5

DISCOVER A BIG, UNMET CUSTOMER NEED

Before we can solve a problem, we need to define it. We need to understand who grapples with it, how often, and how deeply it affects their lives. When we’re designing a service or product on behalf of a specific group of people, studying their behaviors, use patterns, and daily frustrations nudges us toward the most potent solutions. So our first step of the Growth OS is to explore the issue we want to attack and the various technologies or enablers we could use to blow it out of the water. That’s Discovery in a nutshell.

SHIFTING FROM PLANNING TO DISCOVERY MODE

Startups know that the correct place to start is not with an answer, but with a question: “What are the needs of unserved customers, and how can I meet them in a radically better way?” As we’ve insisted in previous chapters, we need to stop zooming in so tightly on what we can make and who might buy it, and zoom out instead to understand what people need. When we uncover a need that can be met differently using new technologies or enabling solutions, we’ve landed on an Opportunity Area (OA). It can feel counterintuitive and awkward to shift focus from our core competencies to the customer’s unmet need, but it’s a shift that reorients our companies toward authentic growth and productive creativity. If we want to launch an endeavor that has a snowball’s chance in hell of succeeding, we must start with the headaches and obstacles that large populations wrangle on a daily basis.

Yet here’s the rub: Technological innovation and adoption is moving faster than ever before. It took nearly five decades for the telephone to reach 50 percent of US households, but it took a mere five years for cell phones to accomplish the same penetration. Electricity didn’t hit the 10 percent adoption rate until it’d been widely available for thirty years; tablet devices reached 10 percent adoption after just five years.1 Inventors are creating devices, systems, and services that consumers didn’t know they needed, yet once these innovations are introduced, they’re embraced with wide-open arms. (And wallets.)

To the untrained eye, these market-creating innovations seem to come out of nowhere. Who saw the peer-to-peer business model coming? Or the blockchain? These concepts are so new and so divergent that they abjure comparison, and that makes them slightly terrifying. We can’t plan against the unknown unknowns, nor predict how many units we’ll sell, because no one’s ever sold them before. But the way things are going, those unknown markets are exactly where we need to focus our energy, attention, and money.

The traditional MBA toolkit—TAM analysis, financial projections, customer segmentation, competitor analysis, even go-to-market strategies—these are all tools that thrive in a world that is known, a world where the near future roughly resembles the near past. But when you’re building in a world where the markets, business models, and technologies of the future are rapidly changing, those tools are less effective. In this world, strategic business planning breaks down because the target is unknown; in this world, you must instead venture forward through a discovery framework.

HOW THE DISCOVERY PROCESS WORKS

Instead of starting with a solution—something we want to build that we’re (irrationally) confident is going to take over some market—the Discovery process begins with a question. More precisely, it begins with a question about a group of people. That question is, For some given group of people, focused on some particular aspect of their lives, what is top-of-mind for them? What are the problems they are trying hardest to solve, what unmet needs do they have, and how are they attempting to meet them currently?

Asking these questions without assuming we know the answers allows us to understand the problems that are truly important to our desired audience. For example, what needs do workers in the gig economy have that are invisible to companies who offer financial products to traditional, full-time workers? This in turn leads us to what we call “good hunting grounds”—areas where we can hunt for businesses to launch that will solve huge pain points, and where we have a real chance of creating radically new solutions to unmet needs. To continue our example, how might we meet short-term liquidity needs for freelancers and gig workers who have less predictability in their incomes than salaried workers?

The Discovery process can be simplified as follows:

-

Assemble a small, designated team

-

Pick a group of potential customers, listen, and observe

-

Consider relevant new enablers that could serve their needs

-

Understand the current and emerging business landscape, technology road map, and startup/venture ecosystem

-

Combine all of these inputs to identify OAs

-

Consider sizing, timing, and fit of each OA to downselect and arrive at the prioritized OAs—the hunting grounds—where we want to launch new businesses

Let’s step through each of those in more detail.

1. Assemble a small, designated team

Discovery work should be led by someone who has the ability to see beyond what the company is already doing and envision what it could be doing. This may be a contrarian, someone who is eternally playing devil’s advocate, or a person with a vivid imagination and the courage to pursue out-of-left-field ideas. The Discovery Lead also needs to have the position and credibility to take that contrarian view when facing down the CEO. Typically, this role is filled by an executive who is obsessed about the future of the company.

The people working alongside the Discovery Lead should be three or four folks who show a love of deep questioning and unbridled creativity. It will likely include a financial analyst who can help with market sizing, perhaps someone from your corporate venture capital team who has an eye on startup trends and VC investment flows. You might consider a technology expert from R&D, a mad-scientist type who’s five years ahead of the technology curve, as well as a customer insights expert with ethnography skills. Consider the realm you’re entering and the scope of your exploration, make a wish list of roles or personalities who could be beneficial, then fill those slots.

The Discovery process we outline here usually takes ten to twelve weeks. At the end of this process, you may find members of the Discovery team are good fits for other roles in the New to Big machine. Or they may transition back to their day jobs, yet remain available as advisors or additional resources for the startup teams. In either case, their contribution to the operating system cannot be overstated. Their mandate is largely to uncover and synthesize areas of opportunity for the company, creating a foundation of knowledge that will guide leadership to define their investment thesis.

2. Pick a group of potential customers, listen, and observe

Discovery work starts with people, but not all people, of course. In order to maintain a reasonable scope of work, we need to determine which demographic or psychographic groups or subcultures have big needs that we believe we can solve in radically new ways. The groups we define remain fairly broad—senior citizens, young mothers, millennials living at home, active single men—but bring some focus to how and where we’ll conduct our initial Discovery research.

Our interest is in identifying pain points, but—as we hammered home in chapters 3 and 4—we never ask about them directly. Instead, we observe people in the wild. What we do with these subjects isn’t proprietary or groundbreaking; much of it is drawn from ethnography, a hands-on, fieldwork-based research method common in the practice of anthropology and sociology.

Our Discovery teams typically start the work with members of segments that demonstrate extreme behaviors to understand a range of needs. (Think back to the candy bar example from chapter 3, where we mentioned talking to candy store owners and people who hadn’t eaten sugar in decades.) These folks are of particular interest because they either have acute pain points, or they are solving common problems in novel ways. In the latter case, we’re often able to improve upon the makeshift solutions they’ve created in order to serve a larger population. Focusing on the extreme cases helps us consider radical new solutions.2

Then the team will shift to subjects from the broader group, setting up in-home, at-work, or ride-along research moments. For example, instead of asking subjects about their frustrations around a pain point like meal planning and grocery shopping, we look in their fridges and pantries, ask what they cooked for dinner each night this week, find out if they go to the nearby farmers’ market, and watch them pack lunches for their kids. We want to learn about their daily life and understand the values and beliefs that drive their behaviors. Then we want to dig into the subtext to suss out the core of their need.

For example, working with a company in the packaged-food space, we focused on mothers, studying their shopping, cooking, snacking, food storage, and restaurant-going habits, among other factors. We looked at their use of prepackaged meal kits, and discovered that although mothers loved the convenience, those with husbands and teenage sons reported that the men in their lives wanted larger portions. So the mothers bought supplementary food, cooked larger portions, found themselves gaining weight, and watched their cholesterol levels climb. Based on this information and a handful of other insights, observation showed us that for these women, nourishing their families was a higher priority than eating healthy themselves. That’s not a phrase they would have used verbatim, but it’s an inference we felt confident making based on our experience in their homes.

In doing this work, it’s imperative to interview people within a given segment from multiple parts of the country to ensure you’re getting a full spectrum of views and cultural nuances. Keep the groups small, observe and listen, then extrapolate what you see bubbling up. Identify things you see and hear multiple times and home in on the problems and needs those findings reflect.

3. Consider relevant enablers

Next we shift the conversation toward devising innovative ways to solve the identified problem. The Discovery process focuses on utilizing relevant enablers—trends, technologies, or business models—that can be brought to bear on a solution. How might a global financial institution leverage crowdfunding in a radically new way? How might blockchain smart contracts be deployed in a distributed supply chain to ensure transparency and document ethical and sustainable practices?

Most of the problems that people have are age-old problems. How do I nourish my body? How do I look my best? How do I communicate with my loved ones? New enablers have a shot at introducing a substantially better solution to these problems than existing solutions have in the past.

So in 2019, we set our sights on enablers like vertical farming, artificial intelligence (AI), 3-D printing, blockchain, virtual reality, drones, universal internet access, microbiome research, gene editing, and more. All the stuff that showed up in sci-fi films in the 1990s and is now, miraculously, available to the general public. Plus, we consider business models that are new or new to the company: peer-to-peer, direct-to-consumer, B2B, vertical integration, and more.

We want the Discovery teams to concentrate on technologies and business models that could plausibly be brought to bear on the problems of our target audience, but also remain fiercely imaginative about everything on the table. For instance, if a fashion brand wants to deliver a personalized customer experience, the company might say, “AI couldn’t possibly help us with this. There’s no way we’re putting robots into customer-facing roles!” But AI encompasses things like speech recognition, sentiment analysis, and chat bots, which could have applications in e-commerce and in-store experiences. As we consider enablers, we want to keep our minds as open as possible so that we can see all the myriad possibilities.

Although we begin to dance around how these enablers might solve a problem at this stage, we spend most of our energy identifying and analyzing them. We generally end up with three lists:

-

Enablers and business models that could be used to address this specific issue

-

Enablers and business models that our competitors are already using to address this issue

-

Enablers and business models that are wicked cool but totally useless for this application

Out of context, many of these enablers seem thrilling but somewhat outlandish to the companies we partner with. The use of 3-D printing and drones? Maybe for a Philip K. Dick novel, but for an energy company or beverage producer? And yet when we do our homework, we learn that dozens of funded startups are already using 3-D printing or drones to bring solutions to market. Reality and fantasy are in lockstep. The enablers in group 3—the ones that are cool but useless—are discarded, of course, but many more end up in groups 1 and 2.

As our teams explore enablers, we are careful not to replicate market-dominating or crowded spaces. We’d never say, “Hey, let’s look at mobile phone apps to solve transportation needs!” because at this point, that’s been done to death. So if we’re devising transportation-related solutions, we’ll look at what’s starting to emerge right now.

4. Understand the ecosystems

Neither pain points nor enablers exist in a vacuum. Once our internal teams have identified both, our next task is to consider everything that’s influencing the target market, from new players in a field to emerging trends to unexpected partnerships. We take a few giant steps back from the work we’ve done so far and scope out all the relevant activity we can see. Considering this spread helps us form a thesis as to how the industry is changing and compile a macro view of the market landscape.

By putting both players and events on the board and considering how they’ve interacted in recent months and years, we begin to see trajectories and patterns. We see what’s been done, what’s been overlooked, and what’s failed miserably. For instance, we’ve seen over and over again that while companies tout 3-D printing as the future of personalization, it has not delivered mass personalization at scale. (It is, however, incredibly useful in speeding up product development and creating flexibility in manufacturing systems.3) We see relevant trends in adjacent industries. We see ideas that should’ve succeeded but didn’t…and if we’re lucky, we see why.

Understanding the ecosystem is essential both because it educates us on all of the forces at work, and because it helps us understand timing. (Remember, we need to be right and on time.) A 50,000-foot view allows us to predict when world-changing enablers and shifts in behavior will collide, and to make sure we’re there when the collision occurs.

Let’s take a quick side trip to Hollywood for an example. For decades, film producers and movie studios have insisted that movies marketed to African Americans with predominantly black casts won’t be profitable.4 You’re almost certainly aware that 2018 saw the release of Marvel’s Black Panther, a film with a predominantly black cast, which became the highest-earning Marvel Cinematic Universe movie and had the fifth-largest opening weekend of all time.5

It can’t be denied that Black Panther’s success is due, in part, to timing. In the last decade, new, global platforms have emerged that have been wielded to promote inclusivity, diversity, and a wide variety of social justice issues, and as such, representation of minority groups has seen explosive growth in popular culture, though much work remains.

And beyond social media, racial struggles and injustices have been widely portrayed in television shows, movies, music, and the news. Police shootings and harassment, the public reemergence of white supremacist groups, the continuation of mass incarceration, and hundreds of other aggressions, both macro and micro, are no longer hidden in the shadows. Activist groups, such as Black Lives Matter, have earned high levels of coverage for their movements, and have helped to firmly situate issues of racial injustice in a national conversation. The social and political climate in the United States, in 2018, would therefore be much more responsive and engaged with these oft-discussed topics than they would have been twenty years ago, or even five. The conversations had become common, and the energy high.

So when Black Panther opened during US Black History Month in 2018, moviegoers of many races and ethnic backgrounds were ready. The film’s creators carefully selected artists and collaborators who would fuel conversation around the movie and some of its social justice themes, including prolific rapper Kendrick Lamar, an outspoken advocate for racial equality, who produced the soundtrack, and renowned production designer and Afro-futurist Hannah Beachler (you might remember her from Beyoncé’s record-breaking Lemonade).

Of course, Black Panther was not the first superhero film that featured black heroes (see: The Meteor Man, Blankman, Blade, X-Men, and Captain America), but in the words of culture critic Carvell Wallace, in these previous superhero iterations, “the actor’s blackness seemed somewhat incidental. ‘Black Panther,’ by contrast, is steeped very specifically and purposefully in its blackness.”6 Again, twenty years ago, such deliberate steeping might have been perceived by some audiences, or even film producers, as a fiscally irresponsible choice, but in the United States in 2018, it was both financially and ethically impactful.

Timing isn’t everything (remember, you have to be right and on time), but Black Panther’s record-breaking performance illustrates that timing can transform a great idea into a certified hit.

Ecosystem exploration has proven absolutely indispensable to the companies that Bionic has partnered with. While exploring the market landscape with one of our packaged-food partners, we got a clear picture of just how diverse and varied the company’s competition really was. We noticed that Google—a company that played infrequently in the nutrition sphere—was incredibly bullish on a future food outlook that relied heavily on plant-based and synthetic meat proteins. Other than Blue Bottle Coffee, Google had steered clear of most food and beverage investments during its twenty-three-plus-year history. Yet in 2015, Google Ventures began investing heavily in Soylent and Impossible Foods, among other protein-pioneering companies.7 When we began our ecosystem exploration with the partner, we were focusing mainly on the obvious Fortune 500 rivals in the packaged-food space. Our research forced us to broaden scope.

With this data in hand, we realized that our partner needn’t be nearly as concerned with what its usual rivals were up to; instead, they needed to start keeping tabs on the Big Five tech companies. Our ecosystem explorations proved that the traditional competitive landscape had shifted dramatically in just a few years.

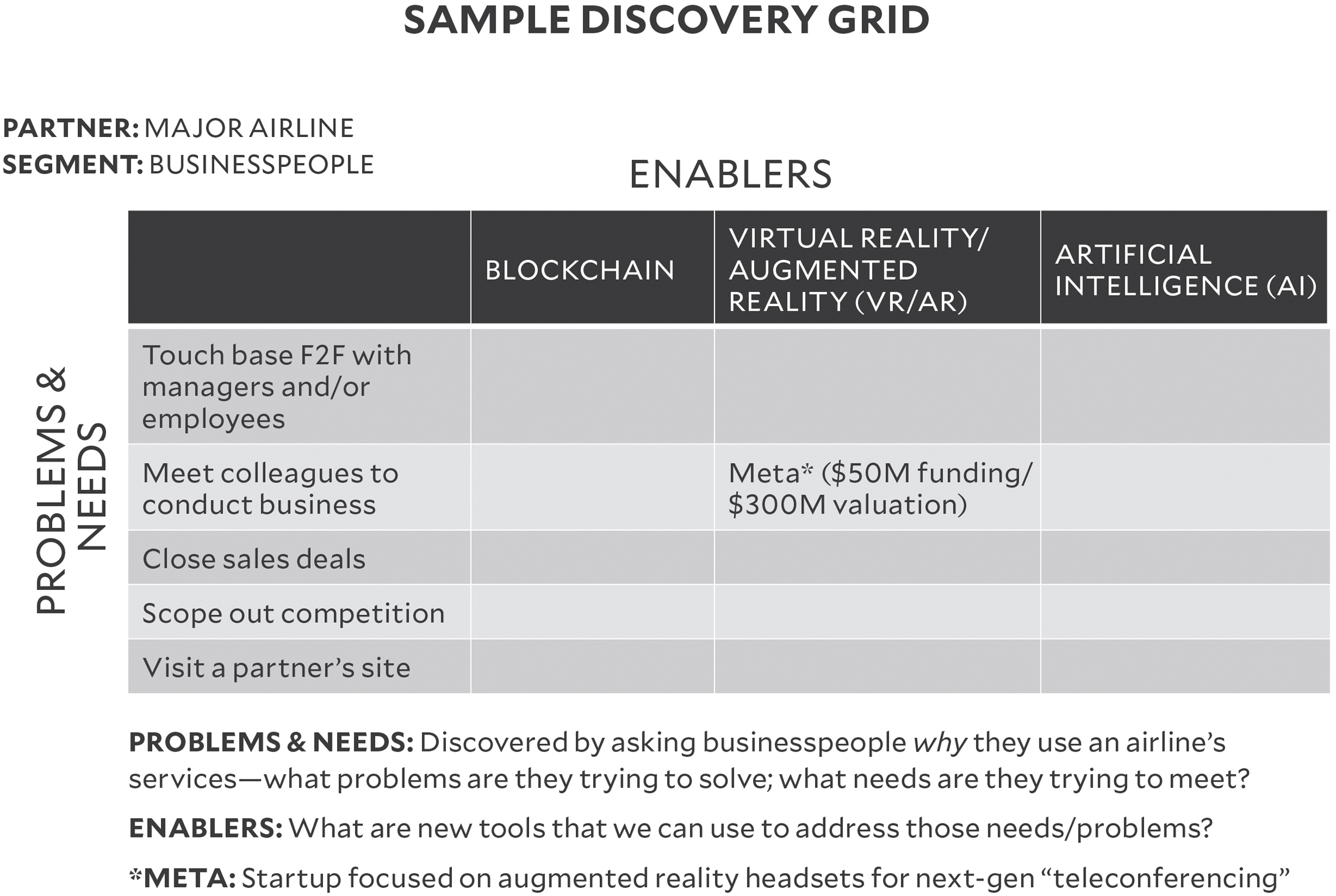

5. Plot the Discovery Grid

When we first discussed Opportunity Areas (OAs) back in chapter 3, we touched on the idea of positioning our companies at the intersection of consumer needs and enabling solutions. This step in the Discovery process is where we bust out the dry-erase markers and draw out a grid that plots those intersections.

The grid exercise is designed to help us get an even clearer picture of the overall ecosystem, and also shine a spotlight on untapped OAs. Here’s how we do it:

-

All potential enabling technologies are plotted on the x axis.

-

All issues that are top of mind for our target population are plotted on the y axis.

-

If a competitor company has addressed an issue from the y axis using an enabler from the x axis, that company’s name is written at their intersection.

-

If no one has addressed an issue from the y axis using an enabler from the x axis, the blank square at their intersection represents a nice, ripe OA.

So simple, yet so fundamentally effective. Having done your research before plotting this grid, you’ve looked into your competitors’ mistakes, you know how much money everyone is getting from investors, and you have a sense of how much revenue everyone’s raking in. And with all that information plotted out in this format, you begin to see where the action is, where the heat is. You can see where the long-standing players have been, where new money is, where other VCs are investing. And perhaps most important, you can see the white space where nobody has thought to put their money.

Those blank spaces remain blank either because there’s no real opportunity at the intersection, or because there’s an opportunity there that no one has spotted yet. In the latter case, our team has identified a valuable OA and defined our “good hunting grounds.” We’ve determined where to focus our energy and resources by mapping out pioneering solutions to real-world problems that haven’t yet been tried by anyone else. And spaces where there is quite a bit of action would be a clear no-go zone for startups with limited resources and no infrastructure, but large organizations may still consider a play if they think they can use their scale and stature to win; it merely requires a different approach.

Honestly, taking in the completed grid and pondering those blank spaces is a pretty magical experience. All the ethnographic research, the brainstorming, the investigations of emerging technologies, the digging into competitor ventures, the metaphorical blood, sweat, and tears of the Discovery process gels into this gorgeous grid that can be used to chart a map of our business’s future. We can see where there’s a ton of action right now, where there are hints of action, where there’ll be loads of action in five years, and where there’s no action at all.

Even more profoundly, the grid doesn’t just tell us where and when to build businesses. If a problem on the grid has no new enablers, it tells us where to direct our company’s R&D money. If a problem is already being solved ably by someone else, it tells us to consider buying their company. Instead of just directing the development of new business endeavors, the grid creates a decision tree that seeds a full-fledged growth thesis within a company. It’s designed to spark organic business (in-house startups), but also allows us to identify inorganic business opportunities (partnership and acquisition targets) and direct R&D resources; it helps us determine how to attack a problem comprehensively from multiple, informed angles. All that from one simple, hand-drawn grid! These are just some of the decisions the Growth Board will make as they make strategic and investment decisions across their growth portfolios (more in chapter 7).

6. Consider sizing, timing, and fit of each OA

In order to downselect and create some boundaries for our potential hunting grounds, our last Discovery step is to dig into issues of sizing, timing, and fit for each of our OA candidates. At its heart, Discovery is really about scoping work for the next team to fully explore, and these final steps help us to ensure that our scope is both reasonable and feasible. This is the part where we stand back, consider the various OAs that have made the rough cut, and decide which ones are worth pursuing.

Making those calls is equal parts art and science.

We start with sizing, since we want to dispense with any OAs that don’t have the potential for massive impact and continued profit. When exploring a fundamentally new product or offering, Andreessen Horowitz’s Benedict Evans suggests contemplating two key questions: “First, you have to look past what it is now, and see how much better and cheaper it might become. Second, you need to think about who would buy it now, and who else would buy it once it is better and cheaper, and how it might be used.”8

The Discovery team does this by studying proxy markets, exploring how similar or related products are viewed, used, and consumed. This is simpler for some OAs than others, of course. Say we were interested in exploring self-driving cars. We have data galore on car-purchasing habits, and although autonomous vehicles are quite new, they’re close enough to traditional cars that we can mine existing data and make reasonable predictions. Drones, on the other hand, have few logical proxies. In the past, if you wanted an aerial photo, you needed a helicopter…but far more people can afford camera-equipped mass-market drones than to rent choppers for the afternoon.

We may examine adjacent markets, too, if proxies are frustratingly hard to come by. And knowing that some of our proxies may end up being off-base, we explore a variety, harvest all the information we possibly can, and triangulate our sizing guesses. Then we move on to timing.

Our first timing question is always “Are there any blockers out there that would make pursuing this OA right now substantially more difficult?” The most common blocker is governmental regulation, either in terms of laws that prevent something from happening (like those that prevented Amazon from implementing drone-based delivery) or laws that need to be in place to protect our proposed venture (like pending patents or stronger copyright enforcement).

Our second question is “Why now?” We assume that a dozen entrepreneurs exactly like us, or smarter than us, have tried similar ventures and failed. So if we’re going to chase that opportunity ourselves, we need to know how the world, the market, and our own capabilities have changed. Those who tried before were just as smart as we are, or even smarter, they had all the resources, and they still failed. So what factor, technology, enabler, law, or consumer appetite is present now that was absent when they attempted it?

Bionic recently teamed up with a partner who offered oral health products and was looking to leverage “internet-enabled interactivity” somehow. (No, we don’t know what that means in the context of oral care, either.) After working through most of the Discovery process with their team, we pressed them to consider going in a different direction; we said, “Interactivity is simultaneously vague and restrictive. What about a lightning-fast toothbrush? Wouldn’t people be ecstatic over a device that reduced the time it takes to brush your teeth from two minutes to ten seconds?”

Our timing research, however, proved that building such a device is not possible. Not yet. The technology simply hasn’t been developed to support those functions, and likely won’t be available for another decade. So we had to reroute our thinking and pursue another path.

Timing is about zooming out and taking a real systems view of the space and asking ourselves, “Does this make sense now and is this the right time?” As corny as it sounds, we’re looking to see if the stars have aligned, or if they’ll lock into the right spots anytime soon, if they haven’t yet. The whole Bionic team has watched businesses launch at the wrong time and fail spectacularly, and then seen someone come along just a few years later with the same idea and knock it out of the park. (Remember the Chewy and Pets.com example from chapter 3?)

Finally, we take a look at fit: “Is this OA a good fit for the company’s core competencies, aligned with its mission, and in a space that appeals?”

To be clear, our current strengths shouldn’t be our sole focus. We need to look beyond our core competencies when considering fit. To truly innovate, we must see beyond what we do well now, and imagine what we could do well in new spaces with the same skill set. Or imagine how building new core competencies could complement our existing ones.

You’ve heard of Airbnb, but have you learned to surf with a local in Costa Rica?

Before Airbnb was Airbnb, it was two roommates in San Francisco who struggled to pay their rent. A design conference was coming to San Francisco, and they thought that if they set up three air mattresses on their floor, they could charge a small fee to designers for a bed and the promise of breakfast. Three guests arrived, each paid eighty dollars, and the roommates knew that they were onto something.

After the conference in August 2008, Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky reconnected with their third roommate from college, Nathan Blecharczyk, and built out a website.9 Air Bed and Breakfast launched for the first time as a roommate matching service, not one for room rentals.10 But Roommates.com was already a behemoth in the space and quickly crushed them. They returned to their original model and relaunched. No one cared. They launched a third time at SXSW in 2008, but despite more than ten thousand conference attendees, they only had two customers (and one was Chesky).11

They decided to pitch investors anyway. Out of fifteen investor introductions from mutual friends, seven ignored the intro and eight flat-out rejected them. By this point, they were broke and in massive debt.

Then the Democratic National Convention came to Denver, and with traditional hotels unable to accommodate the massive influx of visitors, Gebbia, Chesky, and Blecharczyk found dozens of homeowners who wanted to earn a few extra bucks by hosting attendees. Traction was up, but the site still wasn’t turning a profit. To make extra money, the founders redesigned cereal boxes into “Obama Os” and “Cap’n McCains” and sold them on the streets by the convention for $40 each.12 In just a few days, they raised $30,000 in bootstrap funding.

Venture capitalist Paul Graham finally took notice. He invited them to Y Combinator, an accelerator that propels young startups into the market in exchange for a small stake in the company. But getting into Y Combinator didn’t mean that the company was set. Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures, along with many other investors, famously rejected them, saying, “We couldn’t wrap our heads around air mattresses on the living room floors as the next hotel room and did not chase the deal. Others saw the amazing team that we saw, funded them, and the rest is history.”13

And, to some degree, it is. The team dropped the lengthy name and switched to “Airbnb.” The cofounders personally stayed in all the hosts’ homes in New York City and reviewed each of them. When listings in New York were lower than in other cities, the trio rented a $5,000 camera and personally photographed dozens of homes, resulting in two to three times more local bookings and twice as much revenue from the city alone.14 They soon picked up a check from Sequoia Capital for over half a million dollars. Within four years, Airbnb had launched in eighty-nine countries and hosted over a million overnight stays.15 After seven funding rounds, investors such as Y Combinator, Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, Founders Fund, TPG Growth, and Keith Rabois brought investment totals to over $776.4 million, and in the spring of 2014, the platform had a valuation of $10 billion, catapulting Airbnb to a higher valuation than Wyndham or Hyatt.16

But, of course, Airbnb hasn’t limited their scope to housing rentals. A company founded on air mattresses and homemade breakfasts has grown to include an “events, experiences, and tours” site, too.17 Users can learn karate or surfing, practice another language, explore Rome with a local, or even volunteer for service work. For its age, the Experiences tab of Airbnb grew thirteen times faster than the homes section had.18 Experience hosts started earning thousands of dollars every year, with some hosts totaling $200,000.19

Though Airbnb started as a place to rest one’s head at night, the goal has become “to be the one-stop shop for travel.”20 Every decision that the company now makes pushes them toward that status. While investors couldn’t envision a world in which anyone paid to sleep on a low-end air mattress, and while few foresaw Airbnb’s core functions to one day include all the experiences that accompany travel, Airbnb is becoming synonymous with all-inclusive traveling. In just nine years, with over 5 million listings in 81,000 cities and 191 countries, coordinating 300 million+ stays, and earning over $2.5 billion in revenue, their vision was clearly validated.

The reason we examine sizing, timing, and fit—and one of the reasons why the entire Discovery process is so crucial—is that the next step in the Growth OS involves dedicating a team to exploring the most promising OAs. If you’re going to assign a team to work on a project full-time for several months, you need to make sure the endeavor has the potential to be the right size, being explored at plausibly the right time, and has the potential to work for your company. When you don’t rigorously analyze and downselect all three of these factors, you could go down one of these common dead-end paths:

YOU GIVE THE TEAM A WIDE-OPEN SCOPE AND THEY DROWN: You say, “Explore millennials! Or China! Or AI!” And your team has no idea where to start, or what they’re supposed to glean from any experimentation, and they make zero headway.

YOU GIVE THE TEAM AN OVERLY NARROW SCOPE AND THEY FREEZE: You say, “Go launch a fantasy sports app for millennials who are on track to become high-earners!” Tasked with this highly specific undertaking, your team is likely to start engaging in bad behaviors like surfacing only the evidence that supports the undertaking (success theater!), rather than listening to the commercial truth. They do this because the implication when you give them a super narrow scope is not “Explore multiple solutions to this problem,” it’s “Go execute on this project.”

A primary goal of Discovery is to frame the opportunity and size it as accurately as possible. You want to scope out the hunting ground carefully so your team feels confident it can take action against it, but also isn’t afraid to come back to you with truths that might invalidate it.

WHY BOTHER WITH DISCOVERY?

It’s possible that some of you are saying, “Well, that sounds like commonsense research to me. Why would anyone launch a business without going through all those carefully calculated steps?” While perhaps others are thinking, “You’ve got to be kidding. That’s going to take forever! Can’t we just fast-track the research and skip to launch?” The hard truth is that Discovery does take time, and resources, and careful, thorough analysis.

When you perform traditional research then plow ahead, you may get lucky and hit on a solid solution for an enduring problem. But if something goes haywire along the way, you may not have the information you need to course-correct. And if your solution goes to market and succeeds initially, then tanks, you may not know why.

On the other hand, when you invest in understanding your potential market, researching new enablers, and forcing yourself to see the entire ecosystem, you can build your new bets from a place of informed, synoptic wisdom. You don’t just know what to do, you know that it hasn’t been tried before and that it will have a massive impact on a specific customer base. You may be diving into the deep end, but you’re doing it with oxygen tanks and wet suits at the ready.

Now that we’ve identified our Opportunity Areas, it’s time to validate our findings.