INTRODUCTION

INORDINATE INSECTS

There is a possibly apocryphal tale in which the prominent British evolutionary biologist J. B. S. Haldane (1892–1964), while seated at a formal dinner next to the archbishop of Canterbury, was asked by the estimable cleric as to what he had divined of the Creator from the study of His creation. Haldane’s irreverent reply: “An inordinate fondness for beetles.”

While the veracity of this conversation having occurred may be questioned, it is an undeniable truth that insects are truly inordinate. In fact, if one were to make a cursory observation of all life on our Earth, then the inescapable conclusion would be that nature has a perverse preference for the six-legged. To date, we have discovered, described, and named around two million species in our world, slightly more than half of which are insects. Thousands of new insect species are added to the ranks every year, and while the discovery of a new bird or mammal is rightly heralded in the press, the flood of new insects being uncovered is typically overlooked. Yet, insects are as intimately entwined into our lives as any other collection of species, and in many ways they are more intricately linked and vital to our daily existence than most other groups. Insects are so commonplace that we scarcely pay them notice in the same way we are rarely conscious of our breathing. Whether we are cognizant of it or not, we intermingle with insects every day as we go about our lives. They are always underfoot, overhead, in our homes, where we play and work, and, although we might not wish to think about it, in our food and waste.

Detail of an engraved portrait of Cardinal Antonio Barberini (1607–1671) showing the Barberini family coat of arms with three bees.

Insects are both familiar and foreign to us, and it is their often-diminutive size and widely perceived cultural stigma that prevents most of them from becoming more endeared to us. From the dawn of humanity, our successes and our failures have been tied to insects. Civilizations have risen and fallen as a result of entomological interventions, with the directions of wars and territorial expansions reshaped by mostly unseen, six-legged foes. Our mythologies and religions abound with references to insects, either as plagues sent from wrathful gods or through allegories of insectoid industriousness, such as the counsel in Proverbs 6:6 to “Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways and be wise.” They also have represented nobility in heraldry, from the three bees on the coat of arms of the seventeenth-century Barberinis of Rome (see previous page) to the golden bees of the Frankish king Childeric I that were later so prominent on the robes and regalia of Emperor Napoléon (1808–1873).

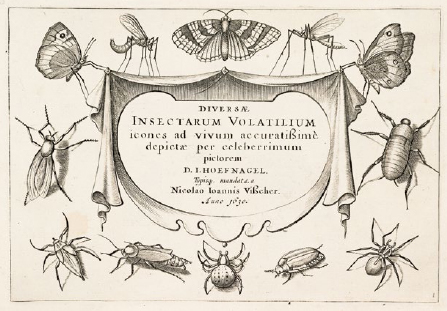

The introductory engraving to the theater of insect diversity as presented by Jacob Hoefnagel in his Diversae Insectarum Volatilium Icones (1630). Jacob engraved images of insects drawn by his father, Joris—also an artist—and arranged them with beautiful symmetry and precision that would be duplicated by later artists.

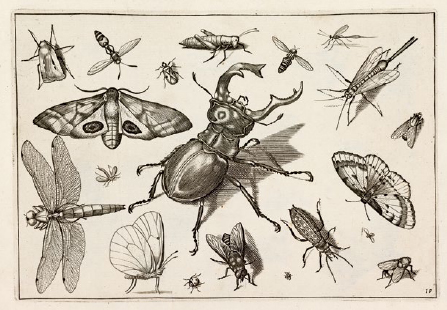

Another of Hoefnagel’s finely etched plates from Diversae Insectarum, reflecting the dazzling and seemingly infinite variety of insects—which has long attracted the attention of naturalists and artists alike.

Whether as a flight of butterflies, a hum of bees, a concerto of crickets, or a cloud of flies, insects in one form or another fill us with fear, revulsion, comfort, admiration, and even delight. We have a love-hate relationship with insects, as we compete with them for our crops, yet they are critical as pollinators of the same fields as well as of our forests; they recycle our wastes and till our soils, but they also invade and damage our homes; they are infamous for spreading pestilence and plagues, yet they may also cure disease. Further, insects are used to dye our fabrics and foods, alter our atmosphere and landscapes, inform our engineering and architectural efforts, inspire great works of art, and even rid of us other pests. They outnumber all other species combined and many individual insect species dwarf humans in terms of abundance. From this perspective, Earth belongs more to the insects than to us. Our evolution, physical and cultural, is inseparably connected with insects as both pests and benefactors. Were humans to disappear tomorrow, our planet would thrive. If insects packed up and left, Earth would quickly whither, become toxic, and die. With all of this in mind, it is a wonder that we don’t show greater appreciation for our multitudinous neighbors.

Estimates of the total current diversity of insects range from 1.5 to 30 million species. A conservative and likely realistic value is somewhere around 5 million species. At 5 million, it means we are still far short of understanding the variety of insect life surrounding us, as thus far entomologists have only described one-fifth of this diversity. This overwhelming task is made all the more daunting when we consider that insects are also one of the most ancient lineages of terrestrial life, with a history extending back more than 400 million years. Through the vastness of time and vicissitudes of cataclysms, insects have persisted and perished, but most often flourished. If it seems incredible to conceive of 5 million insect species today, the potentially hundreds of millions that cumulatively existed throughout the history of insects is staggering. Most species that have ever existed throughout the history of life are now extinct, and perhaps 95 percent or more of all species that ever existed are now gone. Nonetheless, they are part of an uninterrupted chain of descent extending from the first ancestral insect species to the millions that surround us today. In between, there have been innumerable performers on evolution’s stage, and while the curtain has closed on the acts of many, their collective triumph is unprecedented in the nearly 4-billion-year history of life on Earth.

As humans, we boast of our many achievements (and we do have many!), but we are fragile—perhaps among the least adaptable of species. We have occupied the whole of the world, but not through succeeding in each of those environs. Instead, we shape habitats to our needs. We live in the polar regions of our planet, but in domiciles that create a microclimate in which we can thrive. We live in deserts, but often in air-conditioned structures that similarly mimic our comparatively narrow range of tolerance. True, we can consider our ability to reshape areas to our liking as one of our defining glories, but there are other ways of measuring success, and it is hubris that leads us to think that we are paramount among the lineages of Earth.

Tropical lantern bugs (Fulgora laternaria) and a cicada (Fidicina mannifera) on pomegranate (Punica granatum), fruits of which were introduced to the Americas by Spanish explorers. From Maria Sibylla Merian, Over de voortteeling en wonderbaerlyke veranderingen der Surinaemsche insecten, a 1719 Dutch edition of her 1705 masterwork Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamerisium.

Insects are virtually everywhere, even in the most remote places. From the frozen poles to equatorial deserts and rain forests, from the peaks of the highest mountains to the depths of subterranean caves, from the shores of the seas to prairies, plains, and ponds, insects can be found in droves. The only place in which they have never managed to succeed is in the oceans, where they are characteristically absent.

The breathtaking range of form among insects is encapsulated in species as utterly disparate as delicate butterflies and heavy, ponderous beetles. From Rösel von Rosenhof, De natuurlyke historie der insecten.

Insects outnumber us all. Their segmented body plan is remarkably labile, and they have low levels of natural extinction with rapid species generation, leading to a history of successes eclipsing those of the more familiar ages of dinosaurs and mammals alike. Insects were among the earliest animals to transition to land, the first to fly, the first to sing, the first to disguise themselves with camouflage, the first to evolve societies, the first to develop agriculture, and the first to use an abstract language, and they did all of this tens if not hundreds of millions of years before humans ever appeared to mimic these achievements. Today’s insects are the various descendants of life’s greatest diversification.

THIS IS THE STORY of those pervasive little things that run our world, and it is illustrated by the great works of the past through which our many entomological discoveries were illuminated. While the numerous books featured in these pages are antique, the information contained therein in many instances is as vital today as ever. It is the fallacy of present ages to assume that old is synonymous with anachronistic or, worse yet, faulty and worthless. In reality, care of observation and accuracy of representation in texts and images one hundred or more years old may surpass anything that we produce today. Knowledge obtained long ago can be highly relevant to our current world. For example, in 2015 it was discovered that a single surviving copy of a ninth-century medical text, Medicinale anglicum (Bald’s Leechbook), contained a natural remedy that proved potent in treating the methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacterial scourge that otherwise laid waste to our modern medical efforts. Similarly, an 1879 article by the French surgeon Paul F. Segond (1851–1912) on the anatomy of the human knee led contemporary doctors to rediscover in 2013 an entire ligament critical in stabilizing the rotation of this joint, proving how “old” information from even the most intensely studied biological entity on earth—namely us—remains crucial.

Sometimes the only firsthand information we may have for a species is contained in rare books, such as accounts of dodos or Steller’s sea cow. Among insects, there are legions of species that we have scarcely seen again since intrepid explorers first encountered them long ago, and those descriptions of their appearances and lives are our only connection to organisms that may be driven to extinction before we happen across them again.

A folio depicting several species of mantises from Henri de Saussure’s Études sur les myriapodes et les insects (1870), photographed in the American Museum of Natural History’s Rare Folio Room.

Great works of the past, originals of which are now difficult to find, reveal to us the evolution of information dissemination and artistic representation in science, as well as our own perceptions and interpretations of our world, while simultaneously telling us of the grandeur of insect diversity. Unlike today, publishing in the past was difficult, and not for the faint of heart. To adequately depict species, particularly as if in life, required considerable skill. To illuminate a treatise one might have to carve images into wood and use the woodcuts like stamps. Later, intaglio printing relied on images engraved into sheets of copper, and ink then filled the grooves for transfer to folio leaves. Subsequent lithography, either in metal or on limestone, improved upon these methods, becoming the standard for embellishing texts. As one can imagine, there was little room for error, and only after the image was printed to the page would it then be colored. The total process could take years depending on the number of images and the number of copies to be made. The result of these labors were works of great scholarship and sublime artistic expression. The images herein are not mere adornments, but unique sources of scientific information. Few institutional libraries are as blessed as the American Museum of Natural History to have in a single repository such a sweeping breadth of works by a panoply of entomological luminaries. The scope of rare works on insects residing therein, like insects themselves, is inordinate, and it is fitting that we should allow their pages to inform us of insect evolution.

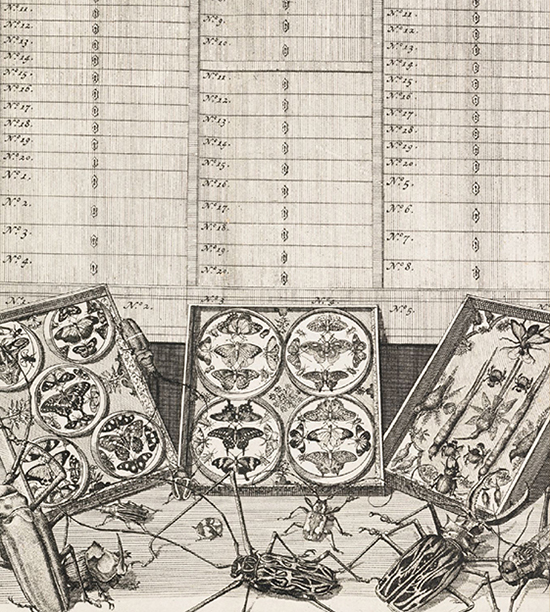

A cabinet of natural wonders from the world of insects, arrayed in their drawers, from Levinus Vincent’s Wondertooneel der nature (1706–1715).