In a world where men felt increasingly powerless, a tough guy who battled to the top could become an instant hero to those still trapped below.

—EDWARD G. BURROWS AND MIKE WALLACE, GOTHAM: A HISTORY OF NEW YORK CITY TO 1890

Between 1881 and 1924, approximately 24 million immigrants came to America, including nearly two million Jews, mostly from Eastern Europe. The vast majority of immigrants, often penniless and uneducated, crossed the Atlantic in steerage.1 They sailed into New York harbor past the Statue of Liberty and disembarked at Castle Garden, located at the tip of Manhattan. After 1892 all immigrants entering New York Harbor came through Ellis Island, where almost one million people were processed annually until the government severely restricted immigration in 1924.

By 1914 at least half the populations of major cities in the United States lived in poverty. The urban poor, not surprisingly, were disproportionately new immigrants.2 Most of the Jewish immigrants lived in the tenement neighborhoods of New York’s Lower East Side, downtown Philadelphia, the West Side of Chicago, or Boston’s North End—enclaves that ranked among America’s worst slums. These and other inner-city neighborhoods provided most of the fighters and the spectators for boxing.

Although America may not have been di goldene medina (“the golden land”) the immigrants had envisioned, it was still preferable to life in the Russian Pale of Settlement, where many Jews had lived on the edge of starvation and under the thumb of state-sponsored anti-Semitism.

Of immediate concern to city dwellers was the need to find work to pay for food and shelter. But having a job was no guarantee of financial security. Most immigrant workers labored long hours for pitiful wages, and about four of every 10 did not earn enough to support a family.3 Still, there were a few alternatives to the pushcart or sweatshop. If a person could play an instrument, or had a talent for singing, comedy, acting, or dancing, he or she might venture off into the world of vaudeville, live theater, or moving pictures. Show business, especially the flourishing vaudeville circuit, employed thousands of people, many of whom were Jewish.

Another thriving industry with close ties to show business was professional boxing. By the early 1900s there was already a large contingent of Jewish boxers involved in the sport. Indeed, there were so many Jewish people in show business and boxing that anti-Semitism was not a significant problem in either industry. Undoubtedly many fighters would have preferred a career in show business, but their talent was for boxing.

What drove so many impoverished young men to enter the ring was the common knowledge that successful boxers were the highest-paid athletes in the world. It was not unusual for champion boxers to be paid thousands of dollars for just one bout. In 1892 heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan fought James J. Corbett in New Orleans for a “winner-take-all” purse of $25,000, and a side bet of $10,000 apiece, for a total of $45,000 to the winner. The previous evening George Dixon—the first black world boxing champion—was paid $7,500 for successfully defending his featherweight title.4 These were astounding figures when one considers the average annual income for most American workers was less than $1,000.

In the 1920s superstar boxers Mickey Walker, Benny Leonard, and Harry Greb were each taking in well over $100,000 in annual income— the equivalent of several million dollars in today’s currency. The $80,000 salary paid to baseball great Babe Ruth in 1927 paled in comparison to the one million dollars heavyweight champion Gene Tunney received for his title bout with Jack Dempsey that same year.

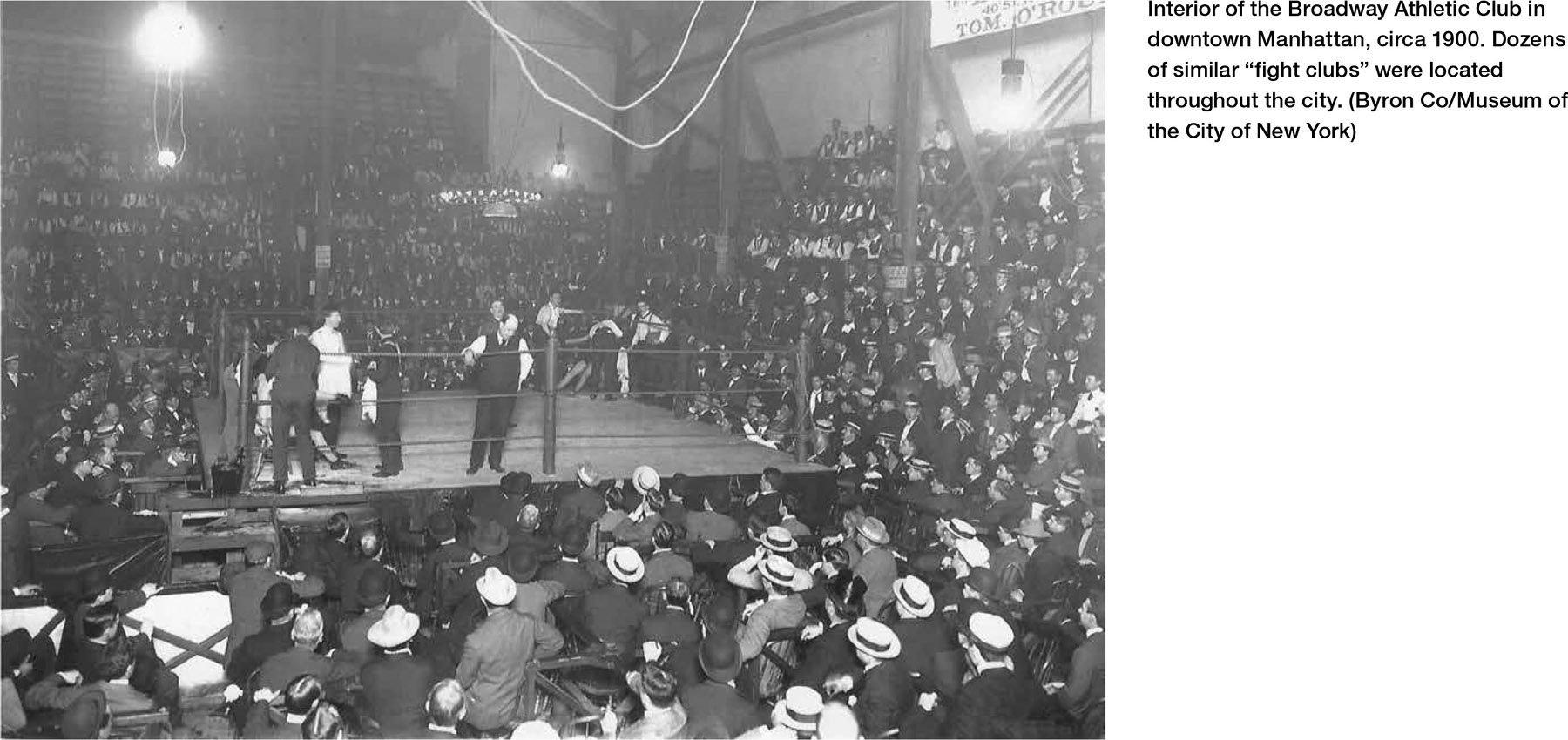

While it is true that only a few top-tier fighters were paid such extravagant sums of money, one did not have to be a world champion or top contender to earn a better-than-average wage. In the same way a mediocre actor or singer might not make it to the Broadway stage but could still find gainful employment in smaller or less-prestigious theaters, the average boxer, despite his limitations, could make a decent living by fighting in the many small arenas (also known as “fight clubs”) that dotted the landscape of every city in America.

In the 1910s and ’20s, even a preliminary boxer could earn more money in one four-round bout than a sweatshop laborer earned in an entire week. Of course, trading punches in a boxing ring was a far riskier activity than bending over a sewing machine for 12 to 14 hours a day, but many young men were willing to accept the risks in exchange for the quick monetary rewards boxing provided.

Venues that featured boxing shows were as ubiquitous as vaudeville theaters. In the New York metropolitan area—the epicenter of the sport for more than half a century—over two dozen arenas operated on a weekly basis within a 10-mile radius of Times Square. A number of National Guard armories also opened their doors to boxing in order to showcase local talent and encourage enlistments. Other cities, large and small, were also hotbeds of activity at both the amateur and professional levels. The supply of available boxers easily matched the demand for their services.

Another reason so many poor boys gravitated toward boxing was the sport’s easy accessibility. Boxing gyms could be found in every urban neighborhood. Free instruction was readily available in settlement houses, boys clubs, community centers, church basements, and public schools. The sport did not require uniforms, expensive equipment, or a field to practice. All that was needed was a room with enough space to spar, exercise, and hit a punching bag. The various weight divisions also made it possible for smaller boys to compete regardless of size.

Boxing attracted a diverse audience from every social stratum, and Jewish fans were among the most enthusiastic. Virtually all were either born in America or arrived as infants or youngsters. It was the same for baseball. There were very few baseball or boxing fans among adult immigrants who came to America in the early years of the last century.

In New York City Jewish boxing fans accounted for about one-quarter to one-third of the audience. The financial success of every major promotion in the city was dependent on the presence of Jewish fans.5 As in all sports, rooting for the home team (in this case, Jewish boxers) motivated participation as spectators. As author David Margolick points out: “For the Jewish boxers themselves, fighting may have been a strictly economic proposition, a brutal but lucrative alternative to the sweatshops. But for their fans, its appeal was more tribal, and primeval. It was a way to assert their status as bona fide Americans, to express ethnic pride, settle ethnic scores, refute ethnic stereotypes; after all, no one ever cast the Irish and Italians as victims and bookworms, cowards and runts. Every Jewish kid ever set upon by street toughs lived vicariously through his Jewish ring heroes, and the heroes encouraged this, often wearing Stars of David on their trunks.”6

Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to believe fan interest was solely based on rooting for “the home team.” Any attractive boxing match, irrespective of the ethnic makeup of the fighters, drew the fans. In addition, just the simple pleasure of a night’s entertainment could provide enough motivation. Margolick: “What drew fans to boxing was more than chauvinism . . . Perhaps it was also part of relishing America after their cloistered lives in Europe, or the Jewish love of going out, whether to vaudeville or to Broadway or to the Yiddish theater on Second Avenue.”7

Boxing promoters sought to exploit ethnic rivalries in order to increase ticket sales by mixing and matching Irish, Jewish, and Italian boxers. Advertising posters often stoked partisan passions with words that would be considered unacceptable today. A 1929 Chicago bout between Jewish Ray Miller and Italian Mike Dundee was advertised as “The Battle of the Hebe and Wop.” The fight was a benefit for the poor of Chicago, and other Jewish fighters were included on the card. “Nobody took offense [to the racial slurs], short and sweet,” says Chicago historian and former boxer J. J. Johnston. “Neighborhood and ethnic rivalries were common and were considered to be just part of the sport.”8

Inter-ethnic bouts kept the turnstiles humming, but any intriguing match, as noted above, was capable of attracting throngs of fans. In 1923, at Yankee Stadium, an all-Jewish title bout matching lightweight champion Benny Leonard of New York against Lew Tendler of Philadelphia drew a record 63,000 fans and earned nearly half a million dollars.

Jewish boxers proved they were brave and tough, but they did fear one personage above all others—their mothers. Despite its popularity, boxing was anathema to immigrant parents who considered the sport to be a violation of the values and traditions of Judaism, not to mention the potential for serious injury. Most Jewish parents became apoplectic when confronted with the knowledge that their son had become a “boxfighter.” They considered the activity a waste of time—goyishe naches (“gentile pleasures”)—and not far removed from a life of crime.

But their children did not see it that way. How could it be otherwise? These young men were growing up as Americans. They belonged much more to the culture of the streets than to that of their families. As historian David Nasaw writes in Children of the City, “The early twentieth-century city was a city of strangers. Most of its inhabitants had been born or raised elsewhere. Only the children were native to the city—with no memory, no longing, no historic commitment to another land, another way of life. . . . Work, money, and the fun that money bought were located on the streets of the city.”9

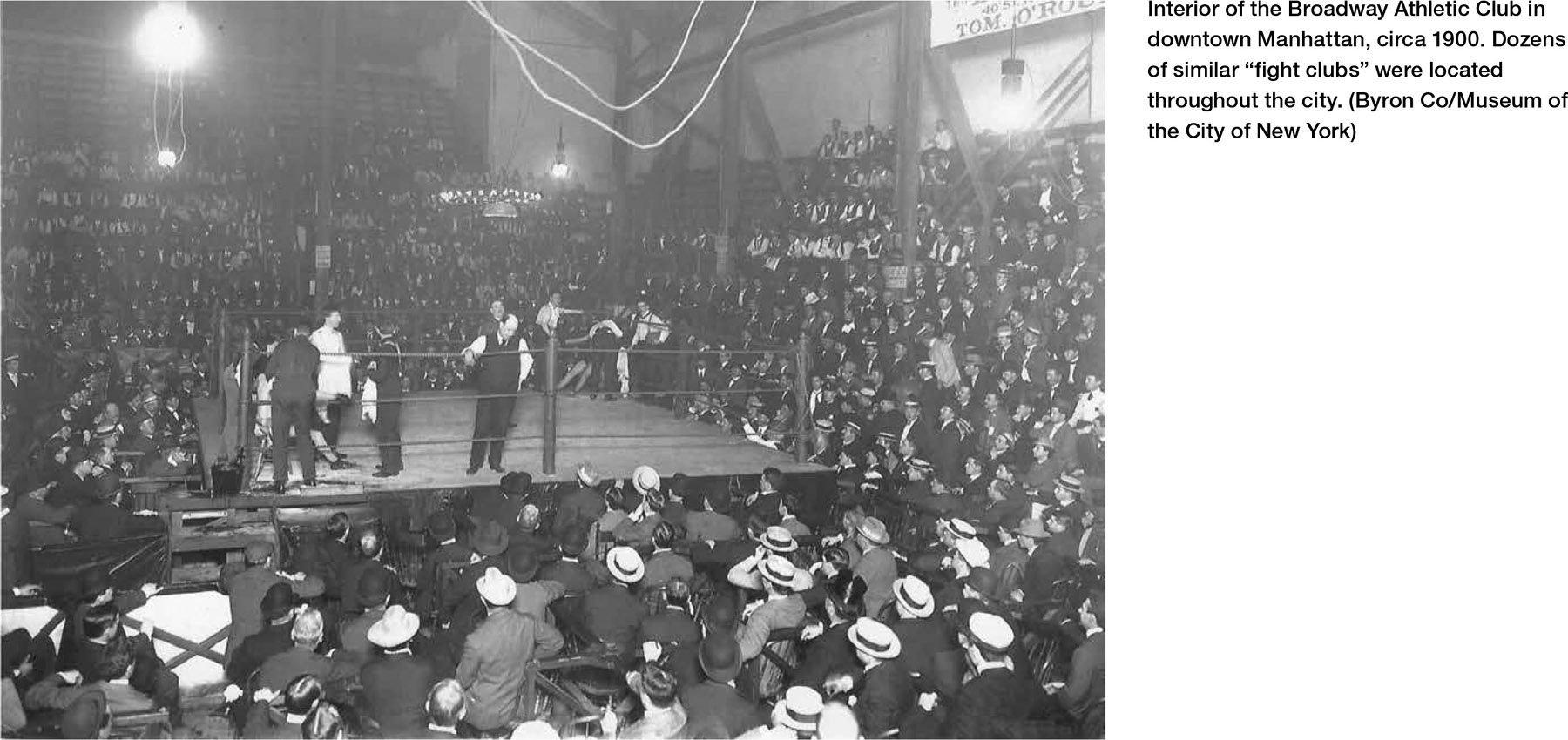

In order to avoid familial conflict many Jewish fighters attempted to hide their profession from disapproving parents by fighting under anglicized versions of their surnames, as did future ring greats Benny Leonard (Benjamin Leiner), Jackie Fields (Jacob Finkelstein), and Barney Ross (Beryl Rosofsky). Some fighters took Irish names for this purpose as well.

The angst produced when parents found out that a son had become a professional fighter was mitigated somewhat by the financial assistance the boxers provided to the family. Benny Leonard described an experience shared by many other Jewish pugilists. During his first year as a pro, Benny came home from a fight with a black eye. He could no longer hide the fact that he had been fighting. “My mother,” Benny recalled, “looked at my black eye and wept.” Benny was guilt-ridden and at a loss for words. He turned to his father, a tailor who worked long hours in a sweatshop. Not knowing what else to do, Benny reached into his pocket and took out the $20 he had earned in the ring that night and handed it over to his father. “My father, who had to work all week for $20, said, ‘All right, Benny, keep on fighting. It’s worth getting a black eye for $20; I am getting verschwartzt (“blackened”) for $20 a week.’ ”10

On July 10, 1917, lightweight boxers “Irish” Frankie Callahan squared off against “Irish” Jimmy Hanlon in the Boston Armory. A Beantown battle between two Celtic warriors was sure to please the fans, and the arena was packed for their 12-round bout. But what most fans in attendance did not know was that neither fighter was Irish. Callahan was a Jew from New York City whose real name was Sam Holtzman. Jimmy Hanlon was no more Irish than Holtzman. He was an Italian out of Denver, Colorado, whose real name was Louis Quarantino.

Frankie Callahan (né Holtzman) was not alone in adopting an Irish surname. Dozens of Jewish boxers assumed Irish surnames for the duration of their careers, especially if they lived in cities with large non-Jewish populations. For Jewish boxers the name change served a dual purpose: It not only kept parents from finding out (at least initially) about a son’s boxing activities, but it also enhanced his marketability, since Irish boxers were perceived as both tough and crowd pleasers.

Two Jewish fighters with Irish surnames became world champions: Al McCoy (Albert Rudolph), middleweight champion from 1914 to 1917, and Mushy Callahan (Morris Scheer), junior welterweight champion from 1926 to 1930. (“Mushy” was a derivation of Morris’s Hebrew name, Moishe.)

Adopting an anglicized version of a name or an Irish nom de box was even more prevalent among boxers of Italian heritage who wished to downplay their own ethnicity at a time when prejudicial attitudes toward Italian immigrants were at a high-water mark. Boxing historian Chuck Hasson has documented over 300 Italian-American professional boxers who fought using Irish names, including four world champions.

The story is told of a manager answering the phone in Stillman’s gym. When the promoter on the other end asked to speak with “Kelly,” the manager responded with “Do you want the Jewish Kelly or the Italian Kelly?”11

By the mid-1920s Jewish boxers had become so popular and numerous that taking an Irish name was no longer necessary. In fact, several gentile fighters changed their names to Jewish-sounding ones to enhance their careers. The best known was Italian American Sammy Mandell (lightweight champion, 1927–1930), whose actual surname was Mandella.

Other notable Italian fighters who changed their names included Boston’s Frankie Ross (Frank Toscano), who named himself after the great Jewish champion, Barney Ross. There was also Joey Ross (Joe Nisivoccia) and Pee Wee Ross (Fred Rossi), Mickey Diamond (Michael Porecca), Al Diamond (Al Pescatore), Tony Fisher (Anthony Fesce), Henry “Kid” Wolfe (Harry Graio), Nick Bass (Nick Basciano), Sammy Fuller (Sabino Ferullo), and George Levy (Mike Paglione).

One of the oddest name changes involved a 1920s Italian preliminary fighter named Lou Centonella, who boxed out of Utica, New York. Jewish fans had difficulty pronouncing his name, so they simply referred to him as “The Luxsh” (Yiddish for “noodle,” as in spaghetti). Lou decided that it would be easier for his Jewish fans to remember his name—and pronounce it—if he renamed himself “Kid Lux.”

At a time when many American Jews found it prudent “for professional reasons” to not call attention to their ethnicity in a sometimes hostile and discriminating environment, their counterparts in boxing were doing just the opposite by proudly emphasizing their heritage—and some of them weren’t even Jewish!

The boxing industry employed thousands of people who worked in various capacities outside of the ring. As they had in show business and the garment trade, Jewish people were involved in every aspect of the professional boxing scene. No other ethnic group, before or since, has so dominated a major spectator sport. They were promoters, managers, trainers, corner men, gym owners, equipment manufacturers, and publishers. All had a significant and positive impact on the sport. Their presence enriched boxing in many ways, and helped to make it respectable, as the following examples illustrate:

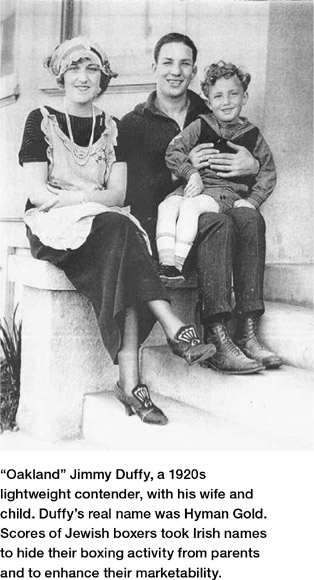

In 1935 Michael Strauss Jacobs, a former associate and financial backer of the legendary 1920s promoter, Tex Rickard, signed an African-American heavyweight contender named Joe Louis to an exclusive promotional contract. Jacobs maneuvered the exciting young prospect onto the world stage while other less resourceful and farsighted power brokers would have preferred to keep him at the back of the bus, so to speak.

“Uncle Mike,” as reporters liked to call him, made it possible for Joe Louis to get a shot at the heavyweight championship in 1937. The great fighter remained champion for the next 12 years, defending his title a record 25 times. Louis’s popularity cut across racial lines. He became an American icon and one of the country’s key black figures of the twentieth century. “The Brown Bomber’s” brilliant record as champion, his service with the army during World War II, and the dignified manner in which he wore the crown paved the way for Jackie Robinson, in 1947, to become the first African American to integrate major league baseball.

Joe Louis was always generous in his praise of Jacobs, whom he considered more than just a business acquaintance. “If it wasn’t for Mike Jacobs I would never have got to be champion,” said Louis. “He fixed it for me to get a crack at the title, and he never once asked me to do anything wrong or phony in the ring. . . . He made a lot of money through me, but he figured to lose, too.”12

In 1937 Jacobs formed a partnership with Madison Square Garden and became the director of its boxing department. Over the next 10 years his Twentieth Century Sporting Club staged 320 boxing cards, including 61 world-title bouts.

Jacobs maintained his headquarters in the Brill Building, which was located halfway down the block from his theater ticket agency. Both were located on 49th Street between Broadway and Eighth Avenue. The sidewalk in front of both establishments, especially on days when a big fight was coming up, was always crowded with fighters, managers, and promoters from out of town who were seeking favors from Jacobs. Damon Runyon dubbed the area “Jacobs Beach.” For the fight crowd this was the place to be seen, the place to make contacts.

The boxing industry thrived and prospered under Mike Jacobs’s watch. Although a hardnosed businessman, he was fair and honest in his business dealings with the boxers he promoted. He never abused his position to the detriment of the sport. The fans always knew they would get their money’s worth when attending a Mike Jacobs promotion.

Jacobs’s most famous promotion was the historic Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling heavyweight championship bout in 1938. His highest-grossing fight was the second Louis vs. Billy Conn title bout in 1946, which drew a live gate of almost two million dollars, second only to the Dempsey-Tunney “long count” bout of 1927. In the late 1940s ill health forced Jacobs to relinquish his position with the Garden. He passed away in 1953 at age 73.

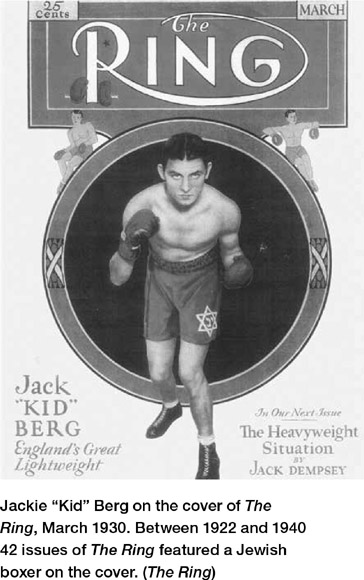

One cannot imagine boxing’s Golden Age without the presence of The Ring magazine and its irreplaceable publisher, Nat Fleischer. In 1922 Fleischer, a 33-year-old sports editor for several New York dailies, launched The Ring magazine with promoter Tex Rickard serving as a silent partner. Fleischer acquired sole ownership in 1929. The Ring quickly became boxing’s most important and authoritative publication. Every month for 50 years Fleischer produced the magazine that came to be known throughout the world as “The Bible of Boxing.”

In 1924 Fleischer initiated a rating system for boxers. He also wrote numerous books related to the sport, and published the annual Ring Record Book and Boxing Encyclopedia, an indispensable source of data for matchmakers,13 managers, and fans. In the 1930s he began presenting title belts to every new world champion. The Ring established boxing’s first hall of fame in 1954.

Using the editorial pulpit of his magazine, Fleischer often spoke out against corruption within the sport, and advocated for standardized physical exams and rules. In a 1936 editorial he urged support for an American boycott of the Berlin Olympics to protest the Nazi government’s treatment of Jews. The boycott did not happen, but the effort was typical of the man. Under his stewardship The Ring was not only the sport’s most influential publication, but also its moral compass, as well. Issues of the magazine from the 1920s to the 1950s are considered collectors’ items today, and are still sought after and read avidly by historians and fans.

Fleischer loved boxing and devoted his life to it. He traveled extensively as an informal ambassador for the sport, and was welcomed by royalty and foreign dignitaries. If anyone deserved the title of “Mr. Boxing,” it was Nat Fleischer.

Sadly, after Fleischer’s death in 1972, The Ring began to deteriorate along with the sport. The magazine remained in operation under relatives of Fleischer, but a devastating blow occurred in 1978 when it was discovered that a key employee had altered the magazine’s monthly ratings to favor fighters connected to a Don King–produced televised boxing tournament. King’s promotion was discovered to be riddled with corruption involving payoffs, extortion, and phony ratings. The resulting scandal ruined The Ring’s once-stellar reputation—a reputation Nat Fleischer had spent most of his adult life building. In later years the magazine attempted, under several different owners, to reclaim its former status.

The late Harry Shaffer, a boxing historian and archivist, provided a very accurate assessment of Fleischer’s legacy: “When Nat Fleischer died, that was the end of boxing as an organized sport. Fleischer is what held it together. . . . They talk of having a commissioner for boxing. That’s really what he was. He was the one they all went to. He was an honest broker, a situation which boxing has never had again.”14

Who is not familiar with the name “Everlast”? The company started by Russian-Jewish immigrants in 1910 became the largest manufacturer of boxing equipment in the world, and a trademark synonymous with the sport ever since.

The manufacture of boxing apparel was an offshoot of the Jewish-dominated garment industry. Before Everlast made its first pair of boxing trunks, the company name was used to identify its line of swimsuits. Today Everlast is a publicly traded corporation. In addition to boxing equipment (now less than 5 percent of its total sales), Everlast also licenses its logo to companies selling men’s and women’s athletic apparel, sports nutrition products, and footwear. Other major suppliers of boxing gloves, trunks, and equipment from the 1920s to the 1960s included Levinson, G & S, Tuf-Wear, and Ben Lee, all owned by Jewish entrepreneurs.

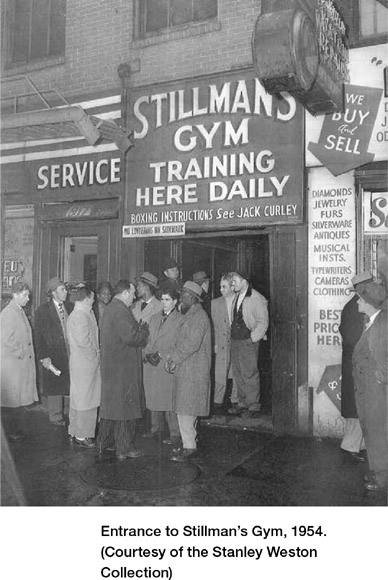

In 1920 a former Jewish policeman named Louis Ingber was managing a gym on 125th Street and Eighth Avenue in Manhattan for disaffected youth. The gym was operated by the Marshall Stillman Movement. Marshall Stillman was a millionaire and philanthropist who built gyms for underprivileged children to get them off the streets and into a healthful environment.

At that time many of the city’s top professional boxers, including the famous lightweight champion Benny Leonard, worked out at Grupp’s gymnasium, an established professional boxing gym located nine blocks south on 116th Street. Unfortunately, the owner of that gym had a drinking problem, and when plastered started blaming the Jews for World War I, which certainly wasn’t good for business, since the majority of the gym members were Jewish. Fed up with his anti-Semitic tirades, Benny Leonard led a mass exodus of all the Jewish fighters to the gym operated by Marshall Stillman. Leonard asked Lou Ingber if they could use his gym in the evenings to work out (the kids used the gym in the afternoons). Ingber was thrilled to have the great champion and the other boxers use the gym.

When word got out that Leonard was now training at a new gym, scores of other fighters and trainers joined him. Within a very short time Stillman’s became the top boxing gym in the city and a magnet not just for the city’s professional boxers, but for hundreds of fans who came to the gym every week to watch them train. The spectators were more than willing to pay the 15-cent entrance fee (raised to 25 cents in the 1940s, and then 50 cents in the 1950s). Posted on a sign outside the gym were the names of famous boxers who were training that day.

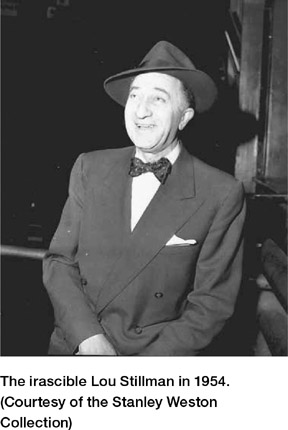

Everybody called Lou Ingber “Mr. Stillman,” thinking that was his name. He decided it was easier just to be known as “Lou Stillman,” and that was the name he answered to for the next 40 years.

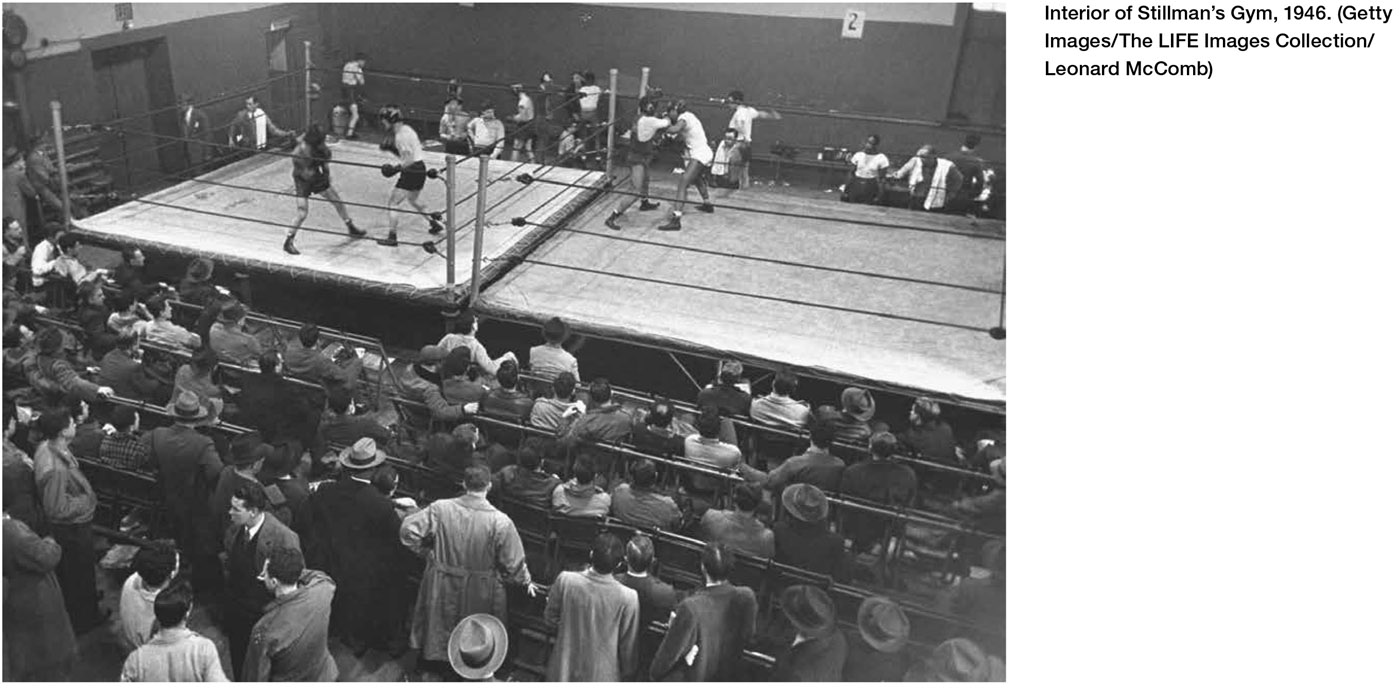

In 1931 Stillman purchased the gym outright from the owners and moved it to much larger quarters on Eighth Avenue, between 54th and 55th Streets, just four blocks north of Madison Square Garden. The new gym occupied the second and third floors of a three-story loft building. Two full-size rings for sparring occupied the second floor, with 10 rows of wooden chairs for spectators. The third floor contained another ring, but also had plenty of space for shadow boxing, floor exercises, jumping rope, and hitting the various punching bags. (The third ring was removed in the 1950s.) The place even had a small lunch counter on the second floor where the aroma of hot dogs and coffee mingled with the pungent odor of leather, sweat, cigar smoke, and liniment.

For little more than the price of a cup of coffee, fans got to see Jack Dempsey, Benny Leonard, Johnny Dundee, Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong, Tony Canzoneri, Primo Carnera, and hundreds of other world-famous boxers work out.

Lou Stillman was a colorful and irascible Damon Runyonesque character right out of central casting. The former beat cop always wore a .38 pistol in a shoulder holster underneath his suit jacket. He ran the gym like a dictator, and the fighters, managers, and trainers took his abuse because he had the key that opened the door to the most famous training site in the world.

Lou would sit on his perch near one of the rings and announce in his raspy voice which fighters were about to spar. At times the spectators taking in the scene not only saw the leading fighters of the day, but also movie stars, Broadway performers, and such famous Mob tough guys as Legs Diamond, Dutch Schultz, and Owney Madden. For decades Stillman’s was a place where rival elements of the underworld could meet under a flag of truce. During boxing’s heyday an afternoon at Stillman’s gym provided one of the greatest shows in town. Many visitors to the city considered Stillman’s as important a New York City landmark as the Empire State Building, Statue of Liberty, or Radio City Music Hall.

The gym made an appearance in two classic Hollywood movies: Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), which depicted the life story of former middleweight champion Rocky Graziano, and The Naked City (1948), a film shot entirely on the streets of New York. Character actor Matt Crowley played the role of Lou Stillman in the Graziano biography.

Gene Tunney once put a knock on the gym, claiming the windows were kept closed and never washed. He considered the facility unsanitary and refused to train there. But Rocky Graziano spoke for most members when, after a few days at an outdoor mountain training camp, he rebelled and returned to his favorite gym, saying “that fresh air would poison a guy.”15

During its 40-year run, from 1921 to 1961, it is estimated that more than 30,000 boxers passed through Stillman’s grimy but hallowed environs.

In the 1920s New York’s four major Yiddish dailies had a combined circulation in excess of 400,000. Despite boxing’s popularity, the negative attitude of immigrant parents toward the sport was apparently shared by the learned editors and publishers of the Jewish press. The Jewish Daily Forward—the most widely read Yiddish newspaper, with a circulation of 275,000—rarely reported any news related to the sport. But not all sports were dismissed out of hand; The Forward did print the results of European soccer matches, since many older immigrants had followed the sport in Europe.16

The Forward began publication in 1897 under the able leadership of Abraham Cahan. The newspaper became known as “the conscience of the ghetto” for its advocacy of Jewish causes, American democracy, and its defense of the rights of working men and women. In addition to general news, it also featured articles on literature, art, drama, and politics.

Aside from educating its readers in the American way of life, The Forward was also a strong advocate for social reform, and was heavily supportive of labor unions and the fight for a just society. The editors probably viewed the gambler-infested world of professional boxing as a further exploitation of the working-class poor, and an unworthy profession for Jewish boys. But in its ambivalence toward the sport, The Forward ignored a significant aspect of life in the city.

The Forward’s first mention of boxing did not appear until July 22, 1923, the day before lightweight champion Benny Leonard fought his great rival, Lew Tendler, at Yankee Stadium. The event was just too big to ignore. Two days later a headline announcing Leonard’s victory appeared on the front page. Boxing was not mentioned again for another five years.17

Finally, in 1928, at the apex of Jewish involvement in the sport, The Forward inaugurated a weekly boxing column that appeared next to the European soccer scores. The column lasted about a year, after which boxing was reported only sporadically.

By the 1950s there was no need to report on the activities of Jewish boxers because they had essentially disappeared, along with the grinding poverty, pushcarts, and sweatshops of the ghetto neighborhoods. American Jews had become fully integrated into the economic and social mainstream of society. Their children were encouraged to attend college and pursue professional careers. The Jewish boxer was a rapidly vanishing species.

The sons and grandsons of Irish and Italian immigrants were slower to leave the sport, but their numbers were also greatly reduced. In the decades following World War II, African-American and Latino boxers would take their place and inexorably rise to the forefront of the boxing pantheon.