CHAPTER TEN

Eastern Airlines

The Final Union Standoff

1985–1990

IN THE fall of 1985, our unsuccessful run at TWA made us more aware than ever of our need for an advanced computer reservations system. If we wanted to be able to fully compete with the major carriers, we would require a sophisticated modern system that would give us direct access to travel agents across the country. When TWA’s PARS system passed into Carl Icahn’s hands, I set my sights on the only workable alternative that remained—Eastern’s System One. Although System One was not as technically advanced or as popular as American’s SABRE or United’s Apollo system, it was an enormous improvement over what we had, and there was a chance that it was up for sale. The airline’s well-known labor troubles had pushed Frank Borman’s company to the point where raising cash through an asset sale loomed as an important option. Selling System One, with Eastern staying on as its major client, seemed like it was possibly in the offing.

To follow up, I arranged a meeting with Borman in New York on November 20, 1985. When I arrived, I felt like I was retracing my steps as I entered the Eastern offices where I’d worked twenty years earlier. The offices at 10 Rockefeller Plaza, overlooking the famous skating rink where I had proposed to Sharon thirteen summers before, were as unassuming as ever. Even the secretaries looked familiar, and I smiled in recognition as I strolled the halls to the chairman’s office.

Despite the rumors of a potential asset sale, it was clear from the outset that Borman wanted to talk about more than Eastern’s computer reservations system. In the years since Apollo 8, he had understandably aged just a bit from the way I remembered him from the news accounts. His hair was somewhat thinner and turning white, and he didn’t hide his wrinkles. He quickly steered the conversation to Eastern’s overall financial situation. The airline had lost nearly $1 billion over the previous seven years, and it looked like 1985 would see more losses. By year’s end, Eastern would carry more passengers—and lose more money—than any other airline in the world.

Borman was looking for a merger partner to help Eastern avoid bankruptcy, which he saw as getting ever closer. Apparently, he thought Continental might fill the bill. I was surprised he solicited us for a deal, even if it was out of desperation, and was intrigued at the turn the meeting had taken. Still, I was flattered and said we would be pleased to have a look. I did not know it at the time, but Borman and his bankers had already been to nearly every other major airline with the same pitch. The only interest seemed to have come from Don Burr, even though his airline, People Express, had just swallowed Frontier and was faltering on its own.

After the meeting, Borman and his team supplied us with a mountain of financial data, and along with a couple of our key managers, we analyzed the numbers back in Houston. Clearly, the biggest drain on Eastern was its out-of-control labor costs; Borman’s persistent inability to make progress in this area was well documented. Eastern’s baggage handlers, for example, earned an average of $48,000 ($138,000 in 2024 dollars) plus benefits, nearly what fully trained mechanics made in the same union. At American, in stark contrast, CEO Bob Crandall’s newly implemented two-tier wage structure allowed the airline to hire baggage handlers at around $16,000 ($65,000 in 2024 dollars), which was the going rate in the “outside” world at the time for this type of work.

Even when Borman had been able to win short-term concessions from his unions, as he had with a twelve-month wage freeze earlier that year, he did so simply by agreeing to the sorts of snapback provisions we had always rejected in our own negotiations, since they specified that everything at the end of the contract would return to the way things were before the agreement plus the wage increases and other provisions that had been negotiated for the period on productivity. On January 1, 1986, when the freeze lifted, Eastern employees would automatically receive a 20 percent salary bump, wiping out the savings of the one-year freeze in just a few weeks and putting the airline back on course for financial ruin.

It was alarming to see just how many facets of Eastern’s business were unprofitable. On a route map, Eastern had a great franchise. There was the Atlanta hub, in competition with Delta. Eastern “owned” Florida, and it had a solid north-south franchise along the East Coast. There were focus hubs in Philadelphia and Charlotte. The shuttle was considered a crown jewel by employees and by many outside Eastern. And there was the midcontinent focus hub in Kansas City.

But the fancy route map was deceiving. Florida was more of a low-yield leisure market than a high-yield business market. Orlando, where Disney World is located, is a huge family vacation market. Miami is, to this day, a huge cruise ship destination, another vacation market. Eastern’s positions in Philadelphia and Charlotte were okay but not great. The Kansas City hub was developed more as a package-freight connecting point, perfect for its big Airbus A300s, than as a true passenger connecting hub.

The best part of Eastern, other than the shuttle, was its Latin American route system. Borman had bought the system from a failing Braniff even as the latter carrier was hours from shutting down in bankruptcy. Since deregulation, most of the airline’s profits outside the shuttle came from selling off assets. Nevertheless, we initially determined that Eastern still had net assets (total assets, minus debt and other liabilities) of more than $2 billion compared to an equity market value of only $400 million. The airline’s underlying financial asset strength was so substantial that we thought we could ultimately use it to finance part of our acquisition and gain a great amount of financial flexibility in case it took longer than we anticipated to effect the needed change in labor costs.

Eastern had many attractive strategic assets, too. In addition to its shuttle operation and computer reservations system, it had the most landing slots at LaGuardia and Washington National Airports. It had the largest route network in South America of any US carrier, and it boasted some of the most attractive airport space, particularly in its key Florida markets. Most important, as far as we were concerned, was the fact that Eastern’s system did not substantially overlap with any of our core operations except New York Air’s lucrative shuttle markets, thus making antitrust clearance more straightforward.

We could not afford to let this one get away. With both TWA and Frontier behind us, Eastern was the only remaining airline deal that could provide us with the critical mass we desperately needed to grow to the next level—the long-term-survival level, as we saw it. It was also available at a seemingly affordable price. To follow up on our New York meeting, I arranged a dinner meeting with Frank Borman at a hotel in Fort Lauderdale in early December.

The small one-bedroom Marriott suite where we met had a rectangular conference table. When Borman arrived, he sat himself at its head. I took the seat at his left elbow. Because he said he was pressed for time, we bypassed the entrées on the hotel menu and ordered only sandwiches and soft drinks.

The colonel’s demeanor was wary, almost cold. I had the feeling that his lawyers had told him to proceed with extreme caution. He began with a short speech, which sounded rehearsed. “I’m only here to listen,” he said, “and to answer questions. I’m not interested in hearing any specific merger proposals, and I’m assuming that whatever passes between us will stay in this room.” Of course I agreed.

Then, once we were done with the formalities, I ignored Borman’s prepared speech and laid my cards on the table. I told him we were prepared to consider the purchase of Eastern Airlines at a premium meaningfully above the market, and of course we knew that Eastern’s stock had fallen a lot in prior weeks given the company’s problems. Borman’s mood brightened almost instantly. Disregarding what was likely his legal advice, and moments after warning me that he didn’t want to hear a specific proposal, he asked about a price. I told him that we would have to study the numbers and market information, but it would probably be similar to the substantial market premiums common to other acquisitions.

As we talked on, Borman’s apprehension faded, and so did his heroic mystique. I realized that there was nothing cunning or calculating about the man sitting next to me. Borman seemed utterly without guile. While perhaps this is not always a good trait in a chief executive, it’s a welcome characteristic in someone with whom you’re negotiating, particularly in this type of situation. I didn’t think Borman had it in him to lie about his intentions. If he did try to misrepresent something, I doubted he’d be very smooth in concealing it. The way he reacted to the general price discussion told me that we were getting somewhere.

We concluded our brief meeting with a handshake at the door. Borman said he’d need some time to sort through his options, then he headed home in his pickup truck. I got the impression that he was not yet resigned to selling Eastern. The flight commander in him still wanted to succeed in the primary mission of saving the company. But for Borman, Eastern might well have been beyond saving. For too long, its union leaders lacked the resolve to make desperately needed changes to the company’s cost structure. Eastern’s labor contracts, with their impossibly rigid work rules and high pay scales and benefits, had made it impossible for the company to run profitably on routes that had low-cost, low-priced competitors. In the previous few years, most of Eastern’s profits had come from selling off assets. Whether Borman was ready to accept it or not, the day of reckoning was near.

I went downstairs to pay the bill—$321 for the room, $50.80 for dinner—and hopped in a taxi back to the airport. The whole time I was thinking that it didn’t matter whether we merged Eastern with Continental or continued to operate each one separately. The overall size and scale of the Texas Air group, aided by System One, was what mattered. In my view, every carrier faced a simple choice at the time: hunt or be hunted. The advent of airline deregulation had made that an inevitability. A shakeout was already underway, and not everyone would survive.

We waited to hear back from Eastern through the holidays and into early 1986.

Borman faced two critical deadlines in February, either one of which could force the board to sell the company. February 26 was the date on which Eastern’s 4,600 pilots and 7,000 flight attendants threatened to go on strike unless they had a new contract, and on February 28, Eastern faced technical default on $2.5 billion in loans unless it could obtain significant wage concessions from its unions. Those were Borman’s points of no return.

Eastern shares reached new lows in January as Wall Street appeared to lose faith in Borman’s ability to turn the company around. In fact, the stock was trading so low that it was attractive on its own, even without a deal. We began to consider acquiring a toehold stake in the airline. I didn’t think it made sense for us to sit on the sidelines without any stake if there were to be a deal of some kind without us and the stock took off.

In early January, having heard nothing more from Eastern, we began purchasing Eastern stock in modest blocks, at just over $6 per share, being very careful not to disturb the trading market, and kept buying until mid-February, when our nearly three million shares put us at the 4.9 percent ownership threshold. However, on Sunday, February 16, Jeffrey Berenson, an investment banker engaged by Eastern, tracked me down in Acapulco, where I had escaped with the family for the Presidents’ Day vacation week. It was eleven o’clock in the morning, and I was sitting with a book on the balcony of our two-bedroom suite. Sharon answered the phone, and when she told me it was Berenson, I asked her to tell him I was out. I wanted some time to think things through before talking.

I didn’t know Berenson terribly well before these talks. We had only spoken twice on the telephone regarding our interest in Eastern, but I was comfortable dealing with him, because he seemed like a competent banker. He seemed to be a straight shooter who knew how to keep his mouth shut—a rare feature, I was finding, in the investment banking community.

When I called Berenson back, he told me that the Eastern board was planning to meet on Friday. “There’s a chance the board will call on you to make a formal offer,” he said. “I need to know if you can put one together by that time.”

“We certainly maintain our interest,” I said. “If you call us on Friday, we’ll see where we stand.”

I was not being coy or playing hard to get. There was general consensus among our group that a bid for Eastern made sense, if made on the right terms, although Phil Bakes—Continental’s president, a director of Texas Air, and a close confidant of mine—had initially expressed reservations, comparing Eastern’s union situation to a cosmic black hole from which we might never return. (Little did Phil know then how right he would be.) But his views had evolved to the point where he saw a lot of value in the deal. Still, we were a long way from structuring any kind of offer.

I cut my Mexican vacation short and flew back to Houston, where for three days we turned the conference room at Texas Air’s corporate offices into a command center. There we looked at every aspect of the deal from every angle. On Friday, as we expected, Berenson called from Miami to say that he had been directed to seek a proposal from Texas Air. He waited until four o’clock, after the stock market’s closing bell, before placing the call. Eastern shares had ended the day at $6.375, and with the market closed for the weekend, this figure would stand as the market price for the balance of our negotiations.

We didn’t know it at the time, but Eastern’s directors had heard some alarming reports at that day’s board meeting. The airline’s January losses totaled $48 million, and projections for February showed a loss of more than $58 million. Without an infusion of outside cash, it was only a matter of weeks before the airline would have to file for protection from its creditors under Chapter 11.

As soon as I hung up with Berenson, I sat around our walnut conference table with Rob Snedeker, Charlie Goolsbee, our general counsel, and Bob Ferguson, our top dealmaker, to go over the specifics. We were joined on the speakerphone by Gerry Gitner, who had worked with us in the early days at Texas International and had left with Don Burr to form People Express, only to return as Texas Air’s president after growing disillusioned with Burr’s quirky management style. We also sought advice over the telephone from key board members Carl Pohlad, Rob Garrett, Jim Wilson, and Lindsay Fox. Bob Carney also gave us his views.

We discussed our various options for around an hour. We considered a deal for 80 percent stock, then one for 80 percent cash, then one for 50 percent of each. We tried to look at each alternative from the perspective of the Eastern board and anticipate their concerns while still leaving us some room for negotiation. Then we debated the actual price of the deal, using the closing stock price as our guide.

Finally, with a framework for a deal in place, I called Berenson and told him we were prepared to make a formal proposal under which Texas Air would acquire Eastern Airlines. There was, however, one important condition: our offer would be open only until midnight on Sunday. By 12:01 a.m. on Monday, I told Berenson, we would walk away from the table, deal or no deal. “If you can live with that structure, we’ll call you later with a specific proposal,” I said. “Otherwise, we can just end it here.”

It was a potential deal-breaker, I knew, but the short deadline was essential for us. As it was, our bid would become public once our offer was formally presented to the Eastern board. One of the trade-offs Borman had granted the unions in return for earlier concessions was the awarding of four seats on the board to members of Eastern unions. Those four directors were not going to sit on the news of any potential buyout, especially not news of an offer from Frank Lorenzo’s Texas Air.

“I think we can live with that,” Berenson replied. “I’ll be expecting your call.”

An hour later, with the approval of our board, I called Berenson back and outlined our deal. We would pay $9.50 per share—three dollars in cash and the balance in stock—bringing the total value of our bid to around $600 million. The price was nearly 50 percent more than Eastern’s market value at the time but still far below the $2 billion in net assets we had estimated in our review.

At this point, I was eager not to make the same mistakes we had made with TWA. If the Eastern board voted for our deal, as the board at TWA had done, I wanted to make it extremely difficult for someone else to take control of Eastern’s shares in the marketplace. So in addition, Texas Air would immediately purchase 12 percent of Eastern stock (the maximum amount the board could sell us in one block), which would combine with our toehold position to effectively block an outside investor. Texas Air would also be entitled to a $20 million fee, in cash or stock, whether we ended up with the airline or not. Such a large breakup fee would make Borman reluctant to use our bid merely to strong-arm his unions.

Berenson did not choke on our terms, which I took as another good sign. But I could not wait around with the rest of our team to hear Eastern’s counteroffer. It was Friday night, and I had promised to take Sharon and our daughters to the movies. Too often, I have found, the easiest appointment to break is the one you make with your family. But on this night, we would have all been better off if I had taken a rain check, because I was not much company. Out of Africa, with Robert Redford and Meryl Streep, simply couldn’t hold my attention. I probably made a half dozen phone calls from the movie theater lobby, where there was a pay phone, each run disguised as another popcorn or soda trip, to check and see if there was any news. There was none. I should have relaxed and enjoyed the movie.

At seven o’clock on Saturday morning, Berenson woke me up in Houston to pass along the word from his board. “The proposal is too light,” he said. “There’s not enough cash in it.”

“What are you looking for?” I asked. By this point, I knew Berenson as a no-nonsense guy, and there was no reason not to get straight to the point.

“I’m looking for Eastern’s shareholders to at least get the current stock price in cash,” he said. He also said we needed to bump up the overall price of the deal. We had left some room in our initial bid, expecting the investment bankers to come back and seek a little bit more. It was a clever approach, and I was inclined to see it his way.

“We might be willing to go to ten dollars per share,” I said, “and increase the cash component to six dollars and twenty-five cents. But that’s it. We’re not prepared to do any better.”

Berenson said our counteroffer was “responsive,” which I understood to mean he thought he could sell it to Borman and the board.

Next, I called our guys in Atlanta, where it was almost nine o’clock in the morning, to bring them up to speed. Snedeker and company, who had traveled to Atlanta in the evening, reported that they now felt we were being used. They had just arrived at the law offices there but already had reason to believe that Borman was selectively informing the unions that we were prepared to bid for the airline and trying to use our interest for maximum leverage at the bargaining table. They pressed me to seriously consider abandoning the talks, but I was not convinced we should just because we thought they might be using us.

On Saturday morning, Borman also called from Miami to report that he was finally going to tell the unions that Texas Air was a potential buyer. I wasn’t sure he hadn’t done so already but took his comment at face value.

“What about our agreement?” I asked, referring to Borman’s pledge to keep our bid off the union table.

“Look, Frank,” he said. “I have to tell them. You understand that. And when I do tell them, I expect it will put added pressure on them to reach a settlement. In that respect, yes, I suppose you’re being used. But if I don’t achieve full agreement with all the unions on all our proposed concessions, I plan to recommend to our board members that they accept your proposal.”

As the morning dragged on, our Texas Air group met with Eastern’s attorneys to go over the fine points and put the deal on paper. They used the hundred-page agreement we had signed with TWA the prior summer as a kind of boilerplate: under our tight deadline, there was no time to start with a blank page. The TWA contract was a good one, even if it had not stood up to Carl Icahn, and there was no reason not to use it as a foundation.

By Saturday afternoon, word of our proposal had leaked to the media—spread, most likely, by union officials hoping to marshal their members against us and stir up public interest in the plight of Eastern workers—and my phone started ringing off the hook. But I kept my promise to Borman and would not talk to the press.

Eastern, too, successfully avoided these outside inquiries, and we were later able to trace most of the leaks back to the various union camps. Indeed, IAM’s Charlie Bryan, president of the IAM local, was directly responsible for at least one story: he told the New York Times that he would rather see a Texas Air takeover than reopen his IAM contract. “I can work with Frank Lorenzo,” he was quoted as saying, suggesting that he could no longer work with Frank Borman. It was a line he would have to eat a year later.

At this late stage in Borman’s labor negotiations, the pilots and flight attendants were still willing to bend, but Bryan was intractable; his contract still had more than a year to run, and he saw no reason to bail out Borman by reopening it. Eastern had its top negotiators working around the clock on the machinists, but there had so far been no movement. As it happened, the national IAM leaders were in Miami that same weekend for their annual convention, and Borman took advantage of their proximity to press his case directly to the national IAM president, Bill Winpisinger, and vice president, John Peterpaul, but neither man would help turn Bryan around—which they could do under the IAM structure and which Borman claimed he had a promise from Winpisinger to do as a last resort.

Despite the distractions, that Sunday was no different from most. I went out for a run, played in the backyard with the kids, and did some repairs around the house. At two o’clock, I went to my study and waited for a conference call with our board of directors. We were all spread out across the country, and it was impossible to get together in person on such short notice, so we made do by telephone. The board knew in general terms what we were proposing, but this was the first chance we had to brief them in detail. We spent around an hour going over the specifics of our planned acquisition, and the conference concluded with the board’s unanimous and enthusiastic approval.

In Countdown, his autobiography, Frank Borman recalled his thoughts at that time, comparing the situation to the space missions he had flown two decades before. “It’s the same thing,” Borman wrote. “I’ve never gone into a mission without at least three alternatives. If the primary goal cannot be attained, you go to an alternate mission. If that’s out of reach, you abort, which is a failed mission but at least you’re alive. This time fixing the airline is the primary mission, selling it is the alternate mission, and Chapter 11, God forbid, is the abort.”

Borman still had not given up on his primary mission, even at that late hour. By ten o’clock in the evening, only two hours before our midnight deadline, Snedeker called from Atlanta to say that he and the rest of his team were convinced we were being jerked around. They had not heard from their counterparts in Miami for the previous couple of hours. The board’s full attention seemed to be on its labor contracts—an ALPA agreement was reportedly ready for signature, and a pact with the Transport Workers Union of America, which represented the flight attendants, was near completion—and our guys were now convinced that Eastern had involved Texas Air as part of one big ruse.

“They’re using us, Frank,” Charlie Goolsbee insisted over the phone. “I’m surprised you don’t see it.”

This time, after much discussion, I finally agreed, and I instructed Goolsbee to withdraw our offer for lack of good faith. If Borman was so focused on his labor equation that he could not see clearly the alternative that we had offered, then that was his business, but I was not about to let him string us along any longer just so he could accomplish his goal.

Borman called me at home a few moments later, in just about the time it took for word of our withdrawal to travel from Atlanta to Miami. “Frank,” he said, “don’t do this.” He sounded exasperated, almost desperate.

“My guys tell me we’re being jerked around,” I said. “They don’t think you’re operating in good faith.”

“I can certainly understand that,” he said, “but I give you my word. The directors are looking very sincerely at your offer.”

“What about the unions?” I asked.

“We’re still talking to the unions,” he allowed. “I won’t lie to you. Fixing Eastern—that is my first priority. If we cannot fix it, we will sell it. If we can’t sell it, we’ll tank it.”

“All right,” I said, relenting. “I’ll put the offer back on the table.” And we did.

Meanwhile, as the midnight hour approached, I received a call from Eastern director Jack Fallon, chairman of the airline’s executive committee, who wanted me to accept what he was calling a hell-or-high-water clause and extend our deadline by four hours. Basically, he wanted us to commit to acquiring the airline even if it was forced to declare bankruptcy before we could close the deal.

This was a relatively easy concession to make, since this was largely a net-assets deal and I felt we had to concede something. If you truly want to acquire a property, it is difficult to keep your options totally open and still get the lowest price: in order to get the best deal, you often have to give the strongest commitment—this was my belief. In most of our negotiations, I tended to offer big deposits up front to persuade the other party of our strong interest and decrease their financial risk. Even if the deal we offer is comparatively modest, it is always a real deal with a high probability of getting done. Here, I knew, the offer we had placed on the table for Eastern was not especially rich, considering its assets, but the board seemed willing to go ahead with it, provided I could offer reassurance that we were fully determined to proceed even if Eastern’s operations took a turn for the worse. The specter of Chapter 11 did not trouble me. I had already been through it with Continental and lived to tell the tale. I was convinced that the asset values of Eastern were sound and that those assets would not evaporate in bankruptcy. Besides, I thought bankruptcy could be avoided, at least until closing.

After briefly discussing the issue with our legal team, I got back to Fallon and told him, “Have your people add it to the contract. We’ll sign it, and we’ll agree to four more hours.”

This was easier said than done. A hell-or-high-water agreement was apparently so rare that none of the high-priced lawyers on hand were sure how to word it. Finally, someone came up with a draft that was acceptable to both sides.

Back in Miami, Borman and company put their four-hour stay to full use. A number of Eastern employees had begun to mill about the lobby of Building 16, the company’s headquarters and the site of the after-hours board meeting, awaiting the verdict. Inside, the directors were playing their final hand. Borman left the room to let the board freely consider Bryan’s latest proposal, and he later wrote that he used the time to stroll to the memorial fountain outside the building, honoring the company’s founding spirit, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. He read the plaque beside the fountain. “I kept looking at it,” he wrote. “I just couldn’t stop looking at it. Standing there alone in the moonlight, never had I felt so close to this tortured, troubled airline. Never had I wanted so badly to save it.”

But it was out of his hands. Charlie Bryan stubbornly rejected every counteroffer and compromise the directors presented, and in the end, there was nothing to do but put the sale to a vote. Just after three o’clock in the morning, the directors voted 15–4 in favor of selling Eastern Airlines to Texas Air—the nay votes were cast by Bryan and the other three union directors.

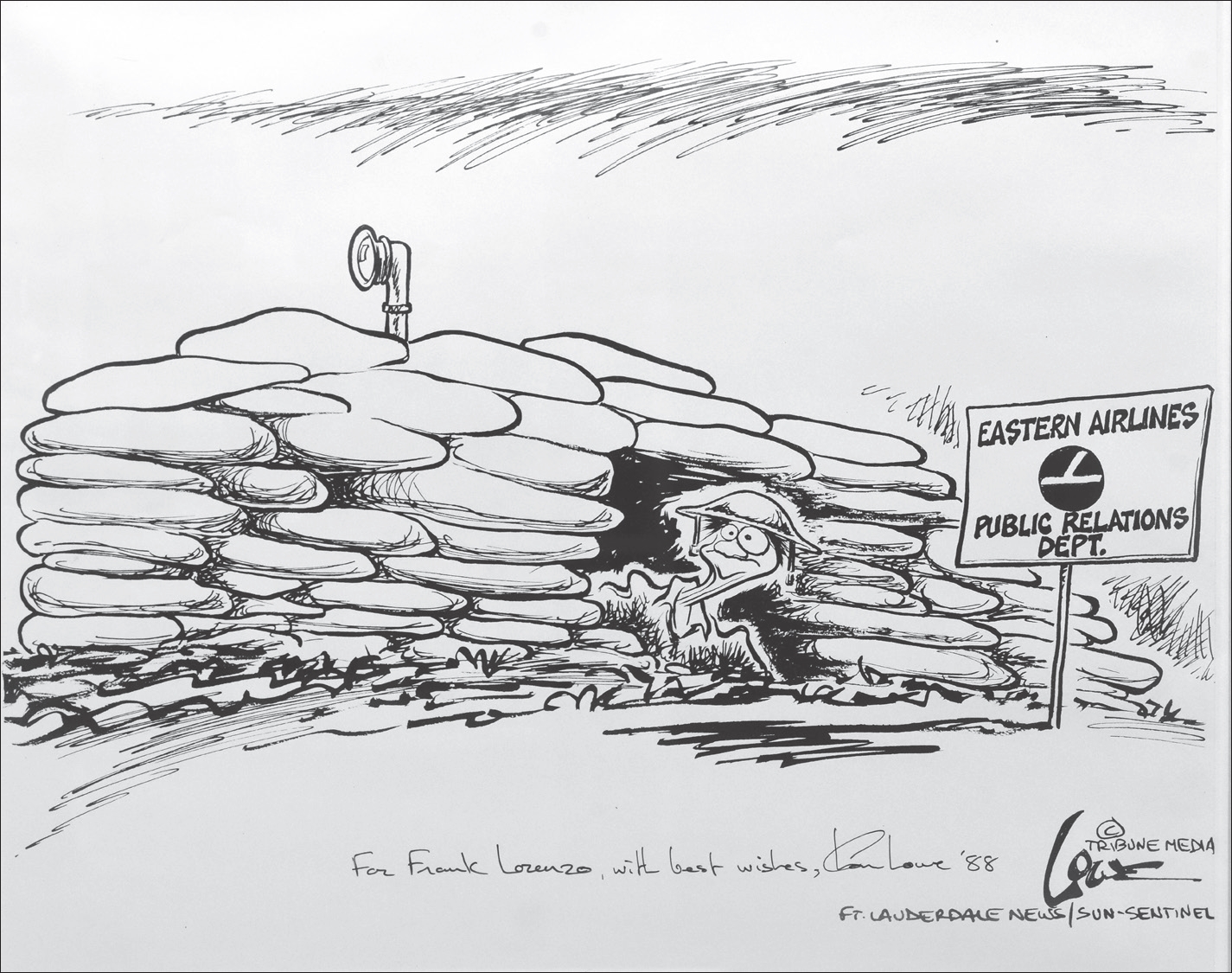

Cartoon poking fun at takeover of Eastern (1986).

I was on a plane to Miami before breakfast, still reeling in the wake of the weekend’s events. This was the critical mass we had been seeking for so long. Eastern would provide us with a strategically critical computer reservations system, a strong, sophisticated management team, and unmatched facilities throughout the country. In fact, those facilities showed their value quickly, since with Eastern’s domination of Newark International Airport’s Terminal B and Continental’s domination of Terminal C, we were able to keep the other large carriers from creating a competitive hub in that city. We knew American wanted to get into Newark in a major way. But more on that later.

Texas Air would also soon be flying more planes than anyone else in the world with the exception of Russia’s state-owned Aeroflot. In 1985 figures, the combined Texas Air fleets would fly nearly fifty-one billion revenue passenger miles, nearly tripling our current traffic. We would be responsible for 57,000 employees. Born as a somewhat suspect little holding company, Texas Air had been transformed into one of the most formidable, forward-thinking investors in the domestic airline industry—or so we hoped.

It did not take Wall Street long to declare the Eastern purchase a great deal for us. For $607 million, half of which would come out of Eastern’s own bank account, we stood to acquire a company with more than $2 billion in net assets. Eastern stock, which had traded as low as $4.75 in prior months, climbed to the $9 range within a week of our announcement. For years, the uncertainty over Eastern’s union contracts had acted as a mortgage on the company’s assets. With this deal, investors hoped that Texas Air would be able to liberate the operation from its skyrocketing labor costs, and Texas Air stock soared on the news. Normally, the market drives the shares of an acquiring company in the opposite direction, anticipating the debt or equity dilution resulting from the takeover, but by the end of that first week, our shares climbed from $17 to $28.50.

In the short time since we were asked to put together an offer for Eastern Airlines, our focus had been on acquiring the prize. None of us had time to consider what we would actually do with the airline once we bought it. For the time being, at least, we would not do anything. We could not. The deal was still subject to shareholder and government approval, and it would be several months before the Department of Transportation would make its ruling. The only potential complication we could see was the possible antitrust implications of operating the New York Air and Eastern shuttle markets alongside each other, but we thought we could work that through with the regulators.

As we did in most of our other deals over the years, we took things one step at a time. At that point, we intended to run Eastern separately from Continental and New York Air, although we would certainly look to consolidate operations in some areas down the road. Borman, as part of our agreement, would remain as chairman and chief executive until the deal was closed, although we would look to install some of our own people in top management positions to help with the transition and ensure that our interests were being served during the interim period.

No other deal of ours had ever generated so much attention: indeed, it was difficult to think of any other airline deal that got so much interest. Maybe it was because in just two days we had grabbed one of the country’s largest airlines for a little under one-third of its asset-rich net worth. Maybe it was because everyone sensed that there was a shootout destined to take place between us and the combative unions that had held Eastern hostage for so long. Maybe it was because people were curious to see if we could succeed where others couldn’t.

Our original intention was to simply fly Eastern as a separate carrier, apart from Continental, for the foreseeable future. Four or five years down the road, we envisioned some sort of combined Continental– Eastern fleet, but it made no sense to consider any sort of merger until we had gotten Eastern’s losses under control and brought Eastern’s cost structure closer to Continental’s. This process could not begin until we received final DOT approval. In the meantime, Borman and the Eastern president, Joe Leonard, were still in charge, although they dealt with us in a transparent manner by opening their books as well as their boardroom doors. Predictably, Eastern’s management was hit by a wave of exits, and Borman and Leonard were very good about putting some of our people into these open spots.

They even consulted us on the significant operational decisions they were pondering. Around a month after we had announced our deal, Leonard told us that Eastern was planning to pull out of its Kansas City hub. Borman had created the hub in the early 1980s, thinking that Eastern needed a western presence, but it never made any money, and Leonard figured it was high time to cut Eastern’s losses there.

We didn’t see it that way, however, at least not initially. We thought we could develop a number of smaller regional hubs and manage these alongside two or three giant centers. Eastern had a number of these regional hubs throughout its system—in Charlotte, Philadelphia, and New York, for example—in addition to its dominant operations in Atlanta and Miami. Our team was not prepared to close the door on Kansas City before we had a chance to make our own assessment. Two years later, when we finally decided on our own to close Eastern’s Kansas City operations, the unions wailed that we were stripping the company, not realizing that we had given the four thousand affected jobs an effective two-year stay of execution back in 1986.

Eastern started 1987 stronger than anticipated financially, but despite that, there were other markers that showed that the airline would be on a slow slide to insolvency without changes in its costs. The labor concessions that Borman had won in his last-ditch bargaining with the pilots and flight attendants in 1986 were due to expire in the months ahead. The machinists’ contract was due to expire even sooner, and those negotiations would set the tone for the airline’s immediate future.

Charlie Bryan had tried to pull the rug out from under us from the very beginning. Immediately after our February 1986 acquisition announcement, he began beating the drums for another buyer to come in and force us out of the company. He even pushed in vain for an employee buyout.

I had no dealings with Bryan myself during my Eastern days, which Bryan probably took as an affront. We believed Borman had made a big mistake in getting directly involved in labor negotiations. A local union leader lives his contract day in and day out. He knows every detail, every nuance. The only way management can negotiate a labor deal responsibly and effectively is to match labor leaders with executives who are also able to devote their full attention to the matter. Eastern had such a person as its chief negotiator. In addition, Phil Bakes was Eastern’s president and CEO, and I certainly did not want to undercut him. Phil was full-time in Miami at Eastern and was highly regarded by us back in Houston. He relinquished the same posts he had held at Continental when taking over as CEO of Eastern. I remained in Houston, focused on Continental, and was consulted only on major issues, not on a day-to-day basis.

It was not that I was totally opposed to direct union relations or meetings when it seemed appropriate. For example, I did have personal dealings with the head of the national IAM union, Bill Winpisinger, who flew to New York from Washington once to have lunch with me as we attempted to break the Eastern–IAM logjam. On another occasion, I met with the head of the Eastern pilots’ union at New York’s University Club for a drink.

For years, Bryan played Borman like a pipe organ. He never put his real demands on the table until the deadline drew close because he knew he could draw Borman into the negotiation, where his involvement could cost Eastern dearly. During one negotiation, Borman extracted certain economic concessions from Bryan in exchange for something much more costly in the long term: he gave IAM the right to represent the mechanics’ first-level supervisors. Making workers and supervisors members of the same union was in reality a recipe for a breakdown in workplace authority. We were told that Bryan, after this concession was agreed to, went out to the main machinists’ area at Miami International Airport, stood up on a ladder, and proudly told the workers that the union now represented all their bosses. The rank and file erupted in cheers, while the supervisors stood silent, knowing they had effectively been stripped of their authority.

Unsurprisingly, I had been made the flash point for the coming battle with the Eastern unions, and it would not be long before my reputation and integrity were under full-throttle attack by the unions’ heaviest artillery. During the discovery phase of one of the many lawsuits with the unions, we uncovered a strategy memo prepared for the unions’ public relations people by an outside PR consultancy that was headed, “Make Frank Lorenzo the issue—avoid discussing airline deregulation.” The Eastern deal may have been a steal, but if these early turns were any indication, it would be far more difficult than I bargained for.

Negotiations had to start somewhere, so in October 1987, we asked the machinists to accept nearly $250 million in concessions and to allow management to hire part-time workers under certain conditions. Anything much less would place the airline in real jeopardy, we thought, and anything more would likely incur the wrath of the IAM. As it was, I feared we were pushing the envelope a bit with this opening offer, although it was similar to what Eastern had been seeking before our purchase.

If we succeeded in convincing the machinists that the only way they could preserve their job base was to relent on their wage and benefit demands and to splinter the IAM’s skilled mechanics from its unskilled members, allowing us to establish two different wage scales, then we had a shot at reinventing Eastern as a vital, financially viable carrier for the long term. If we failed, and caved in to the IAM’s absurd and inflexible demands, we would be pushed right out of business, because this would lead to our getting few if any concessions in bargaining with the other unions, who were anxiously waiting to see if a concession precedent was set. However, those other unions had nothing to fear, because Bryan countered by demanding 10 percent pay increases over each of the next two years, and if we had held out any hope that the machinists would finally see the light, it was dashed by his response. We were not even on the same page.

Eastern’s management looked on Bryan’s proposal as a bad joke, something he could float to his members and back away from at a later date when the need arose. It was not based on any real economic assumptions. It was based on wishful thinking, his own politics, and the union’s apparent desire to force our hand. I had long thought that Bryan was on a kind of power trip, and the beginning of these formal talks confirmed it. He had just been elected to an unprecedented fourth term as head of Eastern’s IAM district earlier that month by an overwhelming margin, and he seemed eager to flex his new muscles. Our offer was difficult for him to accept, we knew, but it reflected an honest need to sharply reduce Eastern’s cost structure, bearing in mind the fare competition with which Eastern was surrounded.

We did not think we could accomplish this on the first pass, but we had at least hoped that Bryan would come back with something that might have acknowledged Eastern’s critical need. While he could well have been realistic, considering the position of the company, he instead came back with these absurd and totally out-of-touch numbers. This left us too far apart for any serious negotiations and forced us to consider a general downsizing of the company—a de-risking, so to speak—and the attendant sale of certain assets.

It also forced us to call on the National Mediation Board to break the standoff. Here again, our hands were tied by the ancient mediation rules established by the Railway Labor Act. Recall that regulations required a thirty-day cooling-off period prior to any work stoppage or unilateral changes to a contract. The NMB could declare an impasse at any time, at the request of labor or management, which would set the thirty-day clock to ticking. After that, labor was free to strike and management was free to impose new terms, but absent a “release” by the NMB, both sides were bound by the terms in force on the last day of the old contract.

Traditionally, airline management was only too happy to have the terms of labor contracts frozen at their expired levels. The unions, seeking a pay increase, would push mediators to quickly recognize an impasse; the airlines, looking to hold down costs, would sit back and let the process unravel at its own, usually leisurely, pace.

But this was no longer the situation, at least not at Eastern. Borman’s labor contracts reflected the shift in industry practice and called for certain snapback provisions prior to the close of term. The 20 percent concessions granted by the pilots in early 1986, for example, would be given back at the end of the contract, and the pilots would be rewarded with a pay hike substantially above their pre-concession levels. Under this scenario, the interests of labor and management in mediation were completely reversed, and it was up to us to ease the stalemate. The unions were not about to give regulators any cause to imperil their hard-won gains.

Both sides braced for a strike. A walkout would be a miserable turn of events, but it would not be a killing one, we thought. We had flown through work stoppages before, and we were confident that Eastern could survive a strike by its machinists, provided—and this was essential—that we could get the pilots to cross IAM picket lines. We formulated a strike insurance plan, drawing on some of the resources of Continental, and looked to the NMB to start the thirty-day countdown. We had to get this negotiation, which was not going anywhere, behind us.

And so, beginning in January 1988, we waited. And waited. And waited. Every day, we all went into the office thinking we would have a ruling from the NMB, and every day we went home wondering what we had to do to convince the board that we were too far apart to make any headway in negotiation without a deadline. Months went by as Eastern’s losses mounted. We lobbied extensively in Washington, hoping to be released from our old contract, but the machinists countered our every argument. Bryan contended that we were out to break the unions and claimed we were pushing for a strike. In reality, we were pushing to get this negotiation behind us and didn’t think that Bryan and the IAM would be realistic until they were forced to be. What we were truly seeking was a resolution to this conflict.

With the labor situation at a slow boil, Phil Bakes and his team turned their attention to day-to-day concerns. They pared back some of the airline’s operations and reduced service in markets where we no longer liked the profit potential. We also trimmed some fat in our management ranks and cut our overall workforce by around 10 percent. We looked to beef up our service record, and even in the middle of these labor wars managed to improve our on-time performance rating, as measured by the DOT, to an industry high.

One of the first major steps we took to position Eastern alongside our other holdings was to transfer its computer reservations system to the corporate level, where it could independently service each of our sister airlines—and other outside airlines—away from the din of the labor fights at Eastern. Under this shared arrangement, we projected that System One’s reach would be significantly enhanced, as indeed it was. Eastern’s management had long sought such an outcome.

Eastern PR department cartoon (1988).

While it was a sound, even logical, move and certainly within our rights, since we owned the company, it generated a swirl of protest. Months later, the unions would point to the transaction as proof that Eastern and Continental were being operated as a single carrier and that Eastern’s assets were being stripped for the benefit of Texas Air. Texas Air paid an equitable market price for the system, a number reached through the independent assessment of investment bankers at Merrill Lynch, and we made sure that Eastern’s leaseback expense would never exceed the operating costs it had previously been paying to maintain the service. With more than two thousand employees, System One bore enormous labor costs, and Eastern simply traded its wage and benefit outlay for a comparable monthly service charge. In exchange, the airline received an infusion of cash and increased penetration into Continental’s base. Continental, too, greatly benefited from the alliance with Eastern and System One’s increasing market share. Just as importantly, System One services now could be sold to other airlines, resulting in a greatly reduced perception that it was run by the marketing departments of our airlines.

It was, I thought, a good deal all around, but we took some heat for it, as we would for most of our efforts at consolidation, which were second-guessed by the unions. We were challenged on our merger of the Eastern and Continental sales and marketing forces, our creation of a central fuel purchasing unit, the alliance of Eastern’s and Continental’s frequent-flier programs, and the sale of excess aircraft from Eastern to Continental. The deals were contested in the courts and in the press, even though such arrangements were not unusual—even among unaffiliated carriers—and even though they reduced overhead and increased productivity. In our case, since the carriers were affiliated and under full common ownership, the benefits of these moves were even more obvious.

Eventually, the pilots got in on the act. Beginning in late 1987, ALPA launched what it called the Max Safety campaign. For the following two years, it registered an endless stream of fabricated complaints directly with the FAA. Pilots were instructed to fill out PRIA (Pilot Records Improvement Act) forms for all sorts of perceived or imagined equipment violations. At the end of each month, the FAA was inundated with thousands of write-ups that they were obliged to check out. ALPA then issued press releases recording the number of safety complaints filed against Eastern by its own pilots.

Although there was a long rivalry between Eastern’s ALPA and IAM leadership, here it seemed that Jack Bavis, the pilots’ union head, and Charlie Bryan had found a common enemy in Texas Air. Max Safety was a blatant attempt to smear airline management and damage Eastern’s reputation with the flying public. It also included a good old-fashioned slowdown of operations. Pilots were instructed to exercise extreme caution on the ground as well as in the air, and our planes were taxiing the runways of some of our busiest airports at only one or two miles an hour. Our on-time performance levels sagged, and public confidence in the airline sank to new lows every day. The crisis was rapidly coming to a head.

Eastern was clearly a failing carrier, obvious for all to see, but closing the deal for Eastern wasn’t smooth. Although the Reagan administration would greenlight mergers in October and December 1986 between Northwest and Republic Airlines and between TWA and Ozark Airlines, each of which had competing hubs in the same cities, Reagan’s Department of Justice and Department of Transportation balked at our deal. DOJ and DOT viewed the bundling of New York Air and the Eastern shuttle under one “roof,” so to speak, as anticompetitive. This complication would cause us great angst. We eventually decided to sell New York Air’s slots at LaGuardia and Washington National Airports to Pan Am, which started its own shuttle service in competition with Eastern’s. Stripped of its highest-value, highest-profile asset, New York Air would eventually be folded into Continental. It was a painful decision, given the entrepreneurial spirit of Texas Air and our memories of starting New York Air and competing with Eastern. We were backed into a corner from which we had to decide whether to sell the crown jewel, the Eastern shuttle, or much of New York Air (the full story of this agonizing decision will be told in the next chapter).

Our inability to reach an agreement with the unions eventually led to a strike. Initially we tried to fly through it, but ultimately operations shut down. Despite our desire to keep the airline flying and keep the jobs that went with it, we reached the point where the next move was to consider selling Eastern. The situation could possibly threaten the entire Texas Air group.

By the spring of 1989, Eastern was bleeding lots of cash. We could not get operating costs even close to where they clearly needed to be, and the unions remained unmoved, refusing to renegotiate their contracts. The strike continued as well. We finally put Eastern into bankruptcy on March 9. Even so, we received significant interest from potential Eastern buyers, most of whom had been approached by the unions. These buyers basically felt that they could extract major union cost relief, which we and Colonel Borman could not obtain, and thus benefit from ending the strike and, with any luck, gaining labor peace.

In addition, it was believed by potential buyers that we were under financial pressure to sell. The deal that got the furthest was a potential sale to a group led by Peter Ueberroth, the Major League Baseball commissioner, whose term had just ended and who was well known for his handling of the 1984 Olympics in California. Carl Pohlad, the Texas Air director and owner of the Minnesota Twins, had been with Ueberroth at a baseball owners’ meeting in Fort Lauderdale in early March 1989 when Ueberroth approached him with his interest. Carl contacted me and said that Ueberroth’s group would be a logical buyer and that we should try to negotiate a deal and sell Eastern to him. Ueberroth had already been having discussions with the unions, with our approval, and the unions were, unsurprisingly, very interested in seeing him buy the airline.

After much negotiation, we came to an agreement with Peter and his group and announced it on Thursday, April 6, 1989. They were to buy the airline for $464 million, subject to approval of concessions by the airline’s unions. Peter claimed he had already negotiated a deal with the unions, so it was assumed that this condition would be met. In addition, the deal was subject to creditor and bankruptcy court approval—which would be easy with union accords, although there was no assurance on financing.

We were very skeptical of what the unions would really agree to and feared that Ueberroth, and probably Pohlad, were somewhat naive about what in reality could be put in writing with the unions. Because of our doubts that the deal could be consummated, and because of the disruption that a sale causes, we put a seven-day fuse on it, requiring union approval by midnight the following Tuesday, April 11. Peter thought that would allow sufficient time for his approvals. These were heady days for Ueberroth, who was set to become the operating head of the airline, and the announcements were accompanied by mammoth amounts of publicity, which he did not appear to discourage.

But the Eastern union approval never happened as it was supposed to, and the deal fell apart on the following Wednesday. The unions, cagily, announced that they would be agreeable to Ueberroth’s cost cuts, but only on the condition that we allow the immediate appointment of a trustee to take over our ownership position. This requirement was obviously absurd, because it would have allowed the airline to be taken from us without any assurance that Ueberroth could raise the money to buy it. The union’s lawyers undoubtedly would have made it clear to their clients that we could not possibly give up permanent control of the airline before we received payment for it. However, Ueberroth was publicly disappointed, and in walking away from the deal he told the bankruptcy judge that he would not be willing to come back and revisit the purchase.

Carl Icahn, who wanted to merge Eastern with TWA, and my old friend Jay Pritzker and the Hyatt group, always interested in airline deals, were also circling around and publicly declaring their interest. Icahn was the most aggressive in pursuit, although I knew that his style was to push hard on a deal, see how low he could get the price, and then walk away.

Nevertheless, I agreed to have dinner with Carl one evening, although I was confident it would go nowhere. I felt it would show that we were casting a wide net in attempting to settle Eastern’s ownership issue, which we in fact were. Carl and I met at a small Italian restaurant, a favorite of his, on West 56th Street in Manhattan—Il Tinello. Knowing that the singer Karen Akers, one of Sharon’s and my old friends (she was then the wife of a Columbia fraternity brother, Jim Akers), was performing that evening at a small cabaret on West 27th Street at 9:15 p.m., I arrived for dinner with Carl at 7:15 p.m. and told him that I would be leaving at 9:00 p.m. at the latest because I had a commitment downtown. He then gave me twenty questions on what I was going to be doing, and when I told him that I was headed for some fun with an old friend who was singing in a cabaret, he asked if he could join me. The sight of two formally dressed businessmen sitting in the back of the tiny, informal space (Carl is quite tall), having martinis, must have been a sight to behold. As it turned out, the evening was enjoyable and gave me a view of Carl’s “other side,” but it certainly did not advance the prospects of an Eastern sale.

Unable to move forward, we continued with our efforts to rebuild Eastern as a small airline focused on the Atlanta hub. To accomplish this, Eastern began hiring pilots, although many of the company’s pilots were coming back. In the second week of August alone, 250 pilots returned, and we temporarily stopped hiring.

In addition, we looked at assets to sell in order to raise cash, the most obvious being the New York–Boston–Washington shuttle (I cover this sale in the next chapter). We also looked at selling other assets to prepare for the reorganization plan, which would allow us to pay our creditors and get Eastern discharged from bankruptcy. A package of assets valued at $1.5–$1.8 billion, which we knew could be readily sold or already had been sold, was planned for the reorganization. The biggest additional piece was the sale of Eastern’s South American routes, largely encompassing Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

The sale of the South American route was put in place with a phone call I made to the farsighted Bob Crandall, CEO of American Airlines, whom I knew well. Our planning group had long considered the near-term value of these routes to us, since we knew they would likely be a cash drain for the foreseeable future. Crandall and I agreed on a juicy $500 million number on the phone, higher than what our planners thought we could get. But the sale took a long time to complete, given the union fights that ensued and the myriad details involving aircraft, personnel, liabilities, and so forth that needed to be sorted out. We also continued to have doubts as to whether we needed to sell the routes as part of our reorganization plan, since we were aware that we were selling a network of routes with future promise. But the route sale did get completed and approved by the bankruptcy court in early 1990.

At that stage, we were putting the finishing touches on our reorganization plan, although the unions were continually scrambling behind the scenes to sabotage it. They had a major advantage in that they were members of the creditors’ negotiating team, even though the pilots and flight attendants had ended their strike and many members had returned to work in the fall of 1989.

In February 1990, we reached agreement with our unsecured creditors on a plan to discharge Eastern from bankruptcy that would have returned fifty cents on the dollar for unsecured creditor claims. But only a month later, we had to go back to the creditors and admit that the plan would not work, since Eastern’s results had worsened. In the negotiations that ensued, in late March, we were unable to come to an agreement, because the unsecured creditors, spurred on by the unions, were holding out for a blanket guarantee from Eastern’s parent company, which we had always held apart from Eastern. Texas Air was willing to make a major contribution in cash and notes, but it was unwilling to be responsible for Eastern’s liabilities in total. So on April 10, 1990, the creditors asked the court to appoint a trustee to take over the ownership of Eastern, replacing Texas Air, a request that was granted on April 19.

The court’s decision to remove Texas Air and appoint a trustee tolled the death knell for Eastern. It meant that Texas Air—with its airline, its financial resources, and its deep management strength—was to be replaced by an individual. A very difficult decision to reconcile with reality. But it shows the continued influence of the unions on the creditor committee.

As it happened, in place of our management, the trustee appointed by the court was Martin Shugrue, whom we knew well because he had briefly served as president of Continental in the 1980s and had been with Pan Am. The unions dropped their picket lines under Shugrue, and the airline was brought back at a reduced size. Marty also embarked on an expensive advertising campaign in the summer of 1990, in part featuring himself. It seemed, according to our folks, that he never really understood Eastern’s weaknesses. Sadly, the carrier, also struck by the rapid increase in fuel prices after the invasion of Kuwait, ran out of cash later in 1990. In January 1991, Eastern, well known as the Wings of Man, stopped flying and was liquidated.

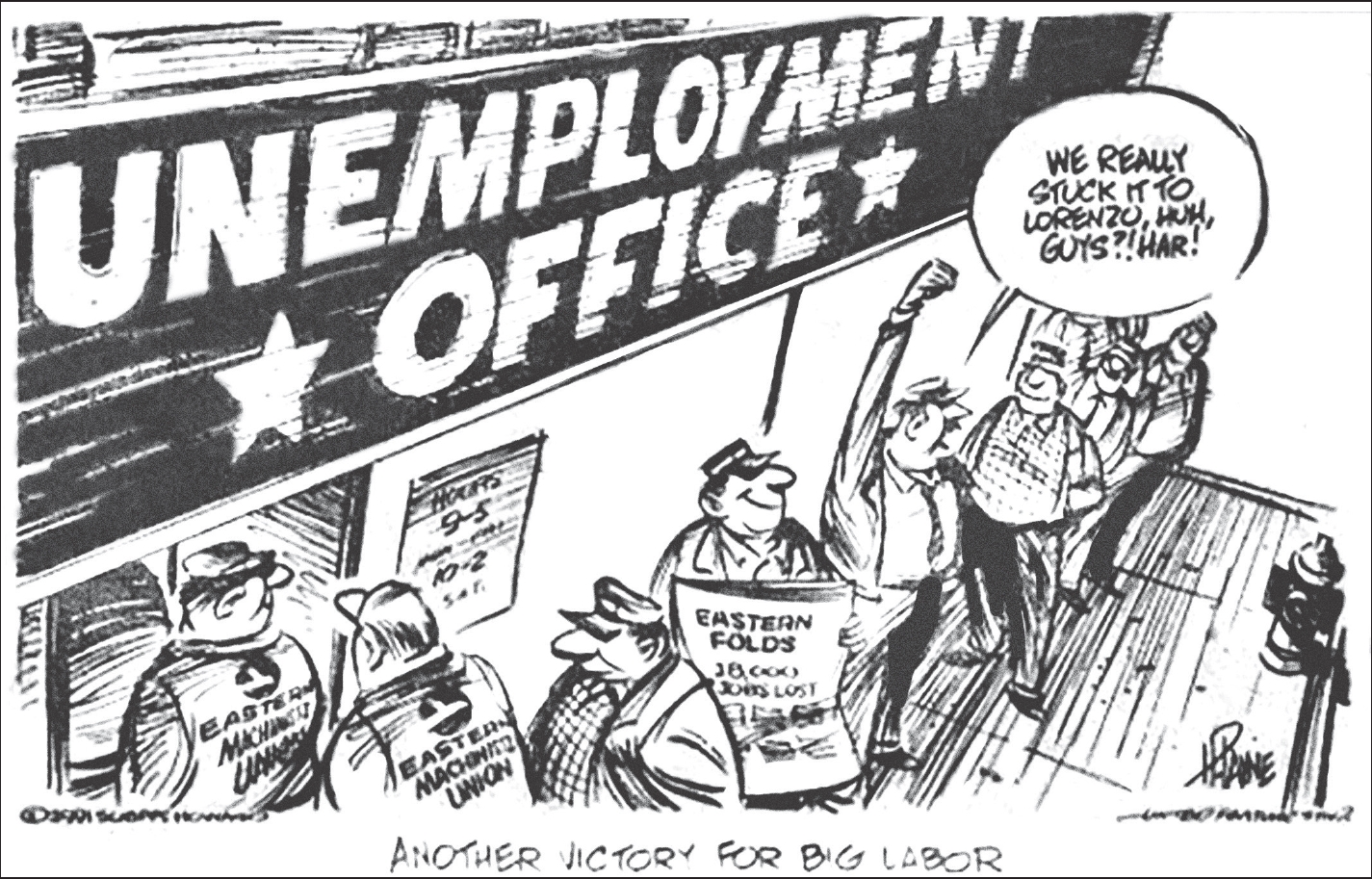

“Unions tried to tell Eastern employees that they won the Lorenzo war.”

It is easy to blame ourselves and look at the Eastern purchase as a bad deal that shouldn’t have been done. Certainly, it was a bad deal in terms of our financial loss and our lost time and energy. However, it is also realistic to acknowledge that things would have been quite different for Continental without the purchase.

For starters, Frank Borman said that Eastern would (or had to) be placed in bankruptcy if the unions didn’t agree to new contracts and if Texas Air didn’t complete the purchase. While it’s of course fruitless to speculate about who would have purchased Eastern’s assets, we had already seen that there was interest on the part of other carriers in establishing a Newark hub. If we didn’t acquire Eastern, Continental probably wouldn’t have been able to build its massive and very profitable hub at that airport. Instead, Newark would have been a two-carrier hub, which usually entails more competition and less attractive economics. In addition, Texas Air still owned Eastern’s System One, which served as the backbone of Continental’s computer reservations system for years.

But still, all things considered, Eastern was a deal that we should have passed on.