I STARTED SLOWLY during the 2000 training camp but was out of the slump by the middle of October. In our third game of the season, I scored twice against the Pittsburgh Penguins. We lost 8–6, but it was a high-tempo contest. Our coach, Ronny Low, made you earn your ice time, and he was giving me more than any other forward, about twenty minutes per game. He also put me on the right point on power plays. My confidence was building.

But by the end of the month, I was in Low’s doghouse. During another game against Pittsburgh, we were down 3–1 and I got called for slashing. Low told the New York Post he was concerned about my taking penalties in the offensive zone and he put me on the fourth line. I mean, shit, nine games into the season and I already had five goals and he was worried about penalties? I had to survive out there somehow. I went out in the next game against the Bruins and scored a shorthander and chipped in an assist. We won it, 5–1. On November 1, I scored three goals and assisted on the game-winner against Tampa Bay. Then we beat Montreal a couple of days later, and I opened the scoring. That goal gave me 11 in 13 games and made me the sixtieth player in NHL history to score 400 regular-season goals in his career.

On November 18, we played the Flames at the Saddledome—only my second time there since leaving. It was Josh’s 12th birthday, so we arranged for him to bring his friends to a skybox. I assisted in the first period and scored on a shorthanded breakaway at the start of the second.

The game was tied at four and we were headed for overtime when, with five seconds left in the third, I got called for roughing. I just snapped. I wanted to choke the ref, Dan Marouelli. Throughout the game, Toni Lydman had been hooking and holding because that’s the only way you could stop me, and Marouelli was oblivious to it. Of course, I got frustrated. I saw him as a typical NHL ref, wanting to control the outcome of the game. He added a ten-minute misconduct, so I was done for the game. Fortunately, Valeri Kamensky scored at 2:44 of OT, so we won.

MEANWHILE, as per the substance abuse program, I had to provide urine samples from time to time, but since I was still out partying, they were consistently dirty. I was putting Gatorade in the test samples. Sometimes I’d use other people’s pee, sometimes even Beaux’s. Dr. Shaw and Dr. Lewis kept warning me. Countless times, I would get the call—“If you continue this behaviour, we’re going to have to pull you out.” Did I believe them? No. I was one of the highest-scoring players in the NHL. What were they going to do?

Occasionally, I’d ease up. If my buddy Chuck Matson came to visit, it helped. Slats used to love it when Chuck was around, because I always played better. I got two goals and an assist in one game, and Slats stopped Chuck in the hall and said, “Hey, Matson, you should come by more often.” And then I got a goal and an assist in the next game, and Slats saw Chuck and said, “Hey, Mats, I think you should move down here and live with Theo.” Chuck said, “Yeah, you can tell my wife that’s gonna happen.” In the game after that, I got three assists. Slats walked past Chuck and me as we were leaving, then turned around and said, “Matson, what’s your wife’s number?”

But most of the time I didn’t have any friends like Chuck around for support. I was alone. Number one and alone. And every time I got to the top, I fucked it all up because I didn’t like being there. Maybe I felt that I didn’t deserve it. And I had huge problems with being alone—it was like I couldn’t have a relationship with myself. The funny thing is, the higher I rose in society, the more alone I became. Why? Because I was treated differently and dehumanized. I knew that half the time people were nice to me because I had money or I was a hockey star. I had become addicted to cocaine. The only days I wasn’t doing it were game days. My new routine was sleep, play the game, party till 6 a.m., go to practice, come home and sleep around the clock till the next day. Alcohol and drugs stopped the anxiety attacks and took away the worry, shame and guilt. When I was blasted I was happy, and when I was happy I played great hockey.

And I was playing awesome. On February 12, 2001, The New York Times wrote an article with the headline “Fleury Continues Impressive Comeback.” The article said, “There can be no argument that Fleury, who is in his second year with the Rangers, is critical to any chance the Rangers have of salvaging their playoff hopes.” Mark Messier, who had been on my line for the past couple of games, was quoted as saying, “That’s the kind of year he’s had, though. He’s played hard, scored big goals for us, played in every situation, and played unbelievably consistent for us all year. He had another big goal for us tonight.”

WITH SIX WEEKS left in the season, we were eight points behind Boston and Carolina for the last playoff spot in the Eastern Conference, but still hoping to catch up. I was fourth in the NHL in scoring with 30 goals and 44 assists for 74 points, trailing only Joe Sakic,Jaromír Jágr and Alexei Kovalev. Then the fuckin’ NHL Substance Abuse Program decided that thirteen dirty pee tests were enough, and it was announced that I had voluntarily entered the substance abuse and behavioral health program run jointly by the NHL and the players’ association. Voluntarily? Well I guess that depends on your definition of the word.

The pee test guys showed up after our game against Ottawa on February 26, and I was still out partying. Dan Cronin was trying to get hold of me. Finally, he called and said, “Pack your stuff, you are going to L.A.” My season went tits-up.

Everything had been going so well on the ice. I was playing great. I guess it was just another example of me self-sabotaging something that was good. And I’d been warned, I had been warned.

I went home and sat on our bed and cried and howled like a wounded animal for six hours straight. Just raw emotion. Thirty-two years of everything that was shitty kind of poured out all at once. I loved playing hockey so much—when you took that away, what was left? And I had let the Rangers down.

Glen Sather called me before the flight. I am sure he felt like he had been hit in the side of the head with a baseball bat, because he didn’t see it coming. Why hadn’t I turned to him? I felt really badly, and I think he would have helped me if I had gone to him. And to top it all off, our goalie, Mike Richter, was out with a blown anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in his right knee.

I needed to be able to deal with pain without using drugs, so I was sent for treatment at the Promises Westside Residential Treatment Center in California. I found it interesting that Dr. Lewis worked for the NHL Substance Abuse Program, yet he was also on the staff of the facility he sent the players to. The facility was garbage in my opinion—crappy, bland food, ugly, cheap furniture and the beds were shit.

One day, Dr. Lewis came in and said, “You need to start working out.” Fuck you, I thought. He said, “There are a bunch of us going boxing tonight, why don’t you come along?” He was such a dickhead. We just didn’t get along—I rubbed him the wrong way and he rubbed me the wrong way. I don’t know which one of us had a bigger ego, but I thought he was such a poser. He had your typical California tan with a full head of beach-boy blond hair. He was in his late 40s, but to me it looked like he had work done on his face.

Playing in New York: insanity reigned supreme.

COURTESY DAVE SANDFORD/HOCKEY HALL OF FAME

Being traded from the Flames to the Avalanche was the beginning of the end.

COURTESY DAVID E. KLUTHO/HOCKEY HALL OF FAME

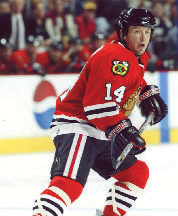

I think it’s fair to say that when I chose to go to Chicago I miscalculated the outcome.

COURTESY THE CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS

I am one of twenty-three Canadian players in sixty years with an Olympic gold medal in men’s hockey.

COURTESY DAVE SANDFORD/HOCKEY HALL OF FAME

Paying the price.

Chuck Matson was my conscience when I didn’t have one.

COURTESY CHUCK MATSON

With Wayne Gretzky at the 1992 all-star game in Philadelphia.

COURTESY SHANNON GRIFFIN-WHITE

With Josh and Kelly Buchberger. Kelly is a great guy to have on your team.

I wasn’t always Don Cherry’s biggest fan.

Garth Brooks, the biggest star on the planet—next to me.

COURTESY SHANNON GRIFFIN-W HITE

Ted (left), Travis and me (in the Harley-Davidson vest), with our dad, Wally. Family is the most important thing in life. Between the four of us, we have 50 years of sobriety.

With Graham James.

This is the mugshot taken in New Mexico when I was arrested for losing it on Steph. The Big Book of AA warns that if you don’t get sober, you’ll end up either in jail, or in another kind of institution or dead.

With my daughter Skylah at the 2009 Allan Cup. Skylah eased the pain of the loss.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Bo Jackson, eat your heart out. Here, I suit up for the first of two pro games with the independent Calgary Vipers of the Northern League in the summer of 2008.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

Playing for the Steinbach North Stars (Manitoba) versus the Dundas Real McCoys in the quarter-finals for the 2009 Allan Cup. I wore #74.

COURTESY KIRSTIE MCLELLAN DAY

With Jenn at Giant’s Causeway, Belfast, Ireland. Serenity at last.

COURTESY MICHAEL COOPER PHOTOGRAPHY

My wedding to Jenn, August 19, 2006. I finally know how “forever” feels.

COURTESY PERRY THOMPSON PHOTOGRAPHY

I said, “As long as you put the headgear on and go three rounds with me, I am in. I am all in.” He said, “Well, I won’t be doing that.” Fuckin’ chickenshit. Not that I blame him—I would have killed the guy. Still, since it meant a chance to earn some brownie points, I said okay. They put me in the ring and I was hitting the guy holding up the punching pads so hard that I was lifting him right off the canvas—I was that mad. Dr. Lewis was looking at me, and I figured he was thinking, “What the hell? This guy is a psycho.”

I WAS SICK with guilt over letting my team down. And on March 6, 2001, when I had been in treatment for a week, I heard about the Rangers’ embarrassing 5–2 loss to the Islanders at the Garden. We were out of the playoffs.

MEANWHILE, I would check my bank statement every day to keep track of where my money was going. I called home, and Veronica was not there. My brother Travis was babysitting the kids. Veronica had gone on vacation. First she went to the Bahamas for her birthday, then she went down to Florida with all the wives for the April 7 game against the Panthers. “Fuck it,” I said. I couldn’t worry about it. I had to concentrate on my own shit.

At the treatment centre, Dr. Lewis started me on the antidepressant Effexor. I was already overstimulated, not depressed or suicidal, so the Effexor just ramped everything up. I felt like I was on speed. I worked with the therapists on why I was so good at beating myself up. We did some inner-child stuff. In one exercise, they put a pen in my right hand—I had become ambidextrous after the skate blade accident when I was 13, but I usually write left-handed. The stuff I wrote represented my inner child, and it was talking to the adult in me. It said, “I’m okay, I’ve always been okay, you have always taken care of me.” It was an exercise that truly put into perspective what kind of person I was, despite all the shit. At my core, I’m a caring guy. If I see a weaker person, I try to help them. So the doctors wanted me to learn to be that way with myself. In our society, we don’t teach people how to like themselves. I had to learn that.

And then I did equine therapy. We went on a field trip to a big farm with horses all over the place. You go into a ring with a horse. The idea is that you have to get the horse to trust you. So the first thing you do is stand right in front of the horse so that it picks up on your energy and whatever. Before it was my turn, we had a chance to sit in the grandstand and observe what was going on. The first couple of people were tugging on the reins and the horse wouldn’t move. And then it was my turn, and I swear to God I could have walked back to the treatment centre and that horse wouldn’t have left my side. I didn’t have any trouble getting him to trust me, I just started walking. I didn’t even touch the reins. We just walked around the circle and he put his nose over my shoulder, nudging me, kissing me. It was pretty powerful stuff. It gave me such positive affirmation that I was a good guy. One worth trusting. Once you surrender, the sky is the limit.

The next stop was a treatment centre that specialized in trauma. It was called the Life Healing Center of Santa Fe. There, I broke the record for going to the most AA meetings. In thirty days, I’ll bet I went to ninety meetings. You could go at lunch and you could go for two meetings at night, so I was hitting three a day. I felt it was my duty to try to get my shit together, because I had let a lot of people down in New York.

Some of what they told me was helpful, and some was just fuckin’ ridiculous. They told me that I cheated on Veronica so much because I had a “sex addiction.” They said it was triggered “when client is alone after games on the road [and] he and his wife would argue.” Well, if that is true, then it turns out a lot of sex addicts play hockey.

Chuck came down to visit. He had never been to a treatment centre before. Dan Cronin picked him up at the airport and they spent half a day together. Chuck thought I was one of a random few guys in the NHL who had trouble, but when he saw that Dan had two cell phones, with two lines on each, ringing nonstop he realized I was not alone. Chuck said to me, “Bones, you would not believe who was on the other end talking about their troubles—the whole freakin’ league!”

At the centre I introduced Chuck to a super-rich guy. Cocaine had made him so paranoid he was found holed up in the master bath of his humungous home with a lampshade on his head surrounded by cornflakes so he could hear anyone who tried to break in. His nose had an actual hole in the cartilage and he would slip a straw through it to make us laugh. Before coming to the centre he had had diplomatic immunity so he was making regular flights in his private jet to Colombia to pick up coke. The place was full of characters.

The substance abuse program “contract” required that I have a sponsor—“I will obtain and work with a twelve-step sponsor in my hometown.” There was a meeting at a church on a Tuesday night. I loved going to the meetings. There was lots of good sobriety there, lots of great people. I was outside having a cigarette, and this little fat guy comes walking by and he’s got a Detroit Red Wings hat on. I thought, “We’re in Santa Fe. The only ice here is in a glass.” So I walked up to him and said, “How’re you doing?” I didn’t tell him who I was. I said, “You’re a big Detroit Red Wings fan?” He said, “Oh, I’m the biggest Detroit fan. I love Steve Yzerman.” And I stuck out my hand, “Well hi, I’m Theo Fleury.” He fuckin’ lost it! He said, “I read about you! This is where you are? You’re here!” I said, “Yeah, I’m in the treatment centre on the south side of town.” He introduced himself. His name was Jim Jenkins, JJ for short. We talked hockey for quite a while, and at the end of the conversation I said, “Okay, man, one of the requirements is for me to get a sponsor while I’m in treatment here. Are you willing to be my sponsor?” He refused. I said, “What do you mean, ‘No’?”

“Are you ready? Are you really ready?” he asked. “Because I’ve seen guys like you. Lots of guys like you.” Jim had done all kinds of things. He had been a professional race-car driver. Honest to God, he was fuckin’ crazier than I was. He told me a story about how he had his four kids in his airplane while he was fucked up on Quaaludes and blow and all kinds of shit. They were up in the Rockies, and he looked over at his 12-year-old kid and said, “Take over, I’m done,” and passed out. And his kid landed the fuckin’ plane.

He finally agreed to be my sponsor. So he met me at the treatment centre the next day and we started reading Alcoholics Anonymous’s Big Book together, and we hung out and made sure we were at the same meetings.

I had a therapist who tried to help me one on one. I had told her about what Graham had done to me, and whenever she brought it up I would just check out. She literally had to shake me to bring me back into the room. So they put me in a group. This group really opened my eyes to the crazy shit that people do to each other. There were people who had serious, nasty awful things done to them, and the only way they could face life is by shooting ecstasy, taking heroin or becoming obsessed with relationships and sex.

It was the first time I had ever dealt with the abuse head-on, the first time I could sit in a group and talk about anything. I was hearing some pretty fuckin’ wild stuff, so when I told my story it didn’t feel so bad.

Toward the end of the thirty days in New Mexico, I was getting ready to go back to treatment at Westside for two weeks to complete the program. But I found that I had connected with Santa Fe—I loved the desert. Jim and I drove out to a community called Las Campanas. It was gorgeous—two Jack Nicklaus golf courses, equestrian facilities, a spa. It was like walking into a picture of Heaven.

I got out of the car and stood at the edge of the road feeling a sense of peace I hadn’t experienced since serving Mass at St. Joe’s with Father Paul. The hills were covered in cactus and purple and green sage. But the thing that really got me was the light. The sky was big, it met the ground in the distance and the clouds looked like bags of feathers. I remember taking a deep breath of that cool, dry mountain air, and suddenly something clicked in my head. I said to myself, “You’ve got to move here. You feel safe. Everything is going well. You’ve got a good program started. If you leave, what might happen?”

I asked JJ, “Do you know a real estate agent?” and he said, “Yeah, my sister-in-law.” I called Veronica, and she flew down the next day. We found a place. It cost about $1.2 million and it was an awesome place—one of those adobe-style homes, with heated brick floors and a 600-square-foot guesthouse. Just gorgeous. You could see the Sangre de Cristo Mountains from the front of my house. I had two acres that backed onto the sixth hole of the Sunrise Golf Course, which was 7,626 yards of golf from the longest tees.

I called Don Baizley and said, “I’m moving to Santa Fe!” He said, “What the hell?” I said, “I feel safe here and I’ve got a sponsor.” I was feeling pretty good about myself and was determined to get ready for the next season as I settled into my new place. It was a retirement community, and I was probably the youngest member at that golf course by about thirty years. I met this really cool guy named Claude, who had been in the insurance business. We became good friends and golfing buddies. I got into a really good routine. I’d get up in the morning, work out, have lunch, Claude would pick me up and we would play thirty-six holes. From there, we’d have a bite to eat and then I’d go to a meeting that night. It was perfect.

Veronica came back and stayed with me in Santa Fe for two weeks, but she couldn’t handle it. We were in the middle of the desert, with no friends, no family, no nothing. I thought we could start to repair the damage by getting away from her family and just being together with the kids. But there was too much history between us. She said, “I’m going back to Sicamous,” and I said, “Well, I’m staying here.” I was getting better, and she was used to chaos.

I had a second motivation for getting better—the Olympics. I wanted to be a part of the team that would represent Canada in 2002 at Salt Lake City. I was on the team that had failed in Nagano and wanted another chance. Due to my recent history, it was going to take an extraordinary effort for me to make that team. One morning, I was sitting at the big granite island in my kitchen when the phone rang. I said, “Hello?”

“Hey, Theo, it’s Wayne.”

“Wayne who?”

“It’s Wayne Gretzky.”

“Oh, how’s it going, man?” I said.

“Well, good,” he said. “You know I’m running the Olympic team for 2002. I understand that you’ve had a really good summer and you’ve got some things straightened around. I think it would be a pretty good idea if you came and joined us in Calgary for the camp.”

“What? You want me to come there?”

“Absolutely. We think that you’re going to be a huge part of the team this year at the Olympics.” And I said, “Holy fuck,” you know?