III

April 27, 1995

A mud-spattered Jeep Cherokee turns in off the Bearcreek highway and stops at the search party. A long-haired fellow climbs out, blinking uneasily. “What’s going on?” he asks.

Tim Eicher studies the guy intently: shoes, trousers, belt, shirt, jacket, hands, rings, height, weight, chin, mouth, nose, eyes, hair, hat. Steinmasel’s cap bears the legend BACA LAND AND CATTLE COMPANY. Eicher once served eight years as a game warden in New Mexico, and by God, come to think of it, he remembers seeing this nervous son of a gun somewhere around there.

“I remember you,” says Eicher, smiling, stepping forward with his hand out.

He remembers Eicher too. “Dusty Steinmasel,” he says, not meeting Eicher’s eyes, and points up the road beyond. “I live just up there.”

“Seen anything unusual lately?” asks Eicher. “Anybody coming through? Particularly Monday?” Eicher believes that Ten was killed on Monday, April twenty-fourth, because the next day was too stormy and snowy for your typical lazy-ass poacher to be out and about.

“Nothing unusual,” Steinmasel says, “nobody through here for at least a week. Just me and my neighbor,”

“Name of your neighbor?”

“Dave Oxford?”

Tim Eicher teaches interrogation techniques to up-and-coming officers, so he knows what to look for. “First,” he says, “you have to decide which of three types of person you are dealing with: visual, auditory, or feeling. Your visual type will look upward when you question him, and tend to say things like ‘I see.’ The auditory person will tend to look sideways when you question him, and say something like, ‘I hear you.’ The feeling type tends to keep his eyes downcast, and his remarks will refer to his feelings.” Eicher will not reveal his technique for determining whether the person is telling the truth or not, except to say that it has to do with involuntary eye movements—so involuntary that nobody can control them even if he knows the trick.

Eicher knows instantly that Steinmasel is lying.

A little later, Steinmasel’s neighbor, Dave Oxford, the only other person living in Scotch Coulee, drops by to see what all the hubbub is about.

“Sir,” Eicher asks Oxford, “have you seen anybody around or anything unusual?”

“Not really,” says Oxford. Oxford’s face is open, his eyes unevasive. “Oh—well, I did see Chad McKittrick on Monday, when Chad and Dusty went up the hill to get Chad’s truck unstuck.”

Ah.

Eicher walks up the road past Steinmasel’s cabin and on uphill for a couple of miles till he comes to a place where he can see that a vehicle had been stuck in the mud. What his gut and his training has already told him, evidence now confirms: Dave Oxford was telling the truth, and Dusty Steinmasel was not.

May 2

Despite his Ohio birth, his Michigan education, and his master’s degree in wildlife biology, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agent Tim Eicher is the very image of the Western lawman. From the tiptop of his big cowboy hat or, if indoors, his gleaming bald dome, to his steady blue-eyed stare and his luxuriant handlebar mustache and down to the sharp-tipped toes of his high-heeled boots, everything about Eicher proclaims that this is not a man to be messed with. His voice is low, and hard. His words are spare, and precise.

Eicher’s stiff-necked cop taciturnity, while real enough, is underlain by a quieter sense of antic humor, but what some wolf shooter is by God going to get is, in Eicher’s own words, “a man hunter. And I don’t fail. It may take time, but I get who I’m after. Always.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service offers a reward of one thousand dollars for information leading to the conviction of the killer of Wolf Number Ten. Defenders of Wildlife adds five thousand more. The National Audubon Society adds five thousand. An organization in California called Sea Shepherd, whose portfolio is marine mammals, has for some reason kicked in two thousand more.

The tips, the leads, the rumors, the absolutely certain accusations are piling up on Eicher’s desk in Cody, Wyoming. “It’s too much fucking money,” he complains. “When I get the guy, he’s going to want a jury trial, and in a district where the median income is twenty thousand dollars, that thirteen thousand is going to be a problem. Any jury here is going to know people will lie for thirteen thousand dollars.”

And why isn’t Eicher prowling the bars of Red Lodge incognito, meeting with secret informants, Sherlock-Holmesing the scene of the crime? Why is he sitting behind his desk?

“Something will come up. A hunter has to be patient.”

There is pressure on Tim Eicher. His bosses want this crime solved now. His phone rings not only with the fantasies of reward hunters and the lies of grudge bearers but also with ceaseless official and unofficial “encouragement” from the chain of federal command all the way up to Washington. And how does all that heat affect him?

Eicher leans back in his chair with his hands behind his head. Beneath the big mustache his lips part at the corner with a single soft smack, as though around an invisible toothpick. “I don’t give a shit about pressure.

“See, look,” he continues. “Ten’s radio collar was hidden in that culvert, right? The only person who would think to throw it in there would be a local. And I’m pretty sure I know who it is, and I’m pretty sure all I have to do is wait. There’s going to be one phone call,” he says.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent Tim Eicher is so cool he can ride past a grizzly bear without looking. His horse is even cooler. His name is Rock.

Of all the scores of calls Special Agent Time Eicher will have received, he will recognize this one. Late some remorse-ridden evening, that thirteen thousand bucks is going to draw Dusty Steinmasel to the telephone.

May 10

But Eicher is mistaken. Steinmasel does not call. Eicher is also kicking his own butt for not driving the Bearcreek highway right away. “I’d have seen birds over the carcass—ravens probably. Could have found it a lot sooner. Stupid mistake. And then a couple times when I was interrogating Dusty, when I should have been staring a hole in him, I was taking notes. Another mistake.” Eicher’s humility is the measure of his confidence.

A crack interrogator from the Denver office by the name of Leo “Grasshopper” Suazo flies in to join Tim Eicher for a little visit with Dusty Steinmasel.

Eicher adopts his coldest, flattest official tone. “Dusty, were you up the Scotch Coulee road on the evening of April twenty-third?” he demands.

“Nope.”

“Were you up the Scotch Coulee road on the morning of April twenty-fourth, helping Chad McKittrick get his blue Ford truck unstuck?”

“No, sir.”

“You know who killed that wolf, Dusty.”

“Well, all right, I was up there with Chad that morning,” Steinmasel admits with an exhalation of relief, followed by a quick tightening. “But I don’t know who killed the wolf. I sure didn’t.”

Tim Eicher and Grasshopper Suazo share a flicker of eye contact. With an imperceptible nod they agree to end the interview abruptly. The special agents bid good-bye to a very rattled Dusty Steinmasel.

Eicher is one hundred percent certain, this time, that Steinmasel is going to call.

May 13

Steinmasel leaves a message on Eicher’s answering machine, knowing that today, a Saturday, Eicher will not be in the office. “I forgot to tell you about the black Chevy,” he says. He wants to talk.

Eicher picks up his messages and senses immediately that there is no black Chevy. He gets in his unmarked but typically obvious government truck and drives north into Montana, to Belfry—where Chad McKittrick and Dusty Steinmasel bought a twelve-pack of beer the morning of the killing of Wolf Number Ten—then west up the desolate Bearcreek highway to meet Steinmasel.

The man hunter is calm. The hunted man is tied up in knots. Steinmasel tells the story truthfully, Eicher believes, and in meticulous detail—right up to the moment when he and McKittrick are standing over Number Ten’s body. At that point, he goes vague.

“After Chad shot the wolf, see, I went straight home,” says Steinmasel, stammering a little, “and then I was so upset I went out, uh, fishing. I never handled the body. Or that radio collar. I went back to look at the wolf again that afternoon and it was gone.”

“You went back,” says Eicher. “And what did you notice when you went back?

“There was new tire tracks.”

“What did you notice about the tire tracks, Dusty?”

“They were leading uphill toward the Meeteetsee Trail.”

Eicher knows that Steinmasel is lying about the afternoon, but he remains pretty sure that the details of the killing in the morning are true. He has enough information now for a search warrant on Chad McKittrick.

May 14

Dusty Steinmasel drives through Red Lodge and out to Chad McKittrick’s house to confess that he has ratted on him. McKittrick is quiet, forgiving, and drunk.

“I left myself out of it,” says Steinmasel, “just like we said in our gentlemen’s agreement, you remember? I didn’t say anything about helping you bring that carcass down the hill. I didn’t say anything about helping you skin it. I didn’t say anything about helping you bring it over here to the cabin. This is like we agreed, right, Chad?”

Dusty Steinmasel does not know that his false story concealing those facts is a federal felony.

McKittrick nods gloomily. “I’m sorry I got you involved,” he says. “I’ve been out here drunk for the last two weeks while you been running around paranoid.” He pauses for a long moment. “I’m glad it’s over.”

May 15

Tim Eicher and his supervisor, Commodore Mann (that is actually his name), appear in federal court in Billings, Montana. They present to Judge Jack Shanstrom an Application and Affidavit for Search Warrant. Eicher has laid out his case in six terse pages. “Based on the foregoing,” the application concludes,

the affiant has probable cause to believe that evidence of the illegal take, possession, and transportation of wolf #R10 will be found at the property of Chad McKittrick, located in Palisade Basin Ranches subdivision, Tract 21, near Red Lodge, Carbon County, Montana; said property being fruits, instrumentalities, and evidence of a violation of the Endangered Species Act and the Lacey Act, and consisting of a wolf hide, wolf hair and blood, a wolf skull and/or wolf parts, a 7 mm magnum rifle and 7 mm ammunition, a leather rifle scabbard, knife(s), axe(s), small metal plate(s) and two bolts, 1x6 and 2x6 boards, and orange baling twine, said property being fruits, instrumentalities, and evidence of violations of the Endangered Species Act, 16 USC 1538(a)(G), 50 CFR 17.84(i)(3) and (5) and the Lacey Act, 16 USC 3372(a)(1).

Warrant in hand, Eicher, Mann, and two other Fish and Wildlife Service special agents, Roy Brown and Ron Hanlon, make for Red Lodge, sixty miles away. There they meet sheriff McGill, Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks agent Kevin Nichols, and a sheriff ’s deputy who will sit in the car down the road for backup in case of trouble. In convoy, they head for McKittrick’s.

Thanks to Steinmasel’s visit the previous night, McKittrick is expecting them. He greets the intimidating contingent of lawmen and firepower with what seems almost like gratitude. He also looks jumpy in the extreme, and Eicher knows that nobody whose home is being minutely searched for criminal evidence is likely to feel especially peaceful, and he knows that McKittrick is not Carbon County’s most stable individual. While the others comb through the house, Eicher takes McKittrick out for a little walk-and-talk. Eicher does not take notes, and he is not carrying a tape recorder. He is, however, wearing a loaded pistol. They go down and check out the trout ponds. They hit a few golf balls. “I’m not denying I shot that animal, you know,” says McKittrick forlornly. “I feel bad about it. But I thought it was just a wild dog. Might kill a calf up there on that ranch.”

“They do that,” Eicher agrees amiably, not mentioning that McKittrick was trespassing on the ranch or that there were no cattle anywhere near.

“They will do that. Dogs. They will. Do you think I’m going to be famous?”

Eicher manages not to smile. “A lot of people don’t like the wolf reintroduction, Chad, but it’s still a federal crime to kill a wolf.”

“I thought it was a dog, sir.”

Eicher does not pursue the possibility of Chad McKittrick becoming famous for killing a dog.

“I wonder if NBC might want to make a TV movie about me,” McKittrick muses.

“I wish it could have been just him and me,” Eicher later recalls, “without all those troops, the sheriff, old Commodore and all. When you’re alone, confession can be like a secret between you. He was coming close.”

Inside McKittrick’s house, meanwhile, the officers find McKittrick’s Ruger M-77 rifle under the sofa, with elk ivory embedded in the stock and three live rounds of ammunition in the magazine. Eicher brings McKittrick in, and the suspect escorts his captors to the wolf ’s hide and severed head on a ladder in the half-built cabin out back.

Chad McKittrick is charged with killing Wolf Number Ten, possessing the remains, and transporting them.

Ten’s head, hide, and body will be frozen and then shipped to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service forensics laboratory at Ashland, Oregon. In the lab, forensic mammalogist Bonnie Yates will introduce the wolf ’s head into a colony of flesh-eating beetles, where it will stay until the skull is clean, white, and free of stink. She will then measure the cranium, jaw, and teeth. Her morphometry will confirm that it is the skull of a gray wolf.

Molecular biologist Stephen Fain will subject Ten’s flesh and hair to three sorts of DNA testing. A nucleotide sequence analysis of mitochondrial DNA isolated from the body recovered at Scotch Coulee will determine that it can have come only from a member of the species Canis lupus. A polymerase chain reaction will prove that the dead wolf was a male. A comparison restriction analysis will show that the hide and head and flesh all belonged to the same animal, and also that the dead male wolf’s DNA matches precisely that of the plug of flesh punched out of Number Ten’s ear at Hinton and kept frozen for precisely such a situation as this.

Veterinary pathologist Richard Stroud will remove the tiny Personal Identification Tag from Number Ten’s skin. The PIT tag, scanned by a laser-driven reader, will confirm the wolf ’s identity. An X-ray will find bullet fragments inside Ten’s thorax in a pattern typical of a high-powered rifle wound. Stroud will find that the shrapnel completely destroyed the wolf ’s liver and lungs. The greater part of the bullet continued on through the abdomen and out the other side. It has never been found.

May 30

Tim Eicher gets an anonymous call suggesting that Dusty Steinmasel may have more still to tell. Eicher goes to Steinmasel’s house and asks him, “What the hell’s going on, Dusty?”

Steinmasel has been writing—the whole story, including all of his own involvement. He doesn’t want the reward, he says, and he’s not looking for a deal. Just wants to clear his conscience.

“Sign it,” says Eicher.

Steinmasel does so, and Eicher takes it away.

June 12

Coming too fast around a curve in the mountains near Cooke City, Montana, Chad McKittrick—free on bail—careens off the Beartooth Highway and rolls his truck. The highway patrol takes a while coming from Red Lodge over the Beartooth Pass, which at almost eleven thousand feet is still snow-packed and icy even in mid-June. By the time they arrive, McKittrick has crawled out of the wreckage and gotten a lift to Cooke. He is now in one of the bars, drunk. Because it cannot be determined whether he got drunk in the bar or was already drunk when he had the accident, McKittrick will not be charged with driving under the influence.

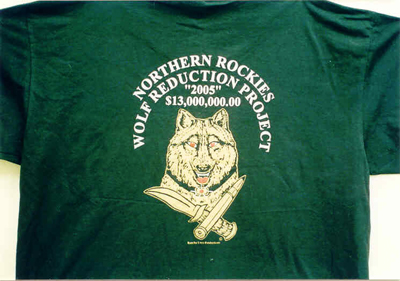

He is wearing a big knife, two pistols, and a T-shirt emblazoned with the words NORTHERN ROCKIES WOLF REDUCTION PROJECT—a witty gift from one of his drinking buddies at the Blue Ribbon Bar in Red Lodge. The cab of his pickup is full of beer bottles. The officers confiscate a total of nine guns.

After calling in his license number, the highway patrolmen learn that the man is facing federal charges for killing a wolf. They never report the accident, the T-shirt, the nine firearms, or any of McKittrick’s other numerous and blatantly apparent violations of the law.

July 4

Chad McKittrick rides his horse in the Independence Day parade down Broadway in Red Lodge wearing his NORTHERN ROCKIES WOLF REDUCTION PROJECT T-shirt and carrying a loaded pistol. After the parade, he rides the horse into a bar.

Later in the summer, McKittrick attends Quarter Beer Night—twenty-five cents per beer, that is—at the Snow Creek Saloon in Red Lodge. Near the Meeteetsee Trail bridge over Rock Creek, just south of town, about five miles from where he killed Wolf Number Ten, he passes a sheriff ’s patrol car so close that he brushes the deputy’s arm. The policemen pull him over and direct him to get into the back seat of the patrol car. He asks if he can take a pee first. They say okay. McKittrick plunges into the roadside brush and hightails it for glory.

The officers charge in after him. Owing to the Quarter Beers, the chase is short. They search his pickup and find marijuana. McKittrick is charged with possession of dangerous drugs, reckless driving, driving under the influence of alcohol, and resisting arrest. He is released on bond.

Chad McKittrick wore this t-shirt in the 1995 Fourth of July parade in Red Lodge. At his trial the following February, he testified that he did not know that the animal he had shot was a wolf.

As summer wanes, McKittrick starts yelling and waving his guns at people whom he considers to be driving too fast past his house. From time to time he is seen shooting randomly into the air, often wearing a black cowboy hat and no shirt. He threatens the life of a neighbor’s dog. Federal Express refuses to deliver to anyone in the neighborhood until somebody does something about the madman with the guns and the hat. McKittrick’s admirers in the bars—of whom there are more than a few—buy him drink after drink. He gives autographs all around, sometimes offering his signature without being asked.

U.S. Magistrate Richard Anderson rules that McKittrick has violated the principal terms of his release from federal custody, namely, that he not break any federal, state, or local law while awaiting trial. Anderson orders that McKittrick undergo a psychiatric evaluation and then be held in jail while the court studies the report.

October 23, 24, and 25, 1995

Twelve Montana citizens—modest, attentive, clearly unused to being watched so hard—sit in the jury box at the federal district court in Billings, hearing the testimony of Dusty Steinmasel, Tim Eicher, Chad McKittrick, and the government’s team of scientific experts. The defendant claims that he thought that Wolf Number Ten was a dog. Steinmasel testifies that McKittrick knew perfectly well that he was shooting a wolf. The jury’s deliberation lasts an hour and fifteen minutes.

Chad McKittrick is found guilty of killing a member of a threatened species, guilty of possessing its remains, and guilty of transporting it.

February 22, 1996

Judge Anderson sentences Chad McKittrick to six months’ imprisonment, recommending that the time be broken into three months in the Yellowstone County Detention Center and three months in a “pre-release center” in Billings called Alpha House, to be followed by one year of parole during which he must undergo random drug tests and warrantless searches of his house and truck. He is also fined ten thousand dollars, which, being indigent, he cannot pay but for which he will be held responsible should he ever be able to pay it.

“I know now it was a big mistake,” says McKittrick to the court. “All I can say, judge, is that I apologize and that it wasn’t my intent to kill a wolf. I thought it was a dog. Also I didn’t intend to hit it. I’m sorry for all the trouble.”

Still lying.