The United States today is the greatest fistic nation in the world, and a close examination of its 4,000 or more fighters shows that the cream of its talent is Jewish.

—BOXING ANNOUNCER JOE HUMPHREYS, 1930

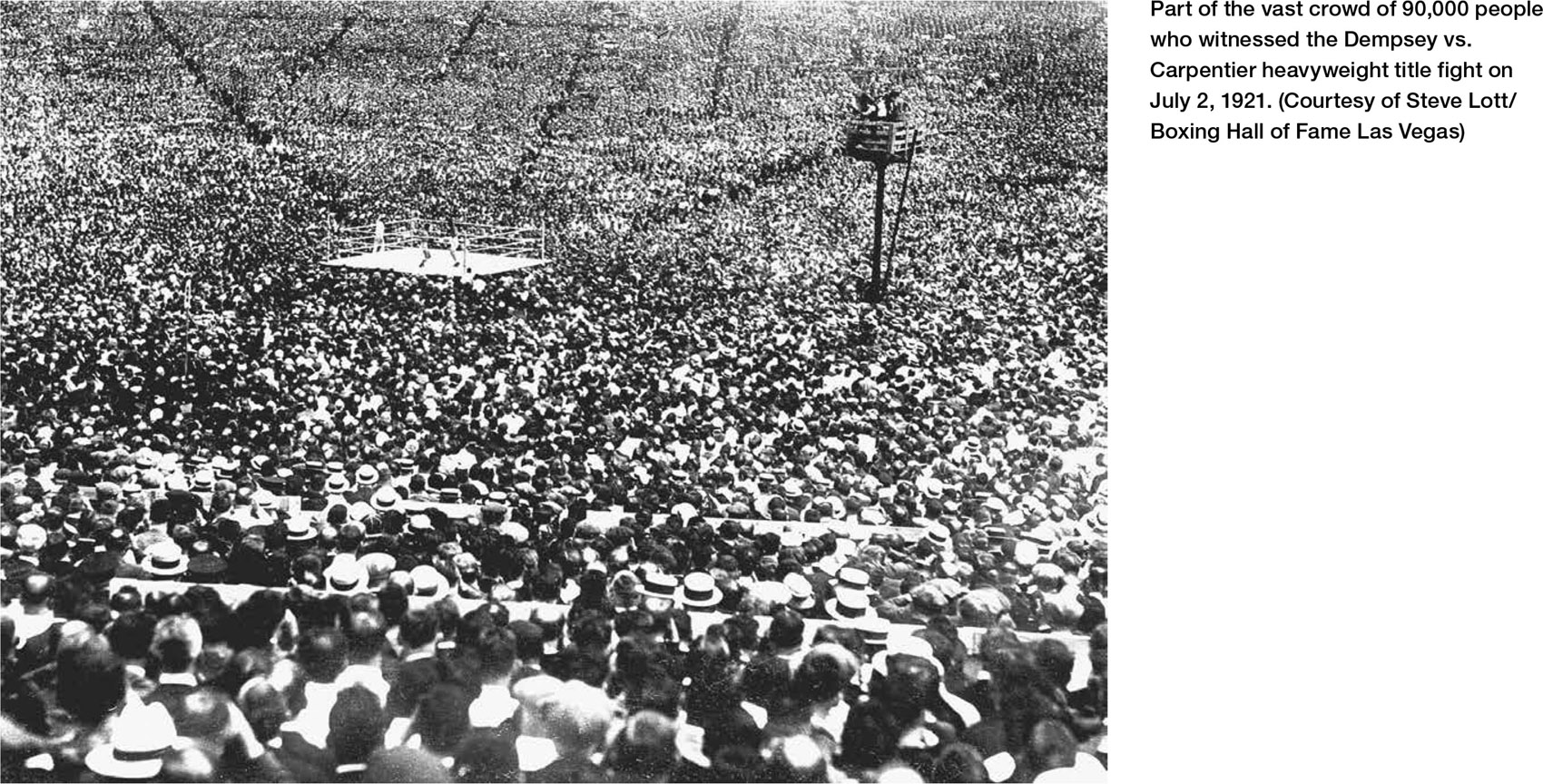

The year 1921 was a watershed year for the sport of boxing, thanks to the efforts of the great promoter, George Lewis “Tex” Rickard, and a superstar heavyweight champion named Jack Dempsey. On July 2, 1921, Rickard staged a heavyweight title bout between Dempsey and challenger Georges Carpentier of France. Carpentier, the light-heavyweight champion of the world, was a debonair Frenchman and World War I hero with movie-star looks.

Jack Dempsey, a steel-hard ex-hobo and mining-camp brawler, was one of the most destructive forces ever seen in a prize ring. He stood a shade over six feet and weighed 187 pounds. “The Manassa Mauler”—named for his birthplace in Manassa, Colorado—was an electrifying presence in or out of the ring. No other athlete of his time so embodied the unsettled nervous energy of the Roaring Twenties.

In his 1960 biography, Dempsey, of Scotch- Irish parentage, claimed a Jewish connection: “I am basically Irish, with Cherokee blood from both parents, plus a Jewish strain from my father’s great-grandmother, Rachel Solomon.”1

If Tex Rickard had known of Dempsey’s remote Jewish ancestry, the PR-savvy promoter might have advertised the rugged slugger as a former yeshiva student turned heavyweight boxer. But it wasn’t necessary. Dempsey’s charisma would carry the day. Rickard added to the excitement by using the press and movie newsreels to fan the flame of public interest into a roaring fire.

On the day of the fight over 90,000 fans—the largest crowd to ever attend a sporting event up until that time—paid their way into a huge monolithic wooden stadium (a structure built especially for the occasion) located on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River.

Ringside seats went for $50 apiece (the cheapest seats cost $5.50). Telegraph operators seated in the press section transmitted a round-by-round summary of the fight around the world, and for the first time the new medium of radio was used to broadcast a blow-by-blow account of a championship-boxing match. Stars of stage and screen, giants of commerce, mayors, governors, and senators were sprinkled throughout the ringside spectators.

The result of the Dempsey-Carpentier extravaganza (Dempsey flattened the overmatched Frenchman in four rounds) was less important than the significance of the event. For the first time in history a sporting event had drawn over one million dollars in paid admissions ($1,785,000, to be exact). Jack Dempsey was paid $300,000 for less than 12 minutes of work.

Before the decade was over, four more million-dollar gates featuring Dempsey and promoted by Rickard would enthrall the entire nation. In two of those fights the live attendance figures exceeded 100,000 persons.

During the 1920s boxing reached unprecedented levels of popularity with the general populace, even eclipsing baseball in terms of live attendance figures and newspaper coverage. Heavyweight title fights became the most lavish and anticipated spectacle in sports. The social, artistic, and cultural dynamism of the Roaring Twenties, in concert with the media’s focus on celebrities (especially sports heroes and movie stars), glamorized boxing and made Jack Dempsey the first boxing superstar of the twentieth century. But due credit must be given to the promotional genius of Tex Rickard. Under his watch boxing gained a respectability it had never known before, and was transformed into popular entertainment for a mass audience. The business of sports entertainment would never be the same.

The record-breaking gate receipts of the Dempsey-Carpentier fight convinced other states to reconsider their anti-boxing laws. The realization that substantial tax revenues and other ancillary income could be generated by professional boxing pushed them into the fold. Whereas in 1917 only 23 states had officially legalized the sport, by 1925 the number was up to 43.

Boxing gyms and arenas seemed to pop up everywhere. Much like traveling vaudevillians, professional boxers utilized America’s extensive rail system to go from city to city. Most kept to a busy schedule by fighting every two or three weeks. The constant activity kept them sharp and in fighting trim. There were so many boxing venues, especially in major population centers, that even a lowly bucket carrier could earn a modest living working corners up to six nights a week.

New York City quickly regained its position as the boxing capital of the world. The energy, ambition, and creativity of the world’s greatest city found its way into every aspect of the sport. New York had more fighters, trainers, managers, gyms, and arenas than any other metropolis, and it was home to boxing’s holiest shrine—Madison Square Garden.

In 1920, after a three-year moratorium, professional boxing returned to New York State with the passage of the “Walker Law.” Under the new law a reorganized State Athletic Commission would be responsible for collecting taxes and issuing licenses to boxers, managers, promoters, matchmakers, corner men, referees, judges, and medical personnel. It also attempted, with mixed results, to curtail gambling and criminal infestation.

Boxers and fans rejoiced when the first edict of the commission was to rescind the state’s “no-decision” rule. The new law mandated that the outcome of any bout that did not end in a knockout was to be decided by the scorecards of a referee and two judges. A boxer’s ability to outpoint his opponent would now be officially rewarded. Other states followed New York’s lead, and by the early 1920s, the no-decision era was history.

The boxing industry also realized the need to create a more-formal system for recognizing world champions. The aforementioned New York State Athletic Commission, the 23 member states of the newly formed National Boxing Association (NBA), and the European Boxing Union were the sport’s three main governing bodies. New York, the epicenter of the boxing universe, did not join the NBA, preferring to maintain its independence. California, the second-busiest boxing state, also had a powerful and prestigious boxing commission, and on a few occasions recognized its own world champions.

Although there were occasional disputes, these organizations, more often than not, recognized the same world champions, especially when it came to the sport’s most important title—the heavyweight championship.

The champions featured in this section were recognized by at least one or more of these respected organizations, but it should also be noted that possessing a title did not necessarily mean a particular fighter was the best in his weight class. In the various all-time ratings at the back of this book, some boxers who never won a title are placed ahead of some who did. Not every championship-caliber boxer actually won a championship.

The 1920s represented the pinnacle of boxing activity in the United States.

New York City’s active fight scene reflected the robust health of the sport throughout the rest of the country. As boxing grew in popularity, so did the number of boxers. In 1927 the New York State Athletic Commission issued licenses to 2,000 professional boxers who resided in the Empire State (up from 1,654 in 1925). California issued an equal number of licenses to their resident pro boxers. The two busiest boxing states—New York and California—supervised a combined total of 1,800 boxing promotions. (In 2012 the total number of professional boxers in the United States was less than 3,500, and annual promotions, under 1,000.)2 By 1932 there were approximately 8,000 licensed professional boxers throughout the world.3

The first rating system for boxers was started in 1921 by the National Boxing Association. In 1925 The Ring magazine began an annual rating of the top 10 fighters for each of nine weight divisions (later expanded to 10 weight divisions). Three years later the magazine switched to a monthly ratings format.

From the 1920s to the 1960s, both The Ring and the NBA published separate top-10 contender lists for each weight division. No rating system is perfect, or completely unbiased, but in this time frame the listings of both organizations were considered to be reliable and trustworthy. They were also consistently similar, thereby giving the ratings a semblance of order and legitimacy that is sorely missing today.

In the 1930s boxing in America suffered economically along with the rest of the country during the Great Depression. Revenues and attendance figures declined. Promoters were forced to drop ticket prices as they struggled to stay in business. At one point Madison Square Garden was charging only 40 cents for balcony seats. Journeymen boxers, often fighting for a percentage of the gate, were barely able to cover travel expenses.

By 1933, 50 percent of Americans between the ages of 15 and 19 were unemployed. Young men with few job prospects entered the prize ring to earn a few dollars and hopefully avoid the relief rolls. In the United States more pro boxers were licensed annually during the 1930s than in any previous decade, but only the champions and leading contenders could make a decent living.

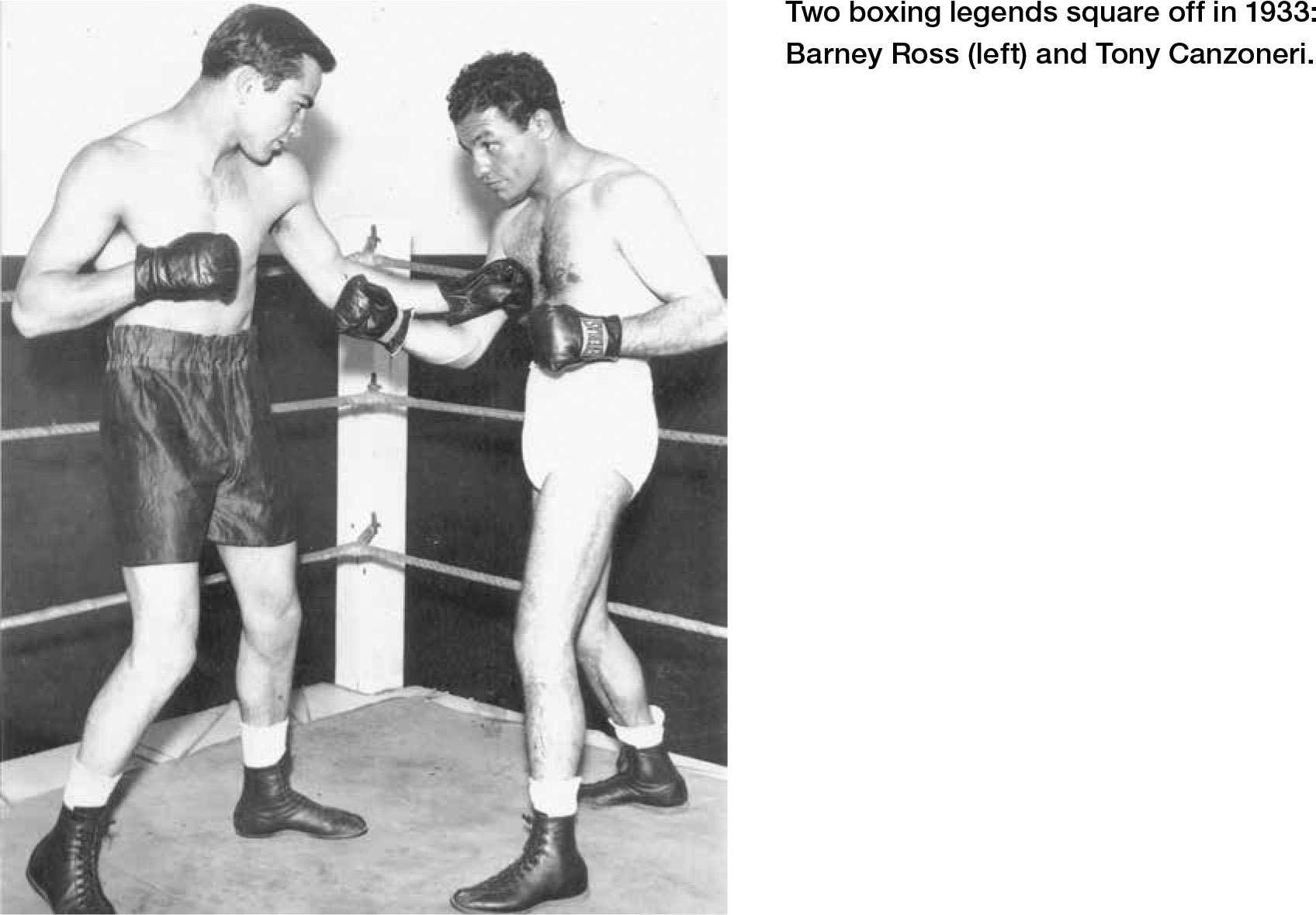

Yet despite the economic hardships the anticipation of a great fight could still draw a huge audience, even in Depression-era America. In the mid-1930s the Barney Ross vs. Jimmy McLarnin welterweight title trilogy drew over 100,000 fans. In 1935 a non-championship heavyweight match between Max Baer and Joe Louis drew 83,000 fans to Yankee Stadium and generated one million dollars in revenue.

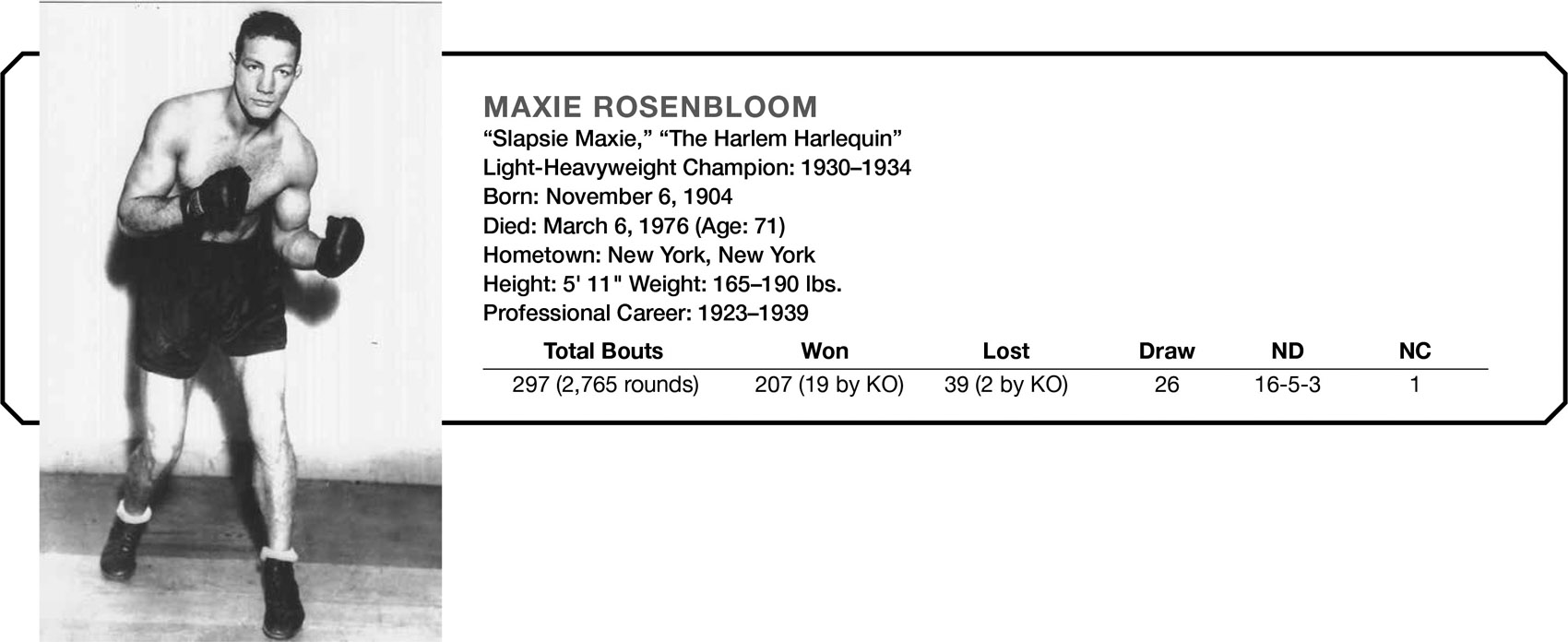

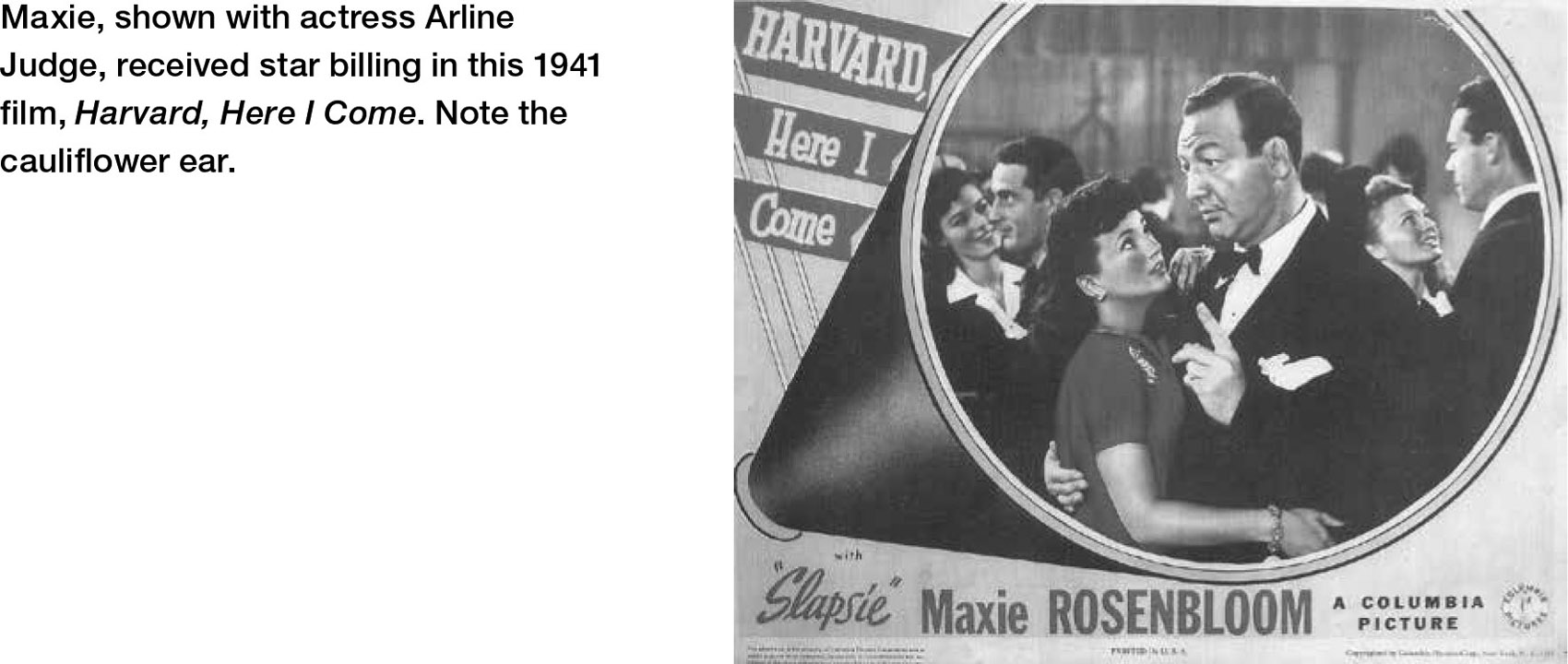

While the economy was in decline, boxing’s deep well of talent was not. The 1930s produced dozens of all-time great fighters, in addition to hundreds of outstanding contenders. A partial roll call of the decade’s finest reveals an astonishing array of super athletes: Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong, Barney Ross, Tony Canzoneri, Jimmy McLarnin, “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom, Charley Burley, Lou Ambers, Billy Conn, Fritzie Zivic, Kid Chocolate, Holman Williams, Jackie “Kid” Berg, John Henry Lewis, Freddie Miller, Tony Zale, Benny Lynch, Freddie Steele, and Panama Al Brown, just to name a few.

The professional boxing industry has always been fertile territory for exploitation by professional gamblers because of the ease with which a fight could be fixed by either influencing one of the contestants or bribing a referee or judge. During the Prohibition Era (1920–1933) mobsters were usually too busy making tons of money from illegal booze to become overly involved with boxing. Managing a fighter, like owning a racehorse, was a glamorous and lucrative sideline activity. Fixing the occasional boxing match or horse race came with the territory.

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Mob interest in big-time boxing accelerated as new sources of income were sought. The syndicate’s greatest coup was their taking control of the giant Italian heavyweight, Primo Carnera. Most boxing historians believe Carnera won the heavyweight championship in a fixed fight against Jack Sharkey in 1933. Nonetheless, fixed fights, although not uncommon, were the exception rather than the rule. Most of the thousands of professional bouts that took place every year were fought on the level.

It is no coincidence that the Golden Age of the Jewish boxer in America coincided with the Golden Age of the Jewish gangster. Both came from the same gritty rough-and-tumble city streets, and their worlds often intersected. In 1921 Jews represented 14 percent of New York State’s prison inmate population. By 1940, the figure had dropped to 7 percent. Jewish juvenile delinquency rates paralleled these trends, declining from 21 percent of all juveniles arraigned in 1922 to 8 percent in 1940. Women were also not immune to the consequences of poverty. In 1910, Jewish women accounted for 20 percent of all female prisoners in New York State. Thirty years later the number was down to 4 percent.4

The declining rates of criminality among the Jewish populations of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other major urban centers indicated steadily improving social and economic trends. But as long as boxing remained lucrative, criminal infiltration would remain a part of the industry’s subculture, no matter what ethnic groups were involved. Jewish mobsters such as Waxey Gordon, Arnold Rothstein, Dutch Schultz, and Max “Boo Boo” Hoff operated as undercover managers, since their criminal records disqualified them from obtaining a legitimate manager’s license. Their connections could help a promising boxer by securing important bouts that would advance his career—but they could also order the boxer under their control to throw a fight. Little was done to thwart underworld influence. Ineffective state boxing commissions, mostly staffed by political hacks and bureaucratic ciphers, rarely made any attempt to clean up the sport.

While the tough ghetto neighborhoods were breeding grounds for both Jewish boxers and Jewish criminals seeking ways to earn quick money, it did not mean they were one and the same. They were not. While only a small proportion of the total number of poverty-stricken inner-city Jewish youth became professional boxers, an even tinier fraction turned to a life of crime. It was no different for Irish-, Italian-, Greek-, Polish-, and African-American boxers. The vast majority of professional boxers of every race and ethnicity were law-abiding citizens, and they remained that way even after coming in contact with the unsavory characters that inhabited their world.

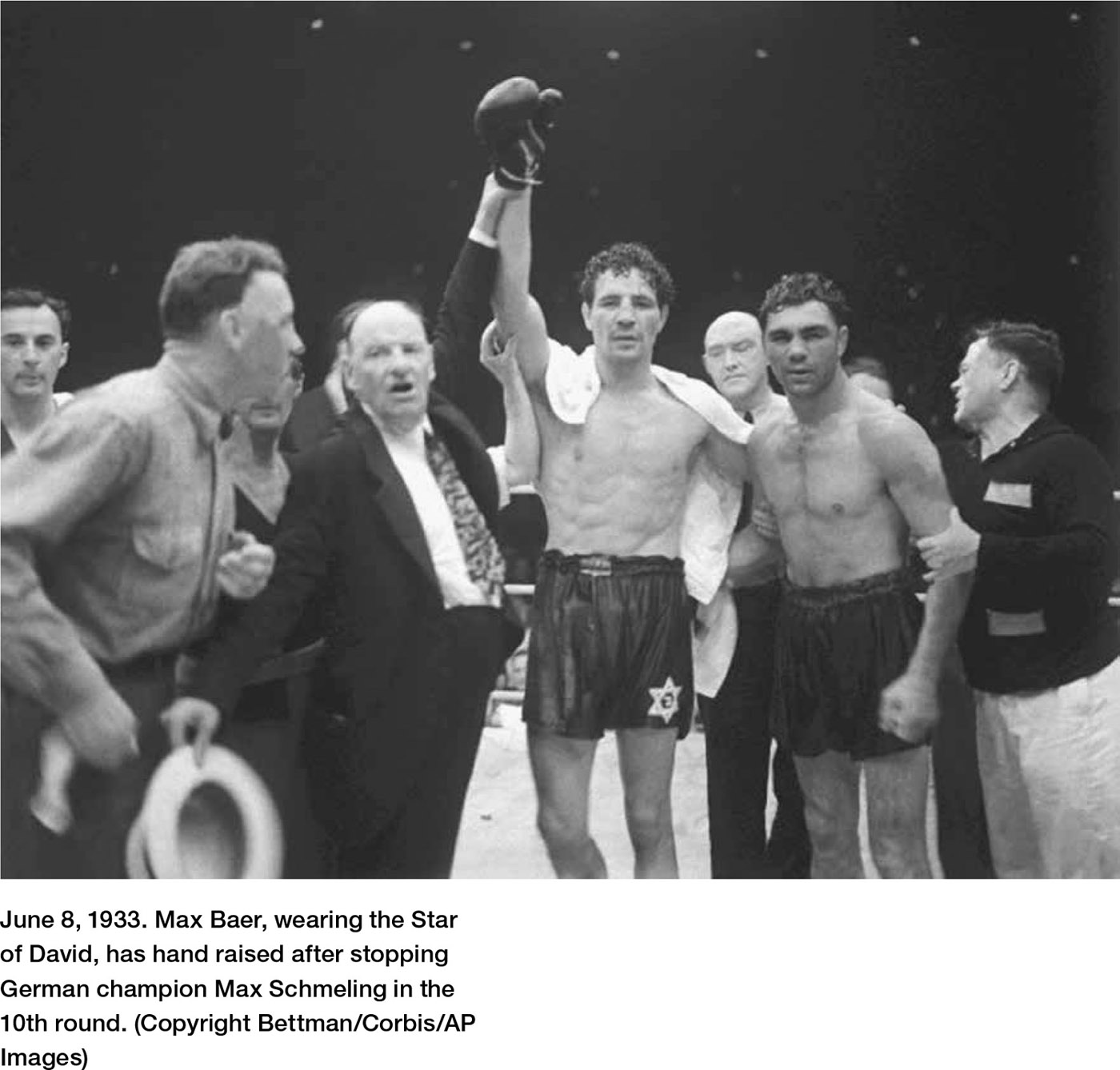

On June 8, 1933, over 60,000 fans attended an important boxing match at New York’s Yankee Stadium between the colorful American heavyweight contender Max Baer and Germany’s Max Schmeling, a former heavyweight champion of the world. Five months earlier the Nazis had taken control of Germany, and almost immediately began a policy of state-sponsored anti-Semitism. At the time Max Baer was generally assumed to be Jewish, but in fact he was the son of a half-Jewish father and a Protestant mother of Scotch-Irish descent. He was not raised in the religion, and it is not clear that he ever considered himself Jewish. Nevertheless, fighting Nazi Germany’s best boxer in a city with the largest Jewish population made it important for Baer to emphasize his Hebrew heritage. At the suggestion of his Jewish manager, Ancil Hoffman, for the first time he entered the ring wearing the Star of David on his trunks—something that he would do for the rest of his career. Baer left no doubt about his intentions when he told reporters, “Every punch in the eye I give Schmeling is one for Adolf Hitler.”5

Jewish fans flocked to the stadium in hopes of seeing just that, even though the betting odds heavily favored Schmeling. They were not disappointed. The end came suddenly in the 10th round when Baer, a murderous puncher, dropped Schmeling with a thunderous right hand to the jaw. Upon arising at the count of nine Schmeling was subjected to a series of brutal punches before the referee stopped the fight. With his victory Baer became an instant hero to Jews throughout the world. The following year he would win the heavyweight championship of the world.

Whether Max Baer was Jewish or not, at that moment in time—facing a German opponent who was seen as a representative of the Nazi regime—he chose to identify himself with the Jewish people. His army of Jewish fans was forever grateful for the stand he took, both in and out of the ring.

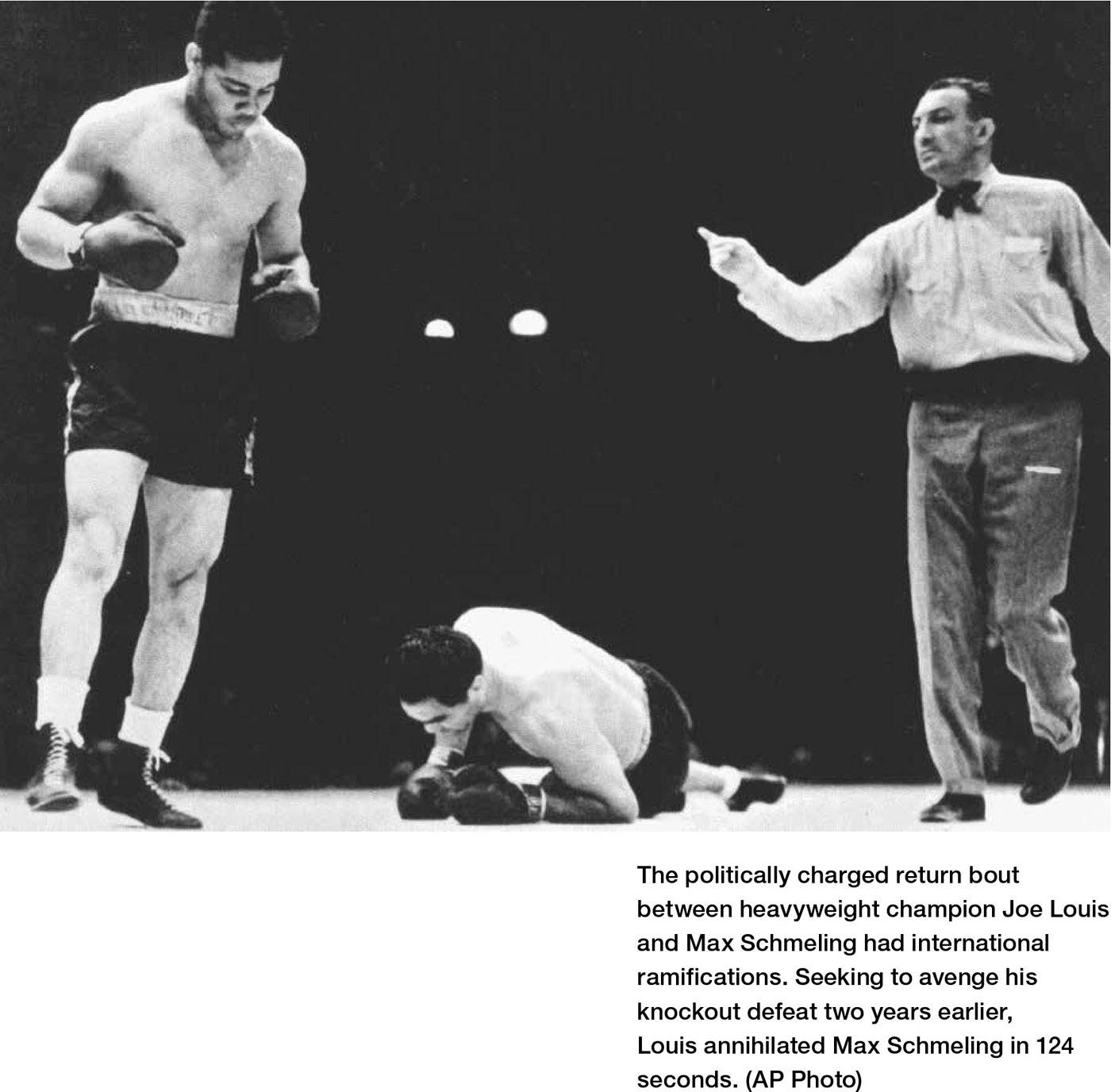

The victory of Max Baer over Germany’s Max Schmeling in June 1933 occurred at a time when the Third Reich, despite its insidious internal racial policies, was still in its infancy, and not yet perceived by the United States as a potential threat. But by mid-1938 that view had drastically changed. Not only did Nazi Germany possess one of the most powerful armies in the world, but its aggressive expansionist policies were threatening world peace. At the same time, Max Schmeling, mirroring Germany’s ascendancy, had staged a dramatic comeback after his loss to Baer, which included a tremendous upset victory over the seemingly invincible Joe Louis in 1936. Louis had been undefeated in 27 fights, including 23 by knockout. Sixteen of his victims had never made it past the fourth round. Louis was an 8–1 favorite to defeat Schmeling. In a sensational upset Schmeling punished Louis severely before knocking him out in the 12th round. Schmeling instantly became a huge national hero in Germany, and the Nazi propaganda machine used his victory as proof of Aryan racial superiority.

The return bout between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling for the heavyweight championship of the world took place in Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1938. On the eve of World War II, the highly anticipated contest took on a heavy symbolism. Louis represented democracy and the civilized world, while Schmeling was vilified in the American press as a representative of Hitler. (Despite his status in Germany, Max Schmeling never joined the Nazi party. Nevertheless, as international tensions worsened, Schmeling was seen as an extension of the evil Nazi regime. From the moment Hitler came to power in 1933, comments writer David Margolick, Schmeling “had walked a tightrope, seeking simultaneously to please the Nazis while maintaining his relations in New York, the world capital of boxing.”6)

The fight turned into a transcendent event. No other sporting contest had ever aroused more passion or worldwide interest. Over 70,000 fans were on hand to witness it in person, while another 100 million listened, transfixed to their radios. It is believed to be the largest audience for a single radio broadcast up until this point. Randy Roberts writes: “No event had ever attracted an audience that large—not a sporting event, a political speech, or an entertainment show.”7

Seeking revenge for his humiliating defeat two years earlier, Louis relentlessly attacked Schmeling. The savage beating took only 124 seconds of the first round before the referee stopped the one-sided fight—the second-shortest title fight in heavyweight history. On that night Joe Louis became an American icon and the entire nation, black and white, celebrated his great victory. African Americans were euphoric, as were Jews throughout the world, who rejoiced over “The Brown Bomber’s” utter destruction of a representative of “the master race.”

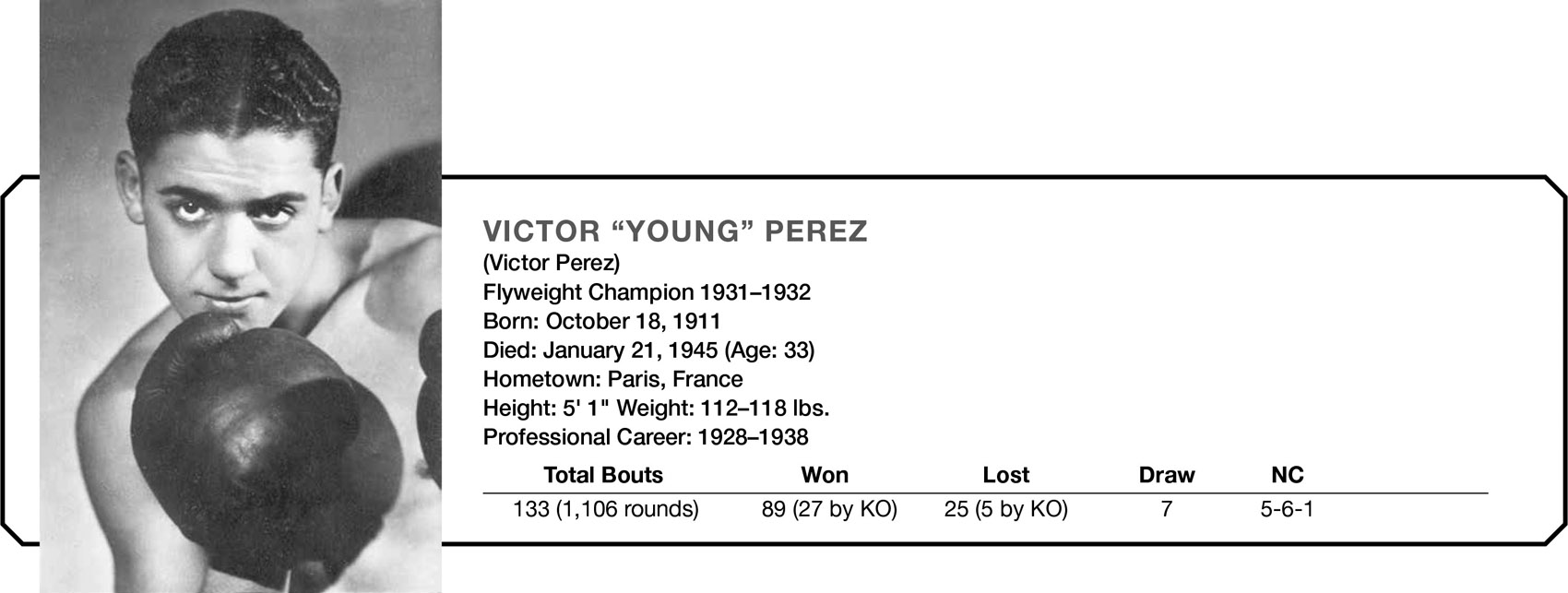

In the years between the two world wars, Jewish sporting clubs sprang up throughout Europe—in Poland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Holland, and France. Jewish athletes from these countries excelled in many sports, winning titles in soccer, boxing, fencing, gymnastics, weightlifting, and table tennis. Hungarian Jewish athletes were especially adept at fencing. From 1896 to 1936 they won 14 gold medals in Olympic competition. The majority of Jewish boxers on the European continent remained amateurs, although several dozen achieved success as professionals, either as world champions or leading contenders, most notably Victor “Young” Perez (Tunisian-born French champion who won the world flyweight title in 1931), Leone Efrati (Italian featherweight who challenged for a world title in 1938), Kid Francis (Italian-born French bantamweight champion who challenged for a world title in 1932), and Erich Seelig (German middleweight and light heavyweight champion, 1931–1933).

During the inter-war years soccer remained the number-one sport in Europe. In the 1920s the famous Hakoah soccer team of Vienna attracted the best Jewish players in Central Europe. The team won the Austrian National Championship in 1925. The following year it toured the United States and drew over 26,000 fans to a match at the Polo Grounds in New York City.

The International Maccabee movement was the most popular of the many Jewish athletic clubs in Europe. It had been organized in 1903, and by the early 1930s numbered 200,000 Jewish athletes in 27 countries.8 Talented amateur boxers representing the Maccabee and various other Jewish sports organizations won national boxing titles in Poland, France, Italy, Germany, England, and Greece.

Poland had the second-largest Jewish population in the world next to the United States, so it is not surprising that it also had more Jewish athletes than any other European nation. By 1936 there were 150 Maccabee athletic clubs in Poland, with some 40,000 members.9 The idea of a “muscular Judaism”—the phrase coined by Max Nordhau at the second Zionist Congress in 1898—was especially strong in the Polish Maccabee clubs that were home to many distinguished amateur athletes.

In July 1933, six months after the Nazis came to power in Germany, the Maccabee organization relocated its world headquarters from Berlin to London, noting that “there was no longer any place for Maccabi under the bestial Hitler activities.”10 But for many of the athletes who remained in Europe during the gathering storm, both professionals and amateurs, there was no escape. Several of Germany’s top Jewish boxers fled the country in 1933. Harry Stein emigrated to Prague and then to Moscow. That same year Erich Seelig fled to France, and eventually to the United States via Cuba in 1935. Leone Efrati, Victor Perez, and Kid Francis were murdered in the Holocaust.

The German army’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, ignited World War II. Over the next six years the Nazi occupiers and their collaborators carried out the systematic murder of six million Jews, including 90 percent of Poland’s prewar Jewish population of three million.

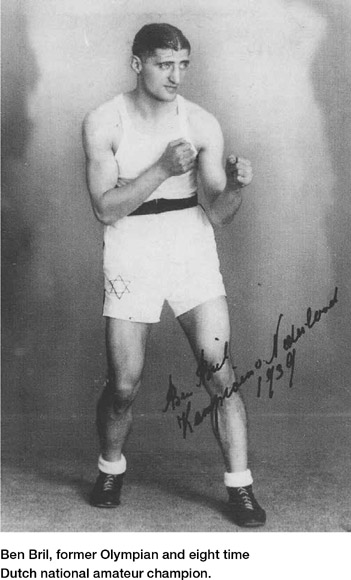

A few Jewish boxers were able to survive the death camps by fighting for the amusement of Nazi guards, as did Salamo Arouch and Jacko Razon, former Greek amateur champions. Literally fighting for their lives, they were given an extra ration of food after each victory. The loser was invariably shot or gassed. Another survivor was Amsterdam’s Ben Bril, that country’s outstanding amateur boxer, who competed in the 1928 Olympics and won a gold medal in the flyweight division at the 1935 Maccabiah Games. He won the Dutch national amateur championship eight times, but was barred from the 1932 Summer Olympics because the head of his country’s Olympic committee was a member of the Dutch Nazi party. Four years later Bril boycotted the 1936 Games in Berlin.

During the German occupation of the Netherlands Bril was deported and imprisoned at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. He and a younger brother survived to the end of the war, but his other five siblings (all but one were married with children) died in the camps.

After the war Ben Bril returned to the Netherlands and stayed active in boxing as a referee, officiating important fights throughout Europe. Bril is a boxing legend in the Netherlands, and was the subject of a book and movie based on his life. After his passing in 2003, the annual Ben Bril Memorial Boxing Gala was inaugurated to honor his memory. The event features a series of boxing matches held every October in Amsterdam.

The country with the most Jewish boxers outside of the United States was England. From 1881 to 1914 over 150,000 Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe settled in London, increasing that country’s Jewish population to 250,000 (about one-eighth of the population that resided in America).

Most lived in the East London areas of Whitechapel, Shoreditch, Aldgate, Stepney, Bethnal Green, and Hackney.11 At the turn of the last century the poorest sections of these enclaves matched New York City’s Lower East Side for their poverty and squalor. So it is not surprising that thousands of London’s Jewish youths took up boxing in an effort to quickly improve their economic circumstances. Boxing held enormous significance for the country’s Jews, especially among the working class. Once the country’s national sport, boxing has a rich and storied history in England, and Jewish boxers, beginning with Daniel Mendoza in the late 18th century, were a significant part of it. As in America, the boxing experience in England facilitated the ongoing integration and upward social mobility of the Anglo-Jewish population, while at the same time countering negative anti-Semitic stereotypes.

Outside the ring Jewish entrepreneurs in London were instrumental in sustaining a thriving boxing industry. From 1894 through the 1930s they opened at least five popular boxing halls in the East End Jewish community.12 The most popular among them were the Judean Club and Premierland Arena. Most Jewish boxers got their start at these two legendary arenas.

The amateur boxing network in Britain that nurtured and developed future professional stars was extensive. The largest Jewish amateur boxing clubs were located in London and Manchester. They performed with amazing success. Between 1921 and 1939 the boxing teams, known collectively as the Jewish Lads’ Brigades (JLB), won the Prince of Wales Shield (the preeminent tournament for all British youth clubs) 12 times. In six of these tournaments the final was contested between the London and Manchester JLBs.13

Professional boxing activity and participation were greatest during the Great Depression. In the 1930s Great Britain averaged an incredible 3,500 shows per year.14 (Since 1961 the annual numbers rarely exceed 200 shows.)

Between 1908 and 1935 Anglo-Jewish professional boxers won 13 British titles and four world championships. Ted “Kid” Lewis (Welterweight Champion 1915–1916, 1917–1919), a Jewish boxer from East London, is considered by many historians to be the greatest British boxer of all time. A partial list of the best Anglo-Jewish professional boxers of the Golden Age includes Sid Smith (flyweight champion), Young Joseph, Matt Wells (welterweight champion), Harry Mizler, Jackie “Kid” Berg (junior lightweight champion), Jack Goldswain, Harry Mason, Harry Reeve, Jack Hyams, Phil Lolosky, Jimmy Lester, Johnny Brown, Young Johnny Brown, Joe Fox, Jack Bloomfield, Benny Sharkey, Solly Schwartz, Benny Caplan, Phil Richards, Al Phillips, Harry Lazar, and Lew Lazar. The fabulous history of Anglo-Jewish boxers deserves an entire book of its own.

Over the past quarter-century professional boxers have averaged between 15 and 30 bouts and less than 150 rounds before winning a title. From the 1920s to the 1950s the averages were 71 bouts and 479 rounds. In both eras it took about four to five years of activity to accumulate those numbers.15

Economic necessity was the main reason the old-timers fought so often. The bouts provided steady income. The goal was to accumulate a decent-size nest egg before retirement. Fighting often had other benefits. It was not just the number of fights and rounds that helped to season and sharpen the skills of the Golden Age pros—it was also the competitive quality of those rounds. By the time a boxer achieved contender status he’d already gained enough experience to improvise and adjust his strategy when faced with a variety of different styles. If staggered or hurt by a punch, he knew how to clinch, stall, run, slip, bend, roll, and weave his way out of trouble. Such fighters were very difficult to stop.

An undefeated record is not that difficult to establish if a fighter consistently meets inferior opposition. Years ago it wasn’t that important to remain undefeated. Managers expected their fighters to win, but were not always sure they would. At some point the fighter had to be tested, and if the outcome was a loss, it was seen as a learning experience, providing the fighter was not seriously overmatched and damaged. Losses were considered an accepted part of the learning process.

“One of the biggest differences between then and now was that the manager wasn’t burdened with navigating to protect the fighter from losing,” explained ESPN boxing analyst Teddy Atlas. “There wasn’t the pressure that there is today to remain undefeated. You could let the fighters get the fights that were going to let them develop—win or lose. It was just a matter of fighting and getting better . . . fighting and moving up . . . and trying to get to Madison Square Garden. That’s all that mattered.”16 Boxing historian Kevin Smith agrees: “It wasn’t a big deal to lose back then as it is now,” says Smith. “Losses were considered a lot more like baseball in that you lose a game and you go on and try to win the next series.”17

As was the case in the previous generation of boxers, even the best had trouble maintaining undefeated records because the top men often fought each other. The low knockout percentages of the old-timers did not mean they were not hard punchers. It was rather an indication of the type of competition they faced month after month, and the fine defensive skills they had mastered. An undefeated prospect with a long winning streak and a high percentage of knockout victories aroused suspicion among the cognoscenti because it was so unusual.

Even journeymen boxers with mediocre records were capable, on a good night, of pulling an upset and defeating a top-ranked contender, or even a world champion. As Kevin Smith notes: “If you look at any of the 1920s fighters, even an ordinary main event fighter from some obscure tank town, you are going to recognize names on his record. These guys fought each other. There was not as much avoiding competitive fights as there is today. They went where the money was and it didn’t really matter a lot of times who it was they were fighting. Every fight was experience. Most fighters of that era had 100 or more fights.”18

One of the many ways boxing has veered off course in recent years is the importance placed on win-loss records by the media and fans. Boxing, unlike baseball or basketball, is not a sport of statistics. One cannot determine the quality of a fighter by simply counting up the wins and losses on his record. The classic example is Fritzie Zivic, whose record showed over 30 losses in 129 fights when he upset the great Henry Armstrong to win the welterweight championship in 1940.

There are champions and contenders profiled in this section whose win-loss records are inferior to lesser boxers who would not stand a chance against them. When evaluating the quality of a Golden Age gladiator, one must go beyond mere statistics. The main question is how well, and for how long, did the fighter perform against top competition? Also strongly influencing my selections was the length of time a fighter’s name appeared in The Ring’s listing of top 10 contenders for his weight class. Extra consideration was given to those fighters who maintained a rating for at least several months or longer. In a few instances a fighter who otherwise might not have made it into the book is mentioned because his story is compelling from a historical or human-interest perspective. All of the boxers reached their prime between 1920 and 1940.

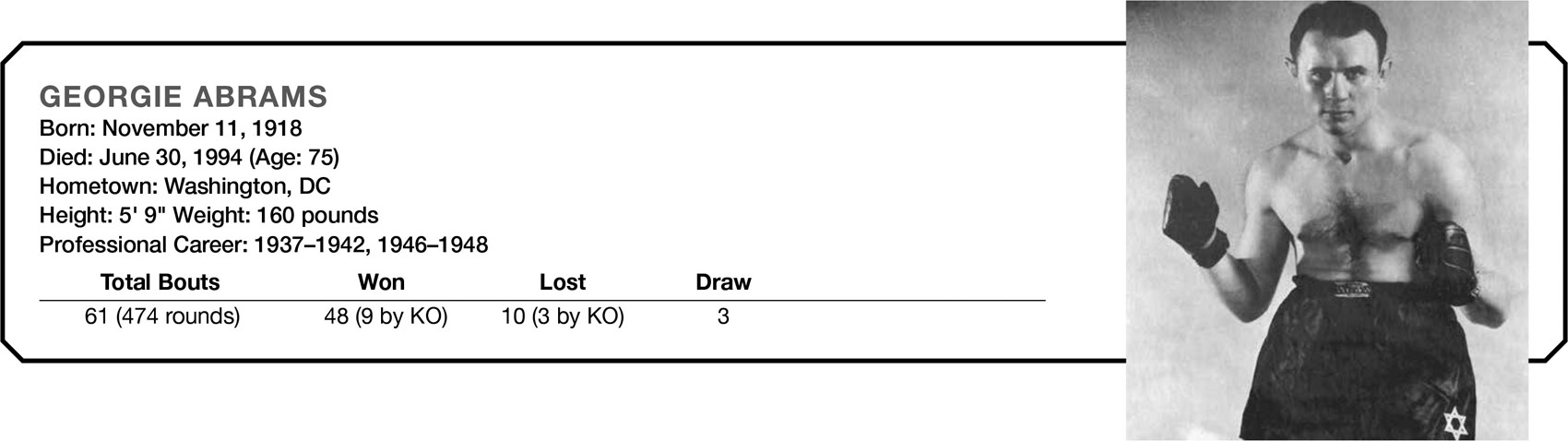

Georgie Abrams

Nat Arno

Milt Aron

Abie Bain

Benny Bass*

Sylvan Bass

Archie Bell

Joe Benjamin

Jackie “Kid” Berg*

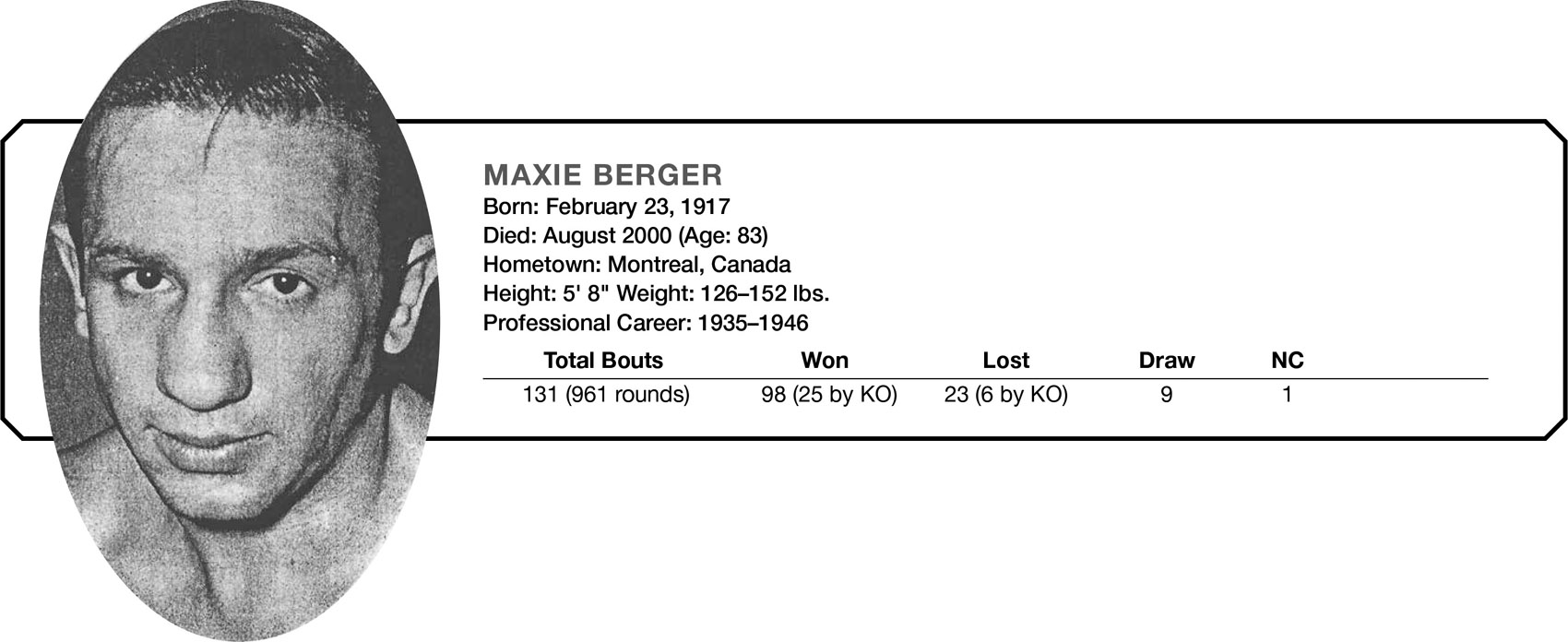

Maxie Berger

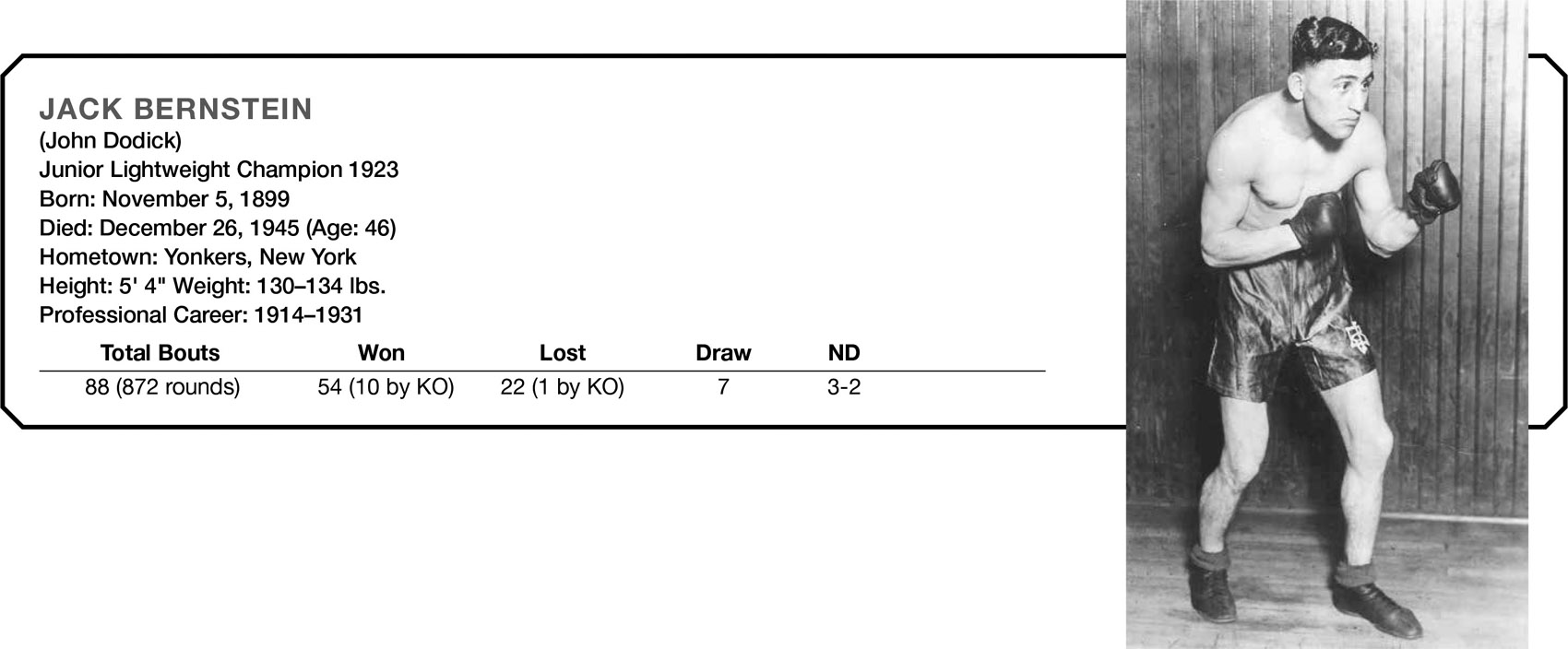

Jack Bernstein*

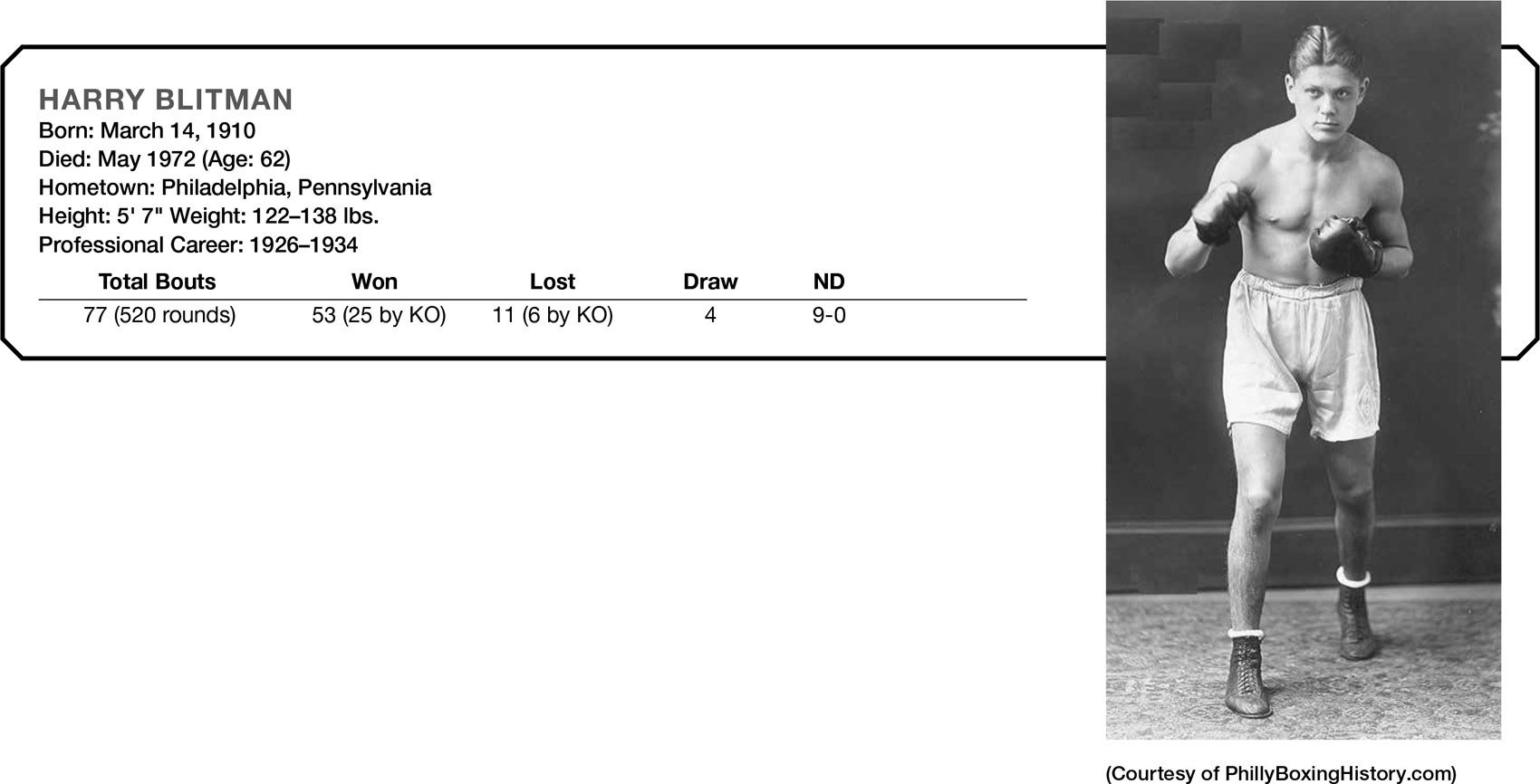

Harry Blitman

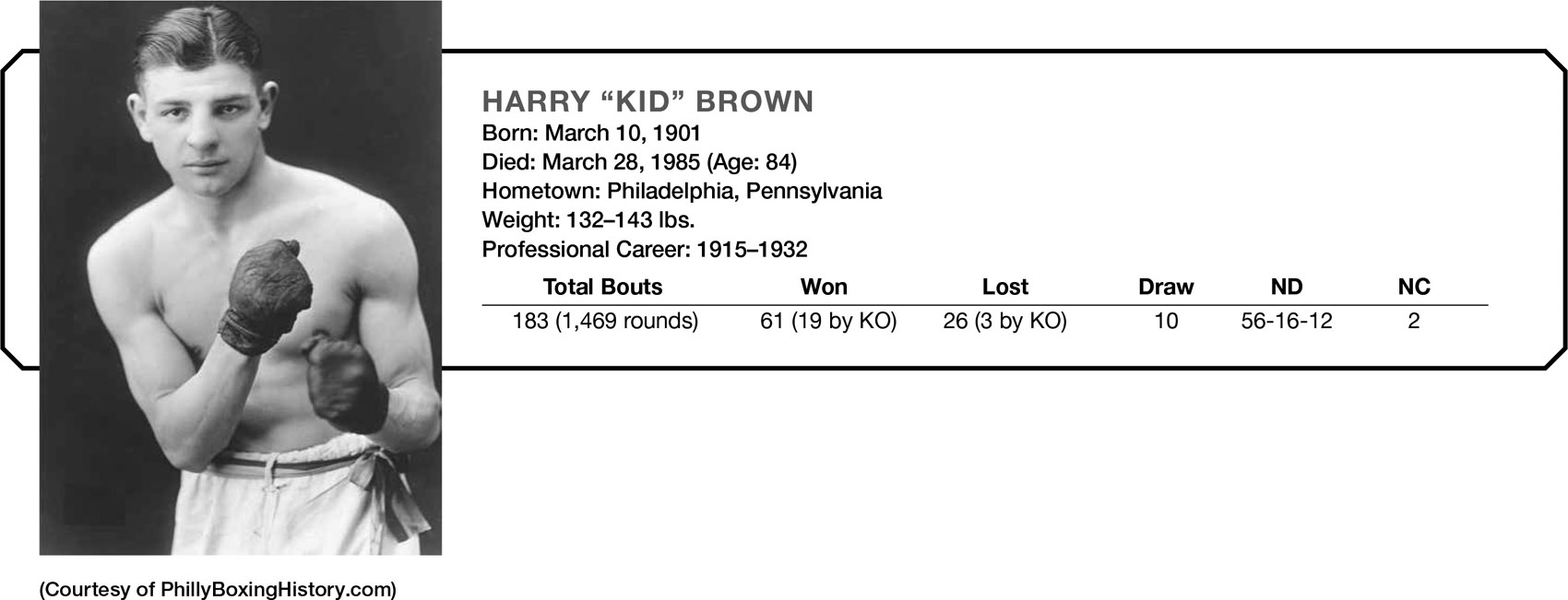

Harry “Kid” Brown

Johnny Brown

Natie Brown

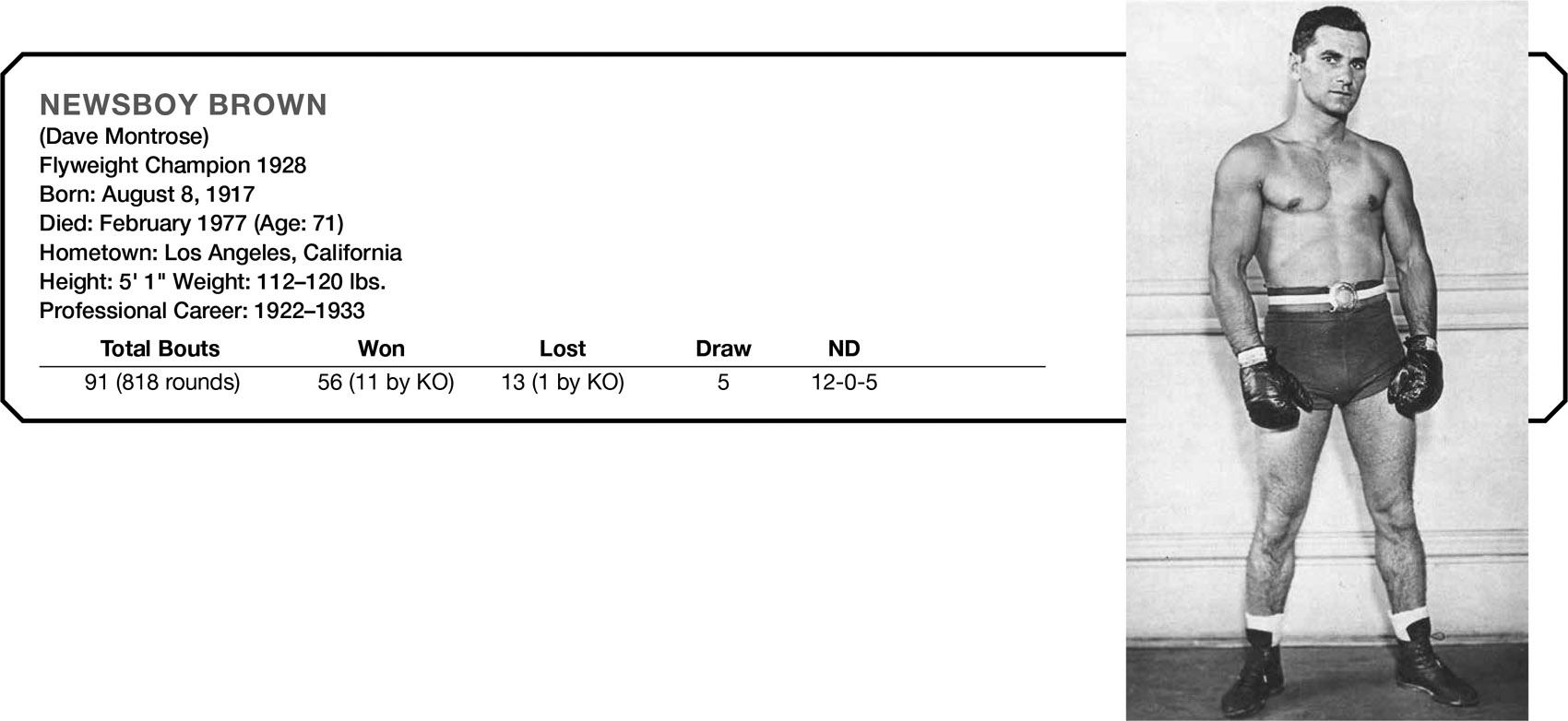

Newsboy Brown*

Joe Burman

Mushy Callahan*

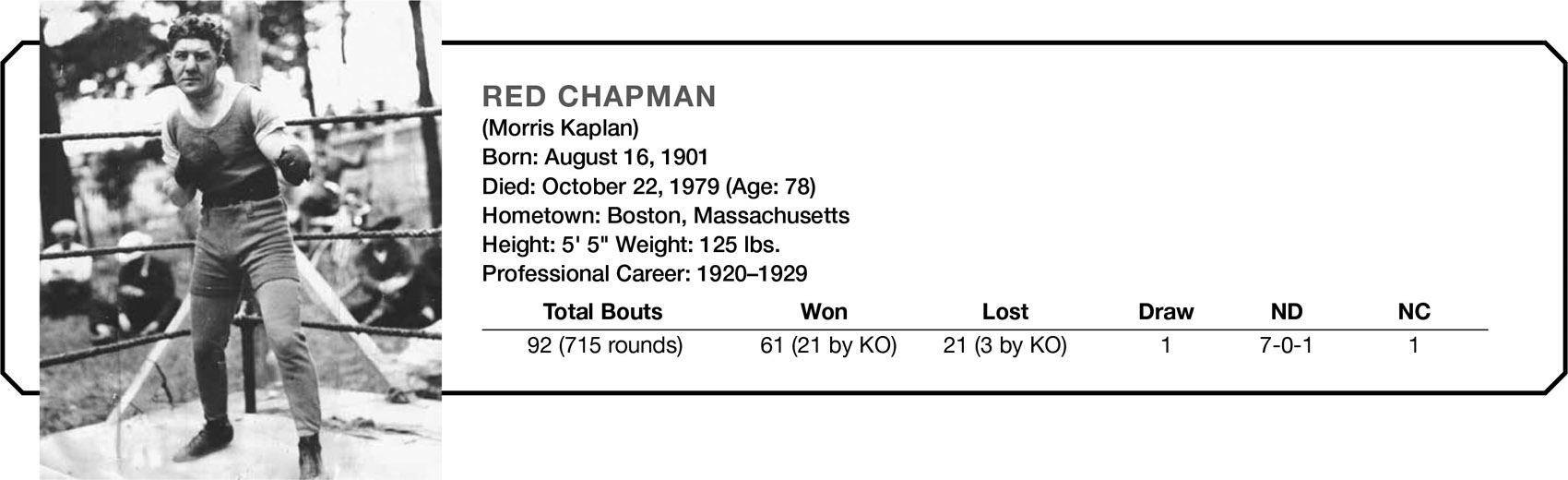

Red Chapman

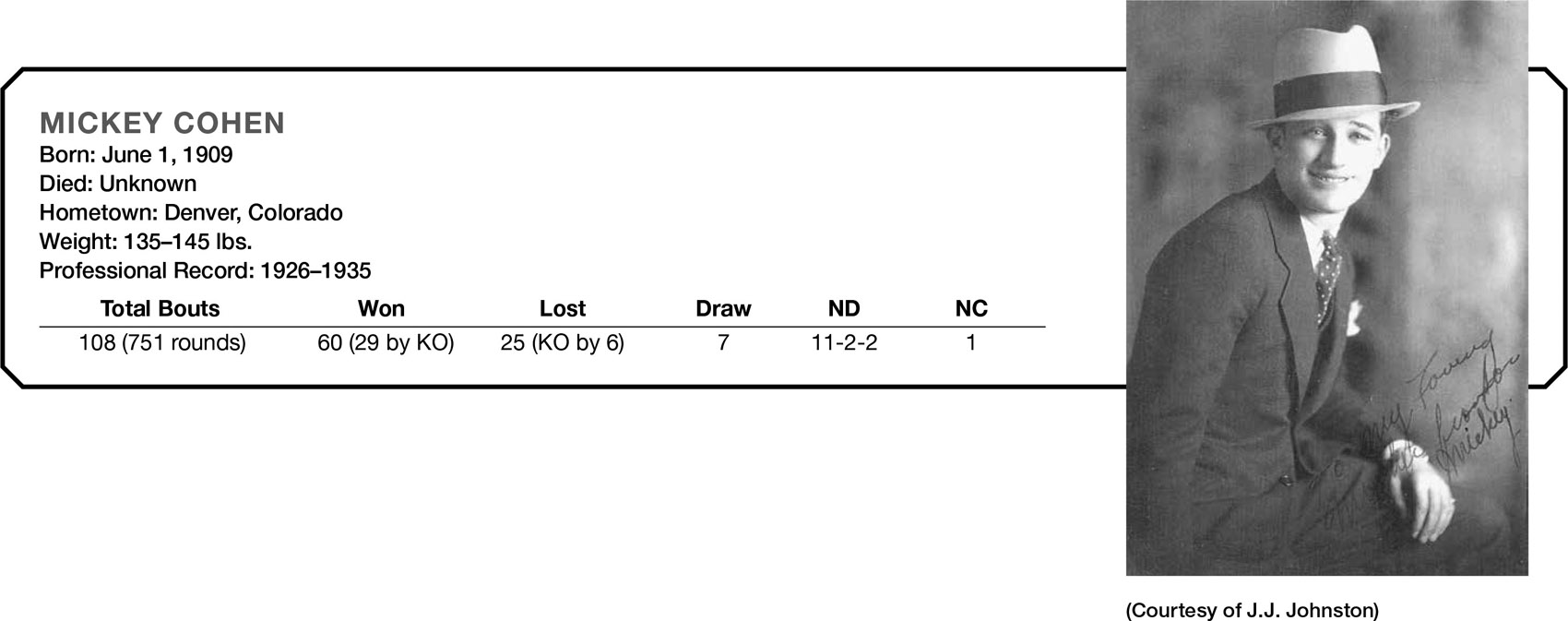

Mickey Cohen

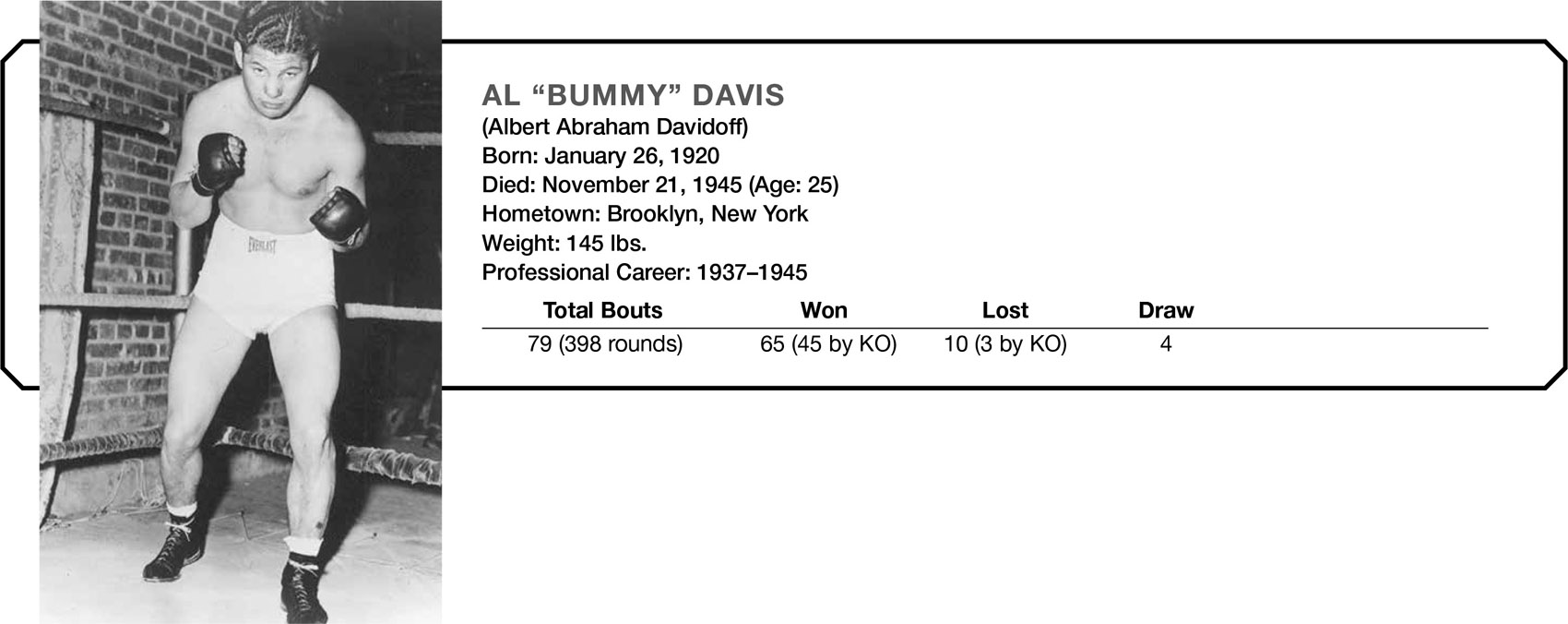

Al “Bummy” Davis

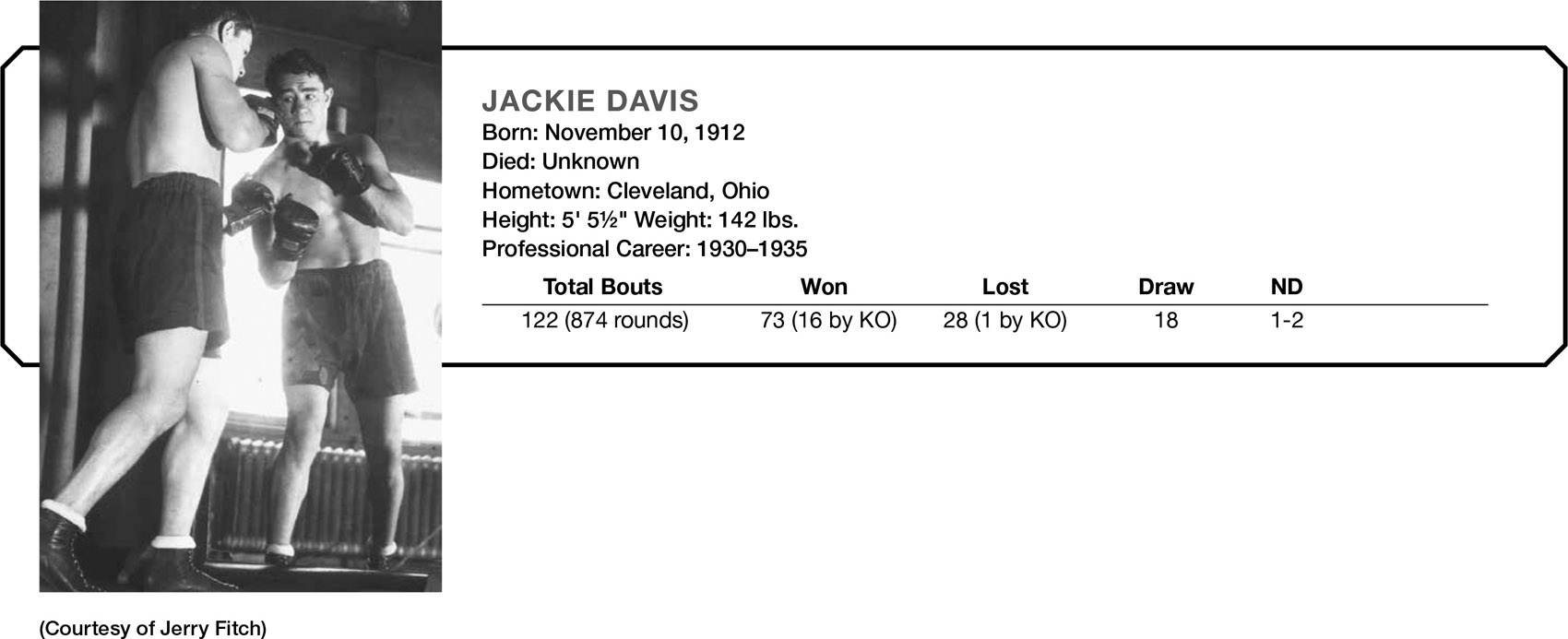

Jackie Davis

Davey Day

Sammy Dorfman

Leone Efrati

Irving Eldridge

Murray Elkins

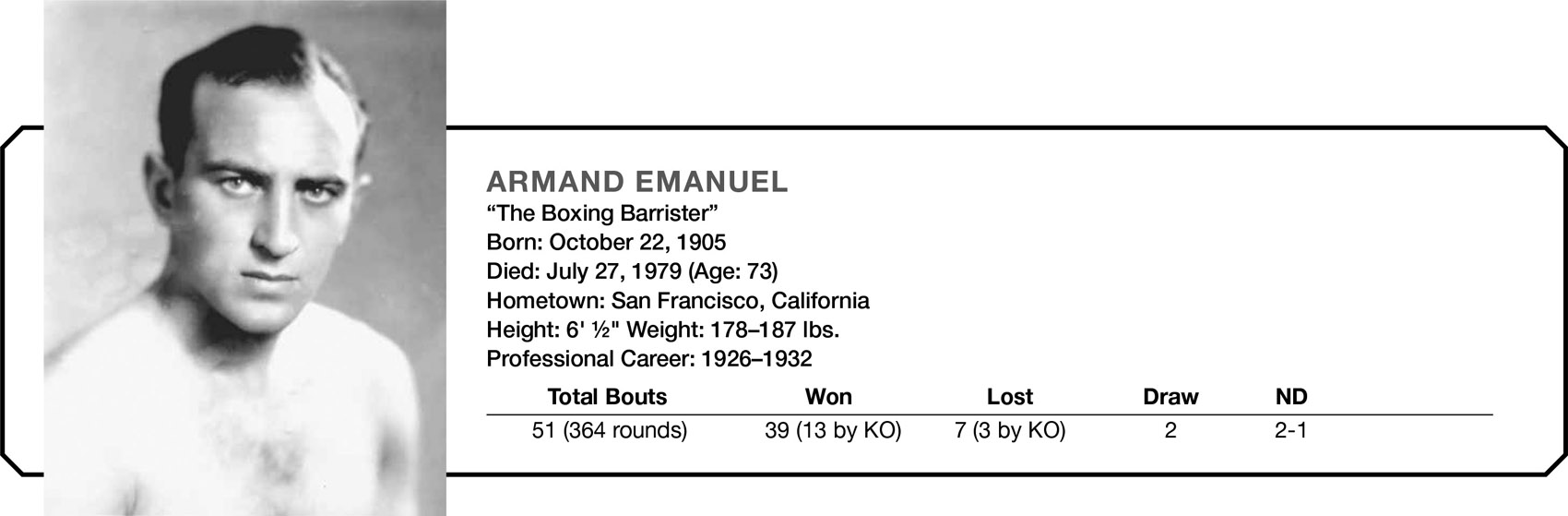

Armand Emanuel

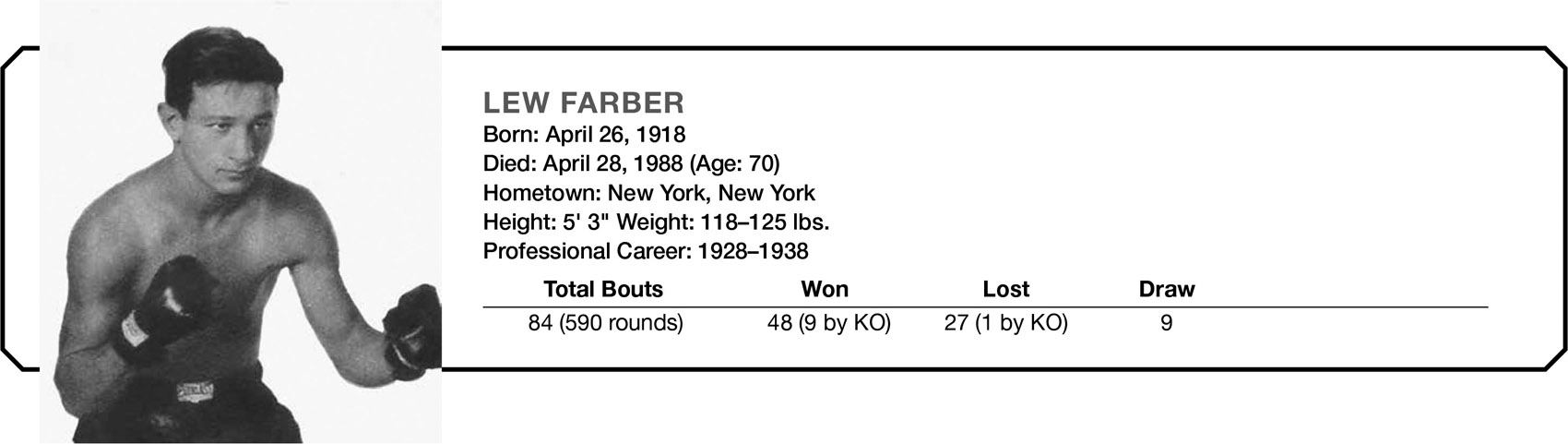

Lew Farber

Abe Feldman

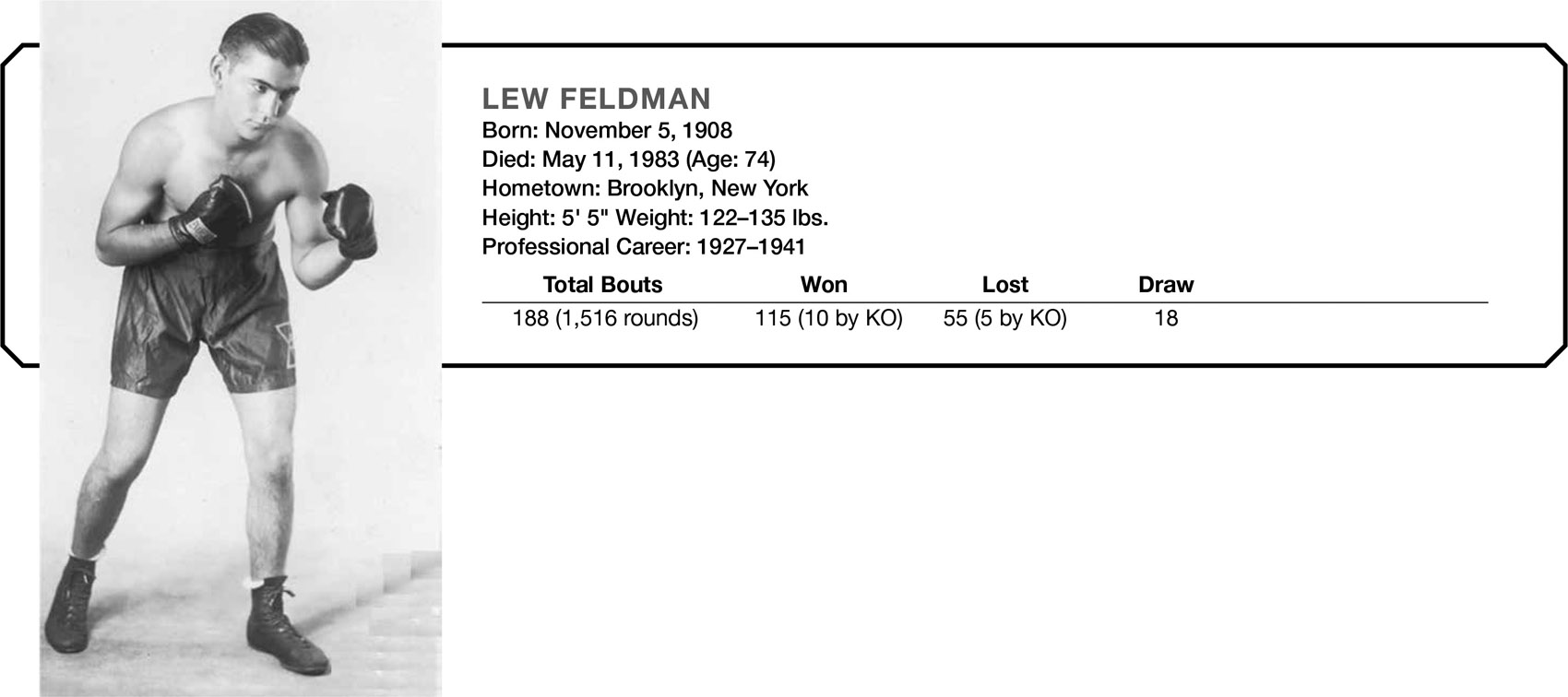

Lew Feldman

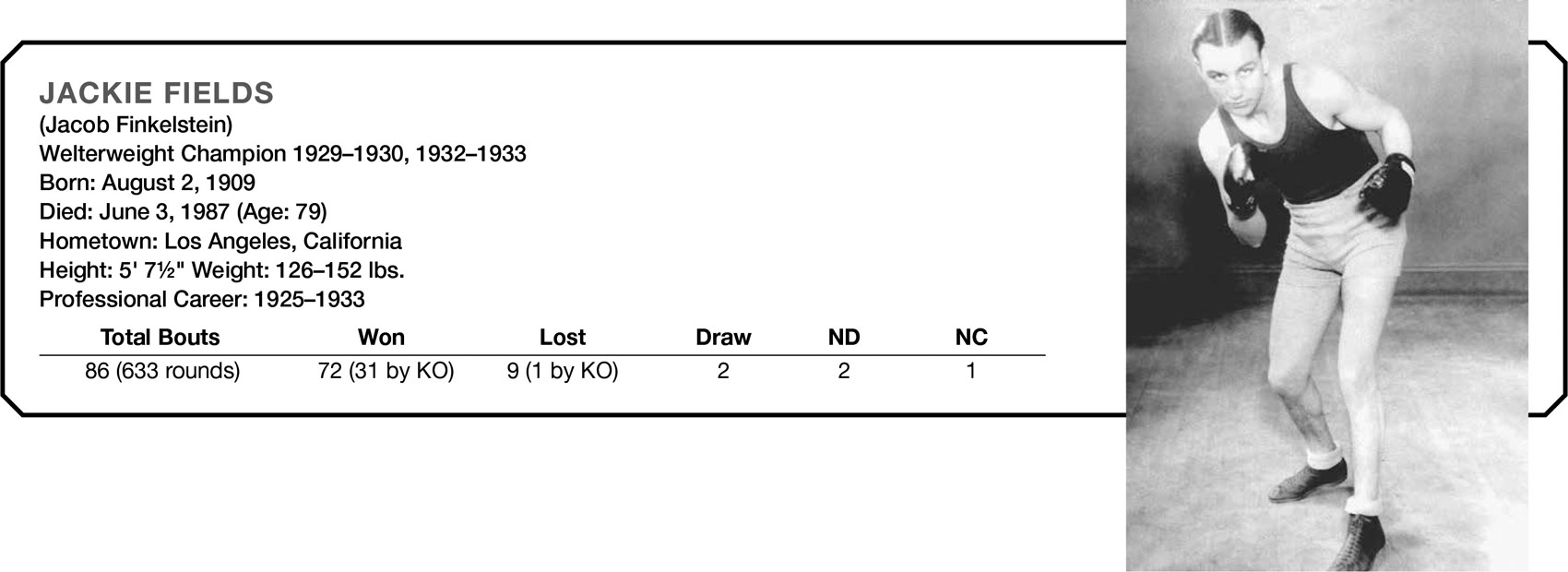

Jackie Fields*

Al Foreman

Kid Francis

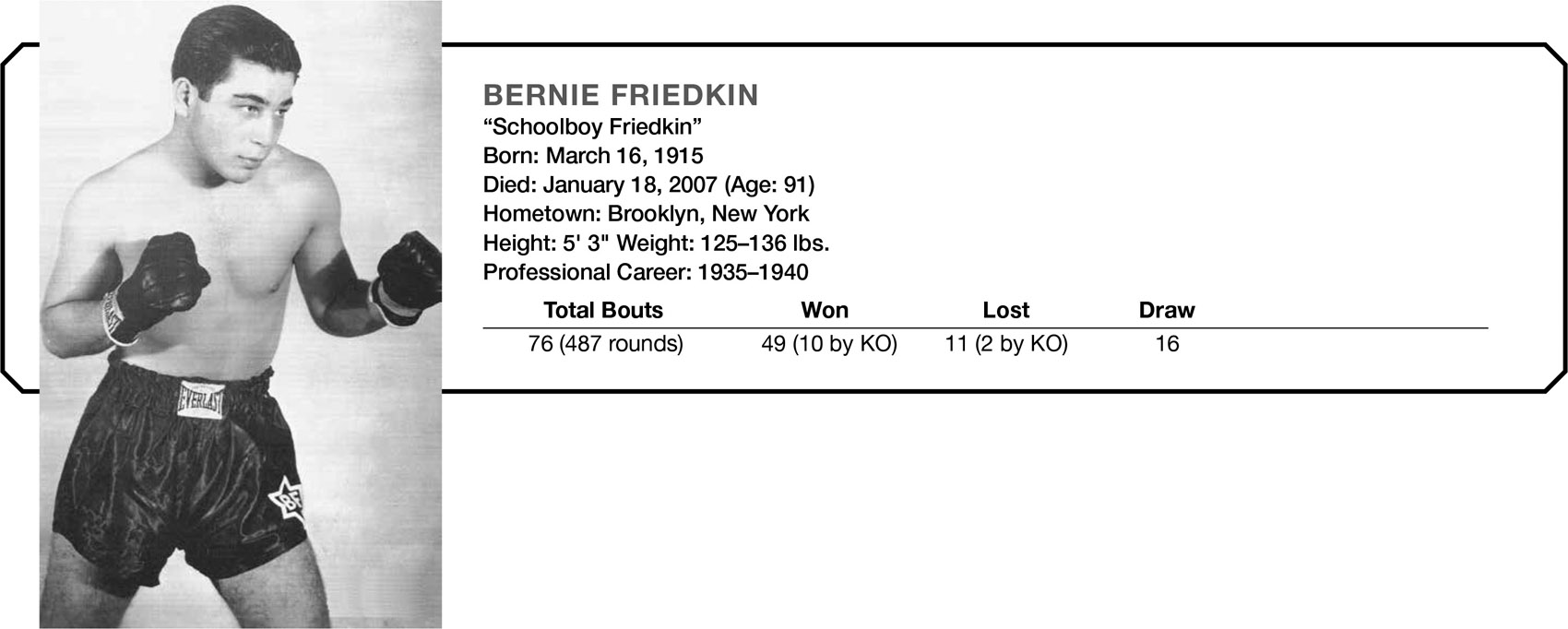

Bernie Friedkin

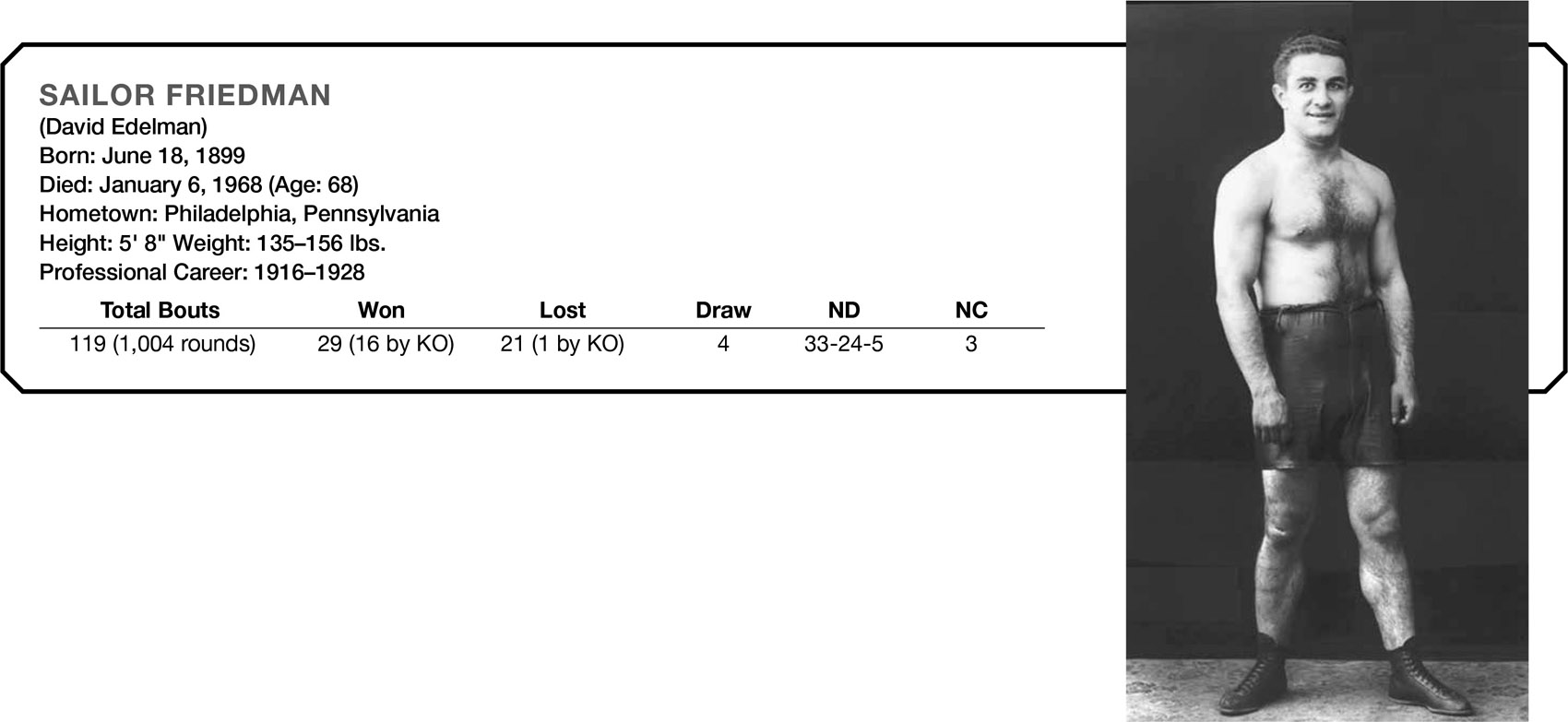

Sailor Friedman

Danny Frush

Joe Glick

Marty Gold

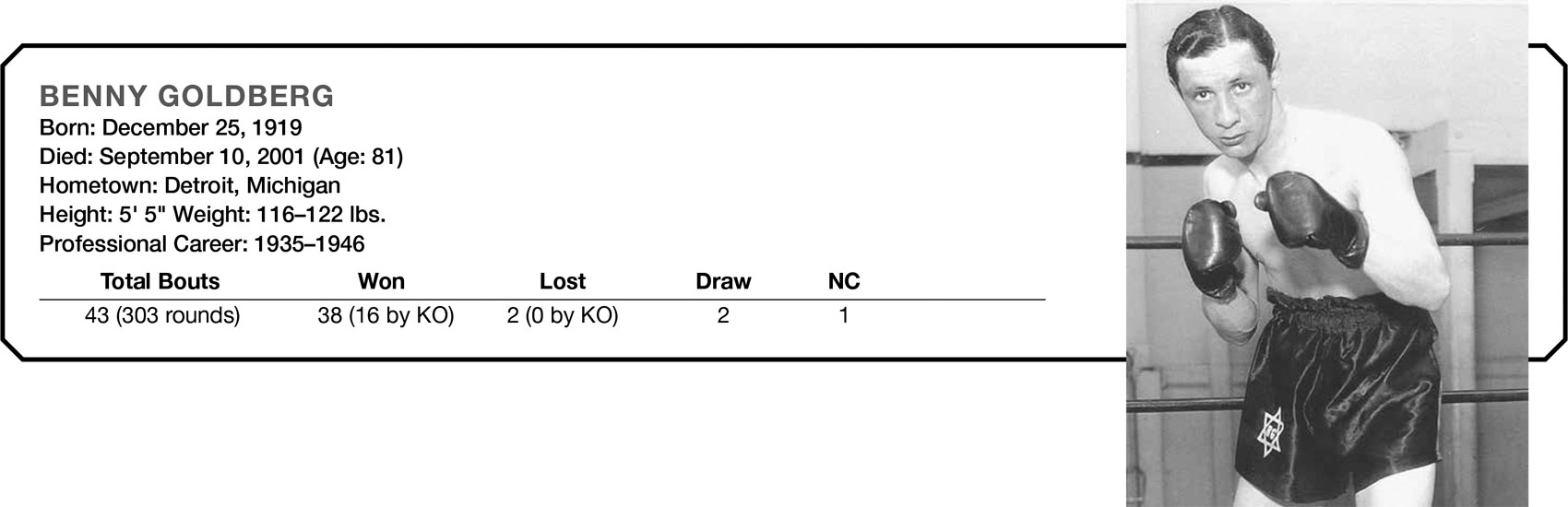

Benny Goldberg

Abe Goldstein*

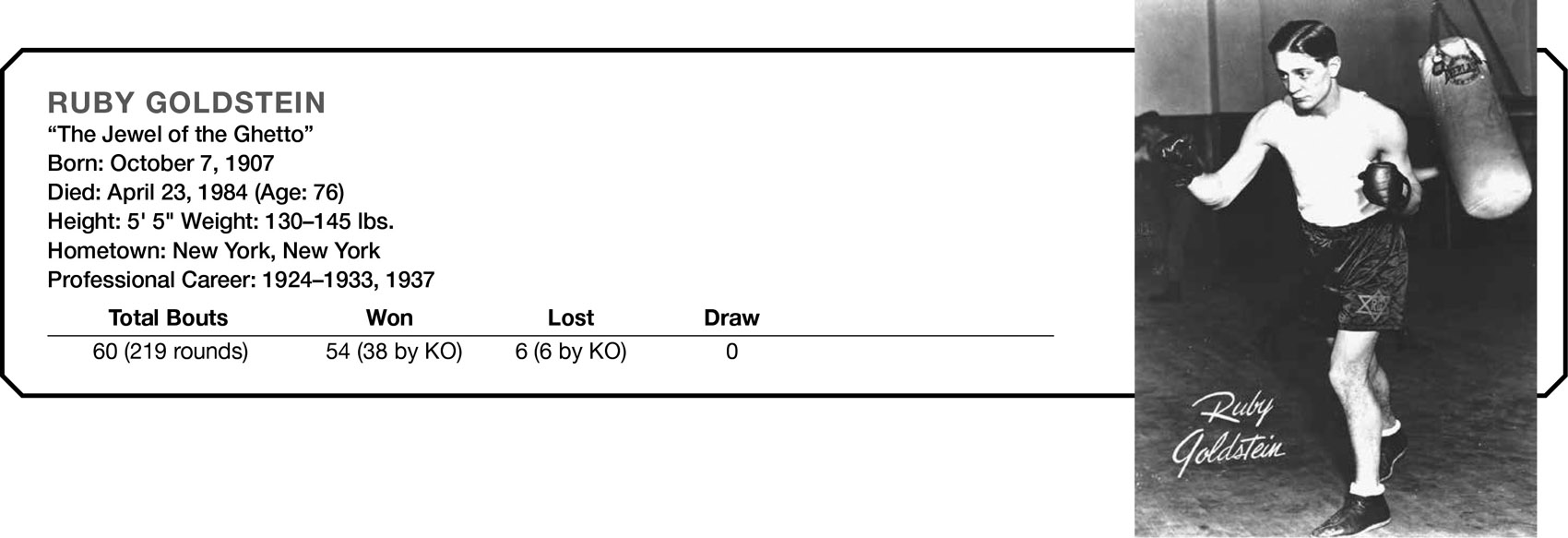

Ruby Goldstein

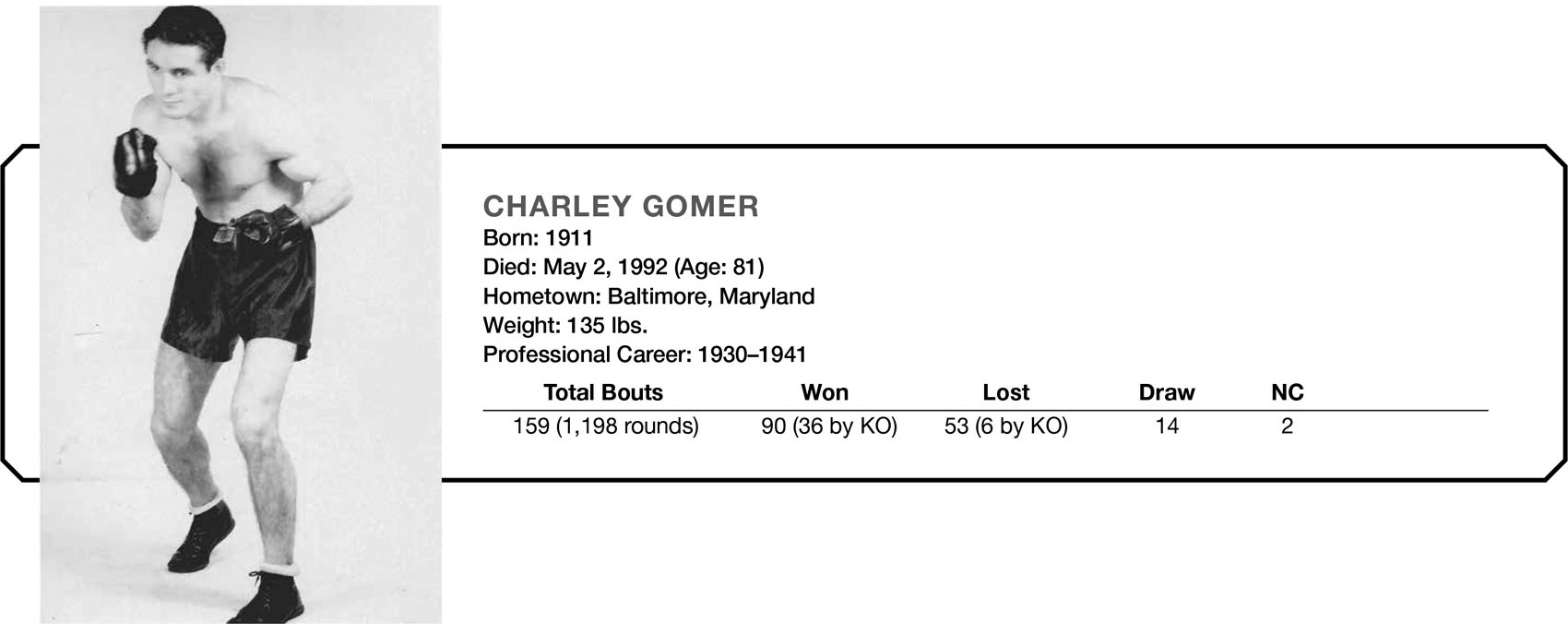

Charley Gomer

Joey Goodman

Al Gordon

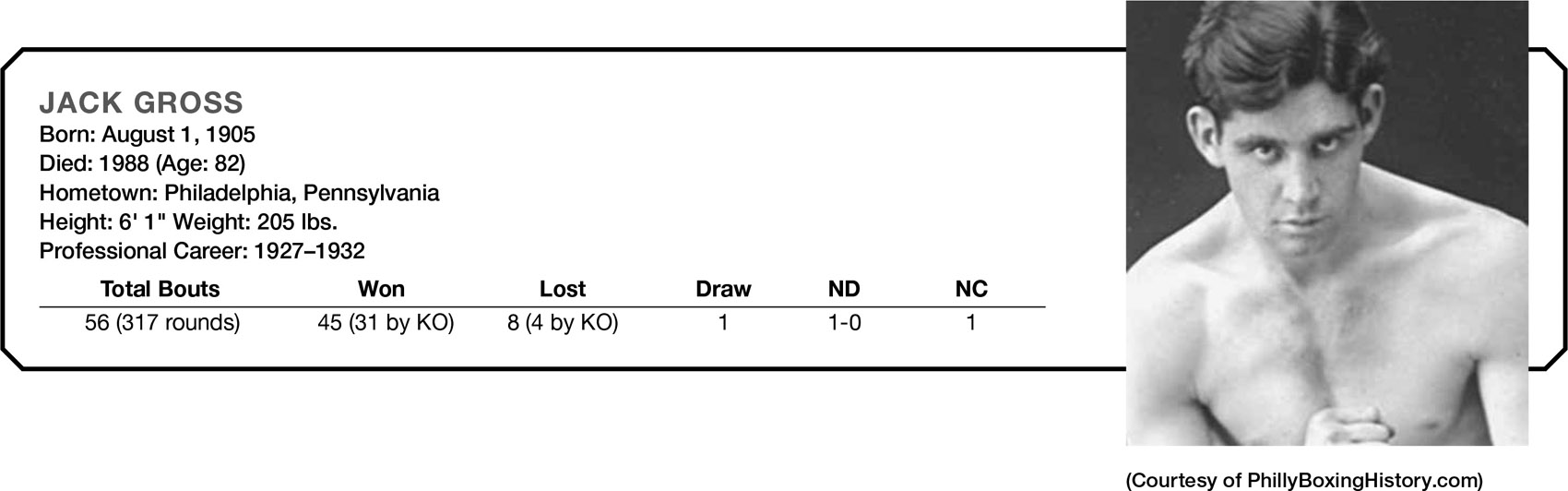

Jack Gross

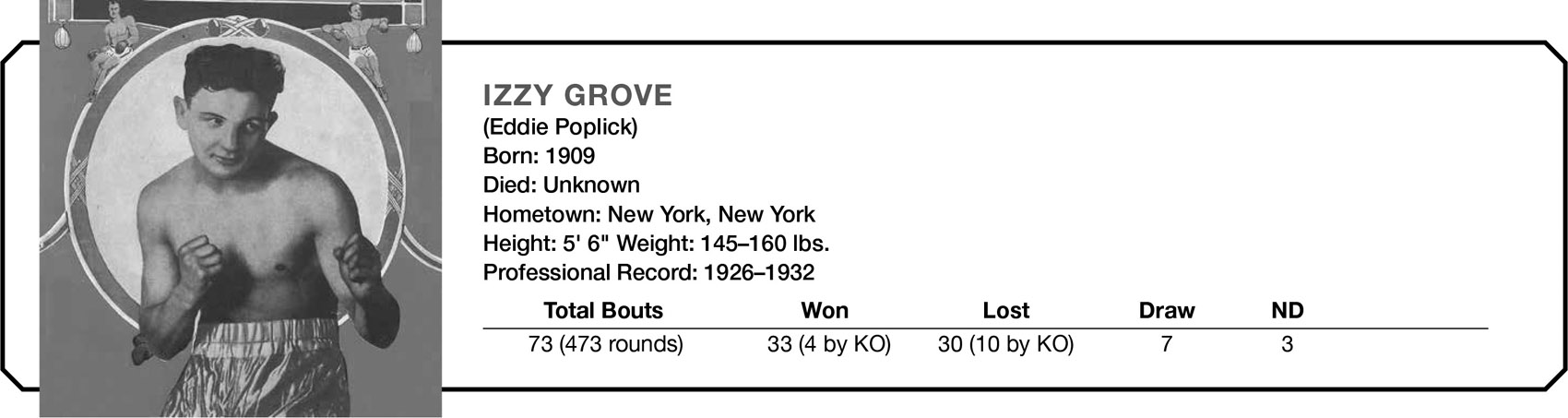

Izzy Grove

Willie Harmon

Gustave Humery

Abie Israel

Ben Jeby*

Andre Jessurun

Louis “Kid” Kaplan*

Mike Kaplan

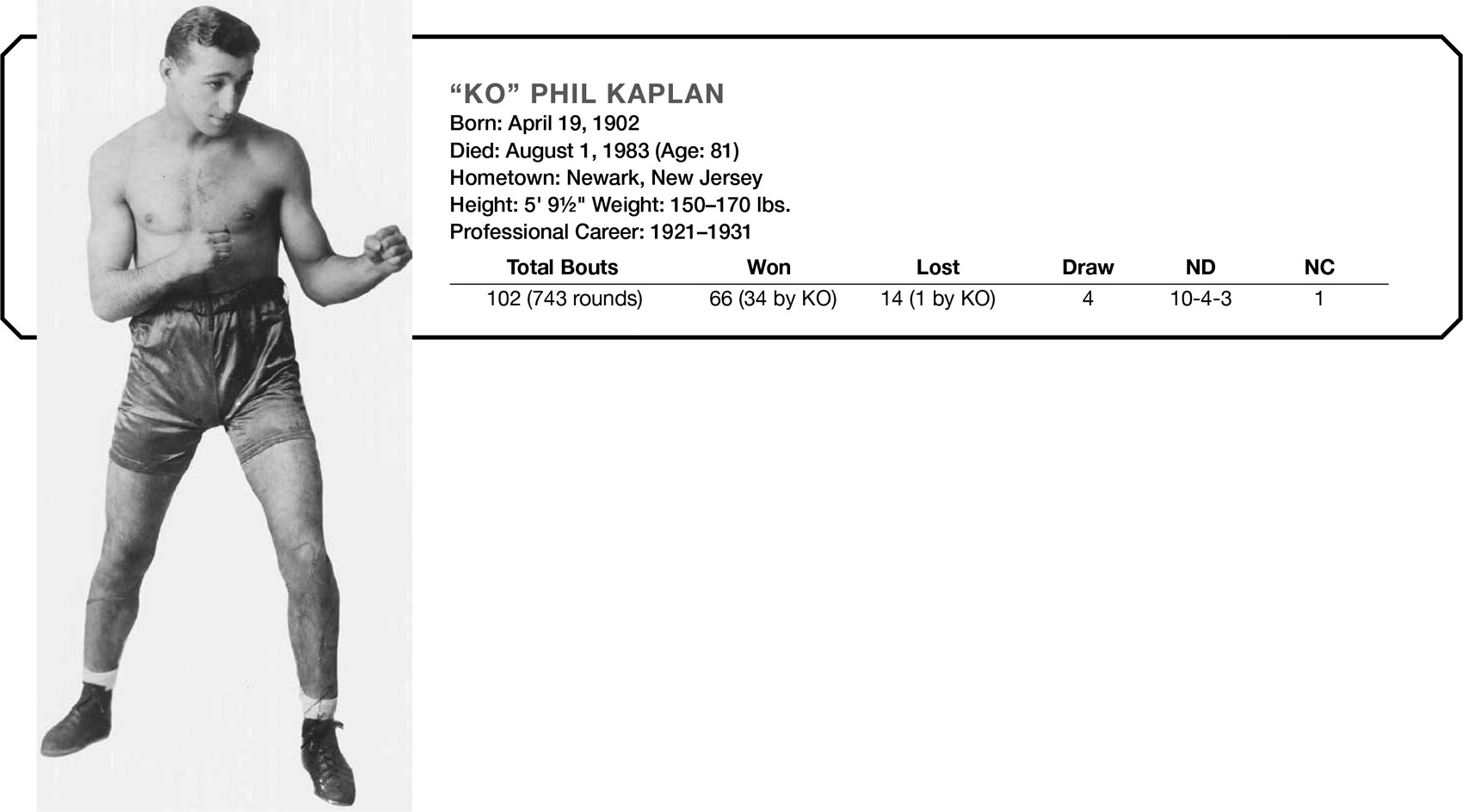

“KO” Phil Kaplan

Herbie Katz

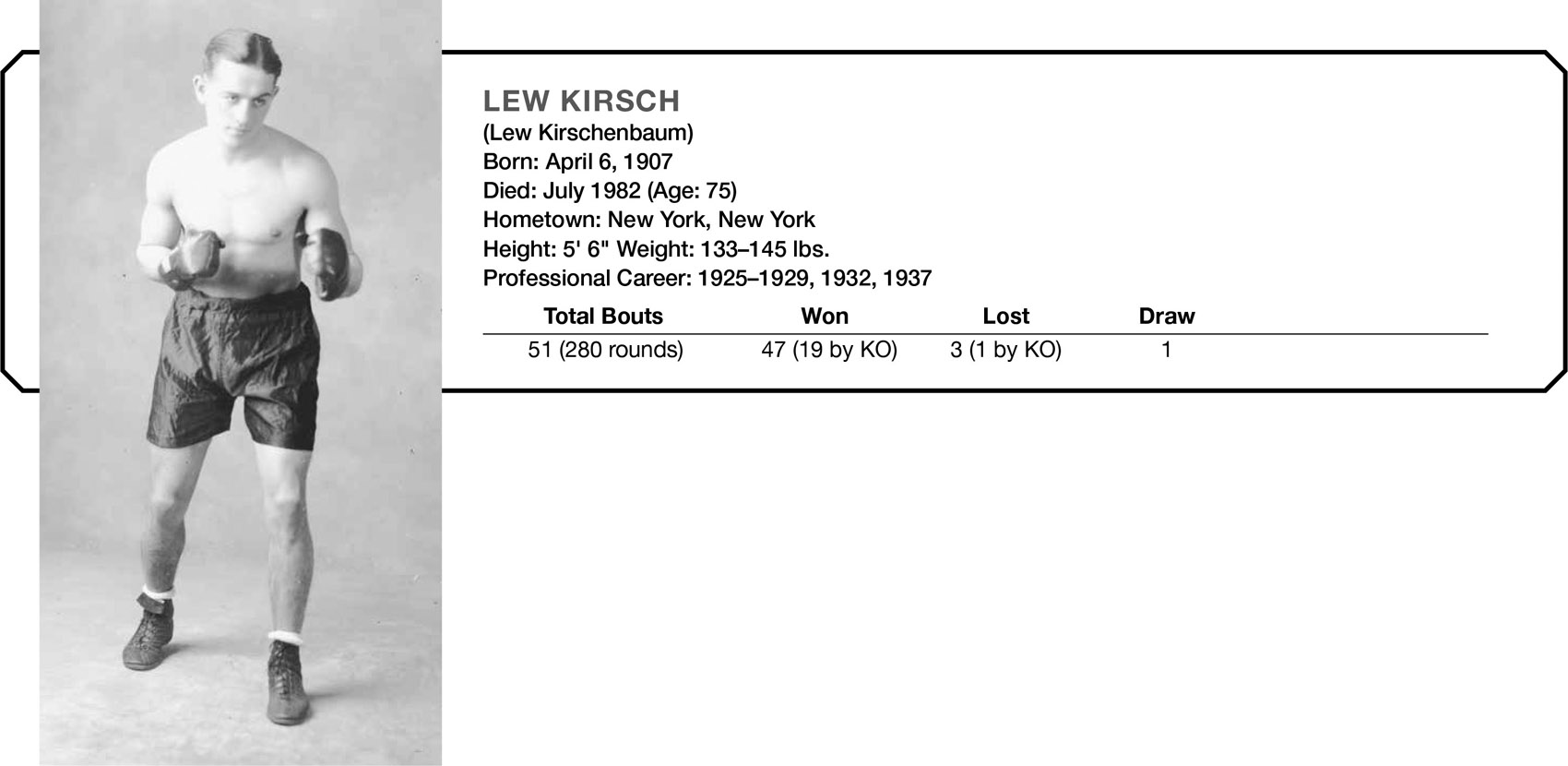

Lew Kirsch

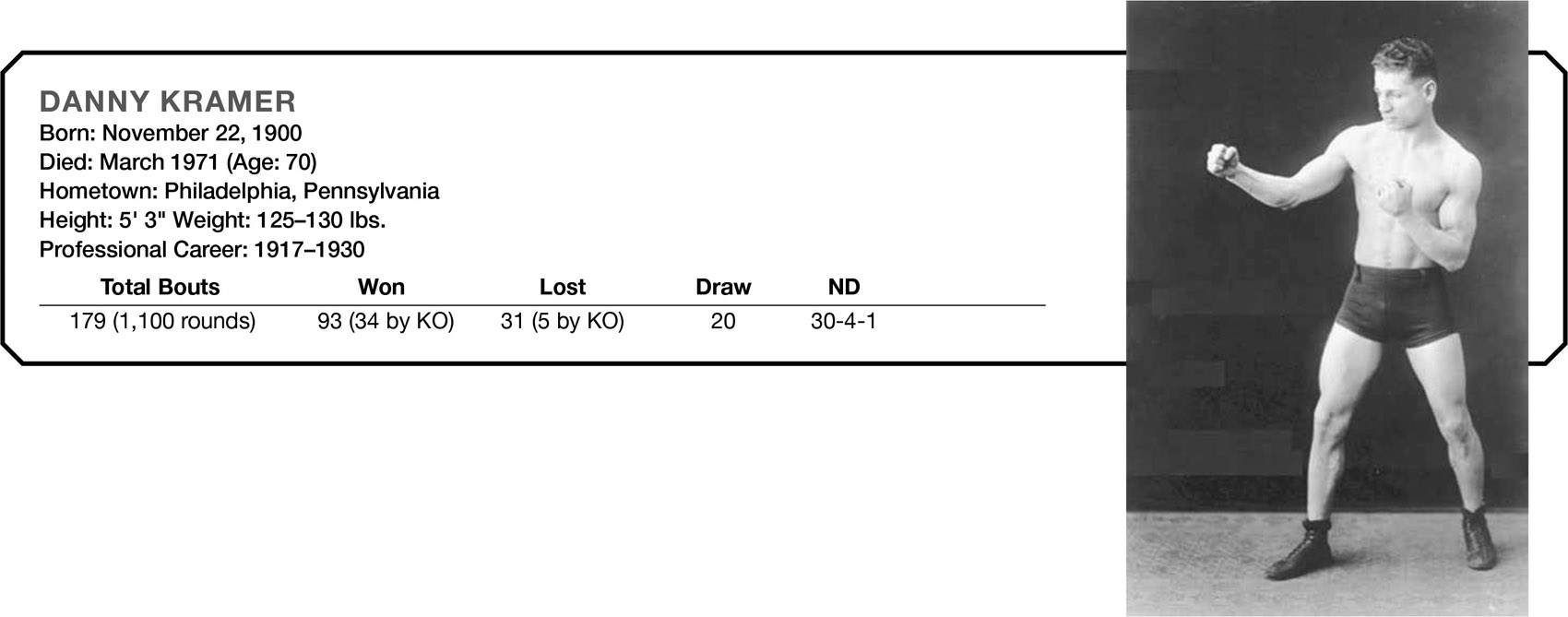

Danny Kramer

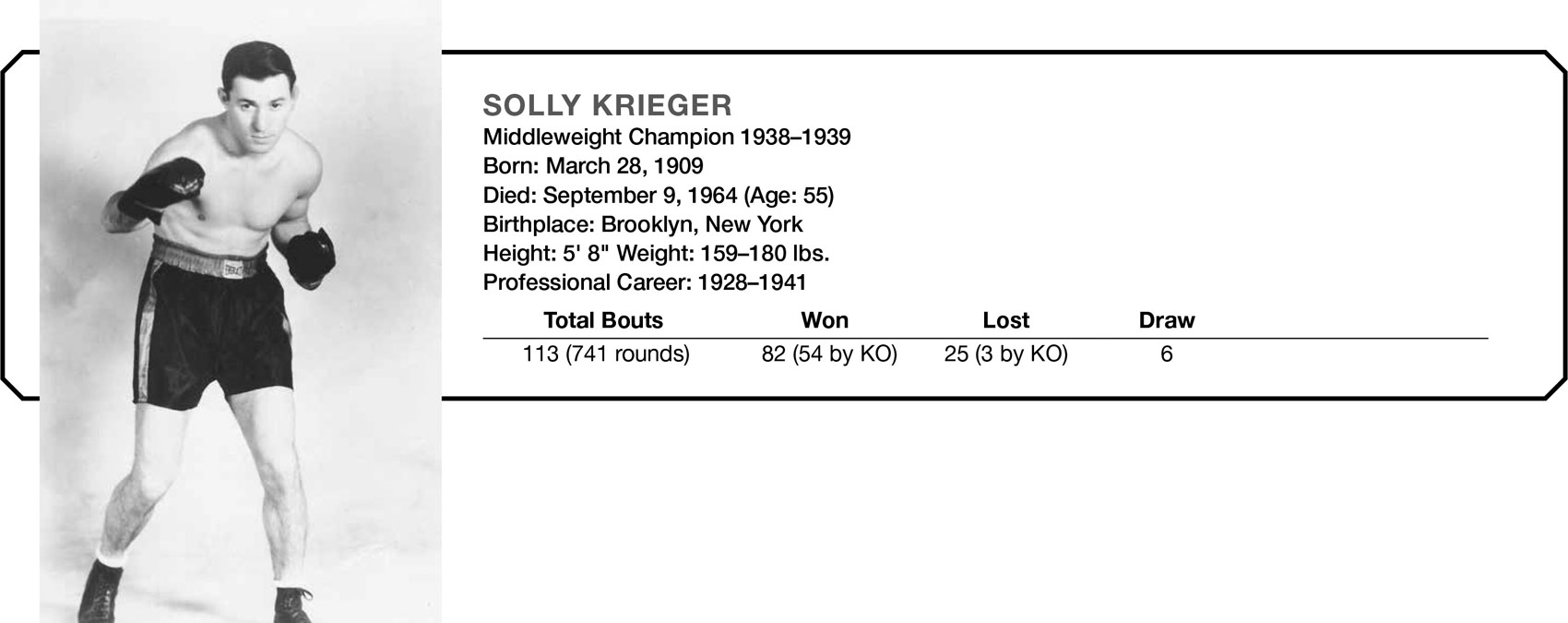

Solly Krieger*

Art Lasky

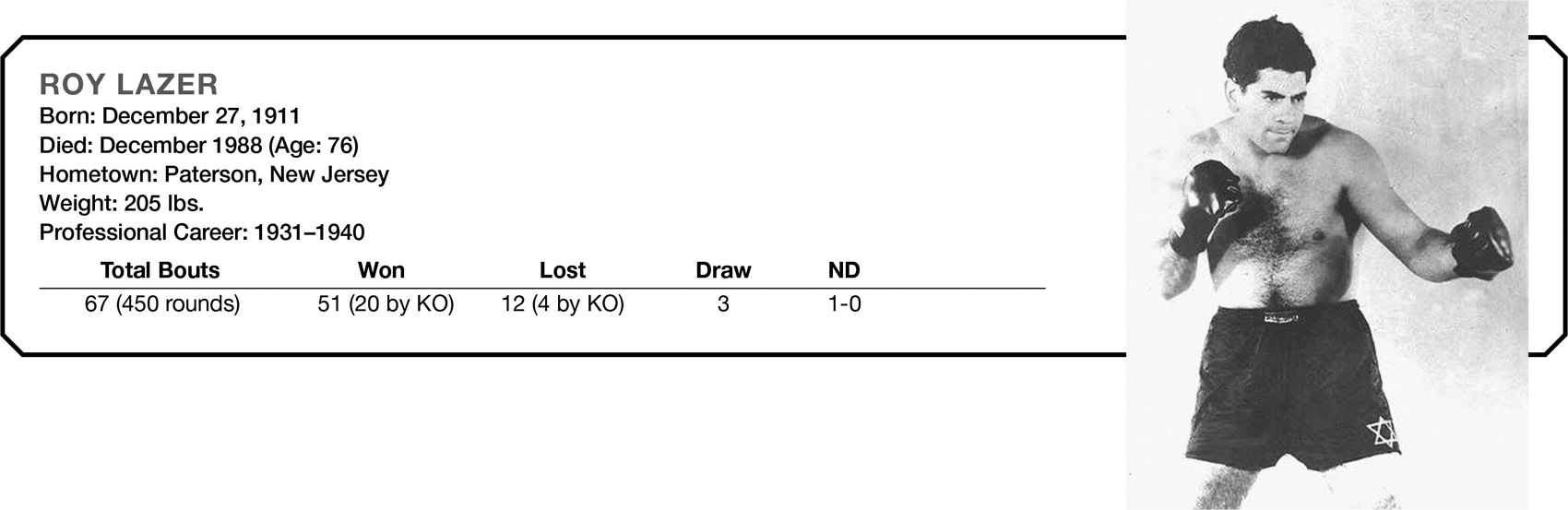

Roy Lazer

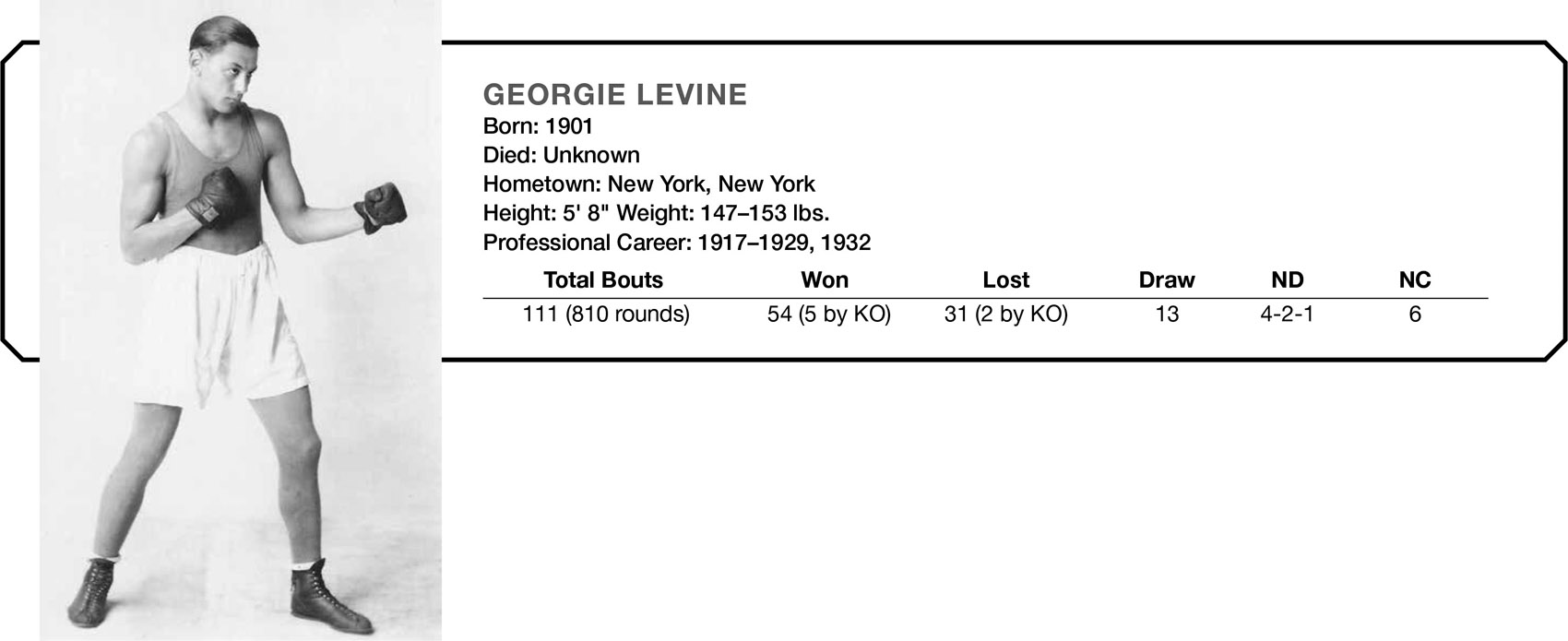

Georgie Levine

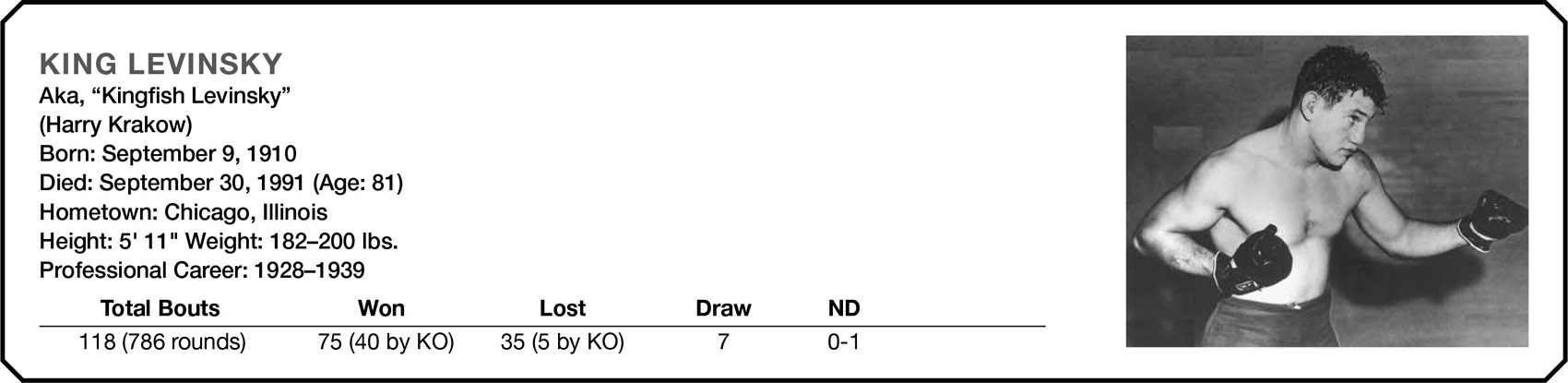

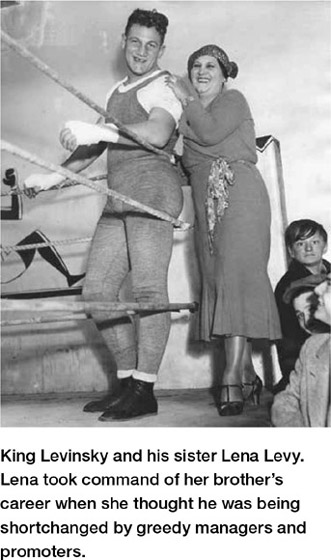

King Levinsky

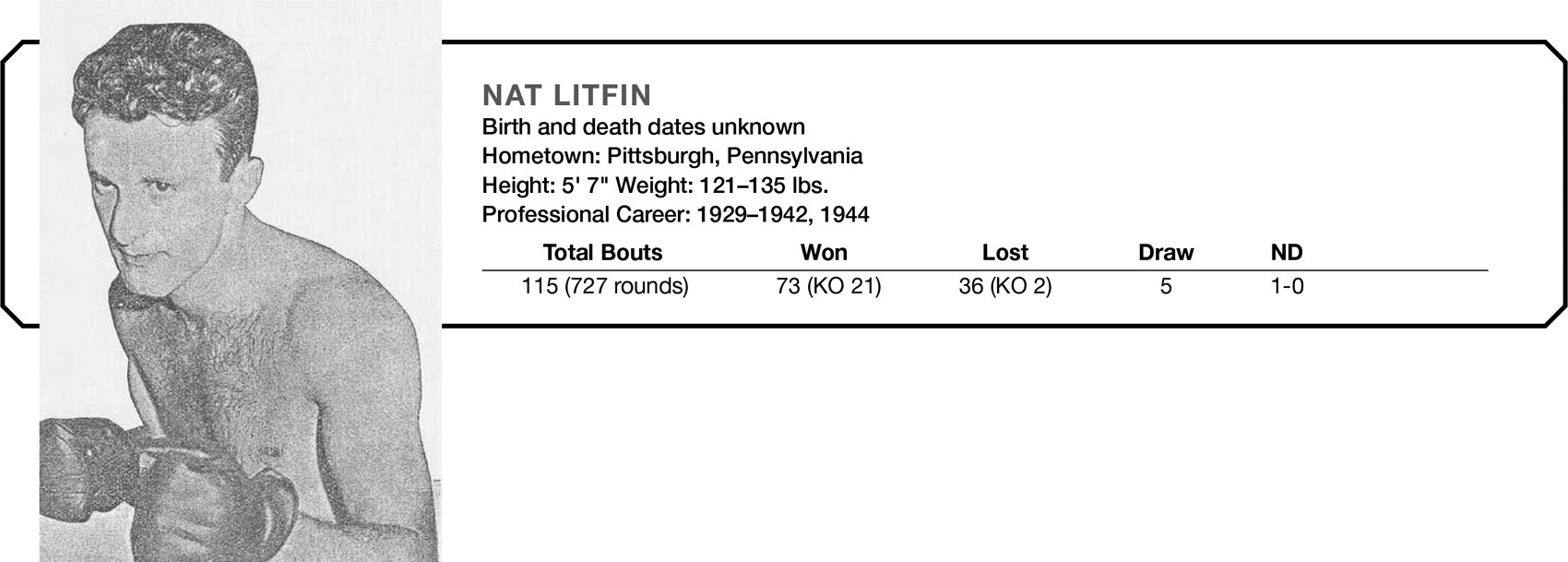

Nat Litfin

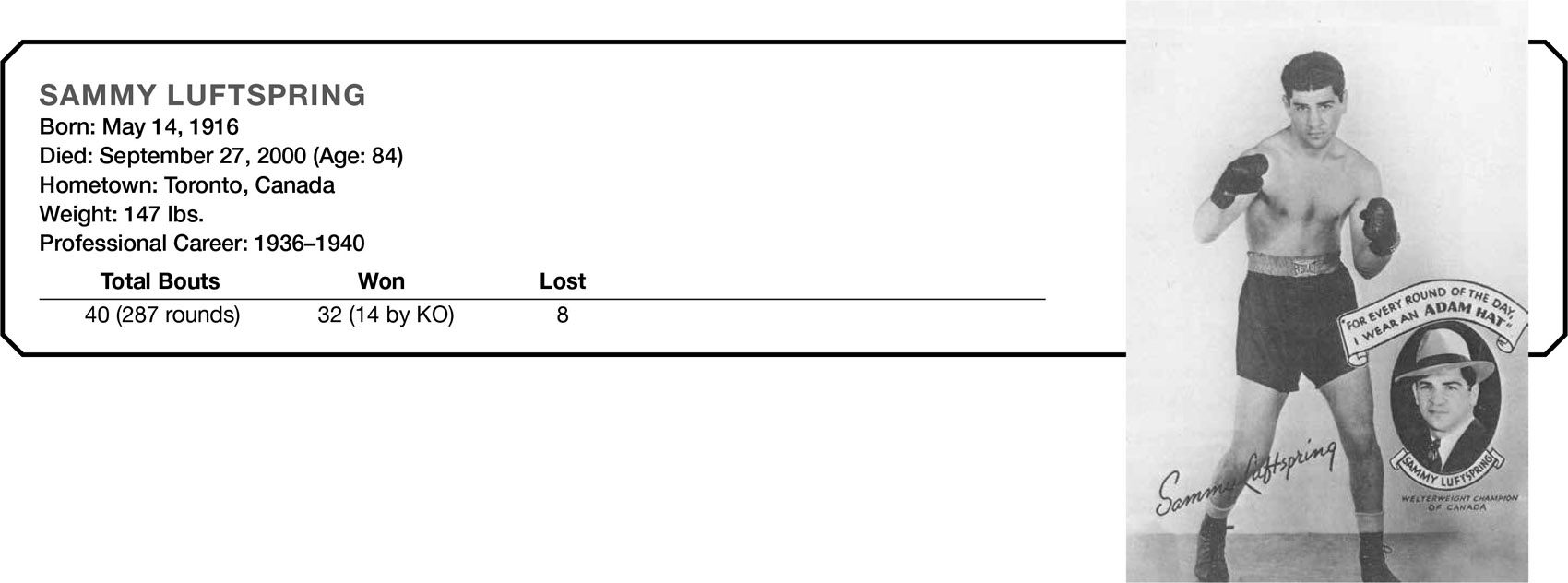

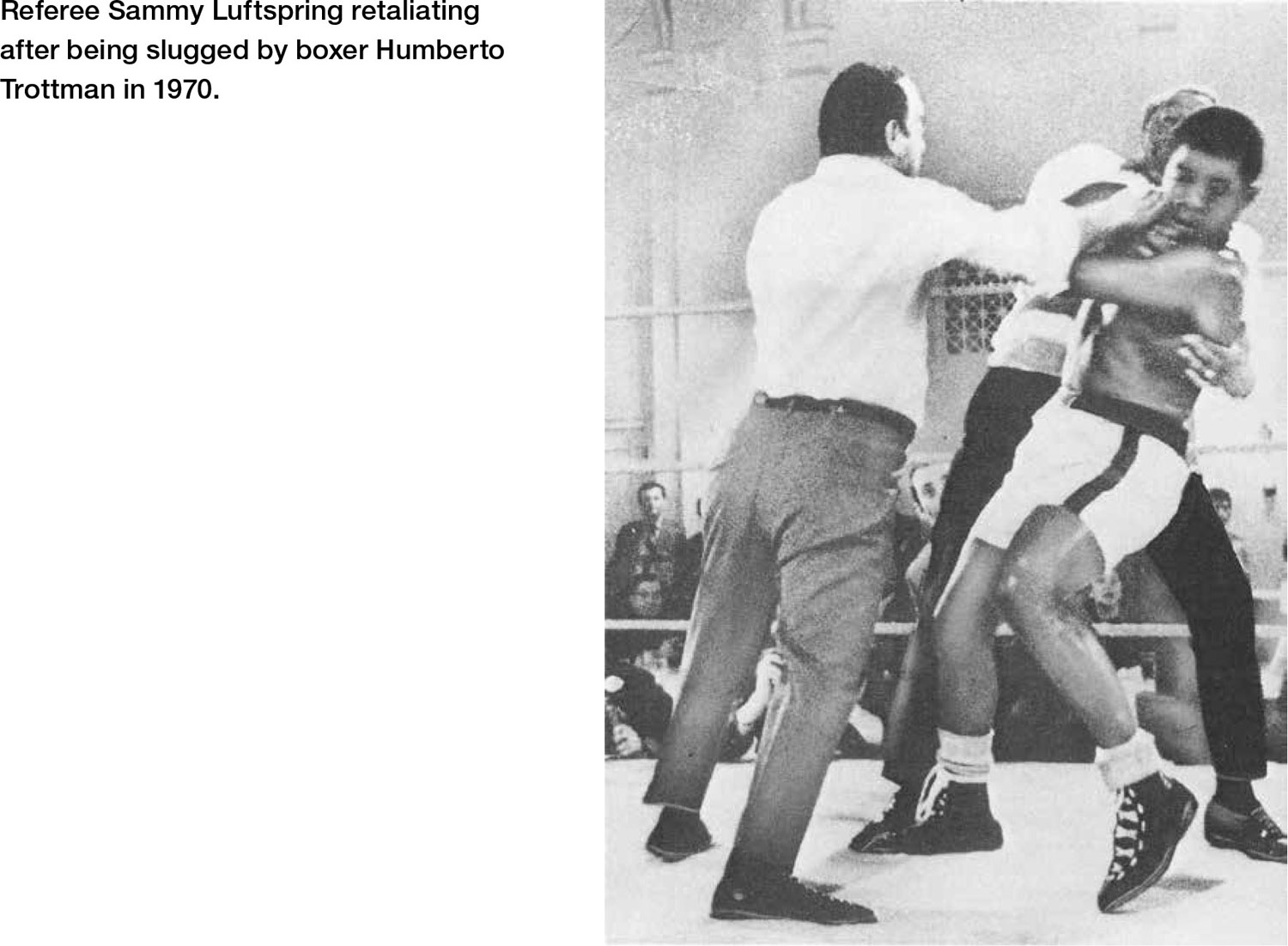

Sammy Luftspring

Georgie Marks

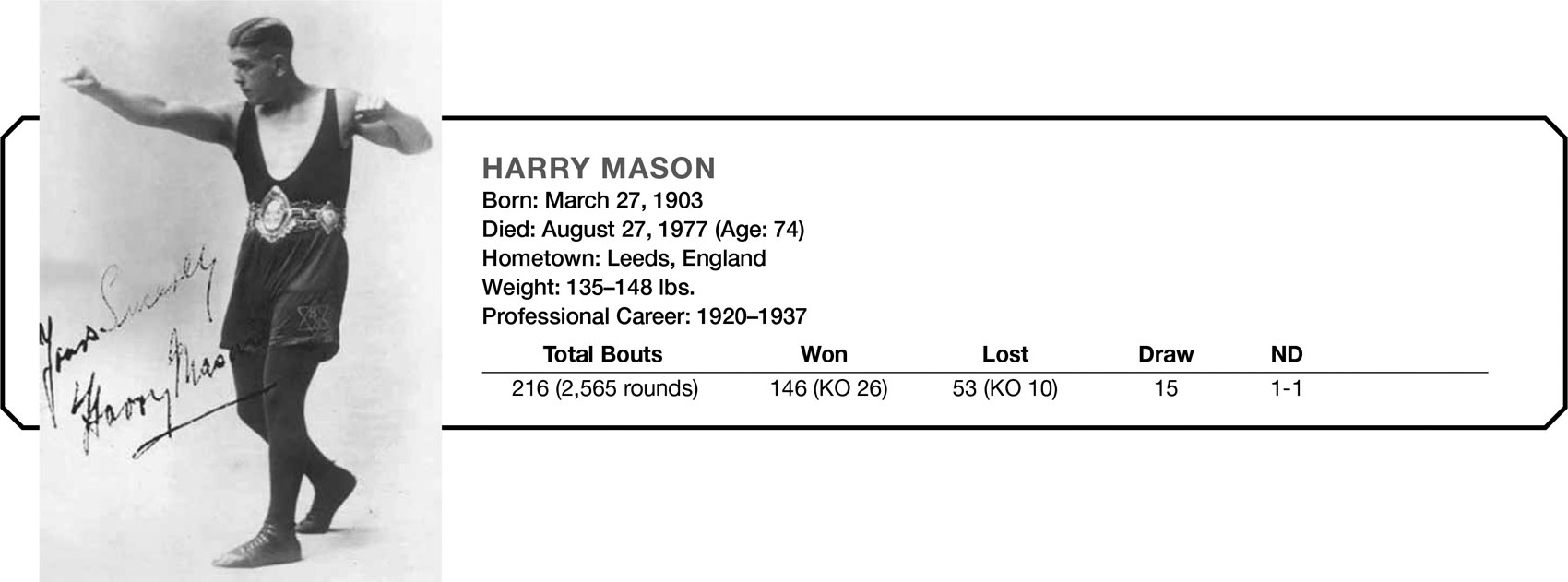

Harry Mason

Joey Medill

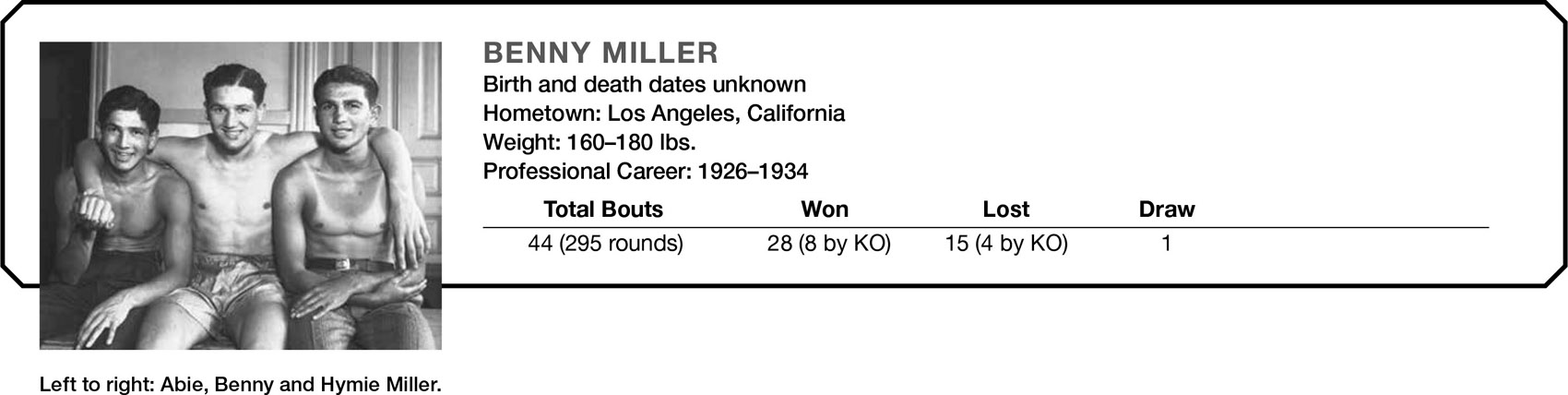

Benny Miller

Ray Miller

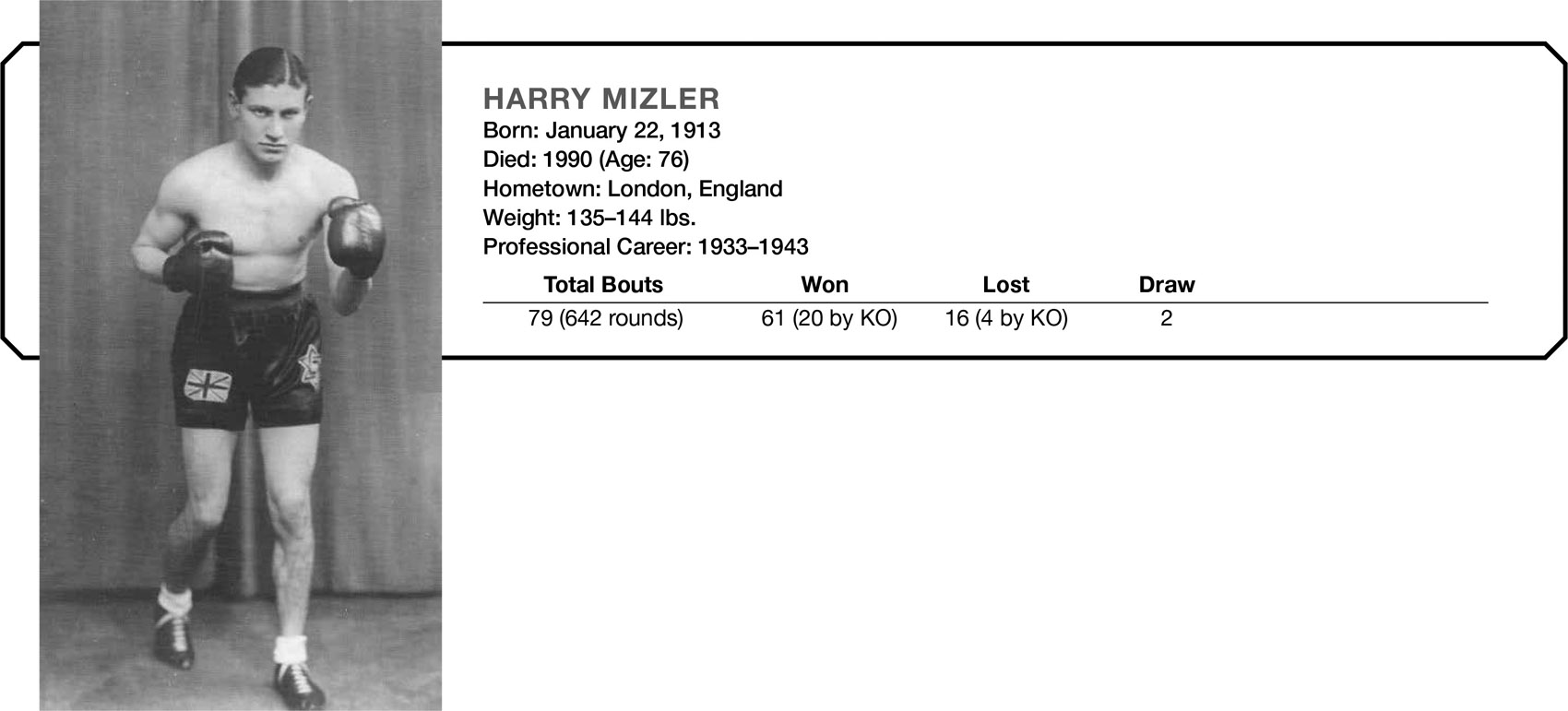

Harry Mizler

Young Montreal

Yale Okun

Bob Olin*

Victor “Young” Perez*

Bill Poland

Jack Portney

Augie Ratner

Al Reid

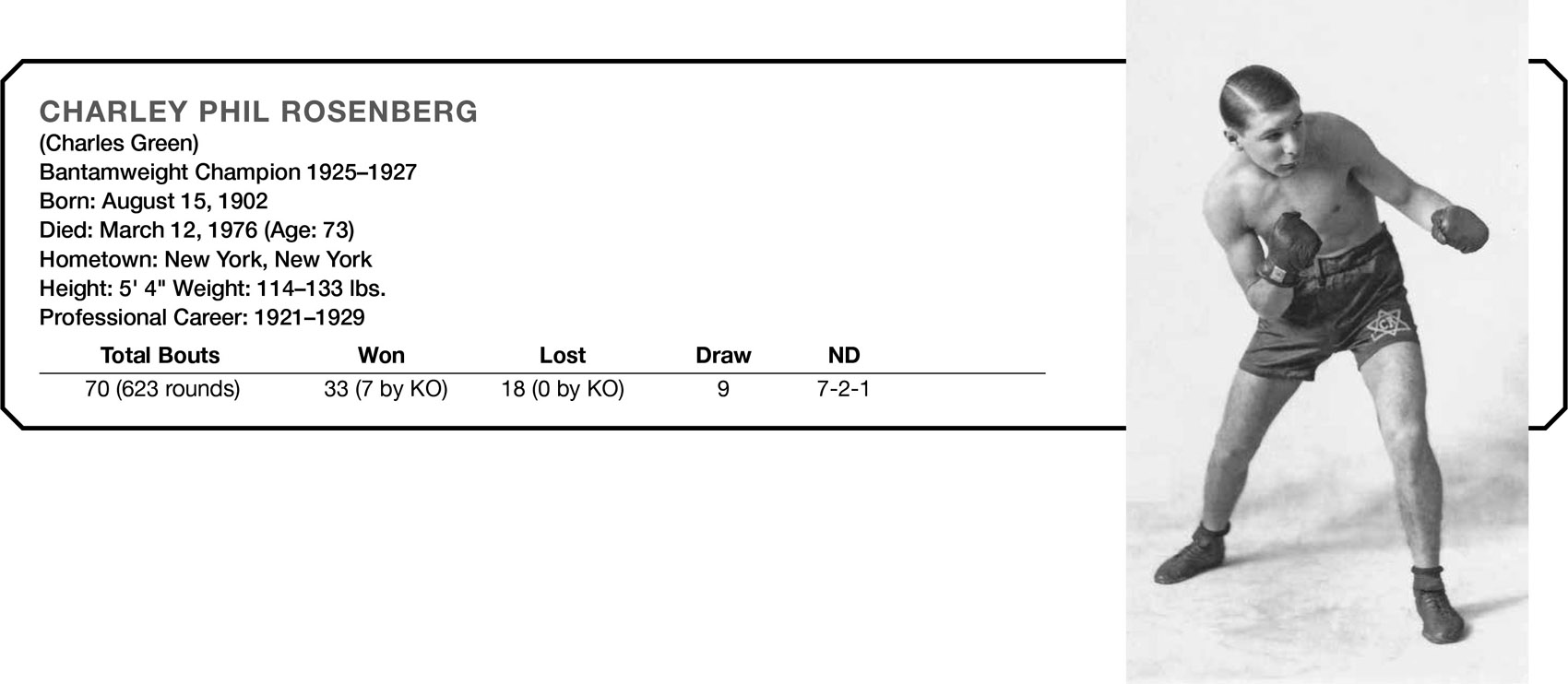

Charley Phil

Rosenberg*

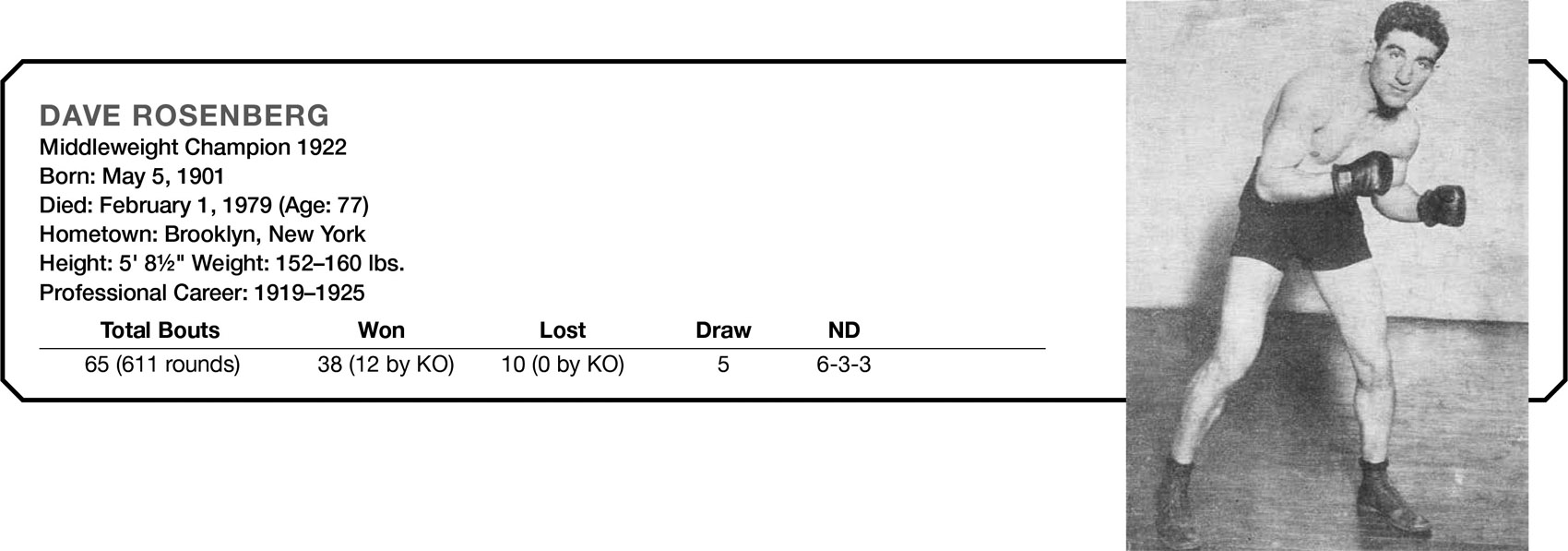

Dave Rosenberg*

“Slapsie Maxie”

Rosenbloom*

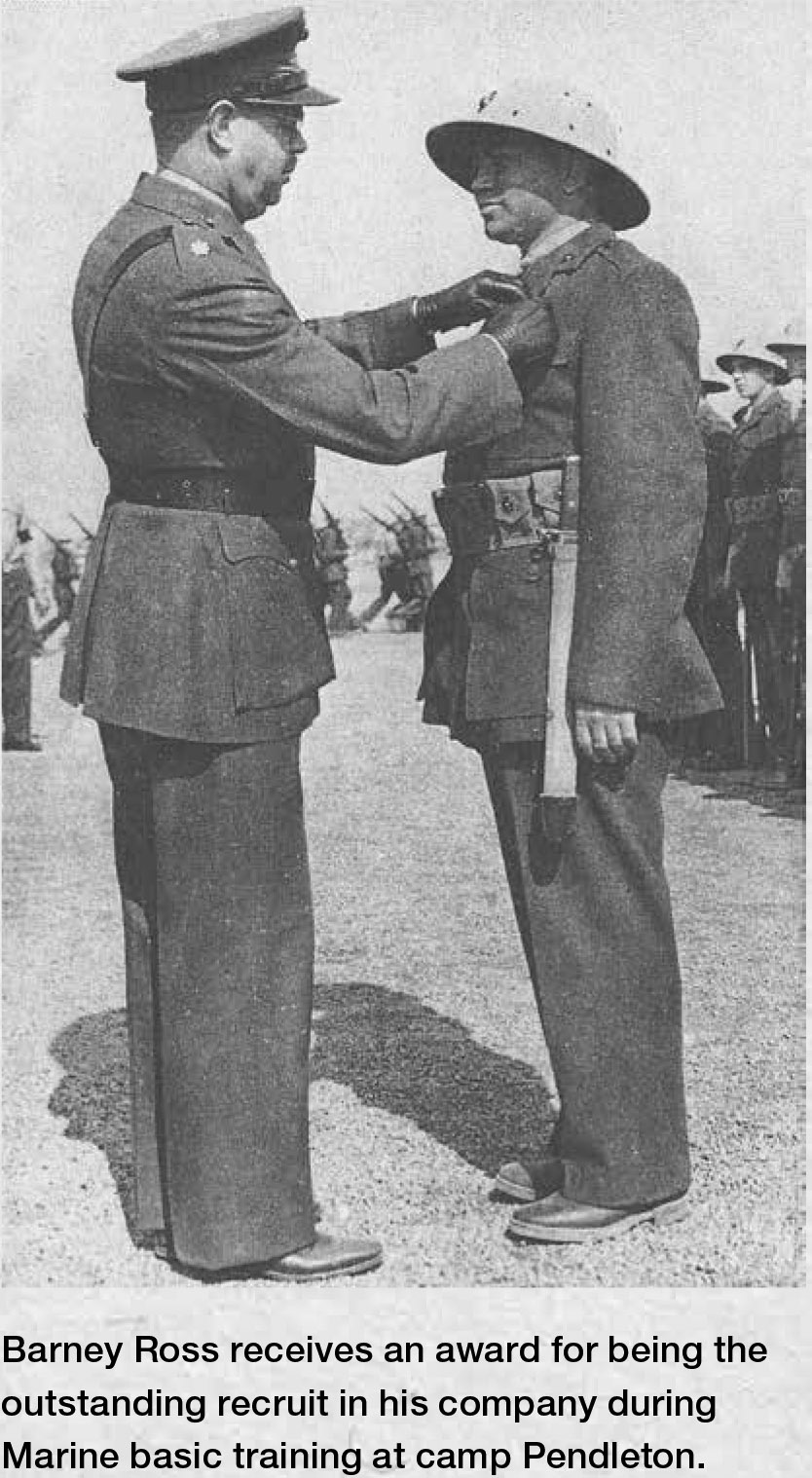

Barney Ross*

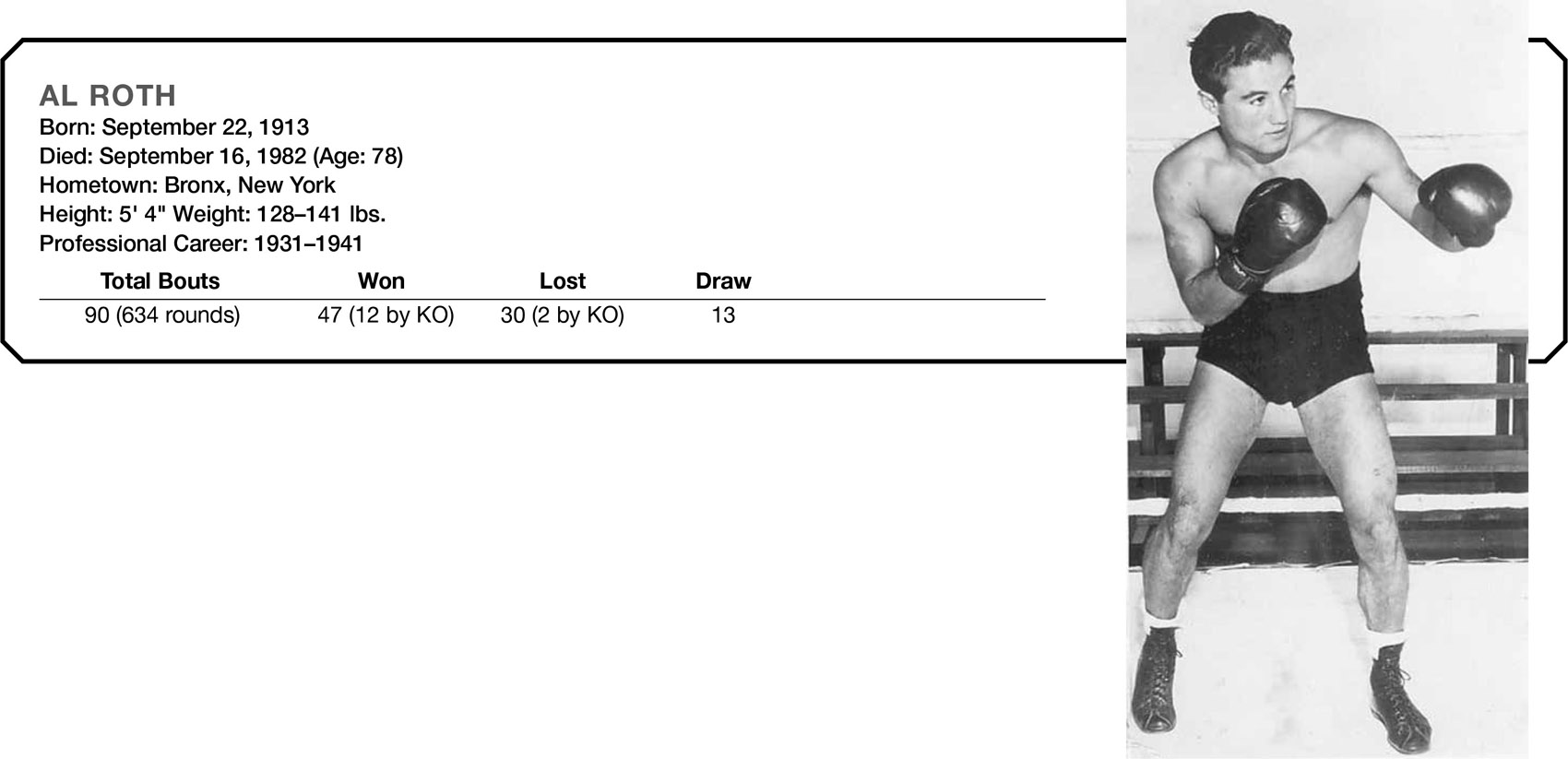

Al Roth

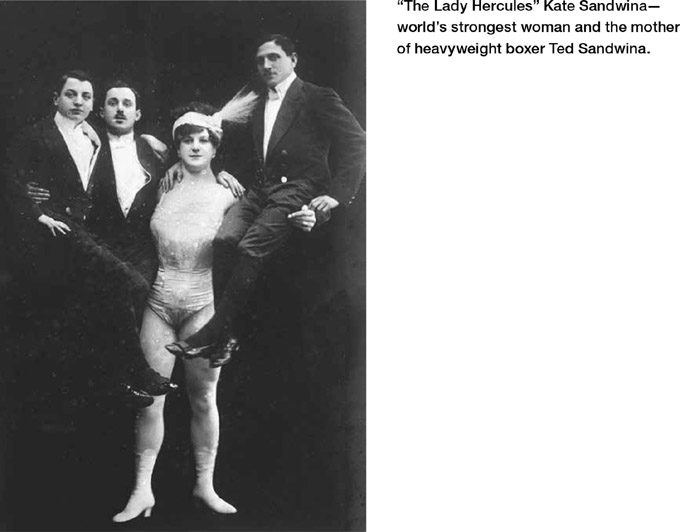

Ted Sandwina

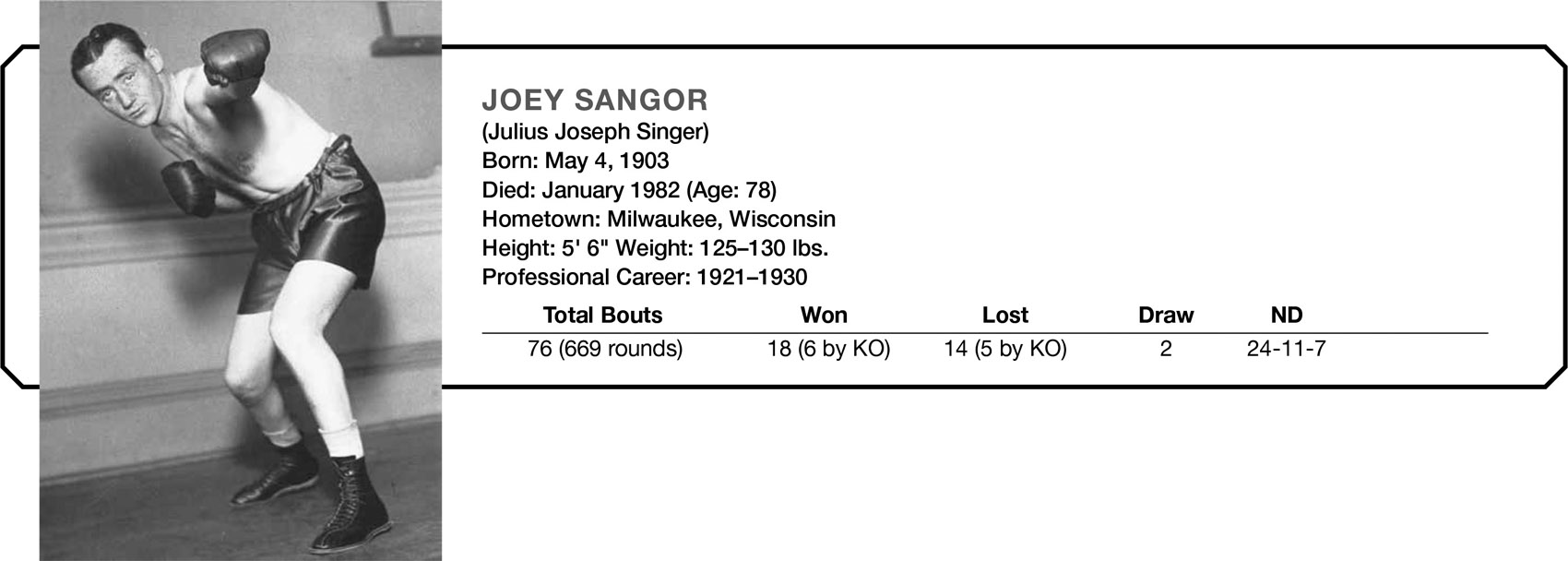

Joey Sangor

Morrie Schlaifer

Benny Schwartz

Corporal Izzy

Schwartz*

Erich Seelig

Solly Seeman

Benny Sharkey

Pinky Silverberg*

Pal Silvers

Abe Simon

Al Singer*

Lew Tendler

Sid Terris

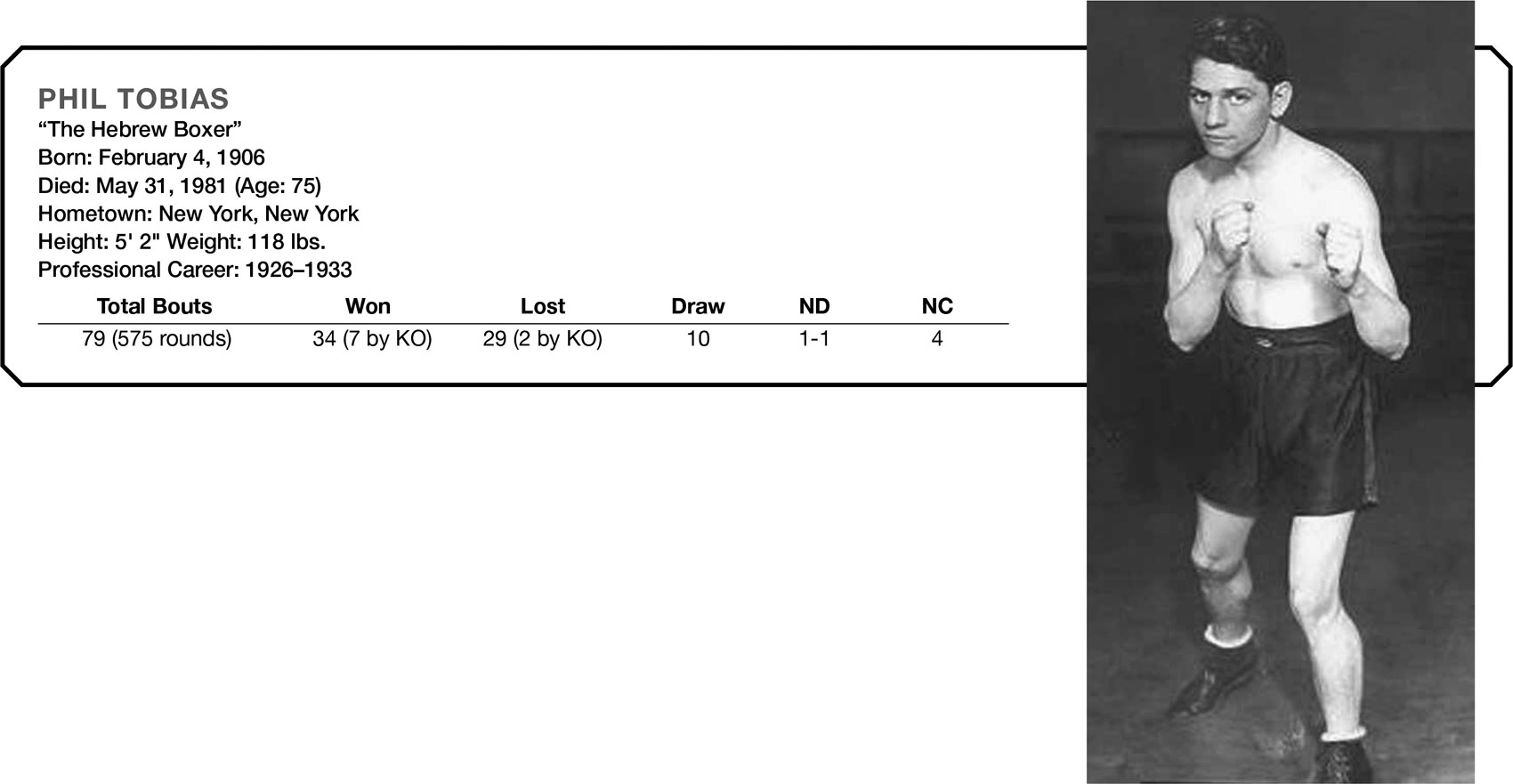

Phil Tobias

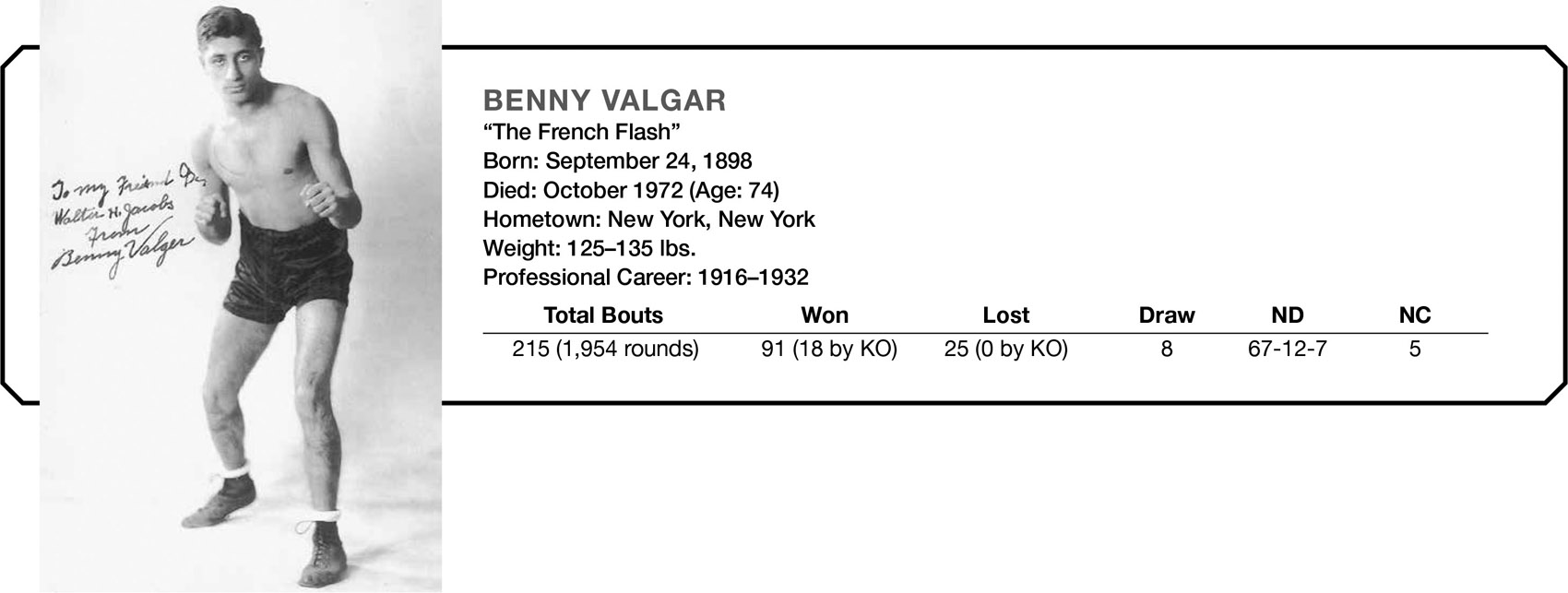

Benny Valgar

Sammy Vogel

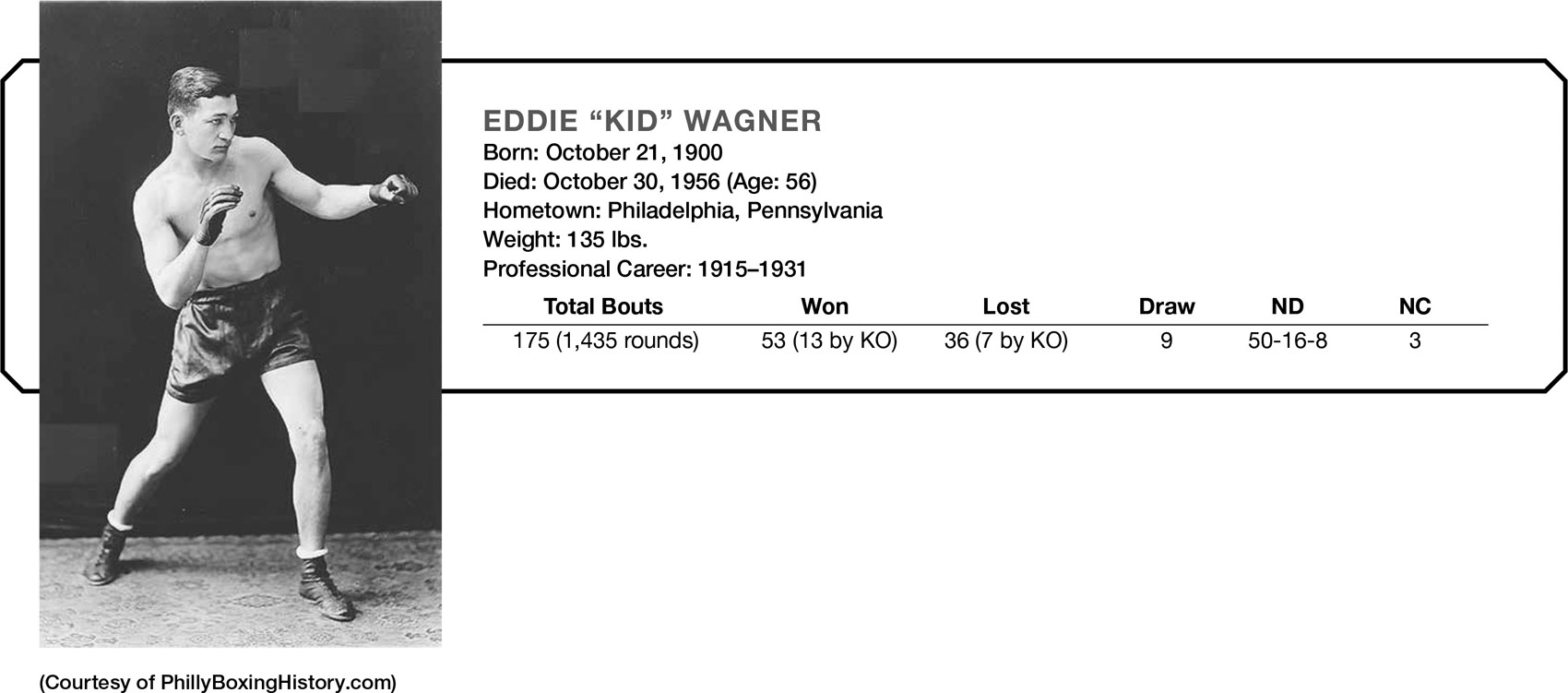

Eddie “Kid” Wagner

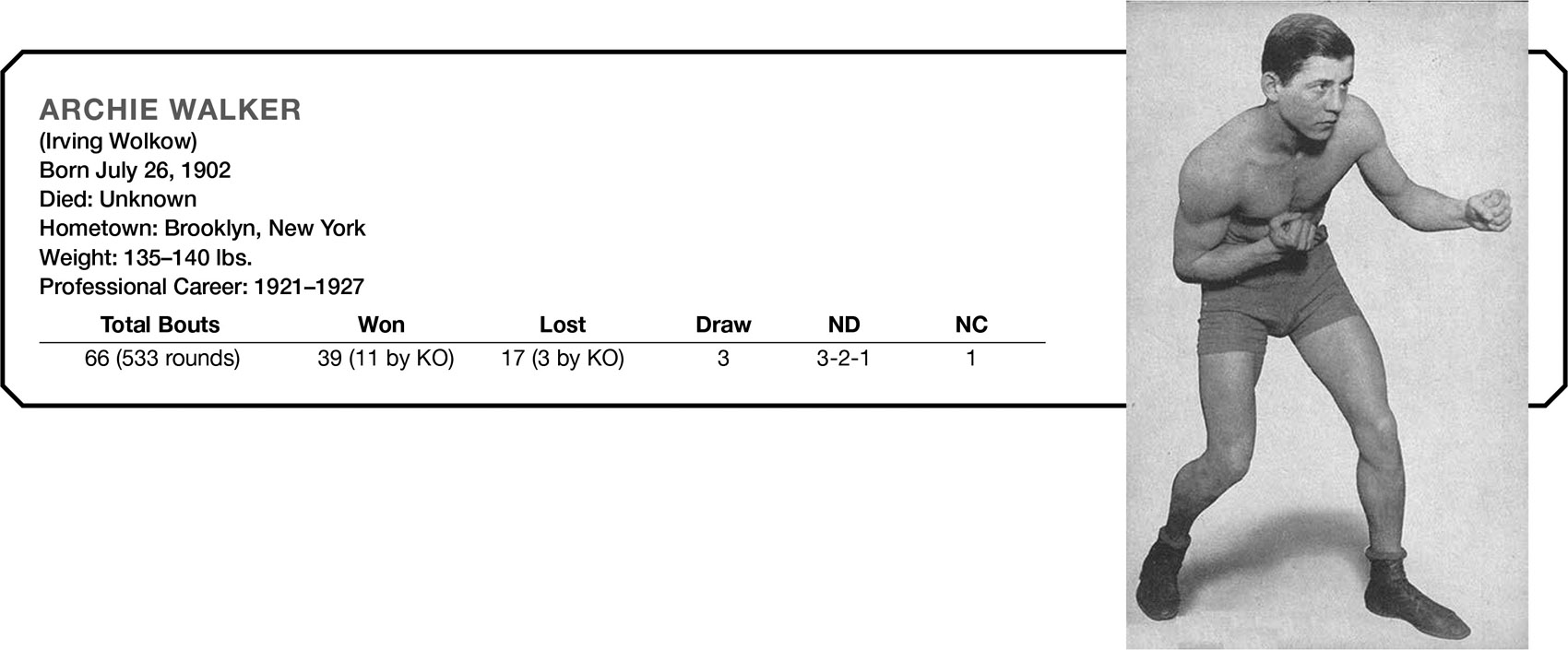

Archie Walker

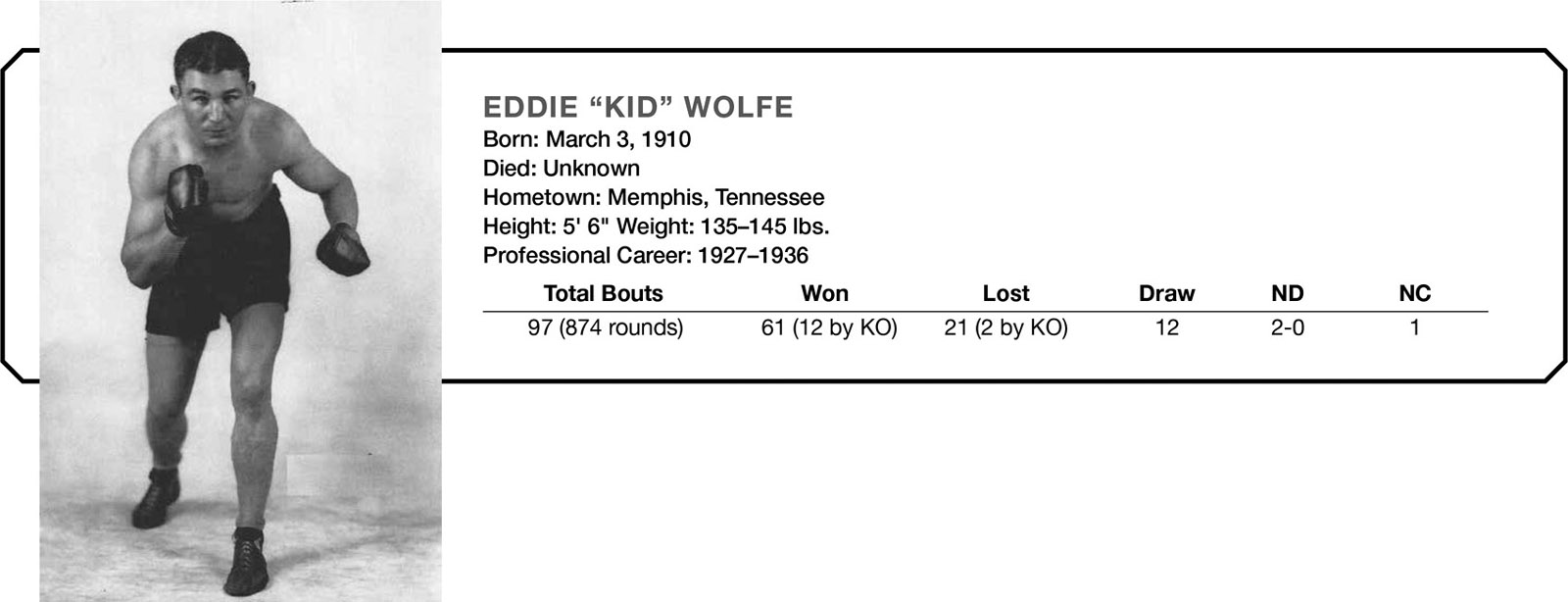

Eddie “Kid” Wolfe

Norman “Baby” Yack

* world champion

There is a strong case to be made for Georgie Abrams as the best Jewish middleweight of all time. But fate did not decree that he would win a title.

The son of a shoemaker, Georgie Abrams was born in Roanoke, Virginia, and raised in Washington, DC. He was a gifted athlete and an “A” student in high school, but the need to find employment during the Great Depression trumped any plans for higher education, even though two colleges offered him athletic scholarships in swimming and boxing. Georgie had been an outstanding amateur boxer, compiling a 62-3 record that included AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) and Golden Gloves titles.

Georgie’s parents gave him the middle name “Freedom” in honor of his being born on Armistice Day 1918. Twenty-three years later, on November 28, 1941, at Madison Square Garden, Georgie Abrams was hoping for a belated birthday present—the middleweight championship of the world. But first he would have to earn it by defeating one of the toughest fighters who ever lived, Gary, Indiana’s, “Man of Steel,” Tony Zale.

Abrams appeared to be on his way to a quick victory after dropping Zale for a nine-count in the very first round. But in the next round an errant thumb from Zale’s glove poked into Abrams’s left eye, causing severe pain and blurred vision. Making matters worse, in the third round an accidental head butt opened a cut over his other eye. With his left eye swollen shut from the fourth round on, Georgie fought the rest of the bout half blind.

Despite these handicaps, Abrams, using every ounce of his extraordinary boxing skill and courage, fought a sensational battle for 15 exciting rounds. The bout was very close, but in the opinion of the two judges and the referee, Zale’s incessant body attack in the late rounds had swayed the fight in his favor.

Georgie was confident that with two good eyes he could defeat Zale in a rematch. But it was not to be. On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and everything changed.

Abrams, like millions of other patriotic Americans, heard the call to duty and volunteered for service. In the navy he was involved with physical training of recruits. He also boxed in over 200 exhibitions in the Pacific and on ships. When he was discharged in 1946, Abrams was 27 years old, still young enough to resume his career.

After four tune-up fights, including a 10-round decision over highly ranked middleweight contender Steve Belloise, Abrams appeared to be near his old form. In his next fight he lost a disputed decision to the great French middleweight Marcel Cerdan. The 17,000 fans attending the fight in Madison Square Garden would have been satisfied had the bout ended in a draw.

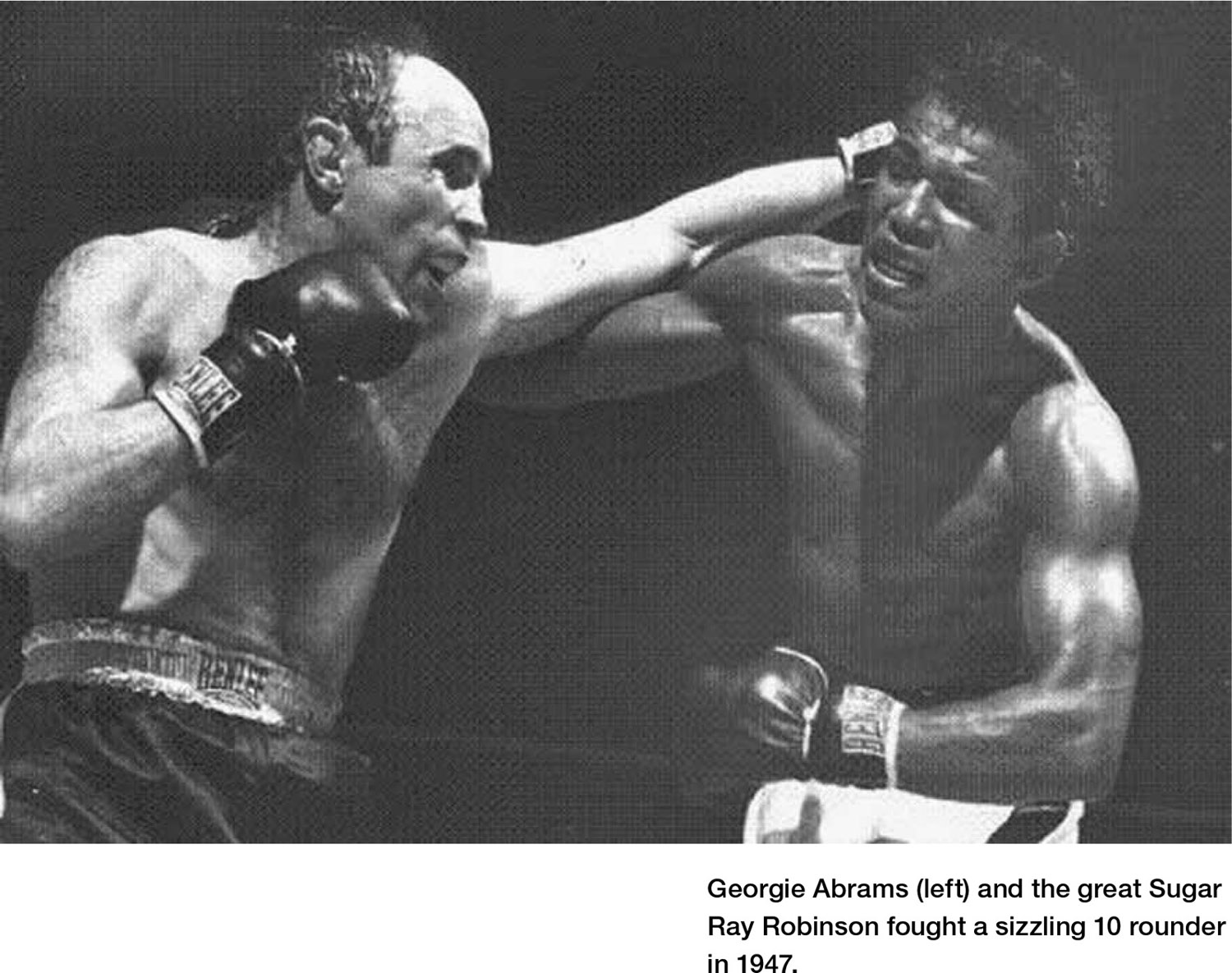

Georgie was anxious for another shot at his old foe, Tony Zale, also a navy veteran. Zale’s title had been frozen during his service. But before Abrams could challenge Zale, he had a tall order to fill: He had to get past the great Sugar Ray Robinson.

Robinson, the welterweight champion of the world, was then at the peak of his extraordinary powers. The “Harlem Dandy” was seeking to add the middleweight title to his already-impressive résumé. He’d already beaten a slew of tough middleweight contenders, including four victories over the only man to defeat him in 165 amateur and professional fights—the Bronx Bull, Jake La Motta. It didn’t matter to Robinson that he would be giving away 12 or more pounds to a heavier opponent. He figured to handle Abrams without much trouble.

But the overconfident Robinson was about to be surprised. Abrams was a master boxer and superb infighter. He was able to maneuver inside Sugar Ray’s longer reach, keeping most of the action at close quarters. During one exchange he even managed to open a cut over Robinson’s right eye.

Although hampered by blood running into his eye, Ray kept up a vicious body attack, but was still unable to land a knockout blow. At the end of 10 furious rounds, one judge scored for Abrams but was outvoted by the other judge and referee, both of whom gave the fight to Robinson by a narrow margin. The Madison Square Garden crowd immediately voiced their displeasure with a prolonged chorus of boos when the decision was announced.

Abrams’s impressive showing against Robinson and Cerdan is not the only evidence of his magnificent ring artistry. Before the war he challenged middleweight champion Billy Soose and won an easy 10-round decision. But since both fighters weighed over the middleweight limit of 160 pounds, the title was not at stake. The win was no fluke. Before he became champion, Soose (considered one of the best middleweight boxers of the 1930s) had already lost to Abrams twice. After his non-title win over Soose, an independent Midwest sanctioning organization called the “American Federation of Boxing” recognized Abrams as world middleweight champion, but the organization carried no clout and soon disappeared.

Leading up to his series of fights with Soose, Abrams outpointed Izzy Jannazzo and defeated former middleweight champions Lou Brouillard and Teddy Yaroz. The victories highlighted Abrams’s ability to adjust to any style. He could outmaneuver a rough infighter like Brouillard, and was equally effective at long range against master boxers Jannazzo and Yaroz.

As if these accomplishments were not enough to enshrine Abrams in every boxing hall of fame, he then took on the legendary Charley Burley, one of the most feared black fighters of the twentieth century. In his prime Burley was scrupulously avoided by champions in both the welterweight and middleweight divisions. On July 29, 1940, Abrams held Burley to a 10-round draw in the latter’s hometown of Pittsburgh. Two weeks later Abrams won a split 10-round decision over Cocoa Kid, another highly rated black contender.

Two months after his stirring effort against Sugar Ray Robinson, Georgie was back in Madison Square Garden to face the always-dangerous Steve Belloise. A year earlier Abrams had outpointed Belloise. This time Belloise, a vicious puncher with 45 knockout victories in 84 bouts, stopped him in the fifth round.

After a four-month layoff, Abrams faced another navy vet, former middleweight champion Fred Apostoli. The fight took place in Apostoli’s hometown of San Francisco. At the end of 10 grueling rounds, the local boxer won a split decision that could have easily gone the other way.

In Abrams’s last fight, on April 21, 1948, he was mauled by power-punching Anton Raadik, an opponent he’d easily outpointed a year earlier. The fight was stopped in the 10th round after Abrams had been decked twice. Chris Dundee, Georgie’s very capable manager, advised his fighter it was time to retire, and the obedient boxer agreed.

In his post-boxing life Abrams, a talented illustrator, tried to make a career for himself as an artist, but it did not pan out. Over the next 30 years he held a variety of jobs that included stints as an auto dealer, liquor salesman, and tavern owner. He lived in Florida for a while before settling in Las Vegas, where he worked as a security guard at the Tropicana Hotel. Twice divorced, he married his third wife, Vicki Lee, a former singer for Tommy Dorsey, in 1984. Abrams was already exhibiting signs of the progressive dementia that afflicts so many ex-fighters. But he never expressed regrets about his career, other than his frustration at not winning the middleweight championship.

MADISON SQUARE GARDEN

When Tex Rickard took control of Madison Square Garden in 1920, his goal was to establish the arena as the world’s foremost boxing showplace. So successful was Tex that in 1925, a new and much larger Madison Square Garden was built to accommodate twenty thousand persons. (The seating capacity of the old arena was about 12,000.)

“The house that Tex built” was the third and most famous incarnation of the legendary arena. The edifice occupied an entire block on the west side of New York’s Eighth Avenue, between 49th and 50th Streets. It stood as a monument to the sport from 1925 to 1968, when it was torn down and replaced by a new arena constructed atop the old Pennsylvania train station, at 33rd Street and Seventh Avenue.

The honor of performing in the world’s most famous arena was every boxer’s dream, even if it was only in a four-round preliminary. But to be featured in a Madison Square Garden main event was the equivalent of landing the lead role in a Broadway theatrical production! The prestige of topping the card at “The Garden” was second only to winning a world title. In the Roaring Twenties, at the height of Jewish activity within the sport, nearly half of the arena’s 288 shows featured a Jewish boxer in the main event. The fact that so many quality Jewish fighters had huge followings in New York City guaranteed that they would often appear in the featured bout of the evening. Overall, from 1900 to 1950, Jewish boxers appeared in 240 of 866 Garden main events. In twelve of those bouts, Jewish boxers squared off against each other. (See appendix for a complete list of Madison Square Garden main events featuring Jewish boxers.)

During boxing’s heyday a typical season at the 50th Street arena averaged 25 to 35 shows per year. The main event was usually preceded by six or seven preliminary bouts. In the summer months the fights were staged in outdoor arenas and stadiums. There was also a six-week hiatus in the spring while the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus took over the Garden.

Georgie Abrams’s record is immensely impressive. Very few fighters can boast of victories over Soose, Brouillard, Yaroz, and Cocoa Kid, or fighting on even terms with the likes of Burley, Cerdan, and Robinson. That says it all. They did not come much better than Georgie Abrams.

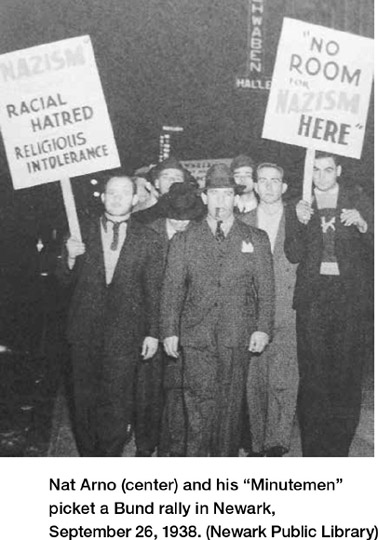

Nat Arno had his first boxing match on his 15th birthday. He had five more bouts before his father found out and forbade the youngster from continuing. Unable to fight in New Jersey without his parents’ permission, Arno hitchhiked alone to Florida in January 1926. Over the next 13 months, he lost only one of 49 fights. He returned home and reconciled with his father. All of his subsequent fights took place in New Jersey.

Arno established solid credentials in the junior lightweight division by holding his own against the likes of Pete Nebo, Vic Burrone, Young Zazzarino, Lope Tenorio, and Benny Cross. An aggressive and durable brawler, Arno was very proud of the fact that none of the 129 opponents he faced was able to stop him. The lone TKO loss on his record happened when the ringside physician ordered the bout stopped because of a cut above Arno’s right eye.

During Prohibition several of Newark’s boxers, including Arno, were employed by Longy Zwillman, the powerful New Jersey Jewish Mob boss, to transport and protect his bootleg shipments. Although Zwillman never became a boxer himself, he was a supporter of Newark’s Jewish boxers, and had sponsored several promotions.

In the mid-1930s Zwillman recruited and organized Jewish boxers from Newark’s Third Ward into a group called “The Minutemen.” The group’s purpose was to use their muscle to break up pro-Nazi meetings and propaganda activities in Newark. The Minutemen included boxers Benny Levine, Lou Halper, Abie Bain, Al Fisher, Puddy Hinkes, and Moe Fischer. It was active right up to the beginning of World War II, when America joined the fight against Nazi Germany.19

In 1941 Arno was drafted into the army. He saw action with the 29th Infantry Division, and was wounded during the Normandy invasion. After returning to civilian life he married and relocated to California, where he worked in the furniture industry. Arno’s “Minutemen” activities were renewed in the early 1960s when he heard that the American Nazi Party was staging a rally in downtown Los Angeles. He gathered a group of veterans to protest. During an anti-Semitic tirade by one of the speakers, Arno rushed the stage and threw him to the ground. He was arrested but released without being charged. Chalk up another victory for this feisty former pro boxer and veteran.

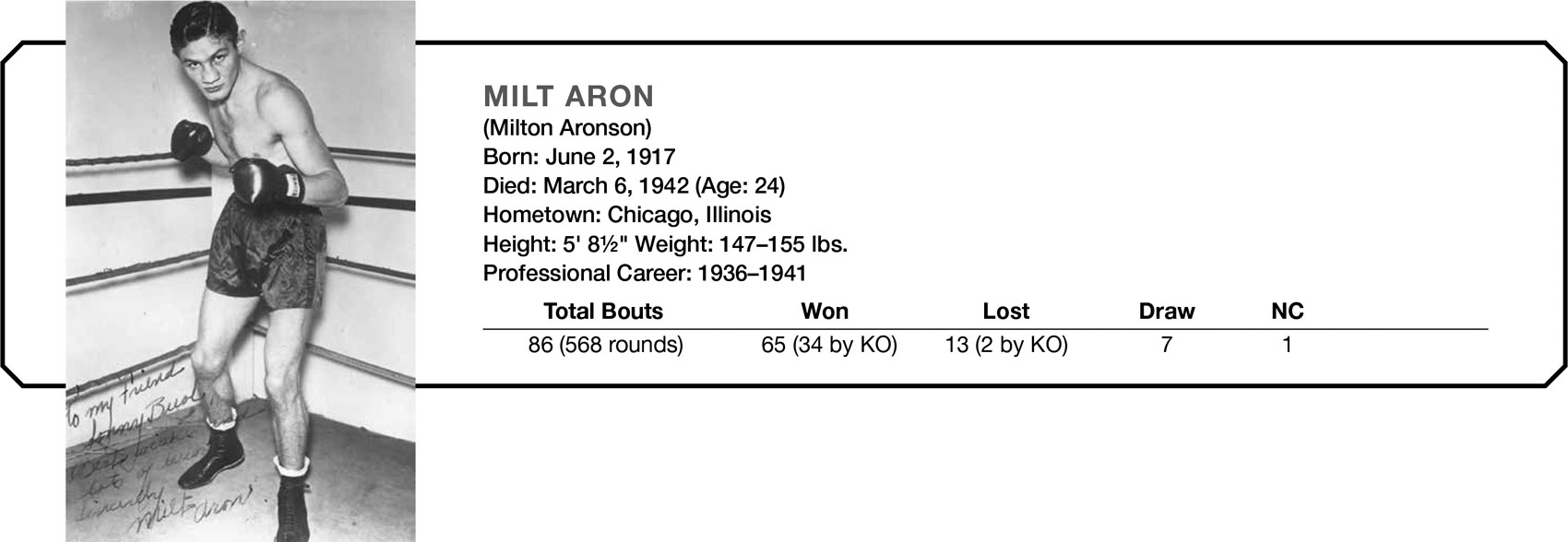

Ill-fated Milt Aron, the son of a rabbi, was one of Chicago’s most popular boxers. He was an aggressive pressure fighter with an exciting style and knockout power in his right fist.

Aron’s enthusiastic fan base extended well beyond his loyal Jewish following.

From 1934 to 1939, Aron lost only seven of 69 fights. Knockouts over Pete Nebo and Lou Halper, plus a decision over Chicago rival Harry Dublinsky, earned him a top-10 rating in the welterweight division. But it was his sensational knockout of Fritzie Zivic that moved him into the number-one-contender slot. Zivic had floored Aron three times before the Chicago slugger connected with a dynamite right cross in the eighth round that flattened the future welterweight champion for the full count. It was only the second time in 115 fights that Zivic had been knocked out.

Eight months after his victory over Zivic, Milt’s plans for a title shot against welterweight champion Henry Armstrong were disrupted when he dropped two decisions to contenders Mike Kaplan and Steve Mamakos.

Those losses moved Aron back a few notches, but he quickly rebounded with three consecutive knockout victories. He then agreed to a rematch with Zivic. This time the wily veteran turned the tables and stopped him in the fifth round.

In a tragic turn of events Aron came down with blood poisoning shortly after his second bout with Zivic. He battled the infection for five months before succumbing on March 6, 1942.

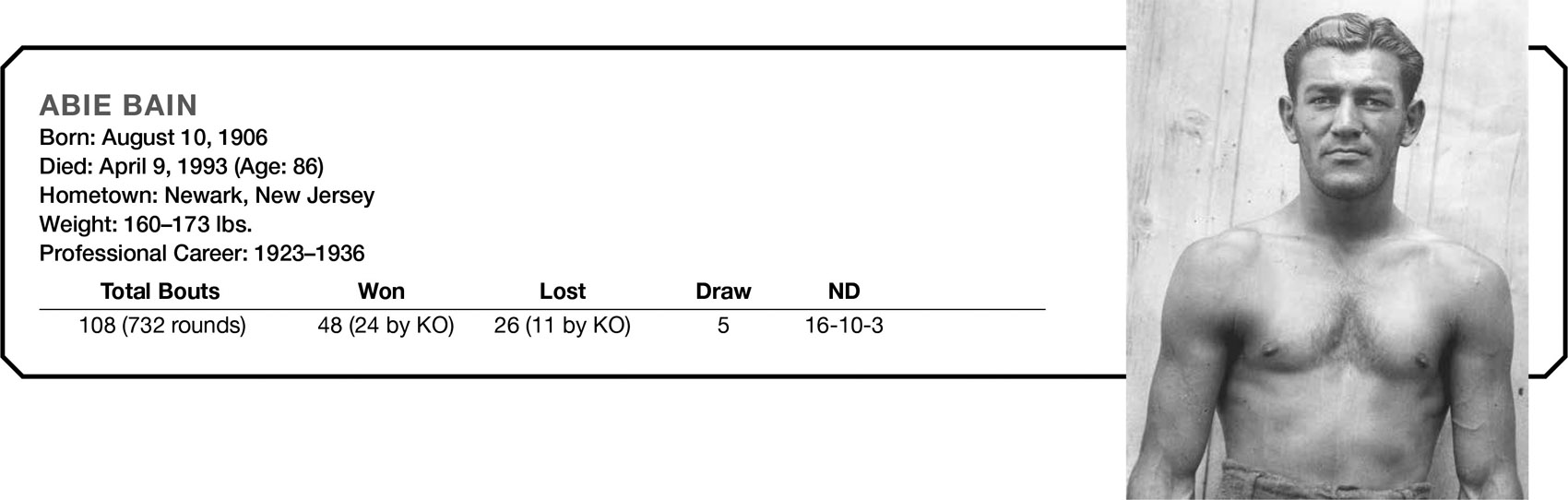

According to Abie Bain’s daughter, Riselle, the distinctive hoarse voice that Anthony Quinn used in his portrayal of “Mountain Rivera,” the washed-up fighter in the 1962 movie Requiem for a Heavyweight, was based on her father. Quinn and Bain had been friends for many years. Bain’s voice was actually the result of damage to his vocal cords caused by a botched surgery, and not his boxing career.

Abie Bain turned pro in 1923. Four years later he was mixing it up with the likes of Jack McVey, KO Phil Kaplan, Vince Forgione, Phil Krug, Rene DeVos, George Courtney, and Vince Dundee. All were highly ranked middleweight contenders.

In 1930 Abie moved up a division and challenged the great light-heavyweight champion “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom. Maxie stopped him in the 11th round when a severe laceration over Bain’s left eye caused the referee to halt the bout. Less than a year later he was matched with “Two Ton” Tony Galento, who outweighed him by over 50 pounds. Galento scored a fourth-round TKO. Like the fictional “Mountain Rivera,” Bain continued to fight past his prime. Thirteen of his 26 losses came in the last four years of his career.

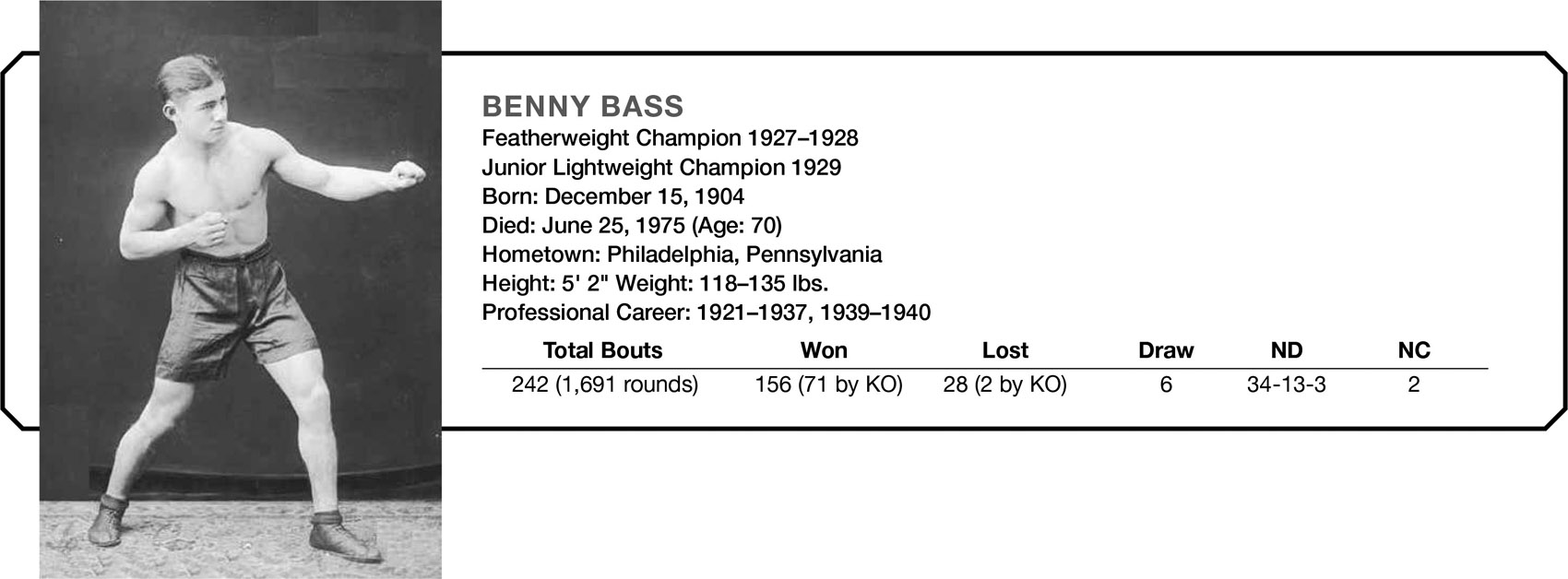

Benny Bass, a five-foot-two, pocket-size Hercules, stood out in an era that churned out great featherweight and lightweight boxers in assembly-line fashion. This tireless warrior fought an amazing 242 professional fights over 17 years, and won titles in two weight divisions. It would not be a stretch to place him among the all-time top-10 featherweight champions.

Bass was born in Kiev, Russia, on December 15, 1904, and came to America with his family in 1907. At the age of 10 he was selling newspapers on a busy Philadelphia street corner. The diminutive but scrappy youngster discovered his talent for fighting while defending his prized corner against bullies and competitors who sought to take over his territory.

From the ages of 12 to 16, Benny won 95 of 100 amateur bouts. In 1920 he qualified for the Olympic trials in the flyweight class, where he lost a close decision to the eventual gold medal winner and future professional champion, Frankie Genaro. Bass turned pro the following year under the management of Phil Glassman, handler of the great Lew Tendler and many other outstanding Philadelphia boxers.

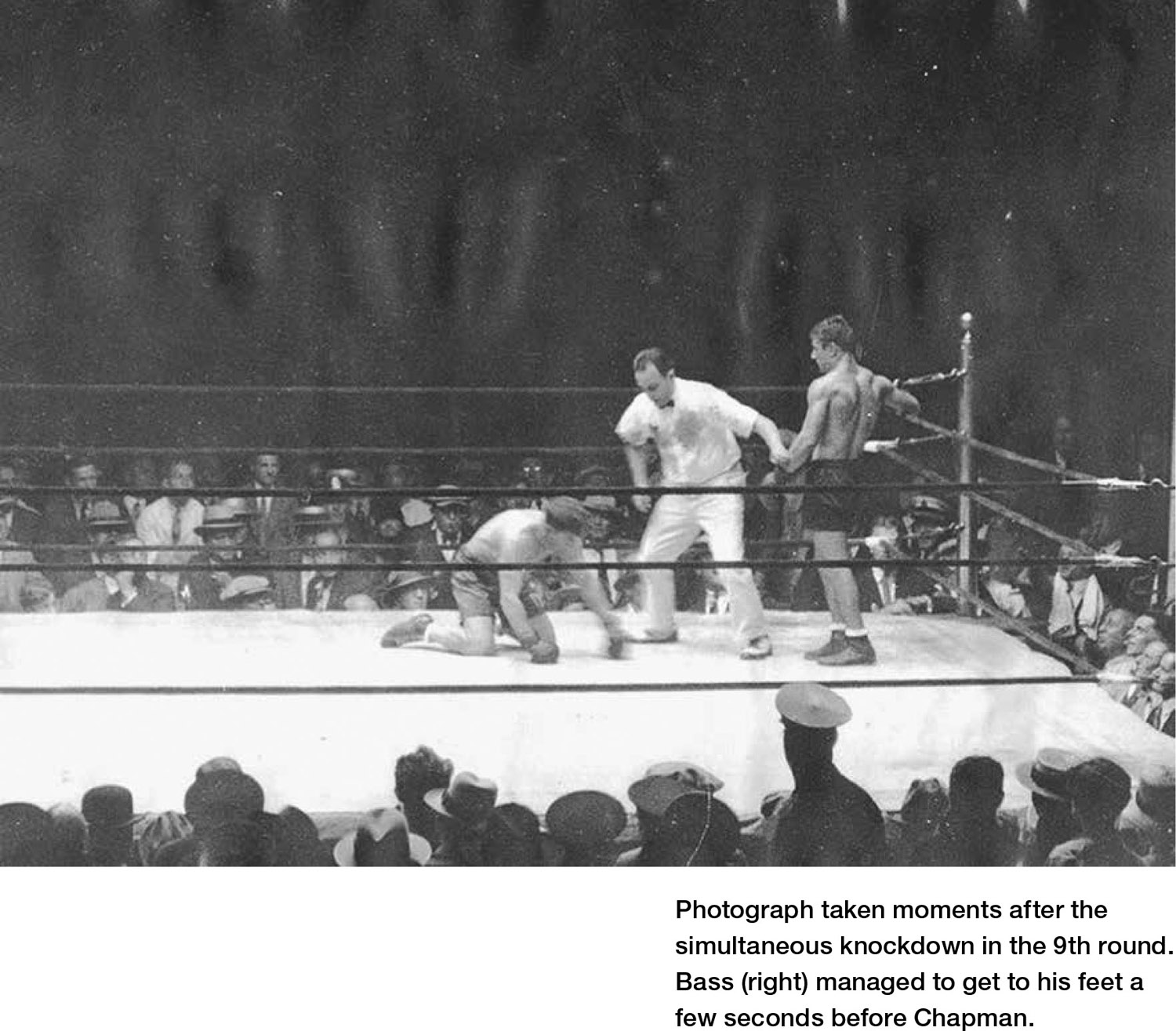

Five years later, with victories over Joe Glick, Chuck Suggs, Dominic Petrone, and Johnny Farr, Bass was rated the number-one featherweight contender. His 39 knockout triumphs in 115 bouts stamped him as one of the hardest punchers in the division. In 1927 he met Boston’s Red Chapman (Morris Kaplan) for the featherweight championship left vacant by Louis “Kid” Kaplan. Chapman, the number-two contender, had an impressive 64-13-1 (won-lost-draw) record, including 19 wins by knockout.

Over 30,000 fans paid their way into Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium to witness a great fight between two evenly matched fighters at the top of their game.

In the third round, an accidental head butt opened a cut over Bass’s right eye. Calling upon all his ring savvy and experience, Bass fought the next four rounds at long range and managed to foil Chapman’s attempt to target the injury and inflict further damage. In the seventh round Bass opened a bloody gash over Chapman’s eye.

With both fighters fearing a TKO loss, they decided to throw caution to the wind and go for a knockout. In the ninth round, in the midst of a savage exchange, Bass and Chapman landed simultaneous right-hand bombs to the jaw, resulting in that rarest of boxing spectacles—the double knockdown! The startled referee began counting over both fighters. Bass wobbled up at the count of seven while the referee continued to count over Chapman, who just managed to beat the count and last out the round. The 10th and final round had the exhausted and bloodied gladiators fighting on pure instinct. Bass was awarded a unanimous decision.

In the first defense of his title he faced the great Tony Canzoneri, who was recognized as world featherweight champ by the New York State Athletic Commission. Bass held the National Boxing Association version of the title. The bout was intended to unify the title.

After 15 furious rounds Tony was awarded a split decision for the undisputed championship. It was revealed afterwards that Bass had suffered a broken collarbone in the third round (some sources say 10th round), but despite the handicap had fought on, even rallying in the last few rounds to make the fight very close.

Following a four-month layoff (the longest of his career) to allow his broken collarbone to heal, Bass returned to action, scoring impressive victories over top contenders Harry Blitman, Gaston Charles, Davey Abad, and Harry Forbes.

In 1929 Bass fought Tod Morgan for the junior welterweight title. Knocked down in the first round, Bass came back to stop Morgan in the second round. It was only Morgan’s second KO loss in over 100 fights.

After two successful title defenses Bass took another crack at Canzoneri in August 1930. They both weighed over the 130-pound junior lightweight limit, so Bass’s title was not at risk if he lost. That was his sole consolation as he dropped another close decision to Canzoneri.

Benny won 11 of his next 13 fights. All seemed to be going well until he met Cuban sensation Kid Chocolate on July 15, 1931. In the first defense of his junior lightweight crown Bass suffered a deep cut over his left eye that caused the bout to be stopped in the seventh round.

For the remainder of his career Bass was competitive with the world’s top lightweights, but never received another title shot. Even past his prime he continued to average one to three fights a month.

In 1937 the great triple champion Henry Armstrong, then at the peak of his extraordinary powers, stopped the 32-year-old ex-champ in the fourth round. It was the only time Bass was ever counted out.

Bass retired after the Armstrong fight, but money problems forced a comeback in August 1939. Over the next nine months he won four of seven bouts, including one draw. In his last two bouts the aging veteran dropped 10-round decisions to Philly neighbors Jimmy Tyghe and Tommy Spiegal. The losses finally convinced him to hang up his gloves.

Bass was offered a job as a salesman for Penn Beer Distributors, and the popular ex-champ did quite well selling suds to the local barkeeps, restaurants, and supermarkets.

Although he was a grade-school dropout, those who knew Benny recall an individual of above-average intelligence who was reputed to be fluent in five languages—English, Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and Yiddish. He eventually moved from selling beer to a job in civil service, and for many years worked for the city of Philadelphia as a clerk in their traffic court system.

Benny Bass may have been small in stature, but he was a giant in the ring. If he were boxing today he’d be worth his weight in gold.

Baltimore’s Sylvan Bass began his career in 1924 as a 118-pound welterweight and ended it 12 years later as a 152-pound middleweight. He was very popular in his hometown of Baltimore when that city was one of the country’s hottest boxing venues.

A converted southpaw, Bass combined a powerful left hook with an aggressive infighting style. Top opponents included Jack Portney, Andy Divodi, Sergeant Sammy Baker, Georgie Levine, Young Terry, Cuddy DeMarco, and former welterweight champion Tommy Freeman. In 1933 he scored his greatest victory by winning an upset eight-round decision over future middleweight champion Ken Overlin. After Bass retired he served as matchmaker for the Century Athletic Club in Baltimore for 12 years.

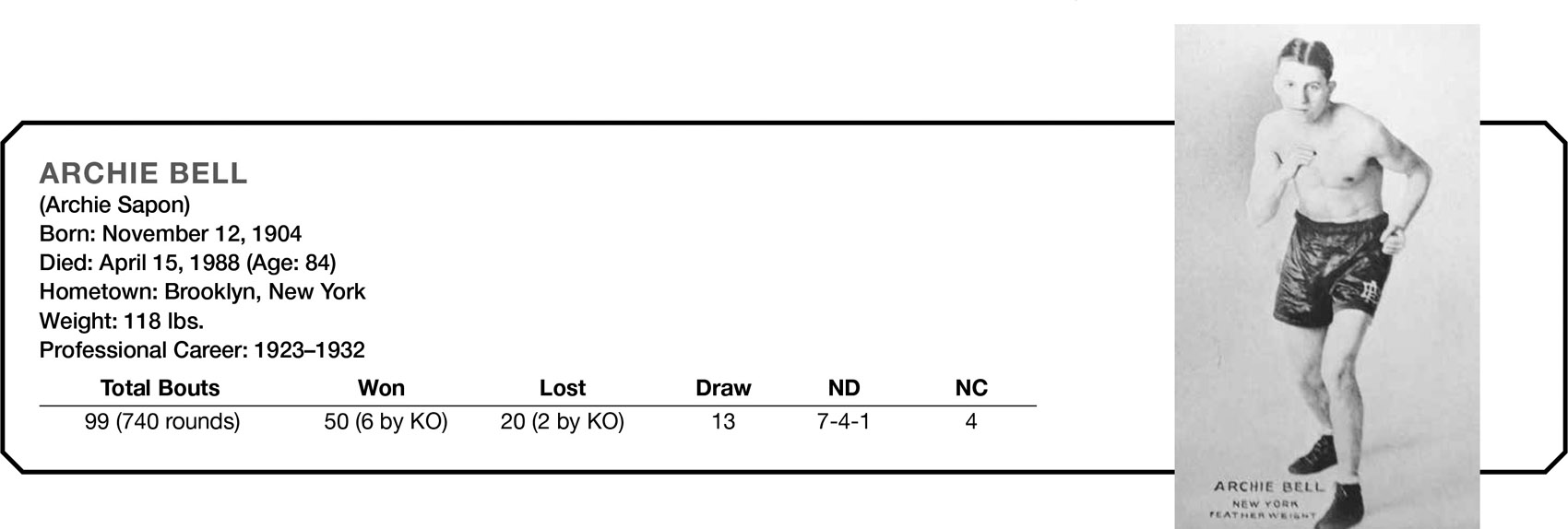

Archie Bell turned pro on December 10, 1923. Over the next 12 months he averaged a fight every two weeks. That type of activity, unthinkable today, was not unusual for a boxer of his era. Neither was the fact that 15 of his first 23 opponents were Jewish.

Archie fought in one of the most competitive eras in the history of the bantamweight division, and was good enough to be rated among the top 10 contenders for over four years. He beat many good fighters, but also had a habit of losing the big ones. Archie chalked up victories over contenders Dominick Petrone, Johnny Vacca, Young Nationalista, Eugene Huat, and Ignacio Fernandez, but lost to Nel Tarleton, Kid Francis, Teddy Baldock, and former champion Bushy Graham. In all, Bell fought nine fighters who at one time or another claimed a world title.

On December 2, 1932, in Los Angeles, Archie lost a 10-round decision to Mexican fireplug Alberto “Baby” Arizmendi for the California version of the world featherweight title. Thirty-five days later Arizmendi repeated his victory in San Francisco. Shortly after this fight Bell decided to hang up his gloves.

In a career spanning nine years and 99 fights, Archie Bell was stopped only twice, the first time very early in his career. The second stoppage was a TKO (cut over the eye) to future champion Tony Canzoneri.

Few fighters have entered the pro ranks with more natural talent than handsome, fun-loving Joe Benjamin. A flashy and clever lightweight boxer, Joe was a solid performer but lacked consistency. On a good night he was capable of outpointing the likes of Joe Welling, Benny Valgar, and Pete Hartley. On not-so-good nights he lost to Ritchie Mitchell, Johnny Dundee, and Joe Tiplitz. All were top-rated lightweights. (Mitchell was one of only two fighters to knock him out.)

In 1925 Benjamin was among 50 top lightweight boxers who took part in an international tournament to crown a successor to the retired lightweight champion Benny Leonard. In Joe’s first bout, in San Francisco, he outpointed Jack Silver in front of 20,000 fans. He then made the mistake of picking up an extra payday by taking an interim non-tournament bout against the formidable Ace Hudkins. After losing an upset decision to Hudkins, Benjamin was dropped from the tournament. Although only 26 years old, and still in his prime, Joe decided to hang up his gloves. He used his ring earnings to open a liquor store in Los Angeles.

Joe had been a stablemate of heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. They maintained a lifelong friendship. In fact, Benjamin was Dempsey’s best man when the heavyweight champion married actress Estelle Taylor in 1925. It was Dempsey who introduced Joe to the Hollywood crowd. The charming and friendly former contender became personal trainer to Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, connections that helped him land several movie cameo roles.

During World War II Benjamin enlisted in the US Marine Corps and served as a hand-to-hand-combat instructor. After the war he worked for many years as a salesman and West Coast public relations representative for Schenley Industries.

Judah Bergman donned boxing gloves at a very young age and quickly established himself as an exceptionally talented amateur boxer. But amateur trophies would not put food on the table. Judah’s father, a Yiddish-speaking Polish immigrant, worked as a tailor and was barely able to support his wife and seven children with his meager earnings. So in 1924 Judah Bergman joined the ranks of England’s professional prizefighters. He was three weeks shy of his 15th birthday.

Jackie “Kid” Berg always seemed to be in a hurry, as if he feared slowing down might cause him to sputter and stall. His nervous energy was even more pronounced in a boxing ring. The kid had the lungs and stamina of a marathon runner. He was one of those rare individuals who could move at top speed for 15 rounds and never seem to tire.

With his arms pumping like pistons the Kid set a relentless pace. His nickname, “The Whitechapel Windmill,” only hinted at what it must have been like to fight him. This is not to imply that he was just a “swarmer” with inordinate stamina. Jackie was well schooled in the basics. He possessed a fine left jab and could box effectively at long range.

Within five months of turning pro Jackie was fighting ten- and 15-round main events. From June 1924 to February 1928 he had 62 bouts, losing only three. Included among his victories was a 15-round decision over future featherweight champion Andre Routis.

In 1929 Jackie made his Madison Square Garden debut against lightweight contender Bruce Flowers, one of the finest African-American fighters of his era. Flowers, a slight betting favorite, had height and reach advantages over Berg, but none of that mattered.

Nineteen-year-old Jackie set a tremendous pace. Flowers was so busy defending himself against the frenzied, nonstop onslaught of punches that he was unable to launch an effective counterattack. He appeared, as one sportswriter put it, “like a scarecrow caught in a windstorm.” The Garden crowd, numbering close to 20,000, had not seen anything like it since the halcyon days of the legendary “Pittsburgh Windmill,” Harry Greb. Some reporters were even calling Berg “the English Harry Greb.”

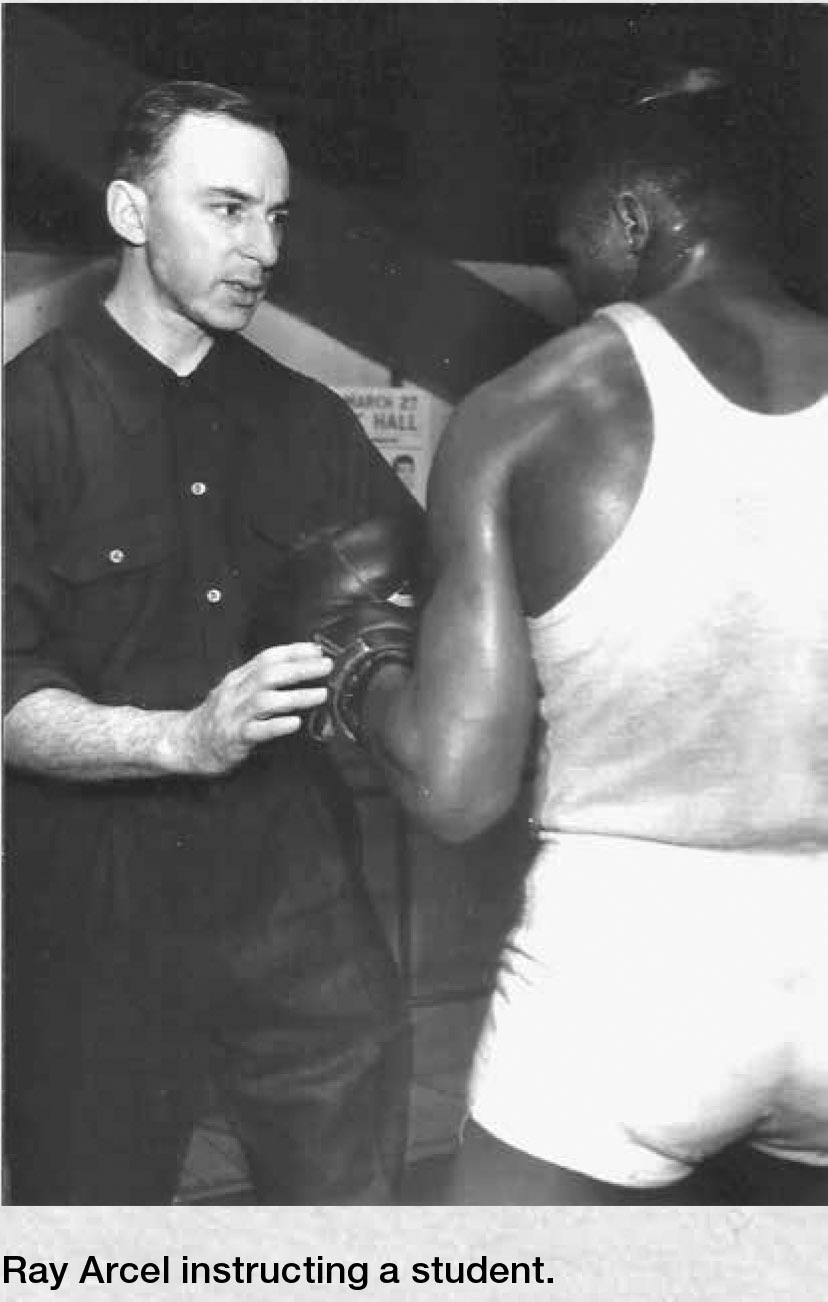

Berg had something else in common with Greb. He was an inveterate womanizer. Berg’s trainers often had to stand guard outside his bedroom to make sure he avoided female companionship on the night before a fight. Once, in a New York hotel lobby, Berg was chatting up an attractive brunette. He invited her to join him for dinner the following evening. Big mistake. The woman was the girlfriend of mobster Legs Diamond. Word got out that Legs was enraged and that his torpedoes were out gunning for Berg. Ray Arcel and Whitey Bimstein, Berg’s trainers, used all their charm and salesmanship to convince Diamond that it was all a misunderstanding. The duo quickly hustled Berg to an upstate training camp.

“The Whitechapel Windmill” became an overnight sensation in New York after his impressive showing against Bruce Flowers. Fight fans couldn’t wait to see him in action again. Only 13 days after their first encounter Jackie and Bruce Flowers were back in Madison Square Garden for a second go-round. Flowers told reporters that he’d been taken off guard by Berg’s unusual style, but would outbox him this time.

Like many other Jewish fighters, Jackie wore the Star of David on his boxing trunks. But on this occasion he decided to take the display of his heritage one step further by wearing his tallis and tefillin into the ring! The somewhat surreal scene was described in The Ring magazine:

Berg entered the ring wrapped in a tallis, the prayer shawl worn in synagogues. Around his right arm and on his head he wore tefillin, the small leather box containing sacred scripture, trailed by leather straps, which are put on by observant Jews for early morning prayers. Berg proceeded to go through an elaborate ritual of slowly unwinding the leather straps from around his body, tenderly kissing them, and placing the materials in a gold-embossed velvet bag, which he then carefully handed to his chief second, Ray Arcel. Berg’s trunks, as always, were adorned with the Star of David.20

The majority of his fellow Jews among the 20,000 fans in the sold-out arena were exhilarated by the display. But some skeptics questioned what they called a gimmick to pull in the crowds. Berg’s trainer, Ray Arcel, disagreed. “To understand why Berg always wore symbols of his religion into the ring, you had to know the man,” said Arcel. “True, he wasn’t what you call a religious Jew, but he was superstitious beyond reason. When I put the question to him one day, he seemed embarrassed. ‘It’s comforting to have God on your side no matter what you are doing,’ he said soberly.”21

In the return bout Berg got off to a slow start before taking charge in the third round, whereupon the action followed the same pattern as their previous encounter. Berg won another 10-round unanimous decision by “gluing his head to the Negro’s chin and slamming away at his middle.”22

“The Whitechapel Windmill” was boxoffice gold, and was kept busy for the rest of the year. Promoters all over the country wanted him to appear in their arenas. He won 13 additional fights in 1929. Among his victims were lightweight contenders Mushy Callahan, Phil McGraw, and, for the third time, the persistent Bruce Flowers.

In 1930 Jackie met the great Tony Canzoneri. Two years earlier Canzoneri had won and lost the featherweight championship. Now competing as a lightweight, Tony set his sights on adding another title to his impressive list of accomplishments.

The Canzoneri vs. Berg fight took place in Madison Square Garden before another sellout crowd. The 6–5 odds favored Canzoneri because he had beaten more quality opponents and was the harder puncher. But even as great a fighter as Canzoneri was, he could not cope with Berg’s maniacal but controlled fury. Canzoneri was given the full Berg treatment. The overwhelming speed and volume of Berg’s punches prevented him from mounting an effective counterattack. He did manage to land several haymakers, but the “Whitechapel Windmill” just kept plowing forward. During the course of the battle Canzoneri was cut over both eyes and bled from his nose and mouth. At the end of ten rounds of fierce fighting, Berg’s arm was raised in victory.

A month and a day after his spectacular upset of Canzoneri, the 20-year-old whiz kid was back in London to fight Mushy Callahan for the junior lightweight title (weight limit 140 pounds). By the 10th round, with his left eye swollen shut and bleeding from assorted cuts, Mushy’s corner signaled surrender by throwing a towel into the ring. Jackie was now a world champion, but he would not be satisfied until he won the more-prestigious lightweight crown.

On April 4, 1930, just six weeks after defeating Callahan, the new champion was back in Madison Square Garden, where he outpointed perennial contender Joe Glick in the first defense of his new title. Just three days later, in a non-title fight, he outpointed Jackie Phillips in Toronto, Canada. The following month, at Dreamland Park, in Newark, New Jersey, Berg defended his title for the second time by stopping Al Delmont in the fourth round. In June and July he outpointed the Perlick twins, Herman and Henry. The dizzying schedule reached a climax on August 7, 1930, when he faced the great Cuban boxing star, Kid Chocolate.

In an era loaded with talent, Kid Chocolate stood out among his peers as something very special. He fought as if performing a rumba interspersed with a dazzling array of combination punches. Up to that time no boxer, not even the great Benny Leonard, had fought with more balletic grace than this beautifully built, ebony-hued superathlete.

Kid Chocolate (real name, Eligio Sardinias Montalvo) had come to the United States from Cuba in 1928. He rocketed to the top of the featherweight division with a sensational string of victories, including a close decision (non-title) over lightweight champion Al Singer.

Not only was Kid Chocolate a master boxer, but he also possessed the speed to match Berg’s whirlwind style. Since turning pro 32 months earlier, “The Cuban Bon Bon” had gone through 56 opponents without a loss.

Although the Great Depression had begun a year earlier, the dream match between Kid Chocolate and Jackie “Kid” Berg attracted over 40,000 paying customers to New York’s Polo Grounds. The fight was rated “even money” by oddsmakers.

In the first three rounds Kid Chocolate utilized his great speed, shifty footwork, and quick counterpunches to keep Berg from getting inside. It usually took Berg a few rounds to warm to the task and switch into high gear.

Making good use of his almost-nine-pound weight advantage, Berg charged out of his corner in the fourth round and bulled the Cuban fighter into the ropes. Chocolate tried to fight back and get a rally going, but he could not sustain the assault for more than a few moments, nor could he match Berg’s excessive volume of punches. The only way he could slow down the assault was by clinching, a tactic that drew boos from the fans. There were no boos when Berg was awarded the 10-round decision.

Following his victory over Chocolate, Berg defended his title against Buster Brown, and then won a second decision over Joe Glick (non-title). In his final bout of 1930 Jackie exacted sweet revenge against former conqueror Billy Petrolle by winning a unanimous 10-round decision over the “The Fargo Express” at Madison Square Garden. In less than a year Berg defeated 11 quality opponents, counting among his victims the likes of Tony Canzoneri, Mushy Callahan, Joe Glick (twice), Kid Chocolate, and Billy Petrolle—an amazing record of accomplishment matched by very few fighters of any era.

Berg continued his relentless schedule in 1931. He defended his junior welterweight title twice within seven days. Ten weeks later he outpointed Billy Wallace in yet another successful defense of his title. It was Berg’s 95th victory against only five losses.

On April 24, 1931, only two weeks after defeating Wallace, Berg challenged Tony Canzoneri for the lightweight championship of the world. Since losing to Berg 15 months earlier, Canzoneri had won the lightweight title with a first-round knockout of Al Singer. Tony’s record showed only nine losses in 93 fights.

From the opening bell it was apparent that Canzoneri had no intention of letting the fight go to a decision. He was looking to land a haymaker, and that is exactly what happened in the third round, when he landed a perfectly timed right cross to the point of Berg’s jaw. Berg was caught coming into the punch (thereby exacerbating its effect) and was counted out for the first time in 106 fights.

Canzoneri agreed to a rematch on September 9, 1931, at New York’s Polo Grounds. Each man knew he would have to be at his best to win. In round eight it was still anyone’s fight when Canzoneri hit Berg below the beltline with a punch that sent Jackie to the canvas, writhing in pain. The New York Commission’s rules stated that a fight could not be won on a foul since every fighter was required to wear a foul cup under his boxing shorts as protection against errant punches below the belt. Berg struggled to his feet and continued fighting but never regained his momentum. He staged a furious rally in the 15th and final round, but it was not enough to make up for the rounds he had lost. The unanimous decision went to Canzoneri. If the fight had been staged in England—its originally intended venue—the championship would have changed hands when Berg was fouled in the eighth round.

By the mid-1930s the marvelous fighting machine had finally begun to slow down. But even past his prime, “The Whitechapel Windmill” could still surprise with an outstanding performance. He appeared to be finished after lightweight contender Pedro Montanez stopped him in five rounds at New York’s Hippodrome in 1939. Yet three months later he upset the odds by outpointing master boxer Tippy Larkin. Previous to his meeting with Berg, Larkin had lost only four of 69 fights. Jackie returned to England to finish out the balance of his career.

During World War II Jackie enlisted in the Royal Air Force. While in the service he married for the second time (his first marriage had ended in divorce). In 1946, with a wife and infant daughter to support, he decided to open a restaurant in London’s Soho district. After selling the restaurant he worked for many years as a stuntman and stunt coordinator for films produced in England. To the end of his life he remained an active and beloved member of the English boxing fraternity, and his presence was often requested at major prizefights.

One could say that the lineage of England’s great Jewish prizefighters that began with Daniel Mendoza 150 years earlier had come to an end with the retirement of the one and only Jackie “Kid” Berg.

Maxie Berger was one of the greatest boxers to ever come out of Canada. He first laced on the gloves in 1931 at the Montreal Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA). Three years later he capped off a sterling amateur career with a silver medal at the British Empire Games. Maxie turned pro in 1935 and breezed through his first 10 opponents before moving to New York City.

The following year he outpointed Dave Castilloux for the Canadian lightweight championship. Less than a month later he successfully defended the title with a 10-round decision over Orville Drouillard. In 1938, after defeating veteran contender Wesley Ramey (gaining revenge for two previous losses to Ramey), the Montreal Athletic Commission recognized Berger as the junior welterweight champion of the world. But no one beyond the city’s borders gave any credence to the title.

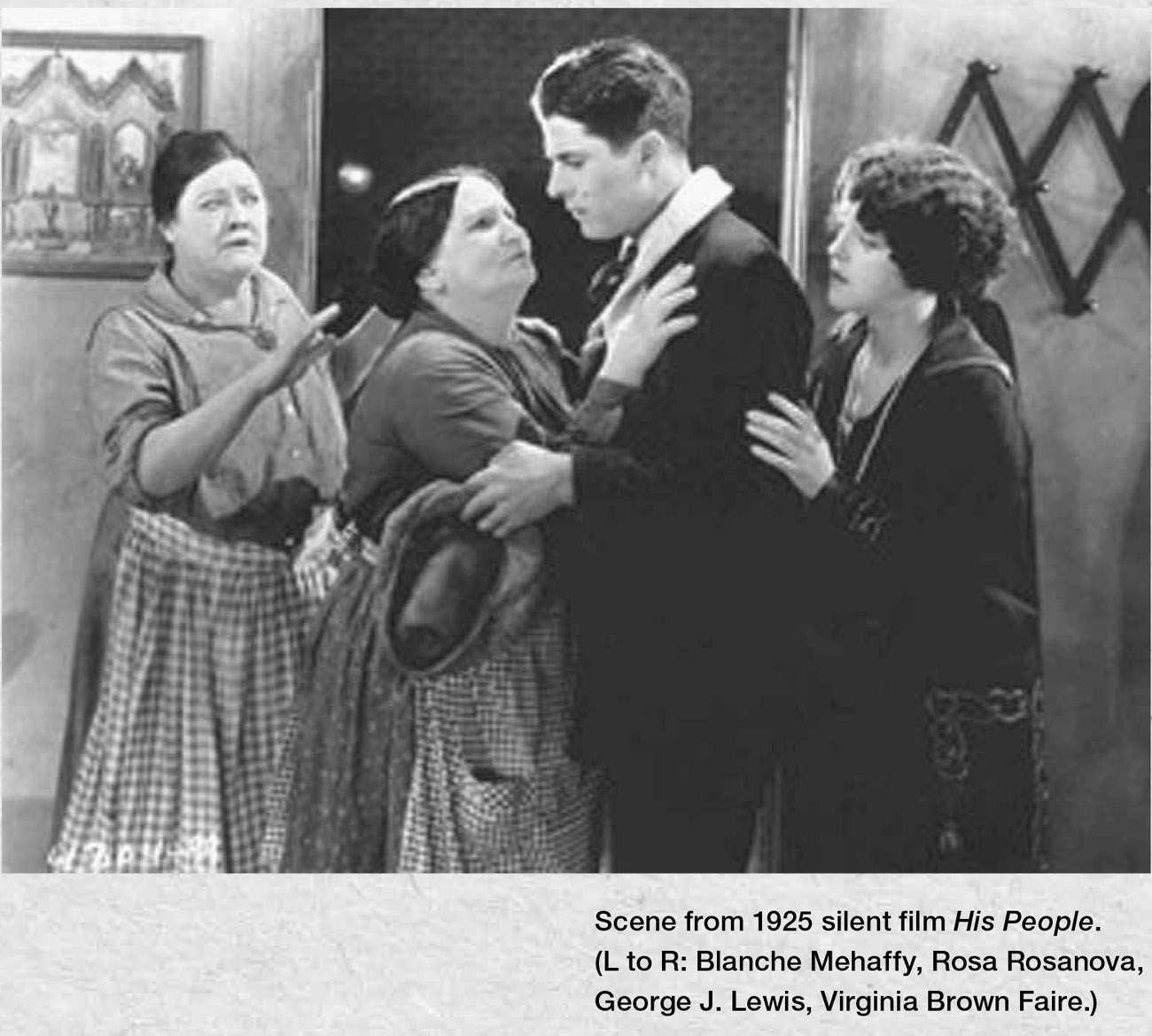

ART IMITATES LIFE

One of the best of the silent-era boxing films is a 1925 melodrama titled His People. The film tells the story of a Jewish family on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Two brothers, Sammy and Morris Cominsky (played by George Lewis and Arthur Lubin), are the sons of poor immigrant parents. Good son Sammy decides to become a professional boxer to help pay for his older brother’s law school education and ease his family’s financial burden. (Papa Cominsky barely ekes out a living as a pushcart peddler.)

Sammy cannot let his family know that he is a boxer, so he fights using the name “Battling Rooney.” When a nosy neighbor spills the beans about Sammy’s boxing activities, his religiously observant father (Rudolph Schildkraut) is horrified and orders Sammy out of their home. “G-d of Israel! That a son of mine should sink so low.”

Meanwhile, Sammy’s older brother Morris, the lawyer, is revealed to be a self-absorbed and unscrupulous social climber. He becomes romantically involved with the daughter of a wealthy senior partner in a prestigious law firm. But Morris is so embarrassed by his family’s poverty and Old World ways, he tells his fiancée that he is an orphan. The plot thickens when Papa Cominsky is taken ill and is told by a doctor he must move to a warmer climate. With no funds to pay for the move, Sammy agrees to a lucrative but dangerous fight against an experienced opponent. Needless to say, all dilemmas are eventually resolved. Sammy wins the big fight, Papa recovers, and Morris comes to his senses and asks forgiveness from his family for his boorish behavior.

The film, directed by Edward Sloman, still holds up. In his book, Hollywood’s Image of the Jew, author Lester B. Friedman wrote, “Sloman’s compelling vision of the painful depths and joyous heights of immigrant life endow the film with an exuberant vitality that captivates modern filmgoers and enlightens film historians.”23

They loved Maxie in Montreal, but the big money was in New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago. Only 32 of his 131 fights took place in Canada.

In order to smooth the way for Maxie in New York City his managers had to cut in a character named Jimmy Doyle. Only later did Maxie find out that Doyle’s real name was Jimmy Plumeri, a garment-center racketeer who managed fighters on the side.

Maxie impressed the New York fans with sensational victories over contenders Wesley Ramey, Leonard Del Genio, Enrico Venturi, Billy Beauhuld, and Bobby McIntire, but he is best remembered for a fight he lost. On February 2, 1942, he met 20-year-old phenomenon Sugar Ray Robinson in Madison Square Garden. A crowd of 12,000 excited fans saw Robinson win by a TKO in the second round. Berger had been dropped twice before the referee intervened to stop the bout—some thought prematurely. It was the first time in 97 professional fights that Maxie was stopped, and only his 13th loss up to that time. His share of the gate was $2,200.

Maxie continued to meet highly rated opponents throughout his career, even after he’d passed his prime. In his final two years as a pro he was outpointed by Beau Jack and stopped by Ike Williams. He finally retired in 1946 after a KO loss to George Costner.

A few weeks into his retirement Maxie was approached by professional gamblers with a proposition for one more bout. In 1972 he related the story to Montreal Gazette journalist Marvin Moss: “They offered me $10,000 to fight Johnny Greco. There was one catch: I had to lay down. I told them ‘No way.’ I wasn’t going to go against something I believed all my life. So there never was any fight. And that was the end of it.”24

Maxie used part of his boxing nest egg to open a store in Montreal that sold custom-made shirts. But the punches he took over the course of his 131-bout career eventually took a toll on his health. He was 83 when he passed away, but the last 10 years of his life were marked by increasingly severe dementia.

Perhaps the most underrated of all the Jewish champions is Jack Bernstein. Noted boxing historian Hank Kaplan ranked Bernstein the thirdgreatest Jewish lightweight after Benny Leonard and Lew Tendler.25

Indeed, very few lightweights could boast of having beaten the likes of Johnny Dundee, Solly Seeman, Babe Herman, Ray Miller, Jimmy Goodrich, Rocky Kansas, Eddie “Kid” Wagner, and Luis Vicentini. Throw in a 15-round draw with a prime Sammy Mandell and an unpopular loss to top contender Sid Terris, and it becomes obvious that Jack Bernstein, in his prime, was a fighter for the ages.

The boy who dropped out of grade school to help his father peddle fruit from a pushcart started fighting for money at the age of 14 in his hometown of Yonkers, New York. Since there weren’t many Jewish boxing fans in Yonkers, young John Dodick (Bernstein’s real name) began his boxing career as Kid Murphy.

From 1914 to 1920, Kid Murphy paid his dues the old-fashioned way—by fighting often and meeting fighters of every conceivable style. The muscular lad displayed an aggressive twofisted attack combined with an effective left jab and airtight defense.

In 1920 Kid Murphy acquired a new manager who told him that since he did most of his fighting in New York City, he’d attract an even larger following with a Jewish name. To honor his hero, turn-of-the-century Jewish boxing star Joe Bernstein, Kid Murphy renamed himself Jack Bernstein. The change seemed to have a rejuvenating influence on his career.

Jack Bernstein became a force to be reckoned with in the lightweight division. In 1922 he lost only one of 17 fights. He reversed the loss to tough Archie Walker and then went on to decision Solly Seeman, Babe Herman, and Eddie “Kid” Wagner—three of the world’s best lightweight contenders.

In 1923 Bernstein fought the great featherweight champion Johnny Dundee for the revived junior lightweight title at Brooklyn’s Coney Island Velodrome. Dundee, in his 14th year as a pro, had already fought over 300 professional fights and was past his prime. Even so, Dundee was considered such a great fighter, he was a four to one favorite to defeat Bernstein.

Fifteen thousand fans saw Bernstein defeat the odds and win a unanimous decision over Dundee in a scorching 15-round battle.

Seven months later Bernstein lost the title back to Dundee at Madison Square Garden. Rumors of a fix were rampant after the two judges voted for the challenger (the referee had scored it for Bernstein). The Garden audience was in an uproar at the injustice, as Bernstein appeared to have won ten of the 15 rounds. Not one of more than a dozen sportswriters covering the fight thought Dundee deserved the win.

Bernstein returned to Madison Square Garden three weeks later where he fought a 15-round draw with future lightweight champ Sammy Mandell. Nine months later he fought the rubber match with Dundee (now an ex-champ, having lost the title two months earlier). He easily outpointed the fading ring great.

From 1924 to 1927 Bernstein remained a viable title threat, with victories over Tommy O’Brien, Cuddy DeMarco, Ray Miller, and former champion Jimmy Goodrich. His return match with Sid Terris in 1925, at New York’s Polo Grounds, was yet another travesty of boxing justice. The decision for Terris shocked the audience. For the first time “The Ghetto Ghost” was booed as his hand was raised in victory. But fan disapproval could not change the result.

In 1927 Jack began to notice that he was losing stamina in the late rounds. This had never happened before. Something was wrong, but he could not figure out the cause. After losing twice to Yonkers neighbor Bruce Flowers, and then dropping a 10-round decision to Joe Glick in the new Madison Square Garden, Jack decided a long rest was in order.