The Ordnungspolizei may be considered as sub-divided into two main branches: the executive branch – the regular uniformed Police – and the administrative branch. The organizations embraced by the executive branch were the following:

The Schutzpolizei (Schupo) were the regular uniformed Police stationed in the larger towns and cities. For smaller communities a specific number of men were allocated dependent on the population size, ranging from one policeman for a populace of 2,000, to six for a populace of 10,000. Thereafter, manpower allocation was on a ‘per head of population’ basis; for instance, in areas with a population of up to 20,000, one policeman was allocated for every 1,000 inhabitants.

The basic Schupo organization was at precinct level. Each precinct (Reviere) covered between 20,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, with a police station manned by 20 to 40 officers who would patrol their local ‘beats’. A number of such precincts would be grouped together administratively to form a section or Abschnit. In very large cities a number of such Abschnitte could be administered as a Gruppe. The Schutzpolizei Abschnitte were under the control of a Kommandeur der Schutzpolizei for that city. This local commander would be under the direct control of the Polizeipräsident, who commanded not only the Schupo but all police organizations for his area.

In addition to the manpower allocated to precinct stations, the Schutzpolizei maintained ‘Barracked Police’ units or Kasernierte Polizeieinheiten. These were organized into companies of approximately 100 men (referred to as Hundertschaften, prior to the adoption of the military term Kompanie). When the situation required, these independent companies could be assembled into battalions on the authority of senior commanders such as the BdO. Their duties included providing guards (in conjunction with local SS units) for major party gatherings; dealing with ‘internal unrest’; preventing looting, and maintaining order and traffic flow after air raids or any other major catastrophes. To give an idea of the scale of such units, it is estimated that during the Anschluss with Austria in 1938 around 150 such Barracked Police companies were mobilized, representing some 15,000 men.

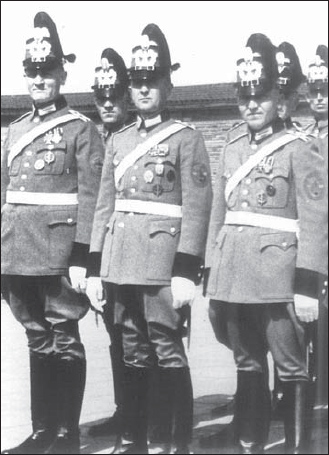

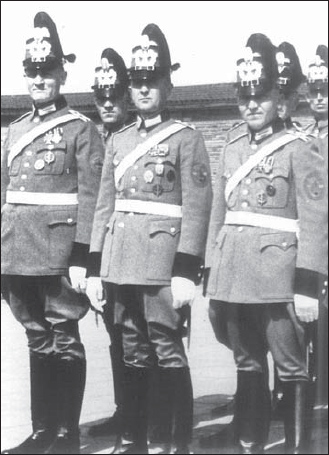

Schutzpolizei NCOs in parade dress. All three in the front rank are decorated former soldiers displaying the Iron Cross, and two of them wear the Wound Badge; equally, all three seem to wear the bronze SA-Wehrabzeichen. Many former Army men joined the Landespolizei after World War I. (Josef Charita)

With the outbreak of war, the Police formed a considerable number of rifle battalions (certainly in excess of 80), each consisting of more than 500 men. These were sent out of Germany to operate behind the front line combat units of the Wehrmacht, with the tasks of preventing partisan activity and sabotage, securing lines of communication, guarding installations, and generally maintaining law and order. Manpower was made available for such units by drafting in large numbers of Police reservists to form additional battalions. Unfortunately, as already noted, the activities of Schutzpolizei units in the occupied countries went far beyond what might be considered legitimate security operations.

On the Eastern Front other Police units became embroiled in front line combat against regular Red Army troops, and despite their small size and light armament they sometimes acquitted themselves well in battle – an obvious example being those which fought in the defence of the Kholm Pocket in 1942.

During 1941 so many Police units were already in the field in the East that they were assembled into regiments; 28 of these were formed, each of three battalions, giving a total of well over 46,000 men. As the war dragged on nine more such regiments were formed, now known as Polizei Schützen Regimenter – ‘Police rifle regiments’. In 1943, all such regiments were renamed as SS-Polizei (Schützen) Regimenter.

These units consisted of Schupo personnel with relatively good levels of fitness and training. Those less able or more elderly reservists (often over 50 years of age) who were called up into the Barracked Police remained in Germany, where they were formed into Polizei Wachbataillone or ‘guard battalions’, to perform duties such as maintaining order in areas heavily affected by bombing. These Wachbataillone were of negligible value as combatants against advancing Allied units.

There were a number of smaller units which might be available to the local Kommandeur der Schutzpolizei for particular duties, including:

This Revieroberwachtmeister wears the M1943 field blouse and peaked field cap; the latter may show Truppenfarbe piping at the crown seam, and certainly has the white metal Police eagle pinned below the machine-woven national cockade. Note the contrasting black swastika on the bright green sleeve eagle; and the bar of chevron-flecked silver cord obviously added retrospectively across the base of his shoulder straps, which also bear a pin-on cipher above the rank pip. His status as an Eastern Front combat veteran is unmistakable: he displays the ribbons of the Iron Cross Second Class and the Eastern Winter Campaign 1941/42 medal, a General Assault Badge and a black Wound Badge.

Kraftfahbereitschaften Motor vehicle maintenance crews.

Motoriserte Verkehrsbereitschaften The great majority of Police activity was carried out on foot, but these motorized units provided fast response patrol cars and motorcycle/sidecar combinations.

Verkehrsunfallbereitschaften These were motorized fast response units, but for reacting to traffic accidents rather than crimes; they might be equipped with specialized vehicles such as tow trucks.

Verkehrskompanie (mot.) zbV These units, created late in 1941, were tasked with control of wartime traffic; they made spot checks to ensure that vehicles were roadworthy and were being lawfully used under the various wartime restrictions.

Polizei Nachrichtenstaffeln These maintained Police communications networks – radio and telephone systems, fixed and mobile trans-mitters, etc.

Polizei Reiterstaffeln A small number of independent mounted units existed. In most areas, when required, the mounted Police worked in mixed patrols alongside regular Schupo foot policemen.

Motorisierte Überfallkommandos The Police riot squads, on hand to quell civil unrest or to carry out other emergency work. Given the nature of the regime, anti-government demonstrations inside Germany on such a scale as to require the use of such troops were, to say the least, unusual. They were equipped with light armoured cars armed with machine guns. Although not seeing much use within the Reich, they were deployed in occupied territories to assist in anti-partisan operations.

Sanitätsdienst Each area had its own Sanitätsstelle or first aid centre to provide treatment to injured policemen.

Veterinärdienst The Police maintained their own veterinary service to provide care and treatment to their horses and police dogs.

* * *

The regular uniformed Schupo received plain clothes assistance from within and outside their own ranks. Some would occasionally don civilian clothing for undercover patrols – these were distinct from the Kriminal Polizei (equivalent to the British CID), who operated in plain clothes all the time.

One of the major sources of assistance to the Police was the Nazi Party’s own motorized branch, the NSKK (National Sozialistisches Kraftfahr Korps). The NSKK had its own Verkehrsdienst or traffic control service which was often employed as an auxiliary traffic police force – not only in Germany but also in the occupied territories, including what were effectively combat zones on the Eastern Front and in North Africa.

Other assistance came from the Hitler Jugend.3 As early as 1934 the Hitler Youth formed its own patrol service (HJ-Streifendienst), initially to maintain order and discipline within the HJ, but also to prevent unruly behaviour by other youths (including drinking or smoking in public). As time went on these most dedicated members of the HJ became an important source of auxiliary manpower for the Police. They could be depended upon to act as informants (in many cases even against their own families); and there are even said to have been occasions when the older members provided volunteers for firing squads.

A further auxiliary force, created in 1942, was the Stadtwacht. These members of the SA-Wehrmannschaft provided a direct equivalent to the Landwacht (see below) created for the rural areas, but assisted the Police in large cities. Eventually, virtually every German not in the armed forces or emergency services was made liable for periodic duty in the Stadtwacht or Landwacht. Behind these organizations lay two reserves, one composed of men who would cover initial call-ups for those in the other, whose essential duties exempted them from service in anything but dire emergency. Both Landwacht and Stadtwacht wore a white armband with the name of their organization printed in black letters.

These so-called ‘Municipal Police’ were effectively a half-way measure between the Gendarmerie, which controlled rural areas with lower population density, and the regular Schupo in densely populated areas. It was intended to extend the responsibility of the Gendarmerie to areas of up to 5,000 inhabitants, which would have reduced the size of the Schupo der Gemeinden even further, but this process had barely started before the war ended. It is estimated that over 1,300 ‘municipalities’ existed which were too large to be controlled by the Gendarmerie but too small for the Schutzpolizei des Reiches.

In such areas, although the true control of Schupo der Gemeinden units lay with the BdO for the area, sited at the Wehrkreis headquarters, they were in practice at the day-to-day disposal of the Bürgermeister of the municipality. Schutzpolizei der Gemeinden in smaller communities were typically commanded by a Hauptmann or Oberleutnant, and were designated as service detachments – Dienstabteilungen. Personnel could move between the Schupo des Reiches and the Schupo der Gemeinden, and the difference between the two, apart from the size of the units and their equipment levels, was predominantly administrative.

Headgear

The normal service dress headgear for the Schutzpolizist was a shako with a stiff fibre body covered in grey-green cloth (greener than the Army feldgrau), with black lacquered front and rear peaks (visors) and a flat black lacquered crown; on either side of the body were two mesh ventilation holes, and a black leather chin strap was fitted. The insignia were a large aluminium alloy Police-pattern wreathed eagle national emblem, below an elongated oval cockade in the national colours. Officers wore metal chin scales in place of the leather chin strap, and a cockade embroidered in metallic thread. General officers wore gilt rather than silvered metal fittings. For parade dress, a long black horsehair plume was worn with the shako (later changed to white for officers).

For their security role some Police units had been issued with a limited number of light armoured vehicles since well before the outbreak of war. During the wartime years they received many more for their rear-area security duties outside Germany – usually obsolescent captured types like this French Panhard 178 armoured car, photographed somewhere on the Eastern Front. Note the white Police national emblem painted on the turret; the commander appears to wear a motorcyclist’s rubberized coat, and possibly a black Panzer field cap, though the contrasts make it hard to be sure.

A member of the Schutzpolizei der Gemeinden in service dress with shako. The pale cord edging of his collar patches shows clearly against the dark brown collar, and the wine-red sleeve eagle of the Municipal branch against the pale grey-green tunic. It has no district name above – these were ordered removed from Gemeinde Polizei insignia in late 1941. (Josef Charita)

The Police national emblem in white metal, as displayed on the peaked service caps. The first pattern (left) was smaller and featured an unwreathed swastika; it was replaced with the definitive pattern well before the war.

Undress headgear was a peaked (visored) service cap – Schirmmütze – with a grey-green crown and a dark brown band. The crown seam and both edges of the band were piped in the appropriate Truppenfarbe. The cap had a black lacquered peak; enlisted men and NCOs wore a black leather chin strap and officers silver chin cords. Insignia were a silver-coloured metal Police national emblem on the band, below a circular metal cockade in the national colours on the front of the crown. For general officers the cap piping, chin cords and national emblem were in gilt rather than silver finish.

A field cap – Feldmütze or sidecap – in grey-green wool normally featured bright police-green piping along both top crests and down the front of the crown (moved in 1942 to the edge of the flap). It bore a machine-woven version of the Police national emblem in silver-grey on black, but no national cockade. Officers’ caps – alone – resembled the M1938 type for Army officers, with silver braid piping to the crown and front of the flap. Insignia for officers were machine-woven in silver thread on black.

Predating the M1943 Einheitsfeldmütze of the Wehrmacht, a cloth-visored field cap was introduced for the Police in 1942. It was manufactured in both one- and two-button types, and had silver crown piping for officers (and sometimes Truppenfarbe piping for other ranks). Metal insignia were often attached, but special machine-woven one-piece insignia were produced, with the national cockade above the Police national emblem on a grey-green backing.

The full range of steel helmet styles as used in the Wehrmacht and paramilitary units were also issued to the Police. Police helmets featured a shield decal on the left-hand side with a silver Police national emblem on black, and on the right a red shield with white disc and black swastika. Police motorcyclists were issued a special leather crash-helmet, with a reinforced padded band around the lower edge of the crown and a leather visor; a large metal Police national emblem was worn on the front.

Service tunics

The standard Waffenrock was cut from grey-green wool, with contrasting dark brown collar and cuff facings. The tunic had two pleated patch breast pockets and two unpleated skirt pockets, all with three-point flaps fastened with single aluminium buttons. The collar, cuffs, front edge and rear skirt panels of the tunic were piped in Truppenfarbe. Each cuff had two aluminium buttons sewn one above the other at the rear edge; the front of the tunic was fastened with a single row of eight buttons; and the rear featured two buttons at waist level and one at the base of each Truppenfarbe-piped skirt panel (false pocket). As described above under ‘Police Insignia’, a machine-embroidered Police national emblem was worn on the left sleeve, and mirror-image Litzen on the collar; specific branches were identified by Truppenfarbe distinctions (see list above), and specific ranks by the shoulder straps. The service tunic was normally worn with matching breeches and black leather jackboots (of a higher quality than the normal Wehrmacht marching boots). For walking-out dress straight grey-green trousers, piped with Truppenfarbe at the outseams, were worn loose over black shoes.

Coats

For cold weather a grey-green double-breasted greatcoat was issued, fastened with two rows of six buttons. This had a cloth rear half-belt with two buttons, and a rear skirt vent from waist to hem. The collar alone was faced with dark brown and piped with Truppenfarbe. No collar patches or sleeve eagle were worn. General officers wore gilt buttons. A raincoat was also produced in lightweight waterproof material, to an almost identical pattern to the greatcoat.

Field service tunics

In 1943 an Army-style field service tunic – Feldbluse – was produced, as more suitable for front line wear. This was single-breasted, all in grey-green or feldgrau wool without collar or cuff facings, and fastened with six buttons painted field-grey. Cuffs were conventional, split up the rear with hidden button fastening. Insignia for enlisted ranks on this tunic tended to be machine-woven artificial silk Litzen applied directly to the collar rather than to a coloured backing patch. Officers normally wore the same hand-embroidered insignia as on their service dress tunics. The field service tunic was usually worn with long field-grey wool trousers and marching boots, or ankle boots and canvas gaiters.

Camouflage uniforms

In 1944 a special camouflage field uniform was manufactured for Police troops. This was almost identical to the so-called ‘dot-’ or ‘pea-pattern’ field uniform widely used by the Waffen-SS from that year. The non-reversible jacket and trousers were cut in the same lightweight cotton drill material, the jacket with four patch pockets and fastened with six buttons; but a minor peculiarity of the Police issue seems to have been that the breast pockets had box pleats.

Armoured vehicle uniforms

Police units issued with armoured vehicles were authorized to wear the special black clothing for armoured personnel. Similar in cut to the black Panzer uniform used by the Army, its jacket featured bright police-green piping to the collar. Regular Police collar Litzen and shoulder straps were attached; but on this jacket the Police sleeve eagle was worked in green on a black base, with a white swastika for contrast. Normal Panzer-issue black trousers were worn, and a version of the black visored field cap was also produced bearing Police insignia.

Accoutrements

Enlisted men wore a black leather belt with both the service dress and field service tunics. The rectangular silver-coloured buckle resembled that of the Army, but in place of the national emblem the wreath and motto ‘Gott Mit Uns’ surrounded a large ‘mobile’ swastika. For parade dress, a white leather waist belt was worn, and a white leather pouch belt over the left shoulder with a black leather pouch displaying a white metal Police eagle on the flap.

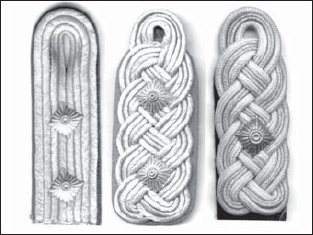

Police officers’ shoulder straps were of identical design to those of the military: (left & centre) Hauptmann and Oberst, silver cord and gilt pips on Truppenfarbe underlay; (right) Generalmajor, gold cords with thinner silver cord between, silver pips. Police straps usually have bright aluminium cords, though the wartime matt finish may also be encountered. So may junior officers’ straps with an intermediate layer of brown between the cord and the main coloured underlay; these indicate the wartime-only ranks of Revier-Leutnant to Revier-Hauptmann, to differentiate them from career officers.

The hilt of a Police dress bayonet, with eagle-head pommel, staghorn grips with Police eagle, and oak leaf decoration to the quillon. In this case the eagle’s eye is a simple engraved circle rather than the spring release catch, showing that this bayonet lacks the catch and slot for attachment to a rifle muzzle. The bayonet was available in different blade lengths: the official issue was 33cm (13in), but private-purchase pieces had 25cm (9.9in) blades.

Officers normally wore a simple black leather belt with double-claw frame buckle, but on formal occasions added a cross strap from the right shoulder to the left hip; a round silver-coloured clasp bearing the swastika was sometimes seen on the black belt. This clasp was always worn on the full dress belt, which was of aluminium brocade shot with a red line between two black lines; a matching pouch belt was added for parade order.

Sidearms

The standard sidearm for policemen under the rank equivalent of warrant officer was the bayonet. A range of styles had in common a stag-horn grip, oak leaf decoration to the quillon, and a pommel representing an eagle’s head – the press-button bayonet release catch suggested the eagle’s eye. In some cases the bayonet could actually be fitted to a rifle, in others it lacked the necessary slot and spring and was purely decorative. On the grip was fixed a small alloy Police national emblem. The black leather scabbard had a metal throat and chape and was suspended from a black leather frog. The bayonet ceased to be manufactured in 1941. Thereafter the standard Wehrmacht bayonet tended to be used; and after 1943 the bayonet was replaced by the pistol as the standard sidearm for all but ceremonial occasions.

Police officers and warrant officers were authorized to carry a sword from 21 June 1936. This long, straight-bladed ‘Degen’ had a D-shaped knucklebow; a button-shaped pommel; a grip of ribbed black wood with silver wire in the grooves, displaying a silvered Police national emblem; and an ornate collar with oak leaf decoration. The scabbard was finished in black enamel paint, with a silvered chape and locket, the latter in an interlaced design. It hung from a single ring and suspension strap. A simpler version was authorized for other NCOs, without the wire wrap to the grip or the silvered chape. The full dress fist straps of bayonets and swords were all of aluminium brocade shot with red-between-black lines, with a plain braid knot.