The Ship’s Company

Now for the men who sailed the ships and fought the guns, and first the officers. Let us take a boy who wants to go to sea and follow him through his career as an officer from bottom to top; and let him be a courageous boy with a cast-iron digestion and lucky enough not to put his head in the way of a cannon-ball, so that he may stay the course. He is a typical boy of quite good family – probably a sea-officer’s son or, like Nelson and Jane Austen’s brothers, a parson’s – but he is not highly educated, since he goes to sea when he is twelve or fourteen, and he has not had much time for school. (Officially the earliest age was eleven for officers’ sons and thirteen for the rest, but no one took much notice of the regulation – seven-year-olds were not unknown.) Before he can go to sea his people have to find some captain who is willing to take him aboard, for this is almost the only way to become an officer. They succeed, and the young hero joins his ship with his sea-chest: it is filled to over-flowing, since the captain has not only insisted on the boy’s parents giving him an allowance of as much as £50 a year if it is anything like a crack ship, but he will also have sent them a list of necessities. Here is a moderate example:

1 uniform coat superfine cloth

1 uniform coat second best

1 round jacket suit

1 surtout coat and watch-coat

3 pairs of white jean trowsers and waistcoats

3 pairs of nankeen ditto and 3 kerseymere waistcoats

2 round hats with gold loop and cockade

1 glazed hat, hanger (or dirk) and belt

18 linen shirts, frilled

12 plain calico shirts

3 black silk handkerchiefs

12 pocket cotton ditto

12 pairs of brown cotton stockings

6 pairs of white cotton stockings

6 pairs worsted or lamb’s wool stockings

2 strong pairs of shoes and 2 light pairs

6 towels and 3 pairs of sheets and pillow-cases

2 table-cloths about 3 yards long

A mattress, 3 blankets and a coverlet

A set of combs and clothes-brushes

A set of tooth-brushes and tooth-powder

A set of shoe-brushes and 12 cakes of blacking or ½ doz. bottles of ditto

A pewter wash-hand basin and a pewter cup

A strong sea-chest with a till and 2 trays in it, and a good lock with 2 keys

A quadrant and a small day and night glass

A silver table-spoon and tea-spoon

A knife and fork, and a pocket-knife and penknife

A log-book and journal with paper, pens and ink

Robinson’s Elements of Navigation

The Requisite Tables and Nautical Almanac

Bible, prayer-book

When going on a foreign station, an additional dress-suit, with more light waistcoats, a cocked hat, and some additional linen.

He reports his presence to the officer of the watch and he is taken to the midshipmen’s berth: this is likely to be something of a shock to him, since it is a dank, smelly, cheerless hole with no light or air and precious little in the way of food or comfort, very far down in the ship. The midshipmen’s berth: but he is not a midshipman – far from it. He is rated first-class volunteer if there is room for one on the ship’s books, or captain’s servant or even able seaman if there is not, and he will not become a real midshipman for a couple of years. But he does not black the captain’s boots, of course, nor attempt an able seaman’s duties; he and all like him are called ‘the young gentlemen’ and he wears a midshipman’s uniform (blue coat with a white patch on the collar, white breeches and cocked hat for formal occasions, otherwise blue jacket with blue or white trousers and a top hat, and a sword or dirk). Above all, he walks the quarterdeck, the officers’ preserve. He has to walk it for six years, learning his duty aloft and on deck, going to the ship’s schoolmaster in the mornings for mathematics and navigation, and keeping his official journal; and all this time, whether he is captain’s servant, midshipman or master’s mate (a senior midshipman) he is in fact only a rating, liable to be disrated at his captain’s pleasure or even turned ashore; and if he behaves badly he can be punished, often being sent to the mast-head like the young gentleman in the picture, to spend several hours there, repenting of his sins.

At the end of his six years at sea he goes to the Navy Office, bearing certificates of competence and good behaviour from his captains, his journals, and perhaps a paper to say he is twenty. In theory this was the minimum age for a lieutenant, but in fact there were some of fifteen and sixteen. Six years on the ship’s books, two of them as a midshipman, was insisted upon, however.

So here he is at the Navy Office with a trembling heart, trying to remember the difference between port and starboard; and here they put him through an oral examination in seamanship and navigation. He is not a booby: he has learnt a good deal in his six years afloat; and he gets through. He has ‘passed for lieutenant’! He is charmed, delighted, but still very anxious; for it is one thing to pass and quite another to be given the precious commission. However, he has done well at sea, his captains speak well of him, his family has some influence in politics or at the Admiralty, and one day there arrives a beautiful piece of paper covered with official seals and signatures, reading:

By the Commissioners for executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of Great Britain and Ireland &c and of all His Majesty’s Plantations &c

To Lieutenant William Blockhead, hereby appointed Lieutenant of His Majesty’s Ship the Thunderer

By Virtue of the Power and Authority to us given We do hereby constitute and appoint you Lieutenant of His Majesty’s Ship the Thunderer, willing and requiring you forthwith to go on board … Strictly charging and Command-ing all the Officers and Company belonging to the said Thunderer subordinate to you to behave themselves jointly and severally … with all due Respect and Obedience … And you shall likewise to observe and execute … what orders and directions … you shall receive from your Captain or any other your superior Officers … Hereof nor you nor any of you may fail as you will answer the contrary at your peril.

Now he is a real officer at last, with the King’s commission. He comes down on his poor father for a splendid new uniform (a blue coat with white cuffs and white lapels reaching right down his front, white waistcoat and breeches for full dress to be worn on grand occasions, and a plainer blue coat, often worn with trousers or blue breeches, for ordinary wear). He hopes this will be the last time he will have to do so, for now he is earning no less than £5 12s od a month, and there is always the golden prospect of prize-money. His father hopes so too.

He joins the Thunderer, 74, his commission is solemnly read out to the ship’s company, and he takes up his quarters in the ward-room, together with the other lieutenants, the Marine officers, the master, the surgeon, the chaplain and the purser; it is a handsome room in a 74, with plenty of air and light coming through the great stern window, and he even has a tiny cabin of his own. He forswears the squalor of the midshipmen’s berth for ever and settles down to his new duties. The years go by; and usually he moves from ship to ship, gaining a great deal of experience. He becomes more and more senior on the lieutenants’ list as his elders are killed or promoted, and in time he is first lieutenant, no longer keeping a watch but responsible for the day-to-day running of the ship, her discipline and her appearance. He draws no extra pay, but he is next in line for promotion, and at last it comes – his ship distinguishes herself in battle and her first lieutenant is made master and commander. He leaves the Thunderer after a last splendid party, buys another uniform (a blue gold-laced coat and white breeches for full dress, the same coat and blue breeches for undress) and waits to be given a command of his own. This is another anxious period, for he knows very well that there are about four hundred commanders on the Navy List and no more than about a hundred sloops, the only vessels they can command.

And now, while he is waiting, stirring up all his friends to use their influence, I will say something about uniforms. It is a very curious fact, but before 1748 the Royal Navy had none at all: the officers wore what they thought fit – often red coats, sometimes old tweed breeches at sea, and any kind of hat that caught their fancy. Then in that year uniform was laid down for the officers, but it was not until 1857 that the men had one – they fought the Battle of Trafalgar in anything from petticoat breeches (a kind of depraved kilt dating from the middle ages) to canvas trousers, with fur caps, top hats or handkerchiefs on their heads, and jerseys or chequered shirts; though most wore the purser’s slops, which were roughly of a pattern. But although he had no uniform, the man-of-war’s man could be recognized at once, particularly when he was in his shore-going rig: this usually consisted of a shiny black glazed tarpaulin hat (hence Jack Tar for a sailor) with a long dangling ribbon embroidered with the name of his ship, a bright blue jacket with gilt buttons down the right side, very broad, loose trousers, white or blue, tiny black shoes with bows or silver buckles, a shirt, white, spotted, striped or coloured, open at the collar, and black silk handkerchief loosely knotted round the neck, and a long scarlet waistcoat, the whole decorated with ribbons at the seams, for glory. As well as this he often had little gold earrings and a long swinging pigtail (those whose hair did not grow would sometimes eke it out with oakum), so that there was no mistaking the man-of-war’s man, particularly as he chewed his tobacco rather than smoking it like a Christian. I will also say something about sloops. Rightly speaking, a sloop is and always was a one-masted fore-and-aft vessel; but the Admiralty extended the term to cover ships and other craft that could be commanded by a master and commander, so that when a man-of-war brig had a lieutenant as her captain she was a brig (with two masts), but the moment a commander took her over she became a mere sloop, to the unspeakable amazement of landsmen.

Our young commander was born lucky. He has his sloop in a month or two – she takes a French corvette of equal force and he is promoted again. He is posted into a frigate, for he is now a post-captain. As a commander he was called Captain Blockhead by courtesy, and of course he was the captain of his ship; but now he is a full-blown captain and he is so addressed in official letters by the Admiralty. This time he does not have to buy a new uniform: his old coat will do, and all that is needed is to shift his epaulette from his left shoulder to his right, with the comforting reflection (if his promotion is before 1812) that when he is a captain of three years’ seniority he will wear two, one on each shoulder, and the even more comforting reflection that from now on his promotion is automatic. Many of his former shipmates have stuck at lieutenant, many at commander, but the post-captains move steadily up the list, and now nothing but death or very shocking misconduct will prevent him from being an admiral at last. After some years in frigates he is given a ship of the line, and slowly he climbs the captains’ list until at last he is at the top. The oldest of all the full admirals dies, and everyone moves up a step – our post-captain is made a rear-admiral! There is one last anxiety in his mind, however: he may be given no flag – he may be only a ‘yellow admiral’, condemned to live the rest of his life ashore on half-pay. But his luck still holds, and not only is he made rear-admiral of the blue but he is given a squadron to command. He goes aboard his flagship, hoists his blue ensign at the mizen; the squadron salutes it with thirteen guns and they proceed to sea. (The Navy never goes: it always proceeds.) But however well he fights it makes no difference to his promotion. He moves up the flag-list automatically – no one can get ahead of him and he cannot get ahead of anyone else, no matter what victories he may win. Rear-admiral of the blue, of the white, of the red. (In the seventeenth century, when very numerous fleets were engaged in the Dutch wars, the British fleets were divided into three squadrons, the red in the centre, the white in the van and the blue in the rear; and each squadron had its own admiral, vice-admiral and rear-admiral, the admiral of the red squadron being the admiral of the fleet.) Then vice-admiral of the blue, the white, hoisting his white ensign at the fore (this was the highest rank that Nelson ever reached), and of the red. Then admiral, full admiral: and at last, an old, old, very old man, he hoists the union flag at the main, for he is the most senior of them all, the admiral of the fleet.

I have spoken of other officers in the ward-room, the master, the surgeon and the purser: they messed in the ward-room and they had the right to walk the quarterdeck, but they were not commissioned officers – they held a warrant from the Navy Office and they never had quite the standing of the others. The master was a relic from the times when sailors sailed the ships and soldiers did the fighting, and he was still responsible for the navigation; he usually began as a midshipman, became a master’s mate, and then, having few social advantages and no influence, gave up all hope of a commission, accepted a warrant and so reached the highest rank that he was ever likely to attain. The surgeon was the ship’s medical man, of course; and the purser looked after the ship’s provisions and the slops, or clothes that were sold to the men at sea; he had almost nothing to do with pay. The purser was not often a popular officer, and ‘pusser’s tricks’ meant any kind of swindle with food, drink, tobacco and clothes, the most notorious being ‘purser’s eights’, or his habit of receiving food at sixteen ounces to the pound and serving it out at fourteen, keeping the odd two for himself.

There were other warrant officers, such as the boatswain, who looked after the rigging, sails, anchors, cables and cordage, and who hurried the men to their duty, and the gunner and the carpenter, who were of great importance in the life of the ship: they usually rose from the lower deck, and they messed by themselves, not in the ward-room.

The lower deck itself was made up of the great mass of the ship’s people – all the ratings from boy, third class (the lowest form of marine life) to able seaman. The captain appointed the petty officers such as the quartermasters, ship’s corporal, boatswain’s mate and so on from among them, but it made little difference to their sense of being the same kind of men. They nearly all lived and messed together on the lower deck between the guns, slinging their hammocks from the low beams overhead. They were allowed fourteen inches a man, but as they were divided into two watches, larboard and starboard, each on duty in turn, they usually had the luxury of twenty-eight inches to lie in: some 500 men packed into a space about 150 feet long and 50 at the widest. Their life was very hard, often dangerous, and always ill-paid; what is more, their meagre pay was invariably kept six months in arrears, in the hope that this would prevent them from running away. If their food had been good in the first place and if it had been honestly served out and decently cooked, it would not have been too bad by the standards of the time; but generally this was not the case. Indeed, it was usually so bad that when they could catch them, the men often ate rats, or millers as they were called in the service, because of their dusty coats as they got into the flour and dried peas. They were neatly skinned and cleaned and laid out for sale: hungry midshipmen would buy them too, and Admiral Raigersfeld, looking back on his youth, says, ‘They were full as good as rabbits, although not so large.’ Speaking of the bread he observes, ‘The biscuit that was served to the ship’s company was so light, that when you tipped it upon the table, it almost fell into dust, and thereout numerous insects, called weevils, crawled; they were bitter to the taste, and a sure indication that the biscuit had lost its nutritious particles; if instead of these weevils, large white maggots with black heads made their appearance (these were called bargemen in the Navy), then the biscuit was considered to be only in its first state of decay; these maggots were fat and cold to the taste, but not bitter.’

Here is a list of the provisions that were usually served out:

Sunday, 1 lb of biscuit, 1 lb of salt pork, half a pint of dried peas.

Monday, 1 lb of biscuit, half a pint of oatmeal, 2 oz of sugar and butter, 4 oz of cheese.

Tuesday, 1 lb of biscuit, 2 lb of salt beef.

Wednesday, 1 lb of biscuit, half a pint of peas and oatmeal, 2 oz of butter and sugar.

Thursday, 1 lb of biscuit, 1 lb of pork, half a pint of peas, 4 oz of cheese.

Friday, 1 lb of biscuit, half a pint of peas and oatmeal, sugar, butter and cheese as before.

Saturday, 1 lb of biscuit and 2 lb of beef.

When beer was to be had, they were given a gallon a day; when it was not, which was most of the time, they had their beloved grog. This was rum, mixed with three times the amount of water and a little lemon-juice against scurvy: they were given a pint of grog at dinner time and another for supper, and they often got dead drunk, particularly when they saved up their rations and drank it all at once.

They were nearly always uneducated, often unable to read or write, and they had generally lived very hard all their lives; but there were some wonderful men among them, brave, very highly skilled at their calling, magnificently loyal to their shipmates and to their officers if they were well led. As Nelson said, ‘Aft the more honour, forward the better man.’ By aft he meant the quarterdeck, abaft the mainmast, the officers’ part of the ship, and by forward he meant the men, the foremast jacks, who lived forward of the mainmast.

They were brought together partly by free entry (popular officers like Saumarez or Cochrane could always man their ships with volunteers) and partly by the press-gang. Impressment was a rough and ready form of conscription, and the idea was that seamen should be taken from merchant ships or seized on land and compelled to serve in the fleet for as long as their services were required. In practice it meant that a short-handed ship (and a man-of-war needed an enormous crew – roughly ten times the size of a merchantman’s) would send an officer ashore with a strong party of powerful, reliable sailors armed with pistols and cutlasses for show and clubs for use to catch any reasonably able-bodied man they could lay their hands on – seamen for choice but anyone who could haul on a rope if sailors were not to be found. There was also the impress service itself, where shore-based officers did much the same, sending their prey to receiving ships, whence they were drafted to the men-of-war. Then, in 1795, there was the quota-system, by which each county was required to provide so many men for the Navy. The counties responded by getting rid of their undesirables – thieves, poachers, paupers, general nuisances, nearly all of them landsmen, or as the men-of-war’s men called them, grass-combing lubbers.

Faced with recruits of this kind, some of them straight from gaol, many officers tightened the already severe discipline of their ships: flogging became more frequent and more savage, and ‘starting’, hitting people with a cane or a rope’s end, to make them jump to their work, grew far worse. The real seamen came in for a good deal of this, and they began to feel even more ill-used, particularly as these alleged volunteers, who were sometimes given the choice between transportation and the Navy, received a bounty of as much as £70 – well over four years’ pay for an able seaman. The sailors were ill-used, they were knocked about, they were not paid at all when they were sick or wounded and off duty, their pay was always in arrears, they were allowed almost no shore-leave at home, and they were cheated out of their rations. At Spithead in 1797 they mutinied. This was a very important mutiny, not like the small though sometimes bloody outbreaks against a tyrannical brute of a captain: the men refused to take the fleet to sea unless their grievances were put right. They were extraordinarily moderate, merely petitioning the Admiralty, in the most respectful terms, for an increase in pay to bring their nineteen shillings a month up to the soldier’s shilling a day, that their pound of provisions should be sixteen ounces, that fresh vegetables, instead of flour, should be served out when they were in port, and that they might be allowed a short leave to visit their families. They said they should certainly take their ships to sea if the French fleet came out; but until then they should stand by their demands. Nelson, among other officers, stated that ‘his heart was with them’ and that he was against ‘the infernal system’ of paying them by ticket rather than cash, so that they often had to leave their families penniless for years. In the end the Admiralty gave way; a bill was hurried through parliament, the mutineers were given the King’s pardon, and they carried Lord Howe, the admiral who had conducted the negotiations, shoulder-high through the streets of Portsmouth.

Before giving a table showing the pay of the Navy after these improvements and after some rises for the officers too, I will quickly run through the stations and duties of the crew. The older, most highly skilled able seamen were stationed on the forecastle; they were called sheet-anchor or forecastle-men, and there would be about 45 of them in a 74. Then came the topmen, all able seamen, but young and active, since all the duty above the lower yards fell to them: counting fore, main and mizen topmen, there would be 114 altogether. Then came the afterguard, mostly ordinary seamen and landmen, who worked the after-braces, main, mizen and lower stay-sails: they would number about 60. Lowest of all in public esteem were the waisters, a numerous body (115) of landmen and other poor creatures stationed in the waist to look after the main and fore sheets and do all the dirty, unskilled work that was going. Then there were the quartermasters, old, reliable seamen who conned the ship, directing the helmsman; and the quarter-gunners, each of whom had charge of four guns. Last there were the idlers, or people who did not keep a watch but only worked from dawn till eight at night, such as the master-at-arms, the cook, the sailmaker, the barber and so on.

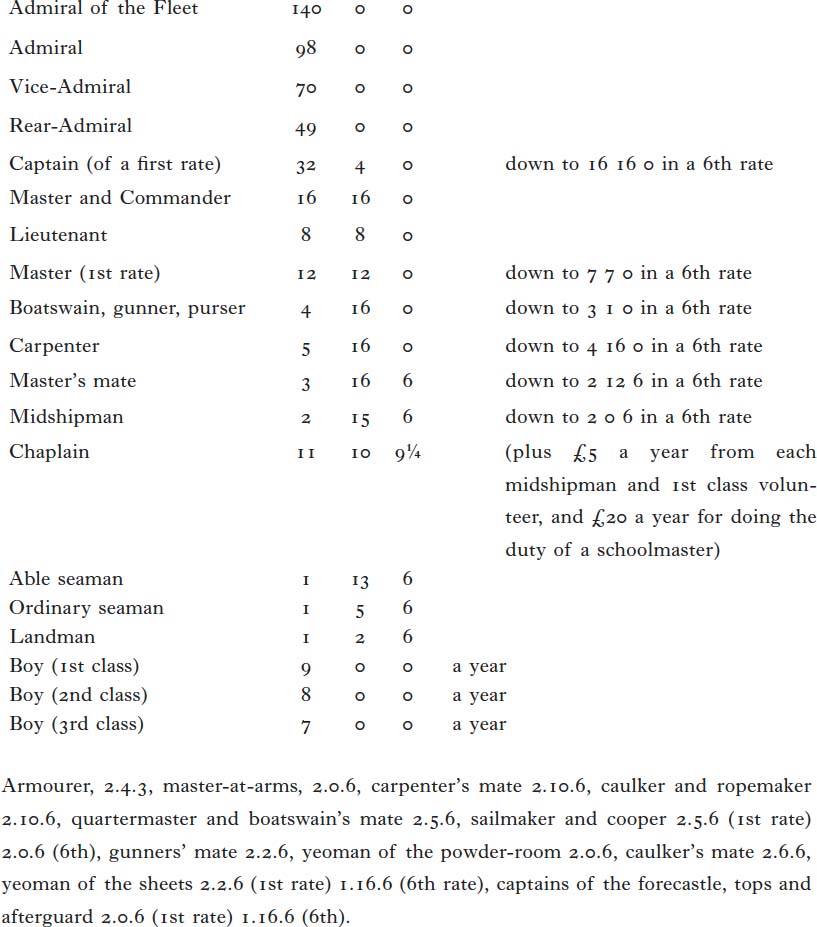

Pay (per lunar month – there are 13 lunar months in a year)