The St. Mark’s Baths, a four-story brownstone at no. 6 St. Marks almost indistinguishable from the surrounding buildings except for its fairly grand first-floor dimensions, had been a disreputable bathhouse and rooming house for generations of locals lacking hot water or a permanent residence. When the Baths, an unofficial homosexual meeting spot for decades, went formally gay in 1979, it remained modest on the outside. A black door read “The New St. Marks” in simple white block letters on one side and “Six St. Marks Place” on the other. But inside, the space was a pornographic palace.

Owner Bruce Mailman* spared no expense redecorating the “New St. Mark’s Baths”—a gay pilgrimage spot nicknamed “Our Queen of the Vapors”—in primary colors with spotlights and elaborate tile work. In one pool room on the ground floor, walls were lined with sparkling white tiles accented with pale green ones. Men could rent a locker for seven dollars for eight hours, or a private room for a few dollars more. Then they could cruise the various rooms for partners. In his poem “The St. Mark’s Baths,” Tom Savage writes about trying to find the men who are “not too old to be repulsive; not too young to be conceited.” “Guys would be lined up around the block to get in,” recalls St. Mark’s Bookshop’s Terry McCoy—even celebrities. One neighbor recalls seeing the dancer Rudolph Nureyev “duck-footing in there.” Different rooms catered to different sexual proclivities. On the top floor: “You could pretend you were in jail, and of course the jailer was for sale,” says one former patron. “You could have sex in the cab of a truck!” says another, his voice turning wistful. “I never knew how they got that truck cab up there.”

The narrator of the novel Eighty-Sixed goes there on New Year’s Eve 1980. “I managed to come at the stroke of midnight with my third companion of the night,” he says. “I took the subway home at two in the morning, the car littered with beer cans and streamers.”

Ad for the New St. Mark’s Baths, ca. 1979. Reprinted with permission of Boris Vallejo, illustrator.

According to gay nightlife impresario Scott Ewalt, one short, hairy, older regular at the Baths was always naked except for a leather mask over his face. People joked that the masked man was New York City’s bachelor mayor Ed Koch.

In 1969, less than a mile to the west of St. Marks, a group of gay-bar patrons at the Stonewall Inn defied a police raid. The gesture spurred a protracted battle between the gay community and law enforcement that’s often hailed as the start of the gay rights movement. Throughout the sixties, gay bashing had been a regular occurrence even in the supposedly progressive East Village. A reporter profiling transgender Andy Warhol superstar Jackie Curtis wrote, “Walking down St. Mark’s Place at midnight with Jackie offers a revelation about the long-haired political activists who regard themselves as street guerillas of the new people’s revolution. They jeer at and threaten Jackie with the backlash zeal of a bunch of uptight goons.” Curtis strode through the mob, chiffon scarf waving like a banner, “with the confidence of one who knows that she is riding the wave of the future.”

Novelist Perry Brass found similar homophobia among supposedly peace-and-lovey hippies at the St. Mark’s Free Clinic (no. 44), which treated “hip people problems,” like bad acid trips and sexually transmitted diseases. “I was dating this guy who’s still a friend of mine—it’s been forty-five years—and he told me that he felt he had gonorrhea. The two of us went to the clinic. The doctor who came in to treat us went into a rant about how homosexuals were like promiscuous women. He said, ‘You use your asshole like women use their vaginas! You don’t know what’s been in there before you. You have to stop doing this!’ Here was this guy who was in early middle age with a ponytail, thinking he was so hip. I thought he was a jerk.”

As the seventies went on, gay sexuality thrived more openly on the street. In his 1978 novel about gay nightlife, Dancer from the Dance, set largely on St. Marks Place, Andrew Holleran wrote that instead of Poles and hippies, “St. Mark’s Place now belongs to hair stylists, pimps, and dealers in secondhand clothing.” In the novel, Holleran depicts a young gay heartthrob named Malone who lives above the former Electric Circus. Each night, Malone (a man, though he sometimes takes a feminine pronoun in the book) changes clothes countless times before having a meal and then, “just as the Polish barbers who stand all evening by the stoop are turning back to go upstairs to bed, she [Malone] slips out of her hovel—for the queen lives among ruins; she lives only to dance—and is astride the night, on the street, that ecstatic river . . . down into the dim, hot subway, where she checks the men’s room.”

In the book, Malone and his friends hook up throughout the city, cruising clubs, bathhouses like the New St. Mark’s Baths, and outdoor areas like Stuyvesant Park a few blocks north on Second Avenue and Fifteenth Street. The primary consequences are heartbreak and exhaustion. Journalist Carl Swanson (who lives on St. Marks between First Avenue and Avenue A) calls the book “Gatsby for the cusp-of-AIDS era.”

Many of those who indulged at the Baths were also part of the new East Village art scene, a do-it-yourself movement that Craig Owens nicknamed “Puerilism” in a 1984 essay. Storefront galleries and improvised performance spaces were filled with the work of artists like photographer Nan Goldin (her subjects: those who stayed up late, Peter Schjeldahl said, “to fit into each day its maximum number of mistakes”) and performance artist Karen Finley.

With the Dom, Balloon Farm, Electric Circus, and Fillmore East gone, young artists created their own funhouse-mirror versions, acting out their fantasies of what St. Marks Place once was and could be again. The art scene became a playground modeled on Andy Warhol’s St. Marks Place and peopled by artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, Joey Arias, Wendy Wild, John Sex, and Keith Haring.

Gallery owner James Fuentes was born on the Lower East Side before moving to the Bronx. Fuentes, who now runs his own gallery on Delancey Street, liked the DIY ethos of the eighties galleries: “They were taking matters into their own hands. They were rejecting the minimal and conceptual art of the sixties and seventies. There was a very strong feeling of activism and socially engaged work. It was an art world pre-commerce, before the boom time when Wall Street guys were buying. This was a sliver of a moment of social awareness.” The scene rallied in opposition to President Reagan and the conservative America he represented. East Village artists identified with one another in opposition to the rest of the country—a land that in their eyes was full of homophobes willing to let New Yorkers die by the thousand.

Keith Haring grew up in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, as the oldest of four children. His mother was a housewife and his father worked for AT&T. Haring studied at New York’s School of Visual Arts from 1978 to 1980. He drew TVs, dancing people, penises—all of them in a distinctive, radiant style; and he drew them everywhere—on subway cars, building walls, posters, discarded furniture, and on the singer Grace Jones’s body. He campaigned against drugs—his “Crack Is Wack” mural survives on a handball court along the Harlem River Drive—and for gay acceptance.

Mostly he was known for his prolific images of cartoon babies. “The reason that the ‘baby’ has become my logo or signature,” Haring once explained, “is that it is the purest and most positive experience of human existence. . . . The feeling of holding a baby and rocking and singing them to sleep is one of the most satisfying feelings I have ever felt.”

Though a relatively new arrival, Haring felt at home in the East Village, which had evolved an identity scruffier and scrappier than the comparatively wealthy, clean-cut, and muscle-bound gay scenes in the West Village and Chelsea. Haring admired William S. Burroughs and loved that the author of Naked Lunch had lived for a time on St. Marks Place at the Valencia (no. 2). He defended the East Village as a special place with an important history. In 1980, Haring used a stencil to spray-paint the phrase “Clones Go Home” on the western borders of the East Village. He hoped to scare away those whom he felt weren’t true East Villagers. (Some called it apt when, in 2015, the foot of a large green Keith Haring sculpture installed at St. Marks Place and Third Avenue was accused of clonking a texting NYU student in the head.) “We felt the East Village was a different kind of community,” he said, “which we didn’t want too cleaned up in the way of the West Village.” Note that he was a white, middle-class college student from the suburbs who had been in New York for just two years when he decided the East Village’s integrity was his to protect.

Haring felt at home at Club 57, a punk-art venue at no. 57 inspired by Dada, Godard movies, exploitation films, and vaudeville. Entrance fees were two to five dollars for theme nights like “Putt-Putt Reggae,” “A Night at the Opry,” model-plane making, lady wrestling, and a prom for people who didn’t go to their own proms. The mistress of ceremonies, actress Ann Magnuson, lived on St. Marks and Avenue A from 1979 to 2003 after having fallen in love with St. Marks Place the first time she saw Tish and Snooky’s Manic Panic. “They had a poster of Farrah Fawcett in the window,” Magnuson says. “It had been defaced in a hilarious way. I think she had a paper bag on her head. I thought, ‘I want to know those people.’”

Haring hosted a “Club 57 Invitational,” at which everyone was welcome to make art. “[The Invitational] was typical of the scene,” says Magnuson, “inclusive, encouraging, and open-minded.” Nick Zedd’s favorite regular event was “Monster Movie Night”: every Tuesday they would show the worst monster movie they could find. Magnuson started the “Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Lower East Side,” her take on the Junior League to which her mother had belonged. “It was part of a sincere desire to bond with the gals of the scene,” she says.

One night, a poet who goes by the name Sparrow (and who a decade later would run for president, campaigning in front of Gem Spa with signs like, “Don’t eat Pez; Sparrow for Prez” and “Sparrow, fly to the Oval Office”) walked into Club 57 just as a performance of The Wizard of Oz was concluding. Holly Woodlawn, the transgender Warhol actress whom Lou Reed immortalized in the song “Walk on the Wild Side,” stood center stage. Surrounding her, Sparrow says, were “the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion, and a few Munchkins singing ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow.’ It was your basic high-school production–plus-transvestite. As Holly pronounced those sacred words: ‘And the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true,’ we all felt beacons of hope.”

On “Elvis Memorial” night, someone (Magnuson thinks it was one of the “juvenile delinquents” from the home down the street) sprayed beer on the air conditioner, causing a short that started a small fire and sent dozens of people dressed as Elvis streaming out onto St. Marks Place. “Everyone started getting on the fire trucks in their rockabilly outfits, singing and doing Elvis impersonations,” recalls Magnuson. “When the police arrived it wasn’t as much fun, but the firemen seemed to enjoy it.”

The mood at Club 57 and related clubs around the Lower East Side in those days was highly sexual. Artist Kenny Scharf has said that sometimes he’d look around and realize he’d slept with everyone in the room. At the Lower East Side space ABC No Rio, naked performers once chased the audience down the street while flinging horse manure at them. John Bernd’s tighty whitey–clad Go-Go Boys danced for raucous crowds at a performance space in the former elementary school P.S. 122.

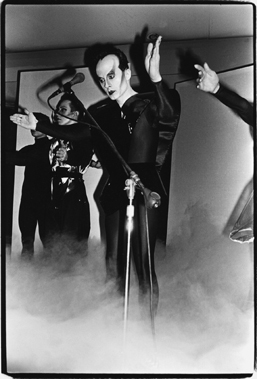

Club 57’s resident opera-singing performance artist Klaus Nomi lived at no. 103. Kenny Scharf lived at the back of 418 East Ninth Street, and could hear Nomi’s voice carry through the courtyard when he practiced. Nomi was, in the words of former St. Marks resident Mark Howell, “a little guy with a mystery and beauty about him, a ghostlike presence in his Kabuki makeup.” Howell says he always loved seeing him “the next morning at the grocery store with no makeup on and his hair plastered down.”

It hit this close-knit community especially hard when several people on the scene, including Nomi, began to get very, very sick. “It certainly freaked the hell out of everybody,” says Magnuson. More and more artists grew weak and some began to die. Most of the stricken were gay.

Performance artist and Club 57 performer Klaus Nomi in 1980, three years before he died of AIDS. Photo by Harvey Wang.

In January 1982, the strange “gay cancer” gained a new name, GRID (“gay-related immune deficiency”). That summer, the disease was renamed “acquired immune deficiency syndrome,” or AIDS. Doctors had little information about what the disease was and exactly how it spread. Fear fed homophobia. The nightly news reinforced East Villagers’ sense that they were living on an island that the rest of the country wished could be cut loose and pushed out to sea.

New Yorkers were outraged by national apathy in the face of the plague killing their friends. Worse, they were terrified by the Reagan administration’s seeming disregard for their lives. Some in the city at that time believed that the government was on the verge of setting up internment camps for those who’d been diagnosed.

Playwright Larry Kramer held a meeting and asked half of those in attendance to stand up. “You’re all going to be dead in six months,” he said. “Now what are we going to do about it?” In March 1987, he founded the activist group ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. ACT UP held fierce “Silence = Death” marches. Another group, Gay Men’s Health Crisis, paired those dying of AIDS with “buddies” who volunteered to take care of them.

One of the most public victims of AIDS was the New Jersey–born artist David Wojnarowicz, who lived at 189 Second Avenue. A former hustler, Wojnarowicz made work largely about alienation, but he also had a sense of humor. Once the artist collected an army of East Village cockroaches, pasted little triangle ears on their heads and cotton tails on their backs, and dropped them off at an art gallery to wobble around. He called them “cock-a-bunnies.”

Tom Rauffenbart has said that the first time he met Wojnarowicz was when they had sex in the bathroom of the Bijou Theater on Third Avenue in 1985. The first words they spoke, after having sex, were about how Rauffenbart had lived in the East Village since the 1960s. “You must have seen a lot of changes,” replied Wojnarowicz.

St. Mark’s Baths worker Jay Blotcher kept a diary. “I meet my guest at the foot of the steps, bearing two towels and a cup of Lube, and take him to his personal fuck cubicle,” writes Blotcher of his first day of work, on February 25, 1983. “Sometimes a 50-cent tip, more often not. The most unattractive part amid all this glamor is cleaning the rooms. In the Age of AIDS can I really afford to handle cum-and-crap stained sheets and overturned bottles of poppers? Eight lonely hours of this dirt and darkness, and I was finished!”

Bruce Mailman struggled to be a responsible bathhouse owner in the AIDS era. He started a policy of handing out free condoms and safe-sex literature to patrons. He told the New York Times, “Am I profiting from other people’s misery? I don’t think so. I think I’m running an establishment that handles itself as well as it can under the circumstances.”

And yet, misinformation about AIDS flourished. Responding to a reader letter, downtown scene queen Cookie Mueller said in her East Village Eye column “Ask Dr. Mueller” that AIDS was nothing to worry about. “If you don’t have it now, you won’t get it,” she wrote. “By now we’ve all been in some form of contact with it. . . . Not everybody gets it, only those predisposed to it.” She herself would die from AIDS a few years later.

Klaus Nomi died of AIDS in 1983. “We didn’t know who Klaus Nomi was,” says Barbara Sibley, who followed her NYU-student sister, Widow Basquiat author Jennifer Clement, from their home in Mexico to no. 13, and today runs the Mexican restaurant La Palapa at no. 77. “To us then he was just the creepy guy who was dying next door. That’s when you didn’t know what AIDS was yet. It was pure Russian roulette. I was flirting with people who had AIDS then. All dead.”

Keith Haring at an ACT UP rally protesting Mayor Ed Koch’s inactivity on AIDS, ca. 1989. Photo by John Penley. Reprinted courtesy NYU’s Tamiment Labor Archive.

When Wojnarowicz died of AIDS at home on Second Avenue and Twelfth Street at the age of thirty-seven, an ACT UP affiliate group called The Marys staged the first political funeral of the AIDS crisis. The procession started at Wojnarowicz’s loft and wound east through the East Village to Avenue A, then west to Cooper Union. Neighbors joined in until there were hundreds marching in the parade. They showed slides, including one of a dead body on the White House steps, and ended by burning an American flag with Wojnarowicz’s name on it and throwing flowers into the pyre. (A more subdued memorial took place at St. Mark’s Church that September.) When one member of The Marys died, he was given an open-casket wake in Tompkins Square Park.

In a way, Magnuson says, the anxiety around AIDS “made everyone burn brighter. People worked even more furiously. Certainly Keith Haring did. He was going gangbusters until the end.” Haring died on February 16, 1990, at the age of thirty-one.

Some artists raged against the specter of death with glitter and posturing. Lavishly costumed performance artist Leigh Bowery was resplendent in blinking light bulbs, head-to-toe makeup, wigs, elaborate body stockings, and huge heels. The British raconteur Quentin Crisp (who moved to Fourth Street and Second Avenue at the age of seventy-two) walked through seas of punk kids with safety pins stuck in their jackets looking aristocratic in his lipstick, silk scarf, and jaunty hat.

Meanwhile, the East Village gay community’s sparkly nightlife, a complex and defiant response to AIDS, was being packaged for sale around the country, minus the anger. Promoter Scott Ewalt says New York City’s gay nightlife was trying to overcompensate for the horror of AIDS, but that the aesthetic was co-opted for mass culture without preserving any of that original awareness and energy.

“Madonna is the worst thing to ever come out of the East Village,” says Ewalt. “You had Cristina, Debbie Harry, Phoebe Legere, and Cherie Currie from The Runaways playing with sex in a cynical type of way, and then Madonna just came along like a playground brat and took the best elements from those people and lost the irony along the way. It wasn’t like she was mimicking a pop tart. She was a pop tart. When the eighties went mainstream with Madonna, it lost that edge and just became about rubber bracelets and lacquered bangs.”

In 1983, Madonna went platinum. Two years later, by order of the New York City Health Department, the New St. Mark’s Baths was shut down for good. The East Village art scene effectively ended with the stock market crash of 1987, which was also the year Warhol died. A few years after that, Baths owner Bruce Mailman died of AIDS. At his Astor Place Theatre memorial service, a slide projector clicked through images of Mailman and his friends from the days before any of them had become sick—a time that suddenly seemed very long ago.

* Mailman also owned popular gay disco The Saint, which opened in the old Fillmore East in 1980 with a 4,800-square-foot dance floor under a ceiling filled with a planetarium-like star projection. Men met on the dance floor and then repaired to the balcony to have sex. Early in the AIDS epidemic, some called the illness “Saint’s disease” because many of those infected were regulars at the club. (Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On [New York: Macmillan, 2007], p. 149; “Rich Wandel: A Brief History of the Saint,” OutHistory.org; David W. Dunlap, “As Disco Faces Razing, Gay Alumni Share Memories,” New York Times, August 21, 1995.)