CHAPTER 8

Stress: Making It Work for You

One day, in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful.

—Sigmund Freud

How much stress do you need to realize your potential?

(Hint: the answer is not zero.)

Janet, a nineteen-year-old liberal studies major, was constantly “stressed out.” She worried about the test next week, about not finishing her paper on time, about going out on a Friday night. At times she felt overwhelmed and couldn’t concentrate. Even the things she loved, like crossword puzzles or connecting with high school friends, felt like a demand. She had difficulty falling asleep, worrying about all the things she needed to do. But worst of all were the stomachaches. By the middle of her first semester, Janet woke up almost every morning with a gnawing pain in her belly. If she could just get rid of all the stress, Janet thought, the stomachaches would go away. We teach our students, however, that while stress may be harmful, it comes with some benefits, too. This came as something of an epiphany for Janet, who then made a conscious decision to turn her problem upside down: instead of striving for no stress, she would start using it to her advantage. Janet accepted that stress was going to be a part of her life, and she wanted to get the most out of it.

Type the word “stress” into a search engine, and you’ll get more than half a billion results. For college students, the topic is particularly relevant. In fact, 85 percent of college students report feeling stressed every day. The top stressors include:

schoolwork (77 percent)

schoolwork (77 percent)

grades (74 percent)

grades (74 percent)

finances (67 percent)

finances (67 percent)

family issues (54 percent)

family issues (54 percent)

relationship/dating (53 percent)

relationship/dating (53 percent)

extracurricular activities (51 percent)

extracurricular activities (51 percent)

There are plenty of things to be stressed about throughout college: finding the right classes, the right friends, and the right place to live. Although you might imagine that it gets easier, stressors appear in different forms with every passing semester. At some point during their undergrad experience, 60 percent of students feel so much stress that they can’t get their work done. Oh, and did we mention that higher levels of stress are correlated with higher rates of depression and anxiety?

No, we’re not trying to stress you out; good news is what we’re about to deliver here. Stress is not the problem. In fact, stress is essential for you to be your very best. It’s how you deal with it that may be tripping you up. This can be awfully tough to grasp, given that over the past forty years, the dominant message in the United States has been that you need to either reduce your stress or get rid of it altogether. In a 2014 survey titled “The Burden of Stress in America,” by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health, 70 percent of respondents reported that high levels of stress impacted their family life, health, social lives, and work, but almost the same percentage of people felt that at some time over the past month, stress had given them a boost as well. Sure, stress can come in supersize portions that are too much to handle for any healthy person, but stress reduction is only one side of the coin: the right amount of stress is enhancing.

Still skeptical? Take a moment and imagine an achievement from your past. It could be the time you ran a 5K/10K/20K, gave a stellar performance to a packed house, or aced a class that pushed you to your limits. Think about the work you put into it, and your emotions during the process. Write down a few sentences describing the achievement and what you did to accomplish it, if that helps it to hit home. Now consider how stress played a role along the way.

Kelly McGonigal, a lecturer at Stanford University, defines stress as any moment when “something you care about is at stake.” Whether your moment was a pressure-packed performance (on the field, onstage, or in the classroom), scoring an internship, or getting into college, your achievement was not only highly personal, but likely involved a great deal of stress. That stress was not there solely to make you miserable: it also pushed you to practice, study, and prepare harder, and when the time came, it was exactly that stress that allowed your mind and body to be focused and primed.

In this chapter, not only will we show you how to manage stress, we’ll show you how it can help you to be your very best. For many, including Janet, the first step toward managing her stress involved developing a different mindset toward it. Instead of attempting to reject it, Janet figured out that there are moments in life when we need to invite stress into our lives to push, propel, and motivate us. We will look at the mindsets that stress us out and the ones that help us perform better and score higher and keep us feeling more confident. We will show you ways to calm yourself down when you are feeling overwhelmed, but we will also show you how to seek out challenges and overcome them.

Okay, now you can relax… but not too much.

Getting to Know You

Before you take advantage of stress, it is helpful to understand your current stress mindset. Using the Stress Mindset Measure below, rate each question as follows:

0 = Strongly Disagree

1 = Disagree

2 = Neither Agree nor Disagree

3 = Agree

4 = Strongly Agree

1. The effects of stress are negative and should be avoided.

2. Experiencing stress facilitates my learning and growth.

3. Experiencing stress depletes my health and vitality.

4. Experiencing stress enhances my performance and productivity.

5. Experiencing stress inhibits my learning and growth.

6. Experiencing stress improves my health and vitality.

7. Experiencing stress debilitates my performance and productivity.

8. The effects of stress are positive and should be utilized.

Add up your answers to the odd-numbered questions and the even-numbered questions separately; how the two balance out will give you a snapshot of your mindset about stress. Is it more stress-is-harmful (odd-numbered questions) or stress-is-helpful (even-numbered questions)? Just as we have a mindset about growth and learning (as discussed in Chapter 4), we have a mindset about stress. The vast majority of Americans score high on stress-is-harmful and believe that stress will bring us down physically and mentally. A minority of people (hopefully a growing one by the end of this chapter) understand that stress can help them achieve peak performance, growth, and learning. The only thing your score on the above test indicates is your current mindset, not the mindset you could develop if you’re willing to create some change.

In 1908, Robert Mearns Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson designed an experiment that would begin to tackle the question, “How is stress related to learning?” The researchers tracked mice to see how stress would affect their ability to learn. Simple—yet painful, because how do you stress out mice? You shock them. The researchers set up two corridors to choose from—one painted white and the other black—and if a mouse went down the black corridor, ZAP! Yerkes and Dodson observed that given too mild a shock, the mice just shrugged it off and kept on keepin’ on—no biggie if they made the same mistake again. Too big a jolt, and the stress left them too frazzled to figure out what had just happened and how to make that not happen again. Those who learned most quickly—indeed, those mice that might need half as much time to learn which corridor to take—did it Goldilocks style: the size of their shock was juuuuust right.

You may not be a mouse, but research shows that you learn like one.

Not that we are suggesting self-electrocution (to do so would be highly unethical—fascinating, but highly unethical), but a just-right dose of stress can lead to your peak performance. Ed Ehlinger of the University of Minnesota studied almost 10,000 students and found that those who couldn’t manage their stress (32 percent of them) had a 0.5 drop in their GPA compared to their less-stressed-out peers. Imagine if getting your ZAP on in just the right way enabled you to learn math/English/anything-else-you-want in less time and learn it better.

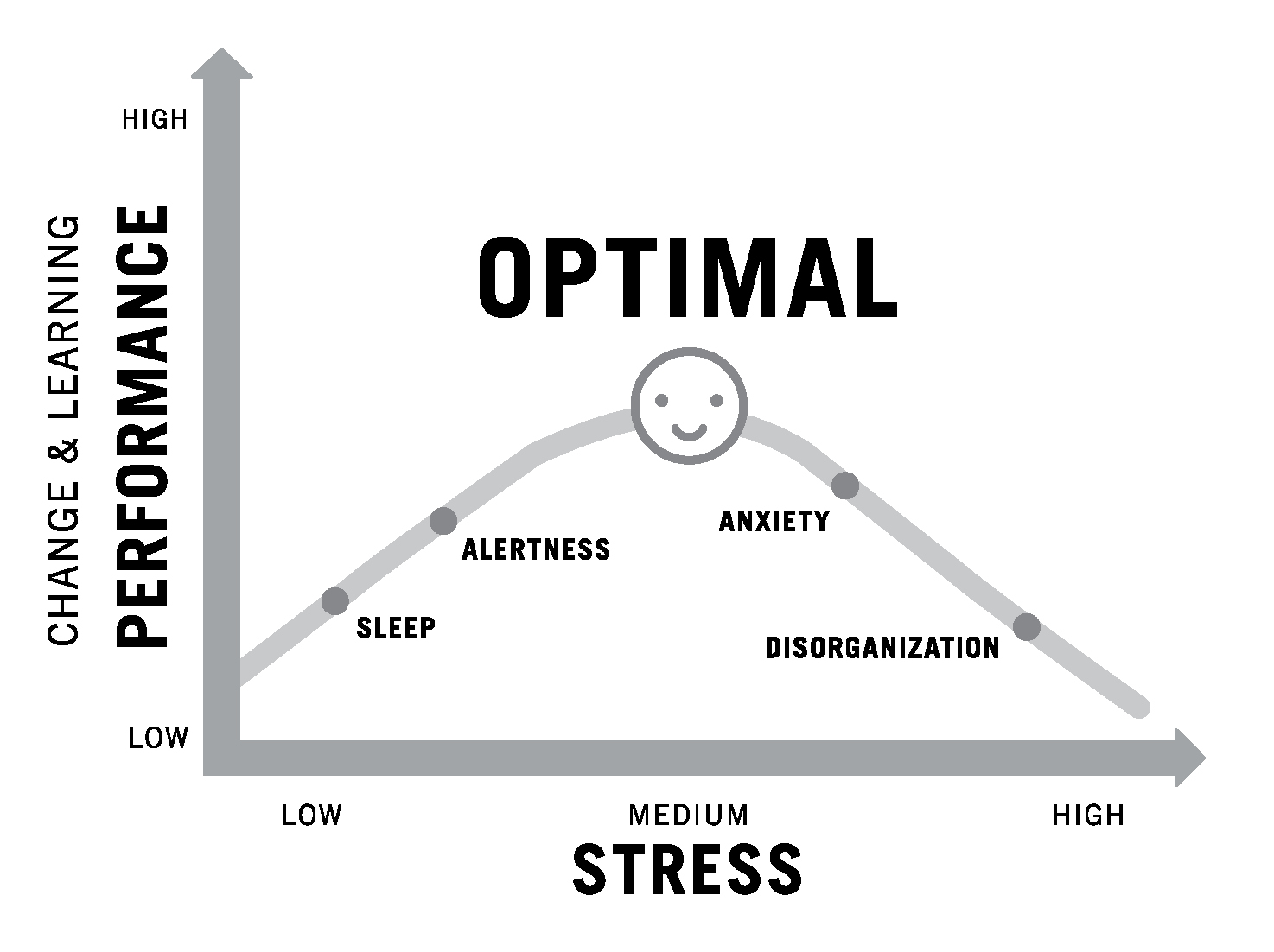

The Yerkes-Dodson experiments have risen to prominence as the Yerkes-Dodson Law (YDL) and have become the key to understanding the relationship between stress and our ability to change, learn, and perform. The YDL even comes with a handy-dandy YDL curve (see below) that helps us understand how to think about stress in relation to our performance in college and beyond.

One of the many beauties of the YDL curve is its simplicity: if you have too little stress (the left side of the curve) or too much stress (the right side), you miss out on opportunities to learn, change, perform, or basically do anything in college to help realize your potential. Simple? Yes. Pertinent? Very.

Kristen Joan Anderson, a psychologist at Northwestern University, did her version of the mouse-ZAP study on 100 college students, giving them escalating amounts of caffeine and having them answer questions like the ones in the verbal section of the Graduate Record Examinations (GREs). She found that many college students (and the rest of us), particularly with difficult tasks, perform their best at levels of stimulation that look a lot like the YDL curve (for those interested: about two cups seems to do it).

Interestingly, though, a feeling of control over stress profoundly impacts the effects of being stressed out. A 2015 study about stress and its impact on test scores found that, regardless of how “stressed out” the students really were, if they felt they could handle it, their grades didn’t suffer. For Janet, realizing that stress wasn’t going to be her lifelong enemy gave her a sense of control. The stress may have stuck around, in varying degrees, but her stomachaches disappeared. How you relate to, tolerate, and manage stress in any given situation dictates how well you can take advantage of it.

Putting Stress to the Test

Stanford psychologist Alia Crum must have been well aware that there are few things on earth that Americans fear more than public speaking when she designed a study to see how college students would react to stressful situations: they had to write and present a captivating ten-minute speech to a roomful of strangers in half an hour. BOOM—nightmare! The kicker (if you needed one): they were told that the speech would be videotaped and a group of experts would be available to provide feedback.

Before the task, their stress mindsets were evaluated. For the stress-is-harmful crew, the process proved to be too much. They took a crack at the talk but passed on the potential expert feedback. For the stress-is-helpful peeps? Bring it. They may have taken a deep breath before diving in, but they reacted in a way that took advantage of the promise of growth. Not only did they welcome the expert feedback, but they reported feeling less physically stressed out as well. As Crum points out, the stress-is-helpful mindset rises to meet “the demand, value, or goal” of a stressful situation. You are going to have a lot of different stressful situations in college—social, academic, and personal. Feedback is essential to growth and change in any situation; we talk about it in almost every chapter. The stress-is-enhancing mindset encourages you to seek out feedback and internalize it.

If you landed squarely in the stress-is-harmful mindset, fear not—there is hope for you yet! In another study, Crum chose 388 employees at a company “undergoing dramatic downsizing and restructuring.” (To put it in a college context, how would you feel if you heard that a randomly selected 33 percent of students at your school would be kicked out in the next few months? Yeah… ZAP.) Employees were divided into three groups, each assigned to watch one of three short videos on health, performance, or learning. One video focused on stress-is-harmful, one on stress-is-helpful, and the other was simply neutral. Over the course of the next week, those who watched the stress-is-harmful video felt no difference in their work, stress level, or health (likely because a vast majority of them already had the stress-is-harmful mentality). But the employees who watched the stress-is-helpful videos reported greater performance, had a better mood and felt less anxious, and noted that their physical health seemed to improve. Oh, and the videos? They were each only three minutes long. Three! If stressed-out businesspeople who were about to be fired could change their mindsets after watching a three-minute video, there’s a good chance that you can as well.

Fight-or-Get-the-Hell-Out-of-Here

It’s not just your mind that reacts to stress. Your physical reaction to pressure has been wired into you since the day you were born. Stop for a moment and think about the personal achievement you wrote about earlier, or the last really big test you took (the SAT tends to be a good go-to). Do any of these reactions come to mind?

Many people check every box. One study found that certain students preparing to take the SATs reported being so anxious and emotional that their minds would go blank, they became preoccupied worrying about whether others were doing better than they were, or couldn’t even concentrate on the test to begin with (all of which influenced their actual scores). What was happening to them? They are human beings. And like every single person since the dawn of mankind, their fight-or-flight instinct was being activated.

The fight-or-flight response is the human fire alarm system that has helped to keep us at the top of the food chain ever since our ancestors first roamed the planet. Lions, tigers, and bears show up at your cave and ka-WHAM, that sucker goes off. You start to breathe fast so you can get all the oxygen you need into your blood while your rapidly beating heart is pumping it to your muscles so that you can fight or… yes… get the hell out of there. Your body is primed to react, and your brain is primed to do whatever it needs to survive. As advanced as we are in so many ways, with our shiny cell phones and our fancy computers, our brains are still just like those of our cave-dwelling ancestors. To us, a threat is a threat; our rapid breathing and increased heart rate are the same whether we’re staring into the maw of a saber-toothed tiger or the blank page of a calculus midterm. We are primed to fight or book it, yet when it comes to exams, most of us try to ignore the panic and sit, practically motionless. This is part of the mismatch theory; what once kept us alive now feels like it is pulling us under. Trying to fight your own internal alarm actually narrows your focus and minimizes your odds of thinking clearly. So, what are you going to do? If only scurrying away scored us an A, we would all just invest in better running shoes—but alas, it doesn’t.

Trying to eliminate the fight-or-flight response would be like trying to eliminate our desire for sex. Millions of years of evolution ain’t being reversed anytime soon. What we can do is use our big human brains to learn how to manage it, and even make it work for us.

If the fight-or-flight response is the overactive kid in the house, constantly in motion and never able to sit still, its sibling is much easier to get along with and far more productive: the challenge response.

The Challenge Response

For most of us, the butterflies in our stomach that come with the big test/date/performance/event are not the pretty little creatures from childhood. They don’t land on your shoulder eliciting oohs and aahs as you chase them around the garden. No—these butterflies chase you. They are evil zombie butterflies who cost us about 10 percent of our final SAT score in the previous study compared to the students with less anxiety. But what if the butterflies signaled possibility rather than peril, promise rather than pitfall? What if these little suckers were actually trying to help us do better?

If you have ever prepared to take the field or the stage, or simply braced yourself for a tough conversation with a friend or roommate, you may recognize the challenge response. There is excitement and fear, joy and apprehension, and a nervousness mixed with eager anticipation. Much like the physiological responses that come with its fight-or-flight sibling, the challenge response makes your heart rate and blood pressure rise, but instead of feeling panic and becoming more reactive, you develop greater focus and concentration (sound useful for an exam?). The challenge response is quite a heady cocktail, and if you get it right, it can put you in the headspace to realize terrific breakthroughs. Best of all, you have the ability to influence which response you are going to have.

Opportunities to soar come in many guises, but very few are more pressure-packed than the tests that help determine our future. The GREs are to grad school what your SAT/ACT was to college. More than 500,000 people (69 percent of them twenty-five years old or younger) take the GRE in a year. In a study, Harvard psychologist Jeremy Jamieson, whose research focuses on stress and performance, gave two groups of undergrads a practice GRE. The first group was simply given the test and told to begin. The second group, however, was primed to experience the pressure differently—they were told to read the following paragraph before taking the practice exam:

People think that feeling anxious while taking a standardized test will make them do poorly on the test. However, recent research suggests that [physiological] arousal doesn’t hurt performance on these tests and can even help performance. People who feel anxious during a test might actually do better. This means that you shouldn’t feel concerned if you do feel anxious while taking today’s GRE test. If you find yourself feeling anxious, simply remind yourself that your arousal could be helping you do well.

The results? The second group scored an average of 55 points higher than their nonprimed classmates (738 to 683). But wait, it gets better. One month later, the same participants took the actual GRE, and the difference between their scores was even greater: 65 points (770 vs. 705).

Can It Really Be This Simple?

Simple, yes. Simplistic, no. The excitement (or dread… what Alan’s daughter calls being “nervouscited”) we may feel before an exam is the activation of our fight-or-flight response. It turns out that reading the passage shifted the students’ mindset so that they reframed stress, feeling less dread and more excitement. This, in turn, led to better performance on the exam. By simply reading and internalizing the paragraph, students swapped out their fight-or-flight response for that much kinder sibling: the challenge response.

Opportunities for Action

Exercise: Getting Excited to Stay Calm

If you are thinking that trying to keep calm is the way to go when you are stressed out, welcome to the vast majority. Harvard Business School professor Alison Wood Brooks found that 85 percent of people advise calm in the face of the storm. Yet not only does that not work, it actually has the opposite effect.

In a study using the classic combination of college students and karaoke, Brooks found that telling oneself to chillax is in fact a stress generator. She asked college students to perform karaoke in public, but before they went onstage, the subjects were divided into three groups and primed with one of three ideas: say nothing, say “I am excited,” or say “I am anxious.” Kind of like in an audition for The Voice, subjects were rated for pitch, volume, and rhythm by both computers and researchers (sadly, none of whom resembled Adam Levine or Shakira). The “I am anxious” group scored 53 percent, the lowest, apparently freaking themselves out and showing that certain self-statements can do more harm than good. If they were told to say nothing, their average score was 69 percent.

But the “I am excited” group scored an average of 81 percent. When you harness your challenge response, you can take advantage of your physiology and your mind, and you can kill it.

Feeling that you have control over stress doesn’t mean you stop “feeling” it. The “I am excited” group felt just as much anxiety as the “I am anxious” group and the group that said nothing, but they also felt more capable and were observed by their audience to be more confident. If you need to be intoxicated to perform karaoke, this experiment might not seem believable to you, but Brooks also studied people who had to give a speech or solve math problems. Same results: better performance and an even greater sense of competence.

We are not saying you will enjoy swimming with sharks if you just say “I am excited.” There is a time and place for you to actually fight or flee. But the next time something is at stake (other than your actual life) and you feel butterflies in your stomach and your heart pounding, remember that feeling scared and feeling excited often go hand in hand, and choosing one over the other (literally just saying out loud “I am excited”) can make all the difference.

Exercise: Take a Deep Breath, We’re Going to Vagus, Baby!

The right amount of stress can enhance performance, but there will also be moments when we move past that point and need to take control. Lucky for us, when the fight-or-flight response is going off and we want to tone it down, our bodies have a built-in off switch: the vagus nerve. Your vagus nerve winds through the body, touching almost every organ, and plays an important role in bringing your body to a state of equilibrium. It can signal your heart to slow down, lower your blood pressure, and put a halt to the fight-or-flight system. Thankfully, we have a way of turning on the vagus at will. To begin with, we need to introduce you to your diaphragm:

Stand up.

Stand up.

Pull your gut in as far as you can (like you’re six years old and trying to hide behind a tree).

Pull your gut in as far as you can (like you’re six years old and trying to hide behind a tree).

Feel under your rib cage. Dig your hands under there until it is vaguely uncomfortable.

Feel under your rib cage. Dig your hands under there until it is vaguely uncomfortable.

Now say “Hello, diaphragm.”

Now say “Hello, diaphragm.”

When you ask most people to take a deep breath, their chest expands. But when you take a genuinely deep breath, the belly gets pushed out instead. That is your diaphragm descending to make room for all the air.

This deep breathing is called belly breathing, because you have to push out and make that potbelly every time you take a deep breath in. Breathing deeply and rhythmically in this way activates the vagus nerve, signaling the body to turn off the fight-or-flight response. Belly breathing doesn’t come naturally, so it’s good to practice in order to train yourself to do it effectively. Belly breathing is easier to do when you are relaxed, so start your training in a calm setting (many people practice before bed).

Try the following steps:

Lie down on the floor and put something on your belly, like a book.

Lie down on the floor and put something on your belly, like a book.

Push your belly out and watch the book rise as you inhale and fall as you exhale slowly.

Push your belly out and watch the book rise as you inhale and fall as you exhale slowly.

The exhale should be as long as the inhale. Count to five as you inhale and count to five as you exhale.

The exhale should be as long as the inhale. Count to five as you inhale and count to five as you exhale.

Practice with ten full breaths twice daily.

Practice with ten full breaths twice daily.

Breathing patterns can be challenging to change when you are in even minor distress (e.g., your phone just fell into the toilet), but the more you practice, the more like a reflex it becomes, and being able to call on it in tense moments is like carrying around a fire extinguisher for your nerves. The next time your heart is racing out of control before you take the stage, run onto the field, or open the blue book, putting on the brakes can be just a breath away.

The Takeaway

The Big Idea

Stress definitely has some downsides, but it is also essential for developing optimal performance, change, and learning.

Be Sure to Remember

We each have an ideal level of stress that will produce our highest level of performance in any given situation. You can find your sweet spot—somewhere beyond blasé but short of overwhelmed—when stress hits.

We each have an ideal level of stress that will produce our highest level of performance in any given situation. You can find your sweet spot—somewhere beyond blasé but short of overwhelmed—when stress hits.

We all have the capacity to develop a stress-is-helpful belief system.

We all have the capacity to develop a stress-is-helpful belief system.

Fight-or-flight isn’t the only choice. A challenge response produces a similar physical response but replaces panic with focus and concentration.

Fight-or-flight isn’t the only choice. A challenge response produces a similar physical response but replaces panic with focus and concentration.

Making It Happen

When anxiety rears its ugly head, just saying “I’m excited” can steer you toward your challenge response and the better outcome it promises.

When anxiety rears its ugly head, just saying “I’m excited” can steer you toward your challenge response and the better outcome it promises.

The fight-or-flight system has an off switch, and it is found in deep, rhythmic belly breathing, but as with the fire drills we performed as kids, the key to using this skill during a crisis is found in routine practice.

The fight-or-flight system has an off switch, and it is found in deep, rhythmic belly breathing, but as with the fire drills we performed as kids, the key to using this skill during a crisis is found in routine practice.