Gardening for competition isn’t just another day at the plant. It can be serious business, especially when you’re growing cabbage. Whether you aim for perfectly round heads or a cabbage that weighs 100 pounds, you’ll need good timing, plenty of pest protection, and tips from some of the best in the business. If you grow a great head of this cruciferous veg, you just might win some real cabbage at the fair.

You can fry it, steam it, ferment it, slow-cook it, and even roast it. But when you stir cabbage into soup, you’re serving up a dish that’s one of the oldest recipes around. Some experts believe people have cultivated this good-for-you vegetable for four thousand years, others say closer to seven thousand. But what’s a few thousand years when describing this ancient edible? Nearly every country lays claim to a special recipe featuring some form of this cruciferous veg.

The cabbage family (Brassicaceae, also called the mustard family) is a big bunch, and cabbage is just one member of the clan. Cauliflower, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, and rutabaga all descended from the same wild plants. Wild cabbages grew on the coastlines of western Europe, where people gathered them before they started collecting seeds and planting their own.

The common cabbage that found its way into early fields and gardens is a valuable part of our vegetable history. Whether green or red, round or pointy, smooth or crinkly leaved, cabbage deserves some special recognition. Long favored as “the medicine of the poor,” cabbage’s healthful benefits are now backed by research. One of its components, the phytonutrient sulforaphane, may reduce the risk of some cancers. Cabbage is loaded with beta carotene, vitamins C and K, and fiber.

It’s also beautiful growing in fields and gardens. To me, cabbage’s large leaves are just as attractive as the fancy-schmancy foliage of expensive ornamental flowers.

It’s a shame more gardeners don’t grow cabbage. Some lack the garden space; others may have tried but were frustrated by a season that ended with small heads, no heads, or a crop devoured by hungry cabbage loopers.

You can grow perfect heads of this old-fashioned vegetable. All it takes is selecting suitable types, timing the planting, practicing good cultural methods, and staying ahead of insect pests and diseases.

At the 2013 annual Giant Cabbage Weigh-Off at the Alaska State Fair, 10-year-old Keevan Dinkel competed against adults in the open class and won. Keevan, a member of the family famous for growing giant cabbages, won $2,000 with his 92.3-pounder he named Bob.

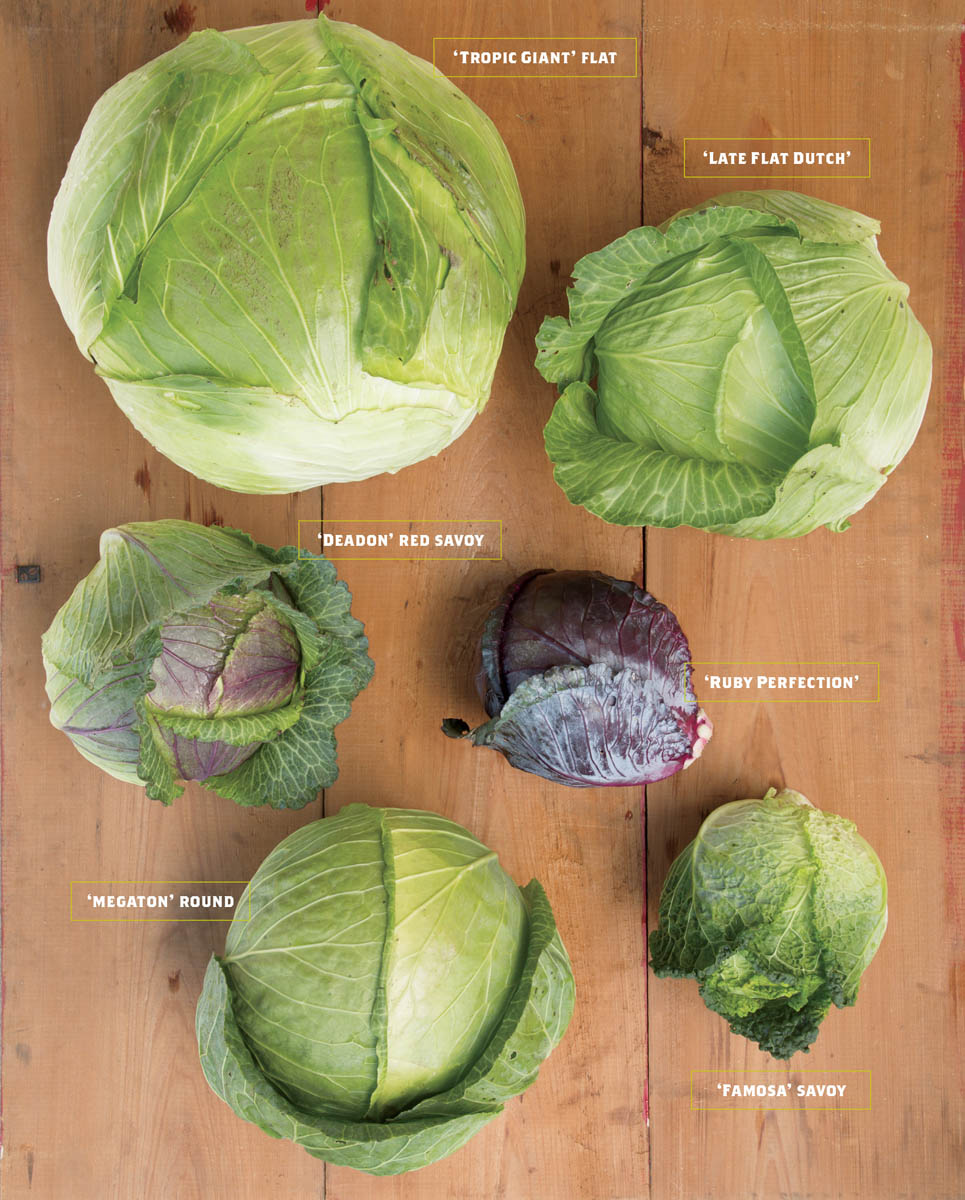

For success with cabbage contests, start by selecting varieties that fit the head shape (round, flat round, conical, globe), color (green, blue-green, reddish purple), and leaf texture (smooth or crinkled) of the contests you want to enter. The show book will list classes such as round green, flat green, pointed green, red, as well as other kinds including Chinese cabbage and Savoy. There may be special jumbo cabbage contests, too. While you’re checking the show book, make note of the schedule of the contest(s) you plan to enter.

Read seed and plant catalogs or search online for the cultivars that are known to grow well in your region. Note the number of days from transplanting until harvest, to help you plant at the right time for your contest.

For example, ‘Late Flat Dutch’ is a green cabbage that takes 90 to 100 days to mature. For a contest in late August, ‘Late Flat Dutch’ needs to be transplanted into the garden before the end of May. Because cabbage is a cool-season vegetable, and most vegetable contests are in late summer or early fall, the plants will be growing during the hottest part of summer. You may need to spread the planting dates over several weeks to give yourself more cabbage options. You may also need to harvest heads when they’re ready and hold them in a cool place instead of leaving them in the garden to overripen.

Ever heard of exploding cabbages? For commercial cabbage growers, this bursting phenomenon is as intense and forceful as it sounds. “The head itself is exploding to produce seed,” explains Chris Gunter, vegetable production specialist and associate professor of horticultural science at North Carolina State University.

Because cabbage is a biennial crop, the first year is spent growing as a rosette and developing a head, storing the sugars and starches produced by means of photosynthesis. If left in the ground to overwinter, in all but the coldest climates the outer leaves die back but the head and growing point inside are protected. During the second year, the plant’s new growth produces flowers that can develop cabbage seeds.

“In the botanical sense, a cabbage is a swollen terminal bud,” Chris explains. If you look into the center of a cabbage at the microscopic level, you’ll see its leaves and then its flowers. “If you dissect it, you’ll see microscopic leaves until it undergoes a physiological switch, and instead of leaves it produces flowers right at the top of the core of the cabbage.”

The goal is to encourage the formation of heads but not seeds, to keep cabbage from flipping that physiological switch. To switch from growing a leafy head to producing a flower, the plant needs a trigger. That trigger is pulled when the growing plant is subjected to a cold treatment. Commercial growers understand this happens not only when cabbages are left in the field over winter but also if the plant undergoes a period of cold weather in its first year. “You can see that happen if cabbage is grown from transplants, and they’re planted too early in spring and we get a cold snap. They won’t form a head; instead they begin to produce flowers,” Chris warns.

Once flower formation is triggered, “all the chemical energy is used by the plant to send up a flower stalk in the center, and it has to get out.” After a cold period, the flower stalk shoots up and tears through, either rupturing or literally exploding the head. The cabbage bursts open and the flower stalk explodes through. Chris says, “the pressure in the cabbage causes it to physiologically blow up. Instead of exploding into flower, it’s like a fist slowly punching its way straight through the cabbage leaves and ramming its way up through the leaves.” When this intense reaction, called bolting, shows up prematurely during a cabbage’s first season, it signals a cruel and untimely end to any chance for a blue-ribbon winner.

Cabbage plants that are exposed to cold weather early in the season are likely to flower instead of producing a head of cabbage.

Timing counts with cabbage. Plants can bolt if planted too soon and subjected to an extended cold spell. They’ll also split if too ripe. Careful timing can sometimes help you dodge insect invasions. Cabbage can handle light frost, so plan to set out transplants two to three weeks before the last expected frost date for your area.

Select a spot in the garden that gets sun at least 6 hours a day. Avoid planting where any brassica relatives grew the previous year to reduce insect and disease problems.

Be sure to test cabbage heads before harvesting them. If you squeeze one and it feels loose rather than solid, let it grow a bit more.

Testing soil pH really pays off when planting cabbage. The ideal soil pH range for cabbage is between 6.5 and 6.8 to grow high-quality heads and to help minimize some soil diseases. Add a well-balanced fertilizer before planting and amend the soil with plenty of organic matter. Till the garden bed deeply (about 15 inches) before planting.

Start seeds indoors or buy transplants. Acclimate plants gradually to outdoor conditions. Transplant when plants have five or six leaves and set transplants so their lowest leaves are at ground level. Give cabbage room to grow; allow 18 to 24 inches between plants. Water well after transplanting. As plants grow, keep soil moist; don’t let soil dry out.

Several weeks after planting, side-dress the cabbage patch with a rich compost. Keep up with fertilizing through the season, especially as heads begin to form.

Cabbage heads may look ready to harvest before the time is right. Test your cabbage by gently squeezing to make sure each head is solid. If the head feels loose, let it continue to grow and perform the squeezing test every few days. When ready, cut the head at the base of the plant or leave the contest’s required length of stem. Heads can keep for a week or more if wrapped in plastic and stored in the crisper section of the fridge.

Don Francois harvests cabbages for competition at the Iowa State Fair.

Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris, Pekinensis Group) is more closely related to other members of the cabbage (mustard) family than to ordinary cabbage. With tall columnar heads of green leaves and bright white midribs, it looks different from European cabbage. It also has a completely different history.

Chinese cabbage originated in the temperate areas of China, where it’s been cultivated for about 1,500 years.

There are many kinds of Chinese cabbages. For competition you’ll need either the heading (Napa) or the semi-heading (Michihili) kind. Napa types form tightly wrapped, barrel-shaped (“closed”) heads. Michihili varieties are the tall, columnar ones with looser upright leaves.

Chinese cabbage may be a challenge to grow and show for a late-summer contest. These plants grow best in cool weather and make a better fall vegetable than one that needs to mature in time for August fairs. Gardeners can overcome this challenge by planting heat-tolerant (bolt-resistant) cultivars, planning for some partial shade, and maintaining consistent soil moisture. These babies simply can’t be allowed to dry out.

The key to growing a winning entry of Chinese cabbage is the same as for any cabbage: steady growth. Plant in humus-rich soil, water consistently, and don’t skimp on fertilizer. As with any cabbage, you can minimize problems by not growing where related plants were grown the previous year.

Unlike the seeds of other cabbages, Chinese cabbage seeds can be sown outdoors as soon as the soil has warmed. Thin to 10 inches between plants when they’re about 4 inches tall. Or you can start indoors, but sow seeds in biodegradable peat pots that can be planted in the soil. Using peat pots instead of bare-root transplants helps reduce bolting. Chinese cabbage requires less room to grow than round cabbage, only 8 to 12 inches between plants.

Mulch to keep weeds out of the garden. Avoid any deep cultivation, which may harm roots.

At fair time, when heads are firm and fully developed, harvest right before the contest by carefully uprooting the plant or cutting it from the roots. Keep cabbage cool and moist all the way to the fair.

Even if you maintain a healthy garden, there may be problems that can turn potential prizewinners into losers. Because different areas of the country have different problems with insect pests and plant diseases, check with your county’s Cooperative Extension Service or local Master Gardeners to see what to watch for in your area. Here are the most common problems that can compromise a cabbage crop.

Cabbage root fly. It’s an ugly scenario when the adult fly lays its eggs on the soil near plant stems. The worms (maggots) hatch and burrow into the roots of the plant, causing leaves to wilt and turn reddish purple. Prevent flies from laying eggs by placing cabbage collars on the soil around plant stems.

Cabbage worms and cabbage loopers. Those little white butterflies fluttering around the garden aren’t so nice after all. They’re cabbageworm butterflies, which lay eggs that grow into cabbage caterpillars that feed on foliage and can make a mess of a plant in no time. Cover young plants with row cover to prevent butterflies from laying eggs, and keep plants covered as they mature. Continue to search for worms by looking under leaves for the fat caterpillars. Pick by hand and drown in soapy water or destroy. While you’re at it, pick off the cabbage loopers, too. Loopers look like green caterpillars with white racing stripes down their back and sides. They damage leaves and can ruin cabbages by eating their way through heads. Both cabbage worms and cabbage loopers can be controlled with the biological insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). The easiest way to apply Bt is by shaking the dust over plants.

Alternaria leaf spot is a fungal disease that may develop on young plants. Aptly named, this disfiguring disease shows up as dark brown to black sooty spots on leaves. To prevent, use treated seeds and plant resistant cultivars, rotate cabbage-family crops, and refrain from overwatering. Using straw mulch around plants can also help.

Blackleg and blackrot are two bacterial diseases, and their names describe what happens to the plant’s stem and taproot. They’re just as bad as they sound. To dodge these diseases, select cultivars that resist black rot, look for treated cabbage seeds, and purchase only healthy-looking transplants. And the two principles of disease prevention are first, allow space for air to circulate and second, avoid overwatering.

Club root is a fungal disease that stunts growth, turns leaves a purplish color, and causes plants to wilt when the weather gets hot. Keep this from establishing in your garden by practicing crop rotation: avoid planting cabbage, broccoli, or cauliflower in the same place every year.

Fusarium wilt (yellows) is a common fungal disease that shows up as yellowing of the lower leaves of the cabbage plant and stunted overall growth. Avoid Fusarium wilt by planting varieties described as YR or yellows-tolerant.

Damage from cabbage loopers

Some cabbage cultivars have special properties that help prevent common cabbage issues. To head off problems, like lopsided cabbages that split and are prone to disease, try these:

Round heads: Cabbages that produce reliably uniform heads include ‘King Cole’, ‘Savoy King’, ‘Cheers’, and ‘Megaton’.

Heat-resistant: Cabbages that grow well in hot weather include ‘Ruby Ball’, ‘January King’, and ‘Stonehead’ (also bursting tolerant); also ‘Jade Pagoda’ and ‘Tenderheart’ Chinese cabbages.

Split-resistant: Cabbages that resist splitting include ‘Early Jersey Wakefield’, ‘Late Flat Dutch’, ‘Ruby Ball’, and ‘Parel’.

Disease-resistant: Plants known to resist some cabbage diseases include ‘Caraflex’, ‘Super Red 80’, and ‘Blue Lagoon’.

Possible prizewinners may be hiding in this list. Some have been around a long time; ‘Early Jersey Wakefield’ and ‘Charleston Wakefield’ are heirloom varieties that grow cone-shaped heads. ‘Red Drumhead’ is another heirloom cabbage. ‘Gonzales’ is a mini-cabbage; its compact heads are perfect for smaller families and smaller gardens.

* Denotes an AAS award winner.

When spectators crowd the bleachers at the annual Giant Cabbage Weigh-Off during the Alaska State Fair, they’re hoping to watch a world record in the making. On the opposite side of the arena, the growers are hoping their season of hard work will pay off in a big way: in the size of their entries and in the thousands of dollars in prize money.

During the Weigh-Off — one of the fair’s premier events — the spotlight shines brightly on cabbages that look like they should be growing next to Jack’s proverbial giant beanstalk. These brassica behemoths have oversized leaves that can spread 6 feet wide with heads that can measure 2 feet across! The 2012 world record giant cabbage, grown by Scott Robb of Palmer, Alaska, weighed in at 138.25 pounds.

That record might not stand for long, especially when considering how big the champions have grown over time. At the fair’s first weigh-off in 1941, the winning giant cabbage weighed 23 pounds. Max Sherrod, a local farmer, took home the $25 grand prize as well as lasting fame because the fair’s special giant cabbage contest for junior gardeners is named for him.

The growers in the Matanuska-Susitna (Mat-Su) Valley certainly have the advantage over gardeners in the lower 48. The Mat-Su, located about 35 miles north of Anchorage, is known as an agricultural hotbed for cool-weather crops.

“The real reason for our giant veggies are our long summer days. We have nearly 20 hours of sunlight per day in June,” explains Stephen C. Brown. He’s the University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service agent for the Mat-Su and Copper River Districts, and a member of the board of directors for the Alaska State Fair.

Vegetables like cabbage may grow to XXL proportions because of the long days, but intense cultural manipulation has something to do with it, too. Stephen says cabbage competitors have spent years developing precise watering and fertilizing methods, as well as sophisticated systems for transporting their giants to the fair.

Growers work their horticultural hocus-pocus by developing their own hybrids, concocting fertilizer formulas, building windbreaks, and constructing shading devices to protect their cabbages from too much sun. Ask competitors for tips on growing giant cabbages and you might get some cheeky answers, like “fertilizing with Soylent Green” or giving credit to “the bicycle pump used to inflate them.”

Unlike the hard-core competitors who hold their secrets like a winning poker hand, Robert Thom shares his growing methods with others. Robert is an experienced competitor who’s entered his vegetables in fairs and exhibitions for more than 40 years. He’s collected many prizes over the years, but his biggest success was the 92-pound giant cabbage that captured second place one year. He’s also grown a daikon radish that weighed 11.5 pounds.

Giant vegetables from his farm are well traveled, too. One year he sent a giant cabbage to Hawaii’s annual 50th State Fair in Honolulu for a two-week exhibition that surely wowed the crowds. Hawaii hasn’t been the only stop for Robert’s giant produce. For several years he shipped big cabbages and other vegetables to Washington, D.C., where they were sliced and diced for U.S. Senate luncheons when Alaska Senator Ted Stevens was in office.

To grow giant heads of cabbage, gardeners need to start with the right seeds, Robert says. One of the main cultivars he’s grown is ‘OS Cross’. The OS stands for oversize, and this cultivar lives up to its name. It’s a heat-resistant hybrid that produces enormous heads of cabbage that can weigh 70 pounds or more. ‘OS Cross’ is such a reliable performer, All-America Selections named it a vegetable winner in 1951.

For giant cabbage, Robert starts seeds indoors in March and transplants when the garden soil warms sufficiently in May. Cabbage may be a cool-season vegetable, but it prefers to get growing in warm soil. Robert advises planting as many as a dozen, so there will be at least one or two good ones to take to the fair.

When the fair rolls around in August, it’s time to move the cabbages, which is no small feat. Cabbages, with all their leaves, need to be carefully harvested and quickly transported to the weigh-off because they lose weight with every passing minute. Competitors take extra care not to lose a single leaf, because each can add as much as 3 or 4 pounds to the total weight!

After arriving at the contest, volunteers wrangle cabbages on and off a special scale, all monitored by an official from the State of Alaska Division of Measurement Standards. As each weight is announced, the crowd reacts with appropriate oohs, aahs, and loud applause.

Depending on the number of entries at the weigh-off, and whether or not it was a good year for growing cabbage, there could be as much as half a ton of perfectly ripe cabbage ready for the kitchen. Now that’s a slew of slaw!

Cabbage entries must be weighed quickly, before they start to lose weight. Garret Streit’s 68.3-pound cabbage named Framagio won the 2014 Junior Champion award in the Alaska State Fair’s Giant Cabbage Weigh-Off.

The chance to be part of something bigger than themselves is just one reason third-graders across the contiguous United States plant big cabbages every year. Since the Bonnie Plants Cabbage Program started in 2002, millions of kids have had the chance to get their hands dirty competing for scholarship money and the experience of growing a colossal head of cabbage.

Each year Bonnie Plants provides free ‘OS Cross’ cabbage seedlings to students who sign up for the program. The kids compete to grow the best cabbage (based on size and appearance) in their school class. Winners at the class level are entered in a statewide drawing to select one winner of a $1,000 scholarship from each state.

Bonnie Plants has a long history with cabbage. Now one of the leading providers of vegetable and herb plants in North America, the company was a small family operation in 1918. As beginning farmers, Livingston and Bonnie Paulk started selling cabbage plants to help make ends meet during the winter. They planted their first cabbage crop with 2 pounds of seeds.

Now the company gives away more than one million cabbage plants each year to help grow a crop of new gardeners. Kids, and their parents, get the chance to learn and grow together. For some of the participants, this is the first time they’ve ever tried their hand at gardening. Teachers get in on the action, too. Bonnie Plants provides classroom lesson plans to help support what kids learn in the garden.

Even though only one junior gardener gets the top prize in each state, every kid is a winner. Each cabbage that’s planted and nurtured teaches valuable lessons about nature, responsibility, patience, and even disappointment. No doubt many kids will be inspired to continue gardening for a lifetime.

Check the show book for the number of heads you’ll need to exhibit. If the rules require more than one specimen, your contest cabbages should match each other. Some fairs may also specify a weight requirement (such as 4 to 6 pounds) and the number of wrapper leaves. Contest rules may spell out the length of stem or whether you should leave the roots on the cabbages. Rules may differ slightly for green, red, and Savoy cabbages.

Depending on the cultivar, an ideal head of Chinese cabbage is tall (12 to 16 inches) and wide (5 to 6 inches). Before harvesting, test Chinese cabbage for firmness by gently squeezing heads to make sure they’re solid. Don’t panic if some outer leaves are damaged, because those will be discarded anyway.