CHAPTER EIGHT

The New Continental

Creating a Way Forward

1983–1984

WE WERE fully prepared to keep our planes flying on August 13, 1983, when Continental’s machinists walked off the job. Just 150 of our 900 mechanics reported for work that day, crossing the picket line, but we quickly brought in 250 replacement mechanics who had been lined up for us by an outside contractor. Our flight attendants, mindful that we had begun training more than 600 replacement flight attendants in midsummer, withdrew from their pledge to support the machinists and turned out in full force. By the end of the first week of the machinists’ walkout, our daily schedule was at 93 percent of its prestrike level.

At that point, the machinists’ strike was effectively broken, but not without the airline getting quite hurt. Despite our ability to keep flying, the publicity surrounding the IAM strike had scared off Continental passengers. Load factors were down to less than 40 percent, and we were burning money like jet fuel—and August was usually our best month. The only thing our numbers folks didn’t agree on was when we would actually run out of cash.

Throughout this period, I actively discouraged our people from ever speaking the words “bankruptcy” or “Chapter 11.” I was deathly afraid that if people outside the company suspected that we were even thinking in those terms, passengers would take their business elsewhere. We would experience what would be essentially a “run on the bank.” Now that I’ve had the opportunity to reflect on it, such caution may have hurt us, in a sense, because it never fully allowed management to express our financial circumstances with complete candor.

The year before, Braniff had filed for Chapter 11. The CEO at the time, Howard Putnam, left the same position at Southwest to take on the enormous task of trying to save Braniff from collapse. Putnam had joined Southwest from a mid-level officer’s position at United. Neither position prepared him for the financial mess Harding Lawrence’s growth craze had created or for the turmoil brought on by deregulation. Braniff became the first airline to seek bankruptcy following deregulation. Putnam and his executive team did not believe passengers would fly a bankrupt airline, so his strategy was to ground the airline and attempt to reorganize it before restarting operations. Eventually, Jay Pritzker bought Braniff, and operations restarted in 1984 with an entirely different business model. But as we internally debated our options, Braniff was still on the ground with no assurances it would ever reorganize.

Sure, our negotiators were out there using all kinds of “drastic measures” language in labor discussions, but I suspect their talk of “pushing the company to the brink” or whatever words they used may have sounded somewhat hollow to the unions. Perhaps the imminent threat of bankruptcy might have jarred them into a compromise. Of course, it might have also found its way into the newspapers and made the prospect a self-fulfilling prophecy. In 1983, the traveling public was not nearly as used to talk of bankruptcy as it would later become. We were keenly aware that consumers had not been exposed to the idea of flying on a bankrupt major carrier up to that point.

Bankruptcy certainly wasn’t a strategy concocted to escape our labor contracts or pare back our operations, as the unions contended from the outset. To me, bankruptcy was failure, pure and simple. It was something to be avoided at all costs. We looked on bankruptcy only as a last-ditch alternative, a “making-the-best-of-what-you-have” type of move. No airline had ever survived it up to that point, and I did not have to look far for a compelling argument against it, with Braniff just up the road in Dallas.

To me, bankruptcy was the kiss of death, and no bankruptcy expert could convince me that filing would signal anything less than complete failure. Still, we retained the services of specialists at the law firm of Weil, Gotshal & Manges, led by the bankruptcy impresario Harvey Miller, and took our first tentative steps to prepare for the worst. We soon learned that there was a great deal about bankruptcy that even our expert advisers couldn’t tell us. For example, we were advised that we could “probably” alter the terms of our labor contracts under Chapter 11 immediately on filing, but we later learned that there was a case pending before the US Supreme Court that might prevent us from doing so.

My greatest concern, though, were bankruptcy issues that were specific to the airline industry. Even if Chapter 11 is technically a reorganization of debts owed to creditors, I knew that the news of our bankruptcy would not be reported as “Continental reorganizes.” The headlines would say CONTINENTAL GROUNDED or CONTINENTAL GOES BUST. I thought there was a good chance that an airline might not survive such a public relations blow.

The other problem was that once travel agents and various institutional accounts became wary of our ability to stay in business, we might face potentially ruinous cash-flow problems that not even Chapter 11 could protect us from. Already we saw some evidence that travel agents, because of their fear of our potential demise, were “plating away” our bookings to other carriers. Travel agents were required by federal regulations to pay for tickets within seven days of booking, even if the scheduled flight was three or four weeks—or more— away. As agents grew concerned that Continental might suddenly stop flying and not honor tickets, they tended to reduce their clients’ exposure by still booking Continental flights but writing the tickets on another airline’s account. This way, their clients wouldn’t lose money if Continental were to suddenly cancel flights. For us, though, this plating away meant a sharp drop-off in cash flow, dramatically reducing our working capital. Instead of getting cash within seven days of booking, we had to wait thirty days or more as some of our payments flowed slowly through the airline payments system, in many cases after we had actually flown those paying passengers.

At this point, in mid-August, I was second-guessing the Continental takeover. I blamed myself for setting in motion the sequence of events that had landed us in such dire financial straits. A number of things had not broken our way. Continental had turned out to be in far worse shape than any of us had thought; the unions were far more intransigent than any of us had feared; and the merger of our separate operations had not gone as smoothly as any of us had anticipated. All these disappointments provided me with plenty of reasons to stay awake.

On August 31, we ended another month of crippling losses at Continental by requesting more than $150 million in wage and work-rule concessions from pilots, flight attendants, machinists, and nonunion employees. In return, we proposed that employees receive ownership of approximately one-third of the company. These calls for concessions were just as difficult to make as they must have been to hear. There is no easy way to ask an employee to cut off one of the rooms in his house or to stop feeding one of his children. Surely that was how our people must have heard our appeals. Employees had their own fixed costs, and it was a very tough thing to ask them to go backward, so I took pains to present our situation in human, personal terms.

After outlining our plan to union leaders, we presented it to our pilots’ union negotiators with a proposal that would allow all employees, including the pilots, to acquire a 30 percent interest in the ownership of the airline, a request that the pilots’ union had at various times asked for. But this deal, to the best of my knowledge, was never presented to the pilots themselves.

We then set about visiting concerned employees in meetings throughout our system. During one such session in Denver, a flight attendant, a former union leader, stood up and dispassionately endorsed our plan. She said that what we were asking for was terrible but added that she saw no way around it.

“We don’t have any power,” she told her assembled colleagues. “Employees only have power when the company they’re working for is making money. Continental is clearly not making money and may well not be around without some relief. We have no choice.”

The response of this flight attendant was typical. She was not a particular friend to management, and she didn’t throw hugs and kisses at us for proposing to slice her paycheck and increase her work hours. She even said that she “barfed” when she first saw our plan. The truth is, we all nearly barfed when we saw the concessions required in the plan. It was a heck of a way to build employee morale, although the stock ownership plan was of some help. For a long time, I had held that in the service business, management could not afford not to have a healthy esprit de corps, but that had become a luxury beyond our diminishing means.

As the days wore on in September, it was clear that we were careening headlong into bankruptcy. In evaluating what we would need and how we should operate in order to successfully get through this period, I came to the conclusion that there would have to be one distinct hand at the tiller. I had been chairman and chief executive of the company throughout this period, while Steve Wolf served as our very capable president and chief operating officer, responsible for the day-to-day activities of the company. He would be the one charged with the difficult hiring and firing decisions we were soon to face—and with figuring out which routes to continue flying, what fares to charge, how much cash risk to take, and so on. But I began to realize that with my long experience in these areas, I was the logical person for the job, although it was not one that I was enthusiastic about at all.

This was no slight to Steve. After all, flying the airline through bankruptcy was not exactly the job he was hired to do. Rather, my decision was based on my belief that I needed to maintain full control of our operations during the very trying times that lay ahead. If this was to be our last and only chance, I wanted to call the shots. I never did believe that having two hands on the steering wheel was a good thing.

I also discussed the management situation extensively with our board and found the directors to be in unanimous agreement. On Tuesday, September 20, just four days before we planned to file, I sat down with Steve and informed him of our decision. I told him that it was the most troubling management move I ever had to make, and it remains so today. I explained that the directors and I felt we had no choice but to ask him to step down and let me run things, given where the company stood. Steve took it like a pro. He understood my concerns. He was very service-driven, famous for sweating out even the smallest details. He was also a tireless, dedicated worker. My admiration for him has continued, and I have followed his career in the years since. But we desperately needed an entrepreneurial approach coming right from the top.

I left it to Steve to decide if he wanted to step down before we filed or just after and to put his own spin on the move. As it played out, the press interpreted his “resignation” as the last straw in a clash over our dealings with labor and our pending bankruptcy. They surmised that Steve was prolabor and I was not, but that was not at all the case. That was classic union propaganda once again.

Rather, Steve and I parted on extremely amicable terms. There was not a moment of friction between us. We both were in full agreement on our concession proposal and the steps we had taken with the unions. I remember stepping into Steve’s office as he was cleaning out his desk, and from our pained small talk it was clear that neither one of us wanted to end our association, even if we both knew it was the right move. When he reviewed the draft of the press release about his departure, one of his comments to me was that it made him “sick to see.”

We tentatively scheduled our filing for Saturday, September 24, late in the afternoon. We chose a Saturday for obvious reasons: it was the quietest day of the week, with our lowest frequency of flights—meaning that it would necessitate the fewest passenger disruptions— and it fed into the quietest news day of the week, which meant that most of the gloom-and-doom headlines would have to wait an extra day, until Monday. Hoping for a near miracle, we also scheduled a meeting with the pilots’ union for that Saturday in a last-ditch attempt to avoid bankruptcy. They didn’t show up.

But choosing when to file was not the only decision we were facing. We had to determine what to do after our filing, and as we counted down to that date, we were still looking at a number of options. Most of our people were pushing for a complete shutdown of operations, giving management ample opportunity to cut back, implement new labor arrangements, and make the necessary layoffs, then resume flying in a week or ten days. Another option was to pare back our operations and staff immediately after filing and continue flying at around 50 percent of capacity.

There were advantages and disadvantages to each operational plan we considered. Shutting down for a week or so would give us more time to catch our breath and assess which of our key labor groups would support us in bankruptcy, but it also might send the wrong signal to the financial community and the flying public. The longer our planes remained grounded, I feared, the harder it would be to get them back up in the air. The notion of trimming back our system-wide operations and continuing to fly Continental’s most profitable routes with virtually no interruption was appealing on its face, but it, too, presented a problem. We would never know how much of our schedule we could maintain until we learned how many pilots would be available to fly our planes and how many mechanics there would be to service them.

The path we chose, a blend of those options, was to furlough our entire workforce on the Saturday evening of our bankruptcy filing, then rehire a fraction of them on Sunday and Monday at competitive levels. We would ground all our domestic planes for two days late on Saturday afternoon, then reopen for business on Tuesday morning with a dramatically reduced schedule of flights. This way, at least, we would have the balance of the slow weekend, and all of Monday, to face the monumental task of reducing the workforce and trimming domestic flights to a manageable level.

Our international operations, largely in the Pacific, had to be handled differently. We were forced to maintain all our scheduled international flights, which accounted for 20 percent of operations, because there are no Chapter 11 protections from creditors abroad, and we could not endanger our valuable international route rights by not flying them. We would plan to cut our domestic flying drastically—by 75 percent—which meant that our revenues would fall by a corresponding amount, assuming the old fare levels.

Chapter 11 bankruptcy draws a curtain through your entire financial house. All your liabilities are kept on one side of the curtain, and all your assets are left to stand on the other. Whatever revenues you generate are either paid out to meet your operating and payroll costs or effectively held in trust for your creditors. A bankruptcy judge is assigned to earmark all receivables and determine how much cash goes toward each. In a sense, bankruptcy of this kind ties one hand behind your back (preventing you from selling off assets, for example) while leaving the other hand fairly free to conduct business as usual.

Bankruptcy offered us breathing room by suspending interest payments on more than $650 million in long-term debt. Also, and significantly, bankruptcy released CAL from its labor contracts (and from most of its other contracts), leaving us free to negotiate updated terms with new and returning workers. At the time, although it was being challenged in a case before the Supreme Court, bankruptcy laws did not distinguish among labor, bank, and vendor contracts. Given that more than 35 percent of our costs were going to labor, the ability to establish acceptable work rules and wages offered us tremendous relief in the short term and would soon give us a fresh outlook on our longterm plans.

I didn’t sleep at all the night before our filing day. I had no experience managing an airline through such a critical period. No one did. As I lay awake, I tried to envision how we might navigate Continental out of the rough patches ahead. I tried to balance how aggressively we should work to achieve labor peace against what might be seen as the more pressing obligation of meeting our reduced payroll costs and maintaining some semblance of a flight schedule.

When I arrived at work early Saturday morning, I was met with the unsurprising news that the pilots had canceled our scheduled last-ditch meeting. Consequently, we dispatched our lawyers that afternoon to the US Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas, in Houston, where they formally filed for protection from creditors under Chapter 11 of the bankruptcy code. It was not necessary for me to appear personally in court, but I did have to put on a public face later that afternoon at a press conference near our Allen Center offices. I choked back tears as I made the announcement.

“There is no halfway solution to our problems,” I told the roomful of reporters and employees. In one of the most widely quoted lines from this somber occasion, I added, “There is no chapter five and a half.”

Under our plan, I cut my own salary from $267,000 to $43,000, matching a senior captain’s compensation in our bankruptcy-adjusted pay schedule, and vowed not to allow a raise for myself above this level until the company became profitable. It was a gesture of support for the sacrifices of our returning workers—“founding employees” of the New Continental, as they were soon known in-house. The rest of our officers took modest cuts of 15–20 percent. Of course, since the majority of our employees had been let go in those early days, for what we hoped would be a temporary period, the remaining employees were very happy to be staying with the company.

The risks of filing were several and had to do mostly with matters that bankruptcy laws placed beyond our control. For example, the unions could, and most likely would, seek to have their contracts upheld in the courts and sue us for damages if they could prove that our weak financial position had been exaggerated or that we had filed for bankruptcy simply as a way to slash wages. Another risk was that creditors could persuade the judge to oust current management and leave the job of overseeing our day-to-day operations to a court-appointed trustee. Or, perhaps even more of a legal stretch, we could be left wide open to claims that the separate assets of Texas Air, the airline’s parent company, should be used to satisfy creditor claims at Continental.

We had good relations with most of our creditors, including the major airports as well as our caterer, leasing companies, fuel suppliers, and advertising agencies. We truly were in this together, as we explained. They relied on our continued business, and I expressed to all of them my hope, indeed our goal, of offering favorable terms of repayment. As I explained, our debts to them were not the cause of the company’s problems.

It was an awful afternoon, the darkest (and scariest) moment of my career. Part of me felt like I was giving the eulogy at the funeral of a dear friend, while another part, perhaps more realistic, recognized that the press conference was probably our best and only opportunity to present our bankruptcy in a positive light. I also used the occasion to proudly announce the birth of the New Continental, as I called it—a low-cost airline offering our trademark reliability and service at competitive prices, matching those of other low-cost carriers.

The headlines the following morning were not as bad as some of us had feared, buried as they were on the Sunday news pages. On Monday, most reports included some “expert analysis” of our situation, and the tone of these accounts was generally far more sympathetic than we had any right to expect, although some of the commentary characterized our filing as a strategy for abrogating our collective bargaining agreements. One of the most conspicuous early examples was prominently displayed on the front page of the Wall Street Journal, where an unnamed executive at another major airline offered the following assessment: “If the idea works, why not use it?”

I cringed at lines like these, but we came upon them with such frequency that I eventually stopped paying attention. As we discovered, most of these claims flowed from back-against-the-wall union leaders eager to preserve their positions at all costs, but I was distressed at how quickly reporters picked up on such a one-sided perspective and how easy it was for them to find “anonymous” competitors to repeat the charge.

Following the Saturday news conference, we had two days to reinvent our company from the ground up. We asked each department head to sit down with our officers and go over how to run their operations on a bare-bones budget. With our entire workforce technically furloughed, our department heads (themselves fewer in number) were free to examine their employee files and offer jobs only to their best people. Within seventy-two hours, we needed to cut our workforce down from 11,000 to around 4,000. The alternative would have been to hemorrhage red ink.

Phil Bakes supervised a lot of these sessions for us, and he did a remarkable job. I did not have the stomach or the heart for it. I would see an employee’s name cross my desk and immediately picture his face or the faces of his family—a throwback to my first days at Texas International, when I would often meet employees at the annual company picnic. I had gotten to know some of our people so well over the years that I was too emotionally invested to make some of these hard decisions. Phil could be as emotional as anyone, but because he had only spent a few years with the company, he was better able to take the direct, rational approach that this delicate situation required.

With the labor equation in Phil’s good hands, I escaped the office on Sunday to work on marketing and pricing strategies and map out the changes in flying schedules that I thought made the most sense in our stripped-down condition. I asked our planning folks to do the same thing on their own, and very early on Monday morning we returned to the office to compare notes. This, too, was key. Without approaching the problem from varying perspectives, we wouldn’t have our employees’ full confidence or the buy-in we needed to move forward, but with a consensus operating plan, we could reopen for business knowing we had collectively put our best cards on the table.

Not surprisingly, we all came back with the same basic operating strategy: fly only our busiest routes with increased frequency and at drastically reduced fares. We cherry-picked among our most successful markets, obviously paying attention to what kinds of routes made sense, and wound up selecting the twenty-five cities we would continue to serve. (The scheduling cuts meant that we only needed to deploy around 40 percent of our 107-aircraft fleet.) Of course, it was not enough to simply sustain service in our strongest cities. We had to also play to our strengths and increase the frequency of our flights in those markets. Instead of maintaining our pre-bankruptcy schedule of three or four flights per day at regular fares, we might go to six or eight flights with our new, lower fares; we might even institute hourly service along our heaviest routes. In this way, we hoped to reduce costs, stimulate traffic, and increase our market share dramatically.

The powerful impact that hourly service can have on the marketplace has always been astonishing to me. People tend to fly more when there are more choices, and airlines with a large number of flights tend to draw additional passengers from connecting airlines. I knew that if we could find an economical way to add some sensational fares to our stepped-up frequencies, there would be a better-than-even chance that we would get passengers back onto our planes. The trick was to arrive at a formula for maximizing revenues consistent with our costs, and to reach that equation, we went through a classic pricing exercise.

I sat with our pricing experts around a big conference table and tossed out a series of numbers. “What would happen if we priced every seat at $9?” I asked. The answer, naturally, was that every seat would be filled. “What about at $19?” I asked and got the same answer. We kept on working upward until we reached the threshold where we believed that the chosen price and likely load factors would maximize our revenues. At that time, we were thinking we needed to fly a 70 percent or so load factor in the weeks immediately following our filing, which would have placed us at the industry’s high end—and well above the sub–40 percent load factors we’d been averaging going into Chapter 11. So we determined that we could do so starting at $49 system-wide. From there, we felt we could build our fares back up to $69 or $79 without a significant drop in our loads.

All these developments sent shock waves throughout the airline community. On the afternoon of our bankruptcy filing, Frank Borman released a taped message warning his 37,000 Eastern employees that they, too, must consider meaningful wage concessions or face following Continental into bankruptcy. The Western Airlines president, Dom Renda, also made some bankruptcy noises of his own. For the first time in memory, airline executives pointed openly to the decline of another carrier as proof that the industry could no longer afford its runaway labor costs.

Over the course of that black weekend, my worries drifted from marketing to labor, and at that critical juncture there was no way to anticipate employee support for our filing. The machinists were still out on strike, and our pilots, flight attendants, and nonunion workers were justifiably disenchanted with the emergency work rules and salary cuts we announced.

ALPA’s master executive council initially instructed its members to fly under protest, which left us to assume that there would be more than enough pilots to fill our reduced schedule. That would change later in the week, when the council ordered a strike to commence four days into our resumed operations, and the immediate waffling on the part of the union was either a telling indication of the lack of direction among union leadership or a sign that the national ALPA in Washington had reversed a local union position.

From what we saw, the pilots had no idea what to make of Chapter 11. These ALPA guys in Washington were always a day late and a dollar short, and I do not think they fully grasped what was happening to Continental or to their members. Even after we had filed for protection, they seemed to think our troubles were an elaborate bluff, a negotiating ploy to keep their salaries down and break the union, and it took another few days before they finally took our claims seriously.

However, on that Tuesday, September 27, as we came back flying again, the pilots were still with us, and the New Continental emerged as leaner and far more efficient than any major carrier on the national scene. Our counters were jammed with passengers eager to snap up our $49 one-way fares. Our planes were flying at near capacity, with only minor disruptions, and there were news cameras positioned throughout our system to corroborate our claims that the airline wasn’t dead just yet. I have always been a firm believer in first impressions, and Continental made a great one on its first day back. We were down, but we were not out, and there seemed to be a ready market for the value-driven, full-service product we hoped to offer in the months ahead.

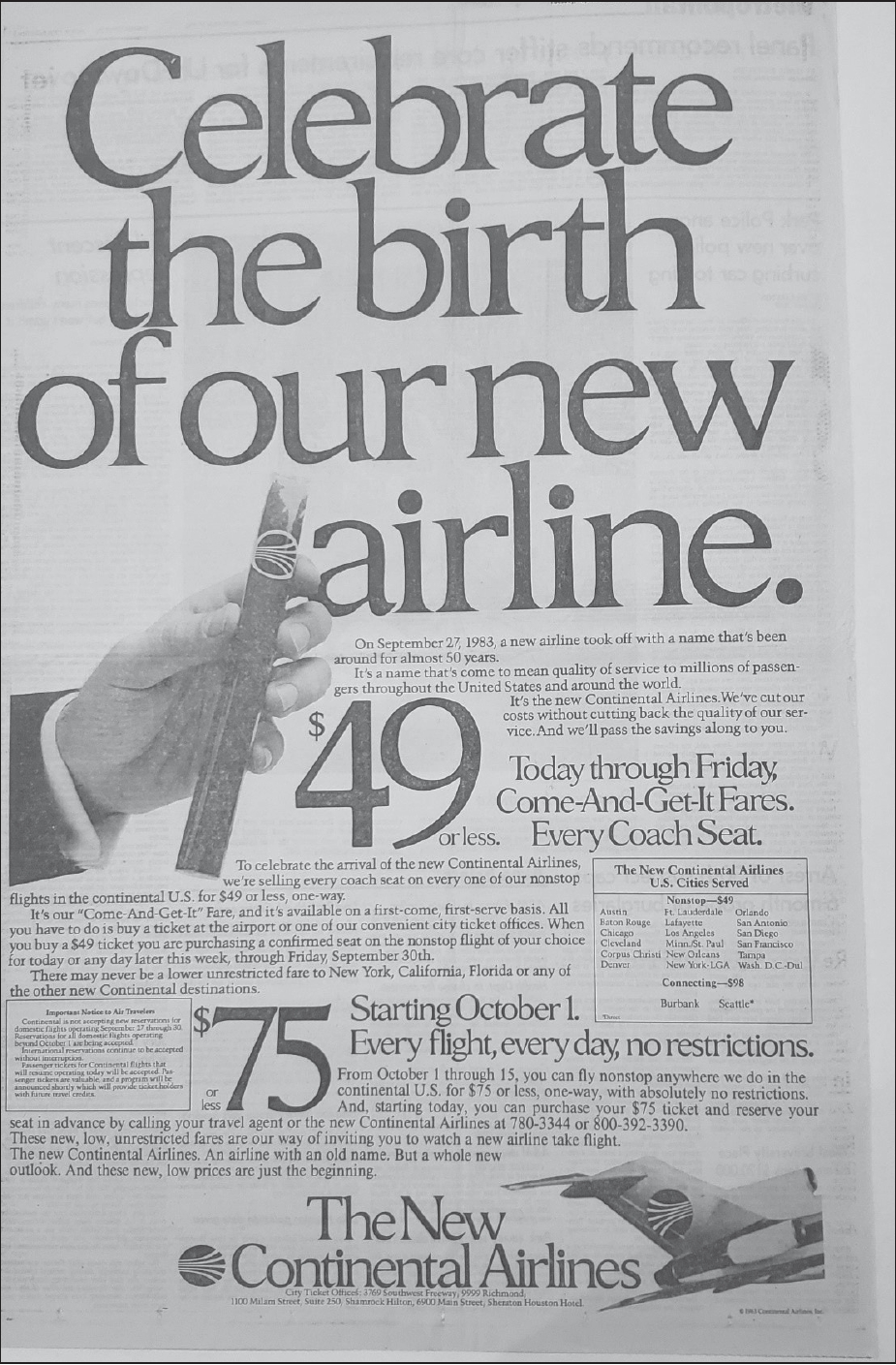

The “New Continental” announcement ad (1983).

With our 2,025 pilots set to strike on September 29, once again we were faced with an uncertain equation. Even at approximately 40 percent of normal capacity, including international operations, we could not be sure that enough ALPA members would cross the picket lines to pilot our planes. The union had put together a substantial strike fund, assessing members between $70 and $300 per month and offering strike benefits comparable to our reduced pay. When captains were receiving $3,800 per month against average salaries of just $3,600 per month—$43,000 annually under our new structure ($134,000 in 2024 dollars)—there was little financial incentive for them to return to work.

We had only offered continued employment to around half our pilots, given our improved efficiency and the fact that we were operating just a couple of hundred flights on our daily domestic schedule, but we were still deeply concerned over what a pilot walkout would do to our pace of recovery. We had hoped that labor peace would enable us to bring the company back far more quickly than we could ever hope to do under strike conditions. But with pilots joining the machinists on strike, we were at odds with our two biggest and most essential employee groups. That would mean our return to full strength would take much, much longer.

For a time, it even appeared that the pilots’ union would take the strike industry-wide. The ALPA chief, Henry Duffy, briefly threatened a walkout of all his 34,000 members, effectively grounding the entire domestic airline industry “as a protest to the government that this industry is not working and needs fixing.” Duffy’s warning was mostly bluster, but we saw it as a clear indication that our situation had struck a nerve. ALPA leaders were undoubtedly concerned over the domino effect our bankruptcy would have on other airlines. To ALPA leaders, 2,000 pilot jobs at Continental were nothing when weighed against 34,000 jobs industry-wide. They were quite prepared to see Continental go down the drain if it meant preserving the existing wages and work rules for their members at other carriers.

In addition, it was becoming clear that the pilots’ union was taking its fight international. Continental was able to continue operating its profitable Australia–New Zealand routes with some of its available pilots, much to the consternation of ALPA. These routes were important to the company because they generated a lot of cash and because a stoppage could cause us to lose our federal route authority. One morning in mid-October 1983, I received a call from our director of Asian operations, Paul Casey, informing me that he had heard from the head of the airport fueling company, who claimed that his employees were not going to be able to fuel our airplanes. It seemed that the fuelers’ union had been visited by ALPA representatives from the United States, and the fuelers planned to honor the ALPA picket line.

Well-paid, striking Continental pilots unhappy with their wages (1983).

Our options were limited, naturally, because we were 8,500 or so miles away. However, I had an ace up my sleeve in the person of Lindsay Fox, one of Australia’s most successful entrepreneurs. I had met Lindsay when he chaired the YPO meeting in Melbourne two years before. (YPO, formerly the Young Presidents’ Organization, is an association of young chief executives from around the world.) I had recently invited Lindsay to join Continental’s board, too: it seemed to me that we should have representation from the Asia-Pacific region given that it was such a valuable route for us. Anyway, I called Lindsay after hearing from Paul Casey; I explained the problem to him and asked if he could help.

Lindsay, a classic entrepreneur, had a very interesting background. Starting as a driver, and later with a rig of his own, he built a thriving trucking company, Linfox, which went on to become the largest logistics company in Southeast Asia. His several thousand trucks could always be recognized on the road by the message written on the rear: YOU’RE PASSING ANOTHER FOX. He certainly knew his way around and was friendly with a great many of the union leaders. In any event, Lindsay said, give me a little time, and I’ll see what I can do.

A few hours later, Paul Casey called back to say that the problem had been solved. It turned out that Lindsay had found his way to the general secretary of the transport truckers union and told him—in his always friendly way I’m sure, at least initially—that he hoped the truckers would fuel our airplanes, because if they didn’t, his drivers would. Done and done!

Lindsay remained a critical director during my time at Continental, invariably offering sound advice—even though it was not always what I wanted to hear.

During the ALPA strike, our ability to fly depended upon our ability to persuade pilots to cross their own picket lines. The best way to do this, we determined, was via a direct, one-to-one appeal, so we set up a room in our headquarters with a bank of phone lines, and we all took turns calling the pilots to explain our position and ask them to return. It was a real boiler-room operation, and our pitches were as intense as any sales call. I was in there with the rest of our group, working my way down the list, talking to pilots about what we were trying to do, what we saw the union trying to do, the positive direction we thought the company was headed in, and our commitment to taking it there.

Most of our calls took place in the evenings, after the dinner hour. With our pilots scattered in time zones all across the country, we stayed on the phones well into the night. It was challenging, frustrating work. Not only were we attempting to address some very valid concerns (increased hours, reduced wages, questions over seniority, and the legitimately suspect financial health of the company), we also had to counter an extensive union program of misinformation. ALPA leaders had their own bank of phone lines, and they were matching us call for call. It is only now that I can fully appreciate the absurdity of the situation. Imagine two groups of people, each holding diametrically opposed views, waging a long-distance tug-of-war using individual pilots as the rope. On some calls, I had to undo a whole lot of damage before I could get the pilots to really listen. It was often a futile exercise, but we had to go through it anyway.

For all our efforts, there were some nights when we could only persuade a dozen or so pilots to return to work. There were barely enough pilot turnarounds to keep us in business. On October 1, the first day of the ALPA strike, 120 pilots crossed the picket line, and we were forced to cancel 15 of 118 scheduled domestic flights. By the following week, after a few dozen more pilots had come over to our side, there were no strike-related cancellations, and we started to think we’d dodged a bullet.

It was no easy thing for our pilots to cross the picket lines and fly our planes. ALPA leaders and strikers were not exactly known for their subtle ways, and some of their methods bent the law. This was an all-out economic war, and if ALPA could not win the battle by conventional means, its leaders seemed perfectly willing to fight it out in the trenches. And they fought dirty. They terrorized our non-striking pilots in a manner that I could hardly believe, following them to their hotel rooms on their overnight assignments and trying to persuade them to desert their aircraft the next morning. They threatened their homes, their families, and their future livelihoods. They told these pilots they’d be blacklisted—that once Continental buckled to ALPA demands (and until that time, airlines had always ultimately buckled to ALPA demands), they’d never get another job with the union. We got a lot of last-minute calls during this period from pilots asking to be pulled from the schedule, and no doubt most of those calls resulted from union pressure.

Two notorious incidents added weight to the persistent ALPA threats. One involved a non-striking pilot in Denver who reported that a stuffed elk was thrown through his living-room window by striking colleagues. It was like a scene out of a movie, but it sent an emphatic message throughout pilot ranks. The other incident was even more disturbing. At a roadblock set up to stop drug trafficking in the area, San Antonio police stopped two striking Continental pilots allegedly on their way to bomb the home of at least one non-striking Continental pilot. In their car, the cops discovered bundles of dynamite and road maps highlighting the locations of non-strikers’ homes. On further investigation, it was revealed that these two pilots were out to exact revenge on their working colleagues, and they wound up serving prison time for their intended crimes.

We saw labor peace as critical to Continental’s recovery, so we continued to negotiate for an agreement with the pilots’ union even as these threats and reports of violence persisted. I could think of no way to reason with unreasonable people, but there was no way to avoid trying, either. However, after reading what was going on in the newspapers and listening to the horror stories brought in by our loyal pilots, we concluded that it was impossible to pursue negotiations.

One of ALPA’s favored ploys was to announce that our planes were unsafe without its pilots at the controls. This was nonsense, but it is the standard union line during any airline work stoppage. Regrettably, it was sometimes effective, because Americans look at airline pilots in much the same way as they look at doctors, attorneys, and other highly trained professionals. When any such group declares that the public is in danger, people take these warnings very seriously. ALPA took advantage of this whenever possible, presenting itself as an authority on matters of public safety just as, say, the American Medical Association does. I always thought that even its name, the Air Line Pilots Association, was chosen to reinforce that image of responsible, educated professionals when in fact ALPA is a labor union just like any other—except with much more money.

After so many years of practice, the union—which was formed in 1931—had elevated its brand of self-serving propaganda to an art form. One of the most devious ways ALPA leaders did this was to establish an internal “safety committee” that ostensibly monitored the standards and practices of airlines. In reality, the committee appeared to have little interest in investigating those airlines with which the union enjoyed good relations, thanks to a compliant management team. Somehow, the only reports issued by this body had to do with airlines whose management was trying to keep labor costs in check and respond to the competition brought about by airline deregulation. The committee was promoted as a body for ensuring public safety when all it really safeguarded was ALPA members’ benefits, work rules, and wages—and, most importantly, the union’s security and continued existence.

ALPA’s safety inspectors worked overtime to take every incident out of context and trumpet it to the press, thus feeding the strike and undermining Continental’s reputation. They ran full-page newspaper advertisements dramatizing the most innocuous everyday occurrences. Naturally, every airline has incidents during operations, but only a fraction of them present a problem of genuine concern.

Unfortunately, we suffered one serious but ultimately harmless infraction of air safety procedures just a few weeks into the pilot walkout, giving new ammunition to ALPA’s claims. By coincidence, I was flying from Houston to Denver on a Continental DC-9 helmed by a senior pilot named Mike Woods. I had known Mike, ironically, as an ALPA regional leader and a very vocal opponent of management. In fact, the last time I’d seen him, we were in discussions with the union over the start-up of New York Air, which he opposed. I was somewhat surprised to see that he had crossed the ALPA picket line, and when I found out he was piloting the plane, I made a point of paying him a visit in the cockpit.

“Mike,” I said when I went up for a chat, “I’m glad to see you supporting the company.”

“You’ve taught us, Lorenzo,” he said. “You’ve given me religion.”

“How so?” I asked. I was curious to hear what part of our message had resonated with him.

“I’m finally realizing that the company needs change,” he allowed, “and we’re not going to get it from ALPA.”

We spoke for several minutes, and when we began our landing approach into Denver, I excused myself and returned to my seat. I never wanted our pilots to worry about my presence as we came in for a landing, a time when pilots are very busy, but I was in the cockpit long enough to see the sun shining brightly off the fresh snow at the airport. It was a beautiful clear day. Mike put the plane down gently and rolled to a stop, and there was no indication that anything had gone wrong.

After the flight, I had to run to a tightly scheduled editorial board meeting at the Denver Post, at which I planned to update the editors on the New Continental. So I charged off the plane and headed for the newspaper’s downtown offices. By the time our meeting broke, some ninety minutes later, there was a handful of reporters milling outside on the street in front of the building, wanting to know about the landing incident on my flight into town. “What’re you talking about?” I asked in the text-message-free environment that existed then. I honestly had no idea. As far as I knew, it had been an uneventful flight on a bright sunny day.

I learned later that only two of Stapleton’s three runways had been clear and operational that day, thanks to a heavy snowfall the day before. The runways were about 900 feet apart, and each was about 120 feet wide. A taxiway, at a width of 75 feet, ran between them, and this, too, had been cleared of snow. Mike had been told by controllers to land on the “middle runway” as our plane approached, but no mention was made that Denver’s third runway was concealed, covered with snow. So Mike landed the plane on what appeared to be the middle runway—the cleared taxiway between the two visible runways.

By the following morning, ALPA’s well-oiled public relations machine helped ensure that the story of this accidental yet obviously very improper landing, no matter how understandable it was, was making national headlines. No one had been hurt, no damage had been done, and no one at Continental was proved negligent in any way, but the union turned it into a big story just the same. To be sure, an incident of this kind requires an FAA investigation, if only to ascertain why the air traffic controllers used such imprecise language while providing runway instructions. However, the amount of play this story received was out of all proportion to what happened, and the finger was pointed far too quickly at our pilot. Even the New York Times termed the incident “a special embarrassment” to Continental.

Henry Duffy, ALPA’s chief, had a field day with the misadventure. “We have maintained from the beginning,” he said in a statement, “that the work rules imposed upon those pilots still flying for the new Continental and the immense pressure they are operating under would unquestionably cause a serious and rapid degradation of safety. This isolated incident at Denver is only a further example of why we have been warning passengers not to fly on the new Continental.”

What was so infuriating about Duffy’s remarks was that he neglected to acknowledge that strong-arm tactics by his own union forces were largely responsible for whatever pressures our pilots were under. He also failed to mention that until a short while before, Mike Woods had been one of ALPA’s most loyal leaders. Just because Mike had committed the cardinal sin of working despite a union job action, he had not been transformed from a competent pilot to an incompetent one. It was astonishing to me how quickly the union would sell out one of its own.

The negative attention from the Denver landing died down soon enough. The FAA found insufficient grounds to sanction Mike, and Continental, in our examination of the incident, also decided that Mike’s mistake did not warrant punishment. But ALPA did achieve its goal of stoking passenger fears and putting a dent in our reputation.

I honestly believed that Continental was the safest airline in the skies in those days, because in my view (which was also shared by aviation experts), pilot complacency is one of the biggest enemies of airline safety. Our pilots had few reasons to be complacent. With their striking colleagues and union pilots in other airlines watchdogging their every move, they needed to stay sharp. Furthermore, our operations and maintenance facilities were on high security alert, so vandalism and sabotage were never a serious concern. I have always said that if ALPA really considered safety its number one concern, then perhaps it would not be so quick to defend some of the most egregious instances of pilot error.

On November 23, 1983, the birth of our son offered a welcome respite from all these struggles. This would be our fourth trip to the delivery room, and I thought I had it all figured out. That day, I arrived with a video camera and tripod, because I did not want to miss a thing, but Mother Nature had other plans. After Sharon experienced some irregular contractions, our fourth child was delivered by cesarean section in a room from which I was excluded. I was just thrilled that mother and child were healthy.

We named our son Timon, a family name on my mother’s side, a discovery that Sharon and I made on that years-ago trip to the cemeteries in my parents’ Galician village. For his middle name, we chose Francis, after Sharon’s grandfather (and, happily, after the English version of my birth name, Francisco). I never really thought all that much about having a son or a male heir. If I thought about it at all, I just assumed that the baby would be a girl. After three beautiful daughters, I did not know anything else, and I could toss a baseball around with my girls just fine.

After Timon, though, I could not imagine life without a little boy. He was a wonderful surprise and an incredibly easy baby, even from the very beginning. The girls were captivated by their baby brother. He was like a little toy to them at first, but as they all grew up, it was quite heartwarming to see the way they looked after him. We took him on a transatlantic flight to London before he was two months old, and he did not give us a peep of trouble—he slept in his straw basket, which we had gotten in Mexico, just next to our bed at the Connaught Hotel. All our kids were terrific travelers at early ages. I suspect they got that from me.

I still look back fondly on the 1983 holiday season for many reasons, including the fact that Timon’s arrival coincided with the first signs of life at the New Continental. Even after we ended our special promotional fares, our load factors continued to outpace those of the competition, at 67 percent in November and 63 percent in December. Scheduled flights climbed to more than 50 percent of our pre-bankruptcy level, and our cash position improved significantly.

Continental fares remained a bargain, with two-digit price tags throughout much of our system. The new pricing strategy called for a simplified two-tier fare system modeled on Southwest’s highly successful fare structure, which was also being adopted at People Express and the rejuvenated Braniff, which finally returned to the skies in 1984, after its 1982 bankruptcy. We went with a straightforward peak/off-peak plan and shunned the complex yield management pricing system used by most carriers to this very day.

Back then, yield management systems were not nearly as sophisticated as they are today, but they had already become a source of some controversy—and the bane of most travelers’ existence. When seats in coach class on a single flight are priced at, say, $320, $249, $199, and $110, consumers find it very difficult to comparison shop. The low come-on fares are saddled with so many restrictions that passengers never really know if they qualify for them, assuming they can even find them.

Simplified fares were very much in line with our new basic service philosophy, and they helped reinforce what we hoped had become the airline’s new image as a value-driven carrier. Rather than arriving at an average $69 fare for a given flight by charging $199 for some seats, $99 for others, and $59 for most of the rest (with perhaps half a dozen at $39), we just went ahead and charged everyone $69. Alternatively, we could get to the average of $69 by charging $79 during the week and $49 on the weekends. It was, we thought, a dignified, rational way to separate ourselves from the competition and reward our passengers without insulting their intelligence.

Of course, this has all changed now. Computer algorithms determine fares, which may change by the hour or time of departure based on demand and other factors. Airlines, particularly the large carriers, generally avoid advertising their prices. When they do, they usually announce something like “as low as . . .” instead of a specific fare.

In addition, as we approached the 1983 holiday season, we began adding new flights so frequently that we were running short of pilots. For the first time, we were forced to make permanent pilot hires from outside our ranks, enrolling forty new pilots in our training program. We had no other choice if we ever hoped to return to our pre-bankruptcy schedule and build the New Continental. Our talks with ALPA had reached a total impasse. Although many claimed that these forty hires constituted our attempt to bust the union, we were continuing our plan to bring back Continental and respond to market demand for more flights, fulfilling our obligation to pay our creditors and making it possible to bring all our furloughed employees back to work.

With these outside hires—who had the option to join the union but who usually decided against it, seeing as how the union wanted them out—negotiations with our pilots came to an effective halt. Predictably, ALPA insisted that in the event of a settlement, we should furlough these new pilots immediately, but we couldn’t agree to that. The only way we could persuade these outside pilots to cross ALPA’s picket line and sign on was to make a commitment to them. We guaranteed that their jobs would survive any settlement, and we couldn’t afford to go back on our word simply to satisfy another in a long list of demands by our striking pilots’ union.

These outside pilot hires created several potential complications (involving seniority rankings, for example), but we could not hold so many jobs open indefinitely. We needed to increase our number of flights to generate cash flow and prevent our lessors from taking back their idle aircraft. As far as I was concerned, if a striker tired of the fight and wanted to return to work, we would gladly have him, but only if there was a job available. We refused to displace one of our new hires to make room for a striking pilot who had suddenly “gotten religion,” as Mike Woods might have put it.

On January 17, 1984, the courts delivered good news that clarified our labor outlook. The federal bankruptcy judge in Houston who was handling our case, Judge R. F. Wheless Jr., declared that the airline had not acted in bad faith when it filed for protection from creditors. This was an extremely critical decision for us. Had we lost this case, we would have had to offer back pay to strikers and reverse the steps we had taken to improve the survivability of our operations.

Then, on February 23, the US Supreme Court delivered a narrow 5–4 decision in what was widely called the Bildisco case, which upheld the right of bankrupt employers to set aside existing labor contracts and impose new wages and work rules. The court’s decision, in a highly disputed case not directly involving Continental, effectively neutered the labor unions’ last remaining chance to invalidate our new contracts.

But the unions didn’t stop there. They pushed hard for legislation in Congress that would not only prevent changing labor contracts in bankruptcy but would also apply this legislation retroactively to any bankruptcy cases then outstanding, including ours. I remember getting a panicked call from our Washington-based lawyer, Clark Onstad, asking me to fly to Washington and meet with our Texas senators as well as with my business-school classmate John Heinz, Republican senator from Pennsylvania, and others in an attempt to head off an amendment to a bill that was moving through Congress. This amendment would have provided the retroactivity that the unions sought. Fortunately, our congressional representatives were able to see through this, despite the unions’ intense lobbying. I have very fond memories of a wink I got after the committee showdown on the bill from Lloyd Bentsen, the highly respected Democratic senator from Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, as he was walking down the stairway from the committee room. It was all clear on that front for a while.

On the ground and in the air, the New Continental exceeded our most optimistic projections for recovery. Even in the press, where liberal journalists castigated management and portrayed me as an enemy of organized labor, there was no denying our turnaround. A lead editorial in the February 17, 1984, issue of the Denver Post, written in response to a push from labor groups seeking to amend the laws after Judge Wheless’s decision, offered perhaps the best example of the way in which our comeback was being reported: “Free enterprise isn’t supposed to be a popularity contest,” the editors wrote. “We’d rather have rough, abrasive Frank Lorenzo playing the game by the rules and saving consumers money in the process, than watch [others] rewrite them at public expense.”

Of course, we could not always rely on such favorable reports. I much preferred to let our performance speak for itself—and it did. In the first quarter of 1984, we posted a small operating profit, and by the second quarter we were able to point to a net profit of $10.4 million. By April, Continental had rebounded to the point where I felt I could comfortably relinquish the day-to-day controls, and I tapped Phil Bakes to succeed me as president and chief operating officer. I remained as chairman and chief executive, but I left it to Phil to guide the airline in its operations, a role he had been exposed to since the bankruptcy.

In addition to focusing on marketing and legal issues, we focused heavily on our relations with employees. We felt it was critical to reward those who had taken substantial pay cuts in the wake of the bankruptcy, so we offered them direct grants totaling one million shares of the company’s stock, stock option opportunities, and a well-received profit-sharing plan. We also formed employee councils and encouraged employees to participate in the management of the company, a move made possible by the elimination of the layer between management and employees that was usually occupied by union representatives. We even established a motto: “Every employee who wants to participate in management can.”

We had planned to restore the airline to 90 percent of pre-bankruptcy capacity by midsummer of 1984, but we were pleased to be able to reach that level in early May—barely eight months after our bankruptcy filing. Our costs per available seat mile had fallen to less than 6.5 cents compared to pre-bankruptcy costs of 8.5 cents. That decrease may not sound like much, but whacking nearly 25 percent off our operating costs was huge. Our labor costs at that point constituted only 21 percent of operating costs, in line with our lower-cost competitors—down from 35 percent at the time of our filing. By midyear, we were carrying more passengers than ever before while serving only half as many markets, and our load factors continued to lead the industry.

In October 1984, when our third-quarter results were reported and we achieved a profit of $30.3 million on operating income of $43.8 million, we really knew we had achieved something extraordinary. Our available cash and equivalents had soared to $126.8 million. Within one year of our filing, Continental had accomplished a complete turnaround in its fortunes. Steady, continued growth had brought us back to a workforce of more than 10,000 employees, while labor costs had been reduced by an astonishing 45 percent. We were operating 120 percent of our pre-bankruptcy seat miles. Though still in bankruptcy, Continental had been reborn, not only as the industry’s largest and most popular low-cost carrier but also as the only low-cost carrier with a long-established reputation that provided a full-service product.

However, we knew we had to continue to increase the breadth of our operations organically while the opportunities still existed. To do that, we needed additional aircraft. But the unions fought us at every turn. We went to Boeing and placed an order for twenty-four 737-300 aircraft, which were to be leased, to fill out our hubs. This required approval from the bankruptcy court, although since the planes were to be leased and the company was doing so well, the creditors—other than the unions—didn’t have any complaints.

In addition, we bought four DC-10 aircraft to increase our international service, and the unions tried to stop this, too. One of the aircraft was to be used for a new route from Houston to London, replacing Pan Am, which had lost the route. The unions tried to stop us in the courts and in Washington. The pilots’ union even went to London and attempted to get the heavily unionized London companies to refrain from servicing our aircraft. The fight to build Continental internally through aircraft acquisitions, while still in bankruptcy, was so unusual that Harvard Business School wrote a case for its students describing the situation. When this case was taught, I was invited to speak to the class.