Chapter 14

Filling Out Your Sound with Chords

IN THIS CHAPTER

Building chords of all types

Building chords of all types

Translating chord symbols

Translating chord symbols

Inverting the notes of a chord

Inverting the notes of a chord

Playing songs with major, minor, and seventh chords

Playing songs with major, minor, and seventh chords

Aquick glance through this chapter may have you thinking, “Why do I need to know how to build chords?” Here’s one answer you may like: to impress your friends. Wait, here’s another: to play like a pro.

Playing melodies is nice and all, but harmony is the key to making your music sound fuller, better, cooler, and just downright great. Playing chords with your left hand is perhaps the easiest way to harmonize a melody. Playing chords with your right hand, too, is a great way to accompany a singer, guitarist, or other performer.

This chapter shows you step-by-step how to build chords and use them to accompany any melody.

Tapping into the Power of Chords

Three or more notes played at the same time form a chord. You can play them with one or both hands. Chords have but one simple goal in life: to provide harmony. (Chapter 12 tells you all about harmony.)

You may have encountered chords already in a number of situations, including the following:

- You see several musical notes stacked on top of each other in printed music.

- You notice strange symbols above the treble clef staff that make no sense when you read them, like F♯m7(-5), Csus4(add9).

- You hear a band or orchestra play.

- You honk a car horn.

Yes, the sound of a car horn is a chord, albeit a headache-inducing one. So are the sounds of a barbershop quartet, a church choir, and a sidewalk accordion player (monkey with tip jar is optional). Chances are, though, that you probably won’t use car horns or barbers to accompany your melodies — piano chords are much more practical.

Dissecting the Anatomy of a Triad

Chords begin very simply. Like melodies, chords are based on scales. (Chapter 10 gives you the skinny on scales.) To make a chord, you select any note and put other scale notes on top of it.

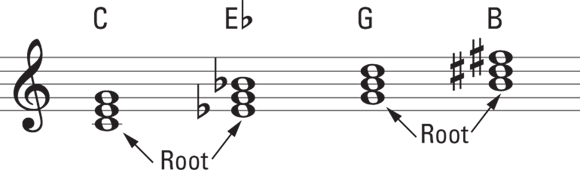

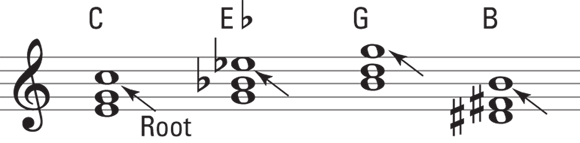

Generally, the lowest note of a chord is called the root. The root also gives the chord its name. For example, a chord with A as its root is an A chord. The notes you use on top of the root note give the chord its type, which I explain later in this chapter, starting with major and minor chords.

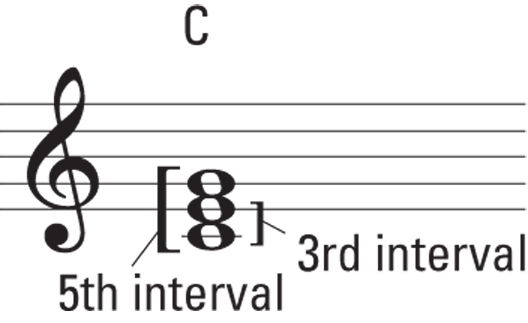

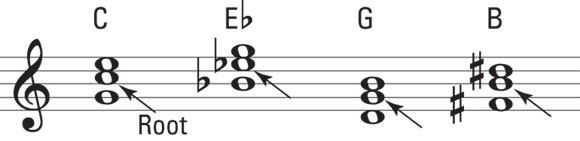

Most chords begin as triads, or three (tri) notes added (ad) together. Okay, that’s not the actual breakdown of the word, but it may help you remember what triad means. A triad consists of a root note and two other notes: the intervals of a third and a fifth. (Chapter 12 tells you about all the fun and games involved in intervals.) Figure 14-1 shows you a typical triad played on the white keys C-E-G. C is the root note, E is a third from C, and G is a fifth from C.

FIGURE 14-1: This C chord is a simple triad.

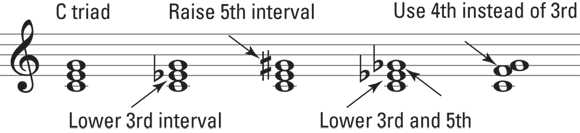

You build new chords by altering this C triad in any of the following ways:

- Raising or lowering notes of the triad by a half-step or whole-step

- Adding notes to the triad

- Both raising or lowering notes and adding notes

For example, Figure 14-2 shows you four different ways to change the C triad and make four new chords. Play each of these chords, the intervals of which are marked, to hear how they sound. (Chapter 12 explains these intervals and abbreviations.)

FIGURE 14-2: Making new chords from the C triad.

Starting Out with Major Chords

Major chords are perhaps the most frequently used, most familiar, and easiest triads to play. It’s a good bet that most folk and popular songs you know have one or two major chords.

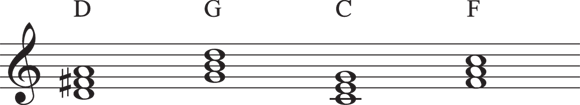

Major chords, such as the four in Figure 14-3, are so common that musicians treat them as almost the norm. These chords are named with just the name of the root, and musicians rarely say “major.” Instead, they just say the name of the chord and use a chord symbol written above the staff to indicate the name of the chord.

FIGURE 14-3: Major chords.

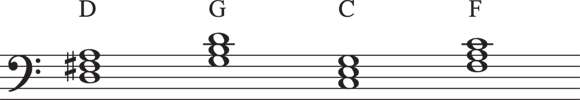

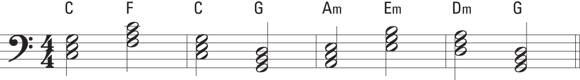

Use fingers 1, 3, and 5 to play major chords. If you’re playing left-hand chords (see Figure 14-4), start with LH 5 on the root note. For right-hand chords, play the root note with RH 1.

FIGURE 14-4: Major chords for lefty, too.

Branching Out with Minor Chords

Like the major chord, a minor chord is a triad comprised of a root note, a third, and a fifth. Written as a chord symbol, minor chords get the suffix m, or sometimes min. Songs in minor keys give you lots of opportunities to play minor chords.

You can make a minor chord two different ways:

- Play the root note, and add the third and fifth notes of the minor scale on top. For example, play A as the root note, and add the third note (C) and fifth note (E) of the A minor scale.

- Play a major chord and lower the middle note, or third interval, by one half-step. For example, a C major chord has the notes C-E-G. To play a C minor chord, lower the E to E-flat.

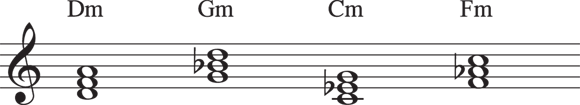

Figure 14-5 shows you several minor chords. Play them to hear how they sound, and then compare these chords to their major counterparts in Figure 14-3.

Just like playing major chords, use fingers 1, 3, and 5 for minor chords. For left-hand minor chords, play the root note with LH 5; for right-hand chords, play the root note with RH 1.

FIGURE 14-5: Minor, but not insignificant, chords.

Exploring Other Types of Chords

Major and minor chords are by far the most popular chords, but other types of chords get equal opportunity to shine in music. You form the following other chords by altering the notes of a major or minor chord or by adding notes to a major or minor chord.

Tweaking the fifth: Augmented and diminished chords

Major and minor chords differ from each other only in the third interval. The top note, the fifth interval, is the same for both types of chords, so by altering the fifth interval of a major or minor chord, you can create two new chord types, both triads.

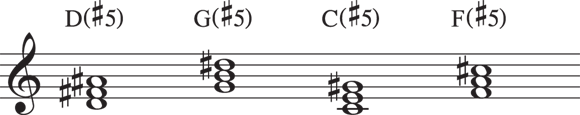

An augmented chord contains a root note, a major third (M3) interval, and an augmented fifth (aug5), which is a perfect fifth (P5) raised one half-step. Think of an augmented chord as simply a major chord with the top note raised one half-step. Figure 14-6 shows several augmented chords.

FIGURE 14-6: Augmented chords raise the fifth one half-step.

When writing the chord symbol, the suffixes for augmented chords include +, aug, and ♯5. I like to use ♯5 because it actually tells you what to do to change the chord — to raise the fifth.

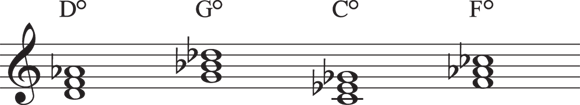

A diminished chord contains a root note, a minor third (m3) interval, and a diminished fifth (dim5), which is a perfect fifth (P5) interval lowered one half-step. Figure 14-7 gives you a selection of diminished chords.

FIGURE 14-7: Diminished chords lower the fifth one half-step.

Note the suffix used to signal a diminished chord in the chord symbol: dim. You may also see the suffix dim in the chord symbol, as in Fdim, or a small, raised circle following the chord symbol, as in Figure 14-7. (Table 14-1, later in this chapter, offers a helpful guide to chord symbols.)

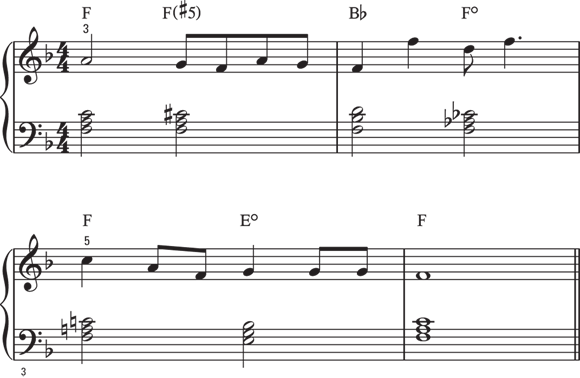

Figure 14-8 shows you an example of how you may encounter diminished and augmented chords in a song. The melody is the last phrase of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home.” Take these new chords for a spin and see how they subtly affect a song’s harmony.

FIGURE 14-8: Augmented and diminished chords in “Old Folks at Home.”

Waiting for resolution: Suspended chords

Another popular type of three-note chord, although it’s technically not a triad, is the suspended chord. The name means “hanging,” and the sound of a suspended chord always leaves you waiting for the next notes or chords.

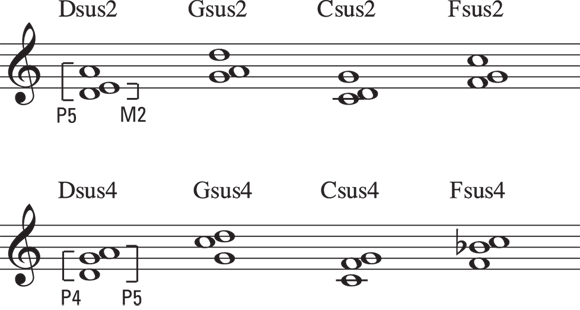

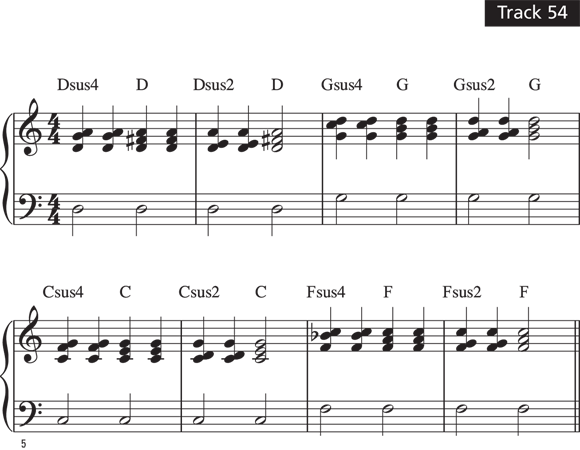

The two types of suspended chords are the suspended second and the suspended fourth. Because of their abbreviated suffixes, these chords are often referred to as the sus2 and sus4 chords; you see them written as Csus2 or Asus4, for example. Here’s how you create them:

- A sus2 chord is comprised of a root note, a major second (M2) interval, and a perfect fifth (P5) interval.

- A sus4 chord has a root note, a perfect fourth (P4), and a P5 interval.

Figure 14-9 shows you some of these suspenseful chords.

FIGURE 14-9: Suspended chords.

What’s being suspended, exactly? The third. A suspended chord leaves you hanging, and its resolution comes when the second or fourth resolves to the third. This doesn’t mean that all sus chords have to resolve to major or minor triads; actually, they sound pretty cool on their own.

Fingering suspended chords is pretty easy. For the right hand, use fingers 1, 2, and 5 for sus2 chords; use fingers 1, 4, and 5 for sus4 chords. For the left hand, use fingers 5, 4, and 1 for sus2 chords; use fingers 5, 2, and 1 for sus4 chords.

Play along with Figure 14-10, and listen to how the chord that follows each sus chord sounds resolved.

FIGURE 14-10: A little suspension tension.

Adding the Seventh

Adding a fourth note to a triad fills out the sound of a chord. Composers often use chords of four notes or more to create musical tension through an unresolved sound. Hearing this tension, the ear begs for resolution, usually found in a major or minor chord that follows. At the very least, these tension-filled chords make you want to keep listening, and to a composer, that’s always a good thing.

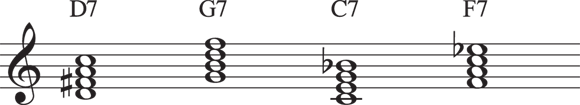

The most common four-note chord is the seventh chord, which you build by adding a minor seventh above the root note of a triad. Played on the piano by itself, the minor seventh may not sound very pretty, but it sounds good when you add it to a triad. In fact, the result is one of the most common sounds in Western music. You’ll be amazed at how many great songs use seventh chords.

The basic seventh chord uses the minor seventh interval, which is the seventh note up the scale from the chord’s root but lowered one half-step. For example, if the root note is C, the seventh note up the scale is B. Lower this note by one half-step and you get a minor seventh above the C, B-flat.

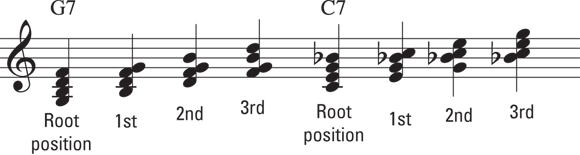

The four-note chords shown in Figure 14-11 are all seventh chords. The chord symbol is simple and easy: It’s an Arabic numeral 7 placed after the triad symbol.

FIGURE 14-11: There’s nothing plain about these seventh chords.

The suffixes used by seventh chords are placed after the triad type’s suffix. For example, if you add a minor seventh to a minor triad, the suffix 7 comes after m, giving you m7 as the full chord type suffix for a minor seventh chord.

To play seventh chords, use fingers 1, 2, 3, and 5 in the right hand. You may want to use RH 4 instead of RH 3 for certain chords, when the chord shape feels natural with RH 4. With the left hand, play the root note with LH 5 and the top note with LH 1.

Reading Chord Symbols

When you encounter sheet music or songbooks containing just melodies and lyrics, you usually also get the little letters and symbols called chord symbols above the staff, as shown in many of the figures in this chapter. Knowing how to build chords from chord symbols is an extremely valuable skill. It equips you to make a G diminished chord, for example, when you see the chord symbol for one, Gdim.

- Root: The capital letter on the left tells you the chord root. As with scales, the root note gives the chord its name. For example, the root of a C chord is the note C.

- Type: Any letter and/or number suffix following the chord root tells you the chord type. Earlier in this chapter, I explain suffixes like m for minor and 7 for seventh chords. Major chords have no suffix, just the letter name, so a capital letter by itself tells you to play a major triad.

Music written with chord symbols is your set of blueprints for what type of chord to construct to accompany the melody. For any chord types you may come across in your musical life (and there are plenty of chords out there), you build the chord by placing the appropriate intervals or scale notes on top of the root note. For example, C6 means play a C major chord and add the major sixth (A); Cm6 means to play a C minor chord and add the major sixth.

Figure 14-12 shows the tune “Bingo” with its chord symbols written above it in the treble staff. The notes in the bass staff match the chord symbols and show you one way to play a simple chord accompaniment in your left hand.

FIGURE 14-12: Transforming chord symbols into notes on the staff.

You may encounter many curious-looking chord symbols in the songs you play. Table 14-1 lists the most common and user-friendly chord symbols, the variety of ways they may be written, the chord type, and a recipe for building the chord. Note: The examples in the table all use C as the root, but you can apply these recipes to any root note and make the chord you want.

TABLE 14-1 Recipes for Constructing Chords

Chord Symbol |

Chord Type |

Scale Note Recipe |

C |

Major |

1-3-5 |

Cmin; Cm |

Minor |

1- ♭ 3-5 |

Caug; C( ♯ 5); C+ |

Augmented |

1-3- ♯ 5 |

Cdim; Cdim.; ° |

Diminished |

1- ♭ 3- ♭ 5 |

Csus2 |

Suspended second |

1-2-5 |

C(add2); C(add9) |

Add second (or ninth) |

1-2-3-5 |

Cm(add2); Cm(add9) |

Minor, add second (or ninth) |

1-2- ♭ 3-5 |

Csus4 |

Suspended fourth |

1-4-5 |

C( ♭ 5) |

Flat fifth |

1-3- ♭ 5 |

C6 |

Sixth |

1-3-5-6 |

Cm6 |

Minor sixth |

1- ♭ 3-5-6 |

C7 |

Seventh |

1-3-5- ♭ 7 |

Cmaj7; CM7; C△7 |

Major seventh |

1-3-5-7 |

Cmin7; Cm7; C-7 |

Minor seventh |

1- ♭ 3-5- ♭ 7 |

Cdim.7; Cdim7 |

Diminished seventh |

1- ♭3- ♭♭ 7 |

C7sus4 |

Seventh, suspended fourth |

1-4-5- ♭ 7 |

Cm(maj7) |

Minor, major seventh |

1- ♭ 3-5-7 |

C7 ♯ 5; C7+ |

Seventh, sharp fifth |

1-3- ♯ 5- ♭7 |

C7 ♭ 5; C7-5 |

Seventh, flat fifth |

1-3- ♭ 5- ♭ 7 |

Cm7 ♭ 5; CØ7 |

Minor seventh, flat fifth |

1- ♭ 3- ♭ 5- ♭ 7 |

Cmaj7 ♭ 5 |

Major seventh, flat fifth |

1-3- ♭ 5-7 |

Figure 14-13 shows you exactly how to make a chord from a recipe in Table 14-1. The recipe of 1-3-♯5-7 is applied to three different root notes — C, F, G — to illustrate how chord-building works with different root notes and thus different scale notes. By the way, the resulting chord is called a Cmaj7♯5 because you add the seventh interval and sharp (raise one half-step) the fifth.

FIGURE 14-13: Building a chord from a chord symbol.

Playing with Chord Inversions

When you play a chord with the root on the bottom, or the lowest note, you’re playing the chord in root position. But you don’t always have to put the root on the bottom of the chord. Thanks to certain civil liberties and inalienable rights, you’re free to rearrange the notes of a chord any way you like without damaging the chord’s type. This rearrangement, or repositioning, of the notes in a chord is called a chord inversion.

How many inversions are possible for a chord? It depends on the number of notes the chord contains. In addition to the root position, you can make two inversions of a triad. If you have a four-note chord, you can make three inversions.

Putting inversions to work

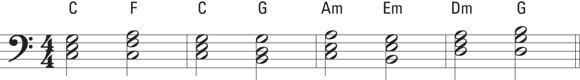

Why would you want to rearrange a perfectly good chord? Play the left-hand chords in Figure 14-14, and notice how much your left hand moves around the keyboard.

FIGURE 14-14: Traveling back to your roots.

Constantly jumping around to all the chords in Figure 14-14 can become tiring, and it doesn’t sound very smooth, either. The solution is to use inversions. Play Figure 14-15, and notice the improvement. You play the same chords as in the previous exercise, but you don’t move your left hand up and down the keyboard.

FIGURE 14-15: There’s less effort in these chord inversions.

- Drawing attention to the top note: Most of the time, you hear the top note of a chord above the rest of the notes. You may want to bring out the melody by playing chords with melody notes on top.

- Chord boredom: Root position chords get boring if used too frequently, and inversions add some variety to a song.

- Smoother chord progressions: Each song has its own progression of chords. Inversions help you find a combination of chord positions that sound good to your ears.

Flipping the notes fantastic

Any triad has three possible chord positions: root position, first inversion, and second inversion. Root position is just like it sounds: The root goes on the bottom, as shown in Figure 14-16.

FIGURE 14-16: Root position grabs chords by the roots.

For the first inversion, you move the root from the bottom to the top, one octave higher than its original position. The chord’s third moves to the bottom. See Figure 14-17 for examples of first inversions.

FIGURE 14-17: First inversions put the thirds on the bottom and the roots on top.

The second inversion puts the third on top (or one octave higher than its original position). The fifth of the chord is on the bottom, and the root is the middle note of the chord. Figure 14-18 shows you some second-inversion chords.

FIGURE 14-18: Second inversions put the roots in the middle.

FIGURE 14-19: Seventh chords and their third inversions.

Experiment with these inversions on various types of chords so that when you’re playing from a fake book, you know which inversions of which chords work best for you. (Chapter 19 explains what fake books are.)

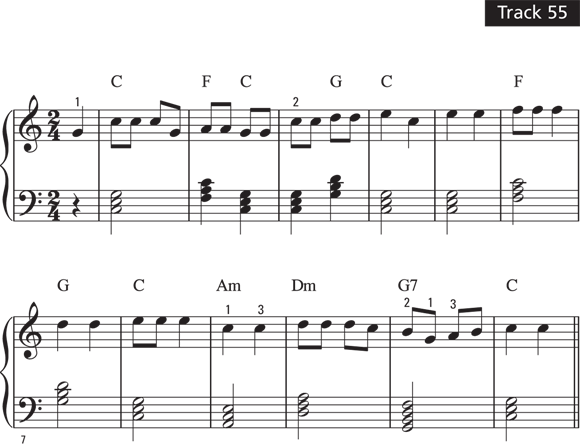

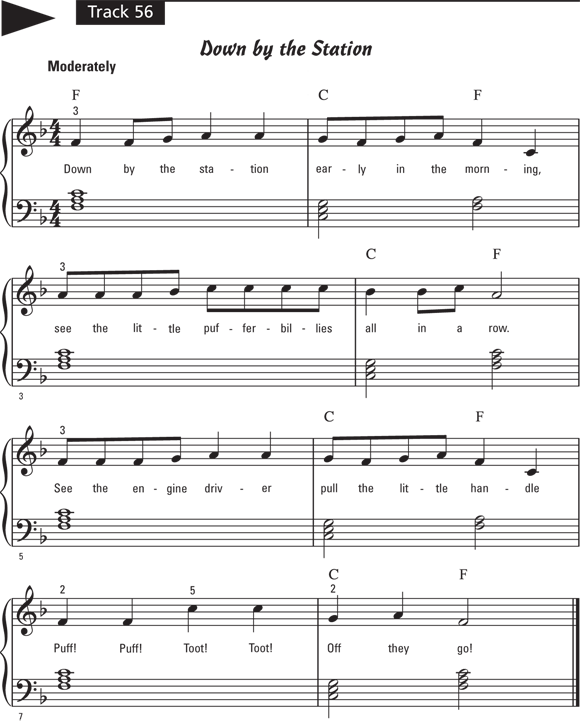

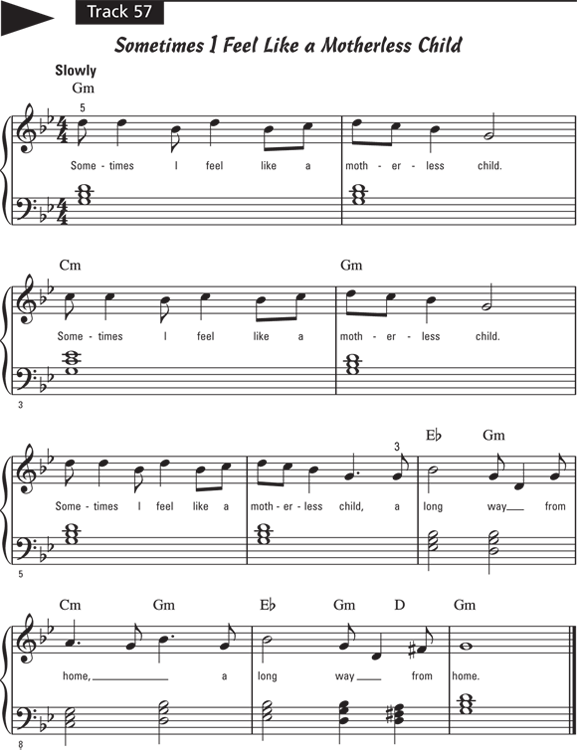

Playing Songs with Chords

The songs in this section give you some experience adding chords to familiar songs. As you play the selections, try to identify the chords in the left hand and match them to the chord symbols written above the treble staff. First locate the chord root, then the third, fifth, and seventh (if included). If you notice any chord inversions, see how they affect the chord progression and melody.

-

“Down by the Station”: This song lets you play a few chords of the major type with your left hand.

If you play along with Audio Track 56 at

If you play along with Audio Track 56 at www.dummies.com/go/piano, you’ll hear both the chords and the melody. You can play the left-hand part by itself until you get comfortable with the shape of the chords in your hand. Then add the melody. - “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”: This spiritual gives you practice playing minor chords and a couple of major chords, too. It also has some chord inversions, so if you need to brush up on inversions, review the previous section.

- “Lullaby”: You find all kinds of seventh chords in all kinds of music, from classical to pop. Johannes Brahms’s famous “Lullaby” is an example of how seventh chords can create a little harmonic variety. Just don’t let it lull you to sleep.

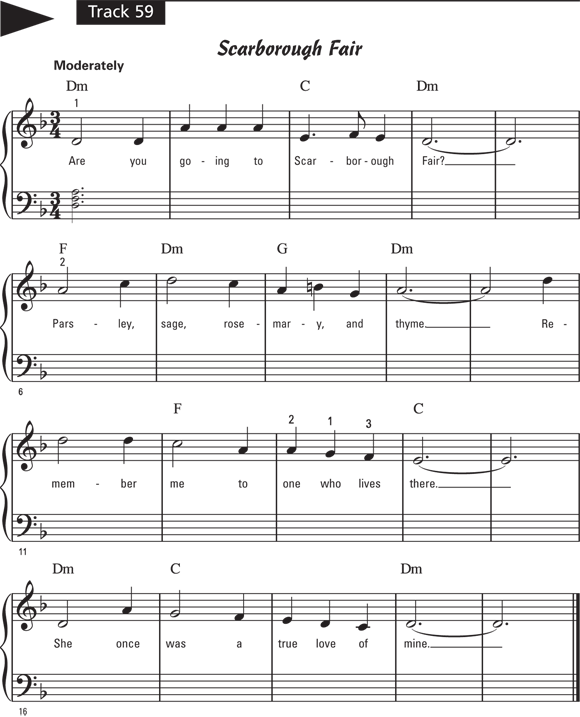

- “Scarborough Fair”: This song is in a minor key — D minor. (To find out more about major and minor keys, see Chapter 13.) It gives you a chance to play chords in your left hand based on the chord symbols. If you have trouble building the chords, review the sections on major and minor chords earlier in this chapter. The bass clef staff is left open for you to write in the notes of each chord.

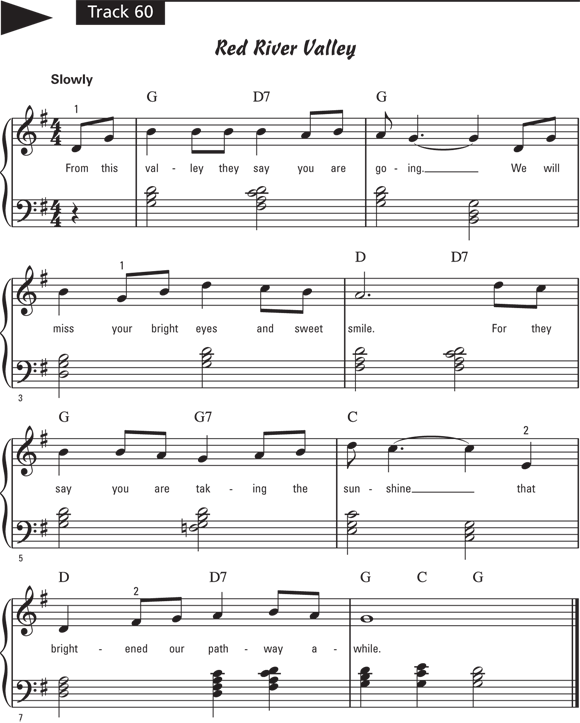

- “Red River Valley”: This song calls for lots of chord inversions. It has triads and seventh chords along with first, second, and third inversions and a few garden-variety root position chords. Notice how the left hand plays half-note chords, with a few quarter-note changes in important places. You have the opportunity to change the inversion of a chord when the chord symbols are infrequent, like in this folk song.

You make major chords with the notes and intervals of a major scale. (

You make major chords with the notes and intervals of a major scale. ( To play a song with left-hand major chords right now, skip to the section “

To play a song with left-hand major chords right now, skip to the section “ Don’t be fooled by the name “minor.” These chords are no smaller or any less important than major chords. They simply incorporate minor thirds, rather than major thirds. Minor chords are to major chords as shadow is to light, the yang to the yin.

Don’t be fooled by the name “minor.” These chords are no smaller or any less important than major chords. They simply incorporate minor thirds, rather than major thirds. Minor chords are to major chords as shadow is to light, the yang to the yin. You may find it easiest to use fingers 1, 2, and 4 for augmented and diminished chords played with the right hand. For the left hand, try 5, 3, and 2.

You may find it easiest to use fingers 1, 2, and 4 for augmented and diminished chords played with the right hand. For the left hand, try 5, 3, and 2.