Chapter 6

MODERNIST RESIDENCES

As World War II drew to a close, Modernism was taking hold in America. Important architects of the Bauhaus—the German movement that stressed simple, functional designs blended with artistry—had fled to the United States. Nazi propaganda had cast modern architecture as degenerate, brute and Semitic; in contrast, America embraced architectural Modernism as progressive and democratic. Many of these early Modernists made their way to Massachusetts, including Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, who both became professors at the Harvard School of Design. They designed houses in Boston suburbs with flat roofs, cubic shapes and open floor plans.

OUTER CAPE BECOMES A LABORATORY FOR

MODERNIST ARCHITECTS

In the early 1940s, Jack Phillips, an acolyte of Gropius, envisioned a Modernist outpost on the Outer Cape. The young Bostonian had inherited eight hundred acres of ocean-side woodland in Wellfleet, and he began building a series of small, lightweight houses. Locals referred to the houses as “paper houses”—and some people were suspicious that the foreign structures were somehow being used to signal German U-boats lingering offshore. After the war, Phillips persuaded many prominent Modernist architects—including Breuer, Serge Chermayeff, Paul Weidlinger, Nathaniel Saltonstall and Oliver Morton—to build summer cottages in the area. Architects found that the Cape was an ideal place to experiment with their designs. They were enticed by the region’s pristine environment and undeveloped land that was available for modest sums. In some cases, lots cost as little as $1,000, and the architects could build houses for as cheaply as $5,000.

On the Outer Cape, architects could build very close to nature and have an artistic way of life. The Modernist cottages were built predominantly in Wellfleet—many within the Cape Cod National Seashore—as well as in Provincetown and Truro, throughout the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Nestled by thick scrub pines, overlooking salt ponds, inlets and sand dunes, structures were oriented to capture views and breezes and to integrate with the outdoors. The tiny houses were humble in budget, materials and environmental impact. They were airy and informal, with few frills, exemplifying the concept that a lot of material things were not necessary to live happily. Designed to sit lightly on the land, “The houses were ‘green’ structures well before ‘green’ was the big thing,” says Peter McMahon, executive director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, a nonprofit devoted to documenting and preserving the Modernist architecture on the Outer Cape. “They were small, built low to the ground, and designed to sit in the landscape. They didn’t overpower the setting, or stick up into other people’s views, which is what you often see with new construction now.”

While the houses were intended to be rustic, a lot of thought went into building them. “The designs were very intentional. There’s a lifestyle implied by these buildings, one that recognizes the importance of nature, creativity, and sustainability,” says McMahon.

Architects used the remote stretch of the Outer Cape as a laboratory where they could explore the fundamental ideas about shelter. They studied the structural and weathering characteristics of wood and experimented not only with different types of wood but also with concrete and homasote, the first building material made from recycled consumer waste. Hallmarks of the Modernist cottages included flat roofs, boxlike shapes and expansive windows and doors designed to let in as much natural light and views of the setting as possible.

MARCEL BREUER

Marcel Breuer was among the most internationally acclaimed architects to build on the Outer Cape. In Germany, he was a master furniture maker, and his experiments in tubular steel revolutionized furniture design. After coming to America, his residential designs became very popular on postwar modern houses. Among his numerous large commissions was the design of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. Breuer arrived in Wellfleet in 1944, where he bought a pond-front parcel of land from Phillips. He developed a prototype for a simple vacation house that consisted of a simple, shed-roofed volume with tongue and groove cedar siding over plywood and a roofed, screened porch and sun shade suspended from cables. Breuer designed a house for himself and one for his close friend and MIT professor Gyorgy Kepes based on this prototype, along with two other similar houses in Wellfleet. He planned a community of five to seven others based on his prototype, but it was never realized. Built with off-the-shelf materials, his houses had a sculptural quality, were humble in scale and were sensitively sited to maximize the landscape. Breuer and his wife spent summers in Wellfleet for the rest of their lives. After retiring in 1976, he died after a long illness in 1981. The architect is buried behind his beloved Wellfleet home.

A Marcel Breuer–designed cottage in Wellfleet, sited to maximize views and sit lightly on the landscape. Photo by Bill Lyons.

SERGE CHERMAYEFF

A close contemporary of Breuer’s was Serge Chermayeff. Born in what is now the Chechen Republic, Chermayeff was educated in England. Following a brief stint as an interior designer, he formed an architectural firm with German architect Erich Mendelsohn. A decade later, Chermayeff was working as an architect in the United States. He became chairman of Brooklyn College’s architectural department and was later the president of the Institute of Design in Chicago. Until his retirement in 1970, he held positions at Harvard, Yale and MIT. Like Breuer, Chermayeff arrived in Wellfleet in 1944, where he purchased a small cabin on twelve acres of land for $2,000 from Phillips. Over several years, he transformed the site into a family compound with a studio where he could pursue his great passion: painting. The frame of the main house was made of diagonal braced two- by ten-foot boards, with light panels in-filled with brightly colored homasote crossed with strapping. An open porch overlooked vast woodland. Over time, the porch was enclosed, the homasote was replaced with clapboard and the colors became more muted. Interested in exploring the expressive possibilities of the post-and-beam frame, he designed at least ten more houses and commercial structures on the Outer Cape. He spent time at his beloved home in Wellfleet until his death in 1996.

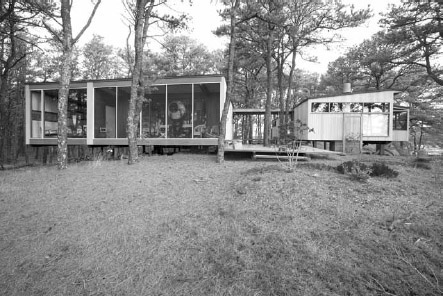

JACK HALL

A close friend of Jack Philips, Jack Hall was a Princeton graduate who moved to Wellfleet in 1937. For $3,500, he bought an old farm compound spread out on 180 acres from writer John Dos Passos’s wife, Katie. A self-taught designer and builder, he had his own design practices in both Wellfleet and New York City, where he also instructed at Parsons School of Design’s Industrial Design Department. Hatch’s most intriguing project was the Wellfleet cottage he designed for the editor of the Nation magazine, Robert Hatch, and his wife, Ruth. Located on a fabulous perch in the dunes overlooking Cape Cod Bay, the minimalist summer cottage was conceived as cubes in a grid matrix. The house, built in 1960, had three separate units in a three-dimensional grid: the living room/kitchen, two bunkrooms and the master bedroom and studio. Hall’s plan allowed for the exterior walls to be winched up to expose glass and screen panels that opened up to covered verandas that wrapped around the house. Surrounded by vegetation, the structure hovered just a few feet above the landscape—so much a part of its setting that it was barely discernable where the boundaries were between the indoors and out.

PAUL WEIDLINGER

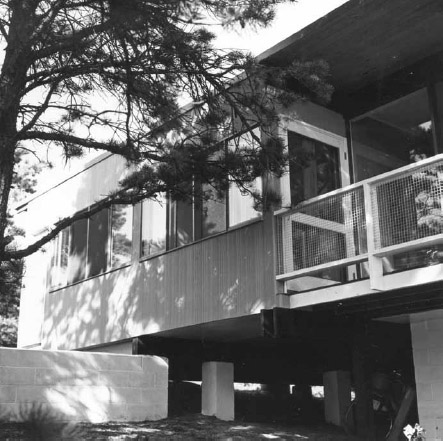

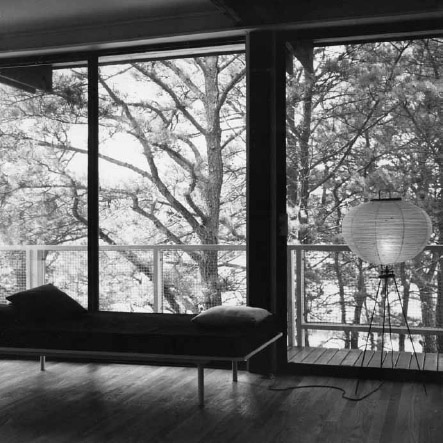

Not far from Breuer’s house in Wellfleet, Paul Weidlinger built his own summer haven in 1953. Weidlinger, who apprenticed with Le Corbusier, one of the pioneers of Modern architecture, was an innovative structural engineer. He collaborated with architects all over the world on major commissions and worked with artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet and Isamu Noguchi to create large outdoor sculptures. An adjunct professor at MIT and Harvard University, he did pioneering work in earthquake and blast-resistant buildings. Weidlinger’s close friend, Breuer, along with Gropius and Le Corbusier, all gave him advice on the design of his summer house. Le Corbusier reportedly gave the advice “don’t pave the driveway.” Le Corbusier believed that forcing drivers to proceed slowly would allow them to take in the precious transition of the landscape, so Weidlinger left his driveway a narrow, bumpy dirt path that winded from the main road through the woods to his lot. Weidlinger’s home in the Wellfleet woods sat on stilts, barely making an impact on the land. Inside, the house centered on one large, open room with walls of glass that opened onto a wraparound balcony with an overhanging roof that spoke to the desire for indoor-outdoor living and kept the house cool in summertime.

Exterior shot of architect Paul Weidlinger’s summer home that sat on stilts in Wellfleet. Photo by Madeliene Weidlinger-Friedli.

The large, open living space that Weidlinger’s cottage centered upon. Photo by Madeliene Weidlinger-Friedli.

NATHANIEL SALTONSTALL AND OLIVER MORTON

Among the commissions Boston-based architects Nathaniel Saltonstall and Oliver Morton designed was the first Institute of Contemporary Art building (Saltonstall was a founder and president of the museum from 1936 to 1948). The partners began designing projects on the Outer Cape in the 1940s. The most notable of their works was the Colony (originally called the May Hill Colony Club), a complex of multiple Bauhaus-inspired units that housed artists who were invited to exhibit their work and the patrons who were invited to buy it. The flat-roofed cottages, set among the sandy, pine-studded hillside of Chequessett Neck, were arranged in a meandering circle clustered around a communal gallery. It was an enclave for the elite; guests had to have social and banking references to stay there. Over the years, guests included writers Bernard Malamud and William Shirer; actors Paul Newman and Faye Dunaway; publisher Alfred Knopf Jr.; and numerous other intellectuals, professors and artists. While visitors may have been elite, the accommodations were far from it. Cottages were small and sparse, mostly one-bedroom, one-bath units with galley kitchens and rooms laid out along a straight line. Furnishings were Spartan but clean-lined and designed by leading Modernists of the day, floors were made of concrete and terraces and expansive windows embraced the landscape. Saltonstall was a prodigious art collector; original artwork hung in the cottages, while frescoes and sculptures decorated the outdoors.

The Colony still exists, though its doors are now open to all interested comers. Measures have been taken to ensure that cottages remain in their original exterior condition, and the interiors are still very much Bauhaus spaces, featuring minimalist décors with modern pieces, including Eames tables and chairs, wall-mounted desks and narrow beds that serve as couches during the day.

OLAV HAMMARSTROM

Another esteemed European architect who found the Cape to be fertile ground for experimentation was Olav Hammarstrom. After arriving in Boston during the late 1940s from Finland, he went on to work with Eero Saarinen, Gropius’s firm, the Architects’ Collaborative, and also had a private practice. He married Marianne Strengell, one of the twentieth century’s most influential textile designers, who executed many commissions for Hammarstrom, Breuer and Saarinen, including all of the textiles for the General Motors Technical Center. In 1952, Hammarstrom designed a cottage for himself and Strengell in Wellfleet. The house was built in two sections; one was insulated and enclosed, containing the bedrooms and kitchen. The other was a warm weather section, containing summer dining and living areas that could be opened entirely to the elements by means of two large barn doors on tracks. Based on his own cottage, Hammarstrom received several other residential commissions in the area, including one for MIT physics professor Laszlo Tisza.

CHARLES ZEHNDER

Perhaps the most prolific modern architect on the Cape was Charles Zehnder, who built more than forty-five homes from the 1950s through the 1970s. A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design who became a year-round Wellfleet resident, Zehnder’s early designs were inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses. His later works were inspired by a range of aesthetics, including Thomas Jefferson’s Paladianism, Mies van der Rohe’s unified and simple geometric forms and World War II bunkers. By the late 1970s, Zehnder was experimenting with poured concrete, completing four crystalline residences that also featured cantilevered wood deck structures. A noted Zehnder design is the Kugel-Gips House, located on a hill in a sparse forest overlooking a serene pond. The design exhibited long horizontal lines and a narrow base and combined wood with concrete and glass; exterior materials, such as clapboards, were also used indoors. The flat-roof house had two elevations that were bunkerlike in their use of concrete blocks and oblique windows. Facing south and west, however, ribbons of glass ran the length of each wall, and corners featured butt-glazed windows. Long, cantilevered decks and roof overhangs projected the living space into the landscape.

The Charles Zehnder–designed Kugel-Gips house, open to the public. Courtesy of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust.

PRESENT-DAY STATUS

Over the decades, many of the Outer Cape’s mid-century Modernist dwellings have suffered neglect. Others have been razed, casualties of skyrocketing real estate prices that have made land far more valuable than the houses. Still, remarkably, more than eighty Modernist cottages remain throughout the Outer Cape.

While the majority of these structures are privately owned, five located within the Cape Cod National Seashore are owned by the National Park Service. In dire need of attention, the cottages were slated for demolition not too long ago. However, thanks to architect Peter McMahon, executive director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, it seems the cottages are on the verge of being saved.

The reason the cottages within the National Seashore were threatened goes back to September 1959, when a bill calling for the creation of the Cape Cod National Seashore was introduced in Congress and signed into law two years later. In those two years, rumors circulated about the terms of legislation, particularly whether new construction would be allowed on undeveloped land and whether there would be a cutoff date for such construction. From 1959 to 1961, 120 houses were built within the National Seashore. Congress eventually made the date of the bill’s introduction the cutoff date for construction, and all of those houses were deemed illegal. The National Park Service acquired the houses by eminent domain, and most owners sold to the government or negotiated a sale that guaranteed them life use of the property or twenty-five-year leases, which have all now expired.

The five mid-century Modernist cottages were among several structures built in the park during those pivotal years slated for demolition in the late 1990s. At the time, the National Park Service met with the Massachusetts Historical Commission, and no one considered the Modernist cottages to be of architectural importance. So the National Park Service planned to tear them down. As they were not a top priority, demolition wasn’t immediate, yet the cottages sat vacant, which led to deterioration. Wood rotted, mold became rampant, rain and animals found their way in.

A crusade for the preservation of the Outer Cape’s Modernist architecture began about 2002 and gained steam in 2006, when McMahon co-curated an exhibit on the subject at PAAM (Provincetown Art Association and Museum). About this time, the National Park Service met again with the Massachusetts Historical Commission about tearing down the cottages, and they were informed that five Modernist cottages were now deemed eligible for the National Register. Although they are less than fifty years old, they are considered significant on both local and state levels because they are unaltered specimens of the Modernist architectural phenomenon that transformed postwar America.

Unfortunately, the National Park Service, which owns seventy historic properties within the National Seashore, does not have the budget to care for the houses. That’s where McMahon comes in. Since 2006, on behalf of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, he has been working with the National Park Service to develop a lease for the long-term preservation and use of the Zehnder-designed Kugel-Gips House; in 2009, he obtained the lease. McMahon received a $100,000 grant from the Town of Wellfleet toward the restoration of the Kugel-Gips House and garnered about $40,000 in volunteer pledges to do work on the ailing structure. Restoration of the cottage began in earnest during the summer of 2009. The work centered on restoring the home to its original condition, not “modernizing” it according to present-day standards. Mold issues were dealt with, rotting wood was replaced and the roof was redone. There were few updates in the bathrooms and kitchen, which have had the same fixtures since the house was built. “These houses were built for simplicity, and that’s what makes them so beautiful,” says McMahon. The décor consists of mid-century Modernist furnishings, including pieces by Bertoia, Saarinen and Bellini. The home’s purpose is to serve as an educational facility to educate the public about Modernism. It is a cultural resource open for tours, academic retreats and a scholar-in-residence program. To help defray costs, the three-bedroom, two-bath house is available for rent to individuals and corporations several weeks a year.

The Cape Cod Modern House Trust is currently in the process of obtaining a lease to restore the Hatch cottage, which has been in a rapid state of decline since Ruth Hatch, who inhabited the home seasonally until her death in 2007, passed away. As with the Kugel-Gips House, the Town of Wellfleet has pledged $100,000 toward the restoration of the cottage. The Cape Cod Modern House Trust does not have the means to restore all of the endangered Modernist cottages, which include the Weidlinger House; the Kuhn House, designed by Saltonstall and Morton; and a Hammarstrom design, the Tisza House. But it is the organization’s hope that its efforts will be recognized by others who will treat the cottages as the historic specimens they are.

MODERNISM IN FALMOUTH

Aside from the extensive group of Modernist cottages built on the Outer Cape, there were few built throughout the rest of Cape Cod. Yet the town of Falmouth was the setting for a smattering of early Modernist homes. The architect responsible for the homes was MIT-educated E. Gunnar Peterson, who had lived in Falmouth since childhood. His designs began dotting the landscape in the late 1930s. Of slightly more sturdy construction than the cottages on the Outer Cape—most of which were only equipped for summer living—Peterson’s houses were insulated and had radiant heat, with basic wood exteriors and flat roofs. Floor plans consisted of two or three bedrooms, and houses featured glass-enclosed rooms, cantilevered decks and merged dining and living rooms with smaller kitchens and the cost-cutting elimination of cellars and attics. Peterson’s one-level houses, most of which included garages or carports, cost between $7,000 and $12,000. Structures were intended to give the illusion of spaciousness, of much more with much less, and this was achieved by creating large glass areas to bring the outdoors inside, making the view part of the actual living space. Peterson’s vision was that not only should the house be part of its site and terrain, but that the inside, the area of family use, should count for more than exterior impressiveness fashioned for the eyes of neighbors.

In 1940, Peterson, who designed more than twenty-five residences in the area throughout his career, was responsible for the Cape’s first planned Modernist development, along the beach on Bywater Court in Falmouth. His creations defied the town’s architectural traditions so hard and often that he kept a scrapbook to find out which particular controversy was raging at the time. The cottages on Bywater Court, which were featured in the magazine Progressive Architecture in 1941, provided a sharp visual contrast to what was familiar to Falmouth. The town had strong negative reactions to the development, and several business owners went to town meeting to express their fears that the houses would cause a diminution of the town’s local color and would result in a decrease in tourist income. Local newspapers applied the most horrendous epithet one Cape Codder could apply to another at the time: they termed Peterson almost a native.

Unfortunately, Peterson’s Modernist designs never quite received the recognition that they deserved. While some of his creations continue to exist in Falmouth, of the ten houses on Bywater Court—which should have been lauded for their architectural ingenuity, as other planned Modern neighborhoods in the state have been, such as Lexington’s Six Moon Hill—only a few exist in their original incarnation. Some have been torn down, and others have been renovated into two-story, shingle-sided homes that bear little resemblance to Peterson’s inspired designs.