practice and if fortune isn’t against you, you’ll have taken on nature and won.

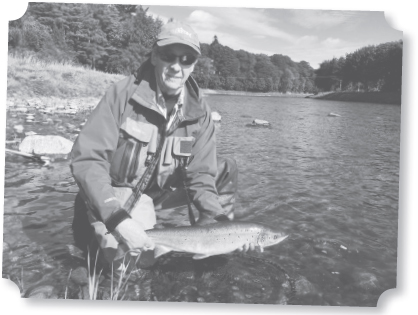

I remember I was once salmon fishing on the River Dee, where I go quite a lot. I saw a fish move quite a long way out, so I got into the river, waded out and I cast a specialist cast called a single spey cast. The fly swung round sweetly and the line drew out magically as the fish took straightaway and I landed it. I was only able to catch that fish because I’ve been doing it for a long time, so I instinctively knew what I had to do. I knew I’d have to wade to a certain point, I knew exactly where the fly needed to land above the fish, I knew the only cast that would get out there was quite a specialist cast, and I knew the fish was going to take because of the way it moved. I wasn’t consciously thinking of every stage – I just knew what I had to do, and I knew every step I had to make to make it happen. And it did.

Mind you, let’s get it right: there are loads of times I’ve done the same thing with absolutely no result!

But I remember that fish so well, because as I caught it I thought, a lot of experience and accumulated knowledge over the years has gone into catching that fish. It wasn’t a particularly big fish at all – it was just a coming together of circumstances that made it very memorable. That was a terrific sense of achievement.

To head out armed only with a thin rod, a line, a handful of fluff and hard-won years of experience, and end up catching a beautiful wild fish – to me, that’s angling in its simplest, purest, most thrilling form.

There’s one other big bonus about fly fishing: it liberates you from the tyranny of tackle. No more maggots in a bucket, stinking of ammonia and inevitably getting loose in the car. You only discover some of them escaped a week or so later, when you’re about to set off to the supermarket on a warm summer morning and open the door of the Auris to find it packed full with so many bluebottles, it’s like you’re in a deleted scene from The Amityville Horror.

When I was just starting to go salmon fishing, I knew this fishing tackle dealer from Birmingham. He said to me one day, really sadly,

Paul: Me and the fish from the river Dee.

‘Listen, Paul, I’m fed up of the maggot game. I don’t want to spend my life scrabbling about with maggots.’ And I understood exactly what he meant. In the words of FH Halford:

…the cleanest and most elegant and gentlemanly of all the methods of capturing [fish]. The angler who practises it is saved the trouble of working with worms, of catching, of keeping alive, and salting minnows, or searching the river’s banks for the natural insect. Armed with a light single-handed rod and a few flies, he may wander from county to county, and kill trout wherever they are to be found.

It’s hard to disagree with any of that. Apart from the bit at the end where he suggests killing as many trout as you can wherever you can find them. However, since I started trotting for grayling again about seven or eight years ago – and especially since fishing with Bob and the great John Bailey on our series – I’ve fallen back in love with the maggot. It’s like we’ve never been apart. Be still my beating heart.

THE HISTORY OF FLY FISHING

Fishing with a rod, line and an artificial lure created to imitate the prey of fish – those three essential ingredients of fly fishing – was first recorded in the year AD 200, when the Roman author Claudius Aelianus watched some Macedonians fishing in the Astraeus River:

… they have planned a snare for the fish, and get the better of them by their fisherman’s craft… They fasten red wool…round a hook, and fit on to the wool two feathers which grow under a cock’s wattles, and which in colour are like wax. Their rod is six feet long, and their line is the same length. Then they throw their snare, and the fish, attracted and maddened by the colour, comes straight at it, thinking from the pretty sight to gain a dainty mouthful; when, however, it opens its jaws, it is caught by the hook, and enjoys a bitter repast, a captive.

That said, Claudius might not be the most reliable source: in his De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals), he claimed that beavers were famous for gnawing off their own testicles to throw into the path of pursuing hunters, so best to take everything he says with a pinch of salt.

While it’s most closely associated with the Victorian era, fly fishing had been practised in England for centuries – Dame Juliana Berners and Izaak Walton’s books both have considerable sections about making artificial flies.

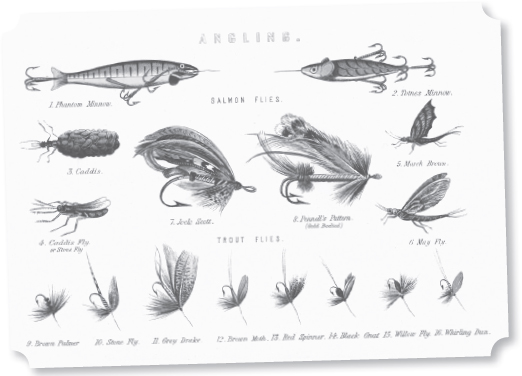

Alfred Ronalds’ The Fly-fisher’s Entomology (1836) was the first book to start giving names to individual artificial flies and detailed instructions on the time of year to use them.

An engraver by trade, the pages were full of beautiful, accurately realised illustrations, and his scholarly book helped to foster the serious and academic air that the majority of books on fishing still employ today (this one, I’m aware, is the exception that proves the rule). For better or worse, Ronald was the man who laid the groundwork to turn the act of simple fishing into a complex and gravely serious science.

The success of the book led to the longest lasting legacy that the Victorians left to fishing: the development of the art of the artificial fly. The creation of little handmade fake flies – which were designed to trick a particular fish on a particular day, often at a particular hour – with just a handful of feathers and thread distilled the main four Victorian passions into one respected pastime. It combined engineering, scientific learning, technical ability, and it kept your hands occupied for hours, so you wouldn’t be tempted by the dark delights of sexual self-pleasure.

Paul: An early collection of salmon and trout flies with a couple of spinning mounts from less enlightened times.

The art of making your own flies – fly-tying – became more than a hobby during the 1800s: it was a mania. A lot of factors contributed to this perfect storm: the Victorians loved to classify and catalogue anything and everything. Crafts and handiwork were universal pastimes. The natural world was in vogue (let’s face it, they pickled most of the natural world and put it in jars). As the publishing industry grew, more people had access to books and could read up on the latest developments in fishing methods. And the study of entomology was as popular as it would ever be, with insects celebrated in art, fashion and design for their beauty and strangeness.

All these different things led to huge numbers of fishermen and academics becoming utterly obsessed with understanding every stage of the life cycle of particular insects, which they’d then try to replicate using whatever came to hand from feathers and beads to silk, furs and tinsel.

The flies came with fantastic names, all of which remind me of Bob’s favourite cat names – the Bronze Pirate, the Fairy King, the Silver Doctor, Hairy Mary, the Stoat’s Tail, Munro’s Killer, Thunder and Lightning, the Green Highlander, the Grizzly Spider and McCaskie’s Green Cat. I could go on and on listing these for days – there are literally tens of thousands of different varieties.

I’ve made my own flies in the past and I completely understand just how gloriously satisfying it can be. Tying your own variation on a pattern that’s existed for 200 years and then going out and catching a fish with it – it’s a little bit magic. It’s especially pleasing if you can use materials that are just lying around – some thread, a few feathers – to create a perfect illusion that catches your dinner for you. It’s an extraordinary experience from start to finish, and I can see why people become obsessed with it.

Apart from anything else, if you can get obsessed with the process of making flies enough, then you might find yourself in the lucky position where you don’t then feel the need to go out and do the horrible, dirty old fishing bit. You could just sit at home, in the warm, go, ‘Right, that fly’s perfect, I’ll put that in me box, put the telly on and reach for me drink.’

In 1895, George M Kelson’s The Salmon Fly: How to Dress It and How to Use It convinced a new generation of fishermen that the best artificial flies needed to be made from exotic bird feathers. Partly, this reflected the fact that Britain had so many colonies across the globe, so these fancy feathers were readily available to those who could afford to buy them. Such was the demand for exotic bird plumage that when the RMS Titanic sank in 1912, the most valuable and highly insured contents in its hold was 40 crates of feathers.

To make a Jock Scott fly (named after its creator, a Scottish gillie), which is regarded as being the most remarkable, beautiful, intricate and hard-to-source of all the flies, and takes five or six hours to make, you needed feathers from the golden pheasant, guinea fowl, a peacock, a jungle cock and a fucking toucan.

Today, a newly made Jock Scott with genuine feathers will cost you upwards of £500. The original Victorian examples fetch huge prices today – not for use in fishing, but as works of art in their own right.

For most of us, if you wanted to make one of these Victorian beauties today, then you’d better hope the Natural History Museum have a tackle shop hidden away at the back.

Or you could do what Edwin Rist did.

In 2009, Rist – a 20-year-old flautist from Willesden Green who was studying at the Royal Academy of Music – broke into the Zoological Museum in Tring and stole nearly a million pounds’ worth of bird feathers from their collection.

On a cold and dark Bonfire Night in 2008, Rist was escorted down to the museum’s archive, where a quarter of a million bird skins were laid in storage. He had told the museum attendant that he was taking photographs on behalf of a graduate student who specialised in birds of paradise. What he was actually doing was casing the joint.

Six months later, Rist returned to the museum in Tring – only this time at night, scaling a wall, cutting through barbed wire, breaking a window, sneaking into the archive and frantically stuffing a suitcase with as many rare bird skins as he could. By the time he got back to Tring station at 3:00am, his case was bulging with nearly 300 rare and critically endangered Victorian bird skins, worth over half a million pounds.

Rist’s crime – which at first seems utterly unfathomable – was motivated solely by his passion for salmon fly-tying. Since he was ten, he’d been making his own flies, but he’d been spellbound at a fishing show by a display of Victorian flies and dreamed of making his own. He’d become involved – this isn’t a joke – with a shadowy underground online community of Victorian rare-feather fly-tiers, one of whom lived by the motto ‘God, Family, Feathers’. Unable to afford these rare feathers to make the elaborate classic flies – a blue chatterer alone can cost over a grand – Rist decided to steal them.

What’s even stranger about the story is that Edwin didn’t fish. By all accounts, he’d never been fishing: he was just obsessed with the flies.

A year later, Rist was caught, and was sentenced to a one-year suspended sentence. Nearly half of the bird skins were never recovered. Rist added that he sold some in order to prop up his parents’ failing Labradoodle breeding business – in less than a year, he made over £125,000. He’s now changed his name and plays in an orchestra in Germany. It’s the oldest story in the book.

A much more celebrated 20th-century fly-tier was Megan Boyd, an elderly woman who lived and worked in a rural village on the east coast of the Scottish Highlands. From her teenage years onwards, she spent her life making Victorian-style flies, supplying first the local fishermen and then, through word of mouth, outsiders. Ultimately, she ended up making flies for Prince Charles, who visited her at her little cottage on numerous occasions, even though it had no electricity or running water.

Boyd kept the Victorian fly-tying tradition alive well into the 21st century, but she was never an angler – she couldn’t bring herself to kill a living creature, and, as a friend told a newspaper, ‘She was there to catch the fishermen, not the fish.’ Her own design of fly – called the ‘Megan Boyd’ – is famous for attracting salmon in summer when the water is low.

Boyd was awarded an MBE for her work tying flies (although she didn’t go to the palace as she said she had no one to look after her dog) and after her death, her life became the subject of the 2014 feature-length documentary, Kiss the Water. Today, there are boxes of Boyd’s flies in museums across the world and originals sell for thousands.

What’s odd is that the majority of the most valuable flies that the Victorians created would never be used by any anglers today – not in a million years. And it’s not just because they’re so valuable and fragile that you wouldn’t want to take the risk of losing one in the branches of a tree on the opposite bank.

They might be spectacular to look at, but they’re entirely unsuitable for catching fish. In fact, these large, layered feathery clumps of brightly coloured feathers would be more likely to startle, spook and scatter any fish as a result of their totally alien appearance. You might as well chuck a lit Catherine wheel into a river (don’t get any ideas, Bob).

For most of its history, the main form of trout fishing was what we now call wet fly – meaning the lure fished under the surface of the water, much like bait. But anglers on rivers with a chalk bed (like the Test, due to the clearness of the water) began to experiment with fishing the adult stage of the fly on the surface. Step forward, dry-fly fishing.*

Fishing with a dry fly saw the fly cast out to land on the surface of the water – it’s termed ‘dry fly’ because it doesn’t enter the river, as opposed to the wet fly, which (and you’re probably ahead of me here) does.

The technique was first proposed in print by WC Stewart in his 1857 book, The Practical Angler; Or, The Art Of Trout Fishing More Particularly Applied To Clear Water.

Stewart was a lifelong angler and in the opening of his book, he rages against the then-current perception of fishing by the general public:

…there are few amusements which the uninitiated look upon as so utterly stupid; and an angler seems generally regarded as at best a simpleton, whose only merit, if he succeeds, is that of unlimited patience.

I think this feeling of being looked down upon is quite important to the history of fishing, as it influenced the way Stewart determined how to present his new techniques to the world: as a science, worthy of admiration and respect, and an art, practised only by those who were well educated in its complexities. Fed up of people thinking they were morons, Stewart did a remarkable 180-degree turn to reframe anglers as deep-thinking men of learning, using methods so technical that they were beyond the understanding of your common or garden non-anglers (bang on, Stewie, with one notable exception!).

Honestly, I think there’s still some vestige of Stewart’s defensiveness which hangs over the sport today – a lot of non-fisherfolk have an outdated sense that anglers are a tight-knit and unwelcoming community who are loath to bring inexperienced outsiders in. In my experience, the opposite could not be more true (save for a few fishermen I’ve met, who I’ll admit were absolutely awful people. But that’s not specific to anglers, it’s true of humanity in general. You’re just as likely or unlikely to meet a loathsome baker as you are a horrible fisherman).

Mind you, it doesn’t help that anglers, like lawyers and criminals, have an entire vocabulary that must seem strange and alien to your average layman, nearly all of it introduced by the Victorians and only ever used in fishing circles.

We talk non-stop about trotting, rises, gentles, creels, fry and tackle. Some of the words we use don’t even mean what you’d think they do – groundbait, for example, doesn’t go on the ground, it goes in the river. Fly-tying isn’t tying a fly onto your line, it’s the process of making the fly from scratch. And that’s before we’ve even got started on our bloody knots and flies. Carp fishing has its own language practically.

Fishing can seem utterly perplexing to the outsider, and you could make a case that the moment this intimidating language began can be traced back to that moment in 1857 when an indignant Stewart first put pen to paper.

What Stewart did was create a branch of angling which was different from the poor working man’s humble fishing, and could thus be embraced by the aristocracy. This wasn’t grubbing around in the dirt for maggots and having a fish force you to sit still for hours until it deigned to eat. Now fishing was about book learning! The thrill of the chase! The hunting instinct! Accuracy and sportsmanship! Deeply understanding the natural world! And not being poor!

In the late 1800s, Stewart’s technique was advanced by the previously mentioned Frederic (FH) Halford, who wrote a number of hugely influential and acclaimed books on his new method. His work was once held in such high regard that Halford is known today as ‘the Father of Modern Dry-Fly Fishing’.

In 1866, his Floating Flies and How to Dress Them became a huge bestseller – but his next book, Dry Fly Fishing in Theory and Practice (1889), became an aquatic bible to an entire generation of fishermen. Fishing the clear waters of chalk-bottomed rivers like the Itchen, the Kennet and the Test, he came to the conclusion that traditional wet flies looked nothing like the sort of insects that fish would encounter underwater, so he believed they were ineffective at best. Instead, he developed the upstream dry-fly technique.

While it most likely wasn’t a totally new method, Halford’s technique was to accurately mimic a fly landing on the surface of the water upstream of a trout. Trout face upstream, waiting for food to come down to them, so the fly would gently drift down. It would look exactly like the fish’s regular source of food, being carried along by the flow. This, said Halford, meant they were more likely to rise.

His method also required incredible skill when casting, as you needed to silently land the fly at a spot directly above a rising, fish and hope it went along with the charade.

Halford believed casting a dry fly over a rising fish wasn’t just a more effective method of fishing: he believed it was the only scientifically correct form of fishing.

On one point all must agree, viz., that fishing upstream with fine gut and small floating flies, where every movement of the fish, its rise at any passing natural, and the turn and rise at the artificial, are plainly visible, is far more exciting, and requires in many respects more skill, than the fishing of the water as practised by the wet-fly fisherman.

Halford was utterly fundamentalist about his dry-fly method. He notes in his book that he would ‘not under any circumstances cast except over rising fish, and prefer to remain idle the entire day rather than attempt to persuade the wary inhabitants of the stream to rise at an artificial fly’.

The dogmatic approach that Halford took in his books spawned a devoted cult of hard-line dry-fly acolytes, who followed his teachings with an almost religious fervour (it’s no surprise that he was also called the ‘High Priest of Dry Fly’). In short, if you were wet-fly fishing after his book was published, you were a heretic.

And, as with any major religion, even within his band of followers, there were schisms between factions: in this case, the purists and what Halford called ‘the ultra purists’.

Those of us who will not in any circumstances cast except over rising fish are sometimes called ultra purists and those who will occasionally try to tempt a fish in position but not actually rising are termed purists (and I would urge every dry-fly fisher to follow the example of these purists and ultra purists). But in the early years of the 20th century, one brave soul stepped forward to challenge Halford’s teachings. George Edward Mackenzie Skues (most commonly known as GEM Skues, which reads like the name of a really contemporary rapper out of Atlanta) was a lawyer and (some claim) the greatest fly fisher of all time.

In 1887, Skues bought a copy of Halford’s Floating Flies and How to Dress Them and began experimenting with his own dry-fly techniques. As he went along, the former lawyer wrote about his new findings in the fishing press, rigorously examining every technique he used again and again until he was certain of his verdict (no doubt like Mr Mortimer did in his formative years in the law).

Skues collected his new articles in Minor Tactics of the Chalk Stream (1910) and The Way of a Trout with the Fly (1920), which caused a sensation in the world of dry-fly fishing. Firstly, he disagreed with Halford over sunken flies, which he believed were a legitimate tool in the angler’s arsenal. But most controversial of all was his new creation: the nymph.

Skues invented a fly that imitated the nymphs – the larval stage of aquatic insects – that trout feed on underwater, which make up about 80% of their entire diet. His masterstroke meant he could silently slip his replicant into the middle of a big hatch and the ensuing feeding frenzy at the very moment the fish’s guard was completely down.

If anything, Skues’ method takes even more skill than Halford’s. Upstream dry-fly fishing requires you to see a rise, cast to it, and then your fish might take it; with nymph fishing, you have to see right into the water, catch the little flash of the trout’s open mouth, then judge where your cast needs to land to reach the fish below the surface and then decide if the fish has taken it.

Surprisingly, fishing with a nymph became immediately controversial, because it was seen as being too effective. It seemingly made the catching of trout a fait accompli. It was even called ‘unethical’ to use it, and the argument between Halford’s disciples and Skues’ gang quickly became fishing’s version of Mayweather-McGregor.

One thing has remained constant since the days of Halford and Skues: whenever there’s innovation in fishing, you can be sure that a big flare-up between the traditionalists and early adopters will follow right on its heels.

In 2008, trout fishermen using traditional methods became incandescently angry over the use of ‘blobs’. Also known as attractors, blobs are brightly coloured lures that look nothing like insects, but when they’re whipped through the water, trout cannot stop themselves lunging at them and chasing them until they’re caught (allegedly).

But the use of blobs caused a storm that rages to this day. The England fly-fishing champion Chris Ogborne was quoted by the Telegraph, saying, ‘Fly fishing is about imitating things that fish eat. Blobs are fundamentally bad for the sport. It’s a very easy way of catching a lot of fish and takes the skill away. Any idiot can use them.’ He was so furious about people using blobs that he resigned from the England team.

But the reaction comes from the same place as those who railed against the nymph: a love of fly fishing, and a genuine desire that future generations get to enjoy the same sport that’s brought so many of us such long-lasting and total pleasure.

So if the history of fly fishing has taught us anything it’s this: fish in a way that makes you happy. If you fancy trying fly fishing, give it a go. I hope you end up loving it as much as I do. If you buy a fly rod, the Fly Fishing Association of Great Britain aren’t going to break into your house at night to make sure you aren’t going out coarse fishing any more. No one’s going to push you in the river if you can’t cast perfectly on your first go.

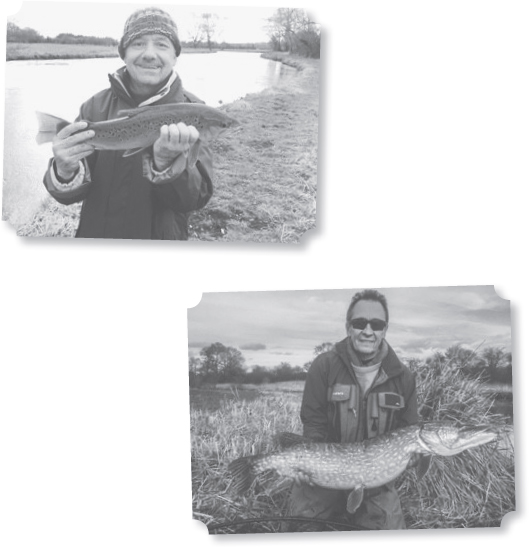

Paul: Bob with a float/maggot-caught trout. Halford and Skues will be practically fracking, they’re turning in their graves so much. The big pike was caught on the fly on the same trip.

Use a fly. Use a fly you make yourself. Use a nymph. Use a blob. Look, if you want to use a three-grand original Victorian fly made out of bloody dodo feathers, no one’s going to stop you (unless it turns out to be one of those ones from Tring that the police didn’t manage to recover. I can do you a few at a very reasonable price … shhhhh!).

THE BASICS OF FLY FISHING

Fly fishing is an extremely specialised way of fishing so all I’m going to do here is give you some of the basics.

There are a lot of books out there, which take you through the technical side of fly fishing in great detail, but until you’ve had a few hours at the riverbank, they’re not going to open any doors for you. Knowing the theories of fly fishing inside out is all very well, but fish couldn’t care less what you know about theory.

The only way you can learn how to fly fish is to fish with a fly fisherman. There’s so much in the skill of casting a fly that can only be learned with experience. I can tell you what you need to cast, but it’s the same as me telling you where to put your feet and then expecting you to be the prima ballerina for the Bolshoi Ballet.

There are some great online tutorials that can help a lot. In fact, I should practise a lot more as my technique needs brushing up and leaves a lot to be desired. You are always learning – or you should be!

One of the significant differences between bait and fly fishing is in the casting technique. The main one is that in bait or spin fishing, the weight of the float, ledger or spinner at the end of the line is what loads the rod when you cast. With fly fishing, the line is the weight. It’s solely the weight of the line that loads the rod when you cast.

As such, fly-fishing line is much thicker and heavier than the line used in coarse fishing (there you use a very thin line – literally, the line of least resistance). So the line is what you use to cast your fly.

God knows what they’re actually made of, but there are countless varieties. You get a low-stretch core with a plastic coating, you can have a floating line, an intermediate, a hover; you can have a very slow sink, a fast sink, an extra-fast sink, a tungsten core that will get you right down – there’s the lot.

For a beginner, I’d stick with a floating line. Later, you might want a slow sink line for some lure fishing, but to start with, especially in rivers for trout, use a floating line.

There are various profiles of fly lines as well – they have a weight forward that loads rod a bit more easily, so you’d probably start with something like that.

When starting out, you want a rod of about 8 foot 6 inches to 9 feet. All the line and rods are rated. It’s called an AFTM rating. That way, you can match the line to the rod. To start with, you’d want a line weight of about 6, so you’d buy a 6-weight line and a 6-weight rod.

The fly reel is a form of centre pin, but it’s got a check on it. It’s not a free running centre pin, it’s always on a check, so you’re not letting the line free spool.

On the end of your fly line, you attach a leader. This can be monofilament, fluorocarbon – a nylon of some kind – which starts out thick and then tapers away at the tip. You’d have at least nine feet of that, if not longer. Real experts can have a leader of up to 20 feet and might have one, two or three flies (known as a team of flies) on it, depending on the type of fishing they’re doing and the rules of the fishery. Fluorocarbon sinks fairly quickly, so if you want your line to get under the water, you’d use fluorocarbon. But if you’re dry-fly fishing you’d use monofilament, which sinks less quickly. To the other end of your leader you attach your fly or nymph. That’s it in its basic form and absolutely fine for now. There is a bewildering array of leader types, materials and configurations that we can’t even begin to contemplate here – in fact I’m feeling dizzy already.

You attach your leader to your fly line with a loop-to-loop connection. Fly lines these days almost invariably come with a factory attached loop, so you can tie a loop in the thick end of your leader; there’s a knot called the perfection loop, which I’d recommend. Then you tie your fly to the thin end of the leader. The last 18 inches or so are known as the tippet. Please use a grinner knot to begin with.

Starting out, you’d tend to just use one fly. Maybe a nymph (an artificial version of a subaquatic insect that lives its early life in the river, often replicating the moment it’s ascending) or a wet fly (an imitation of a subaquatic version of a fly or a small fish) or a dry fly. Those are the basics.

Nymph and wet-fly fishing are where your fly breaks the surface of the water and floats down to a nearby fish. Dry fly is fishing the adult fly on the surface. It’s very visual – you see the fish come up and take it.

The key is to present the fly precisely where the fish is rising, so that it goes for it almost as a reflex action. Some people say you should wait until you see a fish rising to a natural fly, imitate it and cast to it – these are the ultra purists that follow the works of FH Halford. Some fly fishers you meet will still swear by cane rods, as used in Halford’s day, but if you ask me, the fish don’t particularly seem to care what material your rod is made out of.

Lure fishing for trout is not to be ignored – in certain parts of the world, it’s the main method used. It usually involves fishing sub-surface – so you might want a sinking line for that, or a long leader with a weighted lure.

Sometimes at the end of the season, certainly on some lakes and reservoirs, a highly exciting way to fish for big trout is with a floating fry. That’s a very visual way of fishing as well.

The visual demands of fly fishing also mean you’ll need polarised sunglasses, so you can still see what’s going on in the water when the sun is dazzling off the river. Not only that, they are essential for safety.

Salmon fishing is its own world. You don’t just get entire books on the basics of salmon fly fishing, you get entire libraries, and none of them will be of any use to you until you’ve learned the basic techniques of fishing as a whole.

Even when you’ve reached the point where you’re fly fishing, prepare to be frequently bested by the fish. These are wild creatures who fight for their lives, and more often than not will end up slipping off your hook in a heartbeat. There’s an unteachable skill you need to be a good fly fisherman and that’s the mentality to lose a fish and get straight back in the game with as much confidence and spirit as you had before.

Fly fishing might seem complex, but like all the best hobbies, it is. There’s nothing immediate about its joys – they reveal themselves slowly, giving to you, almost imperceptibly, a reward for the obsessive hours you devote to it. You’ll never be the master of the art of fly fishing – but sometimes, on those rare special days, you’ll fly fish like a master. That’s what makes it so wonderful.

B: The tendency for Paul is to go fly fishing, so I tag along on occasion to go fly fishing with him. But when it comes to casting, I’ve still not cracked it. One in 15 of my casts is of any worth. But I look at Paul and the fishermen around me and it seems entirely effortless. He can land it on a sixpence.

P: It’s just practice. Look at me, I’ve been doing it years, but I’m still not the best. You need to practise and I don’t. In fact, on many days I think I’ve not learned very much. I often catch more trees behind me and bankside vegetation than I catch fish.

B: I think it’s like the riding-a-bike thing. I will at some point do a cast and then I will be able to cast – but I haven’t done that cast yet. One day, I hope I’ll do that cast, and everyone around will shout, ‘He’s got it! Bob’s got it!’ And I’m really looking forward to that day.

Bob: Are you going to the toilet in this one, Paul?

* Other rivers like the Derbyshire Wye and possibly Driffield Beck in Yorkshire claim to have been the mother and father of dry-fly fishing. I’m not getting involved, OK?!