Chapter 4

CAPE COD’S GOLDEN AGE

While Cape Cod had been a somewhat remote locale for its first two centuries, train travel made the region a much more accessible destination. Prior to the railroad, travel to the towns of Cape Cod was accomplished by packet boat, a journey from Boston to Barnstable that took seven hours. Riding by stagecoach was another method of travel, which took two full days, hardly the preferred mode of the busy traveler. The first leg of the Cape Cod Branch Railroad was established in 1848 with a line that extended from Boston to Sandwich to serve the burgeoning Boston & Sandwich Glass Company, a widely successful enterprise that produced fine hand-blown tumblers, whale oil lamps, cruets, glass hats, jugs and bottles. During its heyday, the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company employed more than five hundred workers—lured from all over the world—and produced over 100,000 pounds of glassware weekly. When Thoreau first visited the Cape in 1849, he took the train from Boston to Sandwich on the newly established line, and he found the ride a vast improvement over the stagecoach.

The railroad was extended to Yarmouth and Hyannis in 1854, and the line reached down to what is now known as Hyannisport, where passengers could board ferries bound for Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. To extend the line to Orleans, in 1861 the Cape Cod Central Railroad was formed. In 1868, the Cape Cod Central and the Cape Cod Branch Railroad were consolidated to form the Cape Cod Railroad Company. In 1870, the line reached Wellfleet, and by 1872, when the Cape Cod Railroad merged with Old Colony and Newport to become Old Colony Railroad, the tracks reached Woods Hole and Provincetown. Remarkably, the trip to the outermost point on Cape Cod was a miraculously short five-hour journey. The expanded rail line brought visitors from all over the country to Cape Cod, including President Ulysses S. Grant, who visited Provincetown during the summer of 1873. Provincetown archives record the occasion:

Train locomotive #25, the Extension, pulled into Provincetown from Boston. A second train, with a red funnel and Mount Hope painted on the sides, pulled 13 bright yellow coaches that included among its passengers three governors, one candidate for governor, Cape Cod political and business figures, and railroad officials. The great day came when flags flew, bells rang, and a great crowd came down to meet the train. At about 1PM on this date, the engine chugged around a curve and into the depot at Parallel and Center Streets, crowded almost to suffocation with townsmen who had ridden in from Wellfleet. Among the passengers was, reputedly, President Ulysses S. Grant. The first train was greeted by ringing bells and firing cannon; 800 guests dined beneath a huge tent erected near Town Hall.

By 1887, fourteen of the fifteen towns on Cape Cod were connected by the railroad. Train travel significantly reduced the cost of transportation and the time required to reach the Cape. The completion of the region’s railroad lines combined with the economic boom following the Civil War provided the middle and upper classes with the money and means to take vacations. In his travels from 1849 to 1857, Thoreau had noted that Cape Cod was “wholly unknown to the fashionable world.” Yet he predicted, “The time must come when this coast will be a place of resort for those New Englanders who really wish to visit the seaside.” By the 1870s, it was apparent that Thoreau had been right.

A SUMMER DESTINATION EMERGES

Novelist and travel writer for Harper’s Monthly Charles Nordhoff, who visited Provincetown by train in 1875, envisioned the railroad’s impact on tourism: “The railroad, as it is likely to change the old customs and break in on the simple life of the Cape, will also bring in new names and people.” He noted that the region would please the “pleasure seeker who likes to get off beaten paths, and has an eye for a quaint country and a peculiarly American people.” Bostonians discovered that Cape Cod offered an ideal respite form the city’s oppressive summer heat: the Cape was often ten degrees cooler than Boston, and the constant ocean breezes and clean, fresh air were heavenly compared to the city’s muggy and somewhat unsanitary conditions. Right along with the first trains that rolled into town, the first resorts appeared in Falmouth. Most of the Cape’s early hotels were built along Buzzards Bay and to the west of Hyannis, in Osterville, Cotuit and Oyster Harbors. By 1888, there were more than one hundred hotels on the Mid- and Upper Cape and rooms for 3,500 guests.

In affluent families, mothers brought their children to the Cape, where they would take hotel rooms for a month or even the entire summer. Fathers stayed to work in the city during the weekdays and joined the family on weekends and for a week or two each season. The family ate all their meals at the hotel, and activities were centered there, too. Guests played croquet and tennis and enjoyed evening band concerts, strolls on the beach and sailing on catboats. Lots of time was spent simply sitting on porches, gazing at the sea and breathing the healthy salt air.

Among the Cape’s elaborate resort hotels was Falmouth’s Sippewisset Hotel, located on former farmland overlooking Buzzards Bay. Built by Boston music publisher John C. Haynes, the hotel was constructed in the Colonial Revival style. Expressing American patriotism and a return to classical architectural styles, Colonial Revival design sought to revive elements of Georgian architecture. The hotel cost nearly $67,000 to build and included a golf course, a pier, a horse stable, bathhouses, tennis courts, a casino for dances and games, bowling alleys and an electric generator. After the Hallet House in Hyannisport—a mansard-roofed hotel that offered a bowling alley, billiards, a merry-go-round and a hall used for dances and theatricals—was built, the village emerged as one of the Cape’s most popular upscale enclaves. The area attracted successful businessmen not only from Boston but also from cities spread all over the country, including Pittsburgh, Chicago and St. Louis. Indiana senator Thomas Taggart and Wisconsin governor Lucien Fairfield summered in Hyannisport, and steel and coal magnate and Ohio senator Mark Hanna managed William McKinley’s presidential campaign from the village.

While Chatham first became popular with visitors in the 1860s when wealthy hunters arrived from Boston and New York to shoot waterfowl, it was the arrival of the railroad twenty years later that transformed the town into a major resort community. Several sophisticated hotels—some of which were of considerable architectural merit—were constructed in Chatham, situated at the point of the elbow, where Cape Cod bends northward to Provincetown. The most notable hotel was the elegant Chatham Bars Inn, which, unlike nearly all of the other great hotels of that era, is still in business. Designed by Boston architect Henry Bailey Alden, the Colonial Revival structure, unusual for its crescent shape, was crowned by steep pitched gambrel roofs with double rows of dormers, and the entire façade is fronted by a veranda supported by square brick piers. When it opened, the inn had amenities including electricity and running water, lacking in earlier Victorian hotels, and had twenty-four guest cottages of varying sizes on the premises.

LAVISH PRIVATE RESIDENCES

While the grand hotels of Cape Cod offered a relaxing and social experience in seaside luxury, many wealthy individuals desired their own personal havens. As the economy continued to prosper, increasing numbers of affluent individuals took to building their own well-appointed summer residences. Houses represented a variety of styles, but most were of grand scale and design. The majority of these early lavish homes were concentrated in the area along Buzzards Bay from Woods Hole all the way north to Monument Beach. There were at least a dozen summer colonies along this shore and hundreds of large, impressive summer residences.

The first noted summer residence in Falmouth was built in 1849, a bit before the resort era’s heyday, for Albert Nye, a wealthy New Orleans merchant who returned to his hometown seasonally to escape the southern heat. Inspired by Louisiana’s residential architecture and to help provide similar comforts for his southern bride, Nye had a striking house designed with hallmarks of the southern plantation style. In keeping with the plantation style, a wide veranda surrounded all four sides of the house, and it had an elevated first floor with kitchen, dining and service rooms on the ground floor, along with extremely high thirteen-foot ceilings (highly uncommon in the cold north at the time). Front to back thirty-foot central hallways connected most of the rooms inside. However, the basic style of the house was Italian Villa, bracket-style Victorian, with a square shape, hip roof, tower and roofline brackets on all three levels.

The home of Albert Nye, Falmouth’s first noted summer residence. Courtesy of Falmouth Historical Society.

A typical feature of Italian Villa style was the square tower on the third floor. A sign of the overall grandeur of the home, it was larger than most cupolas and provided views of Vineyard Sound, which are now obscured by trees. At the time it was built, the house was a wonder to the townsfolk: it possessed a furnace—the only one in Falmouth—and had a private gas plant, as the house and grounds were lighted with gas. The splendid house has been maintained with reverence to its late nineteenth-century origins and currently operates as an inn.

HIGHFIELD HALL

Another of Falmouth’s elaborate summer residences was Highfield Hall. Boston businessman James Madison Beebe, a leading dry goods retailer and manufacturer, was instrumental in ushering in the town’s summer resort era. Beebe rented several houses in town but died before he could build his own estate. Shortly after he passed away, his sons Pierson and Albert set about building on a 668-acre parcel of land their father had acquired on the town’s highest hill overlooking Buzzards Bay. In 1876, Pierson began the process of constructing an English-style country manor house, Highfield Hall. The design of the twenty-one-room house was heavily influenced by the British Pavilion buildings at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Completed in 1878, Highfield Hall was the earliest known building on Cape Cod to exhibit some of the Pavilion’s neo-Elizabethan elements: a cove cornice, a very large living hall and imitation half timbering visible on some of the home’s many gables.

Postcard of the Beebe residence, Highfield Hall. Courtesy of the Historic Highfield, Inc. Collection.

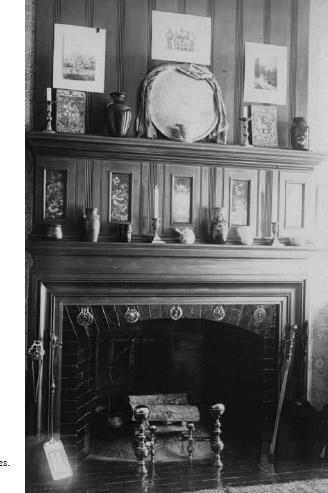

Highfield was also one of a scant few examples of the very brief late nineteenth-century period when Stick-style architecture was being assimilated into American Queen Anne. Stick-style buildings were noted for a number of unique features, all united by the use of “sticks,” flat board banding and other applied ornamentation in geometric patterns that adorned the exterior clapboard wall surface. Open trusses and braced arches spanned many projecting gables, and houses tended to have asymmetrical floor plans and a color palette of two or three contrasting colors. Queen Anne style, more ornamental and fanciful than Stick style, was characterized by complicated rooflines with steep slopes, turrets, finials and heavily decorated cornices and bargeboards with tall brick chimneys. Queen Anne–style houses also had asymmetrical plans reflective of very busy exterior compositions and could have four quite different sides. Highfield Hall demonstrated this element, as each of the home’s four elevations had a different type of projecting bay with different decorative elements. Another hallmark of Queen Anne houses were giant staircases that descended into large entrance halls, from which flowed large comfortable rooms. Highfield Hall also contained this feature. Among the mansion’s elaborate first-floor rooms was a ballroom and one of the earliest billiard rooms, which became quite popular in estate houses of the 1880s. The interior of the house featured rich detail and the highest-quality materials of the era. It had sixteen fireplaces, all with exquisitely hand-carved mantels and majolica tile surrounds, gilt sconces, rich mahogany paneling, interior eight-panel doors and several stained-glass windows to add a touch of color and whimsy to the décor.

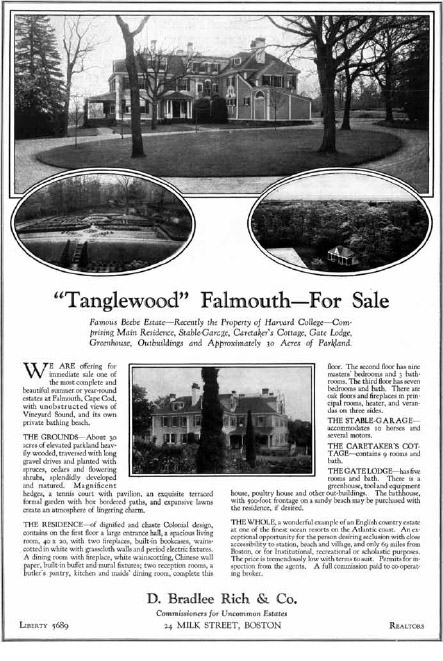

It is not known for certain whom the architects of Highfield Hall were, but there is evidence to suggest that the revered firm of Peabody &Stearns designed the house. In 1879, Pierson’s brother J. Arthur began construction of his own country “cottage” just a few hundred feet away from Highfield Hall, and he definitely contracted Peabody & Stearns to build his Tanglewood, a mix of Georgian and Colonial styles. The Beebe family compound had several auxiliary buildings, formal gardens with special plantings and some fourteen miles of maintained carriage paths and bridal trails that they welcomed the public to enjoy on Tuesdays. The Beebes, who were the largest taxpayers in town, accounting for over 25 percent of the town’s tax base, entertained on a grand scale. Boston friends and acquaintances came by train regularly, and scores of staff members were needed to attend to their needs and to maintain two such grand residences. Arthur held gargantuan banquets where he instituted an unusual dinner ritual of weighing diners both before and after their meal. At one dinner in 1896, eighteen-year-old Emily E. Beebe increased from 141 7/8 pounds to 146½ pounds.

Photo of a family gathering on the front lawn of Highfield Hall. Courtesy of the Historic Highfield, Inc. Collection.

An employee stands with a horse and carriage outside one of Highfield’s barns. Courtesy of the Historic Highfield, Inc. Collection.

One of Highfield Hall’s sixteen detailed fireplaces. Courtesy of the Historic Highfield, Inc. Collection.

A real estate advertisement offering Tanglewood for sale in 1927. Courtesy of Falmouth Historical Society.

After the last of the Beebes had passed away in 1932, the houses had a succession of owners. Sadly, Tanglewood succumbed to a wrecker’s ball and bulldozers in the 1970s. After a series of unsympathetic alterations that drastically changed the façade, Highfield Hall suffered decades of neglect and vandalism. Gratefully, community support of the historic mansion saved it from demolition in the 1990s, after which a rigorous effort was made to bring the structure back to its original glory. Today, Highfield Hall shines like the gem it was in the nineteenth century. Open to the public for tours and functions, the mansion has been restored to its rare and exceptional architectural origins.

PENZANCE POINT

In 1884, a group of wealthy Falmouth summer residents, led by the Beebes, chartered a private train nicknamed the “Dude Train.” The train transported businessmen between Falmouth and Boston during the summer. The trip took an hour and forty minutes, nearly half the time the trip lasted on a regular service train, which was almost three hours. On business days, the Dude Train arrived in Boston by 9:30 a.m. and departed the city at 3:30 p.m. The even easier access to the Cape from the city, coupled with the locale’s relaxing seascape, led increasing numbers of the Gilded Age gentry to follow in the Beebes’ wake, establishing compounds of their own nearby. A few miles away from the Beebe estate in Woods Hole, Penzance Point was one of the first wealthy enclaves on the Cape. Until the late 1880s, the land on which the luxurious neighborhood arose was owned by the Pacific Guano Company, which made fertilizer from Falmouth menhaden and guano from the Pacific Islands. After the company went bankrupt, Newton developer Horace Crowell acquired the land from its trustees. Targeting affluent families, Crowell’s plan for the waterfront U-shaped neck of land was to create a subdivision of twenty-four lots, ranging from 1.5 to 9.43 acres, served by a single road running its length. Unlike the Falmouth Heights planned community geared to the middle class that had extensive deed restrictions, Crowell had few restrictions on the sale of his lots. He required houses be built for a minimum of $5,000, and only one dwelling house could be built per lot, plus outbuildings. The beaches were to be held in common.

The houses on Penzance Point, named for a town in the Lands End area of Cornwall, England, were large and imposing, emulating English manor houses built in grandiose historical revival styles such as Tudor and Georgian. Most were surrounded with outbuildings, including stables and boathouses, and many had private tennis courts. The subdivision became known as “Bankers Row” after Seward Prosser, the head of J.P. Morgan’s Banker’s Trust in New York City, built a magnificent summer estate and persuaded some his banking associates to join him. Notable residents included the chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the managing director of Singer Sewing Machine and the Crane paper family of Dalton, Massachusetts. Nearby at Nobska Point, the British ambassador even summered for a time.

The Dude Train allowed for an hour-and-forty-minute commute between Boston and Falmouth. Courtesy of Historic New England.

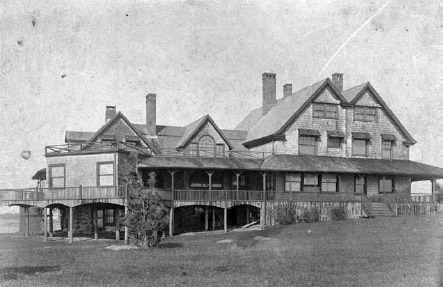

WHEELWRIGHT HOUSE

Just outside of Penzance Point, Chicago resident Mahlon Ogden Jones, president of the Southern Pacific Railroad, constructed a stunning summer retreat in 1888. The fifteen-thousand-square-foot manse was built in the Shingle style, a popular design of coastal estates built during the era characterized by lack of symmetry, rich and varied siding textures, windows of varying sizes and style and elaborate wood trim. Built upon stone bases, wood-frame Shingle-style houses were horizontal, rambling and casual—reflective of the purpose they served: to provide a relaxing seaside haven. Jones’s house was designed by Boston architect Edmund March Wheelwright, who played a significant role in steering American residential architecture away from Queen Anne style to the Shingle style. Before opening his own practice, Wheelwright worked for the highly regarded firms of Peabody & Stearns and McKim, Mead, & Bigelow.

Located two hundred yards inland from Vineyard Sound, the house had a commanding view of Martha’s Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands, and many porches framed the spectacular vista. The house featured a multi-gabled roof, with tall chimneys incorporating numerous chimney pots. Elaborate interior detailing included twenty-five different types of molding and carved plaster ceilings and fluted columns supporting decorated beams in the major living spaces. Windows were made of German-blown leaded glass, and many of the nickel- and brass-plate sink fixtures were imported from Quebec. All of the home’s millwork was done in Boston, shipped by train to Woods Hole and taken by horse cart to the site. The house also featured three hundred feet of copper guttering, which was a massive expense during that era.

Although a fire severely damaged the house in 1986, the current owners painstakingly rebuilt it according to its original nineteenth-century specs, right down to hand-blocked wallpapers and lighting fixtures. The house contains original bronze sconces on the first floor, along with rugs designed by Wheelwright. Some of the original sink fixtures survived the fire, and replicas were located for those that were destroyed. The home’s leaded-glass windows were also replicated, and the mantels of the eleven fireplaces are carved as they were in Jones’s day.

The Shingle style Wheelwright House. Courtesy of Woods Hole Historical Collection and Museum.

BREWSTER’S ELITE RESIDENCES

While prosperous communities were heavily concentrated on the Upper and Mid-Cape, wealth also spread to some areas of the Lower Cape, including the small town of Brewster, bordered on the north by Cape Cod Bay. Among the town’s fine summer estates was that of prominent native Samuel M. Nickerson. One of the most influential business leaders of the late nineteenth century, Nickerson left Brewster in 1847 to seek his fortune. By 1863, he was president of the First National Bank of Chicago, a position that would enable him to acquire massive wealth. According to a New York Times article in September 1899, Nickerson’s shares in First National Bank of Chicago were sold for $2.1 million. The syndicate that purchased the shares included J.P. Morgan, E.H. Harriman and Marshall Field.

Nickerson returned to Brewster for summer respites, and in 1890, he built a glorious shingle and fieldstone summer house. Located on a knoll along the edge of the ocean, the estate was named Fieldstone Hall and boasted a large carriage house, windmill, nine-hole golf course and a two-thousand-acre game preserve. The public was prohibited from hunting and fishing on the game preserve, which the WPA guide Cape Cod Pilot called “a slice of the Cape big enough to compare with the holdings of old feudal barons.” The Nickersons hosted many enchanting social events, and upkeep of the estate required a staff of twenty-two employees.

After Samuel and his wife passed away, their son Roland, also a wealthy Chicago businessman, and his wife, Addie, took over Fieldstone Hall. In 1906, a fire burned the home to its foundations, and the house was rebuilt in even greater splendor. Completed in 1912, the mansion incorporated some features from the original version, yet its architectural style reflected the attitudes of the 1900s rather than the Victorian 1890s. The house emulated the style of English country manors with an eclectic blend of Renaissance, Revival and Gothic themes. The house included an intricately carved, imported Italian oak staircase, Edwardian fireplaces in marble and carved wood, sterling silver wall sconces, leaded-glass windows, tiered chandeliers and a number of outdoor terraces. Upon Addie’s death, the game preserve was donated to the commonwealth and it became the first Massachusetts state park, called Nickerson State Park. Fieldstone Hall is now part of the Ocean Edge Resort and Conference Center.

Postcard of Samuel Nickerson’s lavish summer residence, Fieldstone Hall. Courtesy of the author.

TAWASENTHA

Just down the road, another fantastic Brewster mansion was built by a native Brewster resident, Albert Crosby, who also made his fortune in Chicago. After cashing in on the 1849 gold rush, Crosby went on to establish a wildly lucrative wholesale tea and liquor business in the 1850s. He later acquired the Crosby Opera House, considered the most magnificent opera house in the West. After divorcing his first wife, Crosby married one of the opera house’s young entertainers, Georgia T. Garrison, who was also known as Matilda. The two traveled extensively through Europe for a decade before returning to Brewster, where Crosby set about constructing a glorious summer home for his wife in 1887. Named Tawasentha, a word taken from his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Hiawatha,” the house featured elements of the Queen Anne style and was a combination of complex gables, dormers, clustered chimneys and broken pediments with Grecian urns on top. The house was surmounted by a sixty-foot-high tower, from which there was an inspiring view of Cape Cod Bay and a large portion of the inside shore of the Cape. Featuring the latest plumbing and heating technologies, the mansion had a steam-heating apparatus and was lit by gas. The gas supply was manufactured in the basement, along with the engine and pumps that provided the water supply.

Front exterior shot of Albert Crosby’s gracious residence, Tawasentha. Courtesy of the Brewster Historical Society.

Tawasentha was built on the plot of land where Crosby had grown up, and to pay homage to his origins, he incorporated the modest 1832 Cape Cod–style home of his boyhood into the new manse. One could walk directly from the front hall of the mansion—inspired by a room the Crosbys had visited at Buckingham Palace—through elaborately paneled doors into the old house. Matilda entertained lavishly, welcoming a glittering crowd from the artistic and theatrical circles of London, Paris, New York and Chicago, and it is said that when the parties became too much for him, Crosby retired to his old homestead. Built by John Hinckley and Sons, he hired the most skilled craftsmen on the Cape, as well as a few imported workers, to do the detail and ornamental work. So great was the undertaking that the Old Colony Railroad laid a sidetrack to the construction site.

The mansion had thirteen fireplaces, all different, with tiles imported from England. A sweeping spiral staircase crowned with intricate balusters led to the upper floors. Among the home’s airy living spaces was a billiard room finished in gold oak with a separate entrance and massive fireplace that was meant to resemble an Adirondack hunting lodge. A library was paneled in imported Indian mahogany, and walls were covered with anaglypta, a fragile material composed of hard and soft paper in layers, pressed to give a decorative relief, finished with gold leaf. An extensive south wing housed a seventy-five- by fifty-foot art gallery that accommodated a valuable art collection the Crosbys had acquired during their years in Europe. The collection included works by El Greco, Jean Francois Millet and Albert Bierstadt. Huge paintings covered the walls, smaller ones stood around the long room on easels, marble busts were perched on small tables and there were dainty chairs and sofas all around the room on which one could perch to take in the vast amount of artwork. While throughout the house there were windows of every size and shape to let in light at every turn, the art gallery had no windows except for a ring of skylights in the stepped back roof, which let in bright daylight without harming the artwork.

Back view of Tawasentha that shows Crosby’s boyhood home incorporated into the structure. Courtesy of the Brewster Historical Society.

An 1892 valuation estimated the mansion’s worth to be $25,000, quite an amount for the time period. Crosby lived in the house until his death in 1910, and Matilda resided there until 1928. Upon her death, most of the contents of the house were auctioned off for a song. Just weeks before the stock market crash of 1929, an art auction gathered a crowd of hundreds. The collection of 148 paintings, plus sculptures and bric-a-brac, was valued at over $100,000, yet the sale brought in a paltry $6,000. The house had a succession of owners. It became a music conservatory, a hotel and restaurant and a camp for overweight girls. After a prolonged period of vacancy, the property suffered greatly by vandals and vermin and became a dilapidated mess. In the 1990s, however, a rescue mission began when the Friends of Crosby Mansion was formed, dedicated to restoring the mansion. Now part of Nickerson State Park, the house is well on its way to resurrecting its graceful past. Significant restoration has been done—elaborately carved tables and rich paneling abound, original mirrors gleam and the prominent winding staircase easily recalls the grandeur of the Crosby era—and the public is welcome to tour the property seasonally.

View of Tawasentha’s curved staircase railing from the second floor. Courtesy of the Brewster Historical Society.

Intricate sconces and hand-blocked wallpapers were found throughout the mansion. Courtesy of the Brewster Historical Society.

GRAY GABLES

Among the dignitaries who were establishing estates on Cape Cod in the later half of the nineteenth century was President Grover Cleveland. In fact, his presence did much to elevate the region’s cache as a high-class summer haven. In 1889, after he finished his first term as president of the United States, Cleveland created his personal summer retreat on the far end of Buzzards Bay in Bourne. Drawn to the area for its solitude and natural setting, President Cleveland, a great sportsman who loved to fish, purchased 110 acres of rolling land surrounded by a heavy woodland of pines, oaks and cedars, with commanding knolls and one and a half miles of beachfront. Cleveland purchased the estate, which he named Gray Gables, for $20,000. There was a hunting lodge on the property that he kept intact, and he opted to rebuild the existing house on the property into a twenty-room Shingle style mansion with many gables and open porches that wrapped around the entire house.

When asked by the Boston Globe why he chose Buzzards Bay, Cleveland responded:

Exterior shot of Grover Cleveland’s Gray Gables. Courtesy of the Bourne Archives.

I come to Buzzards Bay to spend my vacation because of all the places within my knowledge it is the most comfortable and convenient. So far as my location is concerned extreme summer heat is unknown. Boating and bathing are all that could possibly be desired, and the drives about me are full of interest. The fishing which to me is a most important consideration, is excellent. All manner of sea fishing is near at hand and when one tires of that he has but to turn his back to the sea and within easy reach are numerous fresh water ponds where all sorts of fresh water fishing is to be had. I like my residence too, because my neighbors are of that independent sort who are not obtrusively curious. I have but to behave and pay my taxes to be treated like any other citizen of the United States.

In 1892, a telegraph instrument was installed at Gray Gables to record the proceedings of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. On September 24, a group of friends gathered with the Clevelands to await the outcome. It was near sunrise before the nominations were finished, and Cleveland was nominated by a landslide. That November, he was elected the twenty-fourth president of the United States. During his second term in office, Gray Gables became the summer White House. A private railroad station was established near his home with the primary purpose of transporting Cleveland to and from Washington, D.C., in an expedient manner.

The Gray Gables Train Station. Courtesy of the Bourne Archives.

The Secret Service agents who surround the comings and goings of presidents and even an ex-president today had no counterpart in Cleveland’s time, so there was no entourage dictating the course of Cleveland’s summer days. In Bourne, he was very much a man of the people. He was simple and unpretentious, entirely approachable. He refused to let photographers take photos of Gray Gables. He preferred that life at Gray Gables be simple and filled with time spent with his family, though Cleveland and his wife, Frances, did host a few glamorous events at the house and he invited his political friends for extended stays. He also enjoyed the company of his neighbors, who included the actor Joseph Jefferson, well known for his role of Rip Van Winkle. Cleveland spent summers at Gray Gables until the untimely death of his daughter Ruth (for whom the candy bar “Baby Ruth” was named) in 1904; the thought of spending time at Gray Gables without her was too devastating. The family sold the estate in 1921, and much of the land was parceled into small lots and redeveloped. The mansion became an inn and restaurant, which sadly burned to the ground in the 1970s.