Chapter 13

The Central Mediterranean

Fabrizio Antonioli,1 Francesco L. Chiocci,2 Marco Anzidei,3 Lucilla Capotondi,4 Daniele Casalbore,5 Donatella Magri6 Sergio Silenzi7

1 ENEA, Roma, Italy

2 Earth Science Dept. University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy

3 INGV, Rome, Italy

4 CNR, ISMAR, Bologna, Italy

5 University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy

6 Plant Biology Dept., University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy

7 ISPRA, Rome, Italy

Introduction

Because of their geologically young age and complex geological setting, central Mediterranean shelves show a large variability in morphology (width, slope, unevenness), stratigraphy (different thickness of depositional bodies resulting from the last climatic/eustatic cycle) and sedimentology (shelf-mud offshore of the main river mouths, bioclastic sediment in under-supplied areas). The overall morphology usually encompasses a well-defined shelf break as deep as 120 m to 150 m; above this depth, a well-developed erosional unconformity cutting across older deposits is present, overlaid by the depositional sequence formed in the last 20,000 years during the last sea-level rise and the present highstand of sea level. The thickness of such a sequence is highly variable, from many tens of meters offshore of the main rivers (e.g. the Po and Tiber) or in tectonically active areas (e.g. the Ionian Sea), to a few decimeters on insular shelves or on uplifting regions with arid climates (e.g. Apulia and the volcanic islands of the Tyrrhenian Sea). Accordingly, the shelf is floored by detrital siliciclastic sediment in well-fed areas that show sandy shorelines and muddy shelves with a mud line located at about 20 m, and by bioclastic sand and silt in underfed areas.

The morphology of the shelf is profoundly conditioned by the tectonic and sedimentary setting. In stable/uplifting and underfed areas, bedrock may outcrop and create a complex setting of shoals and paleo-headlands. In subsiding and well-fed areas the shelf is usually flat, with a slope of a few tenths of a degree.

Earth Sciences

Geodynamic setting of the central Mediterranean shelves

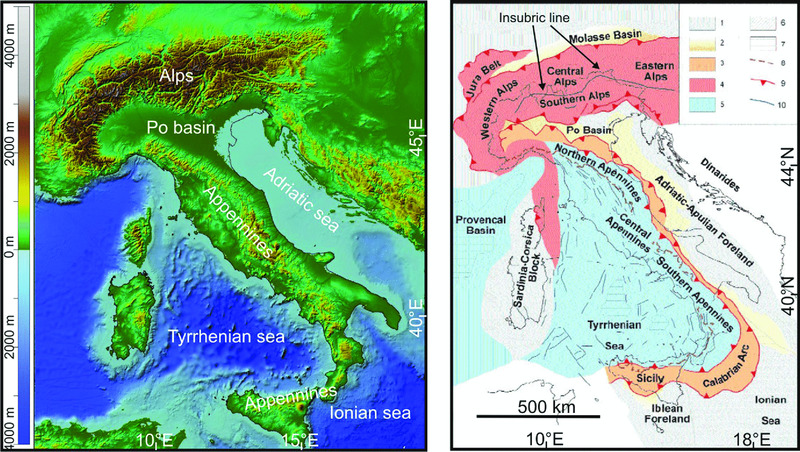

The central Mediterranean area is a complicated puzzle for geodynamic reconstruction. The main geodynamic factor controlling Mediterranean tectonics is the relative motion of Africa and Europe as a consequence of different spreading rates along the Atlantic oceanic ridge (e.g. Gueguen et al. 1998; Serpelloni et al. 2007). In this context, the geology of Italy can be traced from the Early Paleozoic Hercynian orogen, throughout the Mesozoic opening of the Tethys Ocean to the later closure and embayment of this ocean, during the Alpine and Apennine subductions (Scrocca et al. 2003). These latter formed two orogens (i.e. the Alps to the north, and the later Apennines along the Italian Peninsula and Sicily) that are the backbone of the geological and geomorphological setting of Italy (Fig. 13.1). There are very limited areas in Italy which are not part of these two thrust belts, notably the Apulian and Iblean forelands (Puglia region and southeast Sicily), a few areas on the Po Plain, and the island of Sardinia.

Figure 13.1 On the left, a digital elevation model of Italy and surrounding seas (data from www.gebco.net/); note the change from light blue to dark blue marks the approximate limit of the continental shelf. On the right, a simplified tectonic map of Italy and surrounding regions, modified from Scrocca et al. (2003) with permission. (1) foreland areas; (2) foredeep deposits (delimited by the –1000-m isobath); (3) domains characterized by a compressional tectonic regime in the Apennines; (4) thrust belt units accreted during the Alpine orogenesis; (5) areas affected by extensional tectonics in response to the eastward roll-back of the west-directed Apennine subduction; (6) outcrops of crystalline basement (including metamorphic alpine units); (7) regions characterized by oceanic crust; (8) Apennine watershed; (9) thrust; (10) faults.

The eastern part of the central Mediterranean is dominated by the Dinarides (Fig. 13.1). These form a complex fold, thrust and imbricate belt which developed along the northeastern margin of the Adriatic Sea (e.g. Dewey et al. 1973) or Apulia microplate (e.g. Dercourt et al. 1993). They may be considered as representing the ‘southern branch’ of the Alpine-Mediterranean orogenic belt, extending for about 700 km from the Southern Alps in the north-west to the Hellenides in the south-east. The main Dinaridic thrust-related deformations took place during either the Paleogene or the Miocene, when the complex tectonic structure of the region was formed (Korbar 2009). Fold, thrust and imbricate structures have mainly a northwest–southeast strike with a southwest-directed transport direction over most parts of the Dinarides, particularly in their central parts (e.g. Pamic et al. 1998).

The evolution of the Alpine chain is complex, but in broad terms it is the result of the subduction of Tethyan oceanic crust that resulted in a continent-to-continent collision between the European and African plates (Adria Promontory), and which occurred in several phases from the Middle Cretaceous to the Neogene. On the whole, the structure of the Alpine chain can be divided into two different structural and paleogeographic domains separated by the Insubric Line or Periadriatic Lineament, i.e. a series of very long faults running from west to east along the whole Alpine Arc (Fig. 13.1). The Northalpine domain, mainly made up of metamorphic rocks, is organized in folds and thrusts verging to the north, while in the Southalpine domain (or Southern Alps) the folds verge dominantly southward and they are made up mainly of sedimentary rocks.

The Apennines are a series of mountain ranges bordered by narrow coastlands that form the physical backbone of peninsular Italy for a total length of 1400 km (Fig. 13.1). The majority of geologic units of the Apennines are made up of marine sedimentary rocks (shales, sandstones, and limestones) which were mainly deposited on the southern margin of the Tethys Ocean in the Meso-Cenozoic. The basic tectonic evolution of the Apennines thrust belt-foredeep system may be considered as the result of the Late Oligocene-to-present northeastward roll-back of a west-directed slab (Malinverno & Ryan 1986; Doglioni 1991). This mechanism is, in fact, the most plausible explanation for the progressive eastward migration of the thrust fronts, the foreland flexure (and consequent shift of the foredeep basins) as well as the extensional processes along the internal Tyrrhenian back-arc basins (e.g. Faccenna et al. 2003). Paleo-reconstruction of the kinematics of the arc suggests up to 775 km of migration from the Late Oligocene up to the present along a transect from the Golfe du Lion to Calabria (Gueguen et al. 1998). The constant compression along the eastern margin induces the formation of great folds and pushes the Apennines against the Dalmatian coasts at a rate of 1 mm/year (Anzidei et al. 2001; 2005a; Serpelloni et al. 2005; 2007). The present-day foredeep basins are represented by the Po Plain and Adriatic Sea for the Northern Apennines, the Fossa Bradanica and Taranto valley for the Southern Apennines and the Catania-Gela Plain and Sicily Strait offshore for the Sicilian Apennines. Conversely, the western margin of the Apennines is characterized by extensional tectonics, with graben and half-graben structures paralleling the Tyrrhenian coast, which allowed the growth of several volcanic complexes, some of them still active.

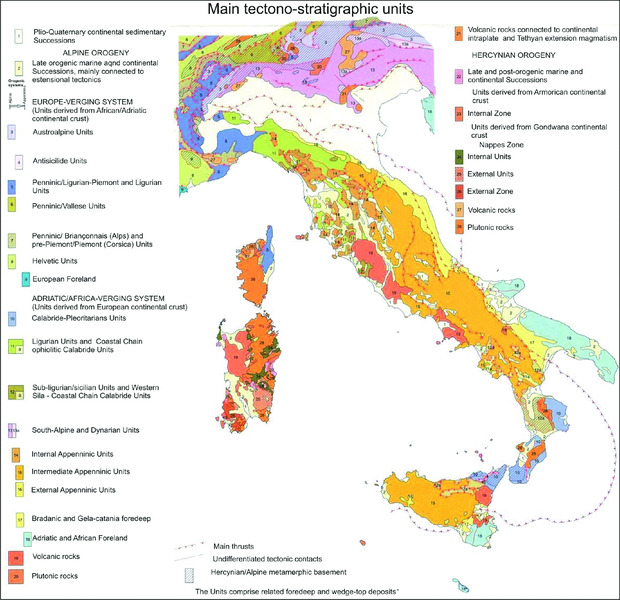

The geology of Italy is described in a series of 132 geological maps at a scale of 1:100,000; their production started in 1877 (www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/cartografia/ carte-geologiche-e-geotematiche/carta-geologica-alla-sca la-1-a-100000). A completely new update of the national geological cartography is at present being carried out in within the framework of the CARG (Geological CARtography) project. This update (ongoing since 1988) involves over 60 institutions including CNR (Italian Research Council), university departments and research institutes, as well as local authorities, with the aim of producing 652 geological sheets on a scale of 1:50,000, fully covering Italian territory. To date some 40% of these maps have been completed or are in progress (www.isprambiente.gov.it/Media/carg/). Notably, the 1:50,000 guidelines foresee geological mapping of marine areas that were not considered in the 1:1,000,000 geological sheets.

Recently, a geological map of Italy at 1:1,250,000 has been produced integrating the cartographic products of the CARG project together with the 1:100,000 national geological cartography and geological maps from the literature (www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/projects/soil-and- territory/the-geological-map-of-italy-1-250000-scale/ default; Fig. 13.2).

Figure 13.2 Map of the main tectono-stratigraphic units of Italy from the geological map of Italy at 1:1,250,000 scale (www.isprambiente.gov.it/en/projects/soil-and-territory/the-geological-map-of-italy-1-250000-scale/default). Reproduced with permission from ISPRA.

A relevant cartographic product is the Structural Model of Italy (Bigi et al. 1990). This model is compiled from gravimetric and aeromagnetic maps of Italy, as well as by detailed geo-structural maps of Italy at a scale of 1:500,000, where the Plio-Quaternary deposits of Alpine and Appennine foredeeps and the Plio-Quaternary sediment thickness are also shown. This publication constitutes the most important and fruitful integration of scientists with geological and geophysical backgrounds in a three-dimensional reconstruction of the anatomy of Italy and its geodynamic evolution.

In the 1970s, geological map sheets of the former Yugoslavia were published at a scale of 1:100,000 by the Federal Geological Institute Beograd, which also produced a schematic geological map at 1:500,000 (Federal Geological Institute Beograd 1970). More recently, geological and tectonic maps of the Alps and Dinarides were published by Pamic et al. (1998) and Schmid et al. (2004). In the last few years, a great effort has also been made recently to produce the first geological and morpho-tectonic map of the Mediterranean domain at a scale of 1:4,000,000 (Mascle & Mascle 2012).

Modern coastline

At present, the Italian GeoPortale Cartografico Nazionale (PCN; www.pcn.minambiente.it) represents the best available data source on the web concerning high-resolution cartography of Italy. The PCN is a data bank operated by the Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea, and it is based upon color and black and white digital orthophoto, digital elevation model (DEM), territorial and administrative data sources, place names (toponomastic), shoreline of seas and lakes, printed paper cartography of the Istituto Geografico Militare (IGM; www.igmi.org), which has been digitalized at a maximum scale of 1:1000, DEM by vector data, road network, and 3D models of the most relevant city centers. Moreover, vector data concerning hydrogeological risk, protected areas and land-use maps are available. All the data are referred to the WGS84 geographic coordinate system.

Recently, the Progetto Coste (Coast Project; www.pcn.minambiente.it/viewer/index.php?project=cos te) has been added to the PCN with the aim of analyzing the state of coastal systems, advancing research, how to plan the best use of land, defense and adaptation, marine strategy, the prevention of erosion, and Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Following the Piano Straordinario per il Telerilevamento, a high-resolution, remote-sensing project of the Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea, there will be a link to the PCN website for the LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data: at present the data covers over 30% of Italian territory, including coastal areas and shorelines. By processing such data it will be possible to obtain high-resolution digital surface models and digital elevation models.

Wetlands, deltas, marshes, lagoons, coastal lakes

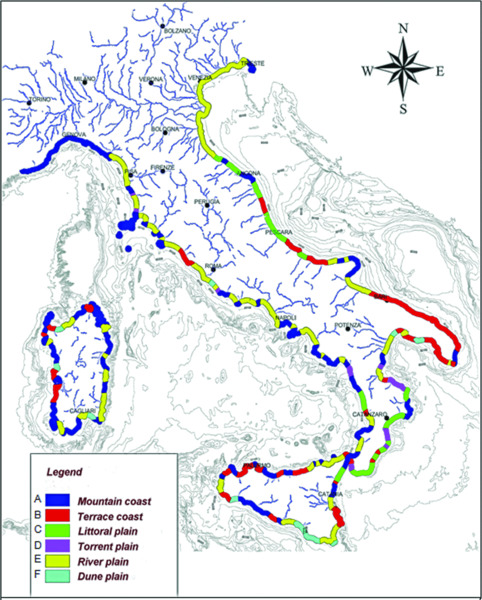

Several morphological types characterize the central Mediterranean coast. A detailed classification of such types, using a Geographic Information System (GIS) was performed by Ferretti et al. (2003) (www.santateresa. enea.it/wwwste/dincost/dincost1.html). Following the EU Water Framework Directive (ec.europa.eu/enviro nment/pubs/pdf/factsheets/water-framework-directive. pdf), Brondi et al. (2003) grouped the previous 12 coastal types of Ferretti et al. (2003) into six coastal geomorphological types (www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/icram/tipi-geomorfologica.pdf/view) (Fig. 13.3). Their relative percentages are: 47% mountain coasts, 12% terrace coasts, 4% littoral plain, 4% torrent plain, 21% river plain and 12% dune plain.

Figure 13.3 Geomorphological types of the Italian coast, modified from Brondi et al. (2003) with permission from MEDCOAST. (A) Mountain coast and high rocky coast, where cliffs or pocket beaches with coarse sediments can be present; (B) Terraces, with flat emerged portion resulting from marine abrasion of a rocky substrate or from the deposition of sediments on the rocky substrate; (C) Littoral plain made up of terrace remnants, alluvial fan and alluvial plain bordered by hill or mountain chains; (D) Torrent plain, which corresponds to large, deep valleys and high coasts; (E) River plain, where regular alluvial plains display swamps, dunes, delta and lagoons; (F) Dune plain, covered by eolian or fluvial dunes, sometimes with interdune depressions, locally swampy.

Coastal geomorpho-dynamics, erosion, accumulation

During the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene, coastal areas were strongly modified, mainly by sea-level variation and by the impact of human activity on the coastal sectors. Land use is one of the most significant morphogenetic factors of recent millennia. This is particularly evident in the Mediterranean area and in Italy, where coastal modification started in the first millennium BC (Pasquinucci et al. 2004). Such evidence supports the possibility of identifying areas for seabed prehistoric sites and landscapes. On the Italian coasts, beaches account for some 4000 km; of these, 42% are in a state of erosion (Aucelli et al. 2007). Further details are given in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Length of coasts and beaches, and percentage of coast being eroded in the Italian regions. Data after Aucelli et al. (2007).

| Italian Region | Coastal length (km) | Sandy coasts (km) | Coast in erosion (km; %) |

| Liguria | 466 | 94 | 31 (33) |

| Tuscany | 442 | 199 | 77 (39) |

| Latium | 290 | 216 | 117 (54) |

| Campania | 480 | 224 | 95 (42) |

| Calabria | 736 | 692 | 300 (43) |

| Sicily | 1623 | 1117 | 438 (39) |

| Sardinia | 1897 | 459 | 195 (42) |

| Basilicata | 56 | 38 | 28 (74) |

| Apulia | 865 | 302 | 195 (65) |

| Molise | 36 | 22 | 20 (91) |

| Abruzzi | 125 | 99 | 50 (50) |

| Marches | 172 | 144 | 78 (54) |

| Emilia Romagna | 130 | 130 | 32 (25) |

| Veneto | 140 | 140 | 25 (18) |

| Friuli-Venezia | 111 | 76 | 10 (13) |

| Italy | 7569 | 3952 | 1681 (42) |

Not only are 42% of the Italian sandy coasts undergoing erosion and coastal retreat, but also the parts of the coast classified as ‘stable’ are only prevented from retreating by coastal defense structures that, starting from 1907 with the ‘Law for the Defense of Habitats from Coastal Erosion’, completely altered the natural littoral sedimentary processes, often inducing new erosional phenomena down-current of the structures.

Around the central Mediterranean there are many coastal plains threatened by potential erosive morphogenetic processes such as relative sea-level rise and increasing frequency of extreme events. For the Italian coast there is a specific study which identified 33 coastal plains with a high probability of flooding within the next 100 years (Lambeck et al. 2011). Along the coast of the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas, the areas undergoing strong modification are the Versilian Plain, the Ombrone Delta (at present this sector is losing 10 meters of unprotected beach each year), the Orbetello lagoon, the Latium central area, the Pontina Plain and the mouths of the Volturno and Sele rivers.

Along the southern Adriatic Sea, the coastal lakes of Lesina and Varano are undergoing strong modification. Along the central and northern Adriatic Sea the greater part of the littorals from the Emilia Romagna region to the Slovenian border, including the Venice, Grado and Marano lagoons, is undergoing erosion. In Sardinia the most vulnerable areas are the wetlands of Cagliari and Oristano; many beaches in the north of the island are also eroding.

In Sicily, the natural morpho-dynamic processes of the coastal sectors of Trapani and the Catania Plain have been compromised by land use and global changes. However, increasingly, erosion is affecting all the sandy beaches of the Italian littoral, where the dune systems have been strongly compromised or definitively destroyed.

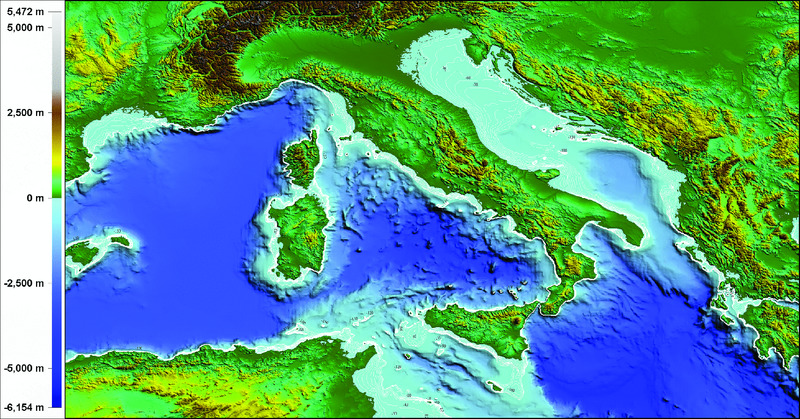

Bathymetry

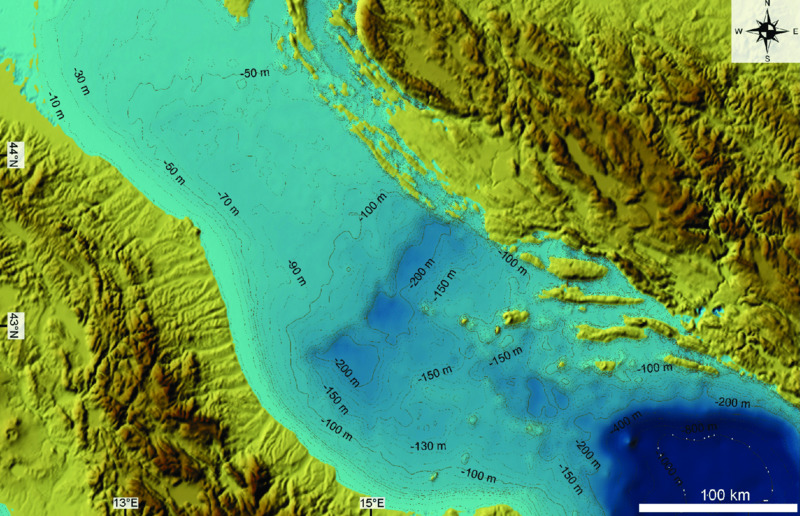

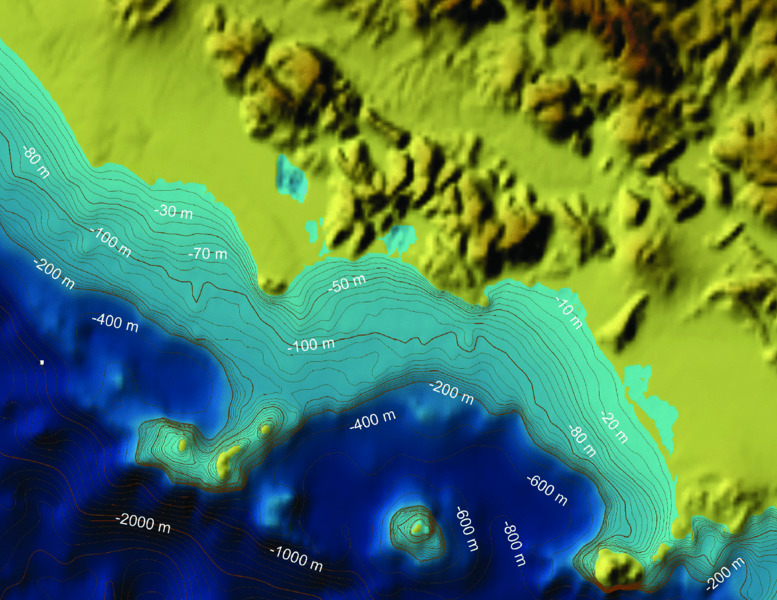

Sources of bathymetric data and digital archives are available from the Italian Navy's Italian Hydrographic Institute (1:100,000 scale everywhere, 1:50 to 1:25,000 in selected areas). Digital data are available from the General Bathymetric Database Chart of the Ocean — International Bathymetric Chart of the Mediterranean (GEBCO — IBCM) (1:250,000). Other sources of data are CARG and MAGIC (Marine Geohazards along the Italian Coasts), but these are not publicly available. The bathymetric data used for Fig. 13.4 were derived from GEBCO (www.gebco.net/data_and_products/gridded_bathymetry_data/). This database provides a bathymetric grid at 30 arcsecond intervals, with reference to geographical coordinates, latitude and longitude in the WGS84 datum. Bathymetry and topography were processed using the software Global Mapper 11 (www.globalmapper.com) in order to produce maps at different levels of detail (Fig. 13.5 and 13.6).

Figure 13.4 The bathymetric data used in this map were derived from GEBCO. Isobaths between –130 m and –10 m are well defined in the Adriatic Sea.

Figure 13.5 Close-up of Fig. 13.4 for the central Adriatic Sea.

Figure 13.6 Close-up of Fig. 13.4 for the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Vertical land movements

A variety of papers on vertical land movement along the Mediterranean coast, using archaeological and geomorphological markers, have been published during recent decades (Flemming & Webb 1986; Pirazzoli 1986; Lambeck et al. 2004; Antonioli et al. 2007; Anzidei et al. 2011a,b; 2013; Furlani et al. 2013; Pagliarulo et al. 2013). Lambeck et al. (2004), using reliable Last Interglacial and Holocene sea-level markers, assumed a nominal age of 124±5 ka and elevation, in the absence of tectonics, of 7±3 m above present sea level for this event. This elevation is higher than global estimates of this level because the Italian sites lie relatively close to the former ice margins, and the present Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5.5 shorelines in the Mediterranean may lie a few meters higher than for localities much further from the former ice margins (Potter & Lambeck 2004). These values are consistent with observations of tidal notches from Sardinia, southern Lazio, southern Campania and western Sicily, in areas believed to have been tectonically stable during the recent glacial cycles. Tidal notches are formed by solution and bioerosion of carbonatic rocks. Due to the low amplitude of tides in Italy (a mean of about 40 cm, with the exception of the northeastern Adriatic Sea), they are considered one of the best sea-level markers. Present-day tidal notches are always carved on stable carbonatic rock (with the exception of the Circeo promontory and Capri Island) by both dissolution and biological erosion. The vertical range of the notch in the central Mediterranean Sea (between 36 cm and 75 cm) seems to be related to local isostasy and tidal amplitude (Antonioli et al. 2013).

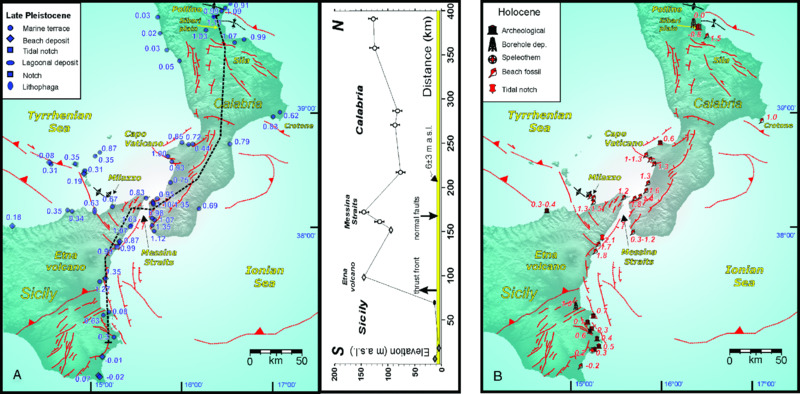

Ferranti et al. (2006) published a compilation of the MIS 5.5 highstand for 246 sites along the coasts of Italy, defining areas tectonically stable and areas with active vertical displacement since the Late Pleistocene (an extensive database of the latter is plotted in Table 13.1). Antonioli et al. (2009) and Ferranti et al. (2010) report more data on the altitude of MIS 5.5 in Tuscany and the northeastern Adriatic Sea and in other sites for the Holocene (Figs. 13.7 & 13.8).

Figure 13.7 Rates of vertical movement along the Italian coastlines for MIS 5.5 (125 ka) and the Holocene. Modified from Lambeck et al. 2011.

Figure 13.8 Vertical displacement rates (mm/year) computed from the elevation of (A) Late Pleistocene and (B) Holocene markers plotted with main structures on a DEM of Calabria and eastern Sicily. Modified from Ferranti et al. 2010.

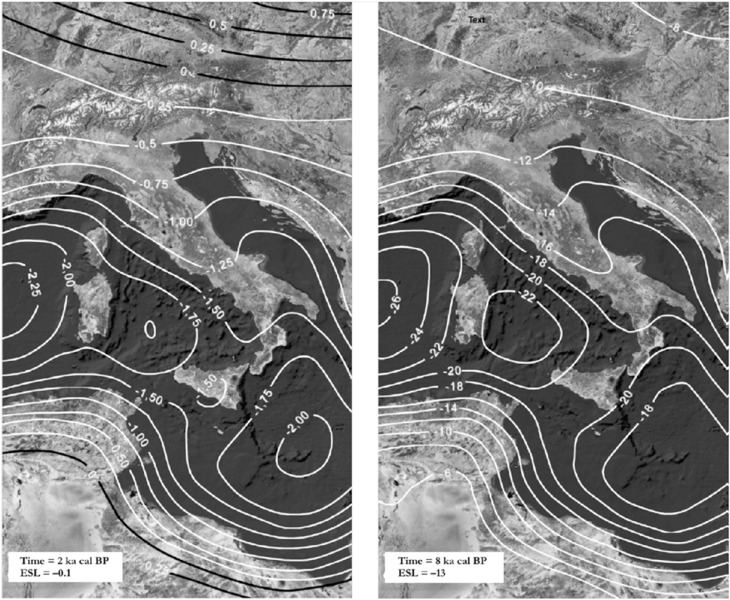

To better understand relative sea-level changes during the Holocene, we have to consider that its variations are the sum of eustatic, glacio-hydro-isostatic and tectonic factors. The first is global and time dependent, while the other two also vary according to location. The glacio-hydro-isostatic factor along the central Mediterranean Sea coast was recently modeled and compared with field data at sites not affected by significant tectonic movements (Lambeck et al. 2004 (Fig. 13.9); 2011; Antonioli et al. 2007). The authors defined as tectonic factors all movements that are not eustatic or isostatic. Lambeck et al. (2011) electronic supplementary material provides: 1) coordinates, time (ka cal BP) and predicted altitude (m) on 40 coastal sites dating back to 20 ka cal BP; 2) the database of the Holocene observational data; and 3) the database of Last Interglacial (125 ka) observational data. Tectonic uplift mainly occurs in the foredeep (Adriatic and Ionian coasts), as well as in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea. In contrast, subsidence occurs on many Italian coastal sites, strongly enhanced by sediment compaction and draining of water and organic-rich soils for land reclamation. Last Interglacial deposits do not outcrop along the Slovenian and Croatian coasts until Montenegro, and on the evidence of a submerged tidal notch (dated to the Early Holocene, Furlani et al. 2011) that was found in all carbonate cliffs, it is supposed that this coastal area is still subsiding.

Figure 13.9 Glacio-hydro-isostatic adjustment variations of sea level for the central Mediterranean for two distinct epochs (2 ka cal BP and 8 ka cal BP). The white contour refers to sea-level change. The ice-volume-equivalent sea level (ESL) values are given in meters (–0.1 m and –13 m at 2 ka cal BP and 8 ka cal BP respectively). Modified from Lambeck et al. (2004).

The well-known subsidence in the Venice area (north Adriatic Sea) occurred with a rate of ~2.3 mm/year to ~2.4 mm/year in the last 150 years (Camuffo & Sturaro 2004). The contribution from mean sea-level rise is 1.1 mm/year, while 0.3 mm/year is due to natural subsidence and 0.9 mm/year to anthropogenic subsidence (Carbognin et al. 2004). In the Emilia-Romagna region during recent decades the subsidence reached a peak of 70 mm/year in the Po Delta (Carminati & Martinelli 2002), with a subsidence due to land use of 10 mm/year to 30 mm/year (Bonsignore & Vicari 2000).

Along the Ligurian coast, in the Versilian Plain, several meters of Late Pleistocene and Holocene sediments indicate 1 mm/year of subsidence during the Pliocene–Quaternary (Tongiorgi 1978). Land reclamations during the last century increased subsidence rates along this plain (Mazzanti 1995; Nisi et al. 2003) and recent data show subsidence at rates of 2 mm/year for the Versilian Plain during recent decades, while in Lake Massaciuccoli these rates reached 7 mm/year for the same period (Palla et al. 1976; Auterio et al. 1978; Galletti Fancelli 1978; Antonioli et al. 2000; Nisi et al. 2003).

Volcanoes

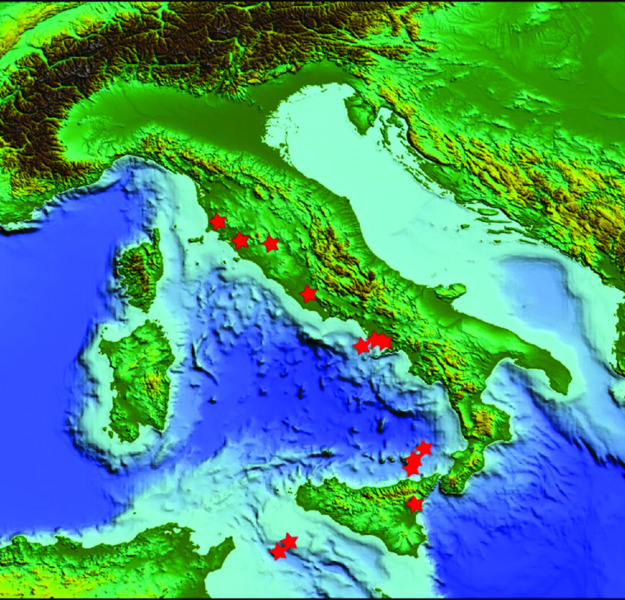

In the central Mediterranean region, several volcanoes are present with ages and activity spans from a few millions of years ago to the present (www.volcano.si.edu and www.ingv.it) (Fig. 13.10). Their character and genesis vary according to the complex geodynamics of the Mediterranean region; a large number of volcanoes are located along the eastern and southern Tyrrhenian Margin and in the Sicily Strait. Mount Etna lies on the Sicilian coast of the Ionian Sea. Besides these, there are additional large volcanoes, such as Marsili and Palinuro, rising from the sea floor of the southern Tyrrhenian Sea.

Figure 13.10 Map of Italian volcanoes (marked with red stars) which have been active since the Holocene. Modified from www.volcano.si.edu/ and www.ingv.it. Volcano age generally decreases from north to south and some, such as Stromboli in the Aeolian Islands and Etna in Sicily, are still active.

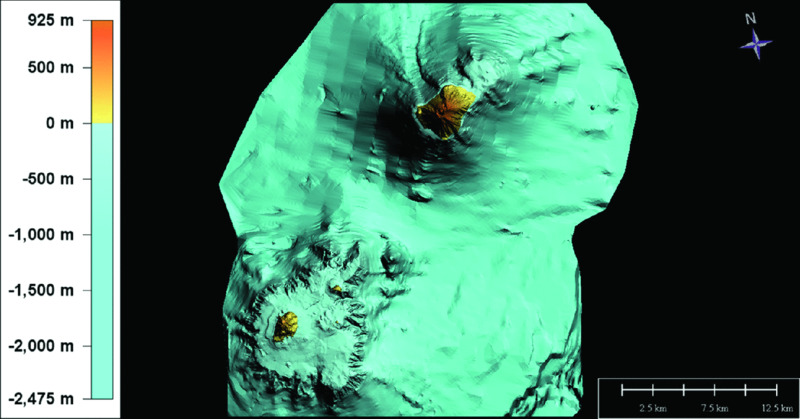

During activity, these volcanoes underwent significant vertical surface movements (Esposito et al. 2009); on coasts and islands these caused very fast relative sea-level changes. Coastal archaeological remains, mainly Roman, in a few cases prompted contemporary written accounts of such relative sea level (RSL) changes due to vertical land movements, well before the instrumental era. Particularly significant are the Phlegrean Fields (Naples) with the Temple of Serapis in Pozzuoli, the submerged Roman town of Baia, and the small Roman harbor of Basiluzzo in the Aeolian Islands (Tallarico et al. 2003; Anzidei et al. 2005b). As an example, in this latter area, a very high resolution DEM, which includes topography and bathymetry, is available (Fabris et al. 2010; Fig. 13.11). Given the continuous subsidence of nearby Panarea and the presence of prehistoric settlements on the island, it is possible that archaeological remains could also exist, submerged by up to tens of meters in this area as in other islands of the Aeolian archipelago, as in the case of Lipari (Roman age remains at –12.7 m; see www.regione.sicilia.it/beniculturali/archeologiasottomarina/).

Figure 13.11 DTM of the Panarea and Stromboli volcanoes. The DTMs are at 2.5-m and 5-m grid size at Panarea and Stromboli respectively. Local bathymetry in the area surrounding the Panarea archipelago (the islets of Panarelli, Dattilo, Lisca Nera, Bottaro, and Lisca Bianca) is at 0.5-m grid size, while regional bathymetry is at 10-m grid size.

Pleistocene and Holocene Sediment Thickness on the Continental Shelf

The continental shelves are shallow-water (<150 m) flat areas, at present usually characterized by silty-muddy sedimentation. The Italian shelves belong to the temperate climate zone and are wave-dominated, because of the narrow tidal range (microtidal regime) and the medium-regime of marine currents with speed of tens of cm/sec on average (IIM 1982). The shelves are mainly fed by rivers, so the deposits are usually siliciclastic, with subordinate extra-tropical carbonate intrabasinal deposits. The latter are characterized by temperate assemblages and are located on under-fed areas such as the very wide shelves (Tuscan, Adriatic, southern Sicily) or insular shelves (Tuscan, Pontine, Campanian, Aeolian, Egadi and Tremiti archipelagos among others).

Given their relatively young geological age, Italian shelves are extremely narrow and steep if compared with older margins. Present-day morphology is mainly the result of Plio-Pleistocene basin-ward margin progradation episodes, which partially or completely covered the uneven pre-existing substrate (Tortora et al. 2001). Geodynamics controls the overall morphology of the shelves, with the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic shelves being the two end-members; the former lies on the margin of a basin undergoing oceanization and is thus affected by extensional tectonics, while the latter lies on an epicontinental sea which is the superficial expression of the foredeep basin of the Apennines to the west, and of the Dinarides to the east, and is thus affected by compressive tectonics and loading subsidence, both migrating over time. During the Pleistocene, shelf deposition was mainly controlled by high-frequency (fourth- and fifth-order, ca. 100 kyr and 20 kyr) depositional cycles that occur as multi-stacks of shelf deposits (e.g., Chiocci 2000; Ridente et al. 2009) similar to those observed in other Mediterranean areas (e.g. Somoza et al. 1997; Tesson et al. 2000). In detail, the stratigraphic architecture and physiography of the shelves varies considerably over short lateral distances in relation to the complex geology and tectonics of Italy (Martorelli et al. 2014). Some Italian coasts are characterized by uplift (the southern Tyrrhenian, southern Adriatic and Ionian margins); others are relatively stable (most of the eastern Tyrrhenian, from Tuscany to northern Calabria) or subsiding (northern Adriatic) (Ferranti et al. 2006).

The sediment supply and dispersal vary in the different areas according to inland climate and hydrogeological setting. Thus the shelves facing onto northern-central Italy are commonly fed by large rivers (the Po, Tiber, Arno, Ombrone, Volturno, and Sele being the principal ones), while those in southern Italy are fed by small rivers with a torrential regime or ephemeral streams. The complex interplay in time and space between these factors controlled and controls the character of depositional systems and favors or hinders the formation and preservation of lowstand, transgressive and highstand deposits on the shelf. On the whole, the complete succession of Late Quaternary systems rarely occurs. For the last depositional sequence, the falling-stage and lowstand systems are mainly confined to the very outer shelf and upper continental slope; transgressive-systems are often absent or represented by a thin lag of coarse, bioclastic sediment, while the highstand systems are usually (but not always) well developed, producing a muddy wedge that covers the inner-middle shelf and thins towards the shelf break (Martorelli et al. 2014).

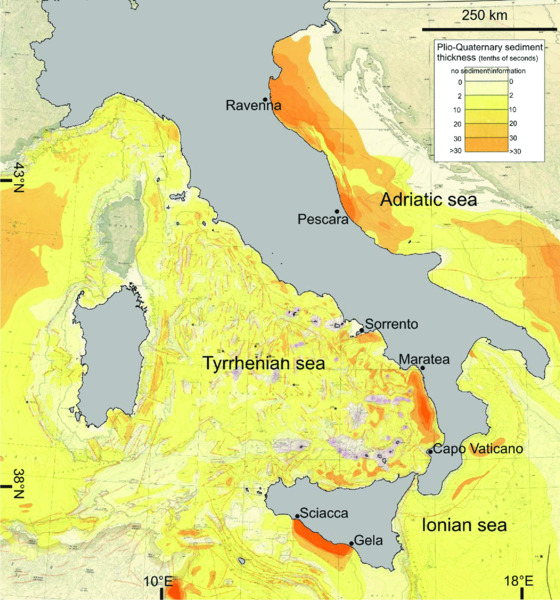

As far as source data is concerned, the Plio-Quaternary sediment thickness (Fig. 13.12) in Italy and in surrounding seas can be derived from the structural model of Italy at a scale of 1:500,000 published from Bigi et al. (1990) or from IBCM for all the Mediterranean basin at 1:1,000,000 scale (www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/ibcm/ibcmsedt.html). The maximum thickness of Plio-Quaternary sediments is found in the foredeep areas of the Po Plain, the Adriatic Sea and southwest Sicily, with values up to 7 km. Other main depocenters are located in the Tyrrhenian intraslope basins off Campania, Calabria and Sicily.

Figure 13.12 Plio-Quaternary sediment thickness around the Italian coasts (data from IBCM charts, adapted with permission), displaying three main depocenters (see text for detail).

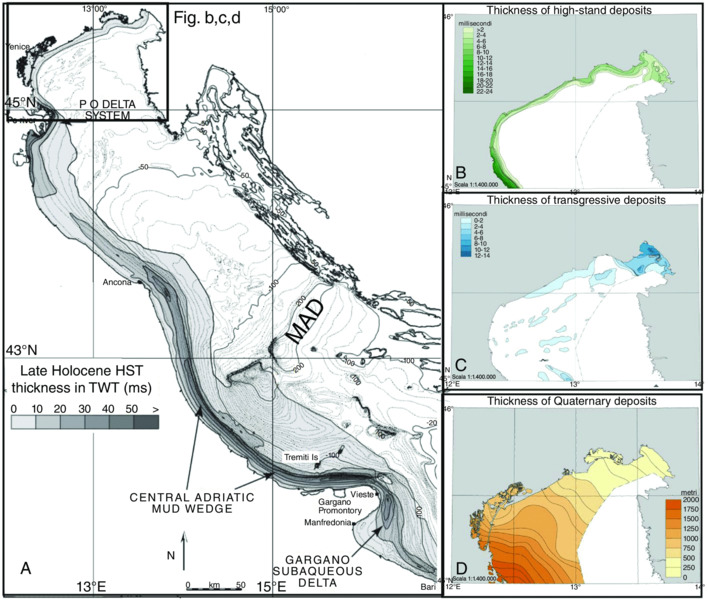

As far as Pleistocene and Holocene sediment thickness is concerned, comprehensive maps do not exist, apart from the Adriatic Sea. Here, a series of thematic maps at a scale of 1:1,000,000 show the thickness of the postglacial deposits as well as the isochrones of the Quaternary sediment (Fig. 13.13; www.isprambiente.gov.it/Media/carg/index_marine.html). These latter reach values >1.4 s twt (two-way travel time) (more than 1000 m) in the northern and central Adriatic, while they rapidly decrease towards the Golfo di Trieste and south of the Gargano promontory. The lowstand deposits show a main depocenter of about 250 m immediately north of the Mid Adriatic Depression (MAD) (Fig. 13.13), where it records 150 km of shelf progradation due to the Po Delta and prodelta systems, while they thin to a minimum of a few meters on the southern flank of the MAD (Ridente & Trincardi 2005). The thickness of transgressive deposits increases from the northern Adriatic towards the south, reaching a maximum value of 90 m offshore of Pescara.

Figure 13.13 (A) Thickness and depocenter distribution of the Late Holocene highstand mud-wedge in the Adriatic Sea. Modified from Cattaneo et al. (2003) and reproduced with permission from Elsevier; on the right (B, C, D), thickness of highstand, transgressive and Quaternary deposits. Data from 1:50.000 geological map of Italian sea ‘Venezia sheet’ (www.isprambiente.gov.it/Media/carg/index_marine.html). Reproduced with permission from ISPRA.

The highstand deposits show three main depocenters located: 1) offshore of the Po river mouth; 2) elongated parallel to the coast between Ancona and Vieste, and 3) south-east of the Gargano promontory, where the depocenter has been interpreted as a subaqueous delta, prograding far away from and not directly connected to any river source (Cattaneo et al. 2003).

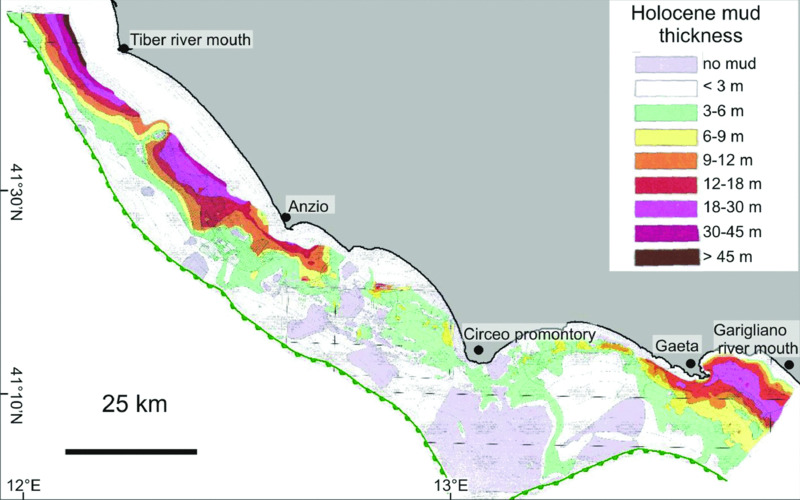

In the case of the Tyrrhenian continental shelves, the reference sources are mainly related to the results of 1) scientific projects, such as ‘Oceanografia e Fondi Marini’ (Sardinia, Liguria, Tuscany, Latium and Calabria continental shelves; Aiello et al. 1978; Arca et al. 1979; Corradi et al. 1984; Bartolini et al. 1986; Chiocci 1994), ‘Mare del Lazio’ (Fig. 13.14) (Latium continental shelf; Chiocci & La Monica 1996), ‘Geologia dei margini continentali’ (northwestern part of Sicilian shelf; Agate & Lucido 1995) and the EU INTERREG project ‘Beachmed’ (Liguria shelf; www.beachmed.it); 2) technical reports describing prospecting for relict sand on the continental shelf to find sources for beach replenishment (part of the Tuscan continental shelf, unpublished data); and 3) the explanatory notes for the 1:50,000 national geological sheets in the framework of the CARG project (e.g. Foce del Fiume Sele or Salerno sheet for the Campanian shelf, www.isprambiente.gov.it).

Figure 13.14 Map of Holocene sediment thickness in the southern Latium shelf. Modified from Chiocci and La Monica (1996) with permission; note the main depocenters are located offshore of the main rivers draining this sector (the Tiber to the north and the Garigliano to the south).

For the Tyrrhenian shelves, postglacial deposits usually have depocenters (value >40–50 m) located in a close relationship with river mouths, or slightly displaced where an interaction between the river plume and the geostrophic currents is present, such as with the Tiber (Chiocci 1994). Transgressive deposits (5–10 m) are present locally and their depocenters are found in front of small river mouths and in protected topographic lows, but mainly along the narrow and steep shelf such as in Calabria (Chiocci et al. 1989; Tortora et al. 2001; Martorelli et al. 2010). These deposits can be organized in elongated bodies parallel to the coast or in linear depocenters normal to the coast, representing the sediment infilling of inner shelf paleoriver incision. Highstand deposits commonly have depocenters in front of the main river mouth, where they can reach a thickness of 30 m to 40 m; these depositional bodies rapidly thin towards the shelf edge (Fig. 13.14).

Post-LGM Climate, Sea Level, and Paleoshorelines

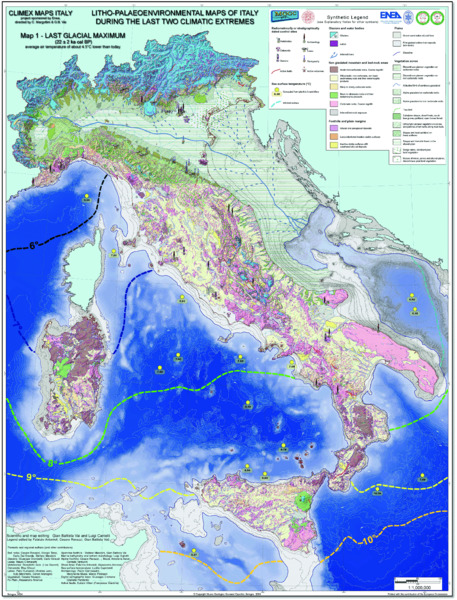

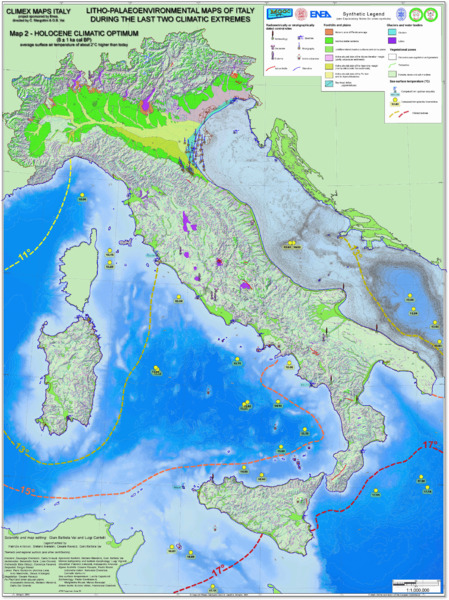

General climatic conditions and change since LGM. Mediterranean Sea Surface Temperature (SST) patterns

The Mediterranean Sea is a semi-enclosed basin with the Gibraltar Strait providing the only connection to the open ocean. The hydrodynamics of the basin are controlled by the North Atlantic water inflow, wind regime, and climate of the surrounding lands (Pinardi & Masetti 2000). Climate variability is related to the geographic position of the region located on the transition between high- and low-latitude influences. Paleoceanographic research demonstrates that during the Last Glacial interval, the Mediterranean Sea became a sensitive region, responding to North Atlantic rapid climatic changes, including Dansgaard-Oeschger (D-O) and Heinrich events (Rohling et al. 1998; Cacho et al. 1999; Sangiorgi et al. 2003; Sierro et al. 2005). In addition, it seems that the African monsoon extended at certain times over the Mediterranean basin and has been responsible for an increase in precipitation leading to increased freshwater input, reduced deepwater ventilation and deposition of sapropel layers (Tzedakis 2007). Various efforts have been made to estimate Quaternary SSTs in the Mediterranean Sea but most of these studies have considered single-core rather than multi-core analysis on a basin-wide scale (Kallel et al. 1997; Sangiorgi et al. 2003; Geraga et al. 2005; Di Donato et al. 2008). Additional problems are related to the different adopted methods (e.g. size fraction of faunal counting, use of different proxies) and to the age quality control (robust age model and high temporal resolution), which prevents us from performing correlations between different cores in the same time slice. The principal attempts across the entire basin are reported in Table 13.2 and the results are illustrated in Figs. 13.15 and 13.16. They are related to well-constrained time intervals: the LGM and the Holocene Climatic Optimum.

Table 13.2 Principal reconstruction of SST performed in the central Mediterranean Sea.

| Work | Time interval | Proxies | Web site/map |

| Molina-Cruz & Thiede (1978) | LGM (18 ka BP) | planktonic foraminifera census counts | |

| Thunell (1979) | LGM (18 ka BP) eastern Mediterranean sea | planktonic foraminifera census counts | |

| CLIMAP 1981: Climate Long-range Investigation, Mapping, and Prediction | LGM (18 ka BP) defined as maximum extent of continental glaciers | planktonic foraminifera census counts | www.ncdc.noaa.gov/ paleo/climap.html |

| Antonioli et al. (2004) | LGM (22 ±2 ka cal BP) and Holocene Climatic Optimum (8 ±1 ka cal BP). | Oxygen isotopic composition of calcareous planktonic foraminifera | CLIMEX MAP 2004, see Figs. 13.15 and 13.16 |

| Hayes et al. (2005) | LGM (23–19 ka cal BP) | planktonic foraminifera census counts | |

| MARGO working group (2009): Multiproxy Approach for the Reconstruction of the Glacial Ocean surface | LGM interval (23–19 ka cal BP) | transfer functions (based on planktonic foraminifera, diatom, dinoflagellate cyst and radiolarian abundances) and geochemical palaeothermometers (alkenones and planktonic foraminifera Mg/Ca) | www.geo.uni-bremen.de/~apau/margo/margo_EN.html |

Figure 13.15 Mean April–May sea-surface temperatures (SST) during the LGM at 22 ka cal BP. Figures are obtained by solving the paleotemperature equation of Shackleton (1974) (see Capotondi (2004) for details), using isotopic analyses of planktonic Foraminifera shells from selected marine sediment cores with well-constrained dates. Oxygen isotopic composition of water in the different basins of the Mediterranean Sea at time zero is from Pierre (1999). The figures indicate a cooling of approximately 7±2°C compared to the present day.

Figure 13.16 Mean April–May sea-surface temperatures (SST) during the Holocene Climatic Optimum at 8 ka cal BP. Figures are obtained by the same methods as for those presented in Fig. 13.15.

Evolution of sea level and coastline since the LGM

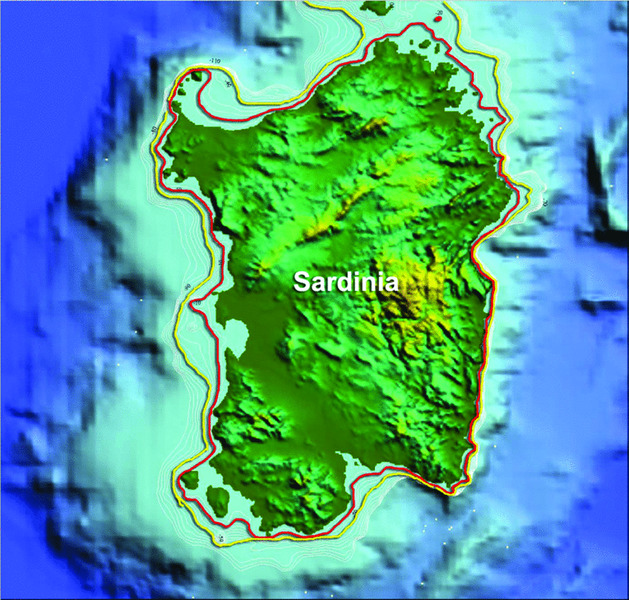

Holocene relative sea-level change along the central Mediterranean coast is the sum of eustatic, glacio-hydro-isostatic, and tectonic factors. As pointed out above, the first is global and time dependent, while the latter two also vary with location. A large collection of Holocene data for Italy, using different markers well connected with sea level, was published by Lambeck et al. (2004). This large observational data set was compared with the predicted curves, leading to quantitative estimates of vertical tectonic movements (if present), identification of tectonically stable coastal areas and paleogeographic reconstructions for the central Mediterranean Sea at different epochs. These predictions were then extended to the whole Mediterranean (Lambeck & Purcell 2005). A complete review of the Holocene data, including the files of the predicted sea-level data for 40 Italian sites, has recently been published (see supplementary material in Lambeck et al. 2011). Significant differences can be observed in stable coastal areas if different sites are considered: as an example, sea level at 10 ka cal BP varies along the Italian coasts between –48 m and –35 m, whereas at about 8 ka cal BP it ranges between –19 m and –11 m. The Mesolithic and Neolithic paleoshorelines predicted from Lambeck et al. (2011) for Sardinia and the central Mediterranean are drawn in Figs. 13.17 and 13.18, and other examples using the same method and model are published for the islands of Pianosa and Elba (Tuscany) in Antonioli et al. (2011). An example of temporal and spatial evolution of land/sea extension and paleoshoreline evolution since the LGM is reported in Furlani et al. (2013) for the area between southern Sicily and northern Africa.

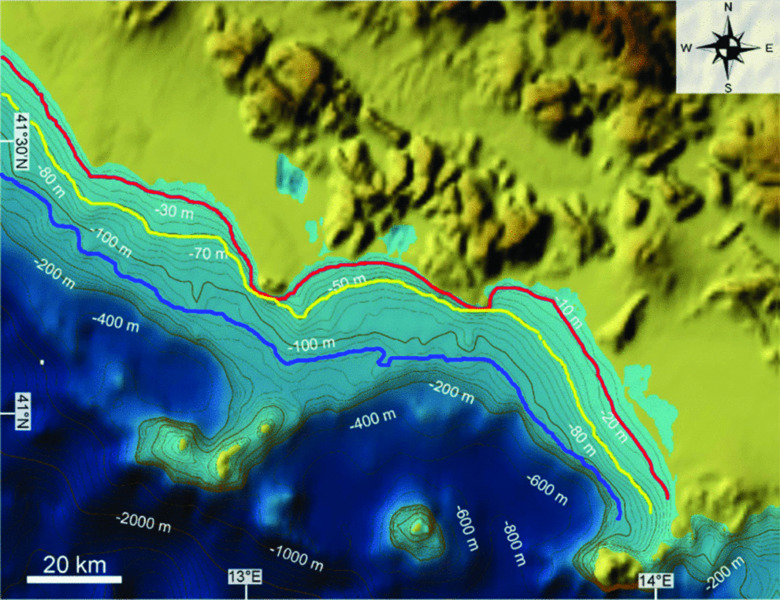

Figure 13.17 Sardinia, Tyrrhenian Sea. DEM from GEBCO with paleoshorelines predicted from Lambeck et al. (2011) model. In red, the Neolithic coast (8 ka cal BP), and in yellow, the Mesolithic coast (11 ka cal BP). The coastal tectonic component in Sardinia is about zero (Ferranti et al. 2010).

Figure 13.18 Coast of southern Latium, Tyrrhenian Sea. DEM from GEBCO with paleoshorelines predicted from Lambeck et al. (2011) model. In red, the Neolithic coast (8 ka cal BP), in yellow, the Mesolithic coast (11 ka cal BP), and in blue, the LGM (22 ka cal BP). The tectonic component in this area is about zero. Ferranti et al. (2010).

Central Mediterranean wave climate

The survival of prehistoric sites in shallow seas depends partly upon the prevailing local wave climate. Enclosed between the storm belt of northern Europe and the tropical area of northern Africa, the Mediterranean Sea has a relatively mild climate on average, but substantial storms are possible, usually in the six-month winter (Cavaleri et al. 1991). The maximum measured significant wave height (Hs) can reach 10 m, but model estimates for some non-documented storms suggest larger values. For instance, even in the relatively small Adriatic Sea, an oceanographic tower, located 15 km offshore in 16 m water depth, suffered heavy damage up to 9 m above sea level (Cavaleri 2000).

In particular, the Mediterranean winter climate is dominated by the eastward movement of storms originating over the Atlantic and impinging upon the western European coasts (Giorgi & Lionello 2008). Furthermore, Mediterranean storms can be produced within the region in cyclogenetic areas such as the lee of the Alps, the Golfe du Lion and the Golfo di Genova (Lionello et al. 2006). In contrast, high pressure and descending air motions dominate over the Mediterranean region during the summer, leading to dry conditions, particularly over its southern part. The summer Mediterranean climate variability has been found to be connected with both the Asian and African monsoons (Alpert et al. 2006) and with strong geopotential blocking anomalies over central Europe (Trigo et al. 2006).

In addition to planetary-scale processes and teleconnections, the meteo-marine conditions of the Mediterranean area are strongly affected by local processes induced by the complex topography, coastline and vegetation cover of the region, which modulate the regional climate signal at small spatial scales (e.g. Lionello et al. 2006). The complex orography has, indeed, the effect of distorting large synoptic structures and produces local winds of sustained speed (for example the bora, mistral–tramontana, scirocco and libeccio, and the Etesian winds) which, over some areas of the region, blow up at almost any time of the year. Such wind regimes strongly determine wave-field dynamics in the sub-basins of the Mediterranean Sea. In the case of the central Mediterranean Sea, a major effort has been carried out recently to collect available information from buoys in a comprehensive atlas (Franco et al. 2004; www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/servizi-per-lambiente/stato-delle-coste/atlante-delle-coste). The latter gives an accurate description of the wave climate on sites but with poor extension and time resolution. A wind and wave atlas, MEDATLAS (MedatlasGroup 2004), of the entire Mediterranean Sea has been published by the WEAO's (Western European Armaments Organisation) Research Cell; this atlas represents the largest historical database of hydrographic measurements available for the Mediterranean.

Because of the interaction of processes at a wide range of spatial and temporal scales, even relatively minor modifications of the general circulation can lead to substantial changes in the Mediterranean climate and consequently in the meteo-marine regime. This makes the Mediterranean a region potentially vulnerable to climatic changes (e.g. Ulbrich et al. 2006). The Mediterranean region has, in fact, shown large climate shifts in the past (Luterbacher et al. 2006) and it has been identified as one of the most prominent hotspots in future climate change projections (Giorgi 2006). The distribution and intensity of wind fields over the Mediterranean Sea are expected to change during the twenty-first century planning horizon, as a result of anthropogenic climate change due to the enhanced greenhouse effect (IPCC 2007). One of the most comprehensive reviews of climate change projections over the Mediterranean region is reported by Ulbrich et al. (2006), based on a limited number of global and regional model simulations performed throughout the early 2000s. A number of papers have also reported regional climate-change simulations over Europe, including totally or partially the Mediterranean region (e.g. Giorgi & Lionello 2008). A robust and consistent picture of climate change over the Mediterranean emerges, consisting of a pronounced decrease in precipitation, especially in the warm season. A pronounced warming is also projected, with maximum temperatures in the summer season. Interannual variability is projected to mostly increase, especially in summer, which, together with the mean warming, would lead to a greater occurrence of extremely high temperature events.

Submerged Terrestrial Landforms and Ecology

Submerged river valleys

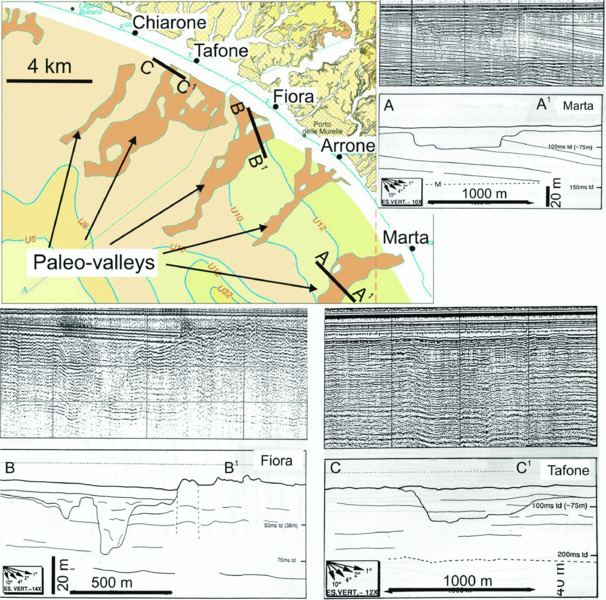

Submerged river valleys represent the prolongation of river drainage systems onto the continental shelf when it was sub-aerially exposed during the fall and successive rise of sea level before reaching its present-day highstand sea level. Paleovalleys are recognized in high-resolution seismic profiles through the discontinuity and different acoustic response with respect to the surrounding areas (Fig. 13.19), and the isopachs of transgressive deposits which often show local depocenters. An impressive example of a paleoriver drainage system has been found in the northern part of the Latium shelf between Ansedonia and Civitavecchia (see Chiocci & La Monica 1996; Tortora et al. 2001). These paleovalleys can be tracked from the coast down to 70 m to 80 m below sea level in alignment with the mouths of what are now very small rivers on the present coast, such as the Marta, Arrone, Fiora and Tafone (Fig. 13.19). These paleovalleys are represented by erosive features characterized by a width of a few thousand meters, a channel depth of a few tens of meters and a variable shape, ranging from V- to U-shaped cross-sections (Fig. 13.19). These features affect the erosive unconformity related to the last lowstand of sea level (about 20 ka) and the paleovalleys are filled with deposits characterized by low transparency and short-term lateral variation of seismic attributes. The infilling material is often represented by fluvial deposits at the base of the paleovalleys overlain by lagoonal and then marine deposits. There is a poor correlation between the drainage system of present-day rivers and the width of paleovalleys, suggesting that paleoriver drainage behavior and runoff was very different from the present day during lowstand conditions. Similar features have also been found in the Golfo di Salerno (www.isprambiente.gov.it/Media/carg/note_illustrative/467_Salerno.pdf), along the Liguria shelf in front of the Entella river mouth (Corradi et al. 1984) and in the southern Latium shelf (Chiocci & La Monica 1996). Here, submerged paleovalleys were recognized between the Circeo promontory and Gaeta, corresponding to present-day inactive small rivers (Fig. 13.14), also highlighting the difference between the lowstand and present-day drainage systems. Finally, it is noteworthy that there is a lack of seismic evidence in paleovalleys on the outer shelf corresponding to the larger rivers such as the Tiber or Po, where the progradation of these systems seems to continue undisturbed.

Figure 13.19 Map of a reconstructed paleovalley on the northern Latium shelf. Data from the 1:50.000 geological map of ‘Montalto di Castro’ (www.isprambiente.gov.it/MEDIA/ carg/lazio.html), with the location of high-resolution seismic profiles crossing paleovalleys of Marta (A–A1), Fiora (B–B1) and Tafone (C–C1) rivers. Reproduced with permission.

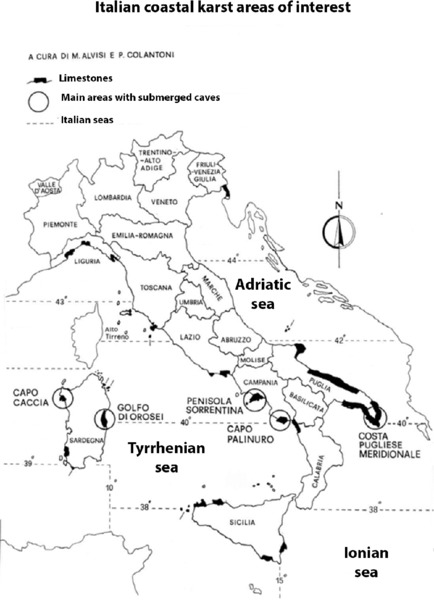

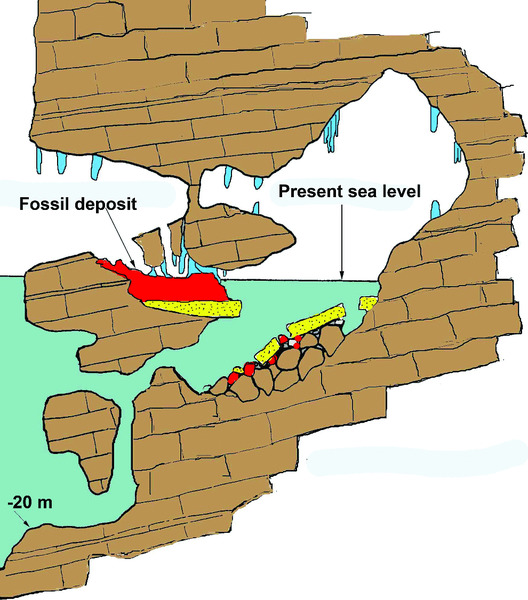

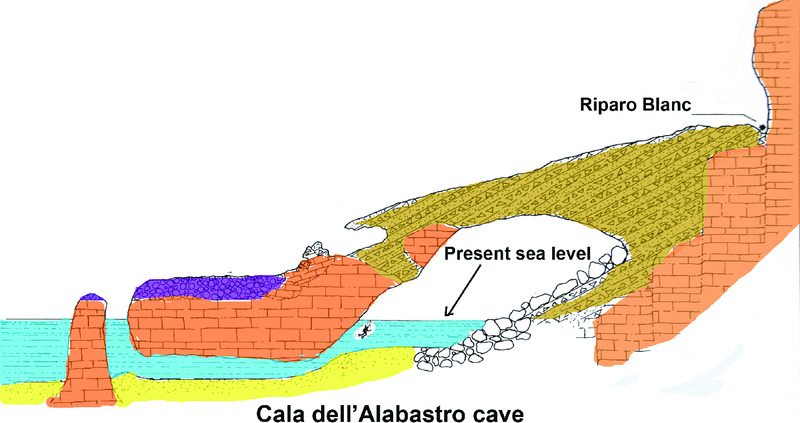

Submerged marine caves

On the limestone rocks outcropping along the Italian coastline (Fig. 13.20) there are well-developed karstic systems which were active during the sea-level lowstand in glacial periods. Thousands of submerged caves are known but they have only been partially studied. Two important books have been published describing in detail hundreds of sea-flooded caves, with sketches, sections and scientific (geological, biological and ecological) information (Alvisi et al. 1994 and Cicogna et al. 2003). Figs. 13.21 and 13.22 illustrate some flooded caves in Sardinia (Grotta dei Cervi, Fig. 13.21) and Riparo Blanc (central Tyrrhenian Sea), 100 km south of Rome (Fig. 13.22). The submerged caves are of interest for future research, including possible prehistoric occupation.

Figure 13.20 Modified from Alvisi et al. (1994) and reproduced with permission from Istituto Italiano di Speleologia; black represents coastal areas of karstic limestone, where submerged caves are located.

Figure 13.21 Alghero, Sardinia. A partially submerged cave containing fossil deer (Megaceros caziotii). Today this cave is inaccessible due to sheer cliffs above and below the cave, descending to a depth of 40 m. Modified from Antonioli and Muccedda (1997).

Figure 13.22 The Cala dell'Alabastro cave (San Felice Circeo, Italy, black line). The arrow indicates a Mesolithic site (Riparo Blanc) containing the shell mounds of limpets (Patella ferruginea) dated by radiocarbon; the submerged cave is of interest for future research. Modified from Antonioli and Ferranti (1994).

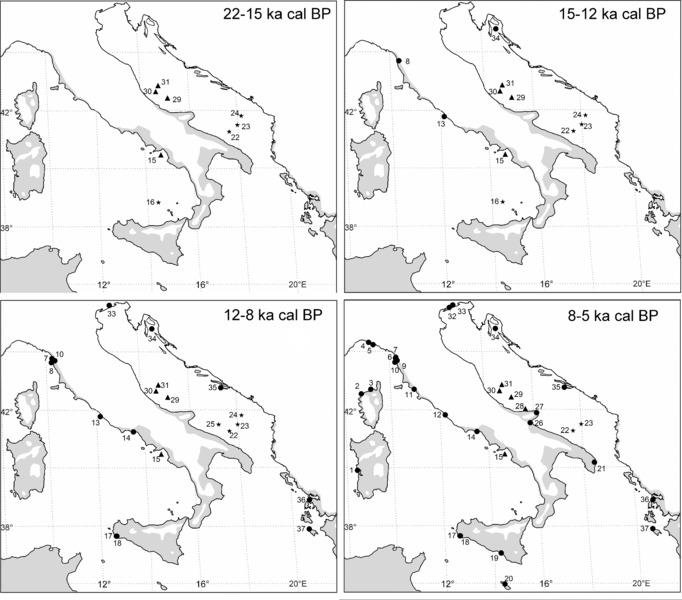

Regional paleoclimate and vegetation indicators

A number of radiocarbon-dated pollen records from coastal areas and marine cores provide a reconstruction of the history of the coastal vegetation in the central Mediterranean regions from 22 ka cal BP to 5 ka cal BP (Fig. 13.23). Between 22 ka cal BP and 15 ka cal BP, a few pollen diagrams from marine cores from both the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic seas are available, whilst records from coastal sites are missing. The provenance of pollen grains extracted from marine sediments is not easily established, as the pollen grains of both coastal and inland vegetation may be transported into the sea by wind and rivers. In addition, marine records may be biased by selective pollen accumulation and preservation, resulting in an over-representation of the saccate pollen of conifers and in reduced floristic richness. The distance from the coast, and the water depth of the coring sites, clearly affect the vegetation reconstruction. The deep-sea records of the Adriatic Sea (–300 m; Fig. 13.23) mostly represent the development of regional vegetation, as indicated by the high amounts of pollen from montane vegetation, corresponding to pollen inputs from far inland. In particular, both core KET 8216 and MD 90-917 (Rossignol-Strick et al. 1992; Combourieu-Nebout et al. 1998) show significant percentages of Picea, most probably from the mountain ranges of the Balkan Peninsula. The vegetational landscape of the Italian coasts was herb-dominated, as also indicated by the coeval lacustrine records from inland regions (Follieri et al. 1998; Allen et al. 2000). Excluding Pinus, the most important trees were deciduous Quercus, which could populate areas both at middle elevations and along the coasts. By contrast, modest frequencies of evergreen Quercus were probably from low elevation sites. Marine cores from above 300 m depth in the Adriatic Sea, which were relatively close to the ancient coast, show high percentages of Juniperus, together with abundant steppe and grassland elements, while deciduous trees were less abundant than in the coeval deep-sea records (Lowe et al. 1996).

Figure 13.23 Location of coastal and marine pollen records in Italy for the time interval 22 ka cal BP to 5 ka cal BP (dot = land site; triangle = marine site above 300 m; star = marine site below 300 m). The gray area represents the modern distribution of evergreen vegetation. (1) Mistras: Di Rita and Melis (2013); (2) Le Fango: Reille (1992); (3) Saleccia: Reille (1992); (4) Rapallo: Bellini et al. (2009); (5) Sestri Levante: Bellini et al. (2009); (6) Lago di Massaciuccoli: Colombaroli et al. (2007); (7) Versilian Plain: Bellini et al. (2009); (8) Arno S1: Amorosi et al. (2009); (9) Pisa Plain: Bellini et al. (2009); (10) Arno M1: Aguzzi et al. (2007); (11) Ombrone: Biserni and van Geel (2005); (12) Lingua d'Oca–Interporto: Di Rita et al. (2010); (13) Pesce Luna: Milli et al. (2013); (14) Vendicio: Aiello et al. (2007); (15) C106: Russo Ermolli and di Pasquale (2002); Di Rita and Magri (2009); (16) KET 8003: Rossignol-Strick and Planchais (1989); (17) Lago Preola: Magny et al. (2011); (18) Gorgo Basso: Tinner et al. (2009); (19) Biviere di Gela: Noti et al. (2009); (20) Burmarrad: Djamali et al. (2013); (21) Lago Alimini Piccolo: Di Rita and Magri (2009); (22) MD 90-917: Combourieu-Nebout et al. (1998); (23) KET 8216: Rossignol-Strick et al. (1992); (24) IN9: Zonneveld (1996); (25) SA03-1: Favaretto et al. (2008); (26) Lago Salso: Di Rita et al. (2011); Di Rita (2013); (27) Lago Battaglia: Caroli and Caldara (2007); Caldara et al. (2008); (28) RF93-30: Oldfield et al. (2003); (29) RF93-77: Lowe et al. (1996); (30) PAL94-8: Lowe et al. (1996); (31) CM92-43: Asioli et al. (2001); (32) Ca’ Fornera: Miola et al. (2010); (33) Concordia Sagittaria: Miola et al. (2010); (34) Lake Vrana: Schmidt et al. (2000); (35) Malo Jezero: Jahns and van den Bogaard (1998); (36) Lake Voulkaria: Jahns (2005); (37) Alikes Lagoon: Avramidis et al. (2012).

Between 15 ka cal BP and 12 ka cal BP, a general increase in woody vegetation is recorded at all sites, including two coastal basins close to the present estuaries of the Arno and Tiber rivers respectively (Amorosi et al. 2009; Milli et al. 2013). Excluding Pinus, the main arboreal component was deciduous Quercus, accompanied by Tilia, Corylus, Ulmus and other deciduous trees in low frequencies. A continuous presence of evergreen oaks is recorded especially along the Tyrrhenian coasts, suggesting that the Late Glacial increase of tree populations near the sea involved both the deciduous and evergreen elements of the woodland. In general, a moderate decrease of the arboreal vegetation is recorded during the Younger Dryas event, which is much better recorded in lacustrine cores from inland (Magri 1999; Allen et al. 2000; Drescher-Schneider et al. 2007; Di Rita et al. 2013).

Between 12 ka cal BP and 8 ka cal BP (Fig. 13.23), a general development of woodland is recorded, in response to increased water availability. Regional variations in the floristic composition of the vegetation may be explained by the proximity of refuge areas for trees and local physiographic and climatic conditions. For example, on the Versilian Plain and on the Ligurian coast, large amounts of Abies were present, probably from the slopes of nearby mountain ranges, and possibly also from the coastal plains (Mariotti Lippi et al. 2007; Bellini et al. 2009). On the north Adriatic coastal plain, significant amounts of Picea could reflect the presence of spruce in the alpine forelands (Miola et al. 2010). The coasts of Latium and Campania were characterized by mixed oak forest with sparse evergreen elements (Russo Ermolli & Di Pasquale 2002; Aiello et al. 2007; Milli et al. 2013). Along the Tyrrhenian coast, increasing amounts of Alnus and riparian plants point to the expansion of freshwater habitats as a consequence of changes in the groundwater table. The Adriatic coasts of the Balkan Peninsula were characterized by oak-dominated open woodlands, accompanied by significant amounts of Pistacia in Greece (Jahns 2005). Similarly, in southwestern Sicily the landscape was characterized by open vegetation with Mediterranean evergreen shrubs, dominated by Pistacia. The development of woodland was most likely hampered by climate aridity (Tinner et al. 2009).

Between 8 ka cal BP and 5 ka cal BP (Fig. 13.23), the development of the vegetation recorded by pollen diagrams in coastal sites was affected not only by plant population dynamics and climate change, but also by geomorphic processes connected to the sea-level rise and changes in the groundwater table (Di Rita et al. 2010). In the north Adriatic coast, pollen, plant macrofossils and non-pollen palynomorphs indicate the development of salt marsh plant communities around 6.7 ka cal BP in relation to the marine transgression (Miola et al. 2010). In the time interval 6.3 ka cal BP to 4 ka cal BP, a pollen record from the coastal Tavoliere Plain shows periodic fluctuations of a salt marsh, ascribed to a combination of slight sea-level fluctuations and changes in the precipitation/evaporation budget, connected to variations of the solar magnetic field and their influence on local atmospheric processes (Di Rita 2013). On the Tyrrhenian side of the Italian Peninsula, extensive freshwater basins along the coasts of Tuscany and Latium underwent significant variations of water depth, as indicated by changes in the extension of the Alnus carr (Di Rita & Magri 2012). On the southern Sicilian coast, the Neolithic cultural phase corresponds to the expansion of a close maquis, especially between 7 ka cal BP and 5 ka cal BP, which was not favorable for local agricultural practices and was only very slightly influenced by human activity (Noti et al. 2009; Tinner et al. 2009). The western coast of Greece experienced a reduction of Pistacia in favor of deciduous elements, suggesting a generally wetter climate (Jahns 2005).

On the whole, in the timespan 22 ka cal BP to 5 ka cal BP, an increasing number of pollen records describe the development of the vegetation on the central Mediterranean coasts (Di Rita & Magri 2012). Since the onset of the Holocene, the central Mediterranean coasts have hosted many diversified vegetational landscapes, correlated with regional and local physiographic and climate conditions, but in all cases the coastal vegetation appears very unstable and vulnerable to geomorphic processes and hydrological changes.

Areas of rapid erosion, and rapid accumulation of sediments since the LGM

Given the high variability of sediment supply, geological setting and shelf physiography, Italian shelves can be grouped in four end-members following the previous papers of Tortora et al. (2001) and Martorelli et al. (2014).

The first group is represented by wide shelves with high sediment supply, such as those developed in the Adriatic and central-northern Tyrrhenian Sea (part of the Latium and Tuscan shelves). These shelves are fed by large rivers (e.g. the Po, Tiber, Arno) or by several medium-sized rivers (e.g. the Apennine rivers for the central Adriatic). They are covered by a thick deposit of Holocene mud formed by the progradation of river deltas or the emplacement of mid-shelf mud belts (Figs. 13.13, 13.14; Amorosi & Milli 2001). Transgressive deposits are often lacking because the discharged river-mouth bed-load was trapped in coastal lagoons developing within fluvial valleys during sea-level rise, so that only a small amount of finer sediments were able to escape the lagoon, resulting in restricted units of fine sediment on the shelf.

The second group is represented by narrow shelves with high sediment supply, such as in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea, the western and northern Ionian Sea and the Ligurian Sea. These shelves are commonly characterized by steep slopes (>1°), limited width (few kilometers), and high sediment supply provided by ephemeral but powerful water courses, draining coastal ranges and transporting coarse-grained material into the sea during flash-flood events (e.g. Casalbore et al. 2011). The shelf is covered by a relatively large thickness of highstand mud that reaches the shelf break (Martorelli et al. 2010). In distinct contrast from the previous case, transgressive deposits are well developed, reaching their maximum thickness on Italian shelves, due to the lack of any major valley or coastal plain large enough to be able to store the sediment during the sea-level rise.

The third group is represented by shelves with a very low sediment supply and is typical of the Tyrrhenian islands, and of wide sectors of Sardinia, Apulia and Sicily (Fig. 13.24). These shelves are almost mud-free because of the lack of fluvial input and the high-energy hydrodynamic regime. The sedimentation is mainly intrabasinal, made up of volcaniclastic and bioloclastic material. In such settings, submerged depositional terraces (Chiocci et al. 2004) are often the only depositional bodies overlying the bedrock on the shelf.

Figure 13.24 Simplified map of the Italian continental shelf (in gray) with an indication of differences in the nature of sediment supply. Modified from Martorelli et al. (2014).

The fourth group is represented by wide shelves with low sediment supply and which have developed offshore of coastal lagoons or marshlands (such as in Tuscany, southern Latium, northern Apulia and Sardinia, Fig. 13.24). Here, the shelves are starved because fine sediments are trapped onshore, while beaches can be fed by longshore currents, creating narrow coastal prisms.

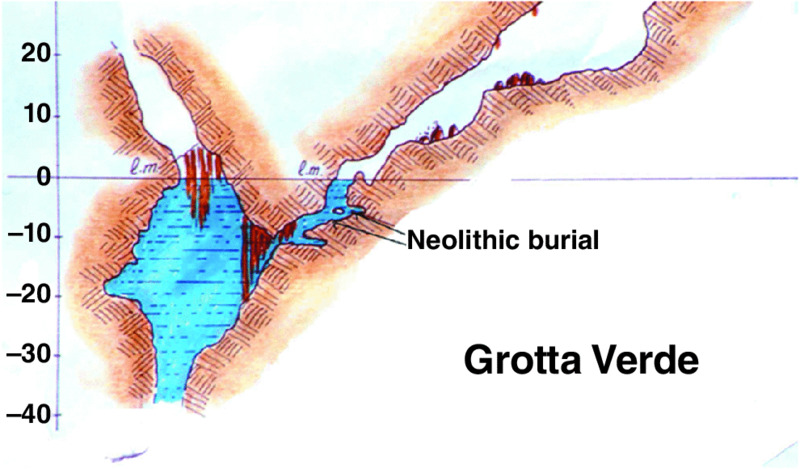

Conclusion

The central Mediterranean seas are very promising because of the presence of numerous partially sea-flooded caves, some of which have been shown in recent studies to contain dated prehistoric sites, especially in central and southern Italy. At the moment the only prehistoric site that has published data is the Grotta Verde in northwest Sardinia (Alghero), containing Neolithic-age burials with Cardial pottery (6.7–7.2 ka cal BP, Antonioli et al. 1997 Fig. 13.25) and the site of Pakostane in Croatia (Radic Rossi & Antonioli 2008), where some hand-made wooden remains were found in situ at –5 m and dated to the Neolithic, although this research is still a work in progress. Finally, we illustrate some interesting caves (Fig. 13.26) located in northern Sicily close to the coast and above sea level containing prehistoric remains, while there are unstudied sea-flooded caves between –40 m and –15 m located in the surrounding cliffs.

Figure 13.25 The Grotta Verde (Sardinia, Italy) section of a Neolithic necropolis containing ceramics and skeletons at –9 m and anthropic evidence until –11 m. Modified from Antonioli et al. (1997) with permission from UCL.

Figure 13.26 Emerged caves on land, on or close to the modern coastline in northern Sicily containing prehistoric remains. Modified from Mannino and Thomas (2007) with permission from UCL.

References

- Agate, M. & Lucido, M. 1995. Caratteri morfologici e sismostratigrafici della piattaforma continentale della Sicilia nord-occidentale. Naturalista siciliana 4:3-25.

- Aguzzi, M., Amorosi, A., Colalongo, M. L. et al. 2007. Late Quaternary climatic evolution of the Arno coastal plain (Western Tuscany, Italy) from subsurface data. Sedimentary Geology 202:211-229.

- Aiello, E., Bartolini, C., Gabbani, G. et al. 1978. Studio della piattaforma continentale medio tirrenica per la ricerca di sabbie metallifere: I) da Capo Linaro a Monte Argentario. Bollettino Società Geologica Italiana 97:495-525.

- Aiello, G., Barra, D., De Pippo, T., Donadio, C., Miele, P. & Russo Ermolli, E. 2007. Morphological and palaeoenvironmental evolution of the Vendicio coastal plain in the Holocene (Latium, Central Italy). Il Quaternario Italian Journal of Quaternary Sciences 20:185-194.

- Allen, J. R. M., Watts, W. A. & Huntley, B. 2000. Weichselian palynostratigraphy, palaeovegetation and palaeoenvironment: the record from Lago Grande di Monticchio, southern Italy. Quaternary International 73-74:91-110.

- Alpert, P., Baldi, M., Ilani, R. et al. 2006. Relations between climate variability in the Mediterranean region and the tropics: ENSO, South Asian and African monsoons, hurricanes and Saharan dust. In Lionello, P., Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. & Boscolo, R. (eds.) Mediterranean Climate Variability (Developments in Earth and Environmental Sciences series). pp. 149-177. Elsevier: Amsterdam.

- Alvisi, M., Colantoni, P. & Forti, P. 1994. Memorie dell'Istituto Italiano di Speleologia 6 (Serie II).

- Amorosi, A. & Milli, S. 2001. Late Quaternary depositional architecture of Po and Tevere river deltas (Italy) and worldwide comparison with coeval deltaic successions. Sedimentary Geology 144:357–375.

- Amorosi, A., Ricci Lucchi, M., Rossi, V. & Sarti, G. 2009. Climate change signature of small-scale parasequences from Lateglacial-Holocene transgressive deposits of the Arno valley fill. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 273:142-152.

- Antonioli, F. & Ferranti, L. 1994. La Grotta sommersa di Cala dell'Alabastro (S. Felice Circeo). Memorie della Società Speleologica Italiana 6:137-142.

- Antonioli, F. & Muccedda, M. 1997. La grotta dei Cervi a Punta Giglio. Speleologia 37:61-66.

- Antonioli, F., Ferranti, L. & Lo Schiavo, F. 1997. The submerged Neolithic burials of the Grotta Verde at Capo Caccia (Sardinia, Italy) implication for the Holocene sea-level rise. Memorie Descrittive del Servizio Geologico Nazionale 52:329-336.

- Antonioli, F., Improta, S., Nisi, M. F., Puglisi, C. & Verrubbi, V. 2000. Nuovi dati sulla trasgressione marina olocenica e la subsidenza della pianura versiliese (Toscana Nord-Occidentale). Atti del Convegno: ‘Le Pianure: Conoscenza e Salvaguardia. Il contributo delle scienze della terra’. 8th – 10th November 1999, Regione Emilia-Romagna, pp. 214-218.

- Antonioli F., Vai G. B. & Cantelli L. 2004. Litho-Palaeoenvironmental maps of Italy during the last two climatic extremes two maps 1:1.000.000. Explanatory notes edited by Antonioli F., and Vai G.B., 32° IGC publications: Bologna.

- Antonioli, F., Anzidei, M., Auriemma, R. et al. 2007. Sea-level change during the Holocene in Sardinia and in the northeastern Adriatic (central Mediterranean Sea) from archaeological and geomorphological data. Quaternary Science Reviews 26:2463-2486.

- Antonioli, F., Ferranti, L., Fontana, A. et al. 2009. Holocene relative sea-level changes and vertical movements along the Italian coastline. Quaternary International 206:102-133.

- Antonioli, F., D'Orefice, M. & Ducci, S. et al. 2011. Palaeogeographic reconstruction of northern Tyrrhenian coast using archaeological and geomorphological markers at Pianosa island (Italy). Quaternary International 232:31-44.

- Antonioli, F., Lo Presti, V., Anzidei, M. et al. 2013. Formazione di solchi di battente marini attuali sulle coste del Mediterraneo centrale. Miscellanea INGV (no. 19) Riassunti del Congresso AIQUA 2013 L'ambiente Marino Costiero del Mediterraneo oggi e nel recente passato geologico. Conoscere per comprendere. 19th – 21st June 2013, Naples, p.54.

- Anzidei, M., Baldi, P., Casula, G. et al. 2001. Insights into present-day crustal motion in the central Mediterranean area from GPS surveys. Geophysical Journal International 146:98-110.

- Anzidei, M., Baldi, P., Pesci, A. et al. 2005a. Geodetic deformation across the Central Apennines from GPS data in the time span 1999-2003. Annals of Geophysics 48:259-271.

- Anzidei, M., Esposito, A., Bortoluzzi, G. & De Giosa, F. 2005b. The high resolution bathymetric map of the exhalative area of Panarea (Aeolian Islands, Italy). Annals of Geophysics 48:899-921.

- Anzidei, M., Antonioli, F., Lambeck, K., Benini, A., Soussi, M. & Lakhdar, R. 2011a. New insights on the relative sea level change during Holocene along the coasts of Tunisia and western Libya from archaeological and geomorphological markers. Quaternary International 232:5-12.

- Anzidei, M., Antonioli, F., Benini, A. et al. 2011b. Sea level change and vertical land movements since the last two millennia along the coasts of southwestern Turkey and Israel. Quaternary International 232:13-20.

- Anzidei, M., Antonioli, F., Benini, A., Gervasi, A. & Guerra, I. 2013. Evidence of vertical tectonic uplift at Briatico (Calabria, Italy) inferred from Roman age maritime archaeological indicators. Quaternary International 288:158-167.

- Arca, S., Carboni, A., Cherchi, S. et al. 1979. Dati preliminari sullo studio della piattaforma continentale della sardegna meridionale per la ricerca di placers. In Atti Convegno Nazionale Progetto Finalizzato Oceanografia e Fondi Marini. 5th – 17th October 1979, Rome, pp. 567-576.

- Asioli, A., Trincardi, F., Lowe, J. J., Ariztegui, D., Langone, L. & Oldfield, F. 2001. Sub-millennial scale climatic oscillations in the central Adriatic during the Lateglacial: palaeoceanographic implications. Quaternary Science Reviews 20:1201-1221.

- Aucelli, P. P. C., Aminti, P. L., Amore, C. et al. 2007. Lo stato dei litorali italiani. Gruppo Nazionale per la Ricerca sull'Ambiente Costiero. Studi Costieri 10:5-112.

- Auterio, M., Milano, V., Sassoli, F. & Viti, C. 1978. Fenomeni di subsidenza nel comprensorio del consorzio di bonifica della Versilia. Atti del Convegno: ‘I problemi della subsidenza nella politica del territorio e della difesa del suolo’. 9th – 10th November 1978, Pisa, pp. 65-82.

- Avramidis, P., Geraga, M., Lazarova, M. & Kontopoulos, N. 2012. Holocene record of environmental changes and palaeoclimatic implications in Alykes Lagoon, Zakynthos Island, western Greece, Mediterranean Sea. Quaternary International 293:184-195.

- Bartolini, C., Bernabini, M., Burragato F. & Maino, A. 1986. Rilievi per placers sulla piattaforma continentale del Tirreno centro-settentrionale. In Rapporto Tecnico Finale del Progetto Finalizzato: Oceanografia e Fondi Marini Sottoprogetto ‘Risorse minerarie’. pp 97-117. CNR: Firenze.

- Bellini, C., Mariotti-Lippi, M. & Montanari, C. 2009. The Holocene landscape history of the NW Italian coasts. The Holocene 19:1161-1172.

- Bigi, G., Castellarin, A., Coli, M. et al. 1990. Modello Strutturale d'Italia. CNR SELCA: Firenze.

- Biserni, G. & van Geel, B. 2005. Reconstruction of Holocene palaeoenvironment and sedimentation history of the Ombrone alluvial plain (South Tuscany, Italy). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 136:16-28.

- Bonsignore, F. & Vicari, L. 2000. La subsidenza nella Pianura emiliano-romagnola: criticità ed iniziative in atto. Atti del Convegno ‘Le Pianure: Conoscenza e Salvaguardia. Il contributo delle scienze della terra’. 8th – 10th November 1999, Regione Emilia-Romagna, pp. 119-121.

- Brondi, A., Cicero, A. M., Magaletti, E. et al. 2003. Italian coastal typology for the European Water Framework Directive. In Özhan, E. (ed.) Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the Mediterranean Coastal Environment Vol. 2 (MEDCOAST ’03). 7th – 11th October 2003, Ravenna (Italy), pp. 1179–1188.

- Cacho, I., Grimalt, J. O., Pelejero, C. et al. 1999. Dansgaard-Oeschger and Heinrich event imprints in Alboran Sea paleotemperatures. Paleoceanography 14:698-705.

- Caldara, M., Caroli, I. & Simone O. 2008. Holocene evolution and sea-level changes in the Battaglia basin area (eastern Gargano coast, Apulia, Italy). Quaternary International 183:102-114.

- Camuffo, D. & Sturaro, G. 2004. Use of proxy-documentary and instrumental data to assess the risk factors leading to sea flooding in Venice. Global and Planetary Change 40:93-103.

- Capotondi, L. 2004. Marine Sea surface Temperature. In Antonioli, F. & Vai, G. B. (eds.) Litho-Paleoenvironmental Maps of Italy During the Last Two Climatic Extremes. Map 1: Last Glacial Maximum Map 2: Holocene Climatic Optimum — Explanatory notes. pp. 53-56. 32° IGC publications: Bologna.

- Carbognin, L., Teatini, P. & Tosi, L. 2004. Eustacy and land subsidence in the Venice Lagoon at the beginning of the new millennium. Journal of Marine Systems 51:345-353.

- Carminati, E. & Martinelli, G. 2002. Subsidence rates in the Po Plain, northern Italy: the relative impact of natural and anthropogenic causation. Engineering Geology 66:241-255.

- Caroli, I. & Caldara, M. 2007. Vegetation history of Lago Battaglia (eastern Gargano coast, Apulia, Italy) during the middle-late Holocene. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 16:317-327.

- Casalbore, D., Chiocci, F. L., Scarascia Mugnozza, G., Tommasi, P. & Sposato, A. 2011. Flash-flood hyperpycnal flows generating shallow-water landslides at Fiumara mouths in Western Messina Straits (Italy). Marine Geophysical Research 32:257–271.

- Cattaneo, A., Correggiari, A., Langone, L. & Trincardi, F. 2003. The late-Holocene Gargano subaqueous delta, Adriatic shelf: sediment pathways and supply fluctuations. Marine Geology 193:61-91.

- Cavaleri, L. 2000. The oceanographic tower Acqua Alta — activity and prediction of sea states at Venice. Coastal Engineering 39:29-70.

- Cavaleri, L., Bertotti, L & Lionello, P. 1991. Wind wave cast in the Mediterranean Sea. Journal Geophysical Research — Oceans 96:C6 10739-10764.

- Chiocci, F. L. 1994. Very high-resolution seismics as a tool for sequence stratigraphy applied to outcrop scale-examples from eastern Tyrrhenian margin Holocene/Pleistocene deposits. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin 78:378-395.

- Chiocci, F. L. 2000. Depositional response to Quaternary fourth-order sea-level fluctuations on the Latium margin (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). In Hunt, D. & Gawthorpe, R. L. (eds.) Sedimentary responses to forced regressions (Geological Society Special Publication) 172:271-289.

- Chiocci, F. L. & La Monica G. B. 1996. Analisi sismostratigrafica della piattaforma continentale. In Il Mare del Lazio. pp. 41-61. Università ‘La Sapienza’ di Roma: Lazio.

- Chiocci, F. L., D'Angelo, S., Orlando, L. & Pantaleone, A. 1989. Evolution of the Holocene shelf sedimentation defined by high-resolution seismic stratigraphy and sequence analysis (Calabro-Tyrrhenian continental shelf). Memorie Società Geolica Italiana 48:359-380.

- Chiocci, F. L., D'Angelo, S., & Romagnoli C. (eds.) 2004. Atlante dei Terrazzi Deposizionali Sommersi lungo le coste italiane. Memorie Descrittive della Carta Geologica d'Italia (vol. 58). Apat: Rome.

- Cicogna Nike Bianchi, C. & Ferrari, G. 2003. Grotte marine d'Italia 50 anni di ricerche. Ministero dell'Ambiente: Rome.

- CLIMAP 1981. Climate Long-range Investigation, Mapping, and Prediction. Available at www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo/climap.html.

- Colombaroli, D., Marchetto, A. & Tinner W. 2007. Long-term interactions between Mediterranean climate, vegetation and fire regime at Lago di Massaciuccoli (Tuscany, Italy). Journal of Ecology 95:755-770.

- Combourieu-Nebout, N., Paterne, M., Turon, J.-L. & Siani, G. 1998. A high-resolution record of the last deglaciation in the central Mediterranean Sea: Palaeovegetation and palaeohydrological evolution. Quaternary Science Reviews 17:303-317.

- Corradi, N., Fanucci, F., Fierro, G., Firpo, M., Picazzo, M. & Mirabile, L. 1984. La piattaforma continentale ligure: caratteri, struttura ed evoluzione. In Rapporto Tecnico Finale del Progetto Finalizzato: ‘Oceanografia e Fondi Marini’. pp. 1-34. CNR: Rome.

- Dercourt, J., Ricou, L. E. & Vrielynck, B. (eds.) 1993. Atlas Tethys Palaeoenvironmental Maps. Gauthiers-Villars: Paris.

- Dewey, J. F., Pitman, W. C., Ryan, W. B. F. & Bonnin, J. 1973. Plate tectonics and evolution of the Alpine system. Geological Society of America Bulletin 84:3137-3180.

- Di Donato, V., Esposito, P., Russo-Ermolli, E., Scarano, A. & Cheddadi, R. 2008. Coupled atmospheric and marine palaeoclimatic reconstruction for the last 35 ka in the Sele Plain-Gulf of Salerno area (southern Italy). Quaternary International 190:146-157.

- Di Rita, F. 2013. A possible solar pacemaker for Holocene fluctuations of a saltmarsh in southern Italy. Quaternary International 288:239-248.

- Di Rita, F. & Magri, D. 2009. Holocene drought, deforestation, and evergreen vegetation development in the central Mediterranean: a 5500 year record from Lago Alimini Piccolo, Apulia, southeast Italy. The Holocene 19:295-306.

- Di Rita, F. & Magri, D. 2012. An overview of the Holocene vegetation history from the central Mediterranean coasts. Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences 4:35-52.

- Di Rita, F. & Melis R. T. 2013. The cultural landscape near the ancient city of Tharros (central West Sardinia): vegetation changes and human impact. Journal of Archaeological Science 40:4271-4282.

- Di Rita, F., Celant, A. & Magri D. 2010. Holocene environmental instability in the wetland north of the Tiber delta (Rome, Italy): sea-lake-man interactions. Journal of Paleolimnology 44:51-67.

- Di Rita, F., Simone, O., Caldara, M., Gehrels, W. R. & Magri, D. 2011. Holocene environmental changes in the coastal Tavoliere Plain (Apulia, southern Italy): A multiproxy approach. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 310:139-151.

- Di Rita, F., Anzidei, A. P. & Magri, D. 2013. A Lateglacial and early Holocene pollen record from Valle di Castiglione (Rome): Vegetation dynamics and climate implications. Quaternary International 288:73-80.

- Djamali, M., Gambin, B., Marriner, N. et al. 2013. Vegetation dynamics during the early to mid-Holocene transition in NW Malta, human impact versus climatic forcing. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 22:367-380.

- Doglioni C. 1991. A proposal for the kinematic modelling for W-dipping subductions — possible applications to the Tyrrhenian–Apennines system. Terra Nova 3:423-434.

- Drescher-Schneider, R., de Beaulieu, J.-L., Magny, M. et al. 2007. Vegetation history, climate and human impact over the last 15,000 years at Lago dell'Accesa (Tuscany, Central Italy). Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 16:279-299.

- Esposito, A., Anzidei, M., Atzori, S., Devoti, R., Giordano, G. & Pietrantonio G. 2009. Modeling ground deformations of Panarea volcano hydrothermal/geothermal system (Aeolian Islands, Italy) from GPS data. Bulletin of Volcanology 72:609–621.

- Fabris, M., Baldi, P., Anzidei, M., Pesci, A., Bortoluzzi, G. & Aliani S. 2010. High resolution topographic model of Panarea Island by fusion of photogrammetric, Lidar and bathymetric digital terrain models. The Photogrammetric Record 25:382-401.

- Faccenna, C., Jolivet, L., Piromallo, C. & Morelli, A. 2003. Subduction and the depth of convection in the Mediterranean mantle. Journal of Geophysical Research 108 (B2):2099.

- Favaretto, S., Asioli, A., Miola, A. & Piva, A. 2008. Preboreal climatic oscillations recorded by pollen and foraminifera in the southern Adriatic Sea. Quaternary International 190:89-102.