As we explore whole-brain marketing and how we make decisions, it helps to have a sense of what marketing experts have been pitching over the past decade. At least how they have connected creative ideas with improving the bottom line.

These are the same thoughts I shared with Russell when he asked if our billboard ideas would work. As marketers, we experience enough campaigns over the years and we start to understand how messages and audiences are connected. We get a sense for certain messages that will resonate, and we recognize those that won’t. This is the marketing gut.

After we go through the basic pitch, we’ll look at it again with a neuroscience perspective. That way, we aren’t just basing it on experience, but showing how science explains it all.

Here’s the basic pitch that I’ve experienced from a number of agencies, marketing departments, and creative boutiques.

We’ll go through this quickly so you get the backstory on how this has been presented. It starts by describing all the millions of messages that bombard consumers every day. The sheer number of media choices given to consumers is enormous, with endless photos, ads, videos, texts, emails, billboards, and apps. People’s brains should be overloaded before they finish breakfast. Except they’ve learned to block most of them.

And the only way to break through all that clutter and get noticed is with an emotional idea. It can be expressed in a few words, in an image, in a story—as long as it is told in a way that pulls on an emotion with the audience. That emotion can be comedy, inspiration, sorrow, or appreciation. The level of stand-out power depends on the amount of emotion. Something that is really emotionally charged will have more impact than something with a flutter of emotion.

The reason you need an emotional idea is because it causes more participation from the audience. Emotions draw people into the conversation. They react to the image or story. When they feel an emotion, they feel more connected. When we create ideas that require a little bit of participation from the audience, this creates an experience. Noticing an ad is one thing. Experiencing it is so much better.

We call this experience with your brand being “sticky.” Which means the idea lasts longer in their mind. When your audience participates in the experience, their engagement level goes up. The more they are engaged, the stickier the experience becomes. Creative ideas create these moments of deeper engagement.

This sticky factor is important to the success of a piece of communication because it gives it a greater chance of being liked. When consumers have a positive experience and feel engaged, they create positive memories of the experience. These positive experiences over time create brand preference, which is another way of saying your customers like your brand.

Finally, people who have positive experiences with a brand become more loyal and are willing to pay more for that experience again. Brands are built on positive feelings over many experiences. And if you can consistently keep the positive experiences coming, your customers will remain loyal to your brand.

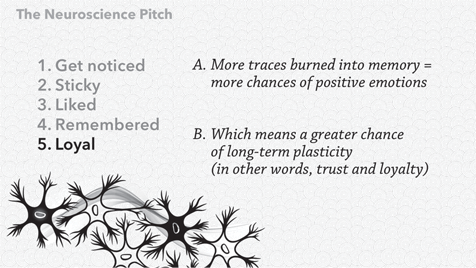

In short, a creative idea creates a chain reaction that eventually turns into brand loyalty. Here’s a quick summary:

A creative idea stands out with an emotional charge that leads to audience participation that leads to greater stickiness that creates a positive experience that leads to greater likability that leads to repeat purchase and finally brand loyalty.

That’s the basic pitch behind the value of a creative idea. At least, these are the reasons marketing experts have used over the years to explain why creative ideas work better.

If you break it down, these steps in the process are basically the secret sauce behind a large part of advertising agency proprietary approaches. Check several agency websites and you’ll find a short narrative that explains their unique approach. They just all focus their narrative on a different part of this basic pitch.

Perhaps it’s, “We create engagement.” Or, “We are storytellers.” Another may claim, “We create culture.” Many others simply state that they put your customer at the center, or they’re influencers, or builders of loyalty. Really what all these companies are claiming is that they understand this basic process. They know how to connect with people through emotional experiences and create a lasting connection.

Now, let’s go through each step of that same pitch, not based on gut experience, but based on the neuroscience I’ve presented in this book. We’ll look at it from a logical perspective on how the brain works and explain all these marketing buzzwords with science.

As consumers, we’re bombarded with millions of messages every day. Just scanning one page of search results or a long list of news stories can overwhelm the conscious mind. To avoid decision paralysis, our brains use a trick that’s been hardwired into our system for ages. We use our subconscious skills of anomaly detection.

Our fast system is the first to kick in. It can quickly process more data than our slow logical system. It’s the first to know if the idea is novel such as an anomaly or just another repeated view of our surroundings.

As our eyes or other senses flood our brains with an endless stream of inputs and stimulus, our fast brain efficiently processes and anticipates all that data, and only retains the most interesting data points. The rest are passed over in order to retain storage space. This isn’t hard. Our brains do this every second of life, whether we’re looking at media or not.

When we hear the stories of how we are being inundated with thousands of marketing messages, this is old news to our brains. This is the part of the pitch that we’ve had wrong over the years. The ever-increasing number of messages isn’t the problem. Bring it. Our subconscious can handle millions of data points flooding in.

We’ve heard of studies where we only have five seconds to get a consumer’s attention, or ten seconds on a web page, or that we give an average of seven eye flicks to each message. Whether that real number is a second or two-tenths of a second, it doesn’t matter. A blink is plenty of time for our subconscious minds to decide if there is an anomaly and let us know if it’s worth our time to take notice.

I want to pause on this point for emphasis. In the digital economy, we are constantly being told that our content needs to be bite-sized. Short. Fast. But marketers are getting this all wrong. The length or size doesn’t matter. All that matters is if there is an anomaly. Something new or different. Something expressed with an unexpected emotion. I could create a small chunk of content that just gets ignored because it isn’t an anomaly.

When you send a message out to consumers in hopes that they will see it, three possible actions will happen.

First, and this is the worst-case scenario, your message goes completely under their radar. It’s ignored. Your customers see the message, and in a split second, their brains reject the idea. It’s not an anomaly. It’s not worth giving any attention. It becomes wallpaper and they pass it by.

The second option is that the message registers, but only a small part of their brain lights up. This would be a classic straightforward message. Just the facts. In this example, your conscious brain slows down and absorbs the information. Remember, with straight-up logic, our memory can only handle a few variables. And it takes a lot of energy to analyze the data when our slow system is in charge. Which means the chances of our brains spending the minimal amount of energy on the idea is real. In this slow state, we try to hurry up and move along, focusing on other things.

Or perhaps your message remains in the subconscious only. It isn’t a big anomaly, so it dabbles around for a bit and then is logged away. It thinks about the information for a short time, but then moves on. Perhaps it isn’t a big enough deal to notify your executive function. Or if it does, there’s no emotion, so your brain isn’t flooded with neurochemicals. Perhaps the prefrontal cortex gives it a little attention, processes that data point, and then it’s over. Your message got through, but it didn’t make a grand entrance.

This is often the fate of a straightforward, logical idea. It has no emotion, so it only lights up a small part of the brain. Engagement is limited. And it probably doesn’t move on to the next phase of locking in a memory. It’s a flash in the slow-system pan. This is not a response you want from a prospective customer.

The third option is more dramatic. Your idea is noticed because it’s a full-fledged anomaly. It’s an emotional idea, and the brain instantly triggers a burst of neurochemicals. The emotion pulls from a variety of experiences as your subconscious quickly relates the new emotion to the past. Think of our exercise when you read the list of brand names and images and you were instantly filled with past thoughts and emotions. The experience was instantaneous. Much faster than seven eye flicks or even a second.

All of this happens lightning fast as your subconscious raises the flag and alerts your CEO. Your brain is flooded with emotion, causing multiple areas to light up. And when you make a decision to get engaged, your brain continues to be flooded with emotion and electricity. In short, your whole brain is alive and alert.

The difference between these last two options is striking. It’s like standing in the shadows or being on center stage under the flood lights. When a burst of emotion is present in the brain, your message is on fire.

So really, the story of this first step isn’t so much that we are flooded with too many messages and we need to stand out from the crowd. It’s that your message needs to be emotional so that your message lights up your customer’s entire brain. The key to making an idea get noticed is emotion. Not just information.

When we look at getting noticed from a neuroscience perspective, the key ingredient is emotional juice. When you present an idea to your audience, you want their brain to fire up like crazy. You need that emotional catalyst. You don’t want to play it safe and just send a logical fact or you risk an efficient brain that will file away your idea too quickly. Sure, it may get through, but it won’t get any fanfare.

Rather, you want that customer to wake up and instantly pay attention. This requires an anomaly and a flood of emotion. Which is another way of describing a standout creative idea.

A creative and emotional idea will break through, not because your brain does a SWAT analysis to break through all the other competing messages. But because the emotional idea immediately shoves out the competition and gets the brain to spend its energy on your message.

Let’s assume your message lit up the whole brain and caught your target’s attention. The next phase of the basic pitch is about engagement that leads to sticky experiences.

From a neuroscience perspective, this next step is a continuation from the first. When the brain is full of electricity and emotion, it’s fully engaged. A brain that has only a few parts that are lit up isn’t really engaged. It still has plenty of untapped power that is busy humming away on other data.

Remember how Dr. Simon taught that our brains don’t retain everything. Maybe 10 percent of all input data.69 Our subconscious sifts through all the messages and only keeps what’s new or necessary. We have to let some things drop in order to stay efficient with the little energy we have. So if a thought or decision doesn’t spike the brain with neurochemicals, then it’s chances of survival and engagement are slim.

The argument of just getting to the product benefits or facts of the message first limits your engagement. These facts may live in short-term logic land for a brief visit, but then they move on and are lost in a sea of data.

If you want your ideas to engage people, you need to light up as much of their brain as possible. You want your left and right side engaged—both the forest and the trees. You want a flood of emotion. You want more neurochemicals released. You want that noodle on fire. Stickiness and engagement require emotions.

In the book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath explore why some ideas stick and others don’t.

For more than a decade, Chip and Dan researched the idea of stickiness. They studied with great teachers and entrepreneurs. They spent hundreds of hours collecting and analyzing sticky ideas, stories, and theories. The results were compiled and used for both Dan’s startup company Thinkwell and with Chip’s students at Stanford University.

What they discovered is that sticky ideas share common characteristics. And they aren’t what most of us would expect.

“Given the importance of making ideas stick, it’s surprising how little attention is paid to the subject. When we get advice on communicating, it often concerns our delivery: “Stand up straight, make eye contact, use appropriate hand gestures. Practice, practice, practice (but don’t sound canned).” Sometimes we get advice about structure: “Tell ‘em what you’re going to tell ‘em. Tell ‘em, then tell ‘em what you told ‘em.” Or “Start by getting their attention—tell a joke or a story.” Another genre concerns knowing your audience: “Know what your listeners care about, so you can tailor your communication to them.” And finally, there’s the most common refrain in the realm of communication advice: Use repetition, repetition, repetition.”70

After digging into what makes ideas sticky, they discovered that many of these standard approaches are no longer valid. For example, a sticky idea doesn’t need to be repeated ten times. Naturally sticky ideas are locked in on the first time they are heard.

Instead, they found six principles that help make ideas sticky. These six are simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional, and stories.

Simple is all about focus. One message is better than ten. Don’t boil the ocean. Find the core idea and stick to it.

Unexpected is about violating expectations. Being counterintuitive. Creating interest and curiosity. Make your idea an anomaly.

Concrete is about being clear. (Not just about the facts.) According to the Heaths, “Explain our ideas in terms of human actions, in terms of sensory information.” Use concrete images and words so that your idea means the same to everyone.

Credible requires authority. Most go instantly for statistics or hard numbers, but that’s the wrong approach. Sticky ideas let people test the idea for themselves. It’s like self-initiated authority. They have to believe it for themselves.

Emotional is about making people feel something. Find the right emotion for the situation, not just the obvious one. We care about the human condition, not abstract ideas.

Stories get people to act. When we hear stories, we are allowed to live the experience without having to perform it ourselves. We create emotional memories that we can quickly reference when a new situation presents itself.

And the one factor they noticed that prevents us from creating sticky ideas is the curse of knowledge. Knowing too much makes us focus on unimportant data. We lose sight of a simple and unexpected idea and try to cram in all the product benefits.

These six principles align perfectly with creative and emotional ideas. They also line up with the standard marketing pitch: Capture their attention (unexpected) in a way that they understand it (concrete) and therefore believe it (credible), which means they will care (emotional) and finally take action (story).

Bringing this idea of being sticky back to neuroscience, these principles also line up with our story so far. Emotional ideas are simple and unexpected (we’ve been calling them an anomalies). Concrete ideas are human, which means they bring up old images and words from your subconscious that are relatable and emotional. Credible ideas are believable because you’ve compared them through emotion with existing memories and you feel good about them. And finally, stories are a common way that we express feelings about the human condition.

You’ll notice that terms such as statistics, facts, and logic weren’t on the list of sticky principles. Yet when many marketers aren’t hitting their numbers, the kneejerk reaction is to play it straight and avoid any emotion at all.

But as we’ve discussed, all logic without emotion won’t work. It’s wallpaper. Like corporate jargon and marketing speak. These aren’t the types of ideas that stick. No matter how much we think that they will resonate with our target audience. They don’t light up the whole brain. Again, logic is slow and short term. If you want to cause more neurons to fire and more neurochemicals to prepare more synapses for locking in a long-term memory, you need emotional and creative ideas in the mix.

You need a balanced approach. Emotions are essential to engagement. If you want to be sticky, logic alone doesn’t cut it.

Now that the brain is flowing with emotional juice, the next part of the pitch is about whether we retain that idea or reject it. What will improve our chances of believing the message and remembering it?

Let’s consider two options. The first is an idea that doesn’t cause the brain to be flooded with emotion. In this instance, the process of laying down a memory trace is more difficult. There aren’t as many neurochemicals to make the memory strong. Which means the repeating pattern between neurons that makes the memory isn’t primed with emotion. The result could be a weak memory trace that could fade, or worse yet, no memory is made at all. We simply think about it for a moment in our short-term memory and then it’s gone.

The second option is that the idea really pulls on our emotions. Our brains are flowing with electricity and emotions and neurochemicals. With all of these elements present, the chances of locking in a strong memory pattern are increased. The communication between neurons is constant and instantaneous. All this helps us lay down a strong memory trace and it helps increase the chances that we will more easily recall this memory. This is the holy grail of marketing—a message that is not only believed, but remembered.

And one of the little neurochemicals that makes all this emotion possible is dopamine. It’s the grease that keeps the gears of memory making moving. But it also plays a major role in rewarding our behavior. The release of dopamine in our brains is the source of our happiness. Most addictive drugs release more dopamine, which is why users feel such a great high. And it’s also an essential ingredient for ideas that are remembered by consumers.

Actually, to put it more boldly, it’s one of the most important factors in determining if an idea will connect with your audience.

Another way of saying it is when we have more dopamine present, the more we like the message. And according to Eric Du Plessis, the biggest factor that influences whether your advertisement or content is remembered is centered on the idea of being liked.

In his book The Advertised Mind, Du Plessis describes the connection between emotions and message performance.

“It is the emotional properties of those memories that determine whether we pay attention or not, and how much attention we pay. The more intense the emotional charge of the associated memories, the more attention we pay. If the charge is positive, it is likely we will feel attracted to what is happening. If it is negative, we will feel repelled.

“This is one reason why advertising that creates a positive emotional response performs better than that which does not—a fact repeatedly borne out by tracking studies the world over.”71

Du Plessis explains his quest that spanned several decades in trying to determine which factors make the biggest difference in successful advertising messages. As the owner of a media research company, he conducted thousands of tests on advertising messages to figure out which elements were most effective. With a large database of commercials and advertisements, he and many others were able to test and rate effectiveness across a wide spectrum that included media length, channels, and other criteria.

In addition to his research, the American Advertising Research Foundation also found the same results in their major study called the Copy Research Validation Project.

In these and other studies done by media researchers, there was one factor that made the biggest difference by a long shot. It wasn’t the length of a video. It wasn’t the number of times we repeated the message. It wasn’t the type of media.

That single most important factor was likeability.

According to Du Plessis, “The objective of this major study (The American Advertising research foundation), managed by Russ Haley and undertaken by a body that had no axe to grind, was to find out which copy-testing research question was the most predictive of a commercial’s actual selling ability. It measured advertisements on all the commonly used copy-testing measures, and found that the simple question, ‘How much do you like the advertisement?’ was the best predictor.

“The conclusion researchers reached was that more than 40 percent of the variation in effectiveness was explained simply by ad-liking scores. If the advertisement is liked, then its ability to create awareness doubles.”72

For media researchers who have no stake in the message, that’s a fascinating conclusion. Certainly, they would hope that longer commercials or more media would be ideal. And yet today, with the rise of digital, we continue to test things such as video length and other data points about the delivery of the message. What we should be focused on is how to create messages that consumers actually like.

Du Plessis continued to analyze his research to discover how you get people to like your advertisements. He came up with a few suggestions.

“Ad-liking is caused by things like humor, characters, aspirational situations, and news that is relevant to the reader.”

His longer list of likable messages includes topics such as entertainment, empathy, and familiarity. And he cautions us to avoid the opposite of liking, with messages that hit negative emotions including confusion and alienation.

The core idea of his research is this—messages that work are those that are liked.

Du Plessis summarized the results, “The most important building block of both recognition and attribution is whether people liked the advertisement. In fact, 80 percent of the variation in recognition is determined by ad-liking, and 51 percent of the variation in attribution is explained by ad-liking.”

“Every advertiser should try to make advertising that consumers like, for a very simple reason: it acts as a multiplier of the effectiveness of the media budget.”

His research and advice live in perfect alignment with our understanding of neuroscience. When our brains are flooded with emotional dopamine, we like the ad and we like the brand. Which in turn helps us more easily retain memories about those positive experiences.

Inside the brain, we have just processed a positive experience. A memory track has been burned into the neurons and is locked in place with a corresponding emotion. That emotion is now part of your subconscious database. Whenever that memory is retrieved or if the brain cross references new experiences against that memory, a lightning fast feeling will be released. The release of dopamine as part of that positive memory will remind you that you like that brand.

Positive experiences are core to us liking, believing, and remembering messages. As marketers and idea creators, we really need to absorb this concept. The most important factor for retention is if the idea is liked.

Businesses that prioritize likable experiences will have an edge on the competition. It’s that simple.

When you’re faced with picking an idea to use in an upcoming marketing campaign, don’t let yourself rationalize away with logic and choose the safe message. Be bold and go with something you actually like. Because if that message is liked, it multiplies your chances of being believed and remembered.

Moving along to the final step in the basic pitch, we reach the concept of brand preference and eventually brand loyalty. This is the step that ties ideas to the bottom line.

The more your customers are exposed to positive experiences with your brand, the chances of them preferring your brand increase. In addition, if you can become a preferred brand by your customers, you increase the chances of them becoming brand loyal. And often loyalty turns into increased income.

These last steps aren’t really something that many argue about. Most of us want loyal customers. We’re usually just haggling over how to get them.

So, to finish off the neuroscience journey on the creative pitch, let’s discuss what happens in the brain after we lay down a memory track. Hopefully the memory trace is strong, meaning the pattern was repeated with a strong emotion and it’s easy for us to recall.

If so, whenever we have another experience with that brand, our subconscious database quickly scans the data and releases a hit of dopamine, reminding us that our memory of this brand was a positive experience.

As long as the brand holds true to the experience and continues to delight the customer, we increase the chances of reinforcing the memory with another positive emotional response. This acts as a positive loop response, with each new experience reinforcing the old experiences. We not only build up the original experience and make that memory trace stronger, but we also create new memories and experiences that are associated with the brand.

All of these additional exposures to positive experiences create more powerful emotions surrounding the brand.

At this point in the customer journey, you have hopefully reached brand preference. The only caution here is to continue to surprise and delight the customer in order to keep the memories strong. Don’t screw things up. If you prioritize engaging customer experiences, you can eventually create a strong enough database of good emotions that your customer will become loyal.

Once your customers are already engaged and have positive experiences, there is ample opportunity for a brand to offer deeper messaging that may be more logical than emotional. These experiences will help reinforce exposures to the positive brand feelings. They may not be ideas that inherently create new emotions, and they may only light up the logical areas of the brain. But they will extend the positive goodwill and can lay down additional knowledge tracks that build up the greater whole.

On the flip side, without additional exposure or positive reminders, even strong memories can fade. Or a negative experience could sully the whole brand database. The takeaway is that brands need to constantly offer positive emotional experiences to keep the memories strong and push customers toward loyalty.

Now that we’ve reviewed the entire pitch through the lens of neuroscience, how does this help us in real world marketing situations? Most likely, we aren’t going to keep a long checklist or fMRI machine handy so we can run down the list of what’s happening in the brain to be more effective.

The take away from this exercise is understanding how important emotional ideas are in the entire customer journey. They aren’t just important in the getting attention phase.

Logic is important too, but we rarely have an issue of not having enough data. The problem in business today is giving emotion an equal opportunity.

The right balance of emotional and rational ideas is important at every step of the journey. In the discovery phase, emotions are critical in pushing out other thoughts and putting your idea on center stage so you can tell your data and story. During the explore phase, emotions play a key role in comparing the data of past experiences to the memory database and they help facilitate the ideal conditions for the establishment of new memories. And finally, at the evaluate phase, when a customer is ready for more information on whether the product is the right solution, emotions still help maintain brand recognition, preference, and eventually loyalty. The balance may change through the journey, but never suppose that emotions aren’t necessary at every step.

Creative and emotional ideas are the best option to get noticed quickly. They make your ideas stickier. They’re more believable. They’re more engaging. They’re more likable. They help facilitate stronger memories. And they help maintain brand preference and loyalty.

This whole process of how we notice ideas, engage with ideas, believe ideas, and eventually remember ideas is all guided by emotion. This whole narrative isn’t about the process being ruled by rational thought or logic. Our rational brain plays a role, but it isn’t the main character. Emotion is at the center.

In a fast-paced industry, our fast, emotional system is the one that initially leads the charge on how we will engage with marketing ideas. And it’s the common denominator throughout the entire customer journey.

So when it comes down to Russell’s big question at the opening of this book, whether a creative idea or a direct statement will work better, the answer is a no brainer.