Benny Leonard moved with the grace of a ballet dancer and wore an air of arrogance that belonged to royalty.

—DAN PARKER, NEW YORK SPORTSWRITER1

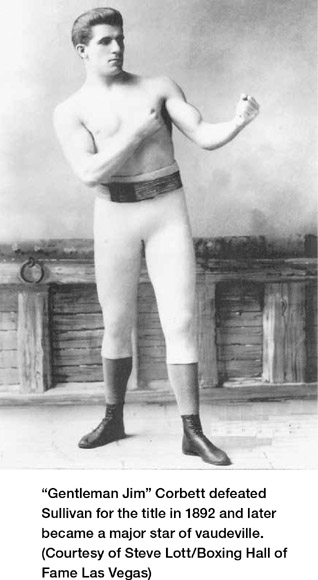

Perhaps the most famous date in boxing history is September 7, 1892. In the first heavyweight championship fight conducted under Marquess of Queensberry rules, James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett knocked out defending champion John L. Sullivan (“The Boston Strong-boy”) in the 21st round of a fight to the finish. The historic event took place in New Orleans in front of 20,000 spectators. Both fighters wore five-ounce leather gloves.

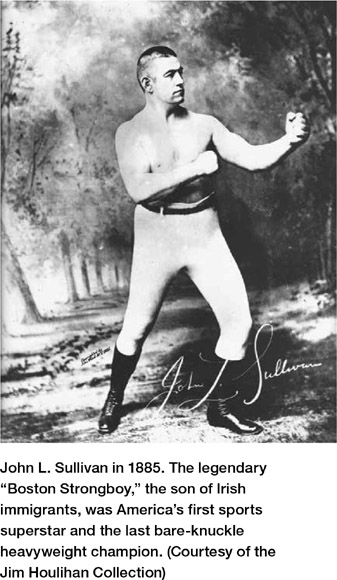

Sullivan, the son of Irish immigrants, was the nation’s first sports superstar. He won the bareknuckle heavyweight championship in 1882 and held the title for 10 years. The powerfully built champion stood five feet, ten inches tall and weighed about 200 pounds in his prime. A man with a prodigious appetite for food and liquor, and the ego to match, Sullivan was famous for entering saloons and bellowing, “I can beat any sonofabitch in the house.” America loved him.

“Gentleman Jim” Corbett, a 26-year-old former bank clerk, stood a shade over six feet and tipped the scales at 180 pounds. A superb athlete and former amateur boxing star, he was the quintessential “Fancy Dan”–type boxer, relying heavily on speed, timing, accurate jabs, evasive footwork, and skillful counterpunching to wear down opponents.

Sullivan, 34 years old, had not defended his title in three years. Nevertheless, the hugely popular champion was still considered invincible. Corbett’s great victory over the legendary champion was a shocking upset that signaled the beginning of a new era for the sport. From that moment on virtually all boxing matches would be conducted using Marquess of Queensberry rules. The bare-knuckle era of prizefighting had officially come to an end.

Unlike the brash, boisterous, and hard-drinking Sullivan, Corbett was an elegant and refined individual who helped to transform boxing into a respectable sport. With his matinee-idol looks Corbett parlayed the championship into a successful career in vaudeville, eventually becoming one of the highest-paid stage actors of his day.2

Corbett’s clever style of boxing influenced other fighters to adopt a more-cerebral approach to the game, and it is not inaccurate to label him the father of modern scientific boxing. But old traditions die hard. Many boxers continued to advance and retreat in a straight line while attempting to land hard singular punches. Another holdover from the bare-knuckle era was the “finish fight” that allowed a bout to continue indefinitely until one of the contestants was either knocked out or disqualified. Finish fights remained in vogue until the early 1900s. They were eventually phased out, but taking their place for a time were marathon contests scheduled for 25 or 45 rounds.

Boxers preparing for a marathon contest trained and fought with the distance in mind. Pacing was extremely important. There was always the danger of expending too much energy too soon. Marathon bouts followed a familiar pattern. After a few moments of sparring an attempt was made to land one or two quick punches, after which the fighters fell into a clinch and continued close-quarter infighting interspersed with a great deal of pushing, pulling, and tugging on the arms. At the referee’s discretion the boxers were separated and the process would begin again. The purpose of this strategy was to gradually wear down an opponent over the long haul. A fighter showing signs of fatigue would be the signal for his adversary to pick up the pace and try for a knockout.3

After 1910 boxing contests scheduled for more than 20 rounds were rare. For a while some cities and states went to the opposite extreme by limiting all professional bouts to not more than four or six rounds, as was the case in Philadelphia and California. As a result, the tempo of fights speeded up and boxing styles became more fluid and rhythmic. Mobile footwork took on added significance as fighters realized that constant movement was not only a good defensive strategy, but also presented more opportunities to set up a variety of combination punches. With the elimination of marathon bouts it was no longer necessary to “coast” for several rounds in order to conserve energy, as was the case in fights exceeding 20 rounds.

From an economic standpoint the shorter contests also made it easier for boxers to compete more often and earn additional paydays. Even die-hard bare-knuckle fans had to admit that boxing had become a faster, more interesting, and more enjoyable sport to watch.

As with any new art form—and make no mistake, Queensberry boxing had transformed the sport into a new art form—there is always a small group of pioneers who exhibit a singular genius for their craft and set the standard for later generations. Some of the greatest boxers who ever lived reached their primes during the first two decades of the twentieth century. “Sweet scientists”—boxers with especially skillful techniques—such as Joe Gans, Abe Attell, Sam Langford, Joe Walcott, Jack Johnson, Jack Blackburn, Owen Moran, Freddie Welsh, Jem Driscoll, Packey McFarland, Mike Gibbons, and Benny Leonard—were among a small group of brilliant innovators who would have stood out at any time. The few existing films of these early pioneers bear witness to their extraordinary boxing skills.

Boxing’s growing popularity in America during the early years of the last century did not deter government authorities and social reformers from attempting to outlaw the sport, primarily because of its association with gambling, and the view that public displays of violence were immoral.

Nevertheless, a total ban was difficult to enforce. Enterprising promoters skirted laws that banned boxing in their states or municipalities by staging sparring “exhibitions” for private club members. The price of admission made the purchaser a member of the club, albeit for one night only. The majority of these bouts were authentic boxing contests with each competitor doing his best to win.

Yet even in places where professional boxing was both legal and popular, the sport was never more than a scandal or two away from being banned. A compromise of sorts was reached with the creation of the so-called “no-decision” rule. The rule mandated that unless a bout ended in a knockout there would be no winner or loser declared. No-decision bouts were intended to discourage gambling and rid the sport of crooked referees, judges, and fixed fights.

At least a dozen states adhered to the no-decision rule from about 1910 to 1925. The policy was frustrating to both boxers and fans. A champion could be dominated by a worthy challenger yet still retain his title as long as he stayed on his feet to the final bell. Any fighter who realized he was overmatched or just didn’t feel like extending himself could stall, clinch, and backpedal to the final bell. By avoiding a knockout an official loss would not be posted to his record.

No-decision bouts (indicated by the letters “ND” in the record books) failed to curtail gambling. In order to satisfy bets gamblers agreed to abide by the opinions of a consensus of sports-writers as reported in the next day’s newspapers. Therefore the letters “ND” came to also stand for “newspaper decision.”

Over the past 20 years dedicated researchers affiliated with the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO) have spent countless hours tracking down these newspaper reports in an effort to try and determine the actual winner of thousands of no-decision bouts that did not end in a knockout. The results are posted on the Boxrec.com Internet site. (Even though newspaper decisions cannot be considered “official,” and the opinions of the sportswriters not always reliable or accurate, I have decided to include the newspaper verdicts, when available, in the records of the boxers who appear in this book.)

Prior to 1921 a boxer’s contender status, or his designation as a world champion, was not dependent on a sanctioning organization. Rather, it was determined by his record against quality opponents with established reputations. In either case it was acceptance by the press and public that was key to a fighter’s recognition factor. Of course, imperfections existed. There was the problem of no-decision bouts and of some deserving fighters being denied the opportunity to challenge for a title despite their excellent records. The latter injustice applied especially to several great black boxers, most notably Sam Langford.

Yet, despite its flaws, the system worked to the extent that a boxer could not enter the golden circle of top contenders without first establishing legitimate credentials by defeating other quality boxers. Any claim to a title by a fighter whose accomplishments in the ring did not measure up to that standard would be ignored.

When boxing reached unprecedented levels of popularity in the 1920s, a more-formalized structure was called for. In 1921 the powerful New York State Athletic Commission and the newly formed National Boxing Association (a loose confederation of 23 state boxing commissions, soon to expand to 43) gave their imprimatur to boxers who they felt deserved the title of “world champion.”

Boxing has always been a difficult sport to regulate. Even during the best of times there were disparate claims and counterclaims of men purporting to be world champions. Nevertheless, from the 1890s to the 1960s the boxing establishment was able to maintain a semblance of order when it came to anointing legitimate world champions. Before boxing’s traditional organizational structure fell apart in the late 1970s— and became hopelessly Balkanized by a gaggle of competing quasi-official boxing authorities doling out scores of title belts—there was much less confusion as to who deserved the title of “world champion.” Prior to the 1970s a fighter who won a title recognized by either the National Boxing Association, New York State Athletic Commission, or the European Boxing Union, was considered a legitimate champion. More often than not, all of these organizations recognized the same world champion.

Beginning in 1914 large numbers of Southern blacks began to migrate north to escape racial violence and to seek greater opportunities for employment and a higher standard of living. The exodus continued into the 1920s and ’30s.

Eventually some two million (over 20 percent of the South’s black population) moved from the rural South to the industrial North. In Chicago the black population more than tripled in a decade.4 Like the first- and second-generation European immigrants, some chose to make their living as boxers to escape the ghetto and perhaps get rich. By the 1930s there were nearly 2,000 black professional boxers in the United States.5

Despite their hopes for a better way of life, most blacks in Northern cities continued to live at or below the poverty level. Buying a ticket to see a boxing show was a luxury few could afford. Without the support of a substantial fan base, African-American fighters had no economic leverage when attempting to obtain a title bout, since white audiences made up the majority of spectators. With the exception of a few crossover stars, there was no economic benefit for a promoter to risk a popular white champion’s title against a black fighter who, if he won, would not bring in the crowds.

Between 1890 and 1936 only 12 black fighters won a world title as compared to more than 100 white/Anglo fighters of several different nationalities.6 While it is true there were many more white prizefighters at the time, several highly ranked black contenders were denied the opportunity to fight for a championship, or, when granted the opportunity, were often the victims of wrongful decisions favoring a white opponent. Sometimes black fighters of the era had to agree in advance to take a dive or “carry” a good local boxer in order to get a payday or secure future bouts.

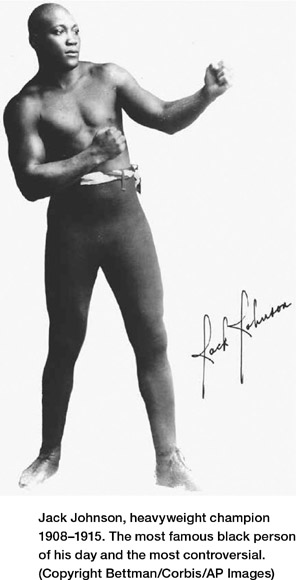

Heavyweight contenders had an especially tough time in the aftermath of the controversial reign of Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion (1908–1915). Johnson, the son of ex-slaves, was the most famous black person of his day, and also the most controversial. He lived by his own rules and wanted nothing more than to be treated as an equal to any white man. But he antagonized much of white America by not only winning the world’s most prestigious sports title, but also by blatantly defying the Jim Crow conventions of his era. He was married twice to white women, lived extravagantly, was outspoken, and enjoyed taunting white challengers in the ring (all of whom could not lay a glove on him). During his tenure as heavyweight champion he famously hired a white chauffeur to drive him around.

Ironically, after winning the championship Johnson refused to risk it against two other great black boxers, Sam Langford and Joe Jeanette. Although he defeated both men prior to winning the championship, they were still considered his toughest challengers. Instead, Johnson preferred to defend his title—and earn more money—by facing a series of less-talented white challengers.

Johnson could not be defeated in the ring, but the courts were another matter. In 1912 the government accused him of violating the Mann Act (bringing a woman across state lines “for immoral purposes”). An all-white jury convicted Johnson on the trumped-up charges and he was sentenced to a year in prison. While out on bail pending an appeal, Johnson fled to Canada, and then to Europe. In 1915, while still in exile, he lost the title to “White Hope” Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. More than two decades would pass before another black man would have the opportunity to fight for the heavyweight championship.

Johnson returned to the United States in 1920 and served out a one-year sentence in a federal prison.

In 2013, for the third time in less than a decade, a bipartisan group of US lawmakers sent a resolution to the president’s desk, urging him to grant Jack Johnson a posthumous pardon. If granted, the pardon would rectify a historical wrong and clear Johnson’s name for a criminal conviction that was obviously based on racism.

Even though it was impossible to completely bypass the blatant racism and elitist attitudes of the era, no other professional sport was more receptive to black athletes. Prior to 1947, when baseball finally allowed the great Jackie Robinson to integrate the major leagues, boxing was the only major professional sport that was open to African-American athletes, and was one of the few professions that gave black people access to the type of wealth and fame that would have been unthinkable a generation earlier. That fact in no way diminishes the humiliations and privations they suffered as second-class citizens. It should also be noted that not all white champions or top contenders avoided meeting highly rated black boxers. Jewish champions Benny Leonard and Maxie Rosenbloom were among those who unhesitatingly faced the finest black contenders both before and during their title reigns. It is a matter of record that Rosenbloom fought more black boxers (70) than any other white fighter of the 1930s.

During America’s participation in World War I (1917–1918), boxing was used to entertain and condition American soldiers and sailors. Famous boxers such as Benny Leonard, Johnny Kilbane, Freddie Welsh, Johnny Coulon, and Mike and Tommy Gibbons led mass exercise drills and participated in exhibition bouts on military bases.

The “War to End All Wars” came to an end on November 11, 1918, but it would be months before millions of Allied soldiers stationed in France could be sent home. An American Expeditionary Force (AEF) boxing tournament proved to be very popular with the doughboys and military brass. The army’s director of athletics suggested an even bigger Olympic-style sports tournament that would involve all the nations that had fought on the Allied side. The idea was to keep the doughboys and other Allied soldiers entertained, “to avoid the peace-time threat to the moral standards and conduct of idle troops waiting to be discharged.” Soldiers of the 29 nations who fought on the Allied side were invited to compete. Eighteen nations accepted the invitation. The tournament was open to both amateur and professional athletes.7

The French government welcomed the idea and authorized the building of a stadium in Paris with a seating capacity of 25,000. The structure was built by the US military in cooperation with the YMCA and was named Pershing Stadium, after the renowned general who led the American Expeditionary Force.8

Of the 14 Olympic events in the “Inter-Allied Games,” none was more popular than boxing. The huge number of preliminary bouts over the five months leading up to the finals drew thousands of competitors into the ring. Three of the seven weight-division championships were won by Americans.

The results of the boxing tournament were reported daily in the American press and proved to be a public relations bonanza for the sport. The success of the tournament was instrumental in helping to legalize boxing throughout the United States. As Jeffrey T. Sammons notes in Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society, the tournament “legitimated the martial arts and fused boxing with patriotism. . . . After the horrors of mustard gas, bombs, mortars and machine guns, boxing represented a more simple and noble past, with men in control of their destiny. Indeed, the barbarism of real war made boxing seem dignified, if not dainty.”9

Most of the boxers who appear in this chapter fought at weights ranging from 118 to 160 pounds. This is not surprising, since prior to 1920, most men, on average, weighed below 160 pounds. Although there was no shortage of heavyweights (over 175 pounds), there were far more boxers competing in the lighter-weight divisions.

Also evident are a high number of losses in many of the records. Those losses must be evaluated in the context of the era in which these men fought. Boxing was a full-time occupation. One could not depend on the occasional big payday to pay the bills, so it was desirable to fight as often as possible. Fights were spaced weeks or sometimes days apart. It was not uncommon for boxers to average 12 to 20 fights a year. (Today the average is about four fights a year.)

Out of necessity the old-timers often competed with bruised knuckles and facial cuts or contusions that had not fully healed. One could not be expected to perform at his very best each and every time under these circumstances. Sometimes the goal was just to fight cautiously and go the distance without getting too banged up. It would not make sense for a fighter to wear himself out or risk injury against a tough but mediocre opponent if he was committed to fight a more-important bout two or three weeks later. Another factor to keep in mind is that the best boxers often faced each other. A loss now and then was to be expected.

The intense level of activity looks almost unbelievable today. For some of these fighters the end result had dire physical and mental repercussions in later years, most often if they fought too long beyond their prime. The damage caused by repetitive head trauma often led to various stages of dementia in later life. Others were more fortunate; they were able to get on with their lives without the consequences of too much damage.

The fighters profiled in this chapter began their professional careers prior to 1915. Among them are some whose careers bridged the 1910s and ’20s. If a fighter’s prime extended into the second half of the 1920s, he is included in the next chapter.

Debates still rage as to how these early pioneers of gloved boxing compared to the best boxers in the decades that followed. But one conclusion is incontestable: The contenders and champions who fought from the 1890s to the late 1910s were as tough and determined a bunch of pugs as ever laced on a pair of boxing gloves— maybe the toughest.

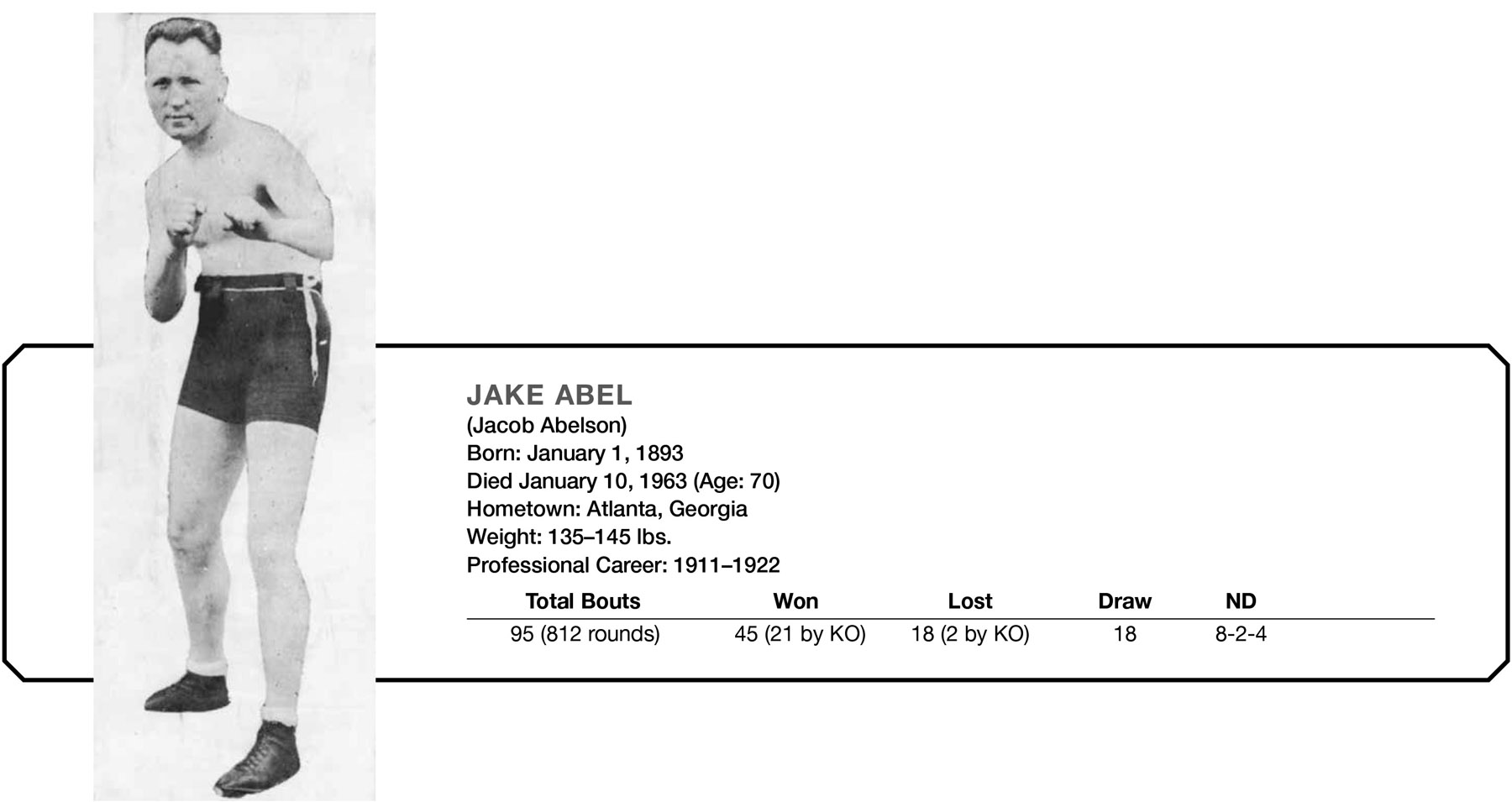

Jake Abel

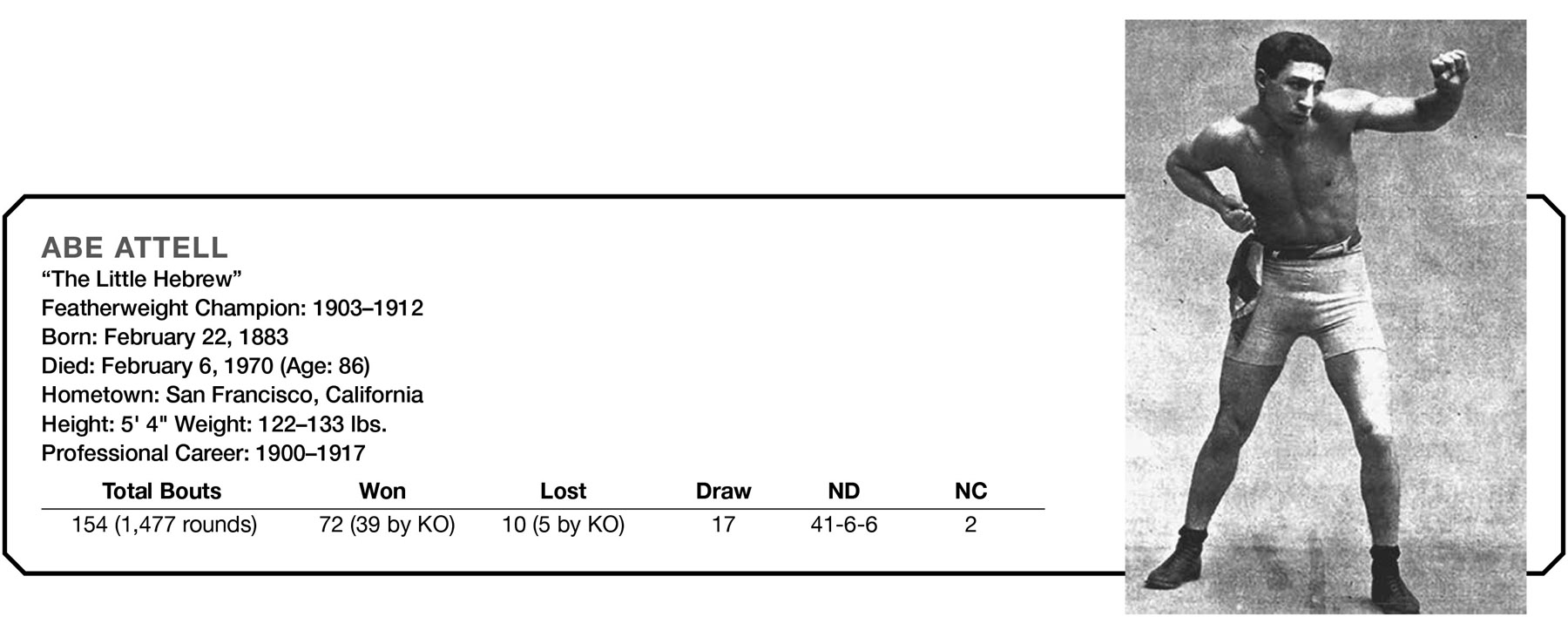

Abe Attell*

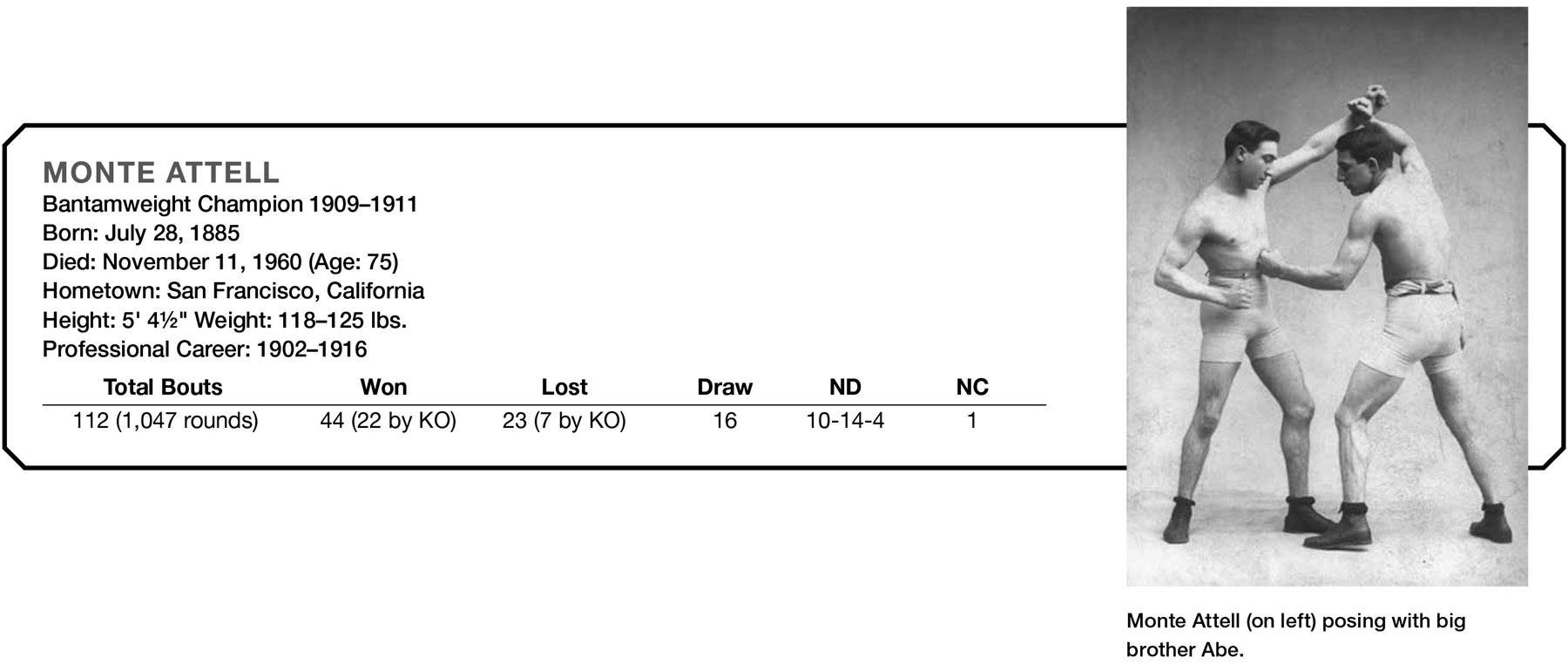

Monte Attell*

Soldier Bartfield

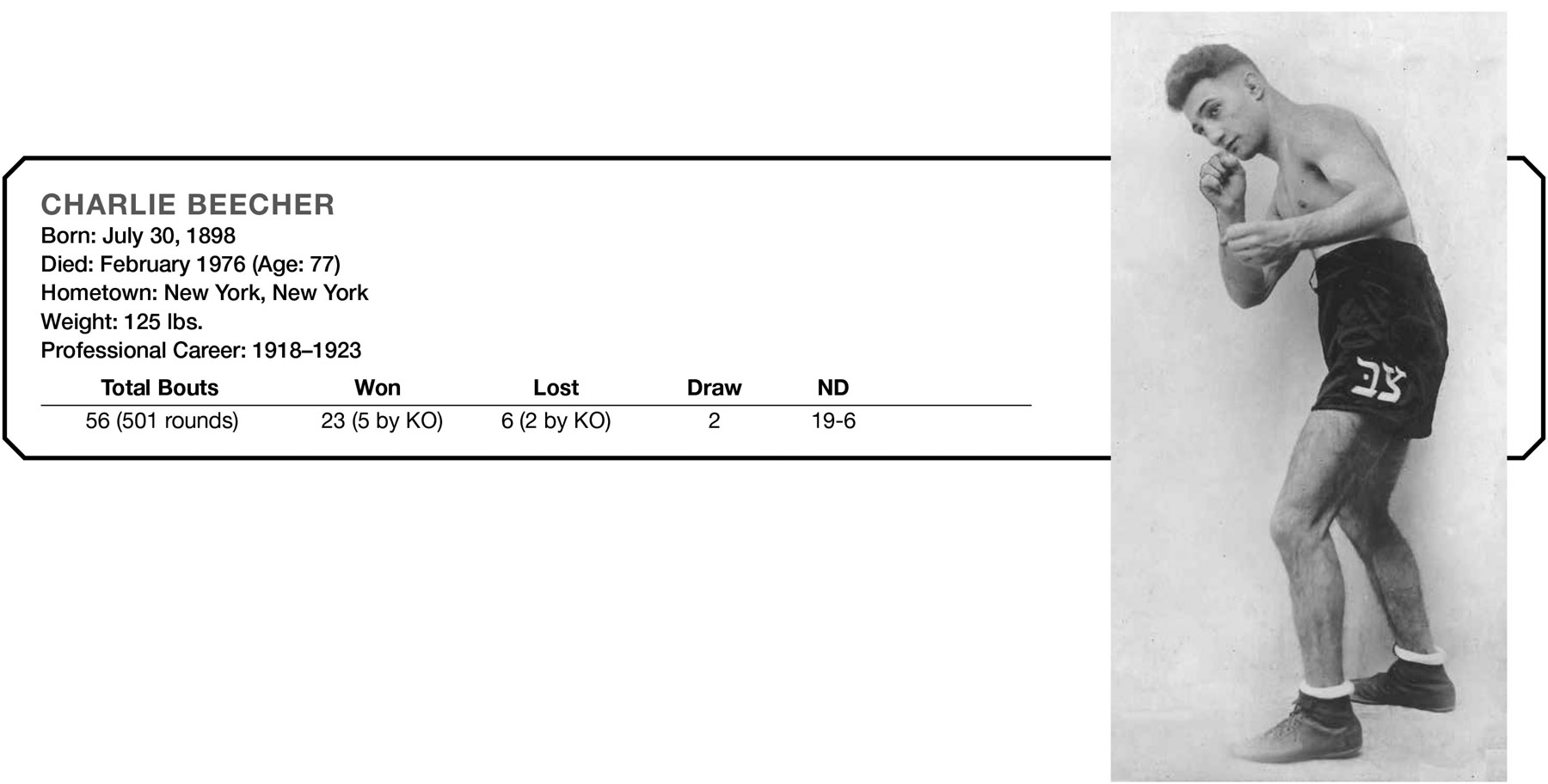

Charlie Beecher

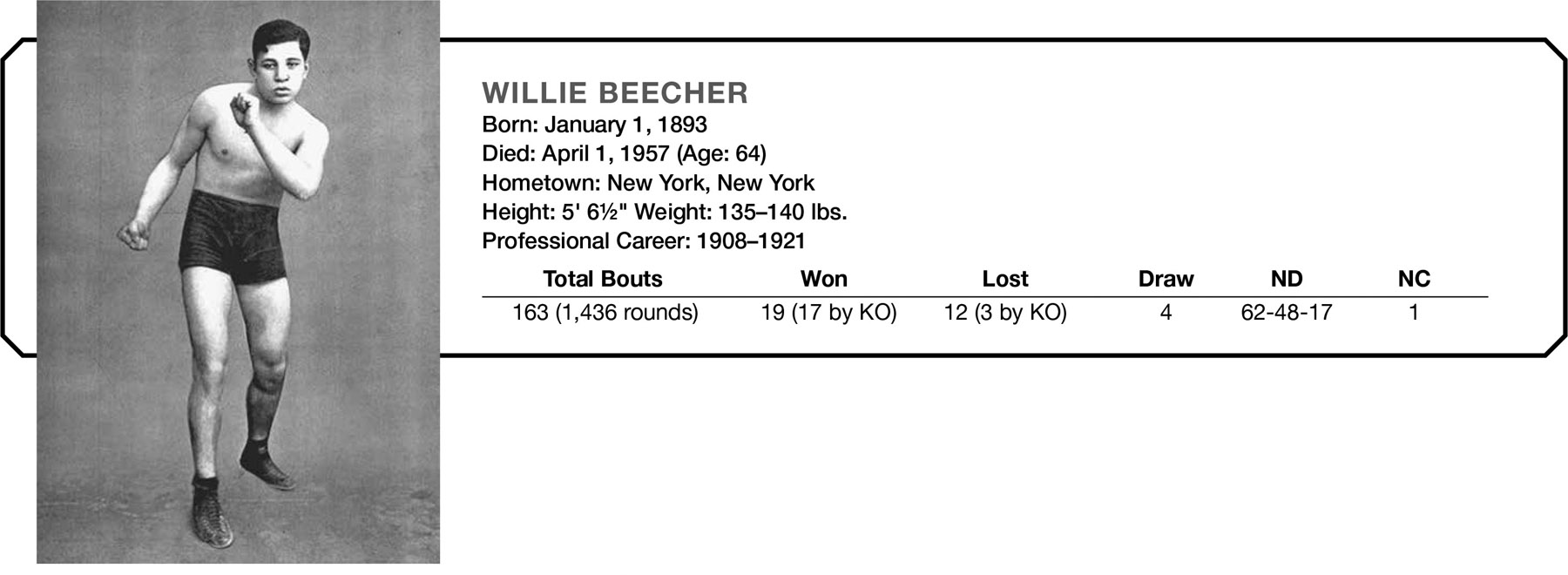

Willie Beecher

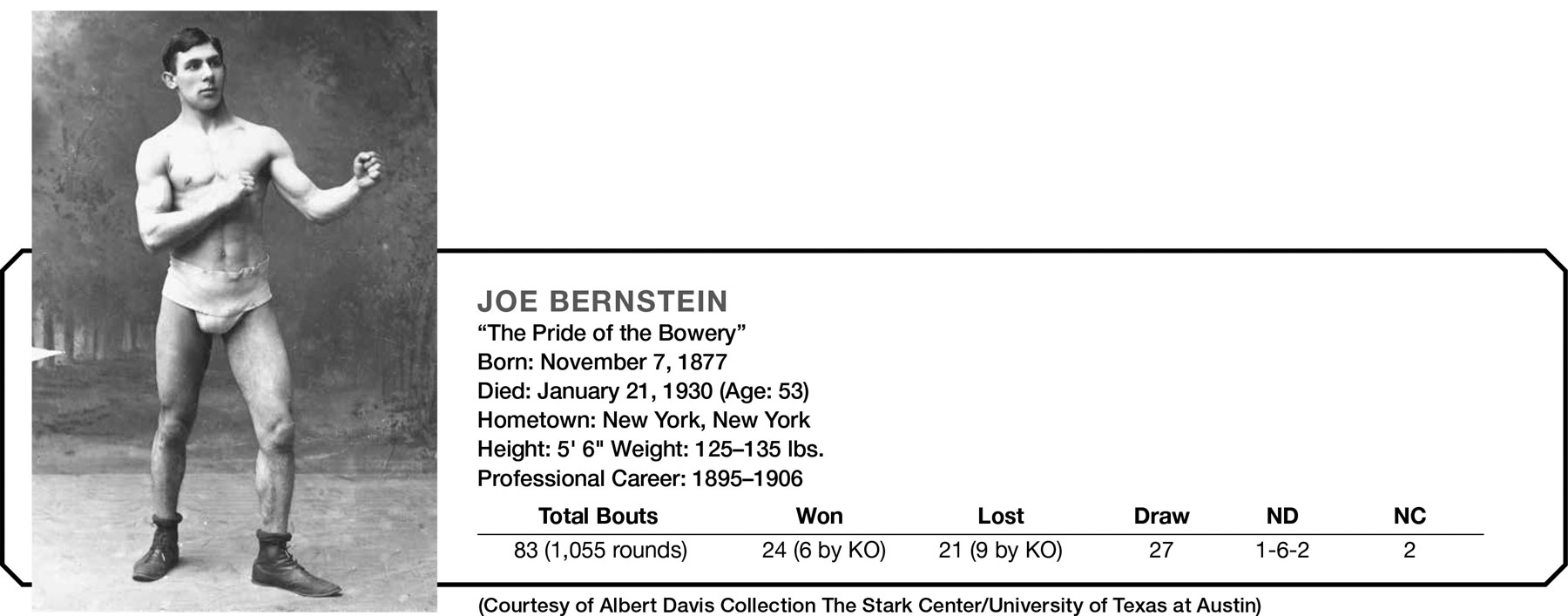

Joe Bernstein

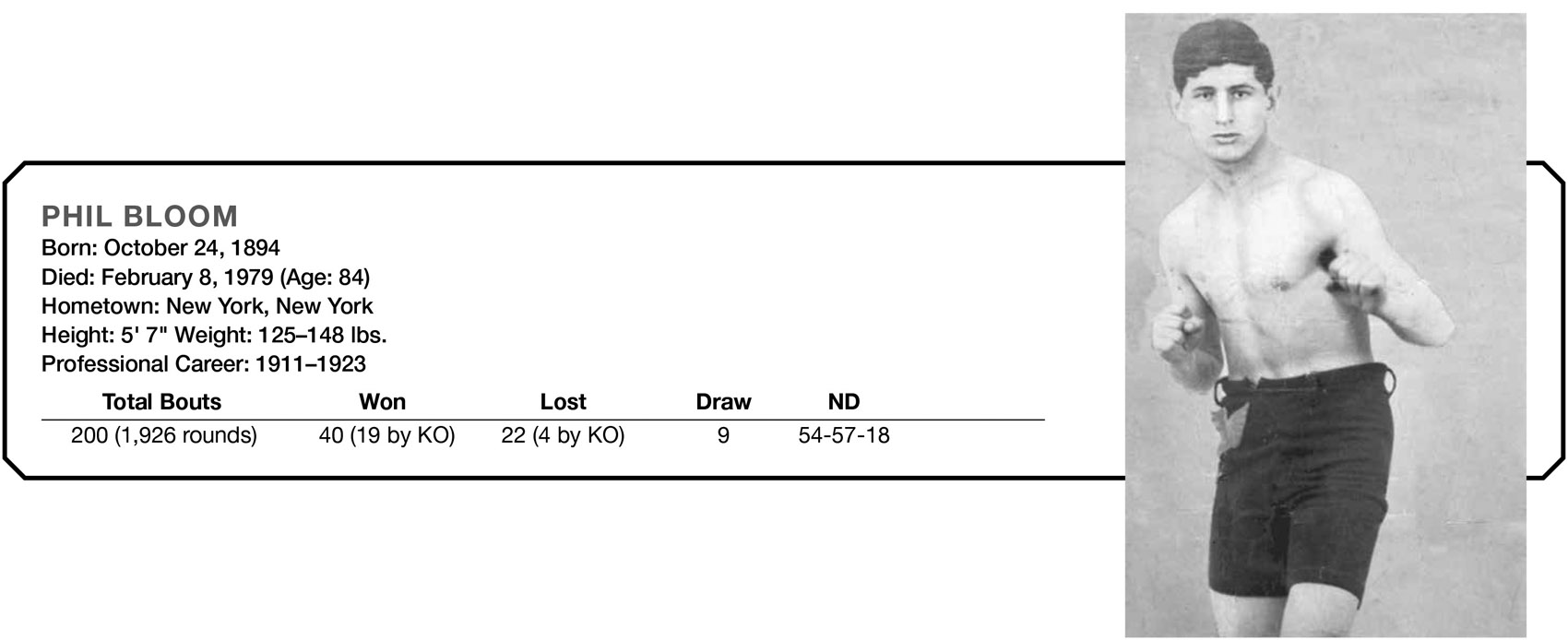

Phil Bloom

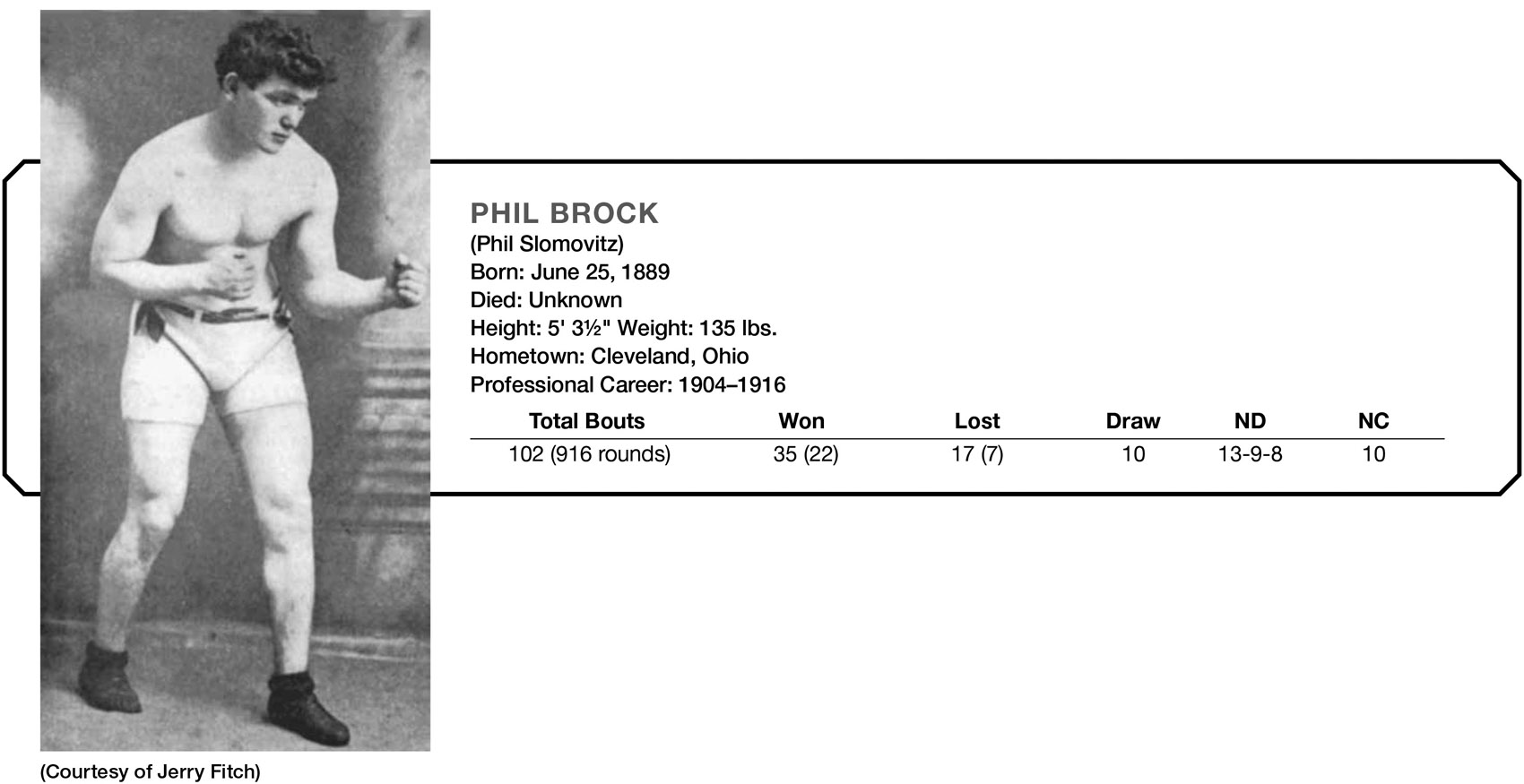

Phil Brock

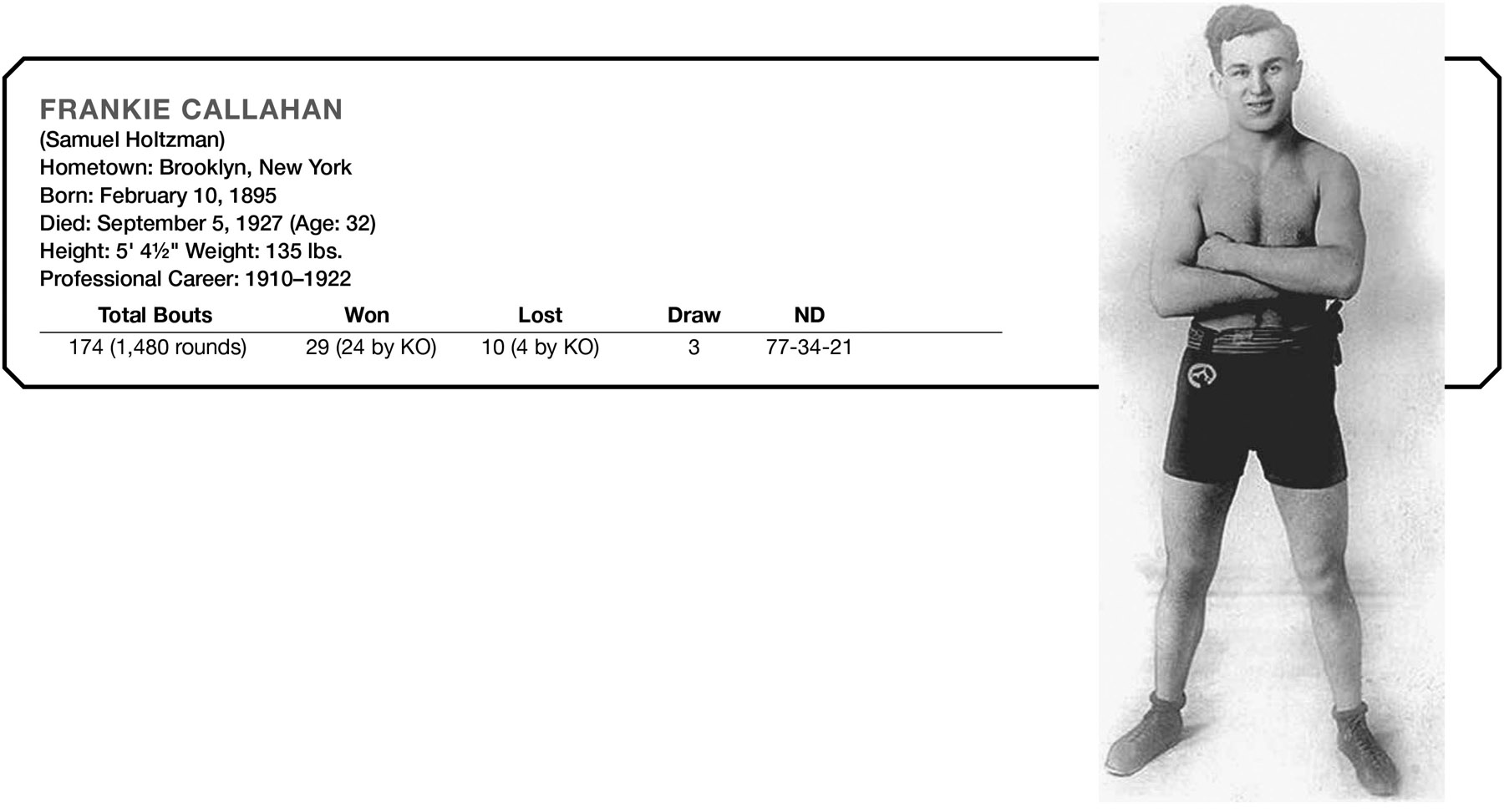

Frankie Callahan

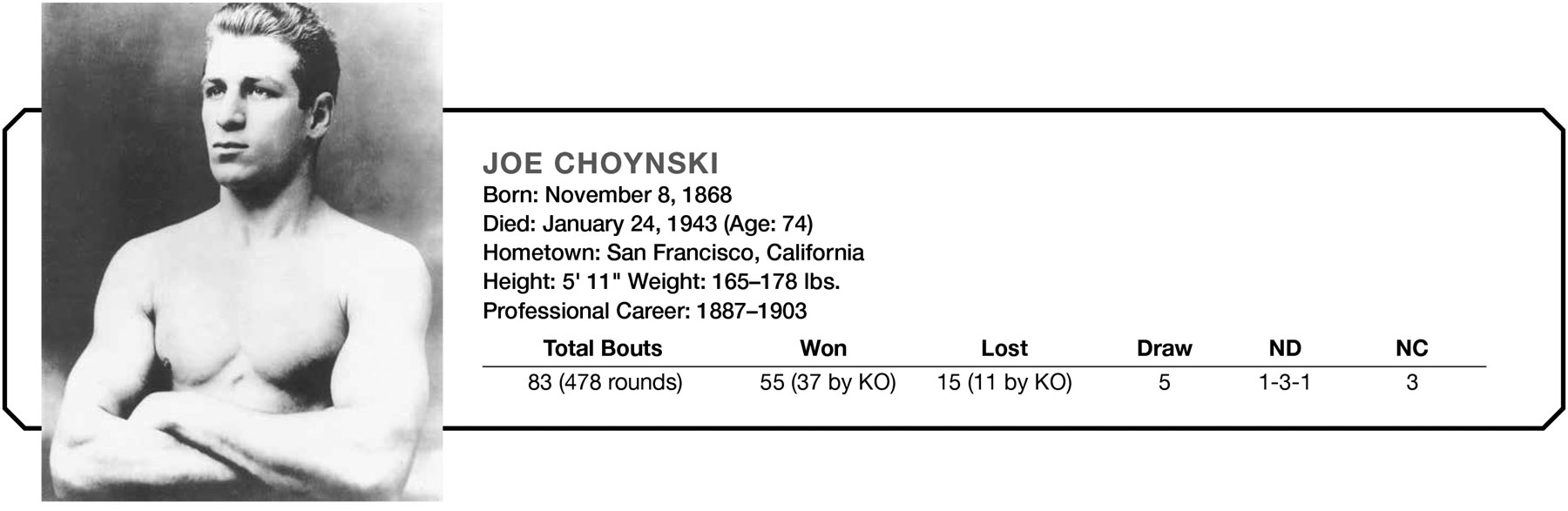

Joe Choynski

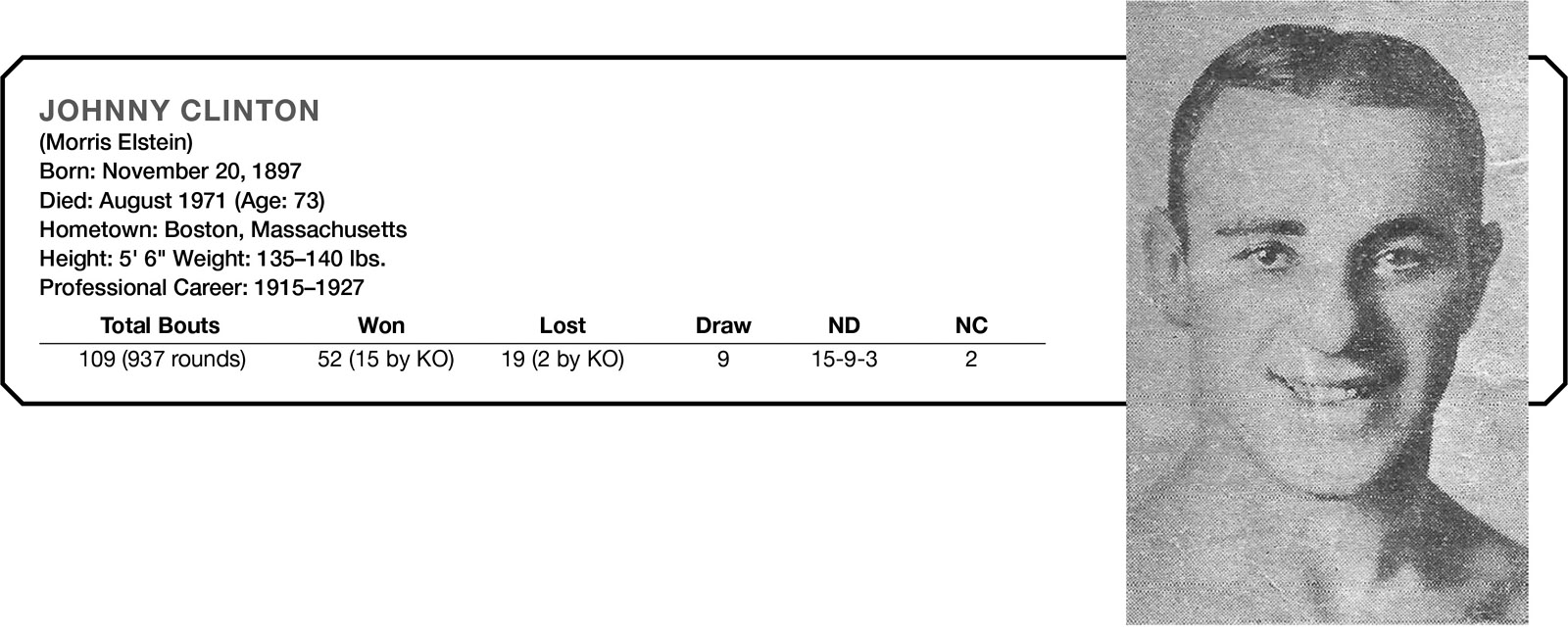

Johnny Clinton

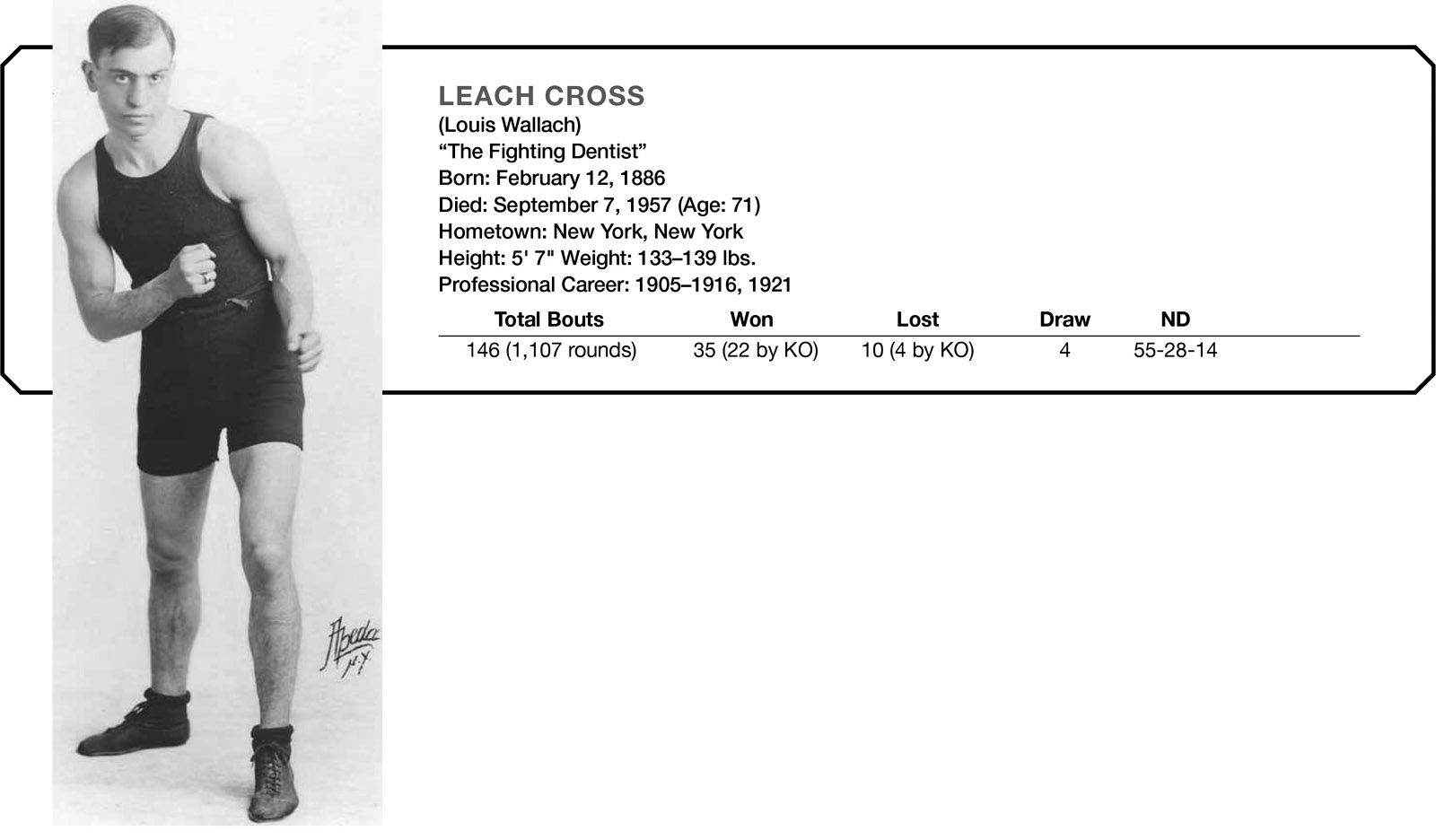

Leach Cross

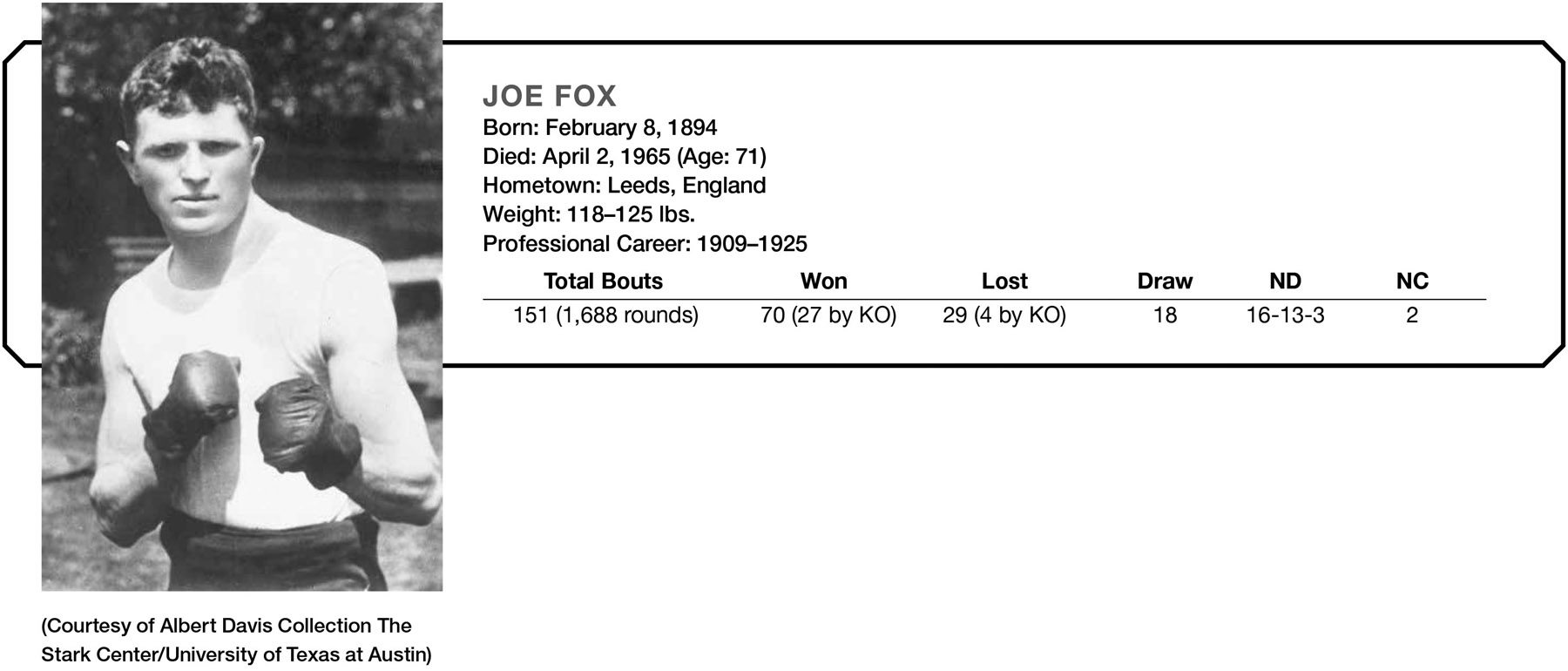

Joe Fox

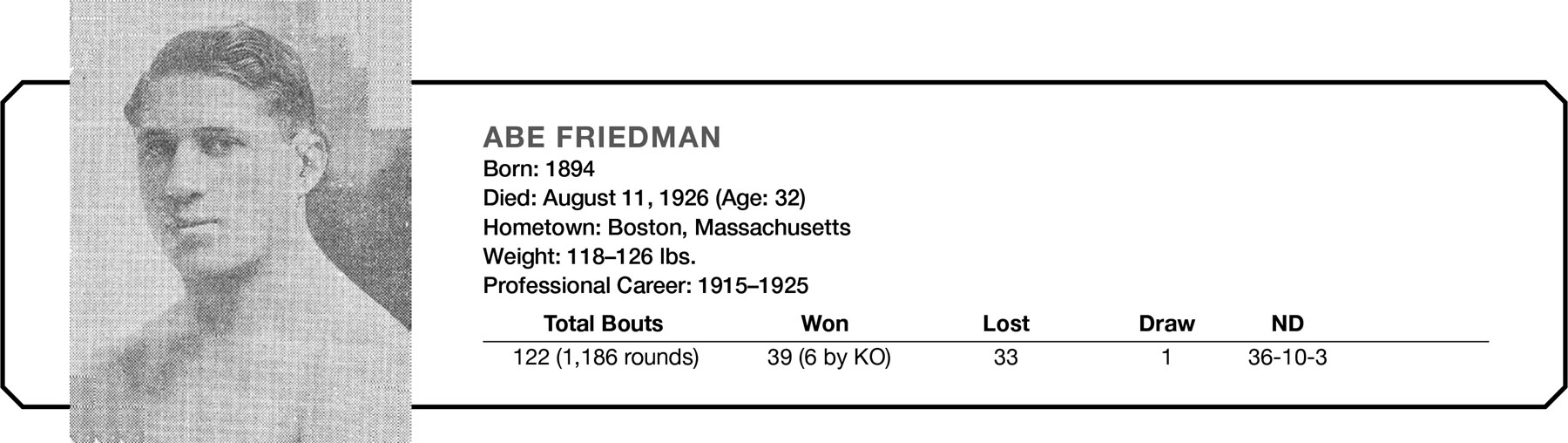

Abe Friedman

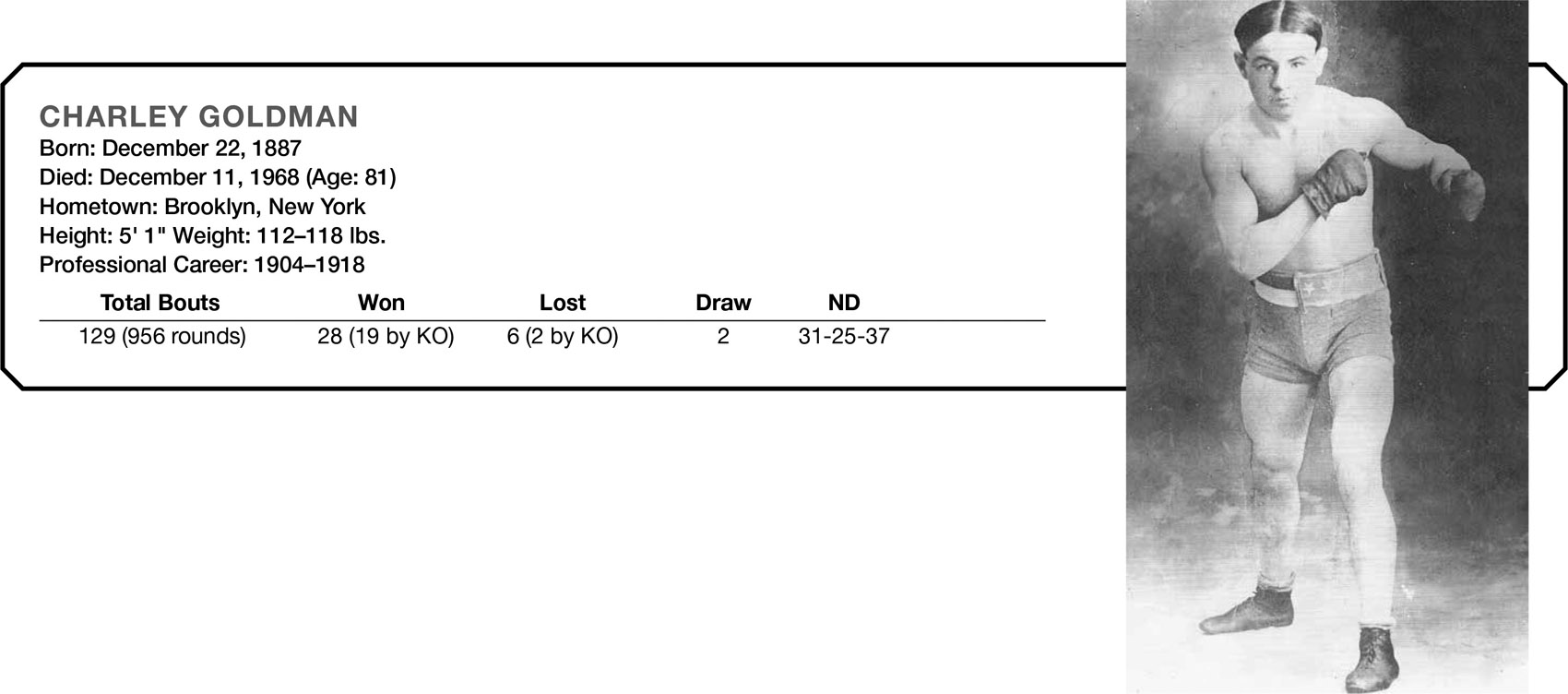

Charley Goldman

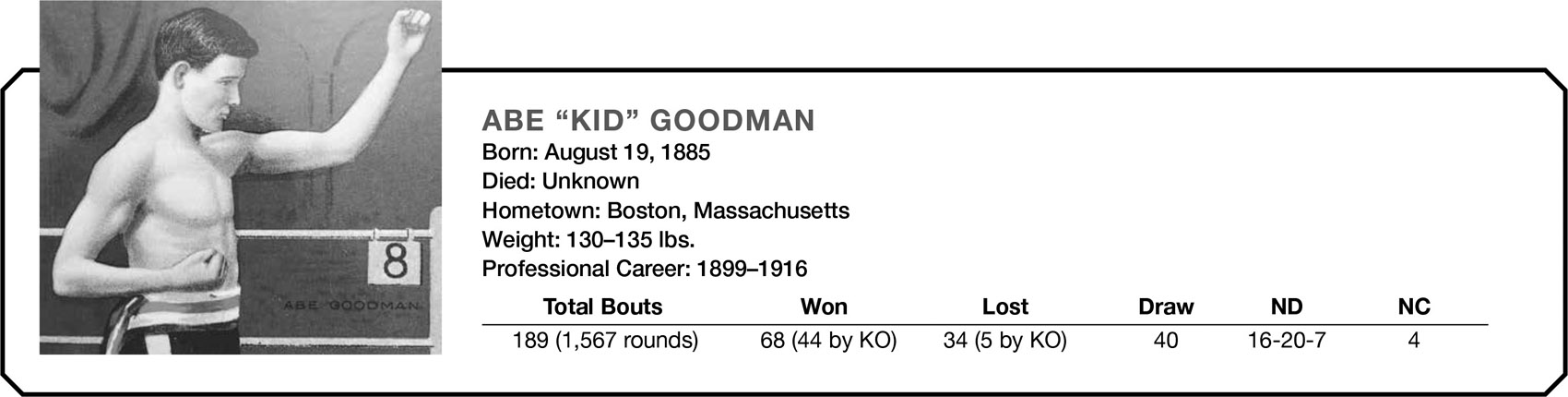

Abe “Kid” Goodman

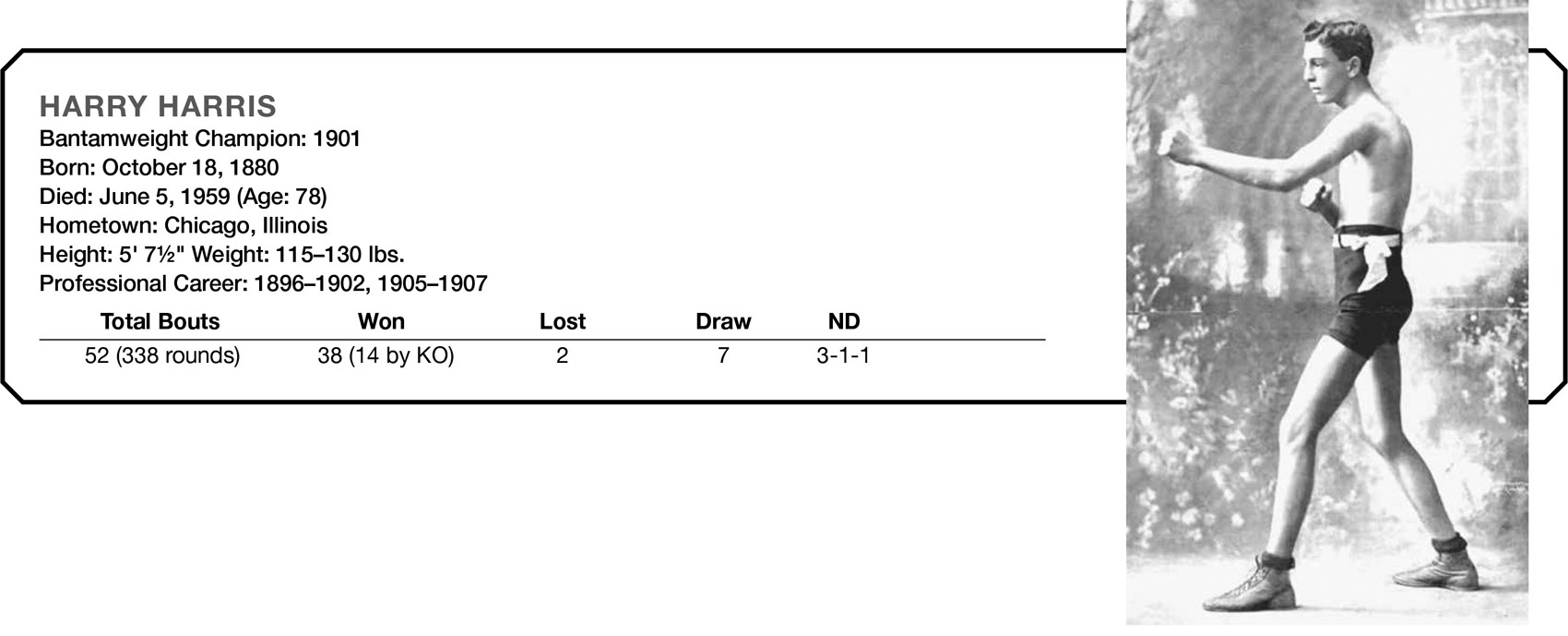

Harry Harris*

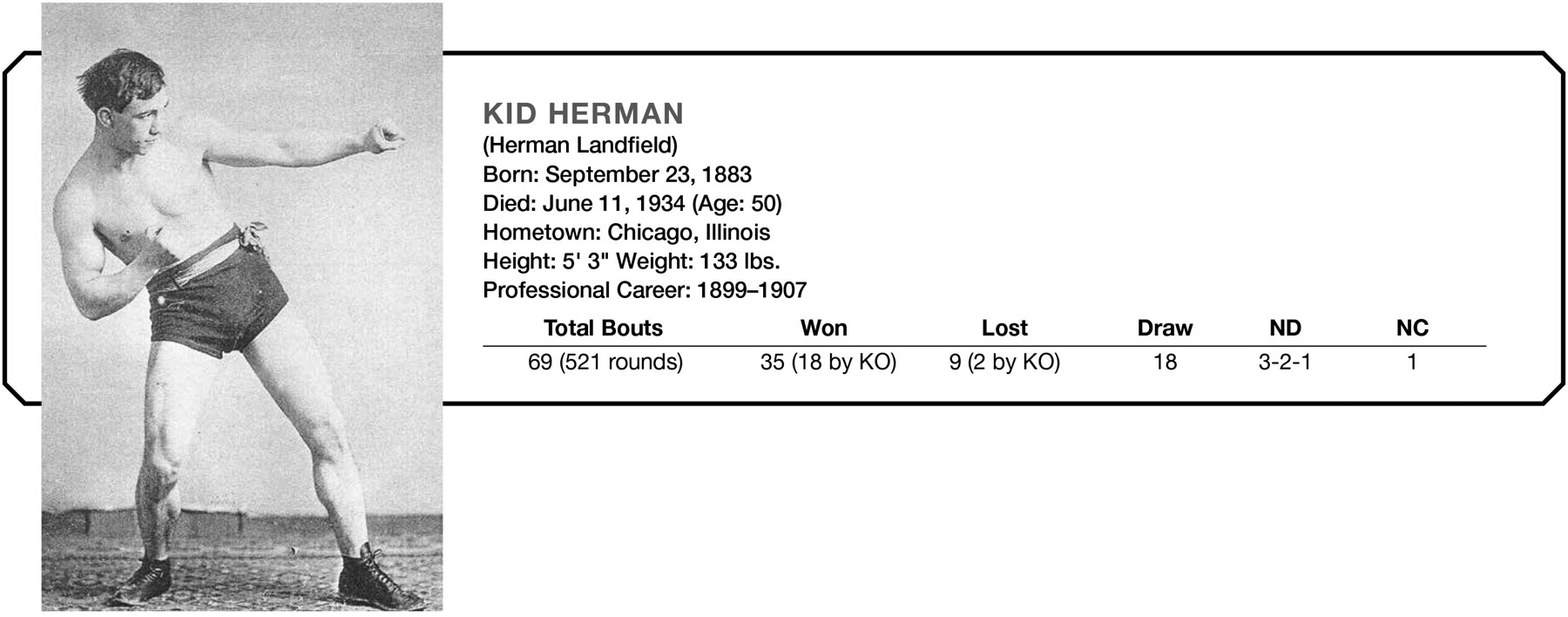

Kid Herman

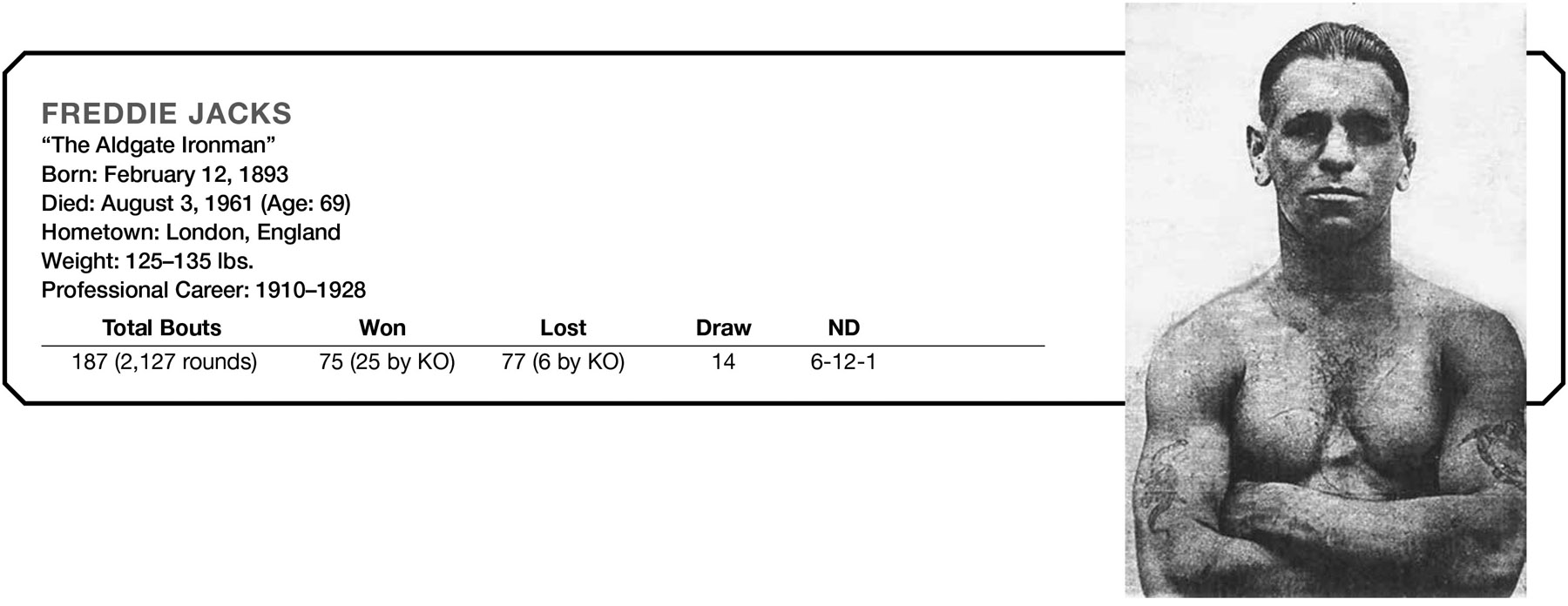

Freddie Jacks

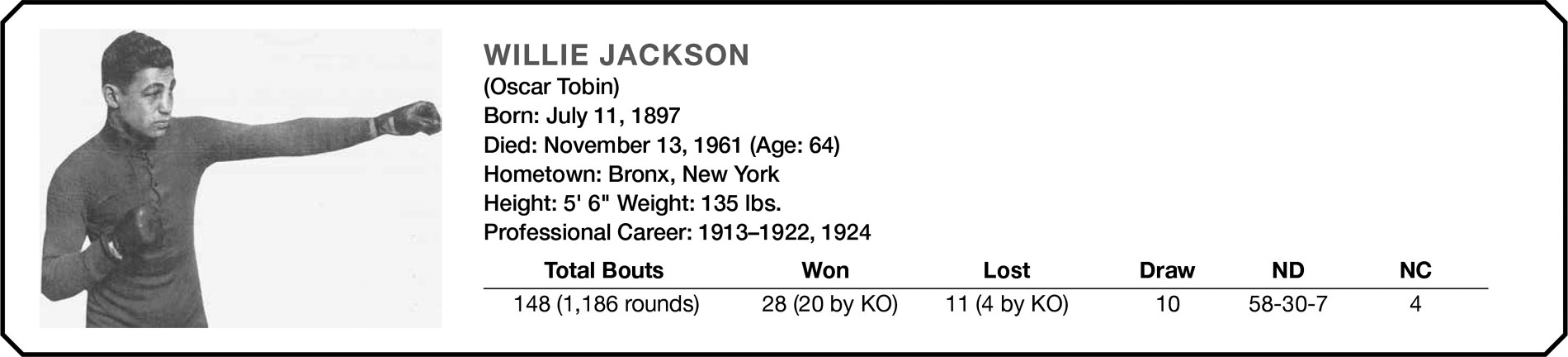

Willie Jackson

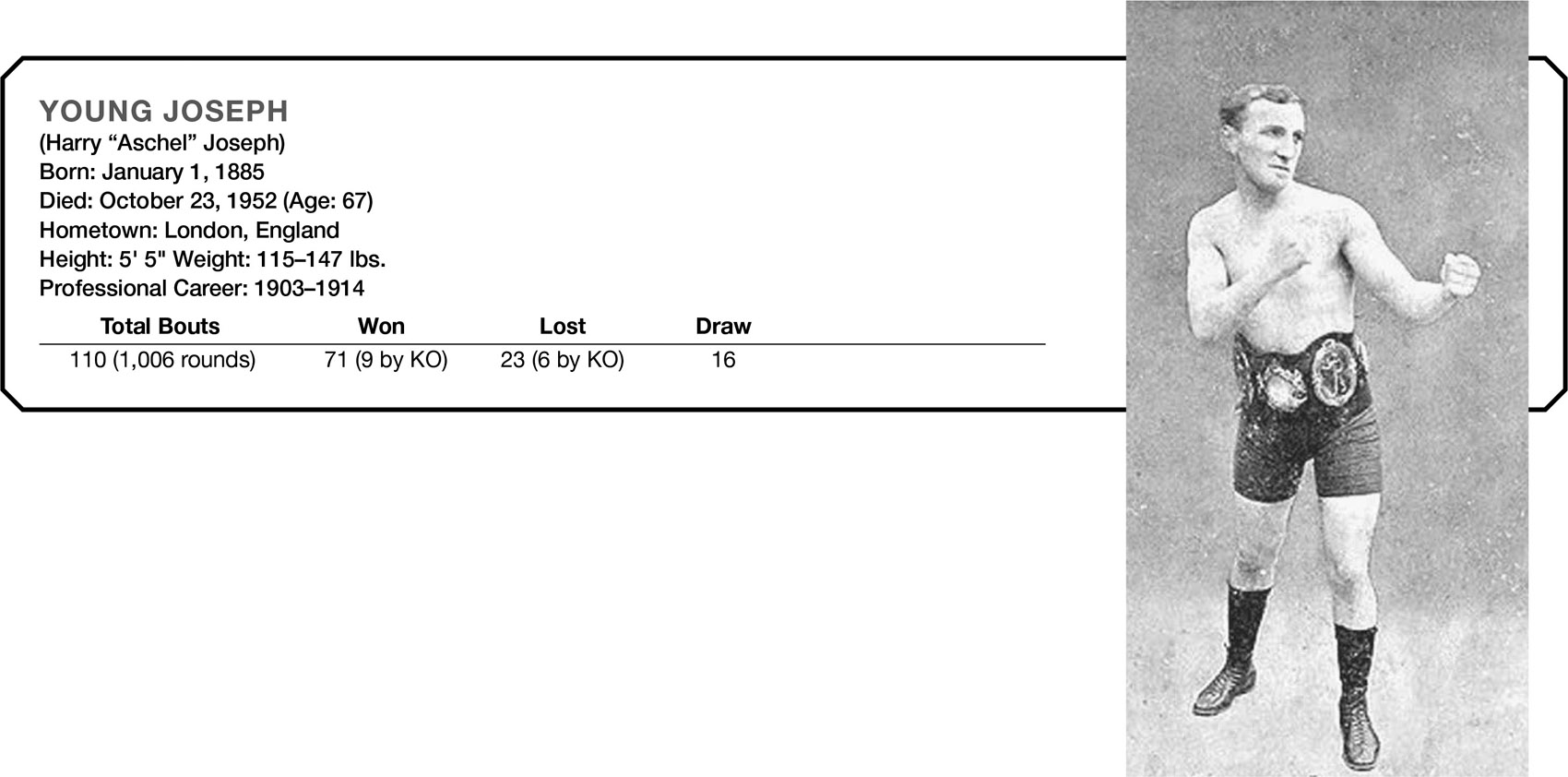

Young Joseph

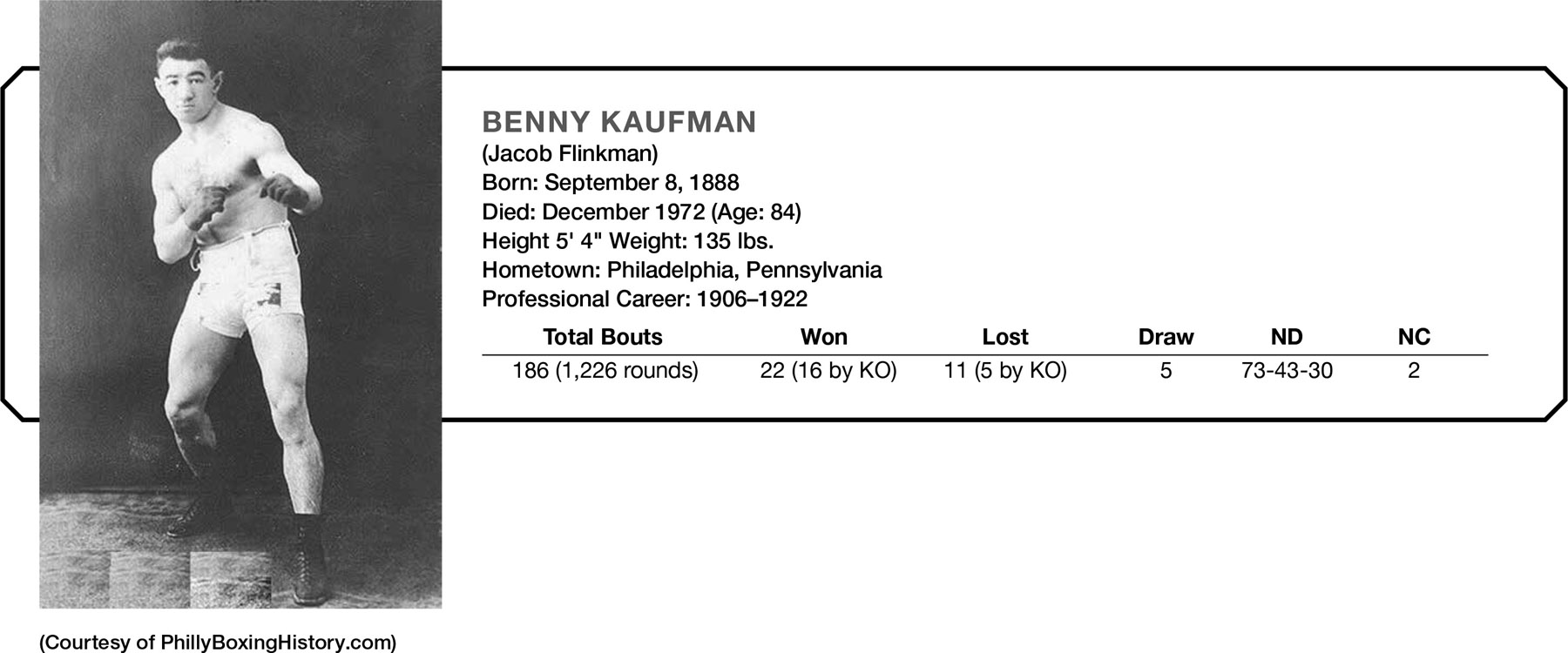

Benny Kaufman

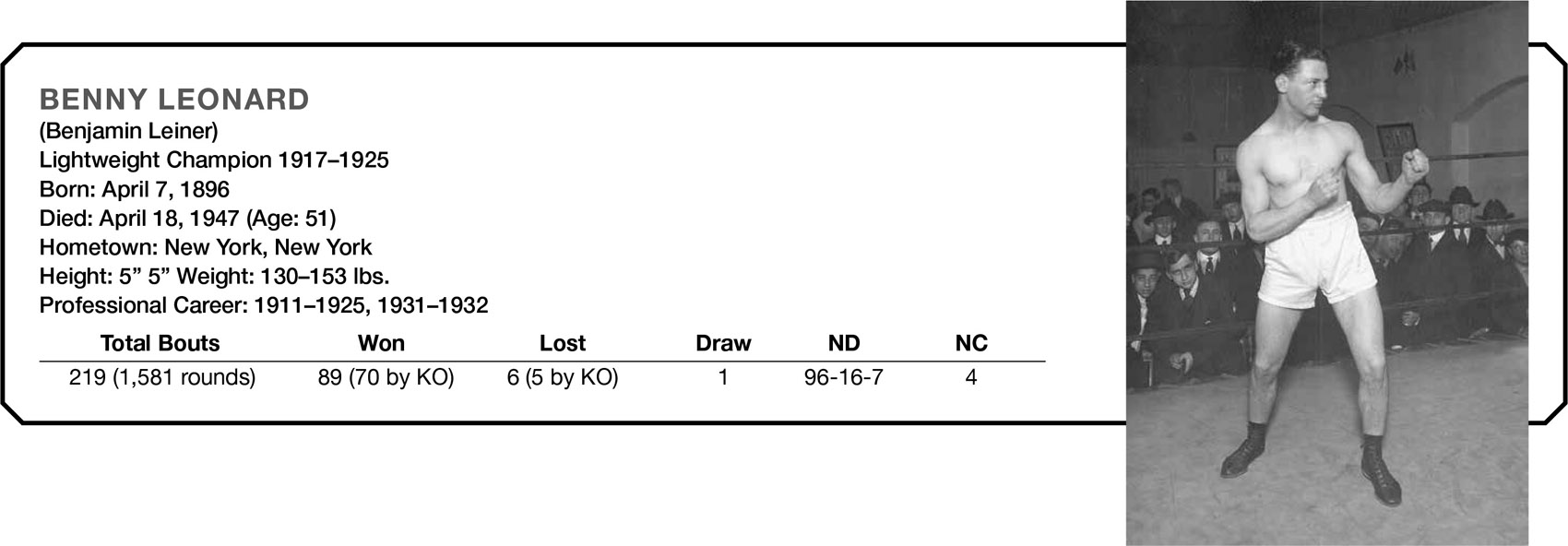

Benny Leonard*

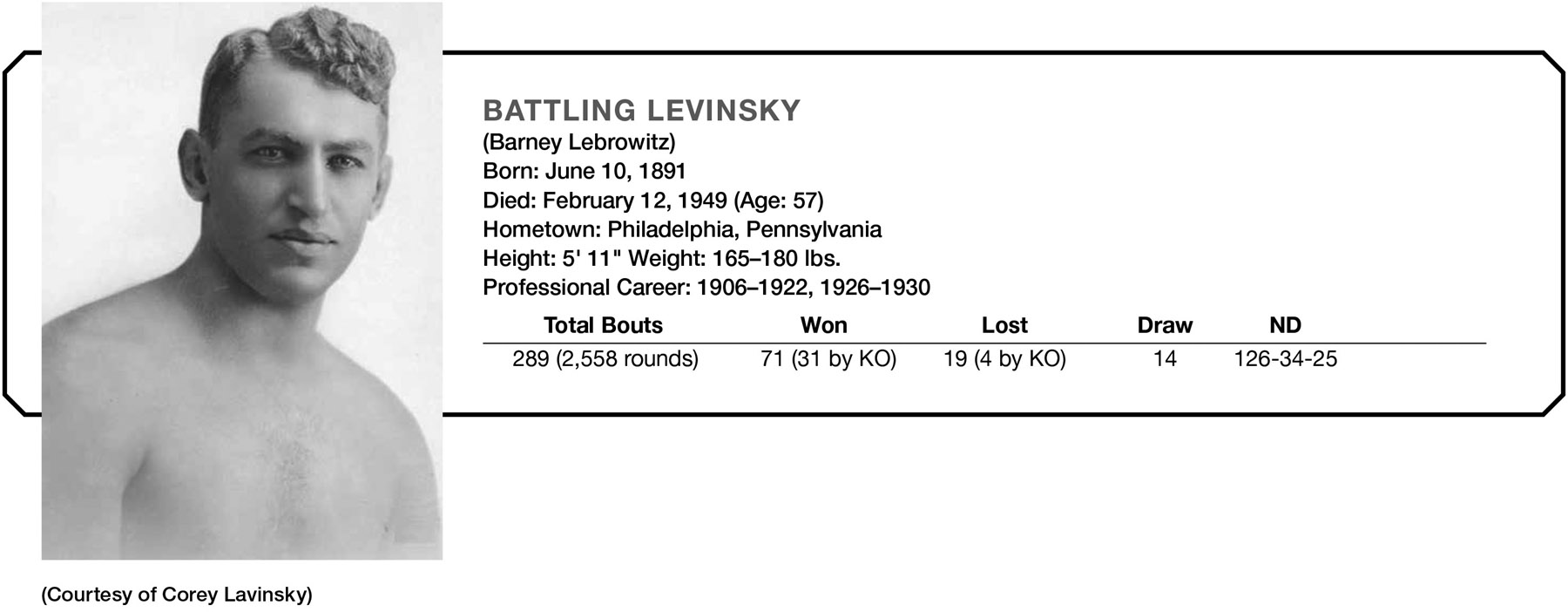

Battling Levinsky*

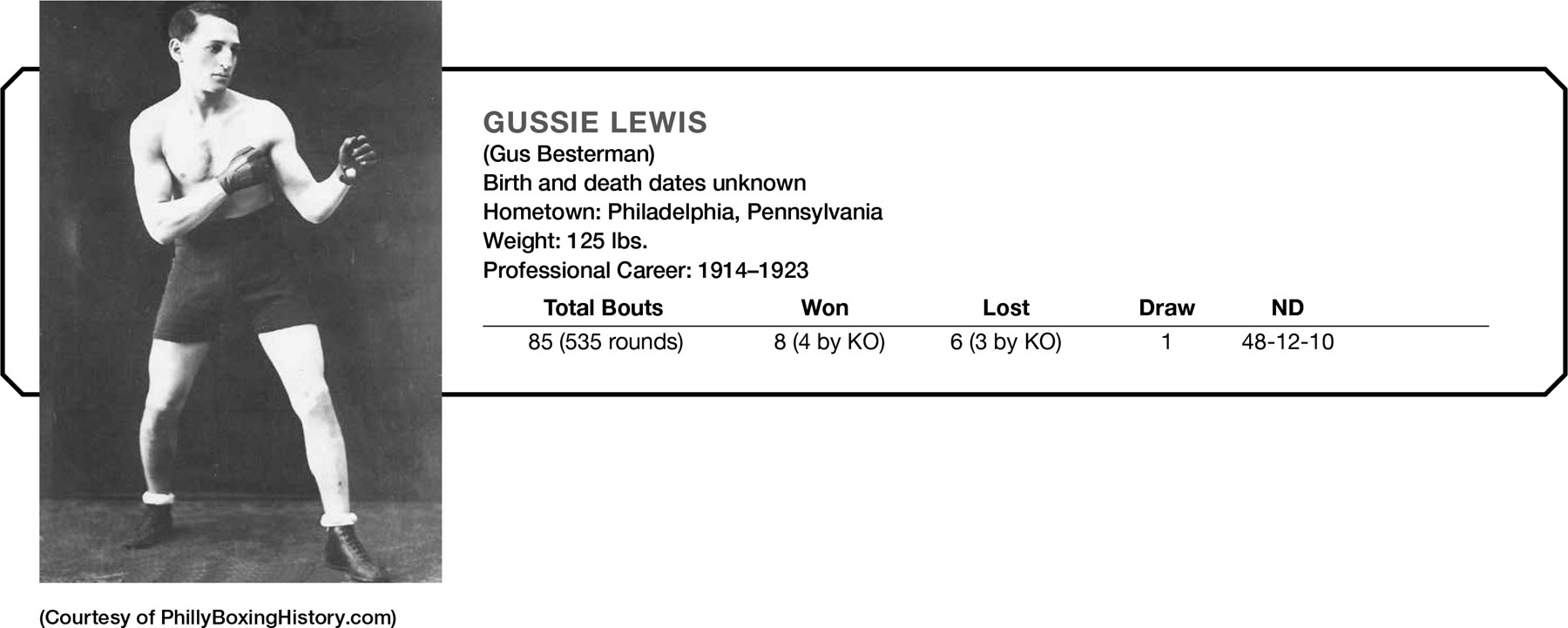

Gussie Lewis

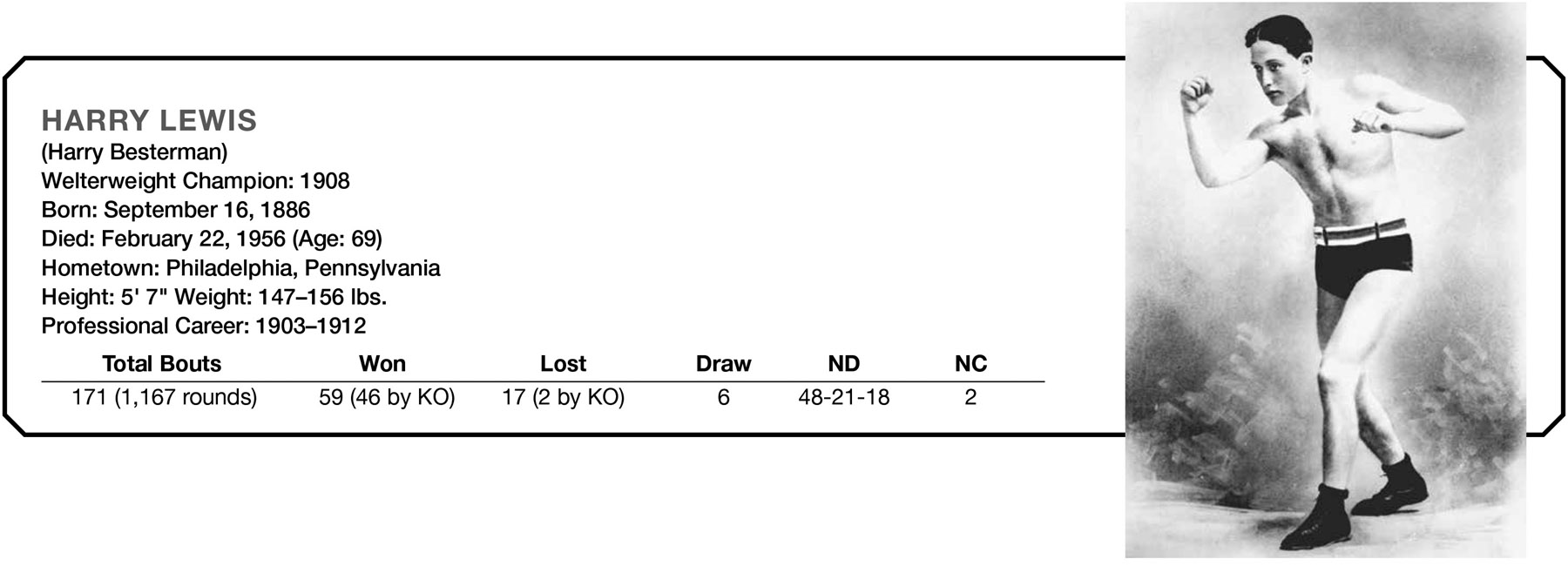

Harry Lewis*

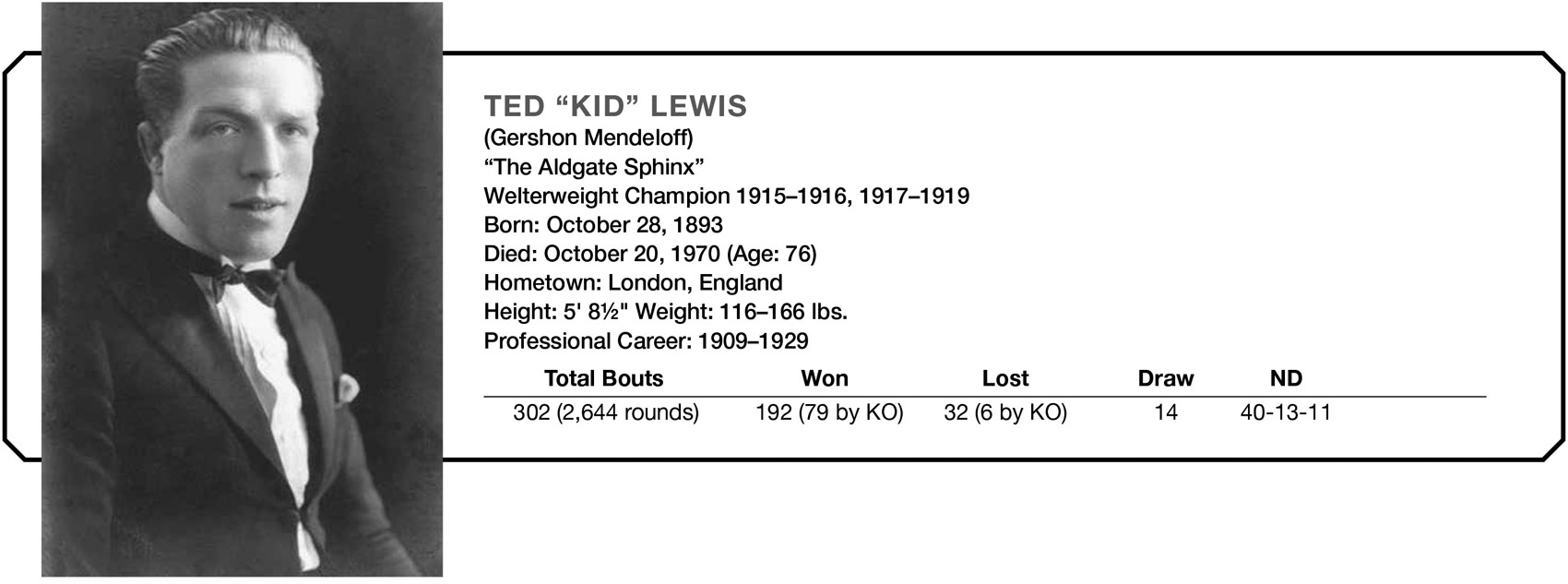

Ted “Kid” Lewis*

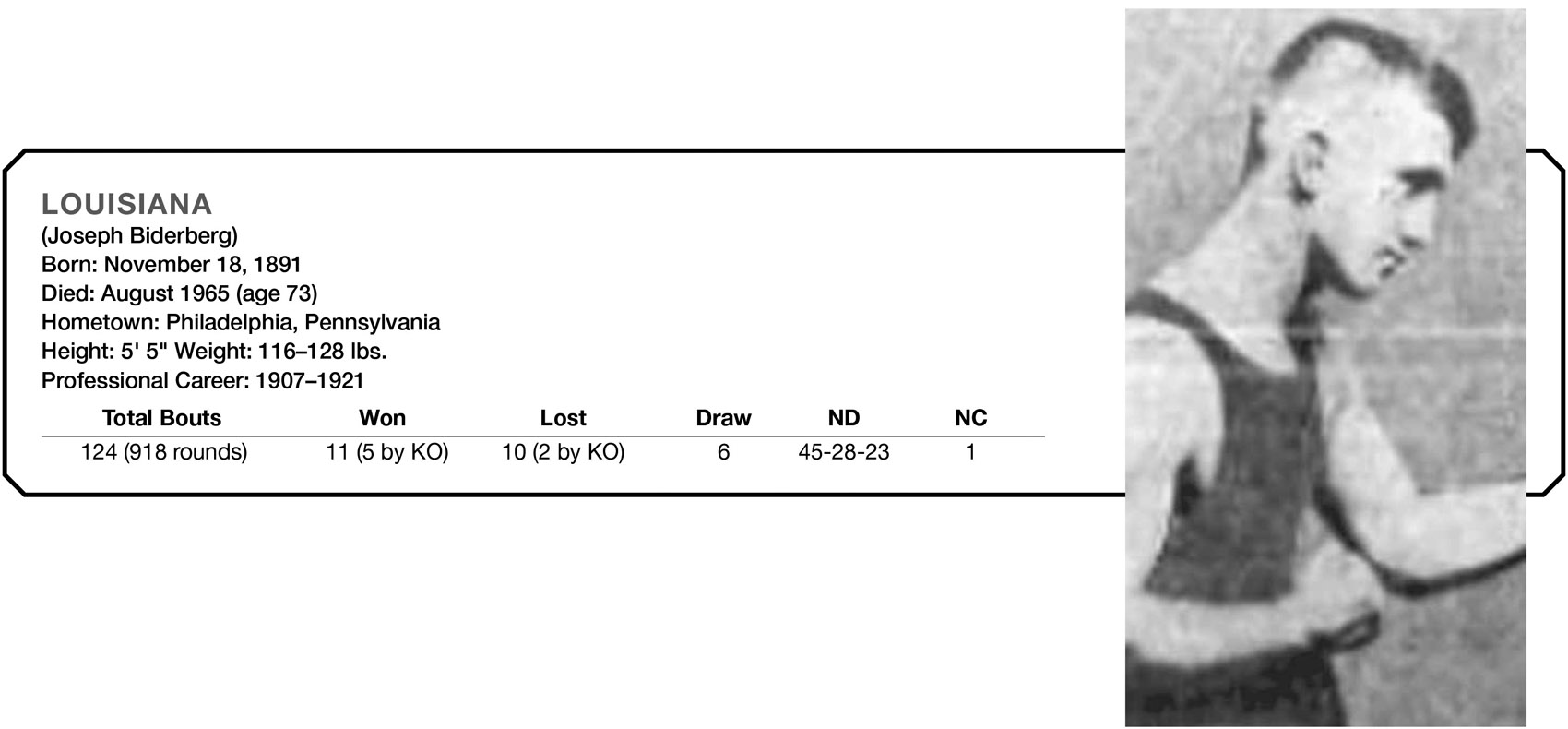

Louisiana

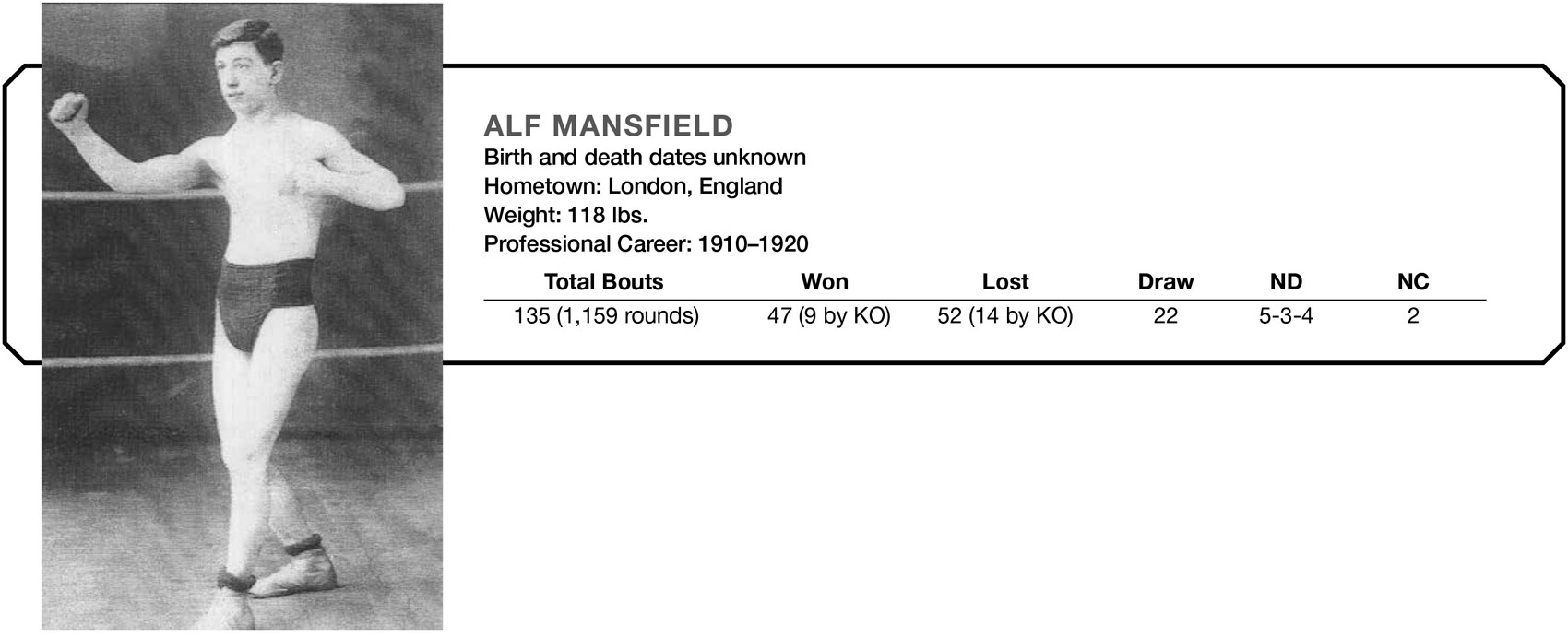

Alf Mansfield

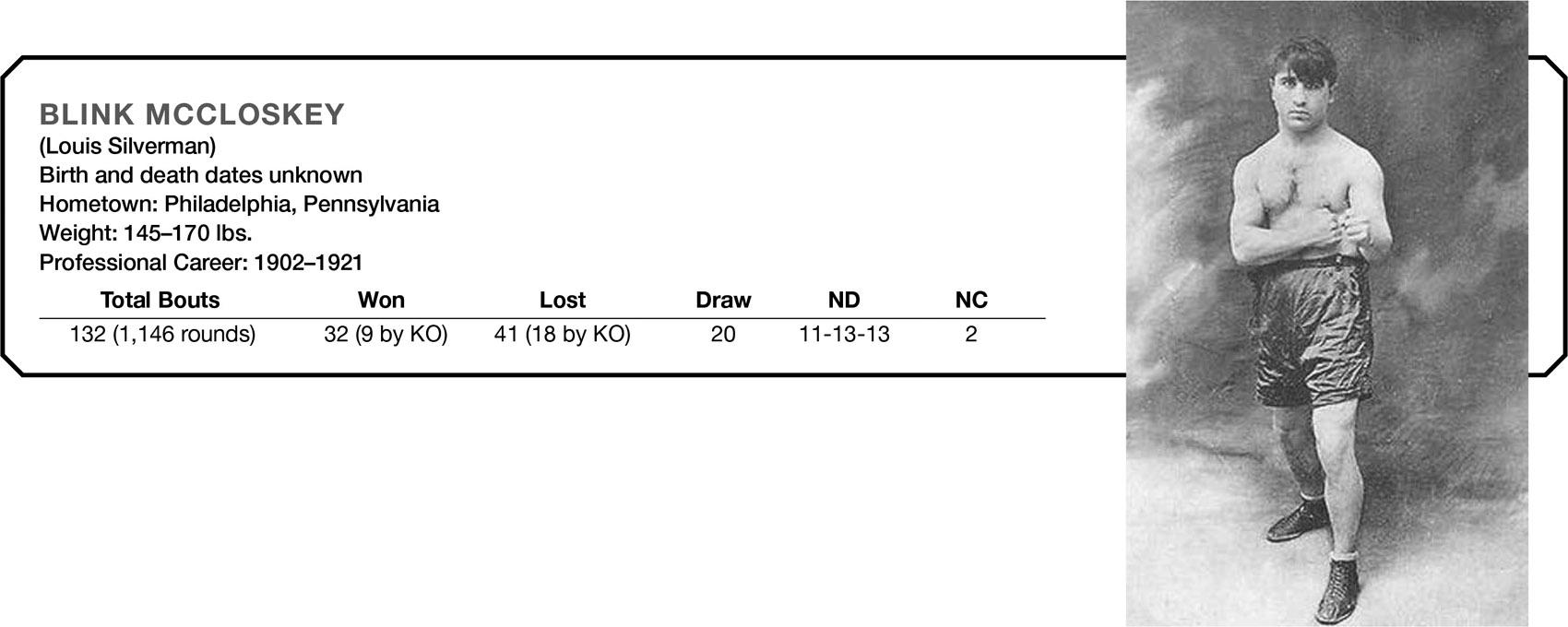

Blink McCloskey

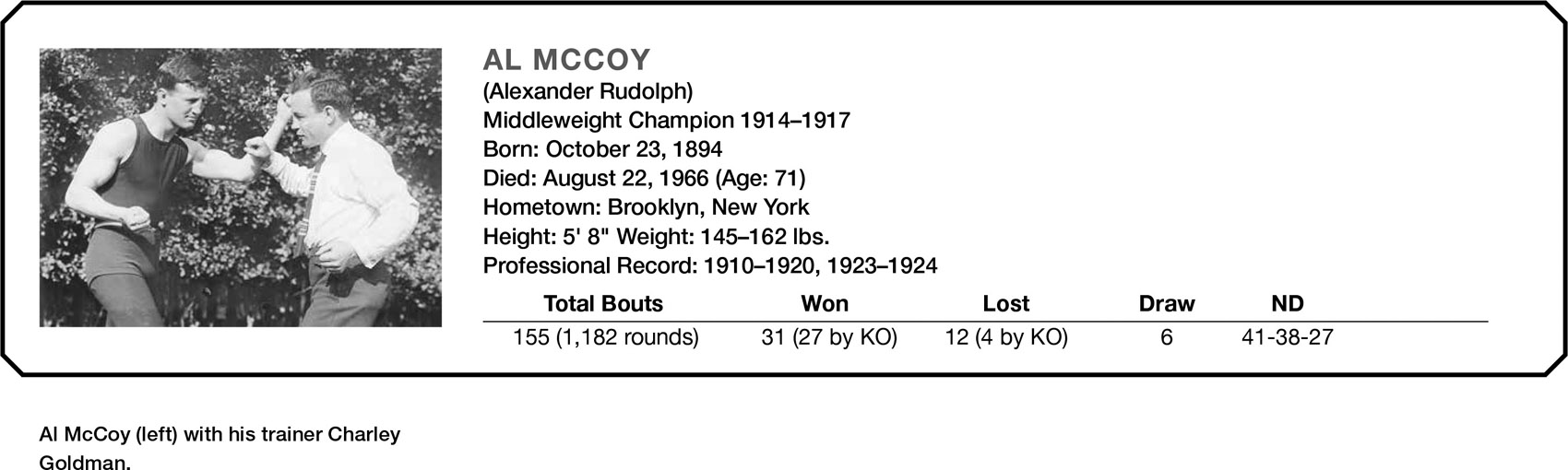

Al McCoy

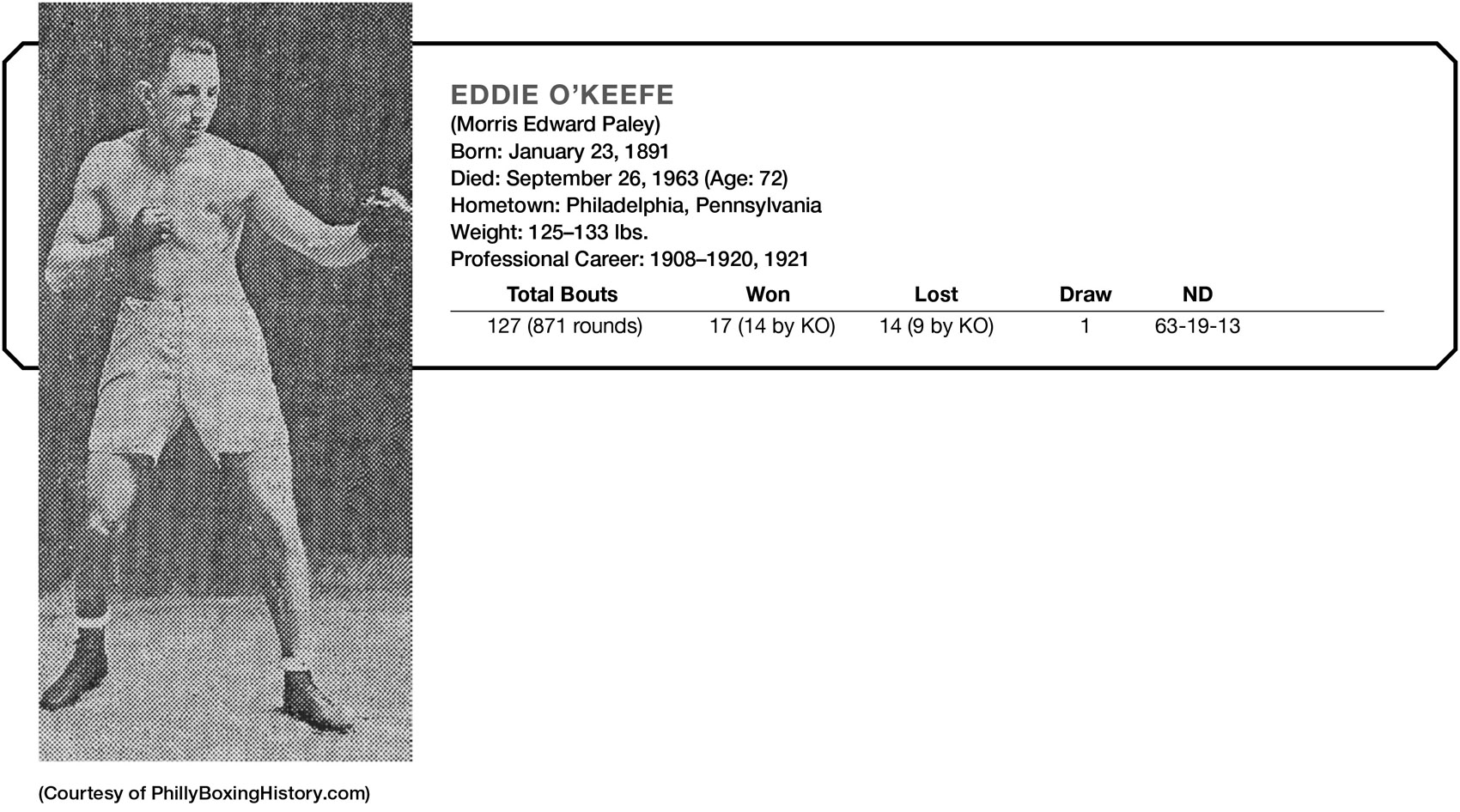

Eddie O’Keefe

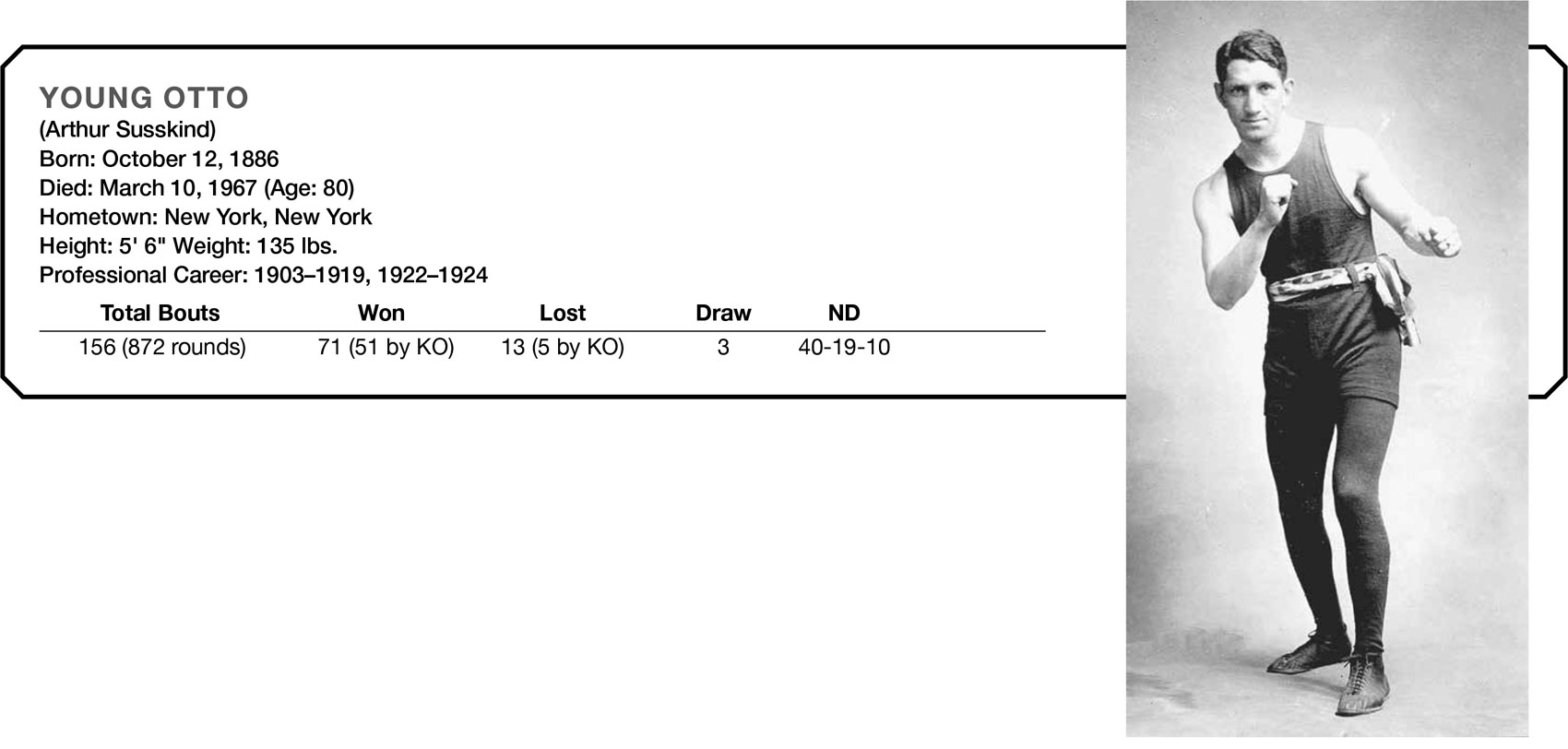

Young Otto

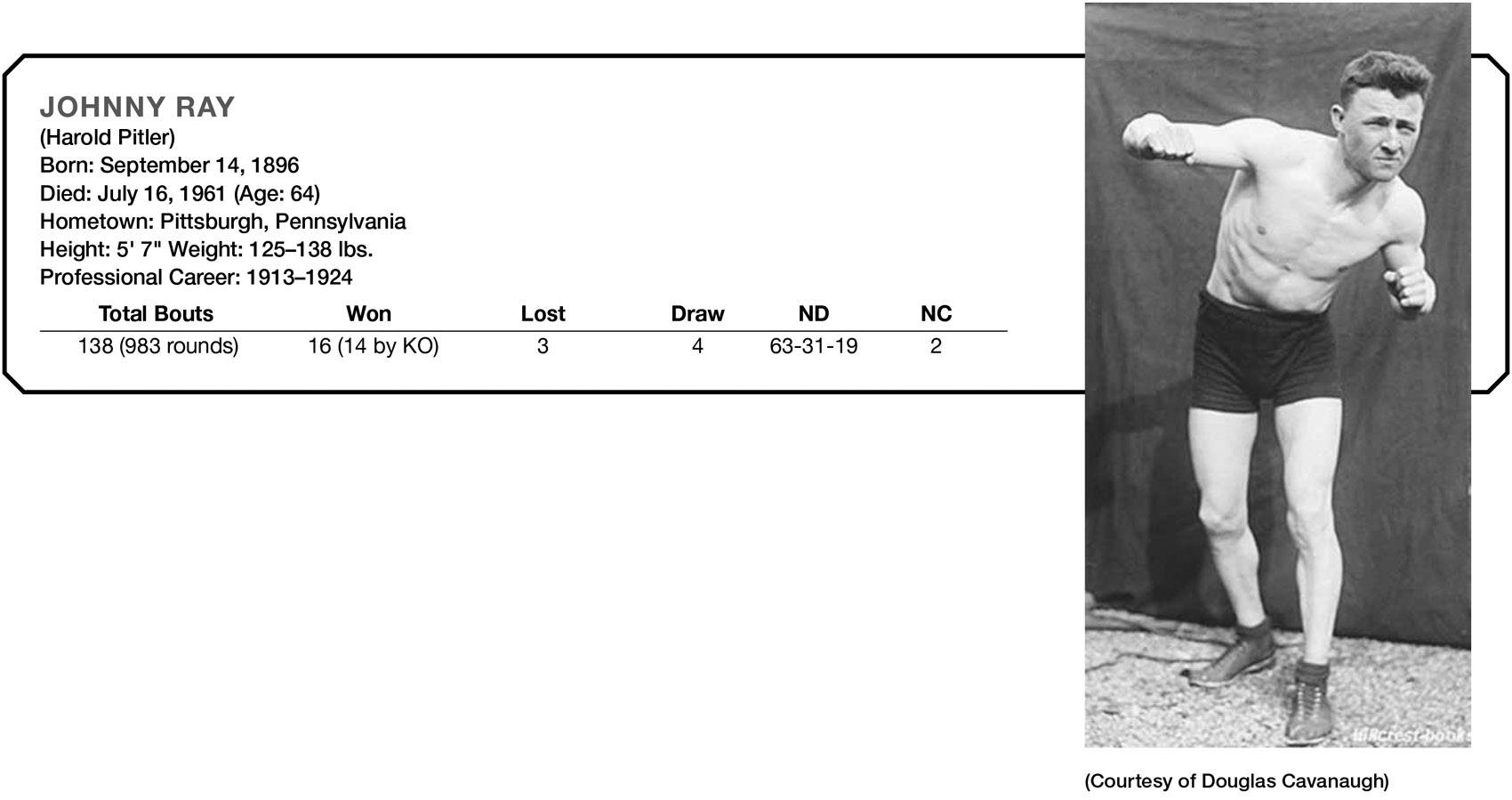

Johnny Ray

Johnny Rosner

Yankee Schwartz

Jewey Smith

Sammy Smith

Sid Smith*

Harry Stone

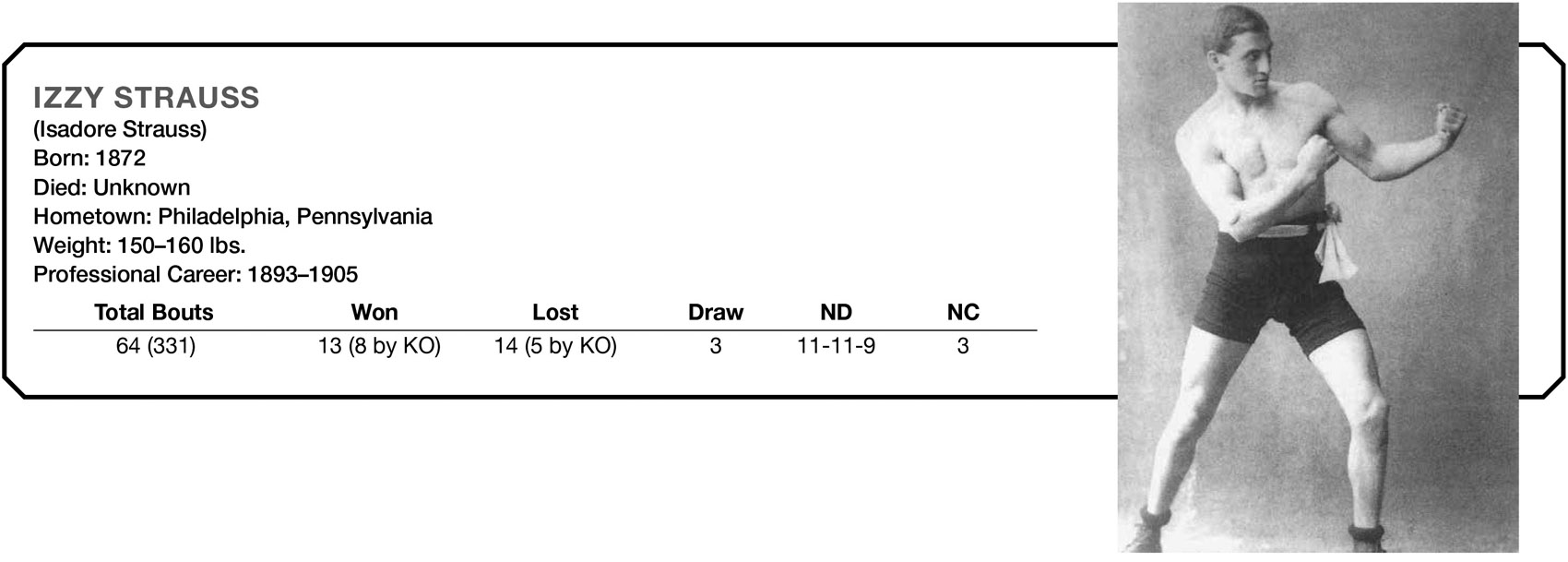

Izzy Strauss

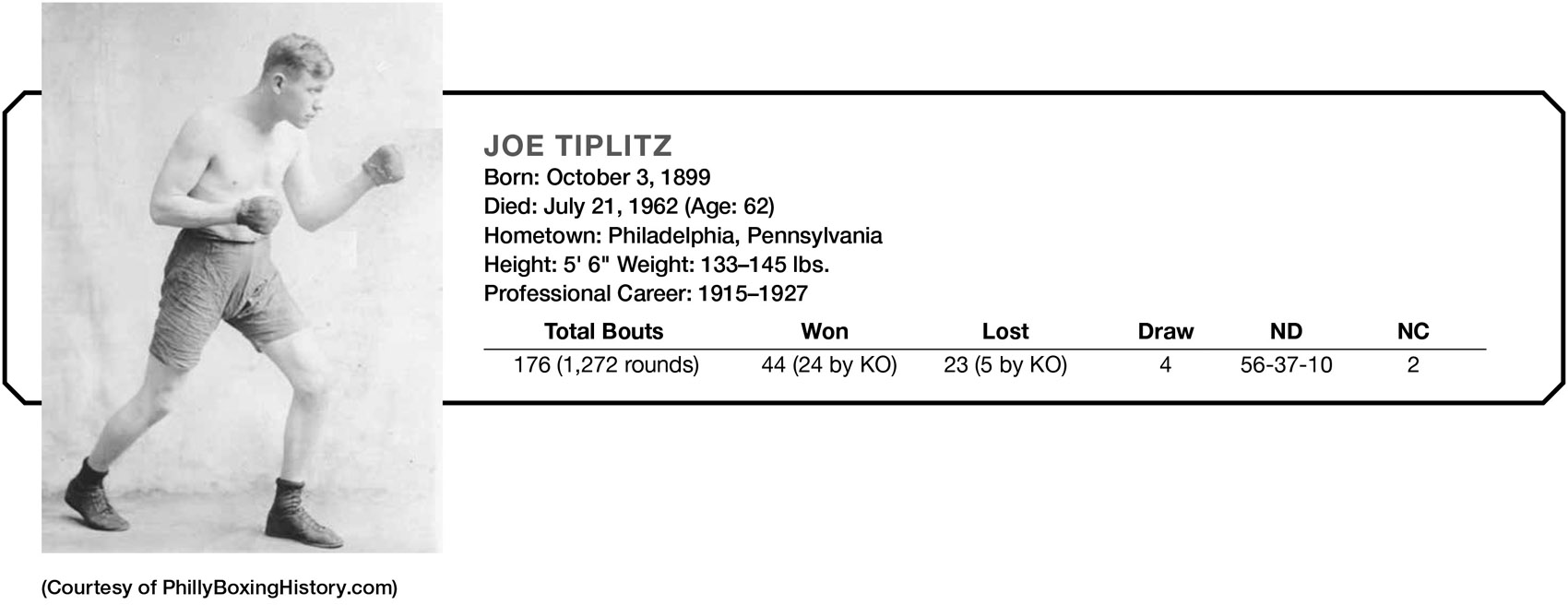

Joe Tiplitz

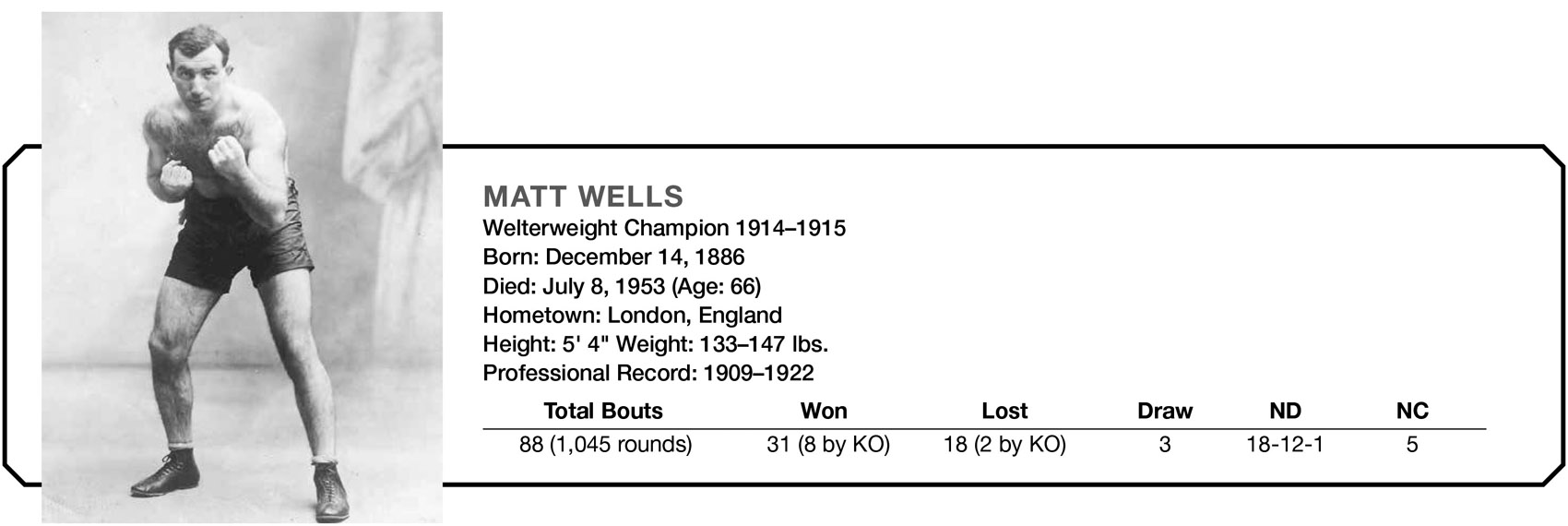

Matt Wells*

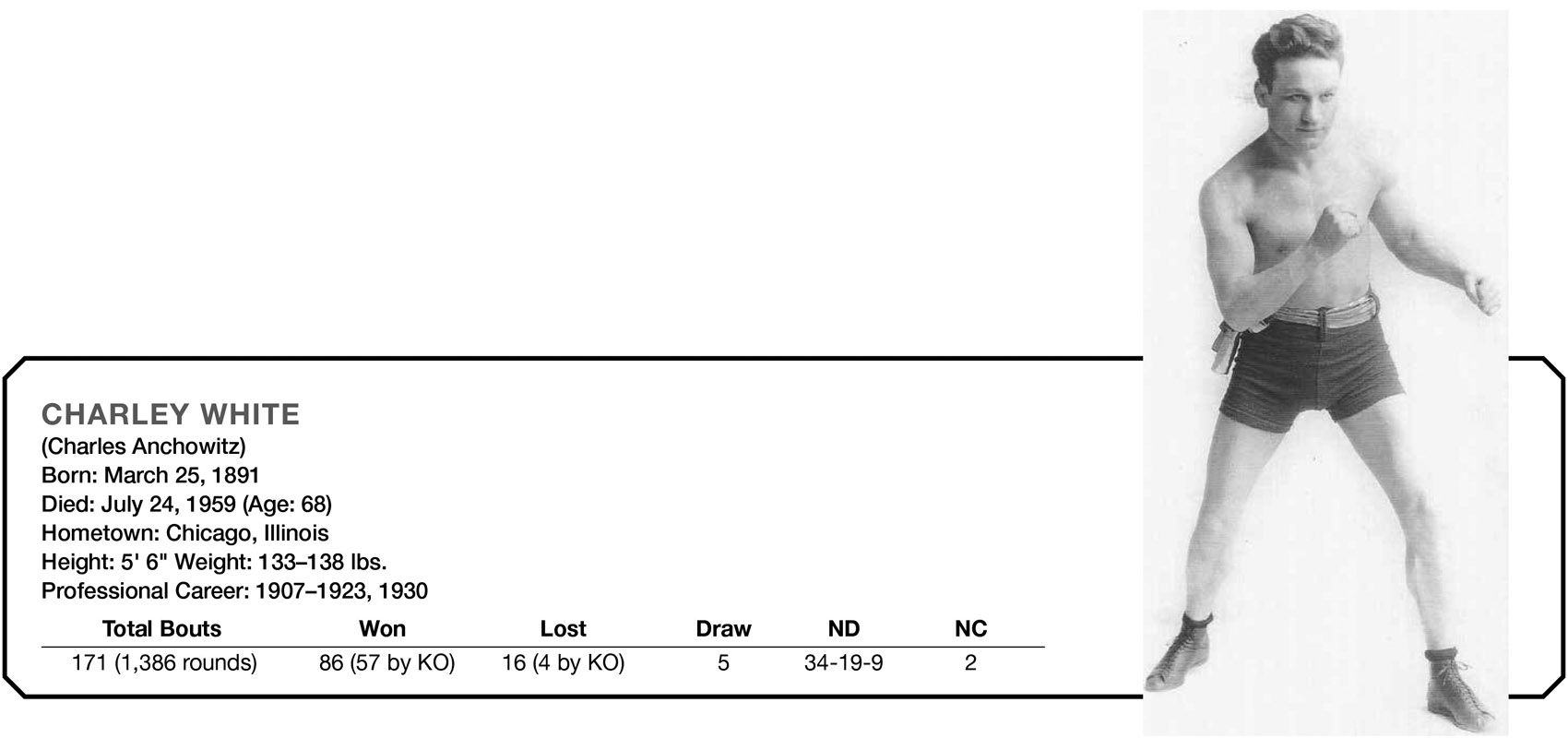

Charley White

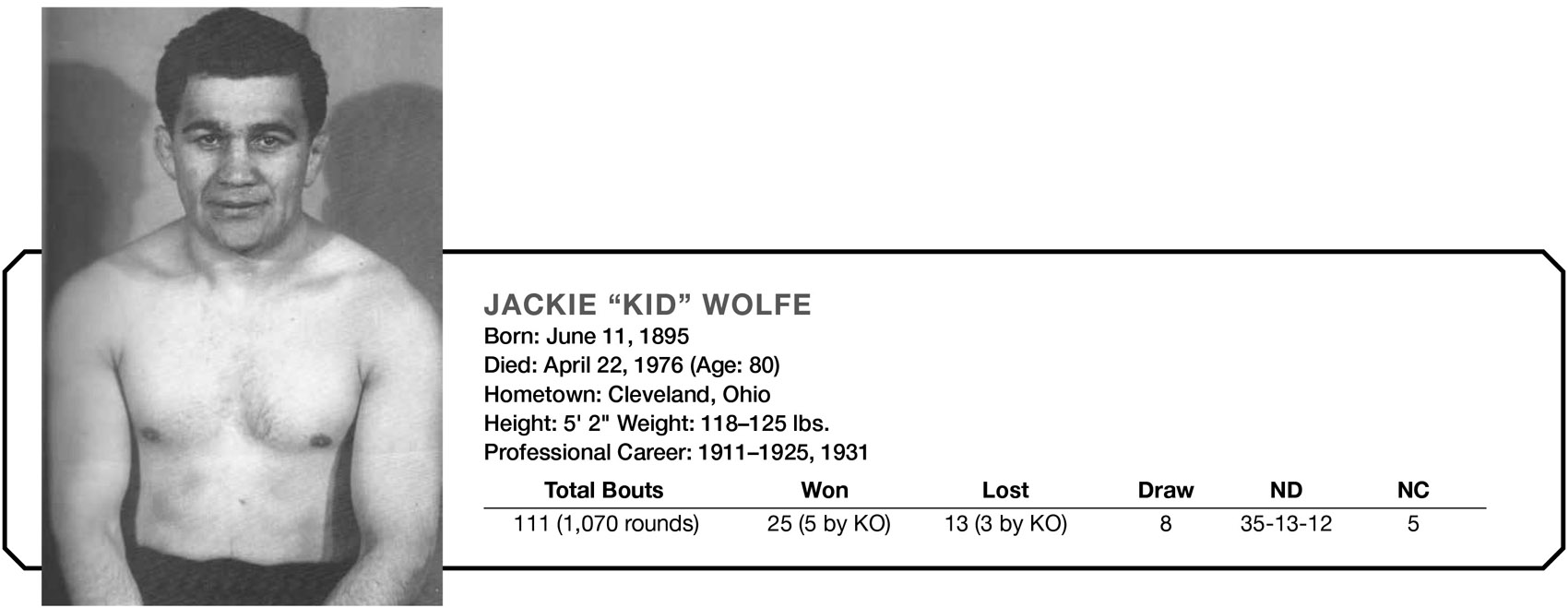

Jackie “Kid” Wolfe

* world champion

Russian-born Jake Abel lived most of his life in Atlanta, Georgia. He fought often in Georgia, Tennessee, and Florida, with an occasional foray into Cuba. Only three of his 95 documented bouts took place north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

During World War I Jake interrupted his career to enlist in the United States Army. Because of his boxing background the army assigned him to be a bayonet instructor. After the war Jake took part in the American Expeditionary Force boxing tournament (a precursor to the Inter-Allied Tournament) and won the lightweight championship. The finals were staged at the Cirque de Paris on April 26, 1919. General Pershing and other high-ranking officers were among a capacity crowd of 14,000. Abel was awarded a medal for sportsmanship by the Prince of Wales.

Jake was a highly skilled and durable ring technician who eagerly took on all comers, including such renowned fighters as Benny Leonard, Jack Britton, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Charley White, Knockout Brown, Eddie Hanlon, Joe Mandot, and Yankee Schwartz.

The $1,000 purse he received in 1919 for a 10-round no-decision bout (non-title) in Atlanta with the great lightweight champion Benny Leonard represented the largest purse of his career. The Associated Press reported that Leonard “gave an exhibition of speed and cleverness that outdid what Abel had to offer.”

Jake retired in 1922 at the age of 29. It was a smart move by a smart fighter. He was just past his prime, and continuing with his career would have made him a stepping-stone for younger fighters on the way up.

After hanging up his gloves Jake went into the hotel business, and for many years managed the Jefferson Hotel in downtown Atlanta. He was active in civic affairs throughout his life, and eventually became president of the Atlanta Hotel Association.

Abe Attell was the 13th of 16 children born to Russian immigrant parents. He grew up in an Irish neighborhood of San Francisco, so knowing how to fight became a matter of survival. Young Abe quickly established a reputation as a tough and tenacious street fighter. The young brawler turned pro at the age of 17, and within two years was competitive with the best featherweight boxers in the world.

In 1903 Abe won universal acclaim as featherweight champion, and over the next nine years successfully defended his title a record 23 times. While champion he also engaged in over 100 non-title bouts. Attell credited early ring scientists James J. Corbett and George Dixon for influencing his style of fighting. He rarely weighed more than 130 pounds, yet took on and defeated opponents outweighing him by 15 to 20 pounds.

Attell loved to gamble, and often bet on his own fights. In one famous incident he wagered his entire $5,000 purse that he would knock out challenger Harry Forbes inside five rounds. He won the bet. Another favorite gambit was to hold back his full arsenal against a hometown favorite to make it appear that he was having a rough time, but do just enough to win. The idea was to generate fan interest and anticipation for a return bout. The betting odds for the rematch would reflect the closeness of the first fight. After placing a hefty wager on himself, Attell would then proceed to take apart his surprised opponent. (He was not the only fighter to occasionally engage in this type of subterfuge.) Famous sports journalist Red Smith accurately described Attell as “a master boxer, dedicated gambler, and tireless schemer.”

Abe lost the featherweight title in 1912 when he was outpointed by Johnny Kilbane in a 20-round bout. His disappointment was somewhat assuaged by the $15,500 he received as his share of the gate—the largest purse of his career. Only two weeks after losing to Kilbane, Attell fought a bloody 20-round draw with lightweight contender “Harlem” Tommy Murphy.

Abe was 29 years old and a veteran of close to 200 fights. He fought for another year and then announced his retirement. Two years later there was the inevitable comeback, but after a few fights it was obvious to his fans that the old magic was gone.

After his ring career ended Abe dabbled in vaudeville and, in the time-honored tradition, opened a saloon. For the next few years not much was heard of Abe until his name suddenly appeared on the front page of every newspaper in America: Abe Attell had been linked to the infamous Black Sox baseball scandal of 1919.

The audacious plan to fix the 1919 World Series was rumored to have been hatched, or, at the very least, abetted by Attell’s close friend, the notorious gambler and racketeer Arnold Rothstein. Abe was alleged to have been the bagman for Rothstein, delivering the $10,000 payoffs to the eight Chicago White Sox players who agreed to throw the Series with Cincinnati. But before he could be subpoenaed, Attell fled to Canada. The self-imposed exile lasted a year. When he returned to face prosecution, a jury found him not guilty because of insufficient evidence.

In 1939 Abe married the former Mae O’Brien. (His first marriage had ended in divorce.) Together they managed a tavern on the East Side of Manhattan. He often attended the fights at Madison Square Garden. Even into his eighties he seemed not to suffer from the debilitating effects of his long career in the ring, unlike so many of his brothers-in-arms.

Monte Attell followed his older brothers Caesar and Abe into the prize ring. By the time Monte turned pro in 1902, big brother Abe had already claimed the world featherweight title. Monte’s rise was not nearly as meteoric as Abe’s. It took at least four years before he established his own credentials as a top bantamweight contender. During his prime (1906 to 1909), Monte lost only two of 34 documented fights.

On June 19, 1909, he knocked out Frankie Neil in the 18th round to win the world bantamweight title. It was a historic moment in that Monte and Abe became the first brothers to hold world titles.

After four successful defenses Monte lost the title to Frankie Conley (Francesco Conte) in the 42nd round of a 45-round marathon bout. Just 57 days later he was back in the ring for a 10-round no-decision with Joe Wagner.

In 1912 brother Abe lost his featherweight title to Johnny Kilbane. Ten months later Monte sought revenge and took on the new champion in a non-title bout. Monte was stopped in the eighth round.

Three years after his bout with Kilbane, Monte incurred an eye injury that became infected. The other eye had already been permanently damaged several years earlier in a 20-round bout with the great British boxer, Owen Moran. By 1920 Monte was legally blind.

The Great Depression and a failed business enterprise wiped out his savings. Blind and broke, the former champion took a job selling peanuts at the weekly fights in the Bay City. He was led around the arena by a little boy who would yell out, “World champion peanuts!” Thankfully, when former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey heard about Monte’s plight, he came to the rescue and financed a cigar stand in San Francisco that provided the old champ with a decent living for many years.

Austrian-born Jacob “Soldier” Bartfield came to America at the age of 16. Jake acquired his nickname after service with the US Army’s 11th Infantry. His division was assigned to the Mexican border in the days of the Pancho Villa raids. “We had a good outfit,” he told boxing journalist Lester Bromberg in 1967, “and those bandits knew it. Soon as we turned up, they ran like hell.”

The converted southpaw’s boxing record reads like a Hall of Fame roster. Opponents included world champions Benny Leonard, Jack Britton, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Harry Greb, Mickey Walker, Mike Gibbons, Billy Papke, Jock Malone, Mike O’Dowd, Jimmy Slattery, Johnny Wilson, and Bryan Downey.

Of all the great boxers that he fought, Soldier said that Harry Greb gave him the toughest fight of his career. He fought Greb six times, and is one of only a handful of boxers to win a newspaper decision over the great “Pittsburgh Windmill.” Two of the bouts (ten and 15 rounds) occurred just nine days apart.

In 14 years this iron man fought over 1,900 rounds, encompassing 221 recorded fights (although it is believed the actual number of fights is closer to 300). He faced scores of top-rated contenders, and traded punches with 13 world champions, 45 times. In 1918 he boxed the great Ted “Kid” Lewis six times, with three of the bouts occurring within 32 days of each other. Nearing the end of his career he took on future champion Mickey Walker three times in six weeks, the last one a 12-rounder.

THE EDUCATIONAL ALLIANCE

In 1889 several leading Jewish philanthropists raised funds for the construction of a neighborhood settlement house on New York’s Lower East Side. Most of the money was donated by educated Jews who came to America from Germany in the 1840s and ’50s in the first wave of Jewish immigration. Several had become wealthy in merchandising (mostly manufacturing and distribution of clothing) or in investment banking firms they founded. They took it upon themselves to establish social agencies for the large number of mostly uneducated and poverty-stricken East European Jews coming to America.

At the beginning this was not always a comfortable arrangement, as they regarded their East European “coreligionists” as socially and culturally inferior. As pointed out by Arthur Hertzberg, in their view these new arrivals “were underscoring the foreignness of Jews in America. Their very first concern was thus to try to limit immigration, but, if not, at least to ‘Americanize’ the new immigrants as quickly as possible. On the surface this meant to teach them English and Western manners, but much more than that was soon attempted.” Their concern was not entirely self-serving. Genuine compassion for their poor East European cousins (most of whom came from Russia and Poland) motivated their actions as well.10

The Educational Alliance Settlement House officially opened in 1891. Its purpose was to help growing numbers of poor East European Jewish immigrants, who were arriving in downtown New York by the thousands every month, to adapt to American society. The staff conducted English classes, gave lectures on how to be a good American citizen, provided free legal aid, and operated a summer camp for children, which was located in upstate New York. It also housed an art school and a theater. In 1895 banker and philanthropist Jacob Schiff purchased another building on the Lower East Side to house the Henry Street Settlement, a social and health service agency. Eight years later the Hebrew Institute of Chicago was established. Like the Educational Alliance, it played a key role in the Americanization of Chicago’s Eastern European immigrant population.

For Jewish boys the icing on the cake of these wonderful institutions was their first-class athletic facilities. Both had fully equipped gymnasiums that included basketball and handball courts, exercise apparatus, a regulation boxing ring, and punching bags. Danny Goodman, one of Chicago’s first Jewish boxing stars, was an instructor at the Hebrew Institute.

In New York City thousands of Jewish boys received their first exposure to boxing in the Educational Alliance’s gymnasium. Famous alumni include Leach Cross, Willie Jackson, Charley Beecher, Sid Terris, Ruby Goldstein, Sammy Dorfman, Lew Kirsch, and world champions Dave Rosenberg, Abe Goldstein, Ben Jeby, and Bob Olin.

By 1910 over 100 settlement houses and community centers, catering to a mostly Jewish clientele, had opened in virtually every major urban center of the United States.11 The boxing programs were not intended to prepare future professional boxers. Their goal was to promote fitness and self-confidence. Nevertheless, knowing how to box was a useful skill that could come in handy, especially for Jewish boys living in poor immigrant neighborhoods.

Today, the Educational Alliance is still housed in its seven-story flagship building at 197 East Broadway. In addition, there are several other sites affiliated with the Alliance that offer a variety of services, including residential and outpatient drug treatment centers, counseling, after-school programs in New York City Public Schools, senior citizen residential facilities, and other programs serving the community.

Bartfield was most proud of his 1915 no-decision bout against the famed “St. Paul Phantom,” Mike Gibbons, at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. He entered the ring a 10–1 underdog. But Gibbons, one of the finest scientific boxers of his era, could not cope with the Soldier’s special brand of pressure and incessant body punching. (Bartfield broke three of Gibbons’s ribs.) All four newspapers covering the bout scored it for Bartfield. He received $25,000 for the bout—the largest purse of his career.

Soldier retired in 1925 (although there was a brief two-bout comeback in 1932). He worked for 18 years in the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a ship fitter. In retirement he split his time between a 50-acre farm he owned near Hunter, New York, and a home in Canarsie, Brooklyn.

Charlie Beecher was 16 years old when he took his first boxing lesson at the famous Educational Alliance Settlement House in New York’s Lower East Side. Three years later he won the New York State amateur bantamweight championship. For most of his brief but successful professional career (1918–1923), Charlie was rated among the top featherweight contenders. He proved his mettle against the likes of Red Chapman, Jackie “Kid” Wolfe, Andy Chaney, Freddie Jacks, Benny Gould, Johnny Brown, Frankie Garcia, Dick Loadman, and Frankie Burns.

In the late 1920s Charlie opened “Beecher’s Gym” in the back of a pool hall he owned in Brownsville, Brooklyn. The gym became a popular training site and an active part of the New York boxing scene for the next quarter of a century.

Willie Beecher is the older brother of featherweight contender Charlie Beecher. During his 13-year career Willie met virtually every outstanding lightweight contender and recorded memorable no-decision bouts against world champions Abe Attell, Ted “Kid” Lewis, and Jack Britton. The rugged 140-pounder was stopped only three times in 163 fights, with all three losses occurring either early or late in his career.

In 1914 Beecher lost a 20-round decision to lightweight contender Mexican Joe Rivers. Just three weeks later he fought a 20-round draw with future featherweight champion Johnny Dundee. His next bout was a non-title 10-rounder against lightweight champion Freddie Welsh at Madison Square Garden. According to newspaper accounts the brilliant Welshman easily outpointed Beecher.

From 1917 to 1919 Willie served in the United States Marine Corps. He launched a brief comeback in 1920, but retired the following year.

The first Jewish boxer from New York City to achieve a measure of notoriety at the turn of the last century was Dolly Lyons. Not much is known about Lyons. Only about a dozen contests have been documented, although it is assumed he fought many clandestine bouts at a time when the sport was illegal in New York. After losing a 20-round decision to Joe Bernstein in 1899, Lyons faded from the scene.

Within months of defeating Lyons, Joe Bernstein’s name was known to every boxing fan in America when he lost a close 25-round decision to the top-ranked bantamweight contender, Terry McGovern. Just one month later, in another 25-round bout, he challenged the great featherweight champion, George Dixon. Dixon, a Canadian, was the first black world champion in any weight class. Joe put up stubborn resistance but lost the decision. Ten weeks after his defeat by Dixon, Bernstein knocked out former champion Solly Smith in the 13th round.

“The Pride of the Bowery” failed in two subsequent attempts to capture the featherweight title, losing to both McGovern and Young Corbett II. On the plus side he scored important victories over Tommy White, Eddie Santry, and Young Griffo. Three 25-round draws with the formidable Dave Sullivan solidified Bernstein’s status as one of the world’s top featherweight contenders.

Joe’s pro career lasted 12 fruitful years. He retired in 1908 after a fourth round TKO loss to Leach Cross.

Phil Bloom was born in the Whitechapel district of London’s East End, home to most of England’s great Jewish boxers. In 1911 Bloom’s father, a tailor, took his wife and eight children to America. The family settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Phil had boxed as an amateur in England and decided to turn pro that same year. The high points of his 201-bout career were eight encounters with the great lightweight champion, Benny Leonard. Bloom was KO’d twice by Leonard but finished on his feet the other times.

In addition to Leonard, Bloom fought five other world champions—Jack Britton, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Johnny Dundee, Rocky Kansas, and Dave Rosenberg.

Even in an era of iron men, Bloom stood out as a remarkably durable fighter. On December 2, 1916, he boxed 20 rounds with perennial contender Irish Patsy Cline in Brooklyn. Four days later he was in Detroit where he went 10 rounds with tough veteran Stanley Yoakum. After one day’s rest Bloom hustled back to New Haven, Connecticut, where he dropped a 15-round decision to top lightweight contender Joe Welling. Seventeen days after losing to Welling he was back in Brooklyn for a 10-rounder against Chuck Simler.

In 1920 Bloom returned to London and won a 20-round decision over former welterweight champion Matt Wells. Eight days later he fought another 20-rounder, outpointing Danny Arthurs. Bloom finally hung up his well-worn boxing gloves in 1923. He moved to Los Angeles in the late 1920s, where he became an extra and bit player in many Hollywood movies.

Phil Brock and his younger brother Matt were Cleveland, Ohio’s, first Jewish boxing stars. Both were lightweights. Matt was the harder puncher, but Phil was considered the better boxer.

Phil turned pro in 1904, and within six years was competitive with the world’s finest lightweight boxers. Among his victims were Philadelphia Pal Moore, Fighting Dick Hyland, Jack Redmond, and Matty Baldwin. He also had draw decisions with Harlem Tommy Murphy, former featherweight champion Young Corbett II, and future lightweight champion Willie Ritchie. Losses to Owen Moran, Packey McFarland, and Freddie Welsh did not tarnish Phil’s reputation, as they were rated among the greatest fighters of their era.

Brooklyn’s Sam Holtzman adopted the very Irish name “Frankie Callahan” to keep his parents from finding out he was a boxer.* Before hanging up his gloves in 1922, he fought 175 documented professional bouts. His opponents included five world champions and most of the top lightweights of his era, including Pete Hartley, Charley White, George KO Chaney, Willie Jackson, Phil Bloom, Pal Moore, and future champion Rocky Kansas.

The highlight of his career occurred in 1917 when two of three newspapers awarded Callahan the unofficial victory in a 10-round no-decision bout with a near-prime Benny Leonard. Three months later Leonard won the lightweight title. Previous to his bout with Leonard, Callahan had won a newspaper verdict over future featherweight champion Johnny Dundee.

Nineteen days after his bout with Leonard, Callahan fought another no-decision bout against Dundee. Two newspapers favored Callahan and two others called it a draw. Five weeks later the 22-year-old faux Irishman knocked out lightweight contender Jimmy Hanlon in the 19th round.

The one fighter that Callahan could not solve was Lew Tendler. He lost three newspaper decisions to Tendler and, nearing the end of his career, was stopped twice by the great Philadelphia southpaw.

An obituary in the New York Times reported that Callahan passed away after contracting pneumonia. He was 32 years old.

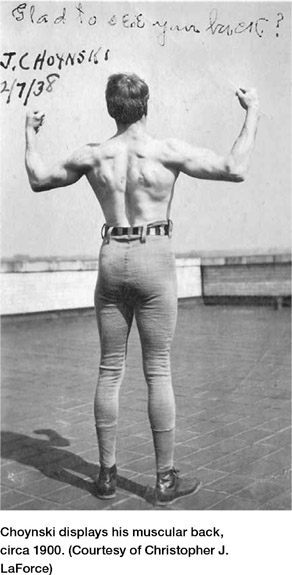

San Francisco’s Joe Choynski (pronounced Co-IN-sky) was the first Jewish athlete to achieve international prominence. Joe had an interesting pedigree. He was one of the few professional boxers not born into poverty. His father, Isadore, the son of a rabbi, had attended Yale College, where he earned a teaching degree. After moving to San Francisco Isadore became a dealer in rare books, and was the West Coast correspondent for The American Israelite newspaper for 20 years. The elder Choynski also published his own periodical called Public Opinion, which he used as a vehicle for exposing municipal corruption and anti-Semitism.12

While his father traveled in intellectual circles (he counted Mark Twain among his friends), Joe danced to a different drummer. Although he was highly intelligent and articulate, formal education did not interest him. After dropping out of high school he found work as a blacksmith and then as a candy puller in San Francisco’s notorious Barbary Coast. Both of these physically rigorous jobs proved to be excellent preparation for boxing.

Choynski was five-foot-11 and weighed around 170 pounds. Before 1903 there was no light-heavyweight division for fighters who weighed between 160 and 175 pounds. As a result, over the course of his 83-bout career, Joe often took on opponents who outweighed him by 20 to 60 pounds. Fortunately for Joe, he was not only a superb boxer, but also one of the sport’s deadliest punchers.

On May 30, 1889, 19 months after his pro debut, Choynski was matched with San Francisco rival and future heavyweight champion James J. Corbett. Their fight was halted by the police after the fourth round (professional boxing was outlawed in San Francisco), and a rematch was scheduled one week later. In order to avoid police interference, the fight took place on a barge anchored in San Francisco Bay, near the town of Benicia.

Several hundred people crowded onto the barge to witness one of boxing’s legendary fights. In a brutal seesaw battle that saw both men come back from the brink of defeat, Corbett knocked out Choynski in the 27th round. The bout, fought under Queensberry rules (three-minute rounds separated by one minute of rest), had lasted just under two hours.

During his illustrious 16-year career Joe Choynski took on three past or future heavyweight champions. Outweighed by 40 pounds, he fought a 20-round draw with James J. Jeffries, was stopped in five by Bob Fitzsimmons, and knocked out Jack Johnson in three rounds. Other legendary opponents included Tom Sharkey, Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, Kid McCoy, and Barbados Joe Walcott.

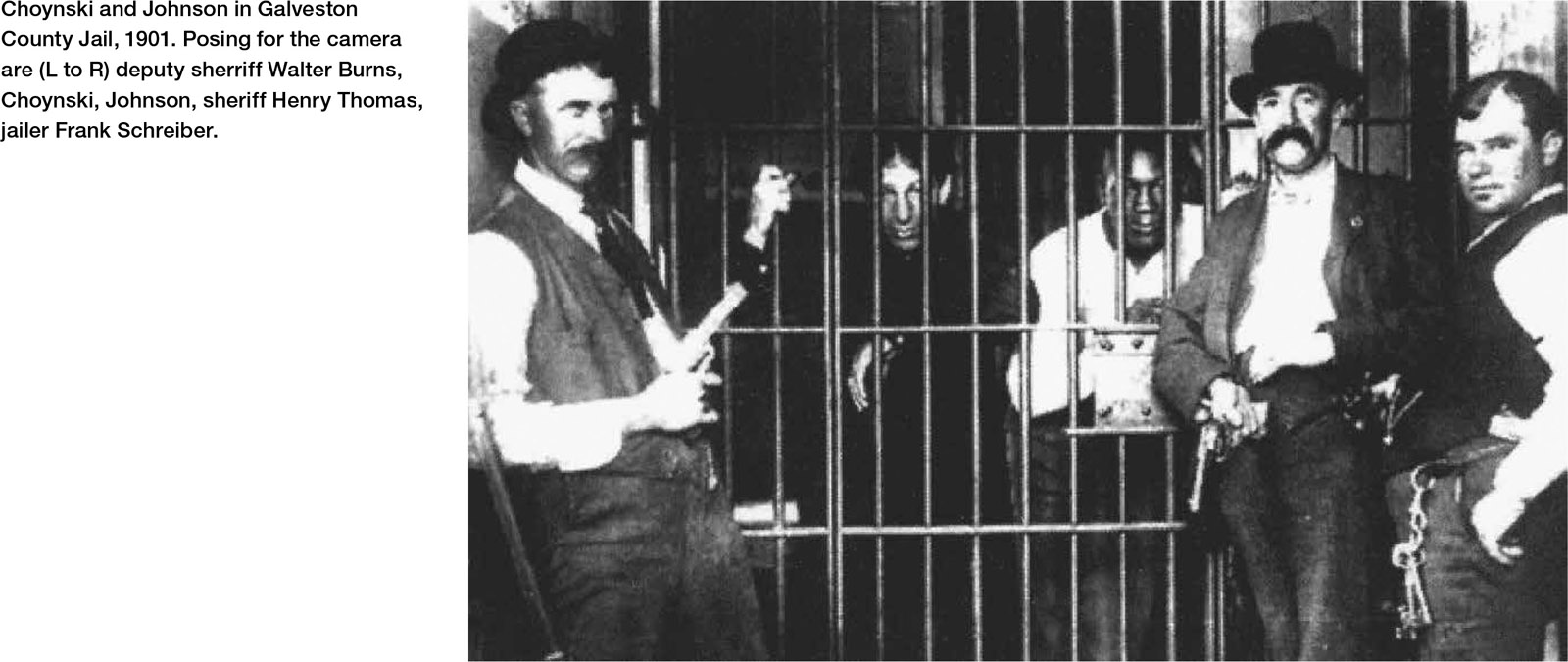

Choynski always considered his 1901 knockout of future heavyweight champion Jack Johnson the most significant victory of his career. (Seven years after their fight, Johnson would become the first black heavyweight champion.) At 32 years of age Joe was 10 years older and 25 pounds lighter than Johnson. Most people expected the veteran to lose. The fight took place in Johnson’s hometown of Galveston, Texas.

In the third round Choynski landed a tremendous left hook that knocked Johnson cold. As soon as the referee completed the 10-count, five Texas Rangers stormed into the ring and arrested both fighters for violating a local ordinance against professional boxing contests.

Johnson and Choynski shared the same prison cell for two weeks but were treated more like celebrities than outlaws. They were even allowed to leave the prison in the evenings— Choynski to his hotel, and Johnson to his home—but had to return the following morning. Both fighters staged sparring exhibitions for the warden and his staff while state politicians used the jail sentence to score points as protectors of public decency.

During their confinement Johnson asked his cellmate to teach him the tricks of an old pro. In his autobiography Johnson credited Choynski with helping to refine his boxing style. “Every day we would box in the jail yard, surrounded by police officers and guests,” wrote Johnson. “Joe had great affection for me, and to prove it, he gave me lessons, showing me the best punches anyone has ever seen in a jail yard. I learned more in those two weeks than I had learned in my entire existence up to that point.”13 Jack Johnson is still rated by many experts to be among the top five heavyweights of all time.

Choynski continued to box for three more years, finally retiring in 1904, at the age of 36, after having fought 83 professional fights. He had a brief fling as an actor, costarring in a touring stage production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin with the great Australian heavyweight, Peter Jackson (the first prominent black fighter of the gloved era). The show’s climax was a sparring session between the stars. After the sparring session an announcement was made offering $500 to anyone in the audience who could last three minutes with either fighter. It is not known if anyone took up the challenge.

Joe eventually moved to Chicago and entered the insurance business. In 1942, shortly before he passed away at the age of 74, he was hired as technical consultant for the movie Gentleman Jim, starring Errol Flynn as Corbett. The legendary 1889 barge fight was re-created for the film. A bit of poetic license was taken, as the Hollywood version shows Corbett getting knocked off the barge and splashing into San Francisco Bay and then climbing back to resume the battle. (The Raoul Walsh–directed film is a classic, and the author’s personal favorite.)

The Boston Irish would have been proud to call Johnny Clinton one of their own. He always put forth a 100 percent effort, gave no quarter, and asked for none in return. But he was Irish in name only. Johnny Clinton was a Jew from Boston’s West End whose real name was Morris Elstein.

This faux Irishman had already fought some of the best lightweight boxers in the world before his 21st birthday, including multiple bouts with Mel Coogan, Frankie Conifrey, Joe Welling, Lou Bogash, Frankie Schoell, and Johnny Shugrue. But his proudest moments in the ring were his two no-decision bouts with the incomparable lightweight champion Benny Leonard. They met twice—the first time in 1919, and in a rematch two and a half years later. Both fights went the full 10 rounds. There was no doubt about Leonard’s superiority, but Clinton was no pushover, and the champion had to perform at his best each time.

Even at the tail end of his busy career, Clinton was still meeting top contenders. In 1923 he lost a 10-rounder to Sailor Friedman, but rebounded less than three months later with a 12-round nod over England’s Harry Mason. As his career wound down Clinton lost decisions to Pete August, Young Harry Wills, and future middleweight champion Joe Dundee. Shortly after his thirtieth birthday Clinton announced his retirement. Potential opponents, both Irish and Jewish, breathed a sigh of relief.

Until the rise of Benny Leonard a decade later, Leach Cross was the most popular fighter to ever come out of New York’s Lower East Side neighborhood. The son of Austrian immigrants, Leach’s actual birth name was Louis Charles Wallach. The name change was an attempt to hide his fistic activities from his father. “Leach” was a derivation of his childhood nickname, “Lachey.” Three of his younger brothers, Phil, Dave, and Marty, also became pro boxers, with varying degrees of success.

Before he embarked on his busy pro career, Leach Cross began studying dentistry at New York University. He graduated in 1907 and went to work at the office of a dentist friend. Leach practiced dentistry by day while boxing at night— hence, his nickname, “The Fighting Dentist.”

By 1908 Leach was earning $15 a week as a dentist. That same year his first main event paid him $35. Leach temporarily suspended his dental practice to devote full-time to his more lucrative pugilistic endeavors.

Two years into his pro career, the dentist/fighter became a ghetto sensation when he stopped the much-admired Joe Bernstein in four rounds. By then he had earned enough money to open his own dental practice on the East Side. The establishment soon had enough patients to keep two assistants busy, but Leach’s main source of income still came from boxing. His earnings in the ring were estimated at from $1,500 to $3,000 a month.14

From 1909 to 1916, “Leachie,” as he was called by friends, had 89 bouts. Among his opponents were boxing legends Freddie Welsh, Jack Britton, Johnny Dundee, Jem Driscoll, Packey McFarland, Charley White, Matt Wells, and Ad Wolgast.

“The Fighting Dentist” knew all the tricks of the trade. He fought out of a low crouch, which made him difficult to hit. His right uppercut and right cross were his most effective weapons. One of his favorite maneuvers was to feign grogginess in order to draw an opponent into making a careless mistake. When his opponent lunged forward, Leach timed the punch, slipped it, and countered. Opponents eventually caught on to the trick, but they never knew for sure if Leach was really hurt or just faking. Neither did the fans, who came out in droves to watch the colorful and exciting fighter in action.

The most memorable fight of his career was a 1909 encounter with Fighting Dick Hyland in Colma, California. The bout was a marathon contest scheduled for 45 rounds. After more than two hours of fighting Leach was knocked out in the 41st round. Bad weather had kept attendance down. He was paid only $350 for the toughest and most punishing fight of his career.

During the day Leach attended to his dental practice, while at night he could often be found topping a card at one of New York City’s many fight clubs. In his last bout of 1911, Leach was matched against the dangerous lightweight contender Knockout Brown. The bout took place in Manhattan’s Empire Athletic Club. Both fighters were seasoned campaigners with more than 80 bouts apiece. Knockout Brown, whose real first name was Valentine, packed the heavier wallop. Over a dozen of his opponents had not made it past the first round.

On the day of the fight a standing-room-only crowd was on hand to see the highly anticipated match. The 10-round bout was a closely contested, action-packed battle. Brown kept boring into Leach, pressuring him throughout the fight, but it was Leach who was more accurate with his punches and who did most of the scoring.

During the fight Brown had a couple of his teeth loosened. The following day his manager took him to a dentist’s office to have them checked. Brown was dumbfounded when he saw who the dentist was. Standing in front of him, dressed in a white medical smock, was none other than Dr. Louis C. Wallach, alias Leach Cross.15

Leach finally hung up his gloves in 1916. His good friend, the singer Al Jolson, suggested he move to California. With his nest egg of $46,000 Leach built a house in Hollywood, and later opened up a gymnasium that became very popular with movie stars and businessmen. He counted Rudolph Valentino, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and Charlie Chaplin among his close friends.

Eventually bad investments and a costly divorce wiped out his savings, driving him into bankruptcy. Leach decided to leave California and return to New York City, where he reopened his dental practice in Union Square.

In his early sixties, Leach began to suffer the effects of his lengthy boxing career. Failing eyesight and increasing dementia forced him to close his office. He passed away in 1957 at the age of 71.

BOXING TRADING CARDS

The popularity of the charismatic heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan led to an active market for boxing collectibles, most notably trading cards. In the 1880s American tobacco companies began to insert pictures of Sullivan and other famous boxers into cigarette packs as a way to promote their products. (A pack of 10 cigarettes usually sold for five cents.) Other inserts might include pictures of baseball players, actresses, Indian chiefs, frontier heroes, kings, police chiefs, billiard players, birds, and ships.

In 1910 the American cigarette industry introduced several Turkish brands named Hasson, Mecca, Fatima, and Turkish Whiffs. Each included a series of colorful boxing inserts. A full set (usually numbering around 50) is considered a valuable collector’s item today.

England, with its rich boxing history, was also a major producer of boxing trading cards. The two most popular sets of cards were those produced in the 1930s and ’40s by the W. A. & A. C. Churchman Cigarette Company of London and Knock-Out Razor Blades of Sheffield.

Beginning in 1921 the Exhibit Supply Company of Chicago began selling postcard-size photos of contemporary boxing stars from vending machines for a penny each. The boxer’s record appeared on the opposite side of the card. A new series of cards was printed in 1928, but did not include the fighter’s record. The Exhibit Supply cards featured champions and contenders from the past and present.

The first post–World War II set of boxing cards was issued by two major chewing gum companies, Topps and Leaf, although their brilliantly colored cards did not meet the standards of workmanship displayed in the cigarette-pack inserts of a generation earlier.

A final set of Exhibit Supply cards was issued in the early 1960s. They were sold in amusement parks and penny arcades for five cents each. Today, depending on the fighter pictured, collectors pay between $20 and $150 per card

Joe Fox fought in the classic stand-up style popular with British boxers. For most of his 16-year professional career, he ranked among the world’s best bantamweights and featherweights. Fox was awarded the prestigious Lonsdale Belt after winning British titles in both divisions. (The Lonsdale Belt, named after the first president of London’s National Sporting Club, is awarded to all British champions). He made two trips to America, in 1913 and 1919, where he crossed gloves with such outstanding ring men as Joe Tiplitz, Babe Herman, Al Shubert, Benny Valgar, and future champions Joe Lynch, Sammy Mandell, and Eugène Criqui. In 1919 he lost a six-round newspaper decision (non-title) to world featherweight champion Johnny Kilbane.

One year after he retired, Fox married and settled down. He opened a candy shop where he proudly displayed his Lonsdale Belt in a framed cabinet above the counter.

Abe Friedman was never knocked out in 122 professional fights, despite facing virtually every top bantamweight and featherweight in the 1910s and early 1920s. That was no small accomplishment considering the extraordinary depth of talent in those divisions. His opponents included the likes of Pete Herman, Kid Williams, Pancho Villa, Joe Lynch, Young Montreal, Danny Kramer, Joe Burman, Johnny Ertle, and Roy Moore. He also fought two no-decision bouts with Charley Goldman, who later gained fame as the trainer of heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano.

Friedman served in the US Army during World War I. He resumed his career in 1919, fighting mostly in the Boston area. In the last few years of his career he was plagued by failing vision. On May 4, 1925, Friedman lost an eight-round decision to Rosey Stoy and announced his retirement. Tragically, three months later, while crossing a street near his home, Friedman was hit by a truck and killed.

Before Charley Goldman gained recognition as one of boxing’s all-time great trainers, he was a serious contender for the bantamweight championship of the world.

Growing up in Brooklyn’s tough Red Hook section at the turn of the last century, young Charley idolized his neighbor, the great featherweight champion “Terrible” Terry McGovern. He was thrilled when the champ gave him the honor of carrying his gym bag to workouts. In imitation of his hero Goldman began parting his hair in the middle, and for his entire life always wore a derby, just like McGovern.

Charley claimed to have had over 400 bouts, but only 129 have been documented. His earliest recorded pro fight was a 42-round draw with Young Gardner in 1904. Since boxing was illegal in New York, the bout took place in the back of a saloon in Manhattan’s Bowery neighborhood.

The highlight of Charley’s career was a 1912 non-title fight against the great bantamweight champion Johnny Coulon. Two newspapers scored the 10-round no-decision bout for Coulon, while two others scored it a draw.

In 1913 Charley began training middleweight contender Al McCoy (Albert Rudolph). After McCoy won the title Goldman decided to devote himself full-time to training fighters. In 1924 he formed a partnership with manager Al Weill that continued for the next 32 years. Goldman trained scores of boxers for Weill and was also outsourced to train fighters for other managers. Charley trained four world champions for Weill: Lou Ambers (lightweight), Joey Archibald (featherweight), Marty Servo (welterweight), and his most famous pupil, Rocky Marciano, the only heavyweight champion to retire undefeated.

Abe “Kid” Goodman was the first Jewish boxing star from Boston. He turned pro in 1899, and over the next four years lost only seven of 95 fights. Highlights of Goodman’s career include decisions over top lightweight contender Aurelio Herrera, future welterweight champion Harry Lewis, and draw decisions with featherweight champion Abe Attell (nontitle) and former champion Young Corbett II. Other notable opponents were Benny Yanger, Matty Baldwin, Harlem Tommy Murphy, Packey McFarland, Dick Hyland, and Cyclone Johnny Thompson.

By 1910 it was obvious Goodman had passed his peak, but he continued to fight for another six years, losing to fighters he could have easily beaten in his prime. After he retired Goodman became a deputy sheriff in Boston.

Harry Harris was the first Jewish world champion of the twentieth century. At five-foot-eight and 115 pounds, he was one of the tallest bantamweight champions in the history of the division. He was also one of the most accomplished boxers of his era. As a teenager he was mentored by the famous Kid McCoy, who taught him the tricks of the trade, including his signature “corkscrew punch.”

In 1901 Harry won the bantamweight championship of the world by outpointing England’s Pedlar Palmer in 15 rounds. He fought only three more times before announcing his retirement.

The decision to retire while still in his prime was prompted by a fortuitous meeting with theatrical impresario E. A. Erlanger. Impressed by Harry’s intelligence and engaging personality, Erlanger offered him a job managing the New Amsterdam Theatre in New York City. While working at his new profession Harry met his future wife, the actress Desiree Lazard, while she was costarring at the New Amsterdam with George M. Cohan in his hit musical, 45 Minutes from Broadway.

Harry liked the theater world and enjoyed his work, but he missed being center stage as the star of his own show. In 1905, three years after his last fight, Harry launched a brief comeback and engaged in six contests before returning to his job as a theater manager.

A man of many interests and talents, Harry became fascinated by the world of finance. In 1919, at the age of 39, he purchased a seat on the New York Curb (forerunner of the American Stock Exchange). He remained a Wall Street broker for the next 30 years, specializing in international securities.

BOXING SUFFRAGETTES

In America, prior to the 1920s, boxing had been off limits to women spectators. It was not considered “proper behavior” for a woman to attend a prizefight, and although no official ban existed, they were usually barred from entering an arena. That attitude began to change with the arrival of Tex Rickard, the great visionary promoter of the early 1900s. Not that Tex was a champion of egalitarianism; his motives had more to do with expanding his bottom line than expanding women’s rights. Tex believed the sport’s low-class image would improve if he could attract significant numbers of women to attend his boxing shows.

Rickard’s first attempt to integrate the all-male enclave occurred in 1906, the year he promoted his first “fight of the century”—an interracial title bout featuring the great African-American lightweight champion Joe Gans defending his title against Oscar “Battling” Nelson (aka, “The Durable Dane”) in the gold-mining boomtown of Goldfield, Nevada. Rickard announced to the press that he would allow women to attend the event. In an article published 11 days before the bout, Tex told a reporter he expected 250 to 300 women to witness the contest. He further explained that special preparations were being made to accommodate the female spectators.

“The arena will be filled by specially sworn-in officers who will see that nothing offensive is said or done,” said Tex. “No one under the influence of liquor will be allowed within the gates, and the officers will be instructed to eject any man who in any way transgresses the rules laid down by the club for the protection and comfort of the women.”16

Tex’s pronouncement was condemned by the local clergy. The pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Goldfield, Reverend James Byers, warned his female congregants: “I will expel any woman who attends any prize fight from my flock.”17 Rickard could care less what the keepers of public decency had to say. He reveled in the pre-fight publicity the controversy aroused.

The Gans vs. Nelson title bout lived up to expectations. The grueling contest between “The Old Master” and “The Durable Dane” lasted an incredible 42 rounds under the broiling Nevada sun, until an exhausted “Battling” Nelson was disqualified for landing a deliberate low blow. How many women attended the bout was difficult to determine, as they disappeared into the crowd of more than 18,000 fans. But no matter the actual number, Rickard had irrevocably shattered a boxing taboo.

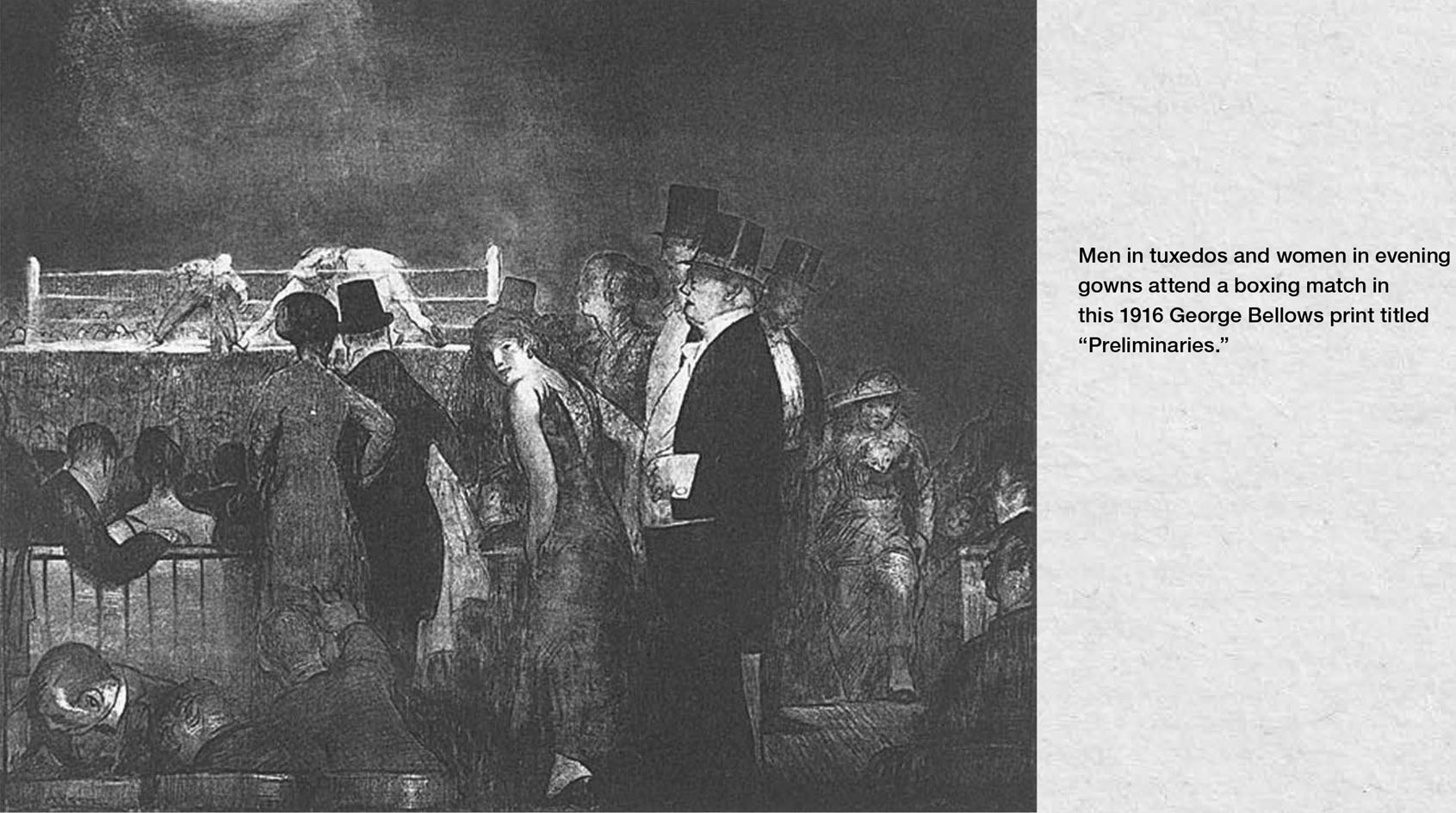

A decade and a half later, in the midst of the freewheeling Roaring Twenties, the presence of women at prizefights, especially for important contests, was by then a common occurrence. Tex Rickard, now ensconced in New York City, kept to his strategy of providing an atmosphere conducive to attracting the fairer sex. Under Rickard’s management, major boxing matches had become glamorous and exciting happenings. When the new Madison Square Garden opened in 1925, more than 17,000 thousand fans filled the arena for its first title fight, including a large segment of showbiz royalty and New York high society. They were all there to see and be seen. They filled the ringside section dressed in their evening clothes, the women among them “conspicuous in attendance and draped in elegant attire and wearing fine jewelry.”18

While it’s doubtful the presence of women at prizefights in the early years of the twentieth century contributed significantly to the women’s suffrage movement and the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, I wouldn’t dismiss the idea entirely. Sometimes it’s the accumulation of many small and seemingly insignificant advances that contribute to the larger victory. I like to think that Tex and those gutsy women who first entered the all-male world of the boxing arena did their part.

Kid Herman was born in Montreal, Canada, but moved to Chicago at an early age (not to be confused with another “Kid Herman,” who fought out of New York several years later). In his prime, Chicago’s Kid Herman fought draw decisions against the likes of Abe Attell, Aurelio Herrera, and Harry Lewis.

In 1907 Herman won a 10-round decision over highly rated lightweight contender Benny Yanger. That victory earned him a title bout with the brilliant lightweight champion Joe Gans, nicknamed “The Old Master” because of his artistic boxing skills. (Gans was the first black American to win a world boxing title, and is still considered one of the greatest boxers of all time.)

Herman made a good showing for seven rounds but was in over his head. Gans bided his time and knocked him out with a picture-perfect right cross in the eighth round. (A film of the fight exists and is available for viewing on YouTube.) Eleven months later he was badly beaten by Packey McFarland and retired. Kid Herman was killed in an auto accident in 1934.

The boxing world used to stand on the shoulders of such men as England’s Freddie Jacks. A “have gloves, will travel” type, Jacks was a tough and seasoned journeyman who would fight anyone, anywhere. His services were always in demand because win or lose, he always put up stiff resistance and was rarely stopped. In his heyday Jacks was known as “The Aldgate Ironman.”

Jacks fought under several different names early in his career. His official record lists 175 fights, but the actual number is believed to exceed 200. Top opponents included world champions Johnny Kilbane, Rocky Kansas, Louis “Kid” Kaplan, Joe Dundee, and Jimmy Goodrich. Toward the end of 1922, Freddie traveled to Australia and had five 20-rounders in four months. He was also very popular in America, where he stayed for five years while participating in over 80 contests.

On June 25, 1923, in his only shot at a world title, Freddie was stopped in the fifth round by the great junior lightweight champion, Jack Bernstein.

There was no mistaking Willie Jackson’s profession: his flattened nose and heavily scarred eyebrows provided mute testimony to the countless punches he absorbed in 144 professional fights. Famed boxing journalist Dan Parker wrote that Jackson “was possibly the best club fighter of this or any other century.”*

Willie Jackson began his career as a “stick and move” speedster, scoring only six knockouts in his first 39 bouts. But on January 15, 1917, he shocked the boxing world (and himself) with a first-round knockout of the number-one featherweight contender, Johnny Dundee.

One of Dundee’s signature moves was to rebound off the ropes to gain extra momentum in his punches. But this time the great fighter miscalculated. As he caromed off the ropes his chin ran smack into Jackson’s right cross and he was counted out. (Not until 14 years later was another fighter able to stop the great Dundee, well past his peak and in his 328th professional bout.) Jackson and Dundee fought nine more times (a total of 105 rounds). All of their bouts were competitive, but Jackson was unable to duplicate his KO victory.

Jackson’s sensational upset of Dundee skyrocketed him to national prominence overnight. Convinced that he possessed knockout power in his right fist, Jackson abruptly altered his style, transforming himself into an aggressive pressure fighter who was willing to take a punch to land one. But the speed of his impressive windmill attack rarely allowed him time to set down on his punches, which accounted for his low KO percentage. Nevertheless, it was a style that was pleasing to the fans and earned him lucrative purses.

Other formidable opponents include Lew Tendler, Frankie Callahan, Leo Johnson, Pete Hartley, Jimmy Hanlon, Frankie Britt, Matt Brock, and future champion Rocky Kansas.

Jackson was past his prime when he suffered a brutal beating by lightweight contender Charley White while losing a 15-round decision at Madison Square Garden in 1922. Less than a year later Joe Shugrue stopped him in the 10th round. It was only the third stoppage he’d suffered in 147 pro bouts.

Jackson retired in 1924 and became a paper and twine salesman in New York City. But his long and punishing career as a boxer eventually took its toll. He was forced to retire in his late fifties, no longer able to work due to progressive dementia caused by the countless punches he’d absorbed in the ring.

Young Joseph was one of England’s first Jewish boxing stars of the twentieth century and a role model to such boxers as Ted “Kid” Lewis and Jackie “Kid” Berg. He first attracted attention in 1903 after a series of victories at the legendary Wonderland Arena, a 2,000-seat emporium located on Whitechapel Road in London’s East End. The popular 18-year-old boxer did not pack much of a punch, instead relying on speed and cleverness to defeat his opponents. It was a style appreciated by knowledgeable English boxing fans. Joseph weighed about 120 pounds at the beginning of his career. The young boxer would eventually grow into a 145-pound welterweight.

In 1907 Joseph advanced his career by winning two 20-round decisions (two-minute rounds) over former British lightweight champion Jack Goldswain. Over the next three years he acquired both the British and European welterweight titles. Joseph traded punches with the likes of Johnny Summers, Young Otto, Rudy Unholz, Owen Moran, and future lightweight champion Freddie Welsh.

After his victory over Otto in 1909 Joseph claimed the world welterweight title. The claim was generally ignored by most boxing fans and authorities. The following year Joseph challenged the recognized welterweight champion of the world, Harry Lewis, and was stopped in the seventh round. In 1911 he lost his European welterweight title to France’s future light-heavyweight king Georges Carpentier via a 10th-round knockout. After hanging up his gloves Joseph stayed active in boxing as a manager and promoter.

Russian-born Jacob Flinkman came to Philadelphia with his parents as a young boy in 1895. He began boxing in local amateur clubs at age 16. Two years later he turned professional as “Battling Flink,” but soon settled on the ring name of Benny Kaufman.

Kaufman was a five-foot-four, 135-pound block of granite. He plowed through 102 opponents in his first five years as a pro. Among his best performances was a 12-round draw with the great Charley White, along with newspaper verdicts over lightweight contenders Patsy Brannigan and Frankie Conley. In officially scored contests he lost decisions to highly rated lightweights Dutch Brandt and Al Shubert.

Other great opponents included Johnny Kilbane, Willie Jackson, Lew Tendler, George KO Chaney, Frankie Burns, former bantamweight champion Kid Williams, and a host of other long-forgotten featherweight and lightweight contenders. No-decision matches accounted for 136 of his 183 career bouts.

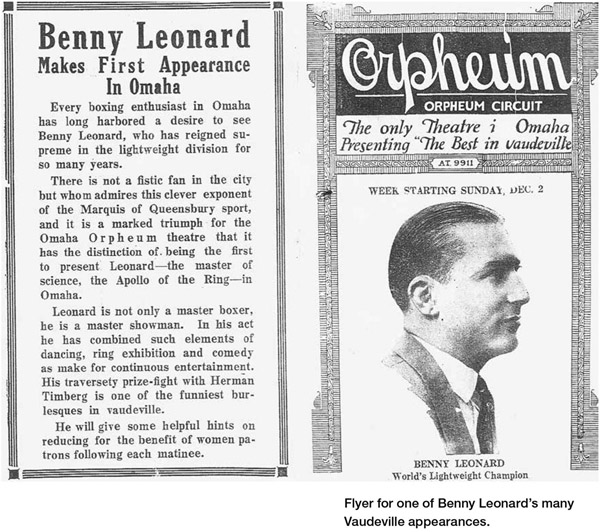

No decade produced more Jewish boxers than the 1920s—and the person most responsible for inspiring the flood of Jewish talent was Benny Leonard, who ruled the lightweight division from 1917 until his retirement as undefeated champion eight years later, in 1925. The greatest compliment any Jewish boxer could receive was to be called “the next Benny Leonard.”

It is not surprising that a fighter who considered his brain the most important weapon in his formidable arsenal would view boxing as a physical game of chess. And like a master chessman, Benny Leonard set subtle traps and ambushes without ever “telegraphing” his intentions. His goal as a boxer was to quickly determine an opponent’s habits, his strengths and his weaknesses, disrupt his game plan, and then do what was necessary to win. He developed his superb jab and defensive maneuvers during his early teen years when he was a slightly built 115-pound bantamweight who could not afford to mix it up with stronger opponents. As his frame filled out and he grew stronger and heavier, Leonard added a powerful right-hand punch to his repertoire.

In his prime Leonard was far superior to most of his opponents, but he never sought to humiliate them. “I don’t want to hurt the other guy,” said Leonard. “I want to stop him. But that does not mean I am eager to cut him up and murder his self-respect. The credo of the professional ring is to win with speed and your best means of execution. As for that ‘killer instinct,’ I never had it as a kid when bringing home the pay was very important, and I never had it as champion.”19

Oftentimes Leonard would be content just to outbox an opponent and sharpen his reflexes while getting a good workout. But every now and then he would decide to deviate from the plan. “Many a night I would be in there just looking for a workout with no idea of knocking my man out,” Leonard said after his retirement. “But there’d always be a loudmouth who’d start yelling, ‘Leonard, you’re a freaking bum,’ or worse. He’d keep it up and I’d get sore and quite a few guys got flattened that wouldn’t have been hurt otherwise, just because some dope in the crowd wouldn’t keep his mouth shut.”20

In his all-consuming desire to understand and master the art of boxing, Leonard set about to deconstruct and analyze every aspect of the sport. Leonard was a brilliant boxer, but he also had the heart of a warrior, and was not averse—when the situation called for it—to throw caution to the wind and mix it up. But always that nimble brain would be working overtime as he sought openings for his devastating right-hand counterpunch. He did not start out as a puncher, but after several years developed knockout power by perfecting the right combination of timing, distance, leverage, and speed, and began to score knockouts over some of the toughest lightweights who ever lived. Leonard had taken the science of pugilism to a level not seen before. Historians consistently rank him among the 10 greatest fighters, pound for pound, of all time.

Who was this man who brought a balletlike grace to the sport? He didn’t even look like a fighter. His face was unmarked, and his body, not particularly muscular. He was really a nice Jewish boy with an extraordinary talent and a driving ambition to be the best at his craft. If you didn’t know his true profession you’d think he was an accountant, perhaps a teacher or businessman—the type you could bring home to dinner and introduce to your sister.

Leonard was well-spoken (he once challenged the noted philosopher Bertrand Russell to a debate as to the merits of boxing). He took his responsibility as a representative of the Jewish people seriously, often donating his services to both Jewish and Catholic charitable causes. As noted by author Franklin Foer, Leonard’s conduct, in and out of the ring, and his impeccable public image “stood as the refutation of the immigrants’ anxiety that boxing would suck their children into a criminal underworld or somehow undermine the very rationale for fleeing to the Golden Land. Benny Leonard legitimized boxing as an acceptable Jewish pursuit—and even more than that, he helped make sports a perfectly kosher fixation.”21

Like all great artists Leonard constantly strove for perfection but was never satisfied. When asked by legendary trainer Ray Arcel why he studied four-round preliminary fighters sparring in the gym, Leonard replied, “You can never tell when one of those kids might do something by accident that I can use.”22

When it was time for his own workout to begin, every fighter in the gym stopped to watch this “professor of pugilism” shadowbox or spar. To sharpen his alertness he would sometimes spar with two boxers at the same time. The day after a fight he’d be back in the gym, talking over tactical mistakes.

“The coordination of mind and muscle was just outstanding,” recalled Arcel. “Leonard would feint you into knots. If you were a rough tough fellow he would back you up. If you were a very clever fellow and laid back waiting to counterpunch, he would draw you in, make you lead, and then have you fall short with your punches and counter. Leonard was a student of the human body. He was a place puncher who knew just where to hit you. A left hook to the liver was his favorite punch. He moved with terrific speed, in and out, in and out, side to side, and if you weren’t in perfect condition you’d be pretty tired after that first round and he would be just starting in.”

Benjamin Leiner was born on April 7, 1896, in a tenement on New York’s Lower East Side. His parents, Minnie and Gershon Leiner, were recent immigrants from Russia. Gershon struggled to support a wife and eight children by working 12- to 14-hour days in a garment-trade sweatshop for $20 a week. It was a hardscrabble life.

Benny began his professional boxing career in 1911 at the age of 15. Six years and 116 fights later he won the lightweight championship of the world via a ninth-round TKO of Freddie Welsh. It was the only time Welsh was ever stopped in 168 fights.

Less than two months after defeating Welsh, Leonard knocked out the great featherweight champion, Johnny Kilbane, in the third round. It was only the second KO loss in 122 bouts for Kilbane, who would continue to rule the featherweight division for another six years.

Leonard boasted that no fighter could muss his hair in a fight. (It helped that he plastered down his “patent-leather locks” with an industrial-strength gel that would have held up in a wind tunnel.) When Leo Johnson, the country’s outstanding black lightweight contender, attempted to unnerve him by mussing up his hair during a clinch, Leonard responded by knocking Leo out in less than two minutes of the first round. (It was only the second time in some 150 bouts that Leo Johnson was stopped; his other knockout loss had occurred six years earlier against the great Abe Attell.)

During Leonard’s tenure as champion his toughest challenger was the great Philadelphia southpaw, Lew Tendler. Their first bout took place in Jersey City. Over 50,000 fans were on hand to witness an intense and dramatic 12-round seesaw battle.

In the eighth round Tendler connected with a right to the body and left hook to the head that caused the champion’s knees to sag. Although hurt, Leonard’s hair-trigger brain came to the rescue. As Tendler closed in for the kill Leonard spoke to him. It has come down the pike as either “Keep your punches up, Lew,” or the same words (or some variation) addressed to Lew in Yiddish. Whatever was said, in whatever language, it was enough to cause Tendler to hesitate for the few seconds Leonard needed to clear his head and recover his equilibrium. The 12-round bout was “no-decision,” so there was no official winner or loser. A majority of newspapers covering the match had Leonard winning a close 12-round decision. Several others either named Tendler the winner or scored it a draw.

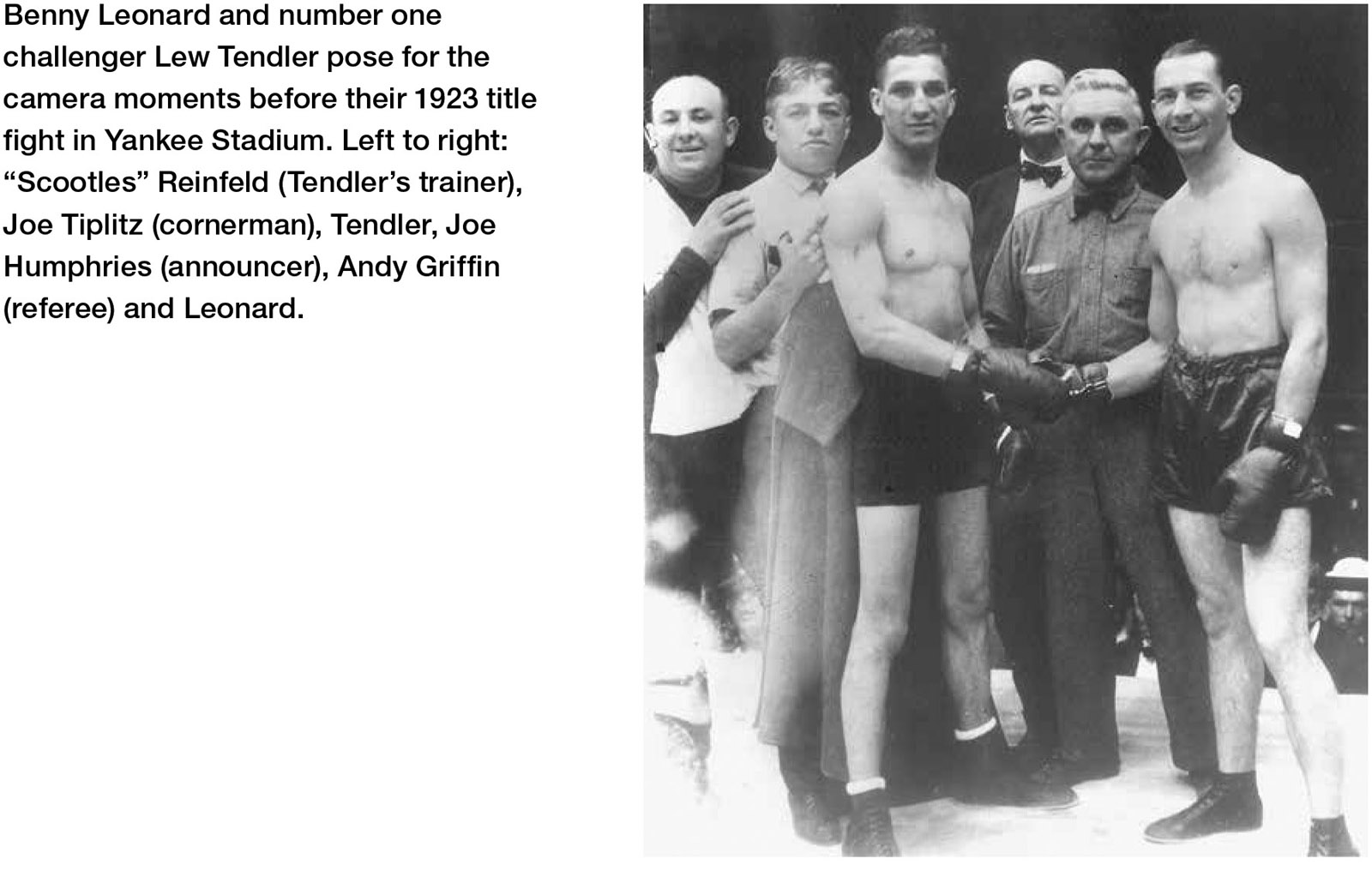

The highly anticipated rematch took place on July 22, 1923, in Yankee Stadium, one year after their first meeting. Sixty-three thousand fans witnessed the two great Jewish boxers fight it out for the lightweight championship of the world.