We will win this war because we are on God’s side.

—HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION JOE LOUIS, MADISON SQUARE GARDEN, WAR BOND RALLY, 1942

The war in Europe and Asia had been raging for more than two years when Japan launched a surprise air attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The attack killed over 2,300 Americans and destroyed or damaged 20 warships and over 300 aircraft. The next day Congress declared war on Japan. Within days Japan’s ally, Germany, declared war on the United States. The conflict was now global.

Over the next four years 16 million Americans answered the call to duty and took part in the monumental effort to defeat Nazi Germany and Japan. Included among these fighters for freedom were 550,000 American Jews, including women, who served in the armed forces. The boxing community did its part. Over 4,000 professional prizefighters, in addition to many trainers and managers, interrupted their careers to serve in various branches of the military.

On the home front boxing was a popular diversion for the civilian population. In every city, fans flocked to arenas in hopes of taking their minds off the war for a few hours. But as the months turned into years, increasing numbers of young men were being drafted or volunteering for service, including many established boxing stars. In addition, four world champions had their titles frozen for the duration of the war while they served in the armed forces.

Bill Goodman, a former licensed corner man and a student of the boxing scene for over 60 years, believes the shortage of talent eventually led to lowered fan appreciation for the art of boxing. Goodman comments:

In my opinion after America entered the war, the sport began its downward slide in terms of the quality and quantity of fighters. Matchmakers and promoters had major problems keeping a show together because so many talented prospects were in the service and no longer available. The ones left were lesser-caliber fighters who didn’t have the talent—or if they did have the talent, they weren’t being nurtured and taught as they had been prior to the war. As a result many unschooled club fighters advanced to main-bout status. The fans got used to seeing a less-sophisticated style of boxing—crude, but with plenty of slam-bang action. It was no longer necessary to be the stylist that it was prior to that period. The quality went down, and the public got used to it.

For every accomplished boxer who headlined a card during the war, there were scores of other less-talented club fighters who achieved the very same goal.

Fans wanted to see the Rocky Graziano and Beau Jack style of fighter, the action guys that kept going, kept punching, and looked for that knockout. For the first time posters began advertising fighters with phrases like “He never stops punching from bell to bell.”

I’m not knocking Beau Jack. He was an interesting, colorful fighter and a hell of a campaigner, always trying, but nevertheless, he wasn’t the classic boxer we saw in the prewar years. As good a fighter as Beau was, he wasn’t on the level of a Barney Ross, Tony Canzoneri, Sammy Mandell, or Kid Chocolate. Of course, not everyone could measure up to these great fighters, but you had an endless number of outstanding fighters in the 1920s and ’30s.

Very few outstanding boxers were developed during or after World War II. Most of the great fighters from that era began their careers prior to the war, and that includes the great black fighters from the 1940s, such as Ezzard Charles, Charley Burley, Archie Moore, Holman Williams, Eddie Booker, Lloyd Marshall, and Jimmy Bivins. Even after the end of the war, they were not developing the same type of talent that they did before the war. There were some good fighters—I won’t say there weren’t good fighters— but as far as I’m concerned, they weren’t as good as the fighters developed in the 1910s, ’20s, and ’30s. Yes, here and there you had an outstanding guy, but for the most part, they were not up to those fighters quality-wise.1

A positive result of the boxing scene in the United States at this time was that it opened doors to a few outstanding African-American boxers who were finally getting a chance to appear in feature bouts at major venues, including Madison Square Garden. But, as noted by Bill Goodman, for every quality boxer who shared top billing, there were also scores of less-talented pugs being promoted to main events that in normal times would not have merited the honor.

Boxing’s continuing popularity on the home front made promoters think that the end of the war would boost the sport’s fortunes even more, as name boxers returned to civilian life and took up where they had left off. But this optimistic view turned out not to be true.

Nobody could see it coming, but the immediate postwar years would turn out to be the last hurrah for boxing’s great Golden Age of talent and activity. At the end of World War II the US Congress enacted the GI Bill of Rights that made it possible for millions of returning veterans to get low-cost mortgages and cash payments of tuition to acquire a college education or technical training. The GI Bill accelerated the entrance of returning vets into the economic mainstream and, combined with a booming postwar economy, was responsible for jump-starting the modern middle class in America.2 Nevertheless, a large portion of America’s African-American population was still struggling to attain their piece of the American dream.

In the 1930s the rise of Joe Louis and Henry Armstrong had opened up greater acceptance and opportunities for black fighters. That trend would be reinforced in subsequent decades by the social and demographic changes that significantly reduced the number of white boxers. By 1948 nearly half of all contenders were black. Most cited Joe Louis as their inspiration. Ten years earlier Italian Americans were the dominant contender group. Now they were in second place, followed by Mexican Americans.3

The mass exodus to the suburbs by the emerging middle class (including about a third of American Jews) that began in the late 1940s and continued through the 1950s took with it many of boxing’s core customers, thereby hurting the network of small urban arenas that relied on their patronage to stay in business. Arenas that had been accustomed to drawing $4,000 to $5,000 per show on a regular basis saw revenues drop to $1,000 or less.

“No longer is there a stream of young fighters flowing into the ring,” wrote New York Times reporter John R. Tunis in 1949. “The lifeblood of boxing is thinning out, perhaps temporarily, but it is thinning out, nevertheless. In my own state, Connecticut . . . fighting is poorer in quality and quantity today than before the war.”4

By the end of the 1950s, the ranks of professional boxers in the United States had been depleted by 50 percent as compared to figures before the war. The retirement of the great but aging heavyweight champion Joe Louis in 1949 was symbolic. Boxing was in desperate need of a charismatic heavyweight champion to boost interest, but there was none on the horizon. Fan interest was waning, the public’s tastes were changing, and there was growing competition from other sports. Boxing’s image was also tainted by extensive press coverage of congressional investigations concerning infiltration by organized-crime figures and allegations of fixed fights.

Bill Goodman witnessed the changes firsthand: “[Boxing] wasn’t something a guy wanted to be a part of anymore. And the people in the neighborhoods didn’t make fighters heroes like they had in the past, with the Jewish and Italian fighters who came from the Lower East Side, Brooklyn, or the Bronx.”5

Just in the nick of time, the new medium of television arrived to save the day. Television and boxing were made for each other. The shows were relatively easy and inexpensive to produce. The camera only had to focus on the small space occupied by the ring, and commercials could conveniently be inserted during the one-minute break between rounds.

Television rejuvenated the sport and created millions of new fans almost overnight. By 1952 televised boxing was reaching 5 million homes, representing 32 percent of the available audience. In 1955 the figure had climbed to 8.5 million homes. From 1949 to 1955 boxing reportedly sold as many television sets as Milton Berle, and it rivaled I Love Lucy in the ratings. Fight fans could now watch all-time greats such as Joe Louis (attempting his comeback), Sugar Ray Robinson, Ezzard Charles, Rocky Marciano, Jake LaMotta, Archie Moore, Ike Williams, Willie Pep, and Sandy Saddler from the comfort of their living rooms.6

New stars emerged and quickly became household names. Kid Gavilan, Chuck Davey, Ralph “Tiger” Jones, “Irish” Bob Murphy, Carmen Basilio, “Hurricane” Jackson, Gene Fullmer, Joey Giardello, and Bobo Olson developed huge followings based on their frequent TV appearances.

But there was a downside to televised boxing. The greedy moguls and their mobster affiliates used the new medium to exploit boxing for all it was worth. They ended up killing the golden goose by saturating the airwaves with boxing almost every night of the week.

In 1949 the Mob-riddled International Boxing Club (IBC) became the sport’s major promotional arm, acquiring exclusive TV contracts with the NBC and CBS networks. The networks agreed to pay $90,000 a week for the right to broadcast IBC fights. The titular head of the organization was James D. Norris, the wealthy scion of a family with huge real estate and commercial holdings that included major arenas and racetracks. Early on, Norris had reluctantly decided it would be easier to run his boxing empire with the Mob’s cooperation, since they already controlled (through front managers) many top fighters desirable to television. Before he made his pact with the devil, several Mob-controlled fighters claiming injuries had pulled out of Norris’s televised promotions shortly before they were scheduled to appear, causing him to scramble for substitutes. Needless to say, sponsors were not happy.

In order to avoid future disruptions, Norris agreed to a silent partnership with the notorious underworld boxing czar Frankie Carbo and his chief lieutenant, Frank “Blinky” Palermo, thereby gaining access to many of the sport’s biggest names. But there was a huge trade-off: With Mob cooperation came loss of control. Everyone in the boxing industry knew the real powers pulling the strings of the IBC operation were Mafia hoodlums Carbo and Palermo. Their association with Norris granted them even more influence to fix fights and buy or muscle their way into the management of top contenders and world champions.

From 1949 to 1953 the IBC monopoly controlled the promotional rights to 36 of 44 championships staged in the United States, including all of the title fights in the very popular heavyweight and middleweight divisions. Carbo’s role in the IBC had escalated to the point where he was in complete control.7

Competition from other promotional groups was not tolerated, especially if attempts were made to infringe on the TV money pie. Fighters who refused to give up control of their careers to the underworld bosses of the IBC were blacklisted from participation in lucrative television bouts.

On the local level, many independent promoters who operated neighborhood arenas that showcased up-and-coming talent found it impossible to compete with the sheer volume of free televised fights. For decades these venues had functioned as boxing’s farm system for developing new talent. Once there were more than 400 fight clubs in the United States. Many had been operating continuously since the early 1920s. The changing times and the advent of televised boxing decimated their ranks. By the late 1950s only a handful were left. Professional boxing has never fully recovered from this devastation of its traditional infrastructure.8

It wasn’t long before the dwindling supply of boxing talent could no longer keep up with the demands of the ravenous TV schedule. Many promising young fighters, fresh out of the prelim ranks, were rushed into televised main events only to have their careers short-circuited after taking a bad beating from a more-experienced opponent. Some became discouraged and quit; others continued, but were too damaged to ever achieve their full potential.

In 1954 the New York Times’s sports columnist Arthur Daley made the following observation: “It seems utterly ironical that there should be more fans and more interest in boxing than ever before in history while there is a shrinkage in sites, competitors, and caliber of performances.”9 Televised boxing, once seen as a savior for the sport, had now become a major force in its destabilization.

With most of the neighborhood fight clubs out of business, many established trainers and managers were finding it increasingly difficult to make a decent living. All but a few left the sport to either retire or find gainful employment elsewhere. Unfortunately, what they took with them was the knowledge and experience accumulated over decades. The loss of this irreplaceable resource created a disconnect in the passing of valuable lessons to a new generation of managers, trainers, and boxers.

The problems facing boxing were of no concern to the hoodlums running the IBC, who were still raking in the TV money. Eventually their brazen behavior caught up to them and brought about the organization’s destruction. In 1957 the Justice Department found the IBC in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act by engaging in a conspiracy to control world-championship boxing matches. Three years later Carbo and Palermo were convicted of extortion and menacing after trying to take control of welterweight champion Don Jordan. Both received lengthy prison terms.

The breakup of the IBC and the jailing of its criminal overlords was welcome news to everyone who had boxing’s best interests at heart. But tremendous damage had already been done. The overexposure of televised bouts and the lack of new and exciting stars of equivalent stature to replace the Old Guard had taken a heavy toll on the sport.

In 1962 boxing was down to just one nationally televised show per week. That year welterweight champion Benny “Kid” Paret suffered fatal injuries in a brutal knockout loss to Emile Griffith. The fight was telecast nationally. The tragedy no doubt contributed to the ABC network’s decision to cancel its Fight of the Week programming two years later. Boxing would not return to network television on a regular basis for another 12 years.

While all of this was happening, other major sports were moving inexorably forward. Professional basketball, which wasn’t even on the radar screen until the creation of the National Basketball Association in the late 1940s, was slowly but surely gaining in popularity. Professional football, barely noticed in previous decades, was about to begin its greatest era. Baseball also grew stronger in the postwar years. The national pastime not only retained its importance in popular culture, but also expanded its franchises to other cities in the 1950s and ’60s. Interest in professional hockey and tennis was also accelerating, and within a decade would reach unprecedented levels of popularity.

So while other professional sports reported steady growth in the decades following World War II, boxing took the opposite track by devolving and contracting in four major categories: public interest (number of fans); active participants (boxers); schools and performance sites (gyms and arenas); and qualified mentors (trainers and managers).

In his 1958 autobiography, 50 Years at Ringside, Nat Fleischer, the esteemed boxing historian and publisher of The Ring magazine, observed: “Prior to World War II the difficulty in ranking fighters lay in selecting 10 from an outstanding field of possibly 15 or more prominent performers. Today’s headache comes from trying to find a sufficient number of worthies in any division after the first three or four have been listed.”10

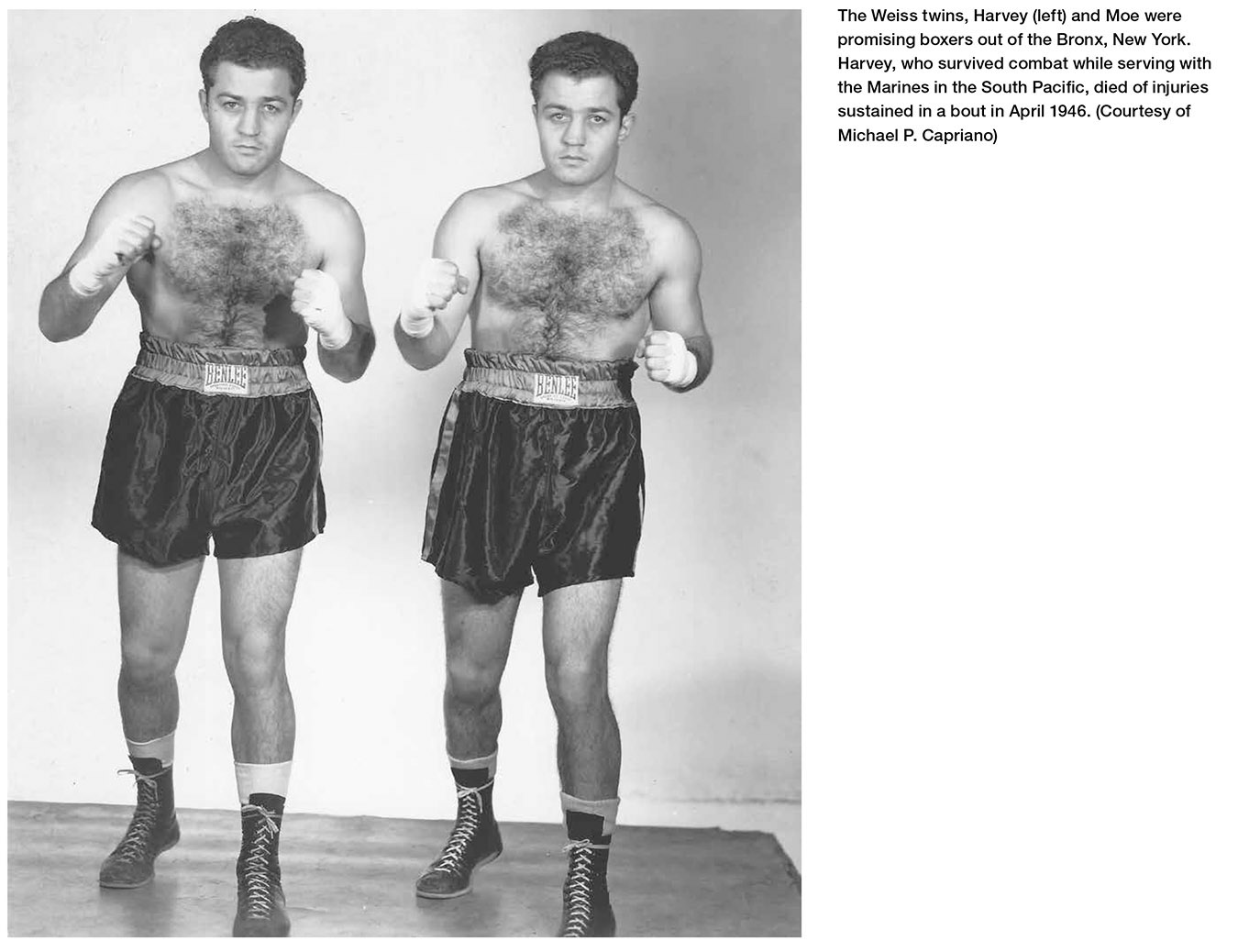

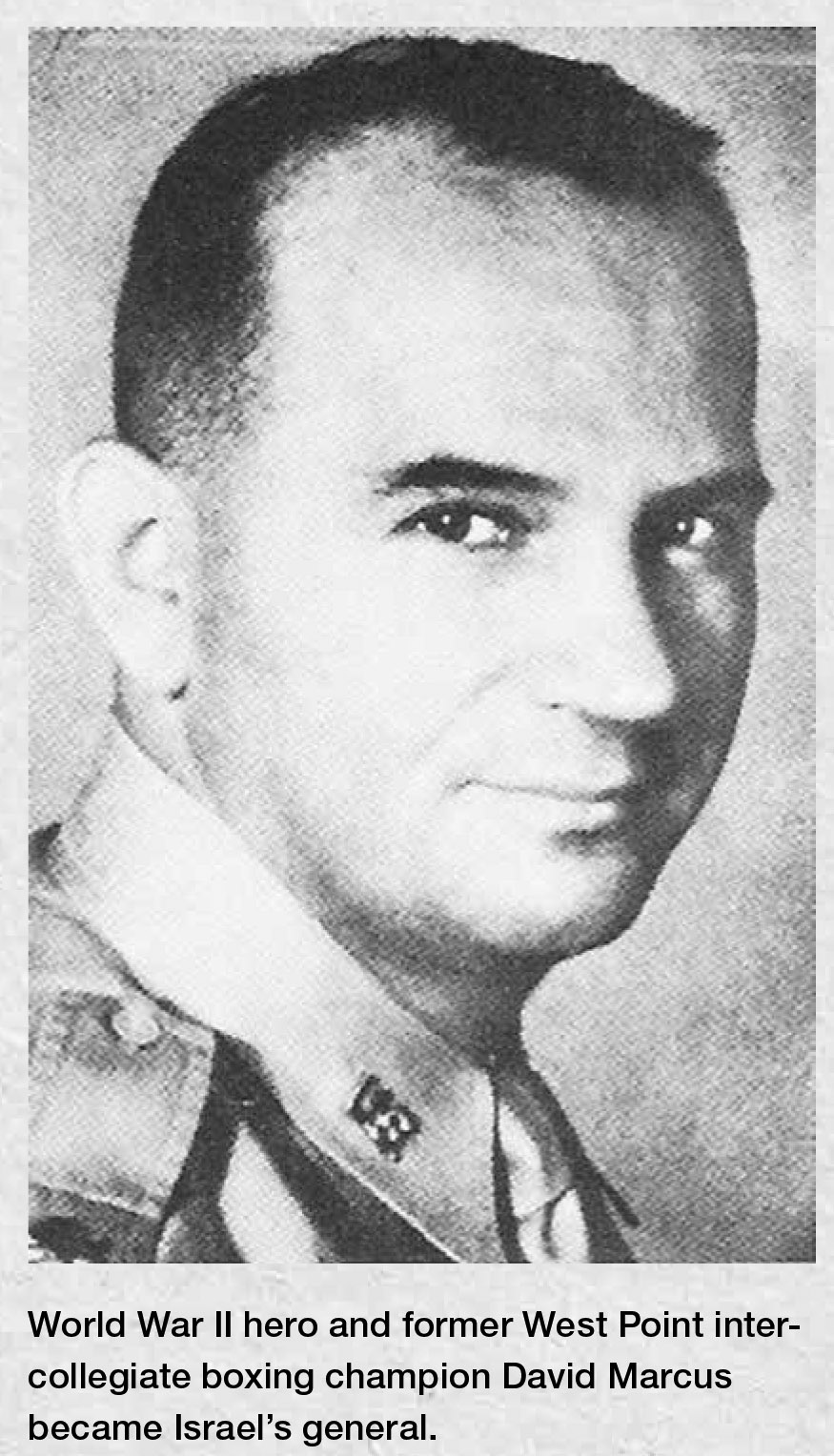

A generation earlier thousands of Jewish boxers from New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other major cities had inundated the sport. By the early 1950s the Lower East Side of Manhattan—the neighborhood that had once churned out more outstanding Jewish prizefighters than anywhere else on the planet— was down to its final few holdouts. Joey Varoff, Danny Bartfield, Henry Winchman, Hy Meltzer, Irving Palefsky, Harold (Izzy) Drucker, Leo Center, Artie Diamond, Leo Zipkin, Tony Arnold, and Joey Klein were among the last of a vanishing breed. Demographic changes affecting the Bronx also severely affected that borough’s output of Jewish boxers. Among the last of the Bronx battlers were welterweights Harvey and Moe Weiss, identical twins who had interrupted their promising boxing careers to volunteer for service with the Marine Corps during World War II. In a tragic irony, Harvey Weiss survived intense combat in the South Pacific only to die of injuries sustained in a boxing match less than a year after his return to civilian life.

Outside of New York City there was Detroit’s Allie Gronik, New Jersey’s Johnny Kamber, and an Israeli-born boxer named David Oved. All were solid main-bout boxers but not “top ten” title contenders. Overseas, the East End London boxing scene, a hotbed of activity before the war, was virtually bereft of Jewish boxers.

The last bastion of the Jewish prizefighter in America was Brownsville, Brooklyn—home to the venerable Beecher’s Gym. In 1925 the Jewish population of Brownsville and adjacent East New York neighborhood had increased to 285,521, making it the largest concentration of Jewish population in the city, exceeding the Lower East Side’s 264,178. Brownsville’s inhabitants had left the crowded streets of the East Side in search of cleaner, healthier, and more-spacious living.11

Brooklyn had scores of outstanding Jewish boxers in the 1920s and ’30s. Many received their undergraduate training at Beecher’s Gym. Among its honored alumni were Solly Krieger, Al “Bummy” Davis, Lew Feldman, Joey “Kid” Baker, “Schoolboy” Bernie Friedkin, Herbie Katz, Curley Nichols, Paul Klang, Marty Goldman, Izzy Redman, Lou Schwartz, and Yussel Goldstein.

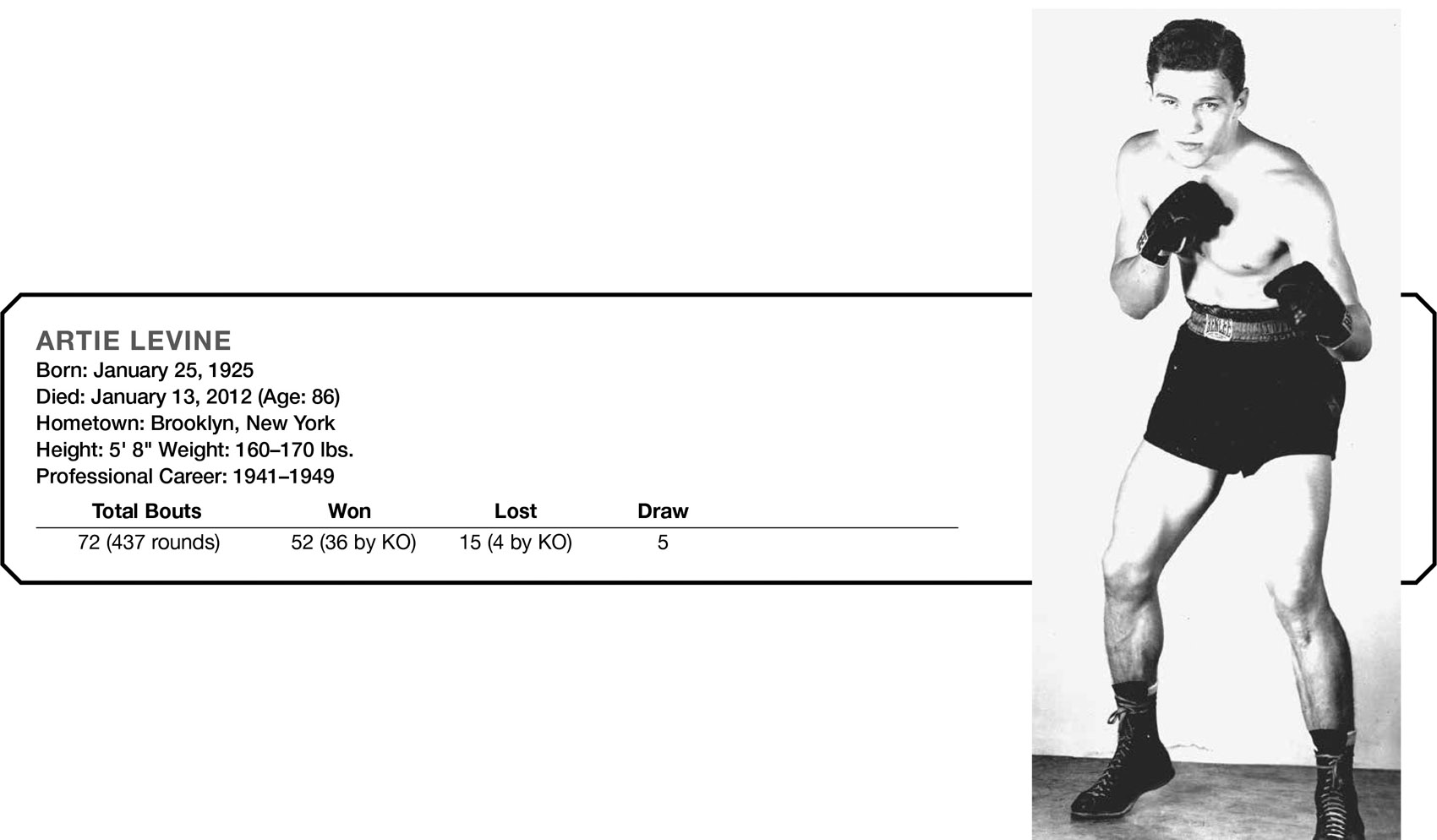

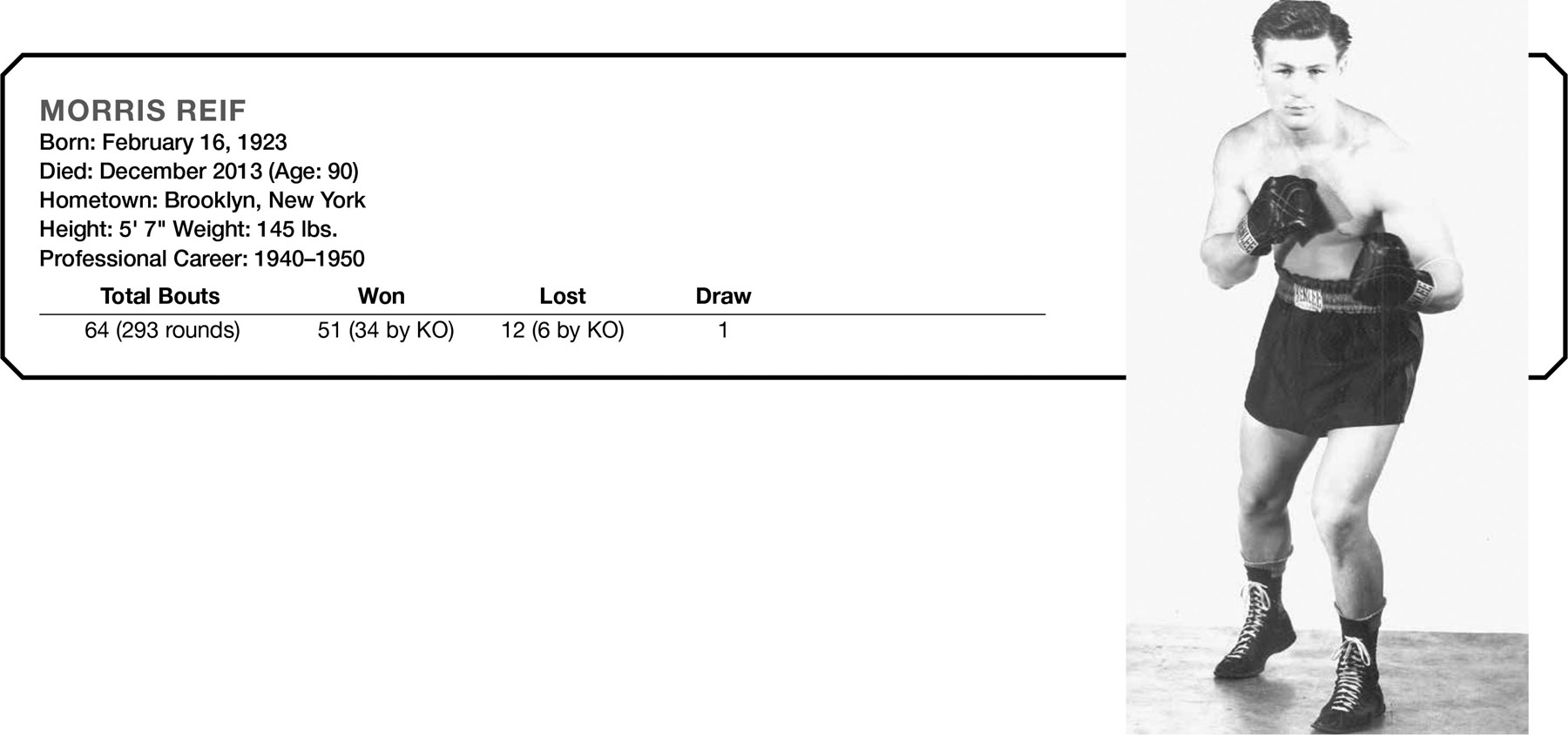

The mean streets of Brownsville, once home turf for the Jewish troops of gangland’s “Murder, Inc.” hit squad, were still capable of producing good Jewish prizefighters into the late 1940s. Harold Green, Artie Levine, Herbie Kronowitz, Morris Reif, Georgie Small, and Ruby Kessler headlined at Madison Square Garden. Other postwar main-bout Brooklyn bruisers included Julie Bort, Harry Diduck, Milt Kessler, Davey Feld, George Kaplan, Irwin Kaye Kaplan, Marvin Dick, and Sid Haber.

Beecher’s Gym changed ownership several times during the 1950s. It closed in 1962. Within one year boxing had lost three of its most important monuments to the Golden Age of boxing—Stillman’s Gym, St. Nick’s Arena, and Beecher’s Gym. Plans were already in progress to tear down Madison Square Garden III and replace it with another arena 17 blocks south, above the old Pennsylvania Station at 33rd Street and 8th Avenue.

The contenders and champions featured in this section represent the last vestiges of the Golden Age of the Jewish boxer.

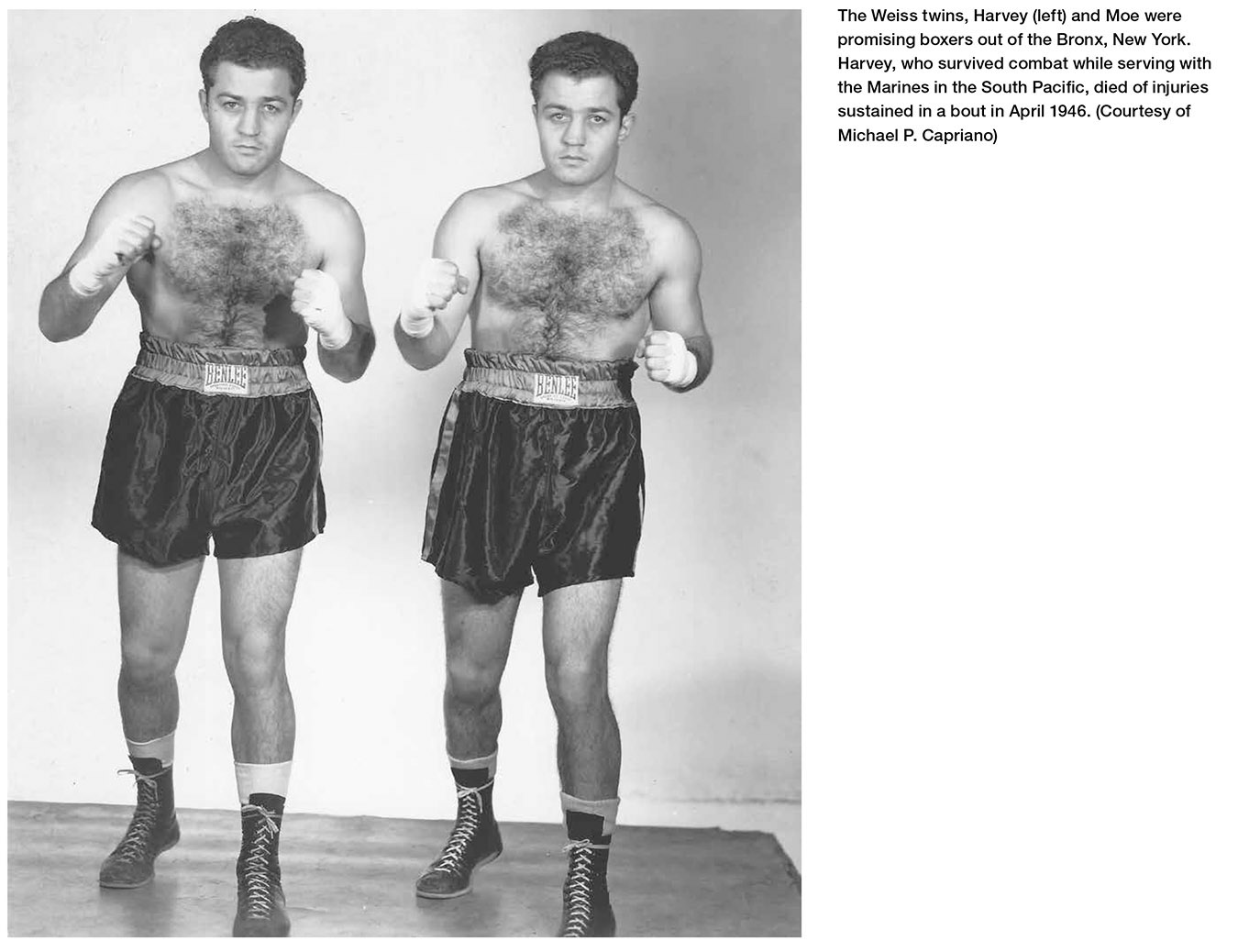

Danny Bartfield

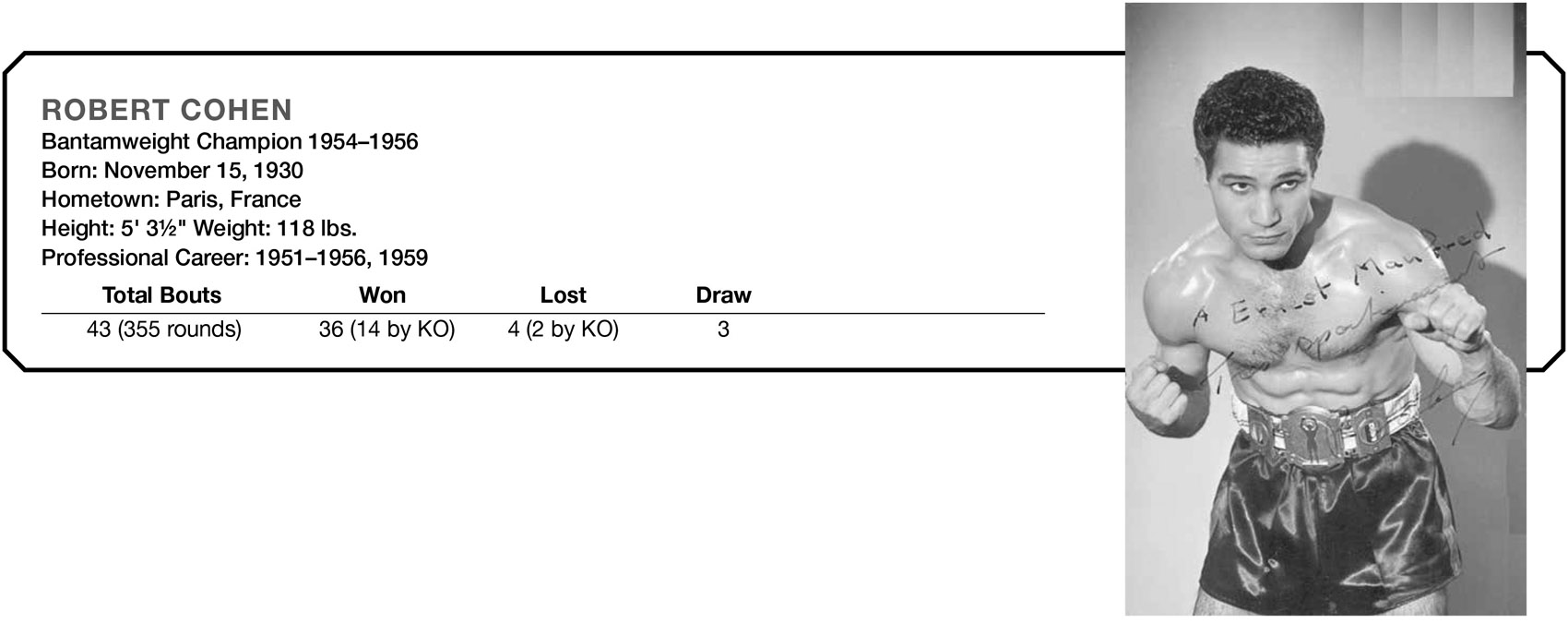

Robert Cohen*

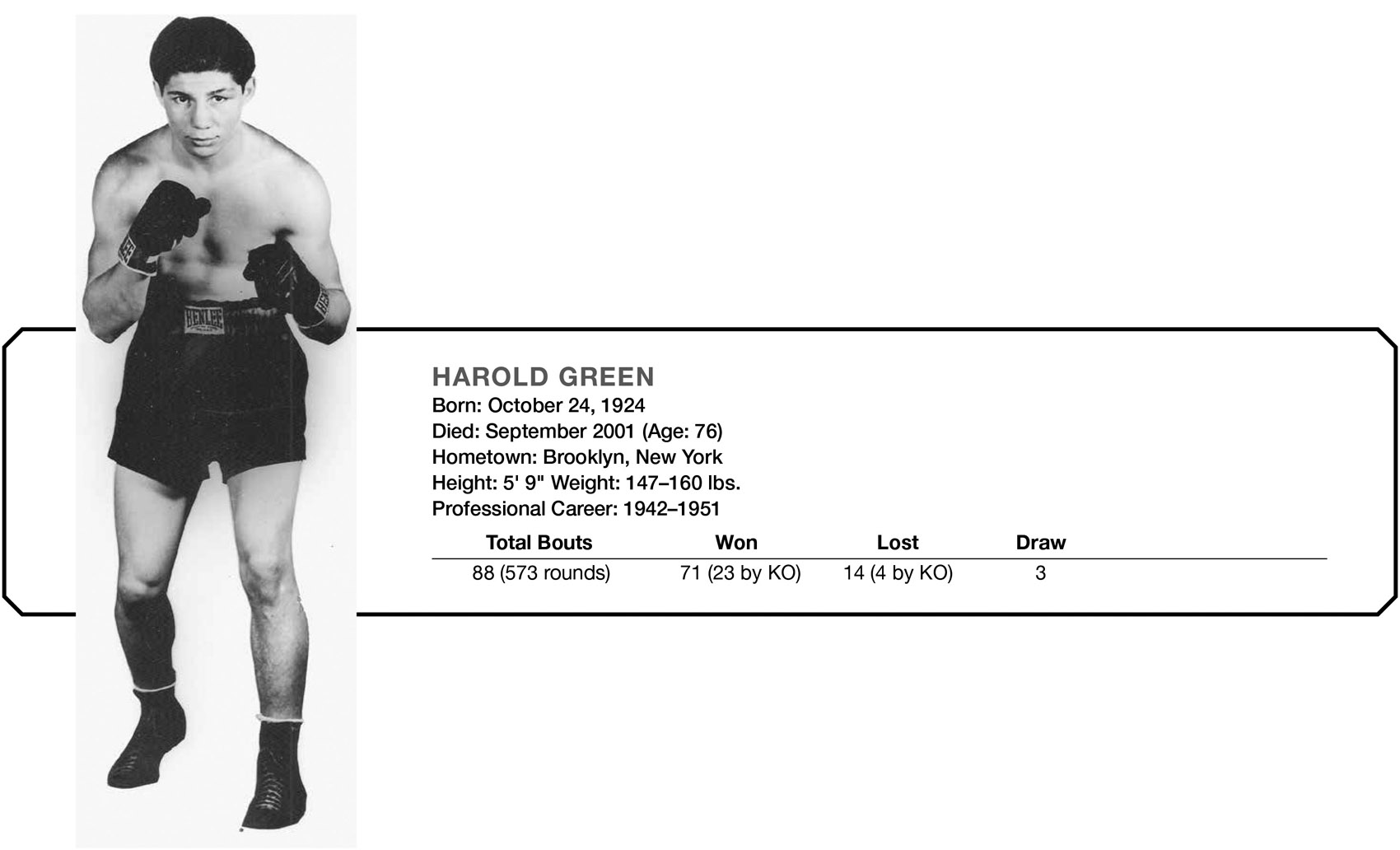

Harold Green

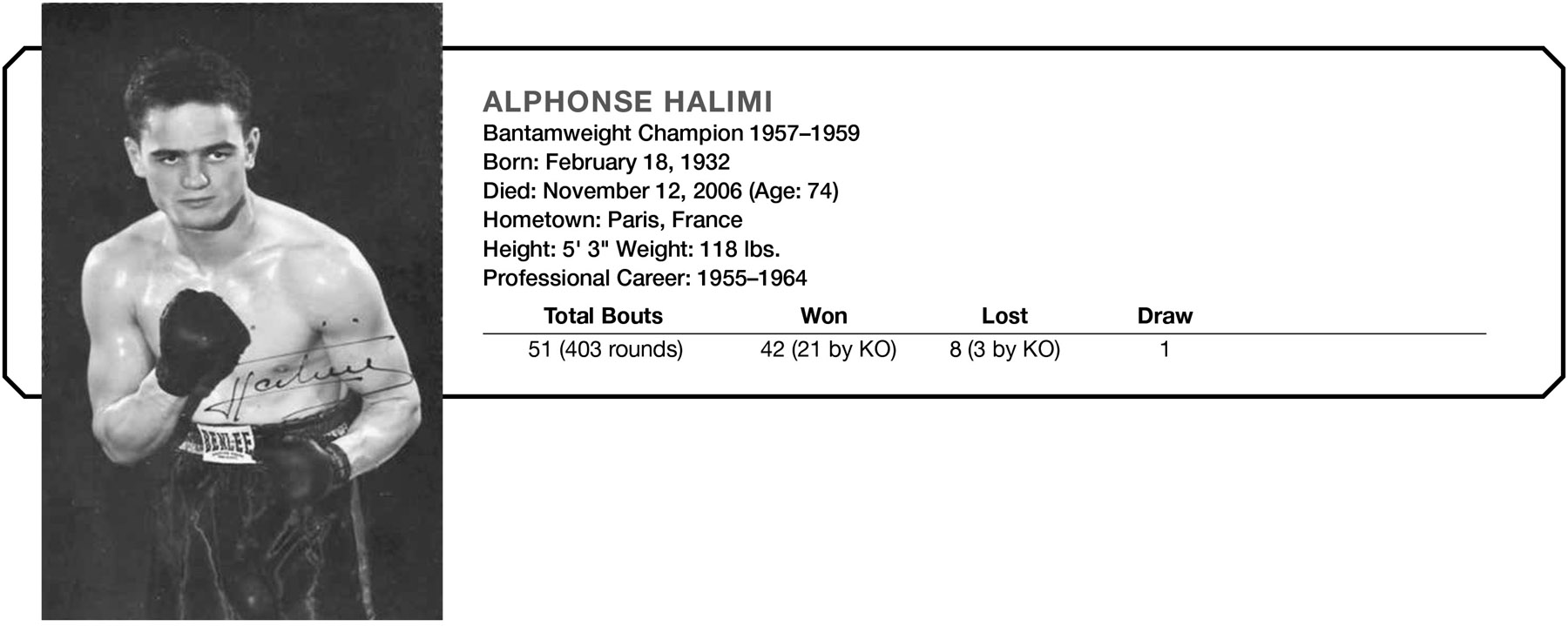

Alphonse Halimi*

Vic Herman

Danny Kapilow

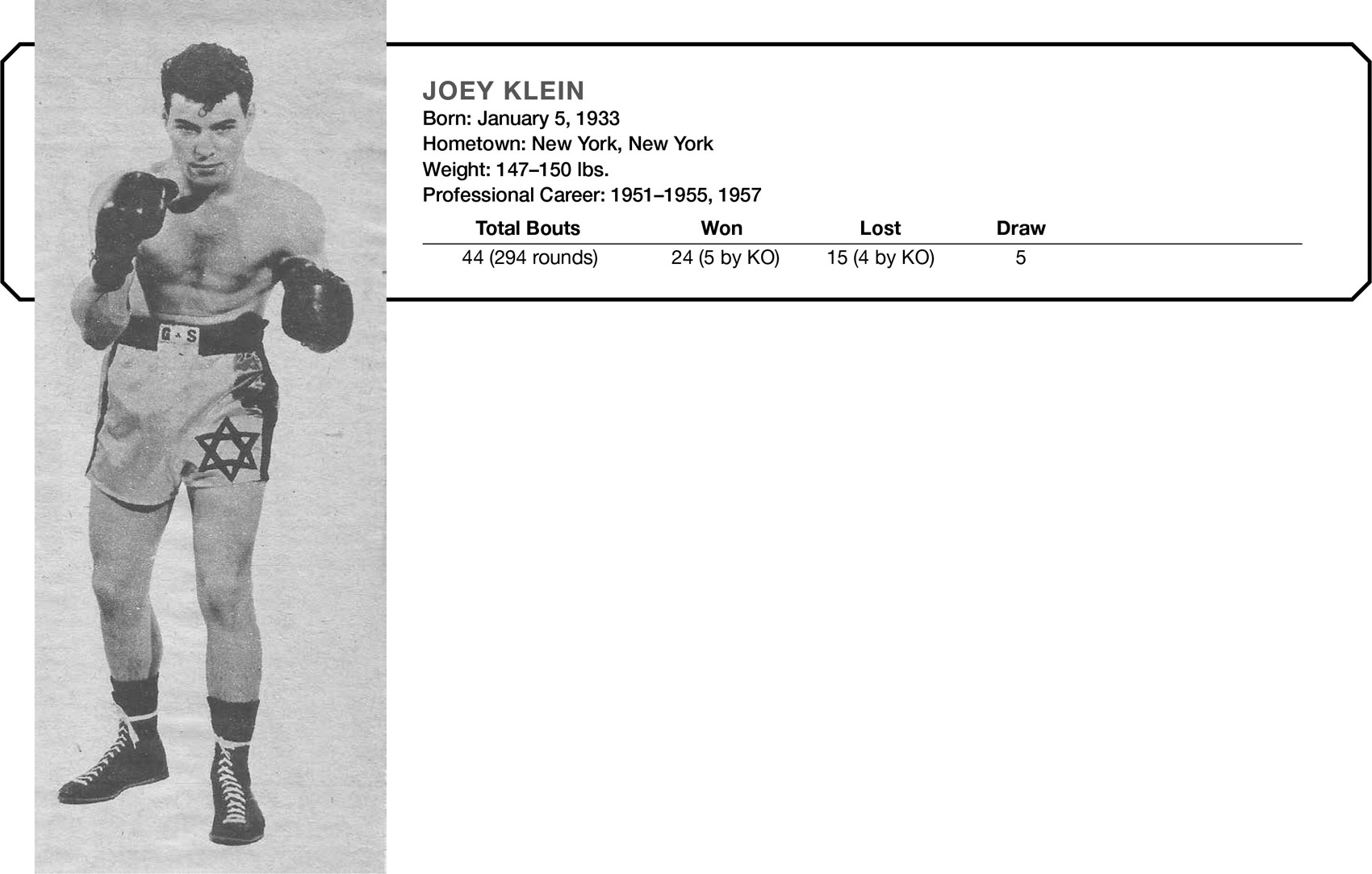

Joey Klein

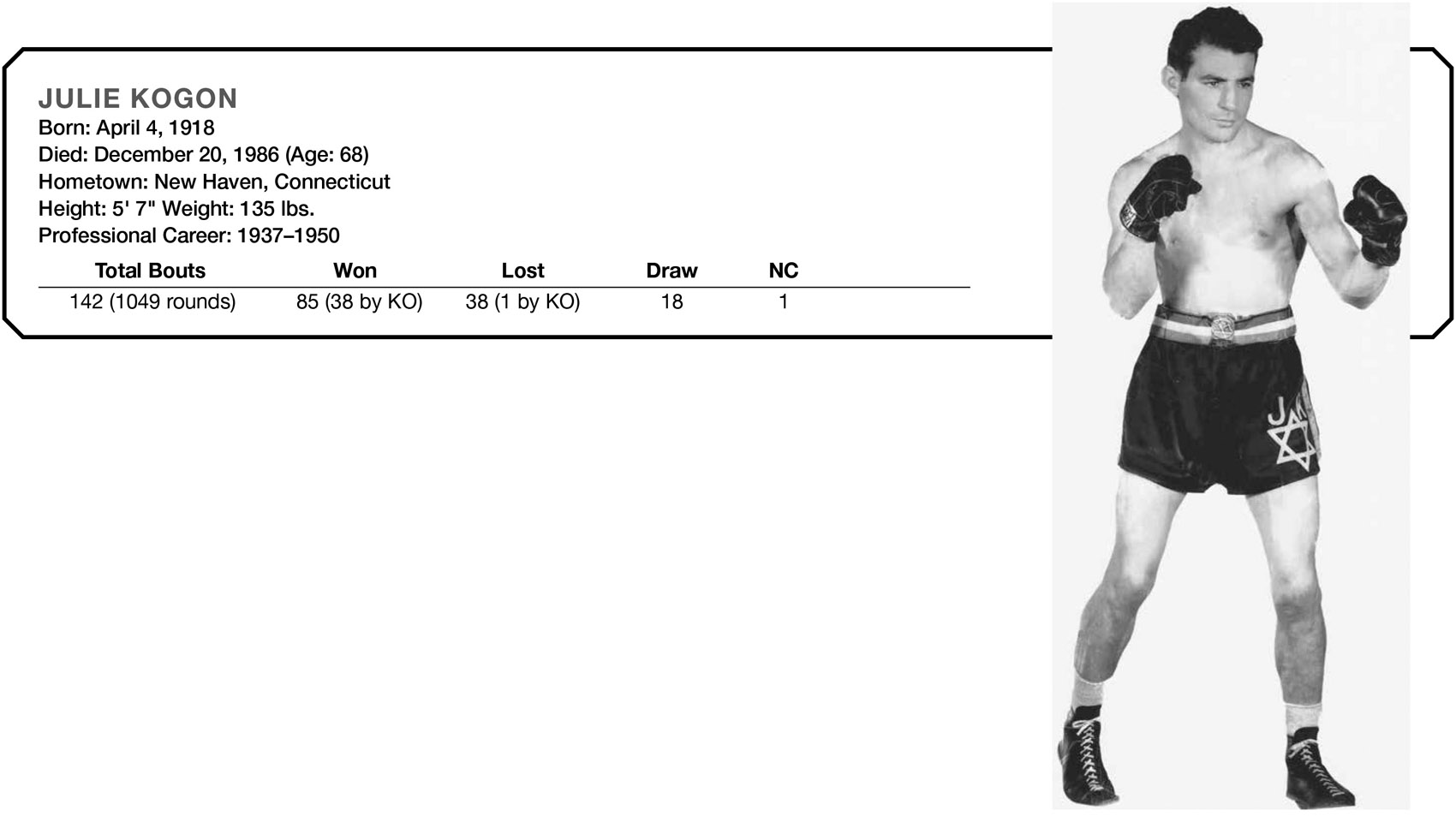

Julie Kogon

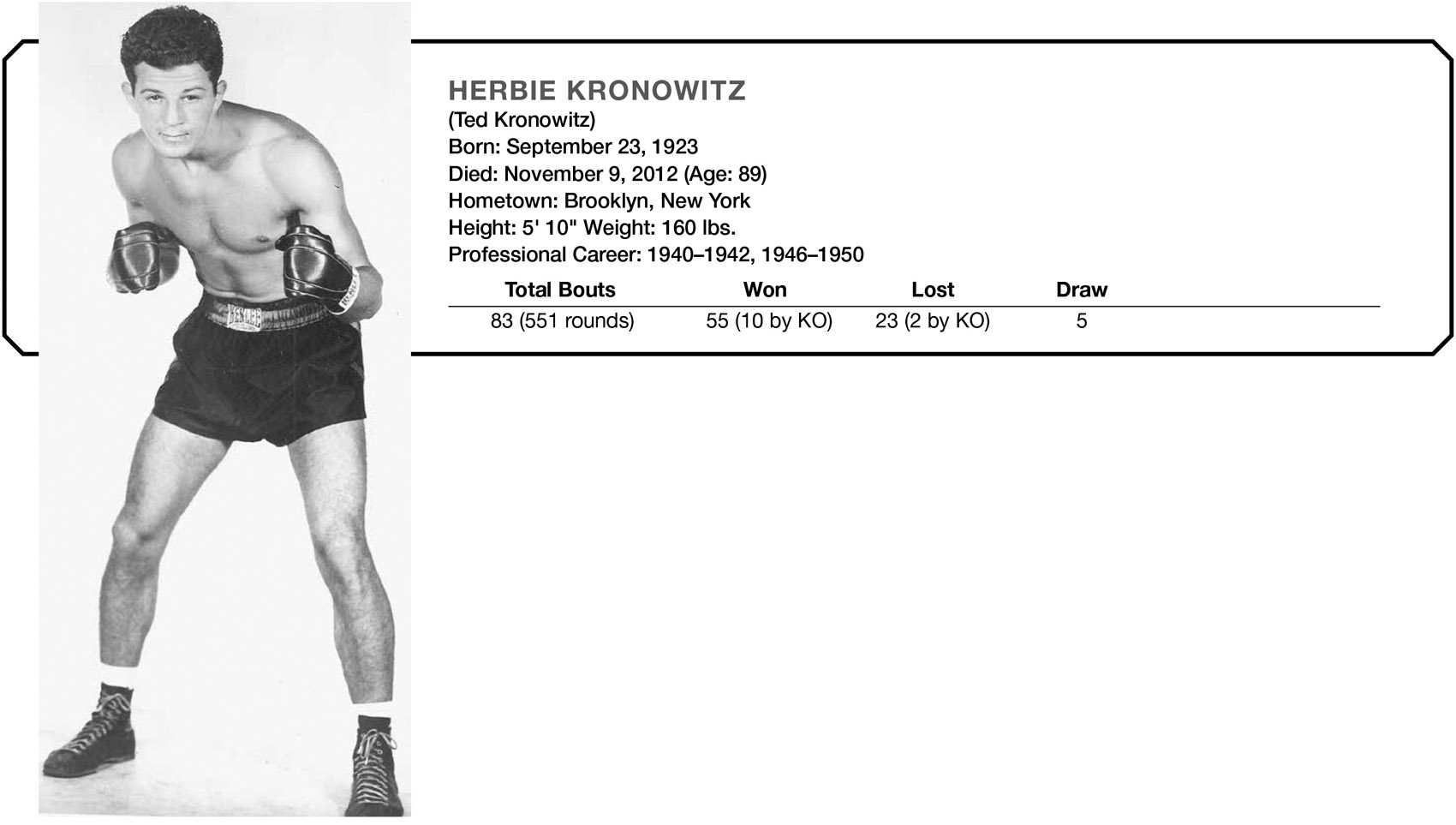

Herbie Kronowitz

Artie Levine

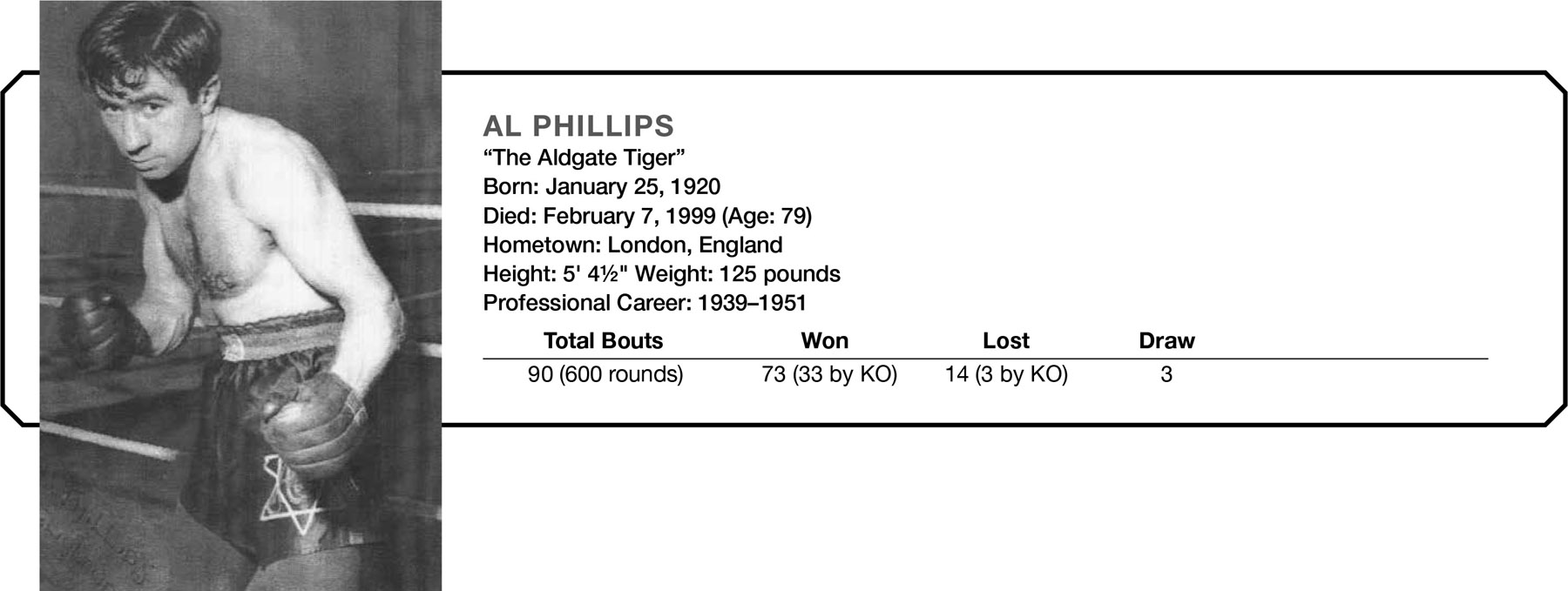

Al Phillips

Morris Reif

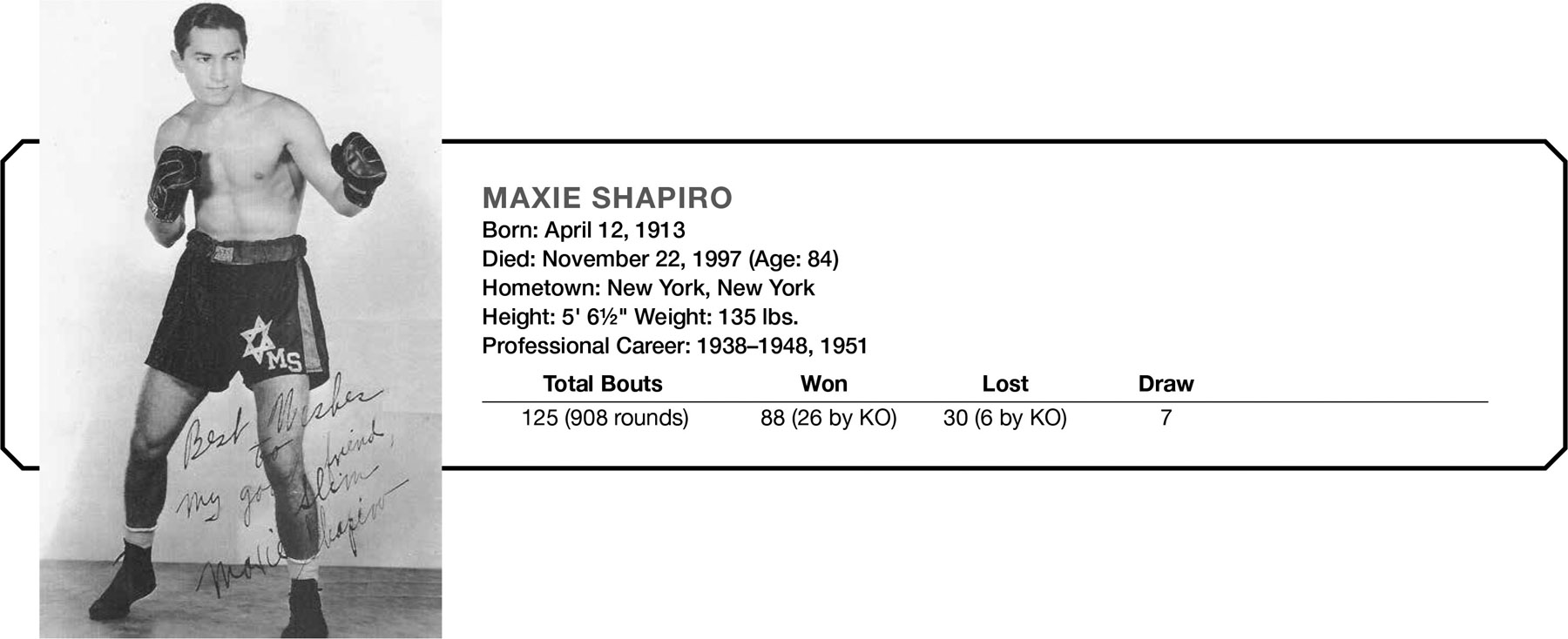

Maxie Shapiro

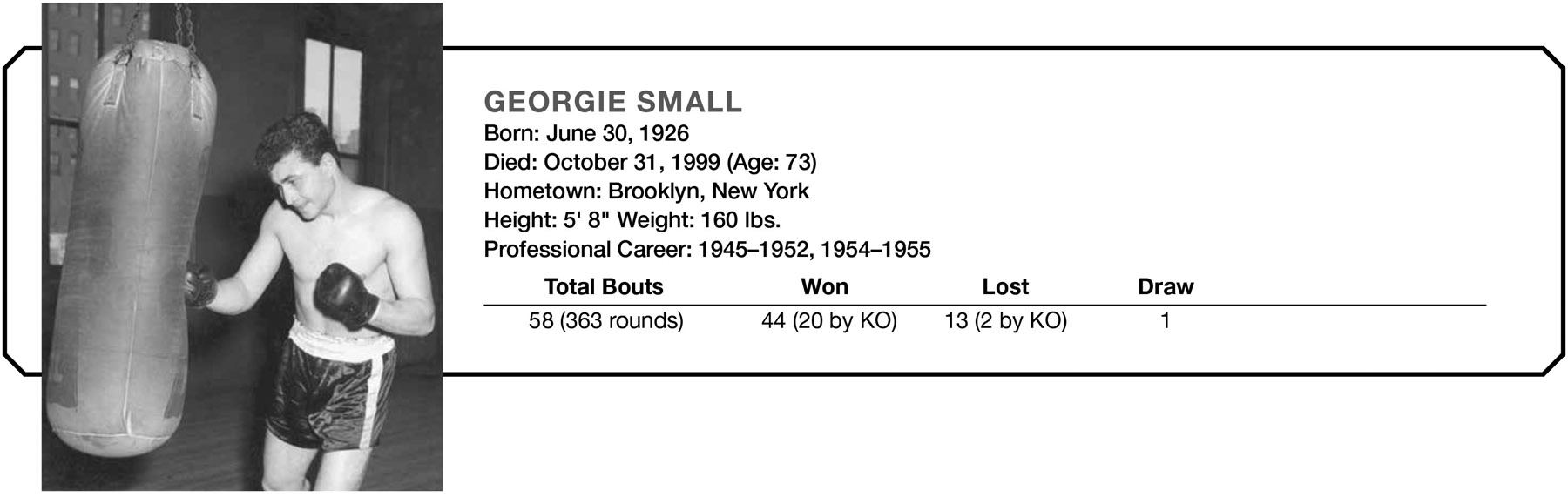

Georgie Small

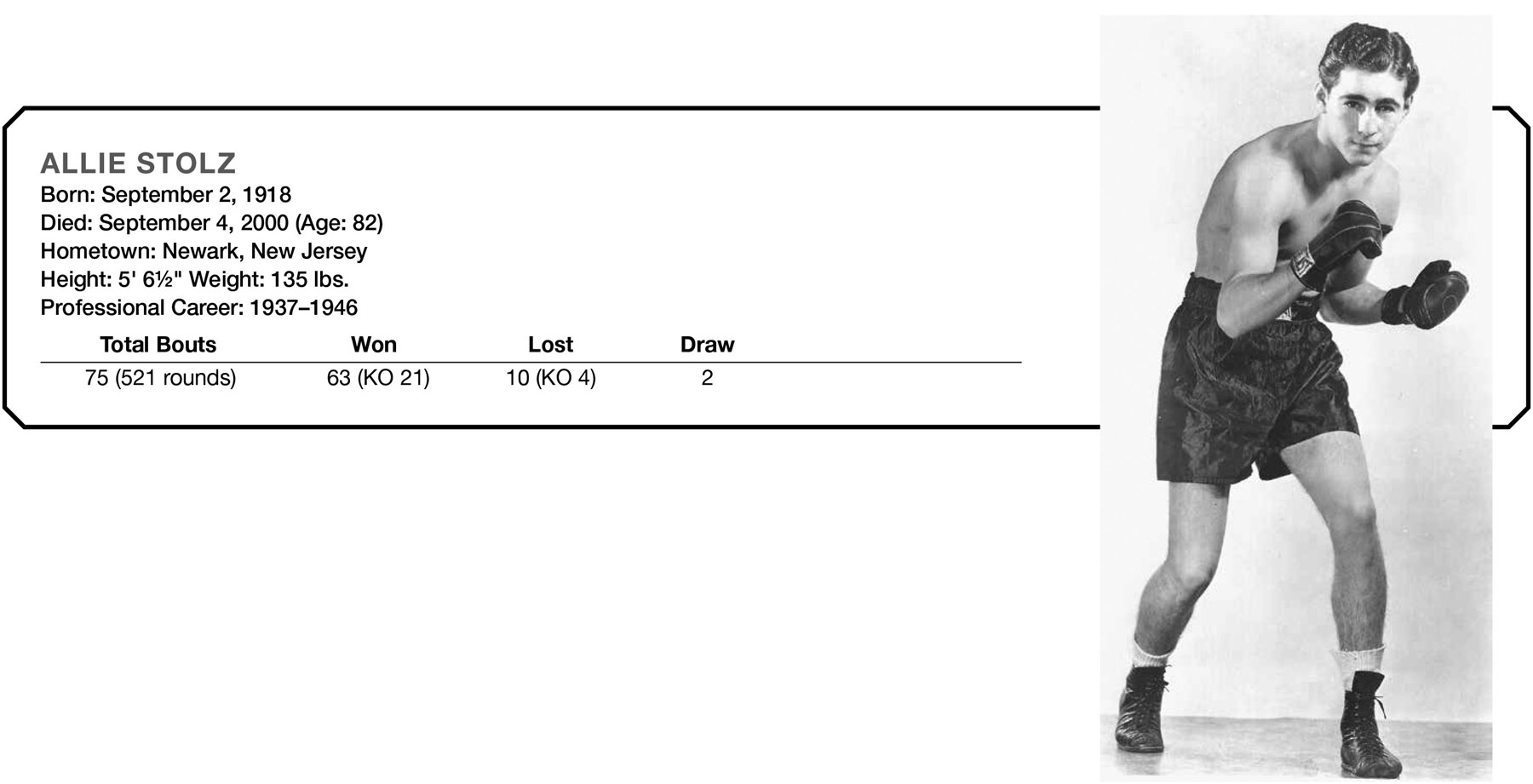

Allie Stolz

* world champion

Danny Bartfield’s uncle was the great Jacob “Soldier” Bartfield, a perennial welterweight contender of the early 1900s. Soldier’s nephew did not achieve the heights of his more-famous uncle, but he did manage to land three Madison Square Garden main events in the mid-1940s, and for eight months was rated by The Ring magazine among the top 10 lightweight challengers.

Bartfield won 36 of his first 38 pro fights, including two decisions over dangerous fringe contender Morris Reif. He was a good boxer but was plagued by hand injuries throughout his career. Bartfield broke his right hand in a Madison Square Garden bout against the brilliant welterweight Willie Joyce. The injury forced a two-year hiatus to allow his injured mitt to heal. He returned to the ring in 1947 and won five of six fights, losing only to future lightweight champion Paddy DeMarco.

Danny retired in 1948. For many years he was employed as a salesman for a liquor company. In the 1950s and ’60s he worked part-time as a referee for professional wrestling matches in New York.

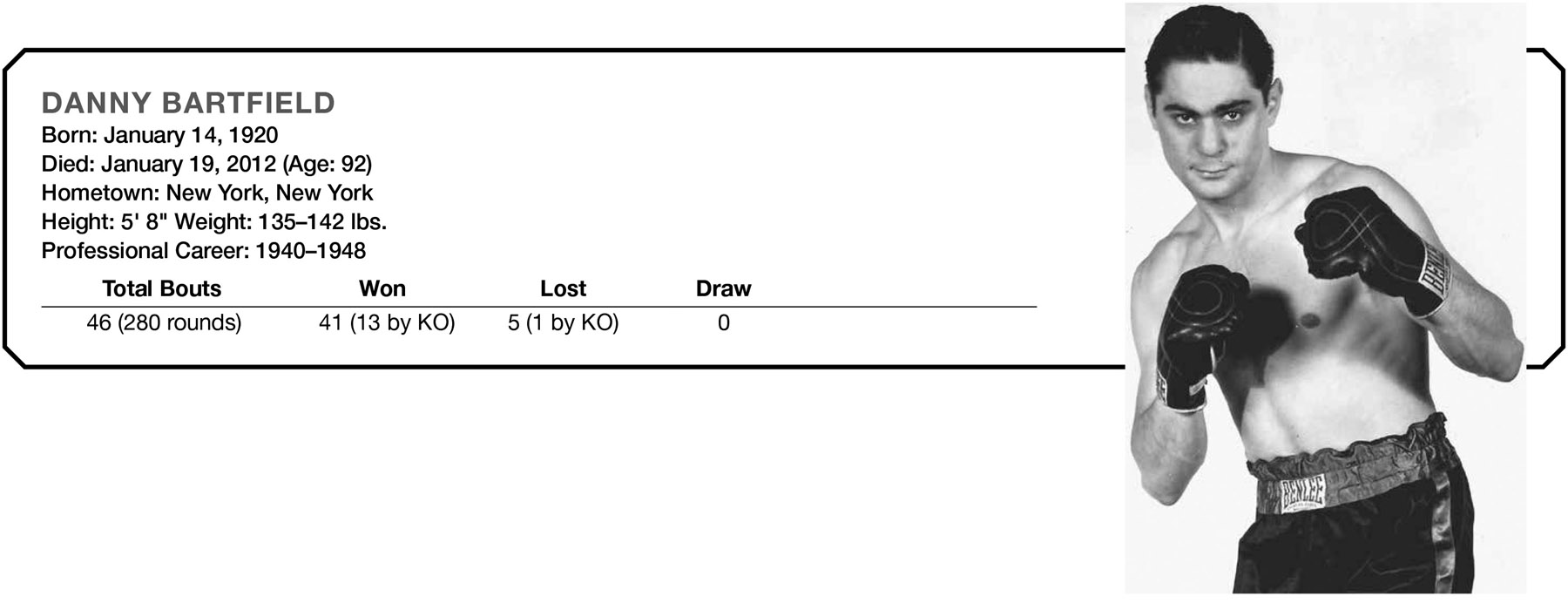

DAVID “MICKEY” MARCUS: A SOLDIER FOR ALL HUMANITY

The number of Jewish collegians who boxed is small, but one in particular stands out and deserves special mention. David “Mickey” Marcus was born on New York’s Lower East Side in 1902, the fifth child of poor Jewish immigrants from Romania. A top student and outstanding athlete while attending Boys High School in Brooklyn, Marcus was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1920. In his junior year he joined the West Point boxing team and won the intercollegiate championship. Graduating in 1924 at the top of his class, Marcus was offered a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University in England, but he declined the offer in order to be near his fiancée, Emma, whom he was soon to marry.12

After fulfilling his army commitment Marcus enrolled in law school, attending classes at night while holding down a full-time job during the day. Later he worked for the US Attorney General’s office and the New York City Department of Corrections. In 1940 Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed him commissioner of corrections.

When the United States entered World War II Marcus left his job and returned to the army as a lieutenant colonel. His first assignment was commander of the Ranger School in Oahu, Hawaii. In 1943 he was transferred to the European Theater, where he was appointed a divisional judge advocate. He volunteered to join the 101st Airborne Division assault force that parachuted into Normandy on D-Day, despite having no previous training as a paratrooper. His service earned him several major United States and British decorations, including the Bronze Star and Distinguished Service Medal.13

Marcus retired from the army in 1947 with the rank of colonel. A few months later he volunteered to help the new state of Israel defend itself against five invading Arab armies intent on annihilating the fledgling country. Marcus served as Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s personal military advisor during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. His tireless efforts included training recruits, organizing schools for officers, writing military manuals, and teaching the effective use of various types of armaments. Marcus was appointed the supreme commander of the Jerusalem front and was given the rank of alluf (the Hebrew term for “general”), thus becoming the first Jewish general in Israel in two thousand years.14

On June 10, 1948, a few hours before the ceasefire was to take effect, Marcus was tragically killed by friendly fire while inspecting the perimeter of his military headquarters in the village of Abu Ghosh. He was buried at West Point with full military honors. His gravestone at West Point reads: “Colonel David Marcus—A Soldier for All Humanity.” In 1966 actor Kirk Douglas produced and starred in Cast a Giant Shadow, a film based on the life of Mickey Marcus.

In 1951, the year Robert Cohen became a professional prizefighter, Algeria was home to approximately 140,000 Jews. Robert’s father, a barber in the port city of Bone, was an Orthodox Jew who obeyed the biblical commandment to be fruitful and multiply. By the time he finished fulfilling his duty, there were 10 additional Cohens, including Robert, the youngest.

When he was 14 years old, Robert was brought to a local boxing gym by an older brother and immediately became infatuated with the sport. His dedication matched his enthusiasm. Like all Algerian fighters he idolized the great French-Algerian middleweight champion Marcel Cerdan, who won the title from Tony Zale in 1948 and tragically died in a plane crash a year later.

The young fighter studiously copied Cerdan’s aggressive infighting style. With hands held high and elbows in close, Robert stepped in behind a hard left jab, slipping past punches to gain the inside position where he would belabor his opponents with combinations to body and head—just like Cerdan. It was a crowd-pleasing style that won the five-foot-three-and-a-half, 118-pound bantam an enthusiastic following.

After he won the Algerian amateur bantamweight championship, Robert moved to Paris and turned pro in 1951. Two years later he won both the French and European bantamweight championships. Among his victims were top-ranking contenders Theo Medina, Jean Sneyers, Henry “Pappy” Gault, and Mario D’Agata.

In keeping with his Orthodox upbringing Robert always found time to pray in the local synagogue and observe the strict dietary laws that required him to eat only kosher food, even when traveling to another country.

On September 19, 1954, in Bangkok’s National Stadium, before an audience of 70,000 that included the King and Queen of Thailand, Cohen challenged local hero Chamroen Songkitrat for the bantamweight championship of the world. Utilizing his greater experience, Cohen hammered out a close 15-round victory.

In 1956 Robert defended his title against Italy’s Mario D’Agata at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome. In the sixth round he was cut over his left eye. The referee ruled the cut too severe for him to continue and halted the bout. Mario D’Agata was declared the winner, becoming the first totally deaf person to win a world boxing title.

After the loss of his title Cohen had only one more fight and then retired. He moved to the Belgian Congo where he began working in his father-in-law’s textile business. Wanting to keep his hand in boxing, Cohen also opened a gymnasium. When the unstable political situation in the Congo became untenable, Robert and his wife moved to Cape Town, South Africa, where they have lived for the past 50 years.

Harold Green exchanged punches with four world champions, fought nine main events at Madison Square Garden, and was a top-10-rated contender in both the welterweight and middleweight divisions for nearly two years. The only losses he sustained in a career spanning 88 fights were to other world-class pros.

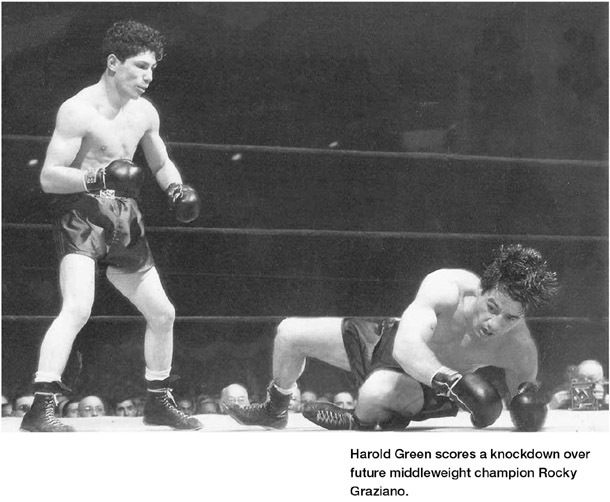

Harold came out of Brooklyn’s tough Brownsville neighborhood—home turf of the notorious Murder, Inc. gang, and fertile spawning ground for sluggers like Al “Bummy” Davis, Morris Reif, Georgie Small, and, more recently, Riddick Bowe, Mark Breland, and Mike Tyson. But unlike those power punchers, Green was an accomplished boxer as he proved by outpointing former welterweight champion Fritzie Zivic and future middleweight champion Rocky Graziano, twice.

His third match with Graziano, on September 28, 1945, nearly caused a riot in Madison Square Garden. Green was outboxing Rocky when he caught a right to the jaw in the third round and collapsed face-first to the canvas. As the count reached 10, he suddenly jumped to his feet and began arguing with referee Ruby Goldstein that he’d beaten the count. Goldstein ruled otherwise. Green then tore across the ring to get at Graziano and continue the fight. The 19,000 fans were in an uproar as handlers from both corners tried to keep the fighters apart. Order was finally restored when police entered the ring and escorted both fighters back to their dressing rooms. Green later apologized, but the New York Commission punished him with a year’s suspension.

The incident was a rare out-of-control moment for Green, who was usually a calm and collected ring technician. Years later he claimed in an interview with The Ring that mobsters had promised him a title shot if he threw the fight. Green told the interviewer that he had changed his mind at the last moment.

Harold returned to Madison Square Garden in 1947 and outpointed middleweight contender Pete Mead. Two months later he was back in the Garden to face future champion Marcel Cerdan, who stopped him in the second round.

In 1950, nearing the end of his career, Green knocked out 20-year-old Joey Giardello in the sixth round. Their rematch two years later resulted in a 10-round decision for Giardello. Harold retired after that fight. Giardello would eventually win the middleweight title in 1963.

After hanging up his gloves Green opened a marine equipment supply business in Brooklyn.

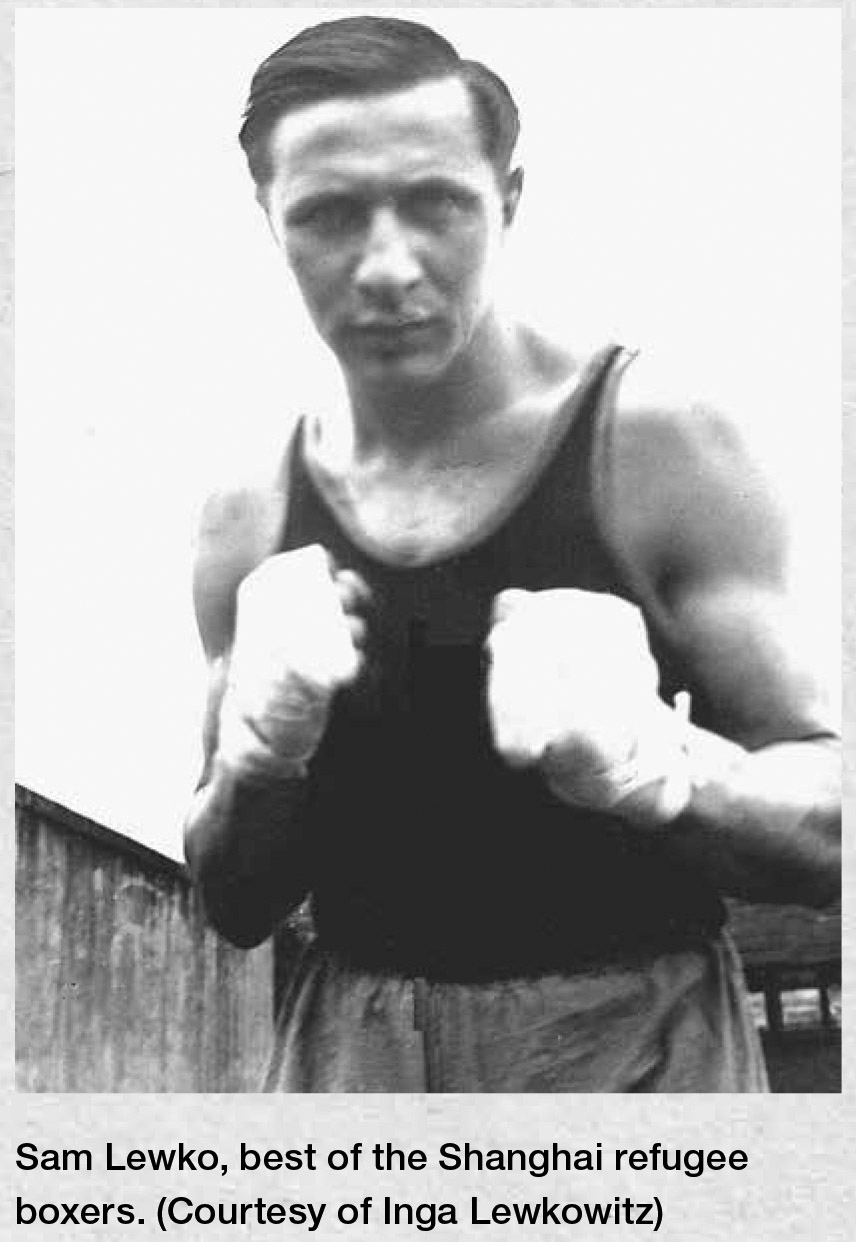

THE SHANGHAI GHETTO

In 1936 Chaim Weizmann, Zionist leader and statesman (and the future first president of the state of Israel) wrote, “The world seemed to be divided into two parts—those places where Jews could not live and those where they could not enter.”15 The previous year Nazi Germany had passed the infamous Nuremberg Laws that stripped Jews of citizenship, barred them from employment as doctors, lawyers, or journalists, and prohibited them from using state hospitals, public parks, libraries, and beaches. Hitler’s annexation of Austria in March 1938 brought an additional 185,000 Jews under Nazi control, and they too were expelled from all cultural, economic, and social life.

Amid the disaster that was unfolding, most of the world’s countries had shut their doors to Europe’s endangered Jewish population. One of the few places that remained open to Jewish refugees was Shanghai, a Chinese city under Japanese occupation. Between 1936 and 1941 an estimated 20,000 Jews from Germany and Austria found a safe haven in Shanghai. Most lived in the northeastern Hongkou district.

Although the occupation forces were in complete control, they did not molest Shanghai’s mixed European and Chinese population. No doubt the presence of the well-established International Settlements in Shanghai, which included many English, French, and American citizens, had prevented the type of mass slaughter by the Japanese military that took place one month later in the then Chinese capital of Nanking.

The Jewish community in Shanghai became remarkably self-sufficient. A variety of social networks were established that included synagogues, newspapers, aid programs, medical services, schools, and cultural activities. American-based Jewish philanthropic organizations, most notably the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), provided much-needed financial assistance through their representatives in Shanghai.

In a further effort to normalize their lives, the Jews of Shanghai formed athletic clubs. Sport competition was considered vital to the community’s well-being. Aside from keeping people occupied, the activities contributed to the health of the community and lifted the spirits of both spectators and participants. There was competition in soccer, boxing, field hockey, table tennis, handball, gymnastics, and chess. Many of the athletes, both men and women, had been members of Jewish sporting clubs during the interwar years in Europe. A good number were also involved with Betar, the militant Zionist organization begun by Ze’ev Jabotinsky prior to World War II. As such, athletic competition had a political purpose in preparing these young men and women for the fight to establish the Zionist dream of a Jewish homeland.16

Jewish boxers in Shanghai were among the city’s best. The first refugee matches were organized in July 1939 by Max Buchbaum, a refugee and former German amateur champion. The top refugee boxers were Sam Lewko (Lewkowitz), Eli “Kid” Ruckelstein, and Alfred “Laco” Kohn.17 Lewko and Ruckelstein were both experienced boxers. Kohn, a teenager, had never boxed, but under Buchbaum’s expert coaching, he would eventually develop into a formidable light-heavyweight boxer. (After the war Kohn emigrated to America, and in 1948 won a New York City Golden Gloves championship.) Sam Lewko had over 100 amateur bouts before coming to Shanghai, and was billed as the Maccabi champion of Berlin. That summer Lewko and Ruckelstein defeated the best of Shanghai’s Japanese, French, and American fighters. Jewish boxers trained at the American Marine Club and were very popular with all the nationalities inhabiting Shanghai’s International Settlements. Crowds numbering several thousand flocked to the stadium to see up to eight fights per night. Sam Lewko created a sensation when he knocked out a Japanese professional heavyweight brought especially from Tokyo to demonstrate the power of the nation of the conquerors.18

The outbreak of war between the United States and Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor made relief efforts more difficult. Food and medical supplies dwindled. Under pressure from its Nazi ally, the Japanese military governor passed a law confining Hongkou’s Jewish population to a “Restricted Area for Stateless Refugees.” In early 1943 the Japanese occupiers of Shanghai relocated the 23,000 Jewish immigrants to the poorest section of the city. Unsanitary living conditions and rampant undernourishment in the ghetto took a toll.19 Hundreds of refugees were at the point of starvation. Others died from typhoid, malaria, and other diseases.

Shanghai was liberated by Chinese forces on September 3, 1945. Over the next four years most of the refugees went to the United States, Israel, and Australia. By 1957 only 100 Jews remained in Shanghai.

Alphonse Halimi’s background was similar to that of bantamweight champion Robert Cohen. Like Cohen, Alphonse was born in Algeria to Orthodox Jewish parents and was the youngest of 13 siblings. Halimi also had a distinguished amateur career. Before turning pro in 1955, he fought 189 amateur bouts and was the French national bantamweight champion three years in a row. He always fought with a Star of David sewn onto his boxing trunks.

Halimi’s ascent in the professional ranks was meteoric. He won his first seven fights by knockout, five in the first round. In his 11th pro fight, he won an upset 10-round decision over the highly ranked American contender Billy Peacock.

On April 1, 1957, in Paris, Halimi challenged world bantamweight champion Mario D’Agata. Many fans and sportswriters thought the undefeated challenger was not yet ready to take on the champion. Halimi had only had 18 pro fights. D’Agata, the only totally deaf person to ever win a world boxing title, had had almost three times as many fights, and had not lost in four years

Halimi upset the odds by outboxing D’Agata and won a unanimous 15-round decision. In less than three years, two Algerian Jewish fighters— Cohen and Halimi—had won the bantamweight championship.

On November 6, 1957, Halimi traveled to Los Angeles for a unification title bout with Raul “Raton” Macias of Mexico. Macias was recognized as champion by the National Boxing Association. New York, Britain, and the European boxing authorities recognized Halimi. The fight, staged in Wrigley Field before 20,000 spectators, went the full 15 rounds. Macias was one of the best bantamweights of the 1950s, but Halimi proved to be just a bit too versatile and ring-wise for the tough Mexican fighter, and won a split decision. The $50,000 purse for Halimi was the largest of his career up to that point. Upon his return to Paris, Halimi was awarded France’s Légion d’honneur by President Charles de Gaulle.

Over the next 17 months Halimi defeated six opponents in non-title fights. During that time another young Mexican fighter, Jose Becerra, was cutting a swath through the bantamweight division. An explosive puncher, Becerra had knocked out 37 opponents while losing only four of 68 fights. Halimi agreed to defend his title against Becerra on July 8, 1959. The 8–5 odds favored Halimi.

Their fight drew 15,000 fans to the Los Angeles Sports Arena. After seven rounds neither man had established a clear advantage. Two of the judges had the fight even up to that point. Then, midway through the eighth round, Becerra trapped the champion against the ropes and dropped him with a devastating left hook to his jaw. Halimi arose on unsteady legs at the count of four. A barrage of punches sent Halimi to the canvas again, but this time he failed to beat the count.

Seven months later Halimi returned to Los Angeles, hoping to take the crown back from the only fighter to have ever knocked him out. For eight rounds the 32,000 fans in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum saw Halimi skillfully outbox Becerra. All three officials had Halimi in the lead. Then the roof caved in. Halimi did not see the left hook that found his jaw in the ninth round. He struggled to get up but was unable to beat the referee’s count. It was a dramatic ending to what, up to then, had been a very competitive and interesting fight.

Halimi launched his comeback five months later. He won eight fights in a row, including a 15-round decision over Scotland’s Freddie Gilroy for the European bantamweight title. The following year, in London, he lost the title to England’s Johnny Caldwell. A rematch with Caldwell produced the same result.

On June 26, 1962, Halimi outpointed Italy’s Piero Rollo in 15 rounds to regain the European title. The bout has historic significance because it took place in Tel Aviv. It was the first professional boxing match ever held in the State of Israel.

Halimi retired in 1964. He settled in France, and after briefly managing a cafe in Paris, he was employed as a trainer by the French National Sports Institute. Alphonse was the seventh and last Jewish bantamweight champion, and a worthy successor to Harry Harris, Monte Attell, Abe Goldstein, Charley Phil Rosenberg, Pinky Silverberg, and Robert Cohen.

Vic Herman—boxer, artist, and bagpiper—was born in Manchester, England. While still a toddler his Russian immigrant father, a cabinetmaker, moved the family to Glasgow, Scotland. In his teenage years Vic pursued an amateur boxing career as a member of the Jewish Lads’ Brigade, a national Jewish youth organization based in the United Kingdom. Herman’s success as an amateur encouraged him to turn pro in 1947. Within a few years he achieved a top-10 rating in both the flyweight and bantamweight divisions. For a time he was ranked the number-two flyweight in the world by The Ring magazine. The boxing style of this powerfully built baby bull can best be described as relentlessly aggressive.

In 1951 Herman won a 12-round decision over Norman Tennant for the Scottish Area flyweight title. Five months later he attempted to add the British flyweight title to his laurels, but was outpointed over 15 rounds by London’s Terry Allen. Other highly rated opponents included Peter Keenan, Henry Carpenter, Norman Lewis, and Joe Cairney.

In 1953 Herman toured the Far East, where he lost a 10-round decision to bantamweight contender Chamroen Songkitrat in Bangkok, Thailand. Five weeks later, in Tokyo, Japan, flyweight champion Yoshio Shirai knocked him out in the 10th round of a non-title fight. It was his first and only knockout loss in 57 fights.

After two more fights Herman retired and, with his wife and two children, moved to New York’s Greenwich Village to devote the rest of his life to his first love—art. Over the next several decades Vic Herman, former world-class boxer, became a world-class artist. His paintings have been exhibited in galleries across America and Europe. But his early years as a struggling artist were very difficult, and eventually cost him his first marriage. After the divorce Vic moved to California, where his artistic career took off, thanks to the millionaire Daniel Solomon, who not only bought his early works but also ensured that around 100 of his paintings were exhibited and sold in American art galleries.20

Vic Herman, a renaissance man of many talents, was also an accomplished bagpipe player in his youth and on several occasions had entered the ring for a fight playing the pipes. After he returned to London in the late 1960s, he used the woodworking skills learned from his father to begin another career, as a bagpipe maker, while his services were still in demand as a portrait painter.

Danny Kapilow waited until after he’d graduated from New York’s James Madison High School before making his pro debut on January 7, 1941. Over the next 19 months he compiled an outstanding 29-2-3 record. Six months after America entered World War II Danny joined the US Coast Guard. He managed to squeeze in a few bouts during weekend furloughs, including a 10-round draw with future middleweight champion Rocky Graziano.

Danny was discharged from the Coast Guard in September 1945. One month later, on October 24, 1945, he lost an unpopular 10-round decision to former lightweight champion Sammy Angott. In follow-up bouts he knocked out welterweight contender Gene Burton in the first round, but lost another decision to Angott. Danny came back with an upset 10-round decision over Philadelphia’s Wesley Mouzon.

Two weeks after defeating Mouzon, on March 15, 1946, Danny appeared in Madison Square Garden against welterweight contender Willie Joyce, one of the finest boxers of his era. The 10,000 fans were treated to a superb boxing match between two clever exponents of the sweet science. The judges voted the 10-round bout a draw. Kapilow retained his high ranking with subsequent victories over Dorsey Lay and Aaron Perry.

Five months after their first meeting Kapilow fought a return bout with Willie Joyce at Madison Square Garden. Joyce was slightly better and copped the 10-round decision. Seventeen days later Danny was in Griffith Stadium, in Washington, DC, trading punches with former lightweight champion Beau Jack. After ten rounds of nonstop action the judges gave the decision to Beau.

Having fought 60 bouts in 67 months, Kapilow was due for some well-deserved R & R. He took the next six months off. In his return to the ring, on February 18, 1947, he faced future welterweight champion Johnny Bratton in that fighter’s hometown of Chicago. The flashy Bratton and the methodically proficient Kapilow delighted the audience in the Chicago Stadium with another example of classic boxing technique. In a fight that resembled a violent chess match Bratton was awarded a split 10-round decision.

In his last bout of 1947 he was outpointed by slick Gene Burton, the same fighter he’d knocked out two years earlier.

Danny considered hanging up his gloves. He was only a month shy of his 27th birthday, and had been lucky so far. Superb boxing skill had kept him from taking a sustained beating in the ring. But his well-connected manager, Al Weill, told him to reconsider, as he could guarantee a good payday if he agreed to take on welterweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson in a non-title bout.

Danny took about one minute to decide. He realized there was no chance that he could defeat the greatest fighter of all time. Also influencing his decision was the fact that he was about to be married. Danny retired and never regretted not fighting a prime Sugar Ray Robinson.

After hanging up his gloves he took a job with the Teamsters Union and eventually became the head of a local chapter. Kapilow was also very involved with veteran boxers’ associations. With his lifelong friend, Charley Gellman, an ex-fighter who was the director of two New York City hospitals, care was provided for many former professional fighters suffering from neurological impairment and other physical ailments. Danny was more fortunate than most other expros. He remained sharp and active into his early eighties.

BOXING IN THE DP CAMPS

Following the defeat of Germany in World War II, the homeless, tortured, and starved remnant of European Jewry that survived the slaughter of the Holocaust converged upon makeshift camps designated for “displaced persons” (DPs). The DP camps were administered by the US Army and were located in the American Zone of Occupation in southern Germany. Approximately 12 of these camps housed between 150,000 and 250,000 Jewish refugees. Most of the refugees were forced to remain in the DP camps on the “accursed German soil” for three years, until the doors to the future state of Israel, or the United States, became open to them.

In January 1946 representatives from the DP camps formed a committee to set up self-governing institutions. Financial support and medical care were provided by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), and several other Jewish relief organizations. The goal of the organizers was to revitalize political, religious, and cultural life in the DP camps. As part of the program the Association of Jewish Sports Clubs was created to set up tournaments in soccer, track and field, swimming, basketball, table tennis, volleyball, and boxing. It was hoped that sports could be one of the activities that would aid in the mental and physical recovery of the survivors.

By early 1947 the DP camps had 16,000 young Jewish athletes representing 105 different teams (including 20 teams that refused to engage in sports activities on the Sabbath). Most of the athletes had been members of Jewish sports clubs in their countries of origin before the war.

The various athletic events often drew hundreds—and sometimes thousands—of spectators. Although soccer was the most popular sport, organizers also encouraged participation in boxing. They were of the opinion that boxing might help to prepare young Jews for the impending battle for the future state of Israel. Indeed, many of the DP camp athletes would be at the forefront in the coming struggle to establish a Jewish homeland.21

The first championship tournament took place in Munich in January 1947. It included more than 50 Jewish boxers in every weight class. All of the boxers wore the Star of David on their shorts. Over 2000 spectators filled the arena, while hundreds more, unable to gain entry, waited outside. In attendance were many American military officers and officials of the various Jewish agencies. The tournament was filmed, and a Hebrew-language newsreel (with subtitles) of the event exists and can be viewed on the website of the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive.22

The moving opening ceremonies had an air of solemnity as the orchestra played “Hatikvah” and the American National Anthem. At the conclusion of the tournament the 16 champions were awarded specially designed silver cups. The runners-up received engraved certificates. As noted by author Phillip Grammes, the championships “meant a kind of return to normality after the long, dark years of the Holocaust.”23

Joey Klein has the distinction of being the last Jewish fighter out of the Lower East Side to appear on network TV. On February 7, 1955, Joey lost a unanimous 10-round decision to welterweight contender Chico Vejar at Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway Arena. The bout was televised over the old Dumont network.

Joey turned pro in January 1951, around the same time televised boxing was inundating the airwaves with fights nearly every night of the week. Within a few years television’s demand for new talent began to outrun the supply. Young boxers who showed any promise were rushed into televised main events. Joey had 42 bouts in four years, appearing in televised fights nine times, often against more-experienced opponents. In an earlier era he would have been matched more carefully and taken whatever time was necessary to develop his full potential. Klein scored impressive victories over Gerald Dreyer, Rocky Casillo, Freddie Herman, Vic Cardell, and Pat Manzi, but was outpointed by Tony Pellone, Al Andrews, Jed Black, Carmine Fiore, and Danny Giovanelli. Most were rising stars or experienced veterans.

After his loss to Vejar, Joey took a two-year hiatus from boxing. He returned for two more bouts in 1957 and then retired.

Julie Kogon (sometimes spelled Kogan) was a classic stand-up boxer with a style reminiscent of the great Benny Leonard. He also possessed a solid chin (only one KO loss in 142 bouts) and sufficient power to flatten 38 opponents. Throughout his career Julie proudly wore the Star of David on his trunks, with his initials “J.K.” imprinted above the star.

Before turning pro in 1937 Julie had compiled an outstanding 85-2 amateur record. Both Julie and his twin brother Harry were among the top amatuer boxers in Connecticut.

Julie was undefeated in his first 27 professional bouts. He quickly developed an enthusiastic fan base in his home state, appearing in New Haven rings 70 times, often in front of sold-out audiences. Julie won the New England lightweight championship in 1947, but never fought for the world title. Among his 142 opponents were five world champions: Petey Scalzo, Willie Pep, Bob Montgomery, Ike Williams, and Jimmy Carter. Julie defeated Scalzo but lost to the other four great fighters.

It is a testament to his fine defensive skills that despite an intense schedule, Kogon’s face was virtully unmarked. On those rare occassions when he was tagged Julie proved he could take a solid punch. The only knockout loss on his record—to future lightweight champion Jimmy Carter—occurred near the end of his career, in his 133rd professional fight.

Shortly before he retired Julie purchased a luncheonette in New Haven which he operated successfully for many years. After selling the luncheonette Julie worked as a salesman for a Ford dealership. The personable ex-fighter also coached for the Yale University Intramural Boxing program. In 2009 he was elected to the Connecticut Boxing Hall of Fame.

Herbie Kronowitz’s real first name is Ted. At the age of 17 he was too young to turn pro, so he borrowed his older brother Herbert’s birth certificate to obtain a professional boxing license. He managed to squeeze in 40 bouts over the next two and a half years before joining the US Coast Guard in 1943. A year later he was about to be transferred overseas for duty aboard a Coast Guard cutter when he received word that his brother Albert had been killed in the Battle of the Bulge. Since his other brother was serving with the army in the Pacific, Herbie was ordered stateside for the remainder of the war.

Kronowitz resumed his career in May of 1946, and over the next 22 months won ten of 11 bouts. He preferred to box at long range and utilize his fine left jab and mobile footwork to outmaneuver opponents, but if the situation called for it, he was more than willing to mix it up on the inside. Among the quality fighters listed on his record are Artie Levine, Harold Draw Green, Pete Mead, Joey De John, Rocky Castellani, Laverne Roach, Sonny Horne, Lee Sala, and Johnny Greco. Most of his losses were by split decision to good fighters. The Ring magazine ranked him number nine among the world’s top 10 middleweights for two months in 1947. That was no small accomplishment back when the middleweight ratings included the likes of Tony Zale, Jake LaMotta, Charley Burley, Bert Lytell, Marcel Cerdan, Steve Belloise, Rocky Graziano, and Artie Levine.

On March 7, 1947, Kronowitz fought Artie Levine in the last Madison Square Garden main event between two Jewish boxers. After 10 furious rounds Levine won a close but unanimous decision that was roundly booed by the crowd of 12,000 fans.

Three months later Herbie decisioned Harold Green for the “middleweight championship of Brooklyn.” The bout attracted 15,000 fans to Ebbets Field.

After hanging up his gloves in 1950, Herbie purchased two New York City taxi medallions. Countless times passengers would recognize his name on the license placard and ask if he was the same person they had seen fight.

The former contender never strayed far from his boxing roots. He became an active member of the Veteran Boxers’ Association and was a licensed referee on the staff of the New York State Athletic Commission from 1955 to 1984. Light on his feet, Herbie seemed to glide around the ring, a reminder of the excellent footwork of his ring days. He always put the safety of the boxers first, and was respected for his competence and impartiality.

Reflecting on the positive aspects of his boxing career Kronowitz told an interviewer: “The thing about boxing is that it gave every one of us everything we have. I don’t mean just money. It taught us how to live, how to act, how to eat, how to be physically fit. It opened doors to places that we never could have gotten into. Some made more money than others, but every boxer looks at his career as the most important experience in his life.”24

“I knew about Artie Levine,” said the former welterweight and middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson. “Six weeks before I outpointed Tommy Bell for the title I boxed Levine in Cleveland. He clipped me with a left hook to the jaw that flopped me like a fish in the fifth round, or so I’ve been told.”25 That quote appeared in Sugar Ray Robinson’s 1970 biography. The great fighter staggered to his feet at the count of nine. He fought on pure instinct for the next two rounds. Robinson did not fully recover his senses until the eighth round. The terrific battle ended when Robinson, fighting desperately, knocked Levine out with only 19 seconds left in the 10th round.

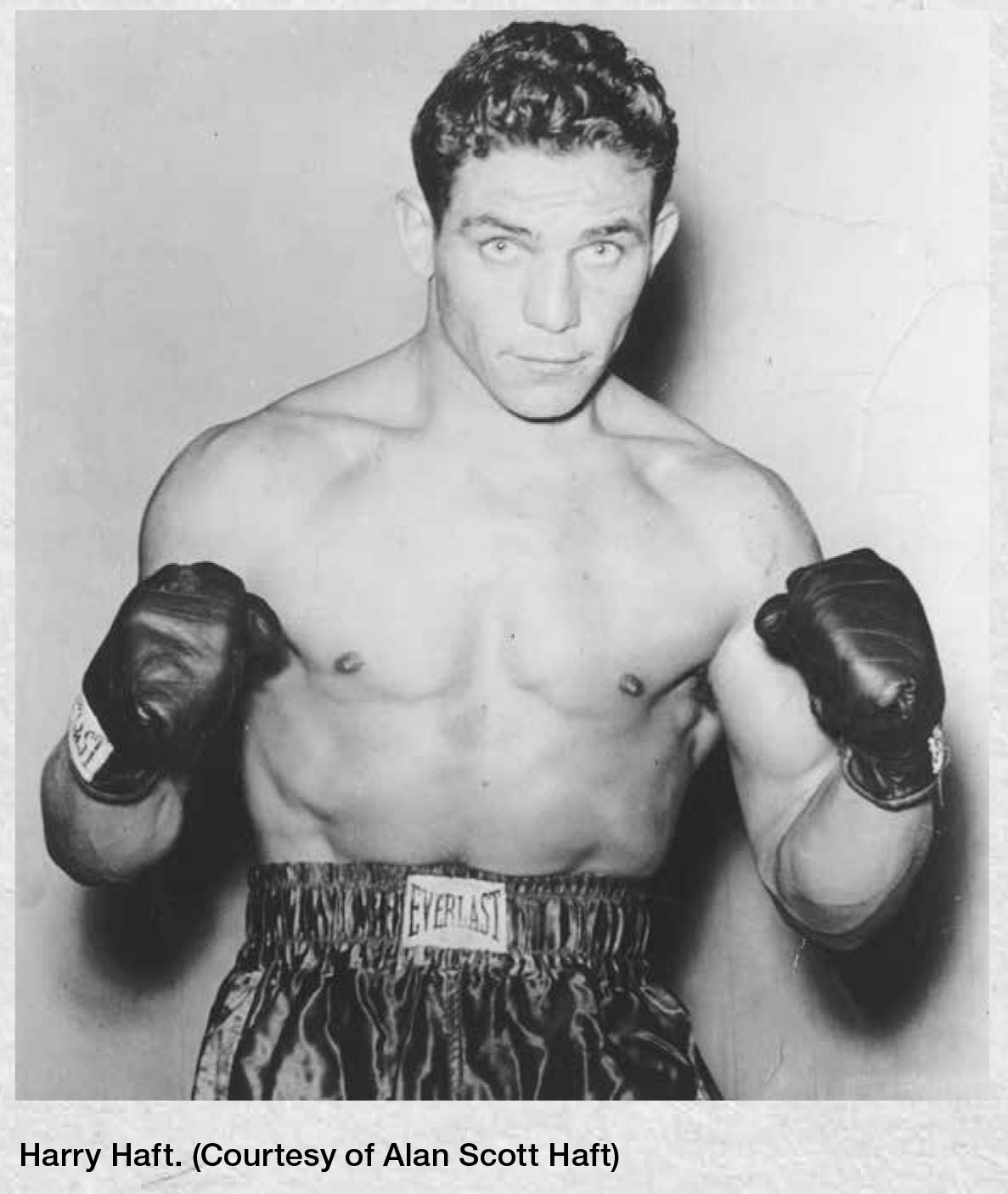

THE HARRY HAFT STORY

During World War II the average life span of a prisoner in a Nazi slave labor camp was measured in weeks. Inmates succumbed to disease, starvation, hard labor, and the brutality of the guards. In 1943, Harry (Herschel) Haft, an 18 year-old Polish Jew, was imprisoned at the Jaworzno slave labor camp in Poland. Jaworzno was one of the many sub-camps of Auschwitz providing forced labor for the German war industry. Before his arrival in Jaworzno Harry had been interned at four other slave labor camps where he was beaten and starved, yet the Germans could not destroy his will to survive.

Haft was among a group of prisoners forced to fight other Jewish inmates in bare-knuckle brawls for the perverse entertainment of SS officers who placed bets. The bouts ended when one man could no longer stand on his feet. Harry fought 75 bare-knuckle fights to a finish. At the end of every match he was the only one left standing.

With the approach of the Soviet Army, the Germans evacuated the camp at Jaworzno and fled westward, taking the camp’s prisoners with them. The death march back to Germany lasted for weeks. Of the several thousand Jews who left Jaworzno, only about 200 men made it to a train station where the soldiers loaded them into a single boxcar. Several days later the train arrived in Germany. When the doors were opened, only 30 men were still alive.

Harry and a friend made a break and dashed into the forest, hoping to escape. The guards opened up with machine guns. His friend was hit and fell forward into a ditch. Harry jumped in beside him. As guards approached the ditch, he heard one tell the other, “Don’t waste any more bullets; they’re already dead.”

Haft waited until he was sure the guards had left before crawling out of the ditch. Wandering in the Bohemian forest, he saw an SS uniform hanging on a branch. A German soldier was bathing in a river. His handgun and rifle lay between the boots. Harry grabbed the rifle, aimed and fired. The shot missed and the soldier came running toward him. Harry reached for the handgun and emptied the contents of the chamber into his target. Blind with rage, he then battered the dead man’s skull with the butt of the rifle.

Harry removed his bloody clothing and put on the uniform, which hung loosely on his 110-pound frame. Later he approached a farmhouse where an elderly German couple, thinking he was a German soldier, allowed him into their home and gave him food, but the husband became suspicious and kept badgering him with questions. Fearing they had seen through his disguise, Harry drew his weapon and shot them both. He continued hiding in the forest until the war’s end.

In 1945 he joined other Jewish survivors in a Displaced Persons (DP) camp run by the US Army. There he made contact with relatives who told him what they knew about his family’s fate. Two brothers had vanished and were believed to have been killed while fighting with partisans. A third brother was drafted into the Russian army and had risen to the rank of colonel, but was killed in the Battle of Berlin. Harry’s mother and his two sisters were murdered in the Treblinka death camp.

In an effort to help rehabilitate the survivors, various programs were arranged at the DP camp. One of the activities organized by the American servicemen was a Jewish boxing championship. By the time Harry decided to enter the tournament in January 1947, he had put on 50 pounds and resembled the strapping youth he was before his nightmare began. Harry won the Amateur Jewish Heavyweight Championship and was named the outstanding boxer in the tournament. He was awarded a trophy by an American general.

In 1948 Harry emigrated to the United States, where he was taken in by an uncle. He then embarked on a brief professional boxing career that included bouts with unbeaten Roland LaStarza and future heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano. Harry retired after losing to Marciano on a third-round TKO. His professional record was 13-8, with 8 knockouts.

Harry eventually married and raised a family, but he was haunted by his wartime experiences for the rest of his life. When asked why he chose to become a professional boxer after all the physical abuse and torture he had endured in the concentration camps, he would answer, “After all I have been through, what harm could a man with gloves on his hands do to me?”

Harry’s son, Alan Haft, authored a riveting biography of his father’s life, entitled Harry Haft: Survivor of Auschwitz, Challenger of Rocky Marciano.26

Robinson often said that Artie Levine hit him with the hardest punch of his 202-bout career. In 2000 the Cleveland Plain Dealer named the Robinson vs. Levine fight the most exciting in the city’s history.

Levine’s 50 percent KO ratio was among the highest in the middleweight division. But he wasn’t just a slugger. He was also an excellent boxer, which made him even more dangerous. Artie was always looking to create an opening for his murderous left hook.

In the late 1940s Levine earned a top-10 rating in both the middleweight and light-heavyweight divisions. His best wins were over Sonny Horne, Jimmy Doyle, Vic Dellicurti, Billy Walker, and Herbie Kronowitz. All except Kronowitz were KO victims.

Artie retired in 1949 following consecutive losses to Chuck Hunter and Dick Wagner. He was only 24. Artie had become dissillusioned with boxing. He felt abused and disgusted by the criminal element that had taken over management of his career. He wisely decided it was time to hang up his gloves. Always smart and ambitious, Artie became a successful sales manager at one of the largest car dealerships in the country.

For 44 months, between 1943 and 1951, London’s Al Phillips was rated among the top 10 featherweight contenders by The Ring magazine. As his nickname “The Aldgate Tiger” implied, Phillips was an all-action, two-fisted pressure fighter with a hefty wallop. Slick stylists gave him the most trouble. Liverpool’s great master boxer Nel Tarleton was one such opponent. Tarleton survived some rough moments to outpoint Phillips in a bout for the British Empire featherweight title in 1945.

Over the next two years Phillips won 14 of 16 bouts, culminating with a 15-round decision over Cliff Anderson for the vacant Empire and British featherweight titles. Six weeks later, on May 27, 1947, he added the European featherweight championship to his collection after his opponent, Ray Famechon, was disqualified in the eighth round. Just one month later he lost all three titles when outpointed by Ronnie Clayton over 15 rounds.

In the final months of his career Phillips outpointed Clayton in a non-title 10-rounder, but lost the 15-round rubber match.

After he retired Phillips became a successful matchmaker and promoter in England.

Morris Reif turned pro in 1940 and won his first 18 bouts, 11 by knockout. In his next bout he took on 61-bout veteran Mickey Farber and was stopped in the seventh round. Over the next three years Reif acquired experience to go along with his powerful punch. Interestingly, he lost his first two Madision Square Garden main events to Jewish boxers Danny Bartfield and Harold Green. Both outpointed Reif in hardfought battles. Next up was Willie Joyce, one of the finest boxers to never win a title. Once again Morris failed to land his big left hook and lost the decision.

The Garden’s promoters decided at this point to match Reif with someone he would not have to chase. On January 4, 1946, Reif went head-to-head with the great former lightweight champion Beau Jack, a tireless swarmer who threw 10 punches for every one thrown by an opponent. The 15,000 fans in attendence expected a great fight. They were not disappointed. The New York Times called it “one of the most exciting battles of recent years in New York.”29 In the fourth round, in the midst of a hot exchange, Beau landed a right uppercut under Reif’s heart that put the Brownsville slugger on the canvas for the 10-count.

BOXING IN ISRAEL

Sports have always been an important part of Israeli society, even in pre-state days. Soccer, and later basketball, became the two most popular sports. For the young pioneers participation in sports was considered more than just a recreational activity. As Hebrew University professor Anat Helman observes, “Zionists sought to replace the ‘old Jew’ of the diaspora— a stock figure in Israeli discourse, depicted as passive, cowardly, sickly and weak—with the antithetical ‘new Jew’ who was active, brave, healthy and strong. . . . Sports was regarded in the Yishuv [Jewish communities in pre-state Israel] as one of the instruments for creating this new Jew and imparting discipline for future military service.”27

Although the country’s athletic achievements do not match its remarkable accomplishments in technology and medical research, Israel has managed to produce its share of world-class athletes. Israeli athletes have won seven medals in the Olympic Games—in judo, canoeing, and windsurfing. The Maccabi Tel Aviv basketball team has won the European Championship six times since 1977. Other Israelis have won international competitions in figure skating, gymnastics, wrestling, fencing, and track and field. Despite ongoing political problems a growing number of Israeli-Arab athletes have joined sports teams, including at least five players on the Israeli national soccer team.

The various athletic associations received a big boost in 1989 when Russian premier Mikhail Gorbachev allowed Jews to leave the Soviet Union and emigrate to a country of their choice. Over the next seven years close to one million former citizens of the Soviet Union came to Israel. Among the immigrants were many highly trained athletes and coaches from various sports who brought their knowledge and culture of athleticism with them. It was during this time that a number of boxing gyms sprang up in Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Ashkelon. Today the Israel Boxing Association, the organization that supervises amateur boxing tournaments, has about 2000 registered members. (By contrast, the Israel Football [soccer] Association represents some 30,000 soccer players.) In recent years the two most successful Israeli boxers have been Yuri Foreman and Ron Nakash. Foreman, a junior middleweight, was born in Russia, grew up in Israel, and now makes his home in New York City. The former Golden Gloves champion won a professional title in 2010 but lost it the following year. Nakash, a 200-pound cruiserweight, has compiled a 26-1 record, with 18 knockouts. He turned pro at the age of twenty-seven, a late start for a boxer. He is chief commander and head instructor of the Israel Defense Forces’ Krav Maga Instructional Division.

The Israel Boxing Association’s general director, Dr. William Shihada, is making a noble attempt to use the amateur boxing program to build bridges between young Arabs and Jews in Israel. Jews and Israeli Arabs train and spar with each other in the same gyms. “In 20 years of my experience in running Israel’s boxing league, I have never seen any ethnic, racial, or religious tension among our kids,” says Dr. Shihada “Education for coexistence is at least as important, if not more important, than training fighters, as far as we’re concerned. For me promoting coexistence is the most important thing.”28 Most of the IBA’s members in Dr. Shihada’s program are teens and young adults (both male and female). Not surprisingly, the boxers come from the poorest segments of Israeli society, with about 70 percent coming from Arab villages, and the rest from inner-city neighborhoods populated by Russian and Ethiopian Jewish immigrants. All of the boxers are Israeli citizens.

Following his loss to Beau Jack, Reif won his next seven fights, six by knockout. In his last attempt at breaking into the ratings, he fought future welterweight champion Johnny Bratton at the Chicago Stadium on January 24, 1947. Bratton, too quick and skillful, won a unanimous 10-round decision.

Reif’s explosive left hook flattened 34 opponents, but more than punching power was necessary to get past the top welterweight contenders of the mid- to late-1940s. Like his famous Brownsville stablemate, Al “Bummy” Davis, Reif relied too much on his punch and less on boxing technique to achieve victory. Nevertheless, he was a feared puncher and a force to be reckoned with in the talent-laden welterweight division.

After he retired Morris worked as a house painter, and then took a job as a truck driver for the airlines. In the early 1970s he relocated his wife and three children to Los Angeles, where he worked in a youth center teaching boxing.

Maxie Shapiro was the last great Jewish lightweight to come out of New York City’s Lower East Side neighborhood. Bobbing like a cork in a stormy ocean, Maxie ducked and slipped punches with remarkable ease and countered with an array of combination punches. Except for a broken nose his face was unmarked, despite having engaged in 125 professional fights.

A GOLDEN AGE FOR BOXING MOVIES

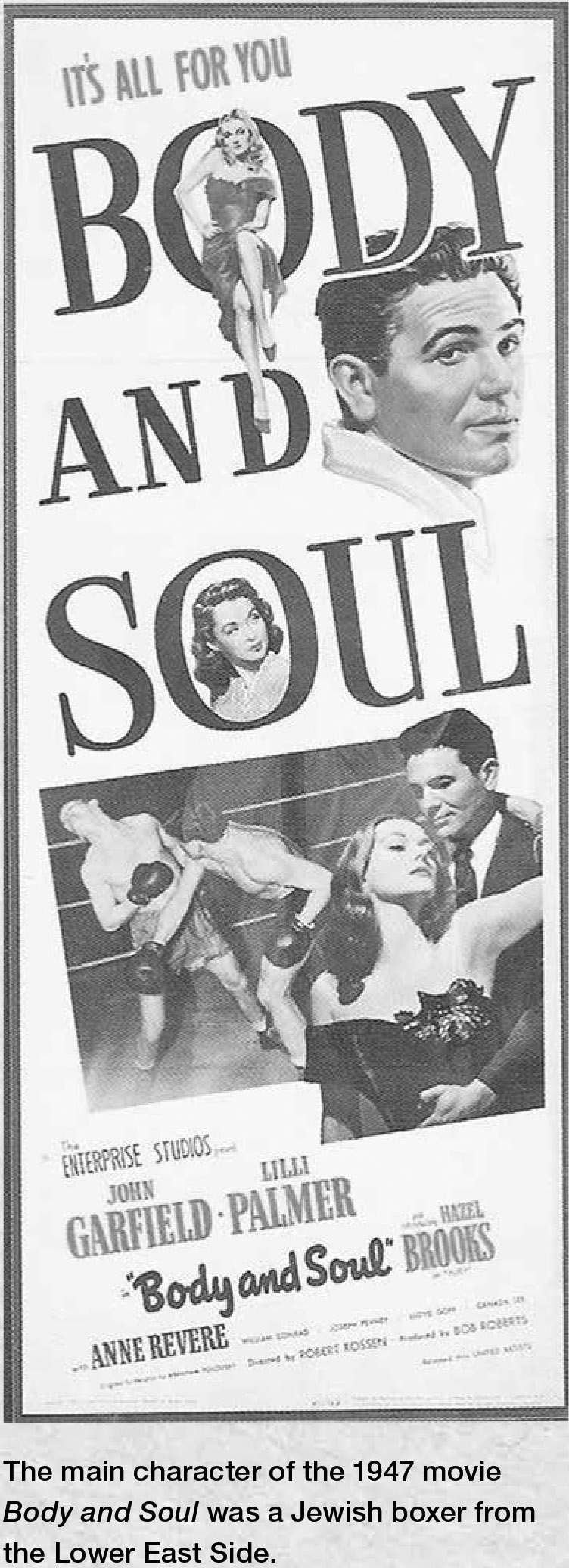

Six of the greatest boxing movies ever made were produced between 1942 and 1956: Gentleman Jim, Body and Soul, Champion, The Set-Up, The Harder They Fall, and Somebody Up There Likes Me. Jewish actors John Garfield (Body and Soul) and Kirk Douglas (Champion) received Academy Award nominations. Six years before it was made into a movie, Rod Serling’s Requiem for a Heavyweight debuted as a live TV production on the Playhouse 90 series of great dramas. Former boxer Jack Palance starred as the fictionalized broken-down ex-pug, Mountain McClintock. The 1962 movie version starred Anthony Quinn, in an equally impressive performance. (In deference to Quinn’s Mexican-American heritage, the main character’s name was changed to Mountain Rivera. Jackie Gleason and Mickey Rooney costarred.)

Of the films mentioned above, only Body and Soul (1947) clearly identified the lead character as Jewish. Garfield portrays the fictional Charlie Davis, a boxer from the Lower East Side of New York, who fights his way out of poverty to become middleweight champion of the world. His ethnicity is revealed in a scene in which his widowed mother (Anne Revere) applies for welfare benefits. The interviewer asks her religion and she replies, “Jewish.” In a key scene later in the film, Shimon, the local grocer, speaking with an unmistakable Yiddish accent, tells Mrs. Davis, “Over in Europe the Nazis are killing people like us just because of their religion, but here Charlie Davis is a champion.” It is one of the first references in a Hollywood film to the Holocaust.

Abraham Polonsky, who wrote the screenplay for Body and Soul, would later become a victim of the McCarthy-era Hollywood blacklist, as would John Garfield (born Jacob Julius Garfinkle).

Shapiro had a late start in boxing. After two years in the amateurs he turned pro in 1938 at the age of 25, and won his first 37 bouts before dropping a close decision to Al Reid. Four months later he outpointed Reid in a return match. After losing a split 10-round decision to future featherweight champion Jackie Wilson at the Baltimore Arena, Maxie won six in a row, including impressive wins over contenders Everett Rightmire and former featherweight champion Leo Rodak. Rodak was one of five past or future world champions Shapiro defeated. The others were Bob Montgomery, Jackie Callura, Sal Bartolo, and Phil Terranova.

On September 19, 1941, at Madison Square Garden, Maxie faced the great Sugar Ray Robinson. Even at that early stage of his career, Robinson, with only 23 fights on his professional résumé (to Maxie’s 58), was considered an extraordinary talent. Robinson at five-foot-11 was nearly five inches taller than Shapiro.

For two rounds Shapiro was competitive with Robinson. But after landing a hard right cross to Robinson’s jaw in the second round, it was all downhill. Sugar Ray’s almost superhuman athleticism combined with his tremendous punching power overwhelmed Maxie. Referee Arthur Donovan stopped the bout in the third round after Shapiro had been floored four times.

One year after the Robinson fiasco Maxie scored the biggest victory of his career with a decisive 10-round drubbing of future lightweight king Bob Montgomery in the latter’s hometown of Philadelphia. Their return bout two months later, also in Philadelphia, saw Montgomery win a close 10-round decision.

Maxie Shapiro is one of only three boxers to have fought both Sugar Ray Robinson and Henry Armstrong, two of the greatest fighters who ever lived. Armstrong, past his prime and in the midst of an ill-advised comeback, took him out in seven rounds, but the authenticity of that knockout remains questionable.

Shapiro was in and out of the lightweight ratings for about five years but never received a title shot. He retired in 1948, returning for one more bout in 1951 before hanging up his gloves.

MAKE MINE A MOGEN DAVID!

In the early 1950s, as televised boxing saturated the airwaves, manufacturers of products aimed at male consumers, such as beer, automobiles, cigars, and razor blades, all clambered to get on board the TV bandwagon and advertise their products to millions of potential customers.

In 1952 the Mogen David wine company became a sponsor of the Dumont Network’s Fight of the Week series broadcast from Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway Arena. (Mogen David, Hebrew for “Shield of David,” refers to the six-pointed Star of David.) The company manufactured kosher wines and hoped to appeal to a broader audience beyond its Jewish clientele, which may explain the reason the word “kosher” is never uttered by the velvet-voiced actor describing the wine’s virtues during the live commercials aired between rounds.

Remember the good old days when this time of the year was the signal for a good healthy dose of Grandma’s homemade spring tonic? That’s the kind of memory that really takes you back through the years. . . . Mogen David wine is a real taste of those good old days, rich with the same sweet Concord grape flavor of long ago [sips]. You know, even the warm ruby-red glow of Mogen David wine gleaming in the glass or your decanter seems to speak of a pleasant, peaceful world of yesterday. And Mogen David appeals to so many folks that it’s the biggest-selling wine of its kind in the world. [Translation: biggest-selling kosher wine of its kind in the world.]

Mogen David wine is always in good taste, whether your party’s a church social, card game, formal dinner, or an old-fashioned family get-together [sips]. This spring treat yourself to a memory. Enjoy the home-sweet-home wine like Grandma used to make.30

Although it’s doubtful that many church socials featured Mogen David kosher wine, the salesman’s pitch is indicative of boxing’s large and eclectic audience—Jewish and non-Jewish alike—during the golden age of televised boxing.

Hard-luck Georgie Small, a fearless two-fisted puncher out of Brownsville, Brooklyn, was a rising star in the middleweight division until a tragic event changed everything.

On February 22, 1950, Georgie and Lavern Roach were scheduled for a 10-round main event at the St. Nicholas Arena in Manhattan. Roach, a World War II US Marine veteran with moviestar looks, was on the comeback trail. Two years earlier he’d been overmatched in a bout with the great French middleweight, Marcel Cerdan. Roach was knocked down eight times in eight rounds before the bout was mercifully stopped.

After a brief retirement, the 24-year-old Texan resumed his career and won three bouts against minor opposition, bringing his record to 27-4 (11 by KO). Georgie Small’s record showed only six losses in 44 bouts (17 by KO). The 6–5 odds favored Roach.

Both fighters had previously worked out in the same gym and became friendly. But boxing Draw 1 is a business, and friendship or not, the match was made.

Roach, as expected, was the superior boxer, and was ahead in the scoring going into the 10th round. About halfway into the round Small landed a hard right to Roach’s chin that floored the Texan. He arose on unsteady legs and was promptly knocked down by another right. The referee ended the bout at this point. Roach got up but collapsed a few seconds later and was carried out of the ring on a stretcher. He was rushed to a nearby hospital but never regained consciousness, and died the following day.

Small was devastated by the tragedy, but decided to continue with his career. Three months later he appeared in a televised Madison Square Garden main event against future welterweight champion Kid Gavilan. The great Cuban fighter administered a savage beating and won a unanimous 10-round decision. Small seemed tense throughout the bout and was unable to launch a sustained attack, as if fearing he might injure Gavilan.

Contemplating retirement, Small did not fight again for another year. When he came back the results were mixed. Often, when he had an opponent in trouble, he would hold back. The memory of his bout with Roach was stifling his natural aggressiveness. Nearing the end of his troubled career Small lost decisions to middleweight contender Pierre Langlois and future champion Joey Giardello. In his final fight he was stopped by Argentina’s Eduardo Lausse, one of the division’s hardest punchers.

Fifteen years after his tragic fight with Roach, Small told journalist Jimmy Breslin that he was still tormented by guilt over the death of his friend.

Not yet 50, Small began to experience memory and balance problems related to the punishment he took in the ring, making him unable to hold a job that could support his wife and young son. He ended his days in an adult-care facility in Arizona, where he passed away at the age of 73.

From the age of 10 Allie Stolz had a burning desire to become a professional boxer and emulate his idols, former lightweight champions Benny Leonard and Al Singer. He devoted the next 18 years of his life to accomplishing that goal.

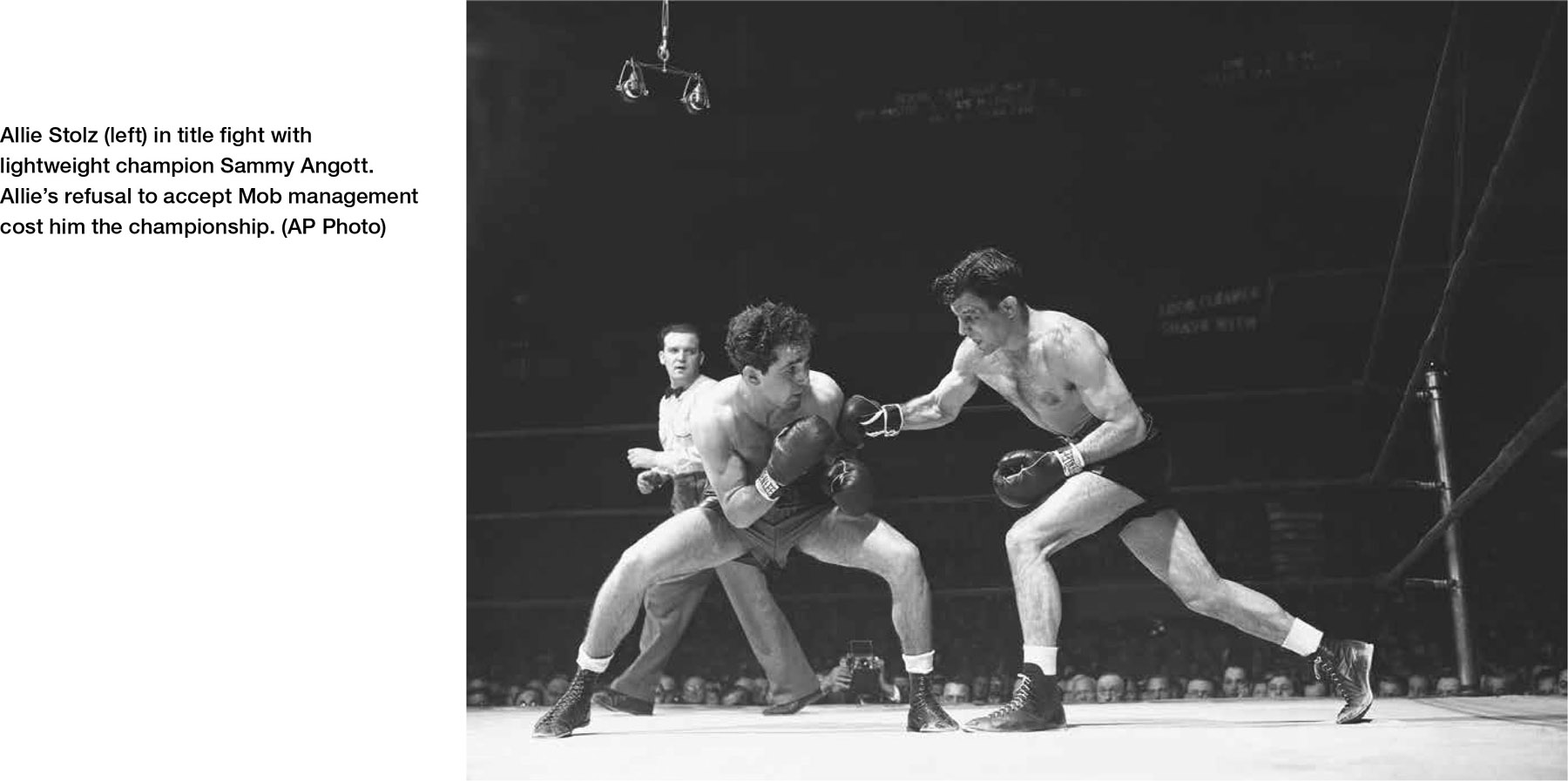

On the night of May 15, 1942, at Madison Square Garden, 23-year-old Allie Stolz appeared to have realized his lifelong dream. After flooring lightweight champion Sammy Angott for a nine-count in the third round, Allie controlled the pace of the fight while consistently peppering Angott with his accurate jabs and well-timed counterpunches. Angott fought back stubbornly, but it was obvious to the 16,000 fans in attendance, and the sportswriters sitting at ringside, that on this night Allie was the superior boxer.

When the decision was given to Angott the crowd was stunned. The referee had scored for Stolz but was outvoted by the two judges. Rumors spread quickly that the decision was fixed and that both judges had been bribed by organized-crime figures after Stolz had refused to drop his manager and replace him with a Mobcontrolled flunky.

Stolz, a slight underdog going into the fight, was crushed by the defeat. He would obsess about the injustice for the rest of his life.

In his campaign for a return bout with Angott, Stolz defeated featherweight champion Chalky Wright (non-title) and third-ranked lightweight contender Willie Joyce. He was subsequently outpointed by Chalky’s successor, the great Willie Pep, and was stopped by future champions Beau Jack and Tippy Larkin. Stolz won 10 of his next 11 fights (his only loss by split decision to Willie Joyce), thereby earning another shot at the lightweight championship.

Sammy Angott had since relinquished the title to campaign as a welterweight. This time Allie’s opponent was the famed “Philadelphia Bobcat,” Bob Montgomery. They fought before 11,000 fans at Madison Square Garden on June 28, 1946.

Fighting in his 75th pro bout (the last of his career), Allie displayed flashes of his old brilliance, but it was not enough. In a bout the New York Times called “one of the greatest lightweight battles,” the game challenger was floored six times, and finally counted out in the 13th round.

THE PIANO MAN PACKS A PUNCH

The proliferation of televised boxing ensured that the sport would continue to maintain its position in American popular culture throughout the 1950s. Training in a neighborhood gym or sparring with friends was still a rite of passage for many Jewish boys. In 1951, 16 year-old Allen Konigsberg, a resident of Brooklyn, was one of those young men. Konigsberg was a good athlete who enjoyed baseball, basketball, and boxing. He was intent on entering the New York City Golden Gloves tournament. Allen began training at a local gym under the watchful eye of a coach, but the aspiring boxer’s dreams were dashed when his mother found out about his secret ambition. She refused to sign the release form, abruptly terminating his nascent boxing ambitions. The young man later gained fame as a world-renowned comedian and filmmaker under the name Woody Allen.31

Legendary comedian Jackie Mason claimed to have fought professionally, although it’s more than likely Jackie mined that fantasy for its comic value. “You know, in a fight I might go down,” says Jackie, “but one thing about me . . . I don’t get up. Why should I get up? I get up again, he hits me again . . . then I’m down again . . . what, do I have to make three trips to the same place? I figured I’m not that busy, I’ll lay around a while. I noticed another thing . . . while I was lying there he wasn’t hitting me. I figure if I could have come in lying down I never would have had this whole problem.”32