9

INSTALL A PERMANENT GROWTH CAPABILITY

So you’ve decided to do this. You believe in the Growth OS model, understand why you need both entrepreneurs and VCs inside your company, and trust that your executives can become ambidextrous leaders. Excellent! Before you begin installing the Growth OS inside your organization, you need to define what success looks like—that is, what do you hope to accomplish by creating an entrepreneurial engine within your organization?

In most cases, the large-scale goals that companies set around innovation fall into one of two categories:

NEW GROWTH: Success here is defined by the number of new businesses that your company launches into market. You want to ramp up growth by introducing innovative, consumer-centric offerings. You want lots of bets, a healthy ROI, and PR-worthy proof that your organization isn’t stuck in stasis.

GROWTH CAPABILITY: Success here is defined as creating systems, tools, and structures that enable portfolio-building to happen on an ongoing basis. You want to empower your organization to create with consumer pain points in mind. You want your executives to become ambidextrous leaders: both operators and creators. And you want your organization to be nimble enough to support both New to Big and Big to Bigger. Because while you’re definitely keen to increase the number of profitable, large businesses that your company launches, your primary goal is building sustainable mechanisms and culture to make that increase repeatable.

Put more bluntly, do you want fish, or do want to learn how to fish?

Spoiler alert: We hope you want to do both. Yes, you need growth, and that should always be the primary driver, but the real value is building the machine that allows you to reliably generate that growth, over and over and over. Sure, you could form a team, spawn a couple dozen groundbreaking ideas, enter a new market, and beta-launch a new offering in the next year. But wouldn’t you rather build a machine that can launch an entire portfolio of offerings every year?

It’s a pretty appealing proposition, but that doesn’t mean everyone in your entire organization will get on board to adopt growth capability from day one. “Let’s pilot this new way of working with a small group for a set amount of time and see what happens!” is much easier to sell than “Let’s change the way our entire multibillion-dollar company works forever and ever!” In no small part because your current setup has been designed and refined to handle its current workload.

The human systems that you have installed within your organization are designed for Big to Bigger work. Your e-commerce platform, sales strategy, and marketing machine are all calibrated for Big to Bigger. Your manufacturing, packing, and logistics systems are engineered for Big to Bigger. And, perhaps most important, the ways your executives think and make decisions foster predictable profitability in a Big to Bigger world. In all likelihood, everything about your company has been constructed to support low-risk, low-variation growth, not disruptive, market-creating, New to Big growth.

As Harvard Business School professors Clayton Christensen and Stephen Kaufman point out in their Resources, Processes, and Priorities (RPP) framework, “the very capabilities that propel an organization to succeed in sustaining circumstances will systematically bungle the best ideas for disruptive growth. An organization’s capabilities become its disabilities when disruption is afoot.”1

Jud Linville, the former CEO of Citi’s credit cards business unit, acknowledged this dichotomy in his advice to leaders considering this way of working: “The first thing is to understand that any organization is going to be resistant at first because you’ve got built-in processes and platforms and people who are hardwired to do things. So understand the resistance, honor the resistance, and then specifically address the resistance.” He continued, “The second piece is, starting early on in the process, determine the different control breakers that prevent your organization from moving fast. Acknowledge and affirm that they’re there to protect your institution at scale. And then communicate very clearly to the organization how the New to Big work will not threaten those controls if you construct the right test kitchen.”

When we think about growth capability, we think about taking all these mechanisms inherent to the organization that are built for Big to Bigger maintenance and objectives, and reconfiguring them in a limited way to make this new, different body of work possible. You’re creating a “test kitchen,” as Linville puts it, that’s dedicated entirely to New to Big development, all the while preparing the systems and culture inside the rest of the organization to repeatedly take any successes and turn them into massive wins. The goal here isn’t the test kitchen itself, but the capability to create new growth on a permanent, ongoing basis.

Whatever your goals may turn out to be, you must make them explicit at the outset of this work. If you’ve got Growth Board members saying, “I want growth and revenue,” and Exec Sponsors saying, “I want capability and learning,” while the promoters are saying, “I want things to go back to the way they were,” you will stall. Creating clarity and agreeing on goals is the single most important thing you can do to set up this work for success.

So with clear goals in hand, you’re ready to install and launch the Growth OS, right? Well, not quite yet. There’s one more key team that needs to be assembled before the discovery and experimentation fun begins.

HOW DO YOU KNOW IF YOU’RE READY TO TRY THIS?

You’re the drummer in a jazz combo, and you’ve recently decided that your current band should switch to a classic rock playlist. You may feel 100 percent ready to kick-start that change, having studied and practiced and scoped out venues and done research proving that playing classic rock will pay better. But if you haven’t discussed the idea with your bandmates, if they have never dabbled in this new-to-them genre, if they love jazz and fear change, you’ve got a bloody, uphill battle ahead of you. It doesn’t mean you won’t convince them, but you might have to spend a long time and a lot of effort getting them on board.

Similarly, if you’re the sole person (or department) in your company who is thrilled at the prospect of bringing in entrepreneurship and VC mechanics to manage new endeavors, you will struggle. It doesn’t mean you won’t succeed, but you might have to spend a long time and a lot of effort laying essential groundwork. And by the time you have enough support, you may be too exhausted to care, much less forge ahead.

So to get a sense of both your and your company’s readiness, ask yourself how many of these statements are true:

-

You’ve read about Lean Startup methodology (probably before you picked up this book).

-

You’ve tried some experiment-based learning yourself, ideally in your current position or at your current company.

-

At least a few of your leaders are vocally excited about incorporating some new innovation strategies and working tactics.

-

You have pockets of startup-like activity within your company, but they lack an organizing framework.

-

You’ve been looking outside the walls of your organization for inspiration and guidance (books, conferences, speakers).

-

You can see the threats to your business from competitors or other outside forces, and your leadership is starting to sense the urgency to act.

-

Bonus: Your organization recently hired a new leader who hails from the startup/technology world (or at least an outsider whose career wasn’t built by rising through ranks at your firm).

If you answered no to more than half those statements, you’ll likely have an uphill battle ahead of you. But don’t despair! Instead of abandoning this work altogether, focus on shoring up key support.

-

Seed some of these ideas at the leadership level by inviting an outsider—veteran VC, serial entrepreneur, academic, or thought leader in this space—to your next offsite or leadership team meeting.

-

Attend conferences to connect with and learn about companies who are leading the way. (And to introduce yourself! This work is far easier when you have peers to support you.)

-

Visit startups in your industry and see how fast they go from concept to product to market, or from feature to beta test. Better yet, bring some of your leadership team with you to help drive home the point that speed beats size when it comes to discovering and validating new ideas.

-

Check out the recommended reading and watching list in the Resources section at the back of this book.

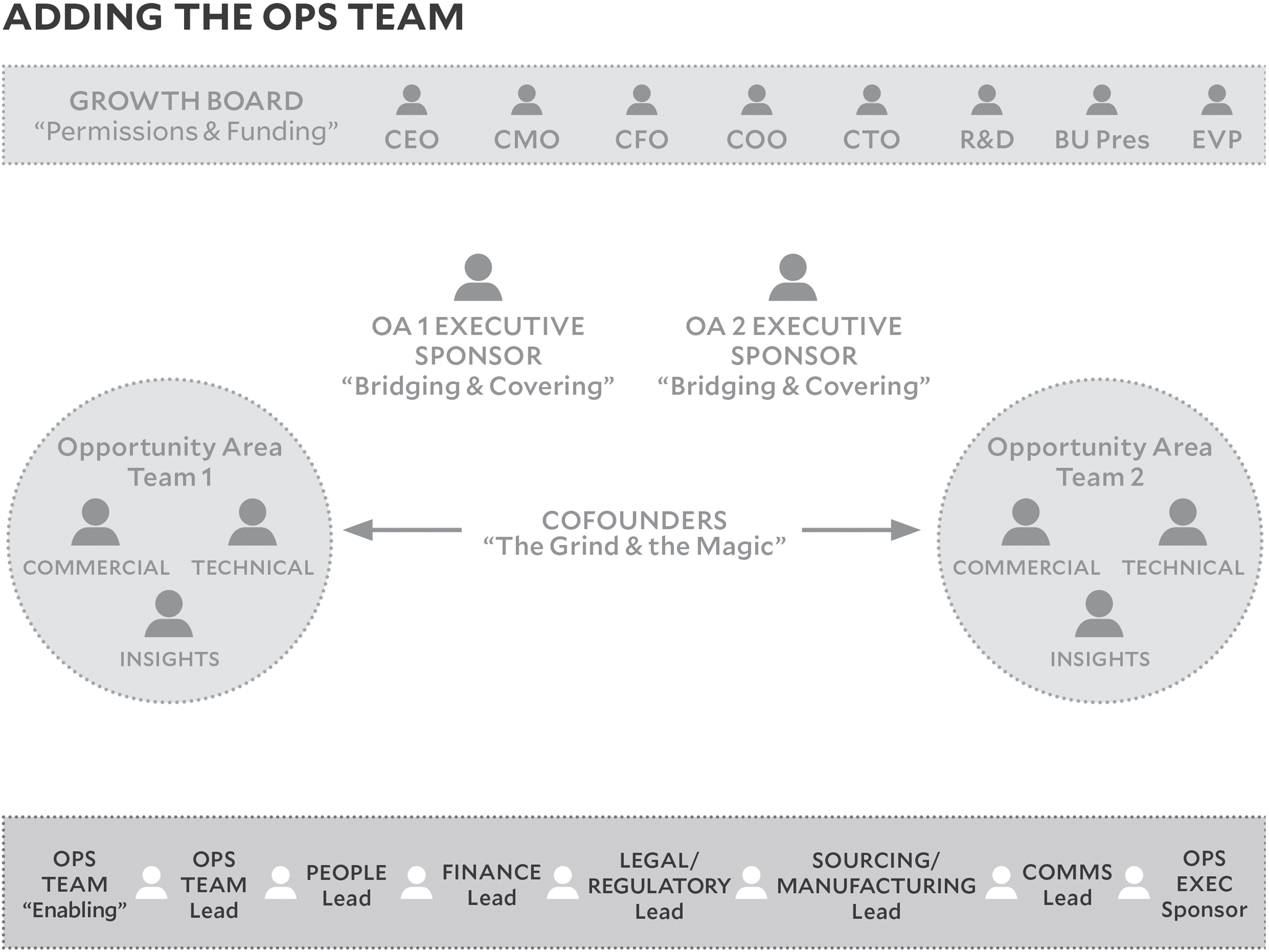

THE OPS TEAM: YOUR DESIGNATED ROADBLOCK BUSTERS

Because Growth OS work is so different from typical corporate work, getting it started and pushing it through can be positively onerous. Frequently, companies lack the infrastructure necessary to support entrepreneurial-style work, and long-standing processes like budget sign-offs and matrix approvals slow everything to a glacial rate. Even if those issues can be bypassed, entire departments of people often stand in the way of this work.

Since New to Big needs to iterate quickly—and since the OA teams will be dedicated to discovering and experimenting with new business opportunities, with no free time to appease promoters or devise infrastructure—you need to create an Operations Team (or Ops Team, the drivers of the Growth OS). This is a group of creative problem-solvers with an aptitude for and interest in innovation. While it will be run by one or two dedicated leaders, you’ll also recruit champions from key functions like legal, marketing, IT/security, finance, and, yes, compliance, folks whose support will grease the wheels. They’re tasked with anticipating who or what will get in the way of this work, and ensuring it doesn’t.

The Ops Team should also have a C-level Exec Sponsor who is dedicated to eliminating any roadblocks to growth work. This person is a bona fide communications ninja, someone who’s been in the company for years, a gregarious type who knows everyone and knows how to get things done. This person is ultimately on the hook for delivering net new growth in the company. They will become the expert on all things New to Big.

The issues the Ops Team will tackle can be everything from bringing senior leaders along to ensure proper staffing of the OAs to proposing solutions to experimentation setbacks. For example, many OA teams choose to create mocked-up websites while testing their solutions. Since the sites are meant to collect data on user behaviors and preferences, some thorny legal issues can crop up. Any site that collects email addresses is required by law to disclose collection in a privacy policy. In California, additional tracking language must be included in the privacy policy to indicate if IP addresses are involved (SurveyMonkey, a tool we frequently deploy, collects IPs) or analytics information from individuals. Since the Ops Team typically includes a liaison from legal, that person can quickly draft boilerplate privacy policy language that works for the experiment and addresses the company’s needs.

This is important: The Ops Team lead and Exec Sponsor should be in place before OA experimentation begins. Don’t try to throw an Ops Team together after you’ve hit the first hiccup; the folks working through Discovery and Validation will need active support from day one. Be proactive, and build this barrier-busting team ahead of time.

Is this team really necessary? Can’t the OA teams or their Exec Sponsors handle the issues and obstacles that crop up? Short answer: No, they cannot. Do not saddle the cofounders with running interference for themselves. If they have to negotiate permission from the support functions, that is all they will ever do. The actual experimentation and learning will get back-burnered and everything will grind to a halt. The Ops Team exists so that the OA teams can do their work quickly and cheaply, without organizational friction.

So before you even start brainstorming OAs and recruiting cofounders, pull together a team of roadblock busters. Their work paves the way to go fast.

OPS TEAM MEMBER TRAITS

Innovative: Isn’t afraid to challenge the status quo, question assumptions, and generate new ideas by looking at issues from multiple angles.

Connector: Takes time to reflect on experiences, learnings, and insights. Spends focused energy processing this information, gaining deeper insights into consumer problems, solution possibilities, and new business models.

Catalyst: Isn’t afraid to challenge the status quo in order to help teams identify and validate disruptive new growth opportunities.

Beacon: Is not only able to work in this iterative and unstructured environment, but also ready to provide support to teams throughout the process.

Mover of Mountains: Ready to identify and remove barriers, even when there is no clear process, and enable teams to reach their objectives.

Evangelist: Embodies the mind-sets of the Growth OS and socializes across the organization with whatever means necessary.

Now you’re ready. You’ve done the prep, you’ve got key people in place on the Growth Board and Ops Team, and your OA cofounders are raring to go. Here’s what the first phase of this new work will look like.

Phase 1: Configure a pilot

The most important piece of advice we can give you as you begin rollout? Start small. It’s possible that you’ll get so much internal pushback that starting small will be your only option, but on the off chance that your entire organization is instantly gung ho, be smart and dial it back. Don’t put a half dozen teams to work on OAs, don’t plan out how this work will be done in two years, and don’t shoehorn people into all levels of Growth OS activities. Give the pilot a nine-month horizon, and keep your focus tight.

The goal of this first phase of work is simply to get everyone situated. Acclimating to new roles doing new work is awkward. You need to get the first group of eager New to Big teams comfortable, engaged, and up to speed before you can even consider taking these processes to the next level. Build one small, self-contained sandbox, and focus on making everyone who’s playing in it feel like they’ve got a handle on things.

To build the sandbox, you’ll need to get the lay of the land. Where will the sandbox be housed? Who will help build it? What resources do you have on hand to support it? In essence, your first steps in creating a pilot for New to Big work will focus on diagnostics and configuration.

PILOT DETAILS

Time frame: 6 to 12 months

CAPABILITY PRIORITIES: DIAGNOSTIC & CONFIGURATION

Align on pilot objectives—Make sure the leadership defines what success looks like.

Establish the Ops Team—Find your barrier busters and go-fast ninjas.

Introduce growth mind-sets and the OS framework—You need everyone working from the same playbook.

Pilot talent and funding models—Remember, do the easy thing that’s good enough!

Identify internal capabilities and gaps—What do you have, and what do you need?

GROWTH PRIORITIES: DISCOVERY AND ESTABLISHMENT OF OAS

Growth Board: Enterprise-level—start with one GB at the top, owned by the CEO.

Ops Team: Enterprise-level—This team will become your internal experts at New to Big.

Opportunity Areas: 1 or 2—Start with just one or two in the pilot; there’s time to expand later.

OA Teams: 2 or 3—Staff a few teams so that your pilot doesn’t get sidetracked if one or two cofounders don’t work out. (You can put more than one team against an OA.)

Focus on defining portfolio goals and metrics—How many bets do we want in motion, and what’s the time horizon we’re driving to?

Diagnose your starting point

To launch new businesses you need to have the capabilities to incubate those companies on a small scale. (That is, you need to get them from New to Big before you can take them from Big to Bigger.)

You likely already have some existing assets and capabilities to support this work. Instead of throwing it all out and starting from zero, you’re better off taking stock of the people, resources, and networks your organization currently has to support innovation, and cataloging which mechanisms, people, and bits of existing infrastructure can be used for Growth OS work. For instance, you may already have prototyping capabilities, or a team of designers and developers you could commandeer to form a labs team. Or perhaps you have a forward-thinking lawyer or two who is absolutely delighted at the thought of streamlining processes for rapid in-market testing of new products and services. You also need to identify where the major capability gaps are, and create a road map to address them.

In addition to internal mapping, compile a resource list of external people and organizations who might be able to offer insights or assistance. Entrepreneurs who fall within the networks of your company’s leadership, startups in the area or who are connected to your organization, possible academic partnerships, even nearby angel investors. At the very beginning, you’ll be unsure which types of support you’ll need to enable New to Big work, so build an arsenal of knowledge, allies, and experts. Alongside the Ops Team, these folks will be essential in clearing roadblocks and providing outside-in guidance to OA teams and the Growth Board.

Nothing is secret, nothing is sacred

The teams working on New to Big projects will live in their own separate sandbox. Many of the normal rules won’t apply to them, they’ll be held to different performance standards, and the work they’ll be doing will be wildly different from everyone else’s. They’re special, different, set apart…and therefore both fascinating and threatening in equal measure to most promoters. Everyone outside the circle either wants to be inside, or at least to be told exactly what’s going on inside. If they aren’t, they may panic, complain, and resist.

As we discussed in chapter 8, it is essential that everyone understand what’s going on. Installing the Growth OS is ultimately a process that happens across levels, in multiple business units, and it affects the whole company directly or indirectly. Failing to address pressing internal questions quickly, clearly, and empathetically means they’ll multiply: more questions, more anxiety, more roadblocks, more wasted time. Additionally, treating everyone within the pilot like rock stars and everyone outside the pilot like peons causes rifts and breeds mistrust.

From what we’ve seen, the two biggest growth-killers are misaligned goals and misunderstanding. When different groups doing New to Big work have different ideas about why the work is being done at all, you end up with factions, friction, and shoddy results.

The best way to avoid that disaster is to communicate strategically; no secrets, no elitist nonsense, no BS. Creating an effective communication strategy is critical to creating buy-in, building internal alignment, and shaping the growth story of the organization, both internally and externally. And part of that strategy will be branding the work.

Why? Because it gives everyone a common language in which to discuss what’s going on, ask targeted questions, and understand the answers they receive. Once it’s branded, it’s no longer viewed as a toy. It’s a real growth program, which means people are more apt to respect it. So give it a memorable, branded name that reflects your specific company’s personality and mission. Give it the gravitas it deserves.

Document now, teach later

Assuming the pilot is successful, you’ll expand New to Big work beyond your initial teams and OAs, building it into a companywide operating system for growth that touches every business unit. Unless you want to reinvent the wheel every time a new group is brought on board, you’ll need to both document your processes and analyze the living daylights out of them.

Yes, everyone will experience the discomfort of transition; there’s no getting around that bit. Over those first nine months, they’ll try and fail and learn and regroup and pivot and tinker with new tactics. Finding and capitalizing on a new, viable business opportunity is one of the Ops Team’s objectives, but being process-focused guinea pigs is another. They’re living through this new methodology, identifying the kinks, and doing their best to work them out.

Those first teams should be able to teach the next cohort how to do New to Big work in ways that gel with your company’s existing procedures, assets, goals, and people. And if there’s no documentation of what worked, what didn’t, and what wasn’t even attempted, they’ll have a seriously frustrating time doing it.

Doing the work is sexy. Documenting and post-processing the work is not. But if you do one without the other, you’re setting yourself up for one-off success but expansion failure.

Go slow to go fast

Another benefit of documentation? It forces everyone involved to work slowly and mindfully, putting real thought into each step instead of sprinting forward and hoping for the best. The pilot phase—those first nine months—should be thoughtful and steady. Cross-country, not the fifty-yard dash. Select OAs, get a few quarters of Validation under your belt, and convene a couple of Growth Board meetings, but don’t force more work into this time frame. The pilot is like a set of training wheels; its entire purpose is to build confidence, teach mechanics, and get everyone comfortable riding. Since every participant will learn at a different pace, getting them comfortable should be a gradual, thoughtful process. Although we want to foster quick decisions and fast learning eventually, we need to go slowly at the beginning to make that speed possible in the future.

One advantage of taking this work at a measured pace is it allows you to customize, course-correct, and pivot. You may find that some of the processes and recommendations we’ve outlined in this book really grind the gears of your company, and if they do, we encourage you to build workarounds.

For instance, maybe you’ve already done some exploratory work while researching current customer problems, and want to use the Growth OS to apply new thinking to existing projects. If that’s the case, you can take a project that’s already in motion, pause it, and reframe it as an OA. Look at it through the lens of customer pain points; ask, “What does this customer need, and how are we addressing that need with this product or service?” By recasting the project as an OA, you give the team permission to explore other possible solutions.

If you try to cruise through the first steps of the pilot at light speed, you’ll miss out on key learnings and provide a painfully short adjustment period for your teams. Instead, get some early proof of the increased speed and decreased cost of learning through this approach. Allow the teams to open the aperture on new solutions they’d never have proposed before using the Growth OS methodology.

Phase 2: Expand into the business units

Once your initial teams have gotten their sea legs, demonstrated some real impact, and become comfortable enough with their new roles to start teaching others, it’s time to spread the joy of New to Big deeper into the company. This next phase is especially important if you’re focused on cultivating growth capability, since it disseminates this new knowledge base to a larger group within your organization, but also has value if you’re still focused on net new growth. After all, there’s only so much one or two OA teams can explore. If you’re aiming for more bets overall, you’ll need more teams doing the work.

Based on what’s clearly worked within the pilot phase, decide what to replicate and what to abandon. Then start discussing both how to expand and which business units show the most promise for becoming New to Big powerhouses.

EXPANSION DETAILS

Time frame: 12 to 18 months

CAPABILITY PRIORITIES: EXPERIMENTATION AND LEARNING

Codified OS framework—The Ops Team documentation from the pilot needs to be cleaned up and codified into a framework of how the Growth OS works in your organization.

Established Validation methods, systems, and training—The methods and tools the cofounders use are codified and packaged up for training and replication with the next pool of cofounders.

Expand into new business units/geographies—As new BUs/geographies set up OAs, the Ops Team will need to expand their resources and processes to support them (for example, teams running experiments in Europe will require support from legal to comply with different privacy rules).

Human Systems “labs” in motion—The “good enough” workarounds that the HR/People Team used in the pilot shift into more formalized experiments and systems for talent.

Communications program—It’s time to start sharing the work of the Growth OS more broadly within the organization.

GROWTH PRIORITIES: HEALTHY PORTFOLIOS

Growth Board: Enterprise-level + new business unit–level GBs—Now that your first GB is going strong, add Growth Boards at the BU leadership level for the business units you expand into.

Ops Team: Enterprise-level + new BU-level Ops support—Let the enterprise Ops Team teach BU-level Ops teams.

Opportunity Areas: 2 to 5 per BU—Just like in the pilot, start with a couple in new BUs and then add OAs over time.

Portfolio of solutions per OA (organic and inorganic)—Each OA should have a handful of active solutions in the seed stages, with an eye on inorganic (startup investment/partnership/acquisition) bets as well.

Ongoing recon to shape OAs—Recon isn’t a one-and-done process; cofounders need to keep an eye on startup activity, investment flows, technology timelines, and regulatory changes that might shape or redirect OAs.

Stage the rollout carefully

Assuming you’ve branded this work and been enthusiastically communicative with the entire company about progress and successes, there are likely to be a few business units eager to hop on board and implement Growth OS methodologies themselves. That eagerness is fabulous, and definitely something you want in your Phase 2 participants…but eagerness alone is not enough.

You’ll need to partner with business units that have both growth potential and proven stability. You’re looking for groups that are doing fairly well at their current work—not ones struggling to meet revenue goals—so they have the funding and breathing room to try something new. And you need to work with groups that have some of the skills, knowledge, and foresight necessary to make New to Big work successful. Forward-thinking team members, growth-minded unit leadership, and flexible infrastructure are all necessary here. Enthusiasm is a must, but so is capability for experimentation. Pick your Phase 2 business units strategically.

Then create and run the equivalent of a pilot (Phase 1) within each unit. If you’ve got seven units primed and ready to rock, don’t put them all into pilot at once; stage the rollout. Consider adding two units every six months so the expansion feels manageable, especially to the initial teams, who will be doing some heavy lifting as they teach their peers to fill new roles. If your Phase 2 teams have enough time to truly master this process, they can be enlisted to teach the next group of teams and let the Phase 1 gang off the hook. This is what building growth capability looks like: enabling more and more learning to be shared internally by more and more people. This is what will enable your Growth OS to be always on, always humming, always uncovering new business opportunities.

Diversify through inorganic growth

We haven’t talked about your venture portfolio in a few chapters, have we? Time to revisit this key concept. Phase 2 is the perfect time to explore new ways to ensure that the bets you have running in every single OA are diversified, and that includes investing in, partnering with, and acquiring related companies.

The reason we haven’t been peppering you with reminders to look outside your own walls for OA-supporting bets is that you need to start by building organic growth first. Build your Growth Board, master the Discovery and Validation processes, have a clear view of the OA playing field, and unleash a solution or two of your own before buying up the competition. If you don’t, your partnerships will likely crush startups with Big to Bigger processes, your venture investments will be late and expensive, and your acquisitions will be dilutive at best and disasters at worst. Organic first, inorganic second.

Once you have a portfolio of organic bets and a validation-based understanding of the space, you should begin to think about M&A and venture investments. Which existing startups could you invest in to increase the volume of bets in your portfolio? Which companies could you buy who are building a validated solution within your OA? How can you partner with startups to learn quickly and cheaply together? In Phase 2, inorganic bets complement your organic teams.

Phase 3: Scaling the Growth OS

Once you’ve successfully replicated the Growth OS pilot within a few business units and you’re seeing progress, you are ready to scale to the rest of the organization. What does that look like? We have some guidelines to share, but in general, this stage is different for each company because it is dependent on the ways you configured and customized the OS in the first two phases.

SCALING DETAILS

Time frame: 18 to 24 months

CAPABILITY OBJECTIVE: ENTERPRISE ROLLOUT

Deploy OS mind-sets + mechanics across enterprise—This is your opportunity to roll out the New to Big way of working to the rest of the organization, so they understand and value the work inside the Growth OS (and can apply the tools to their work when it is relevant).

Build a bench of coaches—The best cofounders from Phases 1 and 2 have the opportunity to step into a coaching role, serving as advisors to new cofounders when they enter the program.

Growth OS playbook to codify learnings—Take your codified New to Big systems and processes and create artifacts that teams can rely on as you expand.

Mature talent program (reporting, incentives, reviews, promotions)—Your HR systems for New to Big have graduated from “good enough” to repeatable, sustainable, and scalable.

GROWTH OBJECTIVE: LAUNCHING NEW BUSINESSES

Growth Board: enterprise-level + BU-level GBs across company—Each business unit has a Growth Board, and it is understood across the organization that this is the funding mechanism for new opportunities.

Ops Team: enterprise-level + BU-level OS support—Each BU has their own Ops Team to support the work within their group, and they share best practices and learnings with Ops Teams across the organization.

Robust portfolio of solutions per OA (organic and inorganic)—OA portfolios are healthy and Growth Boards see a robust pipeline of bets they can rely on for growth.

Launch of 4 to 6 businesses—Depending on the scale and speed of rollout, by this point the Growth OS should have graduated a handful of businesses through the build (beta) phase.

Creation of Build Incubator (systems, governance, talent, etc.)—By Phase 3 the “sandbox” should be formalized into an incubator with the systems, governance, and talent pipeline needed to take validated bets from the seed stages and build them as businesses.

Case Study: D10X at Citi

Scaling is highly individual and will vary depending on what your company does and how you are positioned in the market. But since it can be challenging to envision rollout without some concrete details, let’s take a look at how Citi successfully scaled the Growth OS. The company has done a truly phenomenal job of taking the process through pilot, nurturing it, and installing it as a permanent growth capability across the company.

Citi has long been committed to bringing the outside in and innovating based on customer needs. In 2010, Citi Ventures was founded by the company’s first chief innovation officer, Debby Hopkins. “Citi has two-hundred-plus years of expertise working with consumers, companies, and governments. From the very start we realized that to drive growth we needed to recast that expertise in new ways that are highly relevant to our customers. The question was how,” Hopkins says.

Hopkins was stationed in Silicon Valley, where she built a team with diverse backgrounds in innovation and venture investing from companies including Apple, eBay, HP, Target, and venture capital firms. Venture investing gave Citi a ringside seat to disruption in action, where entrepreneurs were creating new business models and products. “But the missing piece was that, despite having a lot of activities going and great talent with relevant skills, at the end of the day innovation without impact doesn’t count. And impact at an extremely large company requires methodology that can be shared across the organization. What was missing was a horizontal platform that would allow us to adopt a common way to create things and bring them to market across the enterprise.”

In 2014, Hopkins was at an event hosted by investor Ben Horowitz when she ran into Beth Comstock, who, upon hearing her challenge, declared, “You need to meet David Kidder.” A few days later, Hopkins called me just as I was waiting for a taxi at the San Francisco airport, headed into the city for a few days of meetings. “Hey, I need to meet you!” she said when I picked up the phone. Climbing into the car, I changed my route down to the peninsula and met her for dinner at the Fleet Street Café in Menlo Park. Over the course of the meal we sketched on the paper tablecloth the components of the Growth OS and dug into how Hopkins could adapt it for Citi’s needs. Hopkins recalls the “aha” moment was when she recognized that Growth Boards were a way for the business units to own their innovation portfolios while leveraging a common growth operating system.

This realization that lasting impact inside an established organization requires a shared way of working led to the founding of D10X, a program managed by Citi Ventures, based on the Growth OS and named for its focus on discovering solutions that are ten times better for clients. (Yes!) The growth model allowed Citi to embrace innovation regardless of whether it was happening externally or internally and created the structure and safety necessary to support employees as they tested their ideas.

At the very beginning, the teams responsible for building D10X had more questions than answers, which is only natural. But they dove in fearlessly and launched six Growth Boards within the first year, then began training employees to hone, test, and pitch their ideas. They knew they’d have to evolve the program significantly over time—and they still continue to refine it, even today—but within those first twelve to eighteen months, much of the work felt fluid.

In 2016, Hopkins retired and Vanessa Colella was named chief innovation officer of Citi and head of Citi Ventures. “In terms of groundwork, David and the Bionic team were extremely helpful in framing for us the challenges of building new businesses while operating at the scale we do at Citi,” explains Colella. “A fair share of that groundwork was a mind-set shift; framing the different orientation that’s required when you’re exploring a brand-new idea versus the orientation that’s required when you’re managing a business at scale. That was extraordinarily valuable to us in Citi Ventures and to our colleagues and leaders across the bank.”

She also points out that in most cases, a company the size of Citi would likely postpone launch until they’d created a meticulous long-term plan, cultivated a sense of how many resources to hire, and gauged what kind of time commitment was needed.

“We did not do that for our internal startups, and that meant we made a lot of mistakes in the early going,” she admits. “But we learned a lot and we collaborated extraordinarily closely with our colleagues in the businesses in order to shape D10X in a way that was valuable to their endeavors.”

How did the D10X teams deal with those early setbacks and failures? Brutal honesty. They earned permission to make mistakes because they were open from day one about what they were trying to accomplish. They also remained mindfully open to feedback when things weren’t working, and pivoted when change was necessary.

And how did D10X become a permanent, always-on growth machine running alongside Citi’s corporate core? Well, time, trial, and error were all part of the process. At the same time that they were running the unit, advising employees, and nurturing their ideas, the company was actively collecting as much data and insight as it could about what was working and what wasn’t, in order to propel the work forward. From the very beginning, Citi chronicled and analyzed D10X’s work with the ultimate goal of understanding how to expand and scale it.

Cultivating a bench of experienced entrepreneur coaches also drove successful scaling.

“We’ve now hired close to two dozen former entrepreneurs who serve as coaches for our teams and cofounders,” Colella says. “They help bring in real-world, gritty experience. They know what it’s like to pitch to venture capitalists, what it’s like to raise money, and how optimistic and passionate and humble you have to be to design a product.”

These coaches help the D10X teams refine, validate, and test their ideas, but also mentor them in continually cultivating outside-in behaviors. They show the Citi employees how to be over-the-top passionate about their endeavors, while simultaneously remaining extraordinarily empathetic and listening to signals from the marketplace. They know from experience that it’s hard to know how to execute this work, and have been instrumental in teaching D10X participants to balance competing parts of their brains.

Finally, bringing innovation to scale was fueled by a dedication to shaping the future of finance, and widespread support for anything that improved Citi’s customer service capabilities. The company was able to attract talent, leadership, and resources because of that shared attitude and outlook.

The company’s leaders are quick to point out that D10X is quite culture-specific, and that effective tactics for Citi might not work at another company. But in regard to scale, Colella says that releasing the notion of singular ownership has also been instrumental in allowing Citi to expand its growth capability, and this mind-set shift might also benefit other organizations. She emphasizes both a team mentality of shared ownership and a commitment to trusting team members as they experiment and execute.

“The key to innovating at a company like Citi is enabling our employee base to innovate,” she says. “It’s akin to when your kid goes off to college; you hope that you’ve done everything to prepare them, but you really just have to let them go. That’s how I think about D10X. We’re not trying to scale a central program, we’re trying to scale a way of problem-solving across the company. We engineered it that way from the beginning.”

Citi is not trying to replace an existing business system through the work of D10X. The company has embraced the entrepreneurship plus VC model as a form of management for New to Big, but never sought to supplant their Big to Bigger operating system, which has been essential to making their growth work both sustainable and scalable.

Profile of a D10X Startup

D10X has successfully launched many startups, but one that’s been particularly successful is Proxymity. It was founded by two Citi employees, Dean Little and Jonathan Smalley, who recognized that proxy voting is a cumbersome and antiquated process.

Quick overview of proxy voting: If you own stocks, at least once per year you’ll receive a giant, imposing packet of paperwork in the mail. The enclosed documents describe specific decisions the company wants to make with options for each. You, as a shareholder, are asked to vote via a paper ballot and mail it back. It is inevitably a lengthy and convoluted document that can stymie even the most informed of shareholders. Many recipients struggle to understand what to vote for, or even what they’re voting on. Sophisticated institutional investors often hire third-party vote advisors to help them understand the specific agenda items and how to vote such that the decision aligns to the investor’s values and interests. If you do vote, your ballot is then passed through several intermediaries before returning to the original organization. The process takes ages and has a high potential for introducing errors. It’s also wildly expensive.

For Citi’s institutional investor clients—who may oversee hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of ballots on behalf of their clients—this process is deeply onerous. But individual investors still need to voice their input, especially in our current climate where corporate transparency is valued and investors want a say in the environmental, social, and governance decisions of the companies they’re supporting.

The D10X team wanted to streamline the process while bringing real-time accuracy to this critical piece of corporate governance. They developed Proxymity as an online platform that connects companies more directly with shareholders. This tool allows investors to view a digital meeting agenda and vote digitally, thereby giving companies a clearer view of how shareholders are responding to company issues. The entire process is validated, and concludes with a post-meeting vote confirmation.

After identifying the confusing and inefficient nature of proxy voting as a customer pain point (Discovery), and experimenting to create a radically different solution (Validation), D10X developed and launched Proxymity in 2017. The startup is on track to support up to two hundred meetings in the UK throughout 2018.2

Proxymity is just one of nearly one hundred active startups across all of Citi’s major businesses, and D10X will continue to launch more in the years to come. But while volume of businesses is a definite hallmark of success, the company also keeps a close eye on internal participation and enthusiasm as signs of progress.

Colella says she monitors things like “How many of our internal cofounders whose first startup failed will come back and want to do it again? How many groups want to hear about what’s happening in D10X so that they might be able to participate? We’re trying to gauge real-world signals of how much pull there is from everyone at the company, from leadership through to our newest employees who are participating in some way, shape, or form in the program.”

D10X participants are encouraged to embrace productive failure, and report on learnings from what doesn’t work as much as from what does. They’re also encouraged to remember that any successes are built through a tremendous amount of bravery and tenacity across the whole company.

“It’s a way of working and a way of thinking that requires a very long view in terms of what you’re building,” Colella says.

Anyone who tells you scaling will be easy is lying to your face. As this case study illustrates, developing your Growth OS work into a permanent growth capability will take time, experimentation, effort, and the ability to bounce back from a long string of failures. But as this case study also illustrates, devising a way to scale this work in a way that suits your specific organization can create an internal New to Big machine capable of spawning multiple revenue-generating startups every single year.