The Guns

The early guns had beautiful names like cannon-royal, cannon-serpentine, demi-culverin and falconet, but they had a bewildering variety of shot and charge; and since these weapons, together with basilisks, sakers and murdering-pieces might all be mounted on the same deck, it led to sad confusion in time of battle.

By the eighteenth century there were many fewer kinds, and they were called by the weight of the shot they fired: a first-rate, for example, carried 30 32-pounders on her lower deck, 28 24-pounders on her middle deck, 30 18-pounders on her upper deck, 10 12-pounders on her quarterdeck and 2 on her forecastle, thus firing a broadside of 1,158 lb. Everything was plain and straightforward: each deck had guns, shot, cartridges and wads of the same size; the guns could be supplied from the magazines as fast as the powder-boys could run; and all that remained was to fire them as quickly and accurately as possible.

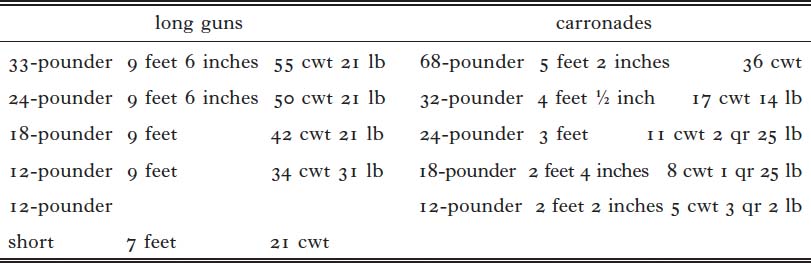

This was something of a task, however, for the gun was a massive brute, mounted on a wheeled carriage, and it had to be fired from a deck that might be in violent motion. An 18-pounder, a medium-sized gun, had a barrel nine feet long; it weighed 2,388 lb, and it needed a crew of ten to handle it, for not only did it have to be run in and out, but it had to be kept under rigid control – two tons of metal careering about the deck in a rough sea could kill people and smash through the ship’s side.

The crew included the captain of the gun, the second captain, a sponger, a fireman, some boarders and sail-trimmers, and a powder-boy, with perhaps a couple of Marines to help in the heaving. They were used to working together, and in crack ships they handled their monsters with wonderful skill: it was English gunnery rather than English ships that won the great naval battles. Each man had his own particular job, so in the roar of battle there was no need for orders. When a gun was to be fired the port was opened, the tight lashings that held the gun to the side were cast loose, and the tompion (the bung that kept the muzzle water-tight) taken out. The men hooked on the tackles – one to each side to heave the gun up to the port and the train-tackle behind to run it inboard for loading – and they seized the breeching to the knob at the end of the gun. This breeching was a stout rope made fast to ring-bolts in the ship’s side, and it was long enough to let the gun recoil.

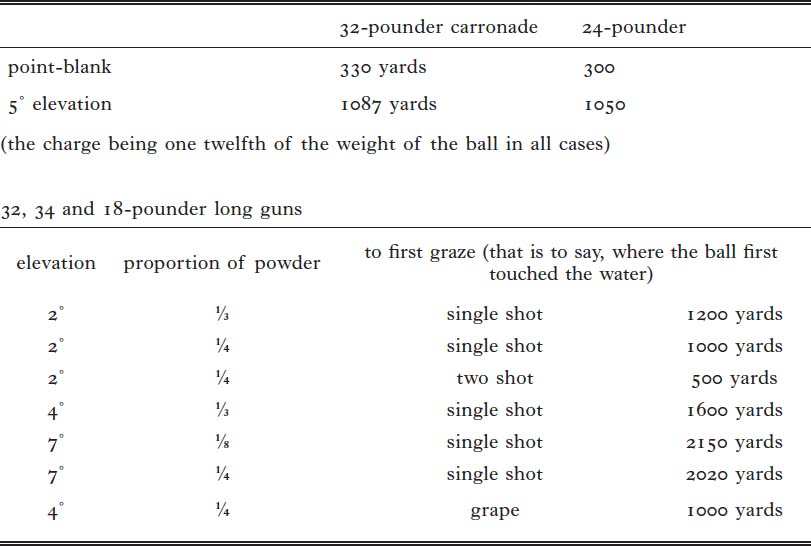

Now, with the gun run in and held by the breeching and the train-tackle, the sponger took the cartridge, a flannel bag with six pounds of powder in it, from the powder-boy, rammed it down the muzzle until the captain felt it in the breech with the priming-iron that he thrust through the touch-hole and cried ‘Home!’ Then the 18-pound shot went down, followed by a wad, both rammed hard: the men clapped on to the side-tackles and ran the loaded gun up, its muzzle as far out as it would go. The captain stabbed the cartridge with his iron, filled the hole and the pan above it with powder from his horn, and the gun was ready to fire, either by a spark from a flint-lock or by a slow-match, a kind of glowing wick. It was aimed right or left by the crew heaving the carriage with their crowbars and handspikes; and the captain, who aimed the gun, could raise or lower it with a wedge under the breech. But although they could send a ball for well over a mile, these guns were not accurate at a distance and they were usually fired at point-blank range – about four hundred yards – or less: indeed, commanders like Nelson preferred to lay their ships yardarm to yardarm, where there was no possibility of missing, and where their double- or treble-shotted guns could fire right through both sides of the enemy.

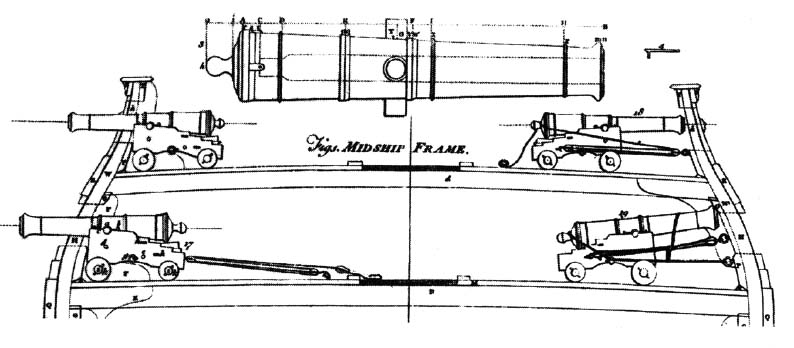

Guns on a man-of-war. The top gun on the right is run in so that it can be loaded; both of those on the left are in the firing position; and the lower one shows the train-tackle. The fourth gun is housed, that is to say made fast so that it cannot move in a heavy sea.

At the word ‘Fire!’ the captain stubbed the red end of the match into the powder on the pan, the flash ran through the touch-hole to the cartridge and the whole thing went off with an almighty bang. The shot flew out at 1,200 feet a second, the entire gun leapt backwards with terrible force until it was brought up by the breeching, and the air was filled with dense, acrid smoke. The moment it was inboard the captain stopped the vent, the men at the train-tackle held the gun tight, the sponger thrust his wet mop down to clean the barrel and put out any smouldering sparks, another cartridge, shot and wad were rammed home, and the gun was run up again, hard against the port.

It was heavy, dangerous work, above all in action, with the whole broadside firing: the low space ’tween decks would be filled with smoke; little could be seen, little heard, and the slightest false move meant the loss of a leg or an arm from the recoiling gun, to say nothing of the risks of explosion or the enemy’s fire. Yet a well-trained crew could carry out the whole operation in one minute forty seconds – three broadsides in just five minutes.

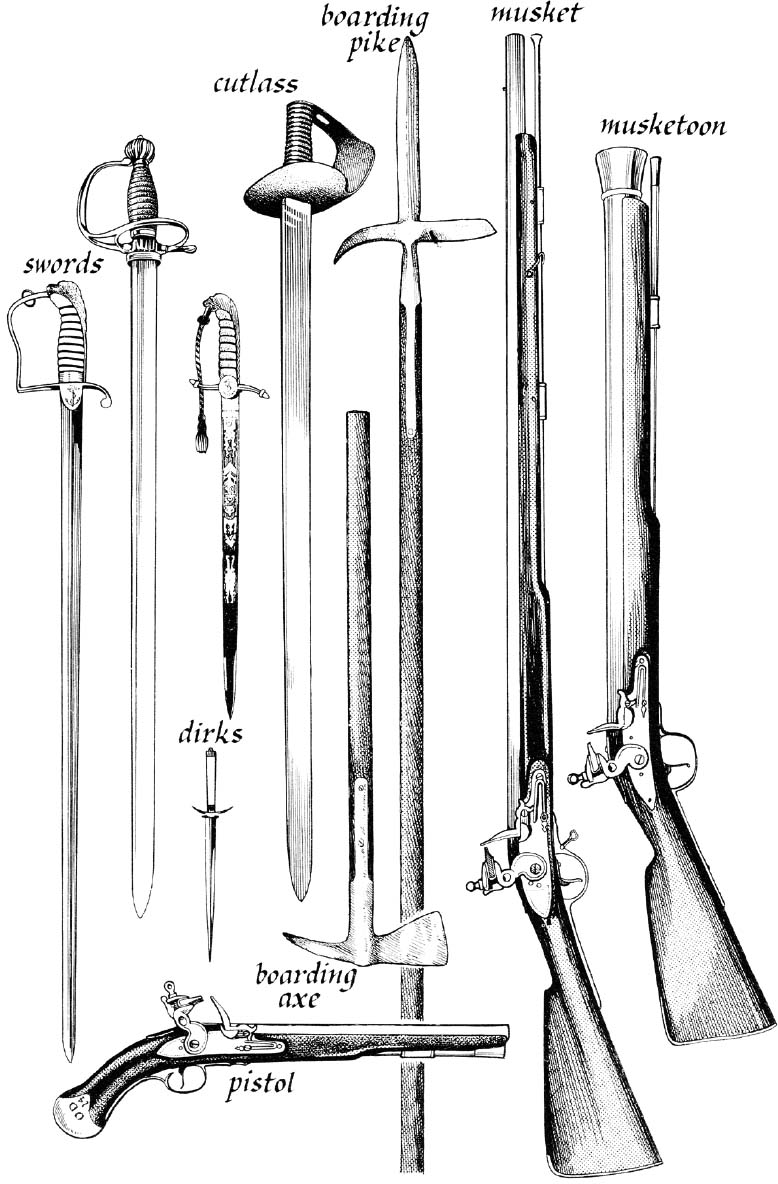

They could do this even in the heat of battle, although some members of the gun-crew had other duties as well. The boarders had their cutlasses ready in their belts and they would leave the gun to batter the enemy by hand at the cry of ‘Boarders away!’ The sail-trimmers would go to their stations when called upon; the fireman had to be ready with his bucket to dash out the first beginnings of a flame aboard; and the second captain to see that the corresponding gun on the other side of the deck was prepared, for few ships had enough people to man two sides at once, and the same crew fought both port and starboard guns.

What they fired was mostly single round shot – the ordinary cannon-ball – and a 32-pounder could smash through two feet of solid oak at half a mile; but at close range they also used grape (a great many small balls in a canvas bag that burst when it was fired, scattering the balls over the enemy’s deck and discouraging his crew), canister (much the same), and bar or chain shot to cut up his rigging.

Right through the eighteenth century the Navy used these guns with little change: the 42-pounders were laid aside as being too heavy for even a first-rate (the Britannia, or Old Ironsides as she was called from her massive timbers, was the last to keep them), and the 32, 24, 18, 12, 9, 6, 4 and 3-pounders were the usual armament. Then in 1779 the carronade or smasher was invented: this was a much lighter, shorter gun mounted on slides and designed for close-range fighting. It threw an enormous ball for its weight.

The first ship to be entirely armed with them, by way of experiment, was the Rainbow, an old 44. Before this she had carried 20 ordinary 18-pounder long guns on her lower deck, 22 12-pounders on her main deck, and two 6-pounders on her forecastle – a broad-side weight of metal of 318 lb, needing about 100 lb of powder to fire it. Now she had 20 68-pounder carronades on her lower-deck, 22 42-pounders on her main-deck, four 32-pounders on her quarterdeck and two on her forecastle – a broadside of 1,238 lb, still needing only about 100 lb of powder, since the charge of the carronade was one twelfth of the weight of its ball, as opposed to the long gun’s one third.

The Rainbow put to sea, and after six months she found an enemy of the right size – the powerful French 40-gun frigate Hébé. The action began in fine style, but to the Rainbow’s intense irritation it stopped almost at once. The French captain, seeing these horrible great 32-pound balls coming from the Englishman’s forecastle, rightly assumed that there was even worse in store, and struck his colours.

By now it was 1782; the war was almost over and it was too late to try out the carronade in earnest. But by 1793, when the next war began, the Navy was well stocked with them, and they did splendid service in the years to come. They did not replace the long guns, however, most of the carronades being 18or 12-pounders on the forecastle, quarterdeck and poop. Curiously enough, they were never counted in with the rest of the ship’s armament, a 24-gun ship like the Hyaena, which mounted ten 12-pounder carronades as well as her long guns, remaining a 24-gun ship for official purposes. Firing point-blank meant firing with the gun level: to make the ball go farther one would raise the muzzle, giving it so many degrees of elevation. But point-blank was the most accurate way of firing. When a ball hit the water it would often go skipping over the surface in great bounds: the first impact, however, was by far the most deadly.

The great guns were the man-of-war’s chief armament, of course; but they were not the only weapon aboard, by any means. She also carried muskets, for the use of the Marines and the small-arms men in the fighting-tops, pistols, axes and cutlasses for boarding, stinkballs (made of pitch, resin, brimstone, gunpowder and asafoetida in an earthenware pot: it was set on fire and thrown so as to burst among the enemy and overwhelm him with the stench), and grenades for tossing on to the enemy’s deck, and boarding-pikes to repel him if he tried to come over the side. We might even add soot to the list, since Lord Cochrane, setting about the 32-gun frigate El Gamo with his 14-gun brig Speedy in 1803, made his men black their faces in the galley before boarding, to the unspeakable dismay of the Spaniards, who yielded less to the Speedy’s little 4-pounders than to the truly hideous appearance of her crew.

Table showing the size and weight of long guns and carronades

Table showing the range of guns and carronades

From the man-of-war’s armoury, a selection of weapons.