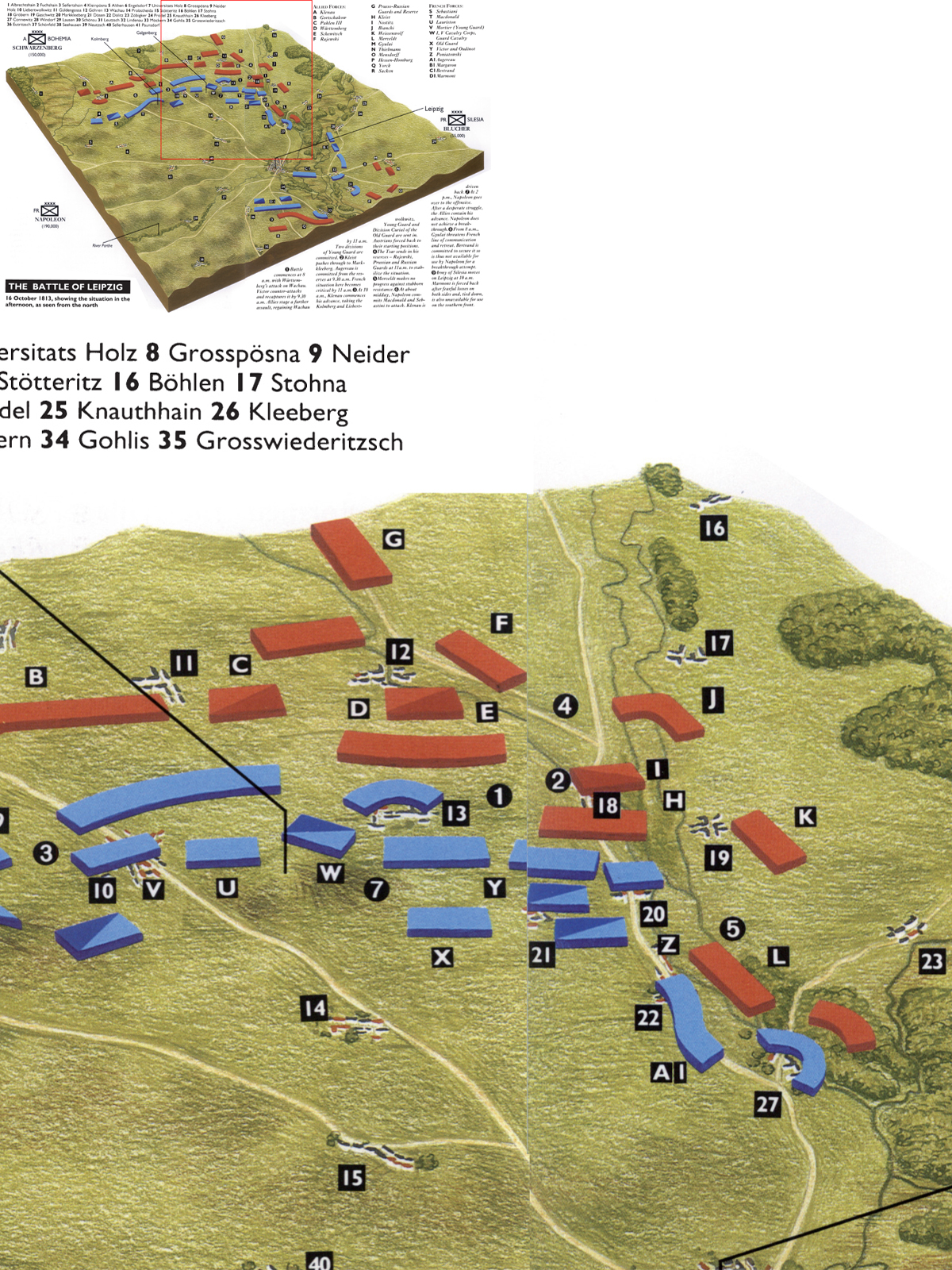

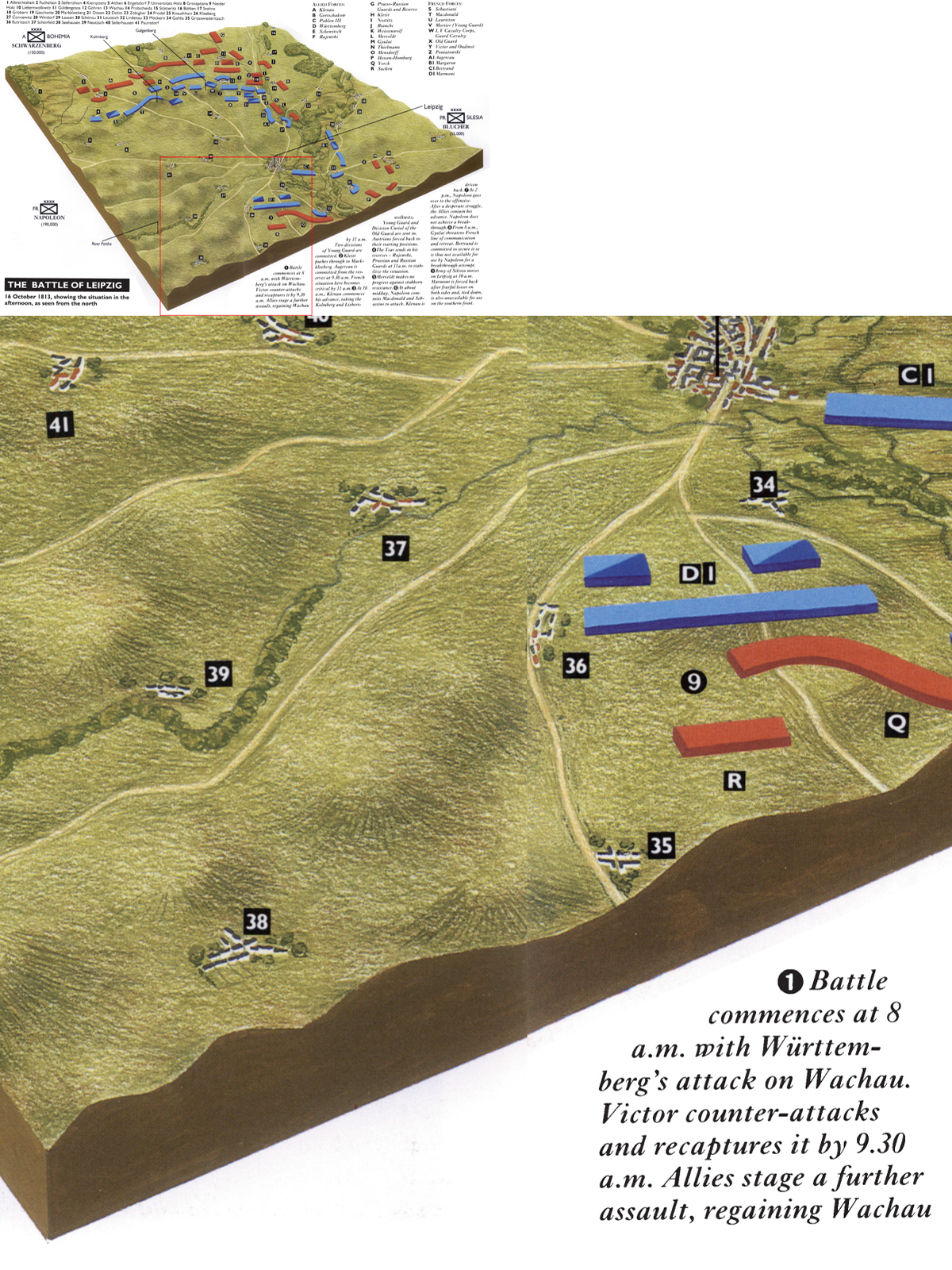

The autumn of 1813 had been rather wet and river levels were higher than normal. The countryside was muddy, hindering movement. South and east of Leipzig ran a line of hills which, although not impassable, provided good defensive positions for all arms. The outlying villages, with their solid buildings, firm roads and walls, could become fortresses. The area to the north of Leipzig was flatter, the major obstacles being the rivers and marshes. To the west the land was so marshy that it was virtually impassable. The road west, to France, ran along a causeway to Lindenau. Possession of this was vital to Napoleon’s communications. Leipzig itself was a rectangle with four main points of access – the Grimma Gate, Peter’s Gate, Neustädter Gate and the Halle Gate. Parts of the old fortifications were still there but no works of significance were left. Leipzig had not been prepared for defence.

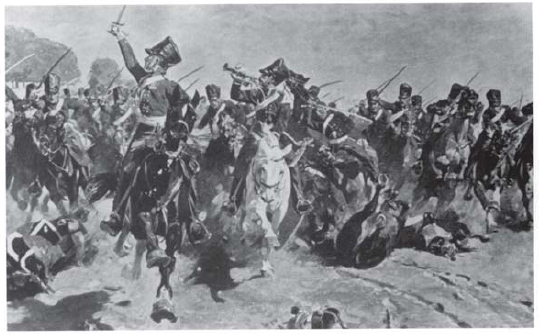

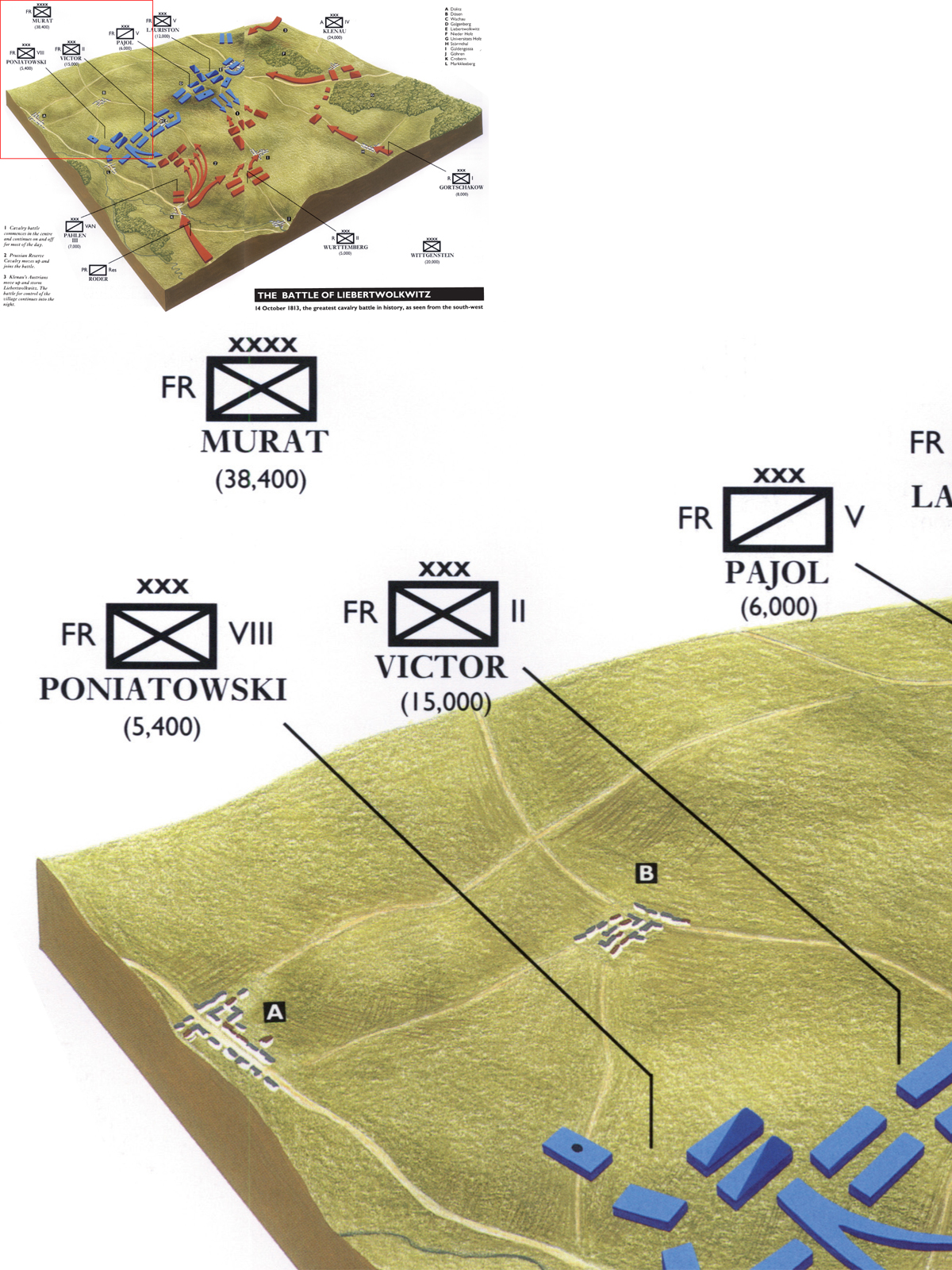

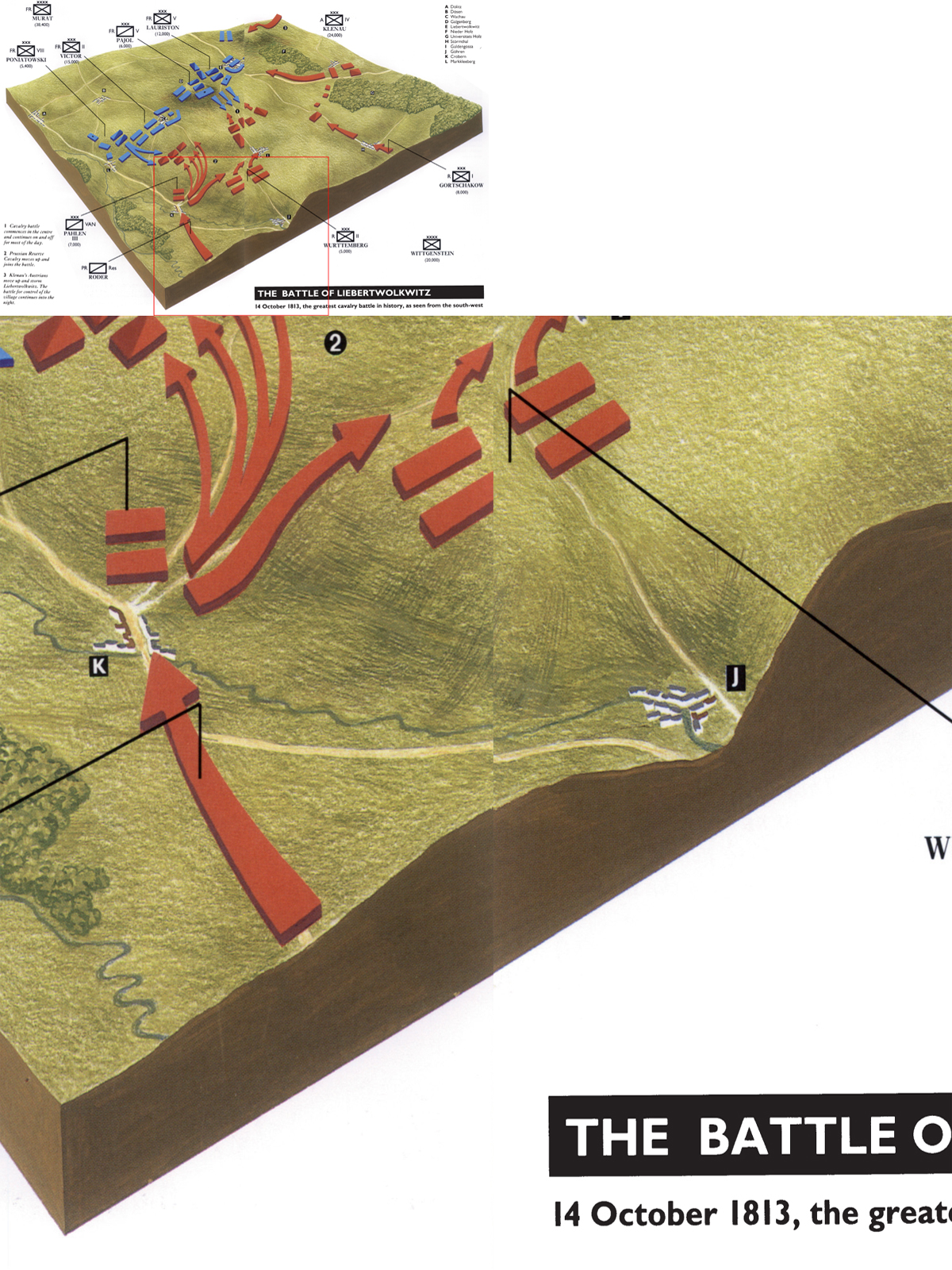

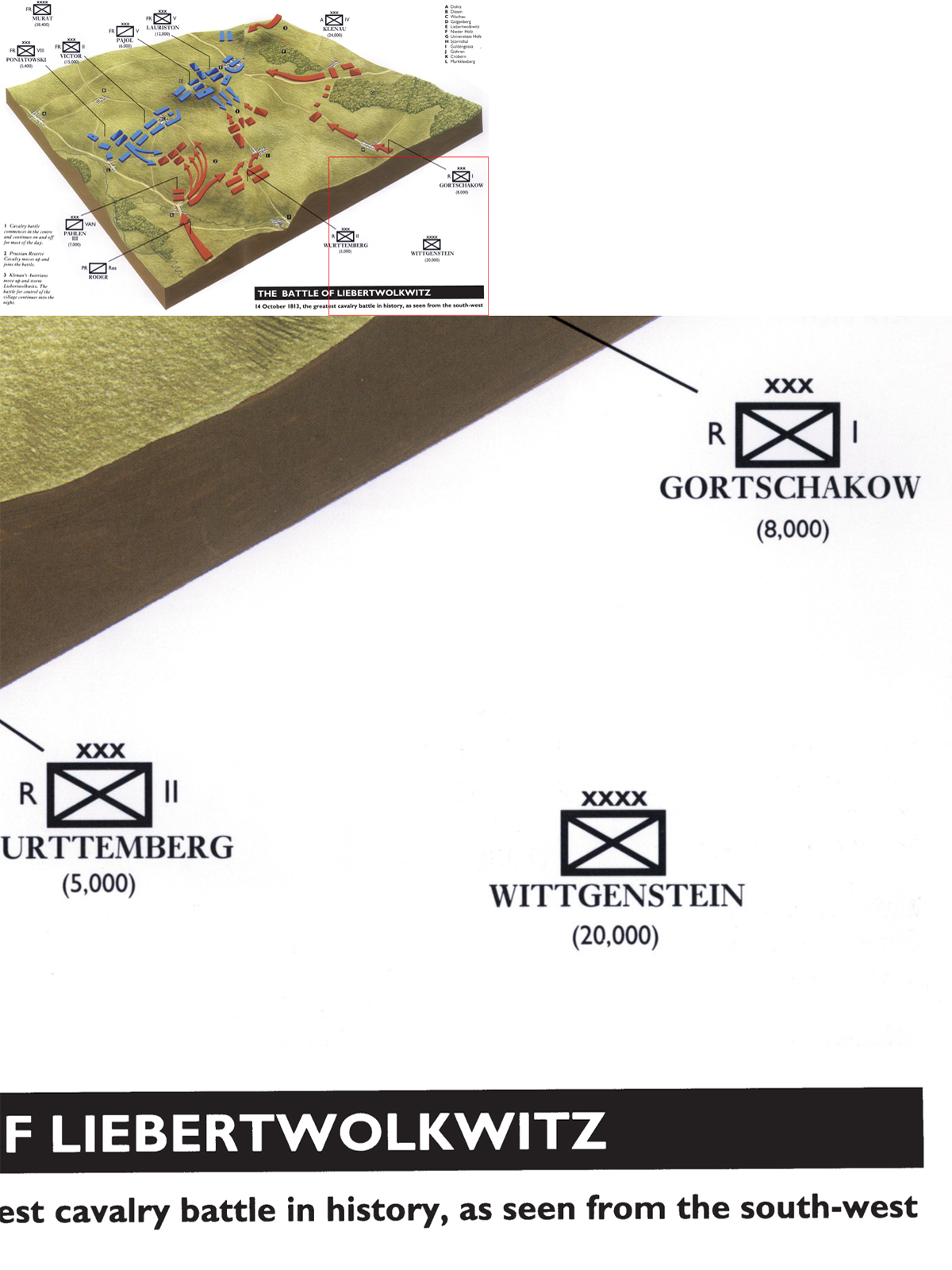

This great conflict opened with what became the largest cavalry battle in history, at Liebertwolkwitz, south of Leipzig. Murat was in overall command of the French forces which consisted of the Corps of Poniatowski, Victor, Lauriston and the Cavalry Corps of Kellermann and Pajol (who had replaced Milhaud on 12 October). He was opposed by the Russian General Wittgenstein commanding the vanguard of the Army of Bohemia.

The terrain surrounding Murat’s position consisted largely of gentle slopes coming up to flat-topped hills. Thanks to recent heavy rain the ground, particularly in the hollows, was wet and muddy which hindered movement. The plateau stretching from Liebertwolkwitz to Güldengossa and Wachau was about 1,400 paces wide. The highest point, the Galgenberg (Gallows Hill) was an excellent artillery position and the hill itself had the additional advantage of hiding everything behind it. Murat had a strong position with villages and hills along his front. The Allies would have to advance uphill in open ground against artillery.

Napoleon was advancing towards Leipzig. He needed to buy time to allow his troops to concentrate while keeping the Army of Bohemia as far away as possible from Blücher and the Crown Prince. His instructions to Murat were to hold up the Allies for as long as possible but not to get involved in heavy fighting.

Wittgenstein was under the impression that all he had in front of him was a rearguard protecting the French withdrawal. He moved his forces forward quickly in an attempt to delay the French. Little did he know that they were there in some force with every intention of offering a fight. Thus Liebertwolkwitz was an encounter battle into which the Allies blundered. Wittgenstein’s vanguard under Count Pahlen III (Russian), was ordered to move on Liebertwolkwitz via Cröbern and Güldengossa. Prince Eugène of Württemberg (commander Russian II Corps) was ordered to deploy his force into two lines and advance from Magdeborn through Güldengossa towards Liebertwolkwitz. Prince Grotschakow II was ordered to march through Störmthal and then deploy. Kleist’s Reserve Cavalry under Röder was ordered to Cröbern in support of Pahlen. His main body was to remain in Espenhain in reserve. Later on, 3rd Russian Cuirassier Division would follow Röder. Rajewski’s Grenadier Corps was also in reserve.

Murat deployed Victor between Markkleeberg and Wachau. Lauriston covered the Galgenberg and Liebertwolkwitz. A grand battery was deployed on the Galgenberg with the cavalry hidden behind it. A division of the Young Guard was in Holzhausen and Augereau’s Corps was on the Thornberg.

Pahlen sent his Cossacks to reconnoitre the enemy’s dispositions. They reported that the area between Markkleeberg and Wachau was occupied in strength. The Grodny Hussars were sent up in support. The advance continued until it became clear that the French were going to resist. By now the Allies had committed themselves to battle. The French grand battery forced the Sumy Hussars to fall back and the first French cavalry attack started with Division l’Héritier moving forward in column supported by Division Subervie. The Sumy Hussars charged the leading French regiment and forced it back. The second regiment then threw back the Russian hussars but its advance was halted by the Prussian Neumark Dragoons who in turn were thrown back by the next French regiment. In the meantime the Sumy Hussars had rallied, the Silesian Uhlans had moved up and the East Prussian Cuirassiers were preparing to charge the French column. While the French were rallying they were hit by the East Prussians frontally and the Silesians in the flank. They were thrown back to the starting-point with the Prussians in hot pursuit. At the Galgenberg the French reserves saw off the Prussians and in turn launched a pursuit which drove the Prussians back to their starting-point. This pursuit was halted and thrown back by the Neumark Dragoons who had just rallied from their first action; an officer of this regiment almost taking Murat prisoner. There was now a pause in the action.

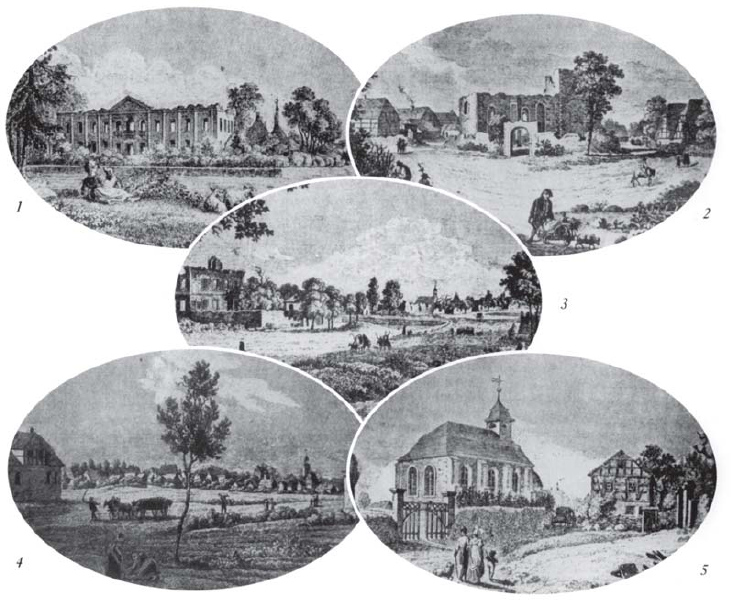

Wachau drawn shortly after the battle. This village formed an important point on the French defensive perimeter and was hotly contested during the battle.

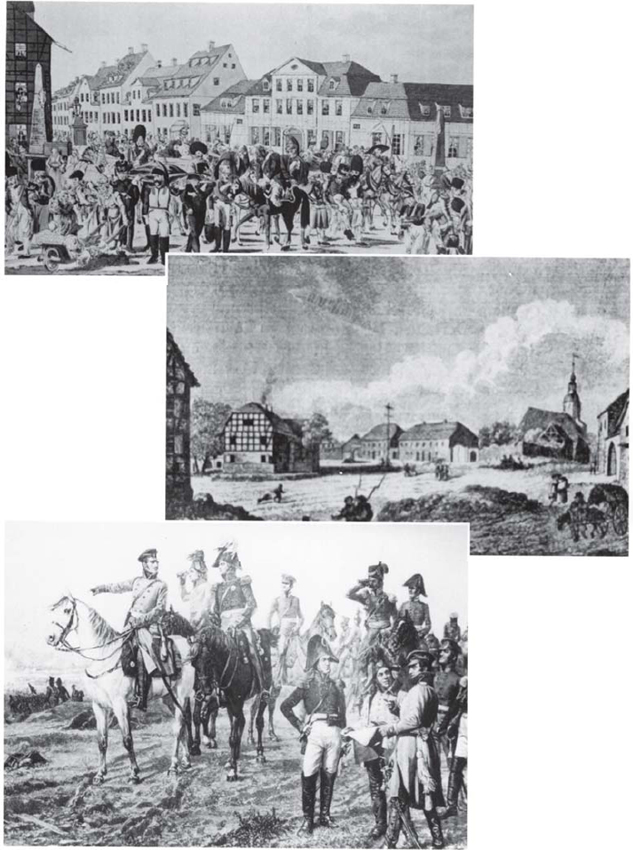

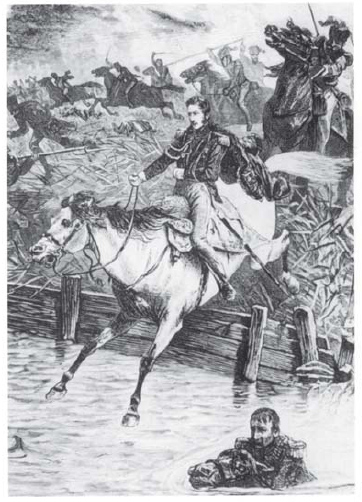

Murat at Liebertwolkwitz. This flamboyant French marshal came close to being taken prisoner twice during this cavalry battle. Lieutenant von der Lippe of the Prussian Neumark Dragoons had the honour of being the first to die trying! The charge Murat led at Eylau in 1807 did much to enhance his reputation. However, Liebertwolkwitz was not a repeat performance. He led good, experienced cavalry formations, but his tactical dispositions were poor and his inflexibility cost him the battle. The irony is that the lessons the French marshalate had taught their opponents by 1813 were the very lessons that Napoleon’s generals had forgotten – namely tactical flexibility. Painting by W. Camphausen.

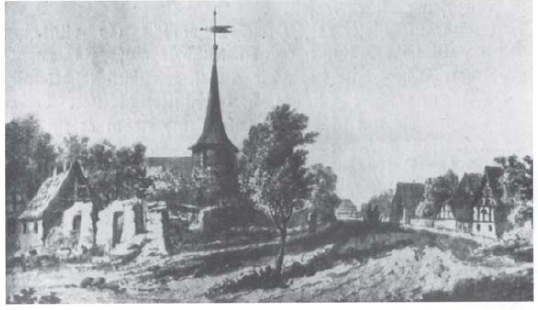

The Neumark Dragoons in action during the cavalry battles fought around Wachau on 14 October. This regiment played an important part in the flowing action of that day. Painting by C. Becker.

Leipzig on 14 October. The wounded are brought in from the fighting at Lieberwolkwitz. Note how the two soldiers in the right foreground are using a musket as a makeshift stretcher. In the left foreground are what appears to be a group of refugees, no doubt from one of the villages in the front-line. Geissler.

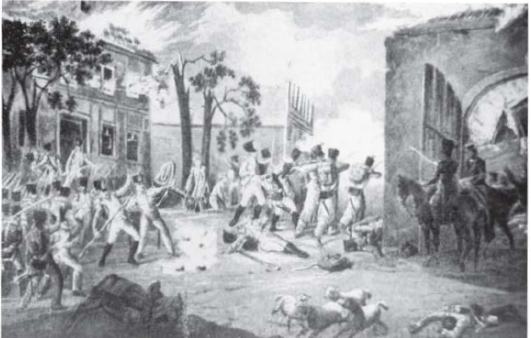

Liebertwolkwitz drawn shortly after the battle. The church in the background is where defending Austrians were massacred. This church still stands today and a memorial to these unfortunate Austrians can be seen there.

The three Allied monarchs at Leipzig, illustrating the cumbersome command structure of the Army of Bohemia. They are making comments and observations while their generals in the foreground do the same. Decisions were then fudged in committee. This slothful machine muddled its way to victory at Leipzig. Schwarzenberg, commander of the Army of Bohemia he appears, sensibly, to have found a more suitable task elsewhere.

The detailed studies of this action give a clear indication of how cavalry fought at this time – a charge followed by a counter-charge and pursuit by reserves which was broken off once the enemy brought his reserves into play. Meanwhile the first wave would be rallying for use later. It is worth noting here that the Allies were able to take on and hold their own against a larger French force because the latter favoured attacks in columns while the Allies tended to tie the French down frontally and decide the issue by gaining the flank of the unwieldy French column before it had a chance to deploy.

After a short clash on the Allied left, the affair degenerated into half-hearted skirmishing. On the Allied right the Austrians were moving up with the intention of assaulting the town of Liebertwolkwitz. The French defences were such that this attack ground to a halt. It was now about midday. Wittgenstein ordered Klenau to take Liebertwolkwitz, the key to the French position. Once this town was in Allied hands the French would have to withdraw their grand battery from the Galgenberg, leaving the entire position to the Allies. Klenau deployed his men skilfully – border troops to the fore in skirmish order, cavalry on the flanks protecting his infantry drawn up in assault columns. The Austrians stormed Liebertwolkwitz and, after bitter street fighting lasting two hours, it fell to them. The French artillery drew up outside the town and prevented the Austrians advancing further.

The way was now clear for the Allies to resume their advance on the centre of the French position. The French launched another attack which was driven back. Flanking attacks by the Prussian cavalry broke open the French formations and again Murat was almost taken prisoner. The pursuit continued to the Galgenberg where French gunners were cut down by Prussians attempting to drag off their guns. This proved their undoing because the French brought up reserves of cavalry and infantry, surrounding the Silesian Cuirassiers who had to hack their way out, suffering heavy losses. They fell back to their starting-point under pursuit. The French counter-attack was in turn beaten back. The action degenerated into skirmishing.

Murat’s orders had been to hold off the enemy and not to get heavily involved in battle. Once his initial attempt to throw back the Allies on their approach march had failed, he should have conducted a fighting withdrawal. Instead, he became deeply involved in the fighting and committed more and more troops. At 2.30 p.m. he launched his final charge, deploying his cavalry into a long column which charged right into the heart of the Allied position before being thrown back by flanking charges supported by Klenau’s Austrians. The French were broken and were pursued well over the Galgenberg. They were unable to launch any more attacks that day.

Meanwhile the battle for Liebertwolkwitz continued. Wittgenstein failed to provide Klenau with any support and left him out on a limb in the town while Murat brought up fresh infantry. At 4 p.m. he attacked Liebertwolkwitz. This assault was successful and some Austrians were trapped and slaughtered in the church. The Austrians withdrew from the southern outskirts of the town after nightfall.

Prince of Schwarzenberg, commander of the Army of Bohemia. A good soldier who was in the unenviable position of having three monarchs present at his headquarters. What made his task even more difficult was the foreign policy of his government. Austria was not looking for a decisive victory in this campaign. Poor Schwarzenberg had not only to play the diplomat and politician but to do it all on a soldier’s pay! Engraving by M. Steinla.

Total Allied losses were 80-85 officers, 2,000-2,100 men and 600-650 horses. Details of French losses are unreliable but were probably greater. It is known that they lost two generals and 96 officers as well as 800 prisoners to the Austrians.

The battle itself ended rather inconclusively. With greater determination and commitment, Wittgenstein could have inflicted a defeat on Murat and possibly have brought the Battle of Leipzig to a conclusion more quickly. Murat was wrong to get so involved in the fighting and could have held the Allies off for just as long without losing so many men, particularly his precious mounted veterans. Significantly, the Army of Bohemia was now committed to fighting the decisive battle of the campaign.

The Allied forces were drawn up as follows:

1. Along the line Fuchshain – Grosspösna—Güldengossa—Cröbern under Wittgenstein’s command, Corps Kleist, Wittgenstein, Klenau and Pahlen. In reserve, Grenadier Corps Rajewski and Russian Cuirassier Brigade Gudowitsch, the Russo-Prussian Guards and Reserve at Rötha.

2. At Gautzsch, between the Rivers Pleisse and Elster, Corps Merveldt and the Austrian reserves under the Prince of Hessen-Homburg.

3. Deployed against Lindenau, Corps Gyulai, Division Liechtenstein and the raiding parties of Thielmann and Mensdorff.

4. At Schkeuditz, the Army of Silesia. The total forces available to the Allies for the first day of the battle consisted of 202¾ battalions, 348½ squadrons and 918 guns. Including Cossacks, about 205,000 men.

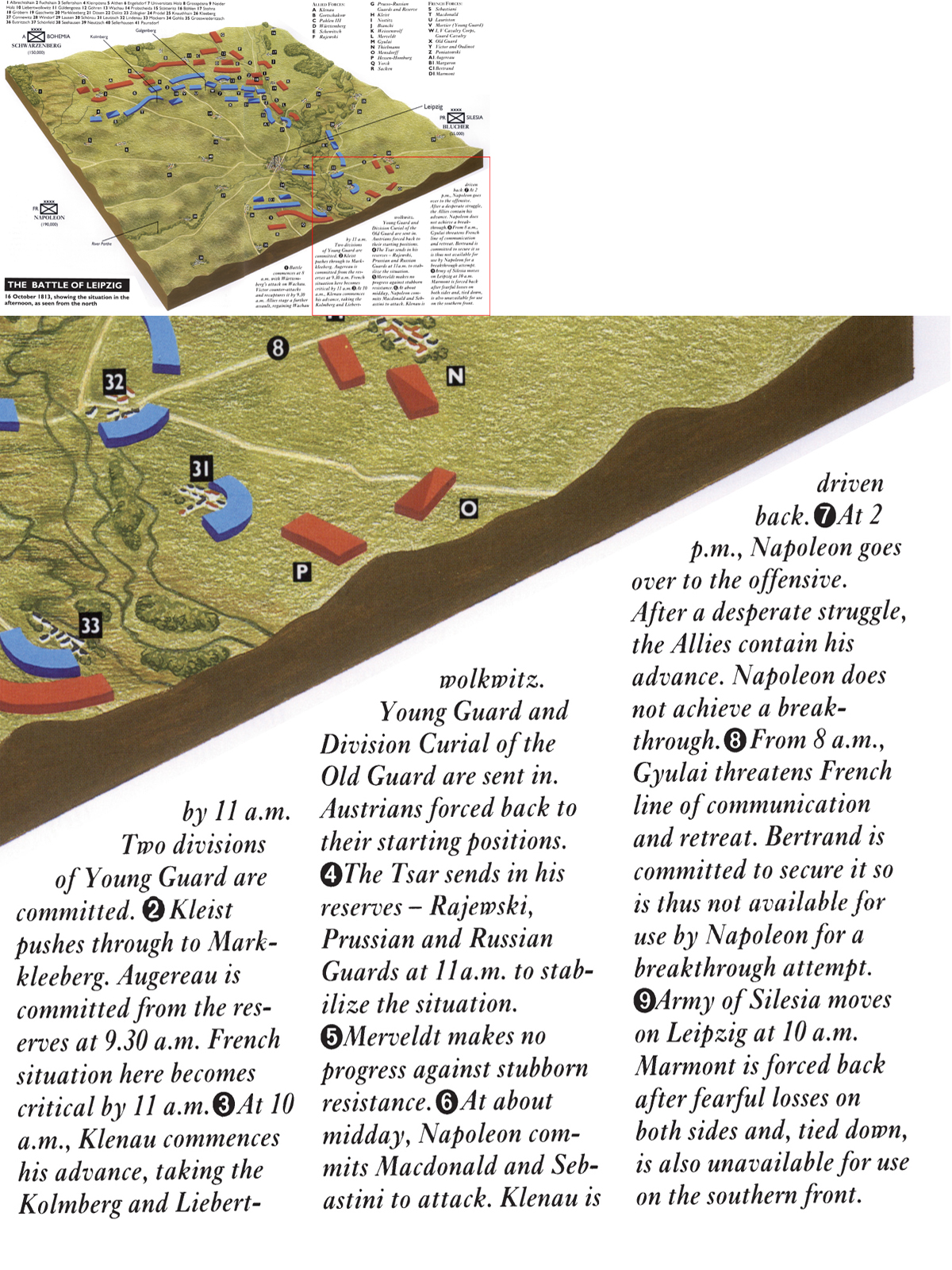

Napoleon gathered his forces. Believing Blücher was not in a position to threaten him that day and that the Crown Price of Sweden was still some way off, he decided to launch an offensive against the Army of Bohemia. For this, he had the following at his disposal: 1. South of Leipzig, either already in position or on its way, Division Lefol, Corps Poniatowski, Cavalry Corps Kellermann in echelon along the line Connewitz—Lössnig—Dölitz—Markleeberg. Corps Victor and Lauriston deployed between Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz. Behind Lauriston the Young Guard and Division Curial of the Old Guard. Corps Augereau behind Zuckelhausen. At Probstheida, Division Friant of the Old Guard, the Cavalry of the Guard and Cavalry Corps Latour-Maubourg. Marching to Holzhausen, Corps Macdonald and Cavalry Corps Sebastiani. To oppose the Army of Bohemia, Napoleon had: 488 guns and about 138,000 men. 2. At Lindenau. Part of the garrison of Leipzig under Margaron and Brigade Quinette of III Cavalry Corps, a total of 3,200 men. 3. On the northern front. Corps Marmont and the rest of III Cavalry Corps at Breitenfeld and Lindenthal. Division Dambrowski marching to Klein-Wiederitzsch. Corps Bertrand at Eutritzsch. Divisions Braver and Ricard marching to Mockau. Division Delmas of Corps Souham marching up from Düben. On the northern front, Napoleon had 186 guns and about 49,400 men.

In all, on 16 October Napoleon had 690 guns and about 190,000 men, excluding men guarding his baggage parks but without deduction for losses incurred on 14 October because no precise figures are available.

Taking into account Napoleon’s position, strength and dispositions, the chances of victory on 16 October were in his favour. The line of hills to the south and east of Leipzig made ideal artillery positions from which he could launch an offensive. They also hid his troop movements. The villages on the main roads were strong positions against which Schwarzenberg could not deploy easily and the muddy land between these would hold up any attack. In the decisive area to the right of the Pleisse, Napoleon had 138,000 men against 100,000 Allies who could expect the arrival of a further 24,000 men that afternoon. Napoleon now had his final chance to decide the campaign in his favour.

The weather was cold, wet and foggy. Wittgenstein had divided his forces into four columns. Column 1 under Klenau consisted of IV Austrian Corps and Prussian Brigade Ziethen which was to deploy between Fuchshain and the Universitätsholz (University Woods) and assault Liebertwolkwitz. Column 2 under Prince Gortschakow – Russian Division Mesenzow and Prussian Brigade Pirch – would advance between Störmthal and the Universitätsholz to support Klenau to the south and west. Column 3 under Duke Eugène of Württemberg – II Russian Infantry Corps and Prussian Brigade Klüx – was ordered to attack Wachau from the east, from Güldengossa. Column 4 under Kleist – Russian Division Helffreich, Prussian Brigade Prince August, Russian Cuirassier Brigade Lewaschow and Lubny Hussar Regiment – was to advance from Cröbern to between Markkleeberg and Wachau, take the heights between the villages and the villages themselves. Cavalry Corps Pahlen together with the Prussian Reserve Cavalry was to support Columns 2 and 3. In reserve were Grenadier Corps Rajewski and Cuirassier Brigade Gudowitsch. They formed up on the main road south of Gruhna.

At 8 a.m. the attack began with Duke Eugène advancing on Wachau which was quickly abandoned by the small occupying force. Attempts to break out of the village were halted by strong French artillery fire. Victor moved in for a counter-attack and threw out the Russians at the point of the bayonet. Wachau was in French hands again by 9.30 a.m. An artillery and musketry duel lasted until 11 a.m. when the Allies staged another assault on the village, driving the French out as far as their gun line to its rear. Allied losses were too high to pursue any further. The French counter-attacked and cleared Wachau but were unable to advance any further because of the Prussians and Russians engaged to their front. The fighting here was of such ferocity that of the 31 Allied cannon that opened fire at 8 a.m., only nine were still in action by 11 a.m.

Kleist meanwhile was slowly forcing Poniatowski’s Poles out of Markkleeberg in bitter street fighting. He had been forced to commit most of his reserves to get this far and by 11 o’clock his situation was critical. Because Klenau had yet to engage his column, Gortschakow contented himself by opening up with his artillery against Lauriston. His infantry, which was drawn up behind his guns, suffered terribly from the French counter-battery fire.

Klenau started his advance at 10 o’clock. The Kolmberg, an ideal vantage point, was unoccupied by the French so Klenau placed a detachment there. Liebertwolkwitz itself was occupied by only a small force of French who were quickly driven out except from the church and the northern end of the village. They soon counter-attacked and made the Austrians retrace their every step.

By 11 o’clock the situation on this sector of the front was becoming critical. The initial gains had been repulsed and it was clear that strong French reserves were approaching. Wittgenstein could not expect much help that day. Tsar Alexander reacted to this situation by committing Grenadier Corps Rajewski as well as the Russo-Prussian Guards. Moreover Schwarzenberg was ordered to move his reserves from the left to the right bank of the Pleisse. Merveldt was having no luck. Moving through the broken terrain on the left bank of the Pleisse was proving difficult. The bridge at Connewitz was barricaded and well defended. No other crossing was available. His only success was to take the Manor House at Dölitz.

Connewitz drawn shortly after the battle of Leipzig. The village played an important role in the fighting on 16 October, being the site of a bridge over the Pleisse.

Probstheida. This strategically important village was defended by Victor on 16 October. Situated on the lower slopes of a mound at a major road junction, possession of this village determined who was master of the southern entrance to Leipzig itself.

The storming of the sheep farm at Auenhain on 16 October. This farm changed hands several times during the course of that day. Drawing by C.W. Strassberger.

Napoleon visited Murat’s headquarters on the Galgenberg at 9 o’clock to be briefed on the situation. The Allies had stolen a march on him and he had to deploy those reserves immediately to hand before he could bring up the remainder of his forces and take the offensive. Victor and Lauriston were reinforced by the artillery of the Young Guard, and at 9.30 a.m. Augereau was sent to support Poniatowski. The infantry of the Young Guard and Division Curial of the Old Guard were sent to support Liebertwolkwitz. Division Friant of the Old Guard moved up to the sheep farm at Meusdorf. As the fight for Wachau intensified, he had two divisions of the Young Guard under Oudinot and the mass of his cavalry move up to its rear. French losses were very heavy and Napoleon waited impatiently for the arrival of fresh troops. As the morning fog was lifting his advantage in numbers was evident and he itched to take the offensive. Macdonald cleared the Kolmberg and approached Seifertshain to take the Allied right flank. Once he had done this, Napoleon was going to advance along the whole of the centre of this front with the intention of breaking the enemy front entirely. Macdonald’s attack went well. He achieved his objectives and was prevented from advancing further only by the timely intervention of several squadrons of Prussian cavalry. Klenau’s Austrians were in full retreat. Sebastiani’s cavalry threw back the Austrian cavalry to their front and again it was the Prussians, Röder’s Reserve Cavalry, that prevented further pursuit. Platow’s Cossacks appeared on Sebastiani’s left, indicating the approach of Bennigsen’s army. The French desisted from any further advance so Klenau had time to rally his men between Grosspösna and Fuchshain.

Liebertwolkwitz had fallen to the French. The Austrians fell back to the Niederholz where the Baden artillery and men of Lauriston’s Corps engaged them and pushed them back yet farther. Gortschakow and Pahlen fell back to realign with Klenau’s new position. Augereau was thrown in against Kleist who was still holding his forward positions at Markkleeberg. Seeing the approach of Rajewski’s grenadiers, Kleist committed his last reserve in a vain assault on Wachau. He was driven back but managed to hold most of Markkleeberg. By 2 p.m. the Allies, except for Kleist, had been driven back to their starting positions.

Napoleon now formed his army up for the decisive attack. He deployed all his artillery reserves to the fore for the bombardment. Victor, the Young Guard, Lauriston and the Old Guard supported to the rear by the mass of the French cavalry formed up for the assault. Marmont had yet to arrive. In fact he was currently fighting Blücher at Möckern. Ney was unlikely to appear and Bertrand had been sent off to defend Lindenau. At 2 o’clock the Emperor could wait no longer. He ordered the general advance without Marmont.

Nostitz’s Austrian troopers charged and saved Kleist’s Prussians from destruction. A counter-charge by Saxon cuirassiers stabilized the position again for the French. At 2.30 p.m. Bordesoulle’s cavalry charged the Allied grand battery in the centre, broke through Württemberg’s infantry and, with eighteen squadrons, a total of 2,500 sabres, took 26 guns. The charge continued into Schewitsch’s Russian Guard Cavalry Division which was also thrown back. The French attempted to continue their advance to the Allied Headquarters but a timely flanking charge by a Russian cuirassier regiment togther with a counter-charge by the Russian Life Guard Cossacks saved the Allied monarchs from capture. Ten squadrons of Prussian cavalry joined the mêlée and the situation in the centre turned in favour of the Allies, the French cavalry being driven back all the way to their own grand battery. The French infantry continued their advance but met determined resistance along the entire front. Klenau’s Austrians barricaded themselves in Seifertshain and held the village until nightfall. A flanking attack by Bianchi’s Division threw back the Young Guard and Lauriston. Markkleeberg was recaptured. Division Weissenwolf pushed on, with the situation on the French right becoming so critical that Napoleon had to commit part of the Old Guard as well as Corps Souham.

By 5 p.m. the situation had clearly turned in favour of the Allies. Napoleon’s cavalry had been thrown back, his main assault on the Allied centre defeated and the bulk of his reserves committed to shore up his front. It was evident that the Allies still had uncommitted reserves and Napoleon saw little point in trying a further assault with the last of his.

Emperor Francis I of Austria. The geographical position of the Habsburg Empire in the centre of Europe always meant that it had to fear several enemies – the Russians to the east, Turks to the south, Prussians to the north and French to the west. Never strong enough to ‘go it alone’, it was essential for every ruler of this Empire to have the right allies at the right time to ensure the balance of power in Europe. Despite several military defeats in the Napoleonic Wars, the Austrian Empire came out on the winning side and made sure that no one else gained too much power. In this respect, Francis I was highly successful.

Gyulai’s situation was self-evident. With the forces available to him and in the terrain in which they would have to fight, it would be impossible to win a decisive victory and occupy Leipzig. Instead, his strategy was to threaten the French line of retreat and draw as many of their forces upon himself as possible, in which he was successful. Bertrand’s Corps, so desperately needed by the Emperor on the southern front, had to be detached to secure Leipzig itself. Napoleon had come so close to victory over the Army of Bohemia that just one more Corps at his disposal would probably have settled the matter. Gyulai was ready for action at 7 a.m., but waited until the sound of cannonfire from the direction of Wachau began at 8 o’clock, before commencing his attack. He succeeded in driving the French out of several villages around Lindenau before the appearance of Bertrand’s Corps at 11 o’clock put an end to his offensive. A counter-offensive by Bertrand at 5 p.m. was driven off. Gyulai had played his part in ensuring Allied victory at Leipzig.

Napoleon had not expected the Army of Silesia to become involved in any serious fighting on 16 October. He had ordered Marmont to join him at Liebertwolkwitz and might well have won the battle that day had he been able to leave the northern front. But reports of Blücher’s approach from Halle forced Marmont to turn back. He drew his forces up between Möckern and Lindenthal. The village of Mockern was the key to his position. He had 19,500 men at his disposal.

At 6 a.m. Blücher’s cavalry marched off to reconnoitre the French dispositions. Shortly after 8 o’clock a report from the Crown Prince of Sweden arrived which made it clear that he was not going to participate in any fighting that day. Cannonfire could be heard coming from Lindenau and Wachau so Blücher decided to take the offensive alone with the intention of drawing enemy forces on himself so that they could not be used elsewhere in the battle. Again, this was a crucial decision which prevented Marmont joining his master on the southern front thereby facilitating a French victory.

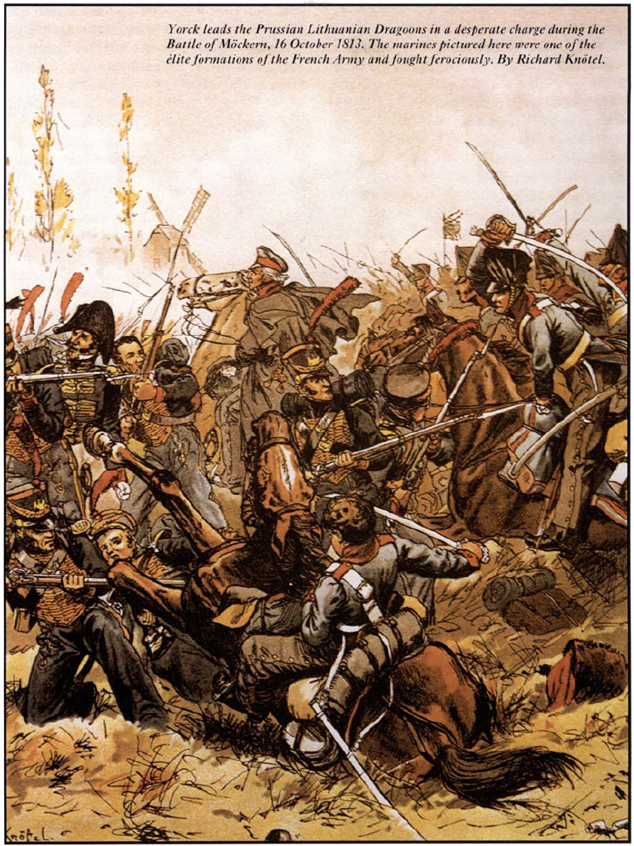

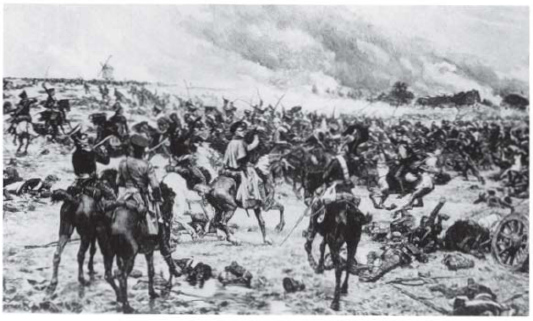

Shortly after 10 o’clock Blücher’s troops moved forward for the attack. Marmont withdrew his outposts. Langeron moved on Gross and Klein Wiederitzsch while Yorck advanced towards Lindenthal and Möckern. Yorck was quick to recognize the strategic significance of the village of Möckern and from 2 p.m. he assaulted it. Time and again the village changed hands and losses to both sides were fearsome. Reserves were brought up. An equally bitter struggle for possession of Gross and Klein Wiederitzsch was taking place between Russians and Poles. At nightfall, the French fell back to Eutritzsch.

Lindenau in 1813. This village was at the end of the causeway across marshy ground to the west of Leipzig. Its possession was essential to cover the French line of communications and, if need be, retreat. The Austrian Gyulai successfully teased the French here and forced them to commit precious reserves when their use on the southern front might have brought victory.

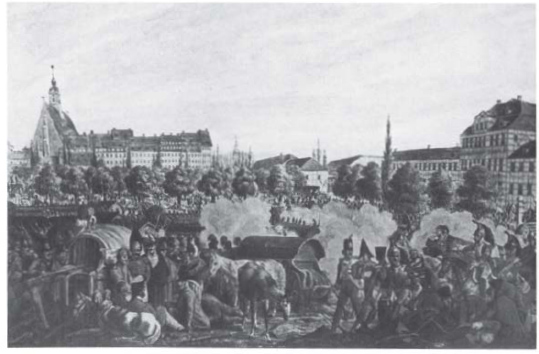

General Yorck sends in his cavalry reserve in one last desperate attempt to take Möckern. The struggle for this village was probably the most desperate, bitter and bloody of the entire campaign. Yorck’s Corps was mauled here and remained ‘hors de combat’ for the remainder of the battle. His sacrifice relieved pressure on the southern front. Painting by Werner Schuh.

The Brandenburg Hussars at Möckern. A rather dramatized impression of events that certainly were dramatic. Yorck’s cavalry took 35 cannon, two Colours and 400 prisoners in their final charge at Möckern on 16 October. Painting by O. Gerlach.

Yorck brought up 88 guns to support a further assault on Möckern. Brigade Mecklenburg successfully stormed the village. Division Compans counter-attacked and drove the Prussians out of the village again. Yorck was down to his last infantry reserve, Brigade Steinmetz, which he committed at 5 o’clock. It broke against the determined defence of Marmont’s troops. Yorck now had only his cavalry left. In desperation he threw in his horsemen against the village. Such was the force of their charge that they swept aside all resistance, capturing 35 cannon, two Colours, five ammunition wagons and 400 prisoners. Marmont was able to fall back to Gohlis unmolested. Losses in this battle were fearful. Yorck’s Corps, which had borne the brunt of the fighting, had started the day with 20,800 men. At the end of the day 5,600 had become casualties. Next day his four brigades were amalgamated to form two divisions. He had, however, taken 2,000 prisoners, one Eagle, two Colours, 40 cannon and numerous ammunition wagons. Langeron had lost about 1,500 men and had taken one Colour, thirteen cannon, numerous baggage wagons and several hundred prisoners. Marmont gives his losses at between 6,000 and 7,000 men.

The battle on the southern front had been a close-run affair. But for the timely intervention of the Tsar and the correct use of the reserves, the Army of Bohemia might well have suffered a decisive defeat. Had the Allies been able to force the crossing at Connewitz, they would have gained the French flank and rear and might well have used this to force a decision in their favour.

Napoleon might have had victory in his grasp but for the fact that the Allies had staged a surprise attack early that morning, forcing him to commit his reserves immediately. Moreover the fighting at Lindenau and Möckern had deprived him of the numbers he needed for a clear decision. Napoleon had no new forces to bring into play. The Allies could rely on the appearance of Bennigsen, Colloredo and the Crown Prince of Sweden. Napoleon had no hope whatsoever of a victory now. Retreat was the only sensible option. If he were to move his baggage train immediately, withdraw his troops through Leipzig and along the causeway through Lindenau, a rearguard deployed in Leipzig could hold up the Allies long enough for the manoeuvre to be accomplished. The rearguard itself could then withdraw and prevent any pursuit by blowing the bridge at Lindenau.

An impression of Leipzig by Johann Adam Klein. This painting features a mixture of French, Prussian, Austrian and Russian troops, and would appear to represent fighting on the southern front. Albertina, Vienna.

1. Lösnig. A village to the south of Leipzig. Held by Augereau on the morning of 18 October, it was eventually captured by Hessen-Homburg whose men suffered severely in the process.

2. Holzhausen. Held by Macdonald on the morning of 18 October, it fell to the Russians under Bennigsen.

3. Paunsdorf. It was at this village that the Saxon Army finally gave up fighting for the French Emperor.

4. Stötteritz. Once Paunsdorf had fallen to Bülow’s Prussians, Stötteritz became the centre of the French defence on the southern front.

5. Zweinaundorf. Defended by Lauriston on 18 October, it was stormed and captured by Bennigsen’s Russians.

But Napoleon could not leave without a victory. A retreat would no doubt result in his remaining allies deserting him. His army might well fall apart on the retreat. He would be abandoning the 140,000 men in his fortress garrisons. Perhaps he could now negotiate an armistice? He sent an ambassador to the Allies and formed his troops up in pouring rain, ready for battle on 17 October. He waited in vain. No attack came that day. Instead, the Allies brought up their reinforcements, rested their men, distributed fresh supplies of ammunition. Time was on their side. French losses the previous day had been horrific. Poniatowski had lost about a third of his men, Augereau a half; Marmont, Dombrowski, Bertrand and Macdonald had had great holes torn in their ranks. Ammunition was running low. The men were exhausted.

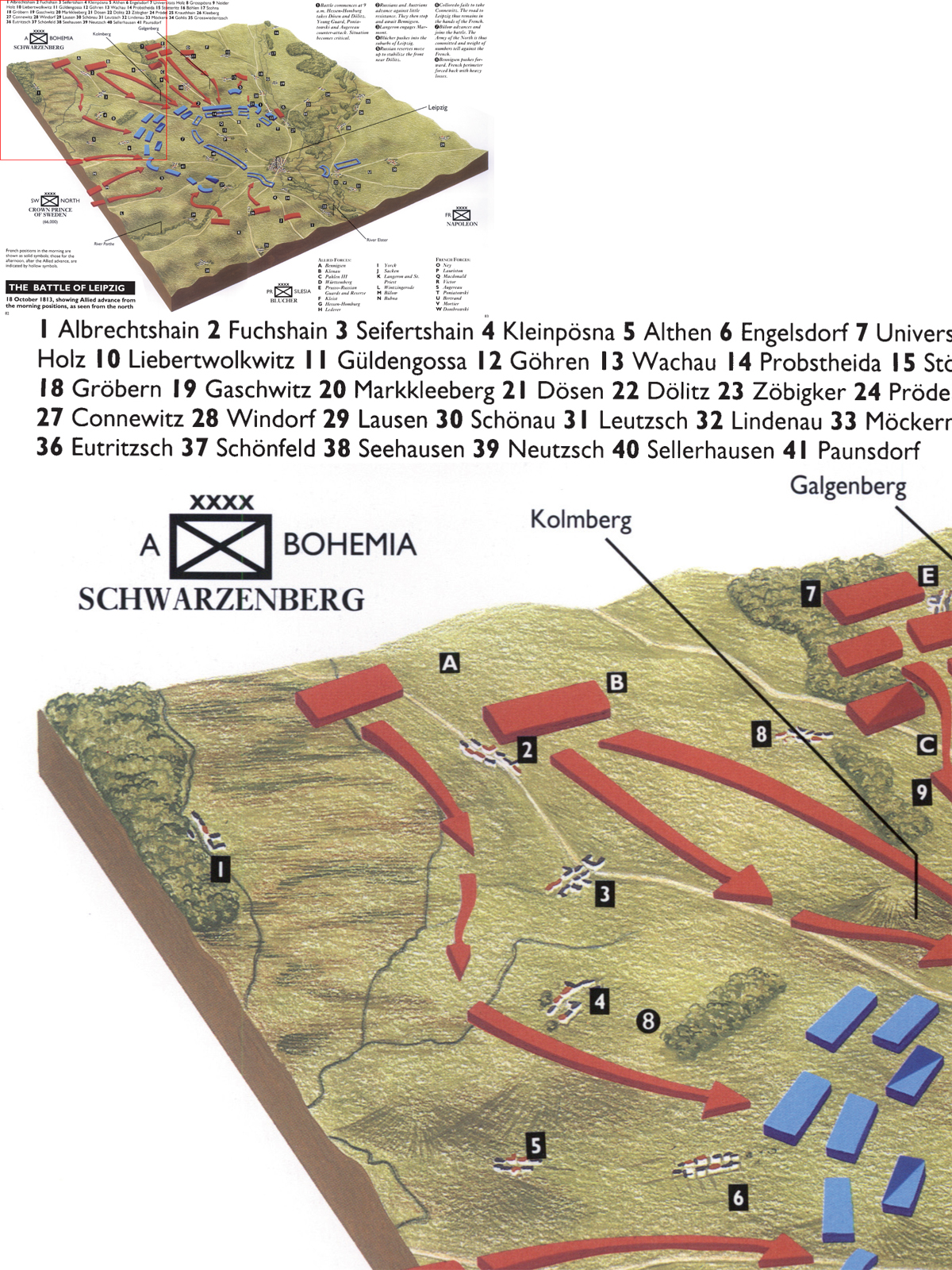

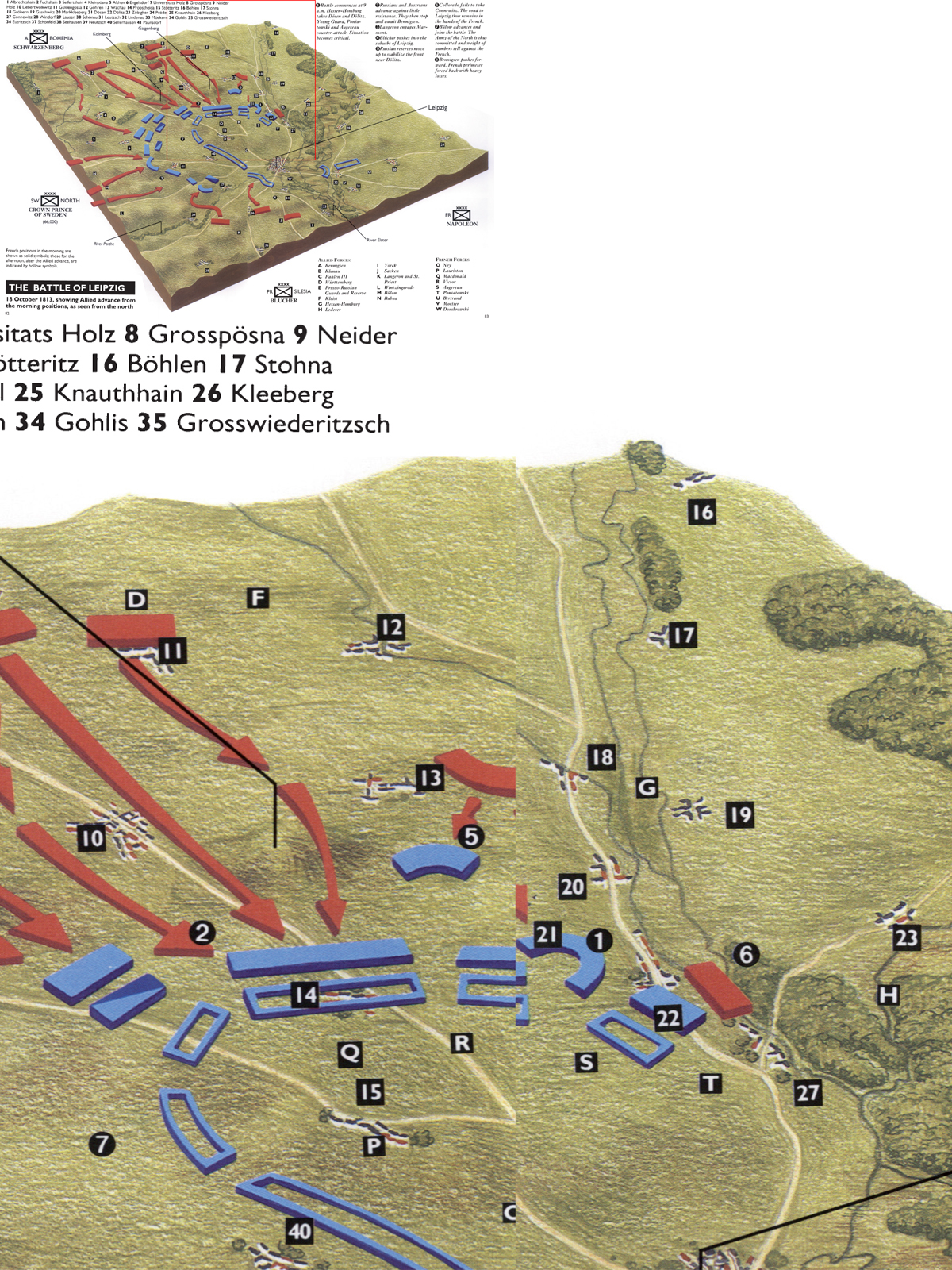

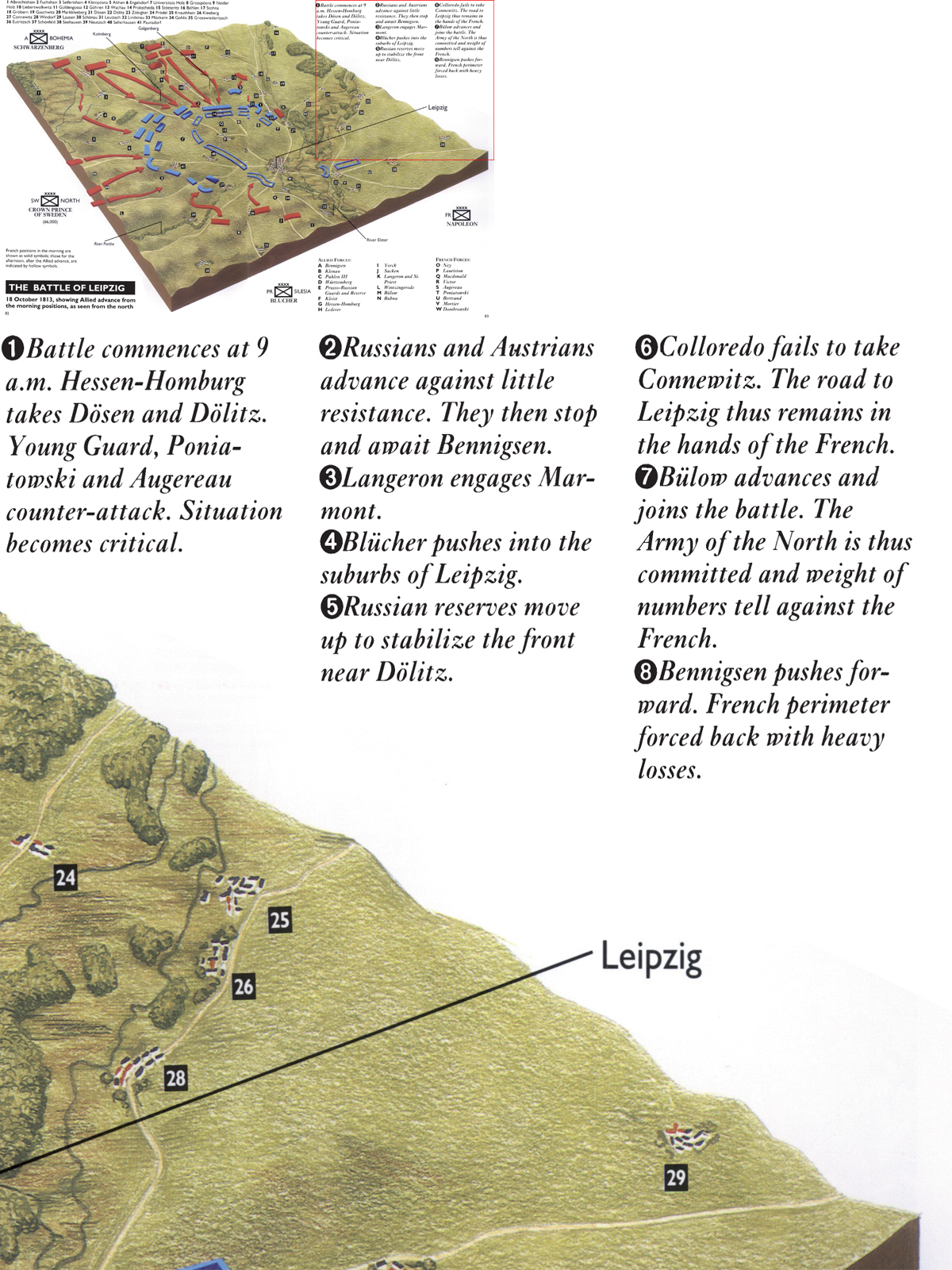

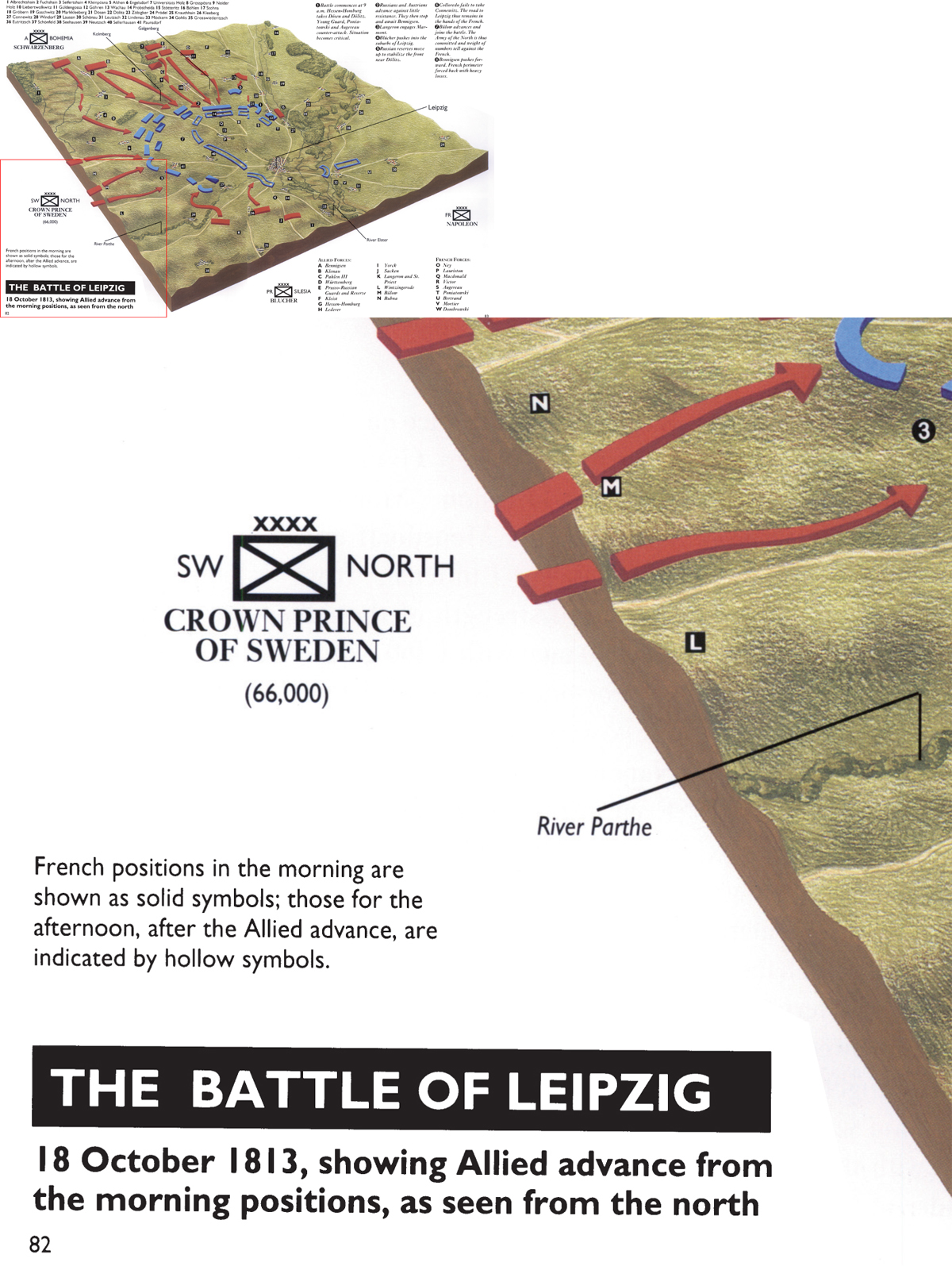

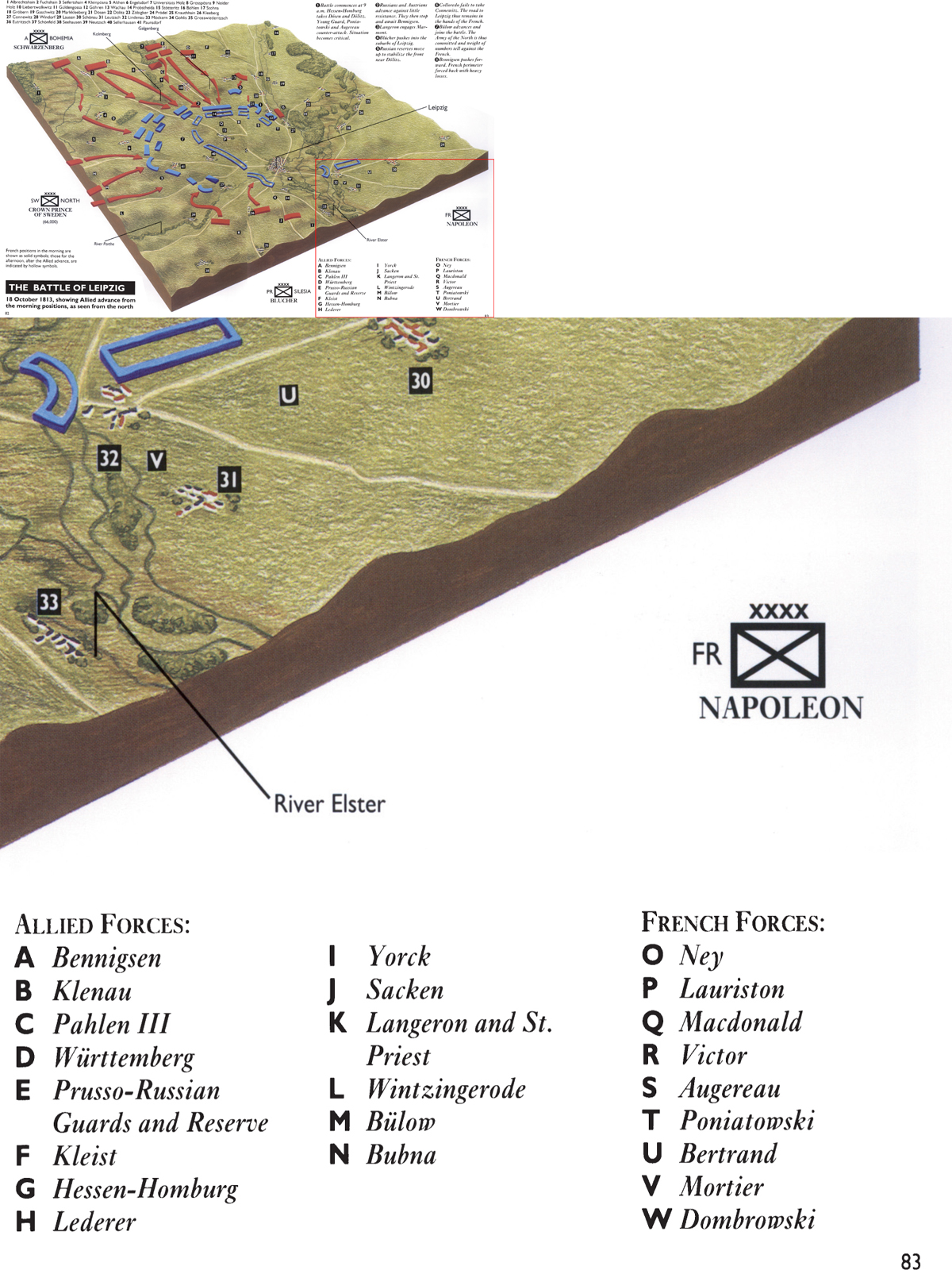

During the night of 17 October Napoleon shortened his front by withdrawing his troops to positions nearer Leipzig, deployed as follows: Right wing under Murat – Corps Poniatowski, Augereau and Victor deployed from Connewitz to Probstheida, supported by the Guard and the bulk of the cavalry. Centre under Macdonald – XI Corps deployed from Zuckelhausen through Holzhausen to Steinberg supported by Lauriston and Sebastiani. Left wing under Ney – in and around Paunsdorf Saxon Division, Division Durutte and Corps Marmont supported by Souham and 1½ divisions of Arrighi’s Cavalry Corps. In Leipzig – Division Dombrowski, the garrison of Leipzig, Cavalry Division Lorge. In Lindenau – two divisions of the Young Guard under Mortier. Taking into account losses on 16 October, Napoleon had about 160,000 men and 630 guns at his disposal.

Schwarzenberg formed his men up for the final assault. Column 1 under Hessen-Homburg consisted of Corps Colloredo and Merveldt, Divisions Bianchi and Weissenwolf and Cavalry Division Nostitz. Its orders were to secure Connewitz and move through Markkleeberg on Leipzig. Column 2 under General Barclay consisted of Corps Kleist and Wittgenstein, the Russo-Prussian Guards and Reserves. This column was to advance through Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz on Probstheida. Column 3 under General Bennigsen consisted of the Polish Reserve Army, Division Bubna, Corps Klenau, the Prussian Brigade Ziethen and Platow’s Cossacks. Its orders were to move round the enemy flank and move on Zuckelhausen and Holzhausen from the direction of Fuchshain and Siefertshain. Column 4 under the Crown Prince of Sweden consisted of the Army of the North together with Langeron and St. Priest. This column was to cross the Parthe at Taucha and link up with the Army of Bohemia. Column 5, the remainder of the Army of Silesia, was to advance on the north-west of Leipzig. Column 6 under Gyulai, consisting of Corps Gyulai, Division Moritz Liechtenstein and Detachments Mensdorff and Thielmann, was to advance on Lindenau from Klein Zschocher. Estimated strength of the Allied forces was about 295,000 men with 1,360 guns.

Bennigsen. The commander of a corps of Russians. This corps was an entirely fresh reserve formation which was committed on 18 October. Being the one and only significant reserve held by the Allies, the commitment of Bennigsen tipped the scales decisively in the favour of the Allies. Contemporary etching.

For once, the sun started shining. At 9 o’clock the columns were formed up, ready to march. Napoleon’s request for an armistice was ignored. Even in the face of such odds, the French put up a determined and bitter resistance. Hessen-Homburg pressed forward, taking Dösen and Dölitz. A French counter-attack threw him out of Dölitz. The Young Guard, Poniatowski and Augereau pushed him back and Hessen-Homburg was severely wounded. Colloredo assumed command. Schwarzenberg took such a serious view of the situation that he threw in Rajewski’s grenadiers and 3rd Cuirassier Division. He even recalled Gyulai. Dölitz was recaptured but the advance ground to a halt.

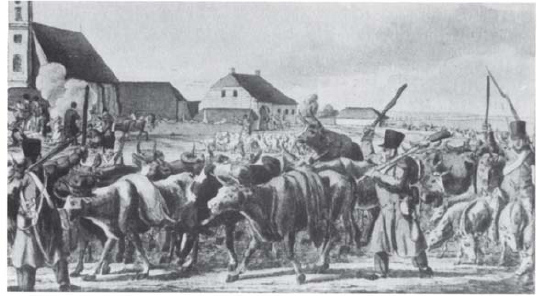

French soldiers gathering supplies at Paunsdorf during a lull in fighting at Leipzig. The great burden that this campaign placed on the economy and civilian population of Saxony should not be forgotten. Although Napoleon had his admirers in this part of Germany, the bulk of the population were simply very war weary and were waiting in hope for peace. Geissler.

Sellerhausen. Ney’s second line of defence once Paunsdorf had fallen. It was captured by Bülow’s Prussians.

Friccius leads his East Prussian militia battalion into Leipzig itself. This act broke the final French line of defence of the town on 19 October. The church in the background is St. Nicolas’s, focal point for the demonstrations of October 1989. Painting by Fritz Neumann.

French 6 pdr artillery piece. This particular gun was captured by Swedish forces during the Leipzig campaign and can be seen at the Armemuseum in Stockholm. (Photograph Armémuseum Stockholm).

Barclay marched off at 8 o’clock and achieved his objectives without any great difficulties. Within cannon range of Probstheida, he halted and awaited the arrival of Bennigsen who had the farthest distance to cover. To his delight the French were withdrawing and offered little resistance. By 10 o’clock he was in position. Holzhausen and Zuckelhausen fell to determined assaults. Gerard was pushed off the Steinberg. Division Bubna moved on Paunsdorf which was strongly defended. At 2 p.m. the French still held Zweinaundorf, Mlkau and Paunsdorf. Bennigsen awaited the arrival of the Army of the North before committing himself to storming these villages.

On the northern front Langeron engaged Marmont while Blücher started to push into the suburbs of Leipzig itself. Napoleon sent off a division of the Young Guard to help Dombrowski’s hard-pressed Poles. The situation stabilized. Bertrand cleared the road to Weissenfels.

The situation at 2 p.m. was still undecided. The French forces were still intact. They held various strongpoints around the perimeter of their position, had held off Allied advances from the north and had cleared their line of retreat. Against such odds, the French could not win a victory, but they still had the initiative and could withdraw at will.

Colloredo failed all afternoon in his attempts to take Connewitz, the possession of which would decide the fate of Leipzig. At nightfall it was still in French hands. Barclay got no further than Probstheida which had been turned into a little fortress by its defenders. The village changed hands several times during the course of that afternoon but remained in French hands at nightfall.

Bennigsen had more success, particularly when Bülow’s Prussians closed in on Paunsdorf. Some 3,000 Saxons with nineteen guns took this opportunity to go over to the Allies as had Normann’s Brigade of Württemberg cavalry earlier that day. French cavalry attacks tried to stabilize the situation on this front but Ney’s remaining infantry fell back. Stötteritz became the centre of the French defences here. It would be a great exaggeration to say that the desertion of this handful of Saxons at this late stage of the conflict had any significant effect on the outcome of the battle. That had already been decided on 16 October. The subsequent events merely delayed the inevitable. The Army of the North continued its advance. Reports came in of a French retreat on Weissenfels. Napoleon had run out of choices. He now had to secure his retreat.

Schwarzenberg formed his forces into five columns for the assault on Leipzig. Napoleon’s retreat was to be threatened if not cut off by Yorck and Gyulai. The attempt to cut the French off was insufficient to be considered serious and was an error that would allow this war to continue into 1814. But one must remember that the Allies were generally exhausted. Fresh reserves for a pursuit were not to hand and a third day of bitter fighting was not regarded as a pleasant prospect. Under cover of darkness and the morning fog, the French had with-drawn into Leipzig itself and had begun their retreat. The French could enter from four gates to the east but leave by only one in the west so a degree of military organization was necessary.

Napoleon’s flight from Leipzig.

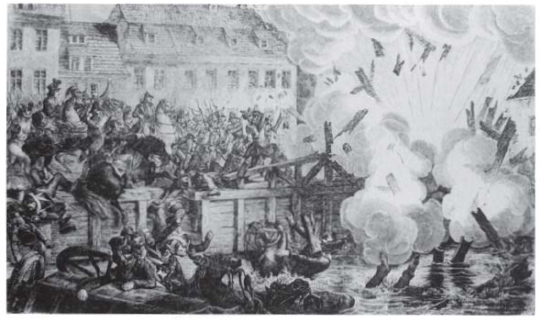

The final battle at the southern end of the Fleischerplatz. French prisoners-of-war are held around the baggage train of the Imperial Guard while the rearguard action continues not far away.

Napoleon was now staging a rearguard action to cover his withdrawal to France. Leipzig itself had a good potential for defence, but its great disadvantage to Napoleon was the fact that there was only one exit to the west, over the Fleischerplatz through the Ranstädter Gate and over two bridges, the first over the Pleisse, the second over the Elster and thence westwards along a causeway over the marshes to Lindenau. While the Allies had the option of assaulting one or more of several entrances to the town, the French had but one exit and were gradually being forced down a funnel into a bottleneck. It was inevitable that the level of confusion would rise as the French were forced back. A state of complete chaos was likely and this indeed occurred.

The bridge over the Elster. This bridge on the French line of retreat was blown up prematurely, cutting off part of the French rearguard. Some historians see this as a major blow to Napoleon. Had this bridge not been blown, he might have been able to save more of his army. However, in any event, he was going to have to fall back across the Rhine so this final act in the battle was of little significance in that respect. The fact that there was only one road westwards out of Leipzig caused more difficulties and delays to the retreat than the loss of this bridge.

Schwarzenberg brings news of victory to the Allied monarchs. This would indeed seem a good time for him to come back to his headquarters.

The Allied assault began at 10.30 a.m. on 19 October. Progress was slow. Every wall, gateway, building and street was defended. A battalion of East Prussian militia under Friccius made its name by breaking into the town. A French counter-attack almost succeeded but was thrown back by a battalion of Swedish Jäger with two cannon. The Allies now had the Grimma Gate in their possession. There were many such tales of heroism as the battle see-sawed through Leipzig. A major traffic jam developed as the French baggage trains tried to escape the Allied assault. Leipzig became a scene of chaos. Many retreating French soldiers tried to swim the Pleisse. Those who did not succeed laid down their arms to the advancing Allies. Tsar Alexander and King Frederick William III rode to the Market Place where they met the Crown Prince of Sweden, Bennigsen, Blücher and Gneisenau. Any attempt at pursuit was forgotten in the jubilation of victory. The battle was over but it would be another year before the war was won.

Napoleon marched with his army back to France. An attempt by the Bavarians to halt his pursuit was brushed aside. His regime did not collapse immediately. It might after all have survived a peace negotiated in the early days of 1813.

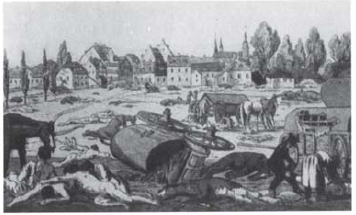

The wreckage of an army the day after battle. This scene at the Halle Gate, drawn by the eyewitness Geissler, clearly illustrates the aftermath of war - the stripped corpses, some of which appear still to be showing signs of life, the plundered wagons.

Poniatowski attempting to swim the Elster. Perhaps Napoleon’s greatest loss caused by the premature detonation of the Elster bridge. A number of generals managed to swim to safety. This unfortunate Pole did not and met a tragic death for such a noble figure.

a scene from the Battle of Hanau. Here, the Bavarians, having recently changed sides, made a futile attempt at stopping the French retreat. Napoleon brushed his erstwhile allies aside before continuing the march home.