The macronutrients—protein, fat and carbohydrate—are essential nutrients that supply energy and are required in relatively large quantities for the body. Protein and fat are also functional building blocks and have a diverse range of uses in the body, including growth and repair, as well as being the precursors for hormones and components of the immune system. While alcohol may be considered a macronutrient because it provides energy, it is in a unique category; it is not required by the body per se and it also has toxic properties, and for this reason it is not considered essential. Interestingly, all of these macronutrients are composed of the same elements: carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N) and hydrogen (H). This chapter will outline their chemical and biological properties, the importance of each in the diet, and recommended intakes for good health. This chapter will also provide you with the foundation knowledge you will need to study the remaining chapters of this textbook, to build your knowledge on nutrition for exercise and performance.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Upon completion of this chapter you will be able to:

• describe the chemical and biological properties of the macronutrients

• outline the physiological and biochemical uses of macronutrients in the body

• describe the health effects of under- and overconsumption of the macronutrients

• explain the synthesis and metabolism of the macronutrients

• outline the recommended intakes and dietary sources of the macronutrients.

PROTEIN

Proteins are essential nutrients, which provide 17 kJ/g (4 cal/g) of energy and are made up of single units known as amino acids. Amino acids are the building blocks of the human body and are used to synthesise cells, muscle, organs, hormones and immune factors, as well as acting as buffers to regulate the acidity or basicity of the body.

Chemical structure

Proteins are composed of amino acid chains, linked together by peptide bonds (chemical bonds between amino acids). Proteins vary according to the number and sequence of amino acids, the folding of the protein and the interaction with other chemical groups in the protein to induce chemical change. All of this leads to unique individual proteins, reflecting the variety of roles they play in your body.

Box 4.1: Calculating energy from macronutrients in food

To calculate the energy present in foods, you need to multiply the total amount of each of the macronutrients contained in the food (in grams) by the Atwater factors for protein, fat and carbohydrate. The Atwater factors provide the available energy for each of the macronutrients regardless of the food from which they are derived.

ATWATER FACTORS

• Protein: 17 kJ/g

• Fat: 37 kJ/g

• Carbohydrate: 17 kJ/g

For example, a food label might indicate that there is:

• Protein: 9.6 g

• Fat (total): 3.2 g

• Carbohydrate: 43.0 g

In this case, the energy in kilojoules that is provided by each nutrient is as follows:

• Protein: 9.6 x 17 = 163.2 kJ

• Fat: 3.2 x 37 = 118.4 kJ

• Carbohydrate: 43 x 17 = 731 kJ

• Total energy: 163.2 + 118.4 + 731 = 1012.6 kJ

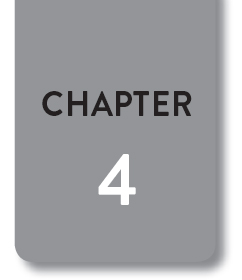

All amino acids have the same basic chemical structure: a central carbon to which is attached a hydrogen group (H), an amino group (NH2), a carboxylic acid group (COOH) and a side chain group. It is the side chain group that makes each of the amino acids different (see Figure 4.1). There are 20 different amino acids; nine are essential and the remaining 11 are non-essential.

Figure 4.1. Chemical structure of amino acids

Source: Hodgson 2011, pp. 295–311.

There are nine amino acids that the human body requires but is unable to synthesise, and which therefore must be obtained from nutrients. As such, they are termed essential (or indispensable). These are histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan and valine. Depletion of essential amino acids in the protein pool in the body will begin to limit the production of proteins essential for growth, repair, cell functioning and development.

Synthesise

To form a substance by combining elements.

Non-essential amino acids

There are 11 non-essential (or dispensable) amino acids that the body is able to synthesise, but that can also be provided by diet. In some conditions, a non-essential amino acid may become essential; in such cases the amino acid is referred to as conditionally essential (or conditionally indispensable). Tyrosine is a conditionally essential amino acid, as the body uses tryptophan to make tyrosine: if tryptophan is limited it is then unable to synthesise tyrosine.

Protein foods are often categorised in reference to their quality, both in terms of the mix and amount of amino acids that they contain. Complete protein sources often refer to animal-derived proteins that contain, in the required proportions, all the essential amino acids. Plant proteins are termed incomplete, as they are missing one or more of the essential amino acids, or have levels of an essential amino acid too low to meet requirements. Complementary proteins refer to the combination of two plant proteins to provide all the essential amino acids—for example, combining beans (lacking methionine) with grains (lacking lysine and threonine).

Uses in the body

Proteins have wide and varied roles in the human body: they are involved in the growth, repair and replacement of all cells (including blood, muscles, skeletal system, tissues and organs), and involved in regulating the homeostatic control and defence of the body (NHMRC et al. 2006).

One of the main functional roles of proteins in the body is as enzymes, which accelerate chemical reactions in the body. Enzymes are synthesised from amino acids as well as other dietary components (for example, zinc and selenium). They are used by every organ and cell to assist in the repair and growth of the body. Enzymes also contribute to the synthesis of proteins involved in the homeostatic control of the body, immune function, fluid balance regulation, transportation of nutrients and other molecules, and detoxification of the body. In addition to protein’s critical role in growth and regulation of the body, protein can also be used as a source of energy if carbohydrate and fat intake is low (for instance, during times of starvation). If needed, muscle will be broken down to provide further energy if dietary intake of protein is also limited. Protein may also be metabolised for energy when energy demands are sustained over a long period of time in performance, such as in ultra-endurance events lasting 3–4 hours or more.

Box 4.2: Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs)

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has analysed and synthesised the data from many thousands of peer-reviewed journal articles (the evidence base) to formulate the Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs) (NHMRC et al. 2006). The NRVs are a set of recommended intakes for macro- and micronutrients that best support healthy Australians to maintain good health. Requirements are expressed in the following categories:

Estimated Average Requirements (EAR): This is a daily nutrient level that has been estimated from the evidence base to meet the requirements of half of the healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group.

Recommended Dietary Intake (RDI): The average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97–98 per cent) healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group. This is the recommended level of intake for individuals.

Acceptable Intake (AI): For some nutrients there is an inadequate evidence base to provide an EAR or RDI. In such cases an AI is recommended. This is defined as the average daily nutrient intake level—based on observed or experimentally determined approximations or estimates of nutrient intake of a group (or groups) of apparently healthy people—that is assumed to be adequate.

Estimated Energy Requirements (EER): The average dietary energy intake that is predicted to maintain energy balance in a healthy adult of defined age, gender, weight, height and level of physical activity, consistent with good health. In children and pregnant and lactating women, the EER is taken to include the needs associated with growth or the secretion of milk at rates consistent with good health.

Upper Level of Intake (UL): The highest average daily nutrient intake level likely to pose no adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population. As intake increases above the UL, the potential risk of adverse effects increases.

Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDR): Recommended ranges of macronutrient contribution to total daily energy intake to reduce chronic disease risk while still ensuring adequate micronutrient status: protein 15–25 per cent; fat 20–35 per cent; and carbohydrate 45–65 per cent.

The NRVs are expressed in different formats that reflect intakes recommended for individuals and groups, the level of evidence for a nutrient and, where relevant, the highest possible safe intake of a nutrient. It is important to realise that, like other biological characteristics of humans such as height or eye colour, each person is unique and will have different nutrient requirements, and the NRVs take that into account. For example, the RDI for men and women over 19 years of age for vitamin C is 45 mg/day, but not everyone will require that amount. In fact, 97.98 per cent of the healthy population will have their requirements met at this level of intake, meaning that only 2.02 per cent of the population will need more than this. The EAR for vitamin C is 30 mg/day, which indicates that half of the population will only need this amount.

Recommended intakes for non-athletes

Protein in the body is continuously broken down and resynthesised. This process is known as protein turnover, with small amounts of protein lost in the stools. Protein is required on a daily basis in the diet due to its ubiquitous role and limited storage in the body. It is recommended that protein intake provides about 10–15 per cent of the daily energy requirement. For the average adult who needs approximately 8700 kJ per day, this equates to about 50–75 g of protein per day. The NRV recommendations for protein are based on a g/kg of body weight for each gender and age group. The daily RDI for women aged 19–70 years is 0.75 g/kg and over 70 years is 0.94 g/kg of body weight. The RDI for men aged 19–70 years is 0.84 g/kg and over 70 years is 1.07 g/kg of body weight. Requirements for athletes may differ, dependent on their age and sport played, as discussed in Chapter 10.

While animal products that are rich in protein are greatly valued for their high-quality protein (as they provide a complete set of amino acids), plant proteins provide a major source of protein for many millions of people around the world. Animal sources of protein also provide valuable additional nutrients that have limited presence in other foods, such as iron and zinc (present in meat), and calcium and vitamin B12 (present in dairy). Plant sources of protein (wheat, rice, pasta, legumes, nuts and seeds) also provide carbohydrates, B-group vitamins and fibre. This makes food sources of protein, compared to protein supplements, valuable for athletes and non-athletes who need to ensure that they are getting a balanced diet in regard to other macronutrients and micronutrients of importance in exercise and performance.

Health effects of protein

Protein is important for the maintenance and health of our bodies, and the majority of Western populations consume adequate intakes for this. However, in developing countries the health problems associated with protein deficiencies are devastating, and it is the leading cause of death among children in these places.

In most cases, protein deficiency occurs in combination with an energy deficiency, and is referred to as protein-energy malnutrition (PEM). Primary PEM occurs as the direct result of diets that lack both protein and energy. Secondary PEM arises as a complication of chronic illness, such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), tuberculosis and cancer, due to increased nutritional requirements, limited oral intake or malabsorption of nutrients. Acute PEM refers to a short period of food deprivation, as in the case of children who are often the appropriate height for age but underweight. Chronic PEM refers to long-term food deprivation that affects growth and weight, and is characterised by small-for-age children.

PEM presents clinically in two different forms: kwashiorkor and marasmus. Kwashiorkor typically represents a sudden and recent deprivation of food (protein and energy). In Ghanaian, the word refers to the illness an older child develops when the next child is born, as a result of being moved off the breast. Clinically, kwashiorkor has a rapid onset due to inadequate protein intake or following illness, with both weight loss and some muscle wasting. The characteristic clinical feature is oedema (swelling caused in the body as fluid leaks out of capillaries), which is evident from a child’s swollen belly, enlarged fatty liver, dry brittle hair and the development of skin lesions. Apathy, misery, irritability and melancholy are also evident, with loss of appetite. Marasmus occurs with a severe deprivation of food (both in protein, energy and nutrients) for an extended period of time; the malnutrition develops slowly and children typically look small for their age. Unlike kwashiorkor, there is no oedema, no enlarged fatty liver and the skin is dry and easily wrinkles.

In developed regions, protein deficiency is more likely to arise due to chronic illness or poverty and, as such, it is unlikely an athlete will have a compromised protein intake—unless it reflects a philosophical or religious reason that limits their intake of animal products. Chapter 6 will discuss planning diets for people who choose to follow a vegetarian diet.

LIPIDS

Lipids (or fats) are a large and diverse group of naturally occurring molecules, both in the diet and in the human body. They include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins, monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides, phospholipids and esters, which we will cover in this chapter. Dietary fats provide a concentrated form of energy (37 kJ/g) and are also a vehicle in the diet for supplying fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E and K) and essential fatty acids (alpha-linolenic acid and linoleic acid). Importantly, and often under-considered, dietary fat provides important organoleptic (taste and texture) properties to food that contains fats and to meals to which fats have been added. Lipids play critical roles in the body, including storing energy, cell signalling and as the major structural component of cell membranes. While the intake of certain dietary fats (saturated and trans fats) is associated with the development of chronic disease, dietary fats are an essential part of the diet, providing essential fatty acids, vitamins and other phytonutrients.

Organoleptic

The aspect of substances, in this case food and drink, that an individual experiences via the senses of taste, texture, smell and touch.

Chemical structure

All lipids are compounds that are composed of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen and are insoluble in water, but the different types of lipids that exist are structurally very diverse. There are four main categories: fatty acids, triglycerides, sterols and phospholipids (see Figure 4.2).

Fatty acids

Fatty acids are composed of a chain of carbon (C) atoms, attached by single bonds. Each C atom can have up to four H atoms attached. The carbon chain has a carboxyl group at one end and a methyl group at the other end. Fatty acids can be classified according to the number of C atoms in the chain. Short-chain fatty acids have 2–6 C atoms, medium-chain fatty acids 6–12 C atoms, long-chain 14–20 C atoms and, finally, very long-chain fatty acids more than 20 C atoms. Fatty acids are, however, more often classified according to the number of double bonds present between the C atoms—the more double bonds in the chain, the more unsaturated the fatty acid.

Figure 4.2. Structural relationship of some fatty acids

Source: Jones & Hodgson 2011, pp. 284–94.

Fatty acid chains that contain no double bonds between the C atoms are referred to as saturated fatty acids. They are mostly found in animal food products, such as meat, cheese and butter, but are also present in some plant products, such as coconut and palm oils. Saturated fats are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease; however, emerging research is beginning to show that their effect may not be as great as once thought (Dehghan et al. 2017). The research and scientific debate in this area is still continuing and as new high-quality evidence emerges this may lead to changes in dietary advice.

Monounsaturated fatty acids

Monounsaturated fatty acids contain one double bond in the C chain and are found in foods such as olives and olive oil, avocadoes and some types of nuts. Monounsaturated fats (from olive oil) are one of the main components of the Mediterranean diet, which has been shown in both epidemiological studies and intervention studies to reduce risk and provide benefits in cardiovascular disease. It is important to note that the other components of the Mediterranean diet (vegetables, fruit and grains) also play a role in good health.

Epidemiological studies

Studies that analyse the distribution (who, when and where) and determinants of health and disease in a defined population by observation. Epidemiological studies include ecological, case-control, cross-sectional and retrospective or prospective longitudinal cohorts study designs.

Intervention studies

Studies in which researchers make changes to observe the effect on health outcomes; in nutrition, this will include changes to diet.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) contain two or more double bonds in the C chain. PUFAs are further subdivided according to the position of the first double bond in the chain. When the double bond occurs on the third C atom from the methyl end, they are referred to as n-3 (or omega-3) fatty acids. If the first double bond occurs on the sixth C atom from the methyl end they are referred to as n-6 (or omega-6) fatty acids. The parent fatty acids of the n-3 and n-6, alpha-linolenic and linoleic acid respectively, are the essential fatty acids. They are known as essential, as the human body is unable to synthesise them, and, as such, must be obtained from the diet.

n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids

Linoleic acid (LA) is the parent fatty acid of the n-6 PUFA and, as it is essential, needs to be obtained from the diet. LA is found as a concentrated source in vegetable oils like safflower and sunflower oils, and salad dressings made from these oils. It is also present in some nuts and seeds. LA is important, as it can be metabolised through a series of reactions to form the longer-chain fatty acid, arachidonic acid (AA). AA can also be found in the diet (in meat). AA is the direct precursor of a diverse group of hormone-like substances known as eicosanoids, which play a critical role in the inflammatory process and in thrombosis (clot formation).

n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) is the parent fatty acid of the n-3 PUFA, and like LA, it needs to be obtained from the diet. ALA is found in concentrated sources in flaxseed (linseed) oil, and in smaller amounts in canola oil. Walnuts, chia seeds and green leafy vegetables also contain small amounts of ALA. ALA is metabolised through the same chain of reactions that converts LA to AA, to form the longer-chain fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). EPA and DHA are found in fish, fish oil and breast milk. Like AA, EPA is important, as it is the direct precursor of a diverse group of hormone-like substances known as eicosanoids; however, eicosanoids derived from EPA are anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic, compared to those derived from AA.

This biochemical difference between the two classes of fatty acids and their eicosanoids has been used therapeutically in the management of inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. DHA is found in concentrated amounts in the cellular phospholipids of brain and neural tissue of humans and, as such, its role in foetal and early-life nutrition is critical.

Trans fatty acids

Trans fatty acids (TFAs) are a chemical variation of unsaturated fats. In the cis-form (the regular form), the C atoms that have double bonds and the H atoms are on the same side. In the trans form, the H-atoms are on opposite sides of the double-bonded C atoms, so that they look and act more like saturated fats.

Cis form

In a molecule, the C atoms that have double bonds and the H atoms are on the same side.

Trans form

In a molecule, the C atoms that have double bonds and the H atoms are on opposite sides.

TFAs naturally occur in dairy products and beef. In the food industry, manufacturers can produce TFAs by mixing H atoms with the unsaturated fatty acids, using a mixture of heat and pressure. This results in liquid oils being transformed into a solid state, making them very useful for the production of certain foods, such as spreads and vegetable shortening for baking. However, these TFAs have been shown to be worse for cardiovascular disease compared to the equivalent amounts of saturated fat. The WHO has recommended that no more than one per cent of our dietary energy be derived from TFAs. In many countries, including Australia, Denmark and the United States, there has been a reduction in TFA use in the food supply, either through voluntary initiatives or legislation (FSANZ 2017).

Triglycerides

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat (adipose tissue) in animals, including humans. They are made up of a glycerol backbone with three fatty acids attached. All triglycerides are composed of different types of fatty acids, from short-chain to long-chain. Triglycerides are also the main type of fat we consume in our food, from both vegetable and animal sources.

Sterols

Sterols are complex lipid molecules, having four interconnected carbon rings with a hydrocarbon side chain. The most familiar type of sterol is cholesterol, which is a critical component of cell membranes and a precursor to vitamin D, the sex hormones (oestrogen and testosterone) and the adrenal hormones (cortisol, cortisone and aldosterone).

Cholesterol can be synthesised in the body, and hence is not essential in the diet. Dietary cholesterol is only found in animal products. Cholesterol in the body can be classified as either high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) depending on whether it is part of a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) molecule. LDL-C is referred to as ‘bad’ cholesterol, as LDL takes cholesterol to the blood vessels where it can form into atherosclerotic plaques, which can lead to blockages and myocardial infarction (heart attack). HDL-C is referred to as ‘good’ cholesterol, as HDL takes cholesterol away from the blood vessels to the liver, hence reducing the risk of a myocardial infarction.

Lipoprotein

A cluster of lipids attached to proteins that act as transport vehicles for the lipids in the blood. They are divided according to their density.

Plants synthesise many types of sterols, as well as stanols, which are structurally similar to sterols. Sterols and stanols are poorly absorbed by the body and reduce the absorption of cholesterol from the gastrointestinal system, which can have beneficial effects for cholesterol reduction. The food industry has added plant sterols to some types of margarines, milks, yoghurts and cereals, which can lead to a reduction in cholesterol levels if at least 2–3 g/day of plant sterols or stanols are consumed.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids have a unique chemical structure; they are soluble in both water and fat. They are similar to triglycerides, in that they have a glycerol backbone, but have only two fatty acids attached to the glycerol—the third position is taken up by a phosphate and a ‘head-group’. It is the combination of the head-group, phosphate group and glycerol backbone that makes phospholipids soluble in water, while the fatty acids (the tail group) makes them soluble in fats. This feature gives them a critical role, both in the body and in the food industry. Despite their importance, phospholipids make up only a small portion of the diet (<5 per cent) and are not essential, as they can be synthesised by the body.

Phospholipids are able to freely move around the body, which enables them to transport other fats such as vitamins and hormones. They are also a critical component of the cellular membranes, where they form a phospholipid bilayer. The phospholipids assemble into two layers, with the hydrophilic (water-loving) ends on opposite sides, and the hydrophobic (water-fearing) ends facing each other on the inside. This arrangement allows for the transport of substances through the cellular membrane. Interestingly, the fatty acids attached to the phospholipids in the cellular membrane will reflect the dietary intake of fatty acids.

In the food industry, phospholipids (such as lecithin) allow foods to be emulsified, as in the production of salad dressings, mayonnaise, ice-cream and chocolate. Lecithin is found in eggs, liver, soybeans, wheat germ and peanuts.

Recommended intakes for the general population

The Nutrient Reference Values from the NMHRC have no set RDI, EAR or AI for total fat intake. However, there are recommendations for the intake of the essential fatty acids (NHMRC et al. 2006).

In the latest version of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating, which provides qualitative guidelines on healthy eating (discussed in Chapter 6), the recommendation is now to ‘avoid saturated fat’, which has changed from the previous recommendation to ‘decrease total fat’ (NMHRC et al. 2009). The AMDR from the NRV states that fat should contribute 20–35 per cent of your total energy intake (NHMRC et al. 2006). This highlights the importance of reducing the intake of foods that contain saturated fats in our diet and replacing them with monounsaturated oils and foods (olive, canola oil, avocado, almonds) or polyunsaturated oils and foods (nuts, fish, polyunsaturated vegetable oils).

Table 4.1. Recommendations for the intake of the essential fatty acids

| Fatty acid | Men 19+ years | Women 19+ years |

| LA | 13 g/day | 8 g/day |

| ALA | 1.3 g/day | 0.8 g/day |

| Total LC n-3 (DHA+EPA+DHA) | 160 mg/day | 90 mg/day |

Source: NHMRC et al. 2006.

CARBOHYDRATES

Carbohydrates, like fats and proteins, are molecules composed of C, H and O atoms. They are ubiquitous in the diet—present in breads, cereals, grains, legumes, rice, pasta, vegetables and fruit, although dairy is the only animal source of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates deliver the key source of fuel (energy) for the muscles and body, providing 17 kJ/g. Glucose, which is a monosaccharide (simple) sugar, is the exclusive source of energy for red blood cells and provides a significant portion of the energy that is required for the brain. Excess glucose in the blood is converted to the storage form of glucose, glycogen. The average person stores about 5000 kilojoules worth of glucose in the form of glycogen, which can be easily converted to glucose again to be used by the body when blood glucose levels begin to drop.

Carbohydrates have numerous biological functions in the body. Aside from their important role in providing energy, they also have a structural role. Ribose, which is a component of coenzymes and the backbone of RNA, is a five-C atom monosaccharide, and the closely related deoxyribose is a component of DNA. Carbohydrates also play key roles in the immune system and in blood clotting.

Chemical forms of carbohydrate

There are a wide variety of carbohydrates in the diet. They include simple carbohydrates (the sugars) and complex carbohydrates (the starches and fibre). Regardless of the length or complexity of the carbohydrate, they are all composed of sugar units (see Figure 4.3).

Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides are composed of a single unit of sugar and are the most basic units of carbohydrates. There are three monosaccharides or ‘sugars’: glucose, fructose and galactose. The monosaccharides all have the same number of C, H and O atoms but differ in their chemical structure. Monosaccharides are the building blocks of disaccharides and polysaccharides.

Glucose

Glucose (C6H12O6) serves as the essential energy source for our body; when people talk about blood sugar levels, they are referring to glucose in the blood. Most of the polysaccharides in our diet are composed of chains of glucose, with starch being the most common polysaccharide.

Figure 4.3. Chemical structure of carbohydrates

Source: Jones & Hodgson 2011, p. 268–83.

Fructose

The slightly different chemical structure of fructose results in it being the sweetest-tasting monosaccharide. Fructose occurs naturally in some fruits and honey. Fructose may be added to some foods, such as soft drinks, ready-to-eat breakfast cereals and desserts, and biscuit and cake mixes, through the use of high-fructose corn syrup.

Galactose is found in dairy products and sugar beets, and is the least sweet-tasting monosaccharide.

Disaccharides

Disaccharides are composed of two glucose units and can be formed as pairs of any of the three monosaccharides. There are three disaccharides, and each contains glucose as one of the monosaccharide components. Sucrose, which is common table sugar refined from cane sugar, is made up of glucose and fructose. Lactose is found in milk and is composed of galactose and glucose. Maltose, also known as malt sugar, is the disaccharide that is produced when amylase, an enzyme, breaks down starch.

Lactose intolerance

A condition that leads to the inability to digest lactose which results in bloating, abdominal discomfort, gas and diarrhoea.

Lactose intolerance is fairly common, with only about 30 per cent of adults worldwide being able to digest lactose. Intestinal cells produce an enzyme called lactase, which breaks lactose down into galactose and glucose. When lactase activity is low in people, the lactose remains undigested in the intestinal tract and leads to a high concentration of contents in the intestine, which in turn draws fluid into the intestinal lumen and, in combination with the proliferation of bacteria that digest the lactose, leads to painful bloating, wind and diarrhoea.

Artificial sweeteners

Artificial sweeteners are chemicals, found naturally (Stevia) or synthesised industrially (aspartame, saccharin), or are sugar alcohols, that have a sweet taste with either no kilojoules or reduced kilojoules compared to sugar. This allows the food industry to replace sugars with artificial sweeteners without adding kilojoules to the product. It was assumed that this would lead to significant weight loss in the community due to the decreased consumption of kilojoules, but research shows a lack of the predicted effect. Whether this is due to people increasing their consumption of other foods or the artificial sweeteners affecting metabolism in other ways is still being debated among researchers (Fowler et al. 2008).

Sugar alcohols

Carbohydrates that have been chemically altered. They provide fewer kilojoules as they are not well absorbed and may have a laxative effect. They include sorbitol, mannitol and xylitol. While they have fewer kilojoules they can still lead to elevation in blood glucose levels and, hence, can have an impact on blood glucose control in people with diabetes; as such they need to be considered in the diet.

Complex carbohydrates

Complex carbohydrates include oligosaccharides, which contain between three and nine monosaccharide units, and polysaccharides, which contain ten or more monosaccharide units.

Oligosaccharides are found in a variety of foods. Starch, which is found in a wide variety of foods, such as wheat, maize potato and rice, contains the α-glucan oligosaccharide maltodextrin. Maltodextrin is used in the food industry as a sweetener, fat substitute and to modify the texture of food through its thickening properties.

The oligosaccharides that are not α-glucans include raffinose, stachyose, verbascose, inulin and fructan, and are found in legumes, artichokes, wheat and rye, and in the onion, leek and garlic family. The fructans (including inulin) have unique properties in the gastrointestinal system and are referred to as prebiotics. Prebiotics remain undigested in the gastrointestinal system and promote the growth of select bacteria that improve human health. Consumption of these foods leads to alteration in the flora of the gut, with a domination of bifidobacteria and lactobacillus, and the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs, also referred to as volatile fatty acids (VFAs), are important for colonic health as they are the primary energy source for colon cells and have anti-carcinogenic and anti-inflammatory properties.

Prebiotics

Food components that are not digested in the gastrointestinal system but are used by the bacteria in the colon to promote their growth.

Polysaccharides

Glycogen

Glycogen is found in limited amounts in food, with a small amount found in meat. However, it is its role in the body that is critically important and of interest to nutritionists, including sports nutritionists. Glycogen is a secondary form of energy storage (~5000 kJ in the average person). When blood glucose levels increase following a meal, insulin is released, which stimulates the uptake of glucose into cells and storage as glycogen. Conversely, when blood glucose levels decrease due to lack of dietary intake of carbohydrates or depletion of blood glucose levels from exercise, the pancreas releases glucagon, which stimulates the liver and muscles to release and break down glycogen and release glucose (known as glycogenolysis). Glucose can also be derived through gluconeogenesis, which is a metabolic pathway that leads to glucose formation from substrates such as lactate, glycerol and glucogenic amino acids.

Glycogen is a highly branched structure, containing up to 30,000 glucose units that surround a protein core. Glycogen in the muscle, liver and fat cells is stored in a hydrated form with three or four parts of water per part of glycogen. This explains the dramatic weight loss that is seen with low-carbohydrate diets. In this scenario, as blood glucose levels decrease, glycogen is converted back to glucose to supply the brain and muscles with fuel, which also releases the water, hence contributing to the weight loss observed.

Starch is the form in which plants store glucose to use for energy. Some common starches include amylopectin and amylose. Both of these contain hundreds to thousands of glucose units linked together, as is the case with glycogen. Starch is found in many different foods including wheat, rice, lentils, maize, beans and the tuber vegetables. Starch forms the most common carbohydrate in our diet.

Resistant starch is one type of starch that resists digestion in the small intestine and is fermented in the large intestine by bacteria into short-chain fatty acids. These SCFAs are important as they protect the bowel against cancer and are also absorbed into the bloodstream and may be involved in lowering blood cholesterol. Resistant starch is found in unripe bananas, potatoes and lentils. In Australia, resistant starch is also commonly added to ‘high-fibre’ breads and cereals. It is also considered to be a form of insoluble fibre, which is discussed below.

Fibre

While there are many definitions of fibre, most simply, dietary fibre is a carbohydrate that is not digested by our body. Fibre is the parts of the edible portions of plants that are not digested or absorbed in the small intestine, that go on to be partially or completely fermented in the large intestine and that promote beneficial physiological effects. These beneficial effects include laxation of bowel movements, reduced blood cholesterol and beneficial modulation of blood glucose levels. Dietary fibre can include polysaccharides, oligosaccharides and lignin (scientific definition paraphrased from NHMRC et al. 2006, p. 45). The recommended intake from the NHMRC for dietary fibre is 30 g/day for men and 25 g/day for women. As there is a variety of types of fibre in food, researchers and nutritionists classify them into two different groups according to their physiological actions in the body.

Soluble fibre

Soluble fibre dissolves in water to form gels. The process of dissolving into a gel slows down digestion. Soluble fibres are found in oat bran, barley, nuts, seeds, legumes, and in some fruits and vegetables. Soluble fibre is commonly linked with reducing the incidence of cardiovascular disease and protecting against diabetes, by reducing blood cholesterol levels and lowering blood glucose levels.

Insoluble fibre

Conversely, insoluble fibre does not dissolve in water and is found in wheat bran, some vegetables and wholegrains. Insoluble fibre absorbs water and expands, adding bulk to stools and speeding its transit through the intestines, thereby promoting bowel movements and ameliorating constipation.

Dietary recommendations for carbohydrates

The Nutrient Reference Values do not provide specific recommendations (in grams per day) for carbohydrates, as there is limited data on which to base EAR, RDI or AI requirements for most age and gender groups, except for infancy (0–12 months) where values are based on what the infant receives from breast milk. This lack of recommendations regarding carbohydrates for the majority of age groups does not reflect the value carbohydrates have in the diet for providing glucose as a direct energy source for the brain, as well as being a carrier for many micronutrients and fibre, as discussed above. There is a mounting body of evidence for the role of carbohydrates in relation to chronic disease, and as such, an acceptable range of intake between 45 and 65 per cent of energy is recommended (NHMRC 2013). The recommendation is that carbohydrates should predominantly be derived from wholegrain, low-energy dense sources and/or from low glycaemic index foods (see below). This is supported by more recent evidence-based nutrition advice from the World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO 2015), which recommends limiting intake of added sugars to ten per cent of total energy intake.

Glycaemic response, index and load

Glycaemic response

The glycaemic response is defined by the length of time it takes for glucose to be absorbed from foods that have been consumed, regardless of whether the foods contain disaccharides or polysaccharides. A low glycaemic response indicates that the glucose is slowly absorbed over a longer period of time, resulting in a steady and modest rise in blood glucose levels after consumption of the food. A high glycaemic response indicates that the glucose is absorbed more quickly and that there is a sharp immediate rise in blood glucose levels. Other factors in food that will affect the glycaemic response, through their ability to delay or enhance the absorption of glucose, include:

• fat content (delays gastric emptying)

• acid content (delays gastric emptying)

• protein content (delays gastric emptying)

• amount and types of fibre (soluble fibre has lower glycaemic index than insoluble fibre)

• type of starch (depending on the structure of the molecule, which affects the rate of enzyme digestion)

• level of processing (wholegrain bread has a lower glycaemic index than wholemeal bread)

• sugar type (fructose and lactose have lower glycaemic index than glucose).

The glycaemic index (GI) is a system that ranks foods according to their potential to increase blood glucose levels, relative to the reference food of white bread (which is given a GI rank of 100). Foods are considered high GI if they rank above 70, and low GI if they rank below 55. The GI of foods is also affected by the level of fat, protein and fibre in them and, in drinks, the amount of carbonation. As such, it is important to appreciate that the GI does not always correlate with the overall healthiness of foods, as it does not consider the level of other micronutrients, sugar and saturated fat. For example, some cola-based soft drinks and sweetened chocolate hazelnut spread have a lower GI than pumpkin, white rice and couscous.

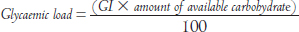

Glycaemic load

Glycaemic load (GL) is a measure that takes into account the amount of carbohydrate in the portion of food consumed, together with the GI of the food. A large intake of a food with a low GI could result in a high glycaemic response, compared to consuming a small portion of a high-GI food, which will cause a smaller glycaemic response.

As foods are rarely consumed in isolation or in set quantities, the use of the glycaemic load will describe the glycaemic response more accurately. While general health recommendations for the population focus on the selection of foods with a lower GI to promote satiety and confer health benefits, for the athlete, knowledge of the GI of foods is also important for implementing nutrition plans to optimise performance. Meals before exercise focus on consuming low-GI foods to enable a sustained release of glucose in the blood. However, during and after exercise, high-GI foods are preferred to promote a quicker glycaemic response, allowing the absorbed glucose to be utilised for performance and to replace lost glucose respectively.

Satiety

The feeling of fullness and satisfaction after consuming food which inhibits the need to eat.

Recommended intakes and health effects of sugars

The NHMRC recommends that the percentage of energy derived from carbohydrates (CHO) should be in the range of 45–65 per cent of total energy (NHMRC et al. 2006). For an average person consuming 8700 kJ/day, this equates to 230–330 grams of CHO per day. This recommendation is not, however, used to determine the requirement for fuelling exercise and performance for athletes, which will be discussed in Chapter 10.

In 2015, the WHO recommended that free sugar intake should be less than ten per cent of total energy intake, and that further health benefits could be attained with a reduction to less than five per cent of dietary energy for adults and children (WHO 2015). For adults, this equates to about 20–25 g/day for the average person. Free sugars refers to the monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods and drinks by the food industry, as well as those incorporated in food preparation at home. It is important to note that this does not include foods that naturally contain these sugars, such as milk, fruit and some vegetables.

Sugars have been enjoyed in the diet for many centuries, as they provide sweetness and palatability (taste) to many foods; however, in recent years the intake of free or added sugars has increased significantly, leading to excessive intake and undesirable health outcomes. The impact of hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose levels) on cells and tissues in the body is also cause for concern. It is often difficult for the consumer to ascertain which foods contain sugars, as they assume various names on food labels, including brown sugar, raw sugar, corn sweeteners, corn syrup, dextrose, glucose, maltose, molasses, honey, or high-fructose corn syrup. An indirect impact of eating large amounts of added sugars is that they may replace other nutrient-rich foods and result in nutrient deficiencies. Foods such as lollies, cakes, biscuits, doughnuts, muffins and chocolate, and drinks such as sports drinks, soft drinks and fruit drinks, all have high amounts of added sugar with few other nutrients in them, so they are referred to as nutrient-poor. Of particular concern for the athlete is the quantity of sports drinks they may consume to enhance exercise performance, in terms of both general and dental health. Even, if they are ‘rinsing and spitting’, the sugar will stay in contact with their teeth for a period of time and can have a direct impact on the development of dental cavities.

Hyperglycaemia

Elevated blood glucose levels.

Nutrient-poor

A food or meal that has low content of nutrients relative to energy content.

ALCOHOL

Although consumed by some in the diet, alcohol is defined as a drug since it affects brain function. While alcohol can have some potential health benefits at low to moderate intakes, the harmful effects of alcohol, including accidental deaths, violence and motor vehicle accidents, generally outweighs any benefit. Alcohol causes on average 15 deaths and 430 hospitalisations every day in Australia and, in 2010, its misuse was estimated to cost Australia $36 billion (Manning et al. 2013). Therefore, any potential health benefit of alcohol has to be considered against the risk it poses to individuals and society. It is included in this chapter as it is a macronutrient, providing energy to the body (29 kJ/g); however, it is not necessary to include when planning diets and nutritional intakes for people, including athletes, due to the negative health and performance effects (discussed below).

Chemistry of alcohol

From the chemist’s perspective, alcohol refers to compounds containing a hydroxyl group (–OH), which include methanol, ethanol, isopropyl alcohol, glycerol, butanol and pentanol. However, for most people the term ‘alcohol’ is used to describe alcoholic beverages containing ethanol.

Alcohol (ethanol or ethyl alcohol) is a two-carbon compound, with five hydrogen and one hydroxyl group attached (C2H5OH). Alcohol, which provides 29 kJ/g, is normally consumed in alcoholic beverages, and the addition of any added sugars and fats along with the percentage of alcohol must therefore be taken into account when determining the kilojoules consumed. A standard drink—regardless of the concentration of ethanol it contains—is defined as containing 10 grams of alcohol.

Metabolism of alcohol

Ethanol is readily absorbed in the jejunum and is one of the few substances that is absorbed from the stomach. It is distributed evenly throughout the body fluids, as it moves across cellular membranes, including the blood–brain barrier, breast and placenta. As such, blood and all organ systems (including the brain, breast milk and the foetus) reach a peak concentration of alcohol very quickly after consumption. The majority of alcohol is metabolised in the liver, although a small percentage is metabolised as it passes through the stomach wall, which is known as first-pass metabolism. A small amount of alcohol is passed through the urine and some is excreted in the breath, which is why breath testing can be used to detect blood alcohol levels.

Alcohol can be metabolised via three pathways (Zakhari 2006). The major pathway is through alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver. Ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde, followed by the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase. The lack of this enzyme in some people leads to alcohol flush reaction (Asian flush), which is characterised by facial flushing, light-headedness, palpitations and nausea.

The second pathway for ethanol metabolism occurs in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER) system, and is referred to as the microsomal ethanol-oxidising system (MEOS) with cytochrome P450. The microsomes are induced on the ER after chronic alcohol consumption and, like alcohol dehydrogenase, ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde.

The third pathway for metabolism of ethanol to acetaldehyde is through an enzyme called catalase; however this is a very minor pathway, unless alcohol is consumed in a fasted state.

Ethanol is a depressant of the brain and nerve tissues (central nervous system) and affects a number of neurochemical processes, leading to an increased risk of suffering mental health problems, including alcohol dependence, depression and anxiety. Alcohol also impacts on other physiological processes in the body. Alcohol increases the risk of developing several chronic diseases (high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and liver disease) as well as certain cancers (mouth, throat, oesophageal, liver, colorectal and breast). Importantly, if consumed as part of after-game celebrations, alcohol can limit athletes’ ability to adhere to nutrition recovery plans (see Chapter 11).

Alcohol recommendations

Since alcohol does not provide any essential nutrients, and because it is also a drug, it is not listed in the NRVs (NHMRC 2009). However, the NHMRC has provided guidelines for consumption, which balance the health risks with any benefits.

Guideline 1: For healthy men and women, drinking no more than two standard drinks on any day reduces the lifetime risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury.

Guideline 2: For healthy men and women, drinking no more than four standard drinks on a single occasion reduces the risk of alcohol-related injury arising from that occasion.

Guideline 3: Parents and carers should be advised that children under 15 years of age are at the greatest risk of harm from drinking and that for this age group, not drinking alcohol is especially important. For young people aged 15−17 years, the safest option is to delay the initiation of drinking for as long as possible.

Guideline 4: For women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, not drinking is the safest option. For women who are breastfeeding, not drinking is the safest option.

SUMMARY AND KEY MESSAGES

The macronutrients, protein, fat and carbohydrate, play a key role in nutrition. They are metabolised to provide energy for the body and act as building blocks for cells, tissues and organs, and/or are precursors to essential hormones, immune mediators and enzymes. Alcohol, which provides energy, is not strictly considered a macronutrient as it also has drug-like properties in the body and can negatively affect health as well as sporting performance. While this chapter provides the background on macronutrients, it is important to remember that people eat food, not nutrients; the application of this nutritional information to food is presented in Chapter 6.

Key messages

• Carbohydrates are an important source of glucose for exercise and performance, but also supply essential B-group vitamins and fibre.

• Both protein and fat contain essential elements required to sustain life: the essential amino acids and essential fatty acids respectively, as well as other essential vitamins.

• The importance of protein and fat in the diet is reflected by their inclusion in the Nutrient Reference Values, which provide recommended intakes for all apparently healthy Australians.

• For athletes (as discussed in Chapter 10) these requirements need to be modified according to the athlete’s training and competition schedule.

REFERENCES

Dehghan, M., Mente, A., Zhang, X., et al., 2017, ‘Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): A prospective cohort study’, Lancet, vol. 390, no. 10107, pp. 20150–62.

Food Standards Australia and New Zealand, 2017, Trans Fatty Acids, Canberra, ACT: Food Standards Australia and New Zealand, retrieved from <www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/nutrition/transfat/Pages/default.aspx>.

Fowler, S.P., Williams, K., Resendez, R.G., et al., 2008, ‘Fueling the Obesity Epidemic? Artificially sweetened beverage use and long-term weight gain’, Obesity, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 1894–1900.

Hodgson, J.M., 2011, ‘Protein’ and ‘Digestion of food’, in Wahlqvist, M.L. (ed.), Food and Nutrition: Food and health systems in Australia and New Zealand, 3rd edn, Sydney, NSW: Allen & Unwin, pp. 295–327.

Jones, G.P. & Hodgson, J.M., 2011, ‘Carbohydrates’ and ‘Fats’, in Wahlqvist, M.L. (ed.), Food and Nutrition: Food and health systems in Australia and New Zealand, 3rd edn, Sydney, NSW: Allen & Unwin, pp. 268–94.

Manning, M., Smith, C. & Mazerolle, P., 2013, The Societal Costs of Alcohol Misuse in Australia, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, No. 454, Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Criminology.

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2006, Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand, Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

National Health and Medical Research Council, 2009, Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol, Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013, Australian Dietary Guidelines, Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

World Health Organization (WHO), 2015, Guideline: Sugar Intake for Adults and Children, Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zakhari, S., 2006, ‘Overview: How is alcohol metabolized in the body?’, Alcohol Research and Health, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 245–54.