Life at Sea

Officially the ship’s day ran from noon to noon, but to most of those aboard it seemed to begin about dawn or earlier, just before eight bells in the middle watch, or 4 a.m., when the boatswain’s mates piped ‘All hands’ down the fore and main hatchways and hurried below roaring ‘Larboard watch ahoy! Rise and shine. Show a leg there! Out or down, out or down. Rouse out, you sleepers,’ and cutting down the hammocks of those who preferred to stay in bed, having had no more than four hours of sleep.

The business of the ship, when at sea, had to go on right round the clock, naturally, since she could not be tied up to a post for the night; and to deal with this situation the ship’s company was divided into two watches, larboard (or port) and starboard, and the 24 hours were cut into seven periods of duty, also called watches, thus:

Noon to 4 p.m., afternoon watch |

8 p.m. to midnight, first watch |

|

4 p.m. to 6 p.m., first dog-watch |

midnight to 4 a.m., middle watch |

|

6 p.m. to 8 p.m., last dog-watch |

4 a.m. to 8 a.m., morning watch |

|

8 a.m. to noon, forenoon watch. |

The odd number of watches meant that the night duty was fairly shared: the larboard watch would turn out at midnight one day and the starboard the next. But the two-watch system also meant that most of the men never had more than four hours’ sleep at a time. The officers were divided into three watches, which gave them longer in bed, but on the other hand they were never allowed to sleep on duty whereas in calm weather the men who were not at the wheel or looking out might drowse in most ships when there was nothing to be done. The passage of time was marked by strokes on the ship’s bell, one stroke for every half hour: so eight bells meant the end of the ordinary watch. And at every stroke the log was heaved, the speed of the ship and her course marked on the log-board, and the depth of water in the well reported by the carpenter or one of his mates, while at night all the sentinels called ‘All’s well.’

To go back to eight bells in the middle watch: as they were struck, so the watch that had been sleeping, the larboard watch, let us say, was mustered and the watch on duty dismissed to get what sleep they could before hammocks were piped up. About this time the idlers or day-men were called, and at two bells the decks were cleaned, first being wetted, then sprinkled with sand, then scrubbed with holystones great and small, then brushed, and lastly dried with swabs. This took until six bells, and at seven bells hammocks were piped up. Each man took his hammock (it had a number on it, corresponding with the number on the beam where it was slung), rolled it into a tight cylinder and brought it up on deck, where the quartermasters stowed them in the hammock-nettings along the sides: this aired the bedding after the awful fug below, provided some protection in case of battle (a hammock would stop a musket-ball and deaden a cannon-ball), and cleared the lower deck for cleaning.

At eight bells in the morning watch hands were piped to breakfast, which was biscuit, burgoo (a kind of milkless porridge) and, in some ships, cocoa. Half an hour was allowed for this feast. Now it was the forenoon watch and the starboard men were on duty again (the two watches were often called the larbowlines and starbowlines). The watch below cleaned the lower deck, with water if the weather was fine and the ports could be opened to dry the planks, otherwise with dry sand, holystones and brooms; then they might be allowed to rest, but some captains preferred them to exercise the great guns or to practise reefing topsails.

At eight bells in the forenoon watch the officers took the noon observations of the sun to fix the ship’s position, the watch was changed and all hands piped to dinner. The men divided themselves into messes, usually of eight friends, and one of the eight was appointed their cook for the day: he received the mess’s ration from the ship’s cook in the galley, saw to its dressing and brought it to his messmates as they sat at their hanging table between the guns. It took about half an hour to eat, and then at one bell the fifer on the main deck began to play ‘Nancy Dawson’ or some other tune that meant the grog was ready. The cooks darted up the ladder with little tubs or blackjacks to the butt where the master’s mate had publicly mixed the rum, water and lemon-juice. He served it out with great care, and with great care the cooks carried it down, while their messmates banged their plates and cheered. It was shared out, but in tots slightly smaller than the tot the officer had used, so that a little was left over: this was called the cook’s plush, and he drank it as a reward for his trouble.

At two bells dinner was over: the larbowlines were on duty, and generally the starbowlines were turned up as well for exercise. At six bells in the afternoon watch, or 4 p.m., hands were piped to supper, which was much the same as breakfast, but with another issue of grog. Supper took half an hour; by this time it was one bell in the first dog-watch, and a little later the drum beat to quarters. All hands hurried to their action-stations and the guns were cast loose. The midshipmen and then the lieutenants inspected the men under their charge and eventually the first lieutenant, having received their reports, reported ‘All present and sober, sir, if you please,’ to the captain, who would then have the guns run in and out and perhaps fired, or topsails reefed or furled and loosed.

When this was over the drum beat the retreat, hammocks were piped down, and at eight bells the watch was set. The larboard watch went below, straight to sleep; lights were put out on the lower deck, and the starboard watch took up its duty. At eight bells the larbowlines were called again for the middle watch, and four hours later, towards dawn, the day began again with the cleaning of the decks, this time by the starboard watch.

As you see, the men had at the most four hours of sleep one night and seven the next, with what they might snatch during the day. But in any emergency, such as reducing sail in dirty weather or tacking ship, or the least hint of action, all hands would be called and the watch below tumbled up, perhaps with no sleep at all.

This was an ordinary ship’s day; but on others the routine changed, particularly on Thursdays and Sundays. On Thursdays hammocks were piped up at 4 a.m.; the hands spent the morning washing their clothes and the afternoon making and mending them. On Sundays hammocks were piped up at six bells and breakfast was at seven bells; then the ship and everything in her was brought to a high state of perfection, the men washed, shaved and put on their clean good clothes; they combed and plaited one another’s pigtails, and at five bells in the morning watch they were mustered by divisions, the lieutenant of each division inspecting them as they stood in lines, toeing one particular seam on the deck. Then the captain, having inspected them too, went right round the ship with the first lieutenant to see that everything, including the cook’s great coppers, was spotless. It usually was, but if he found anything dirty or out of order, then there would be the very devil to pay. After the captain’s inspection there was a service on the quarterdeck, conducted by the chaplain if the ship carried one and by the captain if she did not. Some captains would preach a sermon, but others merely read out the Articles of War.

Then the men were piped to dinner, which might include such delights as figgy-dowdy, made by putting ship’s biscuits into a canvas bag, pounding them with a marlinspike, adding bits of fat, figs and raisins, and boiling the whole in a cloth. Until supper-time they were as free as the work of the ship allowed. If they were in company with other ships or in port they would often go ship-visiting; or the liberty-men might be allowed on shore, especially in such places as Malta or Gibraltar, where it was easy to catch them if they tried to desert. After supper they were mustered, each man passing in front of the captain as his name was called and checked off on the ship’s books: and when the muster was over it was time for quarters again.

Some ships had special days for punishment; others might punish all round the week. It always took place at six bells in the forenoon watch. The boatswain’s mates piped ‘All hands to witness punishment’ and the men flocked aft, where the Marines were drawn up with their muskets on the poop and all the officers were present in formal dress, wearing their swords. The master-at-arms brought his charges before the captain and the misconduct of which they were accused (usually drunkenness) was publicly stated. If the man had anything to say for himself he might do so, and if any of his particular officers saw fit they might put in a word for him. Having considered the case, the captain gave his decision – acquittal, reprimand or punishment. This might be extra duties or stoppage of grog, but often it was flogging. ‘Strip,’ the captain would say, and the seaman’s shirt came off. ‘Seize him up,’ and the quartermasters tied his hands to a grating rigged for the purpose upright against the break of the poop, reporting, ‘Seized up, sir.’ Then the captain read the Articles of War that covered the offence, he and all the others taking off their hats as he did so. He said, ‘Do your duty,’ and a boatswain’s mate, taking the cat-of-ninetails out of a red baize bag, laid on the number of strokes awarded. Some hands screamed, but the regular man-of-war’s man would take a dozen in silence.

It was a vile, barbarous business by our standards, and an ugly one even by the more brutal standards of the time – no women were allowed to witness it. Many captains, Nelson and Collingwood among them, hated flogging, and there were ships that kept excellent taut discipline without bringing the cat out of the bag for months on end; but there were other captains, such as the infamous Pigot of the Hermione whose crew eventually hacked him to pieces off the Spanish Main, who rigged the grating almost every day and whose sentences, instead of Collingwood’s six, nine or at the most twelve strokes, actually ran into the hundreds.

These men were despised by their fellow-officers, not only for being inhuman brutes but for being inefficient brutes into the bargain. A happy ship was the only excellent fighting-machine – a ship whose well-trained, well-led crew would follow their officers anywhere, a ship that would fight like a tiger when she came into action.

Action was the goal of every sea-officer; and when it came, how a ship sprang to life! The drum beat to quarters, the men raced to their familiar stations and cast loose their guns, the officers’ cabins disappeared, the thin bulkheads, the furniture and all lumber vanishing into the hold to give a clear sweep fore and aft, the decks were wetted and sanded against fire. Damp cloth screens appeared around the hatches; in the magazines the gunner and his mates served out powder to the boys with their cartridge-cases; the yards were secured with chains; the galley fires were put out; and all this happened in a matter of minutes.

If it was a fleet action the captain and his first lieutenant on the quarterdeck would have their eyes on the admiral or the repeating frigates almost as much as on the enemy, for it was of the first importance to follow the admiral’s signals. The traditional fleet action was begun with both sides manoeuvring for the weather-gage – that is, trying to gain a position to windward of the enemy so as to have the advantage of forcing an engagement at the right moment. Then the two fleets would form their line of battle, usually with about four hundred yards between the ships in each line to allow for change of course; and the idea was that each captain should engage his opposite number on the other side. The Fighting Instructions insisted that the battle-line should be rigidly maintained, and any captain who strayed from it was liable to be court-martialled: he must keep his station, and, since those who were not next to the admiral in this straight line could not see his signals because of the sails of the next ahead or astern, they had to watch the frigates (which always lay outside the line) whose duty it was to repeat the flagship’s orders.

But these battles rarely led to a decisive result, and in 1782 in the West Indies, Rodney disobeyed the Instructions, broke the French line and captured the enemy flagship and five others. In the war that began in 1793 nearly all the great fleet actions disregarded official tactics. “Never mind manoeuvres,” said Nelson. “Always go at them.” This he did at Saint Vincent, the Nile and Trafalgar, just as Duncan did at Camperdown: after the first formal approach the fleet action quickly became a wild free-for-all in which better gunnery and seamanship won the day. At St Vincent, for example, Sir John Jervis, with Nelson under his orders and fifteen ships of the line, took on a Spanish fleet of 27, including seven first rates, captured four and beat the rest into a cocked hat.

Another and more frequent sort of action was that fought between frigates, sometimes in small squadrons but more often as single ships; and in these everything depended on the captain – he fought his ship alone. One of the finest was the battle between HMS Amethyst, 36, and the French Thétis, 40. Late on a November evening in 1808, close in with the coast of Brittany, Captain Seymour caught sight of the Thétis slipping out of Lorient with an east-north-east wind, bound for Martinique. He at once wore in chase, and by cracking on sail he came up with her by about 9 p.m., although she was a flyer. The Thétis, running a good nine knots, suddenly shortened sail and luffed up, turning to rake the Amethyst with all her broadside guns. The Amethyst was having none of that: she swerved violently to port and then, the moment the French broadside was fired, to starboard, shooting up into the wind just abreast of the Thétis. And now began a furious cannonade, both ships battering one another at close range as fast as they could load and fire. The Thétis, as well as her extra guns, had 100 soldiers aboard, and they joined in with their musketry: the din was prodigious. After half an hour, when the Amethyst was a little ahead, the Thétis tried to cross under her stern and rake her, but there was not room and she ran her bowsprit into the Amethyst’s rigging amidships: in a few moments they fell apart, and still running before the wind they continued to hammer one another like furies. After another half hour of this the Amethyst forged ahead, put her helm hard a-starboard, crossed the Thétis’ hawse and raked her, the whole broadside sweeping the Frenchman’s deck from stem to stern. Again they ran side by side, lighting up the night with their incessant fire; but at 10.20 the Amethyst’s mizenmast came down, smashing the wheel and sprawling over her quarterdeck. The Thétis shot ahead, meaning to cross and rake the Amethyst in her turn. But before she could do so, her own mizen went by the board. Once more the frigates were side by side, each hammering the other with a murderous fire. At 11 the Thétis had had enough: she steered straight for the Amethyst to board her. Captain Seymour saw that they would collide bow to bow and that the rebound would bring their quarters together. He gave the order not to fire. The ships struck, sprang apart, and then just before the Frenchman’s quarter swung against the Amethyst he cried ‘Fire!’ and the whole broadside tore into the Thétis’ boarders as they stood ready to spring from her quarterdeck. She could only reply with 4 guns, and a moment later the ships were locked together, the Amethyst’s best bower anchor hooked into the Thétis’ deck. So they lay for another hour and more, their guns still blazing furiously. The Thétis was set alight in many places, her fire gradually slackened, and at twenty minutes after midnight Captain Seymour called ‘Boarders away!’, leapt aboard with his men and carried her at the point of the sword. A little later the Frenchman’s two remaining masts fell over the side. Her hull was terribly shattered, and in her very courageous resistance she had lost 135 killed, including her captain, and 102 wounded. The Amethyst lost 19 killed and 51 wounded.

The comparative strength of the two frigates:

Amethyst |

Thétis |

|||

Broadside guns |

21 |

22 |

||

broadside weight of metal |

467 lb |

524 lb |

||

crew |

261 |

436 (counting the 106 soldiers) |

||

size |

1046 tons |

1090 tons |

The rewards of victory were very great. The successful sea-officer enjoyed an honour, glory and popularity that no other man could earn. And after the great fleet actions the admirals were given peerages, huge presents of money and pensions of thousands a year; the victorious frigate-captain was made a baronet; first lieutenants were promoted commander and some midshipmen were given their commissions; but apart from public praise the rewards did not usually go much lower than that. For tangible advantages the ship’s company looked to something else – to prize-money.

Whenever a man-of-war captured an enemy ship and brought her home she was first condemned as lawful prize and then sold. The proceedings were shared thus:

before 1808 |

after 1808 |

|||

Captain |

3/8 |

2/8 |

||

Lieutenants, master, captain of Marines, equal shares of |

1/8 |

1/8 |

||

Marine lieutenants, surgeon, purser, boatswain, gunner, carpenter, master’s mates, chaplain, equal shares of |

1/8 |

1/8 |

||

Midshipmen, lower warrant officers, gunner’s, boatswain’s and carpenter’s mates, Marine sergeants, equal shares of |

1/8 |

|

||

|

4/8 |

|||

Everybody else, equal shares of |

2/8 |

Before 1808 the captain had to give one of his eighths to the flag-officers under whose orders he served: after 1808, one third of what he received. If he were not under an admiral he kept it all in both cases.

From the point of view of mere lucre, leaving honour and glory aside, it was not very profitable to take an enemy man-of-war: she was usually shockingly battered by the time she surrendered, and in any case she carried nothing but a cargo of cannon-balls and guns. To be sure, there was head-money of five pounds for every member of her crew, but real wealth, real splendid wealth, came only from the merchant or the treasure ship, laden with silk and spice, or, even more to the point, with gold and silver. An East-Indiaman was worth a fortune, and a ship from the Guinea coast, laden with gold-dust and elephants’ teeth, meant dignified ease for life.

Back in 1743, when Anson, having rounded the Horn, having survived incredible hardships, and having sailed right across the Pacific, took the great Manilla galleon, he found 1,313,842 pieces of eight aboard her, to say nothing of the unminted silver. He brought it home, and 32 wagons were needed to carry it to the Tower of London: even a boatswain’s mate had well over a thousand guineas for his share, while Anson, an admiral and a peer of the realm, was a very wealthy man.

And in 1762, when it became clear that a war with Spain was inevitable, cruisers were sent out: two of them, the Active, 28, and the Favourite, 20, had information of a register ship from Lima to Cadiz. As Beatson, the contemporary historian, says, they ‘had the good fortune to get sight of her on the 21st of May, and immediately gave chase. In a few hours they were close along-side, when Captain Sawyer hailed them whence they came; and, on being answered from Lima, he desired them to strike, for that hostilities were commenced between Great Britain and Spain. This was a piece of news they were not prepared for; but after a little hesitation, they submitted. Possession was then taken of the vessel, the Hermione, which was by far the richest prize made during the war; the cargo and ship, etc., amounting to £544,648 1s. 6d.’

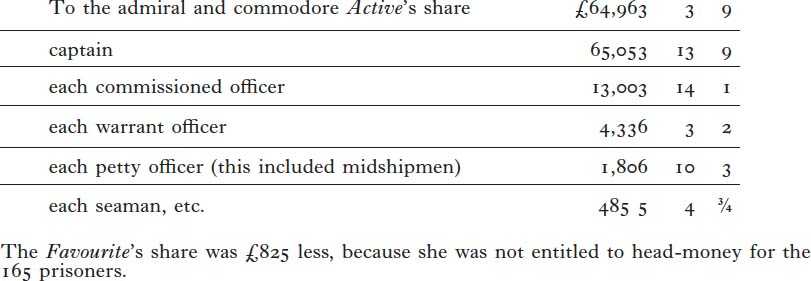

This splendid cake was cut up thus:

In 1804 much the same thing happened again: the Spaniards sent their treasure across the ocean, and off Cadiz there were four frigates of the Royal Navy waiting for it. It must be admitted that England had not formally declared war, but they took it just the same. This time there was a fight, the Spanish ships being frigates of their navy, and in the course of it one most unfortunately blew up. The other three struck, and they were found to be carrying 5,810,000 pieces of eight. However, the Admiralty in an odd fit of conscience, decided that this was not lawful prize (although the frigates had been ordered to go and take it) and that the money, apart from a small proportion, should go to the Crown; so in the end the poor captains had to content themselves with a mere £15,000 apiece. Still, seeing that the captain of a sixth rate then earned just over £100 a year, they had made 150 years’ pay in a morning, just as the seamen of the Active had made 36 years’ in an afternoon; and in any case, there might always be another Hermione round the next headland.

There never was another Hermione; but splendid prizes were still to be made, and the very real possibility of a fortune lying just over the horizon, to be won by a bold stroke, a few hours’ fierce action, added a certain charm to the sailor’s hard and dangerous life at sea.