There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road,

I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.

Willa Cather, “My Antonia”

Montana Ghosts and Pioneer Spirits: My Dad’s Cowboy Relatives

Every summer while I was growing up, my family would make the twelve- to fourteen-hour trip out west to visit my grandma Mae and grandpa Bernard Morgan. My dad grew up on the eastern prairie of Montana, sometimes living in the country and sometimes in the small town of Baker, depending on whether Grandpa Morgan was farming or doing in-town work, like repairing vehicles at a service garage or selling farm machinery. My grandparents moved to a tiny western North Dakota border town after my dad had left for college and lived there for the rest of their lives, so that’s the place that is familiar to me. We would visit all the Montana relatives when we were there, of course, going back and forth between everyone’s places.

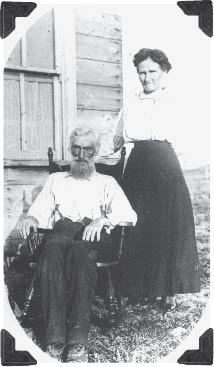

B. T. and Tiny Gramma in front of their homestead at the South Farm, Montana, circa 1921.

I loved the big sky of Montana, the buttes, and the stark landscape that went on as far as the eye could see, occasionally broken up by tall cottonwood trees or small, crooked rivers and creeks. Montana had fields and pastures, but they didn’t look like the ones back in Minnesota. Towns and houses were few and far between. A railroad track ran along the highway for hours and hours, coming right through Grandma and Grandpa’s town before heading farther west through Montana, Idaho, and Washington State, all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

One of my favorite North Dakota memories is of my parents waking us kids up in the early hours of the morning as we drove past my Uncle Jim’s place in the country, which meant we’d be arriving at Grandma and Grandpa Morgan’s house a few minutes later. (When we were little, we left Minnesota at suppertime and my dad drove all night, so we kids would be asleep for most of the trip. This was in the days before car seats, so my mom would hold whoever was the baby on her lap the entire time.) When we got to town, we’d turn left at the main intersection and go down a few blocks to my grandparents’ house at the end of town.

Because we generally saw our Montana grandparents only once a year, we kids were always shy when we first arrived. Grandpa Morgan was a hardworking and laconic Montana farmer, but as a grandpa he was a teddy bear, a kind man who gave bear hugs. Whenever we saw our grandpa, he’d reach out with a smile and say, “Give us a love,” and then he’d give us a big hug. We’d feel much more comfortable after a hug and kiss from him. Grandma Morgan was a schoolteacher who still taught classes in the 1960s and ’70s. The school at which she taught was so small, she usually taught two entire grades at a time; one year, she had only nine kids in her class. Grandma Morgan was kind of a cowgirl grandma—sometimes she said damn and once she saved me and my siblings and cousins from a big rattlesnake that had slithered under the front porch. (When she came out to take a look at it, she told us it was actually a bull snake, but to make us feel better, she said bull snakes and rattlers looked a lot alike.) Grandma Morgan also had an affectionate side. She’d say, “Guess what time it is?” And, since she had taught us the answer, we would reply, “Half-past kissing time—time to kiss again!”

When we visited our Montana relatives, we did cowboy things like going to the Fourth of July rodeo in town or watching from outside the corral as our grandpa, my dad, and uncles branded cows. Even my aunt Sister, who was a nurse, was part of the branding process, giving each cow an antibiotic shot. Sister, who is also a nun in the Catholic order Sisters of the Charity of Leavenworth, or SCL, wore a big apron over her black dress and a simple white veil for the occasion.

Grandma and Grandpa Morgan’s house had lots of interesting places to explore and things to do. For a while, they had an antique player piano, and I remember putting a musty paper roll in the piano and pretending to play “Winchester Cathedral” over and over. We also loved looking at the sparkly and colorful costume jewelry that my grandma kept on her dressing table. My mom had a pair of earrings made from real rattlesnake tails that my dad had made for her when they were first married, but my grandma apparently didn’t own a pair herself, even though she lived in rattlesnake country.

My grandparents’ house had a spooky basement with a steep and narrow enclosed staircase. The rise behind the third or fourth step was missing, creating a black hole that you had to walk in front of each time you went into the old basement, which we didn’t do very often. The house was heated with an “octopus” furnace, a huge, loud monster that was intimidating even when it wasn’t running. Outside, right next to the house, was an empty cistern about twelve feet deep and fifteen feet in diameter. We were told to be careful around it, but I do remember one of my cousins goofing around and falling in. He wasn’t hurt (it was made of cement, but my grandpa kept a deep pile of leaves in the bottom just in case someone fell in), and it definitely earned my cousin extra coolness points with the rest of us.

Grandpa Morgan, as a child, had lived in a homestead shack in South Dakota, just like Laura Ingalls Wilder. They had to set their bed frame posts in kerosene to keep the bed bugs from climbing up. My dad said the bed bugs outsmarted them by climbing up to the ceiling and dropping into the beds. Grandma Morgan, who had grown up in the small Minnesota town that my grandma and grandpa Haraldson had moved to in the late 1930s, moved out to Montana as a young woman to teach at a one-room country school. She roomed at my great-grandparents’ house, which is how she and my grandpa met and fell in love. It took my grandpa a while to propose, and when he finally asked my grandma to marry him, it was on April Fool’s Day. My grandpa and his brothers had a reputation for pulling pranks, and it took my grandma a week to decide that the proposal was sincere and he wasn’t pulling her leg. When Grandma and Grandpa Morgan first got married in 1930, they lived in an abandoned homestead shack in eastern Montana. In time, a bigger and better homestead shack was abandoned, and they moved into that.

Grandpa Morgan had a strong sense of intuition that was described in our family as Grandpa just “knowing things.” He didn’t really talk about it; it was just part of his life. My grandpa wasn’t particularly superstitious or religious—he was just “in tune.” Grandpa Morgan, who wasn’t Catholic, didn’t go to church until he was older. My aunt Sister said that when they were growing up, Grandma Morgan made them say a prayer for my grandpa’s conversion to Catholicism every Good Friday between 1 and 3 pm. Apparently, the prayers worked, because according to my dad:

Grandpa was baptized in about 1947 or ’48 by Father Ciabattone, who was the Italian priest in Baker for many years. As Father C. got older, he was not able to drive, so my folks volunteered to drive him to his mission churches—Ekalaka, Plevna, Mildred, Webster, and others. The driver was generally me, as I had a license—Larry did not have his license yet—it was not proper for ladies to drive priests around, I guess. So when I couldn’t or wouldn’t drive, it was up to my dad. My dad had a lot of respect for Father C., and Father C. thought my dad was probably the best Christian he ever met, and the two got along great. These trips were half-day ventures and provided a lot of time for discussion. When Father C. finally retired, he was going back to Italy. He told my dad he had one last favor he would like to ask before he went, and that would be to baptize him, so my dad agreed. From then on, Grandpa was a regular churchgoer, probably more so than any of the rest of us. Prior to this, he seldom if ever went to church except for his mother’s funeral.

My dad also told me the story of how my grandparents were out driving on the highway one day. They waved as they passed their neighbor, who was in his vehicle going the opposite way. After a few minutes of traveling, my grandpa said, “We have to turn around.” He knew that the neighbor they had just passed had been in an accident and needed help. My grandparents turned around and drove the way they had come and found the neighbor had gone into the ditch, which was really steep. They helped him get his car back on the road and went on their way.

My uncle Jim said that when he was a teenager, my grandpa somehow knew that he had skipped classes to go to a big two-day music festival, Zip to Zap, in the little town of Zap. The outdoor concert was North Dakota’s version of Woodstock and took place at the same time. Jim said he and his buddies were picked up at the concert and were some of the first concertgoers brought to jail in Bismarck for underage drinking. At the jail, Jim said the police officers took away their beer and told them to go home.

Jim, who still lives in western North Dakota, is my dad’s youngest brother. Jim, a former chief of police, is a member of the volunteer fire department (made up of, according to Jim, “however many people show up”) and has a repair shop where he fixes just about any kind of vehicle that breaks down (see photo gallery). He also raises sheep. His wife, Vernice, runs the town café.

Jim is a great storyteller who, among other things, owned a pet monkey that he became a lot less fond of when he discovered it peeing on his pancake one day. Jim was the original owner of our albino horse Trigger. Jim had gotten Trigger in the 1950s and used to do tricks with him, such as running up behind Trigger and jumping on his back while Trigger stood still (and probably kept eating grass). Jim gave Trigger to my brother Thomas sometime in the sixties. We kept Trigger until the mid-seventies, when Jim and Vernice had kids of their own. Then Thomas gave Trigger back to Jim so his kids could enjoy him, too. After bringing a lot of happiness to three generations of kids in our family, Trigger died peacefully out in his home turf of North Dakota.

Both my uncle Jim and his wife, Vernice, had near-death experiences. Vernice had an aneurysm, and it was touch and go for a while. Along with all of us in the family, their entire cmmunity was praying for her safe recovery. Jim said that when someone needs help, the people in their small town pull together and everyone pitches in. Vernice, who made a complete recovery, does not have any memory of seeing angels or lights or even of being in the hospital, although she was there for two weeks.

Jim had a near-death experience when he was electrocuted while working at a construction site. A boom hit a power line, and Jim heard a hum like the sound a transformer makes. He realized what was happening and yelled at the guy next to him to get away, so he wouldn’t get electrocuted too. Jim said the last thing he remembers before losing consciousness was hoping that someone at the job site knew CPR. He saw a bright light at the end of a tunnel, and “a bunch” of hooded beings in white robes at the far end of the tunnel. Then he heard a voice say, “He’s not ready. Send him back.” And Jim said just like that, he got sent back like an undercooked steak at a restaurant. The next thing he knew, a big, burly guy was “shaking the sh** out” of him. Jim asked his coworkers which one of them had given him CPR. One of the guys answered, “No one, ’cause we thought you were dead.”

Jim told them thanks a lot and called them a cuss word. (He later learned from a doctor that the force with which he hit the ground probably restarted his heart.) But he had other things to deal with at that moment, because the electrical charge had blown out through the bottom of his foot, and once he got his boot off, he discovered his sock was still smoldering. Jim has not experienced any of the common aftereffects of a near-death experience such as clairvoyance or healing abilities, but he was told by an energy healer (who didn’t know anything about him or his life) that his polarities were reversed.

When I was a teenager, my grandpa Morgan got sick with ulcers and lymphoma. He had already beaten cancer once before in his life, back in the 1930s, when he had gotten lip cancer from smoking. In those days, cigarettes had no filters. My grandpa worked as a mechanic at the time and his hands were usually covered with grease, so instead of touching the cigarettes, he would let them dangle on his lip till they burned his mouth. My grandpa’s Montana doctor had sent him to a clinic in Savannah, Missouri, for a natural remedy for the lip cancer. The treatment consisted of a poultice being applied to my grandpa’s mouth where the tumor was, and then a bandage put over it. After three weeks or so of daily treatments, the tumor came out one day, stuck on the bandage. Although my grandpa had a notch on his lip where the tumor had been, the remedy did take care of the cancer. According to my dad:

I was about five or six at the time, and I remember my dad getting on the Greyhound bus in Baker and being gone three or four weeks. My mother and Francis R. ran the Willard store while he was gone. When Grandpa came back, he had a notch in his lower lip where a couple of teeth showed through. It eventually filled in a little, but he always had the scar.

I do not know what eventually happened to the Savannah clinic, but we would get a book from them every year for five or six years with the name, address, and type of cancer they had cured. I would always look up Dad’s name in the book. When we would talk about it in later years, Grandpa maintained the “established medical profession” shut them down because they had a cure that the “profession” could not control or profit from.

In the 1970s, when he got cancer again, my grandpa went to the Denver hospital where Sister was a nurse. He went through chemotherapy treatments in Denver and back home in Montana. He kept on working with my uncle Jim for as long as he could. My dad told me that Grandpa was the kind of man who would want to die with his boots on, working outside, doing the things he loved to do. He wouldn’t want to spend time in a hospital, even if it meant he might live a little longer. My grandma Morgan took care of Grandpa at home, in the same room where she had taken care of her dad, Great-Grandpa Schultz, a little more than a decade earlier when he died. Sister came up to stay with my grandparents when my grandpa needed more help at the end. Grandpa Morgan was in a coma for the last few weeks of his life, but on his seventy-fifth birthday, he woke up. He passed away shortly after telling my grandma he loved her.

My grandpa’s spirit paid a visit to my grandma one afternoon, a few months after he died. Grandma had lain down for a nap. She thought she heard someone come in the back door, just like my grandpa used to do. She waited to see if Uncle Jim, Aunt Vernice, or any of their kids would come in. No one did, so she thought she must have imagined the sound of the door opening. Then she felt my grandpa come in the room. He lay down on the bed beside her and put his arms around her. She wondered if she was having a vivid dream or possibly losing her mind, then she heard Grandpa say, “Don’t investigate, just appreciate”—which sounded just like something my grandpa would say.

Five years later, Grandma Morgan died. After retiring, she had started a senior citizen’s center in their small town and kept busy with church activities, substitute teaching, and spending time with Jim’s family, our other Montana relatives, and her friends. Although my grandma had lived a long life and remained independent to the end of her life, it was very sad to go to her funeral. Along with the sadness of Grandma being gone, I knew that her passing marked the end of an era. I wondered how often we would get back to Montana and spend time with our cowboy cousins. Happily for our family, we have established a tradition of coming together for big family reunions every other year or so.

The stories of my Montana and pioneer great-grandparents I heard bits and pieces of occasionally while I was growing up, but my uncle Larry collected the family histories and photographs into genealogy books that are informative and filled with great stories. My grandpa Morgan’s maternal grandparents were Tiny Gramma (whose parents were born in Scotland) and B. T. McClain, a second-generation American whose grandfather had emigrated from Ireland. Tiny Gramma had bright red hair when she was young and was only five feet tall. When she was fifteen years old and B. T. was twenty-two, he met her on his way up to Canada on a military assignment. Tiny Gramma and her family lived in northern Minnesota, and according to family lore, B. T. told Tiny Gramma (whose name was Mary Ann), “Little girl, I’ll be back to pick you up!”

B. T. did come back for Tiny Gramma after he completed his stint with the military, and they were married for fifty-four years, from 1871 to 1925, making a life of homesteading and farming. They did well enough that eventually they were able to have a state-of-the-art house built, complete with indoor plumbing fixtures, including a bathtub and a toilet. Unfortunately, the property didn’t have a septic system, so they were never able to actually use the bathroom. Their house also had carbide lights, a type of lighting that used explosive gas as a main component and was, according to my dad, “not the safest.”

Tiny Gramma was a midwife for all of her adult life. She lived to be ninety-eight years old and was spry and active to the end. Her daughter Dana carried on her mother’s natural-healing legacy, offering Denver mudpack treatments for a variety of ailments. (My dad said the mudpack treatments involved “putting warm mud in a dishtowel and wrapping it around [the ailing person’s] chest.”) B. T., who never learned to drive a car, would hitch up a horse and buggy (called a rig) even in his later years. According to my uncle Larry, at age eighty, Great-Great-Grandpa B. T. McClain “passed on in a very stately manner. He sang hymns on his deathbed, namely ‘Beulah Land,’ ‘Old Rugged Cross,’ and ‘Nearer My God to Thee.’ ”

B. T. and Tiny Gramma’s daughter Cora married my great-grandpa David Morgan. David’s father had been the third son of an Englishman. The custom in England at that time decreed that the oldest son be named Thomas, the second son be named John, and the third son, Edward. The eldest son inherited all the property, while any other sons were taught a trade, joined the military, or went to sea. Great-Grandpa David Morgan’s father was born on the feast day of St. David, so his parents broke with tradition and named him David instead of Edward, perhaps establishing a theme of independent thinking that was to mark his life. (My dad said this naming convention stopped with that generation, but I believe that the energetic pattern of the tradition may have taken a while to fade away. My dad was unaware of the tradition when my older brother Thomas was born, yet my parents chose the “first son” family name for him. Also, according to my dad, who was the oldest son of Grandma and Grandpa Morgan:

When I was about six, I wanted to change my name to Tom, without being aware of the tradition. I ordered a pencil box from an ad in the funny papers where you could have your name on the pencils, so I had three Tom Morgan pencils for a while. I didn’t want to sharpen them past the Tom Morgan name, so they lasted quite a while.

As a young man, Great-Great-Grandpa David left England to take his chances in North America. He and his family of twelve moved from Canada to a homestead in South Dakota in the late 1800s. His son, David Morgan, was a bit of a wheeler-dealer and a great conversationalist who loved to fish and apparently never really took to being a farmer. Great-Grandpa David Morgan never learned to drive an automobile, but in his midlife years, he became completely stuck on the idea of developing a perpetual motion machine. According to my uncle Larry, “He had bicycle wheels, ball bearings, belts, pulleys, and vials of mercury all over the place.” And despite the efforts of his four sons to convince him otherwise, Great-Grandpa Morgan never gave up on his dream.

When I spoke with psychic Patrick Mathews six or seven years ago, my grandpa Morgan’s spirit came through. He told Patrick to let me know the family “is all together on the other side.” I didn’t know what my grandpa was referring to, but when I asked my mom, she said there had been some sort of falling out over a family business venture in the 1930s or ’40s. In Larry’s genealogy book, I read that Tiny Gramma had sent a letter to one of the relatives saying she was sorry to hear that everything had “gone to smack.” So, it’s good to know that the feuding ended and the family is united in the spirit realm.

My grandma Mae Morgan, whose maiden name was Schultz, had grown up in the same small southern Minnesota town that my mom and her family moved to in the late 1930s. Grandma Mae’s niece Judith was my mom’s best friend in school, and that’s how my mom met my dad years later.

In 1861, my great-grandpa Schultz’s dad ran away to join the army, hitchhiking from Mankato to Fort Snelling. He was twelve years old at the time. His mom had died, and his dad had farmed out all of the kids (which basically meant sending them to earn their keep by working on neighboring farms) and become a soldier. Great-Great-Grandpa didn’t like being a farm hand, and he wanted to be with his dad. So he enlisted in the army as a drummer boy. After the war was over, the regiment went to Washington, D.C., where my great-great-grandpa saw President Lincoln in person. In a newspaper interview when he was an old man, Great-Great-Grandpa Schultz described Lincoln as someone who “appeared careworn, but who looked very kind and ready to help anyone.”

Great-Great-Grandpa Schultz must have been a little bit psychic, because he foretold who his son was going to marry. According to a story that my great-grandma Edith Schultz told her daughter Clara, when she (Great-Grandma Schultz) was seventeen, she and her cousin were playing checkers on a winter night during a blizzard. Her brother Henry came bursting in the house to tell them a team of horses had fallen on the hill at the Schultz homestead across the field. Great-Grandma Edith and her cousin put on their coats and boots and ran outside with Henry. They could see that the horses were “lathered in their struggle to regain their footing.” The Schultz family had made the move from Wisconsin to southern Minnesota, and their wagon was packed with all of their household belongings. A woman and three young girls stood shivering on the roadside, while the father and a teenage boy struggled to get the horses up. The father straightened up, brushed the icicles off his “walrus-like” moustache, and stopped to catch his breath for a moment. Then he caught sight of my great-grandma and her cousin across the road and, in the midst of the blizzard and the downed horses and the neighbors who had gathered around, he said to his son, “Willie, that black-haired girl is the one you are going to marry.” And my great-grandma Edith and William Schultz did marry nine years later. Ironically, my great-great-grandpa, the former drummer boy who made the prediction, didn’t attend the wedding. He didn’t approve of the marriage since his family was Lutheran and my great-grandma Edith was Catholic.

We used to go visit Great-Grandma and Great-Grandpa Schultz when I was a kid. (See photo gallery for pictures of Great-Grandma and Great-Grandpa Schultz.) I was always a little intimidated by their quiet little house and their old-fashioned ways. They were hardworking and good people, but Great-Grandma seemed a little stern and Great-Grandpa was quiet, with a gaze that was startling in its intensity. Great-Grandma was very short and wore dark dresses and aprons all the time. She had long hair, like a kid, which she kept braided and tied on top of her head.

I had heard a story on one of our Montana visits that, decades earlier, Great-Grandma Schultz had a terrible dream about a plane crash and was so upset by it that she couldn’t go to church the next morning. Great-Grandma had dreamt that a plane had crashed into their neighbor’s yard. The neighbors were good friends of their family—the mom was my Great-Aunt Clara’s godmother, and the daughter, Sally Mae, was Clara’s friend the whole time they were growing up. In Great-Grandma’s dream, Sally Mae was there when the plane crashed, and Great-Grandma saw someone covering her with a sheet. The next day in church, my Great-Grandpa learned that Sally Mae and her baby had perished in a plane crash the day before. From then on, I worried that Great-Grandma Schultz could read my mind when we were at their house for visits, so I tried to think only nice thoughts. It was a lot of work.

Great-Grandma Schultz’s mother, Great-Great-Grandma Wieland, had premonitions, too. Her son Henry moved in with her after his father died. Great-Uncle Henry was a kind man with many friends, but he never married. (See photo gallery for photos of Great-Great-Grandma Wieland and Great-Uncle Harry.) He had been injured as a child when he fell off a horse. As a result, one of his legs was four to six inches shorter than the other leg, and he had to wear a special shoe. Henry’s brother Bill was one of my relatives (there were at least three or four) who had a hard time making the transition from horses to automobiles. When he got his first car, he drove it into the garage but forgot how to stop it, so he just yelled, “Whoa, whoa.”

Henry preceded his mother in death. Great-Aunt Clara wrote for our family genealogy book that Great-Great-Grandma Wieland knew before she climbed the narrow stairway to Henry’s room that he had died, because the night before she had “felt someone’s hands feeling alongside the quilt of her bed.” Another story Clara shared about Great-Great-Grandma Wieland was that whenever one of her children died, a star fell across their house. Great-Great-Grandma Wieland had thirteen kids, but only eight lived to adulthood. She lost five children, all under the age of two, in a five-year period. The children died from diptheria and whooping cough. Despite her many losses and hardships, Grandma Wieland was always in good health, right to the end of her life. At age eighty-seven, she came down with pneumonia and seemed “resolved to die.” Again from Clara’s reminisces:

(Great-Great-Grandma Wieland) had a good appetite and ate a meal of sauerkraut and pork the night before she took to her bed, which was a Sunday. She told (Great-Grandma Schultz) what dress she wanted to be buried in, refused to eat the custard that I (Clara) made for her (taking one look at it and saying, “What’s that?”).

On her deathbed, Great-Great-Grandma Wieland fixed her own hair, which, like Great-Grandma Schultz, she wore in two braids, crossed over the top of her head and tied with a string. (Clara had been trying to fix her grandma’s hair but was taking too long.) One family member tried to give her a rosary, others tried to get her to agree to let a minister come by, but Great-Great-Grandma said she didn’t want either one. She died two days after taking to her bed, on May 31, 1932.

It’s not written down anyplace and I haven’t heard anyone tell the story, but I hope that, on the night she died, one more star fell over the house for Great-Great-Grandma Wieland.