7

INVEST LIKE A VC

Most people incorrectly assume that disruptive ideas are the exclusive domain of startups, and that bigger, traditional organizations just lumber along refining their existing offerings. But plenty of long-standing companies employ talented intrapreneurs who dream up and hack together leading-edge ideas. The problem is that those creators frequently have no viable way to get their products into market.

They must first wring money out of budgets, which are allocated annually, so they’ll have to wait until the next planning cycle. And then they’ll have to compete for funding on an ROI basis, even though the ROI of their new idea is unknowable at this point. Then they’ll have to pitch to their peers in the relevant business units, convince marketing to get on board, persuade or distract compliance, and cajole legal. If any of those folks push back, express doubt, or refuse to support an idea, it can die a slow and silent death before senior leadership even gets a whiff of it. And if their new idea competes with an existing moneymaker for the company (even if their solution is substantially better!), they literally don’t stand a chance. No one in management is incentivized to disrupt the core.

Sure, you can probably think of a time when someone moved fast and did something big. Someone with lots of political capital, institutional knowledge, and a little bit of air cover can achieve something big…once. But they can’t do it over and over, and neither can other people who may have the right idea but not the other skills to navigate all the red tape. The power to say yes to disruptive ideas resides at the top, while most everyone else is actively mitigating risk, because that is what they’re being paid to do.

No, the problem isn’t a lack of ideas. And it’s not that the CEO and senior leaders aren’t open to those ideas. The problem is the lack of a venue for those ideas to be heard directly by leadership, and the lack of permission for teams to pursue them.

This is where the Growth Board comes in.

OPERATE LIKE AN EXECUTIVE, CREATE LIKE A VC

Remember waaaay back in chapter 1 when we talked about the Growth OS as a dual-engine management machine, driven by both in-house entrepreneurs and in-house VCs? So far we’ve focused on the processes in-house entrepreneurs (Discovery team members and OA cofounders) use to identify and vet potential bets. Now we’ll start looking at how those bets get approved, funded, and supported using an investment and decision-making group that we call the Growth Board.

The origin of our Growth Board model is one of those stories that could only happen by working and co-creating alongside our customers. It was early in my work at GE; Eric Ries and I were giving keynotes on the Lean Startup framework and the growth leader mind-sets, respectively, for the Oil & Gas division, which was led by CEO Lorenzo Simonelli. I finished my talk and had just taken a seat at a table in the back of the room when Simonelli joined me to ask a pressing question: “David, I’ve been thinking. I’m spending $700 million on over five hundred different programs, and I know they aren’t all viable. How do I get half that money back? How do I get the teams to tell me the commercial truth?”

Without missing a beat, I realized the venture capital funding model of staged investments for startups along the seed/launch (Series A–B)/grow (Series C+) framework could apply to enterprise growth investments. The framework is one that requires teams to show evidence at each stage that is appropriate for the size of check they are requesting.

For the check-writers, this model allows them to invest small amounts when the risk is very high, and to continue investing in the work as the company shows progress. In essence, it derisks the venture. Rather than allocate the full funding for each project when it kicks off and have the teams take that funding for granted since it was “budgeted,” this approach instills the kind of scrappiness and sense of urgency that startups face every day. It kills zombies—projects that deserve to be shut down yet continue to live on—and gives oxygen to the ideas that are commercially true.

As I finished sketching out this model on a piece of scrap paper, Simonelli tore the drawing off the tablecloth and rushed it over to his leadership team, announcing, “Let’s build this.”

“We had a fundamental challenge in that funding allocation was done by engineering, and it was basically budgeted out each year based on the status quo,” Simonelli told us recently. “There were a number of projects that had been going on for years and continued to be allocated millions of dollars even though they didn’t really have an outcome in mind. So instead we brought the new product budgets down to zero and built them back from the ground up, reserving a quarter of the funds for the Growth Board to grant based on milestones.”

He continued, “What it allowed us to do was stop things early on in the process if they didn’t make sense. And we became more disciplined in the governance of capital allocation. It was a very difficult process to begin with because you have to move away from an entitlement mind-set. We found that, despite being really interesting, many of the projects weren’t based on real assumptions.”

Eric Gebhardt, the then chief technology officer of Oil & Gas, quickly became our partner in piloting the first iteration of Growth Boards. “As teams got on board, some of the biggest skeptics turned into some of the biggest zealots because they realized now that they could take on extra risk; they could go ahead and test bold hypotheses. I would say that we’ve always been very good at product development. This gave us the freedom to become great at it.”

Three years after Simonelli installed a Growth Board at GE Oil & Gas, he asked his team to run the numbers on the speed and cost of new products introductions (NPIs) within the company. The number of days it took to introduce a new product had decreased by 70 percent over the cohort data from just three years prior, and the cost had decreased by over 80 percent. Bad ideas died quickly (and cheaply) while good ideas grew.

The recognition that startup tactics alone will never move the needle inside large enterprises—that startups need the funding mechanism of venture capital to balance out the growth ecosystem—was the crucial aha moment for me and my early Bionic collaborators, setting our young company on the path to build out the entire Growth OS.

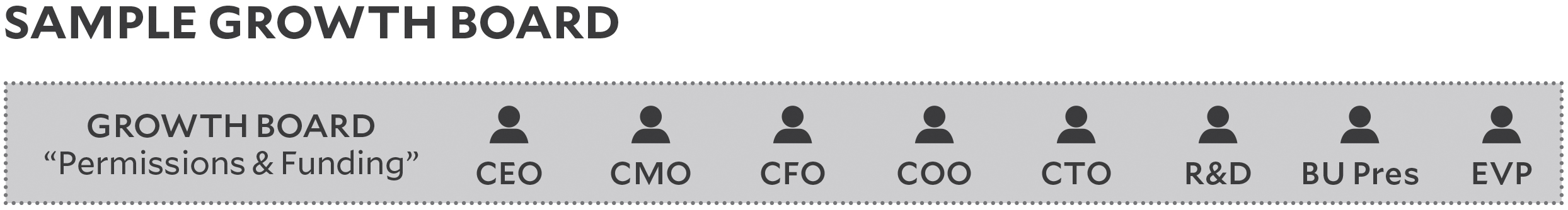

The Growth Board is a body of senior leaders that typically includes the CEO, CFO, CMO, and other key executives. The Growth Board gives the teams building the startups the venue to be heard and funded, and to understand how their ideas might fit into the strategic objectives of the company. Members of the board act as internal venture capitalists, deciding how to allocate funding to early-stage ideas, consolidating learning from various initiatives, providing the permissions and boundaries within which the teams can create, and removing roadblocks when necessary. The focus of the board is to set growth goals, manage the portfolio of bets that are underway, and make investment and resource decisions to reach those goals.

This may be the point where you interject that you already have an investment committee in your organization. We totally understand how this may sound similar. But as you’ll see, the Growth Board is something altogether different.

WHY CULTIVATE A LARGE PORTFOLIO OF BETS?

When established corporations consider new business ventures, they do so through enterprise lenses, often thinking, “We’ll need to shell out $50 million just to get going.” Those ventures are evaluated through market research and risk assessments in known markets, but even if they seem like winners in theory, they can still tank in practice. Which means that the C-level leaders who have been tapped to sit on their respective Growth Boards often resist the “large portfolio of bets” thesis. They envision shelling out billions to fund ideas that may fail spectacularly (or worse, never die at all, becoming zombies that suck up cash and resources yet never show anything for it).

So first, we introduce them to the Validation methodology we walked you through in the last chapter. And then we talk about the (surprisingly small) amount of capital the Validation process takes, and talk diversification.

When most execs hear the word portfolio, they immediately think “stocks.” Which is understandable, since the idea of a diversified portfolio was first introduced to manage risk in investments in the stock market. But in the venture capital world, “portfolio theory” has a different connotation. Returns on venture capital are far too erratic to follow a traditional bell curve. Instead, they follow highly concentrated “power-law” distributions: In a typical VC fund, 65 percent of investments lose money, 25 percent provide a moderate return, and only 10 percent actually make the big bucks, according to Correlation Ventures, a VC fund.1 In fact, the top 6 percent of VC investments appear to account for 60 percent of total profits, according to Horsley Bridge, a limited partner in many top VC funds.2

Let that sink in for a minute. Then consider how incredibly unlikely it is that you’d stumble on a venture that falls within that tiny 6 percent if you only invest in ten startups (let alone that one “Hail Mary” idea you were thinking of launching with tens of millions of dollars).

Because there is so little we know about new commercial spaces, we hedge risk by trying a lot of things. But we try them as cheaply as possible. Diversification in venture capital, therefore, should be geared toward learning—increasing the odds that those rare winners might be in the portfolio at all—rather than just optimizing toward financial outcomes of a single bet. Remember “ladders to the moon” from chapter 4? A portfolio of bets allows you to learn asynchronously and asymmetrically, increasing your chances of hitting it out of the ballpark. In enterprises, we see every project being pressed to deliver financial success; in VCs, we assume most investments—most new startups—will be duds, so we place a lot of bets.

This feels really different. We get that. Embracing volatility can be deeply uncomfortable for executives who have built their careers by being the best at optimizing and decreasing the risk of operations.

But here’s why we’re taking this approach: Applying traditional portfolio theory to enterprise growth efforts can be the kiss of death for large, established companies. Robert H. Hayes and William J. Abernathy saw this back in 1980 when they wrote an article titled “Managing Our Way to Economic Decline” for Harvard Business Review. They said:

Originally developed to help balance the overall risk and return of stock and bond portfolios, these principles have been applied increasingly to the creation and management of corporate portfolios—that is, a cluster of companies and product lines assembled through various modes of diversification under a single corporate umbrella. When applied by a remote group of dispassionate experts primarily concerned with finance and control and lacking hands-on experience, the analytic formulas of portfolio theory push managers even further toward an extreme of caution in allocating resources.3

Our point? This kind of dispassionate calculation of ROI for new opportunities will never drive disruptive growth. It’s the right tool for harvesting cash cows or evaluating sustaining innovations in core products. But to create new markets, leverage new enablers, and broaden their aperture on the future of the company, executives have to think beyond business-as-usual financial ratios.

Because success in a world that is unknowable requires three things:

-

A large volume of bets (that allow you to…)

-

Find the right solution

-

At the right time

So what, exactly, will the Growth Board do? And how does it help create and manage this diversified portfolio of bets? Let’s start by defining the GB’s three responsibilities.

THE GROWTH BOARD’S THREE RESPONSIBILITIES

Members of the Growth Board serve as investors, sounding boards, and diplomats. Their purpose is to enable the progress of in-process startups by outlining objectives, providing resources, and clearing roadblocks for the various on-the-ground teams.

Responsibility 1: Set growth goals

The first responsibility of a Growth Board is to define clear growth goals for the company. Those goals typically fall into several buckets:

-

REVENUE: Are we seeking a certain revenue goal, and over what time period? (E.g., $1 billion in new revenue within five years? Three $50 million businesses within three years?) Spoiler alert: Almost all our partners set goals at the beginning of our pilots. And by the end of the pilot, when they really understand what it takes to do this work and what New to Big can do for them, they reset their goals. It’s okay. While it’s important to have a clear target from the beginning, it is just as important to understand that you’ll likely have to change it once you get started.

-

MARKET: Do we want to leverage the Growth OS to go after core, adjacent, or transformational opportunities? How can those opportunities support the organization’s strategic objectives? Are we looking to enter a specific new market? Which market forces are having the greatest impact on our company?

-

ORGANIC/INORGANIC: Do we want to focus on organic bets (ideas created inside the company), inorganic (VC investments in outside startups and/or mergers and acquisitions), or both? If both, what percentage of our resources and effort are we willing to allocate to each? (This strategy is strongly connected to the size and time frame of your growth goals.)

-

TIME HORIZON: When considering technologies or enablers, some are near-term and some are much further out; how far into the future do we want teams to look? (How patient or impatient can you be?) And are there areas, business models, or customer segments that the company won’t pursue?

Responsibility 2: Manage portfolio health

In order to effectively manage its portfolio, the Growth Board needs to be able to measure its health. But remember that traditional Big to Bigger metrics like IRR don’t apply here! (Nor do stock market portfolio metrics like the Sharpe ratio or alpha.) Instead, we’ve defined four components that together create a snapshot of the portfolio’s health: Focus, Size, Quality, and Velocity.

-

FOCUS speaks to the alignment with growth goals (core, adjacent, disruptive). As in, are all bets in the portfolio oriented toward the growth goals the board has previously defined for this work?

-

SIZE measures whether the portfolio has enough bets to hit its goals. Are the number of OAs and number of ideas within each OA large enough to overcome the odds of failure among the seeded startups?

-

QUALITY assesses the quality of the teams, the OAs, and strength of the proprietary gifts being leveraged, among others. This metric helps us determine if course-correction is needed from a staffing or investment thesis perspective.

-

VELOCITY measures the speed that the startups you have bet on are moving through the stages of the investment funnel, and the frequency that the funnel gets refilled with new ideas (i.e., new startups).

“We developed a growth thesis for each one of the business [units],” said Eric Gebhardt, former CTO for GE’s Oil & Gas division. As Oil & Gas tracked startups in their portfolio, they consistently asked, “What phase is it in? Is it in seed? Is it in launch? Is it in grow? Where do we need to seed new things? Does it still fit the growth thesis? Are we balanced in our portfolio?”

Responsibility 3: Enable growth capability

The Growth Board must model the Growth OS mind-sets (as discussed in chapter 4) and give permission for teams to tell the commercial truth. They must understand and remove roadblocks inside the organization. And they must identify and encourage the right talent to drive New to Big growth. Ultimately, they enable growth capability both through how they talk about the work being done, and through the actions they take to support the people who are executing that work. Here’s an example of what that looks like in practice:

When Bionic first started working with Tyco in 2013, CEO George Oliver was skeptical. We were brought in by the chief innovation officer, who was frustrated by the lack of a pipeline for new endeavors. He assumed Bionic would facilitate the funding process. Oliver needed his arm twisted, and sat grudgingly through the first Growth Board meeting. But by the second meeting, he was starting to see the light, and by the third he was a true believer.

At that third meeting, an OA cofounder was scheduled to present, and she was absolutely terrified. Her OA had initially appeared to have tremendous momentum, but once her team dug deeper, it proved to be a dud. Her task that day was to tell the Growth Board that the OA had been invalidated, and that the company should stop funding it. We coached her and encouraged her and reminded her that telling the commercial truth about the project was gospel, but she was still a mess. Which is understandable, since she had to step into a giant wood-paneled boardroom packed with C-level execs and explain that her team had bet on this project and lost.

She gave her presentation honestly and humbly that day. And on the spot, Oliver decided to promote her, because he understood how much courage it took to show that level of candor. That was the strongest signal he could give that he supported the Growth OS, through both success and failure. By doing that—especially around an opportunity that had so much early momentum behind it—he told all of Tyco that it was okay to try and fail. With his actions he told his entire company that they had permission to experiment, even if the process led them to some dead ends, because dead ends that were reached quickly and without huge investments saved them a ton of money and let them refocus their effort on the ideas that have potential.

Now that we’ve set the three responsibilities of the Growth Board, allow us to introduce two essential board members: the CEO and the External Venture Partner (EVP).

THE CEO MUST OWN THE GROWTH BOARD

Because New to Big growth requires leadership and teams to challenge age-old practices, it can only succeed if that change is led by senior leaders, and the CEO in particular. This is nonnegotiable.

Adopting New to Big mind-sets and investment criteria in any organization is challenging. It requires conviction that this is the only way to secure the company’s future. It needs the permission to take risks that only the CEO and senior leadership can grant. If the CEO doesn’t personally drive New to Big growth, guess what? No one else will, either. No news there.

We learned this lesson the hard way. In the past, we worked with partners where the CEO believed they could delegate growth. In each case, this attitude sent a clear message to the company: “This is something I want you all to do, but I am busy with more important things.”

You can imagine how well those efforts turned out. Because the truth is, the leadership is at least half the reason big organizations can’t grow at will. Every mind-set we unpacked in chapter 4 is the opposite of how top execs have been trained to think. They got to where they are by being right! By derisking! By following decades of best practices! By applying rigorous financial metrics to any new investment! They are expert operators! And now they have to learn to be creators, too?

If they want growth, yes.

Maybe this is you. (If so, we hope you’ll finish the book instead of turning it into a doorstop right about now.) Or maybe this is your boss, or your boss’s boss. (If that’s the case, we hope you can extend them a bit of empathy—the rules are changing so quickly and they have to navigate such strange waters here.)

In either case, learning to be ambidextrous in your leadership—to be both an operator and a creator—is crucial for your continued success. Because it is no longer good enough to be a good leader; the twenty-first-century CEO must be a growth leader, and that starts with owning the Growth Board. Full stop.

BUILDING OUT THE TEAM

Now that we have the CEO on board, it’s time to flesh out the rest of the Growth Board. The ideal size is between six and eight executives, with a mix of commercial and financial execs (technology, finance, legal, etc.) who have the moral, financial, and strategic authority to make Growth Board decisions. The goal is to assemble a board large enough to represent a range of perspectives, but small enough to be nimble and decisive.

In our work with corporations, we also invite ourselves onto the Growth Board. (Hi.) Because to do this right, you need an outsider to help you vet ideas. Adam Grant shares a story in his book Originals that explains why.4

One of his former doctoral students, Justin Berg, did some research on people’s ability to predict the success of new ideas. In one series of experiments, Berg, who is now on the faculty at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, asked circus artists (yes, circus artists—stay with us) to assess how likely their performances would succeed with audiences.

It turns out that the creators themselves were terrible at predicting the success of their own acts. They were too close to the ideas. So Berg gathered up some experienced circus managers and showed them videos of these new acts, and he asked the managers to predict which would be most loved by audiences. And in his research, he found that the managers weren’t very good at idea selection, either. They had a prototype in their head of what they thought a good circus act would look like, and these acts just didn’t fit that prototype.

But Berg wasn’t done: He ran one more experiment.

He asked circus artists to assess acts that weren’t their own—that is, he got fellow creators to weigh in as outsiders and judge the potential acts. And you know what? They were great at it. Their predictions were closest to the audience’s actual feedback. Why? Because, Grant points out, creators tend to be too positive about their own ideas. And managers are too negative; they are trying to evaluate if the idea fits into their vision of what success looks like. But peer creators—outsiders—are more likely to look at an unusual idea and say, “This is totally different from anything I’ve seen, but it just might work.” And they’re also equally willing to say, “Nope, this is really bad. Go back to the drawing board and try again.”

Bionic has assembled and sat on over a hundred Growth Board meetings over the years, and we’ve learned the hard way that each board absolutely must have an outsider’s perspective. So we embed an External Venture Partner (EVP) on the Growth Board to bring an outside creator’s perspective on all potential startup bets.

The EVP role is crucial for a successful Growth Board specifically because the EVP is an outsider to the company. Research shows that outsiders can be more creative because they are not constrained by traditional thinking and existing solutions.5 They also give independent input and can de-politicize interactions because they have no existing bias toward the situation and essentially no stake in its outcome. To overcome cognitive—and institutional—biases, a knowledgeable, objective outsider is essential.

As you assemble your own Growth Board, look to your corporate board for an experienced entrepreneur and early-stage investor who could play the EVP role. Or you might look to your local startup ecosystem for an investor you could recruit to play this role. (Of course, you could also call us.) But the outsider role is the other nonnegotiable member of a successful Growth Board.

THE EVP BRINGS THE OUTSIDE IN

Allow us to be blunt: Executives are stubborn. Many of them have decades of experience across multiple industries, are used to making multimillion-dollar decisions every day, and believe they’ve pretty much seen it all. They are seasoned and wise, but also headstrong and intractable. Teaching them to transform how they think about new business endeavors can be arduous. Painful, even.

Luckily, they also love a good challenge. Rerouting old behaviors and beliefs is crucial to the Growth Board’s success, so we look to the EVP to counsel the other board members, give them a healthy dose of entrepreneurial perspective, and often provide one-on-one coaching.

The EVP also works to steer members away from ingrained leadership behaviors that might quash the entrepreneurial process. They help execs learn to bring a beginner’s mind to the table, asking questions instead of making statements and jettisoning calcified institutional biases. Every Growth Board needs a member who can examine the evidence with a view unclouded by internal politics and who can keep the group accountable for this new way of working. Without an outsider, it’s hard to make the real shift from venture portfolio theory to practice.

The EVP must be someone who has been deeply embedded in the startup world, and therefore has a clear view of the business landscape outside the company’s walls. Look for someone with experience as an early-stage investor and who has had at least one success and one failure as an entrepreneur. They bring context for new technologies, reconnaissance from the startup trenches, and coaching when execs stray away from New to Big mind-sets. And to the point about circus artists, they have been in both the startup “tent” as entrepreneurs and the early-stage investing “tent” long enough to be really good at evaluating new ideas.

INTRODUCING EXECUTIVE SPONSORS

Last, but certainly not least, you’ll need Executive Sponsors. These key players don’t usually sit on the Growth Board, but they play a vital role in bridging the Validation work of the cofounders and the investment work of the Growth Board. Their role is to push cofounder thinking, ensure the rigor of Validation, and remove roadblocks.

You might think of the Exec Sponsor as the partner at a VC firm who led the investment in a specific startup. While the full VC partnership (the Growth Board) voted to make the investment, the individual partner has the closest involvement with the team. They are the one the team calls when disaster strikes, or when they have surprising data that could lead to a pivot, or when they need help finding a subject-matter expert to advise them. And when it’s time for the startup to raise another round of financing, they come back to the full VC partnership, but it’s the individual partner who knows the most about the startup during the closed-door deliberations.

Early-stage investor Chris Sacca was well-known for only investing in startups where he knew he could affect the outcome in some way. While he was well aware that startups were inherently risky, “I knew that, for our companies, when stuff started going sideways, I could show up and be helpful. I could start to diagnose the problem. I could bring in better people to hire. I could help streamline the product road map. I could land their first couple of customers,” he told us recently. As a result, he felt that “while success may be lucky, it’s not an accident.” That’s a perfect way to think about the role of the Executive Sponsor.

In the context of an enterprise, the Executive Sponsor also becomes a hybrid startup board member and coach for the three OA cofounders, approving funding for individual Validation experiments, ensuring those experiments are sound, and confirming that team members are making evidence-based decisions as they progress.

Here’s an example of the power of a great Exec Sponsor. At one of our partner companies, a team had been working on a new haircare product for several years. They had identified a new use for an existing technology that would solve a real, painful customer need, and they wanted to launch this new product under one of their (beloved) existing brands. The company assigned a very senior R&D exec to sponsor the team, and being from R&D, the sponsor was less invested in any specific brand.

Using the Growth OS Validation methodology, the team quickly learned that customers did indeed want to solve this problem, but they wanted a solution that was both health-oriented (which their existing brand could offer) and beauty-oriented (which it could not). The team quickly realized they had no choice: They had to create a new brand to launch this new product successfully. But they were concerned that the Growth Board wouldn’t like this answer. The Exec Sponsor allayed their fears, confirming that the commercial truth mattered more than any brand bias, and he supported their recommendation to the Growth Board to go ahead with this solution only if they did so under a new brand.

LAUNCHING A GROWTH BOARD

Now that you’ve got your roster of players, what are the rules of the game? Based on our experience across dozens of Growth Boards, we’ve developed a few principles to help you get up and running.

First Things First

-

NO ATTENDANCE, NO VOTE: Only Growth Board members in attendance may vote; no delegates/proxies allowed.

-

FREQUENT MEETINGS: Growth Boards should meet at least once a quarter (as the number of OA teams increases, a subgroup may also meet more frequently).

-

FACT-BASED: Growth Boards must overcome their biases about what the “right” answer is and kill any inclination to support pet projects. Instead they must use the evidence uncovered by teams to make decisions.

-

ACTION-ORIENTED: Growth Boards must make go/no-go decisions at the meeting. Requests for follow-ups, additional opinions, etc., should be the exception, not the rule.

-

REAL-TIME FEEDBACK: OA teams should receive Growth Board decisions immediately following the Growth Board meeting; no keeping them in limbo.

Ground Rules

It’s not easy to be the CEO of a multibillion-dollar company and hold back opinions in meetings. We get it. But the Growth OS requires everyone on the Growth Board to embrace a new style of leadership that’s rooted in the practice of asking questions. The ground rules for board members employing question-based leadership are:

-

Ask questions of the teams, rather than state opinions

-

Ask questions appropriate to the stage of development

-

Focus on the evidence the teams present

-

Remain open to learning at all times

-

Commit to trusting the teams and letting the evidence guide decisions

Addressing Mechanics and Cost

Once Growth Board members have made their peace with asking questions instead of assuming they already have the answers, they need to wrap their heads around which questions to ask. At the seed stage, those questions are not “What’s the ROI?” “What are the margins?” or “What market share can we capture?” They’re not questions that orbit RONA, ROIC, and IRR. Why not? Because those answers are unknowable this early and will remain so for a few years. Any attempt to answer them would produce intellectually dishonest results.

Instead we equip them with a list of questions that are knowable at each stage of a solution’s development: At the earliest stages, those questions include “What are the most critical assumptions to test next?” “Tell me about the most passionate community or audience you’ve found for this idea,” and “Who are the top competitors for this solution?”

As bets move through the Validation process, the questions shift more toward “What are the customer’s top three priorities?” “What’s the initial business model for this solution?” “What are the four or five inputs for that business model (LTV,*1 CAC,*2 etc.)?” and “What adjacencies make this a scalable business?”

While the Growth Board is mulling over those questions, it’s important to circle back to mechanics. Board members know they’ll be guiding the funding process, but often need reminding that their guidance won’t be in the form of signing million-dollar checks. Not yet, anyway. At first, they’ll cut their teeth making smaller investments in stages. Which can be counterintuitive to executives who are used to handing out massive pots of money, crossing their fingers, and waiting a couple of years to see how it all pans out. It’s easier for most executives to make a $10 million decision than a $100,000 decision.

Now they need to adjust to smaller risks in larger batches. They need to allot less money, but be prepared to see quick-turn, slightly messy results and make high-level judgment calls based on the evidence collected. They are empowered to cease funding if the OA teams come back with decidedly dismal results, but also required to hold any results to a new standard. When the team comes back in twelve or sixteen weeks to present their findings, those findings will not be slickly packaged or thoroughly derisked. But they will reveal evidence-based learning about the customer need and whether a proposed solution actually meets it. Growth Board members must be willing to trust the teams and trust the process.

Since the cost of being wrong is much lower in this management approach, many board members adjust quickly—sometimes too quickly—to the new paradigm. Making the switch from slow and costly to quick and cheap can be a little heady. It’s easy to get excited about individual ideas and lose sight of the overarching Total Addressable Problem (TAP).

Here’s what that might look like: A few years back, a Bionic EVP was working with a partner who got swept up in doing dozens of experiments on a fleet of diverse solutions. She had to rein in the process, saying, “It’s fantastic that all these tests are yielding valuable learning, but what’s the larger goal? What are they telling us about the bigger customer problem we’re looking to solve?”

The team didn’t really know. They were so thrilled by this quick-turn, high-yield system that they had lost sight of the higher goal. They felt like they were making progress, since they were getting a steady stream of tangible results, but they’d forgotten what they wanted to make progress toward.

The Growth Board stepped back and consolidated their learning about what constituted the biggest customer pain point. Remember that the teams were meant to be exploring a brand-new solution to a high-level problem in a way that would create an entirely new market. One that the company would own. Entirely. With that in mind, the EVP helped them reframe their OA, and a growth thesis emerged.

The company was able to say, “We’re not going to market as a product manufacturer. We’re going to market as the way to help our customers solve this massive problem. We’re going to address this problem for a customer who is resource-constrained: one who has no room for an appliance, no time to solve the problem themselves, and no money to outsource the labor. We’re going to create mechanisms that solve the problem in a way that is safe for their families and sustainable for the environment.”

Working through mechanics and cost with the Growth Board is a journey. First there’s hesitation, then understanding, then buy-in around the Growth OS methodology, then giddy excitement over snowballing team results, then reframing, and finally a crystallization of the larger growth thesis. It’s a powerful, galvanizing experience for the Growth Board. They realize they’re not just hammering away at new products to take to market; they’re refining a vision for how they can address massive, ongoing consumer needs and, in doing so, build the future of the company.

Ready to observe an actual Growth Board meeting? Let’s crack open that door and see what they’re up to.

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION!

We’ve covered all the pieces: the members, the mechanics, the methodology, and the long-term vision for the Growth Board. Now it’s time to run through what these meetings look like. (Remember: This is not your typical investment committee meeting.)

Growth Board meetings are held quarterly, and typically take a half day. The primary purpose of the meeting is for the board to talk to the OA teams to understand what they are learning about the problems they are trying to solve, identify what the Growth Board can be doing to help them move faster, and make decisions for the portfolio going forward. The cadence for each team presentation is “Here’s our hypothesis. We’re going to go run these experiments to see if it’s true. And we’re asking you to tell us if we have permission to go after X or that we need Y to be able to move faster,” rinse, and repeat. The board must then decide if they want to continue investing in the OA.

To kick it off, an OA’s Executive Sponsor will typically spend a few minutes updating the Growth Board before the cofounders give their presentation. This stage-setting is a high-level executive summary: “Here’s what we believe to be true. We’ve had these great insights, we believe X is a great opportunity, we’re learning that Y doesn’t have sufficient potential.” This preps the board for what they’re about to see. (As you likely know, execs like to start with the headline before they dig into details.)

One Growth Board meeting typically includes multiple OA team presentations, so it’s the job of the board’s EVP to keep things moving. Each team is given time to present their findings and for the board to ask questions. Teams may show videos of beachhead customers they’ve interviewed, demos of customers interacting with the prototypes, or mockups of their next stage of development. They may present data from other startups that have tested ideas in the same space, and results from their own experiments week over week. If teams believe a solution to be viable, they need to back that belief with solid findings and be prepared to defend their ask.

(In early Growth Board meetings, every OA team may come and present. But as the volume of bets in an OA increases, only teams that have a specific ask or need the Growth Board’s sign-off to get additional funding and move further down the funnel should be presenting at any given meeting.)

Part of the work of the team, led by the Exec Sponsor, should be tracking the activity in the OA that’s happening outside the company’s walls. Where is funding going? Who are the incumbents and the rising players in the space? As part of their presentations at the Growth Board meeting, the Exec Sponsor and cofounders can request funding for an acquisition to accelerate their velocity within the OA.

Once the team leaders have wrapped up their presentations, the Growth Board and EVP head into closed-door discussion. The board reviews the decisions that need to be made about the various OAs and collects feedback for the teams. They’ll decide whether to continue supporting the OA for another period of time (usually six to twelve months)—whether through funding, acquisitions, permissions, connections, or a combination thereof. And they’ll look at their portfolio metrics and discuss whether they feel confident that their OAs have the volume, velocity, quality, and type of startup bets to achieve their growth goals.

After all OA teams have presented and the decisions have been made, the group will wrap with some self-reflection: How did they show up as a Growth Board? Did they ask the right questions? How could they improve next time?

Speaking of “next time,” it’s worth noting that although all Growth Board meetings follow the same basic format, the dynamics shift depending on how mature the Growth OS is within the organization. The very first Growth Board meeting is awkward and uncomfortable. For everyone. Both board members and OA teams are still on a pretty steep learning curve, so all parties are feeling self-conscious and off-balance. That’s to be expected. (The EVP really drives this first session.)

The second Growth Board meeting—which is typically around the six-month mark—runs a bit smoother. The teams have acclimated to their workflow and are starting to see some validation of their hypotheses. A few ideas may have already passed through Seed 1, or even Seed 2, and potential business models are starting to percolate. A few early front-runner solutions may have been tested using higher-fidelity prototypes.

By the third Growth Board meeting, there’s often a solution making its way through Seed 3 that could be ready for the build stage. A few other ideas that are performing well in Seed 2 are being prepped to start Seed 3. By this point, the Growth Board now understands how to evaluate individual solutions, and while their portfolio may still be fairly small, they can begin to shift focus toward managing portfolio health.

Once the fourth Growth Board meeting rolls around, everyone is actually talking about and collaborating as a single investment body. With larger funding amounts at stake, the Growth Board discussion is focused on laying the groundwork for the new businesses ready to jump from the seed stages to the build stage, and the board is understanding the real-world economics of the market they’re in (or about to create). By this point, the EVP is really stepping back from leading the Growth Board through the mechanics of the meeting and is instead acting as a trusted advisor to help them make the right investment decisions and manage the health of their growth portfolio.

REPLACING ONE-OFF WITH ALWAYS ON

Fostering a pro-entrepreneurship environment is one of the biggest and most important challenges Growth Boards face, often even more critical than facilitating funding. It involves providing organizational air-cover and freedom of operation for the OA teams, but also modeling creator mind-sets. Successful Growth Boards drive a high-speed and high-volume pipeline of bets by fostering an open-minded and risk-taking environment, anticipating and resolving roadblocks, providing the necessary resources, and focusing on the right opportunities.

But to make this an always-on capability, the Growth Board and the OA teams need to enlist backup from some key professionals: their human resources team. Because the only way for the Growth OS to become ingrained in the DNA of the company is through people. So let’s talk about people.