THE APPROACH OF Edison’s fifty-third birthday, otherwise agreeably given over to freezing liquid carbonic acid at different soda strengths, was spoiled by a letter from his son William, a shifty Yale dropout who had promised, only a few months before, never to “darken the doors of your house again.”1

Recently married to a young woman of “fast” reputation, whom Edison refused to receive, William wrote that they were living in New York and had “gained quite an axcess to society.” All that was lacking to complete their happiness was an invitation to visit Glenmont. “Just for an evening that is all I ask….I may have been a disobedient son but hardly a bad or worthless one.”

In Edison’s opinion, William merited all three adjectives. And his wife, Blanche, a Delaware doctor’s daughter, was a spendthrift. No doubt the couple had worked through what little money William had inherited from the estate of Mary Edison, and now wanted “axcess” to some funds on his father’s side. They assumed, as everyone did, that Edison was rich. In fact, his finances were seriously strained. Having squandered well over $2 million on an iron mine in the New Jersey highlands and sunk half a million more into a gold mine at Ortiz, New Mexico, he was in no mood to reinstate William on the list of his many dependents—along with Tom, another wastrel, with a wife even “faster” than Blanche.2

They were boys no longer, at twenty-two and twenty-four, respectively,*1 and cared little that their father had a second, much younger family to support. Their demands on him—William’s alternately abusive and conniving, Tom’s querulous and self-pitying—were so continual that he relied on Mina to keep them off his back. Had she brought them up lovingly, rather than with a sort of dutiful affection, their vague memories of Mary might have been subsumed under a much more vivid experience of another “Mother.” But try as she might, Mina could not conceal a natural preference for the flesh of her own flesh. Looking past her for a true sense of identity, they distantly perceived their father. He loomed as the only constant on their horizon, a mountain of familiar mass. Except that whenever they approached, it receded or faded. Was there, in fact, any father there?

Charles and Madeleine had no such confusion, and neither would Theodore when he grew older. Taking for granted the love of their parents for each other and for them, they accepted Edison’s long absences from Glenmont as part of its domestic rhythm, just as they forgave him at home for being too deaf, or too abstracted, to pay them much heed. In a stream-of-consciousness letter written from MIT years later, Charles waxed nostalgic for the family circle that had never fully embraced his step-siblings:

The sitting room, is it still as it was I wonder, the big window that looks out over the frosty lawn the litter of toys under it, the big table the fine old lounge. The moonlight just visible thru the high north windows as it filters thru the moving branches of the big maple tree. The canal coal burning brightly in the fireplace and near it the chair with the big glass lamp above it and in it the most widely respected loved and honored man in the world, reading, the pile of magazines on the floor, the leather covered books on the small table near the door, the chair beside it and the little foot stool and you, mother, in it….And in the old south room the sister writing, writing, writing and the great dignified drawing room with its piano and the tall vase of american beauties or poppy flowers—nothing else—and the soft alabaster lamp in the drawing room….The quiet dining room with its chilly exedra and the big uncomfortable den, the phonograph in Theodore’s room and the white linen & bunch of red roses in my room and everywhere the touch & thought of one person and all the things I have dreamed of seeing again after all these years.3

Madeleine shared Charles’s adoration of Mina. They realized that her need to be assured of their love, regularly and often, was insatiable. And yet no amount of hyperbole could stave off her black depressions, which became more frequent as she grew older. She was the daughter of an inventor married to an inventor and could not shake off the neurosis that Edison cared more for his laboratory than her.

Edison’s chair and lamp in the sitting room at Glenmont, circa 1900s.

At thirty-four, she had long lost the teenage sexiness that had captivated him in the summer of ’85 (“Got thinking about Mina and came near being run over by a street car”). Her firm contours had softened to plumpness, and her almost Indian “Maid of Chautauqua” glow was dulled by too much domesticity and too few winter vacations. She was by no means an overworked housewife, having a staff of eleven to keep the mansion clean, plush, and polished, her table loaded with food (but no wine—she disapproved of alcohol), and the estate and greenhouse immaculate.4 Private schools and French governesses educated her children,*2 and a coachman and carriage were always on hand to drive her to ladies’ luncheons and meetings of the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Edison gave her a generous personal allowance, so she wore expensively dowdy clothes and could afford the best boxes at any opera or ball in New York.

For all these trappings and comforts of privilege, there was a grimness about Mina, buttressed by her staunch Methodism. She could not understand jokes, frowned on dancing and décolleté gowns, and deplored Edison’s cheerful agnosticism. Every August she attended the Chautauqua Assembly, the dour adult-improvement festival her father had co-founded in upstate New York, to soothe her melancholy at spiritual concerts and lectures on such subjects as “The Problem of Suffering” and “The Teaching of Jesus Concerning the Industrial Order.”5

It followed that she was horrified that boozy Tom had gone the way of so many millionaires’ sons and married a blond showgirl, Marie Louise Toohey. Nor could she forgive William for telling Edison, “I could never love, [or] even like my stepmother….I look upon her as the one who ruined our happiness.”6

“NO ANS”

Edison’s way of dealing with importuning mail—a substantial portion of the three thousand letters he received every year—was to scribble “No Ans” across the top of the first sheet. (Usually it was on the second that money was first mentioned.) He would leave it to his secretary, John Randolph, to decide if the supplicant at least merited a polite expression of regret. Randolph was good at trashing mail from religious maniacs, or desolate “widows” with masculine handwriting. But he felt less comfortable ignoring letters from Tom or William, even when Edison—a soft touch before they came of age—periodically threatened to cut their allowances for misbehaving. The secretary had emotional problems of his own, and could not help feeling sorry for them. Since his was, as it were, the only voice they heard in response to their appeals, and since he was the one who made out Edison’s checks, they began to treat “Johnny” as an ally who might prevail on their father when they could not.

The question for Edison in the spring of 1900 was how to get both sons settled as far as possible from the fleshpots of New York. That became an urgent priority after William sent Mina a letter that came close to a threat of physical violence, and the yellow press described Tom and Marie (“late a splendid figure in pure pink meshings on the stage of the Casino”) guzzling champagne frappé de glace at the Arion Ball in Madison Square Garden.7

Edison was less disturbed by that than by the way Tom, talking to newsmen, posed as his inventive heir apparent. “Reared in my father’s own laboratory and educated by my father himself, I think I am capable of continuing the work which he will perhaps not live to finish.” Randolph reported with annoying frequency that the young man was bouncing checks and selling his surname to all comers.8

Thomas Alva Edison, Jr., circa 1900.

On 9 May a flyer arrived at the laboratory announcing the appointment of Thomas A. Edison, Jr., as “consulting expert” to a new “International Bureau of Science and Invention,” with offices in New York, London, and Paris. “The company’s skilled technicians stood ready to “examine and look into any idea or ideas submitted to us (as per blank enclosed), giving their opinion of same, and if necessary making suggestions toward improvement.” The bureau would help patent “any good invention” that resulted, in return for a two-thirds share of all subsequent profits. Its general manager, A. A. Friedenstein, addressed a postscript to Edison saying Tom had assured him that “the above scheme had been endorsed by you. If so, would you kindly advise me to that effect, as I would not care to invest any money in any matter that was not strictly O.K.”9

Having for years read similar missives touting the Edison Junior Improved Incandescent Lamp, the Thomas A. Edison Jr. & Wm. Holzer Steel & Iron Process Company, the Edison-Rogers Photoscope Company, and the Thomas A. Edison Jr. Chemical Company (not to mention Dr. Edison’s Obesity Pills and the Edison Electric Belt, which cured “all the ailments peculiar to women” by restoring strength to their “delicate organs”), Edison referred Friedenstein’s pitch to a lawyer and turned to the construction of an invention more typical of himself, the longest rotary cement-burning kiln in the world.10

AN ENTIRELY NEW VOLTAIC COMBINATION

One day that May Edison stood on the west side of Manhattan, waiting for the Cortlandt Street ferry to Jersey City. Just two blocks away was Smith & McNell’s restaurant, where once, famished, he had spent his last few coins on a plate of apple dumplings, a cup of coffee, and a cigar. It was the most delicious banquet in his memory, better than any he had subsequently been able to afford at Delmonico’s. The dumplings were still available (at $2.95), and every now and again he would recommend them to a friend as “the finest you have ever had.”11

All these years later, the streets he had lit jostled with horse-drawn traffic—overcrammed carts, cursing teamsters, and dogged drays whose manure and urine filled the air with such a miasma that a man needed the strongest cigar possible to counteract it. If New York was this jammed so early in the century, how long before it groaned to a standstill?12 For two hours Edison jotted remedial ideas in his notebook.

Limited loads. Congestion. Resulting delay and expense therefrom….

Solution:—Electrically driven trucks, covering one-half the street area, having twice the speed, with two or three times the carrying capacity….Development necessary:—Running gear—easy. Motor driver—easy. Control—simple. Battery—(?)13

Electric trucks and automobiles, as opposed to trolleyed streetcars and trains, depended on the lead-acid storage battery. It was thrillingly silent, but the payoff was a tire-flattening weight of lead plates, not to mention cells full of corrosive fluid sloshing between negative and positive poles, emitting an odor almost as acrid as horse piss. There were two alternatives, each with its own liabilities. Gasoline-powered vehicles were hard to start (their engines had to be hand-cranked into life, and could break a man’s arm on the kickback) and laborious to drive, and called for crunching gear changes whenever they sped up or slowed down. In addition they were smoky and blaringly loud. Steam engine cars had to be water filled with annoying frequency, and in winter they took as long as forty-five minutes to warm up.*3 Being at least powerful, once they started puffing, they dominated the majority of the nation’s eight thousand–vehicle “horseless carriage” market. But until one or another drive mode was made both practical and cheap, there was unlikely to be much lessening of the amount of manure on city roads.14

Edison’s Cortlandt Street notebook indicated a willingness to bet that gearless, nonpolluting electric power would win out—if not for automobiles, at least for delivery trucks and cabs. What he had to do was to invent a reversible galvanic cell that was dramatically lighter and cheaper. It should compete with the high energy density of gasoline and be as clean as steam. It should generate current without surges or slumps, and enable many miles of traction before a recharge was necessary. It should tolerate short-circuits, rough riding over country roads, overcharges, and reductions to zero voltage. Admittedly these were huge imponderables, but his nature was to rise to such challenges. After ten years of carving up and crushing mountains, the scientist in him longed for a return to the atomic logic of electrochemistry.15

He refused to accept the shibboleth that lead, iron, and sulfuric acid were the only reagents that would ever generate enough current to move a car independently. It was “very beautiful in theory” but flawed in practice “because of the inherent destructive influence” of its liquid electrolyte.16 At best, the massing of six or eight lead-lined, hard rubber cells*4 per vehicle caused a 15 percent loss of efficiency. Maintaining anything like that ratio for long required more skill and patience than most “automobilists” possessed—not to mention strength in lifting dud units out, a job that usually required two men. “If Nature had intended to use lead in batteries for powering vehicles,” Edison declared, “she would not have made it so heavy.”17

Without realizing that the question mark at the end of his Cortlandt Street notes portended the most agonizingly difficult project of his career, he began to look for an electrochemical yin-yang, a perfect counterbalance of positive and negative, attraction and repulsion, charge and recharge, and energy to mass, that surely existed somewhere in “Nature.”18 If not yet achieved, it was implicit in the primary battery invented a hundred years before by Alessandro Volta, the father of applied electricity: a cylindrical pile of acid-soaked cardboard disks, alternately separating thick medallions of silver and zinc, or copper and zinc. The damp layers reacted with the metal layers, generating a flow of power through the cell, from positive anode to negative cathode, the moment it was connected to an outside conductor. While copious, the flow was irreversible, draining away until the cell “died.”

Gaston Planté’s invention in 1859 of a secondary lead-acid battery that stored infusions of outside current amounted to a technological innovation almost as great as Volta’s. As a boy chemist and teenage electrician, Edison had shocked and burned himself into an intimate understanding of both kinds of cells. But in adulthood, after nearly disfiguring his face with a splash of nitric acid, he had wondered about the feasibility of a reversible traction battery filled with an alkaline electrolyte, perhaps doing away with plate electrodes altogether, so as not to waste its energy on the movement of dense metal.19

He took his first step toward this radical idea in 1889, when he manufactured an improvement to the Lalande-Chaperon cell, a primary battery that counterposed electrodes of positive zinc and negative iron in an aqueous solution of potassium hydroxide.*5 Its closed construction inhibited evaporation of the electrolyte and encouraged him to believe that a cell just as noncorrosive might be made rechargeable by an outside dynamo. To that end, for almost a year, he had been conducting regenerative experiments with copper oxide electrodes, dunking them into caustic solutions of varying strength. The results were unsatisfactory, because the copper either oxidized too much or would not reverse at all. He was to try fifty other combinations of metals and minerals, looking for “an entirely new voltaic combination,” before the summer of 1900 was out.20

“LOVE IS A FOREIGN THING”

In their different ways of operating, Edison’s two eldest sons ludicrously resembled the poles of a malfunctioning storage battery. Tom was the corrosible negative element, doomed to attract clinging ions like Mr. Friedlander, while William was the hard end, pulsing out a wild spray of electrons that sometimes threatened an explosion. Anything could touch him off—an imagined slight, a rumor, a landlord’s demand for arrears—and just as quickly he could be moved to effusive declarations of love or good intent. He was as needy as his brother, but whereas Tom craved affection more than money, to William a check would always suffice.

Somehow in July Tom got the idea that his expectations as the son of an industrial tycoon were misplaced. Instantly he suspected a plot fomented by Mina to disinherit him.21 His paranoia was plain in a letter received by Walter Mallory, the large, lugubrious engineer who ran the Edison Portland Cement Company.

Will you be so kind as to let me know as soon as possible whether my father has disinherited me or not….

It is Mrs. Edison and a few of his friends? who have been instrumental in this matter….Love is a foreign thing to my father but the world will know the true state of affairs pretty soon. Lies have been told him about me and my wife and he believes me [sic]—Let him do so but by God he will regret it and I will show him and the Miller gang that there is one son who is not a fop.22

So much for poor Tom, who draped his spindly body in elegant suits and wore high stiff collars to hide an attenuated neck. (William, in contrast, looked like a middleweight wanting to strip and fight.) The “Miller gang” were Mina’s clannish relatives, who had always looked down on her stepfamily.

William went on to complain about the annoyance of having to earn a living. He was running an automobile agency in Washington, D.C., and not doing at all well:

I am compelled to seek a job as my meagre income is not suitable for my maintenance. My father if he was a true father would certainly look after my welfare. He never takes the trouble to find out whether I am dead or alive but I’ll tell you what Mallory…I am tired of all this business and something dirty is going to happen before I meet my length in soil.23

Mallory forwarded the letter to his boss, who for some time had been allowing William $2,160 a year, more than the average salary of a college professor.*6 Edison ignored it, but when Blanche followed up with a hysterically scrawled six-page screed saying that the children of “The Greatest Man of the Century” should not have to live in such poverty, he permitted himself a rare show of anger.

I see no reason whatever why I should support my son, he has done me no honor, and has brought the blush of shame to my cheeks many a time. In fact he has at times hurt my feelings beyond measure. For more than fifteen years I supported my family on less than two thousand a year, & we lived well and after allowing you as much as I do monthly to have you talk in the way you do shows an utter lack of gratitude. Let your husband earn his money like I did. I will continue to send the monthly installment until such a time but in no case will I loan any more money or increase the monthly amount.24

ALL MY DUCATS

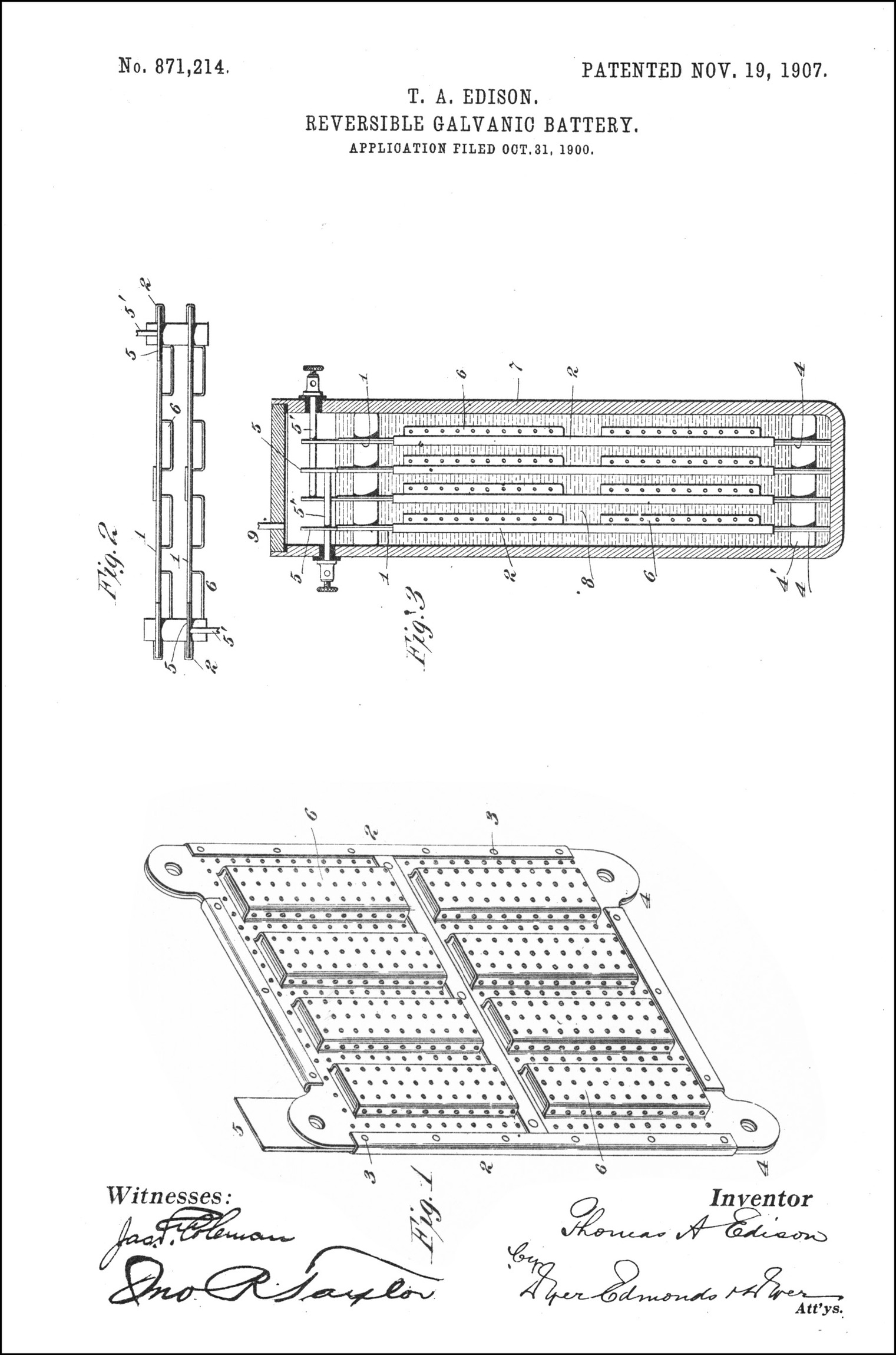

In October Edison’s first two patents covering “new and useful improvements in reversible galvanic cells or so-called ‘storage batteries’ ” heralded his self-rediscovery as a chemist just when he had to accept that he would never become another Andrew Carnegie. The hard economics of mining and milling forced him to abandon his expensive new venture in New Mexico, where the gold sand was too poor to process, and simultaneously close the iron-extraction plant he and Mallory had built at Ogdensburg, New Jersey, with grandiloquent hopes, nine years before.25

Henceforth, apart from a scheme they had to adapt his long kiln and leftover Ogdensburg machinery to manufacture portland cement, Edison intended to spend as much time as possible with test tubes and galvanometers: “I am putting all my ducats in the storage battery.”26

The patent applications made clear that he did not expect early success. He wrote that he had improved the performance of an alkaline cell by using the absolute neutrality of magnesium to prevent zinc being “deposited in spongy form” on the negative electrode during recharge. Instead, he got sizable clumps of it if the latter element was copper oxide. But zinc itself was the problem. It was simply too soluble in an alkaline solution, the clumps tending to degrade after a while, rapidly reducing discharge capacity, as “other experimenters with batteries of this type” had already found.27

The last statement would return to haunt Edison. It suggested familiarity with the work of an obscure Swedish scientist, Ernst Waldemar Jungner, whose development of an alkaline automobile “accumulator” was so similar and so simultaneous with his as to arouse suspicions of mutual espionage—were they not separated by two oceans and multiple barriers of language. Jungner, too, had invented a variant of the Lalande battery some years back, and his first alkaline silver-cadmium cell had been patented in Germany on 26 August 1899, about two months after Edison began testing polarizations of zinc and copper in solutions of caustic potash. Around the same time Jungner had also applied for, but not yet received, an American patent for his basic battery.28

If Edison had any detailed knowledge of it at the time he executed his own first application, he would have to have read a recent article by Jungner in Elektrochemische Zeitschrift, forbiddingly entitled “Ein primär wie sekundär benutzbares galvanisches Element mit Elektrolyten von unveränderlichen Leitungsvermögen.” This was not implausible, because he subscribed to a sister publication, Elektrotechnische Zeitschrift, and employed translators to help him keep up to date with foreign innovation.29

At any rate, the second of his 15 October patent applications showed a sophisticated understanding of cadmium-element electrochemistry, along with pride that he had conquered a problem that had defeated all “previous experimenters.”30 In language of the utmost precision, Edison described an invention more complex than any he had devised since his quadruplex telegraph of 1874. Its construction began with the rolling and annealing of two thin, rectangular nickel plates that were lugged to face each other, like infinity mirrors, once they had been respectively impregnated with elements of cadmium and copper. To that end he polished them with red heat and hydrogen before attaching the pockets—nickel too, and flat—to keep the cell as elegantly slim as possible.

The pockets and plates were perforated for later immersion in alkaline liquid. Next came the extremely intricate process of preparing two metallic powders to fill the pockets. One, for the positive plate, consisted of finely divided cadmium; the other, for the negative, was a similar division of copper oxide. Although so far the assembly of the cell had been a counterposing of opposites, the elements had to be manufactured differently. He obtained his cadmium by electrodeposition onto a platinum cathode, peeling off from it ribbons “exceedingly finely divided and filamentary in form, and of great purity.” He washed them in water to remove any trace of residual sulfate, then packed the filaments into the pockets—tightly enough to give them “coherence” yet not so tightly that the pocket lost porosity.

Illustration from Edison’s cadmium-copper storage battery patent application, 15 October 1900.

Delicate as this operation was, it did not match the difficulty of dividing the copper oxide. Here was where Jungner (or whomever else Edison accused of preceding him) had failed to create an effective depolarizer. All their efforts had been blocked by “the production of a small amount of copper salt, bluish in color, and which was soluble in the alkaline liquid.” As the salt circulated and dissolved, it rapidly rotted both positive and negative elements, especially zinc. The containing cell had to be oversize to compensate, while its resistance increased in tandem.

“In consequence,” Edison wrote, “reversible batteries using copper oxide as a depolarizer have never remained in commercial use and are now obsolete.” His battery was unique in that he divided the oxide chemically, making it as smooth as the purest talc. “If…there is a single piece, no matter how minute, of dense copper, or even if the finely divided copper is compressed sufficiently to materially increase its density, a soluble hydroxid of copper will be formed.” To avoid any such salt-causing impediments, Edison obtained his powder by reducing copper carbonate with hydrogen at the lowest possible temperature. This made it light, anhydrous, and insoluble, the last property being essential to the efficiency of storage battery electrodes. “When the copper has been thus secured in finely divided form, it is molded into thin blocks of the proper shape to fit snugly in the pockets of the plates….”

By now, two-thirds of the way through his application, Edison was clearly reveling in the intricacy of what he was describing (“Grand science, chemistry. I like it best of all the sciences.”) and in the terminology needed to protect every nuance from infringement.31

After the copper [filled] plates have been molded, they are subjected in a closed chamber to a temperature of not over five hundred degrees Fahrenheit for six or seven hours until the copper is converted into its black oxid (CuO). If higher temperatures are required, the density of the black oxid will be undesirably increased. After being thus oxidized, the copper oxide blocks are reduced electrolytically to metallic copper, and are then reoxidized on charging by the current until they are converted into the red oxid (CU2O). In this form, the blocks are inserted in the perforated pockets 6 of the desired plates, which are then ready for use.

The finely divided copper originally obtained by reduction by hydrogen as explained, may be lightly packed in the perforated receptacles without being first oxidized by heat as described. I find, however, that when this is done, the efficiency is not so high as when the copper is first oxidized to the black oxid, because, unlike the cadmium, it is not filamentary in form, and its particles as originally produced do not apparently effect an intimate electrical contact with each other.

The last stages of fabrication were to brace and insulate the loaded plates in a nickel frame, connect them electrically, and slot the whole assembly—densely engineered, yet as easy to lift as an attaché case—into its nickel sleeve. It was then topped up with a solution of 10 percent sodic hydroxide and hermetically sealed, except for a one-way valve for the release of hydrogen bubbles on recharge. Two neatly protruding pole tips, positive and negative, completed the cell, which could be stacked with others, to stream as much power as desired.

In a final paragraph of description, Edison exulted in the duality of his design. During discharge, the cadmium became cadmous oxide and the cupric oxide became copper. During recharge, the metals and oxides converted back to their original state, and even the water in the electrolyte “respectively decomposed and regenerated, leaving the liquid in exactly the same condition and quantity after each discharge.” There was so little evaporation that the cell hardly needed its refill cap. “In fact I find by practice that by interposing between the plates thin sheets of asbestos…which have been merely moistened with the alkaline liquid, nearly as good results can be secured as when the plates are actually immersed.”32

It was a state-of-the-art battery that paid tribute, in its alternations of metal and damp fiber, to Volta’s electric pile of a hundred years before.

WHEN SEEN AND FOLLOWED

Even as he signed his two new patents, Edison knew that he had done little to challenge the crude power of the lead-acid car battery. There were several things wrong with his cadmium-copper cell, starting with the prohibitive expense of both metals.*7 It was impractical, with an output of only .44 volts, and even if cheaper electrodes could be made to generate more energy per unit weight, the delicacy of its assembly boded ill for commercial production. Nor, despite Edison’s claims, had he entirely solved the problem of blue-salt precipitation. By November he was back in his chemical laboratory, searching again for a perfect yin and yang of reversible galvanic power.33

It was a month otherwise enlivened by a letter from William, who seemed to have forgotten the paternal wrath he had recently incurred. Writing now in the guise of a concerned sibling, he reported that Tom’s showgirl wife*8 had deserted him and was abusing her former connections:

Marie Edison was seen going into the “Haymarket,” one of New York’s worst joints, with two strange men and a bad woman. She was making the rounds of the “Tenderloin” [District] and boasting to everybody that she was Edisons daughter in law and his favorite….She seems to think she is playing all of us for “suckers.” When seen and followed she was drunk and telling everything to these dirty people.34

William begged his father to do something to protect the family’s “good name.” Edison thought it wise to comply, arranging privately to pay Marie twenty-five dollars a week if she would stop identifying herself with him.35

Switching his attention back to the more congenial subject of cement making, he reconsidered the long kiln he had patented earlier in the year. It was intended to be the centerpiece of the great cement-making plant he was building at New Village, near Stewartsville,*9 New Jersey. Although the kiln was ready to ship, he could not resist the temptation to lengthen it during breaks from battery experiments. Walter Mallory found that Edison’s new idea of long was whatever volume of tube would disgorge a thousand barrels of cement a day. When the engineer warned him that output was 400 percent beyond the capacity of any burner in the industry, he came up with specifications for a kiln 150 feet long and nine feet in diameter, made up of fifteen cast-iron sections and rotating on fifteen bearings big enough to hold Nelson’s Column.36

THE PRETTIEST PLACE IN FLORIDA

By the new year of 1901, with two patents pending and more than a hundred laboratory staff assisting him in further development of the alkaline storage battery, Edison was unable to keep his grand project secret from speculators. A Swedish corporation, Ackumulator Actiebolaget Jungner, had already been formed in Stockholm by his only competitor, but its name did not resonate on Wall Street as much as that of the Edison Storage Battery Company, capitalized on 1 February at $1.5 million.37 Within eighteen days the New York trust attorney Louis Bomeisler offered Edison $3 million in cash for the right to market his new battery, even though it was still more of a theory than a product.

Edison hedged. Bomeisler assumed he was looking for other offers and wrote in some irritation, “I do not want to do a lot of work on a matter of this magnitude, and find when ready to close that I am bidding against the field….[Hence] I suggested a figure which would be so high that you could not refuse it.”38

It was in fact high enough to wipe out all Edison’s mining debts and pay for his cement mill as well. But he kept politely putting Bomeisler off (“I do not want to dispute your arguments”) until the lawyer, bewildered, realized he was a person who could not be bought.39

The same could not be said of Thomas A. Edison, Jr., whose eagerness to sell his own name caused a defrauded investor in the Edison-Holzer Steel & Iron Process Company to sue him for $400,000 in mid-February. Warned by a third party that Tom might end up in jail, Edison replied with weary déjà vu. “As I know nothing about this matter, I prefer not to have anything to do with it. As the young man is of age I am not responsible for anything that he does.”40

With that, he decided it was time he took a break from Julius Thomsen’s Thermochemische Untersuchungen, Gladstone and Tribe’s Chemistry of the Secondary Batteries of Planté and Fauré, and back issues of the Journal of the American Chemical Society. “I am going to Florida for a month to polish up my intellect,” he joked to a friend.41 For the first time in fourteen years he felt free to return to the estate in Fort Myers that he and Ezra Gilliland—more than a friend, once, before becoming more than an enemy—had bought together, back in the days when they called each other Damon and Pythias and Miss Mina Miller was Gilliland’s gift to him beyond price.*10 Plump Damon was dying of heart disease now, and he too had long been a stranger to Fort Myers, so there was no chance of them bridling at each other across the twenty yards of garden that separated their twin houses.

In any case it was high time Edison checked up on a property he had allowed to deteriorate under a succession of vacationers and invalids since 1887.42 Mina accompanied him, along with their three children, two relatives, and a maid. The visit was more chastening than nostalgic. Their caretaker had attempted to freshen the house with dabs of paint, but there were hardly enough beds for a party of eight, nor was there a cook to feed them. The Gilliland house now belonged to a multimillionaire—Ambrose McGregor, president of Standard Oil—and looked it, in contrast with its weed-fringed neighbor’s. Nevertheless the surrounding park Edison had laid out with such symmetry in 1885 had lushly matured, and Mina with her gardener’s eye could see much potential for bringing it back into horticultural balance.

For the next five weeks they made do, befriending the McGregors, eating out at the downtown hotel, and importing truckloads of soil for new plantings. Edison polished his intellect with a fishing rod, dragging a thirty-pound channel bass out of the crystal waters of the Caloosahatchee but failed in several seagoing attempts to land a tarpon. He told a reporter that he intended to make Fort Myers his regular winter home. “It is the prettiest place in Florida, and sooner or later visitors to the East Coast will find it out.”43

WHICH?

One of the first things Edison did after returning north was to attend an electrical lecture-demonstration at Columbia University by Nikola Tesla. Although as fellow innovators in the field they had about as much in common as the rival power systems they personified—direct versus alternating current—their relations had always been distantly cordial.*11 Edison could be unforgiving of any former associate who tried to get rich on things he had taught them (as Ezra Gilliland could attest). But Tesla had brought his own genius to the Edison Machine Works in 1884, and taken nothing else with him six months later, when he left to form the Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing Company.

Edison was late arriving at Havermeyer Hall, and the audience erupted with applause at his entry. Tesla was already at work displaying the light effects of his electric oscillator, but at the sound of cheers he looked up and, in the words of a reporter, “saw the greatest of all American inventors….Mr. Tesla stopped his work and grasped Mr. Edison’s hand, which he shook as he led him to a seat,” to further cheers for them both.44

Another interested observer was Guglielmo Marconi. At twenty-seven, the Italian engineer was not much older than the students in the room. He came to West Orange on 16 April to look at Edison’s old patent on “wireless telegraphy” and hear him ramble on for four hours about radiating sound waves that would one day encircle the globe and penetrate space.45 This was hardly a revelation to Marconi, who had already beamed Morse signals across the English Channel. But the patent was of great interest to him and worthy of more businesslike discussion as his own experiments proceeded.

Shortly afterward a headline in Western Electrician speculated what the medium might best be called in the twentieth century—“SPARK, SPACE, WIRELESS, ETHERIC, HERTZIAN WAVE OR CABLELESS TELEGRAPHY—WHICH?”46 Not even Marconi had yet suggested the word radio.

A PACK RATHER THAN A TANK

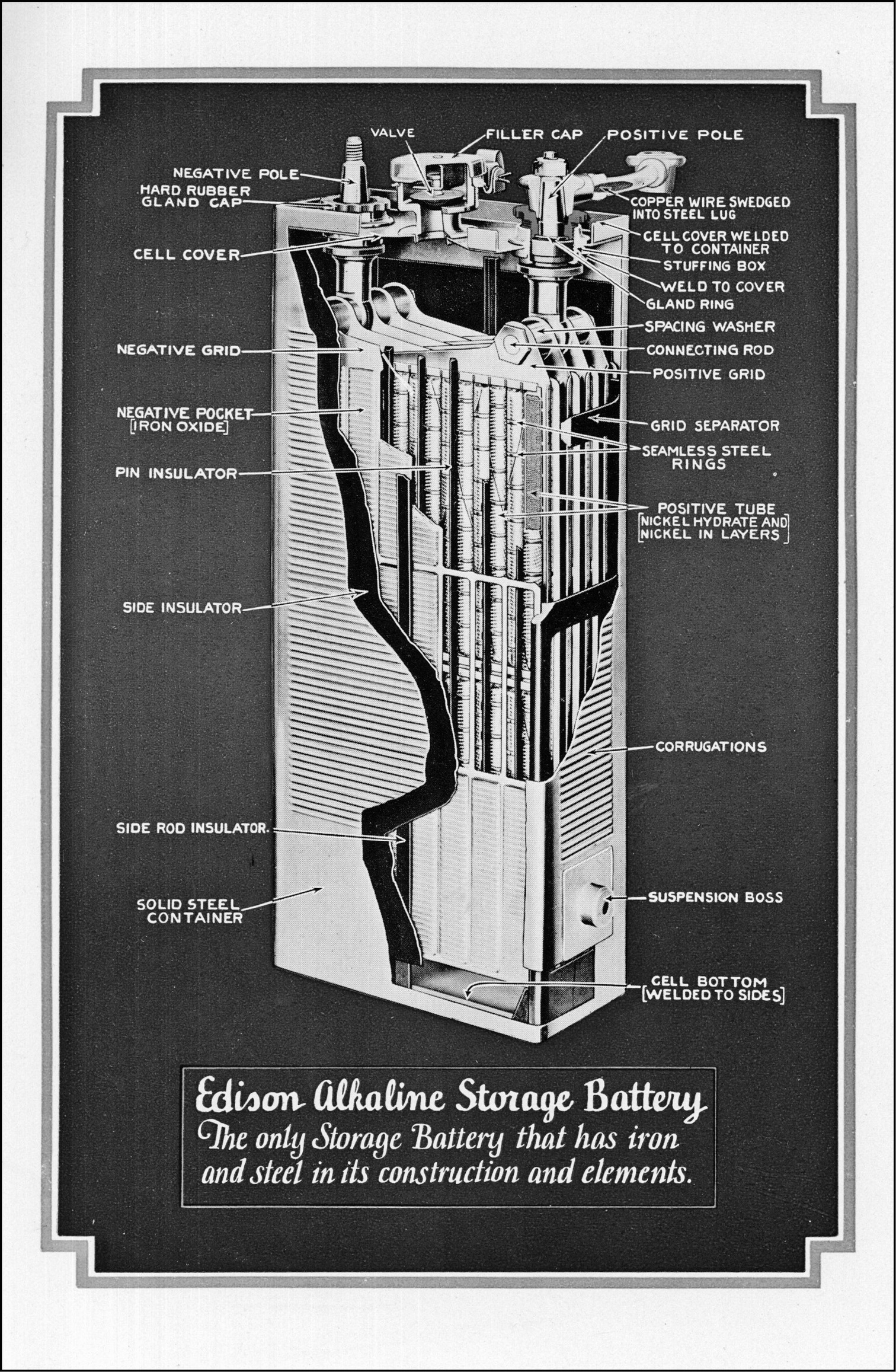

On 21 May, the chief theoretician of Edison Industries, Dr. Arthur Kennelly, rose before the annual meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers to announce that his boss had invented a new type of storage battery. After some nine thousand personal experiments, Edison had discovered a pair of metals whose electrochemical properties corresponded so closely as to permit the practical realization of the reversible galvanic cell.47

The paper Kennelly proceeded to present was technical, but its revelation that Edison had settled on a superoxide of nickel for his positive electrode caused what passed, in professional circles, for a sensation. Nickel was known to be nonconductive in its oxidized and reduced forms, and it was almost as expensive as cadmium if worked at all finely. Iron—his negative element—was a more predictable opposite, promising a large number of deep discharge cycles. Edison increased the conductivity of the positive electrode by mixing tiny flakes of graphite with nickel hydrate and tamping the resultant powders into the same pocketed plates he had used in his previous cell design. The graphite, pure crystallized carbon, took no part in the new battery’s action except to provide microscopic conduits within each compound. They enabled a free flow of oxygen ions from pocket to pocket, in a solution of 25 percent potassium hydroxide—Edison’s preferred alkaline electrolyte in all his battery experiments.48

Kennelly claimed, to the disbelief of some skeptics, that the nickel-iron cell had a storage capacity of fourteen watt-hours per pound, enough raw power to lift a load its own weight to a height of seven miles on a single charge. A lead-acid cell, in contrast, would rise only two to three miles before falling and making a significant dent in the earth’s surface. Edison’s battery was a pack rather than a tank, so solidly amalgamated that it could withstand all the shocks that automobiles were heir to, and (like its creator) superbly balanced. He admitted at the end of his presentation that the pockets had nevertheless caused Edison some trouble. Their expansion and contraction as they respectively lost oxygen, or recovered it, caused the “nickel” plates to swell slightly while the “iron” ones shrank, and vice versa during the next phase of the charge-recharge cycle. In either case, these internal pressure variations caused the cell’s thin steel walls to—as it were—breathe in and out but, he insisted, “well within the elastic limits” of the metal.

Finally Kennelly half-answered the one question every Exide man in the audience wanted to ask: “As regards cost, Mr. Edison believes that after factory facilities now in the course of preparation have been completed, he will be able to furnish the cells at a price per kilowatt not greater than lead cells.”

A NEW EPOCH IN THE CEMENT BUSINESS

A distance of sixty miles and seventeen stops on the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad separated Edison’s two factory projects that spring. He became a commuter between them, supervising every detail of construction and pondering their likely output. One Saturday at 10:40 A.M. he arrived at New Village and took a tour of the cement mill from the quarry to the packing house. Seven of its eleven steel-and-concrete buildings were complete or nearly so, and the rest looked to be ready and fully equipped by midsummer.49 Although what he saw was already the fifth-biggest cement plant in the country, he decided to increase its capacity from four hundred to a thousand barrels a day. He spent the afternoon brooding on-site, then took the five-thirty train home. Working from memory through the night and on into Sunday afternoon, he made a list of nearly six hundred necessary changes to the mill’s design, including dimensions for new machinery and an order for two Carnegie steam shovels to open up more of the underlying cement rock vein.*12, 50

Only after the list had been copied and sent to the superintendent did he inform Harlan Page, a director of the Edison Portland Cement Company, that the firm would have to sell “say $400,000” of its preferred stock to pay for the modifications he required. “I am sure this Mill will establish a new epoch in the Cement business.”*13, 51

Walter Mallory, part of whose job was to keep men like Page happy, knew from ten years’ experience in the mountains that Edison designed more by instinct than by reason. “I cannot help coming to the conclusion,” he remarked later, when the long kiln was turning and the plant was producing over eleven hundred barrels of cement a day, “that he has a faculty not possessed by the average mortal, of intuitively and correctly sizing up mechanical and commercial possibilities.”52

WHAT HAPPENED ON TWENTY-THIRD STREET

The first suggestion in the American press that Edison was not alone in developing an alkaline car battery appeared in The Marion (Ohio) Democrat on 8 June 1901. “Mr. Jungner of Stockholm, a Swedish engineer, has invented a new accumulator,*14 which, in spite of its extraordinary light weight, is said to have a great capacity….A vehicle equipped with this [device] made on a trial trip 95 miles, without it having been necessary to recharge….The scheme seems to be similar to E’s last invention.”

The interest of Buckeye newspaper readers in Swedish auto traction was slight, but Edison evidently knew all about the accumulator by the beginning of July, when W. N. Stewart, an entrepreneur in London, offered him a chance to combine Jungner’s European patents with his own. “The experiments of Prof. Jungner (who seems to be a most able chemist) cover a term of seven years, and are of great value….I may say, also, that Prof. Jungner has a very high opinion of your work in this field, and that he makes no conditions of an embarrassing nature.”53

Edison reacted dismissively, as he always did to direct competition. “I was surprised to learn that you had bought Jungner’s patents. You will find that they have no value, because they are based on theory. An actual experiment will prove his patents bad in every particular.”54

Instead, he sold his own past patents, plus any new ones he might win over the next five years, to the Edison Storage Battery Company for $1 million. He took only $100,000 in cash and trusted he would earn the rest in stock earnings. If he had known that he would be awarded sixty-two more electrochemical letters patent in that period, he might have valued his expertise more highly.55

That was not the case with a movie patent he had been trying to profit from for years, which at this moment emerged from litigation and promised him fabulous royalties. On 15 July the U.S. Circuit Court in the Southern District of New York ruled in Edison v. American Mutoscope and Biograph Company that he was the original inventor of the Kinetograph movie camera and could therefore block others from capitalizing on any of its features without a license. The decision was subject to appeal but temporarily made Edison the most powerful film executive in the United States.56

Never having been interested in the creative side of moviemaking, he was content to leave his house director, the gifted Edwin S. Porter, in charge of production while he spent six weeks in Canada, seeking a source of nickel for his new battery. The metal was only slightly less expensive than cadmium or cobalt. He needed a private supply of it at cost if the chemical plant Arthur Kennelly had mentioned (rapidly rising at Silver Lake) was to be profitable. Assuming the battery survived a punishing series of vibration tests he had ordered, he planned to start producing it about a year and a half from now.

By early August he was cruising north through Lake St. Clair, the transitory body of water, half American and half Canadian, that divided Lakes Erie and Huron.57 He had sailed these same waters as a child, on another voyage between opposites—from his birthplace in Milan, Ohio, to the big white house at Fort Gratiot, Michigan, where he had begun to be a man. There was no time now for him to disembark in Port Huron and revisit any boyhood haunts, because the ship was heading for the nickel-rich town of Sudbury, Ontario.58

He was swatting blackflies and prospecting with a magnetized needle for a seam to claim, on the day Porter set up a camera in New York and filmed a new Edison short, What Happened on Twenty-third Street. It caught the moment when a young woman, strolling the sidewalk in midsummer heat, stepped over a ventilating grille and felt her skirt billowing upward, to the voyeuristic pleasure of passersby.59

OMNIPOTENT POSSESSION

Edison returned home with a successful mine claim in his pocket—he had discovered dense deposits of nickel ore in the East Falconbridge area of Sudbury*15—to find that he was once again a man with family problems. There had been a foiled kidnap threat against his younger children, and Madeleine’s governess was so distraught over it she had committed suicide. Tom had managed to keep out of jail, but was bouncing checks and advertising something called the Wizard Ink Tablet (“We have testimonials from 1,000 banks”) over the logotype of the Thomas A. Edison Jr. Chemical Company. William was quiet for the moment, but his lulls usually preceded storms.60

Business at least was good, despite the shock of President William McKinley’s assassination on 6 September at the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo.*16 Newsreel coverage of his dying days and the assumption of power by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt had unfortunately rendered trivial some exquisite footage shot by Porter of the exhibition grounds illuminated at night—one slow pan resembling a spill of diamonds across black velvet.61 Otherwise, Edison’s film studio was doing well. So was National Phonograph, his recording firm, outselling every competitor despite the formation of an aggressive, disk-cutting newcomer, the Victor Talking Machine Company. The cement mill was complete, the chemical plant almost so, and the storage battery was getting some rhapsodic press comment. An illustrated article on its “wonders” in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle showed a seated man holding up the slim metal box with one arm. “This latest achievement of Edison is probably destined to work as great changes in its way as did the electric light,” the text commented. “The fact must be easily apparent to everybody that the ability to carry around in the palm of one’s hand the power that can, so to speak, move mountains, would be almost an omnipotent possession.”62

On 16 November Edison received a long letter from the inventor of the Phantoscope movie projector, which had become his own Vitascope in 1896 by right of patent purchase.*17 Thomas Armat begged him to consider, in the light of his recent court victory over the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, withdrawing from the case now under appeal. “Hopeful as you may feel over the result of that suit, you probably realize, as I do, that the decision, while probable, is anything but a sure thing.” The case’s cumulative effect so far had been to deny all parties to it the profits they would have earned, while “hundreds of ignorant or illiterate infringers of patents” had gotten rich at much less cost.63

Rather than continue to litigate, Armat wrote, the major players should agree to the formation of a consolidated motion picture company, or “trust,” that would pool all their patents. “This combined action would establish a real monopoly, as no infringer would stand against a combination of all these strong elements.” Edison’s reward for cross-licensing his unmatched number of letters patent would be royalty and manufacturing privileges more than equal to their aggregate value.64

“Can I expect a prompt reply?” Armat asked, obviously aware that Edison was leery of any moves on his intellectual property.65

Edison referred the proposal to his studio head, William Gilmore. “Say that I cannot very well go into the matter by letter…also that I do not agree with many of his suggestions in regard to litigation.” He was, however, interested enough in the trust idea to invite Armat to send an intermediary to discuss it with him. Eventually he said no, proposing instead a cross-licensing agreement to be negotiated after the appeals court ruled. Armat saw that Edison was gambling on a further victory that would make him so powerful as to be a monopoly unto himself.66

There was nothing for a weaker player to do but gamble on that gamble and await the court’s decision. At least the idea of a national motion picture trust had been discussed for the first time, and it might be discussed again if Edison’s dice throw turned up less than a six.

MONUMENTAL AUDACITY

Instead of flowers, centerpieces of tiny green lightbulbs ornamented the tables at a special dinner of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in New York on 13 January 1902.67 Larger, whiter bulbs at either end of the Astor Gallery spelled out the mysterious words POLDHU and ST. JOHNS, and yet more lamps, arranged in clumps of three, sporadically flashed the Morse signal “– – –.” It signified the letter S, which the guest of honor, Guglielmo Marconi, had beamed across the Atlantic, from Cornwall to Canada, one month before.

The general glow bathed the faces of many other electrical titans: Alexander Graham Bell, Elihu Thomson, Frank J. Sprague, Carl Hering, William Stanley, and the institute’s president, Charles Steinmetz. It also illumined Mina Edison, sitting alone at the high table.

“I believe I voice the sentiments of all,” Steinmetz said in his opening remarks, “when I say that we are extremely sorry not to have with us the grand master of our industry, Mr. Edison.” Instead, he welcomed Marconi as “another genius…who, taking up where Mr. Edison left off at the beginning of his career, has advanced beyond what others have done.”

If that sounded like a reference to the wireless work of another notable absentee, Nikola Tesla, Steinmetz did not elaborate.*18 He turned the proceedings over to the toastmaster, Thomas Commerford Martin, who lost no time in reading a handwritten note from Edison: “I am sorry that I am prevented from attending your annual dinner tonight, especially as I should like to pay my respects to Marconi, the young man who had the monumental audacity to attempt, and succeed in, jumping an electrical wave clear across the Atlantic Ocean.”

A COLD HEART LIKE MY FATHERS

That night Edison was lying ill in a New York hospital, suffering from an unusually harsh attack of the stomach pain that often troubled him. For the last four days he had subsisted on nothing but water. Mina’s willingness to quit his bedside for the dinner indicated that he had begun to recover, but it would be three days more before he was allowed to drink some milk and eat a chop.68

William Edison could have chosen a better time to write to his stepmother complaining about his life as the “forlorn son of a great man.” But tact had never been Will’s principal virtue. Nor was he subtle in appealing for sympathy from the one person who could rehabilitate him in the family circle:

It is now over two years since I have gotten a line from you or home and it rather sticks in a fellows craw to be treated in this manner. Of course I believe in my heart that you would not treat me so coldly if it were not for my fathers wishes in the matter as I believe you have a good and not a cold heart like my fathers….I don’t blame you in the least as you have your own children and they occupy all your time and devotion. We have sort of drifted away like a dead log down a slow flowing stream and its no easy matter to push that log back from its starting place and duced hard it is for a fellow to stand out in the starlight to find in what direction his home is when he has not a home that he can call his own. Often, I have half started for Orange but somehow the thought that came over me prevented such a step not knowing if any one would welcome my outstretched hand or not.69

Mina’s experience was that whenever William stretched his hand out, it was for money. But this time all he requested was a photograph of the children: “To think I would pass them in the street and not know them.”70

She took Edison to recuperate in Fort Myers where, still frail in mid-March, he heard that Tom and William had been arrested in a fracas with police in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. Tom was charged with being intoxicated on a public street, and his brother for having struck the police officer detaining him. They had spent the night in jail, Tom being released on payment of a fine of $7.50, and William on finding—somewhere—$100 for a bond that committed him to appear in court later, on a charge of assault and battery.71

The same issue of The Evening World reporting this incident carried a news item equally if not more distressing to the young men’s “cold-hearted” father:

EDISON NOT INVENTOR OF MOVING PICTURES

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals handed down a decision this afternoon declaring that Thomas A. Edison was not the inventor of “moving pictures” and that the various other machines besides his are no infringements on his patents. By this decision the Edison Company will have lost thousands of dollars in royalties.72

Edison’s angry reaction was to reissue his basic camera patents, in narrowed form and once again sue every major studio in sight, including Mélies and Pathé in France. It was not a happy month for him, even though National Phonograph reported soaring sales of his new line of “gold molded” wax records, now being duplicated at the rate of ten thousand cylinders a day. He still needed to rest daily at noon after returning to West Orange in April.73

Better than bottles of medicine for his body and spirit as summer came on were some highly successful road tests of the storage battery. The first—sixty-two miles straight in a small Woods runabout—earned him a box of cigars from ESBC stockholders. He participated in some of them and became as addicted as Mr. Toad to the thrill of jouncing along country highways at dangerous speeds. “The sport of kings I call it—this automobiling at 70 miles an hour. Nothing on earth compares with it.” Edison could not have attained that speed in an “electric”—more likely during a comparative run in a gasoline car—but mobility was the thing, and he would remain a road hog for the rest of his life. Oddly, for a man who needed to be in control, the act of driving itself did not suit him. After one or two tries that ended up in ditches, he settled for a seat up front next to the chauffeur, where he could see everything and let passengers behind enjoy his secondary cigar smoke.74

Mina was a nervous convert to his new hobby. “This afternoon we had a spin over to South Orange and back in one of the gasoline flying automobiles,” she wrote her mother. “It was great sport but it made me feel like clinging to the sides every moment and felt myself drawn up to the highest tension for fear something might happen.” When Edison bought two big White “steamers” for excursions upcountry, the family named them Discord and Disaster.75

THERE WILL BE A FIRE

Bulk orders were already coming in for the battery by midsummer. They were premature, because Edison was a fanatical tester. Until five of his prototype units had each withstood five thousand miles of rough riding in electric vehicles as large as a three-ton truck, he declined to go into production. Besides, he was still experimenting with combinations other than nickel-iron and showing a serious interest in cobalt.76

This did not stop him announcing in the July issue of The North American Review that he had achieved the “final perfection” of the alkaline storage battery. He wrote that the lead-acid cell could not be compared with it, being self-destructive as well as heavy. “A storage battery, to deserve the name, should be a perfectly reversible instrument, receiving and giving out power like a dynamo motor, without any deterioration of the mechanism of conversion.” The alkaline cells he was currently testing weighed less than sixteen pounds apiece and showed “no signs of chemical deterioration, even in a battery which has been charged and discharged over 700 times.”77

He allowed that an electromobile driven by his battery would be costly to buy, at $700 and up, but argued that its horsepower, unlike real horsepower, was cheap. A fifty-cent charge was all an Edison cell needed to propel a Baker two-seater eighty-five miles along a level road, and it did not have to be topped up with oats every day when it was not being used. Again in contrast to the horse, it could be relied on to work without regrettable sound effects. “The electric carriage will be practically silent and easily stopped in an emergency.”78

Edwin S. Porter might have been expected at this juncture to come up with an automobile-featuring scenario, since he was under pressure to do something to rescue his boss’s floundering movie business. But when he did come up with the idea of a film that told a dramatic story, instead of presenting a staged “turn”—like a boxing bout or a dance solo—he directed it around the more cinematic spectacle of a team of horses at full gallop. His Life of an American Fireman, which began shooting that fall, was so elaborate a production that the Newark Evening News felt obliged to warn its readers on 15 November, “There will be a fire on Rhode Island Avenue, East Orange, this afternoon.”79

Porter liked to boast afterward that Fireman was “the first story film.” That was not true, but it was nonetheless unprecedented in its use of temporal overlaps.80 It anticipated Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase in breaking action up into a series of visual shards, each one angled differently yet integrated with those that came before or after. The paradoxical effect was of narrative speed and busyness of content, although the movie was (like the Edison kiln) more than twice as long as normal.

A drowsy fireman on watch duty sat half-dreaming of home (his wife, in a floating vignette, putting his daughter to bed) when an unheard alarm sounded. The fireman’s sleeping colleagues awoke, jumped into their oilskins, and slid out of frame down a pole. In the stable below, the pole remained bare while horses, raring to go, were harnessed to their engines. The sliding firemen came on scene just in time to jump onto the departing equipages. Outside, it was—surprisingly—daytime, and the façade of the firehouse was quiet. Then team after team burst through the stable doors and galloped away. A crowd on a residential street corner watched as no fewer than ten engines sped toward and past the camera. On the outskirts of town, sparser onlookers saw the same procession approaching and slowing. A leftward pan tracked the hose wagon as it stopped in front of a burning house. Inside the bedroom upstairs, a little girl and her mother (also keeping irregular hours) were sleeping together while ominous puffs came through door and floor. Waking and choking, the woman rushed to the sash window and waved for help before falling in a faint. A fireman entered and axed the window open. The prongs of a ladder bumped against the sill as he hoisted the woman onto his shoulder, climbed out, and dropped from view. Moments later he climbed back in again and found Snookums still asleep in the smoke. As she too was carried to safety, two hose bearers came through the door and sprayed the bedroom with such force that its principal decoration, a framed plaque reading “THOMAS A. EDISON—TRADE MARK,” nearly fell off its hook.

Down in the garden, the rescuing fireman was about to chop his way into the house. The woman appeared above him, waving through a sash window in a reverse of the image seen one and a half minutes earlier. The prongs of the ladder that saved her—and would save her once more—tilted upward as she fell back fainting. By now the ax-wielding fireman had gotten upstairs. No sooner had he broken open the window and brought her down, laying her tenderly on the wet grass, than she came to and with further frantic arm-waving told him that he had not completed his work. Hurrying back up the ladder, he returned to ground level with Snookums, and the feature came to an end with two nightgowned female figures embracing.

It would be thirteen years before a bit player on Edison’s payroll, D. W. Griffith, rose to obliterate the memory of Edwin S. Porter as a film director.*19 In the meantime the older man pioneered a style that in future movie parlance might be described as “déjà vu all over again.”

TOPSY

Considerably less entertaining, if horridly more watchable, was Porter’s next feature, Electrocuting an Elephant. Filmed at Coney Island on 4 January 1903, it documented the last minutes of Topsy, a circus pachyderm of uncertain temper who had to be put away for killing three men in three months. The last had been a drunken trainer who thought it would be amusing to feed her a lighted cigarette butt. Nodding and swaying, she followed her handlers onto a pad electrified with six thousand volts of direct current and allowed them to strap her into place. For a few seconds she stood still, then white fumes billowed around her feet, and she toppled like a punctured airship. The camera held her in close-up as she lay on her side, until her left hind leg, stiffly extended, relaxed and sank.*20, 81

THE NAME OF THOMAS A. EDISON

The desire of William Edison to protect his father’s “good name,” even while besmirching it himself, became a matter of commercial urgency that winter. Whether framed on the wall of a movie set or stamped on countless thousands of phonographs, dynamos, and other devices, the trademark was an asset beyond price. Edison had cause to regret, just when he was preparing to sign off on the mass production of storage batteries and portland cement, that he had given the same name to his eldest son.

Edison’s trademark signature, 1902.

Joseph F. McCoy, who served him as an industrial and personal spy, reported that Tom had sold it to Charles F. Stilwell, throwing in the “Jr.” for free. “Mr. Stilwell wants to put a Thomas A. Edison, Jr. Phonograph Company on the Market, he says there would be big money in it.”82

Stilwell was Tom’s maternal uncle, a former glassblower with plenty of hot air still left to spare. Edison regarded him with wary benevolence. He had made use of his family connection before, helping Tom organize the Thomas A. Edison, Jr. Improved Incandescent Lamp Company. McCoy wrote in his memorandum that their new venture trespassed even more rudely on Edison’s personal territory. “He said that he refused last week $5,000 Five Thousand dollars he thinks he can get more.”83

Apparently Stilwell had already tried to resell the Edison name to the Columbia Phonograph Company, a major competitor of National Phonograph, but failed because his intermediary (Tom?) “was drunk for more than (3) three weeks, and the Columbia people would not deal with them.” If anything more was needed to seal Tom’s paterfamilial fate, it was Stilwell’s remark to McCoy “that Mr. Edison would only live a few years longer, at his death, he would bring suit against the National Phonograph Co. for using the name of Thomas A. Edison on their Phonograph and Record and supplies. He would make big money from that, as the Company would have to pay him, if they continued to use the name Thomas A. Edison.”84

Edison père had to struggle between anger at Tom and compassion for Stilwell, who had recently gone blind and had a large family to support. Notwithstanding the pair’s earlier collaboration in the lighting industry, they were neither of them bulbs of especial brightness—as evinced by Stilwell’s naïve assumption that McCoy would not at once alert Edison to their intent.

It was clear to Edison that Tom deserved a legal slap in the face that would stop him from ever again participating in identity theft. At the same time, having consistently refused to give him and William jobs at the plant, he had to accept some responsibility for Tom’s abject condition. The young man was impoverished, depressed over the failure of his marriage, rooming in Newark with the Stilwells, and drinking heavily. He had taken to bed in one of his prolonged sieges of paroxysmal head pain.85

But even now Edison felt unable to lay a symbolic hand on his son’s forehead: “Tom is either crazy or a very bad character.” He allowed Randolph to send him a terse note saying that they must come to an immediate legal arrangement, with some guarantee of security on both sides.86

In return he received a three-page, meticulously scripted outpouring of bile, shocking to read from somebody as timid as Tom. It began “Dear Sir,” and continued:

Since I left you some six years ago—my career has undoubtedly been a wild one—as everyone knows—but I am not at all sorry that I have had the experience—although I am sorry I have injured you in the manner I have—however this is done now and I will talk to you as man to man realizing that our hatred towards each other is very intense.

I can honestly say that I never have had the slightest intention of doing you any injury—but your persistent refusal to take me back with you—I will admit has often caused me to give you little consideration in matters where I was personally benefitted. I know of no business deal that I have ever made—that I was not taken advantage of—having often been forced to enter into agreements to save myself from absolute poverty….

I never dared to ask your advice nor to consult you upon any matter whatsoever—for from the very first you gave me sufficient cause to consider you as my worst enemy and I still consider you today as such.87

The shapely undulations of Tom’s pen seemed to calm him down a little. He acknowledged that Edison had never done him any serious injury, “and you couldn’t if you wanted to—for I have injured myself too much to have anyone else do it.” He had rushed into his deal with Stilwell out of desperation, never having made one with his own father. There were, he confessed, some other name-selling contracts that Edison might find objectionable.*21 “My object in writing to you is to ascertain whether you are interested at all in their recovery—they are of course the only means by which I derive a living at present.”88

Always, in letters of this kind, the begging note intruded. Having sounded it, Tom cast all dignity aside and verbally threw himself on his father’s mercy. “I will sign any reasonable agreement with you—in which you can dictate your own terms—which will satisfy forever—an agreement which will deprive me of all future rights to the name of Edison.”89

It was an abject surrender in a life marked by many. Edison had his legal department draw up twin contracts guaranteeing Tom and Stilwell respectively $1,890 and $1,350 per annum, in exchange for vows not to leech him again. Just to make sure they understood, he went to court anyway to prevent the Thomas A. Edison Jr. Chemical Company from selling any more Edison Magneto-Electric Vitalizers.90

SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTION

By mid-February, cement and car battery production had started at Edison’s two huge new plants in New Jersey. Progress in each case was experimental and slow, but he predicted it would soon accelerate to a point where marketing could begin. He was uncowed by a threat to his pending copper-cadmium cell patent, filed by Ackumulator Actiebolaget Jungner, and announced by that company in English, presumably to get American attention: “The patent office of the United States has not agreed to Edisons claims, but has already made him several disagreeable questions. Some particulars in the case between him and Jungner will an interference jury decide.”91

It was true that the Patent Office had agreed to hear Jungner’s counterclaim to have preceded him in 1899 with a silver-cadmium cell patented in Britain, but Edison was sure that the examiner would find that early device inoperable. In any case, he was no longer interested in cadmium and had applied much more successfully for a patent on his nickel-iron combination.92

“At last I’ve finished work on my storage battery,” he told a reporter who came upon him hunched over a yellow pad in his laboratory. “And now I’m going to take a rest.” He threw a stub pencil down and dropped into an armchair. “I’m tired—very tired. I’m all worn out.”

There was a twinkle in his eye as he said this, but he insisted that what he needed was an extremely long vacation, starting at once in Florida. He had a four-hundred-page notebook of ideas that he had never had time to develop. “I’ve made up my mind to drop industrial science for two whole years and rest myself by taking up pure science.”93

Exhausted Edison undoubtedly was, and he did not mention the notebook again after he got to Fort Myers and started fishing. He took only a desultory interest in the sport, but it suited his deafness and love of being left alone. Little boats named Madeleine and Charles and Theodore bobbed alongside the dock that now extended far out into the Caloosahatchee, and a ninety-two-foot, double-deck steamer named the Thomas A. Edison was in service for excursions upriver. Mina had her own eponymous fishing boat, a twenty-five-foot naphtha launch. But she identified more with the house, extensively refurbished during the last two off-seasons, “and all so fresh and pretty.” She decided that it should henceforth be known as Seminole Lodge.94

Edison enjoyed just a week of “rest” before news of a catastrophe at New Village reached him. There had been an explosion in the mill’s coal blower that touched off a fire in the adjacent oil tanks. At least six men were dead, and scores injured, some burned so badly that their faces were crisped like bacon. Subsequent reports raised the death toll to ten, and ascribed the explosion to the spontaneous combustion of seventy tons of pulverized coal. Much of the plant was reported destroyed, with damage—excluding lawsuits—estimated at several hundred thousand dollars.*22, 95

Edison at Seminole Lodge, early 1900s.

It was the worst industrial disaster in Edison’s career. He set to work on plans to increase safety at the plant, with no apparent thought of returning north to comfort widows and sufferers. As one of his aides remarked with mock envy, “Mr. Edison is fortunate among other men in having been born without feeling.”96

Tom had a sense of that in June, when he signed a formal agreement to stop using his father’s name commercially. He was welcome to do what he liked with “Jr.” In exchange he was granted a weekly allowance of thirty-five dollars, every payment requiring a receipt. With typical naïveté he assumed he had been forgiven his peccadillos and the following month asked for a job at the laboratory. Edison was quick to disillusion him. “You must know that with your record of passing bad checks and use of liquor…that it would be impossible to connect you with any of the business projects of mine,” he wrote. “It is strange that with your weekly income you can’t go into some small business….William seems to be doing well.”97

He did not mention that he had just approved a request from William to “borrough two thousand dollars” to buy an automobile garage in Washington, D.C. Edison’s aloofness from his elder sons did not preclude him from treating them fairly when they attempted to succeed on their own. William was a good mechanic, and the time was propitious for him to get into the car business. He received his first installment of the loan on 17 July, the day after Henry Ford incorporated a new motor company in Detroit.98

“Now my dear father this is my last call on you,” William wrote, with every appearance of sincerity. “I can promise that the William of several years ago is not the William of today.”99

IT TAKES TIME TO DEVELOP AN INVENTION

When a representative of Electrical Review visited the laboratory that month, Edison hinted that he might become an auto engineer himself. He had just returned from a test of a twenty-four-horsepower gasoline tonneau and found it fast but unstable. “Look here, this is automobile data,” he said, pulling out a red-leather-covered pocketbook stuffed with notes and graphs. “I am going to build a good machine.” His would be all electric, geared for sandy traction, and “able to beat, or at any rate, keep up with, any gasoline machine on a long run.”100

This led the reporter to ask the main question that had brought him to West Orange: why, after many announcements, was the alkaline storage battery still not on the market?

Edison became defensive. “We are making one set a day, and within a short time will be making two sets. We are not doing any advertising, because we have more orders than we can begin to fill….The public doesn’t seem to understand that it takes time to develop an invention.” He said he had spent six years commercializing the electric lightbulb, eight on the telephone transmitter, and sixteen for the phonograph.101

The truth was that his battery, for all its theoretical simplicity, was more complex—and consequently harder to produce—than those previous devices. A tenacious problem was to prevent the iron electrode from being overwhelmed by the rising capacity of its nickel opposite, in order to ensure a smooth and constant voltage curve during the discharge cycle. As his chief chemist, Walter Aylsworth, put it, both elements had to be kept “in training.” Compression of the graphite flakes in each at four tons a square inch was essential but almost impossible to maintain at a constant level, due to flexion of the cell walls. This affected the conductivity of the flakes and the performance of the unit.102 Edison ordered the finest, strongest steel possible from Sweden, but he worried about its expense and fumed over shipping delays.

Another threat to the battery’s economic prospects was the question of its originality. The Patent Office had dismissed Jungner’s interference suit as expected, but did so by citing an obscure French alkaline-cell patent (Darrieus 233,083) that antedated Edison’s by even more years. Now he heard that on 1 September Jungner had been granted a U.S. patent for some “new” storage battery refinements directly based on his own. Or so it seemed to Edison, who turned to the patent attorney Frank L. Dyer for help.103

He had hired Dyer full time a few months before to handle his accumulation of letters patent, which now numbered well over eight hundred and cost the company $100,000 a year in protective litigation.104 Dyer also had a sophisticated understanding of movie rights. That qualified him to make the most of a surprise U.S. Court of Appeals decision granting the Edison studio full ownership of every film it had ever filed as a paper print at the Library of Congress.105 Although technical, the ruling was of major consequence in the industry, and he was working to ensure that it restored the Edison studio’s fortunes.*23

Before the year was out, Dyer would serve as his boss’s personal lawyer too. Tall, bespectacled, bookish, and precise, he was the perfect foil for an inventor impatient of restraint and bored by due process.106 He was cool-tempered and adept at dealing with the strong feelings that arise when human relationships are codified. He venerated Edison without particularly liking him and felt sorry for Tom and William, seeing them as chips never to be reintegrated with the old block.

SHOT FOR SHOT

While Dyer prepared an aggressive case for the canceling of Jungner’s new patent, Edwin S. Porter resumed production of Edison movies, among them a comic feature whose title sounded more innocent in the fall of 1903 than it would in a later age: The Gay Shoe Clerk.*24, 107 His major feature of the year was The Great Train Robbery. Effectively transporting theater viewers from their seats onto a train hijacked by murderous bandits, it was a pioneer “action film” and became the first blockbuster in American history. The scenes shot aboard an open-sided baggage car (hurtling along the same Lackawanna line Edison took on his trips to the cement mill) had the impact of authentic movement, as did an even more thrilling sequence photographed from above and behind the cinder-spraying locomotive. But nothing made audiences scream louder than the final brutal close-up, wherein the chief bandit cocked his revolver and expressionlessly fired straight out of the screen, turning shot into shot.

In perhaps unconscious acknowledgment that the age of the fixed camera had come to an end, Edison ordered the demolition of “Black Maria,” the dark old box that had served as his movie studio ten years before.108

“THIS LATEST DISGRACE”

The year ended badly for Tom and William, the former checking into a sanitarium for vague medical reasons, and the latter incurring paternal fury after calling his garage in Washington the Edison Motor Company. “You are now doing me a vast injury,” Edison wrote him. “You are being used for your name like Tom and as you seem to be a hopeless case I now notify you that hereafter you can go your own way & take care of yourself….I am through.”109

William, terrified that his loan was in jeopardy, apologized and hired a lawyer “to annul the company that I so foolishly allowed to come into existence.” The business reconstituted itself as the Columbia Auto Company. Blanche wrote to say that she was now running it, with four mechanics working around the clock under “Billy’s close attention.” She clearly thought her husband was a commercial moron. All that was needed to make it a success was an extra infusion of capital. “We would like two hundred dollars to carry us through.”110

Edison turned her down.

“You do not seem to think that I appreciate what you have done for me,” William wrote him, “but on the contrary I do….I would call your attention to the fact that I never had the business training that most fathers make their sons go through and it was not my fault as I repeatedly begged for a position at your works but in every instance was refused.”111

The next post brought a note from Charles Stilwell to Randolph confirming that Tom was seriously ill and would undergo treatment, presumably for alcoholism, at St. James Hospital, Newark. He hoped that Randolph would keep “this latest disgrace to the name of Edison” from Tom’s father.112

A PICNIC LIKE THIS