CHAPTER EIGHT

A Feathered Hammer

My falcon now is sharp and passing empty.

And till she stoop she must not be full-gorg’d,

For then she never looks upon her lure.

—William Shakespeare,

The Taming of the Shrew (ca. 1590)

Astronauts on the moon don’t have a lot of spare time. The Apollo 15 mission marked the first NASA voyage equipped with a lunar rover, and its two-man crew had only eighteen free surface hours to explore the Hadley Rille and the Elbow Crater, take samples from the Genesis Rock, and perform a barrage of groundbreaking tests and procedures. So on August 3, 1971, when Commander David R. Scott stepped in front of a live camera to conduct an unauthorized experiment, he hoped to hell it worked.

“I was going to try it out first,” he later recalled, but the mission’s tight schedule never gave him the chance. “We ended up just winging it!”

The film, a grainy image beamed straight to ground control and from there to the world, showed Scott in his bulky white space suit holding out two objects, a hammer and a feather. Behind him, the landing module hulked like some dark insect, and beyond that the moonscape stretched off to the black horizon. His voice sounded tinny but clear as he explained what he was doing. “I guess one of the reasons we got here today was because of a gentleman named Galileo,” he began, “who made a rather significant discovery about falling objects in gravity fields.”

A few seconds later he dropped the hammer and the feather together from shoulder height. They both fell straight down as if pulled by unseen strings, landing at his feet in the gray lunar dust at precisely the same instant.

“How about that!” Scott exclaimed, and the experiment was over. He and his partner returned immediately to their work, packing instruments for the long homeward journey. They couldn’t even spare a second to pick up the now famous feather—it remains on the moon to this day.

That short sequence became one of the iconic images from the Apollo space program, and it’s still shown regularly in classrooms around the world. Physics teachers use it to illustrate one of the fundamental principles of gravity: falling objects accelerate at the same rate regardless of their mass. Galileo first made this claim in the early seventeenth century, overturning Aristotle’s long-held theory that heavy objects fall faster. But demonstrating the law of uniform acceleration alone wouldn’t have required a trip to the moon. Legend has it that Galileo tested his theory by dropping various-size balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa and timing their descent. Scott could have replicated that experiment back home on the launchpad with a brick and a pebble. He needed the moon shot to field-check another of Galileo’s hypotheses: in a vacuum the shape of an object would be also be immaterial, since there would be no atmosphere to resist its fall. Watching a feather drop in the vacuum of space reminds us that the first ingredient in aerodynamics is “air.”

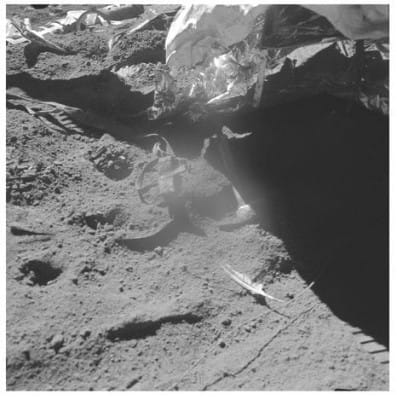

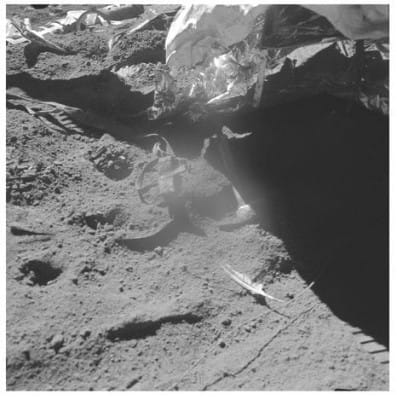

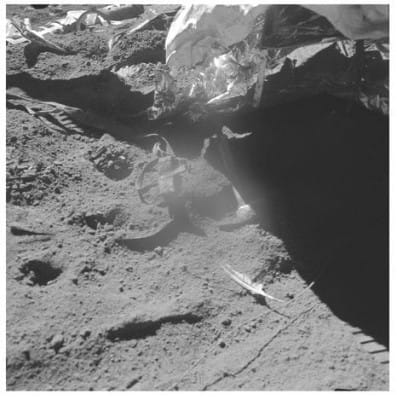

The flight feather of a Peregrine Falcon, dropped on the moon.

I don’t like to take science sitting down, and Scott’s work left one obvious trial untested. When Eliza saw me headed for the Raccoon Shack with a ladder, a hammer, and the crow feather I’d found on my walk with Noah that morning, she said, “I think I know what’s going to happen.” I did too, but I still wanted to see it with my own eyes.

At its peak, the roof of the Raccoon Shack stands eleven feet six inches above the ground, just even with the tallest plum tree in our orchard. I stood there on a sunny afternoon with the feather in my left hand and a hammer in my right, just like Commander Scott. When I set them free, the hammer plummeted straight downward and struck the ground below in just under a second. The crow feather, on the other hand, floated immediately to the side, spun twice in the air, tumbled, caught a breeze, and drifted finally to earth a full six seconds later, twelve feet away from the hammer. It landed quill down, lustrous and black against the grass like a speck of lunar sky.

This exercise accomplished two things. It established the comforting fact that there was a good supply of air around the Raccoon Shack, and it proved beyond doubt that when an atmosphere is present, feathers behave differently from hammers. This latter point is also comforting, particularly to pilots, flight attendants, model-plane enthusiasts, kite surfers, frequent fliers, or anyone else who has depended on airfoils to keep their craft aloft. The feather I used had the distinctive curve and offset rachis of a flight feather, a perfect little airfoil. Its shape and size told me it had come from the crow’s left forewing, but it responded to air like a wing in its own right.

Any feather can drift in a breeze; like autumn leaves, they stay aloft by sheer lightness and large surface area. But of the thousands of plumes that cover a bird, only a few dozen wing and tail feathers have the asymmetrical structure of true airfoils. Layered like rows of winglets nested within each wing and tail, these feathers act both individually and in concert to give birds unparalleled control over the nuances of flight.

In his moon experiment, David Scott opted for a falcon flight feather. He chose it to honor his alma mater, the U.S. Air Force Academy (whose mascot provided the plume) and also because Falcon was the name of the landing module that brought him to the lunar surface. A third reason made his choice even more perfect.

Perhaps better than any other species in history, falcons embody the aerodynamics of a feathered hammer. Diving from great height to snatch their avian prey from midair, they’ve been clocked at speeds faster than a locomotive or a Formula One racer. At that rate, the force of their impact is indeed a hammer blow that can shatter the bones of their quarry, driving their talons home deep. Falcons thrive at the extremes of motion. They make their living by outflying other birds, and they’ve had to develop ways to be faster, more agile, more maneuverable. Watching falcons stoop is a lesson in the possibilities of feathered flight, but they move so quickly, it’s hard to make out the details. I needed an insider’s perspective on falcon aerodynamics, and I was in luck. The year-round community on our island is small, but it happens to include the world’s most famous skydiving falcon, as well as the avid pilot who trained her.

When Ken Franklin jumps from an airplane, he throws Frightful out first. And once both he and the falcon are airborne, he drops a lure, a weighted, aerodynamic bait, that gives her a target to aim for as she dives. Several years ago, Ken added one more thing to the list of items falling from his plane: a National Geographic film crew. Using a tiny modified flight computer attached to her tail, they clocked Frightful diving in a streamlined free fall at 242 miles per hour, a record for animal flight. And with close-up video footage, they were able to see how she did it, stretching her body into a streamlined shape and accelerating downward to do what Ken calls “slipping through the molecules.”

I stopped by the Franklin household on a warm midsummer afternoon, and I could hear Frightful’s piercing “kek-kek-kek” as soon as I stepped out of the car. “We just let her go today,” he said. “She’ll fly free for the next three months or so.” Hand-reared in captivity, the bird imprinted on Ken and his family at a young age and spends much of her time in their aviary, or even inside the house. As we talked, Ken walked periodically out onto the porch, scanning the sky. It seemed an almost unconscious habit. I joined him just as she appeared, diving low over our heads, seemingly enjoying her freedom but not straying too far from home. I watched her turn, tail fanned and narrow wings flapping as she angled up and landed in a nearby fir snag, calling all the while. “It’s risky letting her free. They have accidents all the time,” he said with a note of parental worry. “But she’ll be fine—she’s quite a flier.”

Tan, with an athlete’s build and hair just beginning to gray, Ken has the faraway gaze of someone used to seeing great distances. He makes his living flying jumbo jets for Federal Express, but it’s obvious that his passion lies with the birds. He and his wife, Suzanne, are both master falconers and have raised and trained dozens of birds over the years. Frightful was an apt pupil from the start—alert, loyal, and quick to chase a lure. At thirteen, she has left her skydiving days behind and appears to be enjoying a comfortable retirement in and around the Franklin home. “She’s a good hunter, but she’s perfectly happy being fed all the time,” Ken explained. “A falcon is like anyone else; they’ll do the minimum necessary to get by.” Then he added, “But they’re capable of a lot more.”

As we talked, the understatement in that comment became abundantly clear. Ken showed me a photo enlargement of a bird streaking downward in free fall, wings tucked close and body elongated, like a dark teardrop stretched to a fine point. “This is what I wanted to document,” he explained. “This body shape. This is what they do when they go into warp drive.”

In more than two hundred skydives with falcons, Ken has seen them do amazing things: drafting in the slipstream behind the airplane, revolving to keep their eyes fixed on a spinning lure, or easily keeping pace beside him in free fall. Warp drive happened only occasionally, when they would plummet past him and out of sight, even when he knew he was falling at more than 100 miles per hour. It’s what inspired Frightful’s speed trials, the National Geographic film, and the IMAX movie that followed.

Peregrine Falcons, by Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

I asked Ken what role feathers played in a falcon’s great speed, and he immediately pulled out a picture of a bird in flight. “Look at the feather edges—they’re jagged,” he said, tracing a finger along the wing coverts and the contour feathers covering the back. The tips did look uneven where they overlapped, as if some of the barbs were especially long and stiff. “Hawks, eagles, they don’t have that,” he went on. “It has something to do with airflow, reducing turbulence and drag during their dives. I don’t know exactly how it works, but I’m sure that’s what is going on.” This refrain would become increasingly familiar the more I looked into aerodynamics—feathers enhance bird flight in all kinds of important ways, but the complexity of a living bird wing defies easy quantification.

On his computer, Ken pulled up dramatic photographs of a falcon pursuing a sandpiper at close quarters. The focus was so sharp it captured individual droplets of mud kicked up in the struggle, and every feature of both birds stood out clearly. Frame after frame showed the falcon’s feathers changing as it pulled out of its dive, turned sharply, and maneuvered over its prey. The tail fanned wide. Individual wing coverts were lowered and raised. The flight feathers spread, slotted, and changed angle, and in one shot each outer tip was bent sharply upward. “Their flexibility is amazing,” Ken said, staring at the screen. “In all the dives I’ve watched, I’ve never seen a feather break in flight. Wrestling on the ground with prey, sure, but never on the wing.”

That’s an impressive statement considering the tremendous structural strain of braking and turning at such high speeds. The flight computer attached to Frightful’s tail coverts has revealed some amazing statistics. She once dove after a lure dropped from three thousand feet, accelerating to 157 miles per hour before neatly catching it and pulling up from her stoop a mere fifty-seven feet above the ground. The gravitational force on her body in that moment has been calculated as high as twenty-seven Gs. Fighter pilots risk losing consciousness at anything over nine.

Ken sent me home with a handful of falcon feathers and a lot to think about. Our conversation gave me a new appreciation for the sheer physicality of bird flight, and also its fundamentally three-dimensional nature. In addition to their notorious dives, falcons dart upward and sideways with ease, dance in and out of thermal currents, and hunt their prey in seemingly any direction. “I don’t think that vertical and horizontal mean anything to them,” he said.

I didn’t ask Ken about his motivation or the obvious personal risks he took to jump and fly with Frightful—his drive and curiosity seemed answer enough. But I know he also hopes his work may eventually lead to improvements in aircraft design and that he has collaborated closely with a top engineer at Boeing. Though skydiving with birds may be unique, studying their aerodynamics fits Ken into a long line of aviators who’ve mixed a healthy dose of ornithology into their innovations. It’s a history that puts birds, feathers, and aviation firmly at the heart of one of the hottest trends in the physical sciences.