In 1807, Robert Fulton’s Clermont became America's first dependable steamship and herald of a new age.

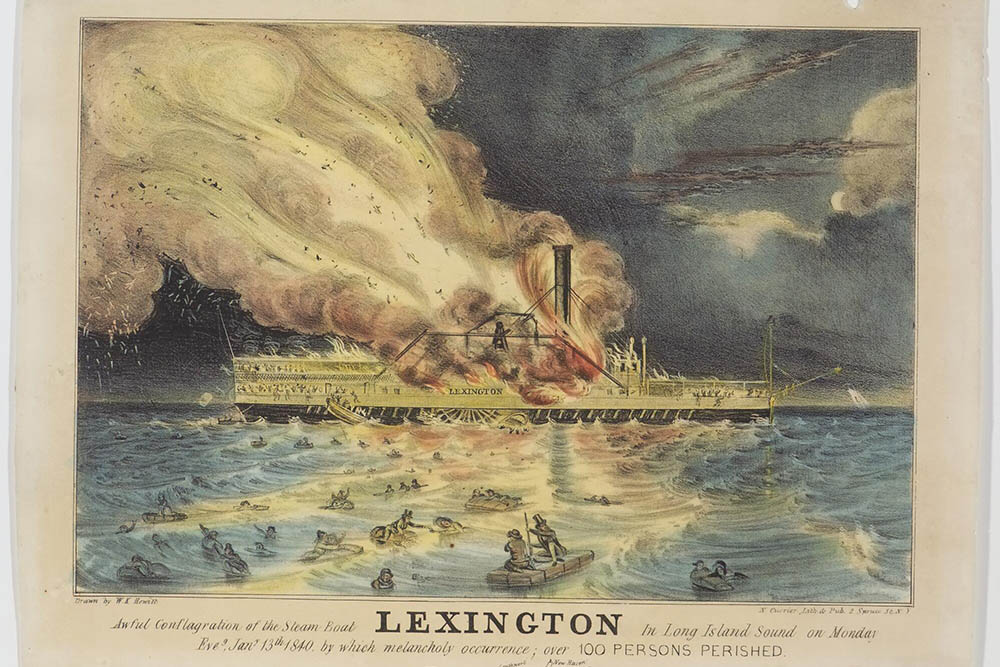

Cornelius Vanderbilt’s first command was a periauger. Within twenty-five years, he was commodore of a fleet of steamships on Long Island Sound. Pride of his fleet was the 488-ton Lexington, called “the fastest boat that ever sailed, speed twenty-three miles an hour when drove up.” In 1840, the five-year-old ship burned with a loss of 200 lives.

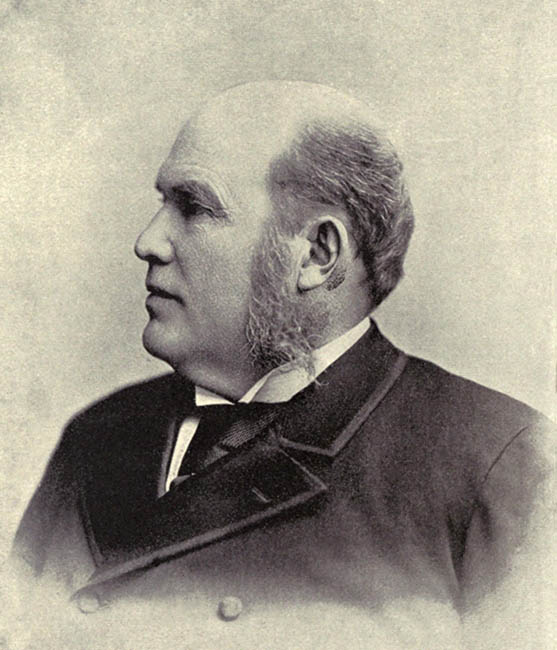

When the Commodore posed for Matthew Brady during the Civil War, his ships had brought him over $20 million.

By the 1860’s, Cyrus McCormick’s reaper was the small farmer’s chief laborer.

By the early 1880s, McCormick was turning out more than 100 farm machines a day. “An angry whirr, a dronish hum, a prolonged whistle, and a panting breath - such is the music of the place.” wrote one plant visitor.

“Don’t try to get rich too fast, and never feel rich,” advised Philip Danforth Armour. At thirty-three, he was a multimillionaire.

This statue of Cornelius Vanderbilt stands outside Grand Central Station in New York. Historian H. Roger Grant writes that while “Vanderbilt could be a rascal, combative, and cunning, he was much more a builder than a wrecker . . . being honorable, shrewd, and hard-working.”

New York’s Grand Central Station was erected on the site of Vanderbilt’s Grand Central Depot, which opened in 1871.

Vanderbilt’s Newport, Rhode Island, mansion, the Breakers, is now a National Historical Landmark.

Vanderbilt provided the initial gift to found Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

“Don’t try to get rich too fast, and never feel rich,” advised Philip Danforth Armour. At thirty-three, he was a multimillionaire. The gate to the great Union Stock Yards still stands.

Tobacco plants were first grown for profit by Virginia colonists in the early 1600s.

Duke University is named for James B. Duke’s father, Washington Duke. In 1884, James Duke perfected machine rolling of cigarettes and tripled cigarette sales in a year. “I always knew I was going to be rich,” he once said. “As early as I can remember, that idea has been on my mind.”

Once the headquarters of American Tobacco, this Durham, North Carolina, site is now part of a downtown urban renewal project.

Up a tortuous, 13,000-foot-high trail struggle some of the miners who hoped to cash in on the rich silver and lead deposits discovered at Leadville. Colorado, in 1877. Meyer Guggenheim reached the town in 1881, upset by the journey and afraid that he had invested $5,000 unwisely. “What a place.” he muttered to his partner. Charles Graham. “God help you if there is no million dollars in that mine.”

Some 40,000 people had flocked into Leadville by 1880 to find that like all mining camps it offered few beds and charged astronomical prices. This bird’s eye view by artist Augustus Koch of Leadville dates to 1879.

From an office on Main Street in Leadville, Guggenheim was sent the jubilant telegram: “Struck rich ore in A. Y. You have a bonanza.” Today, little remains in Leadville except a few abandoned cabins.

The Rockefeller Estate, Kykuit, is now an historic site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

John D. Rockefeller took up golf at sixty and still played regularly when he was ninety-four. He is pictured here with Harvey Firestone.

“Your fortune is rolling up like an avalanche! You must distribute it faster than it grows! If you do not, it will crush you.” How seriously John D. Rockefeller and his son, John D. Jr., took this admonition from a trusted advisor is shown by the extraordinary range of their philanthropies, estimated at well over $2.5 billion. Their gifts made possible the acquisition of 30,000 acres in Wyoming by the Grand Teton National Park.

This photograph of J. P. Morgan is from 1910.

This 1910 photograph shows New York City's Wall Street, looking east from the intersection with Broad Street. In foreground on the left is Federal Hall; on the right is J.P. Morgan's bank.

When Morgan traveled on rails, it was by private car, of course. And on the water he had a succession of private yachts. The last was 302 feet long and could cross the Atlantic. The cost of its fuel and crew was beyond computation. Someone once asked Morgan how much it cost to keep a yacht. He is supposed to have replied, “If you have to ask, you can’t afford it.”

Like other millionaires, Morgan had a number of residences. There was a mansion on New York’s Madison Avenue and another on the west shore of the Hudson; an Adirondack summer camp; and a summer cottage at fashionable Newport, Rhode Island. Since he spent three months of every year in Europe as he grew older, there was a townhouse in London and an English country estate named Dover House. And suites were always ready for him at hotels in London, Paris, and Rome. What marked these homes and set them apart from others was the magnificent works of art with which Morgan filled them. He bought paintings by the old masters, as well as statues, jewelry, armor, furniture, and precious old books and manuscripts. Eventually, he built a complete library, now standing at 36th Street and Madison Avenue, in New York City, to house the rare books that were the pride of his collections. Toward the end of his life, Morgan lent the Metropolitan Museum some of his most valuable paintings, and after his death, his son gave many of them to the Museum’s permanent collection. They are housed in the Pierpont Morgan wing, in honor of his father. Morgan’s collections, at the time of his death, were valued at about $50 million.

His personal mannerisms were those of an autocrat. He was hard to approach, and had few close friends. Although he could be very generous (he would, now and then, take parties of friends to jewelry or fur shops, and invite them to help themselves at his expense), people dreaded offending him. They felt uncomfortable in his presence. Above all, many were afraid of making some unfortunate remark about his red nose. There is a story that Mrs. Dwight Morrow, the wife of another banker, once invited Morgan to tea, promising to introduce him to her two little daughters, one of whom, Anne Morrow, later became a poet and the wife of the famous aviator, Charles Lindbergh. Mrs. Morrow was in mortal fear that the children would make some tactless remark, as children will, about Morgan’s remarkable nose. They were carefully coached not to stare at him, or to comment upon the great man’s appearance. Finally the day of his visit came. The girls were brought into the parlor, and a few moments of conversation followed. The hostess was on pins and needles until her daughters left. When they had gone, Mrs. Morrow, sighing with inward relief, turned and asked: “Do you, Mr. Morgan, take one or two lumps of sugar in your nose?”

Carnegie’s Keystone Bridge Company undertook to span the Mississippi in 1867. St. Louis’s famous Eads Bridge was opened in 1874; it had cost $10 million. Andrew Carnegie himself sold $4 million worth of its bonds to banker Junius Morgan. This photograph shows the bridge under construction in 1870. The steel arches were cantilevered from opposing piers high above the river. The bridge’s scale and design were unprecedented.

Brutal violence erupted in July 1892 when Frick’s hired Pinkerton guards attempted to land from barges and take over the Homestead works from a mob of strikers, 10,000 strong. This 1892 Harper’s Weekly cover show the surrender of Frick’s Pinkertons to strikers.

“How much have I given away?” Carnegie once asked his secretary. It was $324,657,399. “Wherever did I get all that money?” exclaimed the philanthropist. Among the institution Carnegie made possible: New York’s Carnegie Hall.

In this 1911 photograph, Andrew Carnegie stands in his Westchester County, New York, golf cottage.

Carnegie was laid to rest in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York. His headstone is frequently covered with coins.

Show here is Henry Ford’s first car, the 1896 Quadricycle, featuring a motor made with odd metal scraps and a plumber’s pipe. Many experiments later, the first “A,” capable of speeds up to thirty miles per hour, rolled out of Detroit in 1903. The “K” touring car appeared in 1906; barely 1,000 were made. Ford’s phenomenal success came with his “universal car.” the 1908 Model T.

The Quadricycle was invented in this garage in Dearborn, Michigan.

Careening racing cars, depicted in a 1909 Indianapolis Speedway poster, needed the services of a riding mechanic as well as a driver. Ford said of his 999 racer. “The roar alone . . . was enough to half kill a man.”

Ford regarded racing as a means of proving his cars to the public, and when a New York-to-Seattle race was announced in 1909, he began preparing two Model T’s for the 4,100-mile run. Only four other cars were entered, and when the six racers started on June 1, the two Fords rapidly moved ahead. They made Cleveland in four days, where an overheated radiator momentarily halted No. 2. After St. Louis, the rains came, and “for seven days,” wrote a driver, “the cars labored through Kansas gumbo and Colorado and Wyoming mud and sand.” In one flooded stream, a rattlesnake confronted No. 2’s mechanic, who hurriedly unlimbered his rifle. On June 23, No. 2 chugged into Seattle, seventeen hours ahead of its nearest rival. Here, Henry Ford poses with the grimy winner.

This photograph of the Ford assembly line was taken in 1914.

Ford’s earnest hut misguided efforts to end World War I were caricatured by the American press.

Photographed during a camping trip in 1921 are: Ford, Thomas Alva Edison, President Warren Harding, Harvey Firestone, and Methodist Bishop W. F. Anderson.

Advertisements for the 1931 Model A convertible hinted at wealth and social standing, in sharp contrast to the workhorse Model T, which “could go anywhere but in society.” Painted in “a choice of colors to match the season,” the Model A was as “smart as tomorrow.”

B-24 Liberator bombers stand ready to roll off the assembly line at Ford’s Willow Run plant during World War II. During the war years, Ford made no civilian automobiles.

Here, in 1946, Henry Ford poses with his wife, Clara.

The sprawling River Rouge plant near Detroit stood as a monument to Ford’s vision, successfully uniting varied production elements in a huge industrial complex.