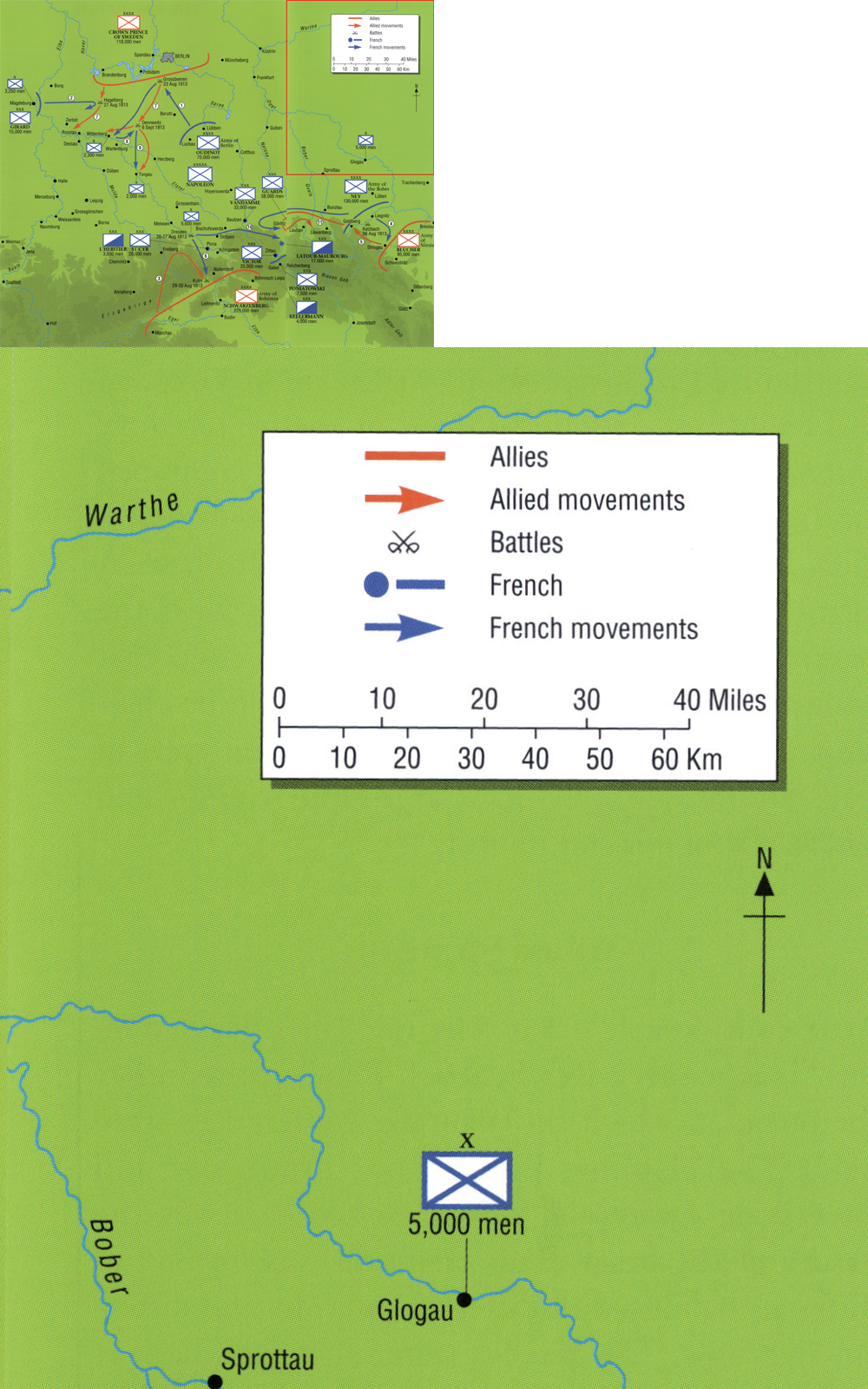

Napoleon’s position in August 1813 was as follows: his troops held three fortresses in the Vistula theatre, namely Danzig (Gdansk), Modlin and Zamosc. Along the River Oder he held Stettin (Szczecin), Küstrin (Kostrzyn) and Glogau (Glogow). Along the River Elbe he held Torgau, Wittenberg and Magdeburg. The bulk of his forces were concentrated east of the Elbe in Saxony and Silesia with Dresden forming his base of operations, his main magazine and bridge-head. The right flank of his position was secured at a distance by the Bavarian corps on the Inn and Prince Eugène de Beauharnais’ army on the Isonzo. Davout’s corps in Hamburg secured his left flank.

Table 8. Summary of the forces involved in the Leipzig Campaign

| French | Commander |

| Army of Berlin | Marshal Oudinot, later replaced by Marshal Ney |

| Army of the Bober | Marshal Macdonald |

| Allied | Commander |

| Army of Bohemia | Schwarzenberg (Austrian) |

| Army of the North | Crown Prince of Sweden (Swedish) |

| Army of Silesia | Blücher (Prussian) |

His Intelligence of Allied dispositions was as follows: in Brandenburg there was a Russo-Prusso-Swedish force under his former marshal Bernadotte, now the Crown Prince of Sweden; in Silesia he was opposed by a Prusso-Russian army and in Bohemia by the Austrians.

Strategically on the defensive and outnumbered, Napoleon needed to go on the offensive tactically to gain the military victories needed to restore his fortunes. For this, he enjoyed the benefit of a central position and central command. Using these he would be able to screen off two of the enemy armies with light forces and concentrate his efforts on destroying the remaining one. With one army destroyed, the coalition facing him would have the choice of either continuing the war against a stronger enemy or suing for peace. A defeat would lead to the coalition squabbling among themselves and breaking up. In any case, having defeated one army, Napoleon would be in a position to pick off the others at will. This strategy depended on Napoleon’s subordinate commanders possessing sufficient skill and initiative to act independently of their master and for his staff system to be sufficiently developed to allow him to co-ordinate their actions. The fact is that neither of these prerequisites were fulfilled. For all its imperial trappings, the Bonaparte regime was basically a dictatorship established by a coup d’état after a bloody revolution and sustained by military conquest. Napoleon could brook no competition for domestic political power. His regime had come close to being toppled after the previous year’s military fiasco. He had to ensure that the military success was his and his alone. He therefore chose subordinates who were loyal but lacked the stature to achieve anything of significance without his close personal supervision. His best marshal, Davout, whose dramatic success at Auerstedt in 1806 showed where real military genius lay, was placed in a secondary theatre, in Hamburg on the lower Elbe. Napoleon had no real general staff, at least as we understand it today and as was being developed in Prussia at that very time, but rather a series of clerks who wrote down his orders and passed them on. Initiative by his subordinates was frowned upon by the man who feared for his political survival, but it was that very attribute that would be required to win this campaign.

The question that faced Napoleon was, which of the three Allied armies should he attack? Let us consider what he had to gain and lose by his choice.

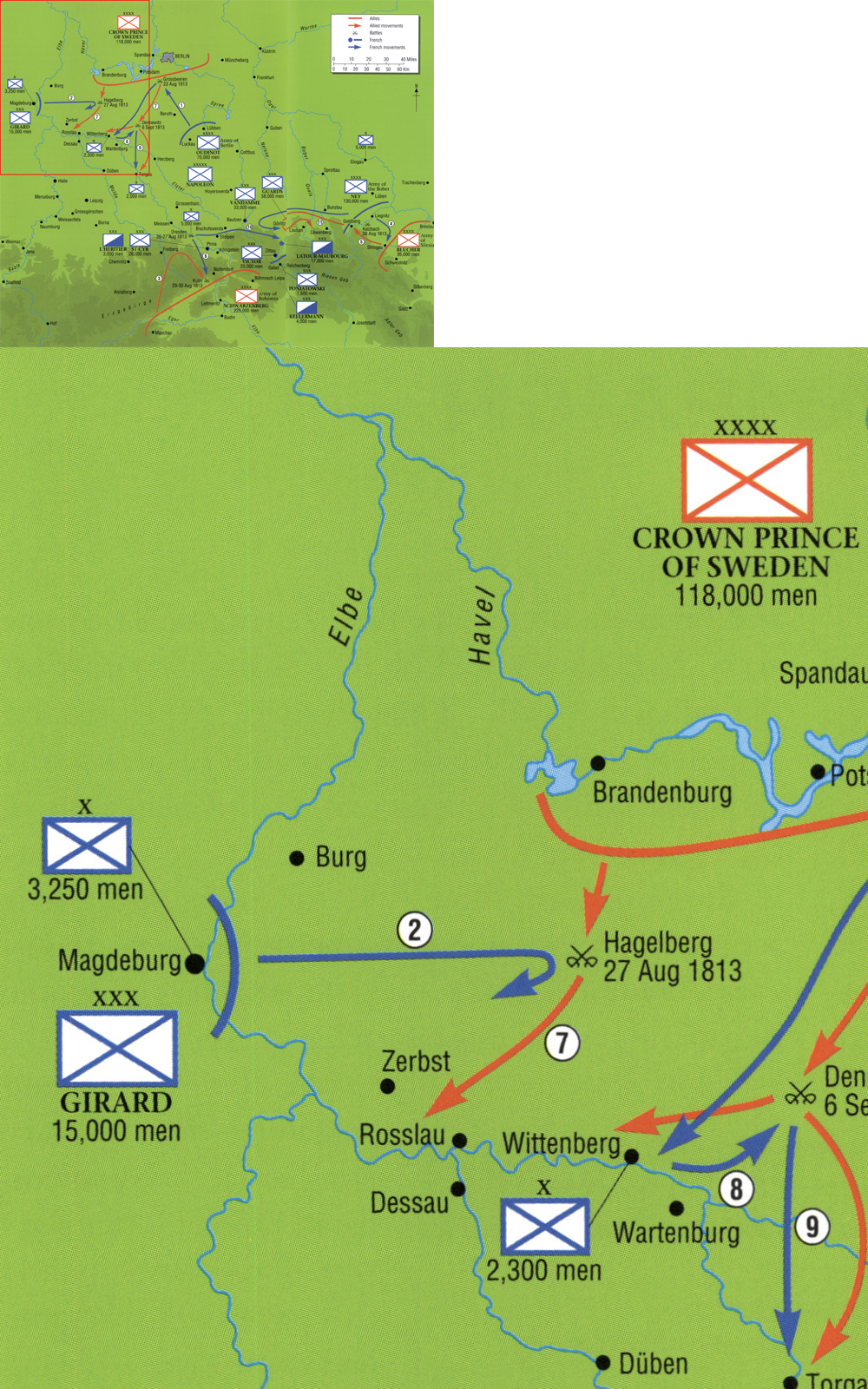

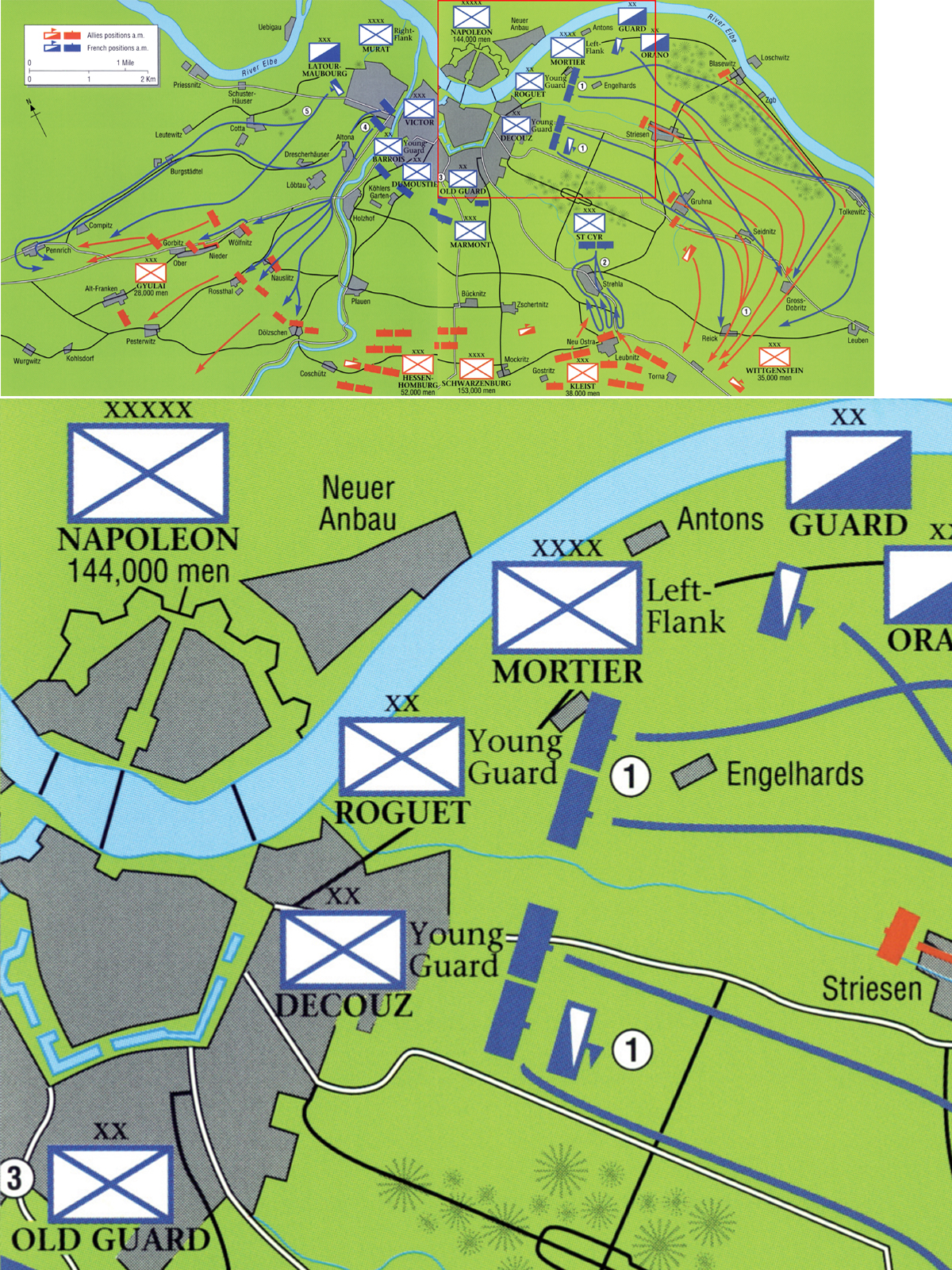

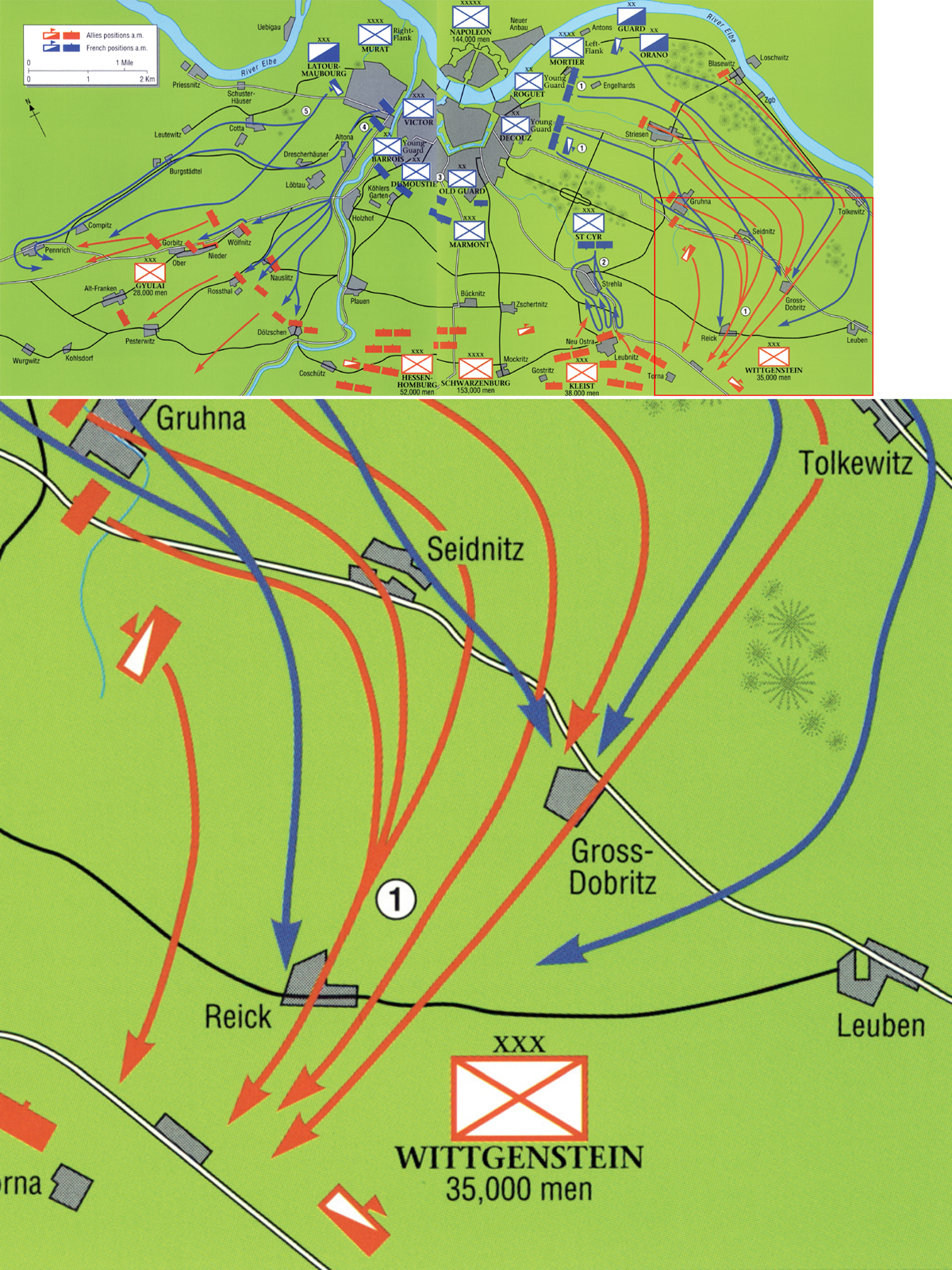

Leipzig 1813: Starting Positions mid-August 1813 & Movements

1. Advance towards Berlin by Oudinot’s Army of Berlin to 23 August. Defeated by Army of North at Grossbeeren 23 August.

2. Girard’s advance in support of Oudinot. Defeated by Hirschfeld’s Division of Prussian militia at Hagelberg on 27 August.

3. Army of Bohemia under Schwarzenberg advances towards Napoleon’s base at Dresden to 26 August.

4. With Napoleon at its head, the Army of the Bober advances on Blücher. Blücher retires but Napoleon rushes back to Dresden to deal with Schwarzenberg. Wins Battle of Dresden, 26/7 August.

5. Army of Bober under Macdonald takes up defensive position on Bober. Blücher attacks and defeats him on the Katzbach, 26 August.

6. Vandamme pursues defeated Army of Bohemia. Is surrounded and wiped out at Kulm, 29/30 August.

7. Oudinot, beaten at Grossbeeren, falls back. Army of the North follows up.

8. Ney, given command of the Army of Berlin, advances, is defeated by the Prussian Bülow at Dennewitz on 6 September.

9. Ney withdraws. Army of North follows up.

10. Napoleon advances to engage Blücher.

11. Blücher withdraws to avoid him.

First, the Army of the North, concentrated in the province of Brandenburg, in and around Berlin. To attack this army he needed to seal the Bohemian passes to prevent the Army of Bohemia from entering Saxony and threatening his rear. This could be done with relatively few troops, particularly as Schwarzenberg was not likely to act aggressively. The Army of Silesia would have to be held off with a substantial force because Blücher was likely to be aggressive. A former marshal of his, Napoleon knew his characteristics well. The Crown Prince of Sweden was unlikely to want to get involved in a serious confrontation with his former master, but the Prussian corps under his command was not likely to give up its capital Berlin without a fight and it could count on the support of the Russians. Napoleon’s line of communications for such an offensive was covered by the fortresses on the Elbe which were in his hands, and his flank could count on support from Davout’s corps on the lower Elbe. Once a divided Army of the North was defeated before Berlin, Napoleon could then move on the flank and rear of the Army of Silesia which would be moving on Dresden. This army could be pushed back into the mountains of the Bohemian border and defeated in detail. The Austrians would then gracefully accept the situation and Napoleon would be restored to his coveted position as master of Europe. But what if the Prussians were to accept the necessity of abandoning Berlin in favour of linking up with the Army of Silesia in the East? With supplies and reinforcements coming from Russia, the combined Armies of the North and Silesia would be too strong for Napoleon to defeat.

Secondly, the Army of Silesia, under the Prussian Blücher. He was a wily old bird who was not going to be an easy catch. As he had shown in his retreat to Lübeck in 1806, he would not give up easily. Even the bloody nose he had got that spring at Lützen had not stopped him turning for another fight only days later. An offensive against this army was likely to be a protracted affair leading ever deeper into enemy territory, towards Russian reinforcements and putting Napoleon’s forces into ever greater danger from flanking moves by the Armies of the North and Bohemia who, slow as their reactions were likely to be, would be in a position to cut Napoleon off from his communications and his base in Dresden. This course of action was unlikely to be fruitful.

Finally, the Army of Bohemia under the Austrian Schwarzenberg. This was the main Allied army and the infliction of a major defeat on this would be likely to cause the coalition to fall apart. Napoleon could either attempt to draw it out into Saxony and crush it there or himself move through the Bohemian passes and deal a blow there. He would need to deploy a substantial force to hold off Blücher from his base at Dresden while the Army of the North would merely have to be observed. Napoleon could then link up with his forces in southern Germany and realign his lines of communications through safer channels while still holding northern Germany through his fortress garrisons. Even if Blücher moved through the passes of Silesia to link up with Schwarzenberg, it was unlikely that he could arrive in time to influence the outcome. However, this would mean giving up the precious supplies in Saxony, his important base in Dresden and it would take too long to establish the new lines. Whatever he did, he needed to be sure that the Army of Bohemia did not slip away into southern Germany and threaten his communications with France. He had to tie it down somehow.

Napoleon was on the horns of a dilemma. He was too tied to his precious magazine at Dresden and could not operate so deep in enemy territory without it. He was too weak to defeat the combined forces of the Allied armies, yet to be able to defeat them in detail he would need to abandon his base. A negotiated peace might well leave him with the crown of France but how long could he hold that against his domestic opposition who would be challenging the cost and end result of all those years of war? He needed a brilliant and rapid victory and had to rely on his star to bring it.

After considerable discussion, the Allies decided on the ‘Trachenberg-Reichenbach Plan’, named after the towns in which the planning conferences were held. The planning process was drawn-out and altered on numerous occasions but this was the nature of the beast. This coalition was formed of different nations with differing interests and different war aims. The Swedes were there for whatever pickings they could get at minimal cost. The Russians, although wanting the overthrow of Napoleon, had already liberated their motherland and would have settled for a reasonable peace. The Prussians were fighting for their very existence and needed a rapid and decisive victory. The Austrians did not make up their minds whose side to fight on until the last minute and were as much worried by the Russian threat as the French. Without a single command and a single aim, the Allies were not likely to act decisively unless events left them with no choice. Their plan reflected this fact. They did not set their amalgamated forces the prime task of totally destroying the enemy, but set themselves a series of limited objectives and principles, the adherence to which included the following:

1. Any fortresses occupied by the enemy were not to be besieged but merely observed.

2. The main effort was to be directed against the enemy’s flanks and lines of operation.

3. To cut the enemy’s communications, forcing him to detach troops to clear them or move his main forces against them.

4. To accept battle only against part of the enemy’s forces and only if that part were outnumbered, but to avoid battle against his combined forces especially if these were directed against the Allies’ weak points.

5. In the event of the enemy moving in force against one of the Allied armies, this was to retire while the others would advance with vigour.

6. The point of union of the Allied armies was to be the enemy’s headquarters.

Napoleon’s opening offensive was against the Army of Silesia. Over-estimating the size of the forces available to Blücher and knowing his aggressive nature, he perceived the greatest threat to be from this quarter.

He placed himself at the head of the Army of the Bober. To deal with the Army of the North, he formed the Army of Berlin from IV, VII, XII Corps and III Cavalry Corps, a total of 63,600 men and 216 cannon. He appointed Marshal Oudinot its commander. In support was Girard’s Corps and Davout in Hamburg. Estimating that whatever course of action it chose, it would take the Army of Bohemia roughly five days to manoeuvre to a threatening position, he remained on the defensive on that front. He instructed II and VIII Corps, IV Cavalry Corps and various other smaller formations to take up covering positions.

Blücher responded to the French offensive in the manner prescribed by the Allies’ strategic plan; he withdrew, leaving Napoleon striking out against air. Meanwhile Oudinot advanced on Berlin and the Army of Bohemia moved to threaten the French magazine at Dresden. Napoleon rushed back to Dresden to conduct its defence personally and appointed Macdonald commander of the Army of the Bober. It looked very much as if the campaign were approaching its climax and that Napoleon had victory within his grasp. Indeed, he won a resounding victory over the Army of Bohemia in two days’ fighting in and around Dresden, but his subordinates proved unable to conduct independent command and snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

Although there had been several skirmishes to date, Grossbeeren was the first major action of the campaign. Oudinot, commander of the French Army of Berlin, was ordered to push the enemy back quickly, take Berlin, disarm its inhabitants and disperse the militia. If Berlin resisted it was to be destroyed. He was to advance with the support of Girard’s Corps with Davout moving from Hamburg towards Berlin. Oudinot’s army consisted of three corps, Oudinot, Bertrand and Reynier, together with Arrighi’s Cavalry Corps; a total of about 70,000 men including 9,000 cavalry and 216 guns. Napoleon had underestimated not only the size of the Army of the North but also its quality. Oudinot’s force was simply not strong enough to accomplish the task in hand. The quality and reliability of the Army of Berlin was questionable. The infantry consisted in bulk of Italians and Germans and the training of the cavalry was woefully inadequate. Girard’s Corps was in better condition, with one division of reliable Poles, but the other of raw recruits. This force advanced towards Berlin and the Army of the North which was stronger not only in numbers (c.98,000 men) but also in morale, being composed in part of Brandenburgers – defending their very homes.

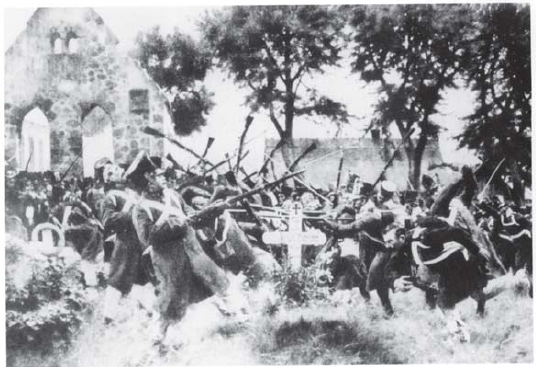

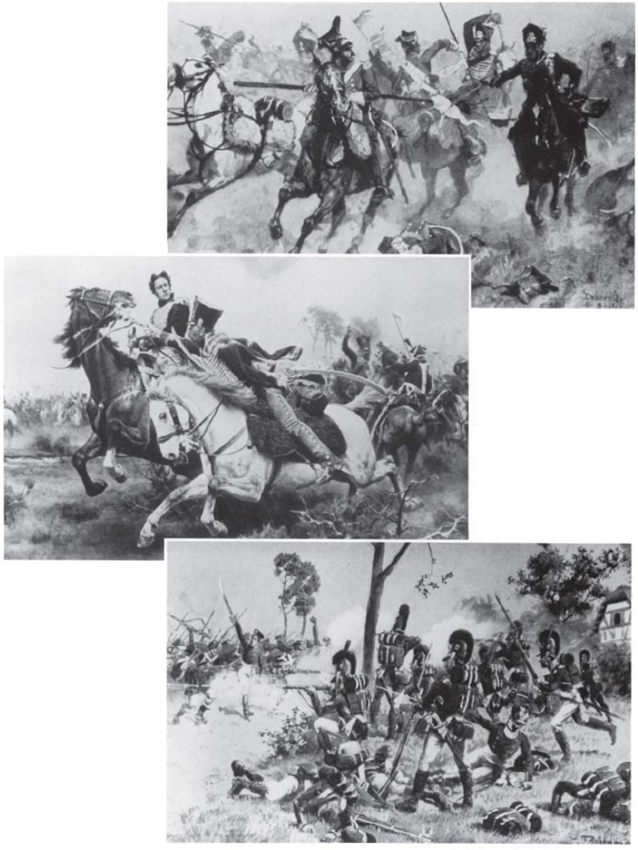

Grossbeeren. Heavy rain made it difficult to fire muskets. The issue was often decided by the butt and bayonet; even so, this late 19th century painting by Röchling exaggerates a little and is typical of the romantic views held later in the 19th century. Nevertheless, Röchling’s painting of the fight for the churchyard shows the uniforms and equipment of the time – virtually all the infantry wore covered shakos and greatcoats, leaving little to distinguish friend from foe, in this case, Saxons and Prussians.

Russian Guard Infantry: (1) NCO Life Guard Regiment Preobrashenski, summer sentry uniform; (2) Grenadier, Life Guard Regiment Semjonowski, winter sentry uniform; (3) Regimental Drum Major, Life Guard Regiment Ismailowski, winter walking out dress; (4) Jäger of 1st Battalion, Life Guard Regiment Jägerski, winter service dress; (5) Collar of NCO, Semjonowski; (6) Collar, Preobrashenski; (7) Cuff patch, Pawlowksi; (8) Cuff patch, Finlandski; (9) Shako badge, Guard; (10) Cartridge box, Guard.

The ‘Legend of Phillipsthal’, invented by certain German historians, has it that the Crown Prince of Sweden wanted to pull back in the face of Oudinot’s advance and leave Berlin to the mercy of the enemy but was forced to stand and fight by the Prussian Bülow. However, documented fact (a message from the Crown Prince to Blücher dated 2.30 a.m. 22 August) states: ‘My outposts were attacked yesterday by the troops of the Duke of Reggio (Oudinot). His army is about 80,000 men strong … I am marching to give battle.’ The Crown Prince of Sweden has always suffered from a bad press and this false legend is but one instance.

Oudinot was handicapped by faulty Intelligence, his cavalry being insufficiently skilled to gather correct information as to the enemy’s strength and dispositions. On 22 August, he sent a message to Napoleon stating that he expected to enter Berlin without serious resistance on the 24th. His army was not deployed for battle but advanced in three march columns in the direction of Berlin. At Blankenfelde Bertrand’s Corps on the right blundered into Dobschütz’s Division of Prussian militia, at 9 o’clock on the morning of 23 August. Dobschütz had about 13,000 men and 32 guns. Bertrand had about 20,000 men and 66 guns but was unable to deploy all of these. The Prussians threw out their vanguard into the woods to the south of Blankenfelde and after several hours’ combat in these woods, managed to throw back the French. At about 2 p.m. the French withdrew. Both sides lost about 200 men each.

At roughly the same time, Reynier’s Corps reached Grossbeeren with Sahr’s Division of Saxons to the fore. After a short artillery duel, the four Prussian guns limbered up and withdrew. The Saxons then stormed the burning village and ejected the three battalions defending it. Believing the battle to be over, Reynier started to pitch camp. Hardly had his rear divisions moved up when the real battle started with Bülow’s artillery firing into the camp. Bülow’s troops had been marching in the pouring rain since 7 a.m. and were exhausted. They wanted to pitch camp for the day at Heinersdorf when the report on Grossbeeren arrived. A reconnaissance of the area revealed that Reynier was still moving through the woods and that an attack on him would more than likely be successful. The Prussians went over to the offensive.

Screened from observation by the heavy rain, the Prussians advanced with the Divisions Hessen-Homburg and Krafft in the front line with Thümen and the cavalry and artillery reserves in the second. As speed was of the essence and the rain prevented a detailed reconnaissance, the Prussians plunged forward when a flanking move would have been less costly. This stage of the battle was opened by an artillery duel lasting 1½ hours. As the Prussians brought up guns from their reserves, they enjoyed the advantage of numbers. Bülow’s infantry was formed up 300 paces to the rear of the artillery. Borstell’s Division pressed forward and moved on Grossbeeren from the east. As the fire of the French artillery weakened, the Prussians went over to the offensive. The enemy was driven back and broke once the windmill was threatened by Krafft from the rear. The Saxon Regiment Low formed the rearguard and was involved in close combat with the advancing Prussians. The bayonet and butt were used, the weather making firing difficult. Reynier brought up Divisions Durette and Lecoq to recover the situation. Durette’s troops were panicked by the retreating Saxons and broke without coming into action. Lecoq fared little better.

Bülow had started to pitch camp in the darkening evening when it was his turn to be surprised. The third French column had marched towards the sound of the guns in Grossbeeren and arrived at Neubeeren at about 8 p.m. Here, the French vanguard met the Prussian Life Hussars and a confused cavalry battle took place in the dark. The French eventually withdrew, leaving about 100 prisoners behind. Because of the bad weather and their exhaustion, the Prussians were unable to launch a pursuit.

Next day the French continued their retreat. Total losses were about 3,000 men, thirteen guns and 60 ammunition wagons on the French side and about 1,000 Prussians. In terms of physical losses this was a relatively minor affair, but news of this defeat and the others that were to come in the following days had a demoralizing effect on the French. The Prussians were uplifted by the fact that unaided they had won their first victory since the dark days of 1806.

The Battle of Dresden was to be Napoleon’s one great victory of the entire campaign. On hearing the news that the Emperor was with the Army of the Bober, marching against Blücher into Silesia, the Army of Bohemia advanced through the Bohemian passes towards Dresden. On the right flank, Wittgenstein advanced along the Elbe leaving behind Duke Eugene of Württemberg to watch the fortress of Königstein; next to him, between Leubnitz and Maxen were Kleist’s Prussians; the Austrians under Colloredo and Chastler were advancing in two columns between Räcknitz and Plauen; Kleinau was in Freiberg; the Russian Guards and the reserves were between Kulm and Dippoldiswalde. On 25 August the Allies had 80,000 men at the gates of Dresden. St.Cyr had 20,000 men with which to oppose them. A bold move by the Allies and Dresden would have been taken. Instead, a council of war was held. One should not be too critical of the apparent sloth of the Army of Bohemia. Its command structure was decidedly cumbersome because the three Allied monarchs, Emperor Francis of Austria, Tsar Alexander of Russia and King Frederick William III of Prussia had burdened Headquarters with their presence. Added to that was the Austrian policy of wanting to come out of this campaign with a draw in their favour. Poor Schwarzenberg was compelled to fight the battle with at least one hand tied behind his back.

Decisions were made in committee. Schwarzenberg’s orders for the coming battle reflected the lack of decision and leadership at Allied Headquarters. There is no mention of an attack on Dresden, but rather talk of a demonstration against the French positions. The five columns which were to mount this demonstration did so without co-ordination and without the necessary equipment to cross the ditches and climb the walls that formed the French defensive line.

On 22 August Napoleon had been warned by St.Cyr that the Allies were advancing towards his main base in Germany so he left the Army of the Bober with Macdonald and returned with his Guards to Dresden. Not having been given the opportunity of achieving a decisive battle with Blücher, the Emperor looked forward to making up for this in Saxony. He moved towards Dresden on the evening of the 25th after receiving reports that the fall of the town and its precious magazine were imminent. He entered it at 9 o’clock the next morning with a total of about 90,000 men. If the Allies had known of his proximity they would not have given battle.

The town of Dresden was fortified to a certain extent. The suburbs had been prepared for defence by loopholing walls and putting firing platforms behind them, palisading the holes and linking up the paths. Moreover, there were five lunettes which protected the exits from the town. This defensive line was eight kilometres long and St. Cyr simply did not have the men to defend it; at the critical points he had one man per ten paces of front; and this fact could not have escaped the Allies as Wittgenstein had been facing it for two days. Given good leadership and preparation, the Allies would have had every chance of success.

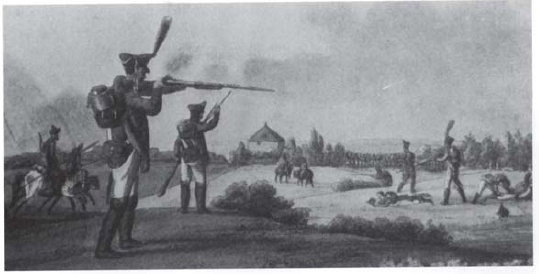

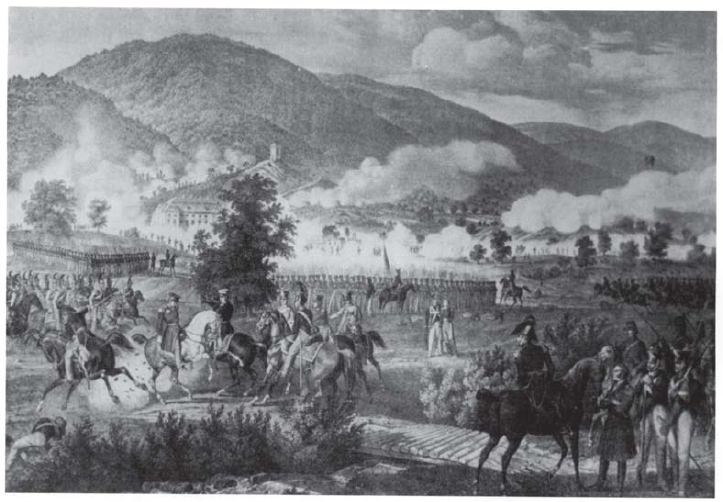

The Battle of Dresden opens. This contemporary print gives a good indication of skirmish tactics of the period. The Russian infantry to the fore are skirmishing in pairs, one loading while the other gives covering fire. This line is supported by Cossacks. The French skirmishers, also operating in pairs, are clearly supported by a line of formed troops to their rear.

Austrian Jäger storming a fortification in the Moschinsky Gardens in Dresden on 26 August. The lack of scaling ladders which severely handicapped the Allied assault is very apparent in this coloured lithograph.

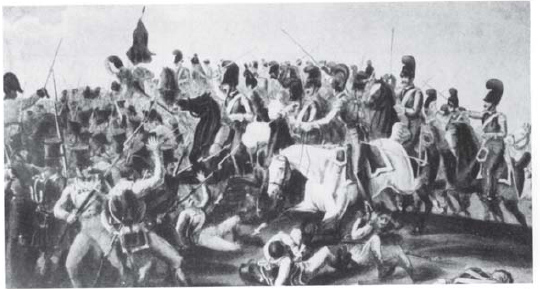

The charge of the Saxon Cuirassier Regiment Jung-Zastrow on Austrian infantry at Dresden on 27 August.

At 5 a.m. on 26 August Kleist’s column of Prussians began the attack and pushed through most of the Royal Gardens despite heavy resistance. Wittgenstein, on his right, found the going tougher. Flanking fire from across the Elbe and from the lunettes to his fore made his gains untenable and forced him back to his starting positions. The Austrians also pushed forward, gaining ground on the left flank, but withering fire from lunettes III and IV prevented headway in the centre. By midday, most of the Allied front line was within cannon shot of Dresden. It was apparent to them, however that, as the French resistance was so strong, St.Cyr was being reinforced. Cries of Vive l’Empéreur! coming from enemy lines indicated that Napoleon himself was present and there was a general feeling at Allied Headquarters that a withdrawal was now due. Only Frederick William of Prussia spoke against this, asking why with 200,000 men the Allies should run away from the name ‘Napoleon’? The attack continued at 4 p.m. Wittgenstein pushed forward and took the three farms of Antons, Lämmchens and Engelhards. All attempts to take the farm of Hopfgartens were broken up by the murderous artillery fire from across the Elbe. Wittgenstein formed up his last reserve at 5 p.m.

Dresden, Day 2, 27 August 1813: The Emperor’s only Victory

1. Napoleon launches his counter-attack. Two divisions of Young Guard commence their assault on Russians shortly after 6 a.m., pushing them back to Reick by 11a.m.

2. St. Cyr assaults Strehla, taking it by 8 a.m. At noon, Prussians launch counter-attack which is beaten off.

3. French centre holds it position and engages Allies with its artillery.

4. At 2 p.m., Victor launches his attack, driving back Aloys Liechtenstein’s Austrians.

5. Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry pursue beaten Austrians.

By 2 p.m. the Prussians had taken the Royal Garden and by 5 p.m. had forced their way forward to the edge of town. They were likely to break in at any time. The Austrians too had pushed forward, a grand battery of 72 pieces supporting their advance in the centre. Along the whole front, the Allies were on the verge of storming the town of Dresden itself. It was at this point that Napoleon ordered his 70,000 reinforcements on to the offensive.

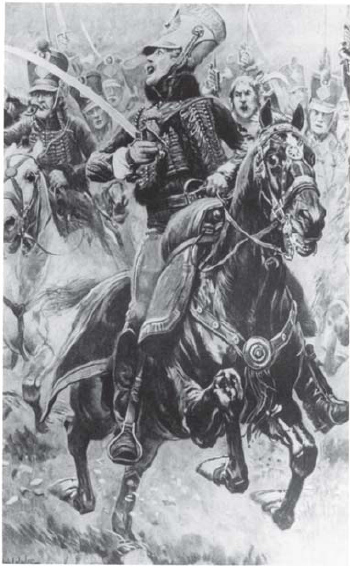

A rather romantic portrayal of French hussars at Dresden but nevertheless one of interest. Note the officer to the fore commanding his bugler to sound the charge.

Painting by A. Lalauze.

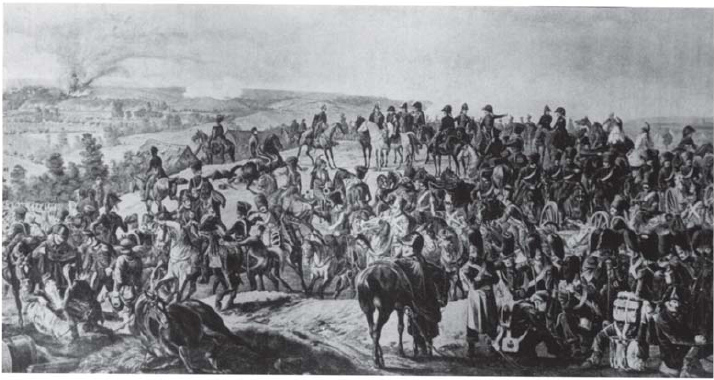

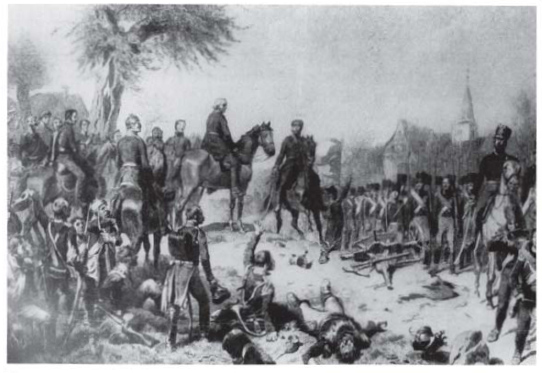

Napoleon on the Strehlen Heights during the Battle of Dresden, 27 August. A clear illustration of how Napoleon commanded on the field of battle. Selecting a good vantage point, his generals would visit him for instructions while his aides waited to receive messages for forwarding. To the right of this painting by Friedrich Schneider, his Old Guard rest in the presence of their Emperor.

Wittgenstein was driven back step by step. By 8 p.m. the French had reached Striesen and after four hours of bitter fighting, finally drove out the Russians. The French advance stopped here once Klüx’s Prussians arrived.

The French Guard stormed the Royal Garden and after two hours ejected the Prussians. Led by Ney, Divisions Barrois and Dumoustier fell upon the Austrians in the centre, forcing them back. Here the fighting continued until midnight. On the left, the Austrians fared little better, being outnumbered by Murat’s troops. To the rear of the Allied position, Vandamme’s Corps crossed the Elbe at Königstein. Württemberg fought a determined holding action, delaying the French advance despite their superior numbers. Early next day, 27 August, Headquarters of the Army of Bohemia reacted to his messages and sent him reinforcements.

During the night, the Allies had the opportunity to reflect upon their current position and consider their course of action. Their failure to capture Dresden was due in part to a lack of clear leadership. Over a front of eight kilometres it had proved impossible to co-ordinate their attacks. They had no equipment for crossing ditches and climbing walls. The French had the advantage of a prepared position, central command, fresh troops constantly arriving, and did not need to spend yet another night in the rain and mud. It was clear that the French would continue their offensive the next day. The Allied troops were demoralized and lacked confidence in their leadership. Also, Vandamme was threatening their rear. Even though it outnumbered the French forces, the Army of Bohemia had little chance of success and the prudent course of action would have been to fall back. The course of action chosen was to renew the attack on 27 August.

Napoleon’s plan of action for the next day was to attack the enemy’s flanks thereby denying him the best lines of retreat, forcing him instead to fall back over difficult country lanes. Reinforced during the course of the night by Victor and Marmont, his troops had spent this wet night under cover. In the presence of their Emperor, morale was high. Napoleon’s troops were deployed as follows.

Right flank: 39,000 men under Murat with Victor’s Corps and Teste’s Division in front of the Lobtauer Schlag (exit), Latour-Maubourg’s Cavalry Corps and Pajol’s Cavalry Division in front of the Priessnitzer Schlag.

Centre: 80,000 men. St.Cyr’s Corps south of the Royal Garden, Marmont in front of the See-Vorstadt, Divisions Dumoustier and Barrois of the Young Guard in front of the Falken and Freiberger exits, Old Guard between lunettes III and IV, Guard Cavalry Division between the Streisen ditch and the Royal Garden.

Left flank: 25,000 men under Mortier. Divisions Decouz and Rouget of the Young Guard between the Elbe and the Pirna road, Cavalry Divisions Lefebvre and Ornano between the Landgraben and the Elbe.

From midnight it rained heavily. The ground turned to mud, making movement away from the roads difficult. Shortly after 6 a.m. two divisions of the Young Guard launched an attack in the area between the Elbe and the Royal Garden. Roguet’s Division, having no opposition, pressed forward, outflanked the Russians and had pushed them back to Reick by 11 a.m. By 8 a.m. St.Cyr had forced the Prussians to evacuate Strehla. From 10 o’clock his artillery bombarded Zschernitz and Leubnitz. In the centre Marmont’s Corps and two divisions of the Young Guard made little progress and this sector of the front went over to an artillery duel. On the right flank Victor’s Corps gained ground. At midday the Prussians staged a counter-attack on St.Cyr, but this was beaten off. The situation at 1 o’clock was decidedly in favour of the French. Their right flank under Murat was close to achieving victory, the centre was holding well and the left flank, having made gains earlier, was getting bogged down.

The Allies decided on a counter-attack against the French left flank, but events prevented this plan being carried out. The Russian General Barclay de Tolly hesitated to carry out his orders as he was unsure of getting his artillery out of the mud in the event of an unsuccessful attack. Just when he was about to express his concern, General Moreau (at one time a rival to Bonaparte in the struggle for power in Revolutionary France, and currently in the company of the Tsar) was fatally wounded at the side of his patron which distracted the attention of those present at Allied Headquarters. Then came the news that Vandamme had taken Pirna, endangering the rear of the Allies. The opportunity for a counter blow was thus lost.

At 2 o’clock Victor moved forward again, driving back the Austrians from Aloys Liechtenstein’s Division and ejecting them from Ober-Gorbitz. Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry charged these retreating Austrians, cutting down some of them and taking the remainder prisoner. This charge split the Allied position on this flank into two. The Austrians were caught in the open, stuck in the mud, unable to fire their muskets because of the rain and surrounded by French cavalry; 9,000 of them surrendered. By 3 p.m. the Allied left flank was totally beaten, but the situation in the centre was stable and the French were making no progress in their attempts to take Leubnitz. Mortier, on the French left, was finding it even more difficult to make progress and some of his battalions had taken a mauling at the hands of Prussian cavalry.

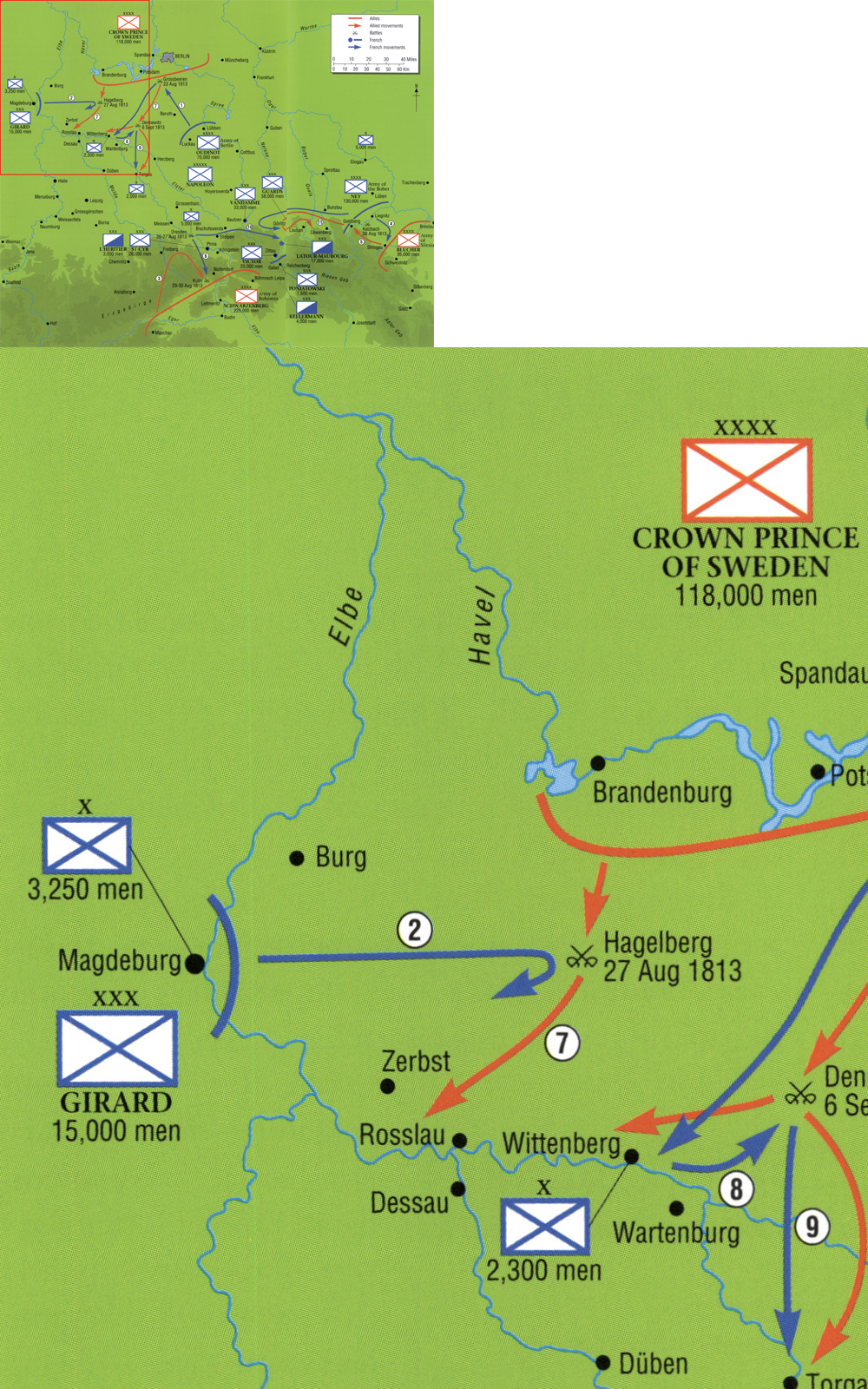

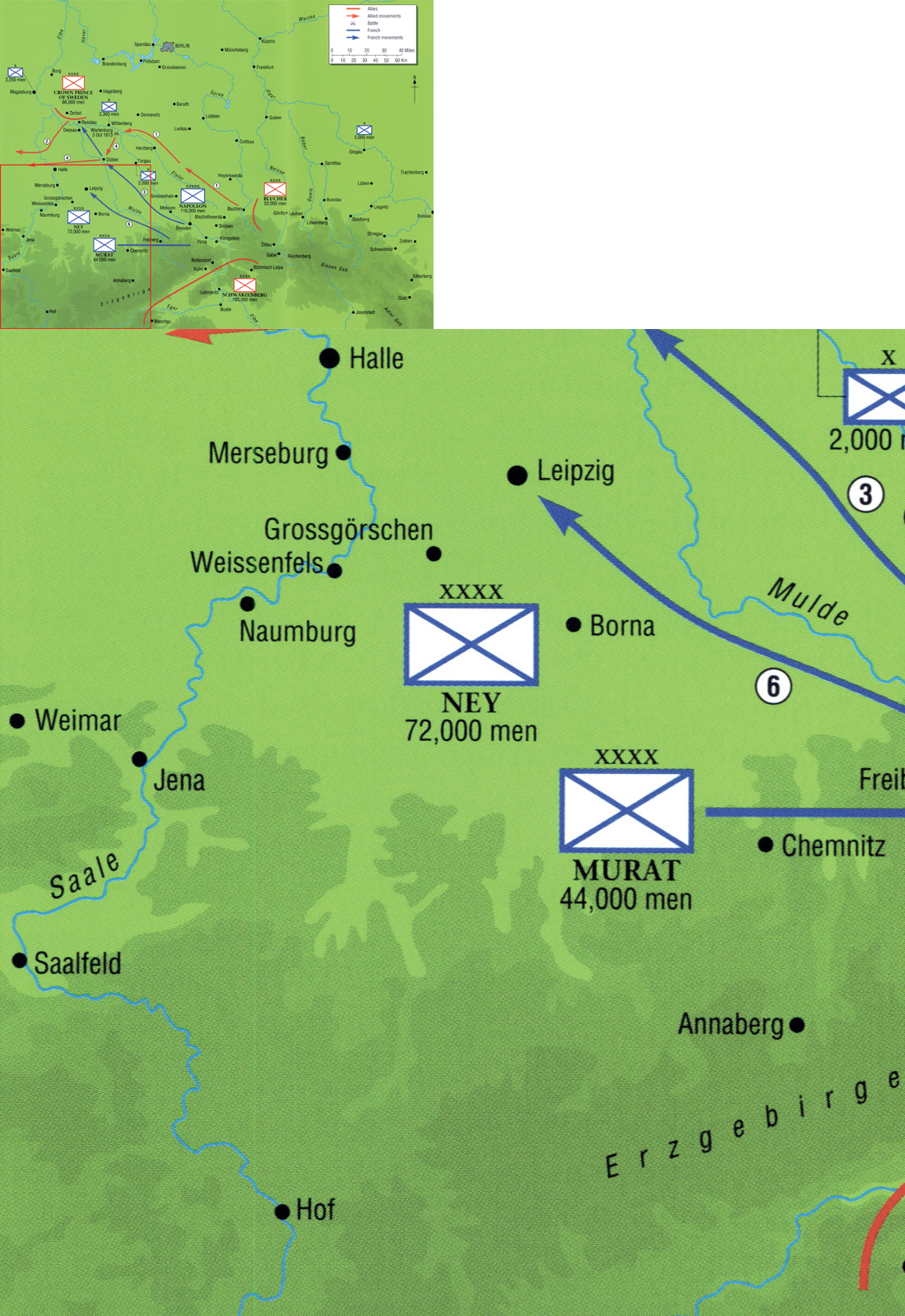

Leipzig 1813: Movements to 11 October

1. At end of September, Blücher moves to join forces with the Army of the North, crossing Elbe on 3 October at Wartenburg.

2. Army of North crosses Elbe on 4 October. Two Allied armies are now in a position to unite and force Napoleon to fight a decisive battle.

3. Napoleon abandons Dresden and moves to challenge Blücher and the Crown Prince of Sweden.

4. Blücher side-steps Napoleon and avoids battle.

5. Army of Bohemia advances again in face of weak opposition.

6. Murat falls back.

The French had achieved a local victory on their left. To achieve a total victory Vandamme’s Corps would have to come into play in the Allied rear, but the corps was held up. At Allied Headquarters it was now clear that the wisest course of action would be to withdraw and at 4 o’clock they did so, intending not merely to move away from Dresden but of retreating back into the safety of Bohemia.

The victor of Dresden reviewed the situation. He had taken 12,000 prisoners including the Austrian Field Marshal Lieutenant Meszko, two generals, 64 senior officers, several hundred junior officers, fifteen Colours, 26 guns and 30 ammunition wagons. Only the poor weather had prevented a greater catastrophe from befalling the Allies. Moreover, Vandamme, having crossed the Elbe at Pirna, was in a position to pursue and turn Napoleon’s victory into a rout. Here we return to the Army of the Bober under Macdonald, facing Blücher’s Army of Silesia.

When Napoleon left Macdonald with the Army of the Bober and rushed to Dresden, he left him with three infantry corps (III -Souham; V – Lauriston; XI Gérard) and one cavalry corps (II – Sebastiani) and orders to cover the Emperor’s rear by throwing the enemy back across the River Bober (Bobra) and then to take up a defensive posture. Macdonald’s army was a pretty mixed lot, his infantry consisting of French, Italian and German conscripts and his cavalry of young, inexperienced troopers who were no match for the cavalry of the Army of Silesia.

General von Yorck. Commander of I (Prussian) Corps. Described as being an awkward subordinate but a tough opponent who could be counted on to get stuck in when the going was tough. His corps was known as Blücher’s ‘Fighting Corps’ and played a significant role in battles such as the Katzbach and Wartenburg before being virtually destroyed at Möckern. The remnant marched to the Rhine, crossing in mid-winter at Kaub before continuing on to Paris.

Blücher’s forces consisted of the Russian Corps of St. Priest, Langeron and Sacken and Yorck’s Prussian Corps. He had about 95,000 men at his disposal.

Macdonald proceeded to carry out his orders with Lauriston moving into Goldberg (Zlotoryja) on 23 August, Gérard fighting at Niederau then striking camp between Niederau and Neudorf, Souham reaching Liegnitz (Legnica) and Rothkirch, and Sebastiani Rothbrünning and Liegnitz. Ney was recalled by Napoleon and because of an imprecise order took his corps with him. By the time the mistake was noticed and countermanded, Macdonald’s movements had suffered a delay of two days. On 26 August the French continued their advance towards Jauer (Jawor) which led to the Battle on the Katzbach (Kaczawa).

Early on the morning of 26 August Yorck broke camp to take up position in alignment with Sacken and Langeron. Because of the very heavy rain, this manoeuvre was performed with some difficulty and it was not until 10 o’clock that Yorck was in position between Brechtelshof and Bellwitzhof. Blücher had ridden to Brechtelshof that morning where he had received Intelligence reports indicating the enemy’s positions. As the French had moved since 24 August, Blücher assumed that they had gone over to the defensive. He thus chose to launch an attack; Sacken was to move on Liegnitz; Yorck was to cross the Katzbach at Dohnau and Kroitsch (Krotoszyce) and thence to Steudnitz (Studnica), cutting off the French corps in Haynau (Chojnow) from Liegnitz; Langeron was to cross the Katzbach at Riemberg, occupy the heights at Hohberg and Kosendau, and cover the flank of the advance on Liegnitz.

Before these manoeuvres could be executed, however, news of the French advance was received. Both sides advanced into contact with each other and started an encounter battle. Lauriston and Gérard moved on Seichau (Sichow). Langeron just had time to deploy between Hermannsdorf and Schlaupe (Slup), completing this by about 12.30 p.m. Yorck’s vanguard was also in action by this time, but his riflemen were unable to fire because of the heavy rain and they were driven back by Sebastiani’s horse artillery.

At about 2 p.m. Macdonald advanced towards the sound of the guns. On the way he met General Souham who reported that because all the bridges over the Neisse between Liegnitz and Dohnau had been destroyed, he was moving towards Kroitsch. Macdonald ordered Division Brayer to occupy the heights above Nieder-Crayn which it did by 2.30 p.m. A reconnaissance by Gneisenau and Müffling established that the French were indeed advancing towards the heights above Nieder-Weinberg. Blücher resolved to push them back into the rivers at their back which were flooding because of the heavy rain. Sacken’s Corps had already commenced its attack before receiving this order. Yorck deployed with Horn and Hünerbein to the fore, the Prince of Mecklenburg in support and Steinmetz in reserve.

Hünerbein’s Brigade advanced first, its left flank resting on the Neisse, fired on by half a battery of French artillery on the Kreuzberg and opposed by three battalions of infantry. Two of these withdrew quickly behind the cover of the hill, the third held its position. The II. Battalion/Brandenburg Infantry Regiment (Prussians) wiped it out, using the bayonet and butt. The artillery and a supporting cavalry regiment were beaten back by two other battalions.

In the meantime Exelmann’s cavalry division (French) moved up and Division Brayer climbed the heights in front of it. The bridge at Kroitsch was blocked by cavalry, so Brayer had to leave his artillery behind. For the same reason, Cuirassier Division St.Germain remained in Kroitsch and did not come into action on 26 August.

Yorck continued his advance. On hearing that the French seemed to be about to break, Jürgass’ reserve cavalry was committed. With seven squadrons in his first line, three echeloned to the left, Jürgass advanced, the three squadrons on the left wheeling to capture a battery of artillery before being forced to withdraw by Brayer’s advancing infantry. His front line advanced through several squadrons and batteries before stumbling into the mass of the French cavalry who pushed him back to his starting position and captured part of his horse battery. The crisis of the battle had arrived. Exelmann’s troopers flanked Yorck’s artillery and charged the front of his infantry. With drums beating, four battalions from Yorck’s second line threw Exelmann back while six Prussian and four Russian squadrons took his left flank and front, driving him back to the valley.

Sacken’s Corps advanced through Eichholtz, his artillery deployed on the Taubenberg. Blücher ordered the general advance and committed his reserve cavalry. Brayer was driven back, as was the French cavalry. The infantry managed an orderly withdrawal to Kroitsch via Nieder-Crayn, leaving behind however its wagons and cannon. The exhausted Allies staged only a token pursuit.

Souham’s Corps arrived later that afternoon. Division Delmas crossed the Katzbach below Kroitsch towards Dohnau, dragging his cannon up the hill but to no avail as the Allied artillery soon forced a withdrawal. Unsupported, Delmas fell back on Kroitsch. Divisions Albert and Ricard crossed the Katzbach at Schmogwitz and were confronted by part of Sacken’s Corps. These divisions withdrew once news of the French defeat was received.

Langeron’s Corps had a less easy time. Faced by Gérard’s and Lauriston’s Corps, he was driven back with Hennersdorf falling at about 4 p.m. The French corps was unable to co-ordinate its actions and advanced no farther. Blücher saw that Langeron was having difficulties and ordered Steinmetz to cross the Neisse to attack the French in the flank and rear. The French were forced to give ground. At nightfall part of Hennersdorf was again in Allied hands and fighting went on there until midnight.

Casualties on both sides are a little hard to determine but it is known that the French lost 36 cannon, 110 ammunition wagons, two ambulances, four field smithies and as many as 1,400 prisoners.

This was an encounter battle which neither side was really anticipating. Blücher quickly seized the initiative but his victory was not as great as some writers of the time claim. Legends of thousands of French being driven into the raging waters of the Neisse bear little resemblance to fact. Losses of matériel was of more concern to the French.

Poor weather, bad conditions and general exhaustion prevented a rapid pursuit by the Allied forces, but Langeron took 2,200 prisoners and six guns from Lauriston while he was falling back to Goldberg. The Army of the Bober retired in two columns towards Bunzlau and Löwenberg and started to disintegrate on the way. Blücher urged his men on, but to little avail; they were tired, hungry and soaked through. His Prussian militia battalions suffered particularly and his horses were hungry.

On 29 August Langeron clashed with Puthod’s Division which was withdrawing across the Bober at Löwenberg; cut off and surrounded, it surrendered. The Russians took 4,000 prisoners, sixteen guns and three Eagles. The pursuit continued.

However, on 31 August Blücher received news of the Battle of Dresden. Assuming that Napoleon would leave the pursuit to his subordinates and return to Silesia to regain control of events there, Blücher ordered caution. The French having fallen back to the Lausitzer Neisse, the Allies took up positions on the Queis (Kwisa).

In all, the Army of the Bober had lost more than 30,000 men including 18,000 prisoners, 103 cannon, 300 wagons, three generals and three Eagles. It was on the point of total collapse. The Army of Silesia had fared little better, losing more than 22,000 men, but its morale, despite lack of supplies, remained unbroken.

We left the Army of Bohemia on the retreat after its defeat at Dresden. Vandamme was instructed to conduct the pursuit. The remainder of the army followed up, moving south towards Bohemia. There was every chance for the French totally to destroy the main Allied army and thereby decide the campaign. Napoleon, believing the matter to be very much in his favour, sent his Old Guard back to Dresden and had the Young Guard halt at Pirna. Then he heard the news of Macdonald’s defeat on the Katzbach. He had already been informed of Oudinot’s fate at Grossbeeren. A successful pursuit of the Army of Bohemia would more than reverse these set-backs.

Vandamme, moving along the road from Pirna through Peterswalde (Petrovice) and Tellnitz (Telnice) was getting into a position where he could cut off the Allied retreat. They had to do something to stop this. An improvised but successful defence was made at Priesten (Prestanov), Vandamme’s pursuit was checked and the remaining passes into Bohemia were kept free. If this could be done for another day, the Army of Bohemia would be able to escape the pursuit. In the meantime Kleist’s Corps of Prussians had gone missing. He had found all the roads through the woods and hills of this part of Saxony blocked except the one which he knew Vandamme had used. Taking a great risk, he moved on Vandamme’s rear.

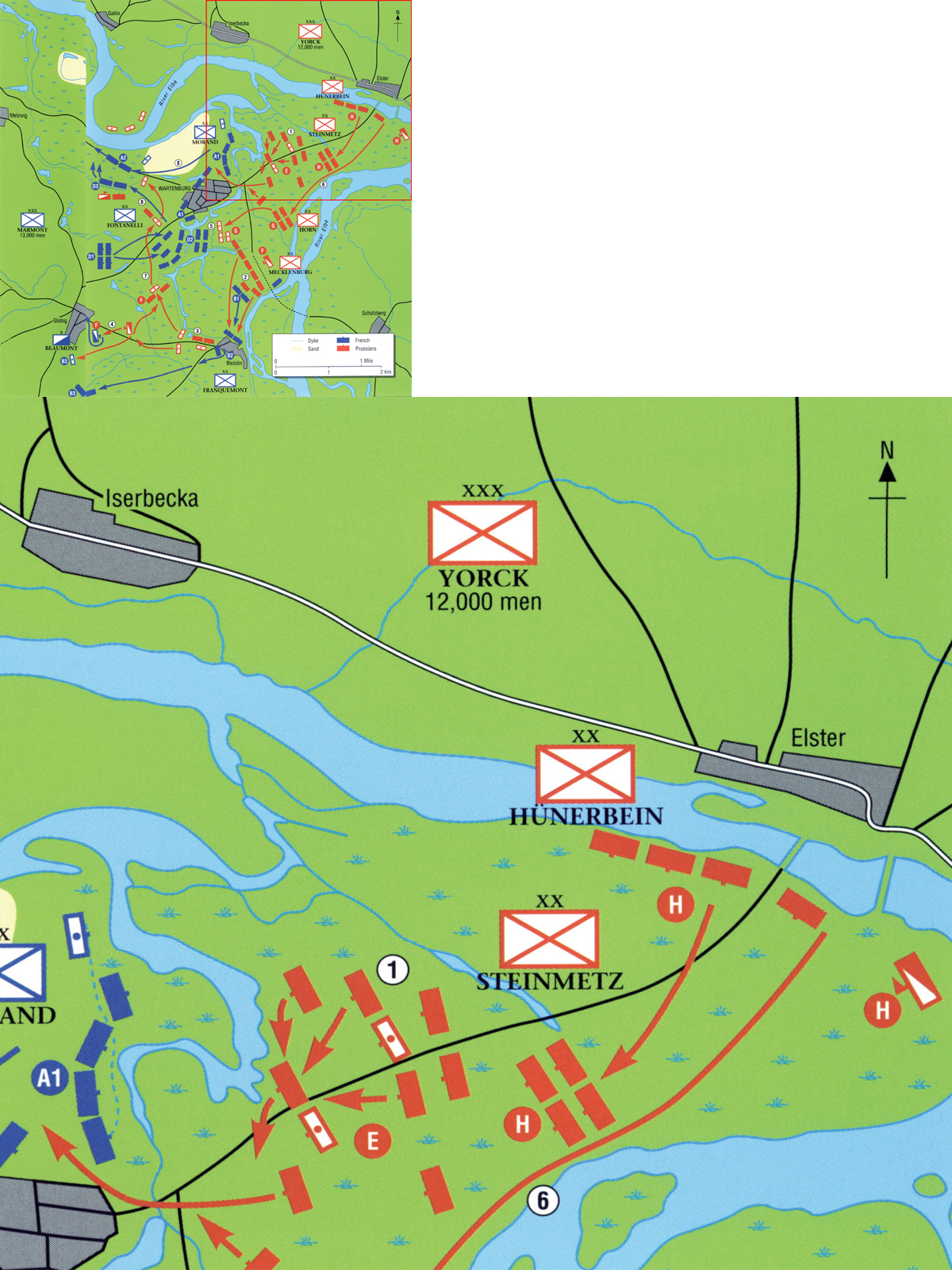

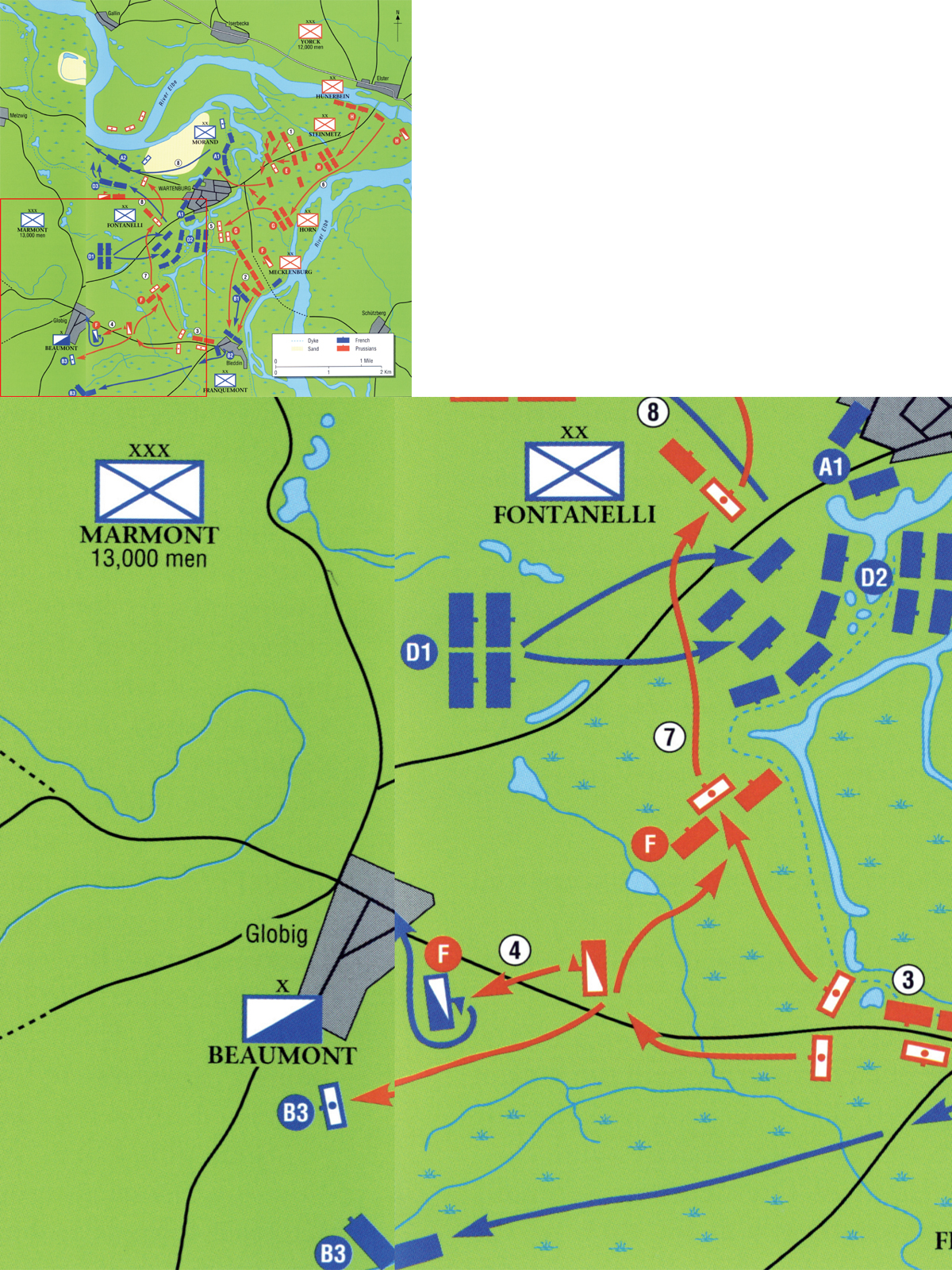

Battle of Wartenburg, 3 October 1813: The Breakthrough

Forces Involved.

FRENCH:

A. Division Morand.

B. Division Franquemont.

C. Brigade Beaumont.

D. Division Fontanelli.

PRUSSIANS:

E. Brigade Steinmetz.

F. Brigade Mecklenburg.

G. Brigade Horn.

H. Brigade Hühnerbein.

1. Once Mecklenburg crosses the Elbe, Steinmetz moves up and ties down Morand frontally.

2. Mecklenburg forces Franquemont (B1) back and then out of Bleddin (B2).

3. Mecklenburg then continues his manoeuvre on the rear of the French position.

4. Beaumont tries to stop him but is thrown back.

5. Meanwhile, Horn storms the dykes, the lynchpin of the French position, which are held by Fontanelli (D2).

6. Hünerbein moves up in support.

7. Mecklenburg turns the French rear, forcing them to withdraw.

8. French withdraw.

The Russian Guards at Priesten on 29 August, 1813. This was a delaying action fought the day before Kulm. The terrain is worth noting. The French were advancing down a narrow pass where a small force could hold them up. The valley side shown was very steep and that on the other side of the river in the centre of the picture was almost as steep. There would be no chance of escape to the sides, one could only move forwards or backwards. Now when Kleist’s Prussians appeared at Vandamme’s rear, the stage was set. The fighting on this day was to be a victory for the French. Contemporary lithograph.

On 30 August, the battle between the Austrians and Russians on the one hand and Vandamme’s Corps on the other started up again. The Russians held Priesten, the French Kulm (Chulmec). The Prussians marched from Nollendorf (Naklerov) on Kulm and the rear of the French. A cannonade from Prussian guns made it clear to Vandamme what his situation was. He chose to abandon his wagons and artillery and cut his way through Kleist. Only part of his men managed to do that. His corps ceased to exist but went down with honour. It lost about 10,000 men, two Eagles, five Colours and 82 guns in a confused but dramatic fight. All the gains made at the Battle of Dresden were wiped out in one fell swoop.

The first phase of this campaign was now over. Let us now look at the results to date.

Napoleon’s strategy was, fighting from a central position, to engage one enemy army with the bulk of his forces, holding off the other two, and thereby achieve a decisive victory. This strategy came close to success at the Battle of Dresden but eventually failed. The Allied strategy was for each of the armies to retire when faced by Napoleon in person, to engage and defeat his subordinates when confronted by them only and eventually to unite their three armies for the decisive battle. On the whole, this strategy had succeeded. In fact, the only defeat suffered was when the Army of Bohemia challenged the Emperor in person.

French losses of men and matériel were large. The Armies of Berlin and the Bober had been mauled. Vandamme’s Corps had been wiped out. Although the Army of Bohemia had suffered a major defeat at Dresden, the subsequent destruction of Vandamme’s Corps had more than made up for this.

The inherent weaknesses of the Napoleonic military system were largely to blame. Where Napoleon in person fought, the chances of victory were good; where his personal guidance was lacking, the chances of success were low. One of the main lessons of warfare in the age of mass conscript armies learned by the Prussians was that a uniformly trained general staff was necessary to command armies of this size. The Napoleonic command system was too inflexible to learn this lesson. The Emperor could broach no successful rivals, but without them he was unable to win this campaign. As time went on his chances of victory were dimin ishing. The decisive battle he sought was eluding him. With a growing number of victories to their credit, the Allies were growing more confident. With the threat of reinforcements arriving from Russia, Napoleon urgently needed to regain the initiative. He decided to head for Berlin again, crush the Army of the North and relieve his garrisons at Küstrin and Stettin. He was on the point of setting off when news of Vandamme’s defeat at Kulm came in. He could not leave Dresden unguarded. How could he now obtain the success he needed?

Kulm, 30 August, 1813. With the battle raging in the centre background of this lithograph by F. Hofbauer, King Frederick William III of Prussia orders an Austrian dragoon regiment into the fray.

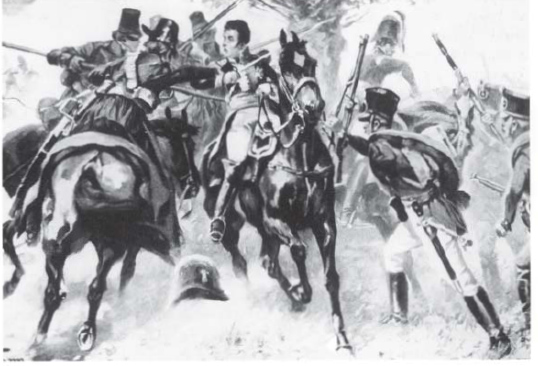

The capture of General Vandamme at Kulm by Cossacks and Russian Jäger. His aide General Haxo (background) was also taken prisoner. The generals were in the middle of a column of retiring French infantry when a small group of Cossacks boldly rode up and plucked the two unfortunate commanders out. The infantry were so surprised by the Cossacks that they did not fire.

The Emperor decided to send Ney off in the direction of Berlin, leave Macdonald on the Bober, remain in Dresden with his reserves and await an opportunity to strike at Blücher or the Crown Prince of Sweden as and when possible. He then chose Blücher for his coup de grâce and moved towards Silesia. Blücher withdrew. Napoleon now realized that this was a stratagem and decided not to follow.

Meanwhile, the Army of Bohemia advanced towards Dresden. Napoleon rushed back there. Ney continued his advance on Berlin and was confronted by Tauentzien’s Prussians at Dennewitz. Tauentzien’s force consisted largely of militia formations. Although driven back by Fontanelli’s Division in a short fight that morning, Tauentzien had held out long enough for Bülow to move up. He used his cavalry to cover the withdrawal and rallying of his defeated infantry and prevented a pursuit by the enemy.

The battle began that afternoon with some of the most bitter fighting of the campaign. Thümen was driven back by Morand’s artillery and left two guns behind. Hessen-Homburg then moved up, throwing Morand back, thereby gaining the higher ground above Nieder Görsdorf where he deployed his artillery. Morand took up a new position, his artillery deployed on higher ground to his fore, his infantry with its flanks against a wood and the town of Dennewitz. Hessen-Homburg decided that it was pointless to assault this position.

In the meantime Reynier moved up. His Saxons were deployed from Göhlsdorf to Dennewitz. Durette took up positions at Dennewitz. Krafft and parts of Hessen-Homburg stood in opposition to them. A battalion of Prussians was driven out of Göhlsdorf. The Saxon artillery was deployed but the Prussians opposite them got the upper hand.

The capture of General Vandamme by Cossacks at Kulm, 30 August 1813. (By K.H. Rahl.

Bülow, assured support from the Swedes and Russians in the Army of the North, decided on the offensive before more French arrived. He committed everything he could cobble together, knowing that Borstell was close to hand and more of the Army of the North were on their way. Supported by Swedish artillery, he captured Göhlsdorf. Borstell arrived but the Allies could make no further headway against Reynier. At about 3.30 p.m. Oudinot arrived in support. The French counter-attacked, recapturing Göhlsdorf and driving back Borstell. The situation was now critical for Bülow; his infantry was exhausted, his artillery unable to get the upper hand and his reinforcements still some way off. Ney saved him. An order arrived telling Oudinot to move his troops to Rohrbeck in support of Ney’s right flank which was being pushed back. Oudinot carried out his orders despite Reynier’s objections and pleas for support. Bülow attacked again, driving the Saxons back and recapturing Göhlsdorf. On the other flank Thümen and Hessen-Homburg were having some success against Bertrand, forcing him back to Rohrbeck. The Prussian advance came to a halt for lack of ammunition, but fresh Russian artillery broke Bertrand with salvoes of canister fire. Shortly after 5 o’clock the Allies had won a victory on the French right.

The situation remained stable on the French left until fresh Russian and Swedish troops arrived, forcing Reynier to retreat on Oehna. The entire retreating Army of Berlin met here and order broke down completely, the retreat becoming a rout. Only the Russo-Swedish artillery and some cavalry were fresh enough to pursue and the latter brought in a wealth of trophies. The Russo-Swedish infantry were too exhausted to pursue after their forced march to the battlefield.

At Dennewitz the Württembergers, among Bertrand’s best troops, were mauled. Reynier’s Saxons, so long a faithful ally of the Emperor’s, were shattered. Ney, not having expected or desired a battle that day, nevertheless got carried away, and sabre in hand on his charger, led attacks personally instead of commanding his army. Oudinot, still smarting from his defeat at Grossbeeren, was ultra-careful in executing his orders, arrived late and failed to use his initiative. Raglowich’s Bavarians, part of his corps, were thus only on the periphery of the battle. They did not share the same fate as Napoleon’s other German allies.

Action at Dennewitz. The Prussian 1st Life Hussars break through Polish lancers here. Painting by Richard Knötel.

Captain Egloff of the 1st Life Hussars takes Colonel Le Clouet, Ney’s adjutant, prisoner. Painting by Werner Schuch.

The Bavarian Division Raglowitsch in action at Dennewitz against Prussian militia. A number of contemporary observers commented with some bitterness that the liberation of Germany from French domination was in part characterized by Germans fighting with determination against Germans. Franquemont’s Württembergers also fought with distinction in the battle. Reynier’s Saxons also suffered heavily. Painting by E. Zimmermann.

Ney’s army was totally defeated. His attempts to rally his routed forces were to no avail. The Prussians lost more than 10,000 men. The French lost about 22,000 with 53 guns, 412 wagons and four Colours.

Dennewitz was the last major battle in this campaign for a month. The following weeks were characterized by indecision on both sides. Napoleon’s situation was deteriorating daily. Except for certain bridgeheads, he abandoned most of his positions on the right bank of the Elbe. In doing so, he indicated that he no longer hoped to free the besieged garrisons on the River Oder and beyond. Saxony was slowly running out of food and supplies for his army. He was no longer in a position to achieve a decisive victory. The correct military decision would have been to cut his losses, fall back to the Rhine, gathering the garrisons to his rear, obtain fresh supplies of men and matériel and resume the offensive again in 1814. However, Napoleon the politician took precedence over Napoleon the general. To abandon Germany might well endanger the survival of his regime. Having given up Germany, would he ever get it back? He sat in Saxony awaiting events while the Allies considered what, if anything, to do next. It was Blücher’s actions, as always, that shook everyone out of their lethargy.

To achieve a decisive victory over Napoleon, the Allies needed to concentrate their forces. Currently, only one army, the Army of Bohemia, was on the left bank of the Elbe, the other Allied armies being on the opposite bank. A crossing of the Elbe needed to be secured, a manoeuvre both dangerous and difficult when attempted in the face of the enemy. The points at which such a manoeuvre could be attempted were limited by the fact that the French had garrisons at Dresden, Torgau, Wittenberg and Magdeburg. All bridges were guarded so the Allies needed to build pontoon bridges at points where the French would be unable to intervene. Blücher took this highly risky venture upon himself, crossing the Elbe with his Army of Silesia in close proximity to Bertrand at Wartenburg. Despite ferocious resistance the manoeuvre was successful and precipitated the Battle of Leipzig later that month. It was, in effect, the decisive strategic move of the campaign and, as with so many such manoeuvres in military history, it was favoured by a disproportionate amount of good fortune; had Allied Intelligence and French deployment been better, it might not have been achieved.

Duke Charles of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Commander of a brigade in Yorck’s Corps, Duke Charles played a significant role at the Battle of Wartenburg. A man of great personal courage, he was severely wounded in the fighting at Möckern on 16 October. Drawing by Franz Krüger.

Once across the Elbe Blücher’s troops would have to cross marsh, ditches, dikes and woodland before reaching Wartenburg and the relatively open country beyond. Bertrand was waiting, his troops deployed to hinder any attempt at staging a breakout. Yorck’s Corps of Prussians crossed the Elbe and was used to secure the bridgehead. Langeron’s Russians followed. The subsequent contest was characterized by determined and bitter fighting.

Mecklenburg was the first to cross the pontoon bridges. Pushing back the French skirmish line in the Hohe Holz, he made slow progress through broken country. Once the morning fog had cleared it became apparent that it would not be possible to storm the town of Wartenburg frontally, so he decided to take it from the rear, deploying part of his brigade to the front of the French position to cover this manoeuvre. The strongpoint on the French right was the town of Bleddin. This was occupied by Franquemont’s Württembergers who would offer a determined defence. Mecklenburg’s flank guard in front of Wartenburg was taking heavy casualties so reinforcements were moved up to assist him. Steinmetz’s Brigade took up the position in front of Wartenburg, relieving Mecklenburg who could now unite his brigade for the assault on Bleddin. Horn’s Brigade moved up in support, Hünerbein’s Brigade crossed the bridges and remained in reserve.

At Bleddin, the Prussians forced the Württembergers back and pushed them away from the main French position around Wartenburg, thus exposing their rear. Horn’s Brigade stormed the French position to the south of Wartenburg, engaging Fontanelli’s Italians. They were thrown back at bayonet point. Wartenburg was now no longer tenable and Bertrand withdrew. Horn’s assault was the decisive blow. His brigade had to move through a densely planted orchard, cross a stream and a well-defended dike while under flanking fire from artillery before crossing a second dike. Fontanelli was defending a natural fortress and it is no surprise that Horn was almost defeated. The first assault came to a halt and was on the point of being broken when Horn himself rode to the fore and personally led the attack of the II.Battalion/Prussian Life Regiment against five enemy battalions. This charge carried the position. The Prussians lost 67 officers and 1,548 men from a total of about 12,000. The French sustained fewer casualties but lost about 1,000 prisoners, eleven guns and 70 wagons.

General Yorck doffs his cap to the II Battalion of the Prussian Life Regiment in recognition of their heroic role in the Battle of Wartenburg. Led by their brigade commander General von Horn, this battalion stormed the main French position, a natural fortress, with the bayonet and thereby decided the battle.

Next day the Army of the North crossed the Elbe and joined forces with Blücher’s Army of Silesia. All three Allied armies were now on the same bank of the Elbe and Napoleon’s position in Saxony was no longer tenable.

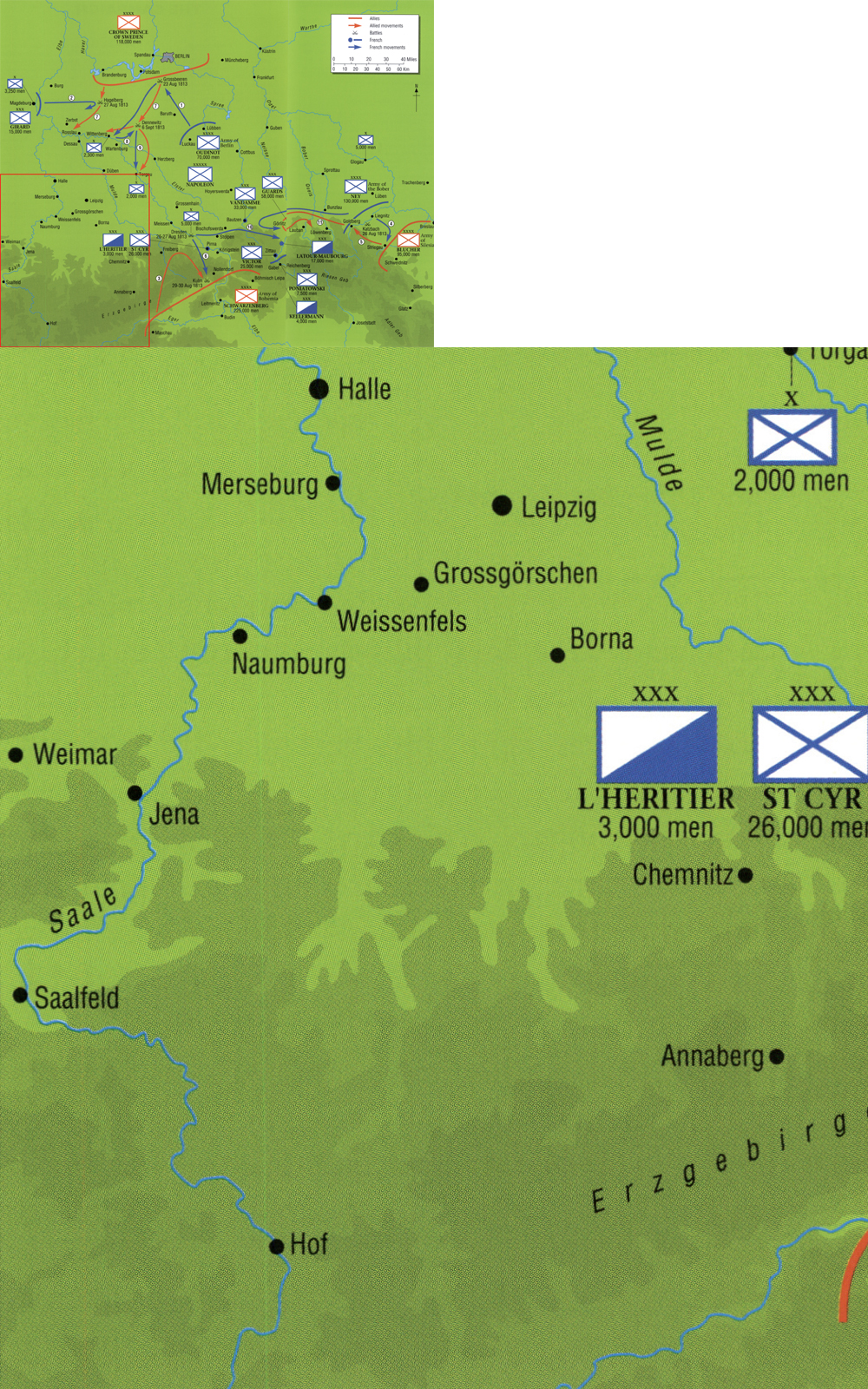

After the successful crossing of the Elbe by the Armies of Silesia and the North on 3 and 4 October Napoleon was faced with only two opponents. He would have to strike at one with as much of his army as he could afford to take with him while leaving sufficient troops to hold the other in check. At Dresden he had 116,000 men and 389 guns available (Macdonald, Lobau, St.Cyr, Sebastiani and the Guard). Souham, deployed along the Elbe between Strehla and Meissen, gave him another 16,000 men and 61 guns. Between Eilenburg and Bitterfeld were the remains of the Army of Berlin together with Marmont and Latour-Maubourg, some 72,000 men and 203 guns. Along his southern front, from Altenburg to Freiberg, were Victor, Lauriston, Poniatowski and Kellermann, 44,000 men and 156 guns. Leipzig was defended by 7,000 men and 22 guns.

Lefebvre-Desnouëttes’ Cavalry Corps, covering the western approaches to Leipzig, consisted of 5,000 sabres and six guns. On the march to Leipzig were the troopers of Milhaud’s Cavalry Division (in part veterans from Spain) and Augereau’s Corps, a total of 13,000 men and fourteen guns.

Napoleon had two choices. Within three days he would have been able to concentrate 180,000 men against the Army of Bohemia (itself of similar strength) while holding Blücher and the Crown Prince of Sweden in check with Ney, Marmont and Souham, a total of 87,000 men. Within four days he would have been able to concentrate 200,000 men against the Armies of the North and Silesia while having Murat (67,000 men) hold up the Army of Bohemia. In either event Dresden would have to be abandoned, but at this stage of the campaign it was of less significance as the magazines had been run down and the the surrounding countryside was exhausted.

There could be little doubt as to which was the best choice. To advance south against Schwarzenberg, who was only just moving through the passes from Bohemia, would have resulted in his backtracking and avoiding battle. Blücher and the Crown Prince of Sweden were only two to three days’ march from Leipzig and the loss of this important town would have cut Napoleon off from France. For them to withdraw across the Elbe in the face of the enemy would be a difficult manoeuvre; they had committed themselves at last. He gathered his forces and moved north.

In the face of this advance, however, Blücher fell back in a westerly direction towards the Army of the North. After conferring with the Crown Prince it was decided to move jointly towards Leipzig. News that Napoleon was advancing towards them with the bulk of his forces started to arrive at their Headquarters from 8 October. On the 9th Blücher’s forces, let down by faulty reconnaissance, only just managed to escape being surprised by the French. Blücher and the Crown Prince were clearly in great danger of being forced to fight Napoleon alone with their backs to the Elbe. The Crown Prince, turning down Blücher’s request to take up a joint position over the Saale, preferred to stay nearer the Elbe for safety’s sake. Blücher, true to character, was itching to advance on Leipzig, risking all so as to give the Army of Bohemia every chance of fully deploying in Saxony. The Crown Prince erred on the side of caution; he was not going to engage Napoleon alone. Blücher fell back towards the Crown Prince. Napoleon again struck out against air. He was never to get the decisive battle he wanted. His chances of winning this campaign continued to diminish.

In the meantime the Army of Bohemia, facing less opposition, was slowly making its way north. News that the Bavarians had changed sides on 8 October and were indeed about to join the Allied side with 50,000 men changed the political and military situation. This army was astride Napoleon’s lines of communication and could cut off his retreat. News also came in that Blücher had occupied Halle and that the French had abandoned Dresden. All the indications were that Napoleon was going to fall back to the Rhine and evacuate Germany. A determined advance now would be to Austria’s advantage. Opposition from the French was likely to be minimal and Austria’s prestige and position at the peace negotiations would gain from such an advance.

Again Napoleon had two choices. One was to fall back to the Rhine. The other was to strike at the Allied armies individually and immediately. News of the advance of the Army of Bohemia clarified his thoughts. He gathered his forces and moved south with the Guard, Bertrand and Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry to join Murat. Ney and Macdonald were also to join him, while Reynier, after destroying the bridge at Aken, was also to move on Leipzig. The scene was set for the decisive battle of the campaign.