Pure “Who Are You?” essays

Pure “Who Are You?” essaysYou must remember that you are unique. Your choices throughout life are unique. Just be yourself and tell your story.

—KRIS NEBEL, FORMER MICHIGAN (ROSS) ADMISSIONS DIRECTOR

In one form or another every business school essay question is trying to get you to open up and reveal yourself to the admissions committee. Are you the sort of person whom this most exclusive of exclusive clubs, the top-drawer business school, really wants as a member? What will you be like chatting it up after study group, floating opinions in class, officially representing the school as an alum? More directly than any other topic, the essays in this group try to answer these pivotal “fit” questions. With them, biting the bullet of self-revelation is not optional.

With self-revelation essays your goal is not to sell the admissions committee on the viability of your goals, your ardor for their program, or the grandeur of your accomplishments, but simply to be yourself. These are the worst possible essays in which to tell schools what you think they want to hear. No matter how facile a writer you may be, admissions officers have spent their entire careers reading between the lines, sifting the real from the bogus. If you try to fake them out, you will not win. Be real.

The self-revelation essay can take a great variety of forms—essays about your background, key experiences, passions and interests, uniqueness or diversity factors—in short, anything that might provide a glimpse behind the résumé and into the real you. For the purposes of this chapter, we’ve boiled all these possible topics down to six basic clusters:

Pure “Who Are You?” essays

Pure “Who Are You?” essays

Diversity and cross-cultural international essays

Diversity and cross-cultural international essays

Self-evaluation and strength/weakness essays

Self-evaluation and strength/weakness essays

Creative, visual, and multimedia essays

Creative, visual, and multimedia essays

Failure and mistake essays

Failure and mistake essays

Growth and learning essays

Growth and learning essays

Essay questions of this type come as close to any in directly asking you to, “Tell us about yourself”:

“What matters most to you, and why?” (Stanford)

“What matters most to you, and why?” (Stanford)

“Introduce yourself to your future Ross classmates in 100 words or less.” (Michigan Ross)

“Introduce yourself to your future Ross classmates in 100 words or less.” (Michigan Ross)

“You’re applying to Harvard Business School. We can see your resume, school transcripts, extra-curricular activities, awards, post-MBA career goals, test scores and what your recommenders have to say about you. What else would you like us to know as we consider your candidacy?” (Harvard)

“You’re applying to Harvard Business School. We can see your resume, school transcripts, extra-curricular activities, awards, post-MBA career goals, test scores and what your recommenders have to say about you. What else would you like us to know as we consider your candidacy?” (Harvard)

“What personal qualities or life experiences distinguish you from other applicants?” (UNC Kenan-Flagler)

“What personal qualities or life experiences distinguish you from other applicants?” (UNC Kenan-Flagler)

“You are the author for the book of Your Life Story. Please write the table of contents for the book. Note: Approach this essay with your unique style. We value creativity and authenticity.” (Cornell)

“You are the author for the book of Your Life Story. Please write the table of contents for the book. Note: Approach this essay with your unique style. We value creativity and authenticity.” (Cornell)

They are a varied lot, but they share one potential trap: the sheer breadth of potential subject matter they could inspire you to disclose. The danger is that you’ll try to show who you are in so many different directions that your essay will become a grab-bag of events, significant others, and personal and community experiences loosely strapped together with a blanket theme. An essay that tries to chew off too much will lack the detailed stories that really communicate your unique life experiences (note that even Cornell’s table of contents approach can include running text). Honing in on a limited number of personalized themes and luminous, vividly etched moments is your salvation. Identify key experiences, qualities, or interests of yours, and then drive them home with anecdotes that illustrate your theme.

Some essays, like Duke’s “Share with us your list of ‘25 Random Things’ about YOU,” free you from the need to focus in on a few specific themes or stories. Here, variety in bite-sized and hopefully quirky, even light-hearted chunks will take you far.

For Stanford’s legendary “what matters most,” avoid if at all possible topics like “my family,” “becoming the best person I can be,” “leaving the world a better place,” unless you know you have unusually powerful material and can find a personalized way of stating these tired themes. For all of these essays, think outside the box. The risk of getting dinged for blandness vastly outweighs the risk of choosing a topic or approach that’s too off the wall (do vet it with someone who’s seen a few of these essays, of course). These essays are all about letting your creativity run free.

Case Study: A Remarkable Story from an Unremarkable Applicant |

Andrew wanted to get into Stanford, but I told him he wasn’t being realistic. His 700 GMAT was fine, but didn’t compensate completely for his submediocre GPA in college, his hardly electrifying profile (IT guy with a major consultancy), and his fine but unremarkable extracurriculars. Then Andrew told me his story. Raised in one of America’s poorest and least educated counties by an alcoholic father, Andrew had watched in horror one night as his mother wrestled a gun from his raging father’s hands. Traumatized by his home life, he had imploded academically in college, until his junior year, when he met a studious and traditional Asian student, who simultaneously stole his heart and set him straight. Gradually, Andrew’s life began to turn around, academically, professionally, and extracurricularly until, by the time I met him, he felt he had earned the right to call an MBA his best next step. |

Andrew’s finished essay read like the treatment for an especially moving Hollywood romance—and every word rang true. By getting the admissions committee to focus on his remarkable life rather than his unremarkable profile, Andrew earned admission to Stanford GSB. |

Some schools’ self-revelation topics helpfully force you to narrow your focus:

“If you could choose one song that expresses who you are, what is it and why.” (Berkeley Haas)

“If you could choose one song that expresses who you are, what is it and why.” (Berkeley Haas)

“Describe a defining moment in your life and explain how it shaped you as a person.” (Carnegie Mellon)

“Describe a defining moment in your life and explain how it shaped you as a person.” (Carnegie Mellon)

Never forget that these essays are often sandwiched between more prosaic essay questions where your professional or less personal material will feel more at home. So wherever possible focus these self-revelation essays on the extracurricular you. After all, the odds that an admissions committee member would be truly surprised to learn that you do great liquidity risk models are remote, and claiming that the IMS Health LBO you worked on had the “greatest influence in shaping your character” will sound a tad shallow.

What you spend your free time doing says more about you than what you do in the workplace, where your choices are often decided by someone else. People who sustain deep personal involvements outside their work lives—particularly unusual ones—are simply more interesting than those who spend their off hours vegetating. Moreover, the history of your involvements tells schools something about your commitment and focus. Whether you enjoy volunteering as a dance instructor, collecting antiques, weight training, or working as a math tutor, your extracurricular involvements prove you are not all work—you have “a life.”

Since most extracurricular interests involve other people, learning about your nonwork passions also tells schools how you will respond to the many formal and informal group activities that define the business school experience. And since many B-school applicants are too young to have gained significant leadership experience at work, schools also look to these extracurricular essays to find evidence of leadership. If your nonwork commitments entail helping your community, especially in a leadership role, you’ll be demonstrating the other-directedness that admissions officers like to see in students and alumni.

Demonstrating an intensive enthusiast’s knowledge of an obscure subject and/or dramatizing your passion through a specific memorable experience can produce essays with grit, credibility, and distinctiveness. You may also consider focusing on interests that offset the negative stereotypes every profession drags behind it. If you’re a computer programmer, writing about your love of math puzzles may feed social-skills concerns, but an essay about your leadership of a deep-sea diving team will surprise schools in the best possible way.

As always, it’s not enough to simply describe the experience, interest, or passion. You must also address the why, by, for example, explaining the context that brought you to the experience or interest in the first place, how it makes you feel, and any broader impact it has had on you or the world. Has the experience or passion changed you or taught you anything about yourself or life? Better yet, if the experience or interest has enabled you to benefit others or improve an organization, say so and provide substantiating evidence.

Admissions essays that lack passion can be damaging; “passion” essays that lack passion can be disastrous. Whether you are writing about a defining personal moment or your love of cosplay (costume + play), you must make the reader experience your genuine enthusiasm, and you must make her understand why you feel it.

Prying into your personal secrets is never the goal of a self-revelation essay, so don’t write defensively or guardedly. The schools want to discover whether you’re interesting and likable, so an engaging tone is crucial. If your own life seems boring to you, imagine how it will sound to the admissions committee.

1. Forget that the focus should be you. Self-revelation essays are about getting you to spill the beans about your values, interests, and life experiences. Make sure that your response provides information unavailable elsewhere in your application and insights about you that corroborate the themes of your application as a whole. Don’t waste unnecessary space on information that is not ultimately connected to who you are.

2. Choose inappropriate material. Not everything revealing about you is essay fodder. Some, such as relationships, is too personal. Others—religion, politics—are rife with danger because of their inherent controversy. If such risky topics are essential to who you are, frame your essay so as to defang them of their offensive potential. For example, focus on what your faith or political career have enabled you to do for others, not on doctrinal issues.

3. Fail to admit weaknesses. Failing to acknowledge that you have negatives when a question invites you to discuss them or palming off a disguised strength as a weakness damages your credibility with the admissions committee.

4. Write essays about passions that lack passion. Because self-revelation essays always come down to you—someone you presumably are vitally interested in—yours has failed if it portrays you as a person not enthusiastically engaged in your own life.

5. Bite off more than you can chew. Since many self-revelation essays leave the scope of your answer up to you, your urge to communicate all your strengths may tempt you to spawn a kitchen-sink essay packed with three-sentence generalities about scattered shards of your life but bereft of examples and a unifying theme. Resist temptation.

The uniqueness that makes you who you are is obviously related to the diversity that you can add to your class, so some schools cut right to the chase with pointed prompts like these:

“Academic engagement is an important element of the Wharton MBA experience. How do you see yourself contributing to our learning community?” (Wharton)

“Academic engagement is an important element of the Wharton MBA experience. How do you see yourself contributing to our learning community?” (Wharton)

“What value will you add to London Business School?” (London Business School)

“What value will you add to London Business School?” (London Business School)

“Learning teams are an integral part of Darden’s academic experience. What personal qualities and expertise will you bring to your Darden learning team?’ (Virginia Darden)

“Learning teams are an integral part of Darden’s academic experience. What personal qualities and expertise will you bring to your Darden learning team?’ (Virginia Darden)

Don’t just tell us about yourself, these prompts seem to say; tell us how who you are will enhance our program’s diversity. Diversity and contribution are two edges of the same sword: you may have a truly distinct profile, but how exactly will it contribute to our class?

This emphasis on the unique contribution you’ll make stems from admissions committees’ conviction that we learn more from those we differ from than from pale reflections of ourselves. As a result, typical top-tier programs boast everything from art dealers and zookeepers to plastic surgeons, TV anchors, and helicopter ski guides. And the variety only deepens when geographic origins, cultural backgrounds, and personal pursuits are tossed in the pot.

Because the word diversity still carries an affirmative action tinge, some applicants may assume they can’t add value unless their grandmother was Mohican. Though it’s true that schools show special favor to applicants from U.S. underrepresented minority groups—namely, African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders—class profiles prove beyond a doubt that schools define diversity much more widely than ethnically.

The increase in international representation at business schools is perhaps the most obvious way in which schools have diversified the MBA experience in recent years. None of the top ten U.S. MBA programs today has fewer than 30 percent non-U.S. students, and the top European schools all boast international populations of 86 percent and higher (IMD comes closest to “perfect” diversity at 98 percent). Schools value international exposure not only because new perspectives deepen the classroom learning experience, but because global experiences often go hand in hand with personal growth, tolerance, and enhanced professional value. Of course, being international no longer automatically confers diversity points, as many outstanding Indian applicants have discovered to their chagrin. Applicants from well-represented countries or those who have modest cross-cultural profiles can offset this with vivid, detailed, compelling descriptions of their international stories and through the depth of insight and reflection they bring to their analysis of them.

In the diversity essay, admissions committees are inviting you to help them sculpt the class of maximum variety they seek. The pressure is on you to “prove” your diversity, to convince the schools that you can enhance your classmates’ experience more profoundly than the next applicant. But how you accomplish that is left mostly up to you. What do you think makes you unique, the diversity question asks; what do you think your distinct contribution to your class will be?

However they are worded, the shared intent of schools’ diversity questions is to coax you into highlighting the aspects of your profile that will add the most flavor to your class and benefit to your classmates. Most schools give you maximum leeway by asking broadly about “personal history, values, and/or life experiences,” but one important variant of the diversity essay tries to determine your potential contribution by narrowing your focus to international or cross-cultural experiences:

“Tell us about an experience where you were significantly impacted by cultural diversity, in a positive or negative way.” (INSEAD)

“Tell us about an experience where you were significantly impacted by cultural diversity, in a positive or negative way.” (INSEAD)

“Describe a global business challenge and its relevance to your post-MBA career.” (Georgetown)

“Describe a global business challenge and its relevance to your post-MBA career.” (Georgetown)

Because the range of stories that diversity essays allow you to tell is potentially so wide (what does “personal history, values, and/or life experiences” exclude?), deciding what to write about is the first stumbling block in crafting a standout essay. How can you know which aspects of your profile are really “diverse” or can actually constitute a “unique contribution” to future classmates? One way is by simply inventorying your life, as discussed in Chapter 1. Start with the narrow, conventional definitions of diversity—ethnic background or gender. If you are an underrepresented minority, then consider discussing that fact to whatever depth captures its importance to your life. Next, look at socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic types of diversity. If you overcame an economically disadvan-taged childhood, identify strongly with your family’s cultural roots, or come from a foreign country or a U.S. region underrepresented at your target school, these are diversity factors you will want to expand on in your essay.

Your education may have been unusual (e.g., your school’s location or affiliation, your major or scholarships), your religious or spiritual life may be significant and unusual, your post-MBA goals may set you apart, even your sexuality or specific family dynamics (if handled properly) may convince the schools that you’ll contribute a distinct perspective. Skills or areas of expertise, unusual or challenging life experiences, even personal qualities or traits such as the gift of humor are all valid, potentially fruitful diversity topics.

If after drawing up your personal diversity inventory you still think you’re too unexceptional, don’t fret. A diverse class doesn’t mean a class filled with demographic outliers; it also means one that includes a good number of strong applicants with traditional, “middle-of-the-road” profiles. If you feel that’s you, then tell your “normality” tale as engagingly and vividly as you can. Your charm and winning presentation can themselves create the sense of potential contribution that schools look for. Personality, in other words, can be a “diversity factor.” Many qualified applicants who believed schools eliminated them for “diversity” reasons actually eliminated themselves at the start by assuming they had none. Your diversity elements may not be terribly unusual taken individually, but together they may well make you memorably distinct.

What the Schools Say

We define diversity much more broadly than some people do. For us, the academic environment is enhanced when you’re challenged and confronted by a multiplicity of perspectives. Students have a lifetime to be around people like them in their same industries, so an MBA program is a time to really confront your own values.

—MAE JENNIFER SHORES, UCLA (ANDERSON)

Aside from the content you choose, what can you do to ensure that your diversity essay really convinces admissions officers that you can make a significant contribution? First, you must provide vivid details and concrete examples that automatically individuate you because they’re specific to your life. Since the general phrases or themes you will use to label your uniqueness have probably been used before, it’s your examples that will give your diversity essay its real singularity. Make sure they have color and bite.

Second, it’s not enough to simply name your differentiators and drop in a few examples. You must also address the diversity essay’s contribution component (sometimes stated in the question’s wording, sometimes not, but always implied). That is, explicitly state how your diversity or uniqueness factors have benefited or educated you, what they’ve added to your life, and how they will benefit classmates. For example, what life lessons or insights did you gain from growing up in Mozambique or abandoning your budding career as a rock musician or chasing your passion for Tang Dynasty antiques to Nepal? And in what ways will you share these lessons or insights with your future classmates? By joining the African Students’ Club? By playing for classmates during orientation week? By explaining antique auction bidding theory in class? In other words, show schools that you’ve already begun envisioning how to share your special traits and interests within their program.

1. Assume that diversity can be defined only in terms of certain underrepresented races or that uniqueness is limited to tales of being raised by cannibals or overcoming obscure medical conditions. Schools define both terms loosely.

2. Use “unique contribution” material that really isn’t all that singular—being a mother, being Canadian, making your high school’s varsity basketball team. Dig deeper.

3. Focus on questionable, inappropriate, or negative uniqueness factors, such as your psychic gifts or your weekend recruiting work for underground terrorist cells. Stay positive and within bounds.

4. Try to cram too many uniqueness factors into your essay, thus producing a bland, all-inclusive porridge unsubstantiated by examples. Focus on three or four diversity themes.

5. Waste space informing schools how great diversity is. They know this; that’s why they asked the question. Talk about how great your own diversity is instead.

This group of questions gets at who you are by asking you to evaluate yourself and your strengths and weaknesses, or to discuss how others do so:

“Give a candid description of yourself, stressing the personal characteristics you feel to be your strengths and weaknesses and the main factors, which have influenced your personal development, giving examples when necessary.” (INSEAD)

“Give a candid description of yourself, stressing the personal characteristics you feel to be your strengths and weaknesses and the main factors, which have influenced your personal development, giving examples when necessary.” (INSEAD)

“What are the 2 or 3 strengths or characteristics that have driven your career success thus far? Do you have other strengths that you would like to leverage in the future?” (North Carolina)

“What are the 2 or 3 strengths or characteristics that have driven your career success thus far? Do you have other strengths that you would like to leverage in the future?” (North Carolina)

Self-evaluation essays give you another slot in which to insert stories that flesh out the committee’s picture of you while they run a reality check on your self-awareness. Do you have a mature, balanced understanding of yourself? Do you see the same strengths and weaknesses the adcoms have started to notice, or do you live in perpetual denial? These essays also offer you a chance to gain credibility by simply being honest. If you come clean in these essays, admissions officers will be more willing to lend credence to your positive claims about yourself.

The strengths you discuss in this essay must complement (if not entirely overlap) the strengths your recommenders cite and your application as a whole communicates. Naturally, all business schools value skills like leadership, team skills, integrity, analytical ability, communication skills, and cultural adaptability, but each school broadcasts its own peculiar mix of valued traits (e.g., Haas’s innovation, Chicago’s iconoclasm), which you should be well aware of before mapping this essay. Ideally, your essay will blend “obligatory” business school strengths, such as leadership, with strengths that are really personal to you, like artistic ability, spontaneity, or adventurousness.

Moreover, since leadership, team skills, and the like are broad terms that encompass many distinct traits, try to give your essay individuality by finding the particular traits that best capture you. Avoid strengths like “persistence” and “dedication.” They’re not only vague and clichéd, but they will paint you as a worker bee rather than a dynamic leader.

The laziest and most common structure for self-evaluation essays is to take up each strength or weakness in turn, illustrate it with an example, and then awkwardly transition on to the next: “My second biggest strength is my …”. To avoid this, find some common element or quality that your strengths share and weave your essay around that, or, better yet, find a single story (a work project, for example) or activity (your salsa class) that will illustrate all your strengths and weaknesses in one fell swoop. It’s awfully hard to be original when discussing traits you likely share with most of humanity, so remember that in this essay your creativity and uniqueness will derive from the special combination of strengths you cite and—most of all—from the stories you tell to illustrate them. If you can, draw explicit connections between your strengths and the specific B-school forum (class, study group, etc.) in which you plan to leverage them.

For most applicants, the minefield at the heart of the self-evaluation essay is the weakness section. This is not because most applicants have an embarrassing number of weaknesses—the vast majority don’t—but because they refuse to admit they have any. Thus admissions officers must trudge through a purgatory of “good weaknesses”: perfectionism, workaholism, impatience with people with low standards, and so on. Such “strengths in disguise” may actually have worked 30 years ago when adcoms first encountered them, but trotting them out today only shows unimaginativeness, immaturity, and dishonesty—not especially becoming traits. True weaknesses, the kind schools want to hear about, are personal characteristics that most of us suffer from and that can be reversed with sufficient awareness and effort: poor time management, procrastination, indecisiveness, and so on.

Do more than merely “cite” your weakness. Give a brief example or explanation of how it has affected you, what specifically you are doing now to rectify it (classes, mentoring, etc.), and—if relevant—which specific B-school resources can help you purge this Achilles’ heel for good. You don’t want the self-evaluation essay to read like a static report card but as a snapshot of confident self-transformation—a savvy, evolving person working on her flaws, deepening her assets.

As applicants have become savvier both about the importance of the admissions essay and strategies for writing effective ones, some business schools have turned to less verbal methods to accomplish the underlying purpose of the self-revelation essay: to expose the real you.

What the Schools Say

Essay Three [now essay 2] lets people stand out and talk about who they are. If you’ve worked in banking and your GMAT is average, then Essay Three lets you stand out and show how you’re different. We get collages, recipe books, photo albums. Now we have size restrictions. We say, Think outside the box, but it has to fit in the box.

—ISSER GALLOGLY, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY (STERN)

NYU Stern pioneered the nontextual approach with its “Describe yourself to your MBA classmates” personal expression essay more than a decade ago. By allowing applicants to use “almost any method” to communicate their uniqueness, Stern gives applicants a daunting creative challenge since the only submissions it currently excludes are perishable items (a blow to chefs everywhere). The trick is turning the intimidation factor around and viewing it as a potentially fun opportunity to unleash your creativity and truly differentiate yourself.

What the Schools Say

A successful Essay Three [now essay 2] is one in which an applicant is able to share aspects of himself or herself that are not otherwise highlighted in the application, such as a unique experience, specialized skills and strengths, or a personal passion. The most memorable nontext submissions often use their creative form to dramatize what an applicant will bring to the Stern community. For example, applicants who have a passion for cooking—or who are self-proclaimed “foodies”—have submitted a menu or recipe book that blends some of their favorite dishes with various aspects of their lives. Applicants who have lived in or traveled to many parts of the world have created a custom-made passport or constructed a mini-suitcase with memorabilia and photos. We have even seen applicants represent their lives in the context of the NYU Stern brand—by making their own personalized Stern brochure.

—ALISON GOGGIN, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY (STERN)

Don’t let Stern’s invitation to abandon prose make you feel guilty about submitting text—a substantial percentage of all Stern applicants do wind up submitting written essays. Just make sure it gives ample insight into your personality and character. If you do decide to eschew words, be sure your idea—whether it’s a photo collage, a product you worked on, or a meticulous Lego replica of your childhood home—truly captures who you are. Creativity for its own sake usually comes off as gimmicky; creativity that expresses your passion is much less likely to miss the mark. Nontext ideas tried in the past have included:

An Excel-based Jeopardy game in which each answer category highlighted an aspect of the applicant’s life—clicking on a cell revealed the answer.

An Excel-based Jeopardy game in which each answer category highlighted an aspect of the applicant’s life—clicking on a cell revealed the answer.

An eight-page autobiographical Web site featuring 52 photos and a humorous Fun Facts section that the enterprising applicant had professionally printed and bound as a book.

An eight-page autobiographical Web site featuring 52 photos and a humorous Fun Facts section that the enterprising applicant had professionally printed and bound as a book.

A giant world map on which a globe-trotting applicant pasted photos of herself in places like Sudan, Sri Lanka, and Macedonia and accompanied by captions explaining what she had learned in each location.

A giant world map on which a globe-trotting applicant pasted photos of herself in places like Sudan, Sri Lanka, and Macedonia and accompanied by captions explaining what she had learned in each location.

A set of manga-style game cards, each emblazoned with the image of the applicant revealing one of his particular skills (skateboarder, chef, guitarist).

A set of manga-style game cards, each emblazoned with the image of the applicant revealing one of his particular skills (skateboarder, chef, guitarist).

A personalized scrum board festooned with sticky notes showing the tasks, “in-progress” projects, and goals of 15 years, from learning Spanish to earning a patent.

A personalized scrum board festooned with sticky notes showing the tasks, “in-progress” projects, and goals of 15 years, from learning Spanish to earning a patent.

Postcards from all the locations an international applicant had lived, with descriptive text inserted on the back of each card and the whole series artfully bound together into a booklet.

Postcards from all the locations an international applicant had lived, with descriptive text inserted on the back of each card and the whole series artfully bound together into a booklet.

An Excel spreadsheet that carried the reader through a multiple-choice compatibility test with the applicant (and allowing the admissions committee to score their results: “WOW! We are exactly alike!”).

An Excel spreadsheet that carried the reader through a multiple-choice compatibility test with the applicant (and allowing the admissions committee to score their results: “WOW! We are exactly alike!”).

If you decide these inventively visual approaches just won’t work for you, there is still significant room for creativity using the 500-word essay format. Aside from the photo collage approach, applicants have submitted:

A self-penned article from the applicant’s school newspaper in which he decried classmates’ obsession with business school admission. The text accompanying the submission cleverly elaborated on the theme of “maturation.”

A self-penned article from the applicant’s school newspaper in which he decried classmates’ obsession with business school admission. The text accompanying the submission cleverly elaborated on the theme of “maturation.”

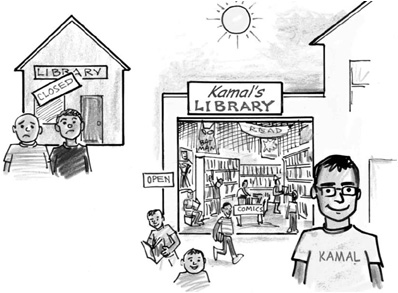

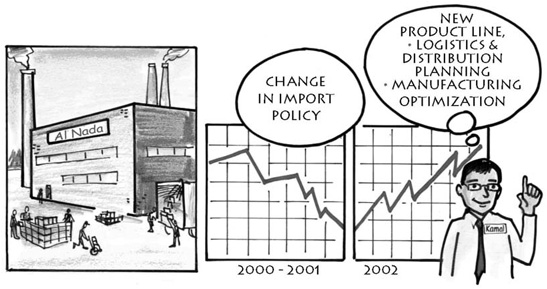

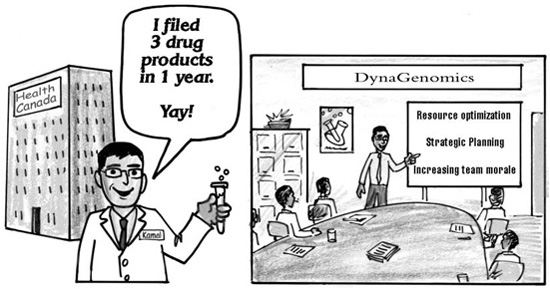

An autobiographical essay illustrated by multicolor comic-book cells created by the applicant himself, and introduced by an anecdote about his childhood love of comics and books. (See sample essay on p. 136.)

An autobiographical essay illustrated by multicolor comic-book cells created by the applicant himself, and introduced by an anecdote about his childhood love of comics and books. (See sample essay on p. 136.)

Text-based essays without visuals can also be very effective, whether it’s a poem (only if poetry is important to you), a eulogy, a (brief) chapter in your autobiography (but don’t just drop in your Booth PowerPoint or Cornell “Life Story” essays here), an imagined media interview with you once you’re successful, a vivid description of a typical day, and so on. Stern will probably have seen many of these before, but it’s always the execution, personality, and honesty that make a creative essay work—the metaphor, idea, or framework is just the starting point. If your description of yourself sparkles with personality and joie de vivre and the stories you focus on show you’ve led an interesting life, the admissions committee will forgive you for not writing it in crayon or iambic pentameter.

In 2010, Stern expanded the range of possible submissions it would entertain to include multimedia essays (it had previously nixed anything that had to be “viewed or played electronically”). The inspiration for that decision was the adoption of digital and multimedia essay formats by schools like Chicago, UCLA, and Notre Dame, which we discuss next.

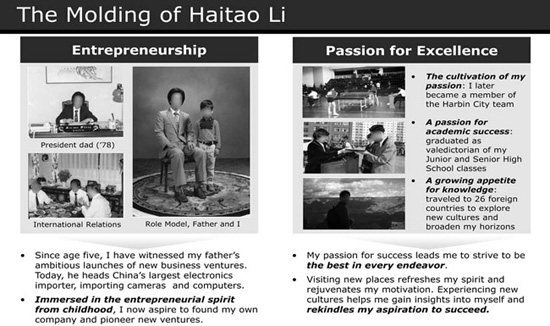

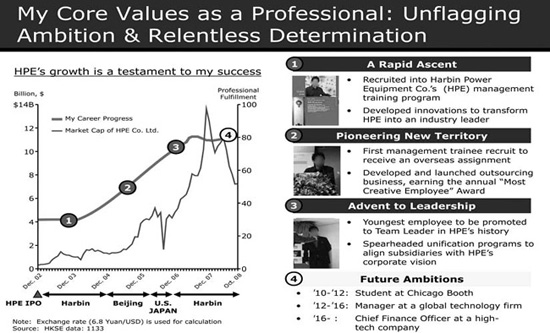

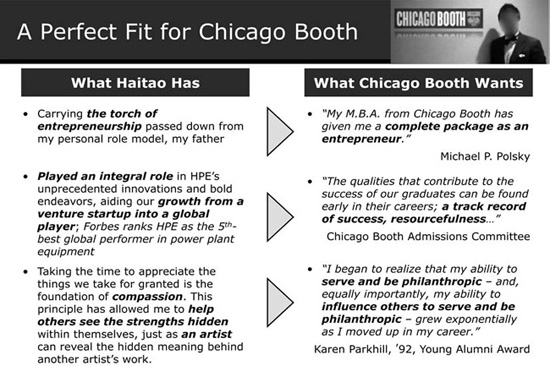

Chicago and Notre Dame’s “slide presentation” essays are not really refinements of Stern’s “(almost) anything goes” approach in that they curtail rather than expand the potential range of creative responses. Despite both schools’ openness to PDF submissions, PowerPoint has quickly established itself as the standard format, and before you could say “spontaneity be damned,” a de facto “best practice” emerged: applicants began using each slide to capture a different aspect of their profile (professional on one slide, community on another, and so on), with some content-strapped applicants using the first slide as a “cover slide” that introduces the set.

Some applicants thrived within these constraints; some reverted to clichés: timelines, bar charts graphing applicants’ personal “return on assets,” and company logos and generic clip art proliferated. Some ideas mercifully failed altogether, such as submitting four slides completely devoid of visuals and reiterating information readily available elsewhere in their application.

What the Schools Say

To me this is just four pieces of blank paper. You do what you want. It can be a presentation. It can be poetry. It can be anything. … You can tell when someone figures out how to work with the ambiguity and really embraces that, rather than saying, “I’m going to play it safe and regurgitate what is in my application already.”

—ROSEMARIE MARTINELLI, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

The best “slideware” essays are those that focus on some distinctive aspect of the applicant’s life not discussed elsewhere, and then find some creative (as opposed to gimmicky) way to link each slide through a governing metaphor (as Sergei does with his “Top Secret” conceit in the PowerPoint sample on p. 139). A pronounced emphasis on images, with text used primarily for page titles and captions, and an ability to create a sense of an unfolding visual story from slide to slide also work well. Be strategic. Since PowerPoint slides can be decisive in close-call cases between similar applicants, use them to work against type:

If your career is or will be in finance, steer clear of charts, text, and timelines showing career progression (let all your IB competitors work that cliché).

If your career is or will be in finance, steer clear of charts, text, and timelines showing career progression (let all your IB competitors work that cliché).

If your career is or will be in marketing, avoid the “I’m a brand” gymnastics that your rivals will trot out. Focus instead on some substantive hobby or activity (perhaps one that bolsters the analytical, quantitative, or leadership parts of your profile).

If your career is or will be in marketing, avoid the “I’m a brand” gymnastics that your rivals will trot out. Focus instead on some substantive hobby or activity (perhaps one that bolsters the analytical, quantitative, or leadership parts of your profile).

As with Stern’s creative essay, capturing who you are and standing out from the pack will always trump unimaginative content, no matter how polished and gussied up that content is. One applicant’s PowerPoint essays featured nothing but book covers (including a cheeky Multiorgasmic Man) and ended with a slide of an empty bookshelf, captioned with, you guessed it, “The Future.” Though this essay failed to show a single photo of the client and clearly did not take much effort or creativity, it accomplished what ultimately matters more: (1) it captured who the applicant was, and (2) it differentiated him through a unique approach. Chicago admitted him.

Don’t get so caught up in finding snazzy visuals or devising a creative metaphor to unify your essay that you forget the essay’s purpose: to introduce yourself truthfully to the school and your classmates.

The latest twist on the creative essay is the video essay:

“This video essay is an opportunity for the Admissions Team to meet you - wherever you are in the world. Please approach this as a conversation with us. The spirit of the questions is for us to get to know you. There are no right or wrong answers. You will use the video frame on this page to record spontaneous answers to a randomly selected question.” (Kellogg)

“This video essay is an opportunity for the Admissions Team to meet you - wherever you are in the world. Please approach this as a conversation with us. The spirit of the questions is for us to get to know you. There are no right or wrong answers. You will use the video frame on this page to record spontaneous answers to a randomly selected question.” (Kellogg)

“Imagine that you are at the Texas MBA Orientation for the Class of 201X. Please introduce yourself to your new classmates, and include any personal and/or professional aspects that you believe to be significant. Select only one communication method that you would like to use for your response.

“Imagine that you are at the Texas MBA Orientation for the Class of 201X. Please introduce yourself to your new classmates, and include any personal and/or professional aspects that you believe to be significant. Select only one communication method that you would like to use for your response.

—Write an essay (250 words)

—Share a video introduction (one minute)

—Share your about.me profile” (Texas McCombs)

For schools like Texas and MIT Sloan, choosing the video format is optional; for schools like Kellogg and Yale it's a mandatory part of the application process, supplementing the written essays.

Although the potential anxiety induced by a one- to two-minute video makes the PowerPoint format seem like a walk in the park, the potential advantages of videos for the schools are obvious. In addition to gauging the same skills--ability to introspect and communicate--that the traditional written essay measures, the video also gives schools insights into “applicant personality, sense of humor, intonation, verbal skills,” according to UCLA Anderson admissions dean Mae Jennifer Shores. Call it an interview before the ultimate official interview. For example, the audio-visual essays that applicants submitted to UCLA when it first experimented with the format employed a variety of production approaches, themes, and content:

One applicant employed a soundtrack of music and battlefield sounds to describe his entrepreneurial resourcefulness in gaining critical intelligence from Iraqi civilians while serving as an Army Ranger.

One applicant employed a soundtrack of music and battlefield sounds to describe his entrepreneurial resourcefulness in gaining critical intelligence from Iraqi civilians while serving as an Army Ranger.

An Asian applicant overcame a strong accent through a smiling and poised self-presentation and the sophisticated use of establishing and face-the-camera narration shots, professional scene transitions (cross-fades, iris wipes, etc.), embedded live-action video, and clever zooming and panning techniques over still photographs of his extracurricular passions.

An Asian applicant overcame a strong accent through a smiling and poised self-presentation and the sophisticated use of establishing and face-the-camera narration shots, professional scene transitions (cross-fades, iris wipes, etc.), embedded live-action video, and clever zooming and panning techniques over still photographs of his extracurricular passions.

An avid golfer described how he recovered from a triple-surgery shoulder dislocation to resume his beloved pastime, deftly drawing on still-shots of his shoulder X-rays and action shots showing the applicant in physical therapy and sinking putts on the fairway.

An avid golfer described how he recovered from a triple-surgery shoulder dislocation to resume his beloved pastime, deftly drawing on still-shots of his shoulder X-rays and action shots showing the applicant in physical therapy and sinking putts on the fairway.

Similarly, audio essays submitted to UCLA Anderson featured:

A former bassist for a California punk band responded to UCLA’s “surprise” prompt with a relaxed and bemused narrative about his rock star days (“that’s right, a punk band”) and a brief snippet of his greatest hit.

A former bassist for a California punk band responded to UCLA’s “surprise” prompt with a relaxed and bemused narrative about his rock star days (“that’s right, a punk band”) and a brief snippet of his greatest hit.

An Asian analyst who moonlighted as a break dancer used a hip-hop soundtrack to unfurl an essay highlighting not only his artistic side but his leadership (he led his college’s dance group) and social impact (his dance group offers community outreach classes).

An Asian analyst who moonlighted as a break dancer used a hip-hop soundtrack to unfurl an essay highlighting not only his artistic side but his leadership (he led his college’s dance group) and social impact (his dance group offers community outreach classes).

An urban professional revealed his inner country boy and guilty love of rodeos and country music with a well-written piece about a childhood spent “scratching my showpigs’ bellies and manicuring hooves” at the county fair. A tour de force.

An urban professional revealed his inner country boy and guilty love of rodeos and country music with a well-written piece about a childhood spent “scratching my showpigs’ bellies and manicuring hooves” at the county fair. A tour de force.

A former comedienne who performed on late-night talk shows, taught improv comedy, and produced shows in Hollywood deftly connected the “make people feel good” impulse behind her comedy career to her current career in the nonprofit space.

A former comedienne who performed on late-night talk shows, taught improv comedy, and produced shows in Hollywood deftly connected the “make people feel good” impulse behind her comedy career to her current career in the nonprofit space.

An editor for a book publisher explained how she was approached by agents for a book deal (I Am Neurotic) when she started a blog featuring peoples’ most interesting neuroses.

An editor for a book publisher explained how she was approached by agents for a book deal (I Am Neurotic) when she started a blog featuring peoples’ most interesting neuroses.

Many multimedia essays are polished and professional; others are decidedly folksy and unrefined. But the ones that work rarely do so because of their sophisticated presentation. Rather, they are effective because the applicants (1) project themselves in an authentic, relaxed, engaging, and even humorous manner and (2) focus on material that genuinely matters to them and reflects a significant involvement in their lives (the more off the beaten path, the better). If your audiovisual essay can manage these two, your production polish or lack of it won’t matter a whit.

In video essays, as in actual interviews, you want confidence, poise, plenty of smiles, and eye contact. Since you have the added benefit of editability (at least for schools who allow you to prepare your video essay beforehand), your finished product should be devoid of nervous twitches, pets leaping into the picture frame, car horns, and other distractions. On the other hand, don’t practice it so much that you come across like a talking manikin.

As with a written essay, start with an outline and then develop it into a script. Once you have a solid idea of what you’ll say (directly to the camera and in your voice-over narration), create a storyboard or visual map showing the content and timing of each scene. The elements that make written essays work will also serve your audiovisual essay well: providing context, using specific examples, and including reflective passages where you tell the viewer how you felt or what an example or event means to you, and so on. And, as with a written essay, edit, revise, edit, and edit again. The multimedia essays’ strict time limits will force you to be concise, but you must balance your concision with the need to maintain a conversational spoken voice. Never speed up your narration just to fit the content into your time limit.

Once you know how many words you can comfortably and naturally speak in the one- or two-minute window given you, begin work on the visuals that will illustrate your essay. As a general rule, your essay should strike a balance between scenes in which you directly address the viewer and illustrative scenes where you narrate over the visuals of your story. Your goal will be to achieve a natural rhythm between scenes in which you directly address the camera and illustrative visuals.

You need not start the essay with an opening scene in which you address the camera, but you must introduce yourself and indicate your theme (“Though I am an IT consultant by day, even my friends are surprised to learn that I spend my off-hours high-wire walking between Chicago’s skyscrapers”). Early on and then occasionally throughout the video, you should return to these direct-address scenes in which you face the camera. Why? Because the purpose of these essays is to introduce and personalize yourself to the admissions committee, so committee members must see you and be addressed by you. On some level, visual essays function as interviews in which the admissions committee can evaluate you for raw verbal skills, poise in spoken delivery and body language (eye contact, smiling, etc.), and general personableness.

Your transitions between direct-address scenes and illustrative visuals should be continual but measured, avoiding both frenetic cutting and long static scenes of inaction. If you integrate still images in your video, experiment with gradual pans or zooms within the image to create the impression of movement (à la documentarian Ken Burns). Effective videos continually work to hold the viewer’s attention and sustain visual interest (as a rule of thumb, a one-minute video might entail 12 to 15 shots).

Only when you have fleshed out your video’s basic rhythm of direct-address scenes and voice-over visuals should you concern yourself with snazzy video techniques like fades or wipes for transitions, pans and zooms for still images, and so on. And don’t try to tackle all this alone. Ask people who know you to evaluate whether your script captures you well and to help you with the actual filming. This is, like it or not, a major undertaking.

A lot of business schools have concerns about authenticity. [Our multimedia essay] was a way to get a more authentic view of a candidate.

—MAE JENNIFER SHORES, UCLA ANDERSON

1. Feel obliged to submit a nonwritten essay if you feel you can’t create a good one. Text-based essays that are straight from the heart, well-written, and creatively framed/presented can still equal or surpass most visual essays in effectiveness.

2. Forget that visual essays are a hybrid form of essay-interview: your face and/or voice will be front and center, so if you’re bashful or disinclined to smile when a camera is pointed at you, you won’t have written words to hide behind.

3. Try to oversell your devotion to the school. Avoid devoting an entire PowerPoint slide to Chicago’s lovely Hyde Park campus or photos of its brilliant faculty. Avoid video essays in which you do cartwheels in front of the admissions office or get interviewed by your best friend dressed as the school mascot.

4. Employ clichéd or goofy ideas: PowerPoint essays that use bar graphs or video essays in which you become a superhero or perform stupid pet tricks for the admissions committee.

5. Forget that creative and visual essays live or die to the extent that they (1) communicate some passion or experience that’s deeply important to you and (2) show you to be an engaging, world-directed, socially skilled achiever. Everything else is just smoke and mirrors.

No one likes to fail—least of all achievers with the smarts and drive to aim for the best business schools. For you, the only thing worse than failing might be having to admit mistakes to complete strangers whose admissions verdict can decide your professional future! Yet however counterintuitive it seems, some business schools expect you to be able to admit, analyze, and learn from a real blunder.

Your ability to admit and coolly dissect a personal foul-up evinces maturity and humility, qualities that business schools in our scandal-plagued era value dearly. Conversely, pretending you can outfox the admissions committee by slipping them a success wrapped up as a failure immediately announces immaturity—in (1) trying to pretend you’ve never failed and (2) thinking you can hoodwink admissions officers who’ve seen it all.

Moreover, failures are classic obstacles, and how you overcome difficulty says a lot about your character, resilience, and willingness to change in response to the feedback reality gives you (as we’ll see in the next section of this chapter). Like anyone, admissions officers also love to hear “come-from-behind” tales in which the hero (you) overcomes her tragic flaw to redeem herself in the closing minutes. Failure ← understanding ← redemption is a traditional pattern in all storytelling; use it in this essay to rouse the reader’s interest and sympathy.

Failure also often says good things about those who strive for the brass ring but miss. Ambition, boldness, innovation—these and other positive traits usually cling to those who “dare mighty things.” Finally, responding to the failure question honestly will pay dividends all across your application. Once the schools see that you’ve been aboveboard about your failures, they’ll be much more inclined to take your word about your successes.

“Describe a circumstance in your life in which you faced adversity, failure or setback.” (Tuck)

“Describe a circumstance in your life in which you faced adversity, failure or setback.” (Tuck)

“Describe a time in the last three years when you overcame a failure. What specific insight from this experience has shaped your development?” (Berkeley Haas)

“Describe a time in the last three years when you overcame a failure. What specific insight from this experience has shaped your development?” (Berkeley Haas)

“Describe the achievement of which you are most proud and explain why. In addition, describe a situation where you failed. How did these experiences impact your relationships with others? Comment on what you learned.” (INSEAD)

“Describe the achievement of which you are most proud and explain why. In addition, describe a situation where you failed. How did these experiences impact your relationships with others? Comment on what you learned.” (INSEAD)

Though mistake and failure are unambiguous terms, many applicants react to them like cornered ferrets. Defensively denying that they could be anything less than flawless, they narrate “failures” that are really 80 percent successes, team failures in which they played a marginal role, or moments of adversity in which their only lapse was being victimized by fate. Think again. Failure means you personally were to blame; setback only means things didn’t turn out as you wished. Even though failure prompts don’t always require the failure to be yours (it could be your team’s), looking for examples that allow you to shift the blame really defeats the non-sinister purpose of these essay questions.

Frustrated by the evasions such straightforward failure questions elicit, some schools have softened the question to situations where you didn’t meet your standards, as in Michigan’s “Describe a time in your career when you were frustrated or disappointed. What advice would you give to a colleague who was dealing with a similar situation?” But the intent remains the same: they want a screwup. Always read carefully to determine whether the question allows you to draw from failures in any part of your life or only from your professional or academic life.

When brainstorming for the “perfect” failure story, remember that an ideal example will meet four criteria:

It was clearly your fault because you, for example, let someone down, conspicuously and unexpectedly failed to achieve a reasonable target, or misread or misreacted to a situation.

It was clearly your fault because you, for example, let someone down, conspicuously and unexpectedly failed to achieve a reasonable target, or misread or misreacted to a situation.

It sheds light on an activity or experience not treated elsewhere in your application.

It sheds light on an activity or experience not treated elsewhere in your application.

It is no more than five years old but is not so recent that you haven’t yet applied the lessons it taught you.

It is no more than five years old but is not so recent that you haven’t yet applied the lessons it taught you.

It reflects some positive aspect of your personality, such as initiative.

It reflects some positive aspect of your personality, such as initiative.

These aren’t conditions that all effective examples will meet, of course, but they are an ideal to shoot for. Popular topics for failure essays include failed startups, being laid off, academic reversals, athletic failures, and rookie mistakes at work. But the best failures are often doozies of misadventure for the very reason that exceptional individuals often attempt things that others avoid, or they rise to positions where their mistakes are magnified by the scope of their responsibility. If you have experienced a truly distinctive, outsized failure, this may be just what the adcom ordered. After all, if you must come clean about a real failure, there’s something to be said for failing big (provided your failure didn’t bring down the entire subprime mortgage market). So don’t give them some milquetoast peccadillo—choose a blunder that only a big risk-taker swinging for the fences could manage.

Since schools ask you to “describe a failure,” many applicants mistakenly burn through three-quarters of the essay’s prescribed length detailing the ins and outs of their fiasco. The failure itself, however, is perhaps the least important section of the essay. At least as critical are your analysis of the failure, the lessons it taught you, and the ways you applied those lessons later on.

The first section of the essay, the context and failure statement, should give just enough information to pique the reader’s interest and clarify that your failure was a real one, was indeed your fault, and had specific consequences. Since being able to stand up and admit failure is a key reason why schools pose this topic, your statement of failure should be unambiguous. You blew it.

But the failure statement should also be short and sweet. Avoid trying to wring pity from the admissions officers, but also stay away from orgies of self-recrimination. As we noted in Chapter 1, the tone of your entire application should be positive; so keep this part of the essay factual, mature, and above all brief.

The analysis section of the failure essay exists only to demonstrate that you have the self-awareness and analytical skills to dissect the causes of your failure. Don’t use this brief section to try to shift the blame to someone else, rationalize your failure away, or strain toward a happy ending. Focus objectively and succinctly on what you did wrong and why. The only place for emotional expression in this essay is in stating your deep regret for the negative impact of your failure on others. No whining or wheedling.

If you’ve played your cards right you’ll have reached the essay’s halfway point (or thereabouts) with the pungent details of your blunder safely behind you and plenty of room still remaining for the essay’s positive payoff: what your failure taught you. Aim for multiple takeaways to show how conscientiously and exhaustively you examined this “teachable moment” to identify where you went wrong and how. Generally, the greater the magnitude of your initial failure, the more lessons you should be able to glean from it. Avoid banal, generalized lessons like, “I learned that leadership means taking responsibility for your mistakes.” This should be implicit in the much more specific and personalized lessons you draw.

Much better are lessons like failing to turn to others for help; failing to listen; mishandling stress, conflict, or team dynamics; delaying a decision until you had more data; or failing to correlate ideal objectives with hard realities. What steps did you take to ensure that you will not have to learn these specific lessons again?

If the lesson you learned was that you lacked sufficient self-knowledge about your skills, strengths, or career goals, you can actually leverage your failure to advance your case for needing an MBA.

If your failure has a happy ending, it should come in the essay’s last section, where you show yourself redeeming your earlier lapse. This part of the essay answers the essay’s implicit questions: What do you proactively do after you’ve realized you failed? What corrective actions do you take? Brainstorm for a specific subsequent occasion when you encountered circumstances similar to those of your failure but in which you responded differently and effectively because of the lessons your failure taught you.

1. Write about a failure that isn’t one. To say you “failed” because INSEAD dinged your application last fall or because you once reduced costs by 15 percent instead of the 25 percent you intended is to misunderstand what schools mean by failure.

2. Describe a trivial failure. Recounting the time your fraternity’s barbecue imploded may shed light on your skills as an organizer (or cook), but it doesn’t meet the significance level business schools expect.

3. Reveal a failure that exposes inexcusable flaws in your character. Getting fired for sexual harassment or committing a hate crime are true failures, no doubt, but they’re far too egregious for schools to overlook.

4. Write too much about the failure itself. If you overload your essay with every gory detail of your lapse, you won’t have enough space for the section that can redeem you—the lessons learned and applied.

5. Choose a failure that’s more than, say, five years old or whose subject matter is otherwise inappropriate. Failing to make your high school’s chess club may well have scarred you, but its antiquity may cause the schools to assume that you’re evading the question. Similarly, failed relationships are too personal and common.

“What’s the greatest obstacle you’ve overcome (personally or professionally)? How has overcoming this obstacle prepared you to achieve success now and in the future?” (Kellogg)

“What’s the greatest obstacle you’ve overcome (personally or professionally)? How has overcoming this obstacle prepared you to achieve success now and in the future?” (Kellogg)

“Describe a time when you pushed yourself beyond your comfort zone.” (MIT Sloan)

“Describe a time when you pushed yourself beyond your comfort zone.” (MIT Sloan)

“Share your thought process as you encountered a challenging work situation or complex problem. What did you learn about yourself?” (Virginia Darden)

“Share your thought process as you encountered a challenging work situation or complex problem. What did you learn about yourself?” (Virginia Darden)

“I started to think differently when…” (Chicago Booth)

“I started to think differently when…” (Chicago Booth)

In a sense, growth and learning essays seek the same thing as failure or mistake essays but from a different angle: evidence that you have experienced challenge in your life and have the self-knowledge to analyze and grow from it. Rather than invite evasion and prevarication by asking you about a failure, these essay questions take a gentler, more positive approach to get at the same information: your ability to change once you realize things are not as they ought to be.

As a general rule, growth, challenge, or learning essays should have three sections. The first is the description of the context: the initiating “feedback” event itself or the moment when you received criticism (Tuck), realized you faced an opportunity or challenge (Wharton), experienced frustration or disappointment (Harvard), or learned that your “theory” (or starting assumption) was invalid (Columbia).

The second is the analysis: your personal acknowledgment of a growth opportunity—your frank, direct analysis and confirmation of your need to act on the feedback, reject the opportunity, respond positively to the disappointment or challenge, or revise your initial assumption or theory. This should be the essay’s pivot point and most personal moment, where you set the describing and positioning aside and get real about your internal response to the self-learning moment.

The third section is your growth-in-action moment: the concrete steps you took to heed the criticism; build on or move past the disappointment, challenge, or rejected opportunity; or apply your newly revised “theory” in the real world.

Don’t expect the power of the moment or the feedback to speak for itself. Admissions committees want you to walk them through the lessons and subsequent life changes. As much as possible, let the reader inside. Candidly describe your emotions in response to the event and your thought processes while coming to grips with it and moving on from it. A good growth or learning essay will convince the admissions committee that you are an evolving, self- and world-aware person rather than a superficial achievement engine perpetually cocked to fire.

This section of sample essays contains fifteen examples: five self-revelation essays (written by applicants accepted by Harvard, Stanford, Wharton, Columbia, and Tuck), two self-evaluation essays (whose authors were admitted by Harvard and Kellogg), three creative or multimedia essays (from admitted applicants at NYU and Chicago), three failure examples (written by successful applicants at Harvard, Columbia, and Wharton), and two growth or challenge sample essays (whose authors were admitted by Columbia and Tuck).

What do you wish the MBA Admissions Board had asked you?

“What does it means to be a Pinball Arbitrage Wizard?” [←Enticingly offbeat lead grabs reader’s interest by the lapels.]

In one of my mother’s first recordings of me as a child, I can be heard belting out The Who’s “Pinball Wizard.” I still have fond memories of pinball time I shared with my father at a local arcade. When my wife, Ellen, and I began dating, we would often cap a date with a few rounds of Earthshaker at the local Golfland. All these memories seemed threatened by the harsh reality of my accident, [← Jack refers to a life-changing accident he describes in another Harvard essay.] until Ellen suggested that we purchase an Earthshaker as a form of physical therapy. We enjoyed the game so much that a year later we added a second to our collection. By then, I had insinuated myself into the online pinball community, and learned how to repair machines, locate parts, and participate in auctions. Not content with simply battling my fellow collectors for machines at the monthly auction, I scoured the globe via the Internet for deals. Finding two in New Zealand, I bought them for $1500 and sold them three months later for over $3700. Encouraged, I began my search for larger quantities. [←Jack’s obvious passion for his unusual hobby sends just the right message to admissions readers.]

I focused on Europe, where pinball machines are not considered collectibles. Using a crude, but effective, text translator, I established relationships with three German suppliers who were willing to send twenty-foot cargo containers to the United States. [←Jack’s resourcefulness and thoroughness are obvious, but his essay’s insights into an industry the adcoms are unlikely to know also win him points→] In exchange for strategic benefits (free circuit-board repair, a secure warehouse, discount parts), I partnered with a local amusement game company and agreed to split each container load and cost. I handled all aspects of the transaction, and negotiated the machine assortment, price, shipping, and wire transfer of funds. Soon, we were receiving a container every three months, and I couldn’t refurbish the games fast enough to meet demand! On an average transaction, I would more than double my $15,000 investment. [←Not just an obsessed hobbyist, Jack’s a good businessman as well.]

In 2001, my pinball importing adventure came to an end. Competition had driven prices up, and dwindling supply only yielded battered, overplayed machines. It was an exciting time while it lasted, and it taught me valuable lessons about enterprise, building a business, and arbitrage. Most of all, having my pick from each shipment helped me expand my collection, which I am proud to say now stands at ten of the most sought-after machines ever made. Now, if I can just figure out how to apply the principles of arbitrage to Texas Hold’em Poker! [←The closing line sustains the engaging and humorous tone that distinguishes the entire essay.]

What matters most to you, and why?

Color: A phenomenon of light that enables one to differentiate otherwise identical objects. (Merriam-Webster’s). The most important thing for me is to find in every person their color, to help develop that color to its full luminosity.

[←The dictionary definition introduction is not original, but where Lena starts to go with it pulls the reader in.]

My adopted sister, Hannah, three years younger than me, first opened my eyes to color in this context. In 2000, my parents volunteered in Zambia and, becoming her guardians, helped her to start a new life in Germany. German society, however, turned a cold shoulder to Hannah. I was appalled to find that classmates teased her, and parents of her friends forbade their children from hanging around Hannah because she came from a poor country and could not speak German. She eventually quit school and fell into despair. [The second paragraph establishes Lena’s distinctive cultural background, and her protectiveness of her adopted sister humanizes her for the admissions committee.]

Our family cherished Hannah, but I was convinced that she could not turn around unless she cherished herself first, by understanding her core value—she needed to find her own color. [←Repeats color theme to sustain essay’s unity.] One day when traveling to Dresden, I noticed Hannah latched onto my camera. For the rest of the day Hannah continuously shot pictures of Turkish Gastarbeiter, whom German society also discriminates against. I noticed the glow in Hannah’s pictures, which showed hurting people in a warm light. This otherwise nearly suicidal girl found her purpose behind the lens of a camera.

I scrounged my money together and bought Hannah a used Leica. Deeply touched by Hannah’s growing self-confidence through photography, I committed myself to showing her works to her classmates and their parents to banish their prejudice. I posted her works in subway stations and on high school homepages. In 2005, I was thrilled when Hannah was awarded the Kulturrat (German Cultural Council) Award in a national cultural contest for students, becoming the pride of our town. She is currently working as a photographer in an artist-in-residence program in Istanbul. [Lena’s efforts for her sister ensure the reader’s empathetic identification with her unfolding story.]

What would have happened to Hannah had I not bought her that camera eight years ago? My experience with her changed my understanding of myself, making me realize I can make a difference in another person’s life. The fulfillment I discovered influenced me to continue to discover colors in diverse ways, including mine. [←The essay’s pivot: repeats color theme to show that the lesson Lena learned in helping change her sister’s life changed her own as well.]

My situation resembled Hannah’s, when before college parents, teachers, and friends asked me, “Do you really plan to give up Technische Universität München after passing through the Abitur?” Through my eighteen years of life, I had thought of nothing but becoming an engineer, following my father, a celebrated inventor and entrepreneur. I wanted to be adored by my parents and was terrified that doing otherwise would disappoint them.

And yet as I helped Hannah find and inhabit her color, something in me started to change, to open. I shed my own prejudices about the marginalized in my society. And I looked at myself. I had learned in math class the hypothesis that elements in a set are all equal, and realized that our society does not mirror the ideals of mathematics’ equality, with some living in discomfort. I understood that my path was not engineering, but changing society through social work. [←Business schools respond positively to candid and self-knowing admissions of one’s capacity to change.]

Finding is one thing; inhabiting my color was long and treacherous. [←Lena’s deft phrasing—“inhabiting my color”—shows a sense of writerly style that further individuates her essay.] My gymnasium, renowned for sending students to technical universities, strongly resisted my transfer to liberal arts. It was uncomfortable for those around me, even my parents, to accept my leaving engineering. To apply for the social sciences, I studied sociology and science, and on my own studied economics, politics, and history, sleeping four hours a day, and even studying while eating. Despite no one supporting me, I believed in myself. I took the entrance exams, placing in the top 0.5%, and was accepted into Heidelberg University’s Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences. I was the very first female student specializing in science at my gymnasium to enter Heidelberg’s Economics and Social Sciences faculty. When these results were published, my parents hugged me tightly and congratulated me on my new path.

Looking back, I realize that changing programs was the first step towards illuminating my own color, enabling me to take the next steps with assurance.

Having learned the importance of eliminating fear and facing what I really want to be, I now consider it a mission to help others find their own colors. I have advised students facing such struggles at Heidelberg University’s career placement center and supported McKinsey consultants by organizing a McKinsey careers conference. I will continuously commit myself to finding diamonds in muddy ground. [←Lena’s essay skillfully uses the color metaphor to trace her personal redirection and the expansion of her focus on personal change from her sister, to herself, to others in the wider world.]

Is there anything about your background or experience that you feel you have not had the opportunity to share with the Admissions Committee in your application? If yes, please explain.

Have you ever had a Greek child named after you? [Leading the essay with question directed at the reader commands attention.] I hadn’t either, so at first I was overwhelmed by the honor that Stefano—my college roommate, best friend, and basically brother—extended to me in naming his child “Christos David Kounelis.” How I, a 25-year-old American, managed to convince Stefano to break his family’s age-old tradition and use my name rather than Stefano’s father’s as Christos’s middle name is, even to me, a strange and fascinating story.

Stefano arrived early one morning in my freshman year after travelling all day from a small town in Southern Greece I’d never heard of. For the next six months, we shared a room the size of a shoe-box and didn’t speak the same language. But quickly we found a common interest: The Jerry Springer Show. Then one night, Stefano’s English clicked and I discovered that he’s absolutely hilarious. I learned that he comes from a long line of aristocrats and resides in a large villa overlooking the Aegean Sea. So I obviously was ecstatic when he invited me to stay at his home, Amorgos, the next summer. [Pithy details of dawning friendship ensure the reader’s empathy and interest.]

Amorgos is a true paradise. It’s the sister Island of Naxos but much more authentic in that it’s not flooded with tourists. When I first arrived there that summer, I was the classic disgusting American: baggy clothes, poor manners, and an impatient guzzler of frappé (Greeks savor them slowly). Despite my rough edges the town welcomed me warmly. Stefano introduced me to all his friends, who quickly became great friends of mine. The people of Amorgos were so wonderful I wanted to be a part of their world! So each summer for the past 10 years I’ve traveled to Amorgos, accumulating so many great experiences I could fill a book. For example, there’s “To trelo dēpno” (the crazy dinner), a monthly ritual in which the guys have an evening of food and wine but no girlfriends, and fill the air with songs like “Stekoumeni pēseni” (bottoms up). Or my hilarious lunches with Stefano’s mother, who I incorrectly nicknamed “metera olis tis elladas” (“mother of all Greece”), who, hearing that I’m vegetarian, served me squid, clams, and prawns because they’re clearly not meat! [←David’s cultural insights and obvious passion for Greece lift this paragraph above the ordinary.]

These rich experiences made me feel part of Amorgos. In return for Amorgos’s hospitality the least I could do was open my home to it. So each winter a different Amorgoan spends two months with me in America. Out of our friendship and mutual curiosity, we have created our own de facto exchange program.

I wish I could say I created a wonderful charity for orphaned Amorgoans or helped its poor fishermen improve their business skills, but it wouldn’t be true. But what I have done on Amorgos is something I’m just as proud of. I’ve created a real Greek family for myself at whose center is my best friend—my “adelfós”—Stefano. When his first son was born Stefano wanted me to be the godfather, but since I live too far away he decided to break a tradition and make Christos’s middle name “David” rather than Nikos, after Stefano’s dad. It’s an honor I’m a little embarrassed about, because I can never be worthy, but it also makes me extremely proud. [←Touching ending ends the essay on warm “human interest” note: readers feel they know David as a person now.]

Is there any further information that you wish to provide to the Admissions Committee?

While I am very proud of my academic career and personal growth, I grant that my background is not typical. I am using this essay to address any question marks that my academic and personal history may raise. [Though Leopoldo used this self-revelation story for Columbia’s optional essay, it was his core personal story that appeared in one form or another in every application he submitted (he also gained admission to Wharton.)]

Growing up in Tallahassee, Florida, I lived in daily fear of my alcoholic and abusive father. As the only son, I protected my mother and two sisters from my father’s rage by taking the brunt of his anger on myself. This painful environment led to a struggle with depression that evolved, during my early teens, into alcohol and marijuana use as a form of escape. The cliché about liquor and pot leading to harder substances is true, and by my sophomore year in high school I was rarely attending class. My only priorities were drugs, alcohol, and the punk rock music that gave me a way of understanding my life. [Gripping story holds reader’s interest. How will this tragedy turn out?]

After countless fights with my family I eventually left home at the age of 16. It was more than two years before I saw any family member again. While most kids my age were taking Advanced Placement classes and dreaming of admission to prestigious universities, I was living on friends’ couches with no possessions but my skateboard and the contents of my backpack. With no financial support, I simply struggled to survive and attended high school only occasionally, more to see friends than to attend class. If not for the grace and support of the Assistant Principal, Mark Posner, I am certain I would not have graduated. [This third paragraph takes Leopoldo’s tale to new lows, bringing us to the pivot point.→]