The North Wind

In our enthusiasm to glorify and embrace nature, superlatives have lost their potency to describe its grandeur. We find ourselves repeating the same cliches. Those of us who write about bird migration are as guilty as anyone, but the facts of the matter are such that there is really no need for hyperbole. Twice each year, billions of birds, entire species, swarm across the globe, traveling thousands of miles as they follow the sun to populate regions that are habitable for only part of each year. The spatial scope of these migrations exceeds all other biological phenomena.

—Kenneth B. Able, Gatherings of Angels

In contrast with spring migration, the fall movement of birds in our area seems a quiet and leisurely affair. Springtime birds may sport colorful—even gaudy—breeding plumage, and their songs announce and animate each sunrise. In that season, the race is on to reach northern nesting grounds, to claim territories, to court, to mate, to nest, to fledge young, and to stage for the journey south again. Summer is almost too brief a season to achieve this program, especially for birds that nest on the arctic tundra or in the boreal forests of Canada.

Autumn individuals seem different creatures entirely: Most have exchanged their flashy mating garb for modestly hued traveling dress as they slip quietly southward. Their songs are mute, and we humans are often deaf to the subdued call notes that surround us in autumn. But massive movement is going on across the hemisphere and around the world. The entire migration covers a full six months, from the first shorebirds that appear during late June and early July to the owls, gulls, and winter finches of December. Actually, the scope of autumn migration is as great or greater than that of spring—though its patterns and timetables can be quite different. Throngs of newly fledged birds swell numbers vastly, and the season boasts its own unique moments of spectacle.

The fall vanguard is made up of shorebirds from the two main families, plovers and sandpipers. Birders distinguish these by their feeding habits. Plovers are “pickers” and have large eyes and forage by sight; they scurry along the ground, stopping to peck when they locate prey. Watch a killdeer in an empty lot to see the pattern. Sandpipers tend to be “probers,” hunting by feel in the mud or sand with their longer, sensitive bills. As they explore the burrows of small invertebrates, their heads have been described as mimicking the bobbing action of sewing machines.

Broad-winged hawks kettle above the hawk-watching tower at Holiday Beach, Ontario. The first north winds after September 10 trigger their spectacular migration. Lake Erie Metropark at the mouth of the Detroit River in Michigan tallies even larger numbers of these long-distance migrants. If a front is approaching from the west when a strong northeast wind is blowing, countless thousands of broad-wingeds may be funneled past these lookout points on the Canadian and American sides.

Most shorebirds don’t linger to breed in this region, except for American woodcock, spotted sandpipers, killdeer, and, rarely, common snipe and upland sandpipers, which are grassland birds declining in the eastern part of their range. The many species that pass north over our area have evolved instead to exploit the burst of insect life fueled by long hours of Arctic sunlight. During the short but intense northern summers, they wade and feed in the shallow lakes of meltwater cupped above permafrost.

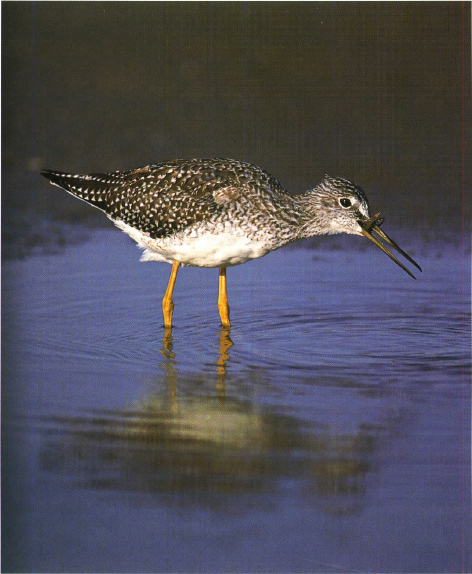

Greater yellowlegs, a species of sandpiper, sweep the water with their forcepslike bills to catch small fish. They are common spring and fall migrants around Lake Erie. This individual looks smug after a successful bout of fishing at Conneaut Harbor, Ohio. Yellowlegs’ autumn movements may actually span five months! Ornithologists have pointed out that fall migration should really be called postbreeding migration to be completely accurate, since it begins in early summer and extends through into winter. Some birds begin moving north again as early as January, so prebreeding migration is a more accurate term than spring migration, as well.

These migrators’ major flights follow the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts or span the Great Plains west of the Mississippi. Several routes leap spectacularly over the ocean from the Canadian maritime provinces and New England all the way to South America. The Great Lakes region is relatively shorebird poor. Yet the official bird list for the region includes forty-seven species, more than for either warblers or waterfowl. Moreover, notes Bill Whan in the journal The Ohio Cardinal, that state “provides the largest expanse of potential stopover habitat in the eastern US between the Atlantic coast and the breeding ranges of most of these migrants.” He continues, “Hundreds of years ago the shore of Lake Erie, and to a lesser extent the wet prairies to the south, must have teemed with migrant shorebirds every spring and fall. That this no longer happens seems almost entirely the result of human ignorance in some cases, and human insouciance in the rest” (22:37).

Market and recreational hunters routinely slaughtered shore-birds before the federal government protected all but woodcock and snipe as nongame species early in the twentieth century. The fat little Eskimo curlew was shot to the brink of extinction and may, in fact, have disappeared entirely. Some other species have not fully recovered from an age when wagonloads of birds were shot and then dumped to rot in order to clear space for still more dead birds. In addition, many of the shorebirds that do ride the wind today must ride it past the Lake Erie region rather than stopping here. This is because suitable foraging habitat has nearly disappeared: Most of the area’s wetlands have been drained.

Bonaparte’s gulls are common in fall in the Lake Erie region, and observers can view thousands of staging birds in November and December. More are seen in that season than in spring because the pace of migration is slower in autumn. The birds are en route from their summer range in northern Canada and Alaska to the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. This gull poses in postbreeding plumage and lacks the black head of the summer adult.

Ironically, these birds’ very status as nongame species has worked against them. Because shorebirds are no longer hunted, government agencies have traditionally managed what marshes remain not for them but for waterfowl, which hunters may bag legally. Hunters pursuing waterfowl—and as a group spending large amounts of money to do so—are usually not interested in preserving expanses of mud or beach. As whan wryly comments, “We haven’t worked out a way to assess the value of animals we can’t take home with us” (85). Property owners view the flats as waste ground that can easily be rendered more profitable. Natural shorelines have also been diked to protect shorefront property and roads, eliminating still more feeding habitat. Some areas do provide good shorebird habitat, such as the limestone shelving along Erie’s northeastern shore in Ontario. Rarities such as American oystercatchers and wandering tattlers occur when low water levels expose these rocky ledges.

Despite the problems, observation can reward birdwatchers who love the energy and subtlety of these wild brown birds. This is especially true in years when low water levels expose mud flats rich with invertebrate life or when westerly winds create such flats in the Erie Marshes. An arresting example of the importance of proper feeding habitat occurred in 1994 at the Turtle Creek unit of Magee Marsh Wildlife Area in Ohio. There, work on a diking project exposed a large mud flat submerged for decades, and thousands of shorebirds appeared suddenly to forage on it: 61,742 birds of thirty-two species that autumn and 34,331 of twenty-six species the following spring before the flat was reflooded. The numbers were striking indeed and included a surprising variety of rarer species. This example shows that if mud is provided, shorebirds will come.

Those who care about preserving whole natural systems rather than only showy species or those that can be hunted should encourage state and provincial managers to plan for shorebirds as well as for ducks. Unfortunately, it appears that few managers think about moving in that direction at present. In fact, Metzger Marsh, one of Lake Erie’s most significant stopping and resting areas for shorebirds in Ohio, was recently rediked to reclaim wetlands—or so it was said. As a result, invasive species such as phragmites and canary grass have invaded the marsh creating an environment undesirable for bird life. One questions the logic of this decision.

This adult little gull belongs to a Eurasian species much sought after by North American birders. It now breeds irregularly on this continent from the Great Lakes to Hudson Bay, and a few birds winter in our area. The Niagara River Gorge is a great place to see this “specialty bird” of the Lake Erie region in autumn. If it leaves this area, it will winter on the Atlantic Coast.

The buff-breasted sandpiper is a bird of dry, grassy fields and dry mud flats. It is an accidental spring migrant and uncommon in fall, a season when juveniles are consistently observed. Most adults migrate through the eastern Great Plains. This is another specialty bird of our area, and to see eight to ten in a season is cause for self-congratulation.

Diminutive northern saw-whet owls nest in the boreal and transition forests of Canada, New England, and the Appalachians. More northerly populations shift southward in autumn, though they are easily overlooked on their winter range; saw-whets are uncommon spring and fall migrants, and a few are probably residents. This owl was located at Mentor Headlands on Lake Erie east of Cleveland, Ohio. The Headlands is a small preserve—only about 100 acres—but over 300 species of birds have been recorded there.

Common terns no longer breed in this area in any numbers. Loss of beach habitat and harassment by predators such as mammals and the expanding ring-billed gull population have all but eliminated the species as an Erie nester. Experiments with artificial breeding platforms have met with some success, however.

By early July, greater and lesser yellowlegs, among the many sandpipers that nest in northern muskeg and tundra, have begun to arrive here. With them come least sandpipers and gangs of short-billed dowitchers, soon followed by semipalmated plovers, sanderlings, and a number of other sandpipers (semipalmated, upland, solitary, pectoral, and stilt). By the end of the month, birders can hope for black-bellied plovers, ruddy turnstones, and a few Wilson’s phalaropes. The first landbirds appear as well, including flycatchers (least and yellow-bellied followed by alder in early August), Swainson’s thrush, Tennessee warbler, ovenbird, and northern waterthrush. Banding evidence suggests that orioles and yellow warblers may actually begin to move south as early as the first week of July.

Why do shorebirds leave the northland so early in the year, when, by all accounts, ample food is still available there? The answer is not completely certain. In general, females leave the breeding grounds first and arrive at staging areas on the coasts and at inland sites the earliest. They have expended the most energy in producing eggs and must lay on fat before leaving the Northern Hemisphere behind. Apparently, time spent fattening on the staging grounds is key to a successful migration. Males follow, trailed last of all by the juveniles, which make up a large percentage of migrants seen in our area. These young ones’ innate sense of direction serves to guide them south without any help from their elders, and they may not even follow the same routes their parents do.

Another sought-after bird in this region is the purple sandpiper. It is a rare but regular migrant in one’s and two’s. Birders search for it on stone jetties and natural rock outcroppings around Lake Erie. Purple sandpipers’ bills are curved slightly downward; shorebirds can often be identified by the differing lengths and curvatures of their beaks, which have evolved to suit varied foraging habitats and methods.

Shorebird migration continues in flood through August, a month when American golden plovers and buff-breasted sandpipers appear, joined by succeeding waves of landbirds. Many of these are warblers, challenging to identify in their postbreeding plumage: black-and-white, magnolia, Cape May, blackburnian, chestnut-sided, bay-breasted, mourning, Wilson’s, Canada, and by the end of the month blackpoll, Nashville, black-throated blue, yellow-rumped, and black-throated green. Other neotropical migrants include scarlet tanagers and rose-breasted grosbeaks, and Baltimore and orchard orioles.

Purple martins, bank swallows, and barn swallows flock on wires in September as they begin the journey to Central and South America, with the majority of the purple martins gone by the middle of the month. This is also the time to look for migrating flocks of nighthawks in the evenings. Tree swallows will follow later, their numbers peaking in October. Hunters of aerial insects generally migrate by day—unlike most songbirds—and eat as they move. Eastern kingbirds, too, are seen in large numbers by the end of the month. Flights of Bonaparte’s gulls and common terns are reported at Point Pelee during August, though both birds have been noted in small numbers throughout the summer.

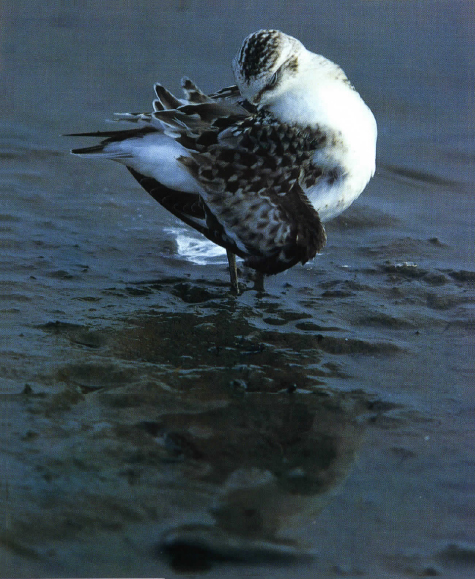

A juvenile sanderling demonstrates preening, which birds must do constantly to keep their feathers in good shape. This is essential both for flight and for waterproofing. Like many other shorebirds, most sanderlings seen in the fall are juveniles. They chase the waves on beaches to snatch up small invertebrates, and their comical gait has been compared to that of a small clockwork toy. Like many other shorebirds, sanderlings are declining in North America; changes in Arctic weather patterns may be the culprit.

Songbirds continue to arrive in September, including white-throated and Lincoln’s sparrows, palm warblers, winter wrens, ruby- and golden-crowned kinglets, blue-headed vireos, hermit thrushes, and American pipits. A strong north wind can bring a rush of hummingbirds. However, most of these birds will be gone by the end of the month except for winter residents. Insect eaters particularly must move away to the south before chilly weather eliminates their food supplies. Those that remain, such as juncos and chickadees, are either seed and fruit eaters or species that forage for hibernating insects and egg masses.

Though autumn’s pace seems less urgent than that of spring, birds still pass through in waves. Countless blue jays flow past the Holiday Beach hawk tower in October, for example, where more than 400,000 migrate through each fall. Experienced birders keep tabs on wind direction and cold fronts to predict major flights. Whereas spring migrants choose rising temperatures and south winds found on the western sides of high-pressure systems, fall travelers begin to move when the wind is from the north or northwest and the temperature is dropping after a cold front has passed. They tend to avoid rain, fog, high winds, and disturbed weather in general. To arrive safely without straying off course and without burning too much precious fuel, birds must work prudently with, rather than against, wind and weather. Of songbirds, 99 percent have left Ontario before September 1, with most gone by mid-August.

If mud flats are available for foraging, short-billed dowitchers can sometimes be seen by the hundreds. They are common late summer/early fall migrants and are usually juveniles like this one. Smaller numbers of long-billed dowitchers come through from late August to November after their shorter-billed cousins have moved south. The two were once considered a single species and still present an identification challenge for birders.

American golden-plovers are long-distance champions among the shorebirds. Many adults fly nonstop over the western Atlantic Ocean to their wintering grounds in South America. Juveniles like this bird, as well as a trickle of adults, travel south through mid-America. Golden plovers are much more common in spring than in fall, using recently plowed fields as sources of food.

Northern harriers lead the ranks of migrating raptors. They may appear as early as mid-August, well ahead of most other birds of prey. However, by the end of the month the first ospreys, broad-winged hawks, and American kestrels wing past observation points at Hawk Cliff and Holiday Beach, Ontario, on the northern shore of Lake Erie. Lake Erie Metropark, eight miles from Holiday Beach as the raptor flies across the mouth of the Detroit River in Michigan, is another prime hawk-watching location.

All three are excellent places for viewing migrating hawks and learning to identify them in flight. The reason for the large numbers is geographical and relates to some raptors’ reluctance to fly over water. Harriers, ospreys, merlins, and peregrine falcons are strong fliers with tapering wings that allow them to strike out boldly across large bodies of water. Observers at Point Pelee often see them take off from the tip of the point and fly directly across the lake. In good weather, even a few American kestrels and sharp-shinned hawks will do the same.

But soaring raptors, such as turkey vultures and hawks in the buteo group(broad-winged, red-shouldered, and red-tailed), almost never cross water. Their shorter, broader wings are ideal for exploiting columns of warm, rising air called thermals as a way of covering distance. A turkey vulture can soar without flapping because it circles within a thermal, always gliding downward but being carried upward at the same time by the more rapidly rising air bubble. Naturalist Edwin Way Teale compared thermal soaring with the lift that occurs when a person walks slowly down a rapidly rising escalator. When the bird finally reaches the top of the air column, it partially folds its wings and glides to the base of another thermal in the direction of its travel, where it repeats the process. Traveling in numbers helps vultures and hawks locate thermals by watching for other birds spiraling ahead of them

Since water is cooler than land in both spring and fall, thermals do not form over the lake, and soaring raptors must detour around it. A map will show that the peninsula of southwestern Ontario funnels these birds southwest along Erie’s north shore and around its western end, creating spectacular concentrations at certain points in the fall. (Hawks can also be seen migrating in spring, but not in such large numbers because of differences in their spring routes north.)

Raptor experts have recognized Lake Erie Metropark’s importance as a hawk observation site for only about fifteen years, yet watchers at the site consistently tally more raptors than those at either Hawk Cliff or Holiday Beach. Although there is some disagreement among birders, this is probably because hawks following Erie’s north shore and other birds flying south along Lake Huron’s western coast all converge here just south of Detroit. (Counters probably miss many birds, which thermals carry out over the lake or farther inland.) In addition, observers at the metropark are treated to birds flying much lower than at Holiday Beach because they have lost their lift over the short water crossing of the Detroit River.

Common snipe winter throughout South America and are common migrants here, though they are more often seen in spring than in fall with a few remaining to nest. Like their relative the American woodcock, they wear cryptic colors that help them to escape the notice of predators. These include humans: Snipe and woodcock are the only two shorebirds that are still classified as game birds and may be legally shot. The two species are also alike in their sensitive, probing beaks and in their remarkable fields of vision, which cover nearly 360 degrees.

This adult Lapland longspur has exchanged its brighter black, white, and chestnut breeding plumage for more subtle coloring. Summering in the circumpolar high Arctic tundra, these birds arrive here in October and flock with snow buntings and horned larks in winter fields. As with snow buntings, their thick, fluffy feathers help them withstand the season’s cold.

An adult black-bellied plover forages at Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio. It is well into molt from summer plumage to its basic winter coat of sober gray. The transition between the two plumages proceeds relatively quickly. The black-bellied is slightly larger than its close relative, the American golden-plover, whose back feathers are more gold than gray, and it is a common migrant in the Great Lakes area.

Semipalmated sandpipers are perhaps North America’s most common shorebirds, sometimes passing through our region by the thousands. The species is one of five small sandpipers called “peeps”: semipalmated, western, least, white-rumped, and Baird’s sandpipers. Difficult to distinguish from each other, all five migrate through the area. This individual is a juvenile and, along with others of its species, will leave the area by the end of September. Pointe Mouillee in Michigan is one of a handful of locations hosting numerous shorebird migrants.

Whatever the reasons, a peak day at the metropark can be extraordinary, especially at the height of the broad-winged hawk migration. Broad-wingeds, along with their western cousins, Swainson’s hawks, are famous long-distance travelers among the raptors. The broad-wingeds that soar above Lake Erie Metropark are en route to a wide flyway extending along the Mississippi River, the Texas coast, and eventually into Mexico, Central America, and northern South America. They arrive in our area between September 10 and 20, usually around the fifteenth.

The birds’ timing must be impeccable. Ornithologists believe that these hawks, which generally hunt from stationary perches, seldom feed during migration, having laid down fat to tide them over until they reach the wintering grounds. To arrive there, they must conserve this stored energy by soaring in thermals, which they often do in great flocks called kettles. Some kettles can hold thousands of birds. If the broad-wingeds wait until too late in the year, thermals will weaken, and the exertions of flapping flight may fatally deplete their reserves. As ornithologist Keith Bildstein puts it, broad-wingeds are in fact, “racing with the sun.” His account of the constraints of broad-winged migration in Kenneth Able’s Gatherings of Angels is excellent reading for those who want to understand this remarkable natural event.

In the Lake Erie region, broad-wingeds afford the most dramatic moment of the fall migration, and for lucky or foresighted birders it can be very dramatic indeed, depending on weather conditions. Before 1999, the highest number of broad-wingeds reported at Lake Erie Metropark in a single season was 399,000, hardly a number to scoff at! However, in the course of one spectacular day, September 17, 1999, birders at the park estimated an unbelievable 503,000 broad-wingeds soaring high past nearby Pointe Mouillee around the western end of the lake on the way to their South American wintering grounds. Of such fortuitous occurrences legends are made! By the end of the month, however, all the broad-wingeds except stragglers have passed on to the south.

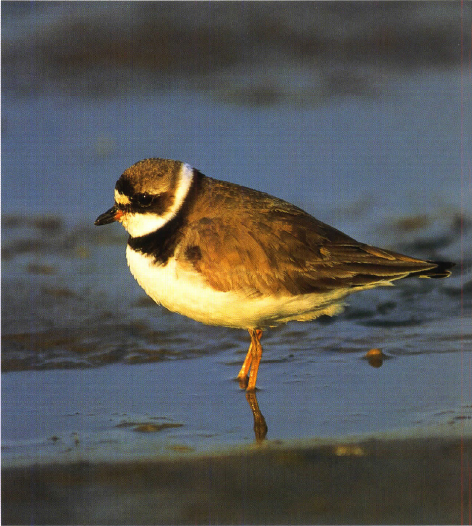

The feather wear on this semipalmated plover (not to be confused with the sandpiper of the same name) indicates that it is an adult bird. Unlike its cousin the piping plover, which is almost extirpated in the Great Lakes area because of declines in its beach nesting habitat and disturbance by people, the semipalmated is a fairly common migrant. The location of its nesting grounds in far northern Canada and Alaska has spared it the disturbances that have plagued the piping plover.

Besides broad-wingeds, harriers, and kestrels, accipiters such as sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks appear in September. Red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks soar by in the weaker thermals of that month, and merlins and a few peregrine falcons also arrive. Most species do not span such great distances as broad-wingeds, whose goal is South America, though some kestrels and Cooper’s hawks may move as far south as the Gulf States. Most stay farther north. Some peregrines, however, travel from the Canadian Maritimes to Patagonia—in a little over a week. Banded “sharpies,” as birders like to call sharp-shinned hawks, have been recovered in Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Mexico. Unlike broad-wingeds, these bird-catching little hawks hunt as they migrate, as do the slightly larger Cooper’s hawks and the falcons.

Some red-tailed hawks arrive as late as November, and many may spend the winter in Ontario or move east through Ohio to Pennsylvania and New York after rounding the lake. Like rough-legged hawks—big buteos from the far north that also enter the Lake Erie region in November—red-tails can winter here where snow is usually not so thick as to hide the runs of voles and other small mammals.

In late October and November, numbers of hawks are fewer than at the broad-wingeds’ peak in September, but the species variety is greater. Now red-shouldered hawks and turkey vultures make their big push. It’s a good time to start looking for golden eagles, as well. Birders have tallied over 240 at Lake Erie Metropark in an exceptional year. Less experienced hawk watchers can hone their identification skills as the experts count and identify the birds passing over, gathering data important for assessing the status of raptors in North America: “Harrier at 11:00 and three TV’s coming over the house with the peaked roof.” “Kettle of broad-wingeds to the left.” “Male kestrel straight up.” “’Tail just above the trees.” Depending on the winds, the birds may fly either higher or lower, providing both a thrill and a chance to distinguish finally the difference between a flying “sharpie” and a “Coop.”

Big roosts of American crows are often seen around Lake Erie in winter. These birds have adapted to suburbia, their large roosting numbers sometimes creating Jackson Pollock paintings on sidewalks and driveways. In Essex County, Ontario, roosts may grow into the tens of thousands. Humans’ garbage and road kill are much to the liking of these intelligent and omnivorous birds.

Though most insectivorous birds have passed through by October, common redpolls may appear irregularly, as do other seed-eating birds like evening grosbeaks and pine siskins (also irregularly), fox sparrows, and Lapland longspurs. Eastern bluebirds, which have shifted from eating insects to their winter diet of berries, arrive, and snow buntings make their appearance late in the month.

October and November are the months for gulls and waterfowl. Canvasbacks, both species of scaup, common goldeneyes, and buffleheads migrate eastward through the Niagara River Gorge between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Large flocks of tundra swans wing diagonally south across Erie bound for the windy Chesapeake Bay. Loons also migrate, but on a wider front, sometimes gathering in large rafts on local reservoirs. The western end of Lake Erie seems to be a pivotal point for many loons coming down from the north. By the end of November, tens of thousands of red-breasted mergansers can be seen staging along the Lake Erie shore.

Wintering gulls begin to migrate westward into Erie’s western basin. This is a good time to look for rarer species like Iceland, glaucous, and Thayer’s gulls and the occasional jaeger, a predatory relative of the gulls. Treks to the Niagara River Gorge can be quite rewarding at this time of the year. Dubbed by local birders as the continent’s gull capital, this location can offer fourteen species on a good weekend; however, one must patiently sort through the thousands of ring-billed, herring and Bonaparte’s gulls to find their rarer cousins. Other specialties of the gorge like red-throated loons, red-necked grebes, and sea ducks such as scoters and long-tailed ducks are also on birders’ wish lists now.

Owls, too, are on the move: northern saw-whets in October, long-eared owls in November, and during December short-eared owls and a few erratic snowy owls in years when lemmings are scarce in the north. The last red-tailed hawks, waves of Bonaparte’s gulls, and hordes of blackbirds pass in November. Over the years, the Point Pelee Visitors’ Center reports many rarities as well during that month: northern gannet, harlequin duck, purple sandpiper, red phalarope, black-legged kittiwake, ash-throated flycatcher, Townsend’s solitaire, western tanager, and mountain bluebird to name a few. December hosts irruptions of winter finches such as common redpolls, evening grosbeaks, and crossbills during certain years. These irruptions are discussed in the next chapter on birds in winter. Lake Erie’s greatest effect is felt on the Erie islands. The lake moderates autumn temperatures, which causes late insect hatches. These hold back autumn migrants, especially hermit thrushes, yellow-rumped warblers, and ruby and golden-crowned kinglets.

Snow buntings are open-ground feeders with thick, insulating feather jackets. They nest in summer on Arctic shores, tundra, rock cliffs, and scree slopes. If the winter is severe, flocks of thousands appear along with horned larks and Lapland longspurs. This fluffed-up bird is a female; she is wearing buffier nonbreeding plumage than her predominantly black and white summer garb.

Dunlins make up a large percentage of shorebirds seen here each year. These round-shouldered little birds are among the most common migrant shorebirds in the region and some of the last to retreat south, with a few usually lingering into December.

Most people, even those who know little about birds, are aware of the spring migration, an event that can wake up the most oblivious of us. Fall migration is a much more subtle and serendipitous affair as birds quietly and modestly progress toward their southern homes. It’s often hard to predict where one will see numbers of fall migrants: 600 loons may appear in one spot, but only one or two in another. One observer may thrill to a thousand tundra swans, while another watcher may find none. Allen Chartier of the Holiday Beach Migration Observatory has likened Lake Erie’s unique geographic and climatic effects to a pinball machine, with winds bouncing flocks of birds hither and yon as they pass through the region, flocks appearing suddenly and as suddenly gone.

A young Caspian tern begs food from its parent. Identified by a thick, blood-red bill and large size, this species is a common migrant here in both spring and fall. Birders often hear the harsh call before they spot the bird itself. Caspian terns have usually left our region by the end of October.

Yet autumn has its own rewards for birders who like to challenge themselves to identify birds in nonbreeding plumage, who travel to witness the drama of hawk migration, who are attuned to the wild calls and subtle plumage of the “wind birds,” as Peter Matthiessen called shorebirds, or who just want to hear the lonely calls of a flock of migrating tundra swans high above the clouds on a snowy day.

ADDITIONAL READING

Able, Kenneth P., ed. Gatherings of Angels: Migrating Birds and Their Ecology. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1999.

Chartier, Allen and David Stimac. The Hawks of Holiday Beach. Self-published, 1993.

Dunne, Pete, David Sibley, and Clay Sutton. Hawks in Flight. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1988. Elphick, Jonathan, ed. The Atlas of Bird Migration: Tracing the Great Journeys of the World’s Birds. New York: Random House, 1995.

Matthiessen, Peter. The Wind Birds: Shorebirds of North America. Shelburne, Vt.: Chapters, 1994.

Powers, Tom. Great Birding on the Great Lakes. Flint, Mich.: Walloon, 1999.

Snyder, Noel and Helen Snyder. Raptors: North American Birds of Prey. Stillwater, Minn.: Voyageur, 1991.

Theberge, John B., ed. Legacy: The Natural History of Ontario. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1989.

Thurston, Harry. The World of the Shorebirds. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1996.