Magician: 1

Astrological correspondence: Mercury

Kabbalistic letter: ![]() Beth

Beth

Path on Tree of Life: Kether (Crown) to Binah (Understanding), second path

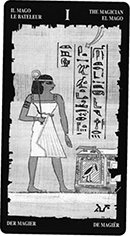

Just as with the Fool, the Magician has undergone a transformation over the centuries since the earliest Tarot decks. The most popular images today of this card show him as serene, powerful, with an infinity sign over his head and pointing his magic wand up towards the heavens as if to draw down divine energy. On his table lie the four emblems of the Tarot Minor Arcana, as if he is master of the physical world. He is indeed a “Magus,” as Éliphas Lévi called him, and as Aleister Crowley titled the card.

below: Magician cards from Visconti, Marseille, Rider, Golden Dawn Ritual, Egyptian & Shining Tribe

Now look at the older Marseille image. We see someone dressed somewhat like a court jester. There is no magical infinity sign above his head, yet the curved wide brim of the hat subtly suggests that image.

Instead of the symbols of the four suits, the table contains an odd assortment of objects: a knife, a couple of plain cups or containers, and several balls or pellets, along with a bag of some sort on the side, reminiscent of the bag the modern version of the Fool carries over his shoulder. What are these for? The French name, Bateleur (in Italian Bagatto), often translated as “juggler,” gives us the answer, for the word refers to a sleight-of-hand game played on the street with unsuspecting marks. The “juggler” places a small ball under one of two (or more often, three) cups, slides them around, then reveals where it is. When he invites someone to try it, the person usually gets it right the first two tries or so, but when serious money is placed on the table, the juggler’s hands move much more quickly—sometimes dropping the ball into the bag—and the person loses the bet. People today who have seen this “game” played on the sidewalks of New York or London may be surprised to know how old it is or that it was the original inspiration for the Tarot Magician. Thus, the grand Magus of the modern tradition is revealed to have his roots in someone who is at best a street entertainer, and at worst a con artist.

Here are some of the odd ways in which this card has developed over time.

Some Magician Meanings

Excerpted from Mystical Origins of the Tarot by Paul Huson.

Pratesi’s Cartomancer (1750): Baggatino, married man.

De Mellet (1781): The Mountebank.

Court de Gébelin (1773-82): The Thimble-Rigger.

Lévi (1855): The Hebrew letter Aleph, the Juggler. The Magus. Being, mind, man, or God; unity; mother of numbers, the first substance.

Christian (1870): The Magus: Will. In the divine world, the Absolute Being who contains and from whom flow all possible things; in the intellectual world, Unity, the principle and synthesis of numbers; in the physical world, Man, the highest of all living creatures.

Mathers (1888): The Juggler or Magician. Willpower, dexterity. Reversed: Will applied to evil ends, weakness of will, knavishness.

Golden Dawn (1888-96): The Magus of Power. The Magician or Juggler. Skill, wisdom, adaptation, cunning, always depending on the cards around it and whether or not it’s reversed. Sometimes occult wisdom.

Grand Orient (Waite, 1889, 1909): The Juggler. Skill, subtlety, on the evil side, trickery. Also occult practice.

Waite (1910): The Magician. Skill, diplomacy, subtlety, snares of enemies, the inquirer—if male. Reversed: Physician, magus, disgrace.

Notice that the split between mountebank and magus goes through much of the history of the card, including Waite in his two versions. The first cartomancers all assumed it symbolized the street performer, and it is not until Éliphas Lévi that we see something grander. But look how grand! Not just Magus, though he introduces the term, but also “being, mind, man, or God.” Paul Christian continues this theme, but notice how Mathers reverts to the Juggler and includes “will applied to evil ends, knavishness.” By using the concept of the reversed meaning, Mathers is able to suggest the Magician/Juggler’s good and bad sides. The Golden Dawn (founded by Mathers) includes “the Magus of Power” and “occult wisdom” but also “adaptation” and “cunning,” both qualities of the “Juggler,” that Baggatino with his table of tricks. Grand Orient (Waite) says primarily “the Juggler” but also adds “occult practice.” And notice how Waite, writing under his own name, gives “snares of enemies” in the primary meanings, but also “physician, magus, disgrace” in the reversed.

Is there no way to reconcile these two images for the card, the mountebank and the magus? Surprisingly, the full meaning of the Magician, and perhaps the Tarot itself, may depend on knowing both the grand magician and the trickster. Both attributes are embodied in the name of a Greek god who can be said to be the patron of the Tarot, Hermes.

When Antoine Court de Gébelin and Comte de Mellet pronounced the Tarot a book of ancient Egyptian teachings (in 1781—see Introduction), they were referring to the Hellenistic city of Alexandria, named for Alexander the Great, where Greek ideas and images joined with Egyptian. The esoteric traditions that sprang up in that time (the period before the Roman Empire) were attributed to the Egyptian god Thoth, associated with writing, magic, raising the dead, and wisdom of all kinds. Early occultists called the Tarot the Book of Thoth (a title used in the twentieth century by Aleister Crowley), with the idea that the god himself created the pictures and handed them to his human acolytes. The Alexandrians were Greek as much as Egyptian, and so they linked Thoth to a Greek god with similar attributes: Hermes, calling him either Thoth-Hermes, or Hermes Trismegistus, Hermes Three Times Great. Hermes Trismegistus was a god but also a great wise man, the legendary author of a complex series of sacred texts known collectively as the “Hermetica.” And yet, the name Hermes is vastly older than the mysterious figure of Hermes Trismegistus from Alexandria some two thousand years ago. Even though Homer describes Hermes, whom the Romans called Mercury, as a son of Zeus, and therefore fairly late, Hermes may originally have been one of the earliest figures in prehistoric Greece, for we know he was represented not by grand statues but by rough standing stones. Mythographer Walter F. Otto said of Hermes, “He must once have struck the Greeks as a brilliant flash out of the depths.”

This brilliant flash can be described as creation itself, the moment when the Divine says, “Let there be light.” To quote the Tao Te Ching once again, “Out of the Tao comes the One,” the oneness of the Magician, card 1, emerging—magically—from the formless Nothing of the Fool. The greatest magic act, writer Alan Moore tells us, is for Something to come out of Nothing.

For all that, the Greeks did not visualize Hermes as remote, or grand, or sitting on some high throne. Hermes was a god of both wisdom and knowledge (not the same thing), and it makes sense that the later Alexandrians would see him and Thoth as the same. But he also was a messenger, a guide to dead souls, an outsider, a prankster, a wild child, a symbol of the generative power of male sexuality—the Magician with his wand is the Tarot’s primary symbol of masculine energy—and a thief.

The Homeric Hymn to Hermes tells how baby Hermes, the very next day after his birth, slips out of his cradle and goes seeking adventure. Hidden within the dynamic energy of the Tarot Magician rises a spirit of play, for creativity can never be dry and purely intellectual but must always contain an element of simple delight. Baby Hermes comes across a herd of cattle, and being a god of magic, he instantly recognizes them as belonging to his big brother, Apollo, god of the sun, poetry, prophecy, and civilization. Hermes makes off with some of the herd, cleverly walking backwards to confuse any trackers. After a wild barbecue he returns to his cradle, where he pulls his blanket up and puts on an innocent face.

Wise Apollo is not fooled but marches in and furiously accuses his baby brother of theft. “Me?” Hermes says innocently. “I’m just a baby. I was born yesterday. I don’t even know what ‘cattle’ is.” When Apollo, unappeased, takes Hermes before their father, all-powerful Zeus, Hermes says, “I’m a frank person, and I don’t know how to lie.” (trans. Charles Boer) He then swears a solemn oath: “Not guilty, by these beautiful porticoes of the gods!” (Boer) Even as he says this, holding onto his blankie like an innocent babe, he winks.

Instead of being angry, Zeus bursts out laughing and orders the two of them—rational, grand Apollo and prankster Hermes—to reconcile. And then something special happens. For before he went after the cattle, Hermes created something. He saw a tortoise wobbling along and had a vision of what could be done with its shell. He killed it (there is a merciless quality to the Magician, tempered, at his best, by service), gutted the shell, attached reeds for a neck and strung seven strands of sheep gut down the length of it. Seven, remember, is the number of the planetary spheres and the diatonic musical scale, as well as the chakra centers in the body and the colors of the rainbow. Thus he created the lyre, the first musical instrument. When Zeus orders Hermes to make up with Apollo, Hermes gives him the lyre. In the ancient world, Apollo was known as the god of music, for harmonious sounds were thought of as the very essence of reason. But there is no beauty in harmony without inspiration, that flash of light out of the depths. And so, again, we get the Magician as dynamic creative energy.

Zeus then asks Hermes what he would like to rule over. Knowing very well that Apollo rules the great Oracle at Delphi, cheeky Hermes asks to be in charge of prophecy. Zeus refuses, but then Apollo says something remarkable. Prophetic vision may be out, but there are forms of divination that are older than prophecy, that of three sisters, the Fates, who were long skilled at prediction when Apollo was still learning. Thus, Hermes becomes the god of the very practice that dominates our modern use of Tarot cards, divination.

In recent years, Tarot divination has become psychologized, that is, the cards are seen as representative of psychological or emotional states. We might say, for example, that the Magician symbolizes creative energy, or the Empress strong emotions. Both these statements are true as far as they go, but divination also contains a quality of magic. The word divination itself derives from “divine,” for in ancient times people saw divination as communication with the gods. Karl Kerenyi, one of the past century’s great writers on Greek myth, described Hermes’ ability to look at the tortoise and “see through” its present state to its future possibility as the lyre. This divine, or magical, quality of seeing through is just what happens in a Tarot reading. We lay out the cards and, inspired by the images, see beyond the present situation to what is likely to develop.

There is a difference between oracular visions, under the rule of Apollo, and divination, under the rule of Hermes. The first, as practiced most famously at Delphi, depends on direct inspiration, often in a trance state. Divination uses a system, often some kind of casting of lots. In Greece, this might have meant using the letters as symbols of meaning, the way people have always used the Scandinavian runes (actually an alphabet) or the Hebrew letters. Tarot cards are a system of divination, an intermediary that we use to answer our questions and gain insight.

Though the Fates were very ancient goddesses, it is significant that they were women, and divination belongs to them. Many cultures have considered divination a woman’s occupation, sometimes done by traveling diviners. In Scandinavia, the runecasters traveled from village to village, wearing cat’s fur gloves and capes to partake of the magical psychic power of cats (compare the idea of black cats as “familiars” of witches). Today, while there is no shortage of men who read Tarot cards, the image of a Tarot reader often conjures up a “Gypsy” woman in colorful scarves. And those of us who teach Tarot workshops often comment how women participants will greatly outnumber men. The act of divination calls forth the feminine—in men as well as women. Divination involves sensitivity, psychic awareness, nurturing, and care (people who come for Tarot readings usually are suffering, or at least worried), qualities our culture considers the realm of women. And yet, while the High Priestess can symbolize, and even bring out, our psychic abilities, and the Empress our nurturing, the practice of divination belongs to the Magician.

In traditional Tarot symbolism, the Magician stands for the masculine principle—active, light, dry, rising upwards, tending toward oneness, conscious, and rational, while the High Priestess represents the feminine principle—receptive, dark, moist, sinking downwards, complex, unconscious, and intuitive. We sometimes see the masculine and feminine described as “positive” and “negative,” but this does not mean good and bad. Instead, it refers to the positive and negative poles of electromagnetism, which exist together and allow energy to flow.

The very image of the number one, whether as the Arabic numeral 1 or the Roman I, suggests the male organ, upright and potent, just as the Roman representation of two, II, suggests the entrance to the female womb, where new life grows. When ancient peoples set up stones to represent the phallus—those upright pillars for Hermes, and similar columns for the Hindu god Shiva—or created pools and temples in the shape of the womb, they were not obsessed with sex. Rather, they understood that the life-giving energies of sexuality are a mirror of divine masculine and feminine principles. As above, so below.

This is a good point at which to stress that the Magician is not just for men, and the High Priestess just for women. The Tarot uses a very old symbolic system in which images of men and women symbolize particular qualities. At the same time, esoteric teachings have always understood, even when society believed in rigid gender roles, that true fulfillment lies in integrating both male and female energy.

Throughout life, we all fluctuate between different qualities all the time. One of the benefits of Tarot readings is their ability to show us what aspects of ourselves are active at any particular time. One day the Magician might appear to remind you of your creative energy or determination or clear mind, another time the High Priestess will help you acknowledge your intuition and inner wisdom.

The Magician’s number, that I in Roman numerals, implies the conscious self, the ego (which is simply the Latin word for “I”). At the same time, magic, including the magic of divination, happens when we can allow energy to enter us and then direct it to manifestation. The ability to make ourselves a kind of opening for the magical energy of divination (or any other “magic”) is symbolized in the Magician’s posture, his wand raised to the heavens, his finger pointed to the ground. This posture often makes this card attractive to artists, healers, and other people who work with manifesting energy. Almost all creative people will say that when the work is going well, it’s as if they’re not doing it—some force, or energy, is moving through them, and they are simply the channel to bring the work into the physical world. With our modern emphasis on “intellectual property” (making creativity a branch of capitalism), we consider those statements quaint, or curious, just as we think the ancient opening of poems—“Sing in me, Muse”—is just empty words. Nor do we understand why so many spiritual texts were written anonymously or attributed to mythical authors (like Hermes Trismegistus, said to be a god). Just possibly these older peoples understood the magic of creativity more completely than us, a flow of energy symbolized in the Magician’s posture.

Try standing this way. Take a stick, or a pen, or an actual magic wand, and raise it up with one hand while the other points earthward. Notice how it opens up the chest, how you can breathe more deeply. Now close the eyes and let yourself feel energy move through you, from the formless world of spirit to the solid world of matter. The Magician in a reading symbolizes great creative and transformational possibilities.

The Magician’s body also symbolizes the great Hermetic truth “As above, so below.” The actual opening of the Emerald Tablet, literal cornerstone of the Hermetic teachings, runs like this: “That which is below is like that which is above, and that which is above is like that which is below, to accomplish the miracles of the one thing.” (trans. Christopher Bamford)

Our small lives, which so often can seem random, or meaningless, are actually an organic part of the cosmos. This is one of the great teachings of the Tarot, and ultimately one of the reasons we do readings—not just to find out information, or seek guidance or self-knowledge (all of which are important) but also to demonstrate to ourselves that the universe is not just broken pieces. Things connect.

Along with the image of Hermes, there is another way to reconcile the two strands of the juggler/magus, and that is the figure of the tribal shaman. In the Shining Tribe Magician, we see a masked figure who causes a flower to grow in the desert as he channels down life from the sacred river that flows through the heavens.

Shamans heal the sick by journeying to the spirit world, and yet they were not above sleight-of-hand trickery to impress their “clients.” The European explorers who first encountered shamans in Siberia and other places sometimes described how they would observe the shaman palm a small stone before going into the tent of healing. After chanting and other magical actions, the shaman would pretend to reach into the sick person’s body and pull out the illness—the stone hidden in his hand. To the European, this branded the shaman as a con artist. Only much later did they come to a more subtle understanding. The true healing occurs in trance, in the spirit world, but the sick person needs to see some tangible result. And so the shaman holds up the black stone to show the person that a healing has taken place.

When we refuse to see the connection between Hermes the sly trickster and Hermes the wise magus, we may end up with a dangerous split between the con artist and the philosopher. We see this sometimes in modern Tarot reading. The committed reader, sometimes with a code of ethics prominently placed on the wall, carefully avoids any trace of what is called “cold reading,” the ability to elicit information from someone without actually asking, so that it seems like amazing psychic ability. To avoid any such trickery, they may block part of the essential communication that goes on in a reading. And by refusing to dazzle the client with something that might smack of trickery, they may hinder themselves from conveying the really important part of the information.

Many years ago, when I lived in Amsterdam and was first reading professionally, a very troubled man came to see me. He told how his happy life had fallen apart a few years back when he discovered he was psychic. Now, many people imagine such an awakening as thrilling, but they also imagine themselves in control of it. Unable to stop the sensations, emotions, and even thoughts coming in from other people, this man had suffered a breakdown and had lost his job and even his family, and now kept himself under control by taking drugs meant as antipsychotics (delusions and psychic experiences may come from similar areas of the brain).

At the start of our session, he asked me, “Are you psychic?” Thinking of my ethical standards, I told him no, I just interpreted the pictures. I didn’t realize that he actually was asking, “Can I trust what you say?”

As so often happens with someone in serious need, the reading came out clear and precise. It showed the shock that had upended his once happy life, showed his frightened state, and most important, showed that he could be happy, and useful, and safe, if instead of suppressing his ability with drugs he found a teacher to train him.

As it happened, I knew such a teacher, a brilliant woman named Ioanna Salajan. She was in fact my teacher, for I went to her weekly combination class of meditation, Zen, personal growth, and psychology. It was Ioanna who said the words at the front of this book, “Nothing is learned except through joy.” I only attended the weekly class, but friends of mine went to her intensive groups, where she focused on the esoteric traditions of psychic healing.

I told my troubled client about Ioanna, gave him her contact information, and told him as well that if she could not help him, he could go to her teacher, a near-legendary figure who lived in Denmark but taught in many countries. The reading offered great promise, but it meant he would have to give up his terror, go off the medication, and cultivate the very energy that had caused such anguish. And because I had said I was not psychic, he did not dare to trust me.

Does this mean I now say yes whenever someone asks if I’m psychic? No. I will say that psychic moments occur in readings, but I work primarily from the pictures. This is true, and it avoids the expectations that I will say something like, “On May 17, you will go to a party and meet a tall, black-haired man named Greg—” in other words, the kind of Tarot reader they’ve seen in bad movies. And yet, I try to remember that some people need a little razzle-dazzle to accept the genuine magic of the reading.

The infinity sign above the Magician’s head (called a lemniscate) symbolizes the truth that life is eternal, without beginning or end, that nothing is destroyed but only changes form. “Energy is neither created nor destroyed” runs the law of conservation of energy. As a sideways number 8 it suggests “As above, so below,” but also a variation, “As without, so within.” The events in our lives reflect the inner truth of who we are. Paul Foster Case says in his book The Tarot that occult tradition assigns the number eight to Hermes (Trismegistus), the transmitter of divine teachings. Along with all these meanings, we might add that the lemniscate evokes the constant play of energy between Hermes the grand teacher and Hermes the trickster/diviner/juggler.

Karl Kerenyi says it is Hermes who puts things in our hands just when we need them. Such magical coincidence is a kind of divine trickery, and virtually everyone who commits her- or himself to a sacred or creative path will experience moments when something just happens to help them along the way. Merlin Stone (what a perfect name for a magician!), author of When God Was a Woman, told of how in the middle of her research she needed a certain book that was nowhere to be found. She tried used bookstores (this was long before the Internet), libraries, universities, all without success. One day she went to the supermarket, and as she walked through the aisles, she found an old book lying on the floor. It was, of course, the very one she needed. The Magician in a reading may signify such moments, especially if it appears with other cards that represent help or guidance.

Generally, the Magician in a reading signifies consciousness, will, and transformative or creative power. It suggests that in some way magic is present in our lives, or that we have the ability to bring about a magical change. If it comes up in a temporary position, such as “near future” in the Celtic Cross, we need to take advantage of this burst of energy, this flow of excitement. In a more long-lasting position, such as “outcome” in the Cross, it indicates a shift in life to greater power and creativity. It is a very auspicious card for an artist or writer or performer, for it symbolizes creativity itself.

As card one, it can indicate the beginning of something, and a very positive beginning, in particular the first actual steps to make it real, and the will to carry it through. The will of the Magician is unified and directed. The card also can indicate the ego and a desire to dominate, in particular with other strong-minded cards.

The reversed Magician may suggest an abuse of that strong will, even in some rare cases, so-called “black magic,” used for destructive, selfish purposes. Remember that the Magician heads the triad that includes Strength but also the Devil. Conversely, the upside-down card can mean a weakening of the will, or lack of focus, or self-doubt.

The will or creative energy may be blocked or disrupted. This can result in weakness or confusion of purpose. It can lead further to apathy, lethargy, an inability to act. For artists it can mean a creative block. Sometimes the blocked energy can cause anxiety, or fear, or panic attacks.

Because the source of these situations is the reversed Magician, the problem may come from something the person needs to do, some decision or action the person is avoiding. It may involve taking a risk (especially when the Fool also appears) or going against family or social opinion (especially when the Hanged Man appears). Think of the Magician’s posture as a lightning rod. If he allows the energy to pass through him and be grounded in action, or a decision, he experiences that magical joy. If he resists doing that, the energy stays inside, disrupting the system. If the Magician reversed comes up in a reading, ask yourself, “Do I doubt myself too much? Is there something I know I need to do? How can I serve the muse and the world?”

Here are two readings to understand magical power. The first is a Wisdom Reading to understand what magic means.

A Magician Wisdom Reading

1. What is magic?

2. How does it act in the world?

3. How do we find it?

4. How do we use it?

5. How do we become magicians?

Lay out the cards in whatever pattern feels right to you.

The second reading is a personal reading to look at the same issues for yourself.

A Magician Personal Reading

1. What is magic for me?

2. How does magic act in my life?

3. Where do I look for magic?

4. How do I find it?

5. How do I use it?

6. How can I become a magician?

7. What will it mean to me?