6

VALIDATE LIKE AN ENTREPRENEUR

At the seed stage of any startup story, whether cofounders are mapping out their new venture on a whiteboard or a diner napkin, they start by making four key assumptions: that there is a cohesive group of people, whom they can find, that shares a common problem; that their solution actually solves that problem; and that the business model for the solution is viable for the customer. Every successful entrepreneur knows that until those four assumptions are proven true, it would be useless to grow the venture. They’d be wandering in the dark, while their already-slim chances for success steadily diminish.

But most enterprise new-venture stories tend to skip this seed stage; they usually start by simply deciding to build something, making a big bet on a solution to a problem that has yet to be validated. Then they commingle making with commercializing, and any learning along the way that might disrupt the go-to-market timeline is ignored. In this environment, the truth is secondary to delivering on plan.

This chapter outlines the part of the operating system where the Opportunity Areas (OAs) we’ve discovered are transformed into portfolios of startups through a methodology we call Validation. By definition, to validate is to prove the legitimacy of something. It’s as simple as that. In the startup ecosystem that drives New to Big, Validation is the practice of entrepreneurship adapted for the enterprise. It is the process of proving the “commercial truth” of a potential startup before making a large investment to formally launch and scale the business.

We’re here to help you back up and start at the beginning. We want to demystify the methods, mechanics, and tools of entrepreneurship so you can learn at the speed and cost that startups do. Because, as they say, whoever learns the fastest, wins.

THE PRINCIPLES OF VALIDATION

At its core, Validation is the formalized methodology of entrepreneurship adapted for established companies. In formalizing this approach, we drew upon elements of Eric Ries’s Lean Startup approach, Stanford d.school’s Design Thinking, and Steve Blank’s Business Model Canvas to create a repeatable process that helps us refine startups in the earliest stages through experiment-based learning. Ultimately, this approach increases the speed of learning and decreases the cost.

ASSEMBLING AN OA TEAM

Let’s first define who is doing the Validation work: The employees you assemble for each OA are essentially your in-house entrepreneurs. Because they can come from many levels within the company and yet will serve as one cohesive team, we like to call them cofounders. While one may have been a manager in their previous role and another an associate, here they are equals.

Rather than being tasked to a specific project, as OA cofounders they will be committed to solving a customer problem by validating (and invalidating) a large volume of ideas. Like entrepreneurs in the startup world, these cofounders must thrive on ambiguity, love to tinker, and, together, bring a cross-functional set of skills along with the humility to do any job, large or small, to improve their chance of success. (In chapter 8, we’ll dig into how to identify and select the employees who will thrive as cofounders.) Unlike the startup world, however, these cofounders will be tasked with exploring multiple solutions within an OA through a diverse range of experiments before downselecting to a single startup.

At the seed stage, OA teams are small and nimble, usually with three full-time cofounders:

-

COMMERCIAL: One cofounder should be a strong communicator with deep business development, sales, and/or marketing experience, who is well-connected within the organization. For example, we’ve often seen former brand managers excel in this role. Think of this as your “startup CEO.”

-

TECHNICAL: One cofounder should be a Sherlock-level problem-solver driven by a desire to understand how things work. This person is analytically minded with strong business model or product experience. Depending on what field you’re in, this could be a software developer, R&D scientist, or even someone with underwriting or risk management experience. This is your “maker.”

-

INSIGHTS: One cofounder should be connected to customers and motivated by the desire to truly understand their behaviors, motivations, and needs. For example, this could be someone from the marketing function, like a consumer insights associate. This is your “customer whisperer.”

Guiding the cofounders is an Executive Sponsor for the OA, who serves to push cofounder thinking, ensure the rigor of Validation, and remove roadblocks. (We’ll talk more about the role of the Exec Sponsor in chapter 7 when we discuss the venture capital side of the Growth OS, embodied by the Growth Board.)

CONSTRUCTING A GOOD HYPOTHESIS

Every startup begins with a set of hypotheses about the customer, their problem, the proposed solution, and the business model. In order to validate (or invalidate) that hypothesis, we have to start by identifying the assumptions embedded in it. Otherwise, we risk forging ahead without first confirming the legitimacy of that all-important problem-solution-market trifecta. A good hypothesis is made of assumptions that are simple and focused, each conveying one important idea that is directly related to the solution and the business model. Here’s an example:

Let’s say the customer need we are considering is American millennials who have pets with health concerns. One initial startup idea is that this demographic might be interested in a Fitbit-for-Fido type of product that helps them monitor their pets’ health on a daily basis. This would be helpful both for pets with preexisting conditions (diabetes, kidney issues), and elder pets who are entering their twilight years. As we consider our hypothesis, we refine our assumptions:

TOO BROAD: American pet-owning millennials care about their pets’ health.

(We can prove this quite easily, but it doesn’t give us enough information to create a targeted offering.)

TOO NARROW: American pet-owning millennials will spend $150 on a device that monitors and reports on their pets’ activity, heart rate, and sleep.

(Whoa there! A price point, product functions, and the specific data it will generate? Too much, too soon!)

JUST RIGHT: American pet-owning millennials are actively monitoring their pets’ health.

(Simple, focused, actionable. “Actively monitoring” is behavior that we can observe, while “caring” is not.)

From this starting point, we can design experiments to validate that this population is, in fact, dealing with this need. If we learn that it’s not, we can synthesize the experiment results to decide how to pivot: Is it the wrong customer? Or does this “need” not actually exist? Or are customers just not interested in solving this need? By starting Validation work with a hypothesis containing well-defined assumptions, cofounders set themselves up to raise these kinds of productive questions at every turn of events.

TESTING THE HYPOTHESIS

As we move from calibrating our hypothesis to testing it through experiments, we need to watch our step. This is where it becomes easy to create false positives by asking potential customers to articulate their needs. Remember, what customers say may be wildly different from what they do in real life.

Part of that disconnect is that typical customer research doesn’t cost customers anything, so social conditioning kicks in and they take the nicer path, telling us what (they think) we want to hear. But the other part of that disconnect is that customers may not be consciously aware of their problem, or be able to articulate desired solutions that don’t yet exist. By designing experiments to suss out facts about actual behaviors, we’re able to uncover insights about the core needs we are seeking to address rather than rely on their self-awareness or limitations of imagination.

THE SKINNY ON EXPERIMENTS

We’ve found that enterprises have a distinct bias toward surveys and, when it comes to respondents, they believe that more is better. Entrepreneurs, on the other hand, prefer to whip up quick-and-dirty experiments to run on a dozen or so people to learn and keep moving forward. The question is always, What’s the quickest, cheapest thing we can do to decrease risk and increase confidence that we’re moving in the right direction?

At Bionic, we have a library of validation experiments that we employ at different stages or to test different types of assumptions. Here are a few of our most commonly used customer experiments (B2B and industrial experiments obviously look different).

EARLIEST STAGE

CUSTOMER PROBLEM INTERVIEW/ETHNOGRAPHY:

You don’t need a prototype, or even a hypothesis to perform these experiments. These are focused on listening to people, asking open-ended questions, and observing behavior to uncover unmet needs. We outlined an example of an ethnographic interview in the Discovery chapter.

WHAT IT GETS YOU:

Ethnography helps you get beyond the obvious problem and uncover the latent need. It also helps you develop empathy for the customer as you walk a mile in their shoes.

EARLY PROTOTYPE

FLIERS/POP-UP:

These are tests that can be done with almost no physical prototyping of any kind—just print up some fliers with your idea on them, put them somewhere public, and see how many people take them. Alternatively, you can set up a pop-up shop to engage people in discussion around a hypothetical solution, using a prototype as a stand-in for a real product or solution. In both cases, the aim is to gauge people’s reactions to something that looks real at very first glance, but is not.

WHAT IT GETS YOU:

An early prototype is a tool we build to transform an abstract concept into something concrete. A low-fidelity prototype doesn’t need to be a precise representation of the final solution. Instead, it is a way to synthesize and further refine the solution concept, clarify thinking, align the team, and (crucially) get specific feedback from customers.

LATER-STAGE PROTOTYPE

LANDING PAGE TEST:

To perform this test, we create a Google account and launch an ad campaign using search engine marketing, rotating in different ad copy to test interest levels. So if we were looking at a foot care OA, we might test ads that target different aspects of foot health: “Do your feet ache?” alongside “Do your feet stink?” alongside “Are foot issues affecting your marathon performance?” The ones that spark the most interest help us decide which solutions to pursue.

THE WIZARD OF OZ TEST:

In this scenario, we build a semi-automated interface for customers on the front end, but do all the actual work manually on the back end (“Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!”). The customer doesn’t see how the fulfillment is being accomplished, only the interface and results. This allows us to validate the value proposition before we invest in building out complete solution functionality. For example, you may think a new startup is using a fancy algorithm to recommend the best clothes for your figure, but if it’s a Wizard of Oz test, it’s actually a person (likely a cofounder) pulling together looks by hand to see if you like the offering before they invest in the algorithm.

WHAT IT GETS YOU:

Later-stage prototypes are all about building a preponderance of evidence. Strong signals from early prototype testing are qualitative in nature, and they move us toward these later-stage experiments that are aimed at capturing more quantitative data.

PRE-LAUNCH

PRE-SALES:

With products that are fully baked and getting ready for launch, a pre-sales campaign is a great way to measure interest in a do-vs.-say way and gauge ultimate intent to buy. Create a fully functional site, direct traffic to it, and start taking orders on your product before it is built.

WHAT IT GETS YOU:

Handing over cold hard cash (or in this case, credit card details) is the best “do” signal there is!

LEARNING FROM THE EXPERIMENT

Bias is an unavoidable part of human nature. There are dozens of cognitive biases that impede our ability to make good decisions. We default to things we already “know” to be true based on personal experiences, our rosy recollection of the past, or our preference for things we recognize, among other biases.

The power of Validation rests in our willingness to acknowledge our biased assumptions, design experiments to test those assumptions, and, finally, learn from those experiments, even if they contradict our predictions. That learning is the commercial truth, and it points us toward the opportunities for real, validated growth.

THE THREE SEED STAGES OF VALIDATION

As one Bionic in-house entrepreneur put it, “Validation is like making bread. The dough rises, and you punch it down. Then it rises again, and you punch it down. And all the time you’re making the idea stronger.”

All that rising and punching ensures that our proposed startups aren’t just amazing in our heads, but have a chance of succeeding in the real world, too. As we cycle through the stages of Validation, we’re constantly synthesizing our results and iterating on our hypotheses. We’re celebrating productive failure and updating our assumptions and turning the crank once again.

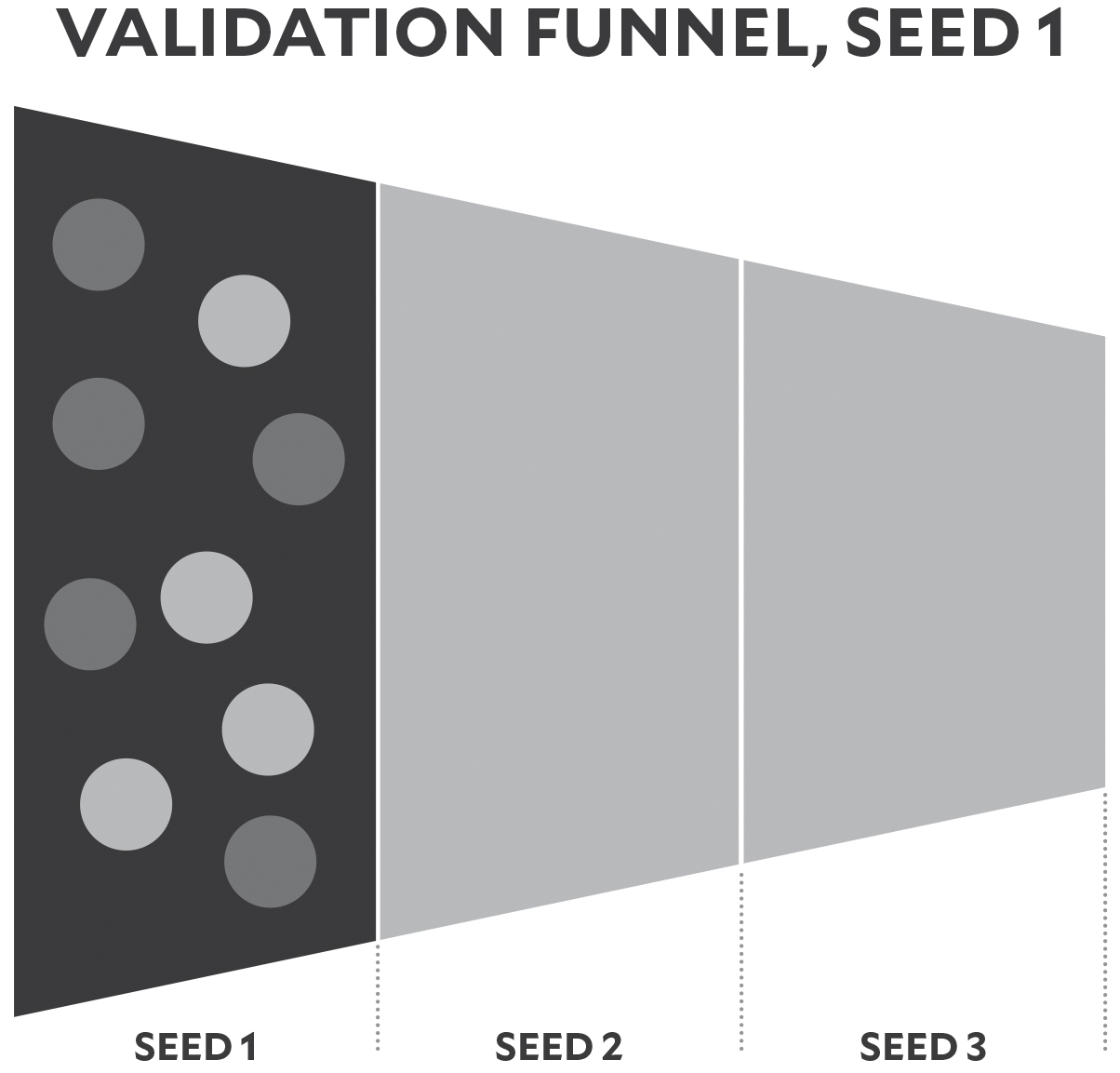

That recursive process takes place across three seed stages, each of which will emphasize a different aspect of our three-tiered question:

-

Who is the customer and what is their need?

-

Does our solution actually meet that need?

-

Is the business model we’re envisioning for the solution a viable one?

We need answers to all three before we can move on to building and, eventually, scaling the business. But we also need to bear in mind that all three are inextricably connected. This means that as we progress, changes in one dimension will cause the other two to adjust accordingly. If our understanding of the customer problem shifts or expands, the solution and business model will change in tandem. If we’re exploring the solution and hit a major snag, we must be prepared to go back and recalibrate our comprehension of the problem and also adjust our vision for the model.

As you might have gathered, this means that Validation won’t progress in a nice, neat, linear way. There will be some zigzagging or spiraling in addition to what feels like clear, forward progress. Remember, though, that none of this means you’re wrong or falling behind. This process creates an ongoing dialogue between the learnings at the solution level and the OA level. We may kill and pivot many solutions, and through that gain great clarity about the OA. Validation not only ensures you don’t launch untested solutions, but also points out when you’re not thinking about the right OA altogether. (This is why CFOs fall in love with Validation: It saves you a ton of money.)

With that caveat about the zigging and zagging out of the way, we decided to lay out the seed stages in a linear progression because we want to impart a clear understanding of all three. Before you can start building, you need to know what to build. And to know what to build, you need evidence validating your customer, their need, your proposed solution, and the best way to bring that solution to market.

Seed 1: Search for the root cause of the customer problem

The first seed stage is about uncovering deep insights into people and the root causes of their problems. The mantra for Seed 1 experimentation is “What are the results from our experiments telling us about the problems within the OA?” Throughout Seed 1, the team is constantly thinking about whether they’re examining the right ideas and looking for the spark of insight that will lead them to a bigger opportunity.

What does this look like in practice?

A few years back, we worked with a partner who was interested in foot health and wellness, and as we worked our way through Discovery, we realized that this was a surprisingly large problem that encompasses many populations. Since your body interacts with the world from the ground up, changes in your feet change everything. Feet, like teeth, are a barometer for overall human health, and when they’re achy or chapped or in pain, it affects everything from mood to mobility.

Foot health is also an issue that impacts different customer groups in different ways. A marathon runner may be concerned about corns or bone spurs; an elderly person might experience pain due to chapped or cracked skin; a woman in her thirties might find herself newly unable to tolerate high heels as the fat pads in the ball of her foot naturally deteriorate. Everyone’s feet wear out or break down, but the causes of foot-centric issues are diverse.

So as we started Seed 1, we worked to identify which problems were acute enough that customers would seek and pay for a substantially better solution. Although we explored pro and amateur athletes as a potential target customer, our problem interviews and ethnographic research revealed that a large proportion of senior citizens were feeling this problem acutely and were likely to embrace new solutions. So we chose to focus there.

Now, this partner specialized in chemical engineering, so most bone- or joint-related issues were going to be tough for them to address. It made sense to consider concocting some creams or lotions, but we were aiming for markedly better, drastically different solutions from those currently stocked in the foot-care aisle at Walgreens. So we started kicking around the idea of partnering with a startup that was 3-D printing shoe inserts, and injecting the insoles themselves with various treatments: anti-sweat formulas, anti-chafe medications, or conditioning creams. Developing an understanding of the customer and their problem propelled us forward into Seed 2: solution validation.

The purpose of Seed 1 experimentation is to validate:

-

WHETHER THERE IS A REAL PROBLEM: In other words, do we have evidence there is a real need, or was this just a hunch?

-

WHETHER THERE IS A COHESIVE GROUP THAT FEELS THIS PROBLEM ACUTELY: To launch a viable venture, we will need to consistently acquire customers. In order to do that, we must be able to identify who experiences this problem acutely enough to seek a solution.

-

HOW BIG THE TAP IS FOR THAT COHESIVE GROUP: Although we looked at TAP when we first scoped the OA in Discovery, as we get more specific about the problem and learn more about which customers feel this problem, we gain more understanding of the size of the opportunity and whether it is large enough to proceed.

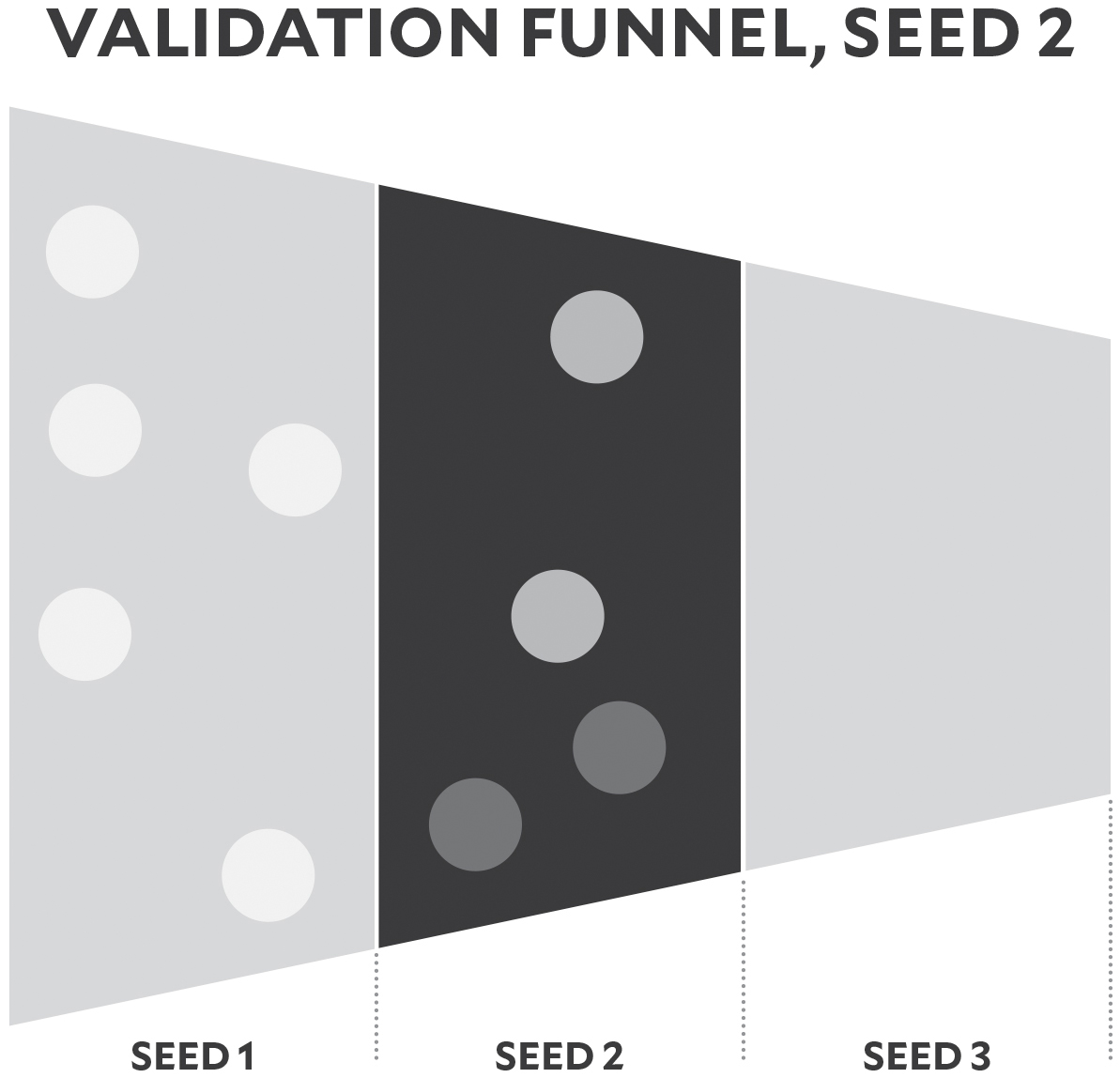

Seed 2: Putting solutions through their paces

Seed 2 is about ensuring we offer exponentially better solutions than whatever our customer is currently using (we call these “10x solutions,” though ten times better is almost always a stretch goal). This stage is also often about acquiring our first customers who are part of a potential beachhead market: They’re who we want to win over first, before bringing our offerings to the wider world. But now, instead of looking for insights into the root of their pain (which we tackled in Seed 1), we’re devising experiments to reveal insights about our proposed solutions.

Experiments at this stage require slightly higher-fidelity prototypes than our last round, often a working Alpha. (When we make the leap from images to code or from sketches to a 3-D prototype, we create what’s called an Alpha: something that works but with limited functionality. In the case of B2B or industrial businesses, an Alpha could take the form of a Letter of Intent or other on-paper expression of interest.)

Here’s an example of Seed 2 experiments with a banking partner a few years back:

Our partner wanted to find ways to support freelance workers, many of whom weren’t well served by traditional banking services and products. Big banks don’t always offer credit cards or loans to folks who can’t produce W-2 forms, and don’t make their main offerings friendly to people who juggle multiple jobs and have fluctuating incomes. We all know that the gig economy is booming, but the banking industry hasn’t done much to accommodate the shift.

One OA team put forth the hypothesis that “freelancers both want and lack freelancer-specific banking products, support, and tools.” They ran it through Seed 1, and confirmed it was a real problem. When it passed into Seed 2, we homed in on the subproblem of fluctuating income and real-time gaps in cash flow or solvency, something that makes freelancers pull out their hair in large handfuls. Our proposed solution offered the 1099 crowd access to customized, short-term financial products based on their projected dry spells.

In addition to offering peace of mind during work droughts, the solution was also designed to provide truly accessible support. We streamlined the application process, built in pre-approvals, and made these financial products relatively hassle-free and easy to secure.

So what did all this look like in terms of actual experimentation and testing? Well, Seed 2 experiments can take a variety of forms, but in this case we worked with a dozen customers and had them interact with a variety of low-fi prototypes. We sketched out a possible app, and printed out the various components onto pieces of paper. (We said it was low-fi!) Then we walked them through the different screens, and took them down different paths through the app: “If you click this menu, here are the options you’ll see. Where do you want to go next?” As they made choices, we took notes and asked questions.

Before we started coding and building an actual app or website, we wanted to understand what a freelancer might actually seek and use. If we mocked up five features, and all twelve of our customers completely ignored feature number three, we knew we should cut it.

We also asked them for qualitative feedback: “How does this live up to your expectations? You said you were really interested in an app that helps you anticipate income gaps. We made one; what did we do right, and what did we do wrong?”

Once we’d gotten a round of feedback on our printout-app, we created a prototype that was clickable but not fully active. About half the buttons didn’t work, and it utilized static data, but gave more of an authentic app experience. And then we mocked up an actual app that would take in and process some of our testers’ information but still wasn’t fully functional. Our goal with these iterative prototypes was to continually ask our beachhead customers, “Is this solution living up to your expectations? Is it doing what you hoped it would do to solve your problem?”

The purpose of Seed 2 experimentation is to validate:

-

WHETHER OUR INITIAL CUSTOMERS LOVE THE SOLUTION WE’VE OFFERED: In other words, is there appetite for this offering?

-

WHICH KEY FEATURES EXCITE THEM MOST: When we know what our customers need most from a solution, we can focus on that, which positions us to deliver significantly higher value than current solutions offer.

-

HOW WE WILL MEASURE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF OUR SOLUTION: We need to have a clear picture of the metrics that matter, and easy ways to capture data about them.

THREE LENSES TO EXAMINE SOLUTIONS THROUGH

When I started writing The Startup Playbook, I had two burning questions for the veteran entrepreneurs I interviewed: How did they select their ideas? And what did they do in the first five years to keep their companies going and keep them from dying? What I discovered was that the founders’ learnings could ultimately be distilled into five lenses through which they vetted and built solutions to customer problems. The first three lenses are vital to keep in mind as you work through Seed 2 Validation.

1. PROPRIETARY GIFTS

Every company that has achieved extraordinary success has something that sets it apart from the competition. This “something” could range from technical knowledge to deep industry experience to an asset or built-in operational advantage that no one else has; it’s a proprietary gift unique to the organization that cannot be replicated. This gift creates an unfair advantage; the company that possesses it is specially equipped to tackle certain consumer needs efficiently, effectively, and in profoundly new ways. When you can identify your company’s proprietary gifts and bring them to bear, you can change the world. When you boldly embrace your unfair advantage, you create your own shortcut to prosperity.

Proprietary Gifts in Action: In 1994, Amazon launched as an online bookstore, but founder Jeff Bezos’s long-term vision for the company was considerably more ambitious. Over the next decade and under his guidance, Amazon established and refined its supply chain and distribution model first for books, then leveraged it to expand into CDs, software, video games, electronics, apparel, furniture, food, toys, jewelry, and more. As Amazon marched on into more and more categories, it systematically chipped away at the primary point of friction in e-commerce: waiting for your order to be delivered. Bezos had the foresight to predict that a company with a truly effective, robust fulfillment at its heart could be transformative. Rather than pursuing profitability, Amazon leaned hard on their proprietary gift and invested in building unmatchable fulfillment systems, distribution centers, and other delivery infrastructure. It set the standard for free two-day delivery with its Prime service, then shrunk the window further with same-day and (in certain areas) one-hour delivery. That proprietary gift has created a moat around Amazon’s existing e-commerce business while also creating a competitive advantage as it builds new businesses like AmazonFresh alongside forays into the brick-and-mortar grocery business with the acquisition of Whole Foods.1

2. PAINKILLERS, NOT VITAMINS

Successful solutions solve a problem that is big, painful, and persistent: a repeated behavior or constant need that customers wrestle with on an ongoing basis. And the solution cannot be a vitamin, something that is nice to have and that you might even buy once, but that, on a day-to-day basis, probably sits unused at the back of a shelf. It must be a painkiller, something you ensure is always in stock and easily accessible because it solves your immediate need, effectively and consistently.

When the solutions we devise are painkillers for our customers’ ailments, we can build entire companies around those solutions. And if we make ourselves totally irreplaceable, even when those customers think about quitting us, they won’t. Even when they see shiny new solutions popping up, they won’t walk away.

And on the flip side, if the customer problem isn’t akin to chronic pain that needs soothing, we’ll struggle to create a strong case for a successful solution.

Painkillers, Not Vitamins in Action: In 2015, Fitbit reported sales of 4.5 million devices with revenues up 235 percent from 2014.2 But while the company was quick to tout device sales figures, they neglected to disclose that active daily users for the wristband were in decline. (“Success theater” in action! Focusing on impressive metrics instead of the most meaningful ones.) While many people were eager to buy a wearable device to track their health stats, about one-third of these owners ditched their device within six months. Additionally, there’s no strong research that proves Fitbit is a key factor in weight loss and health management.3 So, while Fitbit was a leader in sales of wearables, the device’s overall effectiveness was more along the lines of a vitamin than a painkiller. It was a nice to have, but if you forgot to put it on one day, it wouldn’t kill you.

In contrast, Nike recognized a recurring, deeply aggravating pain point for their customers and created a new business model around it. If you happen to be a parent, you’ve probably noticed that kids can wear a brand-new pair of shoes for approximately four days before growing out of them. Parents worldwide are in a constant state of shopping for shoes for their growing children (a singularly thankless task for many), and doing so feels like setting their money on fire. Enter Easy Kicks: Nike’s subscription service that gives kiddo customers access to new shoes whenever they want ’em for $20 per month. The program is a logistically new way to engage with customers that both creates a recurring revenue stream for Nike and turns a painful experience into a peak experience for parents and kids.4 People will never stop having kids, and kids will never stop growing out of their shoes, and parents will never stop resenting the endless buying cycle. All of which makes Easy Kicks an innovative and effective painkiller.

3. 10X IMPACT

When our companies have the means, talent, and desire to expand into new markets, narrowing the field of potential ideas can feel overwhelming. As we evaluate those ideas and decide which ones to abandon, we need to be ruthless. Ideas that produce incremental improvements are a waste of our time. We’re searching for revolutionary, potent, dynamic ideas that will have significantly more impact than their predecessors. Ideas that create marked competitive differentiation. This isn’t about chasing competition or relying on the typical benchmarks of success. This is about generating and nurturing ideas that have the potential to solve big, painful, unsolved problems while generating tens of millions of dollars in revenue (which can grow into billions).

10x Impact in Action: When Sara Blakely launched Spanx in 2000, “girdles” had gone the way of the dodo and “shapewear” was not yet a thing. Yet she knew there was a gap in the market; since no other solutions were offered, women had been cutting the legs off their control-top pantyhose to get the upper half’s figure-smoothing effects. This new customer behavior indicated a better solution would sell well. So she designed a sturdy Lycra undergarment that eradicated the bulges, bumps, and pantylines that plague women of all ages and sizes. Even the earliest iterations of Spanx were easily massively better than hacked-off hose, since they packed more shaping power, addressed more problem areas, and could be washed and worn multiple times. Once women got wind of this new foundation garment, Spanx began flying off department store shelves. And although plenty of knockoffs have since emerged, none have eclipsed the Spanx brand. Blakely created the shapewear market, and by building it on a product that was 10x better than the existing solutions, she was able to transform one idea into an undergarment empire.5

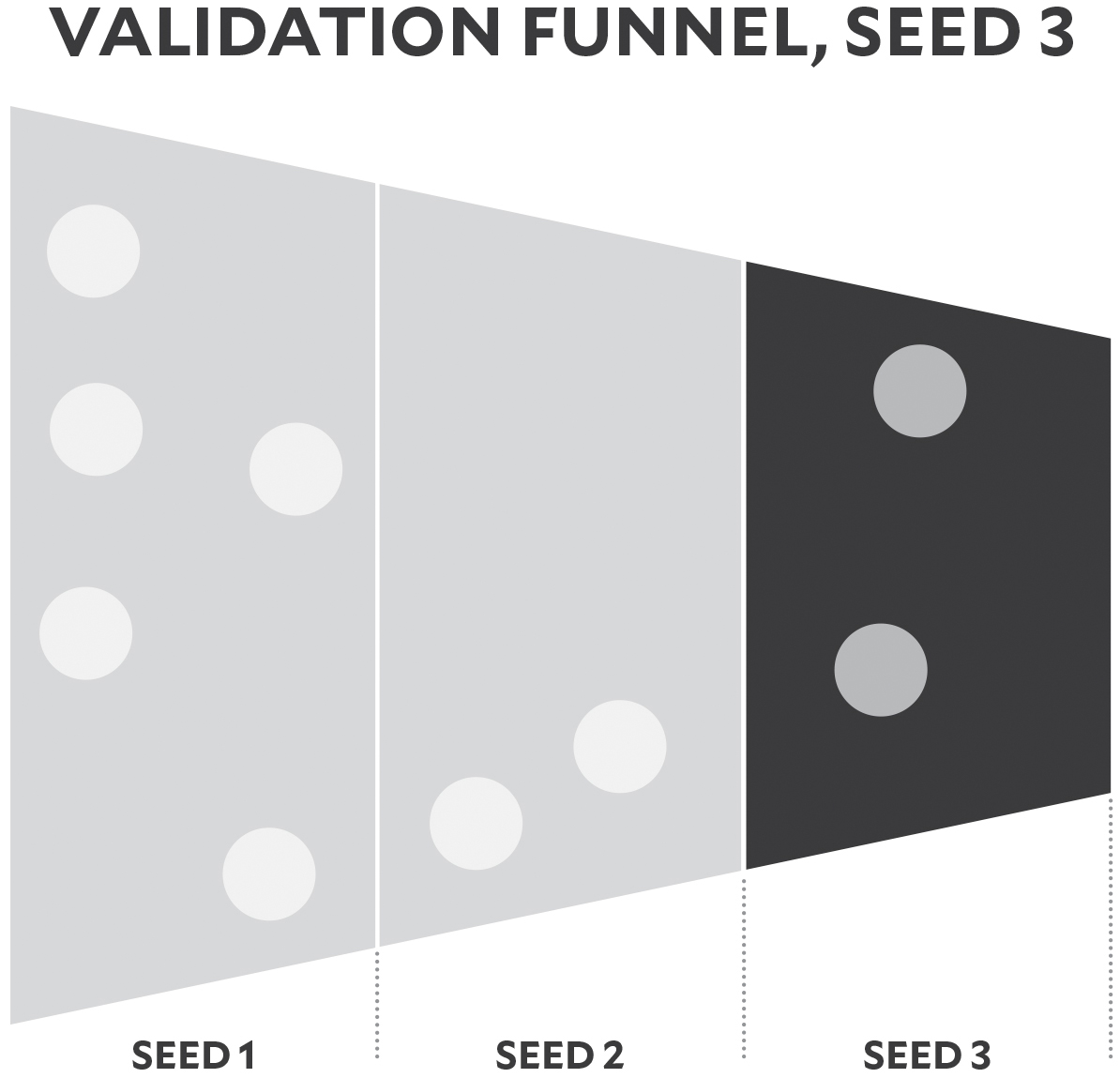

Seed 3: Honing the business model

Now that we’ve confirmed the customer problem and gotten a rough read on the proposed solution, we need to be sure there is a repeatable and scalable business model for the solution. In Seed 3, we’re testing our proposed economic exchange of value, whether that is based on customer revenue, advertising revenue, or some other monetization opportunity. We’re keeping an eye out for metrics and working to understand which handful of them actually matter for this business model. And we’re looking ahead to determine which operational hurdles might be the most challenging as we move into building the startup.

To see this in action, let’s take a trip to Mexico City.

We worked with a financial services company to help create some user-friendly, modern online banking solutions for its Mexico City customers. The city itself is forward-thinking and incredibly cosmopolitan, but somehow its banks have remained in the dark ages. Part of the problem is that many people in Mexico just don’t trust banks. It’s a very cash-rich society and also a very high-crime society, so people are wary of the bank-grade security required for checking their balances and transacting online. Instead, they go to physical branches and wait in line—usually for an hour or longer—to make deposits and handle their banking needs. Our partner wanted to launch a digital banking experience that Mexico City residents would truly trust to make investments, track daily spending, and monitor savings. The hypothesis was that a better online banking solution would help customers monitor their spending and save more intentionally.

Initial testing in Seed 1 and Seed 2 revealed that small business owners were particularly eager for a solution like this. Since they were often commingling their personal and business accounts, they saw real value in a tool that would help them keep careful track of their expenditures. We mocked up a banking app in Seed 2 that performed well in experiments, so the team moved into Seed 3 to validate the assumption that online banking customers would keep higher balances across accounts, which was how our partner earned money. This assumption was crucial to the success of the venture’s business model, and it needed to be tested.

We ran a pilot in Mexico City with one hundred people, loading a rough cut of the banking app onto their phones and asking them to use it for ninety days while we monitored their behaviors. We also gave them a daily banking assignment, something like “Move money from account A to account B today,” or “Pay a bill online.” We studied their activities and watched carefully to see if being more informed as bank customers positively impacted their spending habits.

To our delight, it did! The small-business customers loved having the ability to monitor their cash flow more closely, and ended up keeping higher checking and savings account balances overall. The team’s next step was to nudge them toward investing.

Typically, to get a money market account in Mexico City, a customer would have to go to a bank branch, do a ton of paperwork, and speak with a banker just to invest a couple hundred dollars. And each customer would have to do this every time they wanted to invest. Archaic, to say the least. So the team began working on ways to take the banker out of the equation and facilitate investing through the app.

We then gave the improved app to our same hundred-person sample, encouraged them to use it, and studied their behaviors. Sure enough, the lower barrier to invest via the app made them 80 percent more likely to invest money versus customers who were limited to a banker at a branch. Hard to argue with those numbers.

The purpose of Seed 3 experimentation is to validate:

-

WHETHER WE HAVE A SCALABLE BUSINESS MODEL: This involves acquiring customers and delighting them (in B2C models, this should be 100 to 500 customers; in B2B models it should be 1 to 3).

-

WHICH METRICS ARE MOST IMPORTANT TO THE BUSINESS MODEL: For any given business, there could be dozens of trackable metrics. The focus at this stage should be to discover and begin to improve the three to five metrics that drive the core of your business. For example, for a particular e-commerce business, it could be variable production cost per unit, customer acquisition cost, inventory turnover ratio, cash conversion cycle, and production throughput time.

-

WHICH OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS WILL BE THE MOST DIFFICULT: Before we graduate from the seed stage into building and scaling, we need to have a read on which obstacles will be the most challenging as we build the startup. Are there operational hurdles like returns or fulfillment? Legal complexities like varying laws across states? Or perhaps this startup will face regulatory challenges if you try to build it inside the enterprise (which might suggest it would be easier to spin it out as its own entity).

KEEP POUNDING THE DOUGH

Remember that Validation isn’t a one-shot deal, nor is it linear. It’s an iterative process to test ideas quickly and inexpensively and to reveal both flaws and strengths. It gives cofounders the tools to test the most critical assumptions they have about the customer’s problem, the solution, and the business model. It ensures rigorous examination of biases and uncovers the commercial truth of a startup.

In this chapter, we laid it all out step-by-step, but in practice it’s not so clean. Throughout Validation, teams shift their focus from problem to solution to business model to customers, revisiting assumptions across all three categories as they progress.

So if the process isn’t linear, why bother separating one stage from another? Especially since that’s not how it’s done in the “real world.”

Think about an eighteen-year-old high school graduate who wants to become a doctor. Before she can start writing prescriptions or even land a residency at a hospital, she’s got to learn the building blocks: cells, biochemistry, physiology. In order to fix what’s wrong with her patients, she needs to understand how they work from the inside out, and in great detail. At eighteen, she’s got the drive and the talent, but she doesn’t have the knowledge. She’s a beginner. And only after she’s polished off her undergraduate degree, four years of med school, and another three in residency and fellowship can she legally and confidently use that little rubber hammer to bonk your knees.

Similarly, all our partners are beginners when they first start Validation. And beginners need structure, trustworthy procedures, and repetition. They need to watch the dough rise, then punch it down. Watch it rise again, then punch it down. All in the name of making the idea stronger.

When the idea has graduated from all three stages of seed, it’s ready to head out into the world as a baby startup at the Series A stage. There’s still no guarantee it will become your next $1 billion business, but by progressing through the seed stage and learning through cheap, fast, productive failure, you’ve eliminated or corrected the biggest errors in your original vision, and your odds for success continue to rise.

We’ve introduced the entrepreneurship side of the Growth OS; this is the part of management that determines what work to do and how. Now it’s time to shift our focus and meet the venture capital side. Enterprise entrepreneurs cannot thrive on their own; they need investors to fund their work and champions to clear roadblocks and offer advice. We call this guiding body the Growth Board.

VALIDATION AT WORK IN A NONPROFIT: CHILDREN’S CANCER ASSOCIATION

Children’s Cancer Association (CCA) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to create transformative moments of joy for kids who are facing cancer and other serious illnesses and their families. All their programs are free of charge and focus on music, friendship, nature, and community support; everything that is important to healthy kids and their families, and become exponentially more important once they receive a serious diagnosis.

Founder Regina Ellis created CCA more than twenty-two years ago after her daughter Alexandra died of cancer when she was only five and a half years old. Regina set out to create a new organization that would position joy as best practice in pediatric health care environments across the nation. Bionic connected to CCA through a former partner of ours who is the organization’s founding board chair. She believed that CCA, with its innovative tenets, would benefit from formalizing their methodologies and deepening their processes.

“As a purpose-driven organization, we have strong, entrepreneurial roots,” says Ellis. “We run CCA more like a startup or business than a traditional nonprofit. Our partnership with Bionic was an extraordinary opportunity to strengthen our operating capabilities and embed a new innovation mind-set at a time of significant organizational growth.”

The cross-functional CCA internal team decided to focus their efforts on teen patients. The organization’s hospital partners had been consistently reporting that their teens were struggling, which just makes sense; teens experience serious illness in a specific and challenging way. They have a sense of their own mortality and they understand the gravity of a cancer diagnosis in a way that younger kids simply can’t grasp. They’re already coping with the emotional, hormonal, and behavioral health issues that come with being a healthy teenager; add a life-threatening diagnosis on top of that and the need for support and community becomes even more important. Teens have also sometimes felt they were “too cool” or had outgrown CCA’s core programs, which focus on music, mentoring, nature retreats, and family financial support. To challenge this, the organization chose to use Validation to craft a tailored program for teens.

THEY STARTED WITH TWO HYPOTHESES

-

Seriously ill teens have a need to connect with their peers on their own terms.

-

Seriously ill teens have a need for purposefulness, skill building, and learning.

PROPOSED SOLUTIONS INCLUDED

-

Offering individual music lessons in the hospital (since teens are interested in skill building)

-

Coordinating group music lessons (which have the potential to foster peer connection)

-

Creating photography classes, makeup tutorials, craft workshops, or other skill-building instruction (for those who aren’t interested in music)

-

Organize a trip to an “escape the room” experience as a way to get out of the hospital environment (in case teens just want to be left alone to rest and recover while in the hospital itself)

SEED 1 TESTING

The CCA team posted flyers in the hospitals with sign-up sheets for the proposed teen programs, such as music lessons, photography, knitting, and makeup tutorials. They also went room to room and asked kids if they wanted to sign up, or if they wanted to just take a flier and think about it. Lastly, the team created a website where kids could sign up for programs as well.

The response? Deafening silence. They realized one of their core assumptions was that teens wanted to connect on their own terms. Yet their first round of experiments didn’t test that assumption.

So CCA decided to solicit some direct input. They gave their teen patients the option to participate in what was basically a design-thinking workshop, a forum for offering suggestions on programs they actually wanted and needed. The hope was that attendees might have recommendations that could help shape the next round of proposed solutions.

SEED 2 TESTING

After that first meeting in November 2017, CCA realized that these forums could be the very solution that teens were hungry for: a way to connect with their peers. Co-creating programming might be a way for these young people to give back and feel a sense of purpose. These groups also helped the organization better understand the needs of kids who have dealt with extended hospital stays, serious illness, and an awareness of their potential mortality.

And so CCA’s Young Adult Alliance was born. In March 2018, CCA hosted their second teen meeting, packed with icebreakers, brainstorming, the sharing of personal stories, advisory sessions on potential programs, and more. The attendees gave input on ideas generated by CCA staff, and also offered up ideas of their own.

SEED 3 AND BEYOND

Only now that they have a sense of the customer problem and solution is CCA considering the “business model,” which in their case means raising third-party donations.

“Rather than going out and fund-raising and then spending a ton of money to launch a program that we haven’t fully vetted or validated, the Validation process has helped and indeed required us to be more intentional,” explains Abby Guyer, CCA’s former vice president of brand.

CCA leadership believes the Growth OS has helped them take innovation out of the boardroom and embed it across the organization. They’ve started to see assumption-questioning and experimentation-focused thinking bubble up in meetings, even around day-to-day work. Employees at every level are asking themselves, How do I articulate my assumption? Then, how do I test against it before I act, and certainly before I spend money against it? As a nonprofit, CCA believes they have a responsibility to be good stewards of the money that donors entrust to them, and Validation helps them be sure they’re testing before they invest.

“I think it would’ve been a missed learning opportunity if every experiment we conducted knocked it out of the park,” Guyer told us. “Now we’re learning how to stop focusing on our needs, not to take it personally if an idea doesn’t resonate, and instead to really think about stakeholders and solutions. We’re asking ourselves constantly, ‘Is it a vitamin, or is it a painkiller?’ ”

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.