The Beginnings

County Durham lies in the North East of England; an area dominated by its ecclesiastical knight-bishops and coal mining. Fiercely independent, it would not submit itself to the rule of Northumberland which claimed it. In 1293, it snubbed the justices of Northumberland and appealed to parliament for its separation from their rule. This stubborn and independent spirit bred men and women who were hardy and resourceful, and to whom violence and death were no strangers. The tough character of this area’s people would be needed as coal was discovered and mines were sunk throughout its territory. With the mines came danger, ill-health and poverty alongside the contrasts of strict Christianity and heavy alcoholism. It was here that many men tried to raise families in conditions that were harsh, facing constant battles for better pay and conditions from the mine owners. The practice of being bound to an owner for a year on meagre wages was a source of great anger and frustration – anger that would boil over into violence. Often the police and soldiers would be called out to keep the peace. A typical report in the local paper in 1831 shows the tensions involved. Indeed in 1832 one of the biggest strikes ever to hit the North East caused great division and concern.

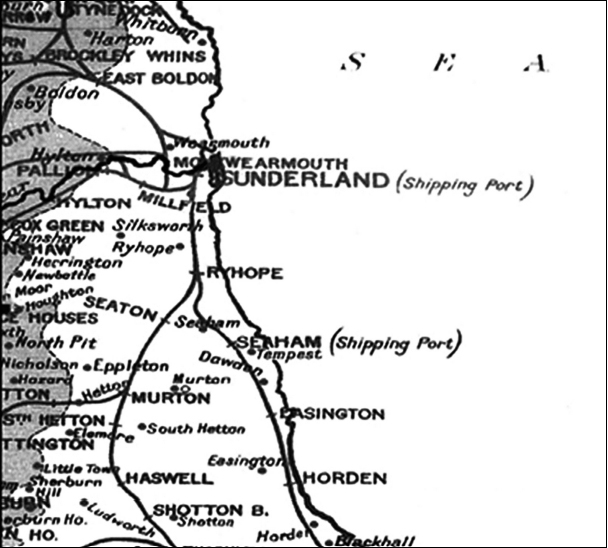

The pits around South Hetton.

THE PITMAN of THE TYNE and WEAR

We are glad to learn that all the pits ln the Lambton Colliery and also those of the Marquis of Londonderry have at length resumed working, of course with bound men. In the other collieries, however, the difference between the coal-owners and the pitmen remain unadjusted, and with but little prospect of immediate settlement, as the conduct of the latter from its fickle and unreasonable character, is found to interpose an insurmountable barrier to a satisfactory arrangement.

One claim conceded, another started, and so on without end. Meanwhile, the system of begging, intimidation, and violence, which we so often had occasion to condemn, continues to be practised in all its terrors, and with such injurious consequences, both to misguided men themselves and to the public that we feel justified in calling upon the magistracy to repress it by the exercise of the ample powers with which they are invested. The coal-owners, in order to provide habitations for workmen who are willing to serve them, are beginning to use force in ejecting the refractory pitmen from their houses: and no less vigour and determination is manifested by them for the preservation of the peace, and the restoration of order, in other respects. Six men were, on Thursday, committed to our jail, for trial at the next sessions, on a charge of rioting at Lambton, and ten others to hard labour for three months for threatening the bound workmen employed by Lord Durham, and preventing them from going to work. The prisoners were escorted to the jail by a party of dragoons. At the beginning of the week, a formidable disturbance took place at Hetton, when Mr. Wood the cashier of the colliery, was maltreated in endeavouring to protect a man whom the mob were about to strip and beat. The military, we understand had to be called in to quell the tumult; and it was only by the aid of a party of soldiers that the two ringleaders could be subsequently taken into custody. Durham Chronicle

The matter was raised in a letter to The Times:

Dated Durham, April 24, 9 p.m.:— I am anxious to inform you, that a foul and deliberate murder was committed at Hetton last Saturday night, by some of the unbound men, who basely waylaid and shot a man who was bound. I am glad to say we have got a clue to the perpetrators of the horrid deed, and have little doubt of being able to bring the charge home to the right persons. Several are implicated. Ten men were sent to gaol last night for further examination. The Governor has been at Hetton to-day, with one of them, and is to return to-morrow, under an escort of dragoons. The coroner’s inquest is still sitting, and will be adjourned over to-night. Magistrates, military, the committee, London police, &c., are daily and nightly at Hetton; of course no work is going on at the pits, but proper measures are taken for securing a sufficient number of lead miners, and I hope it will not be long ere we succeed in resuming our labours. We have turned out several families and that unpleasant though necessary work will go on progressively. Notwithstanding all the differences, Hetton itself and the neighbourhood is perfectly quiet to all appearance. The fact is, the pitmen are overawed by superior force, or, there is no doubt, they would be in a state of riot and open rebellion. They even submit to turn out, and have all their goods put into the street, without uttering a murmur; indeed many of them consider it a kind of triumph.

The article and letter demonstrates the ruthlessness under which miners had to work. Their jobs, homes and families were at the mercy of men who wanted to make their fortunes in coal. It is hard for modern minds to imagine conditions in mining at this time. Wages were low. Men had to buy certain items needed for the job out of this poor income. Health and safety was never considered to any great degree. Bad air, the risk of flooding and explosion and the fear of a collapse was the lot of a miner. This then was the background to the life of Mary Ann Cotton, who became notorious as the West Auckland Poisoner.

It was 1812, in the reign of King George III, of madness fame. The United States of America declared war on Britain, and Napoleon was invading Russia. John Bellingham assassinated the prime minister, Spencer Perceval, in the lobby of the House of Commons in London. In the North of England, at Jarrow, a mine explosion at Felling colliery killed ninety-six miners. It was into this world that Michael Robson was born in South Hetton, a village that had grown up around the mining industry. Pits were established there and at Haswell, Murton and Easington, amongst others. It had a railway built between it and Seaham Harbour in 1833. Mining was everything to the area, indeed it was the centre of life for the population. Michael Robson was born into a mining family.

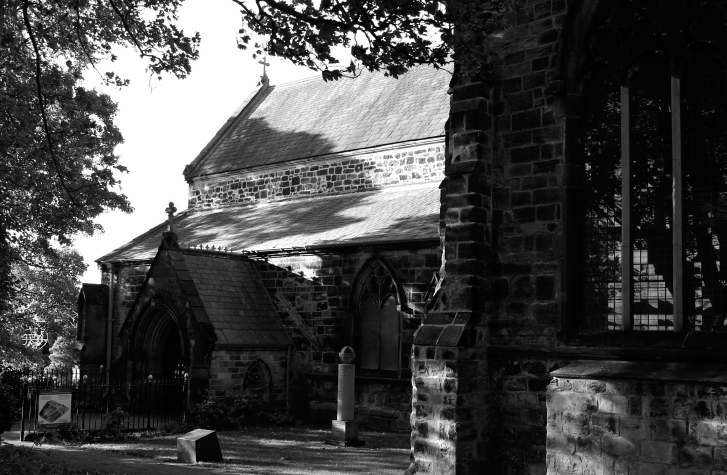

The modern St Michael and All Angels.

Michael was taken to the church of St Michael and All Angels to be baptised on 27 September 1812. The following year Margaret Lonsdale was born in the village of Tanfield, in County Durham. Margaret was taken to St Margaret’s Church on 25 July 1813 to be baptised. These two would be forever linked to notoriety as the parents of Mary Ann Cotton.

Back in Durham, in 1832, cholera was rampant throughout the area and many were dying as it swept across the South Hetton district. In the North East of England, 31,000 people died of the disease in 1832 alone. Life was miserable, work was dangerous and the hard winter brought heavy snow and ice. Deaths of both adults and children were commonplace and gastric flu could easily disguise the effects of poisoning, providing a backdrop to the many deaths that would accompany Mary Ann Cotton.

Michael Robson, only just turned twenty, sought comfort from the rigors of his life in the arms of 19-year-old Margaret Lonsdale. The two allowed passion to rule and the comfort Margaret gave led to an urgent need to get married. Margaret announced to Michael the news that she was expecting a child. He would have taken the news with stoicism. Despite their situation, both were from a solid Methodist background, and they lived their lives with the strong work ethic of their faith, accepting whatever God sent their way. Indeed they may have viewed the pregnancy as God’s way to force them into making their relationship ‘honest’. They married in July 1832.

On 31 October that year Margaret was delivered of a baby girl who, as custom demanded, was presented for baptism at St Mary’s Church, West Rainton, on 11 November 1832.

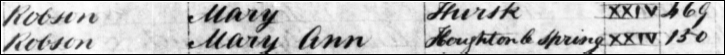

Mary Ann Robson’s birth entry.

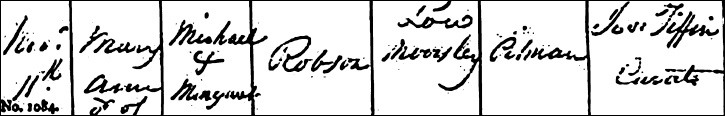

As the Reverend Tiffin, the local curate, intoned the usual blessing and then poured the water onto the baby’s head, he spoke the name that the parents had chosen for their first born, Mary Ann.

Mary Ann Robson’s baptism entry.

Thus, Mary Ann Robson was officially welcomed into the Christian community. She would grow in her Methodist faith mainly under the instruction of her mother, but her father would also insist on a strict observation of the rules and rites associated with the Methodist faith. At the time of her trial, a Wesleyan minister who knew her made this report in the Northern Echo:

Mr Holdforth, who is now a class-leader in connection with the Wesleyan body in West Hartlepool, made his acquaintance with the condemned woman upwards of thirty years ago, when, as he describes her, she was a most exemplary and regular attender at a Wesleyan Sunday-school at Murton village, of which he occasionally officiated as the superintendent. At that time, it seems, she was regarded as a girl of innocent disposition and average intelligence. Michael Robson, her father, who was a sinker at Murton Colliery, was much respected in the neighbourhood and saw that his daughter received as good an education as was obtainable at the village school. Such was her general behaviour that she soon managed to win the good opinion of all who knew her, and she was distinguished for her particularly clean and tidy appearance.

This testimony is in stark contrast to the Mary Ann Cotton of modern repute. At this time of her life we find an intelligent and well-presented young girl, well thought of in her community.

In the village of Murton, Mary Ann was introduced to the local Methodist circuit as she grew up and, in early adolescence, took on the role of Sunday school teacher to the local younger children of Methodist parents. As we have seen from Mr Holdforth above, no one in those early days would have had any idea of what lay ahead for this young, pretty black-haired lass.

Meanwhile, Michael Robson eked out a living in the coalfields where his was the dangerous job of sinking shafts in the new mines that were being discovered. The Robson family moved into East Rainton where Michael found work at the Hazard Pit. Margaret was pregnant again and on 28 July 1834 another girl was born and given the same name as her mother. The young Margaret lived only a matter of months, her death caused by one of the many illnesses that afflicted the poor. The family moved to the North Hetton colliery and then made a further move to the East Murton colliery in 1835. It was in that year his wife announced she was carrying another child. Mary Ann became a sister to the new arrival, Robert, who was born on 5 October 1835. Mary Ann welcomed her brother, Robert, into the family when she was 3 years old. From then on she would have to learn to share the meagre resources of this poor family. Perhaps the seeds of wanting betterment, money and goods were sown in the soil of this poverty and hardship. Did the young Mary Ann have to wear patched dresses and was it this that sowed in her the desire for fancy expensive dresses in later life?

1841 Census, Michael Robson and family.

The 1841 Census also shows the small Robson family, including the 5-year-old Robert, living in Durham Place at Murton.

By the time of the 1841 Census, Mary Ann was 8 years of age and her father, Michael, was still engaged in the dangerous work of sinking shafts at the Murton colliery for the South Hetton Coal Company. Mr Potter, the viewer engineer at the company, was triumphant in the success at the sinking of the pit.

South Hetton Mine Monument.

The following report appeared in the Newcastle Journal

THE SOUTH HETTON COLLIERY: The South Hetton Coal Company (Col. Bradyll and partners) have conquered all difficulty and succeeded in sinking through the sand at their extensive new winning of a colliery at Murton, near Dalton-le-Dale. This great achievement in the mining world was effected on Thursday, when great rejoicing took place among the workmen, by whose exertions and zeal, guided by the ability and energy of Mr Potter, the viewer and engineer, the great work was accomplished.

The report points to the danger of sinking shafts into difficult ground where shifting sands were a hazard. Indeed this success, as always in the coalfields in those days, was at a cost to human life. Six months after the report in the press of the success at Murton, Mary Ann’s father would pay the price for this most celebrated event. He had been among those who had rejoiced and it was the exertion and zeal of men like him that brought the company its success. However, now 26 years of age, in February 1842, Michael Robson was again working in a shaft at the Murton Colliery. It was not a deep shaft, only 300ft. No doubt the difficult sandy conditions were not helpful, but whatever the cause, Michael Robson fell to his death and was crushed as the shaft gave way. The broken and shattered body of Michael was dragged out of the mine and was wrapped in a sack bearing the stamp ‘Property Of The South Hetton Coal Company’. The body was delivered to his grieving widow, Margaret, on a small wooden coal-cart.

We can only imagine the scene as Mary Ann, with her arm around her younger brother, stood with their mother. The grief stricken Margaret is left shattered with the body of her husband. His death meant not only the loss of a beloved husband, but also of an income and a roof over her head. Michael’s hard work, with its pitiful wages, ended in the ignominy of being brought home like a sack of coal; just one of many who would end their lives this way. Such was the lot of a hard working father and miner. Michael’s Body was buried at West Rainton.

The tragedy was that in the coalfields, the loss of the miner in a tied cottage meant the widow and children would be evicted. However, Margaret, ever resourceful, had remarried within the year to George Stott, another miner. He was born at Gateshead in 1816. George was also a stout Methodist and he continued to raise the children as his own. Mary Ann, so recently losing her own father, did not take well to George.