The Minor Arcana

Where the Major Arcana shows us a map of spiritual evolution—what I call “the Fool’s pro-gress”—the Minor shows us cycles. Four suits, each with the same structure yet colored by the special quality of the suit. Ten numbers and four court cards. Consider card games. In most games, it doesn’t really matter which suit it is—a Four of Clubs is basically the same as a Four of Spades. In Tarot, however, the Four of Wands is quite different from the Four of Swords. They share what we call “fourness,” but the suit energy changes them. And the Major and Minor differ in another way. The twenty-two trump cards show us large themes—nature, liberty, light and darkness—and the fifty-six Minor cards give us scenes and characters from our lives.

The Minor cards actually consist of two different sets, the “pips,” or numbered cards, ace–ten, and the court cards, page, knight, queen, and king. Most books look at them as a whole, separated by suits—for example, Ace through King of Wands. Lately I find it valuable to look at them separately, for the numbers indicate events and situations, while the courts evoke people—either actual persons, such as the famous “tall dark stranger” of fortunetellers, or character traits.

The qualities of each suit belong to both groups. Just as the Four of Wands combines fourness with Wands, so the Queen of Wands shows us the qualities of the queen in the confident world of fiery Wands.

The Suits

Before we look at either the numbers or the courts, let’s look at what they have in common: the suits. We can look at a whole range of meanings and backgrounds for these four, from history to Kabbalah to modern psychological descriptions. From all of them, we can get a sense of how each suit’s specialness weaves in and out of all the others.

First, of course, is the number: four of them. In the section on the Emperor, we looked at this number and its great significance in nature and tradition. Without repeating all the many examples, we can remember the most important point: that it is not an arbitrary choice. We find four in the most basic structures of our lives, from the four points needed to form the most simple solid structure, to our four limbs, to the four directions of before, behind, right, and left, to the four earthly directions caused by Earth rotating on an axis (North and South Poles, sun rising in the east, setting in the west), to the four seasons marked by the solstices and equinoxes. None of these are human inventions.

Let’s look at a bit of history. Card historians believe the suits came directly from the Mamluk playing cards originally brought from North Africa (unlike the Major Arcana, which appear to have been invented in Europe). If you look at early decks, the Swords and Batons (an old name for Wands) look very different than what we see in most contemporary decks.

The Swords are scimitars, double-handled, it seems, while the Wands are, in fact, polo sticks. Polo was an aristocratic game, and its stick appears on a number of Mamluk family crests. The Europeans copied the designs on the early cards with apparently not much concern for what they actually were. The French called the polo sticks Batons, and the English called them Staves. Much later, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn gave them the more magical name of Wands, for the Golden Dawn described the four suit objects as magical “weapons.” And over time the complicated game sticks became more like a peasant’s club, while the elegant scimitar became the European broadsword. (This is actually an oversimplification, for indeed some early European decks show straight Swords and elegant straight sticks for Wands.)

The Cups have always been just that: cups. Pentacles, on the other hand, have gone through a complex transformation. Originally the suit showed disks identified as Coins. Éliphas Lévi suggested changing the name to “Pantacles,” by which (according to Paul Huson) he likely meant a magical talisman. Macgregor Mathers changed this to Pentacle, a five-pointed star (called a pentagram) in a circle. This became the name of the suit for the Golden Dawn (though in fact the cards show a cross, not a star, in a disk) and then the Rider deck, and through the Rider to many modern versions. Aleister Crowley called them Disks, while some modern decks, especially in Europe, continue to call them Coins. Hermann Haindl, in his Haindl Tarot, named the suit Stones, an example I followed in my Shining Tribe Tarot. In the Shining Tribe, I actually changed all the emblems from human-made objects to aspects of nature—Trees for Wands, Rivers for Cups, Birds for Swords, and Stones for Pentacles.

One view of the suits describes them as representative of the medieval classes. Wands signify the peasant class, Cups the priesthood (for the chalices used in communion), Swords the aristocracy, and Coins the merchant class. This works well except for the elegant polo sticks that preceded the clublike Wands. Here is a modern version: Wands can represent working people, Cups the arts and social services (including religious figures), Swords the military and police but also law and government, and Pentacles businesspeople and managers.

In the late eighteenth and early twentieth century, people saw mythology in the suits. For some, they suggested the four Grail “hallows,” to use the term in Caitlin and John Matthews’ Arthurian Tarot. Cups are the Grail itself, the supposed chalice used by Christ to introduce communion at the Last Supper (“This is my blood …”), then used to collect his actual blood when he hung on the cross. The other suits derive from a spear, a sword, and a disk that appear in the Grail stories. However, the Grail stories are not that consistent, some with more objects, some with fewer, and even the Grail itself sometimes appears in early stories as a magical stone, like the philosopher’s stone of the alchemists.

Another mythological theory sees the suits as four magical “talismans” of Celtic gods and goddesses—the Spear of Lugh, the Cauldron of Dagda, the Sword of Nuade, and the Stone of Fal. Some see these, in fact, as the original Grail objects that later became Christianized when the Pagan Celts converted. As with so much else in Tarot, this particular cultural tradition fits so nicely, it almost doesn’t matter that we know the cards come from a different part of the world. What works, works.

Éliphas Lévi saw biblical origins for the suits. The Wands came from the “flowering rod of Aaron,” Moses’ brother and high priest. In the story, his wooden staff flowered as a sign that God favored him and his descendants. Lévi identified the Sword with King David and the Coin with the gold shekel of ancient Israel (the weakest connection, it seems to me). The Cup he gave to Joseph (the one from Genesis, not Jesus’s human father). In a passage that seems to me of meaning for Tarot readers, a servant says, “This is the cup from which my lord drinks, and which he uses for divination.” I sometimes speak of diviners as “the tribe of Joseph.”

Biblical figures spoke to Lévi, who after all took on the tribal name of the Hebrew priesthood—Aaron and his descendants were Levites. The modern Pagan revival, along with the occult interest in the Mysteries, have brought back Greek, Egyptian, and other gods and goddesses into our consciousness. My personal interest (maybe loyalty would be a better word) lies with the Greeks, and here too I think we can find almost perfect matches. Wands belong to Hermes, god of magic, swiftness, and change, and wielder of the caduceus, the ultimate magic wand. Cups, so often seen as the suit of love, give us Aphrodite, goddess of love, beauty, and sensuality. The “element” (see below) for Cups is water, and Aphrodite was born out of the sea. Swords go with Apollo, for this is the suit of mind, and the Greeks saw Apollo as the bringer of civilization and the patron of the arts and healing. But Apollo was also a warrior and conqueror, and so signifies the violent side of Swords. We also might see Swords as Athena, warrior goddess of wisdom and justice (though Swords probably should go with a male figure). Pentacles/Coins, the most earthly and material suit, evokes Gaia, goddess of Earth itself. These are my own associations with Greek gods. You can do something similar with other mythologies.

We also can relate the suits to the first four cards of the Major Arcana. Wands go with the Magician, Cups with the High Priestess, Swords with the Emperor, and Pentacles with the Empress. As with so much else, it does not quite work, for even though both the High Priestess and the suit of Cups belong with the element of water, the Empress embodies the qualities of Cups as much as those of Pentacles.

Gertrude Moakley, a scholar of the Visconti-Sforza Tarot, has identified each suit with one of the cardinal Virtues of the Middle Ages. Wands represent Fortitude, Cups Temperance, Swords Justice, and Pentacles (Coins) Prudence. If these terms sound familiar, we’ve seen them before—in the Major Arcana cards of Strength, Temperance, Justice, and the Star. If a Virtue “rules” each suit, we can see how the individual cards fulfill or fail that quality. For example, would the Six of Wands show a different side of Fortitude than the Nine? Which one is closer to the Virtue? A Tarotist named Marcia Massino has developed this approach with the Rider deck, though she does not follow Moakley’s choices for Cups and Pentacles. She sees Cups as Faith and Pentacles as Charity (giving your money away rather than saving it prudently). She looks at each card as a “triumph,” or a “test,” of the Virtue. Consider the Six of Pentacles.

At first glance, it may seem the perfect fulfillment of Charity—a man in wealthy clothes giving coins to beggars. But is it really virtuous to have them on their knees? And what of the way he seems to have balanced the scales and gives only a small amount? Massino’s approach can be valuable, especially with the Rider or other decks that show action scenes on each card. Set out the Swords cards from your deck. Which cards fulfill Justice, and which ones distort or overturn it?

We can create a modern version of the four Virtues by looking at each suit as having a special function. I would say that Wands inspire us to action, Cups serve healing, Swords serve communication and/or conflict, and Pentacles help us understand money and work. Consider the Two and the Three of Cups, again in the Rider.

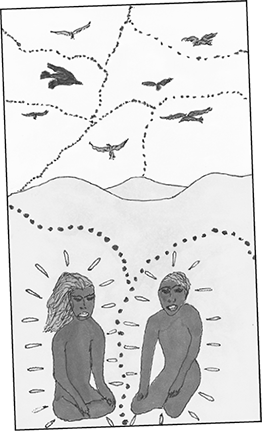

below: Shining Tribe Seven of Birds & Eight of Birds

right: Rider Six of Pentacles

below: Rider Two of Cups & Three of Cups

The Two can help us heal our experiences around romantic relationships, the Three can heal our friendships. This is because both present an ideal image.

Now look at the Seven and Eight of Birds in the Shining Tribe.

The Seven here shows us how to communicate, for we see two figures, each in his own territory, yet they talk—and listen to each other—with great energy. The scene was inspired by the Australian Aborigine practice of tribes meeting each other at a border, and each person literally singing his or her portion of the “songlines,” that is, the tribal map, to the person on the other side of the border. The Eight shows an even more basic issue of communication: finding the words and the ideas to express yourself.

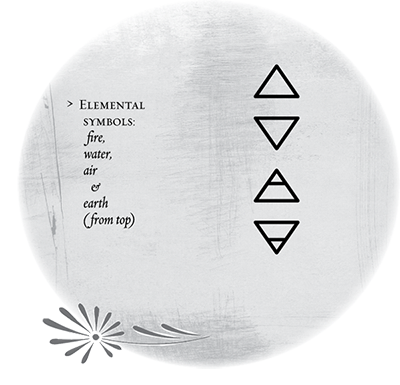

By far the most common association with the suits in modern Tarot is the four “elements”—fire, water, air, and earth—first identified by the Greek pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles. In ancient times, people asked a basic question: What is the world made of? Do all the millions of creatures and rocks and stones and rivers arise out of fundamental qualities? Today we talk of subatomic particles and the ninety-two (natural) elements of the periodic table, but in the past people saw things as outgrowths of the four qualities listed above. Fire and water were primary, with air and earth as more complex levels, almost a second generation. We can see this in their symbols:

Again we find echoes of the Major Arcana, with the Magician and High Priestess as fundamental principles and the Empress and Emperor as more complex. We also find qualities of male and female—yang and yin, to use the Chinese terms—in the suits, with Wands and Swords as male/yang and Cups and Pentacles as female/yin.

Just as we modernized the four social classes, we can see a new version of the elements. Water, air, and earth become the three common states of matter: liquid, gas, and solid. Fire represents the chemical transformation from one state to another. If we heat ice (the solid form of water), it first melts into water, then boils off into steam (the gaseous form).

While most Tarot people agree on what the elements are, they disagree on which ones go with which suits. As usual, the Golden Dawn forms the standard, which runs as follows: Fire-Wands, Water-Cups, Air-Swords, Earth-Pentacles. Variations include Wands as Air and Swords as Fire (notably in Nigel Jackson’s Medieval Enchantment Tarot), or Wands as Earth and Pentacles as Fire, or even Swords as Water and Cups as Air (in the Spanish deck El Grant Tarot Esoterico). Most decks, however, follow the Golden Dawn, and this is the system we will use here.

The Tarot also recognizes a fifth element, called quintessence, or ether. This is the element of spirit, embodied in the Major Arcana. The title “ether” does not refer to the gas used as one of the first anesthetics. Instead, it describes a formless, undetectable substance that supposedly permeates all existence. Ether was thought to be the medium through which light waves traveled through space. An experiment in the late nineteenth century to determine the effects of ether produced the startling result that not only did ether not exist, but light seemed to travel the same speed no matter how you measured it. This led to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, which it seems to me could be called one of the great spiritual texts of the twentieth century (for more on this, see my book The Forest of Souls). Maybe instead of calling the quintessence ether, we should call it simply light, making the five elements fire, water, air, earth, and light.

Fire represents the first spark of creation, warmth, action, energy, confidence. Water expresses feelings, especially love and relationships, imagination, intuition, family. Air shows us the mind, which, like air, we cannot see but which affects us constantly. We can experience air gently, as in contemplation, or wildly, as in anger like a storm. Because Tarot shows air with a sword, we tend to see its destructive side. One reason I changed the suit to Birds in the Shining Tribe was to show mind as art, prophecy, and vision. The element of earth evokes solidness, stability. The modern emblem, Pentacles, suggests magic, so for many people Pentacles are the magic of nature. Wiccans use the five-pointed star, the pentagram, as the symbol of their religion, based on nature and the body.

Here is a recap of the suits with their various names and qualities:

Wands (Batons, Rods, Staves, Trees): Fire, male, basic; action, optimism, adventure, forcefulness, competition.

Cups (Chalices, Vessels, Rivers): Water, female, basic; emotion, love, relationship, imagination, happiness, sadness, family.

Swords (Blades, Birds): Air, male, more complex; mental activity, conflict, heroism, grief, justice, injustice.

Pentacles (Coins, Disks, Stones): Earth, female, more complex; nature, work, money, possessions, security.

Major Arcana (trumps, keys): Light, androgynous/hermaphroditic, spirituality; Hermetic ideas, exile and return, teachers, liberation.

Here is a simple diagram that shows the suits and basic attributes:

|

Wands |

Cups |

Swords |

Pentacles |

|

Fire |

Water |

Air |

Earth |

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Basic |

Complex |

||

None of these qualities exist in isolation but combine, conflict, and move in and out of each other. The primary way we experience this is through readings, where the cards come together in endless variations and patterns.

Wands and Cups both tend to be positive and optimistic, with Swords and Pentacles darker, more difficult. At the same time, Wands and Pentacles deal with action and work, things outside ourselves, while Cups and Swords deal with the intangible qualities of emotion and thought. Notice that in the usual listing, Wands and Pentacles are literally on the outside, with Cups and Swords interior. Think of the four suits as dancers in one of those nineteenth-century ritualized dances, in which couples pair up, then shift, then come back again. No single pair can do the dance alone; it requires all four. And maybe the Major Arcana provides the music.

Before we look at the numbers, we need to consider one more symbol of four that is vital to the Minor Arcana. This is the so-called Tetragrammaton, the four-letter Name of God in Hebrew, usually translated as “Lord” in English Bibles. We have seen this before, in the Major Arcana cards of the Wheel of Fortune and Temperance. Here, again, is what it looks like:

Tradition regards this word as unpronounceable, a mystery rather than a name in the narrow sense of a title. Kabbalists often just spell it out, Yod-Heh-Vav-Heh. The first and third letters, Yod and Vav (Hebrew reads from right to left, so the Yod is on the right), appear somewhat phallic, with the Vav an extension of the Yod and looking like a sword (the word Vav actually means “a nail”). The two Hehs, the second and fourth letters, resemble upside-down vessels with an opening at the bottom to pour out what is poured out into it.

Thus, just as the Yod and Vav represent the masculine, so the Hehs give us the feminine.

|

Wands |

Cups |

Swords |

Pentacles |

|

Fire |

Water |

Air |

Earth |

|

Yod |

Heh |

Vav |

Heh |

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Kabbalists see the Name as a formula of creation, and this concept can help us understand the suits and their relation to each other. Yod—Wands—is the first spark, or desire, to create, coming directly from the Spirit. The first Heh—Cups—receives and germinates the creative urge. Genesis tells us, “There was darkness on the face of the Deep. And God said, Let there be light.” The light penetrates the dark deep, Yod enters Heh. Vav—Swords—develops the original spark, the way the letter extends the short, droplike image of Yod. Finally, the second Heh—Pentacles—shows us the finished creation. This pattern holds for the cosmos and also for anything created, from a baby to a painting to a table. We can see the pattern in the form of a triangle.

We will look at the Tetragrammaton again with the court cards.

Numbers

An invocation to the numbers in the Minor Arcana:

One for unity and the movement of power

Two for duality and coming together

Three for creation, whatever is born

Four for structure, the directions of Earth

Five for bodies, and roses, and Venus

Six for the love that moves generations

Seven for spheres and music and color

Eight for infinity and eternal return

Nine for gestation, the moons of our birth

Ten for our fingers and the toes of our feet

The 2,000-year-old Sefer Yetsirah (Book of Formation) tells us that the Creator made the world with ten numbers, not nine and not eleven. Recently, a friend of mine asked me why Jewish tradition requires ten people for a minyan, or quorum, to enact a service. He looked startled when I told him it’s because we have ten fingers. To me, all spiritual ideas come from actual existence—As below, so above. The numbers twelve and seven represent the heavens—twelve signs, seven visible “planets”—but four and ten, four suits, ten numbered cards, come from our bodies. Our hands, with their ten fingers, enable us to create and build a reality out of our ideas and desires.

The numbers one through ten have fascinated people for millennia. The most important interpretations come from Pythagoras, the founder of one of the first mystical schools known to history, and of course Kabbalah, with its ten sephiroth on the Tree of Life. The two systems do not always match. With Marseille-style decks that have no pictures on the pip cards, readers can choose a system and simply apply it to whatever card comes up. For example, if you decide that two means choice, then the Two of Cups might represent an emotional choice or a choice between two lovers.

Most modern decks, however, follow the Rider, where scenes appear on every card. For better or worse, the Rider established the modern tradition. If you join an email list on Tarot and ask, “What does the Eight of Swords mean in a reading?” almost all the responses will refer to Pamela Smith’s vivid scene of a woman tied up and blindfolded. And people will not say, “In Waite and Smith’s picture of a blindfolded woman…” but rather “The blindfolded woman in the picture…”

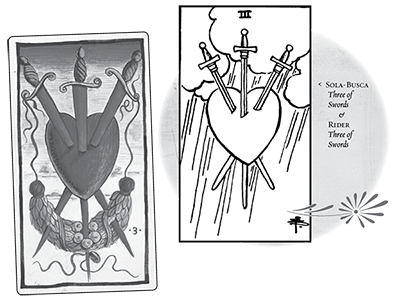

As far as I know, no record exists of how Pamela Colman Smith chose her scenes. A small handful resemble cards from an early and obscure Italian deck known as the Sola-Busca that Smith might have seen in the British Museum.

Once Smith painted her pictures, they transcended the formulaic descriptions given as their meanings. These formulas came from various sources, in particular the meanings described by an eighteenth-century French fortuneteller and Tarot designer named Eteilla (his original name, Alliete, spelled backwards, presumably to make it more exotic). Waite wrote of Smith’s paintings that “the pictures are like doors which open into unexpected chambers, or like a turn in the open road with a wide prospect beyond.” And the doors have continued to open for generations of Tarotists. The Tarot has become an organism, evolving constantly as people see new and subtle possibilities.

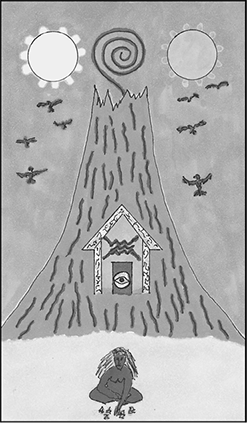

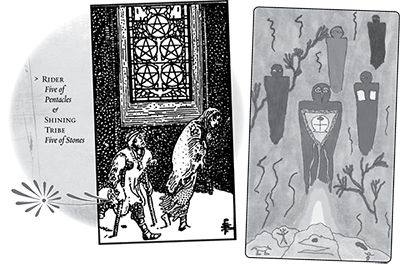

Though the images in the Shining Tribe Minor Arcana do not resemble the Rider scenes, they often engage in a kind of dialog with them. So, for example, the Five of Pentacles in the Rider shows a kind of misery that at first seems only physical—two injured people limping in poverty in the snow. When we look closer, we see a church with a window but no door that we can see for them to seek sanctuary. Thus the card suggests to many people a spiritual illness as much as a physical one. The Shining Tribe Five of Stones, inspired by a Native American canyon painting hundreds of years old, shows an intense spiritual healing, with beings coming out of the rock. After I had done the picture, I discovered that contemporary Indians call the original canyon picture “The Ghost Healers.” Tarot often seems to reach across space and time.

If the Minor Arcana consisted only of the Rider deck and its descendants, we could devote our study entirely to creative responses to Pixie’s drawings. This was the approach I took in my earlier book Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom, Part Two. But not only would that deny the Marseille and earlier decks, and the many modern decks with a different approach, it also would deny us the chance to engage the various ways people have understood the meanings of numbers. So, just as we did with the four suits, we will look at a range of ways people have understood one through ten. Hopefully, this will give people the tools to create their own sense of what these cards can mean. You might choose to focus on a particular approach. For example, you might pay special attention to the themes from the Rider cards, given below (and further explored in the individual cards), or the meaning of the numbers in Kabbalah or Pythagoras. A variety of approaches can give you the tools to develop your own interpretations.

Here is an experiment we did in a recent class of mine. You can try it with a small group of your own. Everyone took a sheet of paper and drew three swords in any kind of pattern they liked. Then we interpreted just that, the figures the swords created. No two were the same, and all were suggestive. We discovered that we did not need to see a scene to get a sense of meaning. As a further step, add one symbolic image somewhere in the picture. A rose, a house, a tree, a hand, whatever seems to fit or simply what comes into your mind. You can continue this with all the numbered cards and create your own Minor Arcana.

The “Invocation” above, written especially for this book, describes what I would call basic qualities of these numbers. Some bring in qualities we’ve found in the Major Arcana, but only because the Majors also involve numbers: the fundamental polarity of one and two; the fact that three evokes mother-father-child; the structural qualities of four; the way five appears in the human body (four limbs plus the head), five-petaled flowers, and the pattern Venus makes in the sky; six as two times three and thus generations; seven as the planetary spheres, colors of the rainbow, and chakras, and the notes in the musical scale; the shape of the number eight as an infinitely returning loop; the nine months of pregnancy; and the ten fingers of our hands that allow us to do such things as write books on the Tarot.

Here is a list of number attributes that combine basic concepts with everyday experience. With each, I will give at least one example of how we might apply it to the interpretation of the Minor Arcana.

1. Whatever is singular, essential. The Ace of Cups might be simple happiness, the Ace of Swords strong, clear thinking.

2. Choices, but also dialog, combinations. The Two of Pentacles could indicate a choice around money or work.

3. Group activities, family, but also triangles, jealousy. Since Swords carry themes of battle, the Three of Swords might signify conflict in a group, while the more harmonious Pentacles would mean people working together (as suggested in the Rider scene).

4. Structure, stability (for why four means structure, see the Emperor and the previous section on the four suits), but also conventionality, conformity (remember the old expression, a “square”?). The Four of Swords would suggest very structured, logical thinking, the Four of Cups a family where everyone has a fixed role.

5. Time, which is to say change, development, growth, and decay. The Five of Pentacles would mean a change in economic or physical conditions, but not necessarily for the worse.

6. Harmony, opposites reconciled, strong relationships. This comes from that six-pointed star as a combination of an upward and downward triangle. The Six of Wands in a work reading would suggest a dynamic environment where people work very well together. The Six of Cups in a love reading would indicate a reconciliation or a couple that seem opposite but function very well as a couple.

7. Creativity, inventiveness, possibilities. The Seven of Swords could suggest new ways of thinking, new plans.

8. Cycles, patterns, or a situation that continues indefinitely. The Eight of Cups might indicate someone who chooses the same sort of partner over and over.

9. Completion, an idea derived from nine as the last single-digit number and the nine months of pregnancy. The Nine of Pentacles suggests the completion of a project.

10. Abundance of the quality of the suit, possibly excess, with a hint of instability, something that doesn’t last. The Ten of Pentacles could show prosperity, the Ten of Wands tremendous energy.

Try this for yourself. See if you can come up with a list of associations for the numbers, then think of how they would translate into each suit. You might want to use a Marseille-type deck—without specific action scenes, just the correct number of symbols on each card—to inspire you. As we look at some of the other number systems, the Pythagorean and the Kabbalist, we will similarly pause to consider how the concepts might apply to particular cards.

Rider Themes

And now, by contrast, my own current sense of themes of the Rider cards by number. Since Smith’s pictures do not actually follow a distinct system, we cannot easily say, for example, that all threes mean the same thing. But if we lay them out together, that is, all fours, all sevens, and so on, we may find some common threads. I call this my “current sense” because it changes—evolves—over time, through readings and classes. If you have the Rider or one of its variations, you might want to set out each group as you read through this list. See how your own sense of the pictures compares to mine.

All Rider Aces

Aces—a gift of the spirit. In each card, a hand emerges from a cloud and holds out the emblem of the suit, as if we just need to reach out and take it. We see versions of the letter Yod, from Yod-Heh-Vav-Heh (see above, the four suits), as leaves in Wands, drops of water in Cups, sparkles of light in Swords. These symbolize divine grace, the idea that the power of the suit just comes to us at this moment in our lives. There are no Yods in Pentacles because that suit represents solid matter.

All Rider Twos

Twos—I used to think of this group as relationship issues. But that only applies to the Cups, where we see a man and a woman pledging their love, and paradoxically the Swords, where a woman seems to close herself off from all possibility of relationship. To deny or block something still keeps it as the subject. But what of the Wands and Pentacles? Maybe the twos represent choices or the attempt to find balance.

All Rider Threes

Threes—a flowering, or something created from the energy of the suit. For Wands, this is rootedness and/or new opportunities, for Cups friendship, for Swords heartbreak, for Pentacles masterful work.

All Rider Fours

Fours—structure, from the simple bower of Wands (fire does not like to be contained), to Cups’ hesitation to try something new, to Swords’ retreat into restfulness, to Pentacles’ use of money or possessions to protect and define our lives.

All Rider Fives

Fives—life’s difficulties. One of the most consistent numbers (see the Kabbalist number meanings below—sephirah five, Gevurah, as the harshest place on the tree). While fiery Wands get energized by conflict, Cups grieve, Swords suffer a humiliating defeat, and that couple in Pentacles find themselves crippled, penniless, and walking barefoot through the snow.

All Rider Sixes

Sixes—unequal relationships. I discovered this in a class recently, when I noticed that in each card one person stands above, and superior to, a single person (Cups), a pair of people (Swords and Pentacles), or a whole group (Wands). I’m not sure just why this should have emerged for the number six, which most people consider a number of harmony, but it seems one of the most consistent themes of any of the numbers.

Tarotist and teacher Ellen Goldberg offers a more generous view, one more aligned with the Kabbalist title of “Beauty” (see below). In fact, for her, generosity is what the Rider sixes are about. The Wands shares his optimism and confidence with those who walk alongside him, the older child in the Cups gives a flower as an expression of the beauty of nature, the man in Swords assists those who are suffering, and the man in the Six of Pentacles has so much money that in order to balance the scales, he must give some of it away.

All Rider Sevens

Sevens—action, or maybe the contemplation or awareness of action. The figure in Wands knows he must stay on top, the Cups fantasizes possibilities, the Swords character enjoys his own cleverness, the Pentacles farmer looks at his garden with satisfaction or concern (depending how you read his expression).

All Rider Eights

Eights—movement. Wands fly through the air, someone leaves Cups behind, in Swords a blindfolded woman needs to discover that nothing actually prevents her from freeing herself, and an artisan develops his skill, creating one Pentacle after another.

All Rider Nines

Nines—intensity, the element at a high degree. We see Wands’ courage and strength, Cups’ enjoyment of life, Swords’ grief, and Pentacles in a lush garden.

All Rider Tens

Tens—excess. The responsibilities of Wands bend the back, Cups celebrate family happiness, Swords suffer horribly (the excess in this card leads me often to interpret it as overly dramatic or hysterical), and Pentacles live in splendor but possibly do not see the magic outside their material comfort (the family inside the arch do not look at each other, and none of them notice the mysterious old man sitting outside the gate).

Pythagoras

From the particular to the principle. The Rider cards work through dramatic scenes, inviting us to speculate about their actions, facial expressions, and body language, as if we can see a brief instant in an unknown play and we are left to invent the plot and characters for ourselves. But let’s go back to the numbers. We will look briefly at Pythagorean and Kabbalist ideas and how they might apply to the Minor Arcana.

For this very short description of Pythagoras and numbers, I am indebted to the ideas of numerologist Carey Croft and Tarotist John Opsopaus, creator of the Pythagorean Tarot. All mistakes are mine alone.

Like the anonymous author of the Sefer Yetsirah, Pythagoras believed in the numbers one through ten as the basis for all existence. These numbers could be arranged as a pyramid based on one through four:

|

* |

|

* * * * |

|

* * |

or |

* * * |

|

* * * |

* * |

|

|

* * * * |

* |

We will see in a moment that the inverse, 4-3-2-1, is possibly more meaningful than the more obvious 1-2-3-4. Here are the individual numbers. Notice that they include connections to gods and goddesses. Readers of this book will know that I often use this approach. For me, it makes abstract ideas come alive in the image of archetypal beings and stories.

1. Monad. Here we find unity, first principles. Pythagoras considered one as apart from all the numbers that come after, and we find this reflected in many Tarot decks, where two through ten will show details and complexity, but the aces will display an elegant version of the symbol. The Golden Dawn, too, put the aces in a separate category, leaving the other thirty-six cards (two through nine in each suit) to represent the thirty-six “decans” of the zodiac (see below). As the monad, the aces contain all the qualities of the suit but undifferentiated, that is, everything together. We will find the same idea in the Kabbalist sephirah one, Kether. Pythagoreans identify one with Zeus, father and leader of the gods, whose mind was said to be unfathomable, even to the other gods.

2. Dyad. The principle of separation, which gives the possibility of creation. A gap opens, creating an Above and Below so that a world can emerge. Pythagoreans identify the dyad with Rhea, mother of Zeus. The twos therefore can signify dialog, communication, the potential to create something, with each suit having its own quality.

3. Triad. Energy bridges the gap created in the dyad. It restores unity but now in the created world. Pythagoreans identified the three with Artemis, the moon goddess. The moon is the image of the Triple Goddess, Maiden-Mother-Crone, to go with the lunar phases of waxing-full-waning. In Tarot, the Empress, card three of the Major Arcana, embodies the Great Mother (two is actually the card of the lunar feminine).

For an experiment, set out the threes from a Tarot deck, preferably one without scenes, like the Marseille:

Now see if you can imagine them as the mother energy of each suit. What would Mother of Wands be? A source of great energy and optimism? The Mother of Cups might pour forth love. What would you see in the mental Swords and physical Pentacles? The Pentacles, of course, could symbolize actual motherhood, especially if the Empress also appeared.

4. Tetrad. We get a new duality but more complex. Four gives us structure, stability, wholeness. Pythagoras taught that the soul contains four aspects, and here we find a matching idea in Kabbalah, where each person is said to have four souls, aligned with the four worlds and thus the four suits. Maybe the four could designate the soul. What would your Wands soul be like? Your Pentacles soul? How would they be different? (See the Four Worlds reading in the Readings chapter.)

Four completes that basic structure, 1-2-3-4, which adds up to 10. If we invert the order, and then remove the 1 as a separate category, we get 432. This number is 1/60 of the Great Year, the 25,920 years it takes for the zodiac to make a complete rotation around the Earth. The numbers 432 and 108 (1/4 of 432) appear very frequently in myth and spiritual traditions. The Buddhists will recite 108 prayers, the Hindus tell of four ages, or Yugas, each one lasting 432,000 years. The god here is our friend Hermes, whose four-sided stone pillars, called herms, marked roadways, in particular lining the road into Athens.

5. Pentad. To the four directions of earth we add a fifth dimension, allowing us to become aware of Above. Five also adds that fifth element, quintessence, to the four physical elements. Thus, with each suit we might see the five as an opening to a higher level of consciousness. This idea stands in contrast to the Kabbalistic sense of five as very harsh.

Since Pythagoras considered ten the number of perfection, five becomes a demigod, maybe the ability to glimpse our perfection as immortal beings while still living in the “real” world. Five also shows the human body as the image of the divine, for if we stand with arms and legs out, we form a pentagram.

6. Hexad. If the fives open a way to higher consciousness or simply new territory, then six defines the territory by establishing directions, including above and below with the four horizontal directions. Six represents harmony (compare Beauty in the Tree of Life). Here is an interesting quality of the numbers: 1+2+3=6. Going to the next group, 4+5+6=15, which reduces to 6 (1+5). At the highest single-digit level, 7+8+9=24, which also reduces to 6. Six represents a recurring harmonic energy. The number six goes with Aphrodite, goddess of love, and as we have seen, the six-pointed star unites masculine fire and feminine water in an image of interpenetration. For each suit, six might show harmony. What would harmony of Swords be? A mind in peace? Different ideas or mental approaches that work together? Try this for each of the suits.

7. Heptad. The Pythagoreans consider seven a second monad, a new energy to be followed by the final numbers 8, 9, and 10, just as 1 is followed by 2, 3, 4 (7+8+9+10=34, which reduces to 7). Seven combines three and four, and we can put this in visual terms as a triangle above a square—spirit above matter.

The ancients linked seven to Athena, warrior goddess of wisdom, who sprang whole from the head of Zeus. Seven adds the center to the six directions, and thus becomes both dynamic and aware. And seven represents the cosmos, both above (the planets) and below (the chakras). The sevens, therefore, would show a dynamic, creative force. In Wands this would be fiery energy, in Cups emotional force, in Swords powerful ideas, and in Pentacles growth and success.

8. Octad. Eight is two times four, a double square, and thus the earth, matter. It reestablishes stability after the dynamic seven. John Opsopaus tells us it bears such titles as Safety, Foundation, even Paradise Regained. To the seven planetary spheres we add an eighth, the divine sphere that encloses all the rest. Think of the eights in the Minor Arcana as different kinds of stability. Two was Rhea, mother of the gods as mother of nature, but eight (two to the third power) becomes Rhea as spiritual mother.

9. Ennead. Some people may recognize this word from “enneagram,” a nine-sided figure said to contain all aspects of life and the self. As the final single digit, nine signifies the end of a process and limitations (like Saturn as the outermost visible planet). But nine also brings birth, for a human pregnancy runs nine lunar months. As 3 x 3, nine symbolizes a third level of completion: 1-3, 4-6, 7-9. Its titles include Fulfillment, Completion, Perfection. If three represents all the trinities, what might three times three indicate? Maybe the trinity of trinities takes us to levels beyond knowledge. What would the fulfillment of Wands be? (Probably not the somewhat beaten-up looking fellow in the Rider card.) What would unknown levels of Cups look like? (Again, the smug fellow in the Rider Nine of Cups is probably not it.) The Pythagoreans identify nine with Hera, Zeus’s sister and wife. Since Zeus is one, and 9+1=10, the following card, the decad, symbolizes the divine marriage between the two great figures.

10. Decad. This is the supreme number for Pythagoreans, symbolizing higher unity, as if one begins a process of growth that culminates in nine, and then begins again at a higher level with the first double-digit number. What might the greater consciousness of Swords look like? Possibly this might give us a mental awareness of truth beyond logic and empirical knowledge—an opening to the Major Arcana, whose element I’ve identified as light.

Ten gives us balanced wholeness. Here are some titles from John Opsopaus’s description of ten: “Universe … Heaven. Alliance. Fate … Eternity …Power.” Because it consists of 1+2+3+4, the decad contains all the basic principles. It returns to one, but with the awareness of having gone through all the other numbers. This may remind us of the World card, which returns to the wholeness of the Fool, but with an awareness the Fool found impossible. As well as symbolizing the divine marriage of Zeus and Hera, the decad belongs with the god/dess Hermaphroditus, the child of Hermes and Aphrodite who combines male and female perfection. The World card sometimes bears the title “Divine Hermaphrodite.”

Set out the four tens from any deck without specific scenes on the cards, like the Marseille:

If all you have is a deck with illustrated scenes, take four sheets of paper and draw ten Wands on one, ten Cups on the second, and so on. Now consider each one, and see if you can apply some of the ideas about the decad to the suits. What might “Heaven” of Wands be? “Power” of Pentacles? “Eternity” of Swords? “Universe” of Cups?

Kabbalah

And so we come to Kabbalah, probably the main source for number ideas in the modern, Golden Dawn–based Tarot world. It’s often seemed to me that one problem with the Tree of Life and Tarot is that the tree actually works better with the Minor cards, or at least makes them seem the more important part of the deck. While the twenty-two lines on the tree, originally designed to match the twenty-two Hebrew letters, fit very well with the twenty-two Major Arcana trump cards (though with arguments over the correct order), the ten sephiroth are clearly the primary symbol. And these go perfectly with the Minor cards. Four worlds with one through ten in each, four suits with ace through ten in each.

We’ve seen it before, but here it is (see opposite page), with titles for the sephiroth in Hebrew and English, and the cards they go with (remember, Hebrew goes from right to left, and so the higher numbers will be on the left).

The question is, do we go up or down? We’ve just seen how Pythagoras unquestionably counts from one to ten, with ten as supreme. But Kabbalah tells us that the physical world exists in ten, Malkuth, at the farthest and “densest” distance from divine Kether. This is where we live, and if we wish to advance closer to Spirit, we must climb up the tree. Waite, in his Pictorial Key to the Tarot, lists the Minor cards from king to ace. It seems like counting down but, in fact, is going up the tree. In my book Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom, I followed Waite’s approach, but since then I’ve tended to look at the Minor cards in the usual order, ace to ten and page to king. I think of this as a developmental approach.

Since we have looked at various aspects of the Tree of Life before, I will keep the descriptions of the sephiroth brief. The astrological and color designations come from—where else?—the Golden Dawn.

Ace—Kether—Crown: The origin of all things, complete in itself, undifferentiated, pictured as white light, beyond all the distinct parts of creation. Instead of a particular astrological association, Kether is the cosmos. Kether is the source, everything else comes out of it. If the Ace of Cups is the source of Water energy, what might it mean in a reading? How about the Ace of Pentacles as the source of everything earthly? We might describe these cards as powerful, basic, a strong experience of the element.

Two—Hokhmah—Wisdom: Here we find a tricky situation. Two is usually the basic feminine number (see the High Priestess), and in fact, Hokhmah, called Sophia in Greece (the word philosophy originally meant “the love of wisdom”), appears almost as a goddess in the Bible and other texts. In classic Kabbalah, however, Hokhmah becomes the Father, the head of the masculine pillar on the right of the tree. The Golden Dawn identified Hokhmah with the entire zodiac and gave it the color gray. Hokhmah represents our highest wisdom. What might the Two of Pentacles mean as the highest wisdom of earth?

Three—Binah—Understanding: Here we find the Great Mother (the Empress), source of the seven lower sephiroth. If we look at the tree, we see that the top three sephiroth form an upward-pointing triangle, while 4-5-6 and 7-8-9 form downward triangles. This creates a gap between the top three and the lower seven, with 1-2-3 called “supernal,” of a higher order than the others. Binah gives birth to those seven lower ones. As the quality of Understanding, it can relate to life experiences and the awareness that comes through them. The color here is black, the planet Saturn. The Three of Swords might embody mental understanding, seeing how the pieces fit together. The Three of Cups would show us emotional understanding.

Four—Chesed—Mercy: Four and five, Mercy and Power, form a pair. We also call them Expansion and Contraction. Mercy, on the masculine side of the tree, is loving and generous, a constant outpouring. This contrasts with the usual idea of four as structure and stability, and I’m not sure we can easily combine the two ideas. If you want to try a strictly Kabbalist approach to the Minor Arcana, try the same exercise suggested for the Pythagorean threes. Set out the fours from a deck without specific scenes or draw them on sheets of paper.

Now imagine what a benevolent outpouring of Wands might be, and one of Cups. How would a Chesed of Swords differ from a Chesed of Pentacles?

Five—Gevurah—Power. If the universe only expanded, if people only acted generously, nothing would sustain itself. We could not learn if our experiences never tested us. And so we find harsh Gevurah, which the Golden Dawn aligns with the planet Mars and the color red. The Kabbalist meaning of five informs the Rider deck images probably more than any other number. We see conflict in Wands, mourning in Cups, defeat in Swords, and poverty and illness in Pentacles. Can you think of alternatives for these choices? Harshness of Wands might mean something burning, of Cups someone shut down emotionally.

Six—Tipheret—Beauty. At the center of the tree we find Beauty, whose “planet” is the sun and color is yellow. The Jewish Kabbalists associated this sephirah with Jacob, their image of the ideal man (personally, I prefer his son Joseph). The Christian Kabbalists put Christ in the center, while the Golden Dawn opened it to the whole range of dying and resurrecting gods, especially those known for their beauty, like the Norse god Balder. Here in the tree’s center, we find a confluence with the Pythagoreans, who see six as Harmony. What would the Beauty of Wands be? Glorious flame? Life energy and health at their most radiant? How about the Beauty of Pentacles? Lush nature, a wondrous oasis?

Seven—Netzach—Victory. The title of this card has always struck me as vague. Some call it the Victory of God, but what exactly does that mean? For the most part, the Rider deck shows active images here, a quality I followed in the Shining Tribe. We get a more specific sense of this sephirah from the Golden Dawn’s designation of it as the place of the planet Venus, realm of emotion. The color is green. This gives us the vertical line of Wisdom (2), expansive Mercy (4), and emotional Victory (7). What might the emotional Victory of Swords be? Delight in the mind’s ability to solve problems? Cups might become extremely emotional, or perhaps the Seven of Cups might indicate a triumph of love.

Eight—Hod—Glory. Just as with Netzach’s “Victory,” Glory has always sounded abstract to me. And again, the Golden Dawn assignation, this time to Mercury, allows for a clear sense to emerge. In fact, clarity, at least mental clarity, belongs to Mercury, the realm of the mind. And of course, the god Mercury is the Roman version of Hermes, the legendary “inventor” of Tarot itself (see the Magician—and numerous others—for more on Hermes). The Greek name for Venus is Aphrodite, so that if we combine eight and seven we get Hermes-Aphrodite, or Hermaphrodite, that complete being we associate with the World card and which Pythagoreans see as the number ten. And if we put seven and eight together, we get seventy-eight, the number of the cards in the Tarot. The order of these planetary realms carries an important truth. If we seek to ascend up the tree from Malkuth, the place of our busy, distracted lives, we pass through Yesod (sephirah nine) and then come to Hod, the place of mind, and after that Netzach, the world of emotion, and only when we have experienced both do we go on to Tipheret, where all the qualities come together in Beauty. Put another way, emotion is higher on the tree than mind. The color for Hod is lavender. If eights signify mind, what would the mind of Pentacles be?

Nine—Yesod—Foundation. Here, too, I value the Golden Dawn’s attribution, in this case the moon. We should realize, by the way, that the Hermetic Order did not make their associations arbitrarily or conceptually but simply took the planets in order, beginning with the moon, the closest to Earth (Malkuth, sephirah ten), and moving outwards to Saturn (Binah). As we saw with the Major Arcana card, the Moon rules imagination, instinct, dreams, psychic awareness, intuition. As someone who has tried to champion imagination all my life, I can only agree with the idea of the lunar realm as the “Foundation” of our spiritual existence, the gateway to the rest of the tree, as well as the primary way that spiritual energy spirals down into our daily lives. The color here is silver.

If the primary quality of Yesod is lunar imagination, how might individual nines express this? Maybe some would conflict. For example, the mental approach of Swords or the practical earthiness of Pentacles might be uncomfortable in the realm of the moon. We might get disturbing fantasies, disruptive dreams.

Ten—Malkuth—Kingdom. This sephirah represents the “real” world, our daily lives. The planet is Earth itself and the color a mixture of four different quarters. Kabbalists who think in hierarchical terms may describe Malkuth as “dense,” or “gross matter.” However, as Isabel Radow Kliegman says in her book Tarot and the Tree of Life, if we want to change something, ourselves or the world, we have to do it in Malkuth, for that is where everything happens. And if we want to ascend the tree to higher consciousness, we cannot just choose which one we like as a starting point. We must begin where we are, in Malkuth. Thus the ten should signify the solid reality of each suit, and here the Rider images, by far the best known, work well with the feminine suits of Cups and Pentacles. The latter, in fact, shows the Pentacles as a Tree of Life overlaying the scene. We see simple happiness in the Cups and prosperity in the Pentacles. By contrast, Wands and Swords show us oppression and mental anguish (not violent death, despite the picture).

Trumps and the Minor Cards

Let’s go back to something simpler. Consider the numbers in the Major Arcana. If we set aside the Fool, 0, and the World, 21, as both containing the totality of experience, we get twenty cards, two times ten. Thus, we can link each Minor card to two Majors. Here is one more chart:

|

Aces |

Twos |

Threes |

Fours |

Fives |

Sixes |

Sevens |

Eights |

Nines |

Tens |

|

1. |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

6. |

7. |

8. |

9. |

10. |

|

Magician |

High Priestess |

Empress |

Emperor |

Hierophant |

Lovers |

Chariot |

Strength |

Hermit |

Wheel |

|

11. |

12. |

13. |

14. |

15. |

16. |

17. |

18. |

19. |

20. |

|

Justice |

Hanged Man |

Death |

Temperance |

Devil |

Tower |

Star |

Moon |

Sun |

Judgement |

Decans

Before going on to the individual cards, we need to consider one more system modern Tarotists sometimes use for the numbered minors, at least two through nine in each suit. As described above, if we set aside the aces as the basic element, we get thirty-six cards. Since the zodiac contains 360 degrees, this gives us ten degrees for each card. Put another way, there are twelve signs and thus thirty degrees for each (360 divided by 12=30). For example, Wands are fire, and the three fire signs are Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius. Thus the Two of Wands becomes 1–10 degrees of Aries, the three is 11–20 degrees of Aries, and the four 21–30. Leo goes with cards five, six, and seven, while Sagittarius with eight, nine, and ten. Each decan—each card—is ruled by a planet. Paul Huson traces this system and its meanings to a fourteenth-century Arabic text, translated into Latin, called Picatrix (wonderful name), which not only listed the decans but gave meanings for each one. Although these meanings are often far from what we think of for the cards today (and were not in fact originally connected to Tarot cards but used only for astrology and magical talismans), they may have influenced the Golden Dawn’s interpretations for the Minor Arcana. Huson says that the Golden Dawn papers originally contained a text titled The Magical Images of the Decans, which seems to be an English translation from the Latin version of Picatrix.

This has been a long and extended summary of the varied influences and possibilities of the Minor Arcana. I have sought here to show the many ways we can view these cards, all valid in their own way, and maybe especially to “liberate” us from over-reliance on any one approach, especially Pamela Colman Smith’s compelling scenes for the Rider, or the Kabbalah. For one thing, we notice that these two often do not match up; that is, the Rider pictures often seem to have no relation to the Kabbalist theme for that number. Smith’s Six of Swords would not suggest “Beauty” of air to many people (and here is a curious fact of the Rider Swords cards: six of the ten cards show water).

I also have tried to suggest rather than dictate ideas; for example, asking with the Ten of Wands what “Heaven” of Wands might be rather than just giving my own suggestions. In the individual card listings below, I hope people will use the information and suggestions to come up with their own interpretations.