Courage is fear that has said its prayers.

Dorothy Bernard

The Yellow Eyes and Other Experiences from Childhood

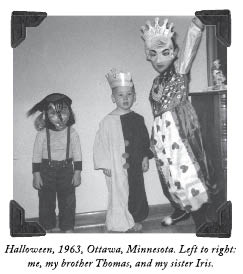

In most ways, my childhood in the 1960s was not only happy but typical. I lived with my mom and dad and six brothers and sisters in southern Minnesota, in an old farmhouse off County Road 23. We had a big yard with a tire swing and a sandbox, several cats and a few dogs, and a blue-eyed albino horse named Trigger who lived to be thirty-three years old. (We attributed Trigger’s longevity to his easygoing nature and slow metabolism.) There was a wooded area behind our house and a field beside it in which our neighbors grew corn some years and soybeans in others. I was fascinated enough by the cornfield to get lost in it once or twice, eventually making my way to our neighbors, the Schweigerts, who gave me orange juice and called my parents. We had a horseshoe-shaped driveway that was great for learning to ride a two-wheeler bike or pulling around a wagon full of dolls. A railroad track ran along the other side of County Road 23, close enough to our house that if we stood at the end of our driveway and waved, the engineer would wave back.

But even some of our childhood pastimes reflected a love of the magical or macabre. One of our favorite games was Bloody Town, a game we made up in which we pretended to be a nice family who got attacked by bloody skeletons. We played Bloody Town in our family station wagon, and although the basic premise never changed—it inevitably ended in a rollicking screamfest—we never got tired of it. Another game we played was a ghostly hybrid of tag and hide-and-seek. The people who were not “it” had to make their way around the dark yard chanting, “One o’clock, the ghost is not out; two o’clock, the ghost is not out” and so on, until the ghost came shrieking out of his or her hiding spot, trying to tag someone and turn them into a ghost, too. Eventually, there was only one unlucky person left who wasn’t a ghost, and that person had to walk around the house alone while an entire horde of ghosts hid in wait.

We also had a scary story ritual: the liver story. My mom only told the story after all of us kids had cleaned our plates on nights that we had the unanimously unpopular supper of liver and onions. In the story, a woman asked her son to go to town and pick up some liver for dinner. On the way home from the store, the boy crossed a bridge and stopped to look down at the water. As he did, the liver fell out of the bag and into the river. To avoid the consequences of his actions, the boy decided to steal the liver from a corpse in the graveyard and bring that home instead. But the corpse was not happy about its liver being stolen and cooked for someone’s dinner. It came out of its grave and followed the boy home, calling, “Whooo stole my liver? Whooo stole my liver?” This spooky story had a wonderfully frightful ending. When the corpse finally caught up with the boy, my mom would grab one of us kids and yell in a corpse-y voice, “Was it you?”

I was raised Catholic, and our religious beliefs included a spirit world that was complex and dynamic, with its own hierarchies, laws, and courtesies. Catholicism provided a framework for understanding the various relationships between the living and the dead, and it taught me that we have powerful allies in the spirit world—a lesson that has served me well living with ghosts. In our down-to-earth Midwestern family, our Catholic faith was expressed as sort of a blue-collar mysticism. The unseen world of spirits and angels and saints was real and part of everyday life, along with chores and school and TV shows. It was evident in the décor of our home, comfortably coexisting alongside homemade art and family pictures. We had guardian angel pictures in our bedrooms, holy water dispensers by the doors, and palm fronds from Palm Sunday above the doorways. A print of Salvador Dali’s version of the Last Supper hung on our dining room wall. There was a statue of the Virgin Mary on the room divider and a painting of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in my parents’ room. I had a beautiful rosary made of pink glass beads, which I thought was way cooler than the glow-in-the-dark plastic rosary that belonged to one of my brothers. I also had small pictures of my patron saints, St. Teresa of Ávila and the “Little Flower,” St. Therese of Lisieux, whose feast days are in my birthday month of October. I knew that souls could get stuck in purgatory and that people on earth—even kids!—could help the lost souls get into heaven with their prayers. From my perspective, this kind of power was akin to magic. Along with praying for the souls in purgatory, I prayed for the starving children in the Maryknoll magazine; I prayed for the people in communist countries; I prayed for our milkman, who had lost his arm in a car accident. (The milkman’s plight was invoked by my parents throughout our childhood if we stuck our arms out the window or otherwise misbehaved on car rides.) The most dramatic and solemn Catholic artifact in our home was a big crucifix with a hidden compartment. Inside the secret compartment were a candle and a vial of oil that were to be used to administer the last rites to a dying person. Regular people had to have these special crucifixes in their home in case someone was in danger of dying before a priest could get there.

My mom told us about the Catholic concept of limbo, too, but said she didn’t believe God would keep any baby out of heaven, and that neither her mother nor her grandmother had believed in limbo, either. My mom was really good at teaching us to be open to possibilities and creating an atmosphere in our home that fostered creativity, imagination, and artistic expression. We spent as much time as possible playing outside, but we talked about our dreams at the breakfast table most mornings. Every night, we’d climb on the couch and my mom would read to us, which, with seven kids, meant we got to listen to as many as fourteen stories before bedtime. My mom also had art books on the bookshelf from her college days, which my brothers and sisters and I were quite interested in because of the risqué and gory images they contained—warrior skeletons on horseback, saints who were beheaded or pierced by arrows, a naked woman at a picnic… An unintended positive consequence of our covert art book fascination was that, even as grade-schoolers, we could identify the artwork of painters such as Renoir, Rembrandt, da Vinci, van Gogh, Picasso, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

I have always had vivid dreams and astral experiences, and one of my worst nightmares ever was during this time of my life, when I dreamt I was trapped in a Seurat painting. The dream began with me sitting alone on some bleachers, watching a circus. As I looked around, I realized that all of the other spectators had an exaggerated and slightly sinister appearance. A feeling of impending doom came over me as I looked down in the ring, hoping to see someone who looked normal. It was then I realized the horse and circus performer were the ones depicted in Georges Seurat’s The Circus and that I was stuck in a painting. My dream came to an ominous close as my perspective shifted from watching the circus to being an observer of my body, sitting alone and terrified as the observant me flew away from the scene backwards, leaving the real me completely deserted, even by myself. I don’t remember exactly how old I was when I had this dream, but I couldn’t have been more than eight. (I know this because we still lived in Ottawa, Minnesota, at the time, and we moved to the Black Hills of South Dakota a few months before I turned nine.)

I had my first precognitive dream when I was a first grader at St. Anne’s Catholic elementary school in Le Sueur, Minnesota. I dreamt that our teacher, Mrs. McIntyre, asked me to pass out papers to all of my classmates. The next day, even though she had never before asked any student to do so, Mrs. McIntyre gave me a stack of papers to hand out. As I walked up and down the aisles just like a teacher, I was so proud I could hardly stop smiling. (While writing this book, I discovered that some seventy years earlier, Annie McDonough, my great-grandma Maggie’s younger sister, had attended St. Anne’s. At the time, the late 1800s, it was a boarding school run by nuns. After their father died, one of Annie’s older half-brothers felt she was not receiving sufficient supervision and arranged for her to go to school in the southern Minnesota town sixty miles away from St. Paul. My family ended up in the same small-town school through a completely unrelated set of circumstances. I think it’s an odd coincidence, but I like the idea that, for a short time anyway, I attended the same school as Great-Grandma Maggie’s little sister.)

Another unusual aspect of my life at this age was my belief that everyone died at night and came back to life every morning. I arrived at that conclusion because I had flying dreams at night in which I flew out of my body and around our neighborhood, over the fields and trees and rooftops. (I now believe that these were astral travel experiences, but that was a concept I didn’t learn about until I was in my late teens.) In one of these flying dreams, I clearly remember looking down at the brown weeds poking up through ice-crusted snow and wondering why I wasn’t cold. But when I mentioned to one of my younger siblings that we died each night, my mom corrected me. I was genuinely surprised when my mom said that we didn’t die each night; we only died at the end of our life. She said I must have been dreaming that I was flying out of my body. Since I knew from church that our physical body was just a temporary home for our spirit, it didn’t seem at all implausible to think of our spirits getting out and flying around every now and then.

This idea of spirits flying around eventually raised the question in my mind of whether ghosts could see you when you took a bath or went to the bathroom. I asked my mom about it, and she told me that spirits had more important things to do. Her answer did not allay my concerns, however, and I came up with an idea that I now view as an effective energetic shielding technique. In one of his sermons, our priest at church had talked about praying for people in the Iron Curtain countries. My mom told me that the phrase “Iron Curtain” was a way of saying that the people were not free to come and go as they pleased and were not free to express their beliefs about God or their government. I pictured the iron curtain as a heavy gray curtain that nothing could penetrate, like the curtain on the cabinet in which the communion wafers were kept at church but on a huge scale. So, whenever I wanted to shield myself from any spirits that might be around, I pictured a big slate-gray iron curtain encircling me and making me invisible.

The first overtly paranormal experience I remember from this time of my life was seeing yellow eyes watching me at night. They looked like animal eyes—elongated yellow eyes that glowed in the dark bedroom. I saw the yellow eyes quite often. I usually saw more than one pair of eyes, and I could see them whether my own eyes were open or closed. They would appear for a short time and then blink out, appearing again in a different spot but always on the edge of my bed or beyond—never any closer. I wasn’t terrified, but I was scared because I knew there was no reasonable explanation for seeing eyes hovering around my room. I knew it couldn’t be a dream, because I hadn’t gone to sleep yet. I prayed to Jesus and my guardian angel to keep me safe. It never occurred to me to tell the eyes to go away, maybe because wishing they would go away didn’t do any good. I shared a bed with my younger sister Betsy, but Betsy had the odd habit of sleeping with her eyes half open, so she wasn’t much comfort. (When we were older, I asked Betsy if she had ever seen the yellow eyes at night, but she had not.)

When the yellow eyes appeared, I usually just closed my own eyes and told myself I was seeing things. It seemed less threatening to see yellow eyes in my mind’s eye rather than hovering around my bed. I grew accustomed to the eyes that watched me at night, and since nothing bad ever happened when I saw them, I gradually became comfortable with the experience. Although I didn’t know it at the time, it was an important lesson for me to learn that astral visions, even if they’re weird or somewhat frightening, are usually just a form of information and not necessarily something to fear.

I’ve given a lot of thought over the years to what the yellow eyes might have signified. Although they looked wolflike, I don’t think they represented a totem animal. I’ve had both dream visits and waking life visions of animal spirits and animal guides, and with one exception, the animal or bird has always appeared in complete physical form. I don’t think the yellow eyes were associated with our house in southern Minnesota, since I saw them in other places where we lived throughout my childhood as well, although not as often. I’ve read that when people start meditating or developing their psychic abilities, their energy body, or aura, becomes brighter and may attract the attention of spirits and other astral beings. Maybe my intuitive abilities were starting to kick in at that age. At some subconscious level, unusual or intense eyes have been a theme in my life since I was young. When I was a child, I was constantly drawing eyes on my school papers and folders, and even now, if I doodle while on the phone or while otherwise distracted, I almost always draw either eyes or flowers. In both my dreams and shamanic journey experiences, I have seen characters with very strange eyes—eyes that have no whites, eyes that are twirling patterns, dazzlingly dark eyes that shine with magical power. One spirit I saw had no eyes—at least, not at first—just empty sockets. I’ve come to believe that the yellow eyes were a portent of my ability to see things that are hidden, the way many animals see well in the dark.

I’ve only seen the yellow eyes a handful of times as an adult, most recently within the last year. After all the unusual paranormal experiences I’ve had in my life, seeing the yellow eyes actually felt friendly and familiar, like a gift from the past.